Abstract

Background

Trauma-induced coagulopathy is a complex multifactorial hemostatic response that is poorly understood.

Objectives

Identify distinct hemostatic responses to trauma and identify key components of the hemostatic system that vary between responses.

Patients/Methods

Cross-sectional observational study of adult trauma patients at an urban Level I trauma center Emergency Department. Hierarchical clustering analysis was used to identify distinct clusters of similar subjects using vital signs, injury/shock severity, and by comprehensive assessment of coagulation, clot formation, platelet function, and thrombin generation.

Results

Of 84 total trauma patients included in the model, three distinct trauma clusters were identified. Cluster 1 (N=57) displayed platelet activation, preserved peak thrombin generation, plasma coagulation dysfunction, moderately decreased fibrinogen concentration, and normal clot formation relative to healthy controls. Cluster 2 (N=18) displayed platelet activation, preserved peak thrombin generation, and preserved fibrinogen concentration with normal clot formation. Cluster 3 (N=9) was the most severely injured and shocked and displayed a strong inflammatory and bleeding phenotype. Platelet dysfunction, thrombin inhibition, plasma coagulation dysfunction, and decreased fibrinogen concentration were present in this cluster. Fibrinolytic activation was present in all clusters, but increased more so in Cluster 3. Trauma clusters were different most noticeably in their relative fibrinogen concentration, peak thrombin generation, and platelet-induced clot contraction.

Conclusions

Hierarchical clustering analysis identified 3 distinct hemostatic responses to trauma. Further insight into the underlying hemostatic mechanisms responsible for these responses is needed.

Keywords: Trauma, Hemostasis, Fibrinogen, Platelets, Coagulation, Thrombin

INTRODUCTION

Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy (TIC) is an important and incompletely-understood multifactorial response to trauma that is associated with increased bleeding, greater transfusion requirements, and increased mortality [1]. Brohi et al, first described spontaneous anticoagulation by an increase of international normalized ratio (INR) in the plasma of Emergency Department trauma patients [2]. Further work supported an anticoagulant mechanism from systemic increase of thrombomodulin, that when bound to thrombin, activated protein C (aPC) [3]. APC can inhibit factor V and VIII, thus reducing thrombin generation. Fibrinolysis is also enhanced by simultaneous inhibition of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and increased plasma Tissue Plasminogen Activator (tPA) levels [3–4]. Others have stratified trauma patients according to disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) score criteria, noting the presence of an activated, rather than anticoagulated hemostatic state leading to DIC with a hyperfibrinolytic phenotype [5]. There is also emerging evidence for a prominent role for platelet dysfunction in the pathomechanism of TIC. Even mildly-impaired platelet aggregation is strongly associated with poor outcomes in trauma patients [6]. In addition, inflammation may play an important role in modulating the acute coagulation response to trauma and blood loss. The cytokines Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) are elevated almost immediately after severe injury and/or blood loss in trauma and surgical patients [7]. Increased IL-6 in particular, is associated with massive transfusion, development of mulitorgan failure, and outcomes [8]. IL-6 can also directly activate fibrinogen gene promoters, thus linking its presence in plasma directly to subsequent coagulation responses [9]. Endothelial activation is also a prominent component of TIC, which may initiate coagulopathy after endothelial glycocalyx shedding, allowing for direct interaction between activated inflammatory cells and the endothelial surface [10,11]. However, there is limited understanding of how various components of the hemostatic and inflammatory systems and injury/patient characteristics interact to produce overall hemostatic phenotypes after trauma.

Much of our current understanding of coagulopathy after trauma comes from studies that grouped subjects according to injury severity, shock severity, and/or single estimates of coagulopathy like INR, viscoelastic clot strength, or platelet aggregation. These approaches have yielded significant knowledge regarding individual components of the hemostatic response to trauma. However, the information gained from these investigations is limited due to selection bias, a priori assumptions about outcome measures, and the chosen method of coagulopathy classification. In addition, the generally-accepted multifactorial nature of coagulopathy limits the ability of single outcome measurements to adequately identify the syndrome of traumatic coagulopathy. Alternatively, data mining techniques such as hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) can adequately identify distinct groups or phenotypes within larger cohorts by grouping similar variables and characteristics without requiring a priori assumptions. HCA is a multivariate technique of grouping rows together in a data set that share similar values whose values are close to each other relative to those of other clusters. It is a process that starts with each point in its own cluster, next the two clusters that are closest together are combined into a single cluster until there is only one cluster containing all the points. This type of clustering permits the detection of subgroups that otherwise would be disguised due to high variation or a priori assumptions [11]. HCA has been used successfully as a data mining tool to identify blood plasma lipidomics profiles [12] and identification of complex metabolic states in critically injured patients 13. The strategy of using HCA to group patients by combining their clinical profiles with broadly-measured hemostatic parameters may be useful to identify both distinct hemostatic responses and the relationships governing these responses. Such information can be used to improve our understanding of the pathophysiology of TIC and to guide further studies.

The primary aim of this study was to use HCA to identify distinct hemostatic responses within a general trauma patient cohort. We hypothesize that hierarchical clustering will identify multiple distinct hemostatic responses. We also aim to characterize the key differences between clusters and interpret how patient characteristics and individual components of the hemostatic system interact to produce an overall hemostatic response to trauma. To complete these aims we apply HCA to a prospective cohort of adult Emergency Department polytrauma patients who presented to an American urban level I trauma center and identify key differences in hemostatic parameters between clusters.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional study of trauma patients presenting to an American level I trauma center Emergency Department. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects according to an institutional human subjects review board-approved protocol consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki. A group of healthy non-injured volunteers who were not taking anticoagulants was recruited from the local population as a control group for comparison. Patients were excluded if they were less than 18 years of age, incarcerated, pregnant, suicidal, or known to be taking anticoagulant medications including aspirin, clopidogrel, or warfarin. To avoid confounding influences of blood transfusion or massive non-survivable injury with perimortem state, patients were excluded if they received any blood products prior to study sample blood draw, or were not expected to live for 3 days due to obvious massive non-survivable injury. The coagulation response in such perimortem patients is often dominated by massive hyperfibrinolysis, which would have added bias and skewed our data unnecessarily [13]. We also sought a mixed cohort of severely-injured trauma patients that would be more likely to vary in their individual hemostatic responses. Therefore, we excluded patients that were not expected to be admitted to the inpatient trauma service due to isolated or minor injury. Trauma patients were identified in the Emergency Department and blood was collected into standard citrated, (1:9 ratio of citrate to blood), EDTA, and Sodium-Heparin vacutainers prior to receiving any blood products. Samples were collected on arrival to the Emergency Department prior to subjects receiving any blood products, and blood was sampled again 8 hours later for repeat plasma coagulation and TEG measurements. Samples were either processed immediately for viscoelastic clot formation, platelet adhesion, and platelet aggregation in whole blood, fixed for flow cytometry analysis, or were centrifuged to platelet poor plasma and frozen at -80°C for later analysis. Clinical data including vital signs, transfusion requirements, injuries, clinical laboratories, and outcomes were collected from the medical record for each patient. Injury severity scores were obtained for each patient using the hospital trauma databank.

LABORATORY METHODS

Plasma Coagulation

Platelet-poor plasma was assayed for international normalized ratio (INR) activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and fibrinogen concentration using the START-4 coagulation analyzer according to manufacturer instructions (Diagnostica Stago, Parsippany, NJ, USA).

Platelet Function

Adhesion of platelets under high flow conditions was measured by time to occlusion of a small orifice using the platelet function analyzer 100 (PFA-100, Dade International Inc., Miami, FL) with exposure to Collagen/ADP. This device measures time to occlusion of a small aperture as whole blood is drawn through it under high-flow conditions, and has been shown to respond to changes in primary platelet adhesion mediated by theglycoprotein (GP) Ib-IX-V surface membrane complex in addition to von Willebrand Factor activity, and GPIIb/IIIa activation [14,15]. Platelet aggregation was also measured by impedance in whole blood (Chronolog Series 500 aggregometer, Chrono-Log Corp., Havertown, PA) in response to ADP (10μM) to evaluate platelet aggregation. Flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6, Accuri, Ann Arbor, MI) was used to measure platelet activation via the glycoprotein (GP) P-selectin because it is rapidly translocated to the platelet surface on stimulation. P-selectin content on the platelet surface was detected using the CD62-P monoclonal antibody conjugated with phycoerythrin [PE (mouse anti-human: BD Pharmingen)]. We also measure GPIIb/IIIa receptor surface transition to its high-affinity state using the monoclonal antibody to PAC-1 conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate [FITC (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). These assays provide an estimate of the platelet activation state.

Viscoelastic Measurements of Whole Blood Clot Formation

Thrombelastography (TEG 5000, Haemonetics, Niles IL) was used to measure whole-blood viscoelastic clot formation. The TEG 5000 reports time to onset of clot formation (R) that positively correlates with thrombin generation, the time to reach a predetermined level of clot stiffness (K) and the angle (α angle) that correlate with fibrin generation rate, the maximal clot amplitude or stiffness (MA), and the percent of clot breakdown due to fibrinolysis in the first 30 minutes after maximal amplitude (LY30%). The TEG with Platelet Mapping Assay™ (TEG-PM, Haemonetics Inc., Niles IL) was also used to determine the platelet contribution to clot amplitude. Platelets were selectively-activated using ADP and the amplitude difference between platelet-specific activation and maximal thrombin-induced clot formation during TEG measurement was calculated and expressed as % inhibition from maximal amplitude.

Fibrinolytic activation and Fibrinolysis

We measured clot lysis by TEG LY30% and fibrinolytic activation by D-Dimer measured by ELISA (Technozym D-Dimer, Technoclone GmbH, Vienna, Austria). D-dimer is a plasmin-specific cleavage product of fibrin.

Thrombin Generation

Thrombin generation profiles for each subject were generated using calibrated automated thrombography with a thrombin-specific flourogenic substrate (CAT, Thrombinoscope BV, Masstricht, The Netherlands)). Platelet-poor plasma was first activated with low level tissue factor (5pmol) to activate thrombin generation. The elapsed time from activation to onset of thrombin generation (Thrombin Lag Time), maximal thrombin concentration (C-Max), and area under the thrombin generation curve (Endogenous Thrombin Potential, ETP) were recorded and included in the final analysis. Thrombin-Antithrombin complexes were also measured in plasma by ELISA (TAT micro, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany).

Inflammation

The cytokines Interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Human IL-6 ELISA Kit II, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Human TNF ELISA Kit II, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were measured in plasma using ELISA as estimates of inflammatory response. Cell counts, including leukocyte count as an estimate of inflammation, and hemoglobin concentration were measured by automated cell counting in the research lab (ABX-60, Horiba, Irvine, CA).

STASTISTICAL METHODS

Descriptive statistics (median and interquartile range) were used to summarize demographics and outcome measurements due to significantly skewed data distributions. Outcome variables included IL-6, TNF-α, TEG parameters, categorical descriptions of injury severity, hemostatic transfusion thresholds, and blood products received. Clusters and control groups were then compared using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. Steel-Dwass adjustment was made to adjust for multiple comparisons for post-hoc comparisons. Chi Square analysis with likelihood ratio testing was used to compare nominal outcomes between clusters. Matched pairs analysis was used to measure the mean difference and 95% CI of the difference between the ED arrival sample and the 8-hour sample for plasma and TEG measurements.

Variables were selected for inclusion in the clustering analysis if they were measured in ≥90% of subjects and they represented an important component of clot formation (e.g. extrinsic and intrinsic pathways, fibrinogen, platelet activation and function, fibrinolysis, and inflammation). Stringent HCA variable selection was used, limiting the variables used to build the model to direct laboratory measurements. We chose to not use any clinical variables or subject characteristics (ISS, vital signs, resuscitation fluid volumes, etc…) in the model. These clinical and treatment variables have multiple co-linear effects on coagulopathy that have not yet been clearly defined, making them poor contributors to independent cluster selection. We also excluded thrombelastography parameters (R, K, Angle, MA, LY30%) because these measurements are derived from one overall clot formation curve and are therefore strongly collinear, making them less useful for clustering. Final variables included in the model were: INR, aPTT, fibrinogen concentration, TLT, ETP, C-Max, platelet count, PFA-100 Collagen/ADP closure time, ADP-activated platelet aggregation by impedance, ADP-activated TEG-PM percent inhibition, PAC-1%, P-Selectin %, D-Dimer, and leukocyte count (WBC).

The purpose of hierarchical clustering analysis is to classify data of previously unknown structure into discrete groups in an unbiased fashion. The procedure starts by considering each observation, or subject, as a single cluster and applying the model-specific selection criteria for merging of adjacent clusters for each variable assigned to the model. Model based HCA then proceeds by successively merging pairs of clusters until all subjects are clustered together [16].

Wards minimum variance method was compared to average linkage, complete linkage, and centroid linkage models. Wards minimum variance method uses classification likelihood, based upon the sum-of-squares when comparing variables to assign subjects to clusters based upon their similarity to one another. The distance between two clusters is the ANOVA sum of squares between the two clusters added up over all the variables. Average linkage uses the average distance between pairs of observations to join clusters and is slightly biased toward producing clusters with the same variance. Complete linkage uses the maximum distance between a subject in one cluster and a subject in the other clusters to link clusters and tends to produce clusters with roughly equal diameters that are susceptible to the influence of outliers. The Centroid method uses the squared Euclidean distance between subject means to link clusters. The centroid method is more robust to the influence of outliers. A procedure outlined by Fraley and Raftery, based upon identifying model with the highest Bayesian information criterion (BIC) with the least number of clusters for each proposed model was used to select the best performing model that was then used for HCA [17]. After model selection and clustering, discriminant analysis was used to confirm that the selected model demonstrated an acceptable degree of separation between clusters with minimal misclassifications. All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP statistical software (version 9.0.0: SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The overall level of significance for all statistical tests was p < 0.05.

RESULTS

N=163 trauma subjects were screened for enrollment. N=49 subjects were immediately excluded because they either declined participation (N=16), had known anticoagulant use (N=5), had received blood products prior to blood sample (N=2), or for other reasons (N=26). Additional subjects were excluded prior to HCA because they had incomplete data (N=6), or were not expected to survive at least 72 hours (N=9). A total of 99 trauma subjects met clinical inclusion criteria and were considered for HCA analysis. They were compared to 10 healthy uninjured volunteer control subjects who were enrolled separately.

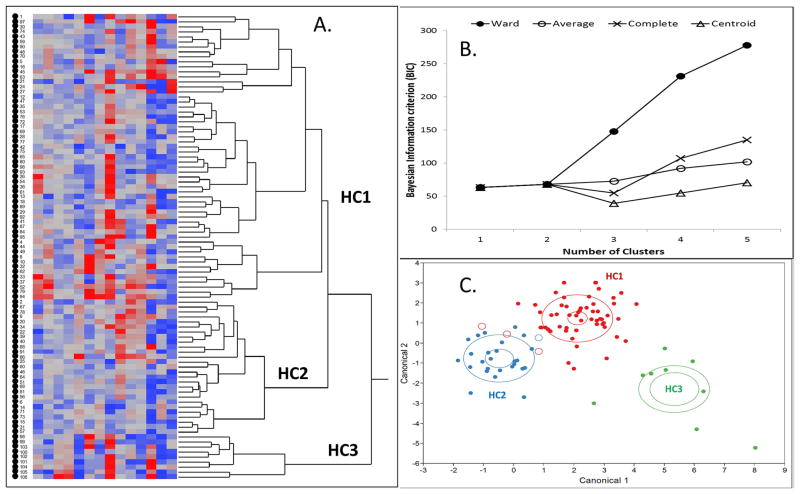

The Wards 3-cluster model was chosen as the best performing model for HCA of this dataset (Figure 1B). A total of 99 subjects and 14 variables were entered into the model for clustering. The total number of missing values was 28 of 1386 (1.7%). Due to the missing values, 84/99 (85%) subjects entered into the model could be clustered. The variable with the most missing values was TEG-PM % inhibition with 7/99 (7%) of values missing. The resulting Hierarchical Cluster Analysis showed 3 distinct clusters. According to the dendrogram, Cluster 1 (HC1, N=57) and Cluster 2 (N=18) were in closer proximity to each other compared to cluster 3 (HC3, N=9) which was located a further distance away and was more distinct. The dendrogram and heat map generating the 3 clusters are presented in Figure 1. Smaller sub-clusters present in the dendrogram were not evaluated due to small sample number.

Figure 1.

Heat map and dendrogram of hierarchical clustering analysis showing the left to right clustering of individual subjects into separate clusters based upon the similar values for each test variable (A). The results of analysis using a 3-cluster (HC1-3) Ward’s method are shown (A). Selection of best hierarchical clustering model using bayesian information criterion (BIC) plotted against number of clusters (B). The Ward method produced the highest BIC with the least number of clusters and was selected over other models. Discriminant analysis canonical plot of the three-cluster Ward model (C). Good discrimination between clusters was possible with misclassification of only 4 total subjects (open circles). Clusters 1 (Red) and 2 (Blue) were more similar, while cluster 3 (Green) was clearly discriminated. Larger ellipses identify the area in which 50% of the subjects are found for each cluster. Smaller ellipses identify the 95% CI for the center point of each cluster.

Demographics, injury patterns, shock severity, and mortality for each cluster are given in Table 1. Of note, no subjects received hemostatic agents including tranexamic acid prior to obtaining the Emergency Department or 8-hour blood samples. Overall mortality measured at 72 hours of hospital admission for those included in clustering was 7/84 (8%), of which one subject died before 8 hours and this subject was assigned to Cluster 2. Subjects were mostly middle-aged males with normal to overweight body composition. For each cluster, blunt injury from motor vehicle crashes was the primary mechanism of injury followed by penetrating injury from gunshot wounds. The prevalence of traumatic brain injury was also increased in Cluster 3.

Table 1.

Demographics, injury profiles, and mortality

| Healthy Controls | Injured Subjects

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | ||

| Age, | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 41 (29, 46) | 30 (24, 50) | 52 (30, 58) | 36 (21, 62) |

| Mean Body Mass Index | 22 (20, 26) | 25 (23, 28) | 28 (24, 32) | 26 (20, 29) |

| Prehospital Transport Time (min) | N/A | 42 (21, 59) | 34 (21, 60) | 30 (19, 38) |

|

| ||||

| N | 10 | 57 | 18 | 9 |

| Male Gender | ||||

| N(% of total) | 6(60%) | 49(86%) | 16(89%) | 5(55%) |

| Injury Category | ||||

| Penetrating | N/A | 15(26%) | 5(28%) | 2(22%) |

| Blunt | N/A | 40(70%) | 13(72%) | 7(78%) |

| Both | N/A | 2(4%) | 0 | 0 |

| Cause of Injury | ||||

| Stab Wound | N/A | 0 | 1(6%) | 0 |

| Gunshot Wound | N/A | 14(25%) | 4(22%) | 2(22%) |

| Motor Vehicle Crash | N/A | 31(54%) | 11(61%) | 5(56%) |

| Pedestrian struck by Motor Vehicle | N/A | 7(12%) | 2(11%) | 2(22%) |

| Fall | N/A | 5(9%) | 0 | 0 |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | N/A | 17(30%) | 2(11%) | 5(55%) |

| 72-Hour Mortality | N/A | 2(3.5%) | 1(5.6%) | 4(44%) |

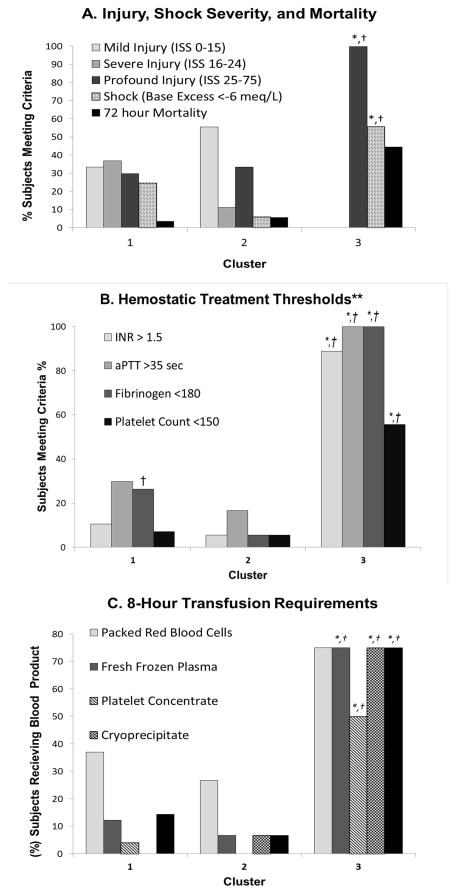

Vital signs, shock severity, and fluid resuscitation characteristics are given in Table 2 and figure 2. Cluster 3 demonstrated significantly abnormal vital signs, greater injury, and greater shock. Cluster 3 also clearly required more crystalloid and blood products over the first 8 hours of hospital treatment. Significantly more subjects met fibrinogen replacement criteria in Cluster 1 compared to Cluster 2. (Figure 2B)

Table 2.

Initial Emergency Department vital signs, injury severity, and 8-hour fluid resuscitation for injured subjects.

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Vital Signs | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |||

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 120 | 111 | 142 | 146 | 117 | 165 | 93 | 76 | 124 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 78 | 64 | 90 | 80 | 62 | 100 | 58 | 48 | 91 |

| Resp Rate (breaths/min)) | 18 | 14 | 24 | 18 | 15 | 22 | 20 | 16 | 29 |

| Pulse (beats/min) | 100 | 80 | 117 | 95 | 76 | 108 | 101 | 77 | 144 |

| Anatomical Injury Severity | |||||||||

| Injury Severity Scale | 19 | 14 | 27 | 14 | 10 | 29 | 41†‡ | 28 | 49 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 15 | 3 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 3‡ | 3 | 11 |

| Shock Severity | |||||||||

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 4.0 | 2.8 | 5.3 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 4.8 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 7.1 |

| Base Excess (meq/L) | −2.8 | −6.0 | −1.0 | −0.9 | −2.7 | 1.1 | −8.1†‡ | −16.2 | −5.0 |

| Hemoglobin Conc. (g/dl) | 12.5 | 10.8 | 13.7 | 12.1 | 10.8 | 13.7 | 9.3† | 6.2 | 12.0 |

| Resuscitation Fluid Volume (ml) | |||||||||

| Crystalloid at time of sample | 1400 | 500 | 2000 | 500 | 0 | 2000 | 2000 | 1350 | 2300 |

| Crystalloid at 8 hrs | 1,169 | 486 | 2599 | 346 | 56 | 2000 | 3,240‡ | 2195 | 7075 |

| Blood Products at 8 hrs (ml) | |||||||||

| Packed Red Blood Cells | 0 | 0 | 465 | 0 | 0 | 310 | 2325†‡ | 310 | 6433 |

| Fresh Frozen Plasma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1350†‡ | 169 | 3251 |

| Platelet Concentrate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100†‡ | 0 | 350 |

| Cryoprecipitate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 215†‡ | 38 | 633 |

Nonparametric multiple comparisons with Steel Dwass all-pairs adjustment for individual differences.

= Different vs. Cluster 1, p<0.05

= Different vs. Cluster 2, p<0.05

Figure 2.

(A) Histogram of nominal categories for injury severity, shock severity, and mortality for each cluster. There was a significantly more profound injury and hemorrhagic shock in cluster 3 vs. clusters 1 and 2. 72-hour mortality was also greatest in cluster 3, but statistical analysis comparing to other clusters was not possible due to few nonsurvivors in the other clusters. (B) Histogram of prevalence of standard hemostatic transfusion thresholds present in each cluster.**Criteria from Holcomb et al. Ann Surg 2012;256: 476–486. (C) Histogram of prevalence of subjects receiving blood products within the first 8 hours of hospitalization by cluster (N=68 total). Subjects were counted if they received any amount of specified blood product. Hemostatic transfusion was defined as receiving any amount of fresh frozen plasma, platelet concentrate, or cryoprecipitate. Chi Square LR: *P<0.05 vs. Cluster 1, † P<0.05 vs. Cluster 2.

Hemostatic and inflammatory parameters are given in Table 3. Again, Cluster 3 demonstrated the strongest bleeding phenotype with significantly different plasma coagulation pathway tests, fibrinogen concentration, thrombin generation, platelet dysfunction, and increased inflammatory markers. Interestingly, Cluster 1 differed from Healthy Controls and Cluster 2 by a slight prolongation of INR, a moderate decrease of fibrinogen, strongly-inhibited platelet-induced clot contraction, and increased WBC.

Table 3.

Clustered hemostatic and inflammatory variables measured on arrival in the Emergency Department.

| Healthy Controls | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Variable | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |||||

| Plasma Coagulation | INR | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.2* | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 2.0*†‡ | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| aPTT (sec) | 34.8 | 31.0 | 35.9 | 32.0 | 29.6 | 35.7 | 31.0 | 28.7 | 34.2 | 53.0*†‡ | 48.3 | 77.3 | |

| Fibrinogen Conc. (mg/dl) | 337.1 | 307.7 | 379.4 | 220.4* | 175.6 | 322.1 | 285 | 216.8 | 359.3 | 113.2*†‡ | 100.0 | 129.8 | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Thrombin Generation | Thrombin Lag Time (min) | 2.0 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 3.7*† | 2.5 | 4.0 | 2.3‡ | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| Endogenous Thrombin Potential (AUC) | 2147.7 | 1828.3 | 2281.3 | 1889.3 | 1609.2 | 2317.8 | 2050.2 | 1837.8 | 2342.0 | 1712.3 | 1260.7 | 2002.0 | |

| Maximal Thrombin Concentration (nM) | 382.6 | 335.7 | 426.0 | 369.8 | 322.5 | 414.3 | 381.2 | 332.4 | 436.3 | 203.7*†‡ | 186.2 | 235.6 | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Platelet Function | Platelet Count (109/L) | 217 | 184 | 263 | 247 | 184 | 310 | 236 | 195 | 250 | 149*†‡ | 91 | 192 |

| PFA100-COLL/ADP (sec) | 90 | 68.3 | 93.5 | 63 | 52.5 | 83.0 | 63 | 52.8 | 75.3 | 129‡ | 67.5 | 263.0 | |

| Aggregation-ADP (Ohms) | 10.0 | 9.4 | 12.1 | 11.0 | 8.0 | 13.8 | 10.0 | 8.4 | 11.4 | 5.5† | 3.3 | 9.0 | |

| TEGPM-% Inhibition-ADP | 52.7 | 25.4 | 58.1 | 92.7* | 74.6 | 98.4 | 46.6† | 30.1 | 65.0 | 99.2*†‡ | 94.9 | 99.9 | |

| PAC-1 (%) | 11.0 | 4.6 | 28.9 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 12.3 | 5.0 | 1.2 | 14.4 | 0.5† | 0.1 | 2.1 | |

| P-Selectin (%) | 2.7 | 0.7 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 8.9 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 8.0 | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Fibrinolytic Activation | D-dimer (ng/ml) | 73.8 | 41.3 | 178.9 | 2349.0* | 630.0 | 4201.3 | 628.9* | 206.4 | 2469.1 | 3551.1* | 1817.9 | 5000.0 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Inflammation | WBC (109/L) | 6.7 | 5.7 | 7.4 | 13.9* | 11.2 | 18.7 | 8.2† | 5.4 | 10.7 | 13.0* | 10.2 | 17.6 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | N/A | 58.4 | 13.6 | 160.7 | 25.9 | 7.3 | 65.9 | 179.8‡ | 54.5 | 210.2 | |||

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | N/A | 4.5 | 3.4 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 3.3 | 10.3 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 17.5 | |||

International normalized ratio (INR), activated partial thrombplastin time (aPTT), aperture closure time with collagen and ADP activation (PFA100-COLL/ADP), Impedance platelet aggregometry with ADP activation (Aggregation-ADP), Thrombelastography Platelet Mapping Assay percent inhibition after ADP activation (TEGPM-% Inhibition-ADP, high-affinity glycoprotein IIbIIIa platelet surface receptor expression (PAC-1), P-Selectin platelet surface receptor expression (P-Selectin), white blood cell count (WBC), Interleukin-6 concentration in plasma (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha concentration in plasma (TNF-α).

Nonparametric multiple comparisons with Steel Dwass all-pairs adjustment for individual differences.

= Different vs. Control, p<0.05

= Different vs. Cluster 1, p<0.05

= Different vs. Cluster 2, p<0.05

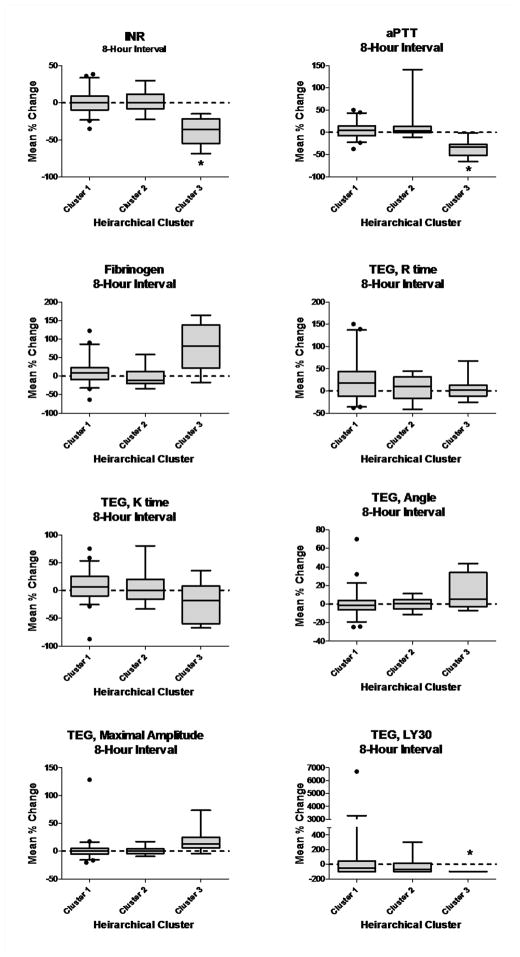

Plasma coagulation and TEG parameters measured at ED arrival and again after 8 hours of hospitalization are given in Table 4 and the interval changes for each parameter over 8 hours of hospitalization are given in Figure 3. At ED arrival, Cluster 3 demonstrated impaired clot formation by a significantly prolonged K time, decreased ANG, and decreased MA compared to other clusters. Of note, there were no differences in clot onset time (R), even though extrinsic and intrinsic plasma pathway tests were significantly prolonged. At 8 hours, the greatest changes were normalization of INR, and aPTT, increased fibrinogen, and decreased clot lysis with concurrent normalization of other TEG parameters in Cluster 3. No measured parameters changed significantly over 8 hours in Clusters 1 or 2. (Figure 3)

Table 4.

Plasma coagulation and thrombelastography measurements at ED arrival and after 8 hours of hospitalization for each cluster.

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Plasma Coagulation | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||||

| INR | ED Arrival | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 2.0†‡ | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| 8 Hours | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.4 | |

| aPTT (sec) | ED Arrival | 32.0 | 29.6 | 35.7 | 31.0 | 28.7 | 34.2 | 53.0†‡ | 48.3 | 77.3 |

| 8 Hours | 34.0 | 30.3 | 37.0 | 34.5 | 30.4 | 38.3 | 38.6 | 33.1 | 45.1 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | ED Arrival | 220 | 175.6 | 322.1 | 285 | 216.8 | 359.3 | 113.2†‡ | 100.0 | 129.8 |

| 8 Hours | 238.9 | 206.8 | 307.2 | 265.0 | 241.7 | 361.8 | 209.5 | 152.1 | 321.0 | |

|

TEG Clot Formation

| ||||||||||

| R (min) | ED Arrival | 4.3 | 3.3 | 5.1 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 6.0 |

| 8 Hours | 4.8 | 4.2 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 5.8 | 4.6 | 3.9 | 5.2 | |

| K (min) | ED Arrival | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.2†‡ | 1.6 | 3.1 |

| 8 Hours | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 2.4 | |

| ANG (deg) | ED Arrival | 70.2 | 66.2 | 72.9 | 71.2 | 64.9 | 74.3 | 61.7†‡ | 52.2 | 67.5 |

| 8 Hours | 69.7 | 63.6 | 71.6 | 70.0 | 63.5 | 73.6 | 65.1 | 58.8 | 71.6 | |

| MA (mm) | ED Arrival | 61.7 | 57.7 | 65.6 | 61.9 | 60.2 | 68.0 | 51.5†‡ | 45.2 | 60.8 |

| 8 Hours | 61.7 | 58.2 | 64.8 | 64.3 | 60.0 | 65.6 | 57.2 | 53.6 | 64.0 | |

| LY30 (%) | ED Arrival | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| 8 Hours | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0†‡ | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

International normalized ratio (INR), activated partial thrombplastin time (aPTT), Thrombelastography parameters: clot onset time (R), clot formation time (K), clotting angle (ANG), maximal amplitude (MA), percent clot lysis at 30 minutes (LY30).

Nonparametric multiple comparisons with Steel Dwass all-pairs adjustment for individual differences.

= Different vs. Cluster 1, p<0.05

= Different vs. Cluster 2, p<0.05

Figure 3.

Box and whisker plots of average percent changes in coagulation and thrombelastography measurements when measured at Emergency Department arrival and again at 8 hours of hospitalization. Whiskers represent 5th and 95th percentile. Plots that do not include zero represent statistically significant changes at alpha = 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Applying HCA to this selected trauma cohort revealed 3 distinct hemostatic responses to injury. Our results agree with previous characterizations of TIC showing that overt coagulopathy was most-often present in those patients with severe anatomical injury and tissue hypoperfusion from hemorrhagic shock 2. These patients also required more blood transfusions and were the most likely to die. It is clear that the most-severely injured and shocked patients (Cluster 3) exhibited a profoundly decompensated and impaired hemostatic and pro-inflammatory response that required significant hemostatic therapy. However, trauma patients have traditionally been stratified into only coagulopathic or non-coagulopathic groups. Only more recently have investigators identified a third acute hypercoagulable or activated hemostatic state to also exist in Emergency Department trauma patients. Branco et al. found that coagulation activation was associated with less blood product transfusion and low mortality, therefore being protective during the acute phase of trauma treatment [18]. Similarly, we also identified a small cluster of subjects (Cluster 2) having an overall activated hemostatic response that required minimal hemostatic therapy during the acute phase of trauma treatment (i.e. the first 8 hours of hospitalization). Increasingly, it appears that an acutely-activated hemostatic response may be optimal to reduce blood loss and any impairment of this activated state may signal an increased risk of bleeding. This concept is supported by evidence that even a minor prolongation of INR (>1.2) into what most providers accept as being “low normal” range is associated with increased mortality in trauma patients [19].

The majority of subjects in this cohort (58%, Cluster 1) demonstrated a distinct compensated initial hemostatic state with viscoelastic clot formation that was not significantly abnormal. This largest subgroup represents a newly-recognized and important group of trauma patients and its presence helps to bridge the previously-identified pro-hemostatic and bleeding responses to trauma. The hemostatic components that were most different between Cluster 1 and 2 were fibrinogen concentration and the relative platelet activation state. Hagemo et al, showed that 229 mg/dl fibrinogen concentration was the threshold for mortality in a recent multicenter observational study [20]. The fibrinogen concentration in Cluster 1 (Median=220, IQR = 175.6, 322.1) mirrored this critical threshold, theoretically placing this cluster at risk for increased mortality. D-Dimers were also elevated; suggesting significant fibrinolytic activation and ADP-specific clot contraction was also severely impaired. However, overall clot formation was not impaired. Perhaps subtle changes in clot formation were obscured in Kaolin-activated TEG. However, according to the cell-based model of hemostasis, small increases in plasma thrombin can activate platelets prior to the more dramatic “thrombin burst” at the platelet surface [21]. Therefore, it is logical that preserved maximal plasma thrombin generation after tissue factor activation was seen concurrently with preserved platelet adhesiveness and aggregation in clusters 1 and 2. Platelet adhesiveness under high shear (PFA100-COLL/ADP) was enhanced in these clusters even though there was no concurrent increase in PAC-1 or P-selectin binding, suggesting that either Glycoprotein I-IX-V-dependent adhesion or von Willebrand Factor activity may have been activated to increase adhesiveness. Preserved platelet reactivity appears to be critical because platelet aggregation defects, even within the low-normal range, are strongly associated with mortality in trauma patients 6. Similar trend towards shortened high-shear closure times using the PFA-100 was found by Jacoby et al., when comparing trauma patients to healthy controls, indicating a degree of platelet activation after injury [22]. Preserved maximal thrombin generation in plasma in Cluster 1 may have supported adequate platelet adhesion/aggregation and clot formation in spite of fibrinolysis with moderate fibrinogen depletion.

All trauma clusters in this cohort demonstrated significant fibrinolytic activation by D-Dimer compared to normal healthy controls. D-Dimers were lowest in Cluster 2, and were increased nearly 4-fold in Cluster 1 and 6-fold in Cluster 3 relatively. These differences were not statistically significant, likely due to the limited sample size. However, this trend does lend support to different degrees of fibrinolytic regulation after trauma. Moore et al., recently found similar results in which three distinct clot lysis responses were seen in trauma patients, one of which was fibrinolytic shutdown [23] Using D-Dimer, we found that lysis was reduced, but not shut down in Cluster 2 compared to healthy controls. Interestingly, ADP-activated TEG-PM was also normal in this cluster, suggesting that adequate platelet-induced clot contraction may also contribute to fibrinolytic resistance after trauma. Nevertheless, fibrinolytic activation was present and associated with coagulopathy, possibly from either the presence of fibrin formed at injured tissue, from increased tPA concentration from endothelial release, or PAI-1 inhibition by aPC 3-5.

Limitations

This study is limited in several ways. The primary limitation is its small sample size. This was primarily due to our limiting the study to severely-injured trauma patients that could yet be salvaged. Thus the exclusion of massively-injured subjects not expected to live regardless of treatment may have minimized the effects of fibrinolysis in this cohort and other cohorts may not cluster similarly. We can also only provide associations between measured parameters and cannot infer causality from this study. The use of Kaolin-activated TEG may have also obscured subtle changes in TEG clot onset R time thus affecting our interpretation of the results. We also did not measure components of the protein C pathway or endothelial activation and/or dysfunction in this study. Understanding these components is critical to understanding the biochemical response to trauma and bleeding after trauma and should be incorporated in future HCA efforts. Another limitation is retained colinearity between variables selected for HCA. Specifically, multiple tests of the platelet ADP receptor activation response may have added bias to the clustering results. Clustering may also have been affected by our excluding subjects not expected to live for 72 hours. This exclusion criterion introduces a degree of survival bias that should be considered when generalizing these results. This is the initial attempt at HCA in an undifferentiated trauma cohort that provides new insight into the various hemostatic responses to trauma. Therefore, our results require further confirmation in larger trauma cohorts. In addition, further specific analysis of the behavior of the individual hemostatic and inflammatory components measured in this study are required and are underway.

CONCLUSION

Hierarchical Clustering Analysis identified 3 types of distinct hemostatic responses in Emergency Department trauma patients. Further investigations into hemostatic mechanisms after trauma are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the U.S. Defense Health Program, U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command grant W81XWH-11-2-0089. N. J. White is supported in part, by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (grant KL2 TR000421), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Departments of the Army and Defense, or the US Government, and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCATS or NIH.

Footnotes

Addendum

N. J. White was responsible for study concept and design, data analysis/interpretation, and primary manuscript writing. D. Contaifer and N. J. White performed hierarchical clustering analysis and contributed to data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing. E. J. Martin contributed to data collection, data interpretation, and manuscript review. J. C. Newton, B. M. Mohammed, and J. L. Bostic contributed to data collection, critical data interpretation and manuscript review. G. M. Brophy, B. D. Spiess, and A. E. Pusateri contributed to study concept and design, data interpretation, and critical manuscript review. K. R. Ward and D. F. Brophy were responsible for study management, critical writing and review of the manuscript, and final approval of the published version.

Conflict of Interest

N. J. White reports grants from iTrauma Care Inc., Life Science Discovery Fund, Coulter Foundation and KITECH; and personal fees from Vidacare and CSL Behring, outside the submitted work. In addition, N. J. White has a patent from University of Washington licensed to Stasys Medical Corp for a platelet diagnostic device, and a patent from University of Washington for a hemostatic biopolymer.

References

- 1.Jenkins DH, Rappold JF, Badloe JF, Berséus O, Blackbourne L, Brohi KH, Butler FK, Cap AP, Cohen MJ, Davenport R, DePasquale M, Doughty H, Glassberg E, Hervig T, Hooper TJ, Kozar R, Maegele M, Moore EE, Murdock A, Ness PM. Trauma hemostasis and oxygenation research position paper on remote damage control resuscitation: definitions, current practice, and knowledge gaps. Shock. 2014;41:3–12. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brohi K, Singh J, Heron M, Coats T. Acute traumatic coagulopathy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2003;54:1127–1130. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000069184.82147.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, Matthay MA, Mackersie RC, Pittet J. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: initiated by hypoperfusion: modulated through the protein C pathway? Annals of Surgery. 2007;245:812–818. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000256862.79374.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardenas JC1, Matijevic N, Baer LA, Holcomb JB, Cotton BA, Wade CE. Elevated tissue plasminogen activator and reduced plasminogen activator inhibitor promote hyperfibrinolysis in trauma patients. Shock. 2014;41:514–21. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oshiro A, Yanagida Y, Gando S, Henzan N, Takahashi I, Makise H. Hemostasis during the early stages of trauma: comparison with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care. 2014;3:R6. doi: 10.1186/cc13816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kutcher ME, Redick BJ, McCreery RC, Crane IM, Greenberg MD, Cachola LM, Nelson MF, Cohen MJ. Characterization of platelet dysfunction after trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:13–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318256deab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roumen RM, Hendriks T, van der Ven-Jongekrijg J, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Sauerwein RW, van der Meer JW, Goris RJA. Cytokine patterns in patients after major surgery, hemorrhagic shock, and severe blunt trauma. Ann Surg. 1993;6:769–776. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199312000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogner V1, Keil L, Kanz KG, Kirchhoff C, Leidel BA, Mutschler W, Biberthaler P. Very early posttraumatic serum alterations are significantly associated to initial massive RBC substitution, injury severity, multiple organ failure and adverse clinical outcome in multiple injured patients. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:284–91. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-14-7-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu CH1, Harris JE, Davie EW, Chung DW. Characterization of the 5'-flanking region of the gene for the alpha chain of human fibrinogen. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28342–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson PI, Sørensen AM, Perner A, Welling KL, Wanscher M, Larsen CF, Ostrowski SR. High sCD40L levels early after trauma are associated with enhanced shock, sympathoadrenal activation, tissue and endothelial damage, coagulopathy and mortality. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(2):207–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haywood-Watson RJ, Holcomb JB, Gonzalez EA, Peng Z, Pati S, Park PW, Wang W, Zaske AM, Menge T, Kozar RA. Modulation of syndecan-1 shedding after hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkhin P. Grouping Multidimensional Data. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2006. A Survey of Clustering Data Mining Techniques; pp. 25–71. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Draisma HH, Reijmers TH, Meulman JJ, van der Greef J, Hankemeier T, Boomsma DI. Hierarchical clustering analysis of blood plasma lipidomics profiles from mono- and dizygotic twin families. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:95–101. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen MJ1, Grossman AD, Morabito D, Knudson MM, Butte AJ, Manley GT. Identification of complex metabolic states in critically injured patients using bioinformatic cluster analysis. Crit Care. 2010;14:R10. doi: 10.1186/cc8864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schöchl H, Frietsch T, Pavelka M, Jámbor C. Hyperfibrinolysis after major trauma: differential diagnosis of lysis patterns and prognostic value of thromboelastometry. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2007;67(1):125–131. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31818b2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mammen EF1, Comp PC, Gosselin R, Greenberg C, Hoots WK, Kessler CM, Larkin EC, Liles D, Nugent DJ. PFA-100 system: a new method for assessment of platelet dysfunction. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1998;24:195–202. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Paola J1, Federici AB, Mannucci PM, Canciani MT, Kritzik M, Kunicki TJ, Nugent D. Low platelet alpha2beta1 levels in type I von Willebrand disease correlate with impaired platelet function in a high shear stress system. Blood. 1999;93:3578–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milligan GW. Clustering validation: results and implications for applied analyses. Clustering and Classification. 1996:341–375. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraley C, Raftery AE. Model-based clustering, discriminant analysis, and density estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2002;97:611–631. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branco BC, Inaba K, Ives C, Okoye O, Shulman I, David JS, Schöchl H, Rhee P, Demetriades D. Thromboelastogram evaluation of the impact of hypercoagulability in trauma patients. Shock. 2014;41:200–7. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davenport R, Manson J, De'Ath H, Platton S, Coates A, Allard S, Hart D, Pearse R, Pasi KJ, MacCallum P, Stanworth S, Brohi K. Functional definition and characterization of acute traumatic coagulopathy. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2652–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182281af5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagemo JS, Stanworth S, Juffermans NP, Brohi K, Cohen M, Johansson PI, Røislien J, Eken T, Næss PA, Gaarder C. Prevalence, predictors and outcome of hypofibrinogenaemia in trauma: a multicentre observational study. Crit Care. 2014;18:R52. doi: 10.1186/cc13798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman M, Monroe DM., 3rd A cell-based model of hemostasis. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:958–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacoby RC, Owings JT, Holmes J, Battistella FD, Gosselin RC, Paglieroni TG. Platelet activation and function after trauma. J Trauma. 2001;51:639–47. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200110000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore HB, Moore EE, Gonzalez E, Chapman MP, Chin TL, Silliman CC, Banerjee A, Sauaia A. Hyperfibrinolysis, physiologic fibrinolysis, and fibrinolysis shutdown: the spectrum of postinjury fibrinolysis and relevance to antifibrinolytic therapy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(6):811–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]