Abstract

This paper analyzes whether children born to teen mothers in Cape Town, South Africa are disadvantaged in terms of their health outcomes because their mother is a teen. Exploiting the longitudinal nature of the Cape Area Panel Study, we assess whether observable differences between teen mothers and slightly older mothers can explain why first-born children of teen mothers appear disadvantaged. Our balanced regressions indicate that observed characteristics cannot explain the full extent of disadvantage of being born to a teen mother, with children born to teen mothers continuing to have significantly worse child health outcomes, especially among coloured children. In particular, children born to teens are more likely to be underweight at birth and to be stunted with the disadvantage for coloured children four times the size for African children.

Keywords: Teenage childbearing, child health outcomes, South Africa, propensity score reweighting

1. Introduction

Childhood health is not only important in its own right but has been shown to be an important determinant of socioeconomic conditions in childhood, young adulthood and middle age (see Currie 2009 for a recent review and Yamauchi 2008; Victora et al. 2008 for South African expositions); it forms a foundation from which subsequent outcomes are affected. In developing countries, teenage childbearing is common and the extent to which being born to a teen mother puts children at risk for poor health outcomes is an important policy question. Children born to teenage mothers may be at risk for poor health outcomes if teens are biologically and psychosocially less mature and therefore less prepared to face pregnancy, childbirth and subsequent childcare (Zabin and Kiragu 1998). Early childbearing is commonly associated with worse maternal socio-economic outcomes including lower levels of education and poor labour market prospects which in turn could negatively impact the well-being of their children.

Estimating the causal effect of being born to a teen mother on a child’s health outcome presents the same difficulties as isolating the impact of early childbearing on maternal outcomes. The empirical challenge is how to disentangle whether an adverse outcome is a result of the early timing of the birth or a consequence of other existing social and economic disadvantages. If the perceived adverse outcomes for children are a result of selection of women from poorer socio-economic status into early childbearing, policy directed at reducing teenage childbearing will not reduce the disadvantage these children face; they would experience adverse outcomes even if their mother delayed childbearing beyond her teens.

The large literature from developed countries on the consequences of early childbearing for the teen mother uses a range of approaches to control for this unobserved heterogeneity, namely instrumental variables, ‘natural’ experiments and family fixed effects. An additional ‘selection-on-observables’ approach uses measured pre-childbearing characteristics to assess whether differences in these characteristics can explain differences in outcomes observed for teenage mothers. This approach answers the slightly different, albeit similarly important, questions of whether observable differences prior to giving birth can explain the disadvantage in outcomes experienced by teen mothers.

International studies, predominantly from the United States and United Kingdom, generally find a negative association between teen childbearing and a range of socio-economic outcomes that is no longer significant once selection into teen childbearing is accounted for (see Hoffman 1998 for a review). The literature on the intergenerational consequences of early childbearing is smaller and there are very few studies that control for selection into teen childbearing. Most of these studies rely on cousin or sibling fixed effects to isolate the impact of the mother’s young age at birth (Geronimus and Korenman 1993; Geronimus et al. 1994; Rosenzweig and Wolpin 1995; Turley 2003; Levine et al. 2007; Francesconi 2008). Other studies (Hofferth and Reid 2002; Levine et al. 2001; Rosenzweig and Wolpin 1995) use panel data to control for pre-childbearing characteristics in a multivariate framework.

The literature on the outcomes of children born to teen mothers focuses on educational and behavioural outcomes (Geronimus et al. 1994; Hofferth and Reid 2002; Turley 2003; Levine et al. 2001; Levine et al. 2007; Francesconi 2008). Two papers examine health outcomes of children born to teen mothers, specifically. Geronimus and Korenman (1993) use a cousin fixed effects framework to assess whether there is a teen-mother-child-health-disadvantage using the US National Longitudinal Study of Youth. They investigate the incidence of low birthweight and some pre and post childbirth maternal health behavioural outcomes, including prenatal care, smoking and drinking during pregnancy, breastfeeding and well child visits. Once pre-childbirth characteristics common between sisters who give birth are controlled for, they find very limited evidence of a link between poor child health and maternal age. Later initiation of prenatal care and a higher incidence of smoking during pregnancy among teen mothers were the only outcomes found to remain significant after adjusting for family background (Geronimus and Korenman 1993). Using the same data, Rosenzweig and Wolpin (1995) compare results on the effect of teenage childbearing on gestational age and child birthweight using both a cousin fixed effects and a sibling fixed effects2 specification. In line with the findings of Geronimus and Korenman (1993) they find no evidence that children born to teen mothers are at risk of lower birthweight in either specification, and find only marginal differences in gestational age when siblings are compared.

Evidence on the causal impact of teen childbearing in the developing world is scarce, mainly due to data limitations. In contrast to the literature from the developed world, two recent South African studies document significant educational deficits for teen mothers that cannot be explained by their pre-fertility characteristics or education trajectories (Ranchhod et al. 2011; Ardington et al. forthcoming). We found no developing countries studies that estimate the causal relationship between being born to a teen and child health outcomes3.

This paper examines whether children in Cape Town, South Africa, born to teen mothers have worse health outcomes than children born to older mothers once pre-childbirth observed characteristics are controlled for. We use the Cape Area Panel Study (CAPS) data, a uniquely rich longitudinal dataset of youths and their children in Cape Town. Our main econometric challenge is to account for characteristics which affect both the mother’s odds of becoming a teen mother and the child’s outcomes; in other words to find a plausible counterfactual that allows us to best isolate whether children born to teen mothers are at a disadvantage. The richness of the data and the length of the panel enable us to go quite some way towards controlling for selection into teenage childbearing and hence for the socioeconomic status into which the child is born.

We use a propensity score reweighting approach. This method relies on the assumption that, conditional on observable characteristics, sample selection into being born to a teen mother is random. Given the richness of the CAPS data, this assumption is more believable than it might otherwise be. More specifically, the data contain information on maternal characteristics prior to the birth of the child, including age at sexual debut, contraception use at first sexual encounter and other factors that might influence the probability of falling pregnant during adolescence. To our knowledge, this paper is the first to estimate the intergenerational consequences of teen childbearing using a propensity score approach to address selection.

We find evidence that the health outcomes of children born to teen mothers are adversely affected. Children born to teen mothers are significantly more likely to be born with low birthweight, are shorter and are more likely to be stunted. We find no evidence of a negative effect on head circumference at birth.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses the data, sample and outcome variables. Section 3 sets out the methodology. Section 4 discusses the underlying assumptions of the method used and tests for their validity in our data before presenting the regression analysis. Section 5 presents a discussion and concludes.

2. Data, sample and outcome variables

2.1 The Cape Area Panel study

The analysis makes use of the Cape Area Panel Study (CAPS). The CAPS is a longitudinal study of youth in Cape Town. The first wave of the CAPS was collected in 2002 (Wave 1) and included 4,752 young people aged 14–22. Youth respondents were re-interviewed in 2003 or 2004 (Wave 2), in 2005 (Wave 3), in 2006 (Wave 4) and in 2009 (Wave 5). Data from waves 1 through 4 are used in this paper. Details about the CAPS are available in Lam et al. (2008).4

The main instrument was a young adult questionnaire which was administered to up to three resident youths aged 14–22 in each sampled household. In addition to this primary questionnaire a household questionnaire collected basic information on all household members (the household roster) as well as household level information. The young adult questionnaire covered a wide range of issues including schooling, sexual practices, fertility and childhood home environment. Wave 1 asked retrospective questions on schooling, living arrangements and marital status for each age from birth. In Waves 1, 3 and 4 young adults completed a detailed birth history, with each additional wave adding subsequent births. In Wave 4, a child questionnaire collected information on all children born to female young adults who were successfully interviewed in this wave. This child sample is the basis of the analysis in this paper. The child questionnaire included current physical measurements, weight-for-age measurements since birth and head circumference at birth. These measures are the child health outcomes assessed.

Thus the CAPS data contains detailed information about the mother’s individual and household characteristics both before and after the birth of her child in addition to measures of her children’s health. This affords us the opportunity to use propensity score reweighting to explore whether maternal age at birth affects the health outcomes of children living in Cape Town.

2.2 Analysis sample and attrition

The analysis sample consists of first born African and coloured children. Due to the low frequency of births in the white population group, the children of white respondents were excluded from the sample. Indians are not represented in the CAPS data as the percentage of the population that is Indian in the Western Cape is very small. The sample is restricted to first born children to avoid potential birth order biases5.

Table A1 presents information on the sample. Forty-two percent of female respondents who were successfully re-interviewed in wave 4 had given birth. Together they had given birth to 920 children by wave 4. The child questionnaire was successfully administered for 832 of these children, resulting in a final analysis sample of 686 first born children, 56.6% of whom were born to teen mothers.

The variable of interest is being born to a teen mother, defined as being born to a woman before her 20th birthday. Table A1 shows that 58% of CAPS female respondents had not yet begun their childbearing by wave 4. However, Table B1 shows that the majority of respondents who had not yet given birth were young. There is a rapid increase in the percentage who had given birth from age 19 onwards, such that over two thirds of 24 year olds had already given birth by wave 4. Table B2 presents the age distribution of mothers at the birth of their first child. The table highlights that the majority of teen mothers in the sample were in their late teens at the birth of their first child while the majority of older mothers were in their early twenties; the average age of teen mothers at first birth is 17.6 and the average age of older mothers is 21.6.

In the analysis we therefore compare the outcomes of children born to teen mothers to the outcomes of children born to mothers between the age of 20 and 27. Thus we estimated the average disadvantage of being born to a teen mother versus a mother who first gave birth in her early twenties.

The target sample includes African and coloured respondents who have had children by wave 4. Table B.3 presents further information on the characteristics of all African and coloured female respondents who could potentially be in our sample of interest. The sample included in the analysis comprises 53% of this total potential sample, yet the majority of those for whom we have no information (37% of the total potential sample), are respondents for women we have no information as to whether they have given birth or not by wave 4 as they had not given birth when they were last interviewed6. Given that we do not know whether these women gave birth in their teens, we cannot calculate their propensity scores but comparing the characteristics of this group to the analysis sample, they look on average more socioeconomically advantaged, especially those who had not given birth by wave 3. The remaining 10% (128 observations) had given birth prior to wave 4 but were either not interviewed in wave 4 or had incomplete child questionnaires and therefore could not be included in the analysis. This group looks fairly similar on characteristics to those in the analysis sample.

Observing differences between Africans and coloureds, we see that the proportion of respondents from the potential sample that are included in the analysis sample is larger in the coloured versus African group – 58% versus 49%. In addition, the proportion that had not given birth by wave 3 and was not interviewed in wave 4 (the group least likely to actually have given birth and therefore to be legitimately part of the sample) is higher in the coloured group. This means that overall the coloured analysis sample is likely to be more representative of the sample of individuals who have given birth by wave 4 than the African group.

2.3 Outcome variables

Three primary child health outcomes are used in the analysis, namely weight and head-circumference at birth and current height for age z-scores (HAZ) for children over six months. 7 In addition, indicators of malnutrition or extreme adverse outcomes are constructed. These measures indicate whether the child had low birthweight (under 2.5kg), had a very small head at birth and whether their height-for-age at the time of the survey would classify them as stunted. The small head at birth and stunted indicators are defined as head-circumference at birth (HC0Z) and height-for-age (HAZ) z-scores more than two standard deviations below the median score for the World Health Organisation (WHO) reference population (WHO 2006).

Following WHO recommendations, values for HAZ more than six standard deviations below or above the median were deemed biologically implausible and set to missing (28 cases). Similarly, values of HC0Z above or below five standard deviations from the median were set to missing (16 cases). Ten percent of heights, 22% of birth weights and 37% of birth head circumferences are missing due to ‘don’t know’ responses and refusals. Thus the final samples for the regressions on stunted, low birthweight and small head at birth are 613, 533 and 420 respectively. Table 1 presents a summary of the outcome variables for the sample as a whole and for Africans and coloureds separately. Overall 14 percent of children are born underweight, 16 percent are born with heads below the recommended size and more than one third of the sample is classified as stunted, with the average HAZ score more than a standard deviation below (−1.21) the reference median.

Table 1.

Child outcomes by teen versus older mothers (first born children only)

| All African and coloured children

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Born to Teen Mothers | Born to Older Mothers | Diff. (Teen-older) | ||||

| N | Mean | N | Mean | N | Mean | T-stat | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| WAZ at birth | 533 | −0.72 | 288 | −0.81 | 245 | −0.60 | −1.82 |

| Birthweight <2.5 kg | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 2.29 | |||

| HCZ at birth | 420 | −0.69 | 222 | −0.82 | 198 | −0.53 | −1.78 |

| Small head | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.89 | |||

| HAZ | 613 | −1.21 | 347 | −1.40 | 266 | −0.93 | −2.56 |

| Stunted | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 1.68 | |||

| African children only

| |||||||

| WAZ at birth | 287 | −0.52 | 134 | −0.59 | 153 | −0.45 | −0.81 |

| Birthweight <2.5 kg | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.86 | |||

| HCZ at birth | 234 | −0.33 | 110 | −0.46 | 124 | −0.21 | −1.32 |

| Small head | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.44 | |||

| HAZ | 306 | −1.08 | 156 | −1.14 | 150 | −1.02 | −0.62 |

| Stunted | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.29 | −0.22 | |||

| Coloured children only

| |||||||

| WAZ at birth | 246 | −0.84 | 154 | −0.91 | 92 | −0.73 | −1.19 |

| Birthweight <2.5 kg | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 2.18 | |||

| HCZ at birth | 186 | −0.93 | 112 | −1.02 | 74 | −0.80 | −0.90 |

| Small head | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.42 | |||

| HAZ | 268 | −1.33 | 178 | −1.50 | 90 | −1.01 | −1.64 |

| Stunted | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 1.07 | |||

Means weighted for sample design and non-response and sample sizes (N) presented.

The first panel of Table 1 shows that while the difference between the mean WA0Z score for children born to teen versus older mothers is not significant, there is a significant difference in the percentage classified as having low birthweight. Seventeen percent of children born to teens are born under 2.5 kilograms compared to 10% of children born to older mothers. The second and third panel of Table 1 show that this mean difference is driven by differences found between teen and old mothers within the coloured sample. Coloured children born to teens are twice as likely to be born with low birthweight compared to coloured children born to older mothers. African children born to teens are not significantly more likely to be born with low birthweight compared to the African children of older mothers. The opposite is true for the height-for-age measures. Children born to teen mothers have significantly lower HAZ scores than children born to older mothers but there is little difference in the proportion classified as stunted. Once again, the difference between children born to teen versus older mothers is driven by a larger difference in the coloured sample, with differences in the African sample not significant. No significant head size differences are found between children born to teen versus older mothers.

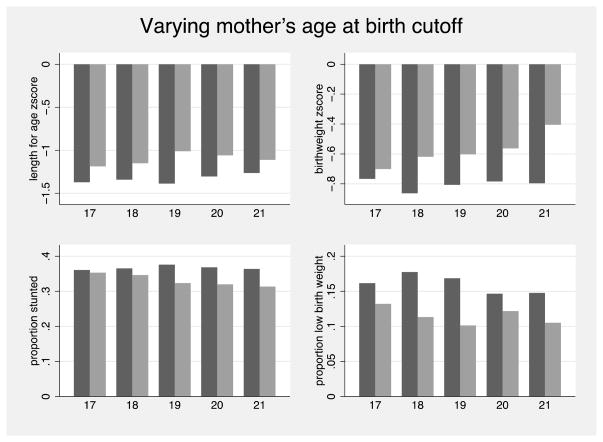

Given the arbitrary definition of a teenage mother, Figure 1 presents mean child outcomes for children born to teen versus older mothers varying the definition of teen versus older mother. For example, the first two bars in the lower left-hand panel shows the proportion stunted among children born to mothers who were 17 or under versus those children born to mothers who were older than 17 at their birth. We see that while there are differences depending on the definition of teenage childbearing, children born to teen mothers always have, on average, worse child outcomes.

Figure 1.

Notes: The figure presents the average length-for-age and birthweight zscores and the proportion of children born stunted and with low birth weight for children born to teen (black bar) versus older (grey bar) mothers where the definition of teen versus older mother is defined by the age specified on the x-axis.

We have shown that the anthropometric outcomes of children born to teen versus older mothers differ on some dimensions. However, the differences presented in Table 1 and Figure 1 are confounded by pre-childbirth factors and therefore cannot be interpreted as necessarily being related to being born to a teen mother.

2.4 Differences in teen versus older mothers’ characteristics

A recent review of the literature on the determinants of teenage childbearing in South African finds that teenage pregnancy is a “result of a complex set of varied and inter-related factors, largely related to the social conditions under which children grow up” (Panday et al. 2009, 15). Table 2 presents mean maternal characteristics by teen mother status with the choice of variables informed by this literature. For example, children who grow up in poor households, without their parents, especially with the absence of their mother, are expected to have a higher risk of teenage childbearing. Students that do poorly at school are more likely to drop out and have less motivation to prevent pregnancy. On the other hand, Lam et al. (2009) find that students in Cape Town who progress through school without failing a grade are exposed, as a result of high repetition rates, to older peers and therefore could be at risk of earlier sexual debut. This is consistent with the finding that teenage pregnancy rates are higher in schools where primary and secondary grades are combined. Similarly, girls who reach menarche at a younger age have a longer period during their teens during which they are exposed to falling pregnant. Social environments where communication about sex is limited or where power relationships between men and women are imbalanced are also found to be associated with higher teen fertility. As such we include controls to measure mothers’ individual demographic characteristics, schooling outcomes prior to giving birth, childhood household characteristics, her parent’s education, her childhood living arrangements and information about her first sexual experience.

Table 2.

Mean maternal characteristics

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Coloured | African | ||||||

| Teen | Older | Coloured | African | Teen | Older | Teen | Older | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Teen mother | 0.63 | 0.50*** | ||||||

| Age in wave 4 | 21.82 | 23.91*** | 22.60 | 22.85 | 21.82 | 23.95*** | 21.83 | 23.86*** |

| African | 0.30 | 0.42*** | ||||||

| Childhood household poor or very poor | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.29*** | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.31 |

| Neighbourhood income level | 10.54 | 10.44* | 10.80 | 9.94*** | 10.79 | 10.83 | 9.97 | 9.91 |

| Wave 1 household owns 5 or more books | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.62*** | 0.80 | 0.94*** | 0.68 | 0.57** |

| Mother’s education | 7.70 | 7.61 | 7.78 | 7.45 | 7.77 | 7.80 | 7.55 | 7.34 |

| Father’s education | 7.58 | 7.79 | 8.21 | 6.62*** | 8.03 | 8.51 | 6.46 | 6.77 |

| Proportion of life lived with mother | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.77*** | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.77 |

| Proportion of life lived with father | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.48*** | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| Proportion of life lived with maternal grandparent(s) | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.24* | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.23 |

| Drug addict in childhood household | 0.14 | 0.08* | 0.15 | 0.04*** | 0.18 | 0.10* | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Alcoholic in childhood household | 0.27 | 0.18** | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.18** | 0.24 | 0.19 |

| Highest grade at age 12 | 5.44 | 5.19** | 5.67 | 4.72*** | 5.69 | 5.63 | 4.84 | 4.60 |

| Failed a grade by age 12 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.23* | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.21 |

| Standardised numeracy and literacy score | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.09** |

| Age at menarche | 13.22 | 13.62*** | 12.93 | 14.23*** | 12.94 | 12.92 | 13.88 | 14.58*** |

| Age at first sex | 16.32 | 18.01*** | 17.30 | 16.51*** | 16.49 | 18.71*** | 15.92 | 17.10*** |

| Used condom at first sex | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.36 |

| Sample size | 388 | 298 | 334 | 352 | 215 | 119 | 173 | 179 |

Means weighted to account for sample design and non-response. Sample includes all African and coloured female respondents whose first-born child forms part of the analysis sample. Asterisks signify significant differences between prior two columns. Differences marked with three asterisks (***) are significant at the 1% level, those marked with two (**) are significant at the 5% level, and those marked with one (*) are significant at the 10% level.

The first two columns of Table 2 stratify characteristics by teen versus older mother. In contrast to the majority of findings in the literature, but consistent with the Ardington et al. (forthcoming) analysis of teen mothers in South Africa, teen mothers in our sample do not appear to come from worse socioeconomic backgrounds. In fact, teen mothers fare significantly better on some variables. Teen mothers are, however, significantly more likely to report being exposed to drugs and alcoholism in their childhood household and start having sexual intercourse at significantly younger ages compared to older mothers.

The similarity in socioeconomic levels between teen and older mothers is, in part, a result of the higher representation of coloured respondents in the teen group. The apartheid system classified the population into four groups, namely African, coloured, Indian/Asian and white. This classification was used to differentiate the rights and opportunities of each group. While all blacks were discriminated against, Africans had the most severe discrimination, with Indian/Asian and coloureds having greater rights and opportunities than Africans but fewer than whites. The consequences of these discriminatory policies are evident in the comparison between columns 3 and 4 of Table 2 where the mean characteristics of coloureds and Africans are compared. Coloured mothers are more advantaged than African mothers, even though the proportion of coloureds who give birth in their teens is higher.

Yet, even if teen and older mothers are compared within population group, differences in characteristics are small and not significant on most measures. There are however some important differences. For coloureds, columns 5 and 6 show that more coloured teen mothers report the presence of drug users and alcoholics in their childhood households, are more likely to have lived in households with few or no books and start having sex at a younger age. A comparison of columns 7 and 8 shows that while African teen mothers have lower literacy and numeracy scores and start having sex at a younger age, they are less likely to report living in a household with few or no books and reach menarche, a measure associated with better nutrition, at a younger average age. Thus it is not clear that African teen mothers come from significantly more disadvantaged households although they appear to have some distinct individual characteristics in their teens.

Three of the key characteristics that differ between mothers who gave birth in their teens versus those who gave birth at an older age are the presence of drugs and alcohol in their childhood household, the age they first have sexual intercourse and their numeracy and literacy scores. Table B4 compares the outcomes of children born to teen versus older mothers for subsamples with these risk characteristics– mothers who grow up in substance abuse (either alcohol or drugs) households, have their first sexual experience before age 17 and have numeracy and literacy scores below the standardized mean.

If we look at the subpopulation of children born to mothers who were exposed to drugs and/or alcohol during childhood, the health outcome deficit for children born to teen mothers, with the exception of the height measures, is much larger than within the overall sample. This is particularly true for the incidence of children being born with heads below the WHO standard. Nine percent of children born to older mothers in this risk group are reported to have small heads at birth compared to 30% of children born to teen mothers. This is a symptom associated with fetal alcohol syndrome and could in fact signify that the teen mothers themselves are abusing substances during their pregnancy. Differences between children born to teen versus older mothers are smaller within the other identified risk groups. Children born to teens are only found to be more likely to have low height for age when compared to children born to older mothers in the group with low numeracy and literacy scores. Within the group who first had sex before age 17, children born to teens have lower height-for-age and birth weight z-scores, but are not more likely to be stunted or to be underweight at birth.

Thus even within these risk groups, children born to teenage mothers are found to have worse outcomes on average than children born to older mothers. In each case the teen mean value shows a higher risk of the poor outcome, but the difference is not always found to be significant. In addition, as in Table 1, the fact that the sample of children born to teen mothers is more likely to be coloured interacts with socioeconomic status.

We have shown that the socioeconomic status of the aggregated teen sample is comparatively high given the higher proportion of coloured versus African children born to teen mothers in this sample. This could suggest that the differences in mean child health outcomes observed between children born to teen versus older mothers in Table 1 underestimate the actual impact on child health. We turn to propensity score reweighting to investigate whether observed differences in maternal attributes can explain the difference in health outcomes of children born to teen versus older mothers.

3. Methodologies

The literature on the consequences of early childbearing attempts to answer the question of whether the child, if born to the same mother at a later age would fare better on the measured outcomes. The empirical challenge is how to isolate the causal impact of the early timing of the birth from other existing social and economic disadvantages. While this question is inherently not answerable, four primary methodologies are used in the teen childbearing literature to construct, under specific assumptions, plausible counterfactuals. These methodologies can broadly be classified as controlling for unobserved heterogeneity using instrumental variables, ‘natural’ experiments, family fixed effects and ‘selection-on-observables’ approaches.

Each methodological approach has advantages and disadvantages. The instruments and natural experiments used in the current literature are not appropriate (or available) for the analysis of the health outcomes for children born to teen mothers in Cape Town. Similarly, it is questionable whether the fixed effects approach is appropriate for the assessment of the effect of being born to a teen mother on anthropometric outcomes given genetic similarities between siblings/cousins. In addition, the number of mothers in CAPS who have had more than one child, or siblings with differential fertility timing, is small and therefore limits the possibility of this approach anyway. The wealth of information available in the CAPS panel, makes the selection-on-observables methodologies most appropriate. The ‘selection-on-observables’ approach investigates the question of whether observable pre-childbearing differences between teen mothers and older mother can explain why children of teen mothers appear disadvantaged. This is the question addressed in this paper and entails creating a comparison group of older mothers who have similar observed pre-childbearing characteristics to teen mothers with the exception that they gave birth at an age older than nineteen. We follow the notation used in the program evaluation literature.

Children born to teen mothers receive the ‘treatment’ in the program evaluation literature sense, denoted by binary variable Ti. Let Yi(1)denote the outcome child i would obtain under treatment and Yi(1) the outcome obtained if the child is born to a mother who was older than nineteen. Yi = TiYi(1) + (1 − Ti) Yi(0) is observed, but never the pair (Yi(1), Yi(0)); a child is either born to a teen mother or an older mother. Let the propensity score, in other words the conditional probability of being born to a teen mother, be denoted by p(x) ≡ P(Ti = 1|Xi = x), where Xi is a list of the mother’s pre-childbirth characteristics. Let α(x) = E[Yi(1) − Yi(0) | Xi = x] denote the covariate-specific average treatment effect. We are interested in estimating the average treatment effect on the treated denoted by ATT(x) = E[α(x) | Ti =1] (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983).

Two assumptions underlie the consistent estimation of the teen mother coefficient. The first assumption, commonly referred to as the selection-on-observables assumption, requires that, given Xi, the set of observed covariates, treatment is random (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983). This assumption allows the construction of a hypothetical counterfactual for teen mothers from women who did not give birth in their teens but are similar on observed variables that affect both the potential outcomes and the probability of being a teen mother.

The second assumption, the overlap or common support assumption, requires that no value of the observed covariates predict treatment assignment exactly. Formally, the common support assumption required to estimate the ATT is p(x) < 1 (Angrist and Pischke 2009). This assumption ensures that the estimates are calculated off a sample in which both the treated and control observations have values for the observed covariates. This avoids the calculation of estimates on parts of the sample where the covariate distributions of the treatment and controls do not overlap (Angrist and Pischke 2009), i.e. avoids out of sample extrapolation.

A hypothetical counterfactual for teen mothers can be calculated by reweighting the group of women who did not give birth in their teens. In this way the ATT is estimated as the difference in the average outcomes between the treated observations and a group of controls weighted by their covariate similarity to the treated observations. Specifically, Busso et al. (2009) show that when , where w̄ij is the weight defined below, the general notation for the reweighting estimators of ATT is

| (1) |

where is the average weight observation j in the control group (older mothers) receives across all treatment observations i (Busso et al. 2009).

We use a double robust specification to estimate the ATT (Robins et al. 1995). This means we are interested in calculating β1 in the following weighted regression.

| (2) |

where β1 is an estimate of the relationship between being born to a teen mother and the outcome of interest, is a vector of characteristics, p̂(xj) is the estimated propensity score and εi is the error term. Ordinary least squares regressions are used for continuous outcomes and probit regressions are used for binary outcomes. A cubic function of the propensity score is included in the specification as in the instance that the outcome equation is correctly specified but the function of the propensity score is misspecified, this estimator will be more consistent than just reweighting by the inverse propensity score weight (Robins et al. 1995). The weight constructed to estimate β1 in equation 2 is a two-step estimator, relying on first estimating the propensity score and then using this score to construct a weighted counterfactual from the older mother sample.

The weight is constructed as follows

w̄ipw(j) presents Hirano et al.’s (2003) inverse probability weight (IPW) normalised to one. This assigns a weight to children born to older mothers that is proportional to the conditional probability that their mother gave birth in her teens. The weight takes into account the CAPS sample design with SWj denoting the sampling weight provided in the data for observation j. The weights sum to one by design.

4. Analysis

4.1 An appropriate counterfactual

The plausibility of the selection-on-observables assumption rests on whether the data are informative enough to account for selection into teenage childbearing. The longitudinal nature of the CAPS data supplemented with the retrospective calendar, provide us with a rich set of variables to measure individual mother and household characteristics prior to the birth of her first child. In addition to the usual demographic variables, the CAPS data collected detailed information about educational progress, sexual history (including age at menarche, sexual debut and protection used during first sexual experience), childhood living arrangements by age and household characteristics during the mother’s childhood.

We examined the validity of the selection-on-observables assumption by testing whether the observed characteristics of teen versus older mothers are balanced once reweighted by the propensity score weight. First, we checked whether X is orthogonal to the treatment variable given p(x) using the regression based balancing test proposed by Smith and Todd (2005). For every covariate xk the joint null hypothesis that all the coefficients on the terms involving T in equation 3 equal zero was tested using an F-test8

| (3) |

The test relies on the condition that T should provide no information about the observed characteristics conditional on the estimated propensity score (Smith and Todd 2005). When any of these F-statistics exceeded the 5% significance level, higher order and interaction terms of the unbalanced variables were included in the propensity score specification and the regressions rerun9.

Table 2 and Table 3 present all the variables included in the propensity score estimation. Table 2 shows that prior to reweighting the group of older mothers, some variables differ significantly at the mean between teen and older mothers. In particular age at sexual debut, presence of substance abuse in childhood households and numeracy-literacy scores. Table 3 reweights these mean values using the IPW defined above. The difference in the characteristics of teen versus older mothers prior to childbirth is significantly reduced in each of the samples, with most of the differences eliminated.

Table 3.

Internal balancing tests

| Coloured and African | Coloured | African | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (Teen - Older) | Std. Error | T-stat | Sign. Diff. | Difference (Teen - Older) | Std. Error | T-stat | Sign. Diff. | Difference (Teen - Older) | Std. Error | T-stat | Sign. Diff. | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.12 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.56 | −0.48 | 0.35 | −1.37 | |||

| African | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.36 | |||||||||

| Defines childhood household as poor | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.37 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.18 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.93 | |||

| Log of mean household income in Wave 1 subplace | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.45 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.18 | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.19 | |||

| Own 5 books | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.27 | −0.10 | 0.07 | −1.45 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 3.21 | ** | ||

| Mother’s highest level of education | −0.01 | 0.33 | −0.04 | −0.15 | 0.45 | −0.33 | 0.31 | 0.45 | 0.69 | |||

| Father’s highest level of education | −0.28 | 0.46 | −0.60 | −0.65 | 0.61 | −1.07 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.91 | |||

| Proportion childhood lived with mother | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.98 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.57 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −1.03 | |||

| Proportion childhood lived with father | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.75 | −0.02 | 0.10 | −0.22 | −0.12 | 0.07 | −1.58 | |||

| Proportion childhood lived with maternal grandparent | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.17 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.80 | |||

| Drugs in childhood household | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.30 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.62 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −1.05 | |||

| Alcoholic in childhood household | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.18 | |||

| Highest grade by age 12 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.16 | −0.03 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.56 | |||

| Failed grade by age 12 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.23 | −0.05 | 0.11 | −0.47 | |||

| LNE score | −0.18 | 0.17 | −1.10 | −0.08 | 0.22 | −0.36 | −0.40 | 0.25 | −1.61 | |||

| Age of menarche | −0.29 | 0.19 | −1.52 | −0.27 | 0.27 | −1.01 | −0.39 | 0.18 | −2.22 | * | ||

| Age of sexual debut | −0.01 | 0.20 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.05 | |||

| Use condom at first sex | 0.12 | 0.06 | 2.00 | * | 0.10 | 0.08 | 1.32 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 1.92 | ||

The table presents variable means and the difference in means between teen and older mothers, the standard error of this difference and whether it is significant weighted using the CAPS sample weight, the inverse propensity score weight and the kernel weight. Variables included are those used in the propensity score. Differences marked with three asterisks (***) are significant at the 1% level, those marked with two (**) are significant at the 5% level, and those marked with one (*) are significant at the 10% level. The table shows that once the data are weight by the inverse propensity score weight or kernel weight differences between teen and older mother characteristics are minimal or ‘balanced’.

Table A3 compares teen and older mothers’ characteristics that are not included in the propensity score estimation using the sample weight and the IPW weight. Note that outcomes need to be measured prior to childbearing, thus the sample used to calculate mean values for characteristics measured in wave 1 is based on women who gave birth in the panel i.e. after wave 1. Here again we see that teen mothers have worse outcomes than older mothers prior to birth and that the reweighting reduces or eliminates most of these differences, even on these variables not included in the propensity score estimate.

Table 3 and A3 present credible evidence that the sample of teen and older mothers is comparable on characteristics prior to giving birth and therefore the selection-on-observables assumption appears realistic. Thus the reweighted sample of older mothers presents a credible counterfactual group.

4.2 Common support

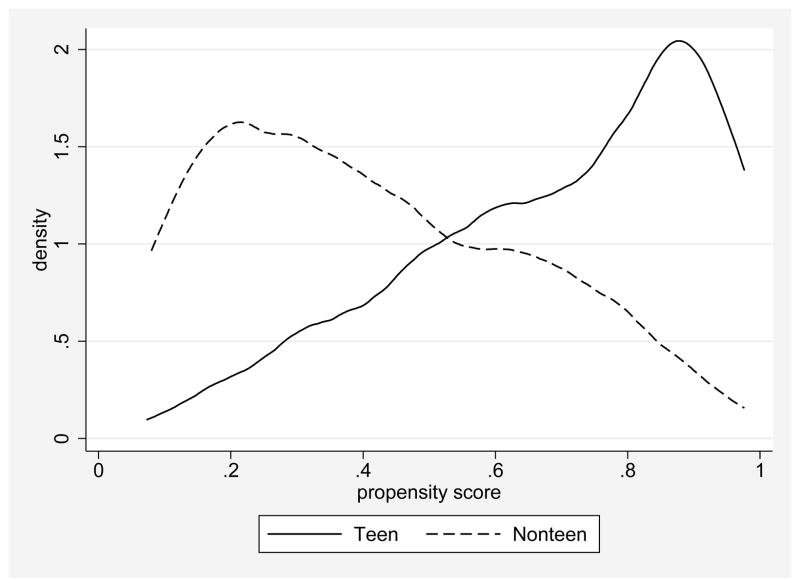

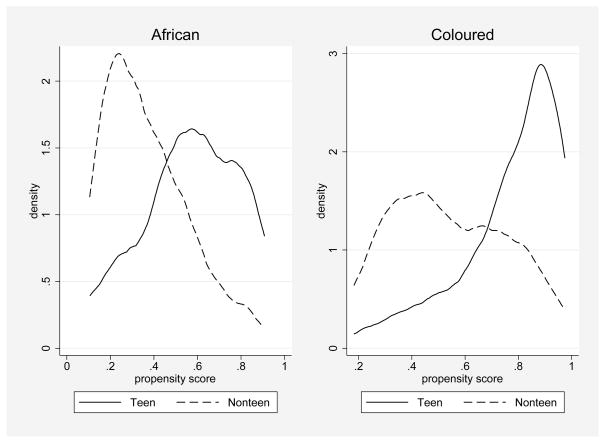

To avoid out of sample extrapolation, the samples were trimmed such that the propensity scores within the teen and older mother groups overlapped. This resulted in 117 observations, 66 teen mothers and 51 older mothers, being excluded from the African and coloured combined sample and 90 (77) observations were outside common support within the coloured (African) only sample– 46 (50) teen mothers, 44 (27) older mothers. Figure 2 shows that the distribution of the estimated propensity score for children born to teen mothers versus older mothers. The overlap of the propensity scores is clearly evident, with the distribution of propensity scores of children born to teen mothers skewed to the left and the distribution of propensity scores of children born to older mothers skewed to the left as would be expected10.

Figure 2. Distribution of the estimated Propensity Scores – common support between teen and older mothers.

Notes: The propensity score is the conditional probability that the child’s mother gave birth to them in her teens. The propensity score is calculated using a logit specification. The variables included in the logit specification are listed in Table 2.

4.3 Regression Results

Table 4 presents estimates of being born to a teen mother11 (β1) on the child health outcome measures. Each cell presents the teen mother coefficient from a different regression. For the dichotomous outcomes, this coefficient is the marginal effect on the teen mother indicator (β1) from a probit specification and for the continuous outcomes, it is the coefficient on the teen mother indicator (β1) from a weighted least squares specification.

Table 4.

Differences in the outcomes of teen births after controlling for observable differences in teen mothers

| (1) | (2) | Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic

|

Balanced

|

||

| WAZ at birth | −0.040 (0.13) | −0.218 (0.16) | 418 |

| low birth weight | 0.065* (0.04) | 0.101*** (0.03) | 418 |

| current HAZ | −0.239 (0.27) | −1.031* (0.54) | 463 |

| stunted | 0.036 (0.06) | 0.185** (0.07) | 463 |

| HCZ at birth | −0.203 (0.19) | −0.355 (0.43) | 323 |

| small head at birth | 0.025 (0.05) | 0.056 (0.06) | 323 |

Marginal effect of being born to a teen mother from weighted probit regression for dichotomous outcomes. Weighted OLS regression used for continuous outcomes. Standard errors presented in parenthesis, bootstrapped for the matching estimates. All regressions include African and male indicators. Height outcomes include an additional quadratic in age in days and mother’s height. The balanced models include controls for maternal grandparent education, wave 1 household income, whether the household owns five or more books and the mother’s score on the literacy-numeracy test. Basic models are weighted using the original CAPS sample weights, Balanced represents the double robust specification using the inverse probability weight. Estimates marked with three asterisks (***) are significant at the 1% level, those marked with two (**) are significant at the 5% level, and those marked with one (*) are significant at the 10% level.

A basic estimate is included in column 1 as a comparison point. It includes only child controls (indicators that the child is African and male and a quadratic in age in days for the height measures). The Matching estimates come from the DR model and include the child controls, characteristics of the mother and her household in 200212 and a cubic function of the propensity score and are weighted by the inverse probability weight. Height outcomes include a control for mother’s height. Robust standard errors are presented in parenthesis and are bootstrapped (Wooldridge 2002, 378) for the matching estimates.

The basic model finds an insignificant association between being born to a teen mother on the child’s weight at birth z-score. Children born to teen mothers have WAZ at birth values 0.04 standard deviations lower than children born to older mothers. The size of the coefficient increases substantially but remains insignificant once the data are reweighted in the DR specification. Children born to teen mothers have WAZ at birth scores close to a quarter of a standard deviation below the average score for children born to older mothers.

The disadvantage that children born to a teen mother face is more apparent when considering whether the child was born under 2.5 kilograms. The basic model estimates show that children born to teen mothers are 6.5 percentage points more likely to be born with low birthweight. The disadvantage of being born to a teen mother increases once the data are reweighted. Children born to teen mothers are around 10 percentage points more likely to be born with low birthweight than children born to older mothers. The teen coefficient is strongly significant.

Height-for-age also appears to be linked to maternal age at childbirth. While the basic model estimates a small and insignificant association between being born to a teen mother and child HAZ or likelihood of being stunted, the balanced estimator is large and significant. Children born to teens are one standard deviation shorter than children born to older mothers and this coefficient is significant. In addition, children born to teen mothers are 18.5 percentage points more likely to be stunted.

Children born to teen mothers are not found to have smaller head circumferences at birth. The coefficient is negative in each specification but the size of the coefficient is small and imprecisely measured.

There is an interesting heterogeneity in the deficit between the height-for-age and birth weight outcomes across the propensity score distribution. If the sample is restricted to only those with propensity scores above the median i.e. to children born to mothers with pre-childbearing characteristics that predict a relatively high probability for teenage childbearing, the height-for-age deficit is larger while the birth weight deficit is smaller. Thus the overall height-for-age deficit is largely driven by this high risk group, while the birth weight deficit is primarily driven by low birth weights among children born to teen mothers among mothers who have pre-childbearing characteristics that predict relatively low probabilities of teenage childbearing.

Table 5 presents the birth weight and height outcomes when reweighting is done within population group. For instance, in the top panel (African only) the sample is restricted to Africans thus the teen counterfactual is constructed based on a propensity score calculated within the African population group. Samples are small once the full sample is stratified into African and coloured and the common support condition enforced. There is therefore limited power to find significant results and we discuss the relative size of the coefficients between Africans and coloureds even if significance is not found.

Table 5.

Underweight at birth and Stunting – differences between Africans and Coloured

| (1)

|

(2)

|

Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic | Balanced | ||

| African only: | |||

| low birth weight | 0.021 (0.05) | 0.036 (0.05) | 213 |

| current HAZ | −0.161 (0.26) | −0.318 (0.42) | 230 |

| stunted | −0.025 (0.07) | 0.046 (0.11) | 230 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Coloured only: | |||

| low birth weight | 0.125*** (0.05) | 0.128* (0.08) | 162 |

| current HAZ | −0.699 (0.434) | −1.254 (0.88) | |

| stunted | 0.086 (0.08) | 0.053 (0.15) | 190 |

Marginal effect of being born to a teen mother from weighted probit regression for dichotomous outcomes. Weighted OLS regression used for continuous outcomes. Standard errors presented in parenthesis, bootstrapped for the Balanced estimates. All regressions include a male indicators. Height outcomes include an additional quadratic in age in days and mother’s height. The Balanced models include controls for maternal grandparent education, wave 1 household income, whether the household owns five or more books and the mother’s score on the literacy numeracy test. The same sample is used for each regression on a common outcome. Basic weighted using the original CAPS sample weights, Balanced represents the double robust specification using the inverse probability weight. African only restricts the sample to Africans resulting in matching within the African population group. Similarly, Coloured only matches individuals within the coloured population group only. Estimates marked with three asterisks (***) are significant at the 1% level, those marked with two (**) are significant at the 5% level, and those marked with one (*) are significant at the 10% level.

The disadvantage of being born to a teen on birth weight is much larger for coloureds than Africans. Coloured children born to teen mothers are around 12 percentage points more likely to have low birthweight than children born to older mothers. The coefficient is a quarter of the size for Africans. African children born to teen mothers are, on average, three percentage points more likely to be born with low birthweight and the standard errors are very large.

Similar, albeit larger, differences are seen between Africans and coloureds for the height-forage measures. Children born to teens in the African sample have z-scores 0.3 standard deviations below children born to older mothers. A much larger disadvantage is seen for coloured children. Children born to coloured teens are 1.3 standard deviations shorter than children born to older mothers.

The ‘pooled’ estimates in Table 4 therefore present the average effect of being born to African and coloured teen mothers in Cape Town. The disadvantage found for children born to teen mothers in the main regression are overestimates for Africans and underestimates for coloureds.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Studies of teenage childbearing and its socioeconomic consequences have been concerned with the bias introduced into the estimation of the ‘true’ effect of teenage childbearing as a result of omitted variables and selection bias. This paper contributes to this debate by using rich longitudinal data to find a statistically appropriate comparison group for children born to teen mothers. The CAPS data contains a complete schooling history for each mother and detailed information on their sexual behaviour and socioeconomic status prior to the birth of their first child. We use these data to extend the current research to examine child health outcomes in the South African context, in metropolitan Cape Town.

We find evidence that children born to teens have worse health outcomes. Children born to teen mothers are more likely to be born with low birthweight, are shorter for their age and are more likely to be stunted. Differences are found between Africans and coloureds; the outcomes of coloured children born to teens when compared to the those born to older coloured mothers, are much worse than is evident in the African sample. Specifically, coloured children born to teen mothers have around four times the disadvantage that is apparent in the African sample. African children born to teen mothers have fairly similar health outcomes when compared to African children born to older mothers.

The finding of significant differences related to maternal age at childbirth even after controlling for observed pre-childbearing characteristics is uncharacteristic of the findings in the teen childbearing literature. Most studies from the predominantly US literature find that selection accounts for almost all of the adverse teen affect apparent in the comparison of simple means. Particular to the outcomes measured in this paper, Geronimus and Korenman (1993) and Rosenzweig and Wolpin (1995) find no causal effect of maternal age on birth weight. We found no studies that examined height-for-age or stunting among children born to teenage mothers. Geronimus and Korenman (1993) do however assess whether teen mothers had worse postpartum behavioural outcomes, two factors that could have an impact the child’s height-for-age. They find no evidence that teen mothers were less likely to breastfeed or take their children to well child appointments.

Finding a negative relationship between outcomes and teenage childbearing does however concur with results from two recent studies in South Africa. Ranchhod et al. (2011) and Ardington et al. (forthcoming) find large educational deficits for teen mothers in South Africa that cannot be explained by pre-childbearing characteristics.

The fact that the balanced estimates in our analysis find a larger deficit for children born to teen mothers than the simlpe comparison of means, suggests that, on average, teen mothers are not more disadvantaged prior to giving birth than older mothers. This differs from the majority of papers in the literature where the average relationship between socioeconomic hardship and teenage childbearing is strong when pre-childbearing characteristics are not taken into consideration. While our finding is partly a function of the large socioeconomic inequalities in South Africa - Table 2 shows that coloured mothers have higher socioeconomic status and a higher prevalence of teenage childbearing – even once the sample is stratified by population group, the pre-childbearing characteristics of teen versus older mothers are not substantially different. In Table 2, it is evident that most of the household resource variables do not differ significantly and African teen mothers actually have significantly better numeracy-literacy scores than older mothers.

The large difference in outcomes between Africans and coloureds is quite distinct. One explanation could be that the socioeconomic costs and benefits of teenage childbearing differ between Africans and coloureds. Geronimus (1996) notes that the effect of young maternal age on child wellbeing is heterogeneous across different groups due to social inequalities. For example, she finds that the incidence of low birthweight babies increases for African American mothers between their late teens and twenties while it decreases for white women. She attributes these differences to higher morbidity rates among African American mothers (Geronimus 1996). In Table 2 we illustrated the persistent socioeconomic inequalities between Africans and coloureds. In comparison to Africans, coloureds fare better on almost every measures of socioeconomic wellbeing. Coloureds have greater per capita household income, smaller families with parents who are more educated, have higher quality of schooling and lower unemployment rates. Thus it is possible that the more detrimental outcomes for children born to coloured teens are a result of different opportunity costs associated with teenage childbearing between Africans and coloureds.

We investigated potential mechanisms (worse maternal socioeconomic circumstance, family support factors and psychosocial factors) that may exist within the African and coloured teen mother subgroups that could contribute to poor child outcomes. Regressions were run with multiple measures from wave 4 for Africans and coloureds separately and weighted by the inverse probability weight. Socioeconomic circumstance included access to household assets such as a fridge, flush toilet, books and an electricity supply, household income and the number of state old age pensions and unemployed people in the household. Family support factors included whether the mother was married at wave 4 and the presence of a grandparent in the household. Finally, psychosocial factors were measured using an indicator that the mother was depressed, in poor health, the number of days she indicated she ate vegetables, use of drugs and alcohol and number of sexual partners in the last twelve months.

Different mechanisms appear to be at play within the African and coloured groups. For Africans, children born to teens lived in significantly poorer households in wave 4. The structure of the households they lived in was also found to be different. Their mothers were less likely to be married and they were more likely to be living with a grandparent. No other factors were found to be significantly different for children born to teen mothers. Although the average wave 4 characteristics of coloured mothers were more advantaged than African mothers, larger differences were found between coloured teen versus older mothers. In particular, psychosocial factors appear to play a bigger role in explaining the difference between teen and older mothers, indicating that the behaviour and choices, or maturity of coloured teen mothers may be contributing factors in their children’s adverse health outcomes. Children born to coloured teen mothers had mothers who were more likely to be classified as depressed, to be in poor health and to eat fewer vegetables. On the other hand, as was found for African children of teen mothers, coloured teen mothers do appear to have increased family support with children born to teen mothers being more likely to live with a grandparent in wave 4. Whether this is a mitigating factor or contributes to the disadvantage the child faces cannot be determined with these data.

This paper shows that children born to teenage mothers in Cape Town, South Africa, have worse child health outcomes than children born to older mothers. Child health forms a foundation from which subsequent outcomes are affected. For example, Yamauchi (2008) finds evidence that height-for-age is a significant predictor of schooling investment and success for children in South Africa. Children classified as the appropriate height for their age, start school earlier, progress through school with fewer grade repetitions and complete more education overall. The estimates in this paper therefore have policy relevance. They suggest that family planning information, education and communication programmes aimed at postponing teenage pregnancies to beyond age 19 could positively affect child health and future outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample Information – African and Coloured children born to female young adults interviewed in Wave 4

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| African and Coloured female respondents in 2002 (Wave 1) | 2300 | |

| African and Coloured female respondents in 2006 (Wave 4) | 1758 | |

| African and Coloured female response rate 2002–2006 | 76.4 | |

| African and Coloured female respondents who had given birth by 2006 | 737 | 41.9 |

| Children born to African and Coloured respondents by 2006 | 920 | |

| Child sample | 832 | |

| Response Rate in Child Sample | 90.4 | |

| First born children - the analysis sample | 686 | |

| % born to teen mothers | 56.6 | |

The analysis sample includes all first born children of African and Coloured female respondents successfully interviewed in 2006. The child sample response rate gives the percentage of children born by 2006 who had a child questionnaire completed on their behalf.

Table A2.

Description of Variables used in Propensity score estimate

| Born to a teenage mother indicator | |

| Teen | Child’s mother gave birth to them before the age of 20 |

| Mother’s characteristics: | |

| Age | Mother’s age at wave 4 interview (2006) -quadratic included |

| Coloured | Indicator that the mother is coloured |

| Numeracy score | Age standardised numeracy score |

| Literacy score | Age standardised literacy score |

| Education | Highest grade completed by age 12 |

| Failed | Mother failed at least one grade by age 12 |

| Menarche | Age at menarche |

| Mother’s first sexual experience: | |

| Sexual debut | Age of sexual debut -quadratic included |

| Condom | Used condom at first sex |

| Mother’s childhood household: | |

| Poor | Mother defines her childhood household as poor or very poor |

| Drugs | When growing up (up to age 14) lived with someone who used street drugs |

| Alcoholic | When growing up (up to age 14) lived with someone who was an alcoholic |

| Live with mother | Proportion of first 13 years (age 0 to 12) that mother lived with her mother |

| Lived with father | Proportion of first 13 years (age 0 to 12) that mother lived with her father |

| Lived with maternal grndprnt(s) | Proportion of first 13 years (age 0 to 12)lived with her maternal grandparent(s) |

| Mother’s education | Mother’s mother’s highest level of education |

| Father’s education | Mother’s father’s highest level of education |

| Mother’s household in Wave 1: | |

| Neighbourhood income | The logarithm of mean household income in Wave 1 subplace |

| Owned 5 books | Someone in Wave 1 household owned 5 or more books |

The table details pre-childbearing observable characteristics from the Cape Area Panel Study data used to predict the probability of having a teen birth.

Table A3.

External balancing tests

| African and coloured | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original sample weight | Inverse probability weight | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Difference (Teen -Older) | Std. Error |

T-stat | Sign. Diff. |

Difference (Teen -Older) | Std. Error |

T-stat | Sign. Diff. |

|

|

| ||||||||

| Schooling | ||||||||

| Failed grade when 10 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.33 | *** | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.68 | |

| First sex | ||||||||

| Use contraception at first sex | −0.09 | 0.05 | −1.91 | *** | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.39 | |

| Wave 1 household characteristics | ||||||||

| Wave 1 household per capita income | −38.74 | 83.25 | −0.47 | *** | −22.04 | 92.42 | −0.24 | |

| Room permanent | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.01 | *** | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.15 | |

| Flush toilet | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.08 | *** | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.12 | |

| Childhood living arrangements | ||||||||

| Lived with mother age 6 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.90 | *** | −0.07 | 0.05 | −1.39 | |

| Lived with mother age 7 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.46 | *** | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.10 | |

| Lived with mother age 9 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.09 | * | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.16 | |

| Lived with father age 7 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.18 | *** | −0.08 | 0.08 | −1.10 | |

| Lived with father age 8 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.09 | * | −0.08 | 0.08 | −1.09 | |

| Lived with father age 9 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.33 | *** | −0.11 | 0.08 | −1.39 | |

| Lived with father age 10 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.07 | *** | −0.09 | 0.08 | −1.20 | |

| Parental time investment | ||||||||

| Father helps with homework | −0.03 | 0.03 | −1.14 | *** | −0.04 | 0.04 | −1.10 | |

| Mother spent time with just YA at least once a month in past 12 months | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.16 | *** | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.53 | |

The table presents the difference in means between teen and older mothers, the standard error of this difference and whether it is significant using the sample weight and the inverse propensity score weight. Variables included are those not included in the propensity score estimation but found to be signficantly different between teen and older mothers when weighted using the sample weight. Other variables not included in the table given that they were not found to be significantly different at base include characteristics of the school – problems, number of learners per class, time taken to school - , failure at other grades, wave 1 asset ownership, living arrangements at other ages since birth and parent time investment – mother helped with homework and discussed personal matters with young adult more than once per month in past 12 months. Differences marked with three asterisks (***) are significant at the 1% level, those marked with two (**) are significant at the 5% level, and those marked with one (*) are significant at the 10% level. The table shows that once the data are weighted by the inverse propensity score weight, differences between teen and older mother characteristics are eliminated or ‘balanced’.

Figure A1. Distribution of the estimated propensity scores by population group.

Notes: The figure presents the distribution of the propensity score for teen and older mothers for Africans and coloureds separately. The propensity score is the conditional probability that the child’s mother gave birth to them in her teens. The propensity score is calculated using a logit specification.

Footnotes

Support for this research was provided by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation/Population Reference Bureau Global Teams of Research Excellence in Population, Reproductive Health and Economic Development. Ardington acknowledges funding from National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center R01 TW008661-01. Leibbrandt acknowledges the Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation for funding his work as the NRF/DST Research Chair in Poverty and Inequality.

In this instance the children are siblings born to the same mother.

LeGrand and Mbacke (1993) investigate the association between maternal age at birth and children’s health using a panel of children born in the Sahel. They do not however control for maternal and household characteristics that precede the birth. Similarly, there are a number of studies (Cameron et al. 1996; Mukasa 1992; Ncayiyana and Ter Haar 1989; Boult and Cunningham 1993) that compare the birth weights of children born to teens versus older mothers within specific hospitals in South Africa. Results on whether children born to teens are at higher risk of low birthweight are mixed and only the Ncayiyana and Ter Haar study matches mothers on socioeconomic status.

Additional detail and technical documentation are available on the CAPS web site, www.caps.uct.ac.za.

For instance, LeGrand and Mbacke (1993) find that first born children are exposed to greater health risks than their younger siblings although they are more likely to be vaccinated.

Note that birth information was not collected in wave 2.

Current weight and weight-for-height were also investigated, but the prevalence of underweight children or wasting (low weight-for-height) children was low. Only 13 children were defined as wasting.

One of the limitations of this test is that the order of the polynomial needs to be chosen. We follow Sanders et al. (2008) in the choice of a cubic specification in p(x).

In total five additional variables were included to balance the observables. These are the square of the numeracy and literacy test score, and interactions between poor and the test score, poor and the test score squared, highest grade at age 12 and the test score and poor and the community household income measure.

A similar figure, Figure A1 in the Appendix, illustrates that the common support condition is met when the propensity score is estimated for Africans and coloureds separately.

Note, regressions results were checked for robustness in the definition of a teen mother. Table B5 present the teen mother coefficient when the teen mother versus older mother group was restricted to 4, 5 and 6 year age intervals. No significant differences in the teen coefficient estimate are apparent.

Mother’s numeracy and literacy score, maternal grandparent’s education, wave 1 household income and an indicator that there were more than five books in the wave 1 household.

Contributor Information

Nicola Branson, Email: Nicola.branson@gmail.com, University of Cape Town, Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU), University of Cape Town, Private Bag, Rondebosch, 7701, Cape Town, South Africa, Telephone: +27-21-650-4344, Fax: +27-21-6505697.

Cally Ardington, Email: Cally.ardington@uct.ac.za, University of Cape Town.

Murray Leibbrandt, Email: Murray.leibbrandt@uct.ac.za, University of Cape Town.

References

- Ardington Cally, Menendez Alicia, Mutevedzi Tinofa. Early childbearing human capital attainment and mortality risk. Economic Development and Cultural Change. doi: 10.1086/678983. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angrist Joshua, Evans William. Schooling and labour market consequences of the 1970 state abortion reforms. Research in Labour Economics. 2000;18:75–113. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist Joshua D, Pischke Jorn-Steffen. Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press; Princeton New Jersey: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcraft Adam, Fernandez-Val Ivan, Lang Kevin. The Consequences of Teenage Childbearing: Consistent estimates when abortion makes miscarriage non-random. The Economic Journal. 2013:1–31. doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boult BE, Cunningham PW. Research Paper C28. University of Port Elizabeth; 1993. Some aspects of obstetrics in black teenage pregnancy: a comparative study of three age groups. [Google Scholar]

- Busso Matias, DiNardo John, McCrary Justin. IZA discussion paper no 3998. 2009. New Evidence on the finite sample properties of propensity score matching and reweighting estimators; pp. 1–30. Currently revise and resubmit, Review of Economics and Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron N, Richter L, McIntyre J, Dhlamini N, Garstang L. Unpublished report. University of the Witwatersrand; 1996. Progress report: Teenage Pregnancy and Birth Outcome in Soweto. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier Arnaud, Viitanen Tarja. The long-run labour market consequences of teenage motherhood in Britian. Journal of Population Economic. 2003;16(2):323–343. [Google Scholar]

- Currie Janet. Healthy wealthy and wise: socioeconomic status poor health in childhood and human capital development. Journal of Economic Literature. 2009;47(1):87–122. [Google Scholar]

- Crump Richard K, Joseph Hotz V, Imbens Guido W, Mitnik Oscar A. Dealing with limited overlap in estimation of average treatment effects. Biometrika. 2009;96(1):187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher Jason, Wolfe Barbara. Education and labour market consequences of teenage childbearing: Evidence using the timing if pregnancy outcomes and community fixed effects. Journal of Human Resources. 2009;44(2):303–325. [Google Scholar]

- Francesconi Marco. Adult outcomes for children of teenage mothers. Scandinavian Journal of Economics. 2008;110(1):93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus Arline. Black/White differences in the relationship of maternal age to birthweight: a population based test of the weathering hypothesis. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;42(4):589–597. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arline Geronimus, Korenman Sanders. Maternal youth or family background? On the health disadvantages of infants with teenage mothers. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1993;137(2):213–225. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronminus Arline, Korenman Sanders, Hillemeier Marianne. Does young maternal age adversely affect child development? Evidence from cousin comparisons in the United States. Population and Development Review. 1994;20(3):585–609. [Google Scholar]

- Hirano Keisuke, Imbens Guido W, Ridder Geert. Efficient estimation of average treatment effects using the estimated propensity score. Econometrica. 2003;71(4):1161–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth Sandra, Reid Lori. Early childbearing and children’s achievement and behavior over time. Perspectives in Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2002;34(1):41–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman Saul D. Teenage Childbearing Is Not So Bad After All...Or Is It? A Review of the New Literature. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30(5):236–239+243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotz Joseph, McElroy Susan Williams, Sanders Seth. The impacts of teenage childbearing on the mothers and the consequence of those impacts for government. In: Maynard RA, editor. Kids having kids: Economic costs and social consequences of teen pregnancy. Urban Institute; Washington DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hotz Joseph, Sanders Seth, McElroy Susan Williams. Teenage childbearing and its life cycle consequences: Exploiting a natural experiment. Journal of Human Resources. 2005;XL(3):683–715. [Google Scholar]

- Ichino Andrea, Mealli Fabrizia, Nannicini Tommaso. From temporary help jobs to permanent employment: What can we learn from matching estimators and their sensitivity? Journal of Applies Economics. 2008;23(3):305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Klepinger Daniel H, Lundberg Shelly, Plotnick Robert. Adolescent fertility and educational attainment of young women. Family Planning Perspectives. 1995;27(1):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepinger Daniel H, Lundberg Shelly, Plotnick Robert. How Does Adolescent Fertility Affect the Human Capital and Wages of Young Women? Journal of Human Resources. 1999;34(3):421–448. [Google Scholar]

- Knaul Felicia M. IDB working paper no 99. World Health Organization; Fundacion Mexicana para la Salud; 2001. Linking health nutrition and wages: the evolution of age at menarche and labor earnings among adult Mexican women. [Google Scholar]

- Lam David, Ardington Cally, Branson Nicola, Case Anne, Leibbrandt Murray, Menendez Alicia. The Cape Area Panel Study: Overview and Technical documentation for waves 1-2-3-4. [Accessed 24 June 2009];CAPS website. 2008 http://www.caps.uct.ac.za/documentation.html.

- Lam David, Marteleto Leticia, Ranchhod Vimal. Research Report 09-694. Population Studies Center, University of Michigan; 2009. Schooling and sexual behavior in South Africa: The role of peer effects. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Dohoon. The early socioeconomic effects of teenage childbearing: A propensity score matching approach. Demographic Research. 2010;23(25):697–736. [Google Scholar]

- LeGrand Thomas, Mbacke Cheikh SM. Teenage pregnancy and child health in the urban Sahel. Studies in Family Planning. 1993;24(3):137–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine Judith, Emery Clifton R, Pollack Harold. The well-being of children born to teen mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69(1):105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Levine David, Painter Gary. The schooling costs of teenage out-of-wedlock childbearing:analysis with a within-school propensity-score-matching estimator. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2003;85(4):884–900. [Google Scholar]

- Levine Judith, Pollack Harold, Comfort Maureen. Academic and Behavioral Outcomes Among the Children of Young Mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(1):355–369. [Google Scholar]

- Mukasa FM. Comparison of pregnancy and labour in teenagers and primigravidas aged 21–25 years in Transkei. South African Medical Journal. 1992;81(8):421–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nannicini Tommaso. Simulation-based sensitivity analysis for matching estimators. Stata Journal. 2007;73:334–350. [Google Scholar]

- Ncayiyana DJ, Ter Haar G. Pregnant adolescents in rural Transkei. South African Medical Journal. 1989;75:231–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panday S, Makiwane M, Ranchod C, Letsoalo T. Teenage pregnancy in South Africa - with a specific focus on school-going learners. Department of Basic Education, Child Youth Family and Social Development Human Sciences Research Council; Pretoria: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ranchhod Vimal, Branson Nicola, Lam David, Leibbrandt Murray, Marteleto Leticia. Working paper no 59. SALDRU, University of Cape Town; 2011. Estimating the effect of adolescent childbearing on educational attainment in Cape Town using a propensity score weighted regression. [Google Scholar]

- Ribar David C. Teenage fertility and high school completion. Review of Economics and Statistics. 1994;76(3):413–424. [Google Scholar]

- Robins James M, Rotnitzky Andrea, Zhao Lue Ping. Analysis of semiparametric regression models for repeated outcomes in the presence of missing data. Journal of American Statistics Association. 1995;90(429):106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum Paul, Rubin Donald. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrica. 1983;70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig Mark, Wolpin Kenneth. Sisters siblings and mothers: The effect of teen-age childbearing on birth outcomes in a dynamic family context. Econometrica. 1995;63(2):303–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]