Abstract

Background

Abancay province is a long-standing geographical focus of sporotrichosis in the south central highlands of Peru. Therefore, we examined the features of 36 newly identified cases of sporotrichosis from two hospital centers in Abancay province. We also performed a literature review of studies conducted in this endemic geographical focus over a period of 28 years (1998 to 2012), and analyzed the demographic, clinical and epidemiological features of sporotrichosis in the cases reported in these studies.

Methodology

We examined the features of 36 new cases of sporotrichosis identified from two hospital centers in Abancay. Furthermore, we searched for relevant studies of cases of sporotrichosis in the endemic region using healthcare databases and literature sources. We analyzed a detailed subset of data on cases collected in Abancay, neighboring provinces, and other regions of Peru.

Results

A total of nine studies were identified, with 1467 cases included in the final analysis. We also analyzed 36 new cases found in the two hospital centers. Therefore, the combined total of cases analyzed was 1503. Of this total, 58% were male, and approximately 62% were aged ≤14 years. As expected, most cases were from Abancay province (88%), although 12% were from neighboring provinces and other regions of Peru. The lymphocutaneous form (939 cases) was the commonest. The face was the most commonly affected region (647 cases). A total of 1224 patients (81.4%) received treatment: 95.8% received potassium iodide, 2.6% ketoconazole and 1.6% itraconazole. The overall success rates were 60.7% with potassium iodide, 32.2% with ketoconazole and 85% with itraconazole.

Conclusions

The epidemic of sporotrichosis has been occurring for three decades in the province of Abancay in Peru. This mycosis affects primarily the pediatric population, with predominantly the lymphocutaneous form in the facial region. Although treatment with potassium iodide is safe and effective, response and adherence to treatment are influenced by its duration, cost, accessibility, and side effects.

Introduction

Sporotrichosis is a subcutaneous mycosis, caused by various species of the genus Sporothrix, a saprophyte of organic matter, mainly in plants and vegetables [1]. Initially, the causal agent of this disease was thought to be a unique thermally dimorphic fungus Sporothrix schenckii. Recently, S. schenckii isolates, which exhibited a degree of geographical specificity, were regrouped into at least six cryptic species by multilocus phylogenetic analysis. Medically relevant species of Sporothrix now include S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii (sensu stricto), S. globosa, S. mexicana and S. luriei [2,3]. Infection is acquired by traumatic inoculation of environmental material, or from a cat scratch or bite [1,4–6]. After inoculation of the fungus, the individual may develop lymphocutaneous lesions, fixed or disseminated [1,7,8]. In recent decades, the incidence has been increasing in tropical and subtropical regions, with outbreaks associated with zoonotic transmission [4,5]. Sporotrichosis is now the commonest subcutaneous mycosis in the Americas [1]. In Peru, sporotrichosis occurs more frequently in the Andean provinces, including Abancay, Cajamarca, La libertad, Cusco and Ayacucho, although it is also increasingly reported in areas where the disease was rare decades ago [8–12]. Sporotrichosis is hyperendemic in Abancay, an inter-Andean province located in the Andes Mountains, where the overall incidence between 1997 and 1998 was 98 cases/100,000 inhabitants and a pediatric incidence of 156 cases/100,000 children aged ≤15 years [8,9]. The endemic area of sporotrichosis in Abancay are characterized by poor sanitation, substandard housing and little access to health services—a challenge to control and eradication of the disease. Over the last two decades, the increase in the number of cases of the disease has been continuous for more than 20 years and remains on the rise, affecting vulnerable groups. In the light of these data, we examined the features of 36 new cases of sporotrichosis from two hospital centers in Abancay province. We also performed a literature review of studies conducted in this endemic geographical focus over a period of 28 years (from 1998 to 2012), and analyzed the demographic, clinical and epidemiological features of sporotrichosis in the cases reported in these studies.

Materials and Methods

Study Area and Population

The study was conducted in Abancay (the departmental capital of Apurímac), a poor area in the south central highlands of Peru (72.88°W, 13.63°S, 2392 m above sea level) [13] where there are two main seasons—a warm and wet season (November to April), and a cold and dry season (May to October). From November to April, the maximum temperature (Tmax) commonly reaches 20°C (range 0–20°C) and the 6-month cumulative precipitation is 100–1000 mm; in contrast, from May to October, the Tmax rarely reaches 20°C (range -4–28°C), and the 6-month cumulative precipitation is around 0–500 mm. The Tmax usually peaks from September to October (12–32°C) [14]. The estimated population in 2013 was 105,694 according to a regularly updated census, and the major industries of Abancay are small businesses, agriculture and regional services [13].

Report of New Cases

We performed a retrospective study of 36 newly identified cases of sporotrichosis from two hospitals in Abancay province: 26 cases from Santa Teresa Clinic (STC) in 2012 (previously, Centro Medico Santa Teresa [CMST]), and ten cases from Pueblo Joven Centenario Health Center (PJCHC) in 2011. STC is a primary care hospital, with 20-bed inpatient as well as outpatient facilities serving the city of Abancay and the provinces of Apurímac. Moreover, since 1982, STC, which is equipped with the appropriate laboratory facilities and clinical infrastructure for the diagnosis and treatment of sporotrichosis, has been the main referral center for sporotrichosis in Apurímac [7,8,15]. PJCHC is an 18-bed health center that serves both as a community hospital for the periurban area, where sporotrichosis is endemic, and as a primary care hospital in Abancay province.

The isolation of Sporothrix from clinical culture samples was used as an inclusion criterion. Clinical and laboratory data were retrieved from the original medical records and a form attached to the medical history. We also reviewed patients’ demographic information, diagnosis, clinical form of infection, anatomical location, evolution time of the lesions, treatment administered and adverse reactions.

Sporotrichosis in Abancay: Literature Review

The literature review was conducted, according to the guidelines of the PRISMA statement [16], which is available in S1 Table. We performed a bibliography search of studies published in English and Spanish, without any year limit, using the following online databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Lilacs, Embase and SCIELO. Key search terms included “Sporotrichosis”, “Abancay”, “Sporothrix schenckii”, “Sporotrichosis Abancay”, “Abancay children”, “risk factors for sporotrichosis” and “endemic Abancay”. Articles were also obtained through hand searches from journals relevant to infectious diseases and dermatology, conference proceedings and past reports of STC. Studies describing any form of sporotrichosis and S. schenckii infection in Abancay, and neighboring provinces were included, and studies that lacked clinical and therapeutic data, duplicate results and clinical images were excluded. We then analyzed the included studies in terms of demographic, clinical, and therapeutic features, and risk factors for sporotrichosis.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are described with descriptive statistics, including mean (range) as appropriate and categorical data with frequencies (%). Results of primary studies of risk factors were described by Odds ratios (OR) and confidence intervals (CI).

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Institute of Tropical Diseases and Biomedicine of National University of San Antonio Abad of Cusco, Peru. Only retrospective information and anonymous data were used.

Results

From the literature review, a total of 16 studies were identified, of which nine were included in the final analysis which comprised 1527 cases of sporotrichosis from 1985 to 2011 [7–9,15,17–21] (Fig 1). Of the 1527 cases, data from only 1467 cases were used, as they included complete demographic and clinical information. Therefore, together with the 36 new cases from the two hospital centers, we analyzed a total of 1503 cases (Table 1).

Fig 1. Flow diagram of literature search.

CMST, Centro Medico Santa Teresa.

Table 1. Cases of sporotrichosis in Abancay and main characteristics of the studies analyzed.

| First Author [Ref] (Years) | No. of patients/ Mean age (range, yr) | Place of study | Period of data collection | Age (yr) | Gender | Clinical form, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–14 | ≥15 | M | F | Lymphocutaneous | Fixed | Disseminated | ||||

| Present study | 26/ 25 (2 to 82 yr) |

STC | 2012 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 13 (50%) | 13 (50%) | 0 |

| Present study | 10/ 20 (3 to 65 yr) |

PJCHC | 2011 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 (60%) | 4 (40%) | 0 |

| Ramírez et al. [7] (2012) | 485/ 18 (6 m to 86 yr) |

STC | 2004–2011 | 276 | 209 | 302 | 183 | 308 (63.5%) | 176 (36.3%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Aguilera et al. [17] (2005) | 198/ (0–14 and ≥15 yr) |

CMST | 2000–2003 | 138 a | 60 | 68 | 70 | 83 (60%) | 41 (30%) | 14 (10%) |

| Lyon et al. [9] (2003) | 201/ 10 (1 to 82 yr) |

3 Laboratory Abancay | 1997–1999 | 133 | 68 | 127 | 74 | 201 (100%) b | ||

| Pappas et al. [8] (2000) | 238/ (0–14 and ≥15 yr) |

CMST | 1995–1997 | 143 | 95 | 133 | 105 | 130 (55%) | 85 (36%) | 23 (9%) |

| Meneses et al. [18] (1992) | 18/ (9 to 57 yr) |

CMST | 1990 | not specif | 10 | 8 | 10 (55.6%) | 7 (38.9%) | 1 (5.5%) | |

| Cabezas et al. [15] (1996) | 57/ (2–16 and 3–18 yr) |

CMST | 1990 | 2–16 yr (n = 29) 3–18 yr (n = 28) |

30 | 27 | 26 (45.6%) | 30 (52.6%) | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Meneses et al. [19] (1991) | 261/ (0–24 and ≥25 yr) |

CMST | 1987–1989 | 0–24 yr (n = 205) ≥25 yr (n = 56) |

153 | 108 | 138 (52.9%) | 97 (37.1%) | 26 (10%) | |

| Flóres et al. [20] (1991) | 39/ (0 to 49 yr) |

CMST | 1986 | 26 | 13 | 15 | 24 | 13 (33.4%) | 22 (56.4%) | 4 (10.2%) |

| Reports STMC [21] (1985) | 30/ (0–14 and ≥15 yr) |

CMST | 1985 | 19 | 11 | 15 | 15 | 11 (36.7%) | 15 (50%) | 4 (13.3%) |

Abbreviations: yr, years; m, months; M, male; F, female; STC, Santa Teresa Clinic; CMST, Centro Medico Santa Teresa; PJCHC, Pueblo Joven Centenario Health Center.

aThe study included only children aged 0–14 years.

bThe study included only cases of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.

Of the 1503 cases, 58% (n = 871) were men, and 42% (n = 632) women, aged between 6 months and 86 years, with approximately 62% aged ≤14 years. In addition, 88% (n = 1318) of the cases were from Abancay province, while patients from the neighboring provinces (Andahuaylas, Aymaraes, Antabambas and Grau) accounted for 11% (n = 175) of the cases, and 1% (n = 15) were from other regions of Peru (Cusco, Ayacucho, Ica and Puno) (Fig 2). Over 70% were preschool children and school students, 5.4% farmers and 3.7% housewives. Other occupations included administrative roles, builders, craftsmen, taxicab drivers and peddlers.

Fig 2. Geographical distribution of sporotrichosis cases in Abancay—Apurímac 1985–2012, Peru.

The findings reported a lower number of casos at higher altitude in Apurímac.

The clinical lymphocutaneous form (939 cases, 62.5%) was the commonest form, followed by the fixed (490 cases, 32.6%) and disseminated (74 cases, 4.9%) forms (Table 1). The evolution time of the lesion to diagnosis ranged from 7 days to 5 years. The location of the lesions was described in 1475 (98%) patients. The lesions were reported to occur more frequently on the face (647 cases, 44%), followed by the upper limbs (524 cases, 36%), lower limbs (197 cases, 13%) and other anatomical regions (107 cases, 7%).

The diagnosis was based on the isolation of the fungus from cultures of biological samples. In the nine studies reviewed, all isolates were identified as S. schenckii. Of the 36 new cases, 34 isolates were identified as Sporothrix spp., and two as S. schenckii s. str. [22], using the morphophysiological method of Marimon et al. [2,3].

Furthermore, a total of 1224 patients (81.4%) received some form of medical treatment; 1173 (95.8%) received potassium iodide (KI), 31 (2.6%) ketoconazole and 20 (1.6%) itraconazole. The overall treatment success rates reported were 60.7% (n = 712) with KI, 85% (n = 17) with itraconazole and 32.2% (n = 10) with ketoconazole. Details and results of these treatments are summarized in Table 2. The average treatment duration was 41.9 days with KI, and 54.7 days with itraconazole. Treatment dropout rates were 31% (n = 394) with KI, 61.3% (n = 19) with ketoconazole and 10% (n = 2) with itraconazole. Of the 1173 patients who were treated with KI, 79 (6.7%) had mild adverse events, whereas, of the 20 patients who received itraconazole, ten (50%) had mild adverse events. Treatment was discontinued due to serious adverse effects in 52 (4.4%) patients taking KI, and in two patients on ketoconazole. Itraconazole was discontinued in one patient who became pregnant, while, in another patient, the treatment with KI failed (Table 2).

Table 2. Treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis in Abancay, Peru.

| First Author [Ref] (Years) | No. of patients | Place of study | Treatment received [n =] | Cure rate, n (%) | Dropout rate, n (%) | Side-effects a | Suspended treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present study | 26 | STC | KI 20 or 40 drops/tid [n = 22] | 10 (45%) | 12 (55%) | 6 cases | |

| Present study | 10 | PJCHC | KI 20 or 40 drops/tid [n = 10] | 6 (60%) | 4 (40%) | ||

| Ramírez et al. [7] (2012) | 485 | STC | KI 20 or 40 drops/tid [n = 483]; | 400 (82.8%) KI; | 66 (13.7%) KI | 17 KI b | |

| Itra 100 mg po/bid [n = 2] | 2 (0.41%) Itra | ||||||

| Aguilera et al. [17] (2005) | 138 c | CMST | KI 20 drops/tid [n = 138] | 59 (42%) | 79 (58%) | not specif | |

| Lyon et al. [9] (2003) | 201 | 3 Laboratory | KI 20 or 40 drops/tid [n = 34] | not specif | not specif | not specif | not specif |

| Abancay | |||||||

| Pappas et al. [8] (2000) | 238 | CMST | KI 20 or 40 drops/tid [n = 165]; | 44 (26.7%) KI; | 89 (54%) KI; | 32 KI | (32 KI; 2 Ket) b |

| Ket 400–800 mg/day po [n = 31] | 10 (32.5%) Ket | 19 (66%) Ket | 1 failed KI | ||||

| Meneses et al. [18] (1992) | 18 | CMST | Itra 100 mg/day [n = 14]; | 15 (83%) | 2 (11.1%) | 9 cases | 1 pregnancy |

| Itra 150 mg/day [n = 3]; | |||||||

| Itra 200 mg/day [n = 1] | |||||||

| Cabezas et al. [15] (1996) | 57 | CMST | KI 3.88 g/day [n = 29] vs. | 26 (89.7%) KI [3.88 g/day] | 2 (10.5%) | 28 cases | 3 KI b |

| KI 20 or 40 drops/tid [n = 28] | vs. 25 (89.2%) KI | 1 case lost | |||||

| [20 or 40 drops/tid] | |||||||

| Meneses et al. [19] (1991) | 261 | CMST | KI 20 or 40 drops/tid [n = 195] | 117 (60%) | 66 (33.8%) | not specif | 12 cases lost |

| Flóres et al. [20] (1991) | 39 | CMST | KI 20 or 40 drops/tid [n = 39] | 15 (38.5%) | 24 (61.5%) | 4 cases | |

| Reports STMC [21] (1985) | 30 | CMST | KI 20 or 40 drops/tid [n = 30] | 10 (66.6%) | 20 (33.4%) | not specif |

Abbreviations: STC, Santa Teresa Clinic; CMST, Centro Medico Santa Teresa; PJCHC, Pueblo Joven Centenario Health Center; KI, Potassium iodide (Paediatric dose: 2–20 drops/tid; Adult dose: 4–40 drops/tid); Itra, itraconazole; Ket, ketoconazole; tid, 3 times daily; bid, twice per day; po, orally.

aMild adverse event: metallic taste and gastrointestinal intolerance (Nausea, vomiting and gastritis).

bSerious adverse event.

cThe study included only children aged 0–14 years.

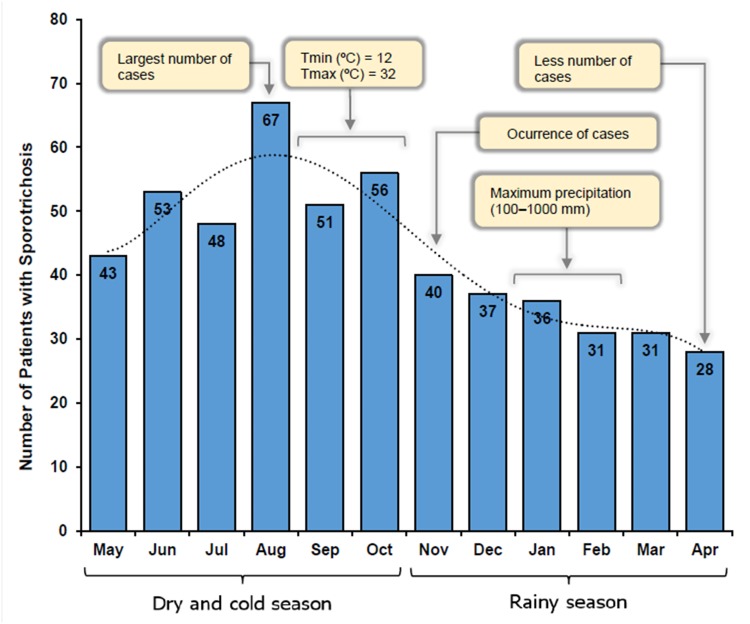

The highest frequency of cases was noted from May to October (61%), and the lowest in April (5.4%) (Fig 3). Risk factors for sporotrichosis identified in Abancay are detailed in Table 3.

Fig 3. Monthly distribution of 521 cases of sporotrichosis in Abancay, Peru, from January 2004-December 2012.

A strong seasonality in the cases distribution was observed between May and October (Relationship between maximal temperatures and largest number of casos). By contrast, the lowest number of cases coincides with the months from November to April (Rainy season reduces the number of cases sporotrichosis in Abancay). Tmin: Minimum temperature; Tmax: Maximum temperature.

Table 3. Risk factors for sporotrichosis in Abancay, Peru.

| Risk factor(s) | Ref. | p value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults ≥15 years | |||

| Ceiling made of raw wood | [9] | 0.02 | 6.9 (1.4–35.2) |

| Work outdoors | [9] | 0.004 | 5.2 (1.7–15.8) |

| Children <15 years | |||

| Play in the fields | [9] | 0.04 | 25.2 (1.1–588) |

| Having a cat | [7,9] | 0.02 | 9.1 (1.3–61.4) |

| Dirt floors in the house | [7,9] | 0.04 | 3.8 (1.0–13.7) |

| Ownership of a pig | [9] | 0.006 | 0.03 (0.002–0.3) |

| Ownership of a radio | [9] | 0.02 | 0.02 (0.001–0.5) |

Discussion

The first 15 cases of sporotrichosis in Abancay were found in Santa Teresa Clinic (previously, Centro Medico Santa Teresa [CMST]) between 1982 and 1984. These findings led us to establish a program of diagnosis and treatment in this province [21], and STC has since been treating a steadily growing number of patients with sporotrichosis. In late 2012, more than 1500 patients were diagnosed with sporotrichosis [7–9,15,17–21], with the most frequently affected group being males aged ≤14 years (62%), which explains the high incidence in the preschool and school population (>70%). This is in contrast to Rio de Janeiro where women aged >30 years are the most affected [4,6].

In our study, we found the largest number of cases was from Abancay (88%). In this province, the highest frequency of cases coincided with the dry and cold season (May to October; 61%), and the lowest frequency in the rainy season (November to April; 39%) (Fig 3). Contrary to this, other studies in Himachal Pradesh and South Africa reported rain and humidity as two significant favourable factors for sporotrichosis [23,24]. There is very limited evidence that sporotrichosis is seasonal [1]. However, our study findings suggest that climatic factors might play a role in the distribution and frequency of sporotrichosis, as, if the climate in Abancay were to become hotter and drier (due to either natural variability or anthropogenic forcing), this could potentially influence the distribution and severity of sporotrichosis. We identified reports of cases in neighboring provinces, suggesting that the increase in infection is not limited to Abancay (Fig 2). In this Andean region, Apurímac has inhabitants spread across all ecological zones, and the distribution of sporotrichosis may be influenced by the heterogeneity of climatic and geographical conditions and the high number of farmers in these provinces. Therefore, the geo-climatic conditions are conducive to the growth of Sporothrix as a saprophyte in the environment. Sporotrichosis is also prevalent in other Peruvian agricultural and rural areas [10–12], as was observed in 1% of cases.

As reported in our clinical findings here and from other studies, the lymphocutaneous form is the commonest clinical form (62.5%) [1,4–9]. In contrast, the fixed form is less common and morphologically has a wide clinical spectrum, ranging from lesions with ulcerated plaques, crusted, warty, and satellite lesions to psoriasiform lesions [1,22]. This is associated probably with the virulence of the strain, the immune status and depth of inoculation, and the occurrence of multiple inoculations in patients from endemic areas during their work or recreational activities. The disseminated form occurs in patients with diabetes, HIV/AIDS, hematologic malignancies, chronic alcoholism and malnutrition [1,25–27]. It is possible that the smaller number of cases in our series (4.9%) showing disseminated lesions included individuals from these patient groups.

In our study, about half of the cases had facial involvement (44%), mainly children aged ≤14 years. This finding could be attributed to the fact that the face is an exposed area with delicate skin, susceptible to superficial trauma or scratching with fingernails laden with contaminated soil [7,8]. Lesions on the upper limbs were present in 36% of patients; again these are areas that are exposed, and therefore susceptible, to inoculant trauma, especially in people aged ≥15 years, such as farmers, who manipulate plant materials [7,9]. On the other hand, the lower limbs and other anatomical regions were less affected.

The drug of choice for sporotrichosis is itraconazole [28]. However, in Abancay, KI has been adopted as the treatment of choice, starting with two drops, and a maximum of 20 drops/3 times daily in children and 4–40 drops/3 times daily in adults [7,15], with the duration of treatment determined by the evolution of the lesions [7,15,19,20]. In the current study, the therapeutic response to KI was moderate; of the 1173 patients who received KI treatment, 60.7% were cured, and adverse effects were also lower. Of note, there is a lack of clinical trials reported in the literature to determine the optimal dose of KI as a treatment for sporotrichosis. The results of treatment with itraconazole and ketoconazole were not convincing, because these were testing treatments. Dropout rates to treatment were high, probably due to the treatment duration, cost, accessibility, and side effects (Fig 4)

Fig 4. Health and current situation of sporotrichosis.

Two isolates from our 36 new cases were identified as S. schenckii s. str. [22], whereas all isolates from the nine studies were identified as S. schenckii. In 2004, Holechek et al. identified six genotypes of S. schenckii in clinical samples from patients of Abancay, which he named genotypes I, II, III, IV, V and VI [29]. These results suggest that, in Abancay, there could exist a high variability of the Sporothrix species, consistent with the species of the Sporothrix complex described by Marimon et al. [2,3].

It is still not certain how the infectious agent has been disseminated throughout Abancay and its outskirts. In this province, patients with poor socioeconomic status live in mud houses with dirty floors, thatched or wooden, and in close proximity to thorny plants, all of which provide a favorable environment for fungal growth. In adults, the risk of infection increases when working in the field without protection (men and women cultivate and plough the land, and collect firewood and fodder from forests, as well as rear livestock) and with children playing in the field [7–9]. Thus, people are at high risk of acquiring the disease. Such practices are likely to promote the continued spread of the mycosis, a problem which must be controlled in Abancay. Interaction with cats is another key risk factor to the transmission of the fungus, which can lead to epidemic outbreaks [4–6]. In 2008, Kovarik et al. [30] isolated the fungus on claw fragments and materials collected from cats’ nasal and oral cavities. These findings suggest that apparently healthy cats are a reservoir of the fungus and can transmit the infection without showing outward signs of the disease [30]. Indeed, contact with cats has been shown to be a significant risk factor for sporotrichosis in this endemic geographical focus of Peru [9]. Moreover, given the high proportion of cases, the wide geographical distribution in the regional territory, and the high frequency of contact with cats, it is possible that an epidemic outbreak could result from this zoonotic transmission, similar to the situation in Brazil which began in 1998 and today is still uncontrolled [4–6]. Finally, the current status of sporotrichosis is also influenced by the prevailing health situation (Fig 4).

Conclusions

The epidemic of sporotrichosis has been occurring for three decades in the province of Abancay in Peru. This mycosis affects primarily the pediatric population, predominantly as the lymphocutaneous form in the facial region. Although treatment with KI is safe and effective, response and adherence to treatment are influenced by its duration, cost, accessibility, and side effects. Therefore, this disease should be included in Peru’s national health agenda.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

To Dra. Liz Miranda Hurtado and nurse Santusa Ballón Baca for logistical support during the investigation. Special thanks to Mr. Jimmy Delgado Tomaylla for reviewing the English style of the manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1. Arenas R. Medical mycology ilustrada. 3rd ed Mexico: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2008. pp 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marimon R, Cano J, Gené J, Sutton DA, Kawasaki M, Guarro J. Sporothrix brasiliensis, S. globosa, and S. mexicana, three new Sporothrix species of clinical interest. J Clin Microbiol. 2007; 45: 3198–3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marimon R, Gené J, Cano J, Guarro J. Sporothrix luriei: a rare fungus from clinical origin. Med Mycol. 2008; 46: 621–625. 10.1080/13693780801992837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barros MB, Schubach AO, do Valle AC, Schubach TM, dos Reis RS, Conceição MJ, et al. Sporotrichosis with widespread cutaneous lesions: report of 24 cases related to transmision by domestic cats in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Int J Dermatol. 2003; 42: 677–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barros MBL, Schubach TP, Coll JO, Gremião ID, Wanke B, Schubach A. Sporotrichosis: development and challenges of an epidemic. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2010; 27: 455–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Freitas DF, do Valle AC, de Almeida PR, Bastos FI, Galhardo MC. Zoonotic Sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A Protracted Epidemic yet to be curbed. Clin Infect Dis. 2010; 50: 453 10.1086/649892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramírez MC, Lizarraga J, Ticona E, Carrion O, Borda S. Clinical and epidemiological profile of sporotrichosis in a reference clinic at Abancay, Peru: 2004–2011. Rev Peru Epidemiol. 2012; 16: 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Papas PG, Tellez I, Deep AE, Nolasco D, Holgado W, Bustamante B. Sporotrichosis in Peru: description of an área of hyperendemicity. Clin Infect Dis. 2000; 30: 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lyon G, Zurita S, Casquero J, Holgado W, Guevara J, Brandt ME, et al. Population-based surveillance and a case-control study of risk factors for endemic lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis in Peru. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 36: 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. García M, Urquiaga T, López N, Urquiaga J. Cutaneous sporotrichosis in children at Regional Hospital in Peru. Dermatol Peru. 2004; 14: 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Geldres JJ, Miranda H, García J, Tincopa. [Sporotrichosis: determination of an endemic area in Northern Peru (Otuzco-La Libertad)]. Mycopathol Mycol. 1973; Appl 28; 51: 33–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. García R. [Esporotricosis en la altura de Cusco-Perú nueva zona endémica. experiencia de once años[. Folia Dermatol Perú. 1998; 9 (1–2): 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 13. INEI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática). Censos Nacionales 2007: XI de Población y VI de Vivienda; 2008. Lima, Peru. [Google Scholar]

- 14. SENAMHI (Servicio Nacional de Metereología e Hidrología). Caracterización climática de las regiones Cusco y Apurímac. 2012. Lima, Peru: [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cabezas C, Bustamante B, Holgado W, Begue RE. Treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis with one daily dose of potassium iodide. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996; 15: 352–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 6: e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aguilera S, Busto O, Ayechu A, Torresns A, Lizarraga J, Ticona E. [Esporotricosis en la infancia: revisión de 138 casos en una región andina endémica]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2005; 62 (Suppl 2): 1–263.15642234 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meneses G, Bustamante B, Holgado W, la Fuente J. Itraconazole therapy in subcutaneous sporotrichosis. Bol Soc Peru Med Interna. 1992; 5(1): 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meneses G, Cabezas C, Bustamante B, Cárdenas J, Bobbio L, Esquivel H, et al. Abstracts of the 5th Pan-American Congress of Infectious Diseases, 7–10 April 1991. Lima, Peru: Pan-American Congress of Infectious Diseases; 1991. Report of 261 cases of sporotrichosis from 1987 to 1989, Centro Medico Santa Teresa, Abancay, Peru [abstract VI].

- 20. Flores A, Indacochea S, De La Fuente J, Bustamante B, Holgado W. Sporotrichosis in Abancay, Peru. Rev Peru Epidemiol. 1991; 4: 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Santa Teresa Medical Center. Patient registry report 1985. 1985. Abancay, Peru: Santa Teresa Medical Center. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramírez MC, Lizárraga J. Granulomatous sporotrichosis: report of two unusual cases. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2013; 30: 548–553. 10.4067/S0716-10182013000500013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ghosh A, Chakrabarti A, Sharma VK, Singh K, Singh A. Sporotrichosis in Himachal Pradesh (north India). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999; 93: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verma S, Verma GK, Singh G, Kanga A, Shanker V, Singh D, et al. Sporotrichosis in Sub-Himalayan India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012; 6: e1673 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Freitas DF, de Siqueira B, do Valle AC, Fraga BB, de Barros MB, de Oliveira Schubach A, et al. Sporotrichosis in HIV-infected patients: report of 21 cases of endemic sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Med Mycol. 2012; 50: 170–178. 10.3109/13693786.2011.596288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bunce P, Yang L, Chun S, Zhang SX, Trinkaus MA, Matukas LM. Disseminated sporotrichosis in a patient with hairy cell leukemia treated with amphotericin B and posaconazole. Med Mycol. 2012; 50: 197–201. 10.3109/13693786.2011.584074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Al-Tawfi q JA, Wools KK. Disseminated sporotrichosis and Sporothrix schenckii fungemia as the initial presentation of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1998; 26: 1403–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barros MB, Schubach AO, de Vasconcellos R, Martins EB, Teixeira JL, Wanke B. Treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis with itraconazole—study of 645 patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 52: e200–206. 10.1093/cid/cir245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Holechek S, Casquero J, Zurita S, Guevara J, Montoya I. [Variabilidad genética en cepas de Sporothrix schenckii aisladas en Abancay, Perú]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2004; 21: 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kovarik CL, Neyra E, Bustamante B. Evaluation of cats as the source of endemic sporotrichosis in Peru. Med Mycol. 2008; 46: 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.