Abstract

Patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection have been reported to have parotid swellings of various types such as diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome, parotitis, intraparotid lymphadenopathy, benign lymphoepithelial cyst (BLEC), as well as salivary gland neoplasms such as adenoid cystic carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma and lymphoma. LECs in the parotid gland are uncommon benign entities with increased incidence associated with HIV infection. We are presenting a case of 28-year-old HIV-positive patient with BLECs in the parotid and submandibular glands.

Keywords: HIV, lymphoepithelial cysts lymphocytosis, salivary glands

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection can be called the epidemic of the 20th century. It was reported initially that 41% of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) had head and neck manifestations. Salivary gland diseases (SGDs) are important diagnostic and prognostic indicators in HIV infection. Patients with HIV infection have been reported to have parotid swellings of various types such as diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome, parotitis, intraparotid lymphadenopathy, benign lymphoepithelial cyst (BLEC), as well as salivary gland neoplasms such as adenoid cystic carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma and lymphoma. LECs in the parotid gland are uncommon benign entities with increased incidence associated with HIV infection. The lesions are thought to reflect a localized manifestation of persistent generalized lymphadenopathy associated with HIV infection.[1,2]

Although Mickulicz is credited with the first description of salivary gland lymphoepithelial lesion (LEL) in 1885; Ryan et al., first identified this condition in HIV-positive patients in 1985. BLEC has been variably designated as benign lymphoepithelial lesion (BLEL), Sjogren-like lesion, cystic epithelial lesion and HIV SGD.[2]

We are presenting a case of a HIV-positive male, who had BLECs of parotid and submandibular glands with CD8 lymphocytosis to illustrate this rare clinical entity.

CASE REPORT

A 28-year-old male patient reported to the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, with the chief complaint of swelling below and behind both the ears since 1 year. The swellings were sudden in onset which gradually progressed to present size. There was no history of pain or any other associated symptoms. The patient was known HIV-positive since 2 years and was not on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). On general physical examination, he was moderately built and moderately nourished. There was no evidence of involvement of other organs like lungs, liver, kidney, gastrointestinal tract and peripheral nerves. On extraoral examination, diffuse bilateral parotid swellings were present measuring about 4 × 3 cm on right side and 3 × 2.5 cm on left side [Figures 1–3]. Skin over the swelling was slightly erythematous on right side. Surface over the swelling was smooth and stretched. On palpation, the swellings were soft to firm in consistency, nontender and nonfluctuant with no rise in local temperature. The right and left submandibular glands were also enlarged measuring about 3 × 3 cm, which were soft to firm in consistency, nontender and nonfluctuant with no rise in local temperature. Upper cervical lymph nodes were palpable measuring about 4 × 4 cm on each side; and were firm, mobile and nontender.

Figure 1.

Patient's front view

Figure 3.

Parotid swelling on left side

Figure 2.

Parotid swelling on right side

Intraorally there was an erythematous area on the dorsum of tongue and palate. There was no pus discharge from or inflammation of the duct orifice. The salivary flow was decreased with thick copious saliva. Based on history and clinical examination, a provisional diagnosis of HIV-induced chronic sialadenitis involving parotid, submandibular glands and erythematous candidiasis of the tongue and palate were given.

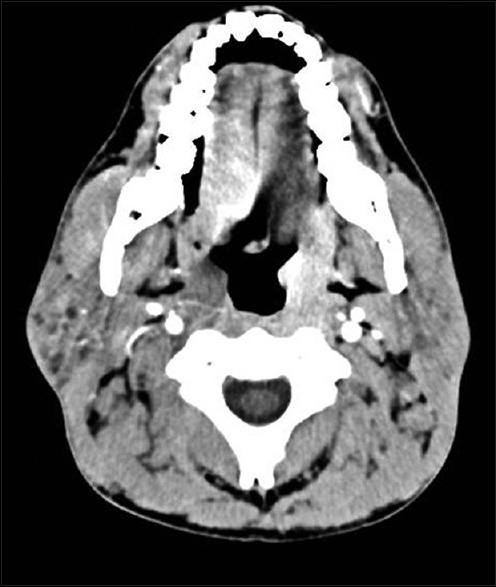

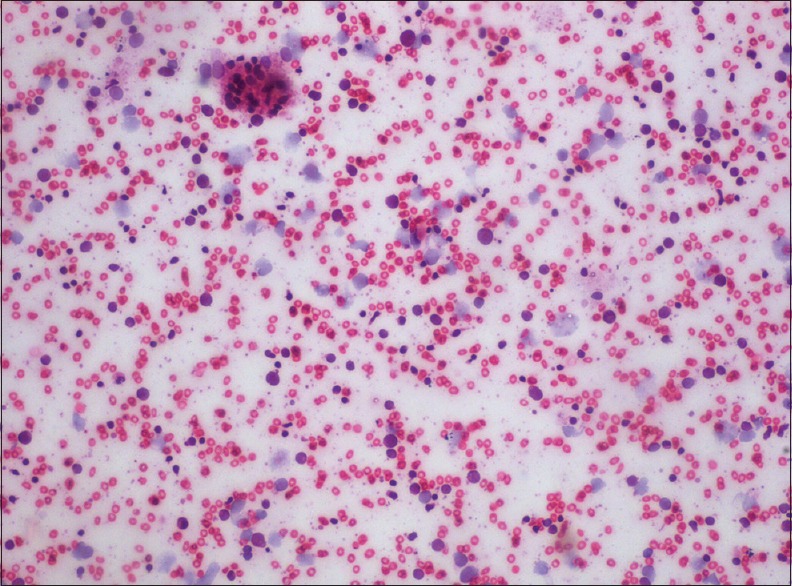

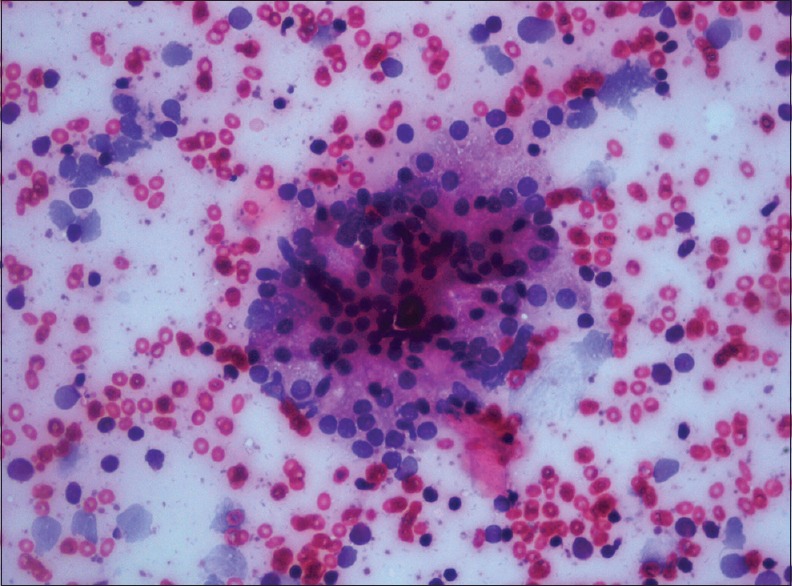

On radiographic investigations; orthopantomograph (OPG), rotated postero-anterior (PA) view and chest X-ray did not reveal any pathology. Ultrasound revealed enlarged parotid and submandibular glands and showed heterogeneous echotexture with multiple, discrete, hypoechoic, subcentimetric rounded cystic lesions within the parenchyma. Ultrasound revealed presence of multiple round to oval, discrete enlarged cervical lymph nodes suggestive of lymphadenopathy. Ultrasound abdomen showed mild splenomegaly with no evidence of any other infiltrative disease. Computed Tomography (CT) scan showed enlarged parotid and submandibular glands with multiple cystic locules and thinned out parenchyma [Figure 4]. Intraglandular lymph nodes were enlarged in both parotid and submandibular glands. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) revealed salivary gland acinar and ductal cells with sheets of lymphocytes [Figures 5 and 6].

Figure 4.

CT showing enlarged parotid and submandibular glands with multiple cystic locules and thinned out parenchyma. CT = Computed tomography

Figure 5.

FNAC showing salivary gland acinar and ductal cells with sheets of lymphocytes (H&E stain, x100). FNAC = Fine-needle aspiration cytology

Figure 6.

FNAC showing salivary gland acinar and ductal cells with sheets of lymphocytes (H&E stain, x400). FNAC = Fine-needle aspiration cytology

Blood investigations revealed: Hemoglobin - 12.1 g%, total leukocyte count (TLC) - 4,600/mm3, differential leukocyte count (DLC) – N56 L40 E01 M02 B01, absolute lymphocyte count -1,440 cells/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) -72 mm at the end of 1 h, CD4 count -148.66 cells/μL and CD8 count-1250 cells/μL with the ratio of CD4/CD8- 0.11. Hypergammaglobulinemia (2.8 g/dl) was present. Patient was negative for RA factor, antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-SS-A (RO) and anti-SS-B (LA). Other counts were within the normal limits.

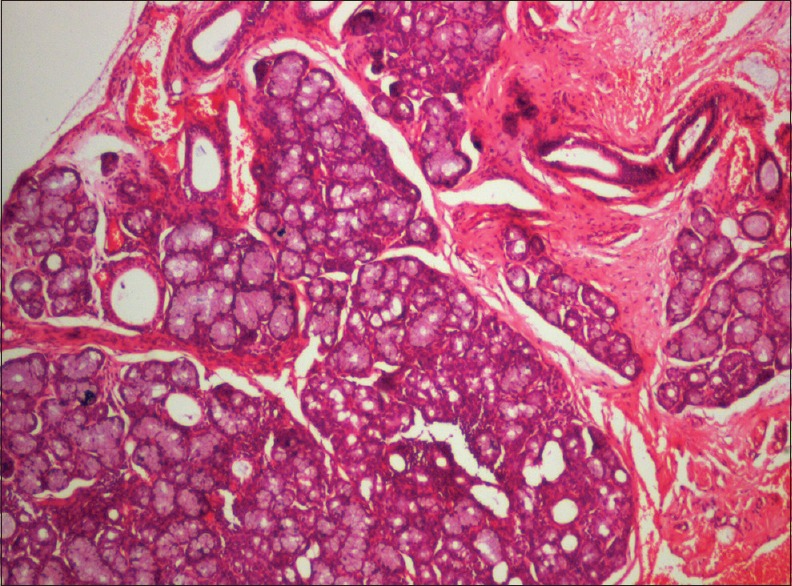

Minor salivary gland biopsy did not show lymphocytic infiltration which ruled out diffuse lymphocytic infiltrative disease and Sjogren syndrome [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Minor salivary gland biopsy did not show lymphocytic infiltration (H&E stain, x40)

The patient's history (bilateral parotid gland swelling for more than 6 months duration); clinical examination; the investigations like the FNAC report showing lymphocytic infiltration with ultrasonographic and CT images confirming cystic degeneration of parotid and submandibular glands; and cervical lymphadenopathy, suggests the possible diagnosis of BLECs affecting bilateral parotid and submandibular glands.

Patient was not ready for any type of surgery related to the disease. He was advised to start HAART and periodic checkup every 6 months.

DISCUSSION

Enlarged salivary glands were first noted by Ryan et al., in 1985 when they described two cases of AIDS-related lymphadenopathies, initially presenting as an enlargement of the parotid glands.[2] Schiodt defined HIV-associated SGD (HIV-SGD) as including major salivary gland enlargement, symptoms of dry mouth, or both. Weinert et al., described this disease as a nontender unilateral or bilateral parotid gland enlargement associated with xerostomia, resulting in dry atrophic oral tissues, caries, periodontitis and mucositis.[3]

Bilateral and multiple LECs of the parotid glands are quite rare in the general population, but have been found in approximately 5% of HIV-infected patients.[2]

The pathophysiology of this disease process is debated. HIV-infected cells migrate into the parotid glands, which triggers lymphoid proliferation, inducing metaplastic changes in the salivary ducts. Cysts form due to ductal obstruction secondary to cellular proliferation. These cysts serve as a reservoir of HIV-1 p24 and ribonucleic acid (RNA) copies that are sometimes 1,000-fold higher than plasma concentrations. A dramatic reduction in HIV-associated BLEL occurs with initiation of HAART.[2,4]

The second hypothesized theory is that HIV-related reactive lymphoproliferation occurs in the lymph nodes of the parotid gland. and submandibular gland. The parotid glandular epithelium becomes trapped in normal intraparotid lymph nodes, resulting in cystic enlargement.[2,5]

Bernier and Bhaskar have defined BLECs as solitary or multiple cysts within lymph nodes trapped during the parotid gland embryogenesis; these represent cystic degeneration of salivary gland inclusions within the intraparotid lymph nodes. The intraparotid gland lymph nodes are largely located along the tail of the gland, thereby predisposing this part of the gland. HIV has a predilection for lymphoid tissue and high concentrations of the virus can be found within these nodes.[2,5]

The LEC has equal distribution in male and female, can be single or multiple and often become very large. They are painless, soft and involve the superficial lobes of the parotid glands, often bilaterally. They gradually increase in size, can cause gross cosmetic deformities and may involve the facial nerve.[5] In our case there was no facial nerve involvement.

Histologically, the cysts are observed in a lymph node, adjacent to or embedded in a major salivary gland. It is characterized by multiple parenchymal cysts of varying size and shape. The cysts were lined with either multiple layers of flattened epithelia or stratified squamous epithelial lining.[2,6]

Enlarged salivary glands caused by a variety of conditions related to HIV are diffuse infiltrative lymphocytic syndrome, sialadenosis, cytomegalovirus infection associated SGD, hepatitis C virus associated SGD and mumps. In addition to HIV disease, the conditions which should be differentiated from this, range from benign neoplasms (such as pleomorphic adenoma and adenolymphoma) to malignant conditions, such as lymphoma, Sjogren's syndrome, alcoholism, endocrinopathies (such as diabetes and acromegaly), cirrhosis, sarcoidosis, malnutrition, anorexia and bulimia and certain infections of viral or bacterial origin.[7]

This disease can be differentiated by diffuse lymphocytic infiltrative syndrome (DILS) by many ways. Involvement of other viscera like chest and liver, positive histologic confirmation from minor salivary glands biopsy showing lymphocytic infiltration in case of DILS, along with positive RA factor and positive antinuclear antibodies (in some cases) are the differentiating points.[8]

Features similar between DILS and BLEC are hypergammaglobinemia, CD8 + lymphocytosis, negative anti-SS-A and negative anti-SS-B.[7,8]

Treatment of this particular pathology has been widely debated in the literature. Previous treatments for BLEC have included repeated fine-needle aspiration and drainage, surgery, radiotherapy, sclerotherapy and conservative therapy with HAART medications.[1,2,4,9,10,11]

A lymphoma can result from activation of existing B-cells in conjunction with dysfunction of the patient's immune system. Sudden increase in gland size heralds a lymphomatous transformation. Hence, a close follow-up of these patients is indicated.[5]

CONCLUSION

Parotid LECs are an important early head and neck manifestation of HIV disease. Treatment often is not necessary due to the benign nature of the disease. In view of the predisposition of HIV-positive patients to the development of malignant lymphoma, periodic monitoring is mandatory.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumar VV, Sharma N. Parotid lymphoepithelial cysts as an indicator of HIV infection. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naidoo M, Singh B, Randial PK, Moodley J, Allopi L, Lester B. Lymphoepithelial lesions of the parotid gland in the HIV era--a South African experience. S Afr J Surg. 2007;45:136–8. 140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulligan R, Navazesh M, Komaroff E, Greenspan D, Redford M, Alves M, et al. Salivary gland disease in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women from the WIHS study. Women's Interagency HIV Study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:702–9. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.105328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uccini S, d’Offizi G, Angelici A, Prozzo A, Riva E, Antonelli G, et al. Cystic lymphoepithelial lesions of the parotid gland In HIV-1 infection. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:143–7. doi: 10.1089/108729100317920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahamed AS, Kannan VS, Velaven K, Sathyanarayanan GR, Roshni J, Elavarasi E. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the submandibular gland. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6:S185–7. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.137464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandel L, Hong J. HIV-associated parotid lymphoepithelial cysts. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:528–32. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Islam NM, Bhattacharyya I, Cohen DM. Salivary gland pathology in HIV patients. Diagn Histopathol. 2012;18:366–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franco-Paredes C, Rebolledo P, Folch E, Hernandez I, del Rio C. Diagnosis of diffuse CD8+ lymphocytosis syndrome in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Read. 2002;12:408–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beitler JJ, Vikram B, Silver CE, Rubin JS, Bello JA, Mitnick RJ, et al. Low-dose radiotherapy for multicystic benign lymphoepithelial lesions of the parotid gland in HIV positive patients: Long-term results. Head Neck. 1995;17:31–5. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880170107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus A, Moore CE. Sodium morrhuate sclerotherapy for treatment of benign lymphoepithelial cysts of parotid gland in an HIV patient. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:746–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000161349.53622.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michelow P, Dezube BJ, Pantanowitz L. Fine needle aspiration of salivary gland masses in HIV-infected patients. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:684–90. doi: 10.1002/dc.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]