Abstract

Purpose

The adoptive cell transfer (ACT) of CD8+ T cells is a promising treatment for advanced malignancies. Lymphodepletion prior to ACT enhances IFN-γ+CD8+ T cell (Tc0) mediated tumor regression. Yet, how lymphodepletion regulates the function and antitumor activity of IL-17A+CD8+ T cells (Tc17) is unknown.

Experimental Design

To address this question, pmel-1 CD8+ T cells were polarized to secrete either IL-17A or IFN-γ. These subsets were then infused into mice with B16F10 melanoma that were lymphoreplete (no TBI), or lymphodepleted with non-myeloablative (5 Gy) or myeloablative (9 Gy requiring hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) TBI. The activation of innate immune cells and function of donor T cell subsets was monitored in these preconditioned mice.

Results

Tc17 cells regress melanoma in myeloablated mice to a greater extent than in lymphoreplete or non-myeloablated mice. TBI induced functional plasticity in Tc17 cells causing conversion from IL-17A to IFN-γ producers. Additional investigation revealed that Tc17 plasticity and antitumor activity was mediated by IL-12 secreted by irradiated host dendritic cells. Neutralization of endogenous IL-12 reduced the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells in myeloablated mice, while ex vivo priming with IL-12 enhanced their capacity to regress melanoma in non-myeloablated animals. This, coupled with exogenous administration of low dose IL-12, obviated the need for host preconditioning creating curative responses in non-irradiated mice,

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that TBI-induced IL-12 augments Tc17 cell-mediated tumor immunity and underline the substantial implications of in vitro preparation of antitumor Tc17 cells with IL-12 in the design of T cell immunotherapies.

Keywords: Lymphodepletion, IL-12, Tc17, Adoptive T cell Transfer, Cancer Immunotherapy

Introduction

The tumor microenvironment is rife with immune cells and secreted factors that hinder antitumor T cell function [1-3]. Lymphodepletion with total body irradiation (TBI) prior to transfer of tumor-infiltrating or gene-engineered T cells improves treatment outcome in cancer patients [4]. Lymphodepletion augments the function of transferred CD8+ T cells by depleting immunosuppressive host cells, such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), regulatory T cells (Tregs) and other cells that compete for homeostatic γ-chain cytokines such as natural killer cells and non-tumor-specific T cells [5-7]. Lymphodepletion also enhances the antitumor activity of CD8+ T cells by activating innate immune cells via microbial translocation, a process that promotes the liberation of gut microbes from the compromised bowel into the blood [8]. Recent findings revealed that activated dendritic cells (DCs) from lymphodepleted patients secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IL-23, which further improve the function of human tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells [9]. Preclinical work has demonstrated that lymphodepletion resets DC homeostasis and increases their capacity to secrete IL-12, while reducing their ability to produce IL-10, resulting in better T cell priming and antitumor responses [10]. Increasing the intensity of lymphodepletion from a non-myeloablative to a myeloablative regimen (which requires stem cell transplantation) further enhances the treatment efficacy of infused T cells, eliciting an objective response rate of >70% of melanoma patients [11]. While the role of lymphodepletion on IL-2-expanded CD8+ T cells (Tc0 – i.e. classic IFN-γ+CTLs) is well studied, how and to what extent lymphodepletion regulates the plasticity, phenotype and antitumor activity of IL-17A-producing CD8+ T cells (Tc17) remains unclear. Given that murine and human IL-17A-producing T cells have shown preclinical promise in adoptive cell transfer (ACT) therapies [12-14], it is important to understand how lymphodepletion regulates antitumor Tc17 cells.

Certain CD4+ T helper (Th) subsets display considerable functional plasticity; that is, Th17 cells can be converted to Th1 cells or Treg cells, under distinct polarizing conditions [15]. Likewise, Th2 cells can convert into a unique IL-9-secreting subset called Th9 cells [16]. In contrast, Th1 cells are considered functionally less plastic. As Tc17 cells represent a recently described IL-17-producing CD8+ T cell population, the capacity and extent of plasticity of this subset and its consequence in tumor immunity has yet to be fully appreciated. Several labs have shown that plasticity in CD8+ Tc17 cells exist in vivo, as IL-17A-secretors convert to IFN-γ-secreting T cells in mice and promote destruction against tumors in lymphodepleted mice [14, 17-19]. Additionally, Th17 cells are able to convert to Th1 cells and induce diabetes to a greater extent in lymphopenic hosts than in non-lymphopenic animals [20]. Together, these studies suggest that host preconditioning regulates the pathogenicity of Tc17 cells. Herein, we investigate how lymphodepletion regulates the functional plasticity and antitumor capacity of Tc17 cells in mice with established melanoma.

We show that increasing the intensity of lymphodepletion from a non-myeloablative (5 Gy) to a myeloablative (9 Gy) TBI preparative regimen (which requires hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) support) accelerates the conversion of Tc17 IL-17A producers into IL-17A/IFN-γ double producers and IFN-γ single producers. Tc17 cells mediated superior tumor regression in myeloablated mice compared to lymphoreplete or non-myeloablated mice. Additional investigations revealed that TBI altered the composition of the host’s myeloid compartment including enhancing the number of host DCs, macrophages and granulocytic MDSC before their eventual disappearance. DCs particularly because activated via TBI, as indicated by their elevated expression of several co-stimulatory molecules post-irradiation. Escalating the level of irradiation also increased IL-12 and IL-23 secretion by irradiated DCs to a greater level than macrophages. As cytokines in the IL-12 family differentially regulate the function of Tc17 cells in vitro, we sought to determine how these TBI-induced cytokines (IL-12 versus IL-23) impact the plasticity and antitumor activity of Tc17 cells in vivo. Blockade of IL-12 (but not IL-23) reduced the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells in myeloablated mice. Conversely, Tc17 cells primed with IL-12 in vitro enhanced tumor regression in vivo. In vitro, Tc17 cells co-expressed RORγt and T-bet and co-secreted IFN-γ and IL-17A when primed with IL-12. Of clinical significance, administration of IL-12 to lymphoreplete (non-irradiated) mice further enhanced the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells (in vitro primed with IL-12), leading to long-term cures in mice without the need for lymphodepletion. These studies suggest that TBI-induced IL-12 enhances Tc17 plasticity and antitumor activity, a finding that may have a role in the cellular therapy of cancer.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Tumor lines

Pmel-1/Thy1.1 TCR-transgenic and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were housed in the Hollings Cancer Center vivarium and maintained in compliance with the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). The experimental procedures herein were approved by IACUC. The B16F10 tumor line was obtained as a gift from Dr. Nicholas Restifo at the National Cancer Institute.

Cell preparation and culture

Splenocytes were harvested from Vβ13+ Pmel-1/Thy1.1 TCR transgenic mice. Cells were cultured in complete medium (CM) consisting of RPMI 1640 (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS (Atlas Biologicals), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% Na pyruvate, 1% nonessential amino acids, 0.1% HEPES, 1% penicillin, 1% streptomycin, and 0.1% 2-ME. Pmel-1 splenocytes were stimulated with 1μM human gp10025-33 peptide (KVPRNQDWL) in 48 well plates (1 mL media containing 1 × 106 cells/well) and polarized on day 0 towards Tc0 (100 IU/mL rhIL-2) or Tc17 (100 ng/mL rhIL-6, 30 ng/mL rhTGF-β, 10 μg/mL anti-mouse IL-4, 10 μg/mL, anti-mouse IFN-γ). T cells were primed on day 1 or 2 by adding rmIL-12 (40 ng/mL) or rmIL-23 (60 ng/mL) where indicated. Cells were split every day starting from day 3 and Tc17 cells supplemented with 20 IU/mL rhIL-2 while Tc0 cells continue to be expanded with 100 IU/mL rhIL-2. Distinct subsets were harvested on the days indicated and used for flow cytometric analysis or in vivo studies.

Flow Cytometry

From mice given different levels of TBI for 12 hours to 3 days, host myeloid cells (CD11b+) from spleen were stained with anti-CD11b-PE, and gated for dendritic cells with anti-CD11c-APC and anti-MHCII-PercpCy55, macrophages with anti-F4/80-FOTC, and myeloid derived suppressor cells with anti-Ly6C-PeC7, and anti-Ly6G-v450. Surface stain for co-stimulatory ligands was performed with anti-CD86-PE, anti-CD80-FITC, anti-CD70-APC, anti-ox40L-PerCP, anti-4-1BBL-v450, anti-ICOSL-PE, and anti-H-2Db (Biolegend). Surface staining of Pmel-1 cells were stained with anti-Vβ13-APC (BD Biosciences) anti-CD62L-FITC, anti-CD44-PerCpCy5.5, anti-IL-17A-PE, anti-IFN-γ-v450, anti-TNF-α-PECy7 and anti-IL-10-FITC (Biolegend) on day 6. For all intracellular staining of cytokines and transcription factors (RORγt-PE and T-bet-FITC; eBiosciences), cultured Pmel cells were restimulated with 1μM human gp10025-33 peptide using irradiated splenocytes (1:10 Pmel:Irradiated splenocytes) from C57BL/6 mice for 5 hours. Monensin (Biolegend) was added after one hour of stimulation with the peptide. After surface staining, intracellular staining with antibodies was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol using Fix and Perm buffers (Biolegend). Data were acquired on FACSVerse or Accuri (BD Biosciences). All data was analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Adoptive cell transfer

Tumor therapy was performed as described earlier [21]. Briefly, 8-week-old mice were injected subcutaneously with 3 × 105 B16F10 tumor cells. Lymphopenia was induced by giving total body irradiation (TBI) at either a 5 Gy (non-myeloablative) or 9 Gy (myeloablative) dose to tumor-bearing mice one day prior to Pmel-1 CD8+ T cell transfer (day 8). HSCs, given to mice treated with 9 Gy TBI, were extracted from the bone marrow by lineage depletion with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin; Dynal Biotech) against biotin-labeled antibodies (γδ T cell receptor, αβ T cell receptor, CD4, CD8a, NK1.1, Gr-1, B220, Ter-119, CD2, CD11b; BD Biosciences) followed by a c-kit enrichment with CD117 Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and cultured for 18 hours in 10% DMEM with 50ng rmIL-3, 500ng rmIL-6, and 500ng rmCSF (PeproTech); 1 × 105 cells were administered one day post-irradiation. The mice were treated via adoptive transfer of in vitro activated Pmel-1 T cells programmed towards a Tc0 or Tc17 [22]). In other experiments, mice were lymphodepleted with a non-myeloablative (5 Gy) preparative regimen one day before adoptive transfer (Day 4) and treated with Tc17 alone or primed with IL-12 or IL-23. Serial tumor measurements were obtained and tumor area was calculated by multiplying the perpendicular diameters, then plotted.

Tissue Distribution Analysis

For assays determining tissue distribution of transferred Vβ13+ T cell subsets, mice with B16F10 tumor that had received differing levels of TBI preconditioning and treated with either pmel-1 Tc0 or Tc17 cells were sacrificed 12 hours or 5 days post T cell infusion. Spleens and tumor were harvested and processed by mechanical disruption. Tumors required 30 min incubation with collagenase II at a concentration of 7.5μg/mL prior to tissue disruption. Single cell suspensions from the organs were stained for transferred (Pmel-1) cells and host myeloid cells.

In vivo cytokine neutralization

Neutralizing antibodies against murine IL-12p35 (MMp35A1.6; eBioscience) or IL-23p19 (AF1619; R&D systems) were used as previously published [13] or as prescribed on the website. Tumor-bearing C57/BL6 mice were treated via adoptive transfer of pmel-1 Tc17 cells. Beginning at 0 hours post-transfer, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100μg neutralizing antibodies and repeated every other day for 5 cycles. The control group received isotype-matched antibody.

Results

Lymphodepletion augments the functional plasticity of antitumor Tc17 cells

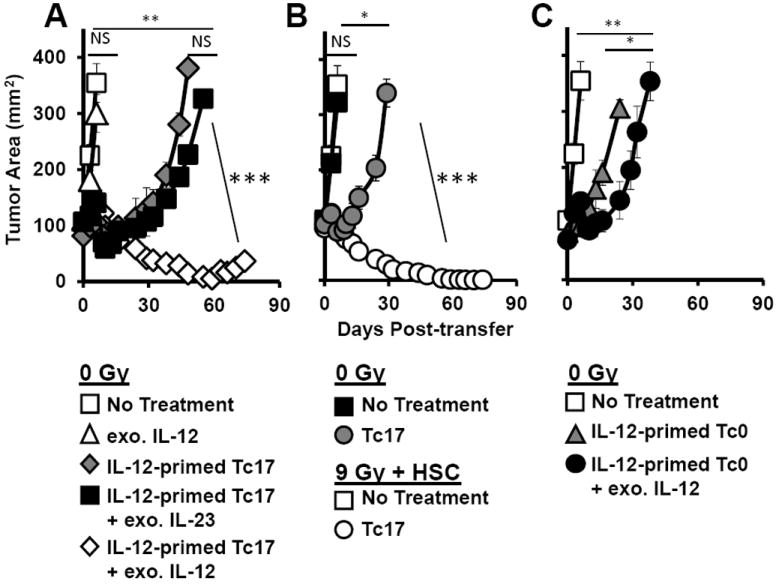

A non-myeloablative preparative regimen consisting of 5 Gy total body irradiation (TBI) prior to adoptive cell transfer (ACT) of IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells (Tc0), vaccination with vaccinia virus hgp10025-33 and bolus IL-2 induces regression of established B16F10 melanoma in mice [5]. Increasing lymphodepletion to a myeloablative regimen requiring 9 Gy TBI and stem cell support augments ACT therapy without the need for vaccination [21]. (Vaccine independence may be a key feature in the translation of these findings to humans, as vaccines for transferred T cells are not always available.) The mechanisms by which patient preconditioning with TBI enhances ACT treatment outcome is multifaceted, consisting of depleting 1) host lymphocytes that act as cytokine sinks (homeostatic cytokines are essential for the engraftment and expansion of infused T cells), 2) suppressive regulatory T cells and 3) myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) within the tumor while concomitantly activating 4) antigen presenting cells (APCs) of the innate immune system [8, 23]. While lymphodepletion augments the engraftment, function and antitumor activity of infused Tc0 cells, it is unclear how and to what extent different intensities of host preconditioning impacts the antitumor properties of IL-17A-polarized CD8+ T cells (Tc17), a lymphocyte subset that has shown promise in preclinical tumor models [14]. We hypothesized that increasing the level of host preconditioning would augment the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells to a greater extent than Tc0 cells. To test this idea, we pre-conditioned mice bearing 7 day old B16F10 melanoma tumor with either non-myeloablative (5 Gy) or myeloablative (9 Gy plus 104 hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) lymphodepletion regimens one day before transfer of pmel-1 Tc0 or Tc17 cells (pmel-1 cells: TCR Tg reactive against the tumor antigen gp100). Lymphoreplete mice were used as a control (0 Gy). Mice were not vaccinated with hgp10025-33-expressing vaccina virus, but were treated with bolus high dose IL-2. We found that adoptive transfer of pmel-1 CD8+ T cells programmed to a Tc17 phenotype mediated greater regression of melanoma than pmel-1 Tc0 cells in all conditioning regimens (Fig. 1A-C). Moreover, a myeloablative regimen (9 Gy + HSC) was superior to non-myeloablative preconditioning (5 Gy) in augmenting the antitumor activity of transferred pmel-1 Tc17 cells, resulting in curative responses in myeloablated mice (9 Gy + HSC>5 Gy, Fig. 1B-C).

Figure 1.

The functional plasticity and antitumor activity of adoptively transferred Tc17 cells is enhanced in mice preconditioned with a myeloablative preparative regimen. A-C, C57BL/6 mice were injected with 3×105 B16F10 melanoma. After 10 days, these mice were infused with either ten million Tc17 or Tc0 cells and high dose rhIL-2 after either A, no irradiation (0 Gy), B, non-myeloablative 5 Gy TBI, or C, myeloablative 9 Gy TBI with hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) one day prior to transfer. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (mean ± SEM; n=5 mice per group). * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001, one way repeated measures ANOVA. Ratio of donor Vβ13 D, Tc0 or E, Tc17 cells to host CD8+ T cells in the tumor of mice given differ levels of TBI. F, IFN-γ and IL-17 production by pmel-1 Tc17 or Tc0 cells before and after transfer into mice given increasing levels of TBI (days -1, 2 and 20). Data representative of 3 independent experiments, n=3 mice per group.

Given that pmel-1 Tc17 cells mediate superior antitumor responses in myeloablated mice than Tc0 cells (Fig. 1C), we hypothesized that Tc17 cells traffic to the tumor more efficiently than Tc0 cells. We also posited that donor Tc17 cells prevailed at a higher ratio to remaining inhibitory host cells (i.e. host CD8, CD4 and NK cells) than donor Tc0 cells in myeloablated mice. To test this concept, we evaluated the impact of a nonmyeloablative (5 Gy) versus myeloablative (9Gy+HSC) preparative regimen on the engraftment of transferred pmel-1 Tc0 or Tc17 cells to the remaining host cells in the tumor of mice. Congenic marker Vβ13 was used to distinguish pre-activated donor Pmel-1 Tc0 or Tc17 cells from the ablated host cells in mice that received TBI (Fig. 1D). As Wrzesinski et al. reported [21, 24], we also found that transferred pmel-1 Tc0 prevailed at a higher ratio to remaining host CD8+T, CD4+T and NK cells in the tumor of mice receiving myeloablative TBI with HSC transplant (9 Gy + HSC) when compared with mice receiving no irradiation (0 Gy) or a nonmyeloablative regimen (5 Gy) (Fig. 1D and Supplemental Fig. S1). In contrast to our hypothesis, transferred pmel-1 Tc17 cells trafficked to the tumor at a comparable ratio against host CD8+ T cells as pmel-1 Tc0 cells (Fig. 1D-E) in all regimens. Interestingly, only in the myeloablative setting (9 Gy + HSC) did transferred Tc17 cells reside in the tumor at a slightly higher ratio to host CD4+ T and NK cells compared to transferred Tc0 cells (Supplemental Fig. S1). Since donor Tc17 cells prevail in the tumor over host elements as effectively as donor Tc0 cells at all three levels of host preconditioning (0, 5 and 9 Gy + HSC), it remained unclear how escalating TBI doses enhanced the antitumor activity of pmel-1 Tc17 cells.

We therefore sought to determine if increasing TBI enhanced the function of the transferred Tc17 cells to a greater extent than Tc0 cells in vivo. To address this question, we measured IL-17A and IFN-γ secretion by infused pmel-1 Tc17 or Tc0 cells before (day -1) and after transfer (day 2 and day 20) into mice given different TBI preconditioning regimens. Prior to transfer, pmel-1 Tc0 and Tc17 cells secreted high levels of IFN-γ and IL-17A, respectively, upon hgp10025-33 antigen re-stimulation (Fig. 1F, day 0). Further, as previously reported [21, 24], increasing the level of lymphodepletion augmented the function of pmel-1 Tc0 cells in vivo, as indicated by their increased capacity to secrete IFN-γ. On day 2 post-transfer, IFN-γ production by pmel-1 Tc0 cells was highest in mice given 9 Gy TBI (72%), followed by mice given 5 Gy TBI (61%) versus those not given TBI (54%). Pmel-1 Tc17 cells produced nominal IFN-γ but ample IL-17A two days after infusion into non-irradiated mice. Interestingly, the greatest functional plasticity of pmel-1 Tc17 cells was observed in those infused into mice pretreated with 9 Gy TBI (+HSC), as these cells dramatically converted from mainly IL-17A producers (day -1 before transfer) into those that co-secrete ample IL-17A and IFN-γ (25%) and IFN-γ alone (31%) two days after infusion (Fig. 1F, day 2). By day 20, transferred pmel-1 Tc17 cells produced no IL-17A but high amounts of IFN-γ. To our surprise, by day 20, transferred pmel-1 Tc17 cells produced more IFN-γ than pmel-1 Tc0 cells at any level of lymphodepletion (Fig. 1F). Our data shows that increasing the intensity of host preconditioning rapidly converts Tc17 cells from IL-17A to IFN-γ producers in myeloablated mice and Tc17 cells ultimately secrete more IFN-γ than Tc0 cells. This improved Tc17 functionality may account for the pronounced tumor destruction observed in myeloablated mice compared with non-irradiated or non-myeloablated mice.

Lymphodepletion enhances the activation and maturation of DCs

Because dendritic cells (DCs) are the APCs specialized for triggering T cell responses [25], we hypothesized that an increase in the activation of host DCs following TBI was responsible for initiating the functional plasticity (Fig. 1E) and antitumor activity of pmel-1 Tc17 cells in myeloablated mice (Fig. 1C). To test this idea, we first examined the fate of host DCs and macrophages in the spleens of B6 mice following host preconditioning with either a non-myeloablative (5 Gy) or myeloablative (9 Gy + HSC) preparative regimens compared to host DCs and macrophages in lymphoreplete animals (0 Gy-control). Flow cytometry analysis showed that 12 hours after TBI, the frequency of host CD11c+CD11b+ DCs and CD11b+F4/80hi macrophages increased significantly in recipient spleens (Fig. 2A). Further, increasing TBI intensity directly corresponded to greater splenic DC and macrophage density in mice (Fig. 2A). Yet, as anticipated, TBI reduced the overall cellularity of recipient spleens by 90.3% and 93.3% in mice 12 hours after given either a non-myeloablative (5 Gy) or myeloablative regimen (9 Gy + HSC), respectively (Fig. 2B). The absolute number of host DCs (but not macrophages) declined slightly 12 hours following TBI (Fig. 2C), and by day 5 >95.0% of host DCs and macrophages in the spleen were eliminated in irradiated animals (not shown). The fast depletion of host DCs following TBI was unexpected given that Tc17 cells mediate durable tumor immunity at >50 days post infusion (Fig. 1C).

Figure 2.

TBI enhances the frequency and activation status of host DCs before their disappearance. A, Frequency of CD11b+CD11chi DCs and CD11b+F4/80hi macrophages in spleens of nonirradiated, 5 Gy and 9 Gy irradiated mice. Splenocytes were isolated 12 hours after TBI. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n= 7 mice per group). B, total number of splenocytes in mice 12 hours after preconditioning with 0, 5, or 9 Gy TBI. C, absolute number of CD11b+CD11chi DCs and CD11b+F4/80hi macrophages in spleens of nonirradiated, 5, and 9 Gy irradiated mice. D, mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of H2-Db, CD86, CD80, ICOSL, 4-1BBL, OX40L, and CD70 on splenic macrophages and DCs from mice given increasingly higher levels of TBI. MFI of these molecules is detected 12 hours after TBI. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001, Student t test.

Since T cell activation is induced by maturate DCs in vivo [25], we next sought to determine if host DCs might be differentially activated following various levels of lymphodepletion but prior to their disappearance. As shown in Fig. 2D, 12 hours post TBI, host DCs from irradiated mice (5 Gy and 9 Gy + HSC) dramatically increased their expression of MHC I (H2-Db) and costimulatory ligands CD86, CD80, ICOS ligand (ICOSL), 4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL), OX40 ligand (OX40L) and CD70. To our surprise, only OX40L expression was increased in macrophages 12 hours after TBI. Collectively, our data suggest that TBI induces the activation of host DCs before their rapid elimination, but if TBI regulates the ability of pre-terminal DCs to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines on their role on transferred cells remains incompletely elucidated.

Lymphodepletion enhances the function of host dendritic cells

Preconditioning mice with 15 Gy TBI (with HSC) induces interleukin 12 (IL-12) secretion by murine DCs [26] and Huang et. al. reported that increasing the intensity of irradiation augmented IL-12 and IL-23 secretion by human DCs in vitro [9]. We therefore hypothesized that escalating TBI would also increase IL-12 and IL-23 secretion by irradiated host murine DCs, which in turn would augment the antitumor activity of transferred pmel-1 Tc17 cells in myeloablated hosts (Fig. 1C). As anticipated, splenic DCs isolated from myeloablated mice (9 Gy + HSC) secreted significantly more IL-12 and IL-23 one day following TBI than DCs from non-irradiated mice (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the amount of IL-12 and IL-23 secreted by DCs were proportionate to increased TBI. In contrast to DCs, macrophages secreted IL-12 and IL-23 due to TBI but to a markedly less amount that DCs (not shown). Our findings underscore that myeloablation augments the function of host DCs, as demonstrated by their heightened secretion of IL-12 and IL-23 compared to DCs from non-irradiated or non-myeloablated mice.

Figure 3.

Lymphodepletion induced IL-12 but not IL-23 enhances the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells in myeloablated mice. A, Levels of IL-12 and IL-23 produced by dendritic cells from spleens of mice receiving escalating doses of irradiation. One day post-irradiation, dendritic cells were sorted from splenocytes as CD11c+CD86hi from mice given 0, 5, or 9 Gy (+HSC) TBI, and dendritic cells were plated overnight in cell media. After 18 hours, supernatant from cultures was collected and analyzed via ELISA. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (n=4 mice per group). B, B16F10 tumor bearing mice received 9 Gy TBI (+HSC) were either infused or not with pmel-1 Tc17 cells. Mice were injected 0 and 24 hours post-transfer with 100 μg neutralizing antibodies against either IL-12p35 or IL-23p19 or IgG isotype control. * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001. Statistics for Fig. 3A were determined by t-test and for Fig. 3B by a one way repeated measures ANOVA.

Lymphodepletion triggers changes in MDSC subsets in tumor-bearing mice

Pmel-1 T cells engineered to secrete IL-12 eradicate melanoma when infused into mice [27]. IL-12 was found to trigger programmatic changes in dysfunctional myeloid-derived suppressor cells, in turn enhancing pmel-1 T cell-mediated tumor regression [28, 29]. Specifically, they found that IL-12 decreased monocytic CD11b+ Ly6ChiLy6Glo cells (MDSC-M) but increased granulocytic CD11b+ Ly6Chi Ly6Ghi cells (i.e. MDSC-G) in the tumor [28]. Thus, as myeloablation (9Gy+HSC) increases IL-12 secretion by host DCs, we rationalized that this regimen altered the MDSC-G and MDSC-M cell composition in myeloablated mice compared to in non-irradiated mice. Using flow cytometry, we examined the presence of these two MDSC subsets in the spleen of lymphoreplete (0 Gy), non-myelablated (5 Gy) or myelablated (9 Gy + HSC) mice 12 hours after TBI. Indeed, the frequency and absolute number of splenic MDSC-G cells was increased in myeloablated mice (9 Gy + HSC) over MDSC-M cells compared to in non-irradiated mice or in mice given a non-myeloblative regimen (Supplemental Fig. 2A and 2B). Yet, few of these subsets remained in the spleen, blood or tumor of recipient mice 5 days post TBI. Moreover, we found that TBI transiently induced MDSC-M but not MDSC-G cells to express a plethora of co-stimulatory molecules, including CD86, CD70, CD80, 4-1BBL and ICOS ligand (Supplemental Fig. S3). Collectively, our data reveal that TBI alters the balance and activation status of DCs, macrophages, MDSC subsets in vivo and hosts DCs from irradiated mice secrete high quantities of IL-12 and IL-23.

TBI-induced IL-12 augments the antitumor activity of transferred Tc17 cells

To determine if the IL-12 or IL-23 secreted by DCs play a role in augmenting antitumor Tc17 activity in myeloablated mice, we first sought to determine how long activated DCs remain present and function in the irradiated animal. To monitor function, we measured when IL-12p40 (a subunit shared by both IL-12 and IL-23 [30]) was most elevated in the serum of irradiated mice. Our objective was to use this kinetic information to identify when to deplete IL-12 or IL-23 in order to determine their putative role in Tc17 cell-mediated tumor immunity in myeloablated animals. Although both 5 and 9 Gy TBI decrease the absolute number of splenic CD11c+DCs in mice by day 3 (Supplemental Fig. 4A, open diamond), a robust and transient increase in the absolute number of activated CD11chiMHCII+CD86hi DCs was observed in irradiated mice within 6-24 hours post TBI (Supplemental Fig. 4A, black square). Interestingly the peak of CD11chiMHCII+CD86hi DC activation was more rapid in mice given a myeloablative (9 Gy + HSC) regimen than in mice given a non-myeloablative (5 Gy) regimen (6 hrs versus 24 hours, respectively-Supplemental Fig. 4A). Yet, as shown in Supplemental Fig. 4B, IL-12p40 was detected within 6-12 hours in the serum of mice given either TBI regimen but was significantly lower in non-irradiated mice (0 Gy-basal is <100pg/ml). Moreover, significantly higher IL-12p40 was detected in the serum of mice given a myeloablative preparative regimen than in the serum of mice from non-myeolablative mice. Using this information, we next sought to determine if TBI-induced IL-12 or IL-23 cytokines were responsible for the improved antitumor activity of the transferred pmel-1 Tc17 cells in myeloablated mice. To do this, we neutralized IL-12 or IL-23 with IL-12p35 or IL-23p19 (subunits distinctly expressed on IL-12 or IL-23, respectively) in mice pre-conditioned with a myeloablative therapy prior to infusion of pmel-1 Tc17 cells. IL-12 appeared important for Tc17 cell-mediated tumor immunity in myeloablated treated mice, as melanoma regression was appreciably compromised in mice given neutralizing IL-12p35 antibodies compared to treatment groups given an isotype control (Fig. 3B). Unexpectedly, despite the role of IL-23 as a key maintenance signal for Th17 cell function and expansion [31], neutralizing this cytokine (IL-23p19) did not impair Tc17 treatment in myeloablated mice (Fig. 3B). IL-12 or IL-23 neutralization did not impact treatment outcome in mice that were not infused with Tc17 cells (Fig. 3B). Our data suggests that TBI-induced IL-12, at least in part, augments Tc17 cell-mediated tumor regression in myeloablated mice.

IL-12 and IL-23 distinctly regulate the functional plasticity, cytotoxicity and transcription factor profile of adoptive transferred tumor-reactive Tc17 cells

Given that TBI-induced IL-12 augments pmel-1 Tc17 cell antitumor activity in myeloablated mice (Fig. 3B), we surmised that if Tc17 cells were in vitro primed with IL-12 that they would effectively regress melanoma in mice and that these mice would require less lymphodepletion. We also posited that IL-12 would bolster the functional plasticity of pmel-1 Tc17 cells in vitro, similar to that seen with pmel-1 Tc17 cells from myeloablated mice (9 Gy TBI + HSC, Fig. 1F, day 2). As expected, IL-12-primed Tc17 cells were highly poly-functional, as 74% secreted IL-17A, 52% secreted IFN-γ and 41% co-secreted IL-17A plus IFN-γ (Fig. 4A, Tc17 middle panel). Conversely, IL-23-primed Tc17 cells maintained high IL-17A production (66%) and suppressed IFN-γ (8%) (Fig. 4A, Tc17-right bottom panel). In contrast to Tc17 cells, at this time point, neither IL-12 nor IL-23 priming enhanced the ability of pmel-1 Tc0 cells to co-secrete IL-17A and IFN-γ (Fig. 4A, Tc0 panels). Our data reveal that IL-12 triggers the functional plasticity of Tc17 cells in vitro, as demonstrated by their robust capacity to co-secrete IL-17A and IFN-γ.

Figure 4.

IL-12 and IL-23 distinctly regulate the functional plasticity, cytotoxicity and transcriptional profile of pmel-1 Tc0 and Tc17 cells. A, IL-17A and IFN-γ secretion by pmel-1 Tc0 and Tc17 cells primed with either IL-12 or IL-23 was analyzed on day 5 post expansion by flow cytometry. Results representative of 5 independent experiments with similar results. B, Intracellular stain comparing IFN-γ secretion with granzyme B production by pmel-1 Tc0 and Tc17 cells primed with IL-12 or IL-23-cells were analyzed on day 6 post expansion. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments. C, RORγT and T-bet transcription factor expression was analyzed day 5 in Tc0 and Tc17 cells primed with IL-12 or IL-23. Results representative of 5 independent experiments. D, Percent Tc0 and Tc17 cells expressing RORγT and/or T-bet after priming with IL-12 or IL-23 on day 5 as displayed in bar graph form. Data representative of 3 independent experiments; * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001, two tail t-test, error bars represent standard error. E, Memory phenotype of pmel-1 Tc0 and Tc17 cultures based on CD44 and CD62L expression as analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments.

Tc0 cells are more cytotoxic than Tc17 cells in vitro [14]. Thus, we next sought to determine how IL-12 and IL-23 regulate the cytotoxicity of Tc0 versus Tc17 cultures by measuring their release of Granzyme B. We found that priming Tc0 cells with IL-12 or IL-23 only marginally increased the population of Granzyme B/IFN-γ double producers (76% unprimed vs. 84% primed) and all Tc0 cultured cells secreted high amounts of Granzyme B (Fig. 4B). Unprimed Tc17 cells by contrast expressed low basal levels of Granzyme B (20%), and priming with IL-12 enhanced Granzyme B secretion (38%) with the majority of these cells also producing IFN-γ (23 of 38%). Conversely, IL-23 did not induce Tc17 cells to produce Granzyme B compared to unprimed Tc17 cells (22% vs. 20%) (Fig. 4B). Our data reveal that IL-12 increases the cytotoxicity of Tc17 cells, as revealed by their marked gain in IFN-γ and Granzyme B production.

We next sought to investigate how IL-12 and IL-23 regulates the expression of transcription factor RORγt and T-bet in pmel-1 Tc17 cells. The transcription factor T-bet is important for sustaining IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells while transcription factor RORγt is well known to promote IL-17A secretion by Tc17 cells [32, 33]. Using flow cytometry, we found that classic Tc17 cells expressed high levels of RORγt and nominal T-bet. Yet, IL-12 priming decreased RORγt and increased T-bet expression in Tc17 cells while IL-23 maintained RORγt (as shown by flow cytometry in Fig. 4C and in bar graph form from 3 different experiments in Fig. 4D). Conversely, Tc0 cells expressed nominal RORγt and T-bet. IL-23 did not induce RORγt expression in Tc0 cells. However, IL-12 but not IL-23 significantly increased T-bet expression in Tc0 cells (Fig. 4C and 4D). Our finding is not surprising, given that IL-12 has been reported to induce T-bet in T cells [34]. In summary, our data reveal that IL-12 and IL-23 differentially regulate RORγt and T-bet in antitumor Tc17 cells, which likely explains why they co-secrete IFN-γ and IL-17A in myelablated animals (Fig. 1F).

Given that IL-12 increases Tc17 cytotoxicity, we wanted to determine if IL-12 promoted a shift in the Tc17 cultures from a less differentiated central (CD62LhiCD44hi) memory phenotype to a more differentiated effector (CD62LloCD44hi) memory phenotype [35]. Indeed, Tc17 cells displayed an effector memory phenotype while Tc0 cells exhibited central memory profile, as previously reported [13, 14]. Interestingly, IL-12 increased the frequency of central memory cells in the Tc0 but not Tc17 cell culture (Fig. 4E). Collectively, our data reveal that priming Tc17 cells with IL-12 increases their functional and transcriptional plasticity in vitro but does not alter their memory profile.

IL-12 priming augments the antitumor potential of Tc17 cells

Given that TBI induces host DCs to secrete high IL-12 and IL-23 levels in heavily pretreated mice (9 Gy TBI + HSC) (Fig. 3A), we wished to assess whether priming Tc17 cells with IL-12 or IL-23 in vitro would augment their antitumor activity in mice preconditioned with a lower intensity and less toxic level of lymphodepletion (i.e. 5 Gy TBI). To address this idea, we transferred Tc17 cells that were primed with IL-12 or IL-23 in vitro into melanoma tumor-bearing mice conditioned with a non-myeloablative (5 Gy TBI) preparative regimen. As an in vitro vaccination, pmel-1 subsets were re-stimulated with irradiated splenocytes presenting hgp10025-33 peptide prior to transfer into recipient mice [22]. Tc17 cells primed with IL-23 did not induce significant tumor regression in the animals; in fact, following a period of relative stasis tumor area increased (Fig. 5A). In contrast, Tc17 cells primed with IL-12 mediated tumor regression to a greater extent than unprimed or IL-23-primed Tc17 cells (Fig. 5A). To determine if priming Tc17 cells with IL-12 impacted their ability to engraft in the tumor or lymphoid tissues, we harvested spleens from preconditioned mice that had received Tc17 cells primed or not with IL-12. As shown in Fig. 5B, we found that IL-12 priming augmented trafficking of pmel-1 Tc17 cells to the tumor over host CD8, CD4 or NK cells in myeloablated mice. Interestingly, we found that the combination of both host preconditioning with 5 Gy TBI and priming Tc17 cells with IL-12 increased tumor infiltration of pmel-1 Tc17 cells over host cells to ratios similar or greater than those seen in the tumors of 9 Gy preconditioned hosts treated with Tc17 cells (Fig. 5B), but that IL-12 priming did not increase the engraftment of Tc17 cells in the spleens of 5 Gy preconditioned hosts (Supplemental Fig. S5). These data reveal that priming Tc17 cells in vitro with IL-12 augments their capacity to migrate to the tumor and regress melanoma in non-myeloablated mice, in part by increasing their ability to infiltrate the tumor to levels similar to that observed by Tc17 cells infused into myeloablated hosts. These data further underscore that TBI-induced IL-12 potentiates the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells.

Figure 5.

Pmel-1 Tc17 cells primed with IL-12 by not with IL-23 traffic to the tumor and effectively mediate potent antitumor responses in vivo. A, Ten million pmel-1 Tc17 cells were primed with either IL-12 or IL-23 and then transferred into mice bearing established B16F10 melanomas. Pmel-1 Tc17 cells that were not primed with cytokines in the IL-12 family served as a control. Recipient mice were irradiated with 5 Gy TBI 12 hours prior to adoptive transfer. No adjuvant vaccination and no IL-2 support was administered. Data representative of 2 independent experiments and n=8 per group; * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001, one way repeated measures ANOVA. B, Relative infiltration of donor pmel-1 Tc17 cells to host CD8+ T cells, host CD4+ T cells, or host NK into tumors of mice preconditioned with either 0, 5, or 9 Gy TBI (+HSC) receiving Tc17 cells or preconditioned with 0, or 5 Gy TBI and receiving IL-12-primed Tc17 cells were combined, stained for donor Vβ13 to host CD8, CD4 and NK1.1 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative of 3 experiments.

Exogenous IL-12 therapy replaces a myeloablative preparative regimen

The robust antitumor response by IL-12 primed Tc17 cells in non-myeloablated hosts prompted us to question if a low and safe dose IL-12 to non-irradiated animals would replace the prior need of preconditioning the host with TBI. To answer this question, we transferred Tc17 cells primed with IL-12 into non-irradiated mice bearing B16F10 melanoma tumors and then treated them with or without exogenous IL-12 (0.3μg, injected subcutaneously) one and seven days post T cell transfer. We found that administration of exogenous IL-12 bolstered the antitumor activity of IL-12-primed Tc17 cells in non-irradiated animals (Fig. 6A). Importantly, this treatment mirrored the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells transferred into a myeloablated host (IL-12 primed Tc17 cells plus exo. IL-2 (open diamond) = Tc17 cells in 9Gy condition (open circle), Fig. 6B). It is possible that this combination treatment in non-irradiated animals was potent because IL-12 primed Tc17 cells migrated to the tumor effectively while exogenous IL-12 collapses tumor stroma via Fas induction, as reported by Kerkar and co-workers [29]. Interestingly, exogenous IL-23 treatment did not augment the antitumor activity of IL-12 primed Tc17 cells (Fig. 6A), nor did IL-23 alter tumor growth in mice not receiving cell therapy (not shown), despite its known role to promote the generation of pathogenic Tc17 cells [36]. We also found that exogenous IL-12 augmented the antitumor activity of IL-12 primed Tc0 cells (Fig. 6C) but not to the extent achieved by IL-12 primed Tc17 cells (Fig. 6A). Collectively, our data suggest that exogenous administration of IL-12 obviates the need for a myeloablative preparative regimen to eradicate melanoma, if mice are treated with tumor-reactive IL-12-primed Tc17 cells.

Figure 6.

Exogenous IL-12 mediates durable antitumor immunity in non-irradiated mice infused with IL-12-primed pmel-1 Tc17 cells. In all experiments using exogenous IL-12 and IL-23, these cytokines were given at 0.3 μg/mouse subcutaneously on day 1 and 7 following pmel-1 Tc17 cell transfer. A, Ten million IL-12-primed Tc17 cells were adoptively transferred into non-irradiated tumor bearing mice with or without exogenous IL-12 or IL-23 cytokine treatment post-transfer. Mice receiving no treatment, or only exogenous IL-12 but no T cells were used as controls. B, Ten million Tc17 cells were transferred into either non-irradiated or lymphodepleted (9 Gy + HSC) tumor-bearing hosts. Mice receiving only myeloablative TBI with HSC were used as controls. C, Ten million IL-12-primed Tc0 cells were transferred into non-irradiated tumor-bearing mice with or without exogenous IL-12 treatment. Data representative of 2 independent experiments and n=8 mice per group; * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001, one way repeated measures ANOVA.

Discussion

Host preconditioning with lymphodepletion augments the antitumor activity of infused IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells (Tc0) in mice and in humans with melanoma. Yet, the extent to which lymphodepletion impacts the fate of antitumor IL-17A+CD8+ T (Tc17) cells – an emerging subset showing great promise in ACT murine models—remains unknown. To address this, we polarized pmel-1 CD8+ T cells to secrete IL-17A or IFN-γ and infused them into melanoma-bearing mice that were either 1) not lymphodepleted (0 Gy TBI) or lymphodepleted with 2) a non-myeloablative (5 Gy TBI) or 3) myeloablative (9 Gy TBI requiring HSC) preparative regimen. We found that Tc17 cells regressed melanoma in myeloablated mice to a greater extent than in lymphoreplete or non-myeloablated mice (Fig. 1A-C). Moreover, Tc17 cells but not Tc0 cells mediated curative responses in myeloablated mice. Additional investigation revealed that Tc17 cells converted from mainly IL-17A producers into IL-17A+IFN-γ+ double producers 2 days after transfer into myeloablated mice and that these cells converted more rapidly in myeloablated mice than in lymphoreplete or non-myeloablated mice (Fig. 1F). Interestingly, lymphodepletion triggered the innate immune system, as demonstrated by an increase in the number of dendritic cells, granulocytic MDSCs, and macrophages before their disappearance (Fig. 2A and supplemental Fig. S2). Among these cells, dendritic cells showed significant increases in their co-stimulatory ligand expression after irradiation (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, they secreted the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IL-23 (Fig 3A). Interestingly, only IL-12 secreted by TBI-activated host DCs appeared to augment the plasticity and antitumor activity of transferred Tc17 cells, as blocking endogenous IL-12 but not IL-23 reduced the therapeutic efficacy of Tc17 cells in myeloablated mice (Fig. 3B). Conversely, priming Tc17 cells in vitro with exogenous IL-12 but not IL-23 enhanced their functional plasticity and capacity to regress melanoma in vivo (Fig. 4-5). Administration of low dose IL-12 to non-irradiated mice further potentiated the antitumor activity of IL-12-primed Tc17 cells (Fig. 6), leading to long-term antitumor immunity in mice without the requisite for lymphodepletion.

Given that IL-12 and IL-23 enhance immune responses to tumors [29, 37, 38] and because we found that both IL-12 and IL-23 are induced in myeloablated mice (Fig. 3A), we suspected that these cytokines were important for enhancing Tc17 cell-mediated tumor immunity in myeloablated mice. As expected, blocking IL-12 with an antibody that neutralizes IL-12p35 impaired the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells in myeloablated mice. Unexpectedly, blocking IL-23 with anti-IL-23p19 did not impair treatment outcome in myeloablated mice infused with Tc17 cells. While these data suggest that TBI-induced IL-12 but not IL-23 is responsible for augmenting Tc17-mediated tumor regression in myeloablated mice, we should proceed with caution with this interpretation as we only neutralized IL-12 or IL-23 for one week in mice following TBI. Thus, it is plausible that these cytokines were not sufficiently neutralized or that this approach did not remove all of the IL-12 or IL-23 secreted by activated host APCs that ultimately reconstituted the animal beyond the 3 days we assayed for these cytokines. Follow up studies with recipients deficient in IL-12 or IL-23 may provide more insight into weather these cytokines contribute to the antitumor activity or persistence of Tc17 cells.

To understand if TBI-induced IL-12 augmented the functional plasticity and antitumor activity of Tc17 cells, we blocked IL-12 with an antibody the binds the p35 subunit called anti-IL-12p35 (Fig. 3B). While neutralizing IL-12p35 with this antibody impaired the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells in myeloablated mice, it is worth noting that p35 is also expressed by cytokine IL-35 (a cytokine in IL-12 family composed of p35 and EBI3 subunits) [39]. Although our studies did not examine IL-35 production in irradiated animals, future studies on the role of TBI on IL-35 would be interesting in the context of ACT therapy, particularly given that IL-35 has been reported to promote cancer growth [40]. However, based on our findings, IL-12p35 has a positive therapeutic effect on Tc17 cells in vivo (Fig. 3B). Indeed, IL-12p35 has also been shown to be critical for inducing the secretion of IL-18 in vivo-which can also be key for inducing IFNγ production by T cells [41-43]. Thus in future studies, it would be of interest to know whether blocking IL-12p35 prevents IL-18 secretion, thereby impairing IFN-γ production by transferred Tc17 cells in myeloblated mice. Although it would be worthwhile to further delineate p35 for IL-12, IL-18 and IL-35 in myeloablated mice, the difficulty due to overlap with these various cytokines is appreciated. However, considering our data where Tc17 cells primed in vitro with total recombinant IL-12 drives the robust secretion of both IL-17A and IFN-γ (Fig. 4A), it should not be ruled out that the effect that is seen in vivo when blocking IL-12 is also due to other down-stream effects, such as lack of IL-18. Although blocking cytokines in vivo is complex and can likely lead to unexpected immunological outcomes, our finding imply that IL-12 plays a key role in augmenting the functional plasticity and antitumor activity of Tc17 cells in vivo.

IL-12 induces toxic side effects in humans, which has hampered its translation into the clinic [44]. To circumvent these negative side effects of IL-12 in vivo, we sought to use IL-12 in pmel-1 Tc17 cultures to enhance their function and cytotoxicity in vitro and then wash out IL-12 before infusing these cells into mice. Via this approach, we found that priming Tc17 cells with IL-12 enhanced their function and cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 4A-B) without inducing toxic side effects in the mice (Fig. 5A). Tc17 cells primed with IL-12 greatly increased their IFN-γ production (52%) compared those primed with IL-23 (8%) in Fig. 4A. Moreover, IL-12 primed Tc17 cells secreted heightened amounts of granzyme B (Fig. 4B). This increase in classical Tc1 effector molecules in Tc17 cells correlated with an induction of T-bet and suppression RORγt (Fig. 4C-D). Along with modulating T-bet, IL-12 has been reported to convert Tc17 cells to IL-17A/IFN-γ-double producer through epigenetic suppression of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) gene promoters [45, 46]. Thus, future studies that investigate the role of how TBI regulates SOCS3 as well as STAT signals in transferred Tc17 cells may shed light on their pronounced plasticity and antitumor activity in myelablated mice.

There are three reported requirements for breaking tolerance to established melanoma with pmel-1 Tc0 cells: 1) preconditioning the host with lymphodepletion; 2) transfer of effective T cells; and 3) vaccination and administration of recombinant human IL-2 [47]. Yet, high doses of IL-2 increase the generation of FoxP3+ regulatory cells (Tregs) in vivo, both in humans and mice [48]. To circumvent Treg cell generation, we did not administer IL-2 to mice infused with IL-12 or IL-23 primed Tc17 cells. IL-12 primed Tc17 cells showed greater antitumor efficacy than IL-23 primed and unprimed Tc17 cells, which we attribute to their poly-functional and enhanced capacity to traffic to the tumor over inhibitory host elements like Tregs in vivo (Fig. 5B). Tc17 cells primed with IL-23 were not as effective at killing the tumor. Collectively, our results demonstrated that IL-12 plays a crucial role in enhancing the function, cytotoxicity and tumor trafficking ability of pmel-1 Tc17 cells in vivo.

We demonstrated that mice infused with IL-12-primed Tc17 cells that were also treated with a low dose of exogenous IL-12 experienced durable antitumor responses without the normal need for host preconditioning with lymphodepletion (Fig. 6). However, these potent therapeutic results cannot be recapitulated by either 1) administration of exogenous IL-23 given to mice infused with IL-12-primed Tc17 cells or by 2) exogenous IL-12 given to mice infused with IL-12-primed Tc0 cells. Our body of work herein underscore that IL-12 is critical for potentiating the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells.

IL-12 has been shown to play an important role in modulating the tumor microenvironment both by acting on the tumor stroma itself as well as triggering programmatic changes in dysfunctional tumor-derived myeloid derived cells [49]. Likewise, we found that TBI triggered programmatic changes in the myeloid derived cells compartment of mice, including a robust yet transient induction of granulocytic MDSCs over monocytic MDSCs (Supplemental Fig. S2). In future studies, it will be interesting to determine the role of these distinct MDSC subsets in regulating T cell subsets in our ACT model of melanoma. This line of investigation would be particularly interesting given that granulocytic MDSC secrete reactive oxygen species and nominal nitric oxide (NO) whereas monocytic MDSC secrete NO but little ROS-both NO and ROS have been shown to regulate the biology of Th17 in tumor immunity and autoimmunity [50-52]. Collectively, our data show that both environmental IL-12 and the innate characteristics of Tc17 cells are required for a superior therapeutic result in non-irradiated animals. These data are important because they suggest that alternative regimens to chemotherapy or TBI, such as adjuvants that induce IL-12 secreting DCs, may be used to safely treat patients with advanced disease and promote tumor regression comparable to that seen with non-myeloablative preparative regimens. The relevance of our findings extends beyond melanoma and provides insight into mechanisms for improving the quality of T cells for passive and adoptive therapies that could treat a variety of cancers as well as infectious diseases in the clinic.

It is worth considering the impact of TBI on models of lymphodepletion, as many investigators use TBI to study lymphocyte engraftment and immunity to foreign, self and tumor tissue [53, 54]. Yet, the induction of homeostatic expansion of the T cell compartment after TBI preconditioning cannot be viewed as simply expanding to fill empty space. We and others have reported that TBI induces a complex set of events, such as microbial translocation [8], which likely plays a role in inducing the secretion of IL-12 and IL-23 from activated DC, that in turn enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells, particularly Tc17 cells.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

The adoptive cell transfer (ACT) of ex vivo expanded tumor-reactive T cells is one of the most promising approaches for the treatment of patients with advanced malignancies, such as melanoma and leukemia. Increasing the intensity of lymphodepletion prior to ACT enhances CD8+ T cells mediated-tumor regression in mice and humans. This therapy mediates objective response rates in melanoma patients of >70% and curative responses of nearly 20%. Here, we report a mechanism underlying the effectiveness of lymphodepletion via total body irradiation (TBI). We show that TBI not only creates space for the infused tumor-reactive T cells to engraft, but that TBI activates the innate immune system, thereby bolstering the functional plasticity of antitumor Tc17 cells. Pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12, but not IL-23, secreted by dendritic cells augmented the antitumor activity of Tc17 cells in irradiated animals. Moreover, IL-12 could be safely used in cultures in vitro and in vivo to recapitulate the effectiveness of TBI in non-irradiated mice infused with Tc17 cells. These data suggest that alternative regimens to chemotherapy or TBI may be used to bolster T cell based therapies and safely treat patients with advanced malignancies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NCI surgery branch for the gift of the B16F10 melanoma. This research was supported in part by the Cell Evaluation & Therapy Shared Resource, Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina (P30 CA138313).

Grant Support

This work was supported in part by NIH grant 5R01CA175061, KL2 South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research grant UL1 TR000062, ACS-IRG grant 016623-004, MUSC Start-up funds to C.M. Paulos and Jeane B. Kempner Foundation grant and ACS Postdoctoral fellowship (122704-PF-13-084-01-LIB) grant support for M.H. Nelson.

Footnotes

Authors Contributions

Conception and Design: J.S. Bowers, M.N. Nelson, S. Kundimi, C.M. Paulos

Development of Methodology: S. Kundimi, C.M. Paulos

Acquisition of Data: S. Kundimi, J.S. Bowers, L.W. Huff, K.M. Schwartz, C.M. Paulos

Analysis and Interpretation of Data: M.N. Nelson, J.S Bowers, S. Kundimi, C.M. Paulos

Writing, review and or revision of the manuscript: J.S Bowers, S. Kundimi, Paulos, C.M., M.N Nelson, S.R. Bailey, D.J Cole, M.P. Rubinstein

Administrative, technical or material support: C.M. Paulos

Study supervision: C.M. Paulos

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Shiao SL, Ganesan AP, Rugo HS, Coussens LM. Immune microenvironments in solid tumors: new targets for therapy. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2559–72. doi: 10.1101/gad.169029.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Restifo NP, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: harnessing the T cell response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:269–81. doi: 10.1038/nri3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gattinoni L, Finkelstein SE, Klebanoff CA, Antony PA, Palmer DC, Spiess PJ, et al. Removal of homeostatic cytokine sinks by lymphodepletion enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202:907–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antony PA, Piccirillo CA, Akpinarli A, Finkelstein SE, Speiss PJ, Surman DR, et al. CD8+ T cell immunity against a tumor/self-antigen is augmented by CD4+ T helper cells and hindered by naturally occurring T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:2591–601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sica A, Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1155–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulos CM, Wrzesinski C, Kaiser A, Hinrichs CS, Chieppa M, Cassard L, et al. Microbial translocation augments the function of adoptively transferred self/tumor-specific CD8+ T cells via TLR4 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2197–204. doi: 10.1172/JCI32205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang J, Wang QJ, Yang S, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Rosenberg SA, et al. Irradiation enhances human T-cell function by upregulating CD70 expression on antigen-presenting cells in vitro. J Immunother. 2011;34:327–35. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318216983d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radojcic V, Bezak KB, Skarica M, Pletneva MA, Yoshimura K, Schulick RD, et al. Cyclophosphamide resets dendritic cell homeostasis and enhances antitumor immunity through effects that extend beyond regulatory T cell elimination. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 59:137–48. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0734-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, Hughes MS, Royal R, Kammula U, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5233–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulos CM, Carpenito C, Plesa G, Suhoski MM, Varela-Rohena A, Golovina TN, et al. The inducible costimulator (ICOS) is critical for the development of human T(H)17 cells. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:55ra78. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muranski P, Boni A, Antony PA, Cassard L, Irvine KR, Kaiser A, et al. Tumor-specific Th17-polarized cells eradicate large established melanoma. Blood. 2008;112:362–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-120998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinrichs CS, Kaiser A, Paulos CM, Cassard L, Sanchez-Perez L, Heemskerk B, et al. Type 17 CD8+ T cells display enhanced antitumor immunity. Blood. 2009;114:596–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou L, Chong MM, Littman DR. Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity. 2009;30:646–55. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan C, Gery I. The unique features of Th9 cells and their products. Crit Rev Immunol. 2012;32:1–10. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v32.i1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yen HR, Harris TJ, Wada S, Grosso JF, Getnet D, Goldberg MV, et al. Tc17 CD8 T cells: functional plasticity and subset diversity. J Immunol. 2009;183:7161–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu Y, Cho HI, Wang D, Kaosaard K, Anasetti C, Celis E, et al. Adoptive transfer of Tc1 or Tc17 cells elicits antitumor immunity against established melanoma through distinct mechanisms. J Immunol. 2013;190:1873–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Hernandez Mde L, Hamada H, Reome JB, Misra SK, Tighe MP, Dutton RW. Adoptive transfer of tumor-specific Tc17 effector T cells controls the growth of B16 melanoma in mice. J Immunol. 2010;184:4215–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nurieva R, Yang XO, Chung Y, Dong C. Cutting edge: in vitro generated Th17 cells maintain their cytokine expression program in normal but not lymphopenic hosts. J Immunol. 2009;182:2565–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wrzesinski C, Paulos CM, Gattinoni L, Palmer DC, Kaiser A, Yu Z, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells promote the expansion and function of adoptively transferred antitumor CD8 T cells. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:492–501. doi: 10.1172/JCI30414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klebanoff CA, Yu Z, Hwang LN, Palmer DC, Gattinoni L, Restifo NP. Programming tumor-reactive effector memory CD8+ T cells in vitro obviates the requirement for in vivo vaccination. Blood. 2009;114:1776–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paulos CM, Kaiser A, Wrzesinski C, Hinrichs CS, Cassard L, Boni A, et al. Toll-like receptors in tumor immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5280–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wrzesinski C, Paulos CM, Kaiser A, Muranski P, Palmer DC, Gattinoni L, et al. Increased intensity lymphodepletion enhances tumor treatment efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific T cells. J Immunother. 2010;33:1–7. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181b88ffc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Louboutin JP, Zhu J, Rivera AJ, Emerson SG. Preterminal host dendritic cells in irradiated mice prime CD8+ T cell-mediated acute graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1335–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI14989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Kerkar SP, Yu Z, Zheng Z, Yang S, Restifo NP, et al. Improving adoptive T cell therapy by targeting and controlling IL-12 expression to the tumor environment. Mol Ther. 2011;19:751–9. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerkar SP, Goldszmid RS, Muranski P, Chinnasamy D, Yu Z, Reger RN, et al. IL-12 triggers a programmatic change in dysfunctional myeloid-derived cells within mouse tumors. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4746–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI58814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerkar SP, Leonardi AJ, van Panhuys N, Zhang L, Yu Z, Crompton JG, et al. Collapse of the tumor stroma is triggered by IL-12 induction of Fas. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1369–77. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lupardus PJ, Garcia KC. The structure of interleukin-23 reveals the molecular basis of p40 subunit sharing with interleukin-12. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:931–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stritesky GL, Yeh N, Kaplan MH. IL-23 promotes maintenance but not commitment to the Th17 lineage. J Immunol. 2008;181:5948–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Stemmann C, Satoskar AR, Sleckman BP, Glimcher LH. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-gamma production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 2002;295:338–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takemoto N, Intlekofer AM, Northrup JT, Wherry EJ, Reiner SL. Cutting Edge: IL-12 inversely regulates T-bet and eomesodermin expression during pathogen-induced CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2006;177:7515–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Restifo NP, Gattinoni L. Lineage relationship of effector and memory T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:556–63. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciric B, El-behi M, Cabrera R, Zhang GX, Rostami A. IL-23 drives pathogenic IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5296–305. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerkar SP, Restifo NP. The power and pitfalls of IL-12. Blood. 2012;119:4096–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-415018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Overwijk WW, de Visser KE, Tirion FH, de Jong LA, Pols TW, van der Velden YU, et al. Immunological and antitumor effects of IL-23 as a cancer vaccine adjuvant. J Immunol. 2006;176:5213–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collison LW, Workman CJ, Kuo TT, Boyd K, Wang Y, Vignali KM, et al. The inhibitory cytokine IL-35 contributes to regulatory T-cell function. Nature. 2007;450:566–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Z, Liu JQ, Liu Z, Shen R, Zhang G, Xu J, et al. Tumor-derived IL-35 promotes tumor growth by enhancing myeloid cell accumulation and angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2013;190:2415–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veenstra KG, Jonak ZL, Trulli S, Gollob JA. IL-12 induces monocyte IL-18 binding protein expression via IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2002;168:2282–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takeda K, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, Adachi O, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, et al. Defective NK cell activity and Th1 response in IL-18-deficient mice. Immunity. 1998;8:383–90. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshimoto T, Takeda K, Tanaka T, Ohkusu K, Kashiwamura S, Okamura H, et al. IL-12 up-regulates IL-18 receptor expression on T cells, Th1 cells, and B cells: synergism with IL-18 for IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1998;161:3400–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Younes A, Pro B, Robertson MJ, Flinn IW, Romaguera JE, Hagemeister F, et al. Phase II clinical trial of interleukin-12 in patients with relapsed and refractory non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5432–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mukasa R, Balasubramani A, Lee YK, Whitley SK, Weaver BT, Shibata Y, et al. Epigenetic instability of cytokine and transcription factor gene loci underlies plasticity of the T helper 17 cell lineage. Immunity. 2010;32:616–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Satoh T, Tajima M, Wakita D, Kitamura H, Nishimura T. The development of IL-17/IFN-gamma-double producing CTLs from Tc17 cells is driven by epigenetic suppression of Socs3 gene promoter. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:2329–42. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, Finkelstein SE, Surman DR, de Jong LA, Vyth-Dreese FA, et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:569–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zorn E, Nelson EA, Mohseni M, Porcheray F, Kim H, Litsa D, et al. IL-2 regulates FOXP3 expression in human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells through a STAT-dependent mechanism and induces the expansion of these cells in vivo. Blood. 2006;108:1571–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kerkar SP, Goldszmid RS, Muranski P, Chinnasamy D, Yu Z, Reger RN, et al. IL-12 triggers a programmatic change in dysfunctional myeloid-derived cells within mouse tumors. J Clin Invest. 121:4746–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI58814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:5791–802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Obermajer N, Wong JL, Edwards RP, Chen K, Scott M, Khader S, et al. Induction and stability of human Th17 cells require endogenous NOS2 and cGMP-dependent NO signaling. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1433–445. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhi L, Ustyugova IV, Chen X, Zhang Q, Wu MX. Enhanced Th17 differentiation and aggravated arthritis in IEX-1-deficient mice by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling. J Immunol. 2012;189:1639–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schluns KS, Kieper WC, Jameson SC, Lefrancois L. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naive and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:426–32. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kieper WC, Troy A, Burghardt JT, Ramsey C, Lee JY, Jiang HQ, et al. Recent immune status determines the source of antigens that drive homeostatic T cell expansion. J Immunol. 2005;174:3158–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.