Abstract

Patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) often develop a spectrum of cognitive symptoms that can evolve into dementia. Dopamine (DA) replacement medications, though improving motor symptoms, can exert both positive and negative effects on cognitive ability, depending on the severity of the disease and the specific skill being tested. By considering the behavioral and clinical aspects of disease- and treatment-mediated changes in cognition alongside the pathophysiology of PD, an understanding of the factors that govern the heterogeneous expression of cognitive impairment in PD is beginning to emerge. Here, we review the neuroimaging studies revealing the neural correlates of cognitive changes after DA loss and DA replacement as well as those that may accompany the conversion from milder stages of cognitive impairment to frank dementia.

Keywords: PET, fMRI, cognition, executive functions, PD

Cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease (PD) can be characterized by heterogeneity, with impairments manifesting in one or multiple cognitive domains.1 The concept of mild cognitive impairment in PD (PD-MCI) was recently formalized,2 with diagnosis being reached after impairments on neuropsychological tasks become significant in at least one domain. Table 1 summarizes the types and prevalence of cognitive impairments observed in PD. Interest in the clinical characteristics and underlying neurobiology of PD-MCI has intensified in recent years because of the potential that it may represent the early stage of a progressive dementing process. Recently, it has been proposed that the relationship between PD-MCI and PD dementia (PDD) may not be linear. Whereas there is evidence to uniquely link executive deficits,3,4 visuospatial deficits,5 and memory4 with the development of PDD, it has also been suggested that two distinct mild cognitive syndromes exist, each carrying a different prognosis for PDD.6,7 The first of these putative syndromes affects mainly frontostriatal executive deficits that modulate with dopaminergic medications and genetically determined levels of prefrontal cortex (PFC) dopamine (DA). The second affects more-posterior cortical abilities, such as visuospatial and memory functions, and it is this syndrome that is suggested to be associated with an increased risk for conversion to dementia.7 Neuroimaging methods have contributed to the study of cognitive impairments as they relate to both DA-mediated changes in executive skills and the factors that govern the conversion from PD-MCI to dementia. Thus, one set of questions are concerned with understanding the role of DA deficiency and DA replacement medications in early executive-type cognitive impairments. Another set can be summarized as the study of the neural basis, or neural correlates, of PD-MCI and whether these are prodromal for PDD. We will broadly review the literature from these two overlapping themes below, after a brief overview of the types of information that can be gathered using neuroimaging methods.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of impairment in three cognitive domains

| Cognitive Domain | Mean Percentage Prevalence Across Seven Centers (1,346 PD Patients Without Dementia) (%) |

|---|---|

| Memory impairment | 13.3 |

| Visuospatial impairment | 11.0 |

| Attention/executive impairment | 10.1 |

Seven centers contributed data from 1,346 patients. Impairment was defined as performance below 1.5 standard deviations of control data or healthy population means. The majority of the patients had impairment in only one domain. Data adapted from Aarsland et al. (2011).1

Neuroimaging Techniques in the Study of Cognitive Decline in PD

The multifactorial pathophysiological processes that lead to cognitive decline in PD can be visualized with neurochemical, functional, and structural neuroimaging methods. PET and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) use targeted ligands to tell us about neurotransmitter levels or receptor densities in particular brain regions. As described in more detail below, these have been particularly useful not only for assessing the nigrostriatal system, but also the mesolimbic and mesocortical DA systems, as well as non-DA neurotransmitter systems (most notably, the cholinergic pathways) and how their degeneration may influence cognitive skills. PET can also be used to determine brain-glucose metabolism, an index of functional integrity, which has revealed covarying patterns of brain activity associated with PD-MCI. The visualization of brain function during cognitive tasks, however, is best achieved with functional MRI (fMRI), which is sensitive to the blood-oxygen–level dependent (BOLD) response that occurs in discreet brain regions during periods of activity. fMRI has revealed areas of both over- and underactivity during cognitive tasks in patients with PD, suggesting the combined presence of decreased brain function and compensatory mechanisms. Structural MRI can be used to measure changes in gray-matter volume, revealing atrophy in brain regions that can be linked with cognitive decline. White-matter integrity is measured with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and its deterioration is also associated with cognitive decline. Of course, other imaging modalities, such as electroencephalography and magnetoencephalography, have also made significant contributions to the study of cognitive decline in PD, but these are not discussed in the current review.

DA Deficiency and DA Overdose

Executive deficits are ubiquitous in PD.8 They significantly affect quality of life and may even underlie some of the cardinal motor features of PD.9 They include the ability to plan ahead, develop strategies for goal-directed outcomes, initiate and inhibit actions, and make alterations to behavior based on feedback from a changing environment. These abilities depend on accurate processing within topographically organized functional and anatomical connections between the prefrontal cortex and the striatum.10 Neuroimaging data suggest that these functions are damaged by impaired processing of cortical inputs to a DA-deficient striatum, because the severity of impairment is correlated with reduced uptake of presynaptic dopaminergic ligands in the caudate and putamen.11,12 However, executive functions can be worsened or improved by PD, depending on the nature of the task, and DA medication has similarly variable effects. Today, much of our understanding of the mechanisms underlying executive impairment in de novo and medicated PD has been achieved by considering the actions of DA alongside behavioral and clinical reports of the variable effects of disease and treatment on different components of executive tasks.13 Neuroimaging techniques have enabled us to confirm these ideas, as well as to further probe their neural consequences.

Degeneration of mesencephalic DA cells in PD is most severe in the ventral midbrain projecting to the dorsal putamen and dorsal regions of the caudate, whereas the dorsal midbrain, including the ventral tegmental area projecting to the ventral putamen and caudate as well as the nucleus acumbens, are less affected.14 Thus, in unmedicated patients, cognitive tasks that depend on the dorsal striatum and its cortical connections (i.e., motor and premotor cortex, the supplementary motor area, and the dorsolateral PFC ([DLPFC]), are impaired alongside motor control and are improved by DA replacement medications13,15,16 (see Figs. 1 and 2). Using fMRI, levodopa has been shown to normalize activity in the right DLPFC during tasks requiring planning and working memory.17 On the other hand, cognitive skills dependent on corticoventral striatal loops, which include the nucleus accumbens, the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and the inferotemporal cortex, are relatively preserved in unmedicated PD, but DA replacement medications cause impairments resulting from dopaminergic overdose of these circuits13 (see Figs. 1 and 2). This was demonstrated by activity changes resulting from L-dopa specific to the nucleus accumbens during a reversal learning task.18 As well as these treatment-induced imbalances in DA tone in the ventral versus dorsal striatocortical circuits, there is a reciprocal relationship between striatal and cortical DA levels at play.19 Thus, there is a compensatory increase in cortical DA in early PD20 that affects patients’ ability to perform particular cognitive tasks.21,22

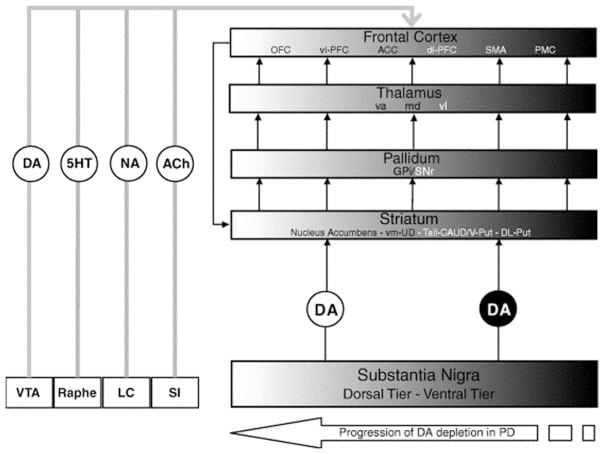

FIG. 1.

Figure and legend taken from Cools (2006).13 Schematic to show the chemical neuropathology in PD. PD is characterized by a spatiotemporal progression of DA cell degeneration from the ventral to the dorsal tier of the midbrain, which also includes the ventral tegmental area (VTA). The black-to-white shading gradient represents the spatiotemporal progression of pathology from dorsal to ventral frontostriatal circuitries over the course of the disease. The severely degenerated ventral tier sends DA projections primarily to the dorsal striatum, which projects to relatively restricted portions of the more-dorsal and lateral parts of the PFC.10 The relatively intact dorsal tier sends its DA projections primarily to the ventral striatum, which projects strongly through the output nuclei of the basal ganglia and the thalamus to medial and lateral OFC (ventrolateral and ventromedial PFC). VTA, ventral tegmental area; Raphé, dorsal and medial raphé nuclei; 5-HT, serotonin; LC, locus coeruleus; NA, noradrenaline; SI, substantia innominata; ACh, acetylcholine; vm-CAUD, ventromedial caudate nucleus; Tail-CAUD, tail of the caudate nucleus; V-Put, ventral putamen; DL-Put, dorsolateral putamen; GPi, internal segment of the GP; SNr, substantia nigra pars reticulata; va, ventral anterior nucleus; md, dorsomedial nucleus; vl, ventrolateral nucleus; vl-PFC, ventrolateral PFC; dl-PFC, dorsolateral PFC; SMA, supplementary motor area; PMC, premotor cortex.

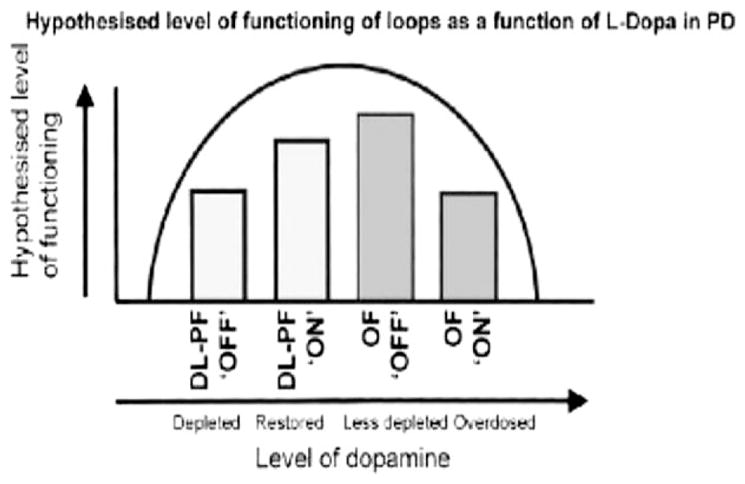

FIG. 2.

The DA “overdose” hypothesis: DA levels are depleted in the dorsolateral prefrontal/posterior parietal loop in patients “off” medication (DL-PF ‘OFF’). DA-ergic medication may partially restore these levels (DL-PF ‘ON’). DA levels are less depleted in the orbitofrontal loop in patients off medication (OF ‘OFF’) and may be “overdosed” by the administration of medication (OF ‘ON”). [Image and legend: Cools R, Barker RA, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Enhanced or Impaired Cognitive Function in Parkinson’s Disease as a Function of Dopaminergic Medication and Task Demands:, Cereb. Cortex (2001) 11 (12): 1136–1143. doi:10.1093/cercor/11.12.1136, by permission of Oxford University Press.]

The neural consequences of both treatment- and disease-mediated increased dopaminergic stimulation of the ventral striatum and cortex, respectively, for cognitive task performance was revealed in a study that plotted BOLD responses to an executive task in the ventrolateral PFC and the caudate against degree of DA deficiency, indexed by motor deficiency.21 Similar performance required greater activation of these regions in patients with mild and severe motor symptoms, relative to those with moderate clinical scores, revealing an inverted U-shape-type relationship between UPDRS and BOLD responses to the task. Thus, performance of the task was impaired in early stages as a result of compensatory increases of dopaminergic stimulation of the frontal cortex in early disease that was above optimal levels for the task at hand and below optimal in later disease stages. This study also demonstrated that circuits closer to the dorsal loops underlying motor symptoms showed less disruption after DA medications in terms of the degree of BOLD response observed for similar task performance. This demonstrates that functions dependent on levels of DA tone very different from that required for effective motor performance will be most effected by dopaminergic restoration.

Although the spatial and temporal patterns of DA denervation in the striatum leading to specific cognitive deficits seem to account for the variability in cognitive response to L-dopa, other findings may need a different explanation. For example, networks involved in motor sequence learning do not include the striatum in PD patients because they do for controls, suggesting that a compensatory increase in involvement in other areas is required.23 It might be predicted, from the above discussion, that underactivity in the striatum during a particular cognitive task in PD patients would indicate that DA restoration would both reinstate striatal involvement and improve task performance. However, L-dopa impairs performance of motor sequence learning in PD.24

Increased and decreased PFC activity during an executive task in PD patients has been shown to depend on the degree by which the caudate is engaged in the task at hand. When the caudate was required during a set-switching task, BOLD activity in the lateral PFC was reduced in PD patients versus controls. On the other hand, when the caudate was not engaged, during maintenance of set, there was an increase in BOLD in the same regions25 (see Fig. 3). Thus, DA deficiency in the caudate resulted in decreased activation of the PFC, specifically when the caudate was engaged, whereas DA dysregulation in the cortex resulted in overactivity, potentially as a compensatory mechanism subsequent to increased dopaminergic tone in the PFC. The investigators posit that their results may also be the result of mesocortical degeneration, resulting in overactivity caused by the loss of DA-mediated “focusing” of PFC neural activity.

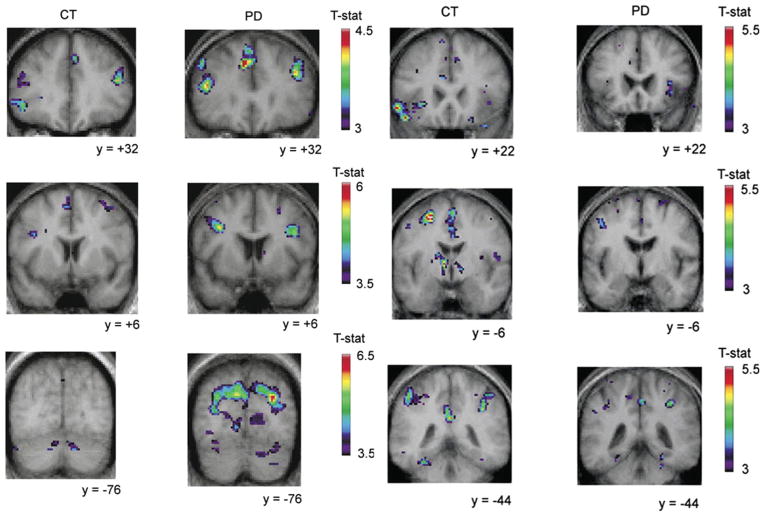

FIG. 3.

Image adapted from Monchi et al. (2007).25 The panels on the left show that Montreal card sorting task (MCTS) (retrieval without shift versus the control condition) did not significantly activate the caudate nucleus and induced significant activation in the left dorsolateral PFC and the right posterior PFC in the PD group (labeled PD), but not in the control group (labeled CT). In contrast, when the caudate was activated by the task (retrieval with shift versus the retrieval without shift condition) (shown in the right panels), significant activation was observed in the left ventrolateral PFC in the control group, whereas none was observed in the PD group. They also show larger activations in the control group than in the patient group in the posterior cingulate cortex and the posterior parietal cortex bilaterally.

Degeneration of mesocortical DA can be assessed by uptake/binding of dopaminergic ligands. Clarifying its role requires measurements of task-induced DA release in PD patients and controls. DA release during cognitive tasks can be measured by displacement of endogenous DA from postsynaptic receptor cites most frequently measured in the striatum using [11C]raclopride, a ligand that binds to DA D2 receptors. Using [11C]raclopride with PET, Sawamoto et al.26 revealed, as expected, reduced DA release in the dorsal caudate during an executive task in PD patients, compared to controls. The study also reported similar changes in [11C]raclopride binding resulting from the task between the groups in the ACC, leading the investigators to conclude that mesocortical DA release is well preserved in PD. However, affinity of [11C]raclopride for DA D2 receptors may preclude accurate measurement of endogenous DA levels in areas beyond the striatum, where receptor levels are low. A more-recent PET study, using [11C]FLB-457, a high-affinity ligand for the DA D2 receptor, found diminished association between binding in the DLPFC and ACC and Montreal Cognitive Assessment in PD patients, as well as a lack of DA release in the OFC during an executive task, as was observed in the control subjects.27 These findings indicate that mesocortical DA is impaired alongside the mesostriatal DA system and plays a role in executive impairments in PD.

As well as the influence of changing DA levels in different brain regions on executive performance in PD, a further layer of complexity is added by the nature of the executive skill being measured. Performance of executive tasks often depends, to different degrees, on two distinct cognitive processes. On the one hand, stable representations of rules, sets, and stimuli must be maintained across similar trial types. This ability can be indexed by measures of maintenance of information in working memory or vulnerability to distractibility and is associated with tonic dopaminergic stimulation of PFC D1 receptors.28 On the other hand, executive skill requires flexibility to shift attention to new stimuli and apply different rules based on new information. This skill is best measured by tasks dependent on cognitive flexibility, such as set shifting, and is associated with phasic dopaminergic stimulation of striatal D2 receptors.29 Thus, coordination between the PFC and striatum is critical for performance of executive tasks, which often depend, to different degrees, on the need for “stability” and “flexibility.”30 Because of the DA-dopamine deficient dorsal striatum alongside a dopamine-replete ventral striatum, as well as a compensatory increase in PFC DA, stability is relatively unimpaired or even improved, compared to controls, in PD.22 On the other hand, flexibility is impaired in PD as a result of DA deficiency in the dorsal striatum.15 When the neuronal activity underlying these abilities are compared between unmedicated PD patients and healthy aged-matched controls, the striatum shows underactivity of transient responses to task stimuli in the caudate nuclei, putamen, and globus pallidus (GP), whereas sustained activity in the PFC is unaffected.30

Presynaptic markers of DA function, such as [18F]fluorodopa (FDOPA), have also revealed regional differences in the role of DA for supporting executive function in the striatum. Beilen et al.31 found that mental flexibility was related to [18F]FDOPA uptake in the putamen, whereas mental organization (i.e., executive memory and fluency) was related to uptake in the caudate. The investigators suggest that mental components of executive functioning versus motor components may depend on DA activity in the caudate and putamen, respectively.

Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia

PD-MCI is increasingly recognised as a feature of PD even in the early stages. The rate of progression from PD-MCI to PDD may depend on the type and severity of cognitive impairment and on other factors, such as genetics, age, and severity of PD motor symptoms. 7 Impairments are reported to be clinically significant in approximately 57% of newly diagnosed PD patients.7 The point prevalence of PDD is reported to be approximately 30% of PD patients.32 Importantly, a diagnosis of PD-MCI is associated with increased risk for the development of PDD,3 suggesting that PD-MCI may represent the early stages of a dementing process, but the rate of decline from PD-MCI to PDD is varied, with 17% progressing after just 5 years.7 In the remainder of the review, we will cover some of the neuroimaging literature attempting to understand the progression of cognitive decline from MCI-PD to PDD.

Pathological data suggest that cognitive decline may be associated with the appearance of abnormal protein aggregates, such as alpha-synuclein (α-Syn) containing Lewy bodies (LB).33 More recently, smaller aggregations of α-Syn have been detected at the presynapse in PD that may be responsible for neurotransmitter decline.34 Unfortunately, it is not yet possible to measure these molecular changes in humans in vivo, but the development of radiolabeled α-Syn for PET imaging of LB will enable a better understanding of the relationship between these molecular changes and clinical heterogeneity in PD cognitive deficits. On the other hand, amyloid deposition, normally associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-type dementia, has been reported on in some pathologically confirmed PDD cases.35 PDD patients also show increased labeling of carbon-labeled Pittsburg compound B ([11C]PiB), generally reflecting fibrillar amyloid beta pathology,36 though is it more common in patients with dementia with LB (?DLB).37 It is thought that the amyloid burden in PD increases the rate of the dementing processes38,39 or the severity of the cognitive impairment.40 The opportunity to measure [11C]PiB uptake and perform activity-related functional neuroimaging scans, such as fMRI, [15O]H20 PET and [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) has suggested that there may be a relationship between brain networks that dominate during rest, described as a default mode network, and [11C]PiB binding in AD,41 though this work is yet to be extended to PD patients.

Potentially, as a result of these abnormal protein aggregates, or as additive contributors to cognitive decline, PDD patients show decreased neurotransmitter activity, altered metabolic activity, and increased brain atrophy. Neuroimaging may also be able to detect these changes in the earlier stages of a dementing process and may therefore provide a biomarker for identifying patients at risk for PDD, provided that brain images are collected within large-scale longitudinal designs alongside extensive neuropsychological testing. Most important, such biomarkers will be invaluable for understanding the affects of future disease- modifying agents that target the formation of protein aggregates.42

Traditionally, many of the changes in the brain that can be linked with serious cognitive decline have been identified only after a diagnosis of dementia has already been reached. For example, early pathological data revealed that patients with PDD had a severe, widespread cholinergic deficit that correlated with the degree of cognitive impairment.43 More recently, the cholinergic deficit in PDD patients has been surveyed using N-11C-methyl-4-piperidyl acetate ([11C]MP4A) or N-[(11)C]methyl-piperidin-4-yl propionate ([11C]PMP) and PET, markers for acetylcholinersterase (AChE) activity. Bohnen et al., in 2003,44 found a more-severe cholinergic deficit in PDD than in AD. Later, these investigators found more-severe cholinergic degeneration in PDD than in PD and reported a correlation between executive and attentional skills and cortical [11C]PMP binding.45 Others have performed [11C]MP4A scans alongside other radiotracers. Klein et al.43 used [11C]MP4A with [18F]FDOPA (an extensively used tracer for presynaptic dopaminergic function) and [18F]FDG (a widely used marker for neuronal metabolism). However, cortical uptake of [18F]FDOPA may not be a reliable indicator of cortical DA because of a low signal-to-noise ratio.46 Klein et al.43 and Hilker et al.47 did, however, find reduced [11C]MP4A uptake across the entire cortex, but most notably in posterior regions.

Presynaptic dopaminergic function can be measured using I-n-fluoropropyl-2b-carbomethoxy-3b-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane (18F-FP-CIT) and PET. Song et al.48 found similar uptake in PD patients with and without dementia. However, as discussed above, dopaminergic degeneration in the striatum does contribute to cognitive deficits in nondemented PD. For example, uptake in the caudate of 2b-carbomethoxy-3b-(4-iodophenyl) tropane (b-CIT), another ligand with high affinity for DA transporters (DATs), measured with SPECT, was associated with executive function, but not memory, and was correlated with reduced metabolic activity in the DLPFC and ACC.12 The latter findings imply that DA deficiency in the striatum impairs frontal function, most likely through reduced basal ganglia-thalamocortical outflow, with a specific effect on frontally based executive functions. Taken together with the similar striatal DA deficit in PD and PDD reported on by Song et al.,48 this suggests that reduced striatal DA does affect executive skills, but is unlikely to be part of the pathophysiological process leading to dementia.

In the Klein et al.43 study discussed above, cholinergic degeneration in PDD patients measured with [11C]MP4A was spatially congruent (i.e., changes being greater in posterior cortical regions) with the metabolic changes measured with [18F]FDG (see Fig. 4). The investigators suggest that this may indicate deafferentation of cholinergic projection fibers of the basal forebrain in PDD, but not in PD, potentially as a result of increased LB load in this region. This study demonstrates the interdependence of imaging biomarkers, and such multitracer studies will be necessary for an integrated understanding of the pathophysiology of cognitive decline. Importantly, the frontal-posterior gradient of reduced metabolism has also been noted in patients with PD-MCI,49 suggesting that this pattern may be useful as an early biomarker for PDD. Furthermore, if the spatial overlap between cholinergic degeneration and [18F]FDG in PDD is the result of a common mechanism, cholinergic degeneration may also underlie early cognitive changes. Indeed, global cognitive function was found to correlate with cortical [11C]MP4A uptake in both cognitively healthy and PDD patients,50 and Bohnen et al.51 showed that memory-based and executive deficits correlated with [11C]PMP uptake in PD patients without dementia. This group also reported that rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, a risk factor for the development of cognitive impairment in PD, is associated with cholinergic degeneration.52 A recent study also found that nondemented PD patients with evidence of cholinergic function significantly below the level of healthy controls had worse global cognitive scores than those with healthy AChE activity.53 An important question for future research, then, is whether subtypes of PD-MCI that may be more predictive of a faster rate of conversion to dementia7 are more closely linked with progressive cholinergic degeneration than deficits in other cognitive domains, suggesting that cholinesterase inhibitors may be more or less efficacious in different PD-MCI subtypes.

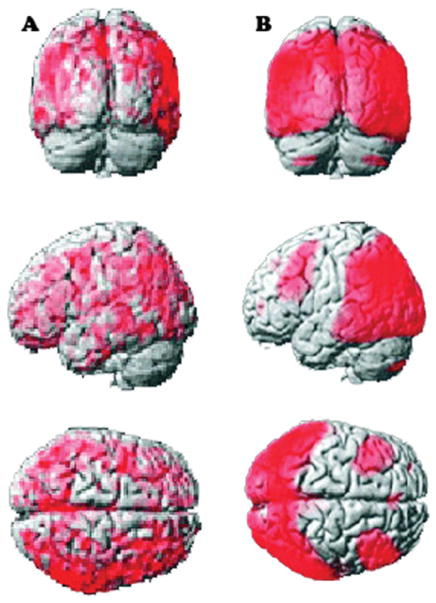

FIG. 4.

Image adapted from Klein et al. (2010).44 (A) Brain areas with significant reduction of [11C]MP4A uptake in PDD versus PD. (B) Brain areas with significant reduction of [18F]FDG uptake PDD versus controls. CMRglc, cerebral metabolic rate of glucose.

Metabolic changes measured with [18F]FDG or less-invasive imaging protocols, such as arterial spin labeling, 54 currently represent the most promising of the neuroimaging tools as a marker for cognitive impairment. In particular, analysis of brain regions in which metabolic changes are covarying has identified a pattern of metabolic changes associated with executive and memory impairments,55 separable from the pattern previously linked to PD motor symptoms.56 This PD cognitive pattern is characterized by metabolic reductions in frontal and parietal association areas associated with relative increases in the cerebellar vermis and dentate nuclei. A later study confirmed this pattern in PD patients, satisfying criteria for PD-MCI, compared to cognitively healthy, PD patients.57 Furthermore, prospective [18F]FDG data in PD patients converting from PD-MCI to PDD have revealed that hypometabolism in the visual association cortex and the posterior cingulate, present even when global cognitive scores are in the healthy range, may herald more-serious cognitive decline.58 However, it must be noted that at the time of the study, there were already differences in cognitive performance in the PD group who did and did not go on to develop PDD. As cognitive decline advanced in the PDD group, widespread cortical and subcortical hypometabolism was evident. Consistent with early involvement of the visual association cortex, over time, this region showed the most prominent increase in hypometabolism.

Brain functional status can also be measured by assessing cerebral blood flow using iodine 123-N-isopropyl-p-iodoamphetamine SPECT. This method was combined with diffusion-weighted imaging to assess the progression patterns of gray- and white-matter abnormalities and functional changes in groups of PD patients with different levels of cognitive impairment. 59 Occipital and posterior parietal hypoperfusion was observed in all patients with PD, as well as widespread white-matter alteration in PD-MCI and PDD. These results suggest that cognitive impairment in PD progresses with functional changes, followed by structural abnormalities.

A recent cross-sectional study confirmed previous work60 suggesting that PDD patients have decreased hippocampal and medial temporal lobe volumes measured using voxel-based morphometry (VBM).61 This study also recruited patients with PD-MCI, who also showed evidence of atrophy in the hippocampus, indicating that accelerated atrophy in this area may be a biomarker available at PD-MCI stages for predicting the conversion to PDD. However, VBM analysis is not able to distinguish between diagnostic entities on an individual patient basis. Thus, the investigators utilized a pattern classification method, already applied in AD patients, that revealed a spatial pattern of atrophy in PD-MCI patients that was similar to PDD patients, and not present in PD patients, characterized by hippocampal, prefrontal cortex gray and white matter, occipital lobe gray and white matter, and parietal lobe white-matter atrophy. Thus, this approach may be useful for detecting atrophy in PD-MCI patients to be used as a biomarker for PDD.

Summary

Executive impairment is common in PD and is likely the result DA deficiency in frontostriatal circuits. However, interpretation of these cognitive deficits must be done within a framework that takes into account baseline DA levels in both the striatum and PFC resulting from disease stage, the effects of exogenous dopaminergic stimulation, and the particular executive skill being examined. Progressive cognitive decline that begins with PD-MCI and often evolves to PDD is associated with degeneration of cholinergic pathways. As noted elsewhere, the current interest in cognitive decline in PD is likely the result of the poor response to treatment of these symptoms.62 The neuroimaging studies reported here provide the ground-work for establishing biomarkers that may be used to identify those patients that are most at risk for PDD, and that will be invaluable for assessing the efficacy of future disease-modifying treatments.

Acknowledgments

Funding agencies: This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP 110962).

Footnotes

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: A.P.S. is supported by the Canada Research Chair program and the E.J. Safra Foundation. N.J.R is supported by the Parkinson Society Canada. Full financial disclosures and author roles may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Aarsland D, Kolbjørn B, Tormod F. Mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2011;11:371–378. doi: 10.1007/s11910-011-0203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litvan I, Aarsland D, Adler CH, et al. MDS Task Force on mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: critical review of PD-MCI. Movement Disorders. 2011;26:1814–1824. doi: 10.1002/mds.23823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janvin CC, Aarsland D, Larsen JP. Cognitive predictors of dementia in Parkinson’s disease: a community-based, 4-year longitudinal study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18:149–154. doi: 10.1177/0891988705277540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy G, Jacobs MD, Tang M, et al. Memory and executive function impairment predict dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17:1221–1226. doi: 10.1002/mds.10280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahieux F, Fénelon G, Flahault A, Manifacier MJ, Michelet D, Boller F. Neuropsychological prediction of dementia in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64:178–183. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams-Gray CH, Foltynie T, Brayne CEG, Robbins TW, Barker RA. Evolution of cognitive dysfunction in an incident Parkinson’s disease cohort. Brain. 2007;130:1787–1798. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams-Gray CH, Evans JR, Goris A, et al. The distinct cognitive syndromes of Parkinson’s disease: 5 year follow-up of the Cam-PaIGN Cohort. Brain. 2009;132:2958–2969. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muslimovic D, Post B, Speelman JD, Schmand B. Cognitive profile of patients with newly diagnosed Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2005;65:1239–1245. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180516.69442.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron IGM, Pari G, Alahyane N, et al. Impaired executive function signals in motor brain regions in Parkinson’s disease. Neuro Image. 2012;60:1156–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander GE, Crutcher MD. Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:266–271. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90107-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheesman AL, Barker RA, Lewis SJG, Robbins TW, Owen AM, Brooks DJ. Lateralisation of striatal function: evidence from 18F-dopa PET in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1204–1210. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.055079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polito C, Berti V, Ramat S, et al. Interaction of caudate dopamine depletion and brain metabolic changes with cognitive dysfunction in early Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:206–e29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cools R. Dopaminergic modulation of cognitive function—implications for L-DOPA treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kish SJ, Shannak K, Hornykiewicz O. Uneven pattern of dopamine loss in the striatum of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Pathophysiologic and clinical implications. New Engl J Med. 1988;318:876–880. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198804073181402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cools R, Barker RA, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Enhanced or impaired cognitive function in Parkinson’s disease as a function of dopaminergic medication and task demands. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:1136–1143. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.12.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cools R, Barker RA, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. L-Dopa medication remediates cognitive inflexibility, but increases impulsivity in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:1431–1441. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cools R, Stefanova E, Barker RA, Robbins TW, Owen AM. Dopaminergic modulation of high-level cognition in Parkinson’s disease: the role of the prefrontal cortex revealed by PET. Brain. 2002;125:584–594. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cools R, Lewis SJG, Clark L, Barker RA, Robbins TW. L-DOPA disrupts activity in the nucleus accumbens during reversal learning in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:180–189. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer-Lindenberg A, Kohn PD, Kolachana B, et al. Midbrain dopamine and prefrontal function in humans: interaction and modulation by COMT genotype. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:594–596. doi: 10.1038/nn1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaasinen NEN, Brück A, Eskola O, Bergman J, Solin O, Rinne JO. Increased frontal [(18)F]fluorodopa uptake in early Parkinson’s disease: sex differences in the prefrontal cortex. Brain. 2001;6:1125–1130. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.6.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowe JB, Hughes L, Ghosh BCP, et al. Parkinson’s disease and dopaminergic therapy—differential effects on movement, reward, and cognition. Brain. 2008;131:2094–2105. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cools R, Miyakawa A, Sheridan M, D’Esposito M. Enhanced frontal function in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2010;133:225–233. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura T, Ghilardi MF, Mentis M, et al. Functional networks in motor sequence learning: abnormal topographies in Parkinson’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;12:42–60. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200101)12:1<42::AID-HBM40>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feigin A, Ghilardi MF, Carbon M, et al. Effects of levodopa on motor sequence learning in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2003;60:1744–1749. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000072263.03608.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monchi O, Petrides M, Mejia-Constain B, Strafella AP. Cortical activity in Parkinson’s disease during executive processing depends on striatal involvement. Brain. 2007;130:233–244. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawamoto N, Piccini P, Hotton G, Pavese N, Thielemans K, Brooks DJ. Cognitive deficits and striato-frontal dopamine release in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2008;131:1294–1302. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko JH, Antonelli F, Monchi O, et al. Prefrontal dopaminergic receptor abnormalities and executive functions in Parkinson’s disease. Human Brain Mapping. 2012 Feb 14; doi: 10.1002/hbm.22006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durstewitz D, Seamans JK. The dual-state theory of prefrontal cortex dopamine function with relevance to catechol-o-methyltransferase genotypes and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong S, Hikosaka O. Dopamine-mediated learning and switching in cortico-striatal circuit explain behavioral changes in reinforcement learning. Front Behav Neurosci. 2011;5:15. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marklund P, Larsson A, Elgh E, et al. Temporal dynamics of basal ganglia under-recruitment in Parkinson’s disease: transient caudate abnormalities during updating of working memory. Brain. 2009;132:336–346. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Beilen M, Portman AT, Kiers HAL, et al. Striatal FDOPA uptake and cognition in advanced non-demented Parkinson’s disease: a clinical and FDOPA-PET study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2008;14:224–228. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aarsland D, Zaccai J, Brayne C. A systematic review of prevalence studies of dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1255–1263. doi: 10.1002/mds.20527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurtig HI, Trojanowski JQ, Galvin J, et al. Alpha-synuclein cortical Lewy bodies correlate with dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2000;54:1916–1921. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.10.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulz-Schaeffer WJ. The synaptic pathology of alpha-synuclein aggregation in dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:131–143. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0711-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cummings JL. Intellectual impairment in Parkinson’s disease: clinical, pathologic, and biochemical correlates. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1988;1:24–36. doi: 10.1177/089198878800100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foster R, Campbell MC, Burack MA, et al. Amyloid imaging of Lewy body-associated disorders. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2516–2523. doi: 10.1002/mds.23393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edison P, Rowe CC, Rinne JO, et al. Amyloid load in Parkinson’s disease dementia and Lewy body dementia measured with [11C]PIB positron emission tomography. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:1331–1338. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.127878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Compta Y, Parkkinen L, O’Sullivan SS, et al. Lewy- and Alzheimer-type pathologies in Parkinson’s disease dementia: which is more important? Brain. 2011;134:1493–1505. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks DJ. Imaging amyloid in Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy Bodies with positron emission tomography. Mov Disord. 2009;24:S742–S747. doi: 10.1002/mds.22581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin J, Kepe V, Small GW, Phelps ME, Barrio JR. Multimodal imaging of Alzheimer pathophysiology in the brain’s default mode network. Int J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2011;2011:687945. doi: 10.4061/2011/687945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Mechanisms of Parkinson’s disease linked to pathological alpha-synuclein: new targets for drug discovery. Neuron. 2006;52:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perry EK, Curtis M, Dick DJ. Cholinergic correlates of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: comparisons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48:413–421. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.48.5.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein JC, Eggers C, Kalbe E, et al. Neurotransmitter changes in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson disease dementia in vivo. Neurology. 2010;74:885–892. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d55f61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bohnen NI, Kaufer DI, Ivanco LS, et al. Cortical cholinergic function is more severely affected in parkinsonian dementia than in Alzheimer disease: an in vivo positron emission tomographic study. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1745–1748. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.12.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bohnen NI, Kaufer DI, Hendrickson R, et al. Cognitive correlates of cortical cholinergic denervation in Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonian dementia. J Neurol. 2006;253:242–247. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0971-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cropley VL, Fujita M, Bara-Jimenez W, et al. Pre- and post-synaptic dopamine imaging and its relation with frontostriatal cognitive function in Parkinson disease: PET studies with [11C]NNC 112 and [18F]FDOPA. Psychiatry Res. 2008;163:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hilker R, Thomas AV, Klein JC, et al. Dementia in Parkinson disease: functional imaging of cholinergic and dopaminergic pathways. Neurology. 2005;11:1716–1722. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191154.78131.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song IU, Kim YD, Cho JH, Chung SW, Chung YA. An FP-CIT PET comparison of the differences in dopaminergic neuronal loss between idiopathic Parkinson disease with dementia and without dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012 Feb 17; doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31824acd84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pappatà S, Santangelo G, Aarsland D, et al. Mild cognitive impairment in drug-naive Patients with PD is associated with cerebral hypometabolism. Neurology. 2011;77:1357–1362. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182315259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shimada H, Hirano S, Shinotoh H, et al. Mapping of brain acetylcholinesterase alterations in Lewy body disease by PET. Neurology. 2009;73:273–278. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ab2b58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bohnen NI, Müller MLTM, Kotagal V, et al. Heterogeneity of cholinergic denervation in Parkinson’s disease without dementia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012 May 19; doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kotagal V, Albin RL, Müller MLTM, et al. Symptoms of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder are associated with cholinergic denervation in Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:560–568. doi: 10.1002/ana.22691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bohnen NI, Koeppe RA, Minoshima S, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolic features of Parkinson disease and incident dementia: longitudinal study. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:848–855. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.089946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yilong M, Huang C, Dyke JP, et al. Parkinson’s disease spatial covariance pattern: noninvasive quantification with perfusion MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:505–509. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang C, Mattis P, Tang C, Perrine K, Carbon M, Eidelberg D. Metabolic brain networks associated with cognitive function in Parkinson’s disease. Neuro Image. 2007;34:714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma Y, Tang C, Spetsieris GP, Dhawan V, Eidelberg D. Abnormal metabolic network activity in Parkinson’s disease: test-retest reproducibility. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;27:597–605. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang C, Mattis P, Perrine K, Brown N, Dhawan V, Eidelberg D. Metabolic abnormalities associated with mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1470–1477. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304050.05332.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bohnen NI, Koeppe RA, Minoshima S, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolic features of Parkinson disease and incident dementia: longitudinal study. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:848–855. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.089946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hattori T, Orimo S, Aoki S, et al. Cognitive status correlates with white matter alteration in Parkinson’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:727–739. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ibarretxe-Bilbao N, Junque C, Marti MJ, Tolosa E. Brain structural MRI correlates of cognitive dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2011;310:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Daniel W, Doshi J, Koka D, et al. Neurodegeneration across stages of cognitive decline in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1562–1568. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kehagia AA, Roger AB, Robbins TW. Neuropsychological and clinical heterogeneity of cognitive impairment and dementia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1200–1213. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70212-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]