Abstract

Objective

As an update to other recent meta-analyses, the purpose of this study was to explore whether interleukin-10 (IL-10) polymorphisms and their haplotypes contribute to tuberculosis (TB) susceptibility.

Methods

We searched for published case-control studies examining IL-10 polymorphisms and TB in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Wanfang databases and the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to calculate the strengths of the associations.

Results

A total of 28 studies comprising 8,242 TB patients and 9,666 controls were included in the present study. There were no significant associations between the -1082G/A, -819C/T, and -592A/C polymorphisms and TB in the pooled samples. Subgroup analyses revealed that the -819T allele was associated with an increased TB risk in Asians in all genetic models (T vs. C: OR=1.17, 95% CI=1.05-1.29, P=0.003; TT vs. CC: OR=1.37, 95% CI=1.09-1.72, P=0.006; CT+TT vs. CC: OR=1.33, 95% CI=1.09-1.63, P=0.006; TT vs. CT+CC: OR=1.17, 95% CI=1.02-1.35, P=0.03) and that the -592A/C polymorphism was significantly associated with TB in Europeans under two genetic models (A vs. C: OR=0.77, 95% CI=0.60-0.98, P=0.03; AA vs. CC: OR=0.53, 95% CI=0.30-0.95, P=0.03). Furthermore, the GCC IL-10 promoter haplotype was associated with an increased risk of TB (GCC vs. others: P=1.42, 95% CI=1.02-1.97, P=0.04). Subgroup analyses based on ethnicity revealed that the GCC haplotype was associated with a higher risk of TB in Europeans, whereas the ACC haplotype was associated with a lower TB risk in both Asians and Europeans.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis suggests that the IL-10-819T/C polymorphism is associated with the risk of TB in Asians and that the IL-10-592A/C polymorphism may be a risk factor for TB in Europeans. Furthermore, these data indicate that IL-10 promoter haplotypes play a vital role in the susceptibility to or protection against the development of TB.

Introduction

TB, an infectious disease primarily caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), is a growing global public health problem. According to the World Health Organization, approximately one-third of the world’s population is infected with M. tuberculosis, though only 10% of individuals who are infected by the pathogen will develop clinical disease [1]. These data suggest that, in addition to M. tuberculosis itself, the development of TB after infection may also involve certain host factors, such as host immunity and genetics [2].

IL-10, which is expressed by activated monocytes/macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells (DCs), mast cells, B cells, and regulatory T cell subsets, is known to have macrophage-deactivating properties and undermines the Th1-driven pro-inflammatory response by down-regulating the production of several cytokines. O'Leary et al. demonstrated that in macrophages, IL-10 may prevent phagosome maturation, thus leading to M. tuberculosis persistence in humans [3]. Several studies have also reported high levels of IL-10 production in TB patients [4,5]. Furthermore, in mouse models, over-expression of IL-10 may affect the recurrence of latent TB but shows little effect on susceptibility to primary infection [6]. These results indicate that the IL-10 gene and its gene product, IL-10, play a critical role in susceptibility to and pathogenesis of TB.

The IL-10 gene maps to chromosome 1q31-32. The IL-10 promoter is highly polymorphic, and three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at positions -1082, -819, and -592 within the promoter region have been shown to correlate with IL-10 production [7]. Meanwhile, these polymorphisms exhibit strong linkage disequilibrium. Previous in vitro studies showed that the GCC haplotype of peripheral blood mononuclear cells was related to abundant IL-10 production, whereas the ATA haplotype was correlated with low levels of IL-10 production [7–11].

To date, many genetic epidemiology studies have assessed the association between IL-10 gene polymorphisms and the risk of TB in different populations [2,12–38]. However, the results from these studies were often inconsistent and inconclusive. This inconsistency may derive from a number of issues, including false-positive errors, lack of power, and minor impacts of IL-10 gene polymorphisms on TB susceptibility [39]. A meta-analysis is defined as research that analyzes previous research. Hence, results from previously published studies are gathered and statistically analyzed [40]. The purpose of the present study was to identify patterns among variant results, to find the sources of any inconsistencies among those results, and to eliminate the effects of random errors that are responsible for false-positive or false-negative interactions. Although there are already three published meta-analyses on these polymorphisms [41,42,43], confusing results remain unresolved. Furthermore, two of the previous studies failed to test the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Liang B. et al. considered the HWE but still included those studies that were not consistent with the HWE [43]. Deviation from the HWE among the controls implies either a potential bias during control selection or genotyping errors. Moreover, Liang B. et al. missed four studies [29, 33–34, 36] and also incorporated repeated articles into their meta-analysis, such as Ansari A. et al. (2009) and Ansari A. et al. (2011) and Selvaraj P. et al. (2008) and Prabhu Anand S. et al. (2007). Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis of all eligible studies to derive a more precise estimation of the associations between IL-10 polymorphisms and TB risk.

Methods

Publication search

An elaborate search was conducted for studies that examined the association between IL-10 polymorphisms and TB [40]. Two independent reviewers (Gao and Chen) searched PUBMED, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Wanfang databases and the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) to identify available studies that were published by August 2014 [40]. The heading (MeSH) terms and/or text words used were as follows: ‘tuberculosis or Mycobacterium tuberculosis’ in combination with ‘interleukin 10 or interleukin-10 or IL-10 or IL 10’ and ‘polymorphism or variant or genetic or SNP’. We also perused the reference lists of all retrieved articles and relevant reviews. If the full text article could not be obtained from the databases, we tried to contact the authors. There were no restrictions placed on language, race, ethnicity or geographic area [43].

Study selection and data extraction

Studies were included in this meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) studies that evaluated IL-10 gene polymorphisms and TB risk; (2) case-control studies; (3) studies that provided sufficient data to calculate an OR and a 95% CI. Studies were excluded if they (1) contained overlapping data; (2) were based on families; (3) did not provide the numbers of null and wild-type genotypes or alleles; (4) were editorials, reviews, or abstracts; or (5) were not consistent with HWE.

Data were extracted from original studies independently by two reviewers (Gao and Chen). Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved either by reaching a consensus or by a third reviewer (Yao). The following information was collected from each study: the name of the first author, the year of publication, the originating country, ethnicity, types of TB infection and controls, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, the number of cases and controls, and genotype and allele frequency information. We verified the accuracy of the data by comparing the collection forms from each investigator.

Statistical analysis

When data from at least 5 similar studies were available, meta-analysis was performed. The summary ORs and 95% CIs were used to measure the strength of the associations between IL-10 polymorphisms and TB susceptibility [39]. The statistical significance of the summary ORs was evaluated using the Z test. For each SNP, we established four genetic models to evaluate their association with TB risk: (1) allelic contrast; (2) variant homozygote genotype vs. wild-type homozygote genotype; (3) dominant model: variant homozygote combined with a heterozygote genotype versus wild-type homozygote genotype, and (4) recessive model: variant homozygote genotype versus heterozygote and wild-type homozygote genotypes.

The heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the chi-square-based Cochrane Q-test, which was considered to be significant when P<0.10 [44]. The fixed-effect model shows that the similar impact of genetic factors on TB susceptibility among variant studies are purely accidental, whereas the random-effect model indicates that dramatic diversity in assessment exists due to both intra-study sampling errors and inter-study variances [40, 45]. The fixed-effect model was chosen when the P value from the chi-square test was greater than 0.10; otherwise, the random-effect model was used [46]. To explore the source of the heterogeneity and to evaluate ethnicity-specific effects, subgroup analyses performed for IL-10 polymorphisms were investigated in a sufficient number of studies. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots, in which the standard error of the log (OR) of each study was plotted against the log (OR). Funnel plot asymmetry was assessed using Egger’s linear regression test [47]. Departure from HWE in the control group was assessed by the chi-square test, and a P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

All statistical tests were performed using Review manager 5.2 (Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark) and STATA 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) software. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

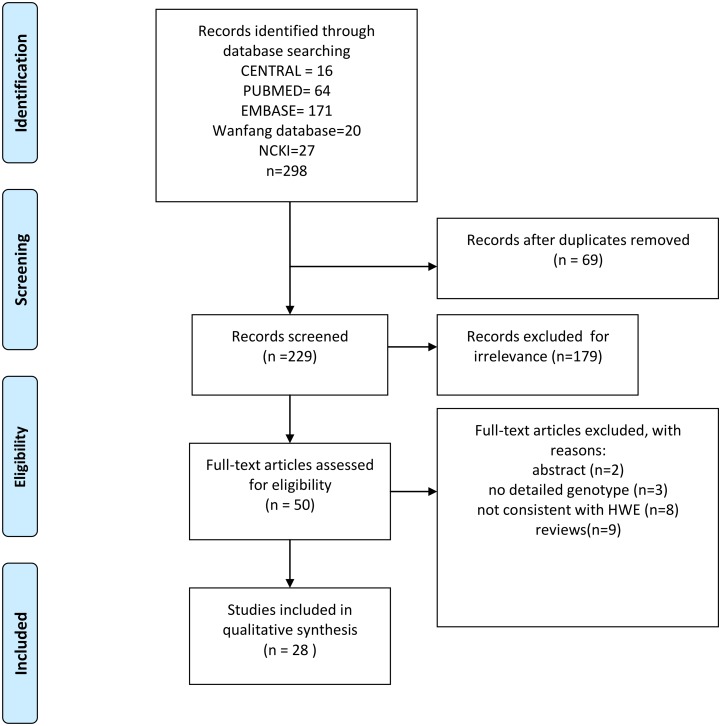

The selection process of this literature review is summarized in the flow diagram (Fig 1). A total of 28 eligible articles fully met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into this meta-analysis [2,12–38]. Of these studies, five were performed in Europeans, five in Africans, three in Americans and 15 in Asians. Table 1 shows the characteristics of these studies, and Table 2 provides the detailed genotype frequencies and the HWE assessment results.

Fig 1. Flow chart depicting the study selection process.

Table 1. Characteristics of the case-control studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study [Ref] | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Type of infection | Type of controls | Cases(n) | Controls(n) | HIV status | SNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bellamy [12] | 1998 | Gambia | African | Pulmonary TB | male donors | 401 | 408 | Negative | -1082G/A,-819C/T,-592C/A |

| Lopez-Maderuelo[13] | 2003 | Spain | European | Pulmonary TB | healthy tuberculin-negative volunteers | 113 | 100 | Negative | -1082G/A |

| Fitness [14] | 2004 | Malawi | African | TB | individually matched controls | 514 | 913 | Positive in 50% of cases and negative in control | -1082G/A,-819C/T |

| Shin [15] | 2005 | Korea | Asian | Pulmonary TB | healthy controls | 459 | 871 | Negative | -1082G/A,-819C/T,-592C/A,Haplotype |

| Tso [2] | 2005 | China | Asian | Pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB | healthy donors | 385 | 471 | Negative | Haplotype |

| Amirzargar [16] | 2006 | Iran | Asian | Pulmonary TB | healthy donors | 41 | 123 | NA | -819C/T,-592C/A |

| Oral [16] | 2006 | Turkey | European | Pulmonary, or pleural, other extrapulmonary TB | healthy donors | 81 | 50 | NA | -1082G/A,-819C/T,-592C/A,Haplotype |

| Ma [19] | 2007 | China | Asian | Pulmonary TB | healthy controls | 40 | 40 | NA | -1082G/A |

| Oh [18] | 2007 | Korea | Asian | Pulmonary TB | healthy adults | 145 | 117 | Negative | -1082G/A |

| Ates [20] | 2008 | Turkey | European | Pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB | healthy individuals | 128 | 80 | NA | -1082G/A,-819C/T,-592C/A,Haplotype |

| Selvaraj [21] | 2008 | India | Asian | Pulmonary TB | healthy subjects | 166 | 188 | Negative | -1082G/A,-819C/T |

| Wu [22] | 2008 | China | Asian | Pulmonary TB | miners with no TB | 61 | 122 | NA | -1082G/A,-819C/T,-592C/A,Haplotype |

| Moller [23] | 2009 | SouthAfrica | African | TB | healthy individuals with no TB | 432 | 482 | Negative | -1082G/A,-819C/T,-592C/A,Haplotype |

| Thye [24] | 2009 | Ghana | African | Pulmonary TB | cases with no TB contact | 2010 | 2346 | Negative | -1082G/A,-819C/T,-592C/A |

| Trajkov [25] | 2009 | Macedonia | European | TB | healthy individuals | 75 | 301 | NA | -819C/T,-592C/A |

| Taype [26] | 2010 | Peru | American | Pulmonary, or pleural, miliary other extrapulmonary TB | healthy control | 626 | 513 | NA | -1082G/A,-592C/A |

| Yang [27] | 2010 | China | Asian | Pulmonary TB | healthy subjects | 200 | 200 | NA | -1082G/A |

| Akgunes [28] | 2011 | Turkey | European | Pulmonary TB | healthy donors | 30 | 30 | NA | -1082G/A,-819C/T,-592C/A |

| Ben-Selma [29] | 2011 | Tunisia | African | Pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB | healthy donors | 131 | 95 | Negative | -819C/T,-592C/A |

| Liang L [30] | 2011 | China | Asian | Pulmonary TB and TB pleurisy | no history of TB or pleural disease | 235 | 78 | Negative | -1082G/A,-819C/T,-592C/A,Haplotype |

| Ma Hui [32] | 2012 | China | Asian | Pulmonary TB | no TB contacts | 109 | 314 | NA | -1082G/A |

| Ma MJ [33] | 2012 | China | Asian | Pulmonary TB | no TB controls | 923 | 1033 | Negative | -1082G/A,-819C/T,-592C/A |

| Mei [34] | 2012 | China | Asian | Pulmonary TB | healthy donors | 169 | 156 | NA | -592C/A |

| Xin DS [35] | 2012 | China | Asian | Pulmonary TB | no TB history patients and healthy subjects | 308 | 310 | Negative | -1082G/A |

| Ramaseri [31] | 2012 | India | Asian | Pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB | healthy volunteers | 224 | 107 | Positive in 47% of cases and negative in control | -1082G/A,-819C/T |

| Garcia [36] | 2013 | Mexico | American | Pulmonary TB | donors and healthcare workers | 98 | 60 | Negative | -1082G/A |

| Meenakshi [37] | 2013 | India | Asian | TB | healthy subjects | 100 | 100 | NA | -1082G/A |

| Hutz MH [38] | 2014 | Paraguay | American | TB | healthy individuals with no TB | 38 | 58 | NA | -819C/T,-592C/A |

TB = Tuberculosis, NA = data not available

Table 2. Distribution of IL-10 genotypes in patients and controls.

| Studies | TB | Control | HWE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 12 | 22 | 11 | 12 | 22 | P value | |

| -1082G/A | |||||||

| Akgunes [28] | 6 | 9 | 15 | 0 | 13 | 17 | 0.130 |

| Ates [20] | 26 | 65 | 37 | 6 | 32 | 42 | 0.978 |

| Bellamy [12] | 51 | 185 | 165 | 45 | 184 | 179 | 0.824 |

| Fitness [14] | 40 | 143 | 142 | 87 | 251 | 203 | 0.524 |

| Garcia [36] | 60 | 29 | 9 | 31 | 25 | 4 | 0.768 |

| Liang L [30] | 0 | 28 | 207 | 0 | 9 | 69 | 0.589 |

| Lopez-Maderuelo [13] | 33 | 47 | 33 | 29 | 50 | 21 | 0.949 |

| Ma Hui [32] | 29 | 35 | 45 | 32 | 130 | 152 | 0.591 |

| Ma MJ [33] | 14 | 165 | 744 | 7 | 183 | 843 | 0.388 |

| Ma ZM [19] | 2 | 16 | 22 | 1 | 6 | 33 | 0.292 |

| Meenakshi [37] | 4 | 81 | 15 | 16 | 59 | 25 | 0.058 |

| Moller [23] | 39 | 199 | 194 | 53 | 202 | 227 | 0.426 |

| Oh [18] | 4 | 43 | 98 | 19 | 53 | 45 | 0.612 |

| Oral [17] | 10 | 41 | 30 | 5 | 13 | 32 | 0.060 |

| Ramaseri [31] | 12 | 62 | 136 | 2 | 43 | 57 | 0.057 |

| Selvaraj [21] | 5 | 42 | 102 | 6 | 69 | 108 | 0.204 |

| Shin [15] | 2 | 53 | 394 | 9 | 124 | 718 | 0.168 |

| Taype [26] | 22 | 187 | 414 | 10 | 153 | 347 | 0.142 |

| Thye [24] | 117 | 630 | 794 | 160 | 783 | 1025 | 0.542 |

| Wu [22] | 1 | 12 | 48 | 0 | 18 | 104 | 0.379 |

| Xin DS [35] | 248 | 55 | 5 | 249 | 60 | 1 | 0.185 |

| Yang [27] | 3 | 26 | 169 | 1 | 44 | 155 | 0.253 |

| -819C/T | |||||||

| Akgunes [28] | 19 | 10 | 1 | 11 | 13 | 6 | 0.553 |

| Amirzargar [16] | 19 | 20 | 2 | 62 | 52 | 9 | 0.671 |

| Ates [20] | 63 | 58 | 7 | 36 | 36 | 8 | 0.819 |

| Bellamy [12] | 120 | 192 | 89 | 114 | 206 | 88 | 0.779 |

| Ben-Selma [29] | 55 | 65 | 11 | 43 | 42 | 10 | 0.957 |

| Fitness [14] | 178 | 220 | 60 | 287 | 303 | 108 | 0.062 |

| Liang L [30] | 22 | 90 | 123 | 12 | 31 | 35 | 0.253 |

| Ma MJ [33] | 58 | 256 | 229 | 61 | 253 | 230 | 0.491 |

| Moller [23] | 207 | 186 | 39 | 201 | 229 | 52 | 0.267 |

| Oral [17] | 48 | 23 | 10 | 24 | 19 | 7 | 0.320 |

| Ramaseri [31] | 39 | 117 | 62 | 28 | 55 | 24 | 0.760 |

| Selvaraj [21] | 24 | 86 | 45 | 45 | 82 | 56 | 0.174 |

| Shin [15] | 39 | 173 | 238 | 91 | 384 | 376 | 0.631 |

| Thye [24] | 514 | 763 | 267 | 665 | 942 | 365 | 0.329 |

| Trajkov [25] | 35 | 35 | 5 | 155 | 125 | 19 | 0.348 |

| Wu [22] | 3 | 34 | 24 | 10 | 62 | 50 | 0.125 |

| Hutz MH [38] | 0 | 6 | 32 | 0 | 7 | 51 | 0.625 |

| -592A/C | |||||||

| Akgunes [28] | 1 | 10 | 19 | 6 | 14 | 10 | 0.785 |

| Amirzargar [16] | 2 | 20 | 18 | 9 | 52 | 62 | 0.671 |

| Ates [20] | 7 | 58 | 63 | 8 | 36 | 36 | 0.819 |

| Bellamy [12] | 89 | 192 | 120 | 88 | 206 | 114 | 0.779 |

| Ben-Selma [29] | 12 | 63 | 56 | 10 | 42 | 43 | 0.957 |

| Liang L [30] | 123 | 90 | 22 | 35 | 31 | 12 | 0.253 |

| Ma MJ [33] | 370 | 432 | 121 | 440 | 476 | 117 | 0.491 |

| Mei [34] | 56 | 81 | 32 | 26 | 79 | 51 | 0.622 |

| Moller [23] | 39 | 186 | 207 | 51 | 230 | 201 | 0.213 |

| Oral [17] | 10 | 23 | 48 | 7 | 19 | 24 | 0.320 |

| Shin [15] | 238 | 173 | 39 | 376 | 384 | 91 | 0.631 |

| Taype [26] | 117 | 218 | 264 | 105 | 230 | 178 | 0.055 |

| Thye [24] | 172 | 532 | 321 | 269 | 696 | 480 | 0.551 |

| Trajkov [25] | 5 | 31 | 39 | 28 | 117 | 154 | 0.403 |

| Wu [22] | 24 | 34 | 3 | 50 | 62 | 10 | 0.125 |

| Hutz MH [38] | 32 | 6 | 0 | 51 | 7 | 0 | 0.625 |

TB = Tuberculosis; HWE = Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Twenty-two of the 28 articles studied the -1082G/A IL-10 polymorphism, 17 studied the -819C/T polymorphism, 16 studied the -592A/C polymorphism, and 6 studied IL-10 promoter haplotypes.

The IL-10-1082G/A polymorphism is not associated with TB susceptibility

The associations between the -1082G/A polymorphism and TB are shown in Table 3. A total of 22 studies containing 6,699 TB patients and 7,679 controls were included in this meta-analysis. The results showed that the -1082G/A polymorphism was not associated with TB susceptibility under any genetic model. In addition, stratification by ethnicity revealed no association between the -1082G/A polymorphism and TB.

Table 3. Meta-analysis of the association between the IL-10–1082 G/A polymorphism and TB.

| A vs. G | AA vs. GG | AA+AG vs. GG | AA vs. AG+GG | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | No. | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet |

| Overall | 22 | 0.97(0.85–1.11) | 0.67 | <0.0001 | 0.88(0.63–1.24) | 0.46 | <0.0001 | 0.87(0.65–1.15) | 0.32 | <0.0001 | 1.00(0.84–1.19) | 1.00 | <0.0001 |

| Subgroup by ethnicity | |||||||||||||

| Asian | 12 | 1.07(0.82–1.38) | 0.63 | <0.0001 | 1.01(0.44–2.34) | 0.98 | <0.0001 | 0.93(0.48–1.82) | 0.83 | <0.0001 | 1.12(0.82–1.52) | 0.48 | <0.0001 |

| European | 4 | 0.62(0.36–1.07) | 0.08 | 0.004 | 0.42(0.13–1.37) | 0.15 | 0.008 | 0.55(0.24–1.26) | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.61(0.28–1.34) | 0.22 | 0.003 |

| African | 4 | 1.01(0.91–1.11) | 0.92 | 0.11 | 1.10(0.92–1.32) | 0.30 | 0.26 | 1.11(0.93–1.32) | 0.24 | 0.42 | 0.99(0.90–1.10) | 0.88 | 0.23 |

TB = Tuberculosis; PEff = P value of pooled effect; PHet = P value of heterogeneity test.

Association between the IL-10-819C/T polymorphism and TB susceptibility

The survey results regarding the associations between the -819C/T polymorphism and TB are shown in Table 4. Our meta-analysis of the 17 case-control studies (5,024 TB patients and 6,180 controls) revealed that the -819C/T polymorphism was not associated with TB susceptibility under any genetic model.

Table 4. Meta-analysis of the association between the IL-10 -819C/T polymorphism and TB.

| T vs. C | TT vs. CC | CT+TT vs. CC | TT vs. CT+CC | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | No. | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet |

| Overall | 17 | 1.03(0.94–1.12) | 0.57 | 0.04 | 1.01(0.89–1.14) | 0.90 | 0.16 | 1.05(0.92–1.19) | 0.46 | 0.09 | 1.01(0.92–1.11) | 0.83 | 0.21 |

| Subgroup by ethnicity | |||||||||||||

| Asian | 7 | 1.17(1.05–1.29) | 0.003 | 0.49 | 1.37(1.09–1.72) | 0.006 | 0.67 | 1.33(1.09–1.63) | 0.006 | 0.70 | 1.17(1.02–1.35) | 0.03 | 0.32 |

| European | 4 | 0.77(0.52–1.15) | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.61(0.34–1.11) | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.85(0.62–1.16) | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.66(0.37–1.17) | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| African | 5 | 0.97(0.90–1.04) | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.91(0.79–1.06) | 0.22 | 0.89 | 0.98(0.89–1.09) | 0.74 | 0.32 | 0.91(0.80–1.04) | 0.16 | 0.87 |

TB = Tuberculosis; PEff = P value of pooled effect; PHet = P value of heterogeneity test.

Subgroup analysis by ethnicity revealed that the -819T allele was associated with increased TB risk in Asians under all genetic models (T vs. C: OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.05–1.29, P = 0.003; TT vs. CC: OR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.09–1.72, P = 0.006; CT+TT vs. CC: OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.09–1.63, P = 0.006; TT vs. CT+CC: OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.02–1.35, P = 0.03). However, no association was found in Europeans or Africans under any genetic model.

Association of the IL-10-592A/C polymorphism with TB susceptibility

The results of our meta-analysis of the association between the -592A/C polymorphism and TB are shown in Table 5. A total of 16 case-control studies that examined the relationship between the -592A/C polymorphism and TB risk were included in this meta-analysis. The total number of cases and controls were 4,818 and 5,823, respectively. Meta-analysis revealed no remarkable association between the -592A/C polymorphism and TB in the selected samples.

Table 5. Meta-analysis of the association between the IL-10 -592A/C polymorphism and TB.

| Population | A vs. C | AA vs. CC | AA vs. AC+CC | AA+AC vs. CC | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | |

| Overall | 16 | 0.99(0.87–1.12) | 0.84 | <0.0001 | 0.99(0.79–1.25) | 0.96 | 0.002 | 1.02(0.86–1.21) | 0.79 | 0.006 | 1.02(0.86–1.20) | 0.84 | 0.009 |

| Subgroup by ethnicity | |||||||||||||

| Asian | 6 | 1.22(0.96–1.55) | 0.11 | 0.0004 | 1.50(0.89–2.53) | 0.13 | 0.001 | 1.26(0.91–1.74) | 0.17 | 0.002 | 1.32(0.94–1.85) | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| European | 4 | 0.77(0.60–0.98) | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.53(0.30–0.95) | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.59(0.33–1.03) | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.77(0.56–1.05) | 0.10 | 0.21 |

| African | 4 | 0.96(0.88–1.04) | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.92(0.77–1.10) | 0.36 | 0.81 | 0.91(0.77–1.07) | 0.25 | 0.84 | 0.98(0.86–1.11) | 0.73 | 0.18 |

TB = Tuberculosis; PEff = P value of pooled effect; PHet = P value of heterogeneity test.

However, after stratification by different ethnicities, a significant association was found in Europeans using two genetic models (A vs. C: OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.60–0.98, P = 0.03; AA vs. CC: OR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.30–0.95, P = 0.03); this association was not observed in Asians or Africans under any genetic model.

IL-10 promoter haplotype and TB

Three SNPs in the promoter region (-1082G/A, -819C/T, -592A/C) were in complete linkage disequilibrium, and three haplotypes exist (GCC, ACC, and ATA). Six of the eligible case-control studies analyzed the relationship between the IL-10 promoter haplotype and the risk of TB (Table 6). The results of pooling all studies demonstrated that the GCC haplotype was associated with an increased risk of TB (GCC vs. others: P = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.02–1.97, P = 0.04), but no association was found between the ACC and ATA haplotypes and TB risk. Furthermore, subgroup analyses based on ethnicity showed that the GCC haplotype was associated with an increased TB risk in Europeans, whereas the ACC haplotype was associated with a lower TB risk in both Asians and Europeans (Table 6).

Table 6. Meta-analysis of the association between IL-10 promoter haplotype (-1082G/A, 819C/T, 592A/C) and TB.

| Population | GCC vs. others | ACC vs. others | ATA vs. others | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | n | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | n | OR (95% CI) | P Eff | PHet | |

| Overall | 6 | 1.42(1.02–1.97) | 0.04 | 0.009 | 6 | 0.85(0.68–1.05) | 0.14 | 0.02 | 5 | 0.90(0.78–1.04) | 0.14 | 0.74 |

| Subgroup by ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Asian | 3 | 1.30(0.93–1.82) | 0.12 | 0.70 | 2 | 0.84(0.72–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.78 | 2 | 1.04(0.79–1.38) | 0.76 | 0.87 |

| European | 2 | 2.14(1.53–3.01) | <0.0001 | 0.80 | 2 | 0.60(0.43–0.83) | 0.002 | 0.39 | 2 | 0.78(0.56–1.09) | 0.15 | 0.77 |

TB = Tuberculosis; PEff = P value of pooled effect; PHet = P value of heterogeneity test.

Heterogeneity and publication bias

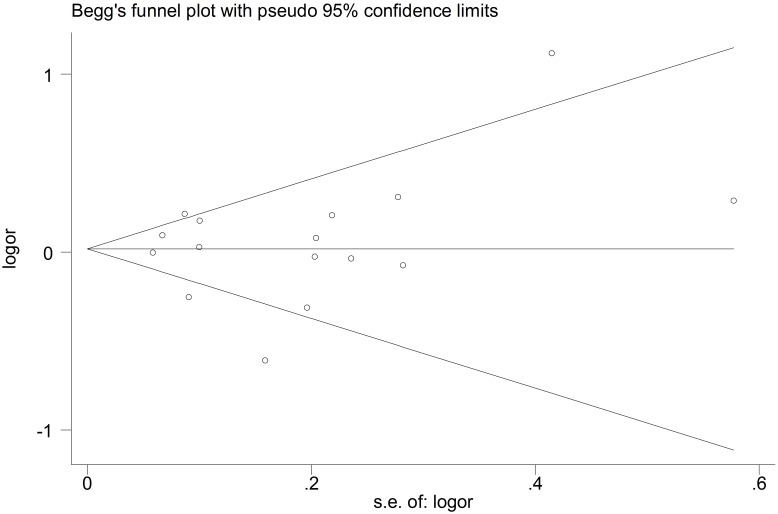

Some intra-study heterogeneity was observed during the meta-analyses, but no evidence suggested heterogeneity between the significant associations, except for the GCC haplotype as a whole. This heterogeneity was eliminated after stratification by ethnicity. The funnel plots for these polymorphisms in all compared models were symmetrical (Fig 2 shows the funnel plot for -592A/C in the allele model). The results of the Egger’s test did not suggest obvious publication bias for the -819C/T variant (P = 0.711 for T vs. C, P = 0.949 for TT vs. CC, P = 0.533 for CT+TT vs. CC, P = 0.173 for TT vs. CT+CC). Similarly, no publication bias was detected for the associations between the -1082G/A and -592A/C polymorphisms and TB.

Fig 2. Funnel plot for -592A/C in the allele model.

Discussion

It is currently believed that host genetic factors are of vital importance in the pathogenesis of TB, as host genetic factors affect the expression levels of cytokines and chemokines that are known to participate in host immunity [48]. As a powerful Th2-regulatory cytokine, IL-10 plays an essential role during the latent stage of TB infection. The long arm of chromosome 1, where the IL-10 gene is situated, contains known polymorphisms within the IL-10 promoter region, including -1082G/A, -819T/C, and -592A/C [43]. Furthermore, IL-10 is reportedly associated with TB in different ethnic backgrounds [49].

The meta-analysis performed by Zhang J. et al. reported that the -1082G/A polymorphism correlated significantly with a downside risk of TB in Europeans, whereas the IL-10 -819T/C and -592A/C polymorphisms were unrelated to TB susceptibility [41]. Similarly, another meta-analysis by Liang B. et al. confirmed that the risk for TB was independent of the -1082G/A, -819T/C, and -592A/C genotypes in the gross population but showed that the risk was dramatically reduced in the -1082G/A genotype in Europeans and Americans and was significantly associated with the -819T/C polymorphism in Asians [43].

However, in our meta-analysis, no association was revealed between the IL-10-1082G/A, -819T/C and -592A/C polymorphisms and TB susceptibility from 22 studies with 6,699 TB patients and 7,679 controls, 17 studies with 5,024 TB patients and 6,180 controls, and 16 studies with 4,818 cases and 5,823 controls, respectively. According to our subgroup analyses by ethnicity, no association was revealed between the -1082G/A polymorphism and TB. Additionally, the -819T allele was found to be associated with an increased risk of TB in Asians under all genetic models, whereas two genetic models (A vs. C; AA vs. CC) of the association between the -592A/C polymorphism and TB showed significant associations in Europeans. Several reasons may explain why our results differ from those of Zhang J. et al. and Liang B. et al. First, we only incorporated studies that were consistent with HWE. Second, our work was an update to the work of other groups, which allowed for the inclusion of some new studies. As a result, our conclusions may be more scientific. Taken together, our results suggest that ethnic differences may play an important role in environmental and genetic factors.

We also analyzed the association between IL-10 promoter haplotypes and TB risk. In our meta-analysis of 6 studies, only the GCC haplotype was associated with an increased TB risk. Moreover, subgroup analyses based on ethnicity showed that the GCC haplotype was associated with an increased TB risk in Europeans, whereas the ACC haplotype was associated with a lower TB risk in both Asians and Europeans, suggesting that ethnic differences may play a role in the association between IL-10 promoter haplotypes and TB risk.

As an indispensable tool, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) are being used more and more for the identification of common variants that are associated with a variety of diseases. To date, many GWASs have successfully identified TB susceptibility genes [50–58]. These genes include the interferon-gamma gene (IFNG), the vitamin D receptor gene (VDR), and the interleukin-12 p40 subunit gene (IL12B), among others [52, 57]. However, these studies provided no direct evidence to prove an association between TB and the IL-10 gene. Furthermore, GWASs of TB are ongoing, which indicates that TB has not been adequately studied by modern genomic technologies [59]. Many of the associated genes have not yet been studied. With an increased number of GWASs studying TB, more related genes will be found, and IL-10 is only one gene. Therefore, with respect to genome-wide associations and TB, much work remains to be done.

Two of the selected studies in our meta-analysis considered the impact of HIV status on susceptibility to TB [14, 31]. However, many researchers have focused on this issue. Their studies have found that, compared to HIV-negative controls, HIV-positive patients showed greater susceptibility to TB [60]. Especially in sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest HIV morbidity worldwide, HIV-positive persons showed a 20-fold increased risk over HIV-negative individuals of developing TB [61]. An increasing number of studies have begun to investigate the mechanism of how HIV infection influences susceptibility to TB. It was reported that antigens such as HLA-A31 and HLA-B41, chemokine receptors such as CCR5, and the -1082G allele of IL-10 were involved in TB susceptibility [31, 62–63]. However, the exact mechanism remains unclear, and additional studies are needed to clarify this issue.

Although some intra-study heterogeneity was detected for these polymorphisms during the meta-analyses, no evidence of heterogeneity was found for the significant associations. After subgroup analyses by ethnicity, the heterogeneity disappeared. This suggests that ethnicity may be the main source of heterogeneity. Furthermore, we generated funnel plots and carried out Egger’s tests to evaluate the existence of publication bias; no publication bias was observed in our study.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, additional studies are needed to complete a comprehensive analysis, especially for the IL-10 promoter haplotype [64]. Furthermore, after stratification by ethnicity, there were only a small number of studies in the European subgroup, which may reduce the strength of our conclusions. Second, different diagnostic criteria of TB and controls across studies may affect the comparability of the studies or lead to the misclassification of cases. The studies that were selected for this meta-analysis did not have unified diagnostic criteria, which may result in misclassification bias [59]. Third, the evaluation of our analysis is unadjusted. However, the accuracy of our evaluation with respect to the effects of gene-gene and gene-environment associations in TB has been compromised due to the limited amount of original data from the qualified studies [64].

In conclusion, this meta-analysis suggested that the IL-10-819T/C polymorphism was associated with TB risk in Asians and that the IL-10-592A/C polymorphism may be a risk factor for TB in Europeans. IL-10 promoter haplotypes play a vital role in the susceptibility to or protection against the development of TB. To further establish these associations, future studies with larger sample sizes and multi-ethnic sample groups are required.

Supporting Information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This research is funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81170038&81300009), http://www.nsfc.gov.cn/, and by a grant from the Natural Science Foundation for the Youth of Zhejiang Province, China (Q13H010001), http://www.nsfc.gov.cn/. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Bloom BR, Small PM (1998) The evolving relation between humans and mycobacterium tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 338: 677–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tso HW, Lp WK, Chong WP, Tam CM, Chiang AK, Lau YL (2005) Association of interferon gamma and interleukin 10 genes with tuberculosis in Hong Kong Chinese. Genes Immun 6: 358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Leary S, O'Sullivan MP, Keane J (2011) IL-10 blocks phagosome maturation in mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected human macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 45: 172–180. 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0319OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barnes PF, Lu S, Abrams JS, Wang E, Yamamura M, Modlin RL (1993) Cytokine production at the site of disease in human tuberculosis. Infect Immun 61: 3482–3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verbon A, Juffermans N, Van Deventer SJ, Speelman P, Van Deutekom H, Van Der Poll T (1999) Serum concentrations of cytokines in patients with active tuberculosis (TB) and after treatment. Clin Exp Immunol 115: 110–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Turner J, Gonzalez-Juarrero M, Ellis DL, Basaraba RJ, Kipnis A, Orme IM, et al. (2002) In vivo IL-10 production reactivates chronic pulmonary tuberculosis in C57BL/6 mice. J Immunol 169: 6343–6351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lyer SS, Cheng G (2012) Role of interleukin 10 transcriptional regulation in inflammation and autoimmune disease. Crit Rev Immunol 32: 23–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoffmann SC, Stanley EM, Darrin CE, Craighead N, DiMercurio BS, Koziol DE, et al. (2001) Association of cytokine polymorphic inheritance and in vitro cytokine production in anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes. Transplantation 72: 1444–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lyon H, Lange C, Lake S, Silverman EK, Randolph AG, Kwiatkowski D, et al. (2004) IL-10 gene polymorphisms are associated with asthma phenotypes in children. Genet Epidemiol 26: 155–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crawley E, Kay R, Sillibourne J, Patel P, Hutchinson I, Woo P (1999) Polymorphic haplotypes of the interleukin-10 5' flanking region determine variable interleukin-10 transcription and are associated with particular phenotypes of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 42: 1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chatterjee R, Batra J, Kumar A, Mabalirajan U, Nahid S, Niphadkar PV, et al. (2005) Interleukin-10 promoter polymorphisms and atopic asthma in North Indians. Clin Exp Allergy 35:914–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bellamy R, Ruwende C, Corrah T, McAdam KP, Whittle HC, Hill AV, et al. (1998) Assessment of the interleukin 1 gene cluster and other candidate gene polymorphisms in host susceptibility to tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis 79: 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lopez-Maderuelo D, Arnalich F, Serantes R, Gonzalez A, Codoceo R, Madero R, et al. (2003) Interferon-gamma and interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms in pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167: 970–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fitness J, Floyd S, Warndorff DK, Sichali L, Malema S, Crampin AC, et al. (2004) Large-scale candidate gene study of tuberculosis susceptibility in the Karonga district of northern Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg 71: 341–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shin HD, Park BL, Kim LH, Cheong HS, Lee IH, Park SK (2005) Common interleukin 10 polymorphism associated with decreased risk of tuberculosis. Exp Mol Med 37: 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amirzargar AA, Rezaei N, Jabbari H, Danesh AA, Khosravi F, Hajabdolbaghi M, et al. (2006) Cytokine single nucleotide polymorphisms in Iranian patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Cytokine Netw 17: 84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oral HB, Budak F, Uzaslan EK, Basturk B, Bekar A, Akalin H, et al. (2006) Interleukin-10 (IL-10) gene polymorphism as a potential host susceptibility factor in tuberculosis. Cytokine 35: 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oh JH, Yang CS, Noh YK, Kweon YM, Jung SS, Son JW, et al. (2007) Polymorphisms of interleukin-10 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha genes are associated with newly diagnosed and recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis. Respirology 12: 594–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ma Z, Xiao P, Tang L, Liu J, Tan Y, Wang Y, et al. (2007) A study on the correlation between the polymorphlsm of Interleukin 10 gene and susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis. Guangdong medical journal 28: 1243–1245. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ates O, Musellim B, Ongen G, Topal-Sarikaya A (2008) Interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphisms in tuberculosis. J Clin Immunol 28: 232–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Selvaraj P, Alagarasu K, Harishankar M, Vidyarani M, Nisha RD, Narayanan PR (2008) Cytokine gene polymorphisms and cytokine levels in pulmonary tuberculosis. Cytokine 43: 26–33. 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu F, Qu Y, Tang Y, Cao D, Sun P, Xia Z (2008) Lack of association between cytokine gene polymorphisms and silicosis and pulmonary tuberculosis in Chinese iron miners. J Occup Health 50: 445–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moller M, Nebel A, van Helden PD, Schreiber S, Hoal EG (2009) Analysis of eight genes modulating interferon gamma and human genetic susceptibility to tuberculosis: a case-control association study. BMC Infect Dis 10:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thye T, Browne EN, Chinbuah MA, Gyapong J, Osei I, Owusu-Dabo E, et al. (2009) IL10 haplotype associated with tuberculin skin test response but not with pulmonary TB. PLoS ONE 4: e5420 10.1371/journal.pone.0005420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Trajkov D, Trajchevska M, Arsov T, Petlichkovski A, Strezova A, Efinska-Mladenovska O, et al. (2009) Association of 22 cytokine gene polymorphisms with tuberculosis in Macedonians. Indian J Tuberc 56: 117–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Taype CA, Shamsuzzaman S, Accinelli RA, Espinoza JR, Shaw MA (2010) Genetic susceptibility to different clinical forms of tuberculosis in the Peruvian population. Infect Genet Evol 10: 495–504. 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang H, Liang Z, Liu X, Wang F (2010) Association between polymorphisms of interleukin-10, interferon-γ gene and the susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis. Chin J Epidemiol 31: 155–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Akgunes A, Coban A, Durupinar B (2011) Human leucocyte antigens and cytokine gene polymorphisms and tuberculosis. Indian J Med Microbiol 29: 28–32. 10.4103/0255-0857.76520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ben-Selma W, Harizi H, Boukadida J (2011) Association of TNF-alpha and IL-10 polymorphisms with tuberculosis in Tunisian populations. Microbes Infect 13: 837–843. 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liang L, Zhao YL, Yue J, Liu JF, Han M, Wang H, et al. (2011) Interleukin-10 gene promoter polymorphisms and their protein production in pleural fluid in patients with tuberculosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 62: 84–90. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00791.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ramaseri SS, Hanumanth SR, Nagaraju RT, Neela VSK, Suryadevara NC, Pydi SS, et al. (2012) IL-10 high producing genotype predisposes HIV infected individuals to TB infection. Hum Immunol 73: 605–611. 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma H (2012) Prevalence of tuberculosis infection in contacts of TB patients and susceptibility of TB in Shanghai. M.Sc. Thesis, Fudan University. Available: http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-102_46-1013101728.htm. Accessed 12 February 2014.

- 33.Ma M (2012) Tuberculosis immunity related gene polymorphisms and pulmonary tuberculosis susceptibility. Ph.D. Thesis, The Academy of Military Medical Science. Available: http://www.doc88.com/p-4933076450856.html. Accessed 17 February 2014.

- 34. Meilang Q, Zha D, Huang L, Duo L, Lu X, Ying B, et al. (2012) Study on association between interleukin-10 gene polymorphism with pulmonary tuberculosis in Tibetans. Modern preventive medicine 39: 3607–3610. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xin D, Jiang L, Yang X, Guo W, Fu F (2012) A case-control study on the association between IL-10 genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis. China Hwalth Care & Nutrition 11: 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Garcia-Elorriaga G, Vera-Ramirez L, del Rey-Pineda G, Gonzalez-Bonilla C (2013) -592 and -1082 interleukin-10 polymorphisms in pulmonary tuberculosis with type 2 diabetes. Asian Pac J Trop Med 6: 505–509. 10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60086-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meenakshi P, Ramya S, Shruthi T, Lavanya J, Mohammed HH, Mohammed SA, et al. (2013) Association of IL-1beta +3954 C/T and IL-10-1082 G/A cytokine gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol 78: 92–97. 10.1111/sji.12055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lindenau JD, Guimaraes LSP, Friedrich DC, Hurtado AM, Hill KR, Salzano FM, et al. (2014) Cytokine gene polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis in an Amerindian population. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 18:952–957. 10.5588/ijtld.14.0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu P, Song J, Su H, Li L, Lu N, Yang R, et al. (2013) IL-10 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 8:e69547 10.1371/journal.pone.0069547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hyun MH, Lee CH, Kang MH, Park BK, Lee YH (2013) Interleukin-10 promoter gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to asthma: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 8:e53758 10.1371/journal.pone.0053758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang J, Chen Y, Nie XB, Wu WH, Zhang H, Zhang M, et al. (2011) Interleukin-10 polymorphisms and tuberculosis susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 15: 594–601. 10.5588/ijtld.09.0703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pacheco AG, Cardoso CC, Moraes MO (2008) IFNG +874T/A, IL10 -1082G/A and TNF -308G/A polymorphisms in association with tuberculosis susceptibility: a meta-analysis study. Hum Genet 123: 477–484. 10.1007/s00439-008-0497-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liang B, Guo Y, Li Y, Kong H (2014) Association between IL-10 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility of tuberculosis: evidence based on a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9: e88448 10.1371/journal.pone.0088448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Higgins JP, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Egger M, Smith GD, Phillips AN (1997) Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. BMJ 315: 1533–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang JJ, Xia X, Tang S, Wang J, Deng X, Zhang Y, et al. (2013) Meta-Analysis on the associations of TLR2 gene polymorphisms with pulmonary tuberculosis susceptibility among Asian populations. PLoS ONE 8: e75090 10.1371/journal.pone.0075090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Qidwai T, Jamal F, Khan M. Y (2012) DNA sequence variation and regulation of genes involved in pathogenesis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol 75:568–587. 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bellamy R (2000) Identifying genetic susceptibility factors for tuberculosis in Africans: a combined approach using a candidate gene study and a genome-wide screen. Clin Sci (Lond) 98: 245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bellamy R (2006) Genome-wide approaches to identifying genetic factors in host susceptibility to tuberculosis. Microbes Infect 8: 1119–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bellamy R, Beyers N, McAdam KP, Ruwende C, Gie R, Samaai P, et al. (2000) Genetic susceptibility to tuberculosis in Africans: a genome-wide scan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 8005–8009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Finlay EK, Berry DP, Wickham B, Gormley EP, Bradley DG (2012) A genome wide association scan of bovine tuberculosis susceptibility in Holstein-Friesian dairy cattle. PLoS One 7: e30545 10.1371/journal.pone.0030545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mahasirimongkol S, Yanai H, Mushiroda T, Promphittayarat W, Wattanapokayakit S, Phromjai J, et al. (2012) Genome-wide association studies of tuberculosis in Asians identify distinct at-risk locus for young tuberculosis. J Hum Genet 57: 363–367. 10.1038/jhg.2012.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Miller EN, Jamieson SE, Joberty C, Fakiola M, Hudson D, Peacock CS, et al. (2004) Genome-wide scans for leprosy and tuberculosis susceptibility genes in Brazilians. Genes Immun 5: 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Png E, Alisjahbana B, Sahiratmadja E, Marzuki S, Nelwan R, Balabanova Y, et al. (2012) A genome wide association study of pulmonary tuberculosis susceptibility in Indonesians. BMC Med Genet 13: 5 10.1186/1471-2350-13-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Qu HQ, Li Q, McCormick JB, Fisher-Hoch SP (2011) What did we learn from the genome-wide association study for tuberculosis susceptibility? J Med Genet 48: 217–218. 10.1136/jmg.2010.087361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thye T, Vannberg FO, Wong SH, Owusu-Dabo E, Osei I, Gyapong J, et al. (2010) Genome-wide association analyses identifies a susceptibility locus for tuberculosis on chromosome 18q11.2. Nat Genet 42: 739–741. 10.1038/ng.639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stein CM (2011) Genetic epidemiology of tuberculosis susceptibility: impact of study design. PLoS One 7:e1001189 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Middelkoop K, Mathema B, Myer L, Shashkina E, Whitelaw A, Kaplan G, et al. (2015) Transmission of tuberculosis in a South African community with a high prevalence of HIV infection. J Infect Dis 211:53–61. 10.1093/infdis/jiu403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lawn SD, Zumla AI (2011) Tuberculosis. Lancet 378:57–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62173-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Figueiredo JF, Rodrigues Mde L, Deghaide NH, Donadi EA (2008) HLA profile in patients with AIDS and tuberculosis. Braz J Infect Dis 12:278–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kalsdorf B, Skolimowska KH, Scriba TJ, Dawson R, Dheda K, Wood K, et al. (2013) Relationship between chemokine receptor expression, chemokine levels and HIV-1 replication in the lungs of persons exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur J Immunol 43:540–549. 10.1002/eji.201242804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nie W, Liu Y, Bian J, Li B, Xiu Q (2013) Effects of polymorphisms -1112C/T and +2044A/G in interleukin-13 gene on asthma risk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 8: e56065 10.1371/journal.pone.0056065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.