Abstract

The BCRP (ABCG2) transporter is responsible for the efflux of chemicals from the placenta to the maternal circulation. Inhibition of BCRP activity could enhance exposure of offspring to environmental chemicals leading to altered reproductive, endocrine, and metabolic development. The purpose of this study was to characterize environmental chemicals as potential substrates and inhibitors of the human placental BCRP transporter. The interaction of BCRP with a panel of environmental chemicals was assessed using the ATPase and inverted plasma membrane vesicle assays as well as a cell-based fluorescent substrate competition assay. Human HEK cells transfected with wild-type BCRP or the Q141K genetic variant, as well as BeWo placental cells that endogenously express BCRP were used to further test inhibitor and substrate interactions. To varying degrees, the eleven chemicals inhibited BCRP activity in activated ATPase membranes and inverted membrane vesicles. Further, genistein, zearalenone, and tributyltin increased the retention of the fluorescent BCRP substrate, Hoechst 33342, between 50–100% in BeWo cells. Additional experiments characterized the mycotoxin and environmental estrogen, zearalenone, as a novel substrate and inhibitor of BCRP in WT-BCRP and BeWo cells. Interestingly, the BCRP genetic variant Q141K exhibited reduced efflux of zearalenone compared to the wild-type protein. Taken together, screening assays and direct quantification experiments identified zearalenone as a novel human BCRP substrate. Additional in vivo studies are needed to directly determine whether placental BCRP prevents fetal exposure to zearalenone.

Keywords: BCRP, ABCG2, Q141K, BeWo, transporter, zearalenone, tributyltin, genistein, placenta

Introduction

The breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) is an efflux transporter highly expressed on the maternal surface of the placenta and is responsible for the fetal-to-maternal movement of chemicals such as bile acids and steroids1–3 and drugs including glyburide and nitrofurantoin.4–6 BCRP resides in the plasma membrane of placental syncytiotrophoblasts7 and translocates xenobiotics to the maternal circulation using energy generated from the hydrolysis of ATP. Interference of BCRP efflux activity in the placenta increases fetal xenobiotic accumulation4 and may enhance the risk of developmental adverse effects.

There is some evidence that dietary and environmental chemicals are substrates for BCRP. For example, the dietary soy isoflavone genistein that possesses estrogenic activity8 has been identified as a substrate of BCRP.9 The plasticizer bisphenol A and its glucuronide conjugate also interact with BCRP as substrates and/or inhibitors.10,11 The ability of BCRP to transport these chemicals may be important in understanding developmental toxicities that result from exposure during pregnancy. Prenatal administration of genistein or the mycotoxin zearalenone to pregnant mice alters mammary gland and reproductive development in female offspring.12 In addition, recent data suggest that in utero exposure of mice to bisphenol A is associated with glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, and ovarian cysts, in offspring.13–15 Taken together, these data suggest that BCRP-mediated transport in the placenta could be a protective mechanism that attempts to limit fetal exposure to environmental chemicals and prevent developmental toxicity.

There are a number of experimental approaches often used in drug discovery and development to assess the ability of chemicals to interact with the BCRP transporter as substrates and/or inhibitors.16 Screening assays include the ATPase activity assay and inverted plasma membrane vesicles, which can be conducted in multi-well plate formats.17–20 In both assays, the human BCRP gene (ABCG2) is overexpressed in Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells and the plasma membrane is isolated as fragments for the ATPase assay or inverted into membrane vesicles. Cell-based screening models include cultured cells that overexpress transfected BCRP or endogenously express BCRP. These assays employ the use of fluorescent BCRP substrates that can be monitored with flow cytometers or fluorescence cell counters.21,22 One advantage of BCRP-overexpressing cell lines is the ability to compare transport between the wild-type protein and the single nucleotide polymorphism Q141K (421C>A, rs2231142) in the absence of other drug transporters.23 The Q141K variant of BCRP exhibits reduced efflux of the diabetes drug glyburide24 and the cancer drug topotecan.23 Whereas BCRP-overexpressing cell lines offer the advantage of investigating BCRP function alone, it is equally important to utilize cells that endogenously express the complement of transporters normally found in a tissue. In particular, human choriocarcinoma cell lines, such as BeWo cells, recapitulate first trimester syncytiotrophoblasts and express the BCRP protein as well as other uptake and efflux transporters.25 As a result, BeWo cells are routinely used to assess placental transport.25,26 Although BeWo cells are a cancer cell line, they exhibit a number of features of placental trophoblasts including the ability to syncytialize into multinucleated cells and secrete hormones such as human chorionic gonadotropin.27

In order to further characterize the ability of placental BCRP to reduce fetal concentrations of environmental chemicals, a combination of in vitro screening and cell accumulation studies are needed. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to 1) screen eleven environmental chemicals as potential BCRP substrates and/or inhibitors using assays often employed in drug discovery and development and 2) quantify the direct transport of the mycotoxin zearalenone as a novel BCRP substrate in BeWo placental cells and cells overexpressing the wild-type or the Q141K variant BCRP gene. The eleven chemicals screened included the phytoestrogen genistein, mycotoxin zearalenone, plasticizer bisphenol A, insecticide methoxychlor, biocide tributyltin, arcaricide propargite, and the fungicides myclobutanil, prochloraz, propiconazole, tebucanzole, as well as epoxiconazole. A number of these xenobiotics have been reported to adversely impact the endocrine, reproductive, and neurological development of animals (Table 1)12,15,28–30 Therefore, the current evaluation of their interaction with the placental BCRP transporter aimed to advance our understanding of mechanisms that may regulate fetal exposure to environmental chemicals.

Table 1.

Examples of Adverse Developmental Effects of Environmental Chemicals1

| Environmental Chemical | Organ System | Species | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genistein | Mammary Gland and Reproductive System | Rats | 15 |

| Bisphenol A | Mammary Gland and Reproductive System | Mice | 12,13,44 |

| Zearalenone | Mammary Gland and Reproductive System | Mice, Rats | 15,44 |

| Methoxychlor | Neurological and Reproductive System | Mice, Rats | 30,55 |

| Myclobutanil | Reproductive System | Rats | 56,57 |

| Prochloraz | Mammary Gland and Reproductive System | Rats | 28,58 |

| Tributyltin | Adiposity and Reproductive System | Mice | 59,60 |

| Propiconazole | Reproductive System | Rats | 56,57 |

| Tebuconazole | Mammary Gland and Reproductive System | Rats | 28 |

| Epoxiconazole | Mammary Gland and Reproductive System | Rats | 28 |

The timing of developmental exposure (such as prenatal, perinatal, etc) varied between studies. In addition, some studies were conducted as mixtures. It should be noted that there has been little investigation of adverse effects in offspring following exposure to propargite during development.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Unless specified, all chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Human BCRP ATPase Assay

In the ATPase assay, substrates can be identified by the liberation of inorganic phosphate from ATP. BCRP-expressing plasma membranes were purchased from Xenotech (Lenexa, KS). The ATPase assay was used to quantify the activation and inhibition of transporter-dependent ATPase activity by environmental chemicals according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Activation. To determine activation, plasma membranes (4 μg) from Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells transfected with human BCRP were incubated at 37°C in 96-well plates with assay medium, 2 mM ATP, and environmental chemicals (0.01–100 μM) in the presence and absence of 500 μM sodium orthovanadate for 30 min. Sodium orthovanadate inhibits the ATPase function of ATP-binding cassette transporters and was used to calculate vanadate-sensitive activity by subtraction from the total ATPase activity. Inhibition. Inhibition was analyzed in a similar manner, with the addition of a specific activator of BCRP activity (sulfasalazine, 10 μM) to the assay medium. The BCRP inhibitor Ko143 (0.01–30 μM) was used as a positive control for antagonist activity. Following incubation of membranes at 37°C with a colorimetric reagent, liberation of inorganic phosphate was quantified by absorption at 610 nm. Samples were run in triplicate.

Human BCRP Membrane Vesicles

Control and human BCRP plasma membrane vesicles (5 mg/ml, 500 μl) were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Vesicles were generated from the plasma membranes of Sf9 insect cells infected with a baculovirus expressing the human BCRP gene, ABCG2. ATP-dependent transport of Lucifer yellow (50 μM) over a 2-min period at 37°C was used to quantify BCRP activity of membrane vesicles (20 μg) in the presence of environmental chemicals (0.01–100 μM) or Ko143 (0.01–10 μM) in reaction buffer (50 mM MOPS-Tris, 70 mM KCl, 7.5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.0) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Control vesicles (no transporter) and no MgATP incubations were used as negative controls to account for background diffusion of Lucifer yellow into vesicles. Reactions were terminated with ice-cold stopping buffer (40 mM MOPS-Tris, 70 mM KCl, pH 7.0) and vesicles were washed in a 96-well filter plate using vacuum filtration (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Vesicles were solubilized by addition of 50% methanol for 15 min at room temperature and vesicle contents were filtered through to a new 96-well plate. Lucifer yellow fluorescence was read at an excitation wavelength of 430 nm and emission wavelength of 538 nm. Samples were run in triplicate or quadruplicate.

Cell Culture

Human embryonic kidney-293 (HEK) cells expressing empty vector (EV), human wild-type (WT) BCRP, or the Q141K BCRP variant were kindly provided by Dr. Robert Robey (National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Life Technologies) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies). Human BeWo choriocarcinoma placenta cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium F-12 (ATCC) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies). Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and used in experiments at 80 to 90% confluence.

Western Blot

BeWo and HEK cells were lysed and protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Western blot analysis was performed by using 5 μg protein homogenate on SDS-polyacrylamide 4–12% Bis–Tris gels (Life Technologies) that were resolved by electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred from gels onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes using a 7-min iBlot (Life Technologies). Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dairy milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.5% Tween-20 overnight. BCRP (BXP-53, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), GAPDH (ab9485, Abcam), and β-Actin (ab8227, Abcam) primary antibodies were diluted in 2% non-fat dairy milk in PBS with 0.5% Tween-20 and incubated with the membranes at dilutions of 1:5000 (BCRP) and 1:2000 (GAPDH and β-Actin). Blots were further probed using species-specific HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO): antirat IgG (BCRP) and antirabbit IgG (GAPDH and β-Actin) at dilutions of 1:2000. Following which SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) was added to the blots for 2 min. Detection and semiquantitation of protein bands were performed with a FluorChem imager (ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA). The density of bands were assessed by the Alpha Viewer (ProteinSimple) and normalized to β-Actin or GAPDH levels.

Fluorescent Substrate Transport Assay

Transporter function was quantitated using a fluorescent cell counter and the BCRP substrate Hoechst 33342 as previously described.21,31 Environmental chemicals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (final concentration was less than 0.5%). Cells were then centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 5°C, resuspended, and loaded with the fluorescent BCRP substrate Hoechst 33342 (HEK cells: 7 μM, BeWo cells: 15 μM) with or without the BCRP inhibitor Ko143 (1 μM) or select environmental chemicals (genistein, zearalenone, tributylin, methoxychlor, and bisphenol A, 1–100 μM) for 30 min at 37°C and 5% CO2 (uptake period). Cells were then washed with cold medium, centrifuged, resuspended, and incubated in substrate-free medium in the presence and absence of test chemicals or Ko143 inhibitor for 1 h (efflux period). Cells were then washed, resuspended in cold PBS, and fluorescence was quantified using the Nexcelom Cellometer Vision (Nexcelom Bioscience LLC, Lawrence, MA). Twenty microliters of cell suspension was applied to the cell counting chamber, and each sample was analyzed using the bright-field images for cell size and cell number. The fluorescent intensity of each cell was subsequently analyzed with the appropriate filter VB-450-302 (Hoechst 33342; excitation/emission: 375/450 nm). For experiments using BeWo cells, raw fluorescence intensity for each cell was normalized to cell size to account for differences in cell size. The average fluorescence for each sample was determined and this experiment was performed in triplicate or quadruplicate.

alamarBlue Assay

The alamarBlue assay was used to assess cell viability based on the reduction potential of metabolically active cells (Life Technologies). Cells were seeded in black clear-bottom 96-well plates and exposed to different concentrations of zearalenone (2 to 100 μM) or the known BCRP substrate mitoxantrone (0.1 to 10 μM). After 72 h, 100 μL of alamarBlue® reagent was added to each well and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. The fluorescence was measured at 570 nm excitation and 585 nm emission wavelengths. Samples were run in quadruplicate.

ELISA Assay

BeWo and HEK cells were cultured in 6-well plates and remained adherent during zearalenone (10 or 50 μM) uptake (30 min) and efflux (1 h) phases. Cells were washed with PBS between phases as well as after the efflux phase and subsequently lysed with lysis buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, 150mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail). Zearalenone concentrations in cell lysates were quantified using an ELISA kit (Abnova, Taiwan). Zearalenone standards or sample were added to a 96-well plate coated with zearalenone antibody for 40 min. Then, the zearalenone-alkaline phosphatase conjugate was added to compete for binding with zearalenone. After incubation and washing, the p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate was added for 20 min followed by 3N NaOH, which was used as a stop solution. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm. Intracellular zearalenone concentrations were extrapolated from the standard curve and normalized to protein concentration. This experiment was performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SE. LC50 and IC50 values were calculated using non-linear regression curve fitting analysis (log (inhibitor) vs. response - variable slope with three or four parameters) using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls post-hoc test to compare 3 or more groups or an unpaired Student’s t-test to compare 2 groups. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Inhibition and Activation of BCRP ATPase Activity

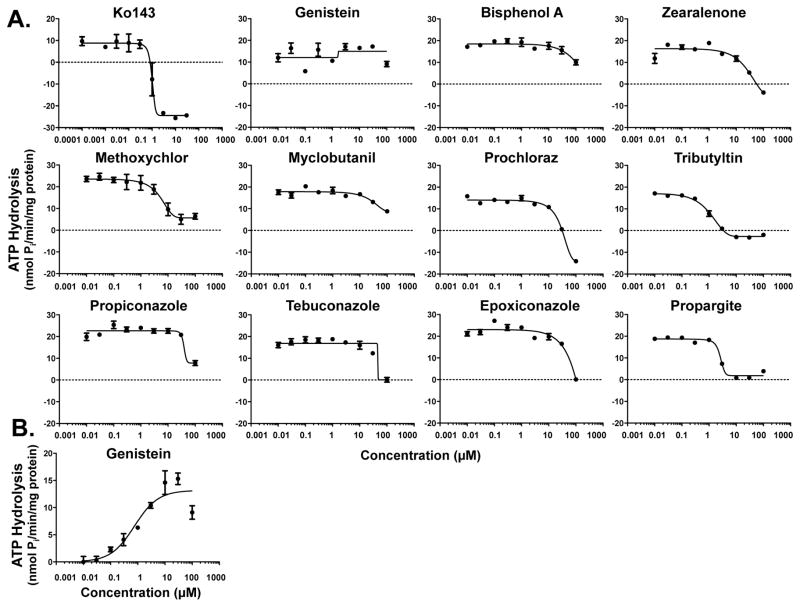

Plasma membranes expressing human BCRP were used to indirectly test whether environmental chemicals can interact with BCRP by quantifying the liberation of inorganic phosphate following ATP hydrolysis. Sulfasalazine and Ko143 were used as a prototypical activator and inhibitor of BCRP ATPase activity, respectively. Ko143 inhibited sulfasalazine-mediated BCRP activation with an IC50 value of 1 μM. Ten of the eleven chemicals decreased BCRP-mediated ATPase activity to some extent, while no change in ATPase activity was detected in the presence of genistein (Fig. 1). Based on inhibition of ATPase activity, the most potent inhibitors of BCRP were tributyltin, propargite, and methoxychlor followed by zearalenone, prochloraz, and propiconazole (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Of the eleven environmental chemicals screened for interaction with BCRP, only genistein stimulated baseline ATPase activity at concentrations of 0.01 μM and higher (Fig. 1B). None of the other chemicals increased basal ATPase activity (data not shown).

Figure 1. Inhibition and Activation of Human BCRP ATPase by Environmental Chemicals.

BCRP membranes were incubated with ATP and increasing concentrations of environmental chemicals in the (A) presence and (B) absence of sulfasalazine (10 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. Additional reactions included sodium orthovanadate in order to determine the ATPase activity attributed to transport. The amount of inorganic phosphate released was quantified by spectrophotometry following addition of a colorimetric reagent. Data are presented as the vanadate-sensitive mean ATPase activity ± SE of 3 replicates from one experiment. Following non-linear regression analysis, R2 values ranged between 0.87–0.99 with the exception of genistein (in the presence of sulfasalazine) (R2 = 0.13).

Table 2.

In Vitro Inhibition of Human BCRP Transporter by Environmental Chemicals using the ATPase and Inverted Vesicle Assays.1

| Inhibitory Concentration (IC50, μM) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chemical | ATPase Assay | Vesicle Assay |

| Genistein | N.D. | 1.9 |

| Tributyltin | 1.2 | 30.5 |

| Propargite | 2.6 | 31.8 |

| Methoxychlor | 5.2 | 38.0 |

| Zearalenone | 40.6 | 4.8 |

| Prochloraz | 42.6 | 18.7 |

| Propiconazole | 63.6 | 51.3 |

| Myclobutanil | 79.0 | 62.7 |

| Tebuconazole | >100.0 | 41.1 |

| Epoxiconazole | >100.0 | 64.7 |

| Bisphenol A | >100.0 | 55.5 |

The ability of environmental chemicals to inhibit BCRP-mediated ATPase activity in sulfasalazine (10 μM)-stimulated membranes and Lucifer yellow (50 μM) transport in inverted plasma membrane vesicles overexpressing human BCRP. IC50 values were calculated in Prism 5.0 using non-linear regression analysis. In the ATPase assay, IC50 values for tebuconazole, epoxiconazole, and bisphenol A were estimated to be greater than the concentrations tested.

N.D.: not detected.

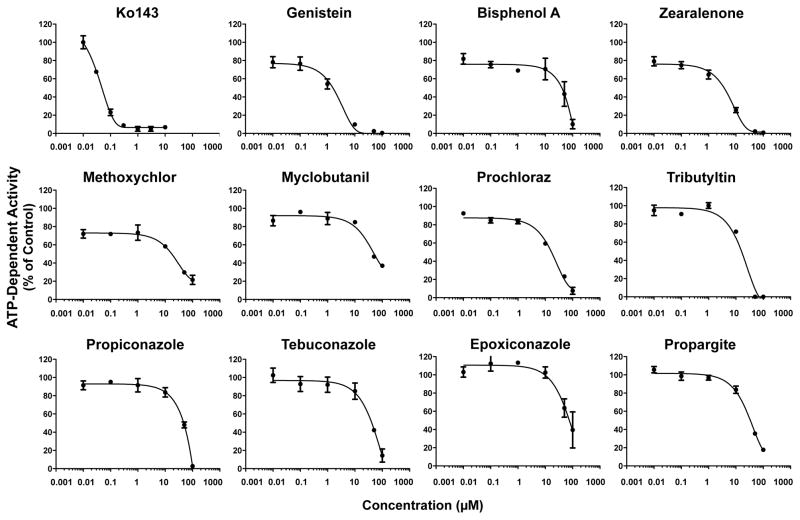

Inhibition of BCRP Transport Activity in Membrane Vesicles

A second in vitro screening approach was used to test the inhibition of BCRP transport of Lucifer yellow in inverted plasma membrane vesicles generated from BCRP-overexpressing cells. Ko143 inhibited BCRP transport with an IC50 value of 0.04 μM (Fig. 2). All environmental chemicals reduced BCRP activity in inverted vesicles. The most potent inhibitors of BCRP transport activity (IC50 values less than 5 μM) were genistein and zearalenone (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Inhibition of Human BCRP Transport in Inverted Vesicles by Environmental Chemicals.

Inverted BCRP-expressing plasma membrane vesicles (20 μg) were incubated with Lucifer yellow (50 μM) for 2 min in the presence and absence of ATP and increasing concentrations of test chemical at 37°C. Data are presented as mean ATP-dependent BCRP activity ± SE of 3–4 replicates from one experiment. Non-linear regression analysis yielded R2 values between 0.98–0.99.

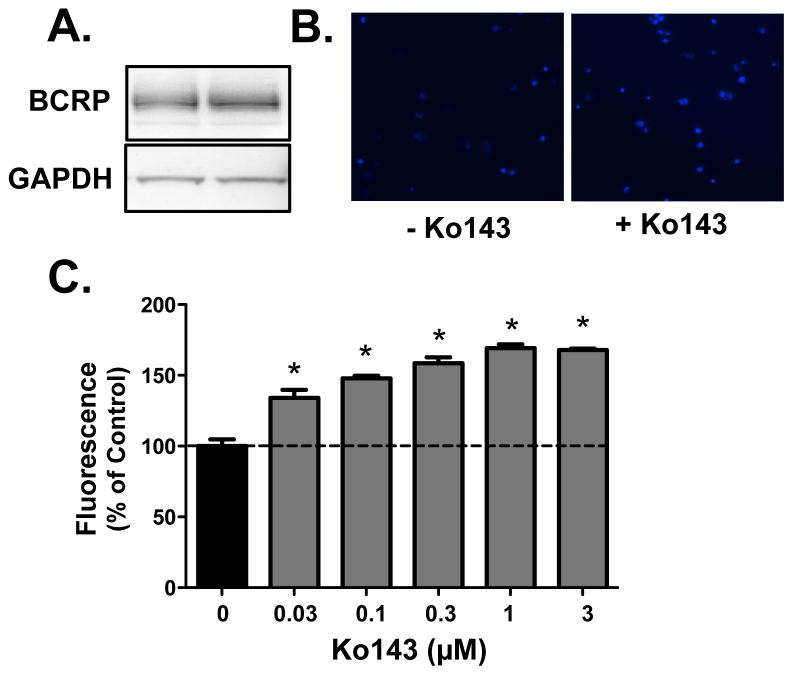

BCRP-Mediated Transport in BeWo Cells

Human placental BeWo cells express BCRP protein (Fig. 3A). Incubation of BeWo cells with Ko143 increased the accumulation of Hoechst 33342 as demonstrated by enhanced staining (Fig. 3B) and a greater percentage of cells with elevated fluorescence (Figs. 3C). Even the lowest concentration of Ko143 tested (0.03 μM) increased Hoechst 33342 levels in BeWo cells.

Figure 3. Characterization of BCRP Expression and Function in Human BeWo Placental Cells.

(A) Western blot of BCRP protein (~72 kDa) in BeWo cell lysates. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Representative images of Hoechst 33342 accumulation (blue) in BeWo cells in the absence and presence of Ko143 (1 μM) collected using the Nexcelom Cellometer Vision. (C) Bar graphs represent the mean relative fluorescence ± SE (n = 4) adjusted for cell size and normalized to control (no Ko143). Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) compared with control.

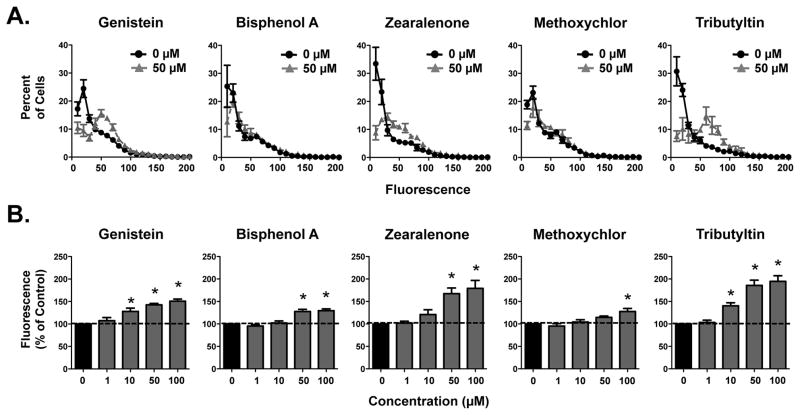

Inhibition of BCRP Transport Activity in BeWo Cells

Based on the initial ATPase activity and membrane vesicle screens, five environmental chemicals (genistein, bisphenol A, zearalenone, methoxychlor, and tributyltin) were selected for additional characterization by Hoechst accumulation in BeWo cells. None of the chemicals increased intracellular Hoechst fluorescence levels at the lowest concentration tested (1 μM) (Fig. 4). Genistein and tributyltin increased Hoechst fluorescence at 10 μM and above, whereas higher concentrations of zearalenone (50 μM), bisphenol A (50 μM) and methoxychlor (100 μM) were needed to inhibit BCRP (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Inhibition of BCRP Transport by Environmental Chemicals in Human BeWo Placental Cells.

(A) Line graphs represent the distribution of individual cell Hoechst 33342 fluorescence in the absence and presence of the various environmental chemicals (50 μM). Each point represents the mean percentage of cells ± SE (n = 3–4) exhibiting a quantity of fluorescence. (B) Bar graphs represent the mean relative fluorescence ± SE (samples run in triplicate from three to four independent experiments). Data were adjusted for cell size and normalized to control (0 μM). Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) compared with control.

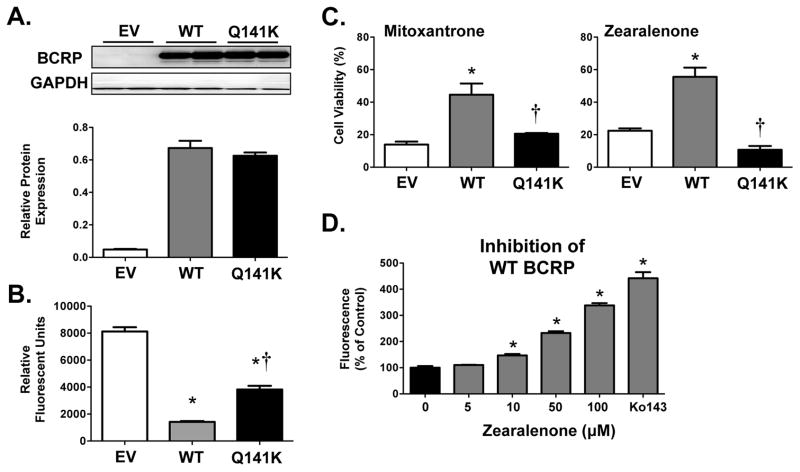

BCRP Expression, Function and Inhibition in Overexpressing Cells

Additional studies aimed to further examine the interaction of BCRP with an environmental chemical. Zearalenone was selected based upon its inhibitory activity in the ATPase, inverted vesicle, and BeWo assays. For this purpose, HEK cells transfected with EV, WT BCRP and the genetic BCRP variant Q141K were used. Expression of total BCRP protein in cell lysates was similar between WT and Q141K BCRP (Fig. 5A). Compared to cells transfected with EV, cells expressing the Q141K variants and WT BCRP were able to reduce intracellular Hoescht accumulation by 50–80% with a greater decrease of fluorescence in cells expressing WT BCRP (Fig. 5B). The ability of BCRP to protect against the cytotoxicity of xenobiotics is well known.32 Therefore, cell viability was assessed in the three cell lines treated with the known BCRP substrate and anticancer drug mitoxantrone as well as zearalenone (Fig. 5C). Mitoxantrone decreased cell viability in EV cells with an LC50 value of 0.34 μM. WT BCRP, and to some extent the Q141K variant, protected against mitoxantrone toxicity as evidenced by higher LC50 values (3.19 μM and 1.14 μM, respectively). Similarly, WT BCRP, but not the Q141K variant, conferred resistance to zearalenone toxicity in overexpressing cells relative to EV cells (Fig. 5C) and as evidenced by LC50 values (EV: 45.6 μM, WT: 171.2 μM, and Q141K: 40.6 μM). Similar to BeWo cells (Fig. 4), zearalenone increased Hoechst accumulation in WT BCRP cells at concentrations between 10–100 μM similar to Ko143 (Fig. 5D), directly confirming that zearalenone can inhibit WT BCRP activity.

Figure 5. Interaction of Human BCRP Transporter with Zearalenone in BCRP-Overexpressing Cells.

(A) Western blot of BCRP protein (~72 kDa) in cell lysates from HEK cells overexpressing empty vector (EV), wild-type BCRP (WT) and the Q141K BCRP variant (Q141K). GAPDH was used as a loading control. BCRP protein expression was semi-quantified and presented as a bar graph. (B) Accumulation of Hoechst 33342 (7 μM) was quantified using the Nexcelom Cellometer Vision. Bar graphs represent the mean relative fluorescence ± SE (n = 4) adjusted for cell size. (C) Cell viability was assessed using the alamar Blue Assay following exposure to mitoxantrone (5 μM) and zearalenone (100 μM) for 72 h. Data were normalized to untreated control cells and presented as mean ± SE. (D) Accumulation of Hoechst 33342 (7 μM) was quantified in WT cells exposed to increasing concentrations of zearalenone using the Nexcelom Cellometer Vision. Bar graphs represent the mean relative fluorescence (normalized to 0 μM) ± SE (n = 4 from one experiment) adjusted for cell size. Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) compared with control (0 μM or EV). Daggers (†) represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) compared with WT.

Transport of Zearalenone by BCRP

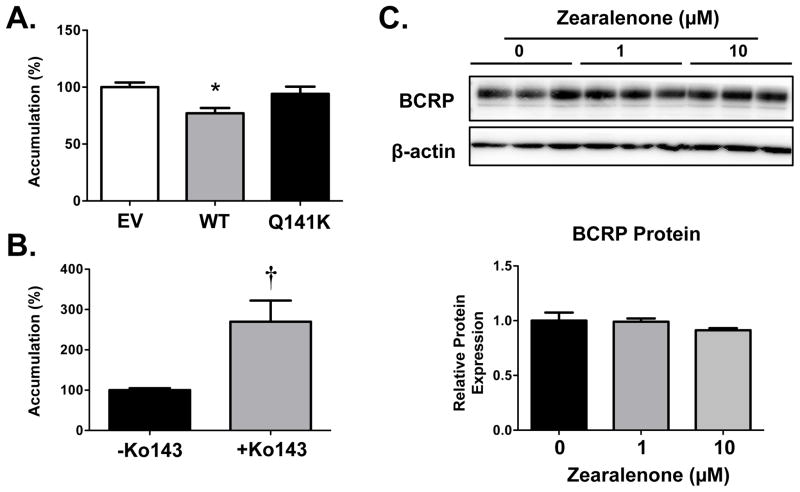

To directly test whether zearalenone is a substrate of BCRP, an ELISA was used to quantify intracellular zearalenone concentrations. Compared to cells expressing the EV and the Q141K variant, zearalenone levels were reduced 25% in cells transfected with WT BCRP (Fig. 6A). Similarly, inhibition of BCRP activity in BeWo cells with Ko143 increased zearalenone levels by 2.7-fold (Fig. 6B). It should be noted that exposure of BeWo cells to zearalenone for a 48 h period did not alter BCRP protein expression (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Transport of Zearalenone by the Human BCRP Transporter.

(A) HEK cells overexpressing empty vector (EV), wild-type BCRP (WT) and the Q141K BCRP variant (Q141K) were treated with zearalenone (50 μM) for 30 min (uptake period), washed, and then incubated in fresh culture media for 60 min (efflux period). (B) Human BeWo placental cells were treated with zearalenone (10 μM) in the presence and absence of the BCRP inhibitor, Ko143 (1 μM) for 30 min (uptake period), washed, and then incubated in fresh culture media with or without Ko143 (1 μM) for 60 min (efflux period). Intracellular zearalenone accumulation was quantified by ELISA and adjusted to protein concentrations of the cellular lysates. Values were normalized to control (EV or no Ko143). Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 12–15). (C) Western blot of BCRP protein (~72 kDa) in cell lysates from BeWo cells treated with 0, 1 or 10 μM zearalenone for 48 h. β-actin was used as a loading control. BCRP protein expression was semi-quantified and presented as a bar graph. Asterisks (*) represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to EV cells. Daggers (†) represent statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to no Ko143.

Discussion

The current manuscript utilized a series of transporter screening assays to investigate the interaction of eleven environmental chemicals with the human BCRP transporter. Each of the subcellular and cellular assays provided complementary data to categorize the chemicals as potential BCRP substrates and/or inhibitors. Based on the ATPase and vesicle inhibition results from IC50 values in at least one of the assays, five chemicals (genistein, tributyltin, propargite, methoxychlor, and zearalenone) appeared to be the most potent inhibitors. Subsequent experiments in human BeWo placental cells, which endogenously express BCRP, revealed inhibition of Hoechst 33342 efflux by genistein, zearalenone and tributyltin. Bisphenol A was also included in the BeWo inhibition studies for comparison since it was a relatively weak inhibitor in the ATPase and vesicle assays (Table 2). Using BeWo cells, as well as HEK cells expressing wild-type BCRP and the Q141K variant, zearalenone was confirmed as a novel substrate/inhibitor of BCRP in vitro. Collectively, these studies provide a complement of transporter screens to prioritize environmental chemicals as potential transporter substrates.

The BCRP transporter was identified in 1998 by multiple groups.33–35 Initial studies demonstrated that human BCRP mRNA was most prominently expressed in placenta. Interestingly, one of the laboratories coined the name “ABC transporter of the placenta or ABCP”, however, this abbreviation did not hold.33 Subsequent immunohistochemical studies localized BCRP specifically to placental trophoblasts and fetal capillary endothelial cells.36,37 It should be noted that Bcrp-null mice are fertile38, suggesting that this transporter is not necessary for reproduction or development. Rather, the BCRP transporter is responsible for removing chemicals from the placental villi back to the maternal blood (reviewed in 39). Because of this ‘barrier’ function, there is increasing interest in identifying drugs and chemicals that are substrates. Most importantly, mechanisms that reduce or inhibit BCRP function may increase exposure of the fetus to potentially toxic substrates. For example, the protein expression of the Q141K genetic variant is lower in human placentas from a Japanese population40, suggesting that BCRP function may be reduced in placentas that express this variant. Further clinical studies are necessary to determine whether pregnant women with Q141K homozygous and heterozygous placentas do in fact have higher fetal exposure to drugs and adverse developmental outcomes.

The current study identified zearalenone as a novel substrate of placental BCRP (Fig 6). Pilot studies in our laboratory using Bcrp-null mice have demonstrated ~10-fold higher plasma zearalenone levels after oral dosing compared to wild-types (data not shown). This likely results from the lack of BCRP protein in the intestinal tract of the null mice. In addition to BCRP, other ABC transporters including the multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRP) 1 and 2 can transport zearalenone in in vitro systems.41 Similar to BCRP, MRP2 is expressed on the apical (maternal-facing) surface of syncytiotrophoblasts whereas MRP1 is localized to the basolateral (fetal-facing) surface.42 The relative contribution of each of these transporters, as well as any potential passive transfer of zearalenone to the fetus, is not known. Nonetheless, zearalenone has been detected in fetal tissues from pregnant rats however at much lower levels than that found in placenta or maternal liver.43 This is important because of reports suggesting adverse developmental consequences of in utero exposure to zearalenone in multiple species. For example, maternal exposure to zearalenone (10 mg/kg/d) from gestational days 15 to 19 altered reproductive and mammary gland development in female offspring.44 In another study, treatment of pregnant mice with zearalenone throughout pregnancy increased the number of apoptotic cells in the testes of male offspring.45 Interestingly, zearalenone exposure to rats, albeit postnatally, decreases expression of Bcrp mRNA and protein in the testes.46

The current study adds to our understanding of the BCRP-mediated transport of environmental and dietary chemicals. In addition to zearalenone, BCRP transports heterocyclic amine carcinogens, 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline and 3-amino-1,4-dimethyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole, and the potent human liver carcinogen aflatoxin B1.15 Specifically in the human placenta, BCRP reduces the maternal-to-fetal transfer of the food-born carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine also called PhIP in an ex vivo perfusion system.47 More recently, it was demonstrated that the plasticizer bisphenol A and the pollutant perfluorooctanoic acid are substrates of BCRP. 11

The International Transporter Consortium recognizes the Q141K genetic variant of BCRP as a clinically relevant polymorphism.48 Individuals bearing the Q141K polymorphism exhibit elevated plasma concentrations of the hypolipidemic drug rosuvastatin49, the cancer drug gefitinib50 and chemicals such as uric acid51,52; the latter of which leads to an increased risk of gout.51,52 Because the Q141K allele can be observed frequently in Caucasians (7.4–11.1%) and East Asians (26.6–35.0%), there is the potential for significant populations to have a reduced capacity to efflux BCRP substrates.48 Thus, we aimed to understand differences in the transport of zearalenone between cells expressing wild-type BCRP or the Q141K variant. We observed enhanced zearalenone accumulation in cells expressing the Q141K variant compared to the wild-type BCRP protein (Fig. 6). Overexpression of Q141K in HEK cells results in similar total BCRP protein as the wild-type cells (Fig. 5). However, trafficking of the BCRP protein to the plasma membrane is impaired by this nonsynonymous polymorphism.53. In addition, the Q141K BCRP protein has defects in processing and folding that reduce its activity.54 Thus, the consequences of altered BCRP Q141K protein structure and localization include reduced efflux of zearalenone and impaired protection against zearalenone cytotoxicity compared to wild-type BCRP.

Each of the various assays employed in this study has advantages and limitations. For example, the ATPase and inverted vesicles provide direct access of test compounds to the transporter intracellular surface and do not require active uptake or passive permeability that are required in cellular systems such as BeWo cells. Based on the data shown in this study, it is clear that the ATPase assay can fail to detect substrates. Only genistein activated ATP hydrolysis in the BCRP-expressing plasma membranes (Fig. 1B), which is consistent with the known ability of BCRP to transport genistein.9 However, bisphenol A and zearalenone did not stimulate ATP hydrolysis despite being substrates (11 and Figs. 2 and 6). Disadvantages of inverted vesicles include limited applicability for chemicals with high passive permeability or nonspecific binding and the need for sensitive detection methods.16 Both the ATPase membranes and inverted vesicles demonstrated interactions of the environmental chemicals with the BCRP transporter, albeit at high concentrations in some cases. It is not clear whether the inhibition of BCRP is competitive or non-competitive. Prior work confirms the utility of BeWo cells as a model of placental BCRP transport.26 In the current study, Hoechst 33342 was used as a fluorescent substrate of BCRP, which allows for quantification by a fluorescent cell counter (Fig. 3 and 4). Interestingly, the chemicals that yielded more potent inhibition in the ATPase and vesicle assays, including genistein and zearalenone, showed similar results in the BeWo cell experiments. Additional experimental models including Bcrp-null mice as well as perfused human placentas are needed to more thoroughly characterize the in vivo and ex vivo disposition of zearalenone by BCRP.

Using a complement of in vitro assays, this study characterized the interaction of eleven environmental chemicals with the BCRP transporter. The chemicals inhibited BCRP to varying degrees, however, transport activity was only reduced at micromolar concentrations that may or may not be environmentally relevant. Further, it is not clear how long-term accumulation or mixtures of environmental chemicals might impact BCRP function. Nonetheless, screening assays prioritized zearalenone as a probable substrate, which was confirmed using transport experiments in which zearalenone was directly quantified. Future studies are needed to determine whether BCRP in the placenta reduces fetal exposure to zearalenone in vivo and whether impairment of BCRP-mediated efflux due to genetic variants such as Q141K increases the developmental toxicity of zearalenone.

Acknowledgments

The empty vector, wild-type, and Q141K BCRP expressing HEK cells were kindly provided by Dr. Robert Robey at the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. The authors appreciate the contributions of Myrna Trumbauer to the vesicle studies. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences [Grants ES020522, ES005022, ES007148, ES020721, ES021800], a component of the National Institutes of Health. Kristin Bircsak was supported by predoctoral fellowships from the American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. Qi Wang was supported by an Aresty Research Grant. Jingcheng Xiao participated in this project as part of an exchange program between Rutgers University and the China Pharmaceutical University.

Non-Standard Abbreviations

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- BCRP

breast cancer resistance protein

- EV

empty vector

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- MRP

multidrug resistance-associated protein

- Sf9

Spodoptera frugiperda 9

- WT

wild-type

References

- 1.Blazquez AG, Briz O, Romero MR, et al. Characterization of the role of ABCG2 as a bile acid transporter in liver and placenta. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:273–83. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.075143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grube M, Reuther S, Meyer Zu Schwabedissen H, et al. Organic anion transporting polypeptide 2B1 and breast cancer resistance protein interact in the transepithelial transport of steroid sulfates in human placenta. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:30–5. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.011411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki M, Suzuki H, Sugimoto Y, Sugiyama Y. ABCG2 transports sulfated conjugates of steroids and xenobiotics. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22644–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou L, Naraharisetti SB, Wang H, Unadkat JD, Hebert MF, Mao Q. The breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp1/Abcg2) limits fetal distribution of glyburide in the pregnant mouse: an Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Unit Network and University of Washington Specialized Center of Research Study. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:949–59. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gedeon C, Anger G, Piquette-Miller M, Koren G. Breast cancer resistance protein: mediating the trans-placental transfer of glyburide across the human placenta. Placenta. 2008;29:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Wang H, Unadkat JD, Mao Q. Breast cancer resistance protein 1 limits fetal distribution of nitrofurantoin in the pregnant mouse. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:2154–8. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeboah D, Sun M, Kingdom J, et al. Expression of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) in human placenta throughout gestation and at term before and after labor. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;84:1251–8. doi: 10.1139/y06-078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuiper GG, Lemmen JG, Carlsson B, et al. Interaction of estrogenic chemicals and phytoestrogens with estrogen receptor beta. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4252–63. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enokizono J, Kusuhara H, Sugiyama Y. Effect of breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp/Abcg2) on the disposition of phytoestrogens. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:967–75. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazur CS, Marchitti SA, Dimova M, Kenneke JF, Lumen A, Fisher J. Human and rat ABC transporter efflux of bisphenol a and bisphenol a glucuronide: interspecies comparison and implications for pharmacokinetic assessment. Toxicol Sci. 2009;128:317–25. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dankers AC, Roelofs MJ, Piersma AH, et al. Endocrine disruptors differentially target ATP-binding cassette transporters in the blood-testis barrier and affect Leydig cell testosterone secretion in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 2013;136:382–91. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonso-Magdalena P, Vieira E, Soriano S, et al. Bisphenol A exposure during pregnancy disrupts glucose homeostasis in mothers and adult male offspring. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1243–50. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1001993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newbold RR, Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol a at environmentally relevant doses adversely affects the murine female reproductive tract later in life. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:879–85. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandenberg LN, Maffini MV, Wadia PR, Sonnenschein C, Rubin BS, Soto AM. Exposure to environmentally relevant doses of the xenoestrogen bisphenol-A alters development of the fetal mouse mammary gland. Endocrinology. 2007;148:116–27. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilakivi-Clarke L, Cho E, Clarke R. Maternal genistein exposure mimics the effects of estrogen on mammary gland development in female mouse offspring. Oncol Rep. 1998;5:609–16. doi: 10.3892/or.5.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brouwer KL, Keppler D, Hoffmaster KA, et al. In vitro methods to support transporter evaluation in drug discovery and development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:95–112. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang H, Shen DR, Han YH, et al. Development of novel, 384-well high-throughput assay panels for human drug transporters: drug interaction and safety assessment in support of discovery research. J Biomol Screen. 2013;18:1072–83. doi: 10.1177/1087057113494807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elsby R, Smith V, Fox L, et al. Validation of membrane vesicle-based breast cancer resistance protein and multidrug resistance protein 2 assays to assess drug transport and the potential for drug-drug interaction to support regulatory submissions. Xenobiotica. 2011;41:764–83. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2011.578761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallus J, Juvale K, Wiese M. Characterization of 3-methoxy flavones for their interaction with ABCG2 as suggested by ATPase activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838:2929–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bircsak KM, Richardson JR, Aleksunes LM. Inhibition of human MDR1 and BCRP transporter ATPase activity by organochlorine and pyrethroid insecticides. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2013;27:157–64. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bircsak KM, Gibson CJ, Robey RW, Aleksunes LM. Assessment of drug transporter function using fluorescent cell imaging. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2013;57(Unit 23):6. doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx2306s57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robey RW, Lin B, Qiu J, Chan LL, Bates SE. Rapid detection of ABC transporter interaction: potential utility in pharmacology. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2011;63:217–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morisaki K, Robey RW, Ozvegy-Laczka C, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms modify the transporter activity of ABCG2. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56:161–72. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0931-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollex EK, Anger G, Hutson J, Koren G, Piquette-Miller M. Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)-mediated glyburide transport: effect of the C421A/Q141K BCRP single-nucleotide polymorphism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:740–4. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.030791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ceckova M, Libra A, Pavek P, et al. Expression and functional activity of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP, ABCG2) transporter in the human choriocarcinoma cell line BeWo. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evseenko DA, Paxton JW, Keelan JA. ABC drug transporter expression and functional activity in trophoblast-like cell lines and differentiating primary trophoblast. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1357–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00630.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prouillac C, Videmann B, Mazallon M, Lecoeur S. Induction of cells differentiation and ABC transporters expression by a myco-estrogen, zearalenone, in human choriocarcinoma cell line (BeWo) Toxicology. 2009;263:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobsen PR, Axelstad M, Boberg J, et al. Persistent developmental toxicity in rat offspring after low dose exposure to a mixture of endocrine disrupting pesticides. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;34:237–50. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirchner S, Kieu T, Chow C, Casey S, Blumberg B. Prenatal exposure to the environmental obesogen tributyltin predisposes multipotent stem cells to become adipocytes. Mol Endocrin. 2010;24:526–39. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palanza P, Morellini F, Parmigiani S, vom Saal FS. Prenatal exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals: effects on behavioral development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23:1011–27. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibson CJ, Hossain MM, Richardson JR, Aleksunes LM. Inflammatory regulation of ATP binding cassette efflux transporter expression and function in microglia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;343:650–60. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.196543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbott BL. ABCG2 (BCRP): a cytoprotectant in normal and malignant stem cells. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2006;4:63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allikmets R, Schriml LM, Hutchinson A, Romano-Spica V, Dean M. A human placenta-specific ATP-binding cassette gene (ABCP) on chromosome 4q22 that is involved in multidrug resistance. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5337–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doyle LA, Yang W, Abruzzo LV, et al. A multidrug resistance transporter from human MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15665–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyake K, Mickley L, Litman T, et al. Molecular cloning of cDNAs which are highly overexpressed in mitoxantrone-resistant cells: demonstration of homology to ABC transport genes. Cancer Res. 1999;59:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maliepaard M, Scheffer GL, Faneyte IF, et al. Subcellular localization and distribution of the breast cancer resistance protein transporter in normal human tissues. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3458–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jonker JW, Smit JW, Brinkhuis RF, et al. Role of breast cancer resistance protein in the bioavailability and fetal penetration of topotecan. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1651–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.20.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jonker JW, Buitelaar M, Wagenaar E, et al. The breast cancer resistance protein protects against a major chlorophyll-derived dietary phototoxin and protoporphyria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15649–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202607599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ni Z, Mao Q. ATP-binding cassette efflux transporters in human placenta. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12:674–85. doi: 10.2174/138920111795164057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi D, Ieiri I, Hirota T, et al. Functional assessment of ABCG2 (BCRP) gene polymorphisms to protein expression in human placenta. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:94–101. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.001628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Videmann B, Mazallon M, Prouillac C, Delaforge M, Lecoeur S. ABCC1, ABCC2 and ABCC3 are implicated in the transepithelial transport of the myco-estrogen zearalenone and its major metabolites. Toxicol Letters. 2009;190:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.St-Pierre MV, Serrano MA, Macias RI, et al. Expression of members of the multidrug resistance protein family in human term placenta. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1495–503. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.4.R1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernhoft A, Behrens GH, Ingebrigtsen K, et al. Placental transfer of the estrogenic mycotoxin zearalenone in rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15:545–50. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(01)00159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nikaido Y, Yoshizawa K, Danbara N, et al. Effects of maternal xenoestrogen exposure on development of the reproductive tract and mammary gland in female CD-1 mouse offspring. Reprod Toxicol. 2004;18:803–11. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lopez-Casas PP, Mizrak SC, Lopez-Fernandez LA, Paz M, de Rooij DG, del Mazo J. The effects of different endocrine disruptors defining compound-specific alterations of gene expression profiles in the developing testis. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;33:106–15. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koraichi F, Inoubli L, Lakhdari N, et al. Neonatal exposure to zearalenone induces long term modulation of ABC transporter expression in testis. Toxicology. 2013;310:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myllynen P, Kummu M, Kangas T, et al. ABCG2/BCRP decreases the transfer of a food-born chemical carcinogen, 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) in perfused term human placenta. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;232:210–7. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giacomini KM, Balimane PV, Cho SK, et al. International Transporter Consortium commentary on clinically important transporter polymorphisms. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:23–6. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomlinson B, Hu M, Lee VW, et al. ABCG2 polymorphism is associated with the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol response to rosuvastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:558–62. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cusatis G, Gregorc V, Li J, et al. Pharmacogenetics of ABCG2 and adverse reactions to gefitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1739–42. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsuo H, Takada T, Ichida K, et al. Identification of ABCG2 dysfunction as a major factor contributing to gout. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2011;30:1098–104. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2011.627902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang L, Spencer KL, Voruganti VS, et al. Association of functional polymorphism rs2231142 (Q141K) in the ABCG2 gene with serum uric acid and gout in 4 US populations: the PAGE Study. Amer J Epidemiol. 2013;177:923–32. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Furukawa T, Wakabayashi K, Tamura A, et al. Major SNP (Q141K) variant of human ABC transporter ABCG2 undergoes lysosomal and proteasomal degradations. Pharm Res. 2009;26:469–79. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9752-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saranko H, Tordai H, Telbisz A, et al. Effects of the gout-causing Q141K polymorphism and a CFTR DeltaF508 mimicking mutation on the processing and stability of the ABCG2 protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;437:140–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Armenti AE, Zama AM, Passantino L, Uzumcu M. Developmental methoxychlor exposure affects multiple reproductive parameters and ovarian folliculogenesis and gene expression in adult rats. Toxicol Applied Pharmacol. 2008;233:286–96. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rockett JC, Narotsky MG, Thompson KE, et al. Effect of conazole fungicides on reproductive development in the female rat. Reprod Toxicol. 2006;22:647–58. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goetz AK, Ren H, Schmid JE, et al. Disruption of testosterone homeostasis as a mode of action for the reproductive toxicity of triazole fungicides in the male rat. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95:227–39. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noriega NC, Ostby J, Lambright C, Wilson VS, Gray LE., Jr Late gestational exposure to the fungicide prochloraz delays the onset of parturition and causes reproductive malformations in male but not female rat offspring. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:1324–35. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.031385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chamorro-Garcia R, Sahu M, Abbey RJ, Laude J, Pham N, Blumberg B. Transgenerational inheritance of increased fat depot size, stem cell reprogramming, and hepatic steatosis elicited by prenatal exposure to the obesogen tributyltin in mice. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:359–66. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Si J, Han X, Zhang F, et al. Perinatal exposure to low doses of tributyltin chloride advances puberty and affects patterns of estrous cyclicity in female mice. Environ Toxicol. 2012;27:662–70. doi: 10.1002/tox.21756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]