Abstract

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a bioactive lipid that provides cellular signals through plasma membrane G protein-coupled receptors. The S1P receptor signaling system has a fundamental and widespread function in licensing the exit and release of hematopoietically derived cells from various tissues into the circulation. Although the outlines of the mechanism have been established through genetic and pharmacologic perturbations, the temporal and spatial dynamics of the cellular events involved have been unclear. Recently, two-photon intravital imaging has been applied to living tissues to visualize the cellular movements and interactions that occur during egress processes. Here we discuss how some of these recent findings provide a clearer picture regarding S1P receptor signaling in modulating cell egress into the circulation.

Keywords: sphingosine-1-phosphate, sphingolipid, signaling, gradient, receptor, two-photon microscopy

1. Introduction

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a pleiotropic signaling molecule derived from the sphingolipid metabolic pathway [1, 2]. Perhaps surprisingly because of its lipophilic nature, S1P functions extracellularly to dynamically control key physiologic activities affecting essentially every organ system in the body [2]. This widespread control of physiology is made possible by several unique features of the signaling system.

S1P production is ubiquitous; the sphingolipid pathway exists in every mammalian cell, with S1P being its final sphingolipid product. Despite its synthesis in every cell, the distribution of its concentration levels is highly structured in the body [3, 4]. The highest S1P concentrations are found in the circulation, with levels reaching the micromolar range in the blood and the high nanomolar range in the lymph [5, 6]. The concentration of S1P in the interstitial spaces of tissues has not been directly measured, but it is believed to be in the low nanomolar range or below [4, 7, 8].

The high and low concentration zones of S1P are produced by a specific arrangement of cell types with specialized aspects of sphingolipid metabolism [3]. The majority of S1P production in the blood is due to red blood cells, which contain sphingosine kinase (the enzyme that produces S1P) but lack the S1P lyase and phosphatases (the enzymes that degrade S1P) [7, 9]. About a third of S1P in the blood and the bulk of S1P in the lymph, which lacks red blood cells, is produced by endothelial cells and exported by a specialized S1P plasma membrane transporter (Spns2) [10–12]. S1P lyase and phosphatases act to keep S1P levels generally low in the interstitium [6, 13, 14].

Extracellular S1P provides signals to cells via a family of five S1P G protein-coupled receptors (S1P1–5) [15]. In line with the broad impact of the signaling system, receptor expression is relatively high and ubiquitous amongst tissues [16]. Each of the receptors triggers distinctive signaling pathways; because multiple receptors are often found on the same cells, these pathways may work in concert [17] or act antagonistically toward S1P1 for control of cellular functions [18–23].

Although many functions have been described for S1P signaling, one that has been studied extensively is its role in trafficking of cells of the hematopoetic lineage [4, 6, 7, 24]. S1P signaling is now appreciated to play a central role in the egress of cells of the immune system out of tissues into the circulation, including from their sites of origin in bone marrow and thymus, as well as from secondary lymphoid tissues [4, 6, 25–30] This process was initially recognized by an understanding of the immunosuppressive actions of FTY720, a compound that when phosphorylated is a potent agonist for S1P1, 3, 4, and 5, acting on S1P1 to block egress of lymphocytes from lymphoid tissue into the circulation [31, 32]. Later it was shown in genetic experiments that S1P1 expression on lymphocytes, which is regulated developmentally, during homeostatic trafficking and under acute conditions, is essential for the egress step [27, 33–39]. Pharmacologic manipulation of S1P1 by FTY720 (and other receptor-active compounds) can block lymphocyte egress, although whether the relevant target is on lymphocytes or the lymphatic endothelium has been a matter of debate [25, 26, 35, 40, 41]. However, recent studies point to lymphocyte S1P1 as the site of action of FTY720 [39].

Removing sources of S1P near the sites of egress—blood [7], lymph [7], and vascular structures [10, 12, 36, 42]—blocks the exit of lymphocytes into the circulation. Collectively, these results suggest that lymphocytes utilize S1P1 in some fashion to identify the source of abundant S1P and navigate into it. FTY720 acts to rapidly induce downmodulation of S1P1 on lymphocytes, explaining its ability to block egress [4, 39, 43].

Recent advances in the ability to visualize dynamic cellular processes in vivo in real time have revolutionized areas of biology [44]. Key to the ability to “see deep” into living tissues and organs has been the development and application of two-photon (also called multiphoton) microscopy. The use of this technique to visualize the trafficking, positioning, and interaction of cells in the immune system, in particular, has yielded fundamental changes in our understanding of its inner workings [44]. Recently, two-photon microscopy has been applied to gain a deeper understanding of the S1P-directed signaling events involving cell movement and interactions. Here, we review some of these recent investigations examining the process of S1P-directed cell egress and the important details that have been uncovered, yielding new insights into the inner workings of S1P signaling in vivo.

2. Two-photon basics

The application of two-photon excitation to fluorescence microscopy has become a powerful tool for studying biological function deep in live tissues and offers some key advantages over conventional imaging techniques. In this section, for the purposes of this review, we will outline the basics of two-photon (also called multiphoton) microscopy, along with the basic advantages and pitfalls in using two-photon excitation in comparison to conventional single-photon excitation for intravital imaging. The technical features of these two methods are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the features of one-photon and two-photon microscopy

| One-Photon/Confocal Microscopy |

Two-Photon Microscopy |

Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum useful penetration depth | ~100 µm (tissue and wavelength dependent) | ~1000 µm (tissue and wavelength dependent) | [89, 90] |

| Fluorophore photobleaching | ++ | + | [90] |

| Photodamage | ++ | + | |

| Choice of fluorophores | +++ | + | [91, 92] |

| Choice of fluorescent proteins | +++ | + | [93] |

| Excitation wavelength flexibility | Discrete wavelengths, multiple lasers available | Theoretically continuous; in cases of one laser, one wavelength at a time | [90] |

| Live multicolor imaging | Yes | Yes, but more limited | [93] |

| Simultaneous visualization of extracellular matrix | Limited use of reflected light for thin specimens (10 µm) | Yes, second and third harmonic generation | [47] |

| Maximum practical lateral resolution for live imaging | 250 nm | ~300 nm | [89, 90] |

| Maximum practical axial resolution for live imaging | 600–700 nm | 1 µm |

The one-photon fluorescence process involves exciting a fluorophore from the electronic ground state to an excited state by a single photon. This excitation is followed by vibrational relaxation and finally a return to the ground state, with the emission of a photon with less energy than the original and thus a longer wavelength. In fluorescence, this process takes place in the nanosecond time scale and typically requires photons in the ultraviolet to red spectral range. However, the same excitation process can be generated by the near-simultaneous absorption of two or more less energetic photons (typically in the near-infrared spectral range) using short pulses (femtosecond to picosecond scale) of laser illumination. In the two-photon excitation process, a fluorophore is excited by the near-simultaneous absorption of two photons. Each one of the two photons carries at least half of the energy required to excite a fluorophore and temporarily brings a valence electron to an intermediate state. Should a second photon with the same amount of energy excite the fluorophore during this transition, the molecule brings its electron to the excited state, resulting in vibrational relaxation and photon emission in a nanosecond scale (fluorescence). The two-photon excitation process is restricted to an extremely small volume (~1 femtoliter) and thus minimizes out-of-focus excitation and excessive bleaching of the fluorophore in the out-of-focus plane. Use of infrared wavelengths for excitation results in reduced light scattering and increased penetration, yielding highresolution images deep in tissues.

The use of two-photon imaging also offers the advantage of obtaining crucial information residing in the living specimen, without fluorescent labeling of any molecule, but merely with the use of nonlinear optical phenomena termed second and third harmonics [45, 46]. Second harmonic generation (also called frequency doubling) is a process in which photons interacting with a nonlinear material are effectively “combined” to form new photons with twice the energy, and therefore twice the frequency and half the wavelength, of the initial photons. The powerful near-infrared lasers used in two-photon imaging result in second harmonic emission in the visible range. The method has gained wide application in intravital imaging, as it enables analysis of connective tissue and extracellular environment at high resolution [46]. Thus the combination of harmonic generation with fluorescent imaging provides invaluable tools to study various aspects of in situ physiology, such as cell motility, cell-cell interactions, tissue architecture, microenvironments, and cell migration or metastasis [45–47]. An example of two-photon imaging indentifying CX3CR1-EGFP–positive cell [48] movement within the collagen matrix (identified by second haromonic generation) within the ear dermis of a living mouse is shown (Video 1; supplemental multimedia file).

Although visualizing biologic processes in vivo, i.e. within the living animal’s body, is ussally the ultimate goal, ex vivo experimental designs using two-photon microscopy have also been succesfully applied. While the ex vivo approach can provide crucial information, it has to be taken into account that the organ or tissue to be imaged is disconnected from the main circulatory systems and other factors that might contribute to the biological output. Excellent descriptions on the technical details of this approach can be found elsewhere [49–51].

3. Lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes

T and B lymphocytes enter lymph nodes from the blood through high endothelial venules. Without antigenic stimulus, the lymphocytes egress to enter efferent lymphatics and return to the circulation within a characteristic time period [28, 52, 53]. Activated lymphocytes remain for longer in the lymph node before egress and eventually travel through efferent lymphatics to their effector sites. Lymphocyte egress from the lymph nodes into lymphatics depends on intrinsic expression of lymphocyte S1P1 [54, 55], lymph replete with S1P [7, 10, 56] and S1P production by endothelial cells [56]. Intravital two-photon imaging studies have been pivotal in defining the S1P-dependent steps in the egress of lymphocytes from lymph nodes.

The first imaging study on this topic applied real-time two-photon microscopy to intact, explanted lymph nodes to visualize motility and transendothelial migration of individual T cells into lymphatic sinuses [57]. While facilitating experimental control, the explant system has the disadvantage of severing the lymphatic and blood vessel connections. Nevertheless, T cells were observed exiting from the medullary cords into the medullary lymphatic sinuses. Application of SEW2871, an S1P1 agonist, caused “log-jamming” along the borders of the medullary sinuses, apparently because the lymphocytes were not able to cross into the lymphatic sinuses. The inhibitory effect of SEW2871 on lymphocyte flux was reversed by removal of the agonist or by the addition of the antagonist. S1P1 antagonist alone, however, did not alter trans-endothelial migration of T cells in the explant system. Thus, egress of T cells into the lymphatic sinus visualized in real time showed that pharmacologic manipulation of S1P1 activation inhibited lymphocyte egress from the lymph node through the lymphatic endothelium [57].

Two-photon intravital imaging studies by Cyster and coworkers [52] on intact lymph nodes in living mice provided a detailed itinerary of the S1P-dependent steps in the egress of T cells. LYVE-1 antibody was used to label sinuses in the cortical region as well as sinuses and macrophages in the medullary region. Intravital microscopy revealed that when T cells were approaching the cortical sinus, they extended processes into the sinus lumen. Subsequently, the cells retracted and reoriented themselves either toward or away from the sinus wall, suggesting that T cells were in the “decision-making” phase when probing the sinus wall. S1P1-deficient T cells had no defect in migrating over and probing the surface of cortical sinuses compared with wild-type cells. However, the S1P1-deficient T cells were defective in entering into the cortical sinuses, whereas wild-type cells were capable of both entering and exiting these structures, meaning that T cell entry into LYVE-1+ cortical sinuses is dependent on the S1P1 receptor. According to the proposed model, the T cell will make a “decision” while probing the sinus wall for S1P and sampling the lymph node interstitium for the retention signal CXCL21. Based on the strength of the respective signals that the T cell receives through the S1P1 receptor from S1P or through CCR7 (the receptor for CXCL21; Fig. 1), it will either move across the sinus endothelium in an S1P1-dependent process or, if the signaling through CCR7 predominates, remain within the lymph node. When T cells enter the sinus after detaching from the endothelium, they are captured in regions of flow, pass to medullary sinus, and finally are flushed into the subcapsular space and efferent lymph [52].

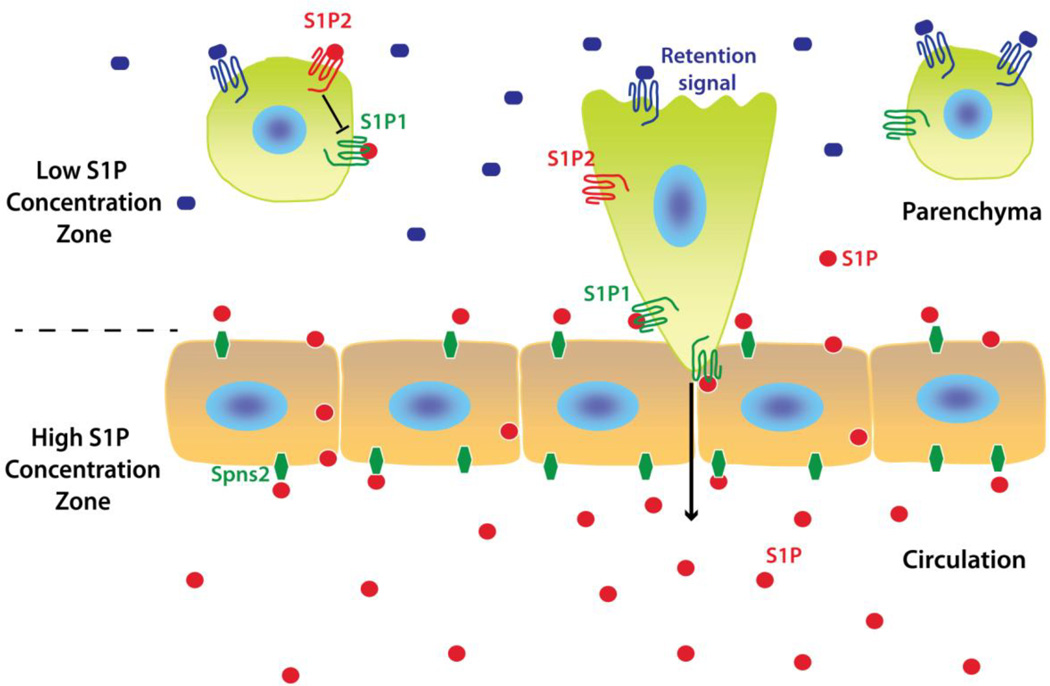

Fig. 1. Generalized model of S1P1-directed cell egress/release from tissue into circulation.

Circulating S1P levels are high in the blood and lymph, but low in the parenchyma of most tissues forming high and low S1P concentration zones. The two major contributors of S1P levels are erythrocytes in the blood and endothelial cells via a transporter, Spns2. Lymphocytes in lymph nodes appear to sense S1P via S1P1 by probing at the cortical sinus endothelium, which triggers their transendothelial migration by a process not yet understood. In this model, it is presumed that all cell types listed (Table 2) sense S1P in a similar fashion. MZ B cells egress into the MZ but return to the follicles, whereas splenic follicular B cells egress into the MZ but then exit the spleen through the venous circulation. In the case of megakaryocytes, S1P1 signaling directs proplatelet processes to extend into the sinusoids, where blood S1P triggers fission for platelet release into the circulation. The balance between S1P1/S1P-driven egress versus cell type-specific retention signals within tissues regulates the processes (Table 2). In certain cell types, such as osteoclasts, S1P2 has been shown to promote retention through antagonism of S1P1-mediated egress.

Kehrl and colleagues investigated the spatiotemporal modulation of B cell trafficking directed by S1P signaling in lymph nodes [58, 59]. The group examined the location of the lymphatics in relation to the lymph node B cell follicles, so as to determine whether they might support B cell exit [59]. Combining conventional immunohistochemistry and intravital two-photon laser scanning microscopy on intact lymph nodes, the investigators monitored B cell behavior near efferent cortical lymphatic channels. Treatment with FTY720 emptied B cells from the cortical sinuses adjacent to lymph node follicles, as had been observed with T cells. This change in cell distribution was attributed to a block in lymphocyte migration from the B cell follicle into the adjacent lymphatic sinusoids. Immunostaining with antibody against S1P1 showed that B cells express low surface levels of S1P1 near high endothelial venules, where they enter the lymph nodes from blood, re-express S1P1 on their surface in the follicle, and then revert to low levels of plasma membrane S1P1 in the cortical sinuses. This change in expression is consistent with a downmodulation of S1P1 in the high S1P environments of the blood and lymph, and surface upmodulation in the low S1P environment of the lymph node parenchyma as they reacquire responsiveness to S1P. Two-photon imaging revealed B cells engaging the endothelium, probing with membrane projections at the site of passage, and moving through a channel-like opening to enter the lumen of the lymphatic sinus, a process similar to that envisioned for T cells. In addition, B cells from S1P3 knockout mice and from Gn α i2 knockout mice (which are defective in S1P-mediated chemotaxis) adoptively transferred into recipient mice and imaged in vivo were found to travel through lymph nodes and to transit to the lymphatics, demonstrating that S1P-triggered chemotaxis, which is dominated by S1P3, does not substantially contribute to B lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes [59].

As with previous studies investigating T cell egress [52, 53], lymph node cortical lymphatic sinuses were shown to serve as a major egress site for B cells. As with T cells, it appears that the major function of S1P1 signaling on B cells is to sense S1P directly at sites of egress and facilitate their movement across the lymphatic endothelium. The model of B cell egress from the lymph node posits that gradual unresponsiveness to the follicular B cell chemokine CXCL13 enables the cell to move to the edge of the follicle by CXCR5 signaling, near the cortical sinus, where it can engage the lymphatic endothelium and traverse into the lymphatic sinus in an S1P1/S1P-dependent fashion [58, 59].

4. Marginal zone B cell shuttling and follicular B cell egress from spleen

The microenvironment of the marginal zone (MZ) of the spleen is unique in the context of constantly exposing the resident immune cells to open blood circulation and bloodborne antigens [60, 61]. The MZ demarcates the border between the white pulp, containing lymphoid follicles, and the red pulp, engorged with red blood cells. Blood flows from the central arteriole into the marginal sinus and MZ, percolating into the red pulp, before entering the venous compartment [61]. The MZ sinus is bordered on the follicular side by a cellular barrier composed of MAdCAM-1+ endothelial cells and metallophilic macrophages. MZ B cells are a specialized subset of B cells whose primary role is mounting antibody responses against pathogens derived from the circulation. Their presence is restricted to the spleen and they do not circulate due to intrinsic expression of high levels of integrins [62]. MZ B cells express high levels of S1P1 which, when deleted, cause relocation of the MZ B cells into the follicles [63]. Furthermore, FTY720 alters their location into the follicle. S1P3 has also been shown to contribute to their proper positioning through effects on the MAdCAM-1+ endothelial cells [64]. Taken together, these findings point to a pivotal role for S1P signaling in the intrasplenic migratory behavior of MZ B cells.

Arnon et al. were the first to develop methods to visualize the movement of B cells within the MZ and within the follicles in live mouse spleen by two-photon laser scanning microscopy [65]. They observed MZ B cells to be migratory in both the MZ and the follicles, but in the MZ their sharper turning angles and deviation from linear paths were consistent with confinement. The MZ B cells had a probing, dendritic cell-like morphology and had long trailing processes. MZ B cells constantly shuttled between the MZ and the follicles at a rate of exchange of 20% of the population per hour. Visualization of MZ B cells by two-photon microscopy after disruption of S1P1 function with FTY720 showed that MZ B cells moved out of the MZ and into the follicles within 30 minutes [65].

Follicular B cells also migrated into the MZ in an S1P1-dependent manner. However, because of lower integrin adhesive activity than MZ B cells, follicular B cells were moved passively by blood flow into the red pulp and then entered the blood circulation. These results defined an egress route for follicular B cells from the spleen through the MZ [65].

This work is consistent with a model of MZ B cells shuttling into the MZ and back to the follicles driven by cycles of S1P1-mediated entry to the MZ (with high S1P levels derived from the circulation), ligand-induced receptor downmodulation, and then CXCL13 (the ligand for CXCR5; Fig. 1)-dependent movement back to the follicle. The cycle is believed to mediate the MZ B cell delivery of opsonized antigens from the circulation to follicular dendritic cells. A part of this itinerary—the leg from the follicle through the MZ—has also been revealed as the pathway leading to the egress of follicular B cells from the spleen back into the circulation [65].

5. Platelet release from bone marrow

Blood platelets are small anucleated cell fragments that arise from megakaryocytes, which are large cells of the bone marrow containing a polyploid nucleus [66]. Platelet production requires the differentiation of megakaryocytes from hematopoietic precursors and their migration, positioning, and retention by CXCL12 and other factors at the endothelial sinusoidal surface. After arriving at the endothelial sinusoidal surface, megakaryocyte extensions called proplatelets then migrate through the bone marrow sinusoidal endothelial cells and into the intravascular space of the sinusoids. The proplatelets contain platelet precursors separated by thin cytoplasmic bridges arranged like beads on a string. Ultimately, the platelets are shed from these intravascular extensions; however, the mechanism was not known.

Using two-photon intravital microscopy and conditional mouse models, Massberg and coworkers [67] have shown that S1P1 has a key role in the final steps of platelet release into the blood. The sharp concentration gradient of S1P that marks the transition between blood and the interstitium in the bone marrow seems to be a key factor in directing the megakaryocyte proplatelet extensions into the vascular sinusoids. S1P1, triggered by the high S1P levels in the circulation, also mediates the physical release into the circulation of the mature platelets from the proplatelet extensions by activating the Gi/Rac GTPase signaling pathway. Correspondingly, mice lacking the S1P receptor S1P1 develop severe thrombocytopenia caused by both formation of aberrant extravascular proplatelets and defective intravascular proplatelet shedding. In contrast, activation of S1P1 signaling by FTY720 and SEW2871 leads to the prompt release of new platelets into the circulating blood. Although S1P4 has been reported to play a role in megakaryocyte differentiation [68], according to the findings of Zhang and coworkers it appears not to have a role in platelet release under normal hematopoietic conditions [67].

Collectively, their study [67] showed that S1P serves as a critical directional cue guiding the elongation of megakaryocytic proplatelet extensions from the interstitium into bone marrow sinusoids and for the subsequent release of platelets into the blood circulation through S1P1. It does not appear to function to mediate megakaryocyte chemotaxis or positioning at the perivascular interface, a role provided by CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 (Fig. 1) [66]. The study has significant therapeutic implications for patients with thrombocytopenia.

6. Osteoclast precursor egress into blood

Osteoclasts are large multinucleated cells originating from the monocyte lineage. Their differentiation from precursors requires macrophage colony-stimulating factor and receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANKL) [69]. They are found in pits in the bone surfaces, called resorption bays, and play a key role in bone remodeling, as these are the cells capable of degrading calcified bone matrix. Their increased absorption on the bone surface and potential malfunction exert effects on bone remodeling, a process which is of importance for the pathogenesis of both osteoporosis and osteoarthritis. Osteoclast precursors are found in the blood and bone marrow; however, the regulation of their trafficking from blood to bone surfaces was not understood.

Ishii and coworkers [70] created osteoclast/monocyte-specific S1P1 knockout (S1P1flox/flox × Cd11b-Cre) mice and employed genetically encoded GFP to label osteoclast precursors [71]. Intravital two-photon imaging was then performed through the mouse parietal bone tissue. They found that osteoclast precursors were generally present in bone marrow stromal locations or at the bone surface but were not readily detectable in the blood sinusoidal spaces at a steady state. A subset of the labeled cells became motile shortly after the intravenous application of the S1P1 agonist SEW2871. The attachment of S1P1-deficient osteoclasts was enhanced on the bone surface compared with control. The study indicates that S1P, as a bloodborne egress-inducing molecule, controls the migratory behavior of osteoclast precursors, presumably as they move from the bone marrow parenchyma through the endothelium lining the blood sinusoids. Subsequently [18] the authors studied the role of S1P2, which was known to activate the Rho pathway and inhibit the S1P1-activated Rac pathway, and showed that it mediates chemorepulsion to S1P. They provided evidence that S1P2 works counter to the blood egress function of S1P1, and suggested that S1P2, along with other bone marrow attraction molecules (such as CXCL12) (Fig. 1 and Table 2), should facilitate osteoclast precursor entry into the bone marrow parenchyma. Once present in the bone marrow, the balance of egress signaling through S1P1 retentive and S1P chemorepellent signaling dictates egress of precursors into the blood sinusoids rather than bone marrow retention and eventual differentiation into osteoclasts.

Table 2.

Signals directing S1P dependent cell egress/release

| Cell type | Retention/Positioning signal | S1P Signaling Zone | Egress/Release signal | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lymph node B cells T cells |

CXCR5 / CXCL13 CCR7 / CXCL21 |

LN cortical sinus | S1P1 / S1P | [58, 59] |

|

Spleen MZ B cells Follicular B cells |

CXCR5 / CXCL13 | Spleen marginal zone | S1P1 / S1P | [65] |

| Megakaryocytes | CXCR4 / CXCL12 | Bone marrow sinusoid | S1P1 / S1P | [67] |

| Osteoclasts | S1P2 / S1P CXCR4 / CXCL12 |

Bone marrow sinusoid | S1P1 / S1P | [70] |

7. Perspective: future directions

Intravital imaging has provided new details into the processes mediated by S1P signaling in vivo. In the examples described in this review, some common features emerge (Fig. 1). In each of the cases, a zone of low S1P concentration in the tissue interstitium is demarcated from a high S1P concentration zone by an endothelial barrier layer. The S1P concentrations in these zones may differ by orders of magnitude [4]. S1P1 signaling in these low S1P zones may be minimal, although this has not yet been directly ascertained. Using the best-characterized example of cellular egress, that of lymphocytes exiting from lymph nodes, chemotaxis (movement along a S1P gradient) within the lymph node parenchyma to the lymphatics endothelium is not believed to play an important role for lymphocyte exit [58, 59]. Instead, intravital imaging suggests that the critical S1P1 signaling event to stimulate the transmigration step takes place directly at the endothelial barrier after probing (presumably to enable S1P detection) by cellular processes of the lymphocyte. For platelet release, S1P1 molecules on proplatelet protrusions sense S1P in blood within the lumen of the sinusoids. These results are all consistent with the idea that S1P1 stimulation at the endothelial barrier provides the signal for the direct endothelial transmigration of cells or, in the case of megakaryocytes, of proplatelet extensions into the sinusoids. Another common feature in each of these examples is the presence of signals that compete with the S1P1-directed egress by retaining or positioning the cells in the parenchymal compartment (Fig. 1). For osteoclast precursors, several pathways -including one through S1P2 signaling-, antagonize S1P1-mediated egress [72] have been clarified. These multiple signals afford a high level of control of osteoclastogenesis that is necessary to balance bone formation and bone remodeling. In fact, recently it has been shown that vitamin D analogues, which are used therapeutically for osteoporosis, modify the S1P signaling process by decreasing S1P2 expression on osteoclast precursors and thereby increasing their egress into the circulation [73]. Collectively these results show the power of intravital imaging in unraveling the complex interactions regulating cell behavior.

It will be of interest to examine the details of other S1P receptor-mediated processes that involve migration and positioning including those used by thymocytes [27, 37], natural killer T cells [33], natural killer cells [74, 75], dendritic cells [76], granulocytes [13], mast cells [77, 78]and hematopoietic stem cells [79] by intravital microscopy to determine if similar principles apply. Less well-understood is where and how interstitial S1P concentration zones direct receptor-mediated processes. In a well-characterized example, evidence suggests the existence of an S1P concentration zones within the follicles, with higher concentrations around the perimeter and lower concentrations toward the center [8]. The S1P concentration differential is believed to confine B cells to the germinal center by the antagonist activity of S1P2 toward Gi-coupled migratory receptors [8, 80]. According to the model, when B cells move toward the perimeter of the germinal center, S1P2 senses the higher levels of S1P and becomes activated. S1P2 then transduces signals to inhibit migration through Rho activation, and eventually prompts germinal center B cells to “turn back,” resulting in their confinement. Moreover, S1P2 inhibits Akt activation, which ensures that germinal center growth will be inhibited, thus keeping it under control.

Beyond the many other opportunities to visualize migratory processes directed by S1P, it should be possible to link the actual cellular signaling events with the movements of the cells. A step in this direction was made by two-photon intravital imaging of the tissues of a knock-in mouse carrying a fluorescent S1P1-GFP fusion gene under the control of the endogenous locus to study the dynamics of the receptor in response to agonist stimulation in real time [81]. The model has been used to show receptor internalization in real time both intravitally but also in explants after the administration of newly synthesized S1P analogues. Construction of new mouse models where S1P signaling events can be traced, and even detected, in real time will provide the ability to determine where and when signaling occurs during cell movement and other S1P-dependent processes. Of particular significance would be a means to directly visualize the S1P concentration zones in vivo, a feat that has been thus far unattainable because of the physicochemical characteristics of S1P. However, the recent demonstration of imaging the in vivo gradient of the highly lipophilic molecule retinoic acid in zebrafish embryos [82] using genetically encoded fluorescence resonance energy transfer probes suggests possible approaches that may be applied to mouse models. In addition to that, generation of red-shifted fluorescent proteins [83], along with fluorescent proteins with convertible excitation/emission spectra that can be used to monitor cell migration and cell-cell interactions [84], has significantly increased the options available in the toolkit. Overall, the technology is rapidly evolving with the application of label-free imaging techniques such as Raman intravital microscopy/spectroscopy [85] and the potential ability to determine detailed spatial-temporal dynamics of signaling events by fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy/fluorescence resonance energy transfer [86–88].

Engagement of these tools will expand capabilities to dig even deeper into the varied cellular S1P signaling events in normal physiology to answer critical questions in the field such as the identification of the mechanisms of cellular import and export of S1P, distinguishing autocrine versus paracrine S1P signaling, as well as the role of S1P signaling in real-time on intracellular events such as vesicular transport, exocytosis and autophagy. Ultimately, this progress will lead to a detailed understanding of how S1P signaling participates in disease processes including atherosclerosis, autoimmunity, inflammation and cancer.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

S1P signals through S1P1 to stimulate cell egress into the circulation.

Two-photon intravital microscopy visualizes dynamic processes in vivo in real time.

Two-photon intravital microscopy has visualized S1P1-directed cellular egress.

S1P1-dependent egress processes for different cell types share common features.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Abbreviations

- S1P

sphingosine-1-phosphate

- S1P1–5

S1P G protein-coupled receptors 1–5

- LYVE-1

lymphatic vascular endothelial gene-1

- MZ

marginal zone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Christina C. Giannouli, Email: christina.giannouli@nih.gov.

Panagiotis Chandris, Email: Panagiotis.Chandris@nih.gov.

Richard L. Proia, Email: proia@nih.gov.

References

- 1.Spiegel S, Milstien S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: an enigmatic signalling lipid. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:397–407. doi: 10.1038/nrm1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fyrst H, Saba JD. An update on sphingosine-1-phosphate and other sphingolipid mediators. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:489–497. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olivera A, Allende ML, Proia RL. Shaping the landscape: metabolic regulation of S1P gradients. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cyster JG, Schwab SR. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:69–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizugishi K, Yamashita T, Olivera A, Miller GF, Spiegel S, Proia RL. Essential role for sphingosine kinases in neural and vascular development. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:11113–11121. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.11113-11121.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwab SR, Pereira JP, Matloubian M, Xu Y, Huang Y, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte sequestration through S1P lyase inhibition and disruption of S1P gradients. Science. 2005;309:1735–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1113640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappu R, Schwab SR, Cornelissen I, Pereira JP, Regard JB, Xu Y, Camerer E, Zheng YW, Huang Y, Cyster JG, Coughlin SR. Promotion of lymphocyte egress into blood and lymph by distinct sources of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Science. 2007;316:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.1139221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green JA, Suzuki K, Cho B, Willison LD, Palmer D, Allen CD, Schmidt TH, Xu Y, Proia RL, Coughlin SR, Cyster JG. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor S1P(2) maintains the homeostasis of germinal center B cells and promotes niche confinement. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:672–680. doi: 10.1038/ni.2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito K, Anada Y, Tani M, Ikeda M, Sano T, Kihara A, Igarashi Y. Lack of sphingosine 1-phosphate-degrading enzymes in erythrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagahashi M, Kim EY, Yamada A, Ramachandran S, Allegood JC, Hait NC, Maceyka M, Milstien S, Takabe K, Spiegel S. Spns2, a transporter of phosphorylated sphingoid bases, regulates their blood and lymph levels, and the lymphatic network. FASEB J. 2013;27:1001–1011. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-219618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nijnik A, Clare S, Hale C, Chen J, Raisen C, Mottram L, Lucas M, Estabel J, Ryder E, Adissu H, Adams NC, Ramirez-Solis R, White JK, Steel KP, Dougan G, Hancock RE. The role of sphingosine-1-phosphate transporter Spns2 in immune system function. J Immunol. 2012;189:102–111. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuhara S, Simmons S, Kawamura S, Inoue A, Orba Y, Tokudome T, Sunden Y, Arai Y, Moriwaki K, Ishida J, Uemura A, Kiyonari H, Abe T, Fukamizu A, Hirashima M, Sawa H, Aoki J, Ishii M, Mochizuki N. The sphingosine-1-phosphate transporter Spns2 expressed on endothelial cells regulates lymphocyte trafficking in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1416–1426. doi: 10.1172/JCI60746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allende ML, Bektas M, Lee BG, Bonifacino E, Kang J, Tuymetova G, Chen W, Saba JD, Proia RL. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase deficiency produces a pro-inflammatory response while impairing neutrophil trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7348–7358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.171819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bektas M, Allende ML, Lee BG, Chen W, Amar MJ, Remaley AT, Saba JD, Proia RL. Sphingosine 1-phosphate lyase deficiency disrupts lipid homeostasis in liver. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10880–10889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaho VA, Hla T. Regulation of mammalian physiology, development, and disease by the sphingosine 1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid receptors. Chem Rev. 2011;111:6299–6320. doi: 10.1021/cr200273u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regard JB, Sato IT, Coughlin SR. Anatomical profiling of G protein-coupled receptor expression. Cell. 2008;135:561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kono M, Mi Y, Liu Y, Sasaki T, Allende ML, Wu YP, Yamashita T, Proia RL. The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 function coordinately during embryonic angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29367–29373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishii M, Kikuta J, Shimazu Y, Meier-Schellersheim M, Germain RN. Chemorepulsion by blood S1P regulates osteoclast precursor mobilization and bone remodeling in vivo. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2793–2798. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okamoto H, Takuwa N, Yokomizo T, Sugimoto N, Sakurada S, Shigematsu H, Takuwa Y. Inhibitory regulation of Rac activation, membrane ruffling, and cell migration by the G protein-coupled sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor EDG5 but not EDG1 or EDG3. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9247–9261. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9247-9261.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obinata H, Hla T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate in coagulation and inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34:73–91. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0287-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arikawa K, Takuwa N, Yamaguchi H, Sugimoto N, Kitayama J, Nagawa H, Takehara K, Takuwa Y. Ligand-dependent inhibition of B16 melanoma cell migration and invasion via endogenous S1P2 G protein-coupled receptor. Requirement of inhibition of cellular RAC activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32841–32851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto H, Takuwa N, Yatomi Y, Gonda K, Shigematsu H, Takuwa Y. EDG3 is a functional receptor specific for sphingosine 1-phosphate and sphingosylphosphorylcholine with signaling characteristics distinct from EDG1 and AGR16. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:203–208. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ancellin N, Hla T. Differential pharmacological properties and signal transduction of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors EDG-1, EDG-3, and EDG-5. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18997–19002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kabashima K, Haynes NM, Xu Y, Nutt SL, Allende ML, Proia RL, Cyster JG. Plasma cell S1P1 expression determines secondary lymphoid organ retention versus bone marrow tropism. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2683–2690. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivera J, Proia RL, Olivera A. The alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors in immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:753–763. doi: 10.1038/nri2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosen H, Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Sanna MG, Brown S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:743–768. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.072407.103733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allende ML, Dreier JL, Mandala S, Proia RL. Expression of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor, S1P1, on T-cells controls thymic emigration. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15396–15401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westermann J, Puskas Z, Pabst R. Blood transit and recirculation kinetics of lymphocyte subsets in normal rats. Scand J Immunol. 1988;28:203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1988.tb02432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen H, Alfonso C, Surh CD, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Rapid induction of medullary thymocyte phenotypic maturation and egress inhibition by nanomolar sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10907–10912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832725100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yanai N, Matsui N, Furusawa T, Okubo T, Obinata M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid trigger invasion of primitive hematopoietic cells into stromal cell layers. Blood. 2000;96:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, Quackenbush E, Xie J, Milligan J, Thornton R, Shei GJ, Card D, Keohane C, Rosenbach M, Hale J, Lynch CL, Rupprecht K, Parsons W, Rosen H. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science. 2002;296:346–349. doi: 10.1126/science.1070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brinkmann V, Davis MD, Heise CE, Albert R, Cottens S, Hof R, Bruns C, Prieschl E, Baumruker T, Hiestand P, Foster CA, Zollinger M, Lynch KR. The immune modulator FTY720 targets sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21453–21457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allende ML, Zhou D, Kalkofen DN, Benhamed S, Tuymetova G, Borowski C, Bendelac A, Proia RL. S1P1 receptor expression regulates emergence of NKT cells in peripheral tissues. FASEB J. 2008;22:307–315. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9087com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allende ML, Tuymetova G, Lee BG, Bonifacino E, Wu YP, Proia RL. S1P1 receptor directs the release of immature B cells from bone marrow into blood. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1113–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwab SR, Cyster JG. Finding a way out: lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1295–1301. doi: 10.1038/ni1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pham TH, Okada T, Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cyster JG. S1P1 receptor signaling overrides retention mediated by G alpha i-coupled receptors to promote T cell egress. Immunity. 2008;28:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Brinkmann V, Allende ML, Proia RL, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pereira JP, Xu Y, Cyster JG. A role for S1P and S1P1 in immature-B cell egress from mouse bone marrow. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thangada S, Khanna KM, Blaho VA, Oo ML, Im DS, Guo C, Lefrancois L, Hla T. Cell-surface residence of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 on lymphocytes determines lymphocyte egress kinetics. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1475–1483. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brinkmann V, Cyster JG, Hla T. FTY720: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 in the control of lymphocyte egress and endothelial barrier function. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1019–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhi L, Kim P, Thompson BD, Pitsillides C, Bankovich AJ, Yun SH, Lin CP, Cyster JG, Wu MX. FTY720 blocks egress of T cells in part by abrogation of their adhesion on the lymph node sinus. J Immunol. 2011;187:2244–2251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zachariah MA, Cyster JG. Thymic egress: S1P of 1000. F1000 Biol Rep. 2009;1:60. doi: 10.3410/B1-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graler MH, Goetzl EJ. The immunosuppressant FTY720 down-regulates sphingosine 1-phosphate G-protein-coupled receptors. FASEB J. 2004;18:551–553. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0910fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Germain RN, Robey EA, Cahalan MD. A decade of imaging cellular motility and interaction dynamics in the immune system. Science. 2012;336:1676–1681. doi: 10.1126/science.1221063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campagnola PJ, Millard AC, Terasaki M, Hoppe PE, Malone CJ, Mohler WA. Three-dimensional high-resolution second-harmonic generation imaging of endogenous structural proteins in biological tissues. Biophys J. 2002;82:493–508. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Helmchen F, Denk W. Deep tissue two-photon microscopy. Nature methods. 2005;2:932–940. doi: 10.1038/nmeth818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beerling E, Ritsma L, Vrisekoop N, Derksen PW, van Rheenen J. Intravital microscopy: new insights into metastasis of tumors. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:299–310. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jung S, Aliberti J, Graemmel P, Sunshine MJ, Kreutzberg GW, Sher A, Littman DR. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cahalan MD, Parker I. Choreography of cell motility and interaction dynamics imaged by two-photon microscopy in lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:585–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matheu MP, Cahalan MD, Parker I. Immunoimaging: studying immune system dynamics using two-photon microscopy. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1101/pdb.top99. pdb top99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bousso P. T-cell activation by dendritic cells in the lymph node: lessons from the movies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:675–684. doi: 10.1038/nri2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grigorova IL, Schwab SR, Phan TG, Pham TH, Okada T, Cyster JG. Cortical sinus probing, S1P1-dependent entry and flow-based capture of egressing T cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:58–65. doi: 10.1038/ni.1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grigorova IL, Panteleev M, Cyster JG. Lymph node cortical sinus organization and relationship to lymphocyte egress dynamics and antigen exposure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20447–20452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009968107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shiow LR, Rosen DB, Brdickova N, Xu Y, An J, Lanier LL, Cyster JG, Matloubian M. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-alpha/beta to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature. 2006;440:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature04606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bankovich AJ, Shiow LR, Cyster JG. CD69 suppresses sphingosine 1-phosophate receptor-1 (S1P1) function through interaction with membrane helix 4. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22328–22337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pham TH, Baluk P, Xu Y, Grigorova I, Bankovich AJ, Pappu R, Coughlin SR, McDonald DM, Schwab SR, Cyster JG. Lymphatic endothelial cell sphingosine kinase activity is required for lymphocyte egress and lymphatic patterning. J Exp Med. 2010;207:17–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wei SH, Rosen H, Matheu MP, Sanna MG, Wang SK, Jo E, Wong CH, Parker I, Cahalan MD. Sphingosine 1-phosphate type 1 receptor agonism inhibits transendothelial migration of medullary T cells to lymphatic sinuses. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1228–1235. doi: 10.1038/ni1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park C, Hwang IY, Sinha RK, Kamenyeva O, Davis MD, Kehrl JH. Lymph node B lymphocyte trafficking is constrained by anatomy and highly dependent upon chemoattractant desensitization. Blood. 2012;119:978–989. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-364273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sinha RK, Park C, Hwang IY, Davis MD, Kehrl JH. B lymphocytes exit lymph nodes through cortical lymphatic sinusoids by a mechanism independent of sphingosine-1-phosphate-mediated chemotaxis. Immunity. 2009;30:434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmidt EE, MacDonald IC, Groom AC. Comparative aspects of splenic microcirculatory pathways in mammals: the region bordering the white pulp. Scanning Microsc. 1993;7:613–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mebius RE, Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:606–616. doi: 10.1038/nri1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu TT, Cyster JG. Integrin-mediated long-term B cell retention in the splenic marginal zone. Science. 2002;297:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.1071632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cinamon G, Zachariah MA, Lam OM, Foss FW, Jr, Cyster JG. Follicular shuttling of marginal zone B cells facilitates antigen transport. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:54–62. doi: 10.1038/ni1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Girkontaite I, Sakk V, Wagner M, Borggrefe T, Tedford K, Chun J, Fischer KD. The sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) lysophospholipid receptor S1P3 regulates MAdCAM-1+ endothelial cells in splenic marginal sinus organization. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1491–1501. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arnon TI, Horton RM, Grigorova IL, Cyster JG. Visualization of splenic marginal zone B-cell shuttling and follicular B-cell egress. Nature. 2013;493:684–688. doi: 10.1038/nature11738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Machlus KR, Italiano JE., Jr The incredible journey: From megakaryocyte development to platelet formation. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:785–796. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang L, Orban M, Lorenz M, Barocke V, Braun D, Urtz N, Schulz C, von Bruhl ML, Tirniceriu A, Gaertner F, Proia RL, Graf T, Bolz SS, Montanez E, Prinz M, Muller A, von Baumgarten L, Billich A, Sixt M, Fassler R, von Andrian UH, Junt T, Massberg S. A novel role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor S1pr1 in mouse thrombopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2012;209:2165–2181. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Golfier S, Kondo S, Schulze T, Takeuchi T, Vassileva G, Achtman AH, Graler MH, Abbondanzo SJ, Wiekowski M, Kremmer E, Endo Y, Lira SA, Bacon KB, Lipp M. Shaping of terminal megakaryocyte differentiation and proplatelet development by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor S1P4. FASEB J. 2010;24:4701–4710. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-141473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. Genetic regulation of osteoclast development and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:638–649. doi: 10.1038/nrg1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ishii M, Egen JG, Klauschen F, Meier-Schellersheim M, Saeki Y, Vacher J, Proia RL, Germain RN. Sphingosine-1-phosphate mobilizes osteoclast precursors and regulates bone homeostasis. Nature. 2009;458:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature07713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ishii M, Kikuta J. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling controlling osteoclasts and bone homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kikuta J, Kawamura S, Okiji F, Shirazaki M, Sakai S, Saito H, Ishii M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate-mediated osteoclast precursor monocyte migration is a critical point of control in antibone-resorptive action of active vitamin D. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7009–7013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218799110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Walzer T, Chiossone L, Chaix J, Calver A, Carozzo C, Garrigue-Antar L, Jacques Y, Baratin M, Tomasello E, Vivier E. Natural killer cell trafficking in vivo requires a dedicated sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1337–1344. doi: 10.1038/ni1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jenne CN, Enders A, Rivera R, Watson SR, Bankovich AJ, Pereira JP, Xu Y, Roots CM, Beilke JN, Banerjee A, Reiner SL, Miller SA, Weinmann AS, Goodnow CC, Lanier LL, Cyster JG, Chun J. T-bet-dependent S1P5 expression in NK cells promotes egress from lymph nodes and bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2469–2481. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Czeloth N, Bernhardt G, Hofmann F, Genth H, Forster R. Sphingosine-1-phosphate mediates migration of mature dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:2960–2967. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Olivera A, Mizugishi K, Tikhonova A, Ciaccia L, Odom S, Proia RL, Rivera J. The sphingosine kinase-sphingosine-1-phosphate axis is a determinant of mast cell function and anaphylaxis. Immunity. 2007;26:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Olivera A, Rivera J. An emerging role for the lipid mediator sphingosine-1-phosphate in mast cell effector function and allergic disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;716:123–142. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9533-9_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mazo IB, Massberg S, von Andrian UH. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell trafficking. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Green JA, Cyster JG. S1PR2 links germinal center confinement and growth regulation. Immunol Rev. 2012;247:36–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cahalan SM, Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Sarkisyan G, Nguyen N, Schaeffer MT, Huang L, Yeager A, Clemons B, Scott F, Rosen H. Actions of a picomolar short-acting S1P(1) agonist in S1P(1)-eGFP knock-in mice. Nat Chem Biol. 7:254–256. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shimozono S, Iimura T, Kitaguchi T, Higashijima S, Miyawaki A. Visualization of an endogenous retinoic acid gradient across embryonic development. Nature. 2013;496:363–366. doi: 10.1038/nature12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shcherbo D, Murphy CS, Ermakova GV, Solovieva EA, Chepurnykh TV, Shcheglov AS, Verkhusha VV, Pletnev VZ, Hazelwood KL, Roche PM, Lukyanov S, Zaraisky AG, Davidson MW, Chudakov DM. Far-red fluorescent tags for protein imaging in living tissues. Biochem J. 2009;418:567–574. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chudakov DM, Matz MV, Lukyanov S, Lukyanov KA. Fluorescent proteins and their applications in imaging living cells and tissues. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1103–1163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang H, Lee AM, Lui H, McLean DI, Zeng H. A method for accurate in vivo micro-Raman spectroscopic measurements under guidance of advanced microscopy imaging. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1890. doi: 10.1038/srep01890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yasuda R. Imaging intracellular signaling using two-photon fluorescent lifetime imaging microscopy. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2012;2012:1121–1128. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top072090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thurber GM, Figueiredo JL, Weissleder R. Multicolor fluorescent intravital live microscopy (FILM) for surgical tumor resection in a mouse xenograft model. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nobis M, McGhee EJ, Morton JP, Schwarz JP, Karim SA, Quinn J, Edward M, Campbell AD, McGarry LC, Evans TR, Brunton VG, Frame MC, Carragher NO, Wang Y, Sansom OJ, Timpson P, Anderson KI. Intravital FLIM-FRET Imaging Reveals Dasatinib-Induced Spatial Control of Src in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4674–4686. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rubart M. Two-photon microscopy of cells and tissue. Circ Res. 2004;95:1154–1166. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150593.30324.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pawley JB. Handbook of biological confocal microscopy. (3rd ed.) 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lin MZ, McKeown MR, Ng HL, Aguilera TA, Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Adams SR, Gross LA, Ma W, Alber T, Tsien RY. Autofluorescent proteins with excitation in the optical window for intravital imaging in mammals. Chem Biol. 2009;16:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shaner NC, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2005;2:905–909. doi: 10.1038/nmeth819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Drobizhev M, Makarov NS, Tillo SE, Hughes TE, Rebane A. Two-photon absorption properties of fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2011;8:393–399. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.