Abstract

Background

Pain is a prevalent and distressing symptom in patients with cancer, having an enormous impact on functioning and quality of life. Fragmentation of care, inadequate pain communication, and reluctance towards pain medication contribute to difficulties in optimizing outcomes. Integration of patient self-management and professional care by means of healthcare technology provides new opportunities in the outpatient setting.

Methods/Design

This study protocol outlines a two-armed multicenter randomized controlled trial that compares a technology based multicomponent self-management support intervention with care as usual and includes an effect, economic and process evaluation. Patients will be recruited consecutively via the outpatient oncology clinics and inpatient oncology wards of one academic hospital and one regional hospital in the south of the Netherlands. Irrespective of the stage of disease, patients are eligible when they are diagnosed with cancer and have uncontrolled moderate to severe cancer (treatment) related pain defined as NRS ≥ 4 for more than two weeks. Randomization (1:1) will assign patients to either the intervention or control group; patients in the intervention group receive self-management support and patients in the control group receive care as usual. The intervention will be delivered by registered nurses specialized in pain and palliative care. Important components include monitoring of pain, adverse effects and medication as well as graphical feedback, education, and nurse support. Effect measurements for both groups will be carried out with questionnaires at baseline (T0), after 4 weeks (T1) and after 12 weeks (T2). Pain intensity and quality of life are the primary outcomes. Secondary outcomes include self-efficacy, knowledge, anxiety, depression and pain medication use. The final questionnaire contains also questions for the economic evaluation that includes both cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis. Data for the process evaluation will be gathered continuously over the study period and focus on recruitment, reach, dose delivered and dose received.

Discussion

The proposed study will provide insight into the effectiveness of the self-management support intervention delivered by nurses to outpatients with uncontrolled cancer pain. Study findings will be used to empower patients and health professionals to improve cancer pain control.

Trial registration

NCT02333968 December 29, 2014

Keywords: Cancer pain, Outpatients, Nursing, Self-management, eHealth, Study protocol, Randomized controlled trial

Background

Pain continues to be a prevalent and distressing symptom described by patients during curative, palliative and survivorship cancer care [1]. Each patient is unique and the process of controlling cancer pain evolves differently every time. At the inpatient or outpatient clinic, initial pain assessments and medication prescriptions are provided in consultation with a health professional. Once at home, patients and their caregivers face practical challenges and difficulties, because daily pain management requires more than simply following medication prescriptions [2]. Considering these challenges and difficulties, together with the barriers that have been identified in the outpatient setting [3–5], patients need to be supported in their cancer pain self-management [6].

Some arrangements are considered necessary for effective self-management. Patients require assistance in order to easily access information about pain and pain medication, about what is normal and about when and how to get help [7]. Patients also need to be able to recognize and monitor pain and adverse effects in order to get insight into their own situation and feedback about how they are doing [8]. Patients will be motivated when they are supported by their health professional to have confidence and to undertake strategies to manage better [9]. On that account, researchers point at multicomponent interventions that concentrate more intensively on self-efficacy [10]. Patients require different support in different situations when it comes to self-management [11]. Patients themselves will select the type of support needed in a given situation at a given point in time [12]. Being embedded in routine clinical practice, healthcare technology provides chances to integrate these different arrangements and contribute to patient self-management.

Providing patients with self-management support requires health professionals to accept a slightly different role and make a shift from clinical outcomes towards providing help with day-to-day problems [13]. By virtue of their expertise and focus on patients’ daily living, nurses are able to make substantial contributions to pain self-management [14]. Not being able to monitor pain has been identified as an important barrier to adequate pain management in the outpatient setting [15]. Ongoing review and management of symptoms can be difficult to achieve for health professionals when outpatient consultations take place occasionally whereas daily pain fluctuations are very common. Healthcare technology is promising in facilitating telemonitoring, enhancing symptom management and improving quality of life [16].

We previously developed a technology based multicomponent self-management support intervention consisting of an iPad application for patients that is connected to a web application for nurses; both applications are embedded in routine clinical practice. Important components include monitoring of pain, adverse effects and medication as well as graphical feedback, education, and nurse support. A small-scale evaluation confirmed feasibility of the intervention in everyday life. Even though patients and nurses had to get used to new tasks, responsibilities and technology, they were positive about the applications. Continuous monitoring in good and bad moments underscored clinical relevance and use in practice. Adjustments were made to overcome technical problems; suggestions for improvement gave input for the set-up of the present large-scale evaluation.

Methods

Design

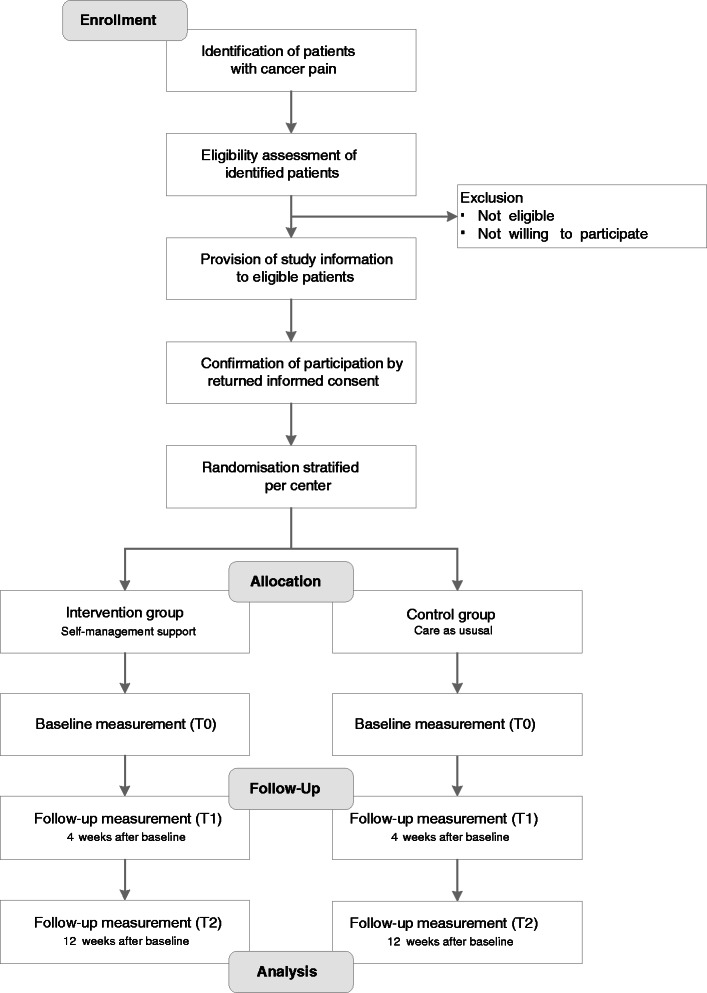

This study protocol outlines a two-armed multicenter randomized controlled trial that compares a self-management support intervention with care as usual and includes an effect, economic and process evaluation. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee Atrium-Orbis-Zuyd, the Netherlands (NL46552.096.13). Registration of the study protocol was performed on December 29, 2014 (NCT02333968). A flowchart of the study design is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study design

Eligibility

Irrespective of the stage of disease, patients are eligible when they are diagnosed with cancer and cope with uncontrolled moderate to severe cancer (treatment) related pain. Moderate to severe pain is defined as an NRS score ≥4. Pain should be present for more than two weeks and patients should live at home.

Patients will be excluded in case of an expected life prognosis <3 months, chronic non-cancer (treatment) related pain, known cognitive impairments, participation in studies that interfere with this study, insufficient reading skills and comprehension of the Dutch language, a reduced vision and/or non-accessibility via telephone.

Recruitment

Patients will be recruited consecutively via the outpatient oncology clinic and inpatient oncology wards of one academic hospital and one regional hospital in the south of the Netherlands. When patients are considered eligible by the treating physician and are interested in participation, they will receive a patient information letter and an informed consent form. In the information letter detailed information is given about the intervention and study procedures. The fact that patients in the intervention group receive an intervention alongside the current care for their pain is emphasized. Patients will be asked to read the information carefully and to discuss participation with their partner, family or friends. The contact details of the researcher are provided in the information letter and potential participants will be encouraged to contact the researcher or the independent physician in case of questions or doubts. Two weeks will be given to consider participation. Patients who decide to participate in the study are asked to return their informed consent. After informed consent, the treating physician and the general practitioner will be informed about the patient’s participation.

Randomization and blinding

Patients will be randomly allocated to the intervention or control group with an allocation ratio of 1:1. The randomization, stratified per center, is computer-generated and will be carried out by an independent research assistant; the allocation sequence is unknown to the treating physicians and nurses who recruit patients and to the researcher who includes patients. After informed consent, the independent research assistant will reveal the group allocation to the researcher who includes the patient. Blinding of patients, nurses and treating physicians to group allocation is not possible due to the nature of the intervention. Data will be analyzed after encryption, without recognition of original variables including name, center and group allocation. An independent research assistant will store the encryption key and reveal the original variables at the end of the study.

Intervention

Patients will receive the intervention alongside the pain treatment that is provided to them by their treating physician. The intervention will not interfere with, nor be a substitute for, their usual pain treatment as the treating physician remains responsible and decides on follow-up. The intervention has been designed in a co-creative process together with researchers, health professionals, patients and technical experts. This process resulted in an intervention that integrates patient self-management and professional care by means of healthcare technology and consists of an iPad application for patients and a web-application for nurses. Both applications are embedded in routine clinical practice.

Patient application

Patients register their pain, adverse effects, interference of pain with activity or sleep, and satisfaction with treatment by use of a pain diary twice-daily and optional extra pain intensity scores within the iPad application. Moreover, patients are requested to register intake of “around-the-clock” (ATC) and “as needed” (PRN) medication in a personalized medication day schedule. Accordingly, registered pain intensity scores and medication intake moments are depicted in a graph. Besides, patients receive education about causes of pain, treatment of pain, recognition of symptoms that require action, and methods that patients themselves can implement to control pain. Patients are able to communicate with the nurse via text message functionality within the application in case of questions.

Nurse application

Based on the web application, the nurse monitors and analyzes the patient’s situation once every workday, taking into account completed pain diaries, scheduled and actual medication intake and text messages. A decision support system within the application, which consists of an algorithm with questions, answers, and colored risk flags supports nurses in their monitoring tasks: red flags require immediate action, yellow flags ask to keep an eye, and green flags indicate everything is okay. In addition to sending text messages and consulting patients by phone, nurses have the opportunity to collaborate with the treating physician, pain specialist or the multidisciplinary palliative team when pain relief is inadequate.

In advance of the randomized controlled trial, nurses took part in a 2-h instruction meeting about the nurse application. These instructions are also summarized in an instruction manual.

Procedure

For each patient in the intervention group an account will be created in the nurse application, which will then be linked to the patient application. Accordingly, a medication overview will be obtained from the pharmacist. Pain medication from this overview will be entered into the nurse application and activated to be visible in the patient application. The nurse will process changes in pain medication during the study period alike.

At baseline, a home visit will be scheduled. The nurse carries out a pain anamnesis, checks pain medication and provides patients with information about pain and pain management. The researcher explains how to use the patient application; information that is summarized in an instruction manual as well. In case of technical troubles with using the application during the study period, patients will be advised to contact a helpdesk. After twelve weeks the researcher will schedule another home visit to conduct a semi-structured interview to explore experiences of the patient.

Care as usual

Outpatients with cancer pain enter the outpatient clinics involved in the study basically via three different routes: patients see their oncologist for follow-up and indicate having pain; patients are referred by their general practitioner with an increase in pain complaints; or patients contact the oncology department themselves. Patients are often treated by their oncologist with regard to cancer pain. When the oncologist needs help, the pain specialist is consulted. During an outpatient consultation the pain specialist performs a pain anamnesis; checks pain medication and changes prescriptions when needed. Afterwards patients are seen again at the outpatient clinic or contacted by phone for a follow-up consultation. The timing and frequency of follow-up consultations differ and also depend on the type of medication that has been prescribed; sometimes after four days, sometimes after a week and when stabilized after two or three weeks. When pain is adequately treated, the consultation is closed. When pain gets worse and is difficult to treat, the patient is admitted to the hospital. Patients do often not receive information materials about pain and pain treatment. Usually patients are neither asked to monitor their pain scores, nor to register their medication intake on paper.

Co-interventions

For ethical and practical reasons, patients in both the intervention and control group are not restricted in the use of other methods to control pain. Because co-interventions might bias results and conclusions though, it is important to register these interventions and take them into account in the analyses. Therefore, all patients will be asked to report informational and practical sources or tools that supported them in coping with or controlling pain.

Data collection and outcome measures

Patients will be asked to complete postal questionnaires at three time points; namely at baseline (T0), after four weeks (T1), and after twelve weeks (T2). Measurements are selected based on their psychometric properties (validity, reliability), clinical utility and appropriateness for the target setting and population. Patients in the intervention group will be interviewed after the intervention period as part of the process evaluation. A focus group interview will be held with the nurses.

Effect evaluation

Primary outcome measures

Primary outcomes include pain intensity and quality of life. Pain intensity will be measured with the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), an instrument frequently used to assess pain in patients with cancer both within the clinical and research setting [17, 18]. In addition to severity of pain over the past three days, the 14-item BPI asks for location of pain, pain medication and amount of pain relief in the past 24-h, and impact of pain on daily function over the past three days.

Quality of life will be measured with the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30 version 3). This instrument is cancer specific, multi-dimensional and appropriate for self-administration. Five functional scales, three symptom scales, a global health and quality of life scale as well as single items for other symptoms are covered. The EORTC-QLQ-C30 has shown acceptable levels of reliability and validity [19]. Table 1 includes outcome measures and time points for the effect evaluation.

Table 1.

Outcome measures and time points of the effect evaluation

| Outcome measures | Instrument or source | Time points | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | ||

| Primary outcome measures | ||||

| Pain intensity | BPI | x | x | x |

| Cancer related quality of life | EORTC-QLQ-C30 | x | x | x |

| Secondary outcome measures | ||||

| Self-efficacy | CPSS-DLV | x | x | x |

| Knowledge | PKQ-DLV | x | x | x |

| Anxiety and depression | HADS | x | x | x |

| Pain medication use | Medication overview | x | x | x |

| Additional measures | ||||

| Socio-demographic data | Questionnaire | x | ||

| Medical data | Medical record | x | ||

| Co-interventions | Questionnaire | x | ||

T0: Baseline - T1: 4 weeks - T2: 12 weeks

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes include self-efficacy, knowledge, anxiety, depression, and pain medication use. Self-efficacy will be measured with the Chronic Pain Self-efficacy Scale (CPSS-DLV) [20]. The Dutch language version of the CPSS has two subscales (pain and symptom management and physical functioning), each consisting of 10 items. Based on how secure they are to carry out a specific activity or to achieve a specific outcome, patients score these items on a 10–100 scale (10 representing very unsecure and 100 very secure). Reliability and validity have been demonstrated for different pain conditions.

Ferrell’s Pain Knowledge Questionnaire (PKQ-DLV) will be used to measure knowledge. The questionnaire includes eight items that will be transformed to a 0–100 scale (0 is the lowest knowledge score; 100 is the highest knowledge score). The PKQ-DLV has an acceptable reliability and validity [21].

Anxiety and depression will be measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). This self-report scale consists of a depression and anxiety subscale, each with 7 items. The HADS showed good performance to assess symptom severity, anxiety disorders and depression in somatic, psychiatric and primary care patients [22, 23].

Information about pain medication use will be derived from the medication overview of the pharmacist.

Additional measures

Relevant demographic and medical data will be collected at the first measurement and retrieved from the medical record. The final measurement will include a data sheet that inventories co-intervention use during the study period. These co-interventions include information about pain and pain treatment, advices on how to control pain, pain medication schemes, reminders to take medication, diaries to register pain scores or medication intake, contact with the physician or nurse about pain or other self-reported resources.

Process evaluation

Process evaluation components that will be assessed include recruitment, reach, dose delivered (completeness) and dose received (exposure and satisfaction) [24]. The intervention will be evaluated qualitatively by means of semi-structured interviews with patients in the intervention group directly after the intervention period and with a focus group interview with nurses after the study period. Quantitative data will be collected continuously from plans, logbooks, log files and checklists. Components, operationalization and methods of the process evaluation are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Components, operationalization and methods of the process evaluation

| Component and definition | Operationalization | Data collection method |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | ||

| Procedures used to approach patients, at the individual and organizational level | • Procedures applied within and outside hospitals to recruit patients | • Recruitment plan |

| • Reasons for non-participation | • Recruitment logbook | |

| Reach | ||

| Proportion of the intended population that participated in the intervention | • Characteristics of patients | • Socio-demographic questionnaire |

| • Number of patients that completed the intervention or dropped out | • Server log file | |

| • Reasons for withdrawal | • Enrolment logbook | |

| Dose delivered (completeness) | ||

| Extent to which the intervention is actually delivered to patients and nurses | • Implementation of the home visit as intended | • Checklist |

| • Interviews patients | ||

| • Functioning of the patient and nurse application as intended | • Interviews nurses | |

| • Server log file | ||

| • Helpdesk logbook | ||

| Dose received (exposure) | ||

| Extent to which patients and nurses received and used the intervention | • Opinion about the ability of patients to understand and implement the intervention | • Interviews patients |

| • Patients’ and nurses’ adherence towards the intervention | • Interviews nurses | |

| • Number of actions nurses applied in follow-up of monitored data | • Server log file | |

| Dose received (satisfaction) | ||

| Satisfaction of patients and nurses with the intervention | • Experienced benefits, burden, and supportiveness of the intervention by patients and nurses | • Interviews patients |

| • Interviews nurses | ||

| • Overall opinion of patients and nurses | ||

| • Facilitators and barriers in applying | ||

| • The intervention | ||

Economic evaluation

The economic evaluation will be performed from a societal perspective, which implies that all relevant medical and non-medical costs and effects are taken into account [25]. The economic evaluation will involve a combination of a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) and a cost-utility analysis (CUA). Compared to care as usual, the self-management support intervention is expected to result in cost effective care with improvements in pain intensity and quality adjusted life years (QALYs).

The CEA includes intervention costs, healthcare costs, patient and family costs, and costs outside the health care sector. To limit the burden for patients, cost data are preferably collected by means of retrospective questionnaires that should not exceed a recall time frame of six months [26]. Therefore, a questionnaire will be included in the final measurement, retrospectively asking for costs made during the study period of three months. Existing questionnaires are combined to identify all relevant costs.

Within the CUA outcomes will be measured by means of the EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L), a self-administered questionnaire that consists of a descriptive system and a visual analogue scale [27].

Sample size and power calculation

The power calculation is estimated by a two-tailed analysis, based on the assumption that alpha and beta equal 0.05 and 0.2 respectively. The mean pain intensity is expected to decrease 1.5 on a 0–10 point-scale in the intervention group compared to the contol group. To have adequate power to test the effect of the intervention on pain intensity, the sample size will equal 62.8 in both the intervention as well as control group. Taking into consideration 15 % of non-response, a total of 73 patients per group will be needed. In addition, during the study period 20 % of patients are expected to drop out because they are too ill or died (loss to follow-up). Therefore, 87 patients per group will be needed to have adequate power.

Planned analyses

Quantitative data will be analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. A directed content analysis method will be followed to analyze data qualitatively.

Analyses effect evaluation

Intention to treat analyses and per protocol analyses will be conducted. Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions will be generated for demographic, disease and pain related characteristics. Independent student t-tests and chi-square tests will be performed to determine comparability in baseline characteristics between patients randomized to the intervention and control group. To evaluate the effect of the intervention and changes over time, an analysis for longitudinal data will be conducted using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) or mixed regression models. The number of dropouts in this study, mainly by severe illness and death, will probably result in an unbalanced dataset. Mixed regression models offer an alternative for dealing with unbalanced data sets. Therefore, changes over time and differences between subgroups will be tested by using the Random Intercept Model.

Analyses process evaluation

Quantitative data will be analyzed by means of descriptive statistics. The information from semi-structured and focus group interviews as well as the notes of the nurses will be analyzed qualitatively. Data will be summarized, coded and organized into categories. These categories reflect the emerging themes for patients’ and health professionals’ experiences with the intervention.

Analyses economic evaluation

Valuation of costs will be based on the Dutch manual for cost analysis in health care research [28]. Differences in costs and effects will be presented in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and an incremental cost-utility ratio (ICUR). The ICER and ICUR represent the difference in mean costs of the intervention and control group in the numerator and the difference in mean effects of the intervention and control group in the denominator.

Discussion

As actual cancer pain management is practiced particularly at home and outpatients face difficulties in putting prescriptions into practice [2], supporting self-management appears to be a promising solution. Healthcare technology provides opportunities to follow-up patients beyond the walls of the outpatient clinic. The RCT involves the evaluation of a technology based multicomponent self-management support intervention that combines monitoring of pain, adverse effects and medication with graphical feedback, education, and nurse support. Compared to care as usual, self-management support is expected to result in better pain control and better quality of life.

The intervention is different from previous attempts in its multicomponent and interactive approach. Complex interventions having several interacting components require good theoretical understanding and the use of different outcome measures to evaluate underlying mechanisms [29]. Quantitative and qualitative data collection will be combined and different outcomes related to cancer pain and self-management will be measured. While clinical effectiveness is of primary concern, the information from the process and economic evaluation will provide important in-depth insights into the success of the intervention in order to better interpret results and improve future implementation [30, 31].

Recruitment of oncological patients in any study can be challenging. When the study involves symptom management, rather than disease treatment, recruitment even asks for more efforts [32]. Health professionals protect their patients because of high disease and symptom burden; patients most in need for these interventions often feel too ill or overwhelmed. Provision of information about the intervention and both advantages and disadvantages of study participation to health professionals and patients is believed to increase enrollment [33]. Departments of participating centers will be visited regularly and study information as well as number of inclusion updates will be disseminated repeatedly via commonly used communication channels. Moreover, shortly after they received the informed consent documents from their treating physician, patients will be called by the researcher in order to provide more information about the study and to answer questions. These contact moments with both health professionals as well as patients will reveal important information as regards the reasons for health professionals not to recruit and for patients not to participate; information that will be used in future contacts to increase enrollment. Others lessons learned from previous research have been taken into account in the preparation of this RCT: the content and frequency of questionnaires have been minimized, flexibility will be offered in scheduling home visits and a helpdesk will be available for technological support and assistance with filling out questionnaires [32–34].

Study outcomes will contribute to the understanding on interventions improving cancer pain in outpatients by means of self-management support. Evaluations will also provide important information as to whether a mixed population of cancer patients regarding age, socio-economic status and complexity of disease and medication, is accepting healthcare technology. The intervention could be base for other cancer related health problems or for pain problems in other chronic diseased populations.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (UM2011-5079). IDEE Maastricht University, the Netherlands and Sananet Care BV, the Netherlands were involved in intervention development.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in the development of the protocol. LH drafted the initial manuscript. All authors edited, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

LH is PhD student at the School for Public Health and Primary Care (CAPHRI), Department of Health Services Research, Maastricht University. AC is coordinator of the palliative care team at the Department of Patient and Care, Maastricht University Medical Center. SZ is assistant professor at the School for Public Health and Primary Care (CAPHRI), Department of Health Services Research, Maastricht University. MvK is professor of anesthesiology and pain management at the School for Mental Health and Neuroscience (MHeNS), Department of Anesthesiology, Maastricht University Medical Center. LdW is professor of technology in care at the School for Public Health and Primary Care (CAPHRI), Department of Health Services Research, Maastricht University.

Contributor Information

Laura MJ Hochstenbach, Email: l.hochstenbach@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Annemie M Courtens, Email: a.courtens@mumc.nl.

Sandra MG Zwakhalen, Email: s.zwakhalen@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Maarten van Kleef, Email: maarten.van.kleef@mumc.nl.

Luc P de Witte, Email: l.dewitte@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

References

- 1.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(9):1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schumacher KL, Koresawa S, West C, Hawkins C, Johnson C, Wais E, et al. Putting cancer pain management regimens into practice at home. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(5):369–382. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oldenmenger WH, Sillevis Smitt PA, van Dooren S, Stoter G, van der Rijt CC. A systematic review on barriers hindering adequate cancer pain management and interventions to reduce them: A critical appraisal. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(8):1370–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobsen R, Liubarskiene Z, Moldrup C, Christrup L, Sjogren P, Samsanaviciene J. Barriers to cancer pain management: A review of empirical research. Medicina (Kaunas) 2009;45(6):427–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luckett T, Davidson PM, Green A, Boyle F, Stubbs J, Lovell M. Assessment and management of adult cancer pain: A systematic review and synthesis of recent qualitative studies aimed at developing insights for managing barriers and optimizing facilitators within a comprehensive framework of patient care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(2):229–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Schulman-Green D, Schilling LS, Lorig K, et al. Self-management: Enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(1):50–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.20093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilde MH, Garvin S. A concept analysis of self-monitoring. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57(3):339–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kravitz RL, Tancredi DJ, Grennan T, Kalauokalani D, Street RL, Jr, Slee CK, et al. Cancer Health Empowerment for Living without Pain (Ca-HELP): effects of a tailored education and coaching intervention on pain and impairment. Pain. 2011;152(7):1572–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Houtum L, Rijken M, Heijmans M, Groenewegen P. Self-management support needs of patients with chronic illness: Do needs for support differ according to the course of illness? Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(3):626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(2):177–187. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):239–43. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallerand AH, Musto S, Polomano RC. Nursing’s role in cancer pain management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(4):250–262. doi: 10.1007/s11916-011-0203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schumacher KL, Clark VLP, West CM, Dodd MJ, Rabow MW, Miaskowski C. Pain medication management processes used by oncology outpatients and family caregivers part i: health systems contexts. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(5):770–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.12.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickinson R, Hall S, Sinclair JE, Bond C, Murchie P. Using technology to deliver cancer follow-up: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):311. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen MP. The validity and reliability of pain measures in adults with cancer. J Pain. 2003;4(1):2–21. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson KO, Dowds BN, Pelletz RE, Edwards WT, Peeters-Asdourian C. Development and initial validation of a scale to measure self-efficacy beliefs in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 1995;63(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00021-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Wit R, van Dam F, Abu-Saad HH, Loonstra S, Zandbelt L, van Buuren A, et al. Empirical comparison of commonly used measures to evaluate pain treatment in cancer patients with chronic pain. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(4):1280–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, Van Hemert AM. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):363–370. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saunders RP, Evans MH, Joshi P. Developing a process-evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: a how-to guide. Health Promot Pract. 2005;6(2):134–147. doi: 10.1177/1524839904273387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell LB, Gold MR, Siegel JE, Daniels N, Weinstein MC. The role of cost-effectiveness analysis in health and medicine. JAMA. 1996;276(14):1172–1177. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540140060028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Brink M, van den Hout WB, Stiggelbout AM, Putter H, van de Velde CJ, Kievit J. Self-reports of health-care utilization: diary or questionnaire? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(3):298–304. doi: 10.1017/S0266462305050397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The EuroQoL Group: EQ-5D-5L User Guide: Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-5L instrument; 2011 http://www.euroqol.org. Accessed 12 Jan 2015

- 28.Oostenbrink J, Bouwmans C, Koopmanschap M, Rutten F. Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek. Methoden en standaard kostprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. Erasmus MC: Instituut voor Medical Technology Assessment; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(5):587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linnan L, Steckler A. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oakley A, Strange V, Bonell C, Allen E, Stephenson J, Team RS. Process evaluation in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions. BMJ. 2006;332(7538):413–16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7538.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ransom S, Azzarello LM, McMillan SC. Methodological issues in the recruitment of cancer pain patients and their caregivers. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(3):190–198. doi: 10.1002/nur.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berger AM, Neumark DE, Chamberlain J. Enhancing recruitment and retention in randomized clinical trials of cancer symptom management. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(2):E17–E22. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.E17-E22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koller A, Miaskowski C, De Geest S, Opitz O, Spichiger E. Supporting self-management of pain in cancer patients: Methods and lessons learned from a randomized controlled pilot study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]