Summary

Cross-beta fibrous protein aggregates (amyloids and amyloid-based prions) are found in mammals (including humans) and fungi (including yeast), and are associated with both diseases and heritable traits. The Hsp104/70/40 chaperone machinery controls propagation of yeast prions. The Hsp70 chaperones Ssa and Ssb show opposite effects on [PSI+], a prion form of the translation termination factor Sup35 (eRF3). Ssb is bound to translating ribosomes via ribosome-associated complex (RAC), composed of Hsp40-Zuo1 and Hsp70-Ssz1. Here we demonstrate that RAC disruption increases de novo prion formation in a manner similar to Ssb depletion, but interferes with prion propagation in a manner similar to Ssb overproduction. Release of Ssb into the cytosol in RAC-deficient cells antagonizes binding of Ssa to amyloids. Thus, propagation of an amyloid formed due to lack of ribosome-associated Ssb can be counteracted by cytosolic Ssb, generating a feedback regulatory circuit. Release of Ssb from ribosomes is also observed in wild type cells during growth in poor synthetic medium. Ssb is, in a significant part, responsible for the prion destabilization in these conditions, underlining the physiological relevance of the Ssb-based regulatory circuit.

Keywords: amyloid, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Ssz1, Sup35, Zuo1

Introduction

Cross-β fibrous protein aggregates (amyloids) are associated with a variety of diseases in animals and humans, including widespread Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, and transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), or prion diseases (Eisenberg & Jucker, 2012; Prusiner, 2013). Many of amyloid diseases are fatal, and most of them are incurable. Mechanisms of amyloid formation and propagation in vivo, as well as cellular control of these processes are still poorly understood. Self-perpetuating heritable amyloids, termed fungal (and specifically, yeast) prions, are also found in fungi, mostly in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast (e. g., see Wickner, 1994; Coustou et al, 1997; Derkatch et al, 2001; Du et al, 2008; Patel et al, 2009; Alberti et al, 2009; Rogoza et al, 2010; Halfmann et al, 2012; Suzuki et al, 2013). While the biological roles of yeast prions are still being debated (Halfmann & Lindquist, 2010; McGlinchey et al, 2011; Kelly & Wickner, 2013; Holmes et al, 2013), some prions control detectable phenotypic traits, making them an excellent model for studying general mechanisms of amyloid formation and propagation.

The yeast prion [PSI+] (for review, see Liebman & Chernoff, 2012) is an amyloid isoform of the yeast translation termination (release) factor Sup35, or eRF3 (Stansfield et al, 1995; Zhouravleva et al, 1995). [PSI+] strains are partially defective in translation termination, thus exhibiting a convenient phenotype, nonsense-suppression (Cox, 1965; Liebman & Chernoff, 2012; Nizhnikov et al, 2014). Sup35 protein of the same sequence can form different variants (“strains”) of the [PSI+] prion, distinguishable from each other by various parameters, for example the stringency of nonsense-suppression, and the efficiency of transmission in cell divisions (Derkatch et al, 1996). De novo formation of [PSI+] is induced by overproduction of Sup35 protein (Chernoff et al, 1993) or its prion domain Sup35N (Derkatch et al, 1996), and regulated by chaperones (Chernoff et al, 1999; Allen et al, 2005; Park et al, 2006). In vivo propagation of [PSI+] and other yeast prions requires the chaperone machinery, composed of the Hsp104, Hsp70 and Hsp40 proteins (for review, see Chernova et al. 2014). The current view is that the concerted action of these chaperones leads to efficient fragmentation of amyloid fibrils into smaller oligomers, capable of immobilizing the non-prion protein and converting it into a prion (Paushkin et al, 1996; Wegrzyn et al, 2001; Jones et al. 2004; Satpute-Krishnan et al, 2007; Tipton et al, 2008; Winkler et al, 2012). Such a fragmentation initiates new rounds of amyloid growth. A lack of Hsp104 impairs amyloid fragmentation and results in prion loss in cell divisions; however, excess Hsp104 also increases [PSI+] loss (Chernoff et al, 1995). This is partially compensated by simultaneous overproduction of the cytosolic chaperone Hsp70-Ssa (Newnam et al, 1999), which restores prion fragmentation and propagation when acting together with Hsp104 (Allen et al, 2005; Reidy & Masison, 2011; Winkler et al, 2012). Another Hsp70 subfamily, Ssb, is represented by two non-essential nearly identical proteins, Ssb1 and Ssb2 (Nelson et al, 1992). Ssb is associated with translating ribosomes via the heterodimeric ribosome-associated complex (RAC), which is composed of the cochaperones, Hsp40-Zuo1 and atypical Hsp70-Ssz1 (Gautschi et al, 2001; Huang et al, 2005), and promotes folding of a nascent polypeptide (James et al, 1997; Willmund et al, 2013). In contrast to Ssa, the overproduction of Ssb increases [PSI+] elimination in the presence of excess Hsp104 (Chernoff et al, 1999) and interferes with propagation of some variants of [PSI+] (Kushnirov et al, 2000; Chacinska et al, 2001; Allen et al, 2005), while a lack of Ssb increases de novo [PSI+] formation and antagonizes [PSI+] curing by excess Hsp104 (Chernoff et al, 1999). In vitro, Ssb antagonizes amyloid formation by the NM region of Sup35, and this effect is further increased in the presence of Zuo1/Ssz1 (Shorter & Lindquist, 2008). To investigate the mechanisms of Ssb effects on amyloids in vivo, we altered the RAC complex, which mediates binding of Ssb to the ribosome.

Results

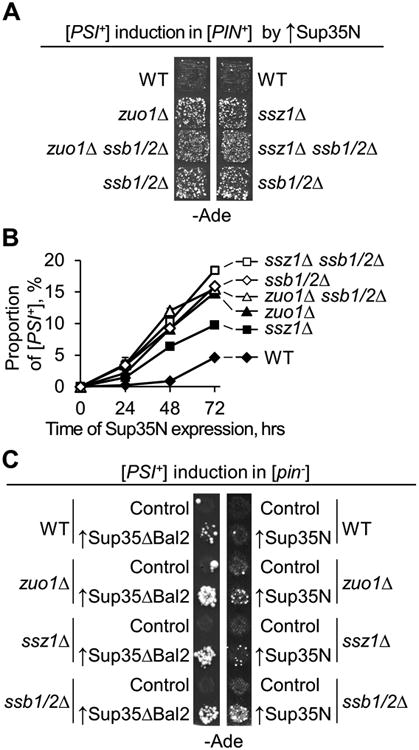

RAC alterations increase de novo [PSI+] formation

Transient overproduction of the Sup35 prion-forming domain (Sup35N) induces de novo formation of [PSI+] (Derkatch et al, 1996). This induction is normally efficient only in the presence of another prion, e. g. [PIN+], the prion form of Rnq1 (Derkatch et al, 1997; Derkatch et al, 2001). However, modified versions of Sup35N, such as Sup35ΔBal2 having a highly hydrophobic extension, can induce [PSI+] even in the absence of [PIN+] (Derkatch et al, 1997). Prion formation can be detected by suppression of the reporter nonsense-allele ade1-14 (UGA), resulting in growth on medium lacking adenine (see Liebman & Chernoff, 2012). Previously, we have shown that the deletion of both genes coding for Ssb (ssb1/2Δ) increases de novo [PSI+] induction (Chernoff et al, 1999). Now, we have demonstrated that the single deletion zuo1Δ or (to a lesser extent) ssz1Δ also increases de novo induction of Ade+ colonies by Sup35N, transiently overexpressed from the galactose-inducible promoter in the [psi- PIN+] background (Fig. 1AB). Prion formation was detected by an appearance of colonies capable of growing on –Ade medium after transient induction by galactose. Eight independent Ade+ colonies from each strain (wild type, zuo1Δ and ssz1Δ) have been tested for their ability to maintain the Ade+ phenotype after incubation on the medium containing guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl), an agent that inhibits [PSI+] propagation in the generation-dependent manner but does not influence nuclear mutations (Eaglestone et al, 2000). All Ade+ colonies were GuHCl-curable, confirming that in each case, the Ade+ phenotype was controlled by the [PSI+] prion rather than by a nuclear mutation. Notably, [PSI+] induction by the [PIN+]-independent construct Sup35ΔBal2 in the [pin-] background was also increased by zuo1Δ and ssz1Δ, as well as by ssb1/2Δ (Fig. 1C). Moreover, RAC alterations, as well as the ssb1/2Δ double deletion enabled the typically [PIN+]-dependent construct Sup35N to induce [PSI+] even in the absence of [PIN+] (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Increased [PSI+] formation in the strains with RAC deficiencies.

A and B. Increased de novo [PSI+] formation in the [psi-] strains, bearing [PIN+] prion and lacking Ssz1, Zuo1, and/or Ssb. Yeast cultures were grown in liquid medium with galactose and raffinose, selective for the galactose-inducible PGAL-SUP35N plasmid. On panel (A), aliquots of 24-hr cultures containing 6,000 cells each were spotted onto -Ade medium for [PSI+] detection. Equal proportions of plasmid-containing cells in each aliquot were confirmed by spotting serial decimal dilutions onto plasmid-selective medium (data not shown). On panel (B), yeast cultures were grown in triplicate for 72 hours, with aliquots taken every 24 hrs and plated onto plasmid-selective medium with glucose. Resulting colonies were velveteen replica plated onto -Ade and YPD media for [PSI+] detection. Standard errors of mean are shown, except for cases when they were smaller than the size of the symbol.

C. Increased de novo [PSI+] formation in the [pin-] strain lacking Ssz1, Zuo1, and/or Ssb, in the presence of the SUP35ΔBal2 construct expressed from the endogenous PSUP35 promoter (left panel), or PCUP1-SUP35N construct induced for 2 days by 100 μM CuSO4 (right panel). -Ade plates were scanned after 10 days of incubation.

Here and further, WT is wild type, Control – empty vector, ↑ indicates an excess of a respective protein.

The effects of the ssb1/2Δ double deletion and triple deletions (ssb1/2Δ zuo1Δ and ssb1/2Δ ssz1Δ) on [PSI+] induction were identical to each other (Fig. 1B), indicating that all of the respective proteins influence prion induction via the same pathway. Remarkably, the prion-inducing effect of RAC alterations was not restricted only to the conditions of Sup35N overproduction, as zuo1Δ and ssz1Δ strains also exhibited an increased frequency of spontaneous [PSI+] formation in the [PIN+] background (Fig. S1), similar to what has been reported previously for ssb1/2Δ (Chernoff et al, 1999). Increased prion formation in the RAC deficient cells can be explained by accumulation of misfolded proteins, potentially convertible into a prion, on the ribosomes lacking Ssb. These data are consistent with the role of the Ssb/Zuo1/Ssz1 complex in the folding and quality control of a nascent polypeptide (James et al, 1997; Willmund et al, 2013).

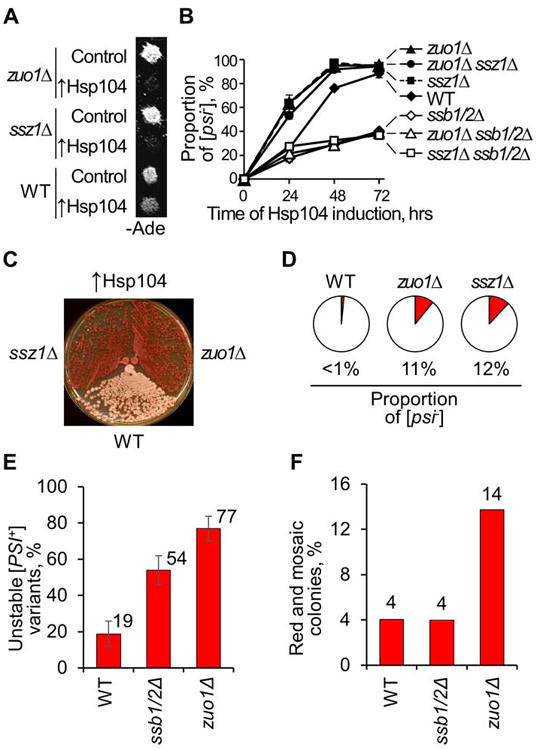

RAC alterations antagonize [PSI+] propagation

Previously, we have shown that the ssb1/2Δ deletion antagonizes, while overproduction of Ssb facilitates the elimination of [PSI+] by excess Hsp104 (Chernoff et al, 1999). To determine if RAC alterations exhibit the same effect on [PSI+] as does ssb1/2Δ, we have transiently overexpressed Hsp104 from the galactose-inducible construct in the wild-type [PSI+] strain and isogenic strains containing the zuo1Δ and/or ssz1Δ deletions. [PSI+] loss was detected by the growth (Ade- versus Ade+) and/or color assay on the glucose medium following galactose induction. Surprisingly, we found that each single deletion of zuo1Δ or ssz1Δ, or double deletion zuo1Δ ssz1Δ further increase [PSI+] elimination by excess Hsp104 (Fig. 2ABC). This effect is opposite to the effect of ssb1/2Δ and similar to the effect of excess Ssb (Chernoff et al, 1999). Moreover, ssb1/2Δ reversed the effects of zuo1Δ or ssz1Δ (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2A), indicating that the increase in [PSI+] curing in the strains with RAC deficiencies is mediated by the Ssb chaperone.

Figure 2. Ssb-dependent [PSI+] destabilization by RAC deficiencies.

A and B. RAC deficiencies increase loss of strong [PSI+] variant in the presence of excess Hsp104,induced from the PGAL promoter. In plate assay (A), yeast cultures were incubated on galactose medium, selective for the plasmid, for 2 days, followed by velveteen replica plating onto glucose -Ade medium selective for the plasmid. [PSI+] destabilization was detected as decreased growth on -Ade; images were taken after 4 days of incubation. For quantitative assay (B), yeast cultures were grown in liquid medium with galactose and raffinose, selective for the PGAL-HSP104 plasmid, and aliquots were spread on plasmid-selective medium with glucose after indicated time periods, followed by velveteen replica plating onto -Ade medium to detect [PSI+]. At least three repeats with independent cultures were performed for each strain/plasmid combinations. Standard errors of mean are shown, except for the cases when they were smaller than the size of the symbol. Quantitative assay data on panel B also show that the effect of ssb1/2Δ on [PSI+] curing by excess Hsp104 is opposite to the effects of zuo1Δ, ssz1Δ and zuo1Δ ssz1Δ, and that destabilization of [PSI+] in zuo1Δ and ssz1Δ strains is Ssb-dependent. This is confirmed by plate images shown in Fig. S2A.

C. Deletion of ZUO1 or SSZ1 enhances elimination of weak [PSI+] in the presence of excess Hsp104. Wild type and deletion strains were transformed by the centromeric plasmid bearing the HSP104 gene under its endogenous promoter. Plasmid-positive colonies were streaked on YPD medium. [PSI+] loss was detected by red color after 6 days of incubation at 25°C.

D. Mitotic loss of weak [PSI+] variant at normal Hsp104 levels is increased by zuo1Δ or ssz1Δ. An average proportion of [psi-] colonies in the mitotic progeny of three independent [PSI+] cultures streaked on YPD medium is shown as a dark sector for each strain. Examples of plate images for this experiment are shown in Fig. S2B.

E. Proportion of unstable [PSI+] variants among independent [PSI+] isolates, induced de novo by transient overproduction of Sup35N in the isogenic [psi- PIN+] wild type (WT), ssb1/2Δ and zuo1Δ strains. A [PSI+] isolate was considered unstable if red ([psi-]) or mosaic ([PSI+]/[psi-]) colony(ies) were detected among at least 30 colonies originated from this isolate after streaking on YPD medium. Standard errors of proportion are shown.

F. Average percentage of red and mosaic colonies per unstable [PSI+] isolate (data are from the same experiment as in panel E).

As mentioned above, there are a variety of [PSI+] prion strains, or variants (Derkatch et al, 1996). Variants with higher phenotypic stringency (that is, higher level of nonsense-suppression) and higher mitotic transmissibility are typically designated as “strong” variants, while variants with lower phenotypic stringency and lower mitotic transmissibility are designated as “weak” variants. In addition to their phenotypic patterns, the [PSI+] variants may also differ from each other by their sensitivities to chaperones (Derkatch et al, 1996; Borchsenius et al, 2006; Tanaka et al, 2006). Continuous overproduction of Ssb is known to antagonize propagation of a weak [PSI+] variant at normal Hsp104 levels, leading to prion loss (Kushnirov et al, 2000; Chacinska et al, 2001; Allen et al, 2005). Likewise, zuo1Δ and ssz1Δ increased the spontaneous loss of the weak [PSI+] prion variant, used in our work, even at normal levels of Hsp104 (Fig. 2D and Fig. S2B).

To determine if RAC disruption influences multiple prion isolates rather than just one specific weak [PSI+] isolate used in the abovementioned experiments, we compared the proportions of stable and unstable [PSI+] isolates induced de novo by transient overproduction of Sup35N in the isogenic wild type, ssb1/2Δ and zuo1Δ strains. As shown on Fig. 2E, the zuo1Δ strain produces the 4-fold higher fraction of the unstable [PSI+] isolates exhibiting detectable spontaneous loss of a prion, compared to the wild type strain. Proportion of the unstable [PSI+] isolates in the ssb1/2Δ strain was higher than in the wild type strain but lower than in the zuo1Δ strain. Notably, average frequencies of [PSI+] loss in the unstable isolates were similar in the wild type and ssb1/2Δ strains, but increased in the zuo1Δ strain (Fig. 2F). These data confirm that RAC disruption destabilizes various weak isolates of [PSI+].

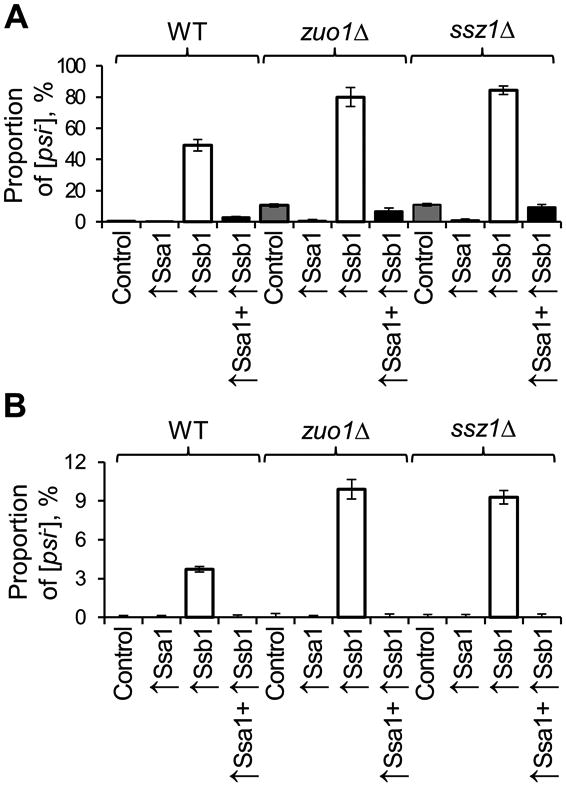

Antagonistic effects of Ssa and Ssb on [PSI+] loss

We have confirmed previous reports (Kushnirov et al, 2000; Chasinska et al, 2001; Allen et al, 2005) by showing that overproduction of Ssb leads to destabilization of the weak [PSI+] variant used in our work. In addition, we have demonstrated that overproduction of Ssb further increases the [PSI+]-destabilizing effect of RAC deletions, resulting in the increased loss of not only weak (Fig. 3A and Fig. S2C) but also strong (Fig. 3B and Fig. S2D) [PSI+] variants. Notably, when both Ssa and Ssb were co-overexpressed from multicopy plasmids, [PSI+] loss was decreased, compared to the strains overexpressing Ssb alone (Fig. 3 and Fig. S2DE). These data show that a competition between Ssb and Ssa, rather than the level of each chaperone per se is crucial for [PSI+] propagation. Remarkably, overproduction of Ssa antagonized spontaneous [PSI+] loss in the zuo1Δ and ssz1Δ strains (Fig. 3A and Fig. S2C). This shows that similar to the case of Ssb overproduction, effect of RAC alterations on [PSI+] is modulated by Ssa levels.

Figure 3. Antagonistic effects of Ssa and Ssb overproduction on [PSI+] loss.

[PSI+] loss, detected by appearance of red colonies as in Figs. 2C and S1B-D, is increased in the presence of excess Ssb (more efficiently, in zuo1Δ or ssz1Δ background) and counteracted by excess Ssa for both weak (A) and strong (B) [PSI+] variants. Ssa1 and Ssb1 were overexpressed using multicopy plasmids. At least three repeats were performed for each combination, with standard deviations shown. For color plate images, see Figs. S1C and S1D. Standard errors of mean are shown.

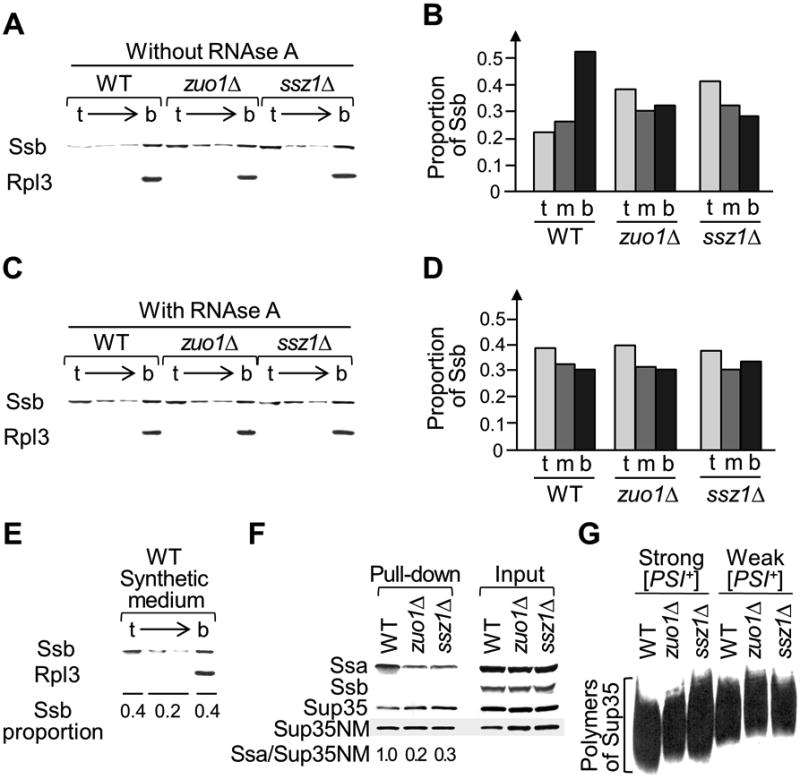

RAC alterations or certain growth conditions cause a release of Ssb from the ribosome into the cytosol

Neither cellular levels of major chaperones involved in [PSI+] propagation and curing (Hsp104, Ssa, Ssb, and Ssa cochaperones Hsp40-Sis1 and Hsp40-Ydj1), nor levels of the Sup35 protein itself were affected by zuo1Δ or ssz1Δ, independently of the presence or absence of [PSI+], or nature of the [PSI+] variant (Fig. S3A-C). However, intracellular localization of Ssb was altered in the strains with RAC deficiencies. In the extracts of wild type cells grown in rich organic medium, about 50% of Ssb was localized to the bottom of the sucrose gradient, together with the ribosomes, detected by antibodies to the ribosomal protein Rpl3 (Vilardell & Warner, 1997), and only 20% of Ssb was detected in the top fraction (Fig, 4AB). In contrast, only 30% of Ssb remained in the bottom fraction in extracts prepared from zuo1Δ or ssz1Δ cells grown in the same conditions, and about 40% of the Ssb was found on the top of the gradient in these extracts (Fig. 4AB). The shift of Ssb to the top of the sucrose gradient caused by zuo1Δ or ssz1Δ was detected in both [PSI+] and [psi-] backgrounds (compare Fig. 4A to Fig. S3D). Notably, a treatment with RNAse A, that digests mRNA and disrupts polysomes (James et al, 1997) shifted a significant fraction of Ssb to the top of the sucrose gradient in the wild type extracts but had no significant effect on Ssb distribution in the zuo1Δ and ssz1Δ extracts, indicating that most of Ssb is not associated with translating ribosomes in strains with RAC disruptions (Fig. 4CD and Fig. S3E). Other major chaperones (Hsp104 and Ssa) were always abundant in the top three fractions of the sucrose gradient and not affected by RNAse A treatment (Fig. S3F). Our results confirm previous reports that Ssb is specifically associated with translating ribosomes via RAC (Gautschi et al, 2001; Huang et al, 2005; Willmund et al, 2013).

Figure 4. Effects of RAC deficiencies on Hsp70 proteins and Sup35 aggregates.

A and B. Soluble (cytosolic) fraction of Ssb is enriched in strains lacking Zuo1 or Ssz1. C and D. Polysome destruction increases amount of soluble Ssb in the wild type extracts but not in the zuo1Δ or ssz1Δ extracts. On panels A and C, cultures were grown in the rich (YPD) medium, then proteins were isolated, fractionated by centrifugation in a sucrose gradient, and equal amount of each fraction from the top (t) to the bottom (b) of sucrose gradient was loaded onto SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were detected by Western blot using respective antibodies. On panel C, lysates were treated with RNAse A to eliminate mRNA and disrupt polysomes, prior to gradient centrifugation. Ribosomal protein Rpl3 served as a loading control and as a marker for ribosomal/polysomal fraction. Panels B and D present quantitation of Ssb distribution among sucrose gradient fractions prepared as described above (A and C, respectively). Designations: t - top (corresponding to the top fraction of panels A or C), m – middle (a sum of two middle fractions on panels A or C), b – bottom (corresponding to the bottom fraction on panels A or C). Relative proportions of the Ssb protein in each fraction are given. For each of the WT, zuo1Δ and ssz1Δ strains in panels B and D, averages of the [PSI+] (as in examples shown in Fig. 4A and Fig. 4C) and [psi-] (as in examples shown in Fig. S3D and Fig. S3E) samples are calculated in each case, as we have not detected systematic differences in Ssb distribution between the isogenic [PSI+] and [psi-] strains. For the data presented on panels B and D, standard errors of mean did not exceed 0.04.

E. Incubation in synthetic medium increases the proportion of cytosolic Ssb (detected in the top gradient fractions). Protein isolation and gradient centrifugation were performed as in panels A and C. All experiments shown in panels A, C and E were performed at least in triplicate with similar results.

F. Deletion of ZUO1 or SSZ1 decreases amount on Ssa bound to Sup35, as detected by affinity purification. Aggregates of Sup35NM tagged with His6 were purified from yeast extracts using Ni2+ resin (“Pull-down”). Co-purified proteins were identified by Western blot using respective antibody. “Input” – total lysates.

G. Deletion of ZUO1 or SSZ1 leads to an increase in the average and minimal size of Sup35 polymers in both strong and weak [PSI+] variants, as determined by semi-denaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE), followed by a Western blot. Experiment was repeated three times with independent cultures, producing similar results.

We have also observed that the ratio of ribosome-bound versus cytosolic Ssb is influenced not only by the RAC disruption but by the growth conditions as well. In particular, the wild type culture grown in synthetic medium (SC) contained more Ssb in the top (cytosolic) fraction (Fig. 4E), compared to the wild type culture grown in rich organic medium, YPD (Fig. 4AB). It is possible that the release of a portion of Ssb into cytosol during growth on the poor synthetic medium is related to the decreased intensity of protein biosynthesis in these conditions.

Binding of Ssa to Sup35 amyloids is decreased in cells with RAC deficiencies

To measure chaperone binding to prion aggregates, we transformed [PSI+] strains with a plasmid that expressed the Sup35 prion domain and middle region, tagged with His6 (Sup35NM-His), and isolated His-tagged Sup35NM from cell extracts by using Ni2+ resin. The co-isolation of full-size Sup35 together with His-tagged Sup35NM (Fig. 4F) confirms that our approach pulls down Sup35 prion aggregates. Ssb protein was not co-isolated with Sup35NM and Sup35 at detectable levels, indicating that Ssb does not form a stable complex with the Sup35 prion (Fig. 4F). This was true for both wild type and the zuo1 or ssz1Δ strains. In contrast, Ssa was co-isolated with Sup35NM and Sup35, confirming previous reports that Ssa binds to the Sup35 prion aggregates (Allen et al, 2005; Bagriantsev et al, 2008). Remarkably, the amount of Ssa bound to Sup35/Sup35NM was significantly decreased in zuo1Δ or ssz1Δ extracts, as compared to wild type extracts (Fig. 4F). This shows that RAC deficiencies interfere with binding of Ssa to the Sup35 prion.

Notably, the size of the Sup35 prion aggregates, as determined by semi-denaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis, or SDD-AGE (Bagriantsev et al, 2006), was increased in zuo1Δ and ssz1Δ strains, as compared to isogenic and “isoprionic” wild type strains (Fig. 4G). This is consistent with the polymer fragmentation defect, expected in the case of decreased Ssa binding. Decrease in the number of prion seeds due to a fragmentation defect can explain the increased mitotic loss of [PSI+], that was detected in our experiments (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2B-D).

Increased [PSI+] loss in physiological conditions favoring a release of Ssb into the cytosol

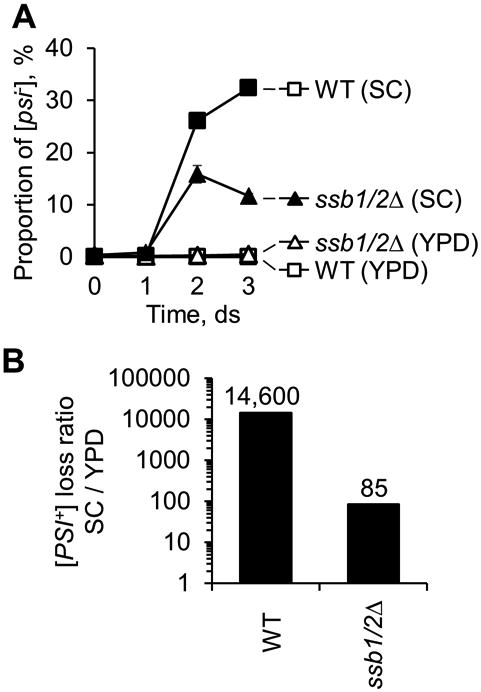

In order to determine if observed effects of Ssb release on [PSI+] are physiologically relevant, we have compared [PSI+] maintenance during growth in rich organic (YPD) medium, where most of Ssb is ribosome-associated, to [PSI+] maintenance during growth in relatively poor synthetic (SC) medium, where a significant fraction of Ssb is released into cytosol (see above, Fig. 4C). Isogenic wild type and ssb1/2Δ strains used in these experiments contained one and the same weak [PSI+] variant. Spontaneous [PSI+] loss in the wild type strain was increased at more than 104-fold in the SC medium, compared to YPD (Fig. 5AB). While the ssb1/2Δ strain accumulated somewhat higher proportion of [psi-] cells in YPD medium (5 × 10-3 after 3 days of incubation), compared to the wild-type strain (6 × 10-4), the ssb1/2Δ strain exhibited lower frequency of [PSI+] loss during growth in SC, compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 5A). If normalized by the number of generations, the acceleration of [PSI+] loss by growth in SC versus growth in YPD was about 170 times more efficient in the wild type strain than in the ssb1/2Δ strain (Fig. 5B). These data show that the increased loss of [PSI+] prion during growth in poor synthetic medium is, in a significant part, Ssb-dependent.

Figure 5. Effects of growth conditions on [PSI+] loss.

A. Spontaneous loss of the weak [PSI+] variant is increased during growth in the liquid poor synthetic medium (SC), compared to the rich organic medium (YPD). This effect is significantly more pronounced in the ssb1/2Δ strain, compared to the wild type (WT) strain. For each strain, at least three independent repeats were performed, with at least 300 colonies (typically more) scored per each time point for each repeat. Standard errors of mean are shown, except for the cases when they were smaller than the size of the symbol.

B. Ratios between the frequencies of [psi-] colonies in the SC and YPD media for the WT and ssb1/2Δ strains. For determining these ratios, the average frequencies, observed on the 3rd day of incubation in the experiment, shown in panel A, were first normalized by the average number of generations for each strain in each medium. Then, a normalized frequency obtained for the given strain in SC was divided by a normalized frequency, obtained for the same strain in YPD.

Discussion

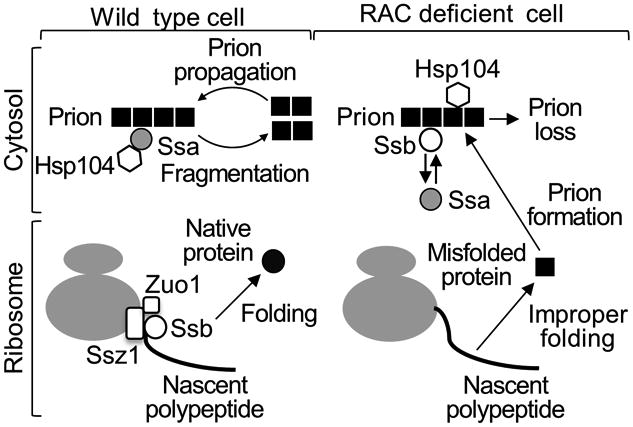

Overall, our data demonstrate that RAC deficiencies increase de novo formation of the [PSI+] prion but antagonize prion propagation. Both effects are mediated by the change in localization of the Ssb chaperone, as double ssb1/2Δ deletion increases [PSI+] formation up to the same level as does zuo1Δ (Fig. 1), and reverses the [PSI+] propagation defect in the RAC deficient strains (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2A). Ribosome-associated Ssb is involved in cotranslational protein folding (James et al, 1997), and removal of Ssb results in accumulation of misfolded aggregating proteins (Willmund et al, 2013). This explains the increased formation of prion aggregates in the RAC deficient strains. Impairment of [PSI+] propagation should, however, depend on the relocation of Ssb to the cytosol rather than the absence of Ssb from the ribosome per se, as such impairment is reversed by the ssb1/2Δ deletion (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2A). The key to understanding the mechanism of such an effect is a reduction of the prion-bound fraction of the cytosolic chaperone Ssa in the RAC defective strains (Fig. 4F). The Ssa chaperone is involved in fragmentation and propagation of a prion (for review, see Liebman & Chernoff, 2012). Apparently, cytosolic Ssb outcompetes Ssa for binding to prion aggregates. However, Ssb is only able to transiently interact with aggregates, and is incapable of cooperating with Hsp104 in aggregate fragmentation (see model on Fig. 6). Indeed, only traces of Ssb were previously found in Sup35 prion aggregates (Bagriantsev et al, 2008), and our results confirm that Ssb is not co-purified with Sup35 aggregates even in RAC deficient strains (Fig. 4F). The ability of excess Ssa to counteract [PSI+] destabilization in RAC deficient strains (Fig. 3A) also agrees with the notion that cytosolic Ssb antagonizes a prion via competition with Ssa. Notably, Ssb overproduction leads to an increase in the cytosolic fraction of Ssb (Fig. S3G), and the [PSI+]-destabilizing effect of excess Ssb is enhanced by RAC deficiencies but counteracted by excess Ssa (Fig. 3). This suggests that the ability of excess Ssb to antagonize [PSI+] propagation is at least in part due to an accumulation of the cytosolic Ssb fraction, which competes with Ssa. As propagation of most known yeast prions involves the Hsp104/70/40 machinery, it is likely that the antagonistic interactions between Ssb and Ssa may influence prions other than [PSI+].

Figure 6. Model for the effects of RAC and Ssb on [PSI+] formation and propagation.

In the wild type strain (left half), Ssb (empty circle) is predominantly associated with translating ribosomes via RAC, composed of Ssz1 (larger empty rectangle) and Zuo1 (smaller empty square), and promotes proper folding of a nascent polypeptide. In cytosol, Ssa (solid grey circle) binds prion aggregates (solid black squares) and Hsp104 (empty hexagon), promoting efficient aggregate fragmentation and prion propagation. In cells where RAC is disrupted (right half), nascent polypeptide is frequently misfolded due to a lack of Ssb on the ribosome, and serves as a substrate for prion formation. At the same time, Ssb is accumulated in cytosol and counteracts binding of Ssa to prion aggregates. Hsp104 interaction with aggregates in the absence of Ssa results in non-productive pathway and destabilization of the prion.

Importantly, our data show that the release of at least a portion of Ssb from the ribosome to the cytosol can be stimulated not only by RAC deficiencies, but also by certain changes in physiological conditions. For example, cells growing in poor synthetic medium show more Ssb in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 4E), as compared to cells grown in rich organic medium (Fig. 4AB). Apparently, physiological increase in cytosolic Ssb has an impact on prion propagation, as a weak variant of [PSI+] is destabilized during growth in the synthetic medium, and this destabilization is significantly less severe in the strain lacking Ssb (Fig. 5). Thus, the regulatory mechanism based on the Ssb release from the ribosome and competition between the Ssa and Ssb chaperones for the cytosolic substrates reflects certain aspects of the physiological regulation of protein folding and aggregation rather than representing a by-product of the mutational alteration of RAC.

The SSB genes are coregulated with the ribosomal protein genes, and their expression is decreased in unfavorable conditions when protein synthesis is slowed down (Lopez et al, 1999). Typically, downregulation of overall protein biosynthesis is accompanied by increased synthesis of specific proteins involved in adaptation to respective conditions. Chaperone imbalance and shortage of Ssb could make such proteins prone to misfolding and potentially, to prion formation. It is possible that changes in the intracellular localization of Ssb represent a general mechanism modulating aggregate formation in response to physiological conditions.

Our results implicate RAC and Ssb as components of the cellular machinery aimed at protecting cells from potentially toxic self-perpetuating protein aggregates. This machinery acts both at the level of the initial aggregate formation and at the level of aggregate propagation. In the latter case, the Ssb-based machinery provides a complement to the other aggregate-defense system, recently identified on the basis of the effects of endosome-associated proteins Btn2 and Cur1 on the other yeast prion, [URE3] (Wickner et al, 2014). It is an intriguing possibility that an antagonistic effect of cytosolic Ssb on prion propagation may partly compensate for the increased prion formation in conditions when the proportion of ribosome-bound Ssb is decreased, thus generating a chaperone-based feedback circuit that prevents accumulation of self-perpetuating protein aggregates (Fig. 6). Although the Ssb subfamily per se is specific to fungi (Peisker et al, 2010), RAC and ribosome-associated Hsp70s functionally analogous to Ssb are found in human cells (Jaiswal et al, 2011), indicating that RAC-dependent chaperone-based circuit regulating protein aggregate abundance is likely not restricted to yeast.

Experimental Procedures

Yeast strains and plasmids

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains constructed in this work (Table S1) were derived from the isogenic haploid derivatives of the strain GT81 (Chernoff et al, 2000), having the genotype ade1−14 (UGA) his3 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3. Complete gene deletions were constructed by one-step replacement with cassettes bearing the HIS5 gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe, an ortholog of S. cerevisiae HIS3 (Longtine et al, 1998). Strains with double and triple deletions were constructed by mating isogenic (except for deletions) haploid MATa and MATα strains, followed by sporulation and dissection. The presence of each deletion was confirmed by PCR with primers specific for flanking regions. For details of strain descriptions, as well as for origin and construction of the S. cerevisiae - E. coli shuttle plasmids used in this work, see Supplementary Material and Methods.

Growth conditions and phenotypic assays

Standard yeast media and protocols were used (Sherman, 2002). Rich organic medium (YPD) contained 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone and 2% dextrose (glucose). Synthetic complete medium (SC) contained 0.17% Yeast nitrogen base without amino acids or ammonium sulfate, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 2% glucose and 13 nutrition supplements (adenine, arginine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, tyrosine, uracil and valine), in the concentrations from 20 to 200 mg L-1, as specified in (Sherman, 2012). Synthetic drop out media are designated by the supplements that are missing (e. g., -Ade for the synthetic medium lacking adenine). The PGAL promoter was induced on solid medium containing 2% galactose instead of glucose, or in liquid synthetic medium containing 2% galactose and 2% raffinose instead of glucose. The PCUP1 promoter was induced by supplementing appropriate solid or liquid medium with 100 μM of CuSO4. Yeast cultures were incubated at 30°C, unless specifically indicated otherwise. The presence of a “strong” [PSI+] variant was detected by a white color of colonies on YPD and fast (two-three days) growth on -Ade medium as a result of the ade1-14 (UGA) reporter readthrough; the presence of a “weak” [PSI+] variant was detected by a pink color of colonies on YPD and slow (seven to ten days) growth on -Ade medium; [psi-] strains were identified by a red color on YPD and by the inability to grow on -Ade after two weeks of incubation (see Chernoff et al, 2002 for more detail). To detect [PSI+] curing by excess Hsp104 in the plate assay, cultures were replica plated from galactose medium onto -Ade/glucose medium selective for the plasmid. To quantify [PSI+] curing by excess Hsp104, yeast cultures bearing the galactose-inducible HSP104 were grown in liquid synthetic medium with galactose and raffinose. Aliquots were plated after specified periods of time onto synthetic medium with glucose selective for the respective plasmid. Presence of [PSI+] in the resulting colonies was detected after replica plating onto YPD and -Ade media. To quantify [PSI+] stability at normal levels of Hsp104 on plates, single colonies from YPD or synthetic medium (when strains were transformed with plasmids) were streaked on YPD, and proportions of red ([psi-]), mosaic ([PSI+]/[pin-]), and white or pink ([PSI+]) colonies were calculated. To quantify [PSI+] loss in the liquid YPD and SC media, yeast cells were grown with shaking shaking at 30°C, with periodic dilutions in order to keep cultures within the exponential growth phase, and plated onto YPD medium at specified time points. Resulting colonies were scored by color, and proportions of red ([psi-]) and pink ([PSI+]) colonies were calculated (mosaic colonies were rare in these experiments). Numbers of generations were determined by comparing OD measurements.

To confirm that the Ade+ phenotype is due to [PSI+], the assay for curability by GuHCl has been performed. For this purpose, yeast cells were grown for 3 passages (roughly 20-40 generation) on the solid YPD medium containing 5 mM (for the wild type strains) or 1-2 mM (for the zuo1Δ, ssz1Δ and ssb1/2Δ strains) of GuHCl, and then streaked out on YPD medium without GuHCl. Loss of the Ade+ phenotype was detected by color (red versus pink or white) and wherever necessary, by growth after velveteen replica plating the YPD plates to –Ade medium. Lower concentration of GuHCl was used for the RAC-deficient strains compared to wild type strains, because zuo1Δ and ssz1Δ strains do not grow on the YPD medium containing 5 mM GuHCl, similar to what has previously been reported by us for the ssb1/2Δ strains (Chernoff et al, 1999).

Protein analysis

For protein isolation, yeast cultures were grown in 10 ml of the appropriate liquid medium to OD600 between 1.0 and 1.5, were precipitated by centrifugation, and were transferred to 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes, washed twice with water and resuspended in 200 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 1× Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail from Roche, 3 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride). Cells were disrupted by agitation with an equal volume of glass beads for 5 min total, with periodic cooling of the mixture on ice. Cell debris was spun down at 4000 g for 2 min, and the supernatant was used for electrophoresis and Western analysis as described below.

For separation of prion aggregates by semi-denaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis, or SDD-AGE (Bagriantsev et al, 2006), yeast extracts were incubated with 1/4 volume of 4× loading buffer (240 mM tris-HCl pH 6.8, 8% SDS, 40% glycerol, 12% 2-mercaptoethanol and 0.002% bromophenol blue) at room temperature for ten minutes, and run in 1.8% TAE-based agarose gel with 0.1% SDS followed by protein transferred to a nitrocellulose Protran membrane (Whatman) by capillary blotting. Membranes were reacted to appropriate antibodies after preblocking in 5% milk.

For denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western analysis, protein samples were mixed with the loading buffer, as described above, boiled in a water bath for ten minutes, and run on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel with 4% stacking gel in Tris-Glycine-SDS running buffer (25 mM tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3), followed by electrotransfer to a Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham) and probing with the appropriate antibody.

For sucrose density gradient centrifugation, cells were collected and disrupted as described above, except for using a gradient buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 1× Complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail from Roche, 3 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride, 100 μg/ml of cycloheximide). 100 μl of a protein extract containing 30-50 μg of total protein as measured by Bradford assay were loaded on a sucrose cushion composed of 100 μl of 20%, 300 μl of 30%, and 200 μl of 40% sucrose in the gradient buffer. Samples were centrifuged in 1.4 ml (11 × 34 mm) thick wall polycarbonate tubes, using TLS-55 rotor on a Optima TLX-120 ultracentrifuge (Beckman) at 259,000 g for 80 min. Fractions of 200 μl each were collected beginning from the top of the gradient; the solid pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of gradient buffer. Equal amount of samples were prepared, resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and analyzed by western blotting as described above.

To destroy polysomes, RNAse A was added to samples prior to loading on the sucrose cushion to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml followed by incubation on ice for 30 minutes. Control samples were incubated on ice without RNAse for the same amount of time.

To purify His6-tagged Sup35, yeast cultures were transformed with the Sup35NM-His6 construct and grown in synthetic medium, selective for the plasmid and supplemented with 100 μM CuSO4, to OD600 of 1.0. Cells were disrupted as for the gradient experiment and about 100 μg of total protein were incubated with 0.3 ml of Ni-NTA Superflow agarose (QIAGEN) at 4°C for 1 hour followed by cleaning the column with 5 ml of washing buffer (25 mM tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM imidazole, 100 μg/ml cycloheximide) and elution of proteins in 300 μl of washing buffer with 300 mM imidazole.

Antibodies

Antibodies to the C-terminal part of Sup35, M region of Sup35, Hsp104, Hsp70s (Ssa and Ssb), Hsp40s (Ydj1 and Sis1) and Rpl3 were kindly provided by Drs. D. Bedwell, I. Vorberg, S. Lindquist, E. Craig, D. Cyr, and J. Warner, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least in triplicate. The mean and standard errors of mean or proportion are shown on graphs as indicated. Differences were considered statistically significant if p<0.05 according to Student’s t-test (McDonald, 2009).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Bedwell, E. Craig, D. Cyr, S. Lindquist, I. Vorberg and J. Warner for antibodies, K. Bruce, P. Chandramowlishwaran, T. Chernova, N. Romanova, A. Romanyuk, M. Sun, R. Wegrzyn and K.D. Wilkinson for strain/plasmid constructions and helpful discussion. This work was supported in parts by the grant MCB-1024854 from NSF and project 1.50.2218.2013 from St. Petersburg State University to Y.O.C., by the subaward to Y.O.C. on the NIH grant R01GM093294 (to K.D. Wilkinson), and by Petit Undergraduate Research Scholarship from Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience to M.M.M.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- Alberti S, Halfmann R, King O, Kapila A, Lindquist S. A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. Cell. 2009;137:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KD, Wegrzyn RD, Chernova TA, Muller S, Newnam GP, Winslett PA, et al. Hsp70 chaperones as modulators of prion life cycle: novel effects of Ssa and Ssb on the Saccharomyces cerevisiae prion [PSI+] Genetics. 2005;169:1227–1242. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.037168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagriantsev SN, Gracheva EO, Richmond JE, Liebman SW. Variant-specific [PSI+] infection is transmitted by Sup35 polymers within [PSI+] aggregates with heterogeneous protein composition. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2433–2443. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagriantsev SN, Kushnirov VV, Liebman SW. Analysis of amyloid aggregates using agarose gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 2006;412:33–48. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)12003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchsenius AS, Müller S, Newnam GP, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Chernoff YO. Prion variant maintained only at high levels of the Hsp104 disaggregase. Curr Genet. 2006;49:21–29. doi: 10.1007/s00294-005-0035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacinska A, Szczesniak B, Kochneva-Pervukhova NV, Kushnirov VV, Ter-Avanesyan MD, Boguta M. Ssb1 chaperone is a [PSI+] prion-curing factor. Curr Genet. 2001;39:62–67. doi: 10.1007/s002940000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff YO, Derkach IL, Inge-Vechtomov SG. Multicopy SUP35 gene induces de-novo appearance of psi-like factors in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1993;24:268–270. doi: 10.1007/BF00351802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff YO, Galkin AP, Lewitin E, Chernova TA, Newnam GP, Belenkiy SM. Evolutionary conservation of prion-forming abilities of the yeast Sup35 protein. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:865–876. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff YO, Lindquist SL, Ono B, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW. Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [psi+] Science. 1995;268:880–884. doi: 10.1126/science.7754373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff YO, Newnam GP, Kumar J, Allen K, Zink AD. Evidence for a protein mutator in yeast: role of the Hsp70-related chaperone Ssb in formation, stability, and toxicity of the [PSI] prion. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8103–8112. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff YO, Uptain SM, Lindquist SL. Analysis of prion factors in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2002;351:499–538. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)51867-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernova TA, Wilkinson KD, Chernoff YO. Physiological and environmental control of yeast prions. FEMS Microbiol Revs. 2014;38:326–344. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coustou V, Deleu C, Saupe S, Begueret J. The protein product of the het-s heterokaryon incompatibility gene of the fungus Podospora anserina behaves as a prion analog. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9773–9778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BS. ψ, a cytoplasmic suppressor of super-suppressor in yeast. Heredity. 1965;20:505–521. [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Hong JY, Liebman SW. Prions affect the appearance of other prions: the story of [PIN+] Cell. 2001;106:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Zhou P, Chernoff YO, Liebman SW. Genetic and environmental factors affecting the de novo appearance of the [PSI+] prion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;147:507–519. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch IL, Chernoff YO, Kushnirov VV, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW. Genesis and variability of [PSI] prion factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;144:1375–1386. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Park KW, Yu H, Fan Q, Li L. Newly identified prion linked to the chromatin-remodeling factor Swi1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Genet. 2008;40:460–465. doi: 10.1038/ng.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaglestone SS, Ruddock LW, Cox BS, Tuite MF. Guanidine hydrochloride blocks a critical step in the propagation of the prion-like determinant [PSI+] of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:240–244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Jucker M. The amyloid state of proteins in human diseases. Cell. 2012;148:1188–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautschi M, Lilie H, Funfschilling U, Mun A, Ross S, Lithgow T, et al. RAC, a stable ribosome-associated complex in yeast formed by the DnaK-DnaJ homologs Ssz1p and zuotin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3762–3767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071057198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann R, Lindquist S. Epigenetics in the extreme: prions and the inheritance of environmentally acquired traits. Science. 2010;330:629–632. doi: 10.1126/science.1191081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann R, Wright JR, Alberti S, Lindquist S, Rexach M. Prion formation by a yeast GLFG nucleoporin. Prion. 2012;6:391–399. doi: 10.4161/pri.20199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DL, Lancaster AK, Lindquist S, Halfmann R. Heritable remodeling of yeast multicellularity by an environmentally responsive prion. Cell. 2013;153:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Gautschi M, Walter W, Rospert S, Craig EA. The Hsp70 Ssz1 modulates the function of the ribosome-associated J-protein Zuo1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:497–504. doi: 10.1038/nsmb942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal H, Conz C, Otto H, Wolfle T, Fitzke E, Mayer MP, Rospert S. The chaperone network connected to human ribosome-associated complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1160–1173. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00986-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P, Pfund C, Craig EA. Functional specificity among Hsp70 molecular chaperones. Science. 1997;275:387–389. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Song Y, Chung S, Masison DC. Propagation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae [PSI+] prion is impaired by factors that regulate Hsp70 substrate binding. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3928–3937. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3928-3937.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AC, Wickner RB. Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a sexy yeast with a prion problem. Prion. 2013;7:215–220. doi: 10.4161/pri.24845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirov VV, Kryndushkin DS, Boguta M, Smirnov VN, Ter-Avanesyan MD. Chaperones that cure yeast artificial [PSI+] and their prion-specific effects. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1443–1446. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00802-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman SW, Chernoff YO. Prions in yeast. Genetics. 2012;191:1041–1072. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.137760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A, 3rd, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez N, Halladay J, Walter W, Craig EA. SSB, encoding a ribosome-associated chaperone, is coordinately regulated with ribosomal protein genes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3136–3143. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3136-3143.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH. Handbook of Biological Statistics. Sparky House Publishing; Baltimore, Maryland: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McGlinchey RP, Kryndushkin D, Wickner RB. Suicidal [PSI+] is a lethal yeast prion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5337–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102762108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RJ, Ziegelhoffer T, Nicolet C, Werner-Washburne M, Craig EA. The translation machinery and 70 kd heat shock protein cooperate in protein synthesis. Cell. 1992;71:97–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90269-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newnam GP, Wegrzyn RD, Lindquist SL, Chernoff YO. Antagonistic interactions between yeast chaperones Hsp104 and Hsp70 in prion curing. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1325–1333. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nizhnikov AA, Antonets KS, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Derkatch IL. Modulation of efficiency of translation termination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Prion. 2014;8:247–260. doi: 10.4161/pri.29851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KW, Hahn JS, Fan Q, Thiele DJ, Li L. De novo appearance and “strain” formation of yeast prion [PSI+] are regulated by the heat-shock transcription factor. Genetics. 2006;173:35–47. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.054221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel BK, Gavin-Smyth J, Liebman SW. The yeast global transcriptional co-repressor protein Cyc8 can propagate as a prion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:344–349. doi: 10.1038/ncb1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paushkin SV, Kushnirov VV, Smirnov VN, Ter-Avanesyan MD. Propagation of the yeast prion-like [psi+] determinant is mediated by oligomerization of the SUP35-encoded polypeptide chain release factor. EMBO J. 1996;15:3127–3134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peisker K, Chiabudini M, Rospert S. The ribosome-bound Hsp70 homolog Ssb of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB. Biology and genetics of prions causing neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Genet. 2013;47:601–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy M, Masison DC. Modulation and elimination of yeast prions by protein chaperones and co-chaperones. Prion. 2011;5:245–249. doi: 10.4161/pri.5.4.17749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogoza T, Goginashvili A, Rodionova S, Ivanov M, Viktorovskaya O, Rubel A, Volkov K, Mironova L. Non-Mendelian determinant [ISP+] in yeast is a nuclear-residing prion form of the global transcriptional regulator Sfp1. Proc Natl Aca Sci USA. 2010;107:10573–10577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005949107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satpute-Krishnan P, Langseth SX, Serio TR. Hsp104-dependent remodeling of prion complexes mediates protein-only inheritance. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:3–41. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50954-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorter J, Lindquist S. Hsp104, Hsp70 and Hsp40 interplay regulates formation, growth and elimination of Sup35 prions. EMBO J. 2008;27:2712–2724. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki G, Shimazu N, Tanaka M. A yeast prion, Mod5, promotes acquired drug resistance and cell survival under environmental stress. Science. 2012;336:355–359. doi: 10.1126/science.1219491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Collins SR, Toyama BH, Weissman JS. The physical basis of how prion conformations determine strain phenotypes. Nature. 2006;442:585–589. doi: 10.1038/nature04922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipton KA, Verges KJ, Weissman JS. In vivo monitoring of the prion replication cycle reveals a critical role for Sis1 in delivering substrates to Hsp104. Mol Cell. 2008;32:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilardell J, Warner JR. Ribosomal protein L32 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae influences both the splicing of its own transcript and the processing of rRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1959–1965. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegrzyn RD, Bapat K, Newnam GP, Zink AD, Chernoff YO. Mechanism of prion loss after Hsp104 inactivation in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4656–4669. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4656-4669.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner RB. [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1994;264:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.7909170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner RB, Bezsonov E, Bateman DA. Normal levels of the antiprion proteins Btn2 and Cur1 cure most newly formed [URE3] prion variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E2711–2720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409582111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmund F, del Alamo M, Pechmann S, Chen T, Albanese V, Dammer EB, et al. The cotranslational function of ribosome-associated Hsp70 in eukaryotic protein homeostasis. Cell. 2013;152:196–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler J, Tyedmers J, Bukau B, Mogk A. Hsp70 targets Hsp100 chaperones to substrates for protein disaggregation and prion fragmentation. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:387–404. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201201074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.