Abstract

Metastatic breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths amongst women. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a highly aggressive subcategory of breast cancer and currently lacks well-defined molecular targets for effective targeted therapies. Disease relapse, metastasis, and drug resistance render standard chemotherapy ineffective in the treatment of TNBC. Since previous studies coupled β3 integrin to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis, we exploited β3 integrin as a therapeutic target to treat TNBC by delivering β3 integrin siRNA via lipid ECO-based nanoparticles (ECO/siβ3). Treatment of TNBC cells with ECO/siβ3 was sufficient to effectively silence β3 integrin expression, attenuate TGF-β-mediated EMT and invasion, restore TGF-β-mediated cytostasis, and inhibit 3-dimensional organoid growth. Modification of ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles with an RGD peptide via a PEG spacer enhanced siRNA uptake by post-EMT cells. Intravenous injections of RGD-targeted ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles in vivo alleviated primary tumor burden, and more importantly, significantly inhibited metastasis. Mice bearing orthotopic, TGF-β-pre-stimulated MDA-MB-231 tumors that were treated with RGD-targeted ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles were free of metastases and relapse after primary tumor resection and 4 weeks after release from the treatment, in comparison to untreated mice. Collectively, these results highlight ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles as a promising therapeutic regimen to combat TNBC.

Keywords: β3 Integrin, ECO/siRNA nanoparticles, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, metastasis, triple negative breast cancer

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths amongst women in the United States (1). The 5-year relative survival rate for women with localized disease is 98.6%; however, for those diagnosed with distant metastases, survival rates fall below 25% (2). Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a highly aggressive subcategory of breast cancer that lack the expression of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR), as well as HER2 amplification. Currently, there is a lack of targeted therapies for TNBCs, which renders chemotherapy as the standard of care (3-5). Although TNBC patients are initially responsive to chemotherapy, most patients relapse, and the recurrent tumor is usually highly metastatic and resistant to traditional chemotherapy, which leads to a disproportionately large number of deaths (3-6). Importantly, metastasis is associated with the aberrant activation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT; refs. 7-9), which endows cancer cells with elevated capabilities to invade and disseminate to distant sites (10). Various molecular and microenvironmental factors can induce EMT, including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). TGF-β is a pleiotropic cytokine that regulates virtually all aspects of mammary gland biology. TGF-β induces the dramatic upregulation of β3 integrin, which is essential for EMT and breast cancer metastasis (11-13). Previous work has demonstrated that functional disruption of β3 integrin inhibits TGF-β-mediated cytostasis, EMT, and invasion in vitro (11) and reduces primary tumor burden in vivo (14). Given the essential roles that β3 integrin plays in mediating breast cancer tumor progression, we hypothesize that silencing β3 integrin expression has the potential to effectively treat TNBC.

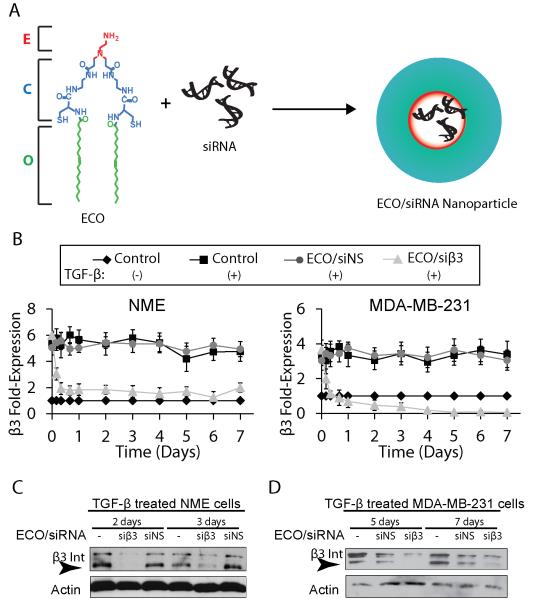

RNA interference (RNAi) is a natural biological mechanism for modulating gene expression and can be exploited to effectively regulate the expression of β3 integrin in treating TNBC. Clinical application of RNAi requires efficient delivery of therapeutic siRNA into the cytoplasm of target cells (15,16). We have recently developed a multifunctional cationic lipid-based carrier, (1-aminoethyl)iminobis[N-oleicylsteinyl-1-aminoethyl)propionamide] (ECO), which can effectively mediate cytosolic siRNA delivery and facilitate efficient gene silencing in cancer cells (Fig. 1A; refs. 15,17). ECO self-assembly with therapeutic siRNA forms stable nanoparticles that can be readily functionalized with targeting moieties to achieve targeted siRNA delivery to cancer cells. Considering the critical roles of β3 integrin in regulating EMT, proliferation and metastasis (11,14,18-20) and the unmet need for targeted therapies tailored to TNBC (3,4,21), we sought to evaluate silencing β3 integrin by targeted ECO/siRNA nanoparticles to treat metastatic breast cancer.

Figure 1.

ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles induced sustained gene silencing of β3 integrin. A, ECO forms nanoparticles with siRNA through electrostatic interactions, disulfide cross-linking and hydrophobic interactions. B, β3 integrin mRNA expression in quiescent or TGF-β stimulated (5 ng/mL, 72 hours) NME and MDA-MB-231 cells with the indicated treatment groups at 100 nM siRNA by semi-quantitative real-time PCR (n=3, mean ± SE, p≤0.01 for all time points beyond 8 hours). Western blot analysis of β3 integrin expression in quiescent or TGF-β stimulated (5 ng/mL, 72 hours) NME C, and MDA-MB-231 d) cells at the indicated time points post-nanoparticle treatment with the indicated treatment groups.

The present study demonstrates the efficacy of ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles in silencing β3 integrin expression and the consequent inhibition of TGF-β-mediated EMT and invasion in breast cancer cells in vitro. The nanoparticles were modified with a cyclic RGD peptide via a PEG spacer to improve biocompatibility and systemic target-specific delivery of the therapeutic siβ3 in vivo (11,22). The efficacy of the targeted ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles in alleviating primary tumor burden and inhibiting TNBC metastasis was determined in tumor-bearing mice following multiple intravenous injections.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

MDA-MB-231 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Grand Island, NY). NME cells are Normal Murine Mammary Gland (NMuMG; obtained from ATCC) cells that were engineered to overexpress EGFR by VSVG retroviral transduction of particles encoded from a pBabe-EGFR construct as previously described (23) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 10 μg/mL of insulin. TGF-β stimulated NME cells are a model of TNBC, which display aggressive, post-surgical primary tumor recurrence and metastatic phenotypes (23,24). Both cell lines were engineered to stably express firefly luciferase by transfection with pNifty-CMV-luciferase and selection with Zeocin (500 μg/ml; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cell lines were not independently authenticated. Early passage cells were utilized for all cell and tumor work. The following siRNAs were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA): Mouse integrin β3 sense: [GCUCAUCUGGAAGCUACUCAUCACT], Mouse integrin β3 antisense: [AGUGAUGAGUAGCUUCCAGAUGAGCUC], Human integrin β3 sense: [GCUCAUCUGGAAACUCCUCAUCACC], and Human integrin β3 antisense: [GGUGAUGAGGAGUUUCCAGAUGAGCUC].

Preparation of ECO/siRNA nanoparticles

The ECO lipid carrier was synthesized as described previously (15). ECO (MW=1023) was dissolved in 100% ethanol at a stock concentration of 2.5 mM for in vitro experiments and 50 mM for in vivo experiments. Mouse and human siRNAs were reconstituted in RNase-free water to a concentration of 18.8 μM for in vitro experiments and 25 μM for in vivo experiments. For in vitro experiments, an siRNA transfection concentration of 100 nM was used. ECO/siRNA nanoparticles were prepared at an N/P ratio of 7.7 by mixing predetermined volumes of ECO and siRNA for a period of 30 minutes in RNase-free water (pH 5.5) at room temperature under gentle agitation to enable complexation between ECO and siRNA. The total volume of water was determined such that the volume ratio of ethanol:water remained fixed at 1:20. For RGD- and RAD-modified ECO/siRNA nanoparticles, RGD-PEG3400-Mal or RAD-PEG3400-Mal (PEG, 3,400 Da, NANOCS, New York, NY) was first reacted with ECO in RNase-free water at 2.5 mol% for 30 minutes under gentle agitation and subsequently mixed with siRNA in RNase-free water for an additional 30 min. RGD-PEG3400-Mal or RAD-PEG3400-Mal were prepared at a stock solution concentration of 0.32 mM in RNase-free water. Again, the total volume of water was determined such that the volume ratio of ethanol:water remained fixed at 1:20. After the incubation, free peptide derivative was removed from RGD- and RAD-modified ECO/siRNA nanoparticles by ultrafiltration (Nanosep, MWCO = 100 K, 5000 × g, 5 min; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Conjugation of RGD-PEG3400-Mal to ECO was determined and confirmed through matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry using a Bruker Autoflex III MALDI-TOF instrument. The size of RGD-modified ECO/siRNA nanoparticles in PBS was determined by dynamic light scattering with a Brookhaven ZetaPALS Particle Size Analyzer.

Western blot analyses

Immunoblotting analyses were performed as previously described (25). Briefly, NME and MDAMB-231 cells were seeded into 6-well plates (1.5 × 105 cells/well) and allowed to adhere overnight. The cells were then incubated in the absence or presence of TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) for 3 d and then treated with ECO/siRNA complexes for 4 h in complete growth medium. At each indicated time point, detergent-solubilized whole cell extracts (WCE) were prepared by lysing the cells in Buffer H (50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM benzamidine, 10 mg/mL leupeptin, and 10 mg/mL aprotinin, pH 7.3). The clarified WCE (20 mg/lane) were separated through 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with the primary antibodies, anti-β3 integrin (1:1000; Cell Signaling) and anti-β-actin (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Flow cytometry for nanoparticle cellular uptake

Cellular uptake and intracellular delivery of ECO/siRNA and RGD-ECO/siRNA nanoparticles was evaluated quantitatively using flow cytometry. ECO/siRNA and RGD-ECO/siRNA nanoparticles were prepared with 40 nM Alexa Fluor 488-labeled siRNA (Qiagen; Valencia, CA). Approximately 2.5 × 104 NME cells were seeded onto 12-well plates and grown for an additional 24 h. The cells were transfected with ECO/siRNA nanoparticles in 10% serum media. After 4 h, the transfection media was removed and each well was washed twice with PBS. The cells were harvested by treatment with 0.25% trypsin containing 0.26 mM EDTA (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA), collected by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 min, resuspended in 500 μL of PBS containing 5% paraformaldehyde, and finally passed through a 35 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA). Cellular internalization of the nanoparticles was quantified by the fluorescence intensity measurement of Alexa Fluor 488 for a total of 1 × 104 cells per sample using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer. All the experiments were performed in triplicate and the data represent mean fluorescence intensity and standard deviation.

Semi-quantitative real-time PCR analyses

Real-time PCR studies were performed as described previously (18,25). Briefly, NME or MDAMB-231 cells (100,000 cells/well) were seeded overnight onto 6-well plates and treated with TGF-β (5 ng/mL) for 3 days upon delivery of ECO nanoparticles with a non-specific siRNA or β3 integrin-specific siRNA. At each indicated time point, total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA Synthesis System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Semi-quantitative real-time PCR was conducted using iQSYBR Green (Bio-Rad) according to manufacture’s recommendations. In all cases, differences in RNA expression for each individual gene were normalized to their corresponding GAPDH RNA signals.

Invasion and proliferation assays

Invasion assays were conducted as described previously (14). Briefly, NME cells, unstimulated (Pre-) or stimulated with TGF-β for 3 d (Post-EMT), were treated with the ECO/siRNA complexes for an additional 2 d. The cells were then trypsinized and their ability to invade reconstituted basement membranes (5 × 104 cells/well) was measured utilizing modified Boyden chambers, as previously described (18). For the proliferation assay, the NME cells were cultured (1 × 104 cells/well) in the presence (post-EMT) or absence (pre-EMT) of TGF-β (5 ng/mL) for 3 d and then treated with ECO/siRNA. Cell proliferation was determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation as previously described (11).

3-Dimensional (3D)-organotypic cultures

3D-organotypic cultures utilizing the “on-top” method were performed as described previously (25). NME or MDA-MB-231 cells, which were unstimulated (Pre-EMT) or stimulated with TGF-β (5 ng/mL) for 3 d (Post-EMT), were cultured in 96-well, white-walled, clear bottom tissue culture plates (2,000 cells/well) with 50 μL of Cultrex cushions (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) in media supplemented with 5% Cultrex. The cells were maintained in culture for 4 d with continuous ECO/siRNA treatment every 2 d. Growth was monitored by bright-field microscopy or bioluminescent growth assays (where indicated) using luciferin substrate (26,27).

Tumor growth and bioluminescent imaging (BLI)

All the animal studies were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee for Case Western Reserve University. NME cells (1 × 106 cells/mouse) were engineered to stably express firefly luciferase, and were subsequently injected into the lateral tail vein of 4-6 week old, female nude mice (nu/nu Balb/c background) after TGF-β stimulation (5 ng/mL) for 7 d. Pulmonary outgrowth was monitored and determined as described previously (28). MDA-MB-231 cells, also engineered to express firefly luciferase and stimulated with TGF-β for 7 d, were engrafted into the mammary fat pad of female nude mice. The primary tumor growth and metastatic burden were monitored and determined as described above.

In vivo therapeutic treatment

Tumor bearing mice were intravenously injected with RGD or RAD modified ECO/siRNA nanoparticles with an siRNA dose of 1.5 mg/kg every five days starting at day 17 after tumor engraftment. Surface modified ECO/siRNA nanoparticles (N/P ratio of 7.7) were prepared directly before each treatment according to the two-step formulation process described above based on the siRNA dose (1.5 mg/kg siRNA, 18.6 mg/kg ECO, 2.5 mol% PEGylation of ECO with either RGD- or RAD-functionalized PEG3400-maleimide). Each mouse (25 g body weight) received on average nanoparticles containing 37.5 μg siRNA, 464 μg ECO, and 47.7 μg of either RGD-PEG3400-mal or RAD-PEG3400-mal in 150 μL nuclease-free water at each injection.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical staining

For visualization of the actin cytoskeleton, immunofluorescent analysis was performed as previously described (14). NME cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were plated onto glass-bottom confocal dishes and allowed to adhere overnight, after which they were simultaneously stimulated with TGF-β (5 ng/mL) and treated with ECO/siRNA nanoparticles, either siβ3 or siNS at 100 nM siRNA concentration. After 48 and 72 h of simultaneous TGF-β stimulation and nanoparticle treatment, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton-X 100, stained with Alexa Flour 488 phalloidin (25 μM; Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA), and visualized under a fluorescent confocal microscope.

For immunohistochemistry, primary tumor samples were embedded in optimum cutting temperature (O.C.T.) compound (Tissue-TeK; Torrence, CA) in preparation for cryostat sectioning and immediately frozen. The samples were then sectioned, fixed in paraffin, and maintained at −80°C. The samples were stained with H&E to evaluate the presence of tumor tissue. Briefly, the samples were fixed in 10% formalin, rehydrated in 70% ethanol and rinsed in deionized water prior to hematoxylin staining. Samples were then rinsed in tap water, decolorized in acid alcohol, immersed in lithium carbonate and rinsed again in tap water. Next, the eosin counterstain was applied and slides were dehydrated in 100% ethanol, rinsed in Xylene and finally mounted on a coverslip with Biomount. For immunofluorescence detection of fibronectin, the paraffin-embedded slides were first deparaffinized using a series of washes in xylene and decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed using a pressure cooker in sodium citrate buffer (10 mM Sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) for 20 minutes. Following heat-induced antigen retrieval, the samples were blocked in TBST solution containing donkey serum and washed three times with TBST. The primary antibody (Abcam; Cambridge, MA) was applied at dilution of 1:100 in blocking solution for 1 h followed by three rinses with TBST. The Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (Jackson; West Grove, PA) was applied at a dilution of 1:5000 in blocking solution for 1 h followed by three washes with TBST and counterstained with DAPI at a dilution of 1:2500 in blocking solution. After washing with TBST and mounting in an anti-fade mounting solution (Molecular Probes; Grand Island, NY), the samples were imaged using a confocal microscope.

Statistical analyses

Statistical values were defined using unpaired Student’s t-test, with p < 0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

Results

ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles induce sustained silencing of β3 integrin

We examined the ability of ECO/β3 integrin-specific siRNA nanoparticles (ECO/siβ3) to silence β3 integrin expression in mouse NME breast cancer cells (23,24), which are reminiscent of a basal-like breast cancer cell line (24), and human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, a TNBC cell line (29). The expression of β3 integrin was elevated in both cell lines after stimulation with TGF-β for 72 h (14). Subsequent treatment of the stimulated cells with ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles resulted in the rapid loss of β3 integrin mRNA within the first 16 h following treatment (Fig. 1B). β3 integrin expression was reduced by ~75% and this downregulation was sustained for up to 7 d in NME cells treated with TGF-β (Fig. 1B and C). ECO/siβ3 treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells reduced β3 integrin expression level to that of the unstimulated cells (Fig. 1B and D). Importantly, treatment with ECO/nonspecific siRNA nanoparticles (ECO/siNS) failed to alter β3 integrin expression in both cell lines (Fig. 1B-D). Collectively, these results demonstrate the ability of ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles to induce efficient and prolonged silencing of β3 integrin expression in breast cancer cells.

ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles attenuate TGF-β-mediated EMT, invasion, and proliferation

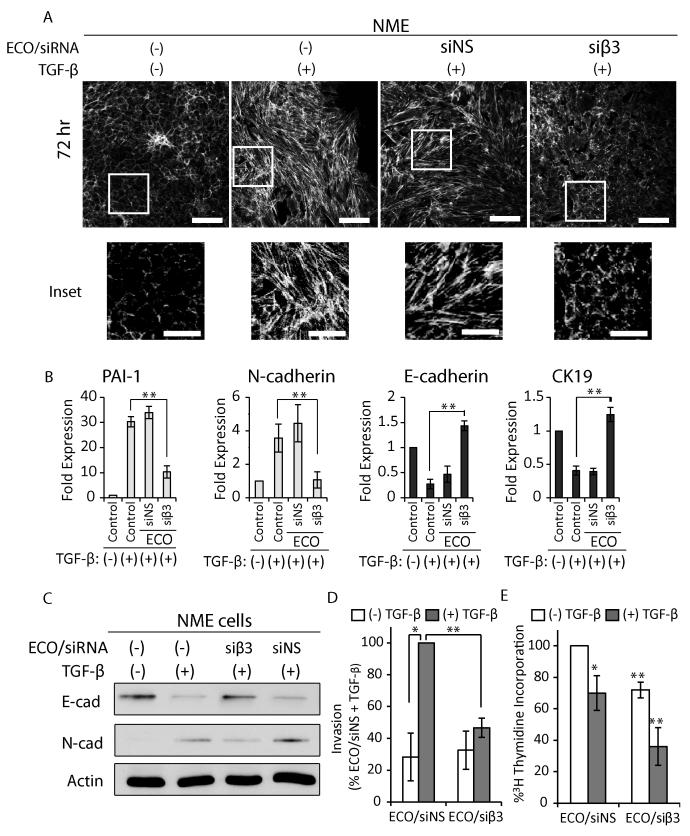

Next, we investigated the effects of ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles on EMT, invasion, and proliferation of breast cancer cells. Phalloidin staining of the actin cytoskeletal architecture (18) revealed that quiescent NME cells displayed the epithelial hallmark of densely packed and well-organized cortical actin network (18), while those stimulated with TGF-β exhibited dissolved junctional complexes and acquired an elongated morphology consistent with stress fiber formation that are characteristic of mesenchymal cells (Fig. 2A). Treatment of NME cells with ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles at the time of TGF-β stimulation inhibited dissolution of the junctional complexes and stress fiber formation, while treatment with ECO/siNS nanoparticles failed to impact TGF-β-induced morphological changes (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the phenotypic changes in post-EMT cells were accompanied by alterations in the expression of EMT-related genes(30). Silencing of β3 integrin with ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles significantly reduced TGF-β-mediated upregulation of the mesenchymal markers, N-cad and PAI-1, and inhibited TGF-β-mediated downregulation of the epithelial markers, E-cad and CK-19 (Fig. 2B and C). ECO/siNS nanoparticles did not alter the effect of TGF-β on the aforementioned EMT markers.

Figure 2.

ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles attenuated TGF-β-mediated EMT, invasion and proliferation. A, Immunofluorescence images of actin cytoskeleton visualized with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin in mouse NME cells with different treatments (scale bar, 100 μm; inset scale bar, 50 μm). B, Semi-quantitative real-time PCR analysis (n=3) of EMT markers in NME cells (**p≤0.01). C, Western blot analysis of E-cadherin and N-cadherin in NME cells. D, Invasion assay of quiescent (white bars) or TGF-β stimulated (gray bars) NME cells (n=3, *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01). E, Proliferation as measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation of either quiescent (white bars) or TGF-β stimulated (gray bars) NME cells (n=3, *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01). For all experimental groups, NME cells were pre-treated with TGF-β (5ng/mL; 72 hours) followed by ECO/siRNA nanoparticle treatment using 100nM siRNA. For panels B, D-E, data represent mean ± SE. Results for panels D-E are representative of three independent experiments.

TGF-β-mediated EMT is also associated with increased invasiveness (10,30) and cell cycle arrest (31). TGF-β-stimulated NME cells treated with ECO/siNS readily invaded reconstituted basement membrane, while ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles significantly inhibited invasion (Fig. 2D). Conversely, treatment of quiescent NME cells with ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles had no effect on basal invasiveness, an event that is uncoupled from β3 integrin expression. Previous studies demonstrate that parental NMuMG cells readily undergo proliferative arrest when stimulated with TGF-β (31). We found that the NME cells override these cytostatic effects of TGF-β (Fig. 2E), while treatment with ECO/siβ3 partially restores TGF-β-mediated cytostasis (Fig. 2E). Collectively, these findings indicate that ECO/siβ3 nanoparticle-mediated silencing of β3 integrin attenuates TGF-β-induced EMT and invasion, and partially restores TGF-β-mediated cytostasis.

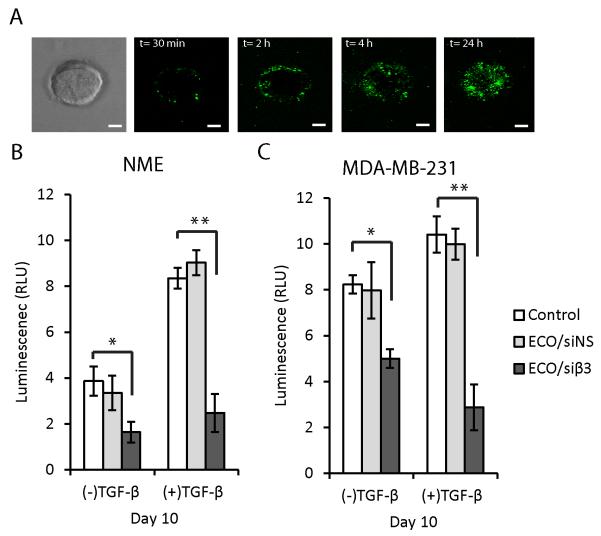

ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles attenuate outgrowth of murine and human MECs in 3D-organotypic culture

To study the effects of ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles in a physiologically relevant system, we cultured NME and MDA-MB-231 cells in 3D-organotypic cultures to recapitulate the elastic modulus of a distant metastatic site such as the pulmonary microenvironment (32). This culture method presented additional obstacles in the delivery and uptake of nanoparticles, since these organoids were compact and surrounded by a dense matrix. Using confocal microscopy, we confirmed that ECO/siRNA nanoparticles formulated with fluorescently-labeled siRNA (AF-488) readily gained access to NME organoids by first penetrating into the periphery within 30 min after treatment, and further dispersing throughout the entirety of the organoid to reach a near-uniform distribution within 24 h (Fig. 3A). The dispersion of ECO/siRNA nanoparticles into the inner cell layers of the organoids suggests that ECO/siRNA uptake by these cells may result from diffusion through intercellular spaces or through transcytosis (33). Fig. 3B and C show that NME and MDA-MB-231 organoids stimulated with TGF-β exhibited increased growth as compared to their quiescent counterparts. Treatment with ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles inhibited the growth of both quiescent and TGF-β-stimulated NME and MDA-MB-231 organoids (Fig. 3B and C) in comparison to treatment with ECO/siNS nanoparticles. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles in attenuating the 3D outgrowth of post-EMT breast cancer cells.

Figure 3.

ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles attenuated 3D organoid outgrowth. NME and MDA-MB-231 cells were grown in a compliant 3D-organotypic microenvironment and treated with ECO nanoparticles containing Alexa Fluor 488-labeled siRNA. Cellular uptake of ECO/siRNA nanoparticles monitored by fluorescence confocal microscopy (scale bar, 100 μm). A, Bright-field microscopic image of a single organoid and fluorescence confocal microscopic images of ECO/siRNA nanoparticle uptake in the organoid over the course of 24 hours. B, NME and C, MDA-MB-231 cells were grown in a compliant 3D-organotypic microenvironment for up to 10 days with or without prior TGF-β stimulation (5ng/mL) for 72 h. On day 4, 6 and 8, cells were treated with ECO/siNS or ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles at 100 nM siRNA. Organoid growth at day 10 was monitored via longitudinal bioluminescence (n=4, *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01). For panels C-D, data represent mean ± SE.

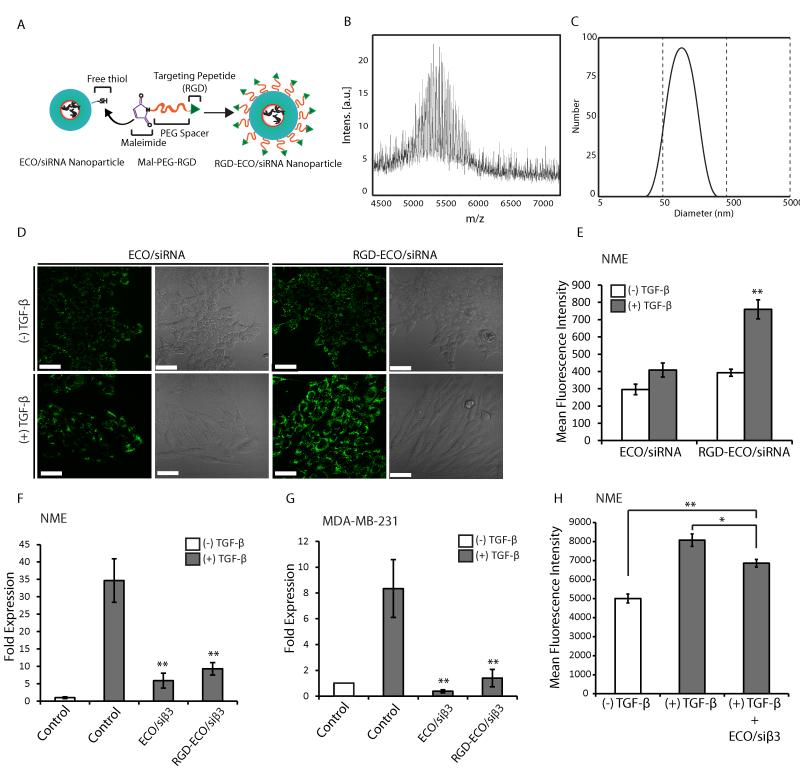

Surface modification of ECO/siRNA nanoparticles with RGD peptide promotes cellular uptake and sustains gene silencing

An essential goal of in vivo siRNA delivery is to increase siRNA localization at the disease site while minimizing its accumulation in non-target tissues (34). We modified ECO/siRNA nanoparticles with a cyclic RGD peptide, which binds to αvβ3 integrin, or a non-targeting control cyclic RAD peptide via PEG spacers (3,400 Da; refs. 22,31) (Fig. 4A and B). The size of RGD-modified ECO/siRNA nanoparticles (RGD-ECO/siRNA) was 88.3 ± 5.2 nm, as determined by dynamic light scattering (Fig. 4C). Their cellular uptake was then examined in both unstimulated and TGF-β-stimulated NME cells. TGF-β stimulation had no effect on the cellular uptake of unmodified ECO/siRNA nanoparticles, while cellular uptake of RGD-ECO/siRNA nanoparticles was robustly enhanced (Fig. 4D and E), leading to effective silencing of β3 integrin in TGF-β-treated cells (Fig. 4F and G). Since αvβ3 is a major receptor that recognizes the RGD targeting peptide, we sought to determine whether β3 integrin silencing impacts cellular uptake of RGDECO/siRNA nanoparticles. Although cellular uptake of RGD-targeted nanoparticles was diminished upon β3 integrin silencing, uptake was nonetheless elevated consistently, because of the presence of other receptors for the peptide (Fig. 4H; ref 35). Taken together, these results show that RGD-targeted ECO/siRNA nanoparticles efficiently promote cellular uptake and robust gene silencing, particularly in post-EMT and metastatic breast cancer cells.

Figure 4.

RGD modification of ECO/siRNA nanoparticles enhances uptake in post-EMT breast cancer cells. A, RGD-ECO/siRNA nanoparticles were prepared by modifying the ECO/siRNA nanoparticles with RGD-targeted PEG ligand via thiol-maleimide chemistry. B, Conjugation of RGD-PEG-maleimide to ECO was confirmed from MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The center of the bell was observed at m/z 5200 confirming the conjugation of RGD-PEG-maleimide (m/z, 4100) to ECO [m/z, 1046 (M+Na+)]. C, The size of RGD-ECO/siRNA nanoparticles was determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS). NME cells, with or without TGF-β stimulation (5ng/mL; 72 hours), were treated with ECO nanoparticles with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled siRNA at 40 nM siRNA for 4 hours. NME cells that were stimulated with TGF-β exhibited a higher cellular uptake of RGD-targeted ECO/siRNA nanoparticles compared to the non-targeted ECO/siRNA nanoparticles as confirmed by D, confocal microscopy (scale bar, 50 μm) and E, quantified by flow cytometry (n=3, **p≤0.01). Quantitative analysis of β3 integrin mRNA levels following treatment with siβ3 nanoparticles by real-time PCR (n=3, **p≤0.01) in F, NME and G, MDA-MB-231 cells revealed RGD-targeted ECO/siRNA nanoparticles maintain gene silencing. H, Cellular uptake in NME cells, both with and without TGF-β stimulation (5ng/mL; 72 hours), was quantified by flow cytometry for RGD-ECO/siRNA nanoparticles containing Alexa Fluor 488-labelled siRNA 4 hours after treatment. One group of TGF-β stimulated NME cells (TGF-β + ECO/siβ3) was treated with ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles at 100 nM siRNA for 48 hours prior to cellular uptake with the RGD-targeted nanoparticles to quantify the effect of β3 integrin silencing on targeted uptake (n=3, ±SE, *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01). For panels C-F, data represent mean ± SE.

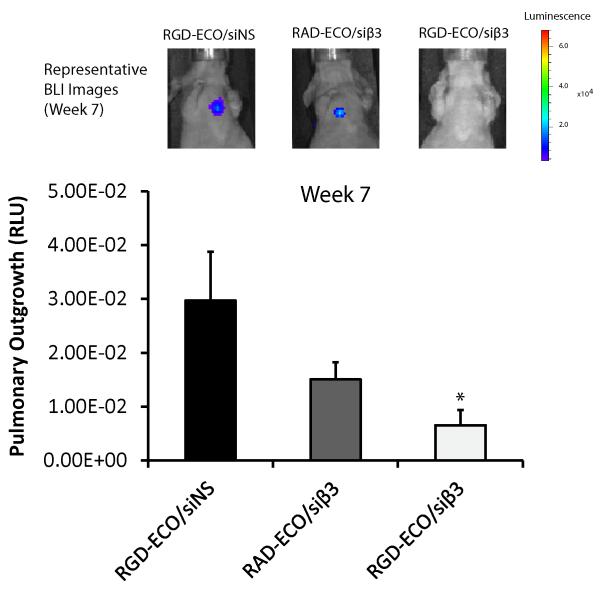

RGD-ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles inhibit pulmonary outgrowth of mouse MECs in vivo

To evaluate the effect of β3 integrin silencing on pulmonary outgrowth, we inoculated TGF-β-treated NME cells into the lateral tail vein of nude mice and subsequently monitored pulmonary outgrowth. Systemic injections of RGD-targeted ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles dramatically inhibited pulmonary outgrowth of post-EMT NME cells (Fig. 5), as compared to non-specific RADECO/siβ3 and RGD-ECO/siNS treatment groups. These results demonstrate that RGD-targeted ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles with PEG spacers can effectively inhibit pulmonary outgrowth of TGF-β-stimulated NME cells, when targeted for in vivo delivery applications.

Figure 5. Pulmonary outgrowth of NME cells treated with the ECO/siRNA treatment regimen.

TGF-β-pre-treated NME cells (1 × 106) were injected into the lateral tail vein of nude mice. Tail vein administration of the ECO/siRNA treatment regimen (siRNA dose of 1.5 mg/kg, ECO dose of 18.6 mg/kg) was conducted every 5 d, starting at day 18 after the cancer cell inoculation (n = 4, mean ± SE, *p ≤ 0.05).

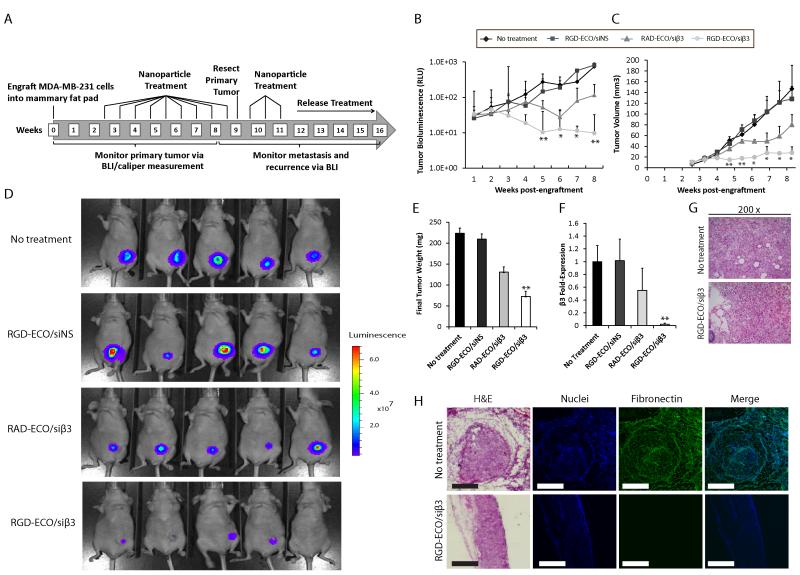

RGD-ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles effectively inhibit primary tumor growth and metastasis of malignant human MECs

To further evaluate the in vivo effect of our targeted ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles, MDA-MB-231 cells pretreated with TGF-β were engrafted into the mammary fat pad of nude mice. Mice were treated with RGD-ECO/siβ3 (1.5 mg/kg siRNA, 18.6 mg/kg ECO) every 5 days, starting at day 17 (Fig. 6A). Primary tumor burden was monitored by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) and caliper measurements. Compared to the untreated control, RGD-ECO/siNS or RAD-ECO/siβ3 treatment groups, RGD-ECO/siβ3 treated mice exhibited significantly reduced primary tumor burden (Fig. 6B-D). The primary tumors were resected at week 9 (Fig. 6A) and weighed. Fig. 6E shows that RGD-ECO/siβ3 treatment resulted in significantly reduced tumor weights as compared to the control groups. Importantly, the therapeutic efficacy of RGD-ECO/siβ3 was reflected by decreased mRNA expression of β3 integrin in the primary tumors, relative to that in the control groups (Fig. 6F). RAD-ECO/siβ3 treatment resulted in marginally reduced β3 integrin expression (Fig. 6F), which was consistent with the marginally reduced primary tumor burden, which were not statistically significant (Fig 6D and E). These data reflect partial uptake of the RAD-ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles by primary tumors as a result of passive tumor accumulation attributed to tumor vascular hyperpermeability. H&E staining of tissue sections demonstrated similar histopathological patterns in RGD-ECO/siβ3-treated and control groups, while untreated mice developed tumors that were more vascularized than RGD-ECO/siβ3-treated tumors (Fig. 6G). Further immunostaining of tissue sections indicated that RGD-ECO/siβ3-treated primary tumors exhibited decreased expression of a mesenchymal marker, fibronectin (Fig. 6H), which is associated with poor overall survival (36).

Figure 6.

RGD-targeted ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles inhibited primary tumor growth and EMT in mice after systemic administration. A, Schematic of targeted ECO/siRNA nanoparticle treatment (siRNA dose of 1.5 mg/kg, ECO dose of 18.6 mg/kg) schedule in vivo. Tumor growth was monitored at the indicated time points B, and quantified by C, BLI (data represents mean ± SE, n=5, *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01), and D, caliper measurements (data represents mean ± SE, n=5, *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01). E, Primary tumors were resected at week 9, and final tumor weights of the indicated treatment groups were obtained (data represents mean ± SE, n=5, **p≤0.01). F, Semi-quantitative real-time quantification of β3 integrin mRNA expression from resected primary tumors of the indicated groups (data represents mean ± SE, n=5, **p≤0.01). G, H&E staining at 200X of primary tumors. H, H&E, DAPI and fibronectin immunostaining of the indicated primary tumors (scale bar, 300 μm).

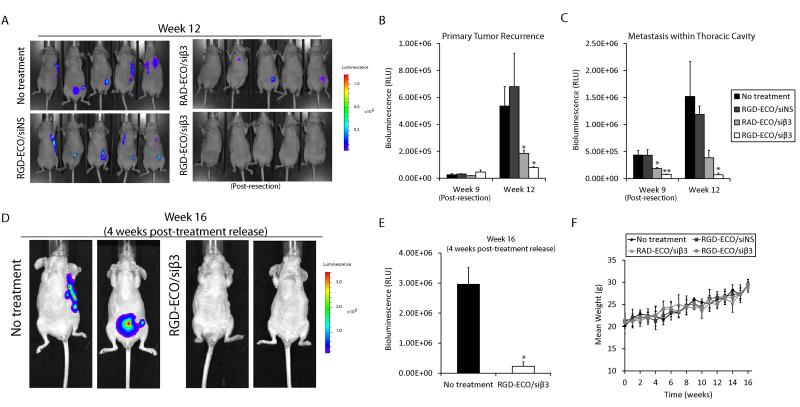

RGD-ECO/siβ3 treatment resulted in robust inhibition of tumor metastases (Fig. 7A and C) and primary tumor recurrence (Fig. 7B), as compared to control groups at week 12 post-engraftment. Primary tumor recurrence was evaluated by restricting the region of interest (ROI) of the bioluminescent image to that of the area originally occupied by the resected primary tumor. Interestingly, RAD-ECO/siβ3 treatment also mediated significant inhibition of tumor metastases and primary tumor recurrence as compared to RGD-ECO/siNS treatment, but to a lesser extent than RGD-ECO/siβ3. This decrease in the efficacy of RAD-ECO/siβ3 could be attributed to the lack of specific targeting and binding of the nanoparticles to the cancer cells. At 12 weeks post-engraftment, the RGD-ECO/siβ3 group was released from nanoparticle treatment to evaluate the lasting effects of therapeutic β3 integrin silencing on tumor recurrence and metastases in comparison with the untreated control group. At 4 weeks post-treatment release (16 weeks post-engraftment), the RGD-ECO/siβ3-treated mice remained tumor-free, while the tumor burden of untreated mice continued to increase (Fig. 7D and E). Finally, throughout the entire course of treatment, no significant difference was observed in the body weights across the different treatment groups, demonstrating the low toxicity of the intravenously administered, targeted and PEGylated ECO/siRNA nanoparticles (Fig. 7F). Collectively, these data highlight the effectiveness and safety of the systemic administration of RGD-ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles for the inhibition of TNBC tumor progression and metastases.

Figure 7.

RGD-ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles inhibited breast cancer metastasis and primary tumor recurrence. A, BLI images of mice at week 12 revealed differences in metastasis and primary tumor recurrence for the different treatment groups after primary tumor resection on week 9. B, Quantification of primary tumor recurrence (data represents mean ± SE, n=5, *p≤0.05). C, Quantification of thoracic metastasis by BLI (data represents mean ± SE, n=5, *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01). Mice were released from ECO/siRNA therapeutic regimen at week 12. D, Representative BLI of mice on week 16. E, Quantification of whole body tumors from D. (data represents mean ± SE, n=5, *p≤0.05). F, Change in the body weight of mice bearing MDA-MB-231 primary tumors across various treatment groups over the course of 16 weeks. The body weight was measured weekly and reported as mean ± S.E. (n = 5) for each group. No significant difference was observed between the various treatment groups at any time point.

Discussion

Cancer metastasis involves a cascade of events, including EMT and local invasion, intravasation, survival in circulation, extravasation, and outgrowth of disseminated cells at the secondary site. Cancer cell EMT is considered to be a critical step for the initiation of cancer metastasis. In order to alleviate metastasis, it is essential to prevent EMT and to eliminate the dissemination and outgrowth of cells that have already undergone EMT. Silencing EMT-related genes by RNAi has the potential to revolutionize current treatment standards. β3 integrin has been implicated as a powerful inducer of EMT (11,14), potentiating the oncogenic effects of TGF-β by inducing invasion and metastases of MECs. Here, we demonstrated that silencing the expression of β3 integrin with RGD-ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles prevented TGF-β-mediated EMT and inhibited TNBC metastasis.

Although functional disruption of β3 integrin has been shown to attenuate TGF-β-mediated EMT and tumor progression (11,14), the utilization of β3 integrin siRNA as a therapeutic regimen has been limited due to the lack of a clinically feasible approach. In the present study, we demonstrated ECO to be a versatile, safe, and effective siRNA delivery vehicle that forms stable RGD-targeted siRNA nanoparticles for systemic siRNA delivery, which silenced β3 integrin expression, and subsequently eliminated post-EMT cells responsible for metastases. The inhibition of TGF-β-mediated EMT with ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles was evident by the obstruction of TGF-β-mediated morphological changes, downregulation of epithelial markers, and upregulation of mesenchymal markers in vitro. Moreover, silencing β3 integrin also decreased invasiveness and reduced outgrowth of breast cancer cells in 3D-culture and in vivo. The effectiveness of RGD-targeted ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles for treating metastatic TNBC was evident by reduced primary tumor burden in tumors with diminished expression of β3 integrin. More importantly, ECO/siβ3 treatment abrogated metastases and primary tumor recurrence after treatment release.

Several unique features of ECO and ECO/siRNA nanoparticles render the delivery system effective for safe and systemic delivery of a therapeutic siRNA in treating metastatic TNBC. ECO possesses pH-sensitive amphiphilicity, which is essential to promote endo-lysosomal escape and avoid lysosomal siRNA degradation. The amino groups within ECO become protonated when exposed to the increasingly acidic environment of the endo-lysosomes, thereby increasing the cationic charge of the nanoparticles to promote endo-lysosomal membrane fusion for escape. Thiol groups of the cysteine residues are autoxidized into disulfide bridges during nanoparticle formulation, which stabilize the nanoparticles during circulation and become reduced by cytosolic glutathione, resulting in siRNA release from ECO to initiate RNAi in cytoplasm (17). The thiol groups also facilitate surface modification of ECO/siRNA nanoparticles with PEG or targeting peptides. This modification enables targeted in vivo siRNA delivery into tumor tissues and minimizes potential toxic side effects. This multi-functionality uniquely resides within a simple small molecular lipid, making ECO a versatile carrier for highly efficient cytosolic siRNA delivery. The formation of targeted ECO/siRNA nanoparticles is straightforward and reproducible, and can be readily scaled-up for clinical development.

We demonstrated that β3 integrin is a powerful therapeutic target for treating metastatic TNBC, and that RGD-ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles are an effective vehicle to systemically silence β3 integrin in post-EMT cancer cells. Specifically, RGD-ECO/siβ3 may be beneficial for TNBC patients who currently lack targeted treatments. Administering RGD-ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles in combination with chemotherapy also has the potential to resensitize drug-resistant TNBC cells to chemotherapy. Moreover, αvβ3 integrin is highly expressed in the angiogenic vasculature of many cancer types and the RGD peptide is a well-established strategy for honing the delivery of therapeutics to the tumor (37-39). These studies highlight the potential of our RGD-ECO/siβ3 regimen in targeting not only the primary tumor, but also endothelial cells in angiogenic tumor vasculature for treating breast cancer. However, β3 integrin silencing may cause potential side effects in wound-healing (10), which remain to be addressed. The effectiveness of ECO/siβ3 for treating established metastatic lesions and some types of TNBC without elevated expression of β3-integrin is not clear and needs further investigation. Previous studies suggest that established metastatic breast lesions utilize β1 integrin to sustain outgrowth (40,41), which we currently hypothesize to limit the effectiveness of our RGD-ECO/siβ3 regimen in the treatment of late stage metastatic breast cancer. Due to the versatility of our multifunctional ECO/siRNA nanoparticles, targeted nanoparticles with different targeting ligands and siRNAs, including β1 integrin siRNA, can be readily formulated to address this issue. We are currently exploring the effectiveness of dual β1 and β3 integrin targeting using our ECO/siRNA nanoparticles (14). In summary, silencing of β3 integrin expression with our targeted multifunctional ECO/siβ3 nanoparticles is a promising therapeutic strategy for the effective treatment of metastatic TNBC associated with elevated β3 integrin.

Acknowledgments

Research support was provided, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health to ZR.L. (EB00489) and W.P.S. (CA129359 and CA177069), a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to M.D.G. (DGE-0951783) and a Department of Defense Postdoctoral Fellowship to J.G.P (BC133808). We thank Dr. Amita M. Vaidya for editing and proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: Z.-R. Lu is one of the founders of Cleveland Theranostics LLC. J.G. Parvani, M.D. Gujrati, W.P. Schiemann and Z.-R. Lu have ownership interest in a patent. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by M.A. Mack.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, Stein K, Mariotto A, Smith T, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220–41. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Toole SA, Beith JM, Millar EK, West R, McLean A, Cazet A, et al. Therapeutic targets in triple negative breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66(6):530–42. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-201361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metzger-Filho O, Tutt A, de Azambuja E, Saini KS, Viale G, Loi S, et al. Dissecting the heterogeneity of triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1879–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner N, Moretti E, Siclari O, Migliaccio I, Santarpia L, D’Incalci M, et al. Targeting triple negative breast cancer: is p53 the answer? Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(5):541–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy MJ, McGowan PM, Crown J. Targeted therapy for triple-negative breast cancer: where are we? Int J Cancer. 2012;131(11):2471–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Micalizzi DS, Farabaugh SM, Ford HL. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: parallels between normal development and tumor progression. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15(2):117–34. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9178-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalluri R. EMT: when epithelial cells decide to become mesenchymal-like cells. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(6):1417–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI39675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creighton CJ, Chang JC, Rosen JM. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in tumor-initiating cells and its clinical implications in breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15(2):253–60. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor MA, Parvani JG, Schiemann WP. The pathophysiology of epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by transforming growth factor-beta in normal and malignant mammary epithelial cells. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15(2):169–90. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9181-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galliher AJ, Schiemann WP. Beta3 integrin and Src facilitate transforming growth factor-beta mediated induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(4):R42. doi: 10.1186/bcr1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galliher AJ, Schiemann WP. Src phosphorylates Tyr284 in TGF-beta type II receptor and regulates TGF-beta stimulation of p38 MAPK during breast cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67(8):3752–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galliher-Beckley AJ, Schiemann WP. Grb2 binding to Tyr284 in TbetaR-II is essential for mammary tumor growth and metastasis stimulated by TGF-beta. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(2):244–51. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parvani JG, Galliher-Beckley AJ, Schiemann BJ, Schiemann WP. Targeted inactivation of beta1 integrin induces beta3 integrin switching, which drives breast cancer metastasis by TGF-beta. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24(21):3449–59. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malamas AS, Gujrati M, Kummitha CM, Xu R, Lu ZR. Design and evaluation of new pH-sensitive amphiphilic cationic lipids for siRNA delivery. J Control Release. 2013;171(3):296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitehead KA, Dahlman JE, Langer RS, Anderson DG. Silencing or stimulation? siRNA delivery and the immune system. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2011;2:77–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gujrati M, Malamas A, Shin T, Jin E, Sun Y, Lu ZR. Multifunctional Cationic Lipid-Based Nanoparticles Facilitate Endosomal Escape and Reduction-Triggered Cytosolic siRNA Release. Mol Pharm. 2014;11(8):2734–44. doi: 10.1021/mp400787s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wendt MK, Schiemann WP. Therapeutic targeting of the focal adhesion complex prevents oncogenic TGF-beta signaling and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(5):R68. doi: 10.1186/bcr2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor MA, Davuluri G, Parvani JG, Schiemann BJ, Wendt MK, Plow EF, et al. Upregulated WAVE3 expression is essential for TGF-beta-mediated EMT and metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142(2):341–53. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2753-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balanis N, Yoshigi M, Wendt MK, Schiemann WP, Carlin CR. beta3 integrin-EGF receptor cross talk activates p190RhoGAP in mouse mammary gland epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(22):4288–301. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shastry M, Yardley DA. Updates in the treatment of basal/triple-negative breast cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25(1):40–8. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32835c1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang XL, Xu R, Wu X, Gillespie D, Jensen R, Lu ZR. Targeted systemic delivery of a therapeutic siRNA with a multifunctional carrier controls tumor proliferation in mice. Mol Pharm. 2009;6(3):738–46. doi: 10.1021/mp800192d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wendt MK, Smith JA, Schiemann WP. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition facilitates epidermal growth factor-dependent breast cancer progression. Oncogene. 2010;29(49):6485–98. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wendt MK, Taylor MA, Schiemann BJ, Sossey-Alaoui K, Schiemann WP. Fibroblast growth factor receptor splice variants are stable markers of oncogenic transforming growth factor beta1 signaling in metastatic breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(2):R24. doi: 10.1186/bcr3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor MA, Amin JD, Kirschmann DA, Schiemann WP. Lysyl oxidase contributes to mechanotransduction-mediated regulation of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in breast cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2011;13(5):406–18. doi: 10.1593/neo.101086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(3):241–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wendt MK, Taylor MA, Schiemann BJ, Schiemann WP. Downregulation of epithelial cadherin is required to initiate metastatic outgrowth of breast cancer. Molecular biology of the cell. 2011;22(14):2423–35. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-04-0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wendt MK, Schiemann BJ, Parvani JG, Lee YH, Kang Y, Schiemann WP. TGF-beta stimulates Pyk2 expression as part of an epithelial-mesenchymal transition program required for metastatic outgrowth of breast cancer. Oncogene. 2013;32(16):2005–15. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Chen X, Sanders ME, Chakravarthy AB, Shyr Y, et al. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(7):2750–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI45014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parvani JG, Taylor MA, Schiemann WP. Noncanonical TGF-beta signaling during mammary tumorigenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2011;16(2):127–46. doi: 10.1007/s10911-011-9207-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wendt MK, Smith JA, Schiemann WP. p130Cas is required for mammary tumor growth and transforming growth factor-beta-mediated metastasis through regulation of Smad2/3 activity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(49):34145–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butcher DT, Alliston T, Weaver VM. A tense situation: forcing tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(2):108–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Florence AT, Hussain N. Transcytosis of nanoparticle and dendrimer delivery systems: evolving vistas. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;50(Suppl 1):S69–89. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh YK, Park TG. siRNA delivery systems for cancer treatment. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61(10):850–62. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polyak K. Heterogeneity in breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):3786–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI60534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balanis N, Wendt MK, Schiemann BJ, Wang Z, Schiemann WP, Carlin CR. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition promotes breast cancer progression via a fibronectin-dependent STAT3 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(25):17954–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.475277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Z, Wang F, Chen X. Integrin alpha(v)beta(3)-Targeted Cancer Therapy. Drug Dev Res. 2008;69(6):329–39. doi: 10.1002/ddr.20265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gasparini G, Brooks PC, Biganzoli E, Vermeulen PB, Bonoldi E, Dirix LY, et al. Vascular integrin alpha(v)beta3: a new prognostic indicator in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4(11):2625–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin H, Varner J. Integrins: roles in cancer development and as treatment targets. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(3):561–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barkan D, El Touny LH, Michalowski AM, Smith JA, Chu I, Davis AS, et al. Metastatic growth from dormant cells induced by a col-I-enriched fibrotic environment. Cancer Res. 2010;70(14):5706–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barkan D, Kleinman H, Simmons JL, Asmussen H, Kamaraju AK, Hoenorhoff MJ, et al. Inhibition of metastatic outgrowth from single dormant tumor cells by targeting the cytoskeleton. Cancer Res. 2008;68(15):6241–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]