Abstract

Unmet need for family planning is typically calculated for currently married women, but excluding husbands may provide misleading estimates of couples’ unmet need for family planning. This study builds on previous work and proposes a method of calculating couples’ unmet need for family planning based on spouses’ independent fertility intentions. Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) couple data from West Africa are used. Across the three countries, less than half of the couples with any unmet need had concordant unmet need (41.2-48.8%). A similar percentage of couples had wife-only unmet need (33.0-40.4%). A smaller percentage had husband-only unmet need (15.1-22.9%). Calculating unmet need based only on women's fertility intentions overestimates concordant unmet need. Additionally, that approximately 15-23% of couples have husband-only unmet need suggests that men could be an entry point for contraceptive use for some couples. To calculate husbands’ unmet need, population-based surveys should consider collecting the necessary data consistently.

Introduction

Unmet need for family planning is typically calculated only for currently married women, yet the findings are often assumed to hold for couples for the purposes of designing family planning programs (Bankole and Ezeh 1999). This assumption can be misleading since multiple studies have shown that husbands’ preferences are also important for couples’ reproductive behavior, including contraceptive use and subsequent fertility (Bankole 1995; Berrington 2004; DaVanzo et al., 2003; DeRose and Ezeh, 2005; Gipson and Hindin 2009; Miller and Pasta 1996; Thomson, McDonald and Bumpass 1990; Thomson 1997; Thomson and Hoem 1998; Samandari, Speizer and O'Connell 2010). Bankole and Ezeh (1999) argue that the traditional definition of unmet need, excluding husbands’ preferences, misrepresents the potential market for contraception. As a result, considering unmet need among both husbands and wives may provide important information to family planning programs (Ngom 1997; Bankole and Ezeh 1999).

Previous studies have focused on the extent to which discordance in husbands’ and wives’ fertility intentions accounts for unmet need, but evidence is mixed. Casterline et al. (1997) found that the husband's pronatalism was an important contributor to unmet need in the Philippines; 46% of non-contracepting women who wanted no more children had husbands who wanted to have another child, compared to only 23% of corresponding contracepting couples. While Casterline et al. found that the husband's pronatalism was associated with contraceptive non-use in the Philippines, a study of five Asian countries demonstrated that considering husband's fertility preferences accounted for less than 10% of women's unmet need (Mason and Smith 2000). However, Mason and Smith looked only at intention to limit childbearing and found that few couples had differing intentions on limiting in these countries. They suggest that in countries where there is greater discordance between husbands’ and wives’ fertility intentions, male pronatalism may have a greater effect on wives’ unmet need. In his paper on measurement of wanted fertility, Bongaarts (1990) touched on the importance of considering husbands’ fertility intentions. His data from Thailand demonstrated that while the percentage of women and men who wanted more children was similar, an analysis of couples identified disagreement in fertility preferences between spouses. In 10% of couples the wife wanted more children and the husband did not, while the husband wanted more children and the wife did not in 12% of couples. He concluded that wanted fertility based on couples’ fertility preferences could be higher or lower compared to measuring wanted fertility based solely on women's preferences, depending on how these disagreements were resolved.

Studies from both developed and developing countries have shown that husbands’ fertility preferences are associated with subsequent fertility (Bankole 1995; Berrington 2004; DaVanzo et al., 2003; DeRose and Ezeh, 2005; Gipson and Hindin 2009; Miller and Pasta 1996; Thomson, McDonald and Bumpass 1990; Thomson 1997; Thomson and Hoem 1998). DaVanzo et al. (2003) found that in Malaysia, time to birth of a subsequent child was shorter among couples in which only the husband wanted another child compared to couples in which only the wife wanted another child. In a study in southwestern Nigeria, 25% of couples in which only the husband wanted more children had a subsequent birth, and 23% of couples in which only the wife wanted more children had a subsequent birth (Bankole 1995). However, when stratified by parity, Bankole (1995) demonstrated that among low parity couples, the husband's fertility intentions were a stronger predictor of a subsequent birth, while the wife's fertility intentions were a stronger predictor among couples with five or more children, suggesting that the relative importance of each spouse's intentions varies by parity. A study in Ghana found that increases in men's education were associated with lower fertility intentions among both husbands and wives, and that the fertility decline in Ghana can be attributed more to decreases in husbands’ desired family size than to increases in women's autonomy (DeRose and Ezeh, 2005). A study in Mali and Burkina Faso found that men's fertility preferences are a stronger determinant of contraceptive use than women's preferences (Andro, Hertrich and Robertson, 2002). The authors conclude that women's preferences have a weaker association with contraceptive practice in the male-dominated Sahelian countries, compared to Ghana where demand for contraception is similar between husbands and wives (Andro, Hertrich and Robertson, 2002). These studies suggest that both husbands and wives are important decision-makers, and both individuals’ fertility preferences should be considered in measures such as unmet need, particularly in male-dominated countries that have barely begun the fertility transition, such as those in the Sahel.

The concept of couple's unmet need for family planning arose from the acknowledgment that husbands and wives often have different fertility preferences and that both individuals’ preferences impact upon family planning use and subsequent fertility. Bankole and Ezeh (1999) calculated couple's unmet need for spacing and for limiting separately. Couples were considered to have unmet need for spacing if both spouses wanted another child later or if one spouse wanted another child while the other did not, and they were not currently using contraception (Bankole and Ezeh 1999). Couples were considered to have an unmet need for limiting if both spouses did not want more children and were not using contraception (Bankole and Ezeh 1999). Becker (1999) proposed a method of calculating couple's unmet need that was at its minimum when couples both had unmet need and was at its maximum when either spouse had unmet need. Bankole and Ezeh (1999) used data from six African countries to demonstrate that including husbands’ preferences and contraceptive use in the calculation of unmet need results in an estimate of unmet need for family planning that is 19-66% lower than the estimate using the traditional definition of unmet need considering only women's fertility intentions. Though many studies have shown that overall, husbands have lower levels of unmet need than their wives (Bankole and Ezeh 1999; Ngom 1997; Yadav Singh and Goswami 2009; Becker 1999), evidence suggests that discordance in unmet need may be more nuanced. Short and Kiros (2002) found high levels of discordance in unmet need for limiting in Ethiopia; 63% of wives and 51% of husbands with an unmet need for limiting were married to a spouse who did not have an unmet need for limiting. Though wives’ unmet need for limiting was higher than men's, this finding highlights that it is not uncommon for husbands to have an unmet need when their wives do not.

Building on the work of Bankole and Ezeh (1999) and Becker (1999), the present study proposes a calculation of couple's unmet need based on the most current definition of unmet need used by the DHS (Bradley et al. 2012) and including spouses’ joint reports of current contraceptive use and fertility intentions. The proposed definition yields: wife-only unmet need, husband-only unmet need and couple (concordant) unmet need for spacing and limiting.

Data and Methods

Data

Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) couple data from three West African countries, Benin, Burkina Faso and Mali, were used for this analysis. The DHS is a household survey that provides a nationally representative sample of males and females of reproductive age. The Benin survey was conducted in 2006 (n=3,345 couples), Burkina Faso in 2003 (n=2,340 couples) and Mali in 2001 (n=2,191 couples). Response rates for the men's surveys ranged from 83.8% in Mali to 91.4% in Benin. Responses rates for the women's surveys were higher, ranging from 94.4% in Benin to 96.3% in Burkina Faso.

West Africa was selected as the setting for this study because the population growth rate and unmet need for contraception remain high (Cleland et al., 2006). In Benin, the total fertility rate (TFR) was 5.7, while only 17% of currently married women were using any contraceptive method (INSAE and Macro International Inc. 2007). Similarly, the TFR was 5.9 and only 13.8% were currently using contraception in Burkina Faso (INSD and ORC Macro 2004). In Mali, the TFR was 6.8, and only 8.1% of currently married women were currently using any contraceptive method (CPS/MS, DNSI and ORC Macro 2002). At the same time, unmet need for family planning ranges from 27.3% among currently married women in Benin (INSAE and Macro International Inc. 2007) to 29.8% in Burkina Faso (INSD and ORC Macro 2004). In these three countries, the proportion of married women with unmet need for spacing is higher than the proportion of those with unmet need for limiting (INSAE and Macro International Inc. 2007; INSD and ORC Macro 2004; CPS/MS, DNSI and ORC Macro 2002). Because addressing unmet need for limiting has a greater impact on fertility than addressing unmet need for spacing, it is estimated that meeting unmet need in West Africa would have a relatively small impact on fertility, reducing the TFR from 5.6 to 4.8 births per woman (Cleland et al., 2006). Because countries in West Africa are predominantly patriarchal, considering men's fertility intentions and unmet need for family planning in the context of the couple is important for understanding the potential impact of family planning programs to address unmet need and initiate the fertility transition in this region.

These three countries and survey years were selected specifically because they were the only DHS surveys from West Africa that included the questions needed to calculate couple's unmet need. All of the surveys from West Africa between 1998 and 2010 were reviewed, and significant variation was found in the male questionnaires across surveys, especially in the questions regarding fertility preferences and contraceptive use. In order to calculate couple's unmet need, we sought surveys that asked the same fertility preference and contraceptive use questions on the male and female questionnaires. These three surveys were the only available surveys from West Africa that met these criteria. The questions needed to perform these calculations are described in detail below.

Calculation of unmet need

We use the revised definition of unmet need for family planning as described by Bradley et al. (2012). The definition formalized and simplified the calculation based on consistently collected DHS data to facilitate cross-country comparisons. As in the original definition, unmet need is defined separately for pregnant and postpartum amenorrheic women and for women who are not pregnant or postpartum amenorrheic. Postpartum amenorrheic women were defined as women whose period has not returned since the birth of their last child, among those whose last child was born in the previous 23 months. The revised definition of unmet need defined infecundity as meeting any of the following criteria: 1) first married five or more years ago, had no children in past five years and never used contraception; 2) when asked if she wanted to have another child, said she can't get pregnant; 3) said she was menopausal or had a hysterectomy when asked when her last period was or when asked the reason she does not use contraception; 4) said she never menstruated when asked when her last period was; 5) said last period was six or more months ago and not currently postpartum amenorrheic, excluding women whose periods had not returned since the birth of a child born in the last five years (Bradley et al. 2012).

For a pregnant or postpartum amenorrheic woman who is not currently using contraception, unmet need was defined as her reporting that her current (for pregnant women) or last pregnancy (for postpartum amenorrheic women) was mistimed or unwanted, which differs from previous couples’ unmet need studies. Bankole and Ezeh (1999) did not consider pregnant and post-partum amenorrheic women to be at risk for unmet need, while Becker (1999) used only future pregnancy intentions for these groups. A fecund woman who was not pregnant or postpartum amenorrheic and not using contraception was considered to have unmet need if she reported that she wanted to wait at least two years before her next pregnancy, was undecided, or did not want any more children. Women who were infecund were not considered at risk for unmet need. A summary of the fertility intention questions used in the present study and a comparison to those used in Bankole and Ezeh (1999) and Becker (1999) can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of fertility intention questions used in the present study, Bankole and Ezeh (1999) and Becker (1999)

| Present Study | Bankole and Ezeh (1999) | Becker (1999) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of Assessment | Question | Base | Recode | Timing of Assessment* | Timing of Assessment* | |

| Wife Fertility Intentions | ||||||

| Currently pregnant | Retrospective | When you got pregnant, did you want to be pregnant then, later, or did you not want any (more) children? | Asked of currently pregnant women |

No unmet need •Wanted then •Wants within 2 years Unmet need for spacing •Wanted later •Wants after 2+ years •Wants but unsure of timing •Undecided Unmet need for limiting •Did not want at all •Wants no more |

Not included/not considered at risk for unmet need | Prospective |

| Post-partum amenorrheic | Retrospective | When you got pregnant with [LAST CHILD], did you want to be pregnant then, later, or did you not want any (more) children? | Asked of all women who have children | |||

| Fecund, not pregnant or post-partum amenorrheic | Prospective | Do you want to have a (another) child, or would you prefer not to have any (more) children? If she does want to have a (another child): How long from now would you want to wait before the birth of a (another) child? |

Asked of women who are not sterilized, their husbands are not sterilized, they are not pregnant or are unsure of whether they are pregnant | Prospective | ||

| Husband Fertility Intentions | ||||||

| Currently pregnant | Retrospective | When your wife became pregnant, did you want her to be pregnant then, later, or did you not want her to become pregnant? | Asked of men who report that their wives are currently pregnant |

No unmet need •Wanted then •Wants within 2 years Unmet need for spacing •Wanted later •Wants after 2+ years •Wants but unsure of timing •Undecided Unmet need for limiting •Did not want at all •Wants no more |

Not included/not considered at risk for unmet need | Prospective |

| Post-partum amenorrheic | Retrospective | When you were expecting your last child, did you want the child at that time, later, or did you not want any (more) children? | Asked of men who have more than one child | |||

| Fecund, not pregnant or post-partum amenorrheic | Prospective | Do you want to have a (another) child, or would you prefer not to have any (more) children? If he does want to have a (another child): How long from now would you want to wait before the birth of a (another) child? |

Asked of men who are not sterilized, whose wives are not sterilized and not pregnant or they are unsure of whether their wives are pregnant | Prospective | ||

Prospective fertility intentions in Bankole and Ezeh, 1999 and Becker, 1999 were measured using the same questions and recodes as in the present study.

Building on this revised definition of unmet need, in the current study we define and calculate unmet need separately for women, men and couples based on individual fertility intentions. The Bradley et al. (2012) definitions of infecundity and post-partum amenorrhea based on the wife's report were used in all three calculations, but the definition of current contraceptive use was revised in this study to include the husband's report of male-controlled contraceptive methods. Thus, couples were classified as currently using contraception if the wife reported any contraceptive use or if the husband reported current use of condoms or withdrawal, whether or not the wife gave a concordant response. The husband's report of male-controlled methods and the wife's report of female-controlled methods were used since the questions about current contraceptive use were phrased as whether you were currently doing anything to prevent pregnancy. Combining the husband and wife's report of current contraceptive use was also selected because previous studies have shown that husbands tend to over-report use of female-controlled methods (Becker and Costenbader 2001), and that women are less likely to report male methods (Ezeh and Mboup 1997; Ahmed et al. 1987). Apart from the definition of current contraceptive use, the wife's unmet need was calculated using the Bradley definition, as described above. The husband's unmet need was calculated similarly, except the husband's fertility intentions rather than the wife's were used.

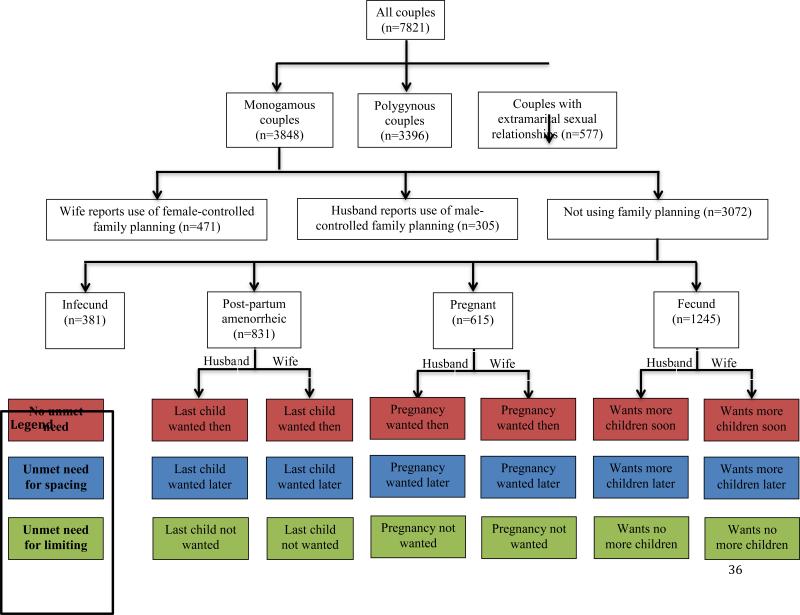

Couple's unmet need for family planning was defined in four mutually exclusive categories based on individual fertility intentions of the husband and wife: 1) both husband and wife have unmet need; 2) wife only has unmet need; 3) husband only has unmet need; and 4) neither spouse has unmet need (Figure 1). Tables 2A and 2B present a comparison of the definitions of each component of the calculation of couples’ unmet need and the definition of couples’ unmet need used in the present study, Bankole and Ezeh (1999) and Becker (1999).

Figure 1.

Classification of couple unmet need for family planning based on individual fertility intentions of the husband and wife

Table 2A.

Unmet need component definitions for the present study compared to Bankole and Ezeh (1999) and Becker (1999)

| Present Study | Bankole and Ezeh (1999) | Becker (1999) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Couples included in analysis | Monogamous couples | Monogamous and polygynous couples | Monogamous couples |

| Definition of family planning use | |||

| Current family planning use |

Any of the following •Wife reports current use of female-controlled methods (pills, IUD, injectables, diaphragm, female sterilization, periodic abstinence, implants, abstinence, lactational amenorrhea, string/“collier”) •Husband reports current use of male-controlled methods (condoms, withdrawal) |

Any of the following •Both husband and wife report current family planning use •Wife reports current use •Husband reports current use of traditional or male-controlled methods (condoms, withdrawal, vasectomy, periodic abstinence) |

Any of the following •Both wife and husband report current family planning use •Wife only reports current family planning use •Husband only reports current family planning use |

| Fecundity status | |||

| Infecund |

Any of the following •Wife reports that she was first married five or more years ago, had no children in past five years and never used contraception •When asked about future fertility intentions, wife reports that she is infecund •Wife reports menopause or a hysterectomy when asked about her last period or when asked the reason she does not use contraception •When asked about the date of her last period, wife reports she never menstruated •When asked about the date of her last menstrual period, wife reports it was ≥ 6 months ago and her last birth was ≥ 2 years ago |

Any of the following •Wife reports that she has not used contraception and had no pregnancies or births in the past 5 years and has not been classified as pregnant or amenorrheic •When asked about future fertility intentions, wife reports that she is infecund |

Any of the following •Wife reports infecundity •Husband reports infecundity |

| Post-partum amenorrheic | Wife reports that last birth was less than two years prior to the interview AND she has not had a period since before her last birth | Wife reporting post-partum amenorrhea ≤ the median duration of post-partum amenorrhea for women in the country | Not described |

| Pregnant | Wife reports that she is pregnant | Wife reports that she is pregnant | Not described |

| Fecund | Wife is not classified as currently pregnant, post-partum amenorrheic, or infecund based on the definitions above | Wife is not classified as currently pregnant, post-partum amenorrheic, or infecund based on the definitions above OR Wife reporting post-partum amenorrhea greater than the median duration of post-partum amenorrhea for women in the country |

Not described |

Table 2B.

Definition of couple unmet need for the present study compared to Bankole and Ezeh (1999) and Becker (1999)

| Present Study | Bankole and Ezeh (1999) | Becker (1999) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wife-only | Husband-only | Both | Wife-only | Husband-only | Both | ||

| Unmet need for spacing | Wife wants more children later and husband wants more children now | Husband wants more children later and wife wants more children now | Both wife and husband want more children later | Both wife and husband want more children later and couple is not currently using contraception OR One spouse wants more children soon or later and other spouse wants no more children and couple is not currently using contraception |

Husband reports current use, wife does not report current use, but wife wants to space or limit births and to use family planning within 12 months OR Both husband and wife report no current use, only wife wants to space or limit births and to use family planning within 12 months |

Wife reports current use, husband does not report current use, but husband wants to space or limit births and to use family planning within 12 months OR Both husband and wife report no current use, only husband wants to space or limit births and to use family planning within 12 months |

Both wife and husband report no current use and both want to space or limit births and to use family planning within 12 months |

| Unmet need for limiting | Wife wants no more children and husband wants more children now | Husband wants no more children and wife wants more children now | Both wife and husband want no more children | Both wife and husband want no more children and couple is not currently using contraception | |||

| No unmet need |

Any of the following •Couple is currently using family planning •Wife is infecund •Both husband and wife report that last child was wanted then among post-partum amenorrheic couples •Both husband and wife report that pregnancy was wanted then among currently pregnant couples •Both husband and wife report wanting more children soon among fecund couples |

Any of the following •Wife is infecund •Wife is post-partum amenorrheic based on definition above •Wife is pregnant •Both husband and wife want more children soon •One spouse wants more children soon and other wants more children later |

Any of the following •Infecund •Fecund but both husband and wife report current family planning use •Fecund and both husband and wife report no current family planning use and both report wanting to space or limit their births and both plan to use contraception within 12 months |

||||

Analyses

For each survey, husband and wife unmet need estimates from the couples’ sample were compared to unmet need estimates for the currently married women sample to approximate those typically calculated by DHS. The estimates for currently married women reported here differ from the published DHS estimates as they were based on the Bradley et al. (2012) definition of unmet need and were calculated only among monogamous individuals. The percent of currently married women, wives and husbands with unmet need for spacing, limiting and total unmet need were estimated. In addition, among couples in which either spouse had unmet need, the percentage of couples in each category of unmet need was calculated, including wife-only, husband-only, and concordant unmet need.

Couples in polygynous unions and in which either spouse reported an extramarital sexual relationship in the past 12 months were excluded from all analyses due to the inability to differentiate current contraceptive use and fertility intentions specific to any given wife. The percentage of couples excluded due to polygynous unions ranged from 41% in Mali to 48% in Burkina Faso. The percentage excluded due to extramarital sexual relationships ranged from 6% in Burkina Faso to 9% in Benin.

Missing data for fertility intentions was addressed in two ways. First, missing data were logically imputed where possible. For the men whose wives reported a current pregnancy, but he did not answer the question on whether the current pregnancy was wanted, either because he did not know that his wife was pregnant or due to errors in data collection or entry (n=138), the question regarding future fertility intentions was used to fill in his missing intentions. This assumes that his fertility intentions about the current pregnancy would be the same as his future intentions if he knew about the pregnancy or had been asked the question about his intentions regarding the current pregnancy. Also, for wives and husbands who had missing fertility intentions for a current pregnancy or for future intentions among fecund women, were not currently using contraception, and who had no living children (n=9), we assume that they wanted children now or had no unmet need. Finally, the question regarding the wantedness of the last child was asked of all men who had at least two children in these three DHS questionnaires, presumably because the assumption is that at least one child would be wanted. In the present study, this fertility intention question was used for the men in post-partum amenorrheic couples, and since men who had one child were not asked this question, these missing values were recoded to wanting the child then or no unmet need (n=43) to match the intent of the DHS questionnaire design. These are conservative assumptions, reducing the number of couples with unmet need for contraception. After these values were imputed, missing fertility intentions remained for 1.4% of the sample (n=55). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the effect of the missing values on the results. Couple unmet need was first estimated by imputing missing fertility intention data based on the value predicted by their spouse's fertility intentions. This approach was compared to dropping observations with missing fertility intentions from the sample, and the resulting proportion in each unmet need group was compared. A 1% difference between the two estimates for each category of couple unmet need was set as the a priori cutoff for a significant difference between the two approaches. The resulting estimates of couple unmet need were equivalent between the two approaches, and therefore the observations with missing fertility intention data were dropped from the analysis. All analyses were conducted on a final sample of 3,848 monogamous couples with complete fertility intention data: 1,630 from Benin, 1,073 from Burkina Faso and 1,145 from Mali.

Since the DHS does not create couple weights, the unmet need analysis was done using both the standard DHS women's weights and the men's weights and compared to the DHS estimates of unmet need. As could be expected, the women's weights provided unmet need estimates closest to the DHS estimates, and as a result, all analyses were conducted using the standard DHS women's weights for each country. All analyses were performed using Stata version 11.2 (StataCorp LP 2009).

Results

Compared to the estimates of unmet need for currently married monogamous women, estimates of unmet need among wives in the couples’ sample are very similar in Mali, but lower in Benin and Burkina Faso. Wives’ unmet need for spacing and limiting is lower in Benin and Burkina Faso compared to the estimates for currently married monogamous women (Table 3). Husbands’ unmet need is consistently lower than the estimates for currently married monogamous women and lower than the wives’ estimates across all three countries and types of unmet need. Husband and wife unmet need are most similar in Benin where there is a difference of 3.1 percentage points and greatest in Mali where there is a difference of 8.1 percentage points (Table 3). Across the three countries and among husbands and wives there is a greater unmet need for spacing than for limiting (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percent of currently married women, wives, husbands and concordant couples with unmet need for family planning, by category of unmet need and country

| Country |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse and unmet need category | Benin 2006 | Burkina Faso 2003 | Mali 2001 |

| Number of currently married women | (n=7,534) | (n=4,786) | (n=5,899) |

| Currently married women | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| No unmet need | 67.5 | 68.6 | 69.5 |

| Spacing | 22.4 | 24.5 | 23.6 |

| Limiting | 10.1 | 6.9 | 6.9 |

| Number of couples | (n=1,630) | (n=1,073) | (n=1,145) |

| Wives | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| No unmet need | 76.0 | 73.1 | 69.6 |

| Spacing | 16.1 | 21.1 | 23.6 |

| Limiting | 7.9 | 5.8 | 6.8 |

| Husbands | |||

| No unmet need | 79.1 | 79.7 | 77.7 |

| Spacing | 14.7 | 16.4 | 18.9 |

| Limiting | 6.2 | 3.9 | 3.4 |

Note: Weighted percentages are reported

Table 4 presents the distribution of couples by the unmet need classification of the husband and wife, including both couples with both concordant and discordant fertility intentions. Couples were classified as having concordant unmet need if they both had unmet need for spacing or limiting. Couples were classified as having discordant unmet need if only one spouse had unmet need either for spacing or limiting. Overall, more couples have only one spouse with unmet need (17.5% in Benin, 16.2% in Burkina Faso, 21.9% in Mali) compared to couples where both spouses have unmet need (13.8% in Benin, 15.5% in Burkina Faso, and 15.4% in Mali). Similar percentages of couples had concordant unmet need across the three countries. Among all couples, 7.2-10.2% both had unmet need for spacing, and 2.1-4.2% both had unmet need for limiting (Table 4). The percentage of wives who had unmet need for spacing but with husbands who had no unmet need ranged from 7.9% in Benin to 12.7% in Mali (Table 4). The percentage of husbands who had unmet need for spacing while their wives had no unmet need ranged from 4.5% in Burkina Faso to 6.5% in Mali (Table 4). The percentage of wives who had an unmet need for limiting while their husbands had no unmet need ranged from 1.6% in Burkina Faso to 2.4% in Benin, and even fewer husbands had an unmet need for limiting while their wives had no unmet need, ranging from 0.3% in Burkina Faso to 1.1% in Benin (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percent distribution of couples by category of unmet need for family planning, by country

| Country |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmet need of | Benin 2006 (n=1,630) | Burkina Faso 2003 (n=1,073) | Mali 2001 (n=1,145) | ||

| Spouse(s) with unmet need | Wife | Husband | |||

| All Couples | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Neither | |||||

| None | None | 68.8 | 68.3 | 62.7 | |

| One only | |||||

| Spacing | None | 7.9 | 9.8 | 12.7 | |

| Limiting | None | 2.4 | 1.6 | 2.3 | |

| None | Spacing | 6.1 | 4.5 | 6.5 | |

| None | Limiting | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| Both | |||||

| Spacing | Spacing | 7.2 | 9.8 | 10.2 | |

| Limiting | Limiting | 4.2 | 2.1 | 2.3 | |

| Limiting | Spacing | 1.4 | 2.1 | 2.2 | |

| Spacing | Limiting | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.7 | |

Note: Weighted percentages are reported

Couples with discordant unmet need can be further classified as having wife-only or husband-only unmet need (Table 5). Among couples in which either spouse had unmet need for family planning, less than half of the couples had concordant unmet need. The percentages with concordant unmet need ranged from 41.3% in Mali to 48.8% in Burkina Faso (Table 5). The percentage of couples with wife-only unmet need ranged from 33.0% in Benin to 40.4% in Mali (Table 5). A smaller percentage had husband-only unmet need, ranging from 15.1% in Burkina Faso to 22.9% in Benin (Table 5). This indicates that considering husbands’ unmet need identifies an additional 15-23% of couples in which at least one partner has an unmet need for family planning.

Table 5.

Percent of couples with unmet need who have wife-only, husband-only or concordant unmet need, by country

| Country |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmet need of | Benin 2006 (n=504) | Burkina Faso 2003 (n=328) | Mali 2001 (n=417) | ||

| Spouse(s) with unmet need | Wife | Husband | |||

| Either or both spouse unmet need | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Wife-only | |||||

| Spacing | None | 25.4 | 31.0 | 34.2 | |

| Limiting | None | 7.6 | 5.1 | 6.2 | |

| Husband only | |||||

| None | Spacing | 19.4 | 14.1 | 17.3 | |

| None | Limiting | 3.5 | 1.0 | 1.1 | |

| Both | |||||

| Spacing | Spacing | 23.2 | 30.8 | 27.4 | |

| Limiting | Limiting | 13.3 | 6.7 | 6.1 | |

| Limiting | Spacing | 4.5 | 6.6 | 5.9 | |

| Spacing | Limiting | 3.1 | 4.7 | 1.9 | |

Note: Weighted percentages are reported

The percentage of couples with concordant unmet need is greater among couples with more living children (Table 6). Total concordant unmet need among couples with zero to four living children ranged from 38.0% in Mali to 48.5% in Burkina Faso, while concordant unmet need among couples with five or more children ranged from 48.1% in Mali to 53.5% in Benin (Table 6). Among couples with zero to four living children, the percentage of couples in which both spouses have unmet need for spacing ranged from 29.6% in Benin to 37.8% in Burkina Faso, compared to 8.1% of couples in Benin and 15.5% in Burkina Faso with five or more living children (Table 6). Wife-only and husband-only unmet need for spacing was also higher among couples with zero to four living children compared to couples with five or more children. A similar pattern was observed for wife-only and husband-only unmet need for limiting among couples with five or more living children compared to couples with zero to four children. Among couples with five or more living children, the percentage of couples in which both spouses have unmet need for limiting ranged from 16.5% in Burkina Faso and Mali to 32.7% in Benin, compared to 1.0-5.1% among couples with zero to four children (Table 6).

Table 6.

Percent of couples with unmet need who have wife-only, husband-only or concordant unmet need, by country and number of living children

| Country |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmet need of | Benin 2006 (n=504) | Burkina Faso 2003 (n=328) | Mali 2001 (n=417) | ||||||||

|

Number of living children |

|||||||||||

| Spouse(s) with unmet need | Wife | Husband | 0-4 | 5+ | All | 0-4 | 5+ | All | 0-4 | 5+ | All |

| Either or both spouse unmet need | 70.1 | 29.9 | 100 | 68.8 | 31.2 | 100 | 67.4 | 32.6 | 100 | ||

| Wife-only | |||||||||||

| Spacing | None | 29.2 | 16.6 | 25.4 | 34.5 | 23.3 | 31.0 | 38.6 | 25.0 | 34.2 | |

| Limiting | None | 2.9 | 18.5 | 7.6 | 1.4 | 13.3 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 13.2 | 6.2 | |

| Husband-only | |||||||||||

| None | Spacing | 25.1 | 6.0 | 19.4 | 15.0 | 12.1 | 14.1 | 19.3 | 13.2 | 17.3 | |

| None | Limiting | 2.6 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 1.1 | |

| Total discordant unmet need | 59.8 | 46.7 | 55.9 | 51.5 | 50.5 | 51.2 | 62.0 | 52.9 | 58.8 | ||

| Both | |||||||||||

| Spacing | Spacing | 29.6 | 8.1 | 23.2 | 37.8 | 15.5 | 30.8 | 34.0 | 13.6 | 27.3 | |

| Limiting | Limiting | 5.1 | 32.7 | 13.3 | 2.2 | 16.5 | 6.7 | 1.0 | 16.5 | 6.1 | |

| Limiting | Spacing | 3.1 | 8.0 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 14.4 | 6.6 | 3.0 | 12.1 | 5.9 | |

| Spacing | Limiting | 2.4 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 5.4 | 3.1 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 1.9 | |

| Total concordant unmet need | 40.2 | 53.3 | 44.1 | 48.5 | 49.5 | 48.8 | 38.0 | 48.1 | 41.2 | ||

Note: Weighted percentages are reported

Concordance between the husband and wife's fertility intentions was an important predictor of both family planning practice and social support for family planning use. Among couples where both partners wanted to delay or limit childbearing, 33.2% were currently using family planning compared to 17.5% of couples in which only the wife and 19.9% of couples in which only the husband wanted to delay or limit childbearing across the three countries (data not shown). Concordant unmet need for spacing or limiting was associated with social support for women's family planning use. Across the three countries, 72.4% of husbands approved of family planning use among couples with concordant unmet need, compared to 67.5% among couples with wife-only unmet need and 65.5% among couples with husband-only unmet need (Table 7).

Table 7.

Percent of couples with unmet need who have wife-only, husband-only or concordant unmet need, by husband's approval of family planning use

| Husband's approval of family planning use |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse(s) with unmet need | Approves (n=840) | Disapproves (n=263) | Doesn't know (n=144) |

| Either or both spouse unmet need | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Wife-only | 67.5 | 20.9 | 11.6 |

| Husband-only | 65.5 | 27.4 | 7.1 |

| Both | 72.4 | 18.3 | 9.3 |

Note: Weighted percentages were calculated for each country survey, and these percentages were averaged across the three countries.

Discussion

Using only women's fertility intentions to calculate unmet need necessarily overestimates couples’ concordant unmet need for family planning (Bankole and Ezeh 1999; Becker 1999). Casterline and Sinding (2000) have argued that couple-level unmet need is not a useful concept unless it takes into account discordance in individual fertility intentions. Casterline and Sinding go on to say that “The comparison between preferences and behavior that lies at the heart of unmet need makes no sense for dyads in which one partner can have preferences that differ from the other partner's”. We disagree with this assessment of the usefulness of the concept of couple unmet need and would argue that because individuals negotiate and act upon their fertility intentions within the context of the couple, considering unmet need based solely on women's fertility intentions provides only part of the picture. We find evidence that across the three countries, women who are in couples where there is concordant unmet need would have greater social support for contraceptive use; among couples with concordant unmet need 72.4% of husbands approved of family planning use, compared to 67.5% among couples with wife-only unmet need. Greater social support among couples with concordant unmet need is important to overcome barriers to the initiation of family planning use, particularly in settings with patriarchal gender norms and low rates of contraceptive use such as West Africa.

In polygynous societies such as those in the Sahelian region, couple unmet need is difficult to measure with available data, but considering men in the calculation of unmet need for family planning is still important given the dominance of men's preferences in reproductive decision-making in these societies (Andro, Hertrich and Robertson, 2002). The present study focused on monogamous couples in the calculation of couple unmet need because DHS only collects men's overall fertility preferences rather than collecting fertility preferences with regard to each partner. A study in Senegal found higher fertility rates associated with higher wife rank after adjusting for age and number of wives, which suggests that husbands in polygynous unions may have differing fertility preferences with each wife (Lardoux and van de Walle 2003). However, it is also possible that men's fertility intentions are based on their desired number of children overall rather than intentions specific to each partner. If the DHS measured men's fertility preferences for each partner, we would be able to answer the question of whether men's fertility preferences differ by partner, and we would be able to use the DHS couples sample to calculate couple unmet need for both monogamous and polygynous couples. A couple-level measure of unmet need is important in settings such as West Africa because men have an impact on reproductive decision-making and fertility whether they are in monogamous or polygynous unions; the limiting factor is availability of data with which to measure couple unmet need for family planning among polygynous couples.

To address some of the concerns raised by Casterline and Sinding (2000), the present study takes into account discordance in fertility intentions and categorizes couples with unmet need into wife-only, husband-only or both (concordant) unmet need. We found that 31.3-37.3% of couples have at least one spouse who has unmet need, which is similar to the estimate based on currently married women in these countries. However, in the couples’ sample, concordant unmet need accounted for approximately half of the total unmet need, while discordant unmet need accounted for the other half. The discordant unmet need can be further broken down into 10-15% of couples who have wife-only unmet need and 5-7% of couples who have husband-only unmet need. In addition, concordance in unmet need between husbands and wives varied by parity. Both total concordant unmet need and concordant unmet need for limiting were greater among couples with five or more children. Concordant unmet need for spacing was greater among couples with zero to four children compared to those with five or more children.

Though family planning programs focus on meeting the needs of individual clients, it is important to acknowledge that most individuals’ preferences and behaviors exist within the context of a couple, and programmatic approaches could differ based on concordance of couple unmet need in the population. Voas (2003) argues that in societies where fertility is high and contraceptive prevalence is low, as in West Africa, couples who are not using family planning are likely to continue not using until the couple reaches an agreement on their intentions and acts to begin use of family planning. As a result, concordance in unmet need may provide information necessary for the success of family planning programs. Ngom (1997) suggests that in settings where overall unmet need is high and discordance between husband and wife unmet need is common, programs that promote spousal communication could result in large increases in contraceptive use. However, high levels of concordant unmet need in the population may also indicate a need for interventions promoting couple communication about family planning to spur action on couples’ shared preferences. Alternatively, high levels of discordant unmet need in the population may indicate the need for interventions such as behavior change communication campaigns that aim to reduce desired family size. These types of interventions may improve concordance in fertility intentions, which Voas (2003) suggests is often a prerequisite before couples can act on their preferences and use contraception effectively. As most available contraceptive methods are female-controlled, women can (and should) use contraception covertly if they wish, but contraceptive use is likely to be more effective, with a wider array of family planning options available and more support for contraceptive continuation, in couples in which men are involved in family planning use (Becker and Robinson 1998). The present study supports the hypothesis that concordance is more likely to allow couples to act on their preferences; current family planning use was significantly higher among couples in which both spouses wanted to delay or limit childbearing (33.2%), compared to couples in which only the husband (19.9%) or only the wife (17.5%) wanted to delay or limit childbearing.

The concept of concordance in unmet need is also important in that women in couples with concordant unmet need may have more method options available to them. Many family planning programs in developing countries require spousal consent for sterilization (Ross et al., 1993), and thus sterilization services could be in higher demand in contexts with a given level of concordant unmet need for limiting, compared to other contexts with the same level of unmet need for limiting, but for women only. In addition, women who wish to space their births but are concerned about health risks or side effects associated with hormonal methods of contraception need male cooperation to use nonhormonal methods such as condoms and the rhythm method or periodic abstinence. Conversely, where wife-only unmet need is common, clinicians might ask additional questions about agreement in spousal fertility intentions in order to understand whether the woman intends to use a method covertly. The woman's answers to these questions would help the clinician guide her to the most appropriate method.

In addition, the finding that 15-23% of couples with any unmet need have husband-only unmet need suggests that for some couples, men may be a potential entry point for contraceptive use. A study in Uganda found that couples typically use indirect forms of communication, which can lead both husbands and wives to overestimate their partner's desire for more children (Wolff, Blanc and Ssekamatte-Ssebuliba 2000). In couples where women's reported fertility desires are influenced primarily by their perception of their husbands’ desires, family planning programs might increase women's contraceptive uptake by engaging husbands. A study in Cambodia found that women who were nervous about discussing family planning with their husbands were less likely to use contraception compared to those who were not nervous about having these discussions (Samandari, Speizer and O'Connell 2010). These findings suggest that contraceptive programs and information, education and communication (IEC) activities should encourage couple communication so that ideally couples can make informed decisions about contraceptive use based on shared fertility intentions.

Though programs that aim to improve couple communication are often recommended to increase concordance in fertility intentions and promote contraceptive use, the success of these programs has been mixed and setting-specific. A randomized trial in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia found that women receiving family planning education through a home visitation program involving their husbands were more likely to be using contraception one year after the intervention compared to women receiving the same program without their husbands’ involvement (Terefe and Larson 1993). Similarly, a randomized controlled trial of a couples’ antenatal education program in Turkey found that women in the couples group were 1.49 times more likely than those in the control group to be using a family planning method four months post-partum (Turan et al., 2001). Though the results for post-partum family planning uptake in the couples’ group were positive, the authors reported that many men and women in the couples’ group did not attend the program sessions, and the authors suggest that in more conservative societies such as Turkey, separate groups for men and women may be more beneficial (Turan et al., 2001). Similar problems with reaching out to couples have been observed in sub-Saharan Africa. A randomized trial in Zambia found that when vouchers for contraceptive services were offered to couples, women were less likely to seek these services and more likely to become pregnant, compared to women who were offered vouchers for contraceptive services individually (Ashraf et al., 2013). However, the authors also found that women in the couples group were significantly happier and had better health compared to women in the individual group, which they interpret as indicating a psychosocial burden associated with covert contraceptive use (Ashraf et al., 2013). There is some evidence that family planning programs focusing on couples are beneficial in building a supportive environment for family planning use, but the setting should be taken into account to ensure that programs do not hinder women's access to family planning services.

While family planning programs have experienced challenges in male acceptance in settings with traditional gender norms, further involving men in culturally appropriate ways has been an important solution. In northern Ghana, though the Navrongo family planning program has increased contraceptive use and reduced total fertility, the program has also led to strained gender relations and increased gender-based violence as women's ability to independently regulate their fertility challenges conservative gender norms (Bawah et al., 1999). The Navrongo project has attempted to mitigate these negative effects through increased male involvement, including field workers who discuss the program with men and reaching out to men to provide information through village association meetings (Bawah et al., 1999). In settings where conservative, patriarchal gender norms prevail, interventions that promote couple communication may need to engage men and women separately to promote men's acceptance of family planning and protect women's privacy before couple-level interventions such as couples contraceptive counseling would be feasible.

Limitations

The results in this paper should be viewed in light of several limitations. Almost half of the couples in the sample from these three countries had to be excluded from the analysis because they were in polygynous relationships or had extramarital relationships. These couples were excluded because DHS does not collect men's fertility preference data for each partner, only overall fertility preferences. In addition, it is possible that men who are currently monogamous and included in our analysis intend to marry another woman in the future to fulfill their fertility intentions (Becker, 1999). If a currently monogamous man has completed childbearing with his wife but reports his fertility preferences including children to be born with future wives, this may underestimate his unmet need for contraception in his currently monogamous union.

Another limitation is that while there are important strengths in including men's report of male-controlled contraceptive methods, a weakness is that men may over-report use of male-controlled contraceptive methods due to social desirability bias. If men do over-report male-controlled methods, our definition would over-estimate current contraceptive use and underestimate unmet need. Additionally, this study relied on women's reports of fecundity in the calculation of couple unmet need, and it is possible that we are underestimating couple infecundity due to male causes, which account for 25-50% of infertility cases in developed countries (Palermo et al. 2014). If couples are not using contraception due to male infecundity, the present study may be overestimating couple unmet need.

Finally, a small percentage of missing data were logically imputed, and this could have led to misclassification of fertility intentions if the assumptions used were incorrect. For example, among husbands of pregnant women, our assumption was that a husband's future fertility intentions could be used as a proxy for his intentions regarding the current pregnancy when these data were missing. While this is likely to be accurate for men who were unaware that their wives were pregnant, the assumption may not hold for men who were aware of their wives’ pregnancies but had missing data due to data collector or data entry errors.

Conclusions

In order to calculate couple's unmet need using DHS data, it is important that the same questions be asked of both husbands and wives so that the unmet need concept for husbands has the same meaning as that for wives as presented in Table 1. For example, many surveys do not ask men whose wives are pregnant whether the current pregnancy was wanted now, later, or unwanted (as women are asked); rather men are asked only about their desire for another child after the current pregnancy. Another example is that women who are post-partum amenorrheic are asked whether their last child was mistimed or unwanted, while husbands of post-partum amenorrheic women are often only asked about their desire for additional children. This lack of symmetry in the questions asked of women and men makes the comparable calculation of unmet need for husbands and wives impossible. In addition, questions on men's fertility intentions and contraceptive use should be asked consistently across countries. While the three country surveys used for this study included the same questions to each partner, some of the questions on which the husband's unmet need are calculated are asked differently both between countries with DHS surveys and even across surveys within the same country. The same questions should be asked of men and women across surveys so that couple's unmet need can be assessed in a wider variety of settings using DHS data.

In addition to exploring unmet need in a wider array of developing country settings, future studies should explore methods for calculating couples’ unmet need in polygynous settings, building on the work of Bankole and Ezeh (1999). The DHS could improve researchers’ ability to explore this topic by systematically including questions about contraceptive use with each partner and fertility preferences with each partner among men in polygynous unions. Recent studies on involving men in family planning programs have provided useful information (Ashraf, 2013; Bawah et al., 1999; Samandari et al., 2010; Turan et al., 2001), but additional research is needed to understand how men can be most appropriately engaged by family planning programs to meet the needs of individual men and of couples.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sarah Bradley who shared detailed information on the revised definition of unmet need and helped ensure that we were able to match the revised DHS definition in our analyses.

References

- Ahmed Ghyasuddin, Schellstede William P., Williamson Nancy E. Underreporting of Contraceptive Use in Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1987;13(4):136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Andro Armelle, Hertrich Veronique, Robertson Glenn D. Demand for contraception in Sahelian countries: Are men's and women's expectations converging? Burkina Faso and Mali, compared to Ghana. Population. 2002;57(6):929–957. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf Nava, Field Erica, Lee Jean. Household bargaining and excess fertility: An experimental study in Zambia. 2013 Available at: < http://www.povertyactionlab.org/publication/household-bargaining-and-excess- fertility-experimental-study-zambia>.

- Bankole Akinrinola. Desired fertility and fertility behaviour among the Yoruba of Nigeria: A study of couple preferences and subsequent fertility. Population Studies. 1995;49(2):317–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bankole Akinrinola, Ezeh Alex C. Unmet need for couples: An analytical framework and evaluation with DHS data. Population Research and Policy Review. 1999;18(6):579–605. [Google Scholar]

- Bawah Ayaga Agula, Akweongo Patricia, Simmons Ruth, Phillips James F. Women's fears and men's anxieties: The impact of family planning on gender relations in Northern Ghana. Studies in Family Planning. 1999;30(1):54–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Stan. Measuring unmet need: Wives, husbands or couples? International Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;25(4):172–80. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Stan, Costenbader Elizabeth. Husbands' and wives' reports of contraceptive use. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32(2):111–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Stan, Courtland Robinson J. Reproductive health care: services oriented to couples. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1998;61(3):275–281. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(98)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrington Ann. Perpetual postponers? Women's, men's and couples' fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behaviour. Southampton Statistical Sciences Research Institute; Southampton, UK: 2004. p. 28. (S3RI Applications and Policy Working Papers, (A04/09)) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John. The measurement of wanted fertility. Population and Development Review. 1990;16(3):487–506. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Sarah EK, Croft Trevor N., Fishel Joy D., Westoff Charles F. DHS Analytical Studies No. 25. ICF International; Calverton, Maryland, USA: 2012. Revising Unmet Need for Family Planning. [Google Scholar]

- Casterline John B., Perez Aurora E., Biddlecom Ann E. Factors underlying unmet need for family planning in the Philippines. Studies in Family Planning. 1997;28(3):173–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casterline John B., Sinding Steven W. Unmet need for family planning in developing countries and implications for population policy. Population and Development Review. 2000;26(4):691–723. [Google Scholar]

- Cellule de Planification et de Statistique de Ministere de la Sante (CPS/MS), Direction Nationale de la Statistique et de l'Informatique (DNSI) and ORC Macro . Mali Demographic and Health Survey 2001. CPS/MS, DNSI and ORC Macro; Calverton, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland John, Bernstein Stan, Ezeh Alex, Faundes Anibal, Glasier Anna, Innis Jolene. Family planning: The unfinished agenda. The Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1810–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DaVanzo Julie, Peterson Christine E., Jones Nathan R. How well do desired fertility measures for wives and husbands predict subsequent fertility? Evidence from Malaysia. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 2003;18(4):5–24. [Google Scholar]

- DeRose Laurie F., Ezeh Alex. Men's influence on the onset and progress of fertility decline in Ghana, 1988-98. Population Studies. 2005;59(2):197–210. doi: 10.1080/00324720500099496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezeh Alex C., Mboup Gora. Estimates and explanations of gender differentials in contraceptive prevalence rates. Studies in Family Planning. 1997;28(2):104–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson Jessica D., Hindin Michelle J. The effect of husbands' and wives' fertility preferences on the likelihood of a subsequent pregnancy, Bangladesh 1998-2003. 2009 doi: 10.1080/00324720902859372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institut National de la Statistique et de l'Analyse Economique (INSAE) and Macro International Inc Benin Demographic and Health Survey 2006. Calverton, MD: Institut National de la Statistique et de l'Analyse Economique (INSAE) and Macro International Inc. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Institut National de la Statistique et de la Demographie (INSD) and ORC Macro . Burkina Faso Demographic and Health Survey 2003. INSD and ORC Macro; Calverton, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lardoux Solene, van de Walle Etienne. Polygyny and fertility in rural Senegal. Population. 2003;58(6):717–743. [Google Scholar]

- Mason Karen O., Smith Herbert L. Husbands' versus wives' fertility goals and use of contraception: The influence of gender context in five Asian countries. Demography. 2000;37(3):299–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Warren B., Pasta David J. Couple disagreement: Effects on formation and implementation of fertility decisions. Personal Relationships. 1996;3(3):307–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1996.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngom Pierre. Men's unmet need for family planning: Implications for African fertility transitions. Studies in Family Planning. 1997;28(3):192–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo Gianpiero D., Kocent Justin, Monahan Devin, Neri Queenie V., Rosenwaks Zev. Treatment of Male Infertility. In: Rosenwaks Zev, Wassarman Paul M., editors. Human Fertility: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press; New York: 2014. p. 386. [Google Scholar]

- Ross John A., Parker Mauldin W, Miller Vincent C. Family planning and population: A compendium of international statistics. The Population Council; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Samandari Ghazaleh, Speizer Ilene S., O'Connell Kathryn. The role of social support and parity on contraceptive use in Cambodia. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2010;36(3):122–31. doi: 10.1363/ipsrh.36.122.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short Susan E., Kiros Gebre-Egziabher. Husbands, wives, sons, and daughters: Fertility preferences and the demand for contraception in Ethiopia. Population Research and Policy Review. 2002;21(5):377–402. [Google Scholar]

- Terefe Almaz, Larson Charles P. Modern contraception use in Ethiopia: Does involving husbands make a difference? American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83(11):1567–1571. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.11.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Elizabeth, McDonald Elaine, Bumpass Larry L. Fertility desires and fertility: Hers, his and theirs. Demography. 1990;27(4):579–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Elizabeth. Couple childbearing desires, intentions and births. Demography. 1997;34(3):343–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Elizabeth, Hoem Jan M. Couple childbearing plans and births in Sweden. Demography. 1998;35(3):315–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan, Molzan Janet, Nalbant Hacer, Bulut Aysen, Sahip Yusuf. Including expectant fathers in antenatal education programmes in Istanbul, Turkey. Reproductive Health Maters. 2001;9(18):114–125. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(01)90098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas David. Conflicting preferences: A reason fertility tends to be too high or too low. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(4):627–646. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff Brent, Blanc Ann K., Ssekamatte-Ssebuliba John. The role of couple negotiation in unmet need for contraception and the decision to stop childbearing in Uganda. Studies in Family Planning. 2000;31(2):124–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2000.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav Kapil, Singh Bir, Goswami Kiran. Unmet family planning need: Differences and levels of agreement between husband-wife, Haryana, India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2009;34(3):188–91. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.55281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]