Abstract

Activation of the amygdala either during emotional arousal or by direct stimulation is thought to enhance memory in part by modulating plasticity in the hippocampus. However, precisely how the amygdala influences hippocampal activity to improve memory remains unclear. In the present study, brief electrical stimulation delivered to the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA) following encounters with some novel objects led to better memory for those objects one day later. Stimulation also elicited field-field and spike-field CA3-CA1 synchrony in the hippocampus in the low gamma frequency range (30-55 Hz), a range previously associated with spike timing and good memory. Additionally, the hippocampal spiking patterns observed during BLA stimulation reflected recent patterns of activity in the hippocampus. Thus, the results indicate that amygdala activation can prioritize memory consolidation of specific object encounters by coordinating the precise timing of CA1 membrane depolarization with incoming CA3 spikes to initiate long-lasting spike-timing dependent plasticity at putative synapses between recently active neurons.

Keywords: amygdala, coherence, gamma, hippocampus, memory

Introduction

Emotional arousal often leads to better memory for an event, and decades of influential work has shown that this benefit to memory depends on the amygdala (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998; McGaugh, 2004; Pare, 2003). Activation of the amygdala during emotional arousal is thought to help prioritize memories for these typically important events (McGaugh, 2013), in part by modulating processes related to cellular consolidation (Dudai, 2004) in the hippocampus (Akirav & Richter-Levin, 1999; Frey, Bergado-Rosado, Seidenbecher, Pape, & Frey, 2001; Ikegaya, Saito, & Abe, 1995; McIntyre et al., 2005; McReynolds, Anderson, Donowho, & McIntyre, 2014). Indeed, building on earlier studies using electrical amygdala stimulation (e.g., Gold, Hankins, Edwards, Chester, & McGaugh, 1975; Kesner, 1982), recent studies in rats have shown that brief (1 s) electrical stimulation of the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA) can enhance memory consolidation for specific encounters with objects (Bass, Partain, & Manns, 2012) and that this event-specific enhancement depends on the hippocampus (Bass, Nizam, Partain, Wang, & Manns, 2014). However, little is known about how stimulation of the amygdala influences neural activity in the hippocampus in an awake animal, and thus a fundamental question is how the amygdala intervenes in the initiation of the cellular consolidation in a manner that maintains the event-specificity of the memory enhancement.

Neuronal oscillations are thought to be important for synaptic plasticity in part by coordinating presynaptic neurotransmitter release with postsynaptic membrane depolarization (Buzsáki & Draguhn, 2004; Jutras & Buffalo, 2010). In particular, studies in rats (Trimper, Stefanescu, & Manns, 2014), monkeys (Jutras, Fries, & Buffalo, 2009), and humans (Fell et al., 2001) have shown that synchronization of hippocampal activity in the low gamma frequency range (~30-55 Hz) during encoding correlates with good recognition memory or recall. Thus, one possibility is that the amygdala modulates processes related to cellular consolidation in the hippocampus by influencing hippocampal gamma synchrony to the benefit of spike-timing dependent plasticity.

To investigate how the amygdala prioritizes memory consolidation, we recorded local field potentials and spiking activity in the hippocampus in rats that received brief electrical stimulation to the BLA immediately following some object encounters. Replicating previous studies (Bass et al., 2014, 2012), memory for those objects was enhanced compared to control objects when memory was tested 1 day later. The post-exploration timing of the BLA stimulation was selected to avoid influencing overt behavior or other non-memory factors such as attention at the time of encoding and was based on a long-standing precedent in studies regarding the role of the amygdala in memory consolidation (Goddard, 1964; Kesner, 1982; McGaugh, 2004). Building on this previous work, the present study also found that BLA stimulation elicited synchronization of local field potentials and action potentials within the hippocampus in the low gamma frequency range and that the spiking patterns observed during stimulation reflected recently active neuronal ensembles.

Method

Subjects

Nine adult male Long-Evans rats were housed individually (12-hr light/dark cycle; testing during light phase) with free access to water and placed on a restricted diet such that they maintained at least 90% of their free-feeding body weight (~400 g). All procedures involving rats were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Emory University.

Novel Object Recognition Memory Task

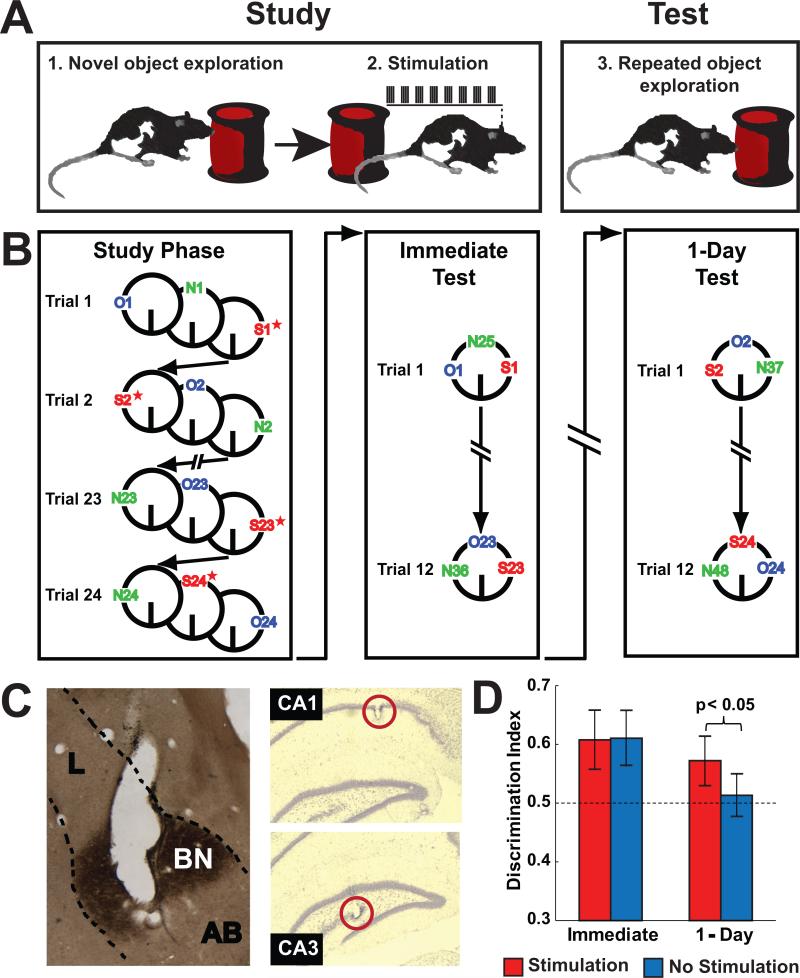

Rats performed a novel object recognition memory task (see Figure 1) similar to that used previously (Bass et al., 2014, 2012). Briefly, rats were allowed to explore freely a series of objects as they completed clockwise laps around a circular track (diameter = 91.5 cm, track width = 7 cm). During the Study Phase, some of the object encounters were followed by brief electrical stimulation to the BLA (Stimulation objects), while other objects were not (No Stimulation objects). Memory for half of these objects was tested immediately after the end of the Study Phase (Immediate Test), and memory for the other half was tested approximately 24 hours later (1-Day Test). On both tests, objects from the Study Phase were repeated in the same location using identical duplicates to avoid scent marking. Thus, including duplicates, each rat was presented with 72 objects during the Study Phase, 36 objects during the Immediate Test, and 36 objects during the 1-Day Test (see Fig. 1). Unilateral stimulation was delivered to the left BLA on half of the trials and to the right BLA on the other half of the trials during the Study Phase. All behavioral sessions were recorded on digital video (30 frames/sec) for frame-by-frame analysis of exploration. A rat was considered to be exploring an object if the rat was within 2 cm of the object and showing signs of active investigation (e.g. whisking and directed attention), but exploration was not scored if the rat climbed over the object to sniff the air. This method of analyzing behavior has been shown to have high inter-rater reliability (Bass et al., 2012; Galloway, Lebois, Shagarabi, Hernandez, & Manns, 2014; Trimper et al., 2014). Memory for repeated objects was assessed by comparing exploration of repeated (Stimulation and No Stimulation) objects to exploration of novel (New) objects (discrimination index = New/[New + Repeat]; see Bass et al., 2012, 2014).

Figure 1.

Overview of procedure: memory task, example histology, and memory performance. A, The illustration depicts a rat receiving brief unilateral electrical stimulation of the BLA immediately after exploring a novel object during the Study Phase as well as the rat encountering a duplicate of the same object again during the object recognition memory Test Phase. B, The schematic shows a full experimental procedure in which a rat encountered one object from each of three conditions on each trial while completing clockwise laps on a circular track. Stimulation objects (red, “S”) were followed by brief electrical stimulation to the BLA (denoted by a red star) immediately following the offset of exploration during the Study. No Stimulation objects (blue, “O”) were not followed by stimulation. New objects (green, “N”) were replaced by novel objects on the test. Object recognition memory was assessed on either the Immediate Test or the 1-Day Test. C, The left panel shows the postmortem marking lesion of a stimulating electrode localized to the BLA (dashed line) in a section stained for acetylcholinesterase (lateral nucleus, L; basal nucleus, BN; accessory basal nucleus, AB). Electrode tips were localized to the left and right BLA in all rats included for analysis. On the right, sections were stained with cresyl violet to facilitate localization of recording tetrodes in the pyramidal layer of CA1 (upper) and CA3 (lower) in the hippocampus. D, Rats remembered Stimulation objects better than No Stimulation objects on the 1-Day Test (p < 0.05). There was no difference in memory for objects on the Immediate Test. The dashed line indicates chance performance. Error bars show the SEM (n = 7).

Surgery and Tetrode Positioning

Stereotaxic surgery was performed on rats under isoflurane (1-3% in oxygen) to implant twisted bipolar stimulating electrodes (platinum, 0.0075 mm diameter, Teflon insulation, Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) bilaterally into the BLA (3.5 mm posterior, 5.2 mm lateral, and 8.9 mm ventral to bregma) and a chronic recording assembly with independently movable nichrome tetrodes over the right hippocampus (centered at 4.8 mm posterior and 4.1 mm lateral to bregma; CA3 centered at 4.2 mm posterior and 4.0 mm lateral to bregma, with a target depth of 4.4 mm ventral to bregma; CA1 centered at 5.2 mm posterior and 4.2 mm lateral to bregma, with a target depth of 2.0 mm ventral to bregma). The intermediate third of the septal-temporal axis of the hippocampus was targeted because it receives projections from the BLA (Petrovich, Canteras, & Swanson, 2001; Pikkarainen, Ronkko, Savander, Ricardo, & Pitkanen, 1999), plays a critical role for rapid learning in the hippocampus (Bast, Wilson, Witter, & Morris, 2009), and is necessary for the brief electrical stimulation of the BLA to be effective in enhancing memory (Bass et al., 2014). Each tetrode contact was plated with gold to reduce the impedance to ~200 kΩ at 1 kHz. A ground wire was attached to a stainless steel screw implanted in the skull midline over the cerebellum. Following surgery, rats received injections of buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) every ~12 h for 36 h and oral meloxicam (1 mg/kg) every day for three days and were allowed to recover over the next 1-2 weeks. Tetrodes were slowly lowered into the pyramidal cell layer of CA3 and CA1 in ~60 μm increments over the following 1-2 months. Tetrode localization was assisted by the electrophysiological hallmarks of CA3 and CA1. Testing occurred at least 24 hrs after the last tetrode adjustment. In addition, prior to euthanasia, rats were anesthetized, and a 20-40 μA current was passed through each stimulating electrode and recording tetrode for 20 s, creating an electrolytic lesion at the tips of the electrodes for postmortem localization. Brain sections containing tracts from the stimulating electrodes were stained for acetylcholinesterase to facilitate identification of structures in the BLA, and the remaining sections were stained with cresyl violet to facilitate visualization of the pyramidal cell layers of CA3 and CA1 in the hippocampus (Figure 1C). For each rat, one tetrode in CA3 and CA1 that recorded pyramidal neuron spiking across all test sessions was selected to provide the local field potential for that region, ensuring relatively consistent positioning of that tetrode in the pyramidal cell layer.

Electrical Stimulation

The electrical stimulation parameters used for behavioral testing in this study were identical to those used previously (Bass et al., 2014, 2012). A hand-held device was used to manually trigger a 20 μA current from a current generator (S88X Dual Output Square Pulse Stimulator, Grass Technologies, West Warwick, RI). Bipolar stimulation was delivered unilaterally to the BLA via the bipolar stimulating electrode for 1 sec in 8 trains of 4 pulses at 50 Hz (each pulse was a 500 μs biphasic square wave). For a subset of rats (see Supplemental Table 1), stimulation of the BLA was also administered with an 80-Hz pulse frequency (5 pulses per train) as they completed laps around an empty circular track. None of the rats showed signs of acute stress during BLA stimulation (e.g., vocalizations, defecation, urination, or freezing) or evidence of seizures in either overt behavior or in hippocampal activity at any time.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Local field potentials (sampling rate = 1.5 kHz; bandpass filter = 1-400Hz) and spike data (sampling rate = 30 kHz, bandpass filter = 600-6000 Hz) were obtained with the NSpike data acquisition system (nspike.sourceforge.net), and spike sorting was performed offline using software (Offline Sorter, Plexon Inc., Dallas, TX). Clusters of spikes were manually defined based on waveform shape and amplitude across all 4 wires. Only clusters with clear boundaries were included in the data set. Putative pyramidal units were distinguished from interneurons based on firing rates and autocorrelograms, as these measures have been well characterized for pyramidal units and interneurons in the hippocampus (Csicsvari, Hirase, Czurko, & Buzsáki, 1998; Fox & Ranck, 1981). The remaining analysis were performed in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick MA) with custom scripts and Chronux, an open-source toolbox for analysis of local field potentials and spike data (Bokil, Andrews, Kulkarni, Mehta, & Mitra, 2010).

Local field potentials for each rat were obtained from a tetrode localized to the pyramidal layer in the distal half of CA1 in the transverse axis and from a tetrode in the pyramidal layer in the proximal half of CA3 in the transverse axis to minimize rat-to-rat variability and because proximal CA3 and the BLA project directly to distal CA1 (Petrovich et al., 2001; Pikkarainen et al., 1999; van Strien, Cappaert, & Witter, 2009). The stimulation artifact in the local field potentials was largely removed via template subtraction for both 50 Hz and 80 Hz stimulation, similar to methods used in previous studies (Montgomery, Gale, & Huang, 2005; Wichmann, 2000). Briefly, a separate template was created for each pulse of the stimulation train by averaging the artifact across all ipsilateral or contralateral trains within each rat. The biological effects of stimulation were further disambiguated from the residual artifact by contrasting the results of ipsilateral and contralateral stimulation.

Coherence, phase offset, CA3 power, and CA1 power were estimated using a multi-taper fast Fourier transform with parameters that have been used in previous work to characterize gamma frequency oscillations in the hippocampus (Bokil et al., 2010; Trimper et al., 2014). Moving time window coherograms were calculated with a sliding time window of 0.5 s and 0.05 s steps. A frequency bandwidth ± 6 Hz was used with 5 tapers. Line graphs of coherence were obtained by averaging the moving window data from 0.25 s after the onset of an event to 0.25 s before the offset of an event because the 0.5 s sliding window resulted in a loss or contamination of data within 0.25 s of the event boundaries. Phase coherence was derived from moving time window estimates of the phase offset. Specifically, phase offset (Φ) was represented as a vector (eiΦ) for each trial, and then the phase coherence was calculated as the squared complex magnitude of the mean resultant vector, resulting in a number between 0 and 1 (Hurtado, Rubchinsky, & Sigvardt, 2004). Coherence and phase coherence estimates were calculated for each rat, Fisher transformed, bias corrected for any differences in the number of data points (Bokil, Purpura, Schoffelen, Thomson, & Mitra, 2007), and then averaged together.

Statistical significance of coherence and phase coherence data was assessed using a random shuffling approach that accounted for family-wise error rate (Maris & Oostenveld, 2007). Briefly, the local field potentials from ipsilateral and contralateral trials were shuffled 1000 times within each rat, and coherence and phase coherence estimates were calculated for each shuffle. For the original and shuffled data sets, frequency (line graphs) or time-frequency (moving window coherograms) clusters exceeding 2.5 standard deviations above or below the original difference were identified. The absolute value of the within-cluster sum was calculated for every cluster, and the maximum cluster value was obtained for every shuffle. Only clusters in the original data set exceeding the 99th percentile of the maximum cluster values were identified as statistically significant differences between groups.

The relationship between spikes and the phase of oscillations in the local field potential was characterized by first filtering the local field potentials from 30 to 55 Hz. The preferred phase of spiking was estimated by calculating the mean phase angle (mu), such that 0 degrees indicated the peak of the cycle. The strength of spike-phase preference was estimated as the mean resultant length (MRL) of the mean resultant vector. Most pyramidal units fire at very low baseline rates, less than 1 Hz (Csicsvari et al., 1998; Fox & Ranck, 1981). Thus, in order to obtain an estimate of the spike-phase relationship for pyramidal spikes, the gamma phase for each spike from all CA1 pyramidal units across rats were combined to estimate the CA1 MRL and the gamma phase for each spike from all CA3 pyramidal units across rats were combined to estimate the CA3 MRL. Only trials with at least 1 spike were included. Statistically significant pyramidal spike-phase relationships were identified by randomly shuffling ipsilateral and contralateral trials 2000 times. Ipsilateral and contralateral trials were shuffled within subject, keeping the number of ipsilateral and contralateral trials from each rat consistent with the original data set. Phase consistency estimates were obtained for each shuffle of the data, and the contralateral values were subtracted from the ipsilateral values, yielding a distribution of random differences. Spike-phase preference was considered to be significantly different between stimulation conditions if the actual difference lay outside the middle 98.33% of the data set, corresponding to an alpha value of 0.05, once Bonferroni corrected to control for multiple comparisons between the three anatomically meaningful spike-field combinations (CA3-CA1, CA3-CA3, and CA1-CA1; CA1 does not project to CA3). As the MRL can be biased based on the number of spikes, the phase preference was also calculated with pairwise-phase consistency (PPC), which has been shown to be unbiased estimator of phase preference (Vinck, van Wingerden, Womelsdorf, Fries, & Pennartz, 2010). PPC is calculated as the average cosine value of the absolute angular pairwise distance between each observation. Statistical significance was determined using the same shuffling procedure as used to assess the MRL.

Pyramidal unit spiking patterns during stimulation were compared to patterns observed in the 1 s immediately preceding stimulation. Similar to a previous approach for analyzing spike patterns during recognition memory (Manns & Eichenbaum, 2009), a multidimensional representation of each 1-s epoch was constructed from the firing rates of individual units in the neural ensemble such that each dimension represented a single neuron. The similarity in ensemble activity during these two epochs was quantified by calculating the Euclidean distance between pairs of points in this multidimensional space, with shorter pairwise distances corresponding to more similar representations. Pairwise stimulation-prestimulation distances were then averaged within conditions and across rats (1 test session per rat). Only trials with spikes were included. Rats were excluded if fewer than 20 putative-pyramidal units were recorded simultaneously during the session.

Results

Brief Stimulation of the BLA Enhanced Memory Consolidation for Specific Object Encounters

Rats with stimulating electrodes implanted bilaterally in the BLA and recording tetrodes implanted unilaterally in the intermediate septal-temporal portion of the hippocampus completed a novel object recognition memory task in which memory for half of the repeated objects was tested immediately after the end of the Study Phase (on the Immediate Test) and for the other half was tested approximately 24 h later (on the 1-Day Test). Supplemental Table 1 shows the number of rats included in each analysis and indicates that data from 2 of the 9 rats were unusable due to the misplacement of one of the stimulating electrodes. Figure 1 shows schematics of the procedure, examples of histology, and memory performance plotted as a standard discrimination index (see Method for details). Unilateral stimulation of the BLA for 1 s immediately after the offset of exploration for half of the to-be-repeated objects during the Study Phase resulted in better memory performance for those objects compared to control (No Stimulation) objects on the 1-Day Test (Stimulation vs. No Stimulation: t(6) = 2.69, p < 0.05) but did not affect performance on the Immediate Test (Stimulation vs. No Stimulation: t(6) = 0.08, p > 0.1), replicating the main behavioral results of two previous studies that found that BLA stimulation specifically enhanced the consolidation of memories of individual object encounters (Bass et al., 2014, 2012).

Low Gamma Coherence between CA3 and CA1 Increased During Novel Object Exploration

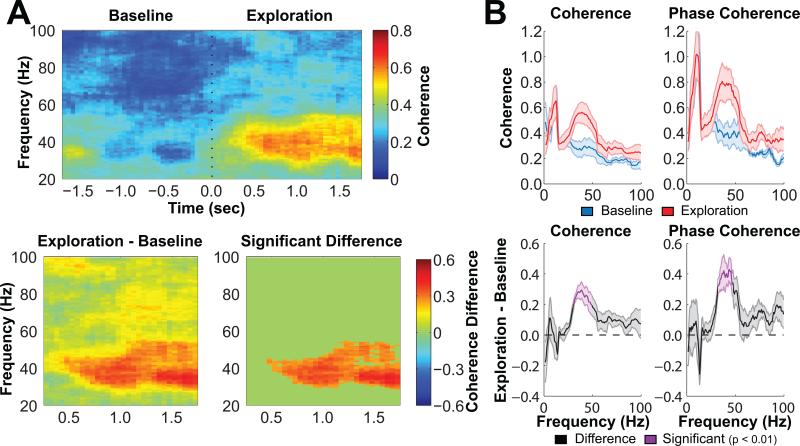

The 50-Hz pulse frequency of the BLA stimulation was based on previous reports of an endogenous gamma oscillation in the hippocampus of approximately the same frequency (Colgin et al., 2009; Csicsvari, Jamieson, Wise, & Buzsáki, 2003; Shirvalkar, Rapp, & Shapiro, 2010; Tort, Komorowski, Manns, Kopell, & Eichenbaum, 2009). Indeed, a recent study found that oscillatory synchrony between hippocampal regions CA3 and CA1 increased markedly in the low gamma (~30-55 Hz) range when rats initiated exploration of novel objects and that the level of low gamma CA3-CA1 synchrony related to subsequent memory for those objects (Trimper et al., 2014). Accordingly, Figure 2 shows for 5 rats in the present study the level of synchrony between local field potentials from hippocampal regions CA3 and CA1 as coherence (which reflects phase locking and covariation in oscillatory amplitude) plotted by time and frequency and as phase coherence (which more specifically reflects phase locking) plotted by frequency as rats approached and initiated exploration of novel objects explored at least 2 s during the Study Phase (see Method for details of analyses). Similar to the results of the previous study (Trimper et al., 2014), coherence and phase coherence in the low gamma range (~30-55 Hz) were significantly (p < 0.01) greater during exploration as compared to the 2-s pre-exploration baseline period.

Figure 2.

Gamma synchrony between CA3 and CA1 increased during novel object exploration. A, The top panel shows a moving time window coherogram and indicates that local field potentials in CA3 and CA1 of the hippocampus synchronized in the low gamma range following the onset of novel object exploration (at 0 s). The panel on the bottom left shows the difference in coherence between the first 2 s of object exploration (Exploration) and the 2 s prior to exploration (Baseline), and the panel on the bottom right shows only pixels that exceeded statistical significance (p < 0.01) when evaluated using a cluster-based randomization procedure (see Method). B, The top panels show mean coherence (left) and phase coherence (right) during baseline (blue) and exploration (red), and the bottom panels show the difference between exploration and baseline. Frequency bands that exceed statistical significance when evaluated using a cluster-based randomization procedure are highlighted in purple (p < 0.01). Shaded bands above and below the mean indicate SEM (n = 5).

Ipsilateral BLA Stimulation Evoked Potentials in CA3 and CA1

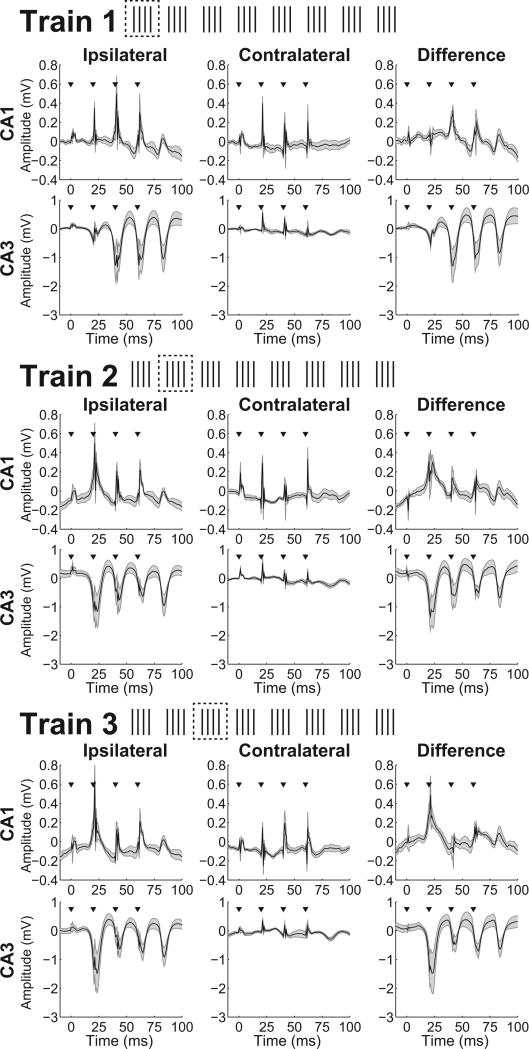

Figure 3 shows the average evoked response in wideband (1-400 Hz) CA3 and CA1 local field potentials from the first, second, and third 4-pulse trains of ipsilateral and contralateral 50 Hz BLA stimulation (Supplementary Figure 1 shows the average across all eight trains). Consistent with the largely ipsilateral projections from the BLA to the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (Petrovich et al., 2001; Pikkarainen et al., 1999), reliable evoked potentials were recorded in CA3 and CA1 only during ipsilateral stimulation. Accordingly, following an initial template-subtraction step to attenuate the stimulation artifact in the recordings (see Method), the residual stimulation artifact could be further accounted for by subtracting results of analyses from the contralateral trials, which were presumed to reflect mostly artifact, from results from the ipsilateral trials, which were hypothesized to reflect elicited neural responses in addition to artifact. Indeed, very little residual stimulation artifact remained following the ipsilateral-contralateral subtraction. The same subtraction approach was used in subsequent analyses.

Figure 3.

Evoked field potentials in the hippocampus from first, second, and third pulse trains of BLA stimulation. Traces of local field potentials recorded from CA3 and CA1 during the first (top panel), second (middle panel), and third (bottom panel) 4-pulse train of ipsilateral (left column in each panel) or contralateral (middle column in each panel) 50 Hz stimulation were averaged within rats and then averaged across rats. Each pulse of ipsilateral but not contralateral BLA stimulation evoked, about 24 ms later, prominent negative potentials in CA3 (bottom row in each panel) and smaller but reliable positive potentials in CA1 (top row in each panel). For each 4-pulse train, the stimulation artifact visible for both ipsilateral and contralateral stimulation was largely eliminated when the mean ipsilateral-contralateral difference was calculated for each rat and then averaged (right column). The magnitude of the evoked response in both CA3 and CA1 to the first ipsilateral pulse from each train increased from the first to second 4-pulse train but did not appreciably increase further from the second to third 4-pulse train. Inverted triangles indicate each pulse. Shaded bands above and below the mean indicate SEM in each panel (n = 5).

In addition to the observation that the evoked responses in the hippocampal local field potentials were almost exclusive to ipsilateral BLA stimulation, several additional observations argued against the possibility that these responses reflected artifacts of electrical stimulation. First, the evoked responses following ipsilateral BLA stimulation were negative in CA3 and positive in CA1, and this opposite polarity suggests that the evoked responses were not artifacts of electrical stimulation since such artifacts would likely have the same polarity in this preparation. Second, the data in Figure 3 indicates that the first pulse in each ipsilateral 4-pulse train resulted in an evoked response in both CA3 and CA1 at a delay of about 24 ms (range across rats = 22 to 34 ms), a delay inconsistent with antidromic stimulation of the hippocampus. Third, the magnitude of the evoked response in both CA3 and CA1 to this first pulse increased from the first to second 4-pulse train but did not appreciably increase further from the second to third 4-pulse train, suggesting that the full triggering of responses in the hippocampus by BLA stimulation was rapid but not immediate. This increase across pulse trains is more consistent with a true evoked response rather than an electrical artifact. Thus, although the current data cannot reveal the impact of BLA stimulation in the BLA, the data strongly argue against the possibility that the downstream effects in the hippocampus were attributable to an artifact of the electrical stimulation.

Ipsilateral BLA Stimulation Elicited Low Gamma Coherence between CA3 and CA1

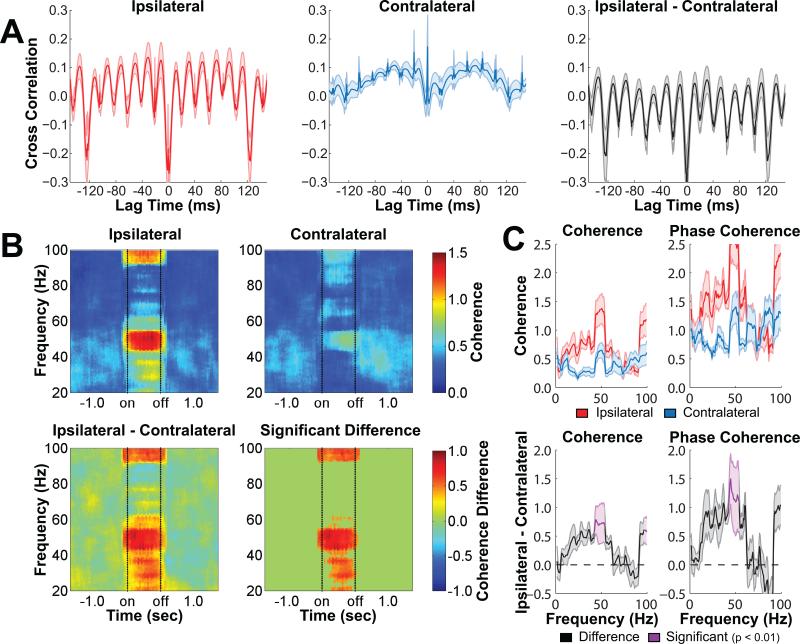

Based on the current and previous results linking novel object exploration to low gamma synchrony in the hippocampus, we asked whether stimulation of the BLA at 50 Hz after the offset of object exploration in the current study also elicited increased CA3-CA1 low gamma coherence in the hippocampus. Figure 4 shows measures of synchrony between local field potentials recorded in hippocampal areas CA3 and CA1 during ipsilateral and contralateral BLA stimulation. For both conditions, CA3-CA1 coherence in the gamma range was low immediately prior to stimulation, consistent with our prior observation (Trimper et al., 2014) that CA3-CA1 low gamma coherence returned to low levels at the cessation of object exploration. Ipsilateral but not contralateral BLA stimulation resulted in a large increase in CA3-CA1 low gamma synchrony as visible by cross-correlations, coherence, and phase coherence. For the low gamma range, the difference between ipsilateral and contralateral synchrony was statistically significant (p < 0.01) when evaluated with a cluster-based randomization procedure that accounted for multiple comparisons (see Method for details). These results suggest that stimulation of the BLA after exploration of an object may influence consolidation of the memory for that object encounter in part by eliciting CA3-CA1 low gamma synchrony in a region of the hippocampus previously shown to be necessary for the beneficial effects of BLA stimulation (Bass et al., 2014).

Figure 4.

Gamma synchrony between CA3 and CA1 increased during stimulation of the BLA. A, A prominent low gamma frequency oscillation is observed in the cross-correlation between CA3 and CA1 during ipsilateral but not contralateral BLA stimulation. Subtracting the contralateral results from the ipsilateral results removed the stimulation artifact but left the low gamma oscillation largely unchanged. Shaded bands above and below the mean indicate SEM (n = 5). B, A moving time window coherogram shows that local field potentials in CA3 and CA1 of the hippocampus synchronized in the low gamma range to a much greater extent during ipsilateral stimulation as compared to contralateral stimulation. The bottom left panel shows the ipsilateral-contralateral difference in coherence, and the bottom right panel shows only pixels from the same contrast that were statistically significant (p < 0.01) when evaluated using a cluster-based randomization procedure. C, The top panels show mean coherence (left) and phase coherence (right) during ipsilateral stimulation (red) and contralateral stimulation (blue). The bottom panels show the difference between ipsilateral and contralateral stimulation, and frequency bands that were statistically significant (p < 0.01) when evaluated using a cluster-based randomization procedure are highlighted in purple. Note: the response visible in the coherence plots at around 90-100 Hz reflects a harmonic introduced by the Fourier transform of the response in the low gamma range. Shaded bands above and below the mean indicate SEM (n = 5).

Several additional analyses indicated that these ipsilateral-contralateral results were not due to spurious effects of the stimulation artifact or the artifact template subtraction approach. First, to ask whether the stimulation artifact in the absence of any evoked hippocampal response could have produced the results observed in Figure 4, the 32 pulse artifacts (each lasting 3.3 ms) from each 1 s bout of stimulation were copied and inserted 5 s later into the same CA3 or CA1 local field potential (see Supplemental Figure 2). When using the same cluster-based randomization procedure to assess ipsilateral-contralateral differences in a moving window coherogram, virtually no differences were observed and no clusters reached statistical significance. Thus, the artifact alone could not account for the results. Second, to ask if the artifact template subtraction introduced spurious results, the moving window cohereograms shown in Figure 4 were recalculated without first subtracting the artifact template (see Supplemental Figure 3). Increased 50 Hz artifact was visible for both ipsilateral and contralateral BLA stimulation, but the ipsilateral-contralateral difference was very similar to the data plotted in Figure 4, indicating that the artifact subtraction procedure did not introduce spurious ipsilateral-contralateral differences.

Nevertheless, overlap of the 50-Hz pulse frequency of the BLA stimulation and the frequency of the oscillatory synchrony observed in the hippocampus raised the possibility that the stimulation artifact may have partially obscured or exaggerated the neural results. To address this possibility, the BLA was stimulated with the same stimulation parameters as before except that the pulse frequency was changed to 80 Hz as a subset (n = 4) of the rats completed laps on an empty circular track. Similar to 50 Hz stimulation condition, each initial pulse in the 80 Hz stimulation condition resulted in an evoked response in the hippocampus about 23 ms later (range across rats = 22 to 24 ms). Figure 5 shows CA3-CA1 coherence during ipsilateral and contralateral 80-Hz BLA stimulation. As compared to contralateral stimulation, ipsilateral BLA stimulation corresponded to a large and statistically significant (p < 0.01) increase in CA3-CA1 coherence in the low gamma range as well as in a frequency range centered at 80 Hz. The ~40 Hz response elicited by 80 Hz stimulation is unlikely to reflect a spurious “harmonic” because Fourier transforms produce harmonics above, not below, the fundamental frequency and because no ~25 Hz coherence was visible during 50 Hz stimulation. Thus, stimulation of the ipsilateral BLA at either 50 Hz (Figure 4) or 80 Hz (Figure 5) resulted in marked increases in intra-hippocampal synchrony in the same low gamma range (~30-55 Hz) observed during novel object exploration (Figure 2), the same low gamma range previously found to correspond to good subsequent memory for the objects (Trimper et al., 2014).

Figure 5.

Gamma synchrony between CA3 and CA1 increased during stimulation of the BLA at 80 Hz. A moving time window coherogram shows that local field potentials in CA3 and CA1 of the hippocampus synchronized in the low gamma range as well as in the 80 Hz range to a much greater extent during ipsilateral stimulation as compared to contralateral stimulation. The bottom left panel shows the ipsilateral-contralateral difference in coherence, and the bottom right panel shows only pixels from the same contrast that were statistically significant (p < 0.01) when evaluated using a cluster-based randomization procedure (n = 4). The results indicate that the increased CA3-CA1 low gamma coherence observed 50-Hz BLA stimulation did not depend on using a stimulation frequency in the low gamma range.

BLA-triggered Hippocampal Gamma Synchrony Coordinated CA3 Pyramidal Action Potentials with Downstream CA1 Local Field Potentials

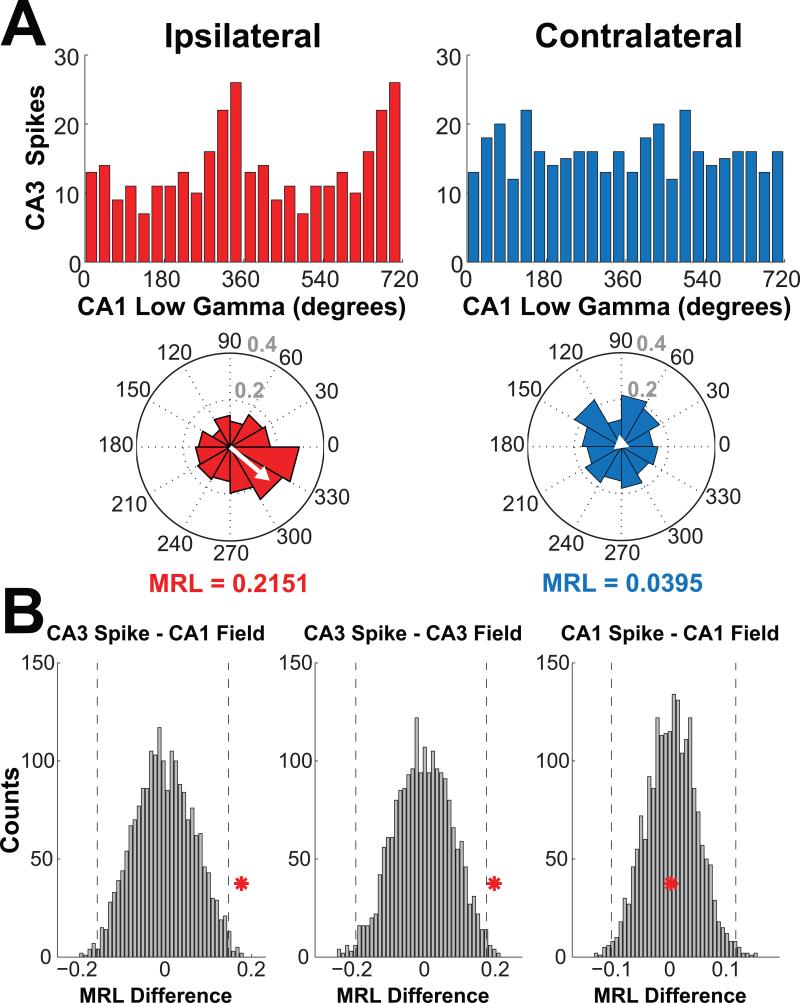

The current results from local field potentials in the hippocampus suggested that BLA stimulation enhanced memory consolidation in part by eliciting a state of synchrony between CA3 and its main downstream target, CA1. Previous research has indicated that a synchronous network state can enhance processes related to cellular memory consolidation to the extent that it results in action potentials that are well-timed with the post-synaptic membrane potential and that gamma oscillations are important for this timing (Bi & Poo, 1998; Buzsáki & Draguhn, 2004; Jutras & Buffalo, 2010; Markram, Gerstner, & Sjöström, 2011). Accordingly, Figure 6 shows spiking data from CA3 hippocampal pyramidal units during ipsilateral and contralateral BLA stimulation as a function of the phase of the low gamma oscillation in CA1 at which the spikes occurred. The distribution of spike phases showed clear periodicity during ipsilateral but not contralateral BLA stimulation, and when the degree of periodicity in each was quantified as the mean resultant length (MRL) of the resultant vector (see Method), the ipsilateral-contralateral difference was statistically significant when evaluated with a random shuffling approach (Fig. 6B; MRL = 0.2151 and 0.0395 for ipsilateral and contralateral, respectively; difference = 0.1756; Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval of difference under null hypothesis = −0.1635 to 0.1454). The MRL during ipsilateral BLA stimulation was also significantly greater than the MRL for the 1 s immediately preceding ipsilateral stimulation (MRL = 0.0542; difference = 0.1609; Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval of difference under null hypothesis = −0.1089 to 0.1111). Thus, the greater MRL for ipsilateral versus contralateral BLA stimulation appeared to have occurred not because contralateral BLA stimulation disrupted hippocampal spike timing but because ipsilateral stimulation elicited increased CA3-CA1 spike-field alignment in the low gamma range. Figure 6 also shows the ipsilateral-contralateral spike-field low gamma phase differences for CA3-CA3 and for CA1-CA1 (CA1-CA3 was not evaluated because CA1 does not project to CA3). The graphs (Fig. 6B) indicate that the ipsilateral-contralateral difference was statistically significant for CA3-CA3 (MRL = 0.2429 and 0.1076 for ipsilateral and contralateral, respectively; difference = 0.1353; Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval of difference under null hypothesis = −0.09710 to 0.0997) but not for CA1-CA1 (MRL = 0.1177 and 0.0380 for ipsilateral and contralateral, respectively; difference = 0.0797; Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval of difference under null hypothesis = −0.0808 to 0.0817). The results did not differ when phase preference was recalculated using pairwise-phase consistency (PPC), an unbiased estimator of phase preference (Vinck et al., 2010), instead of MRL.

Figure 6.

Gamma synchrony between CA3 pyramidal neuron spikes and CA1 local field potentials increased during stimulation of the BLA. A, Histograms in both standard (top row) and circular (bottom row) format show distributions of CA3 spike phases of low gamma (30-55 Hz) oscillations in the downstream CA1 field potential during ipsilateral and contralateral BLA stimulation. The white arrows on the circular histograms show the mean resultant vector, and the mean resultant length (MRL) of that vector indicates the strength of phase preference. B, To determine whether the MRL was significantly greater for ipsilateral as compared to contralateral BLA stimulation, the ipsilateral-contralateral difference was obtained from 2000 random shuffles of the data and a distribution of these random MRL difference was plotted for spike-field phases for CA3-CA1 (left), CA3-CA3 (middle), and CA1-CA1 (right). The red asterisk on each plot indicates the actual difference, and vertical dashed lines indicate the threshold for statistical significance (see Method). The ipsilateral-contralateral low gamma MRL difference was significantly greater than chance for CA3-CA1 and CA3-CA3 spike-field phases.

These results indicated that ipsilateral BLA stimulation elicited gamma synchrony in the hippocampus such that CA3 spikes were well timed with CA3 and downstream CA1 low gamma oscillations. However, one alternate possibility was that the pulses from ipsilateral stimulation arrived consistently during one phase of the low gamma oscillation and that the arrival of pulses during contralateral stimulation was more variable. Greater pulse phase consistency could have resulted in a more phase-specific loss of spike data during ipsilateral stimulation, potentially accounting for the difference in the strength of the phase preference between ipsilateral and contralateral stimulation. To address this possibility, the hypothetical phases of spikes that might have been lost to the pulse artifact during ipsilateral stimulation were estimated by identifying spikes that were recorded during the corresponding phase of contralateral trials. The mirror opposite procedure was performed to estimate spikes that were lost to contralateral stimulation. The ipsilateral-contralateral MRL differences were then evaluated using the same shuffling procedure as before. The results of this analysis indicated that the CA3-CA1 spike-phase ipsilateral-contralateral difference was still statistically significant (MRL = 0.1453 and 0.0328 for ipsilateral and contralateral, respectively; difference = 0.1124; Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval of difference under null hypothesis = −0.1166 to 0.1084), though the CA3-CA3 spike-phase ipsilateral-contralateral difference fell short of statistical significance (MRL = 0.1929 and 0.0560 for ipsilateral and contralateral, respectively; difference = 0.1369; Bonferroni-corrected 95% confidence interval of difference under null hypothesis = −0.1704 to 0.1449). Thus, the greater CA3-CA1 spike-phase alignment during ipsilateral as compared to contralateral BLA stimulation cannot be accounted for by spurious loss of spike data during the stimulation artifact.

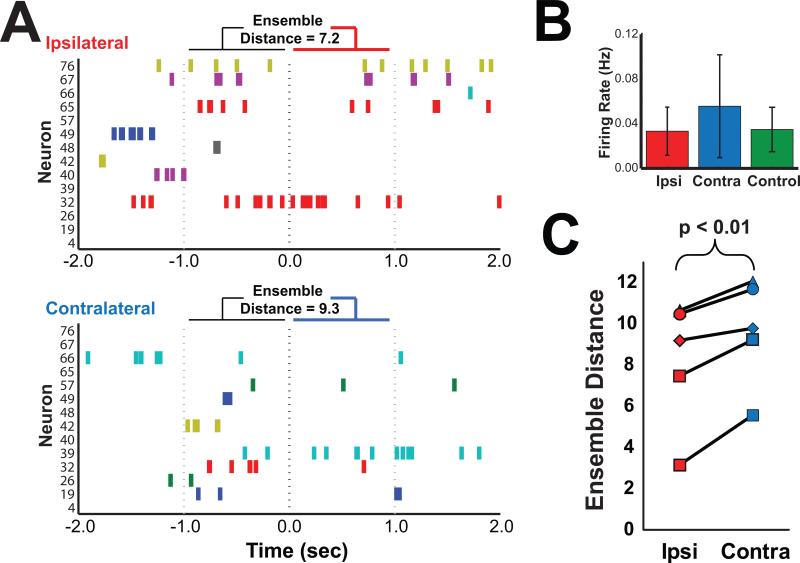

Ipsilateral BLA Stimulation Was Associated with Recently Active Hippocampal Neurons

Figure 7 shows firing rates of hippocampal pyramidal neurons during object exploration and BLA stimulation and indicates that neither ipsilateral nor contralateral BLA stimulation significantly altered firing rates as compared to control time periods (mean ± SEM; Ipsilateral = 0.033 Hz ± 0.008; Contralateral = 0.056 ± 0.017; Control = 0.035 ± 0.008; Ipsilateral vs. Contralateral: t(6) = 0.891, p > 0.1; Ipsilateral vs. Control: t(6) = 0.442, p > 0.1; Contralateral vs. Control: t(6) = 0.791, p > 0.1). However, ipsilateral BLA stimulation did appear to influence the pattern of spiking activity across many simultaneously recorded pyramidal neurons (see Method for details; the number of simultaneously recorded pyramidal cells per rat with at least 20 ranged from 39 to 112). Specifically, the pattern of spiking across simultaneously-recorded pyramidal neurons in both CA1 and CA3 was more similar to the recent (1 s) past for ipsilateral as compared to contralateral BLA stimulation as measured by a multivariate neuronal ensemble distance, suggesting that the increased spike-field alignment during ipsilateral BLA stimulation would have preferentially benefitted recently active neurons. These results provide evidence that one mechanism by which BLA stimulation immediately after exploration of a novel object selectively benefitted 1-day memory for that object was by coordinating the timing of synaptic transmission between CA3 and CA1 via putative synapses between recently active neurons at a time scale amenable to spike-timing dependent plasticity.

Figure 7.

Hippocampal pyramidal neuron firing rates did not differ between ipsilateral and contralateral BLA stimulation but ipsilateral BLA stimulation was more associated with recent patterns of activity of hippocampal neurons. A, Perievent rasters show example spiking activity from active CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons before and during one ipsilateral and one contralateral BLA stimulation. The numbers above each raster indicate the multi-dimensional distance between spike patterns in each epoch, a measurement of how similar (lower = more similar) the pattern of activity was between the stimulation period (0 to +1 s) and the 1 s baseline (−1 to 0 s) preceding stimulation. B, The mean firing rate of each CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cell was averaged within condition and then across rats (n=7) during stimulation. Control stimulation was defined as the 1 s period after exploration of New objects when the rat would have received stimulation on that trial had the object been a Stimulation object. The results show that stimulation did not impact the firing rate of pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus (see Results; all ps > 0.1). Units that were not active during object exploration, stimulation, or the sham stimulation were not included in analyses. Error bars show the SEM across rats (n = 7). C, The mean baseline-stimulation ensemble distance for combined CA1 (n=189) and CA3 (n=163) pyramidal neurons is plotted for ipsilateral and contralateral stimulation for 5 rats each with > 20 pyramidal neurons (ns = 39, 42, 72, 87, and 112) and indicates greater similarity between stimulation and baseline periods for the ipsilateral BLA stimulation (p < 0.01).

Discussion

Although activation of the amygdala was well known to modulate memory consolidation (McGaugh, 2004), very little was previously known about how it influenced neuronal activity in the hippocampus to enhance memory for events. The present study replicated the finding from two previous studies (Bass et al., 2014, 2012) that brief electrical stimulation of the BLA following the offset of exploration of novel objects led to improved memory for those object encounters one day later. The present study also extended those findings by showing that the BLA stimulation elicited robust gamma synchrony in a region of the hippocampus that was previously shown to be necessary for BLA-mediated enhancement of recognition memory (Bass et al., 2014). Specifically, BLA stimulation triggered increased coherence in the low gamma range (~30-55 Hz) between local field potentials in CA3 and CA1 and also led to increased phase alignment in the same gamma range between action potentials emitted by CA3 pyramidal neurons and the downstream field potentials recorded in CA1. Further, BLA stimulation tended to be associated with spiking of hippocampal pyramidal neurons that were recently active. Thus, the present study provided important evidence that amygdala activation could prioritize consolidation of memories for specific events by inducing a transient state of field-field and spike-field gamma synchrony in the hippocampus that could have benefitted spike-timing dependent plasticity for recently active neurons.

These findings are consistent with the view that neural oscillations throughout the brain facilitate synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity by coordinating spike timing (Fell & Axmacher, 2011; Fries, 2005; Jutras & Buffalo, 2010). Indeed, there is a growing body of evidence indicating that synchronization of gamma oscillations between the amygdala and other memory structures during learning correlates with better memory performance (Bauer, Paz, & Pare, 2007; Popescu, Popa, & Pare, 2009) and that gamma synchronization specifically within the hippocampus during encoding correlates with subsequent good memory (Fell et al., 2001; Jutras et al., 2009; Trimper et al., 2014). In particular, a recent study in rats found that low gamma oscillations in CA3 and CA1 synchronized during novel object exploration (similar to the present results in Figure 2) and that this gamma synchrony strongly related to subsequent memory for those objects (Trimper et al., 2014). Moreover, in the present study BLA stimulation at either 50 Hz or 80 Hz elicited an increase in CA3-CA1 coherence in the low gamma (~30-55 Hz) range, suggesting that amygdala activation may wield a somewhat generalized capacity for inducing gamma synchrony in the hippocampus in the same low gamma range that corresponds with good memory.

In the present study and previous two related studies (Bass et al., 2014, 2012), BLA stimulations were brief (1 s), were closely timed to the end of the object encounters (within ~1 s), and were interleaved at intervals of less than a minute with object encounters that were not followed by stimulation and saw no subsequent memory improvement. Thus, to the extent that the BLA stimulation influenced memory for some objects but not others encountered close in time, there appeared to be a temporal specificity on the order of seconds to the influence of the BLA stimulation. Also similar to the previous two studies, the benefit to memory of BLA stimulation was apparent on a memory test given one day later but not on one given immediately after the end of the study phase. Thus, consistent with the post-exploration delivery of the stimulation and with much of the previous work on amygdala activation (Gold et al., 1975; McGaugh & Roozendaal, 2009; Packard, Cahill, & McGaugh, 1994; Roozendaal, Castello, Vedana, Barsegyan, & McGaugh, 2008), BLA stimulation in the present study did not appear to boost encoding generally but instead appeared to enhance consolidation of the memory specifically. One possibility, similar to the notion of “emotional tagging” (Bergado, Lucas, & Richter-Levin, 2011), is that BLA stimulation enhanced ipsilateral CA3-CA1 spike-field gamma synchrony in such a way that it rapidly initiated slowly-unfolding molecular cascades related to cellular consolidation in the hippocampus—particularly for recently active neurons. The lack of an effect of BLA stimulation on the Immediate Test also strongly argues against the possibility that stimulation elicited aversions to the objects akin to fear conditioning (see Bass et al., 2012, 2014 for further discussion of this point). In particular, rats showed no tendency to avoid Stimulation objects on the Immediate Test.

Enhancement of memory during an emotional experience is a complex process that engages many amygdala-mediated mechanisms in order to prioritize important information for long-term storage, mechanisms including modulation of attention, perception, and downstream release of peripheral stress hormones that can directly or indirectly feed back into the central nervous system to further enhance consolidation (McGaugh, 2004; Phelps & Ledoux, 2005; Talmi, 2013). The present study used direct stimulation of the BLA immediately after encounters with non-aversive novel objects to focus on the amygdala’s more specific impact on memory processes. Indeed, the absence of substantive effects in the hippocampus triggered by contralateral BLA stimulation suggests that moderating factors that would have influenced both hemispheres, factors such as overt behavior, alertness, perceived aversions, or circulating hormones, did not mediate the current results for ipsilateral BLA stimulation.

Nevertheless, in addition to the direct projections to the hippocampus, the BLA has many other ipsilateral neuronal projections throughout the brain (Petrovich et al., 2001; Pikkarainen et al., 1999). For example, the BLA projects strongly to both the entorhinal cortex and to the perirhinal cortex (Pitkanen, Pikkarainen, Nurminen, & Ylinen, 2000). The perirhinal cortex projects heavily to entorhinal cortex, which provides the majority of cortical inputs to the hippocampus (Burwell, 2000). Accordingly, BLA stimulation could directly influence activity in the hippocampus but could also indirectly influence activity in the hippocampus by modulating its inputs from the perirhinal and entorhinal cortices (de Curtis & Pare, 2004; Kajiwara, Takashima, Mimura, Witter, & Iijima, 2003). Other indirect routes could also be possible, and an important question for future studies is which structures outside the hippocampus are also engaged by the BLA stimulation. In any case, a recent study (Bass et al., 2014) found that inactivating the hippocampus blocked the memory-enhancing effect of BLA stimulation, and thus the results indicated that the influence of BLA stimulation on hippocampal activity was necessary for the memory enhancement regardless of whether the effect was triggered monosynaptically or polysynaptically. The results of this recent study are also important in the context of the debate as to whether the hippocampus is normally essential for simple recognition memory judgments (Brown & Aggleton, 2001; Eichenbaum, Yonelinas, & Ranganath, 2007; Squire, Wixted, & Clark, 2007). A case can be made that the hippocampus is important even for normal object recognition memory in rats (e.g., Broadbent, Gaskin, Squire, & Clark, 2010), but the most directly relevant result (Bass et al., 2014) is that the hippocampus is necessary for the same type of BLA-mediated enhancement of object recognition memory as observed in the present study.

In summary, modulation of the hippocampus by the amygdala during an emotional event is thought to represent an endogenous mechanism of memory enhancement for information that would often be important for survival of the organism (McGaugh, 2013). However, little was previously known about how activation of the amygdala influences neuronal activity in the hippocampus. Although BLA stimulation in the present study certainly did not recreate an everyday emotional experience, it modeled the memory-enhancing effect of amygdala activation during emotional events. The fundamental contribution of the current study is thus to identify CA3-CA1 hippocampal field-field and spike-field gamma synchrony as potential underlying mechanisms of an amygdala-triggered network state that prioritizes recently-encoded information for long-term memory storage. Further work will be needed to determine if the results obtained here would generalize to other protocols of amygdala stimulation (e.g., other frequencies) or even to stimulation of other major hippocampal afferents such as the entorhinal cortex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Kristin Partain, Arick Wang, Zainab Nizam, and Anna Rogers for their help with and feedback on behavioral testing. The research was supported by an Emory University Research Committee Grant and NIH Grant R01MH100318 to J.R.M. and an NIMH NRSA Fellowship Grant F30 MH095491 to D.I.B.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Akirav I, Richter-Levin G. Priming stimulation in the basolateral amygdala modulates synaptic plasticity in the rat dentate gyrus. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;270:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00488-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass DI, Nizam ZG, Partain KN, Wang A, Manns JR. Amygdala-mediated enhancement of memory for specific events depends on the hippocampus. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2014;107:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass DI, Partain KN, Manns JR. Event-specific enhancement of memory via brief electrical stimulation to the basolateral complex of the amygdala in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;126(1):204–208. doi: 10.1037/a0026462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bast T, Wilson IA, Witter MP, Morris RGM. From rapid place learning to behavioral performance: a key role for the intermediate hippocampus. PLoS Biology. 2009;7(4):e1000089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer EP, Paz R, Pare D. Gamma Oscillations Coordinate Amygdalo-Rhinal Interactions during Learning. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(35):9369–9379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2153-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergado JA, Lucas M, Richter-Levin G. Emotional tagging--a simple hypothesis in a complex reality. Progress in Neurobiology. 2011;94(1):64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi GQ, Poo MM. Synaptic modifications in cultured hippocampal neurons: dependence on spike timing, synaptic strength, and postsynaptic cell type. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18(24):10464–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10464.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokil H, Andrews P, Kulkarni JE, Mehta S, Mitra PP. Chronux: a platform for analyzing neural signals. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2010;192(1):146–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.06.020. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokil H, Purpura K, Schoffelen J-M, Thomson D, Mitra P. Comparing spectra and coherences for groups of unequal size. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2007;159(2):337–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent NJ, Gaskin S, Squire LR, Clark RE. Object recognition memory and the rodent hippocampus. Learning & Memory. 2010;17(1):5–11. doi: 10.1101/lm.1650110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MW, Aggleton JP. Recognition Memory : What are the Roles of the Perirhinal Cortex and Hippocampus? Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2(1):51–61. doi: 10.1038/35049064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RD. The Parahippocampal Region : Corticocortical Connectivity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2000;11:25–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, Draguhn A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science. 2004;304(5679):1926–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1099745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, McGaugh JL. Mechanisms of emotional arousal and lasting declarative memory. Trends in Neurosciences. 1998;21(7):294–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgin LL, Denninger T, Fyhn M, Hafting T, Bonnevie T, Jensen O, Moser EI. Frequency of gamma oscillations routes flow of information in the hippocampus. Nature. 2009;462(7271):353–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Czurko A, Buzsáki G. Reliability and state dependence of pyramidal cell-interneuron synapses in the hippocampus: an ensemble approach in the behaving rat. Neuron. 1998;21(1):179–89. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csicsvari J, Jamieson B, Wise KD, Buzsáki G. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. Neuron. 2003;37(2):311–22. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Curtis M, Pare D. The rhinal cortices: a wall of inhibition between the neocortex and the hippocampus. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004;74:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudai Y. The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram? Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:51–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Yonelinas AR, Ranganath C. The Medial Temporal Lobe and Recognition Memory. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2007;30:123–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell J, Axmacher N. The role of phase synchronization in memory processes. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2011;12(2):105–118. doi: 10.1038/nrn2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell J, Klaver P, Lehnertz K, Grunwald T, Schaller C, Elger CE, Fernández G. Human memory formation is accompanied by rhinal-hippocampal coupling and decoupling. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4(12):1259–64. doi: 10.1038/nn759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SE, Ranck JBJ. Electrophysiological characteristics of hippocampal complex-spike cells and theta cells.pdf. Exp Brain Res. 1981;41:399–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00238898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey S, Bergado-Rosado J, Seidenbecher T, Pape H, Frey JU. Reinforcement of early long-term potentiation (early-LTP) in dentate gyrus by stimulation of the basolateral amygdala: heterosynaptic induction mechanisms of late-LTP. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(10):3697–703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03697.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P. A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: neuronal communication through neuronal coherence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9(10):474–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway CR, Lebois EP, Shagarabi SL, Hernandez N. a, Manns JR. Effects of selective activation of m1 and m4 muscarinic receptors on object recognition memory performance in rats. Pharmacology. 2014;93(1-2):57–64. doi: 10.1159/000357682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard GV. Amygdaloid Stimulation and Learning in the Rat. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1964;58(1):23–30. doi: 10.1037/h0049256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold PE, Hankins L, Edwards RM, Chester J, McGaugh JL. Memory Interference and Facilitation with Posttrial Amygdala Stimulation: Effects on Memory Varies with Footshock Level. Brain Research. 1975;86:509–513. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90905-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado JM, Rubchinsky LL, Sigvardt KA. Statistical method for detection of phase-locking episodes in neural oscillations. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;91(4):1883–98. doi: 10.1152/jn.00853.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegaya Y, Saito H, Abe K. High-frequency stimulation of the basolateral amygdala facilitates the induction of long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus in vivo. Neuroscience Research. 1995;22(2):203–7. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00894-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutras MJ, Buffalo EA. Synchronous neural activity and memory formation. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2010;20(2):150–5. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutras MJ, Fries P, Buffalo EA. Gamma-band synchronization in the macaque hippocampus and memory formation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(40):12521–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0640-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiwara R, Takashima I, Mimura Y, Witter MP, Iijima T. Amygdala Input Promotes Spread of Excitatory Neural Activity From Perirhinal Cortex to the Entorhinal – Hippocampal Circuit. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003;89:2176–2184. doi: 10.1152/jn.01033.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP. Brain stimulation: effects on memory. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1982;36(4):315–67. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(82)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns JR, Eichenbaum H. A cognitive map for object memory in the hippocampus A cognitive map for object memory in the hippocampus. Learning & Memory. 2009;16:616–624. doi: 10.1101/lm.1484509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris E, Oostenveld R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2007;164(1):177–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Gerstner W, Sjöström PJ. A history of spike-timing-dependent plasticity. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience. 2011;3(8):4. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2011.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. The Amygdala Modulates the Consolidation of Memories of Emotionally Arousing Experiences. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2004;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. Making lasting memories: Remembering the significant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(Suppl):10402–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301209110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL, Roozendaal B. Drug enhancement of memory consolidation: historical perspective and neurobiological implications. Psychopharmacology. 2009;202:3–14. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CK, Miyashita T, Setlow B, Marjon KD, Steward O, Guzowski JF, McGaugh JL. Memory-influencing intra-basolateral amygdala drug infusions modulate expression of Arc protein in the hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102(30):10718–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504436102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McReynolds JR, Anderson KM, Donowho KM, McIntyre CK. Noradrenergic actions in the basolateral complex of the amygdala modulate Arc expression in hippocampal synapses and consolidation of aversive and non-aversive memory. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2014;115:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery EB, Gale JT, Huang H. Methods for isolating extracellular action potentials and removing stimulus artifacts from microelectrode recordings of neurons requiring minimal operator intervention. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2005;144(1):107–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG, Cahill L, McGaugh JL. Amygdala modulation of hippocampal- dependent and caudate nucleus-dependent memory processes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994;91:8477–8481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare D. Role of the basolateral amygdala in memory consolidation. Progress in Neurobiology. 2003;70(5):409–420. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovich GD, Canteras NS, Swanson LW. Combinatorial amygdalar inputs to hippocampal domains and hypothalamic behavior systems. Brain Research Reviews. 2001;38(11):247–289. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, Ledoux JE. Contributions of the Amygdala to Emotion Processing: From Animal Models to Human Behavior. Neuron. 2005;48:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikkarainen M, Ronkko S, Savander V, Ricardo I, Pitkanen A. Projections From the Lateral , Basal , and Accessory Basal Nuclei of the Amygdala to the Hippocampal Formation in Rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1999;403(4):229–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A, Pikkarainen M, Nurminen N, Ylinen A. Reciprocal Connections between the Amygdala and the Hippocampal Formation, Perirhinal Cortex, and Postrhinal Cortex in Rat. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2000;911:369–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu AT, Popa D, Pare D. Coherent gamma oscillations couple the amygdala and striatum during learning. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12(6):801–808. doi: 10.1038/nn.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, Castello NA, Vedana G, Barsegyan A, McGaugh JL. Noradrenergic activation of the basolateral amygdala modulates consolidation of object recognition memory. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2008;90:576–579. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirvalkar PR, Rapp PR, Shapiro ML. Bidirectional changes to hippocampal theta-gamma comodulation predict memory for recent spatial episodes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(15):7054–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911184107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Wixted JT, Clark RE. Recognition memory and the medial temporal lobe: a new perspective. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8(11):872–83. doi: 10.1038/nrn2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmi D. Enhanced Emotional Memory: Cognitive and Neural Mechanisms. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22(6):430–436. [Google Scholar]

- Tort ABL, Komorowski RW, Manns JR, Kopell NJ, Eichenbaum H. Theta-gamma coupling increases during the learning of item-context associations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(49):20942–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911331106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimper JB, Stefanescu RA, Manns JR. Recognition memory and theta-gamma interactions in the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2014;24(3):341–53. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien NM, Cappaert NLM, Witter MP. The anatomy of memory: an interactive overview of the parahippocampal-hippocampal network. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(4):272–82. doi: 10.1038/nrn2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinck M, van Wingerden M, Womelsdorf T, Fries P, Pennartz C. M. a. The pairwise phase consistency: a bias-free measure of rhythmic neuronal synchronization. NeuroImage. 2010;51(1):112–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann T. A digital averaging method for removal of stimulus artifacts in neurophysiologic experiments. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2000;98(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.