Abstract

Factors developed during the routine storage of whole blood and packed red blood cells that primed the neutrophil (PMN) reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase significantly by 2 weeks of storage, with maximal priming activity by product outdate (2.5 to 3.7 fold). These agents appeared to be generated by cellular constituents because stored, acellular plasma did not demonstrate PMN priming. The priming activity was soluble in chloroform. Priming of the oxidase by plasma and plasma extracts was inhibited by WEB 2170, a platelet-activating factor (PAF) receptor antagonist. Separation of the chloroform-soluble compounds from plasma by normal phase high-performance liquid chromatography demonstrated two peaks of priming activity at the retention times of neutral lipids and lysophos-phatidylcholines (lyso-PCs) for both whole blood and packed red blood cells, Analysis of the latter peak of PMN priming by fast atom bombardment mass spectroscopy identified several specific lyso-PC species including C16 and C16 lyso-PAF. Further evaluation by gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy demonstrated that three of these species increased dramatically over product storage time, while the other two species increased modestly, and paralleled the Increase in priming activity. Commercially available, purified mixtures of these lyso-PCs primed the PMN oxidase by twofold. When PMNs were incubated with this mixture of lyso-PCs, acetylated analogs of these compounds rapidly accumulated. Thus lipids, including specific lyso-PC species, develop during routine storage of cellular blood components, prime PMNs, and possibly play a role in the severe complications of transfusion therapy.

Neutrophils play an important role in host defense against both bacterial and fungal pathogens.1,2 The microbicidal functions of PMNs are accomplished by sequestration of microorganisms into a phagolysosome and, in part, by generation of toxic oxygen metabolites whose production is initiated by an NADPH-oxidase.3,4 This enzyme has both cytosolic and membrane-associated components that assemble in the plasma membrane in response to a number of stimuli.5–7 With assembly and activation of the NADPH-oxidase, oxygen is consumed and reduced to superoxide anion .5–7 The production of can be enhanced by a process called priming.8–12 Priming agents by themselves do not activate the NADPH-oxidase; however, they increase both the rate and total amount of produced by PMNs in response to a subsequent stimulus.8–12 Bacterial endotoxin, recombinant interferon-gamma, and PAF are all well-known priming agents.8–12

PAF is defined chemically as 1-o-alkyl-2-o-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, with the alkyl group being predominantly hexadecyl.12,13 PAF rapidly primes the PMN oxidase in 1 to 5 minutes and enhances other PMN functions including adherence, chemotaxis, and degranulation.8,12 The cellular mechanisms of PAF priming of PMNs are associated with a rapid increase in the intracellular calcium ion concentration.13,14 PAF also activates protein kinase C in many cell lines, a process that may be involved with priming in PMNs.13,14 Membrane phospholipases, including phospholipases A2, C, and D, can be activated by PAF through its binding to a specific receptor linked to a G-protein and the pp60 src tyrosine kinase.14 A number of investigators have reported that PAF is produced in several different cell types including neutrophils, endothelial cells, monocytes, eosinophils, and platelets.13–17 PAF may also upregulate its own production in PMNs and many other types of cells.13,18 Functionally, PAF can be defined by biologic activities, which can be inhibited by specific PAF receptor antagonists like WEB 2170.18 Inactivation of PAF in the plasma is mediated by an acetylhydrolase.19 This plasma enzyme deacetylates PAF at the sn-2 carbon metabolizing PAF to an inactive form, lyso-PAF.19 Deficiencies in this enzyme system have been associated with the severity of PAF-induced disease, especially asthma.20

PAF has been implicated as a mediator of inflammation and is associated with a number of clinical syndromes including asthma, necrotizing enterocolitis, septic shock, anaphylaxis, and ARDS.18,20–25 Animal studies have demonstrated that administration of PAF receptor antagonists have ameliorated many of the PAF-induced clinical effects, especially in asthma and ARDS.25,26 However, the precise role that PAF plays in the normal immune response as well as in inflammatory disease states has not been completely elucidated.

This laboratory previously reported that stored blood components on the day of outdate, the last day in which blood components may be transfused, contained a PAF-like activity that primed PMNs through the PAF receptor.27 Although these compounds demonstrated PAF immunoreactivity, they were structurally distinct from PAF.28 The current studies describe the development of PMN priming activity during routine storage of WB and PRBCs, separate this activity into two distinct classes of lipids by HPLC, and identify and characterize one of these classes of lipids, lyso-PCs, as being partially responsible for the observed PMN priming activity. A mechanism by which the observed priming activity might occur is also explored.

METHODS

Materials

fMLP, PAF, cytochrome c, essentially fatty acid-free human albumin, superoxide dismutase, phospho-lipase C, stearoyl lyso-PC, palmitoyl lyso-PC, oleoyl lyso-PC, and C16 lyso-PAF were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo. 2H3-hexadecanoyl-lyso-PC and 2H4-hexadecyl-lyso-PC were obtained from Serdary, London, Ontario, Canada, and Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Mich., respectively. 3H-acetyl-PAF (tritiated PAF) was purchased from New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass. Plastic microplates manufactured by Nunc Inc. were purchased from Intermountain Scientific Inc., Bountiful, Utah. WEB 2170 was the gift of Boerhinger Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Ridgefield, Conn. Sterile couplers for blood components were obtained from Baxter Healthcare Corp., Deerfield, Ill. Octadecylsilyl extractor cartridges and silica solid phase extractor cartridges were purchased from Analytichem, Harbor City, Calif., and Supelco, Bellefonte, Pa., respectively. Lichrosorb 5 µm silica-packed 4.6 × 250 mm HPLC columns were obtained from Phenomenex, Torrance, Calif. Solvent delivery modules (model 110B) and a 421 HPLC controller were purchased from Beckman Instruments, San Ramon, Calif. A Flo-One/Beta HPLC online radioactivity monitor and a TSQ70 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer were obtained from Radiomatic Instruments and Chemical Co., Inc., Tampa, Fla., and Finnigan Mat, San Jose, Calif., respectively.

Sample preparation

Ten healthy adult volunteers donated one unit of whole blood after informed consent was obtained according to the Human Subjects Committee, University of Colorado School of Medicine. Approximately 450 ml of WB was added to 67 ml of anticoagulant preservative solution (citrate-phosphate-dextrose-adenine). Five units were left as WB and 5 units were separated by standard centrifugation techniques into components: PRBCs, platelets, and plasma. The 5 units of WB and PRBCs were stored at 4° C according to the American Association of Blood Banks standards. Samples, 35 to 50 ml, were obtained on the day of collection and weekly through sterile couplers by using sterile technique. The samples were centrifuged at 5000 g for 7 minutes to remove cells, followed by a second centrifugation step at 12,500 g for 5 minutes to remove acellular debris. Aliquots (1 ml) from each sample were stored at −70° C. Two units of fresh plasma, separated from WB by centrifugation, and three units of thawed, fresh-frozen plasma were stored for 4 to 6 weeks at 4° C. Initially and after 6 weeks of storage, samples were removed via sterile couplers, centrifuged at 12,500 g, aliquotted into 1 ml volumes, and stored at −70° C as described previously until various assays were completed.

Neutrophil isolation and oxidase priming

PMNs were isolated by dextran sedimentation, Ficoll Hypaque gradient centrifugation, and osmotic lysis of contaminating red cells, as previously described.29 The PMNs were resuspended in KRPD at a concentration of 2.5 × 107 cells/ml and were preincubated with 400 µmol/L WEB 2170 or buffer for 5 minutes at 37° C. Plasma from the stored components or buffer (control) was added to make the final concentration 10% (vol/vol), and the mixtures were incubated for an additional 5 minutes at 37° C. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 2100 g for 3 minutes and resuspended in KRPD at a concentration of 2.5 × 107 cells/ml. To individual wells of a microtiter plate, PMNs (3.75 × 105) with cytochrome c (80 µmol/L) and, in some wells, superoxide dismutase (15 µg/ml) were added to achieve a total reaction volume of 150 µl. All priming experiments for each plasma sample were completed at 37° C in duplicate with a separate superoxide dismutase control. The respiratory burst was initiated with the addition of 1 µmol/L fMLP. The maximal rate of production was measured as the superoxide dismutase–inhibitable reduction of cytochrome c at 550 nm of light in a microplate reader (Molecular Dynamics, Menlo Park, Calif.) with an extinction coefficient of 8.4 × 103 L/mole/min as determined for the 150 µ1 reaction volume.27 Each plasma sample was tested for the capacity to enhance the maximal rate of superoxide anion production in response to fMLP. Additionally, lipid extracts, HPLC fractions, and purified mixtures of lyso-PCs were tested for the capacity to prime the PMN oxidase. The volumes of the lipid extracts and the HPLC-separated fractions were kept identical to the original amount of plasma extracted to ensure that the concentrations were identical to those in the original plasma. All priming experiments were done so that the final concentration of lipids from plasma, lipid extracts, or HPLC-separated lipids was the same.

Lipid extractions

Lipids were extracted from plasma samples by using a 1:1:1 methanol-2.0% acetic acid:chloroform:water extraction solution.30 The samples were centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 minutes at 4° C to aid in separation of the phases. The chloroform-soluble phase was removed and dried. The dried lipids were solubilized in 1.25% essentially fatty acid–free human albumin in a volume identical to that of the plasma extracted for PMN priming experiments.

PAF acetylhydrolase assay

3H-acetyl-PAF was pipetted into polypropylene tubes, taken to dryness, and then redissolved in 400 µl PBS, pH 7.2, which contained 0.05% albumin. Plasma (10 µl) was then added, the tubes mixed well, and the reaction allowed to proceed for 10 minutes at room temperature. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 10µl of glacial acetic acid, and the contents of the tube were poured onto the top of a reverse-phase octadecylsilyl solid-phase extractor cartridge that had been previously washed with 5 ml of ethanol followed by 5 ml of water. The column eluate was collected. The column was further eluted with 1.0 ml of 0.05 mol/L sodium acetate and the total eluates counted. For controls, radiolabeled substrate was analyzed without enzyme, and the results were corrected for nonenzymatically produced radioactivity in the eluates.

Characterization of the priming activity

Plasma samples were extracted as described above. HPLC separation was completed by using a normal phase system developed for phospholipid class separation. HPLC was performed on a Phenomenex lichrosorb 5 µm silica, 4.6 × 250 mm columns with two Beckman 110B solvent delivery modules and a 421A controller with a Rheodyne injector. The solvent system used was a modification of the method of Rivnay31 and consisted of 47% solvent B (hexane/isopropanol/water, 30:40:7) in solvent A (hexane/isopropanol, 30:40) pumped isocratically at 1 ml/min for 5 minutes, then programmed to 100% B over 20 minutes. After 39 minutes, the flow was increased to 2 ml/min. HPLC effluent was monitored with a variable wavelength monitor set at 206 nm of light. Both tritium-labeled and unlabeled phospholipid standards were injected to establish retention times of the various phospholipid classes. A Radiomatic Flo-One/Beta HPLC online radioactivity monitor was used to detect tritium standards. The elution lasted 60 minutes, and fractions representing 2 minutes of flow were collected. The individual fractions were dried, resuspended in 1.25% fat-free albumin (at a volume identical to that of the original amount of plasma that was extracted) and then assayed for the ability to enhance PMN oxidase activity as described above.

Fast atom bombardment mass spectroscopy was performed on the second peak of PMN priming from normal phase HPLC to identify the priming agents.32 A small aliquot from the second peak of priming activity from normal phase HPLC was applied to a drop of glycerol or triethanolamine on the tip of a fast atom bombardment probe. This sample was then subjected to a beam of energetic xenon atoms and ions from an atom gun operated at 7 to 8 kV. The ionized molecules desorbed from the probe were mass-analyzed by a scanning Finnigan Mat TSQ70 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer from mass 200 through mass 900.

Lyso-PCs were quantitated from plasma samples derived from PRBCs weekly until outdate (6 weeks). Lyso-PCs were isolated from plasma samples by a modification of a procedure developed for isolation of PAF.33 Lipids were extracted from 1 ml of plasma by the addition of 4 ml of ethanol that contained the stable isotopically labeled internal standards 2H3-hexadecanoyl-lyso-PC and 2H3-hexadecyl-lyso-PC. After storage at −25° C for at least 1 hour for complete protein precipitation, the ethanolic suspension was centrifuged and the ethanol decanted. This ethanol was diluted to 50% with water and then applied to the top of an octadecylsilyl solid-phase extractor cartridge, washed with 5 ml of water, and washed again with 5 ml of a 1:1 ethanol: water solution. The lipids were then eluted from the reverse-phase cartridge onto the normal-phase cartridge with 5 ml of ethanol. The silica cartridge was then washed with ethanol to remove the less-polar lipids, and the more-polar lipids (primarily lyso-PCs and sphingomyelin) were eluted with methanol/water (4:1). This eluate was dried, cleaved by phospholipase C, derivatized with pentafluorbenzoyl-chloride, and then analyzed by negative ion chemical ionization GC/MS as previously described.34

Acetylation of lyso-PCs by Isolated neutrophlls

Human neutrophils were isolated by standard techniques and resuspended in KRPD containing 0.1% human albumin at a con-centration of 107 PMNs/ml. The isolated PMNs were incubated for 1, 3, 5, and 10 minutes with a mixture of purified lyso-PCs identical to the concentrations of these lipids found at outdate of stored PRBCs: 24 µmol/L palmitoyl lyso-PC, 11 µmol/L stearoyl lyso-PC, 8 µmol/L oleoyl lyso-PC, and 0.6 µmol/L C16 lyso-PAF. After incubation the PMNs were extracted and the accumulation of the acetylated species were measured as previously described.33,35 The reaction was stopped by the addition of four volumes of cold ethanol that contained the stable isotopically labeled internal standards. Isolation of the acetylated phosphocholines was accomplished by using a reverse-phase solid phase extractor, followed by a silicic acid solid-phase extractor. The phospholipids were hydrolyzed by phospholipase C and derivatized for GC/MS with pentafluorobenzoyl chloride.

Data analysis

The means, standard deviations, and standard error of the means were calculated for each experimental and control group by standard methods. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) among groups were measured by a paired analysis of variance for repeated measurements or an independent analysis of variance for comparison of independent groups, both followed by the Newman Keuls test for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Priming of the PMN NADPH-oxidase by plasma from blood components

Plasma from WB did not enhance the activity of the NADPH-oxidase in response to fMLP on the day of collection as compared with buffer control (Fig. 1, A). However, with storage, priming by the plasma samples appeared, becoming significant at 2 weeks of storage and maximal on the day of outdate. At week 5, the plasma from WB primed the NADPH-oxidase 2.5-fold. Plasma isolates from PRBCs exhibited results similar to those with WB. As with WB, the plasma from the day of collection did not prime the NADPH-oxidase as compared with buffer control (Fig. 1, B). Priming of the PMN oxidase became significant at 2 weeks of storage and was maximal on the day of outdate. At week 6, plasma isolates from PRBCs primed the NADPH-oxidase 3.7-fold.

Fig. 1.

Priming of the respiratory burst by plasma from stored WS (A) and PRBCs (B). The maximal rate of superoxide anion production in response to 1 µmol/L fMLP is plotted as a function of routine storage time of WB and PRBCs. Plasma isolated from WB (■) and PRBCs (●) from the weeks of storage shown was used as the priming agent of PMNs as compared with buffer controls (dashed lines). The points represent the mean of 5 units tested, with error bars representing the SEM. *Statistical significance (p < 0.05) as compared with buffer control.

To determine whether these priming agents were of plasma origin and unrelated to cellular blood components, similar priming experiments were completed with stored plasma. Both fresh plasma (2 units) and thawed fresh frozen plasma (3 units) were stored at 4° C for 4 to 6 weeks and were assayed for their ability to enhance the maximal rate of production in response to fMLP. PMNs incubated with stored fresh-frozen plasma did not demonstrate an enhancement of the fMLP-stimulated respiratory burst and were no different from paired, buffer controls: stored fresh-frozen plasma, 2.0 ± 1.0; buffer controls, 1.2 ± 0.3 (nmol/3.75 × 105 PMNs/min) (n = 4). Stored fresh plasma yielded similar results, Therefore, acellular plasma samples did not contain any PMN priming activity.

Inhibition of priming

The priming activity from both WB and PRBCs was inhibited by preincubation of isolated PMNs with WEB 2170, a specific PAF receptor antagonist. The priming from WB samples at all storage times was completely inhibited including on the day of outdate, 112% ± 7% (mean ± SEM), by WEB 2170 (400 µmol/L). The priming activity from PRBC plasma at 2 to 3 weeks of storage was also completely inhibited by WEB 2170. However, at 4 to 6 weeks of storage the PRBC plasma priming activity was inhibited 83% ± 6% by WEB 2170. Identical concentrations of WEB 2170 inhibited purified PAF (2 µmol/L) priming by 81% ± 4%.

Lipid extraction of plasma from stored components

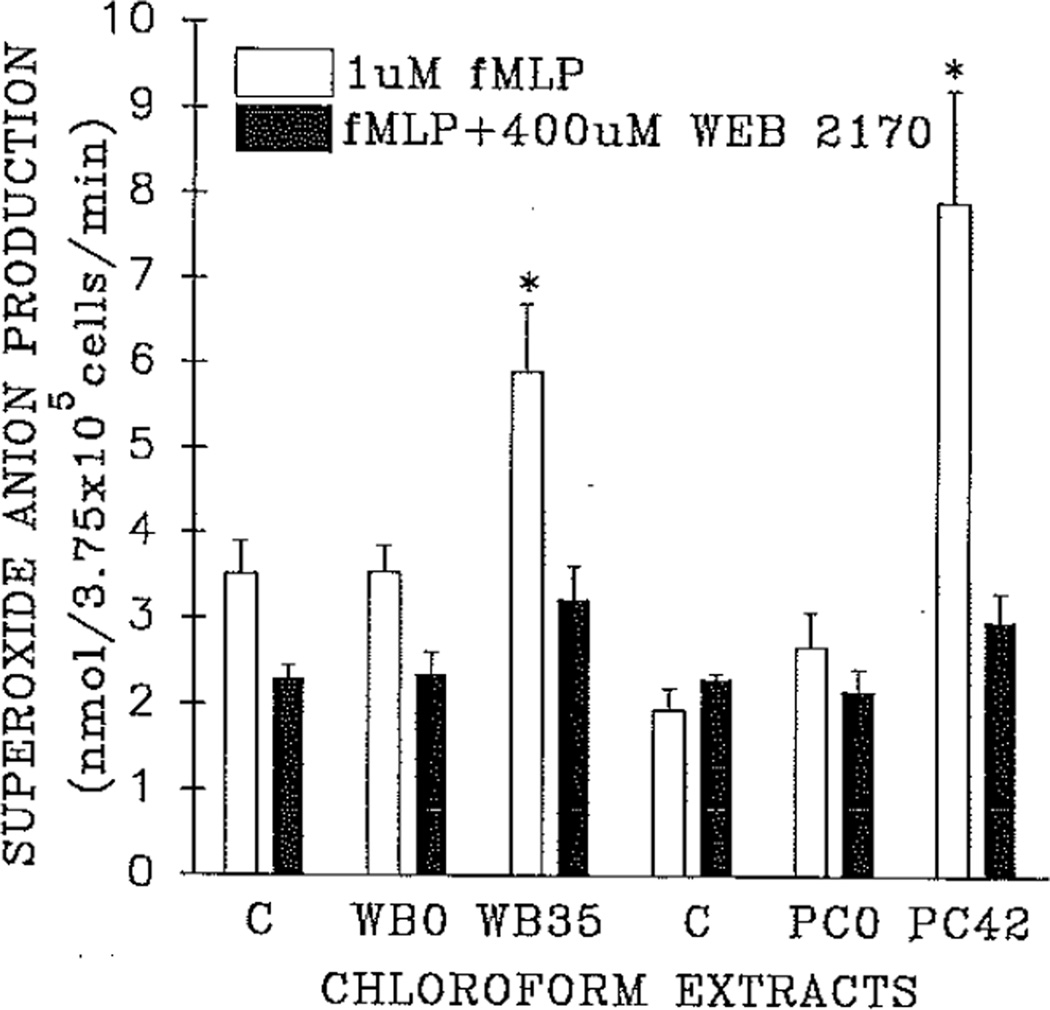

To further define the nature of this priming activity, extractions by the method of Bligh and Dyer were performed on each plasma sample, and the chloroform-soluble fractions were tested for the ability to prime the NADPH-oxidase, The priming activity was thought to be lipid in nature because of the short time needed to prime the PMN oxidase (5 minutes) and the inhibition by WEB 2170.8,13,18 Fig. 2 demonstrates the priming of the NADPH-oxidase by extracts of plasma from both stored WB and PRBCs on the day of collection, as compared with similar extracts from the same units on the day of outdate and compared with albumin-treated controls. The lipid extracts were resolubilized in 1.25% essentially fat-free albumin. Assays for WB were completed on separate days from PRBCs necessitating separate controls. As compared with controls, no priming activity was present in the extracts of the plasma samples from the day of PRBC collection. In contrast, significant chloroform-soluble priming activity was detected from the plasma samples obtained at product outdate, which primed the NADPH-oxidase 1.8-fold for WB and threefold for PRBCs as compared with buffer control or plasma extracts from the units on the day of collection (p < 0.05). The activity of these lipid extracts is comparable to the plasma priming activity: threefold versus 3.7-fold, PRBCs; 1.8-fold versus 2.5-fold, WB. The majority of the chloroform-soluble priming was inhibited by the PAF receptor antagonist WEB 2170 (400 µmol/L), 84% ± 7% for WB and 77 ± 2% for PRBCs.

Fig. 2.

Priming of the respiratory burst by plasma extracts. The maximal rate of superoxide anion production by isolated neutrophils in response to 1 µmol/L fMLP is presented for each extract: 1.25% essentially fat-free albumin (vehicle) paired control (C), extracted (chloroform-methanol) plasma from both WB and PRBCs on the day of isolation (WB0, PC0), extracted plasma from WB and PRBCs on the day of product outdate (WB35, PC42). The clear bars represent the mean of the maximal rate of superoxide anion production after 5 minutes’ incubation with the chloroform-soluble extracts of 5 units of both WB and PRBCs tested on both the day of product collection and the day of outdate, plus vehicle controls, with error bars representing the SEM. The solid bars represent identical neutrophils pretreated wish 400 µmol/L WEB 2170 to block the PAF receptor before incubation with albumin controls or the chloroform-soluble extracts. *Statistical significance (p < 0.05) as compared with both the paired vehicle control and extracted plasma from both PRBCs and WB on the day of product collection.

Quantitation of PAF acetylhydrolase

PAF acetylhydrolase is a plasma enzyme that inactivates PAF by deacetylation of the sn-2 carbon to lyso-PAF.19 To evaluate the possibility that decreased enzyme activity and subsequent accumulation of PAF or PAF derivatives could account for the previous results, PAF acetylhydrolase activity was measured in stored blood components on the day of component outdate. The activity of the PAF acetylhydrolase in the plasma samples from both stored WB and PRBCs ranged from 80% to 120% of normal human plasma activity. Thus the existence of the priming activity in stored blood components was not associated with diminished capacity to hydrolyze 1-o-alkyl-2-o-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphpcholine or its related structural derivatives.

Qualitative analysis of the lipid priming agent(s)

Previous results from this laboratory have demonstrated un-detectable levels of 1-o-alkyl-2-o-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PAF) in plasma samples from either stored WB or PRBCs by gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy.28 To partially characterize these priming agents, a well-defined HPLC system was used to separate lipids by phospholipid class.31 HPLC separation of lipids from pooled PRBC samples on the day of component outdate demonstrated two distinct peaks of priming activity (Fig. 3). Similar results were found for HPLC-separated lipid extractions of plasma from 3 units of WB analyzed individually on the day of outdate. Although the separation pattern presented in Fig. 3 was obtained after pooling samples from PRBC units, identical results were found in two PRBC units evaluated individually. The priming activity of both peak fractions was inhibited by 400 µmol/L WEB 2170 (results not shown). The early peak of lipid priming activity (peak A, Fig. 3.) was at the retention time when neutral lipids elute. This subclass of lipids would contain many biologically active compounds: diacylglycerols, triacylglycerols, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes, some of which are well-described PMN priming agents. The second peak of priming activity was at the retention time of lyso-PCs (peak B, Fig. 3). HPLC separation of lipids extracted from plasma from PRBCs on the day of product collection did not demonstrate any significant PMN priming activity.

Fig. 3.

The priming activity of plasma lipids on the day of outdate from pooled units of PRBCs separated by phospholipid classes by using normal phase HPLC, The bottom line demonstrates the separation of tritiated phospholipid standards. NL, Neutral lipids; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine; PI, phosphoinositol; PC, phosphatidylcholine; L-PC, lysophosphatidylcholine. PMN priming activity was found in the plasma from stored PRBCs on the day of outdate at (A) the retention time of neutral lipids (NL) and at (B) the retention time of lysophosphatidylcholines.

Lyso-PCs are thought to be inactive.13,19 The appearance of reproducible priming activity at this retention time was unexpected and indicated that this lipid priming was due to lyso-PCs or oxidized phosphatidylcholines that evidence a similar retention time. Because of the potential complexity of the lipid species in the first peak of priming activity and the possibility that lyso-PCs could be responsible for the priming activity in the second peak, we chose to analyze the latter peak. To characterize the latter peak of priming activity at the retention time of lyso-PCs, fast atom bombardment mass spectroscopy was performed on HPLC-separated lipids from pooled PRBC plasma on the day of outdate. Fast atom bombardment mass spectroscopy demonstrated that this peak contained a number of well defined lyso-PC species, including C16 lyso-PAF, C18 lyso-PAF, palmitoyl lyso-PC, oleyl lyso-PC, and stearoyl lyso-PC. Having identified the major constituents, quantitation of these species was accomplished by a GC/MS procedure (Table I).34 Analysis of the extracted lipids from pooled plasma samples throughout PRBC storage demonstrated marked increases in three of five lyso-PCs and modest increases in the other two species during storage. C16 lyso-PAF increased threefold, from 50 ng/ml to 150 ng/ml (Fig. 4, A). There was only a modest increase in the C18 lyso-PAF, from 50 ng/ml to 70 ng/ml. Two of three of 1-o-acyl lyso-PAF analogs increased over routine storage of PRBCs; we found a 1.5-fold increase in both of the palmitoyl lyso-PCs, from 9.8 to 15 µg/ml (Fig. 4, B), and a 1.5-fold increase in the stearoyl lyso-PC, from 2.18 to 3.33 µg/ml. The oleoyl lyso-PC changed only modestly over storage time, from 1.8 to 2.0 µg/ml, approximately 11%. Therefore, the second peak of priming contained a mixture of lyso-PCs, including lyso-PAF, whose concentration increased throughout storage time in parallel with the generation of the priming activity.

Table I.

The concentration of lysophosphatidylchollne species determined by quantitative GC/MS at the end of routine blood storage

| Species* | Chemical name | Concentration (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Hexadecyl | Lyso-PAF (C16) | 155 |

| Hexadecanoyl | Palmitoyl | 13,800 |

| Octadecyl | Lyso-PAF (C18) | 74 |

| Octadecanoyl | Stearoyl | 3,330 |

| Octadecenoyl | Oleoyl | 1,960 |

The species and chemical name refer to the 1-o-alkyl or 1-o-acyl side chains on the sn-1 carbon.

Fig. 4.

The concentration of lyso-PC in plasma from PRBCs as a function of routine storage time in weeks. The species name refers to the ether-linked side chains on the sn-1 carbon. A, The increase of the C16 lyso PAF concentration; B, the increase in the 1-o-palmitoyl lyso-PC concentration.

Priming of the PMN oxidase by a mixture of purified lyso-PCs

To verify that the second peak of priming activity from PRBCs was due to the compounds identified by GC/MS and quantitated by fast atom bombardment mass spectroscopy, purified, commercial preparations were solubilized in essentially fat-free human albumin and tested for their ability to prime the PMN oxidase as described. Lyso-PC mixtures, with final concentration being 10% of those concentrations presented in Table I, and containing 1-o-acyl derivatives of lyso-PAF, palmitoyl, oleyl, stearoyl, and C16 lyso-PAF, primed the maximal rate of production in response to fMLP (Table II). The majority of the priming activity was inhibited by 400 µmol/L WEB 2170.

Table II.

Priming of the neutrophil oxidase In response to fMLP by purified lysophosphatidylchollnes

| Priming agents | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stimuli/Inhibitors | Control | 10% Lyso-PCs |

| fMLP | 2.2 ± 0.5* | 4.3 ± 0.5† |

| fMLP + WEB 2170 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.5 |

Expressed as the maximal rate of superoxide anion production (nmol/3.75 × 105 PMNs/min) in response to 1 µmol/L fMLP. Identical PMNs were pretreated with 1.25% albumin (control) or 400 µmol/L WEB 2170 to block the PAF receptor. The concentration of the lyso-PCs, dissolved in 1.25% fat-free albumin, was 10% of the concentrations of lyso-PCs in Table I. Numbers represent the means and SEM of four experiments.

Statistically significant as compared with control (p < 0.05).

Acetylation of lyso-PC species by isolated neutrophils

Because lyso-PCs are thought to be inactive, we hypothesized that PMNs might rapidly acetylate a number of these lyso-PCs to active PAF and 1-o-acyl analogs that in turn could prime PMNs. To test this hypothesis, isolated PMNs were incubated with purified mixtures of the lyso-PCs, purchased commercially, at concentrations identical to those extracted from PRBC plasma samples on the day of outdate. The accumulation of acetylated phosphocholines from 107 PMNs was measured at various time points after exposure to this mixture of lyso-PCs. Very low amounts of acetylated phosphocholines were measured before incubation with the purified lyso-PCs. Significant quantities of hexadecyl (C16) PAF accumulated by 1 minute and were maximal by 10 minutes (Fig. 5, A). The accumulation of octadecyl (C18) PAF was similar (results not shown). Levels of 1-o-palmitoyl-2-o-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine increased rapidly to 30 times baseline in 1 minute. The 1-o-palmi-toyl-2-o-acetyl-sn-3-phosphocholine concentration became maximal at 3 minutes and decreased slightly by 10 minutes (Fig. 5, A). Isolated PMNs also produced a fivefold increase of 1-o-stearoyl-2-o-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine as compared with baseline levels in 1 minute, which became maximal at 3 minutes and decreased slightly at 10 minutes (Fig. 5, B), Additionally, l-o-oleyol-2-o-acetyl-sn-3-phosphocholine was also present but was not quantitated. Therefore, significant amounts of PAF and its 1-o-acyl analogs accumulated within 1 minute. The 1-o-acyl analogs reached maximal levels at 3 minutes, whereas the alkyl-PAF compounds were maximal at 10 minutes. The presence of these active compounds may explain the observed priming activity of the lyso-PCs and their inhibition by WEB 2170.

Fig. 5.

The accumulation of PAF and 1-o-acyl PAF analogs from 107 neutrophils incubated with purified mixtures of commercially obtained lysophosphatidylcholines and assayed at various times. The species name refers to the 1-o-alkyl or 1-o-acyl-linked side chain on the sn-1 carbon. Acetyiation of these compounds occurred on the sn-2 carbon. A, The accumulation of the 1-o-palmitoyl lyso-PC and C16 lyso-PAF. B, The accumulation of 1-o-stearoyl lyso-PC.

DISCUSSION

The studies presented in this article have demonstrated that during routine storage of WB and PRBCs, agents were generated that significantly primed the PMN NADPH oxidase after 2 weeks of storage and became maximal by outdate of the component. Although previous reports from this laboratory showed the presence of priming agents in outdated blood or a limited number of WB and PRBC units, careful evaluation of the accumulation of these compounds during storage has not been previously published and is of practical importance in planning strategies to avoid their biologic effects.27,28 The chloroform solubility of these agents defined them as lipids. Inhibition of this activity by a PAF receptor antagonist, WEB 2170, suggested that these compounds may prime PMNs through the PAF receptor.18,26,27 Previous data have demonstrated that none of these plasma samples from cellular blood components contained PAF by GC/MS.28 Furthermore, the presence of this priming activity in the face of normal levels of the PAF acetyl-hydrolase, which rapidly inactivates PAF, provided additional evidence that these priming lipids were not 1-o-alkyl-2-o-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (alkyl-PAF) or related compounds with an ether-linked acetyl group on the sn-2 carbon. Because fresh or stored acellular plasma did not significantly prime the oxidase, generation of these compounds required the presence of blood cells.

Further analysis of lipid extracts by normal phase HPLC demonstrated that two distinct lipid classes were responsible for the priming activity in WB and PRBCs: an early peak at the retention time of neutral lipids and a later peak at the retention time of lyso-PCs. In the normal phase HPLC system used, the early peak corresponded to a retention time when many lipid mediators elute, including, leukotrienes (LTB4), diacylglycerols, and other agents. Because of the likely complexity of the first peak of priming activity and the novel composition of the second peak, we focused our attention on identification of compounds in this latter peak of priming activity. Structural elucidation of the compounds in the second peak of priming activity showed that these compounds consisted of lyso-PCs, including lyso-PAF, in high concentrations. Three of five of these lyso-PCs increased over storage time in parallel with the generation of the priming activity, whereas the other two compounds demonstrated modest increases only. Although reported to be biologically inactive, lyso-PCs isolated from stored blood enhanced twofold the respiratory burst in response to fMLP. One mechanism through which PMN priming by these lyso-PCs might occur was presented in these studies. When incubated with isolated PMNs, significant amounts of PAF and active 1-o-acyl PAF analogs accumulated. The rapid accumulation of PAF and its 1-o-acyl analogs may have accounted for the observed priming activity and the inhibition by WEB 2170. A previous report demonstrating PMN aggregation in response to 1-o-palmitoyl-2-o-acetyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine, a 1-o-acyl PAF analog, and inhibition by WEB 2086 supports our findings.35 However, these data do not rule out the possibility that lyso-PCs primed PMNs directly, for recently 1-o-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, the predominant lyso-PC found in the second peak of priming activity, has been reported to directly activate the platelet thromboxane receptor.36 Moreover, lyso-PCs have also been shown to directly induce growth factor gene expression at the transcriptional level in human endothelial cells.37

The origin of the lipid priming activity in cellular components is not known. Previous reports from this laboratory have demonstrated that similar lipid priming agents were present in apheresis platelets collected by standard apheresis methods.38 These apheresis platelet concentrates have approximately 1 to 5 × 106 leukocytes per unit as compared with WB, PRBCs, and pooled random donor platelet concentrates that have approximately 108 to 109 leukocytes.38 Similar lipid priming agents were generated within 24 hours of routine storage in all apheresis platelet concentrates.39 These data suggested that leukocytes may not be the cells responsible for generation of these lipid priming agents.39 Further studies defining the origin of these priming agents are currently under investigation.

Although priming maximizes the processes involved with the microbicidal activity of PMNs, it may also results in deleterious effects related to excessive PMN function and tissue destruction.24,40 Such excessive PMN function is thought to play a role in ARDS, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and other syndromes resulting in end-organ damage and life-threatening effects on the host.24,40,44 In an animal model the development of ARDS required the administration of two PMN priming agents, lipopolysaccharide and PAF.40 Two agents or events may be necessary to precipitate this clinical syndrome. If a two-event theory is an appropriate model for ARDS in human beings, priming of PMNs may be the first insult that predisposes the host to acute lung injury.24,42 Activation of these adherent, primed PMNs by a second insult, such as the presence of other biologically active compounds associated with physiologic stress and infection or transfusion of significant lipid priming activity, could result in enhanced production of toxic oxygen metabolites, release of other cytotoxic agents, and tissue injury. Therefore, the infusion of compounds that prime PMNs may predispose patients to syndromes of excessive PMN activity including acute lung injury.

Adverse events during administration of blood or blood components occur in about 5% of all transfusions and include acute lung injury and other life-threatening reactions.43,44 TRALI has clinical and laboratory findings nearly identical to ARDS and has been associated with transfusion of leukoagglutinins.45 Although these immunoglobulins have been identified in most patients with TRALI presented in published series, the pathophysiology of this syndrome has not been completely elucidated, and in many cases, these antibodies cannot be detected,45 By virtue of their physiologic and biochemical effects, lipids that prime PMNs and are transfused with blood components may play a critical role in the events leading to TRALI and other complications of transfusion therapy. A retrospective study of 10 patients with TRALI compared with 10 patients with uncomplicated febrile or urticarial reactions demonstrated the presence of PMN priming agents in the TRALI patients’ serum, similar to those found in stored blood.46 We have demonstrated in the present studies that stored blood contained a significant amount of PMN priming activity in vitro, in part caused by high concentrations of lyso-PCs, These compounds have the potential to produce similar effects in vivo. The concentration of plasma from stored blood used in vitro (10%) roughly approximates the expected dilution of priming lipids when a patient receives the average postoperative transfusion (approximately 4 units of PRBCs). Thus it is plausible that the lipids, including lyso-PCs, infused during routine transfusions may reach concentrations in vivo that would prime recipient PMNs and predispose these individuals to TRALI. Given the complicated pathophysiology of capillary leak syndromes like TRALI, exposure to these biologically active lipids alone may not be sufficient to result in acute lung injury. Infusion of these lipids may result in only one of two events required to precipitate TRALI.

The identification of lipid compounds with the potential to mediate harmful reactions after the administration of blood products is the first step in understanding the pathophysiology of the adverse events of hemotherapy. Further studies to define the sites and processes of production and modification of biologically active lipid compounds during blood storage and their biologic effects on the transfused host are required to define their role in the pathophysiology of adverse events such as TRALI. This information can be used to develop strategies to modulate blood storage to avoid these serious complications or to effectively treat these disorders with selective agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Apheresis and Crossmatch units, Bonfils Memorial Blood Center, Denver, Colo., for whole blood collection and storage of components. We also thank Flo Usechek for help wish preparation of this manuscript.

Supported by the Margery Wilson Transfusion Medicine Fellowship, Bonfils Blood Center, The Bugher Physician Scientist Training Program, The Stacy Marie True Memorial Trust, and Grants K07-HL02036 and HL34303 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

adult respiratory distress syndrome

- C16 lyso-PAF

1-o-hexadecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- C18 lyso-PAF

1-o-octadecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- fMLP

formyl-met-leu-phe

- GC/MS

gas chromatography/mass spectroscope

- 3H-acetyl-PAF

1-o-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-3H-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- KRPD

Krebs-Ringer phosphate buffer; pH 7.4, with 2% dextrose

- lyso-PC

lysophosphatidylcholine

- NADPH-oxidase

reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate: O2 oxidoreductase

superoxide anion

- oleoyl lyso-PC

1-o-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- PAF

platelet-activating factor

- palmitoyl lyso-PC

1-o-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- PMN

neutrophil

- PRBCs

packed red blood cells

- stearoyl lyso-PC

1-o-stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphochollne

- TRALI

transfusion-related acute lung Injury

- WB

whole blood

Footnotes

Presented in part at the American Society for Hematology National Meeting, Dec. 4 through 8, 1992, Anaheim, Calif.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sbarra AJ, Karnovsky ML. The biochemical basis of phagocytosis. I. Metabolic changes during the ingestion of particles by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:1355–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babior BM, Kipnes RS, Curnutte JT. Biologic defense mechanisms. The production by leukocytes of superoxide, a potential bactericidal agent. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:741–744. doi: 10.1172/JCI107236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lew PD. Receptors and intracellular signaling in human neutrophils. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:S127–S131. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.3_Pt_2.S127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klebanoff SJ. Products of oxygen metabolism. In: Gallin JI, Goldstein IM, Snyderman R, editors. Inflammation: basic principles and clinical correlates. New York: Raven Press; 1988. pp. 391–444. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borregaard N, Heiple JM, Simons ER, Clark RA. Subcellular localization of the b cytochrome component of the human neutrophil microbicidal oxidase: translocation during activation. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:52–61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohno Y, Seligmann BE, Gallin JI. Cytochrome b translocation to human neutrophil plasma membranes and superoxide release. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:2409–2414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambruso DR, Bolscher BGJM, Stokman PM, Verhoeven AJ, Roos D. Assembly and activation of the NADPH: O2:oxidoreductase in human neutrophils after stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:924–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingraham LM, Coates TD, Allen JM, Higgins CP, Baehner RL, Boxer LA. Metabolic, membrane, and functional responses of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes to platelet activating factor. Blood. 1982;59:1259–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McPhail LC, Clayton CC, Synderman R. The NADPH oxidase of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes: Evidence for regulation by multiple signals. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:5768–5775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guthrie LA, McPhail LC, Henson PM, Johnston RB., Jr The priming of neutrophils for enhanced release of oxygen metabolites by bacterial lipopolysaccharide: evidence for increased activity of the superoxide producing enzyme. J Exp Med. 1984;160:1656–1671. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.6.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berton G, Zeni L, Cassatella MA, Rossi F. Gamma interferon is able to enhance the oxidative metabolism of human neutrophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;138:1276–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worthen GS, Seccombe JF, Clay K, Guthrie LA, Johnston RB., Jr The priming of neutrophils by lipopolysaccharide for production of intracellular platelet activating factor. J Immunol. 1988;140:3553–3559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, Mclntyre TM. Platelet activating factor. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17381–17384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shukla SD. Platelet-activating factor receptor and signal transduction mechanisms. FASEB J. 1992;6:2296–2301. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.6.1312046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sturk A, Schaap MCL, Prins A, ten Cate JW, van den Bosch H. Synthesis of platelet-activating factor by human blood platelets and leucocytes. Evidence against selective utilization of cellular ether-linked phospholipids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;993:148–156. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(89)90157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynch JM, Henson PM. The intracellular retention of newly synthesized platelet-activating factor. J Immunol. 1986;137:2653–2661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chignard M, Le Couedic JP, Tence M, Vargaftig BB, Benveniste J. The role of platelet activating factor in platelet aggregation. Nature. 1979;279:799–800. doi: 10.1038/279799a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heuer HO, Casals-Stenzel J, Muacevic G, Weber KH. Pharma-cologic activity of bepafant (WEB 2170), a new and selective hetrazapinoic antagonist of platelet activating factor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255:962–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stafforini DM, McIntyre TM, Carter ME, Prescott SM. Human plasma platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase. Association with lipoprotein particles and role in the degradation of platelet activating factor. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4215–4222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miwa M, Miyake T, Yamanaka T, et al. Characterization of serum platelet activating factor (PAF) acetylhydrolase. Correlation between deficiency of serum PAF acetylhydrolase and respiratory symptoms in asthmatic children. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:1983–1991. doi: 10.1172/JCI113818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caplan MS, Sun X-M, Hsueh W, Hageman JR. Role of platelet activating factor and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr. 1990;116:960–964. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80661-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crespo MS, Fernandez-Gallardo S. Pharmacological modulation of PAF: a therapeutic approach to endotoxin shock. J Lipid Mediators. 1991;4:127–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heuer HO. Effect of the hetrazepinoic platelet-activating factor antagonist bepafant (WEB 2170) in models of active and passive anaphylaxis in mice and guinea pigs. Lipids. 1991;26:1374–1380. doi: 10.1007/BF02536570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vercellotti GM, Yin HQ, Gustafson KS, Nelson RD, Jacob HS. Platelet activating factor primes neutrophil responses to agonists: role in promoting neutrophil-mediated endothelial damage. Blood. 1988;71:1100–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabinovici R, Esser KM, Lysko PG, et al. Priming by platelet-activating factor of endotoxin-induced lung injury and cardiovascular shock. Circ Res. 1991;69:12–25. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seeds EA, Klimus N, Coyle AJ, Page CP. The effect of the selective PAF antagonist WEB 2170 on PAF and antigen-induced bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophil infiltration. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;183:1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silliman CC, Thurman GW, Ambruso DR. Stored blood components contain agents that prime the neutrophil NADPH oxidase through the platelet activating receptor. Vox Sang. 1992;63:133–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1992.tb02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silliman CC, Johnson CA, Clay KL, Thurman GW, Ambruso DR. Compounds biologically similar to platelet activating factor are present in stored blood components. Lipids. 1993;28:415–418. doi: 10.1007/BF02535939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ambruso DR, Bentwood B, Henson PM, Johnston RB., Jr Oxidative metabolism of cord blood neutrophils: Relationship to content and degranulation of cytoplasmic granules. Pediatr Res. 1984;18:1148–1153. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198411000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bligh EA, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rivnay B. Combined analysis of phospholipids by high performance liquid chromatography and thin layer chromatography: analysis of phospholipid classes in commercial soybean lecithin. J Chromatogr. 1984;294:303–315. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chilton FH, Murphy RC. Characterization of the arachidonate-containing molecular species of phosphoglycerides in the human neutrophil. Prostaglandins Leukot Med. 1986;23:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0262-1746(86)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clay KL. Quantitation of platelet-activating factor by gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 1990;187:134–142. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)87018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christman BW, Gay JC, Christman JW, Prakash C, Blair IA. Analysis of effector cell-derived lyso platelet activating factor by electron capture negative ion mass spectroscopy. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1991;20:545–552. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200200907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clay KL, Johnson C, Worthen GS. Biosynthesis of platelet activating factor and 1-o-acyl analogues by endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1094:43–50. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(91)90024-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillipson DW, Tymiak AA, Tuttle JG, et al. Isolation and identification of lysophosphatidylcholines as endogenous modulators of thromboxane receptors. J Lipid Med. 1993;7:155–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kume N, Gimbrone MA., Jr Lysophosphatidylcholine transcriptionally induces growth factor gene expression in cultured human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:907–911. doi: 10.1172/JCI117047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lombardo JF, Cusack NA, Rajagopalan C, Sangaline RJ, Ambruso DR. Flow cytometric analysis of residual white blood cell contamination and platelet activation antigens in double filtered platelet concentrates. J Lab Clin Med. 1993;122:557–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silliman C, Thurman G, Ambruso D. Agents that prime the neutrophil (PMN) oxidase develop during routine storage of platelet concentrates. Blood. 1992;80:365a. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malech HL, Gallin JI. Neutrophils in human diseases. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:687–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709103171107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kubes P, Ibbotson G, Russell JM, Wallace JL, Granger DN. Role of platelet activating factor in ischemia/reperfusion-induced leukocyte adherence. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:G300–G305. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.2.G300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salzer WL, McCall CE. Primed stimulation of isolated perfused rabbit lung by endotoxin and platelet activating factor induces enhanced production of thromboxane and lung injury. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1135–1143. doi: 10.1172/JCI114545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker RH. Special report: transfusion risks. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;88:374–378. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/88.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Triulzi DJ, Heal JM, Blumberg N. In: Transfusion medicine in the 1990s. Nance SJ, editor. Arlington, Virginia: American Association of Blood Banks; 1990. pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Popovsky MA, Moore SB. Diagnostic and pathogenelic considerations in transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfusion. 1985;25:573–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25686071434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silliman C, Pitman J, Thurman G, Ambruso D. Neutrophil (PMN) priming agents develop in patients with transfusion related acute lung injury. Blood. 1992;80(suppl 1):261a. [Google Scholar]