Abstract

Background

Adipocytes, which are the main cellular component of adipose tissue, are the building blocks of obesity. The nuclear hormone receptor PPARγ is a major regulator of adipocyte differentiation and development. Obesity, which is one of the most dangerous yet silent diseases of all time, is fast becoming a critical area of research focus.

Methods

In this study, we initially aimed to investigate whether the ginsenoside Rf, a compound that is only present in Panax ginseng Meyer, interacts with PPARγ by molecular docking simulations. After we performed the docking simulation the result has been analyzed with several different software programs, including Discovery Studio, Pymol, Chimera, Ligplus, and Pose View. All of the programs identified the same mechanism of interaction between PPARγ and Rf, at the same active site. To determine the drug-like and biological activities of Rf, we calculate its absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxic (ADMET) and prediction of activity spectra for substances (PASS) properties. Considering the results obtained from the computational investigations, the focus was on the in vitro experiments.

Results

Because the docking simulations predicted the formation of structural bonds between Rf and PPARγ, we also investigated whether any evidence for these bonds could be observed at the cellular level. These experiments revealed that Rf treatment of 3T3-L1 adipocytes downregulated the expression levels of PPARγ and perilipin, and also decreased the amount of lipid accumulated at different doses.

Conclusion

The ginsenoside Rf appears to be promising compound that could prove useful in antiobesity treatments.

Keywords: adipocyte, ginsenoside Rf, molecular docking, Panax ginseng, PPARγ

1. Introduction

The global prevalence of obesity has been increasing at a dreadful rate, with both developed and developing countries affected by this disease. In 2005, the World Health Organization predicted that at least 400 million adults worldwide were obese; moreover, this number is estimated to double in approximately 10 yr. In Western countries, which generally are also high-income countries, obesity has typically been associated with a high-calorie diet and a low level of physical activity; however, low- and middle-income countries are increasingly dealing with these burdens as well [1]. In combination with heavy smoking or drinking, obesity has been found to be associated with several chronic medical conditions and a limited quality of life [2]. In a systematic review of the economic burden of obesity worldwide, Withrow et al [3] concluded that obesity added for 0.7–2.8% of the total healthcare expenses of a given country; moreover, obese people incurred 30% higher medical costs compared with people of normal weight. Obesity is a complex metabolic disorder, and is related to a higher risk of many important human diseases, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and certain types of cancer such as colorectal, breast, and prostate [4]. Therefore, the development of effective antiobesity drugs is crucial for treating obesity and reducing the risk of its associated disorders. For years, researchers have been searching for drugs or naturally derived compounds that can effectively treat obesity. However, satisfactory results have yet to be achieved; thus, intense research is still focused on the identification of antiobesity agents. Panax ginseng of the Araliaceae family is one of the most beneficial of Asian plants. Since ancient times, ginseng has been used as a curative drug and as a health tonic (especially the dried ginseng root) in countries such as China, Japan, and Korea. Currently, ginseng has also been used in a variety of commercial health products worldwide, including ginseng capsules, soups, drinks, and cosmetics. Chemical studies of ginseng have revealed that it contains saponins, antioxidants, peptides, polysaccharides, fatty acids, alcohols, and vitamins. Saponins, which are also known as ginsenosides, are broadly believed to be the most highly bioactive compounds in ginseng [5]. Based on their chemical structure, ginsenosides are generally divided into two groups: protopanaxadiol (PD) and protopanaxatriol (PT). The PD includes ginsenosides such as Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Rg3, Rh2, and Rh3; for these ginsenosides, the group the sugar moieties are attached to the 3-position of the dammarane-type triterpine. However, the sugar moieties of PT are attached to the 6-position of the dammarane-type triterpine; these ginsenosides include compounds such as Re, Rf, Rg1, Rg2, and Rh1 [6]. Ginsenosides, either as crude or single saponins, were thought for years to be responsible for most pharmacological actions of ginsengs [7]. The ginsenoside Rf, which is a ginseng saponin found only in P. ginseng [8], is a steroid-like compound harboring several sugar moieties that has also been shown to exert protective effects against several diseases [9,10]. Therefore, in this study we investigated whether this ginsenoside interacts with peroxisome proliferator activated receptors gamma (PPARγ) which is the major transcriptional factor of adipocyte and is mainly present in adipose tissue. The biology of PPARs indicates for the regulation of lipid metabolism and function [11]. Molecular docking simulation was performed and then validated this result with five different software programs; each program predicted the same mechanism of bond formation at the same active site residues of protein with compound Rf. Next, we characterized Rf pharmacologically by determining its absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxic (ADMET) properties and its prediction of activity spectra for substances (PASS). To validate these observations experimentally and to observe the outcome of Rf binding to PPARγ, we carried out in vitro experiments in which 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with Rf. These experiments revealed that Rf was effective in reducing lipid accumulation. Moreover, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analyses also revealed that Rf treatment of 3T3-L1 adipocytes downregulated the expression of PPARγ and perilipin. The in silico, ADMET, PASS, and experimental results presented here indicated that Rf may be an applicatory compound to ameliorate obesity.

2. Methods

2.1. Docking and screening

Molecular docking is a commonly and frequently applied technique in drug design, due to the ability of this technique to predict the specific positioning of a ligand in the active site of a protein [12]. For any sort of biological process, interactions between biomolecules are elemental are fundamental. Therefore we performed molecular docking to simulate the interaction of Rf from P. ginseng with PPARγ. Therefore, the molecular docking program Autodock 4.2.3 (La Jolla, USA) was used [13–15]. The structure of Rf was obtained from our in-house database of P. ginseng saponins structures. The crystal structure of PPARγ, at 2.28 Å resolution was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (PDB ID: 2ATH) [16,17]; this structure is a co-crystallization of PPARγ in complex with one of its ligands, 3EA. To obtain the structure of PPARγ alone the co-crystallized ligand was removed from the PDB structure; to confirm the reproducibility of the binding of PPARγ to 3EA, the ligand was redocked into PPARγ. The residues found to interact with 3EA, a known inhibitor of PPARγ, were considered crucial residues in the active site of PPARγ. Previous studies have demonstrated that residues TYR473, HIS449, SER289, and HIS323 are crucial for the inhibition of PPARγ [16]. Water molecules were removed from the PPARγ structure, and hydrogen atoms were added. To more precisely identify the binding mode between PPARγ and Rf the Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) was also performed [18–20]. In the molecular docking simulation between PPARγ and Rf, the essential amino acids were selected. The molecular optimization and docking simulation parameters used have been previously described [21]. To validate the docking interaction the simulation output was analyzed with Discovery Studio (DS) 3.5, Chimera, Pymol, Pose View, and Ligplus.

2.2. Prediction of ADMET and PASS prediction

Pharmacokinetic studies of a potential drug generally involve determining its ADMET properties. This determination is particularly important because it has been estimated that more than 50% of all potential drugs fail during clinical trials due to their inadequate ADMET properties [22]. Improvements in computational studies and in the drug discovery process have enabled the identification of several pharmacologically active compounds, which must be optimized and also undergo preclinical ADMET evaluations. It is extremely important to determine the ADMET properties of a compound before clinical trials; thus, we determined the ADMET properties for Rf using methods previously described [23,24]. In addition, we also used another computational program, PASS, to predict the possible biological activities of Rf based on its chemical structure [25,26]. In particular, we determined the possible biological activity scores related to obesity for Rf [27]. This approach yielded a list of potential biological activities mediated by Rf, along with their associated probabilities of activity (Pa) and probabilities of inactivity (Pi).

3. Experimental study

3.1. Materials

The ginsenoside Rf was obtained from the Kyung Hee University Ginseng Research Bank (Yongin, South Korea) in powdered form, and was determined to be ≥95% pure by high-performance lipid chromatography. Insulin and isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX) were obtained from Wako (Tokyo, Japan); dexamethasone was purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was obtained from Welgene (Daegu, Korea). Newborn calf serum was purchased from Gibco (NY, USA), and antibiotic solution was purchased from Biological Industries (Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel).

3.2. Cell culture and differentiation

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% Bovine Calf Serum (BCS) and 1% Antibiotic (AB), at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Differentiation was induced 3 days after confluence was reached (defined as Day 0) by culturing cells in differentiation medium (DM) from day 0 to day 3. The DM contained DMEM, 10% BCS, 1% AB, and DMI (1μM dexamethasone, 0.5mM IBMX, and 10 μg/mL insulin). Cells were additionally fed with growth medium containing DMEM, 10% BCS, and 10 μg/mL insulin on Days 3, 5, and 7. In all experiments, the medium also contained Rf at a concentration of either 10μM or 100μM from Day 0 until the day of the experiment.

3.3. MTT assay

Cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% BCS and Rf at a concentration of 1 μM, 10 μM, 50 μM, or100 μM; cells were then incubated for 48 h. After this incubation, 20 μL of MTT reagent was added to the medium, and cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The medium was then replaced with 100 μL DMSO, and the cells were incubated for another hour. Finally, the resultant ODs at 570 nm were measured with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader

3.4. Oil Red O staining

Cells were differentiated in 24-well plates; on day 8, Oil Red O staining was performed. Cells were fixed with 10% formalin for 1 h, washed with 60% isopropanol, and then stained with Oil Red O solution for 1 h. Excess stain was removed by washing the cells with sterile water, and cells were then dried for imaging. Finally, lipid droplets were solubilized in 100% isopropanol and quantified by determining the resultant absorbances at 520 nm.

3.5. RNA preparation and RT-PCR

Cells were differentiated either in the presence or absence of Rf; on Day 8, total RNA was extracted using a total RNA extraction kit (Intron Biotechnology, Seongnam-si, Korea). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was then synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA with a cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). PCR amplification was then performed using the following gene-specific primers: PPARγ; forward, 5′-ATGGGTGAAACTCTGGGAGATT-3′; reverse, 5′-AGCTTCAATC GGATGGTTCTT-3′; perilipin; forward, 5′-GATCGCCTCTGAACTGAAGG-3′; reverse, 5′-CTTCTCGATGCTTCCCAGAG-3′; beta-actin; forward, 5′-ATGAAGTGTGACGTTGACATCC-3′; reverse, 5′-CCTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGCACGATG-3′. Thermocycling conditions were as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 58°C (PPARγ) or 60°C (perilipin and beta-actin), and extension at 72°C for 1 min; 28 of these cycles were carried out. The resultant PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and visualized with Image J software.

3.6. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

qRT-PCR was performed using real-time rotary analyzer (Rotor-Gene 6000; Corbet Life Science, Sydney, Australia) and 1 μg of cDNA in a 10-μL reaction volume. SYBR Green SensiMix Plus Master Mix (Quantace, London, England), was used with the following gene specific primers: PPARγ; forward, 5′-ATGGGTGAAACTCTGGGAGATT-3′; reverse, 5′-AGCTTCAATCGGATGGTTCTT-3′; perilipin; forward, 5′-GATCGCCTCTGAACTGAAGG-3′; reverse, 5′-CTTCTCGAT GCTTCCCAGAG-3′; beta-actin; forward, 5′-ATGAAGTGTGACGTTGACATCC-3′; reverse, 5′-CCTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGCACGATG-3′. Thermocycling parameters were 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 20 s. Beta-actin was used as an internal control gene.

3.7. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed independently three times: data are presented as means ± standard error (SE). Mean values were compared between the treated groups and the untreated groups using Graph Pad (La Jolla, CA 92037, USA) t test quick calc version 6.04. Statistical significance is designated by the following symbols: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005; and ***p < 0.0005.

4. Results

4.1. Molecular interaction study

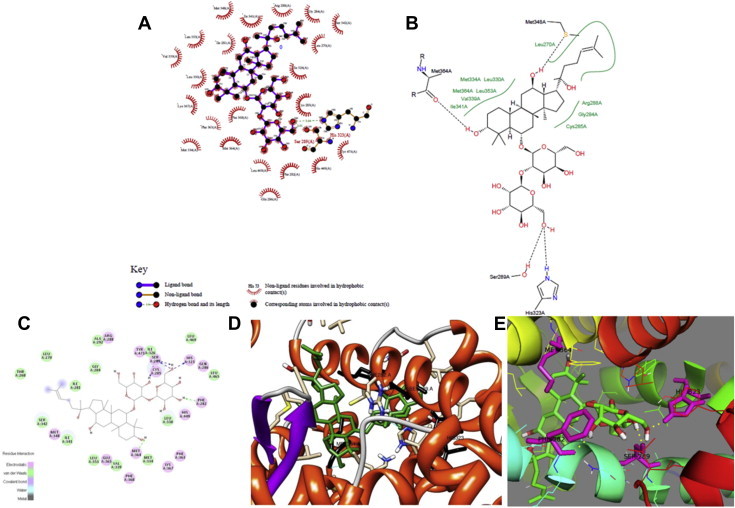

A molecular docking simulation of the interaction between Rf and PPARγ was carried out with Autodock; this interaction was also then analyzed with DS 3.5, Pymol, Chimera, Ligplus, and Pose View. The accuracy of the AutoDock result was confirmed by the observation that it yielded the lowest binding free energy out of all possible docking positions, in addition to assigning hydrogen bonds between PPARγ and Rf. The docking simulation between Rf and PPARγ predicted the formation of two hydrogen bonds at residues Ser289 and His323 in the active site of PPARγ; this simulation also predicted a binding affinity of −2.9 kcal/mol. Both His323 and Ser289 are considered to be important residues for ligand interaction in the active site of PPARγ [28,29]. The high level of agreement between the results from the five different programs supports the mechanism of interaction between Rf and PPARγ, in addition to the specific bonds formed between Rf and PPARγ. The predicted docking interactions of Rf with PPARγ, including the hydrogen bonds of these interactions, are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Hydrogen bond formation between Rf and residues in the active site of PPARγ as visualized by (A) Lig Plus, (B) Pose View, (C) DS 3.5, (D) Chimera, and (E) Pymol.

The structure obtained with DS 3.5 predicted that the hydrogen atoms of PPARγ Ser289 and His323 form a bond with the oxygen atom of Rf. Additionally, two hydrogen bonds are formed between PPARγ Phe282 and Met364 and Rf.

Similarly, the interaction simulated by Pose View predicted the formation of a bond between the hydrogen atoms in the Ser289 and His323 residues of PPARγ and the oxygen atom of Rf. In addition, Pose View predicted the formation of hydrogen bonds between PPARγ Met348 and Met364 and Rf.

The Ligplus simulation also predicted hydrogen bond interactions between the Ser289 and His323 residues of PPARγ and the oxygen atom in Rf.

In agreement with the other simulations, Pymol also predicted hydrogen bonds between the PPARγ active site residues Ser289 and His323 and Rf, in addition to hydrogen bond formation between PPARγ Phe282 and Met364 and Rf.

The Chimera program also yielded the same hydrogen bond formations, between PPARγ Ser289 and His323 and the oxygen atom of Rf. In addition, Chimera predicted additional hydrogen bonds between PPARγ Phe282 and Met364 and Rf.

From the results of docking simulation, it was found that the individual program shows the same mechanism of hydrogen bond formation of ginsenoside Rf at the same active site residue of PPARγ, which are Ser289 and His323.

The control compound 3EA showed interactions at four active site residues: Ser 289, His 323, His 449, and Tyr 473 [16]. These interactions resulted in a binding affinity of −10.0 kcal/mol. Based on these results, Rf was also predicted to exhibit a good binding affinity with PPARγ.

4.2. ADMET and PASS analysis

Using the Qikprop module in the Schrödinger program, the physiochemical and pharmaceutically properties of Rf were determined. These properties included molecular weight, human oral absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, serum protein binding, CYP2D6 inhibition probability, and octanol/water partition coefficient. Because toxicity prediction is also very important in natural product research [30], we also predicted the hepatotoxicity descriptors for Rf using the ADMET module in DS 3.5. The detailed results of the predicted ADMET values for Rf, along with their acceptable ranges, are listed in Table 1. Next, the computational program PASS was used to predict the biological activity spectrum of Rf. This analysis suggested that Rf could exhibit activity (Pa > 0.7) as a transcription factor inhibitor, an antidiabetic agent, a cholesterol antagonist, a cholesterol synthesis inhibitor, an antihypercholesterolemic agent, a cholesterol absorption inhibitor, and a lipid metabolism regulator. All of these functions are directly or indirectly related to fat, as well as to obesity (Table 2).

Table 1.

ADMET results of selected ginsenoside Rf with pharmacokinetic properties

| Ginsenoside | MW | Solubility level | QP (%)a | QplogKhsaa | CYP2D6 inhibitionb | Hepatotoxicityb | QPlogPo/wa | Lipinski rule of 5 violations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rf | 640.8 | −5.3 | 49.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0 | 2.9 | 2 |

Aqueous solubility (Solubility level) (accepted range = −6.5–0.5)

CYP2D6 inhibition = 0 is Non-inhibitor and 1 is inhibitor

Hepatotoxicity = 0 is non-toxic and 1 is toxic

Lipinski rule of 5 violations = Maximum is 4 violations

MW = Molecular weight accepted range 130–725

QP (%) = Percentage of human oral absorption in GI (acceptable range = <25% is poor and >80% is high)

QPlogKhsa = Serum protein binding (acceptable range = −1.5/1.5)

QPlogPo/w = Octanol/water partition coefficient (acceptable range = −0.2 to 6.5)

Predicted values using Qikprop program in Schrödinger

Predicted values using ADMET descriptors in Discovery Studio 3.5

Table 2.

Predicted biological activity (Pa) and inactivity (Pi) of ginsenoside Rf

| Pa | Pi | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| 0.907 | 0.003 | Cholesterol antagonist |

| 0.605 | 0.005 | Transcription factor inhibitor |

| 0.565 | 0.015 | Antidiabetic |

| 0.480 | 0.004 | Cholesterol synthesis inhibitor |

| 0 391 | 0.039 | Antihypercholesterolemic |

| 0.239 | 0.177 | Lipid metabolism regulator |

| 0.049 | 0.011 | Cholesterol absorption inhibitor |

4.3. Experimental study

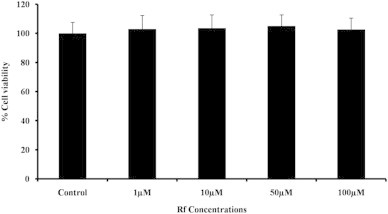

To investigate whether Rf exhibited any cytotoxicity, cell viabilities were determined after 48 h in the presence of various concentrations of Rf, including 1, 10, 50, and 100μM. Rf was not found to be significantly cytotoxic to 3T3-L1 cells, even at the highest concentration tested (100μM; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cytotoxicities of different concentrations of Rf on 3T3-L1 adipocytes. The MTT assay was performed on cells after 48 h of incubation with Rf.

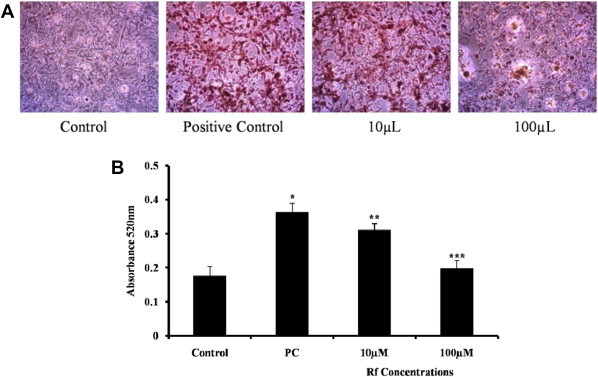

4.4. Oil Red O staining and lipid accumulation

Oil Red O staining was performed to examine the extent of lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes undergoing adipogenesis, either in the presence or absence of Rf. Visualization of Oil Red O-stained cells clearly revealed the accumulation of lipids in DMI-treated cells, whereas cells treated with Differentiation Media Index (DMI) in the presence of Rf accumulated lipids to a lesser extent (Fig. 3A). To quantify the triglyceride contents of the cells, the absorbance of the solubilized Oil Red O was measured for each treatment. Cells differentiated in the presence of Rf (10 and 100μM) contained 14% and 45% less lipid, respectively, compared with positive control differentiated cells (Fig. 3B). This result suggests that Rf treatment inhibits adipocyte differentiation.

Fig. 3.

Effects of Rf (10 and 100 μM) on 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation. Lipid contents were visualized by Oil Red O staining on Day 8 of differentiation (A) and quantified via absorbance measurements (B). *p < 0.0005 between the negative control and positive control groups. **p < 0.005; ***p < 0.0005 between the positive and treated groups.

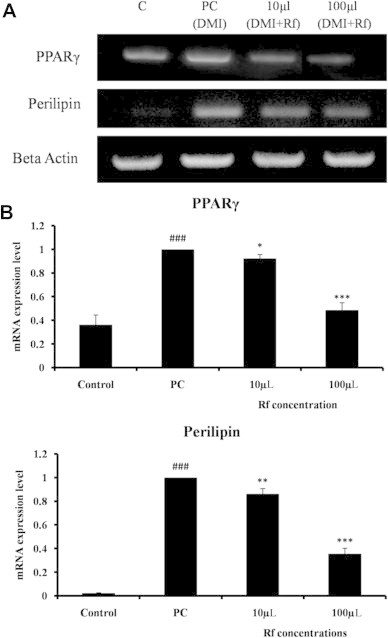

4.5. Gene expression levels of PPARγ and perilipin

Finally, the gene expression levels of PPARγ and perilipin were determined. PPARγ is the main transcription factor driving adipogenesis [11], whereas perilipin is a lipid droplet-associated protein [31]. The upregulation of these genes generally signifies increased triacylglycerol metabolism. Perilipin is found on the surface of every differentiated adipocyte and also envelopes the core triacylglycerols in intracellular lipid droplets; these observations hold true in both transformed adipocytes and also in primary adipocytes derived from white and brown adipose tissue [32].These two markers have been determined to play distinct, yet necessary, roles in adipogenesis; thus, the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels of these two genes were quantified. To this end, 3T3-L1 cells were differentiated, treated with Rf, and the expression profiles of PPARγ and perilipin were investigated by RT-PCR and qRT-PCR. This analysis revealed that the expression levels of PPARγ and perilipin were increased in DMI-treated adipocytes compared with control cells, which did not receive either DMI or Rf. However, the expression levels of PPARγ and perilipin were downregulated when cells were treated with Rf in the presence of DMI (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, treatment with Rf at concentrations of 10 and 100 μM reduced the mRNA levels of PPARγ by 8% and 52%, and the mRNA levels of perilipin by 14% and 65%, respectively (Fig. 4B). These results support the hypothesis that treatment with Rf inhibits adipogenesis, and indicate that the mechanism may involve the downregulation of key mediators of adipogenesis.

Fig. 4.

Transcriptional effects of Rf on adipocytes. Total RNA was isolated on Day 8 of differentiation. Control cells were treated with normal medium, whereas positive control cells received differentiation medium (DMI). Treated groups received differentiation medium with different concentrations of Rf (DMI+Rf). The expression levels of various genes were evaluated by real-time polymerase chain reaction. (A) Amplification products were visualized by gel electrophoresis. (B) Quantification of messenger RNA expression levels by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. ###p < 0.0005 between the control group and the positive control group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005; and ***p < 0.0005 between the DMI-treated positive control group and the DMI+Rf group.

5. Discussion

The prevalence of obesity has increased dramatically worldwide, and it is now considered to be one of the leading global health risks. Moreover, obesity also causes several other health problems such as diabetes, heart disease, and some forms of cancer. Medicinal compounds derived from plants can interact extremely efficiently with biological systems, because they are obtained directly from nature. Thus, plants are considered to be important sources for the identification of novel drug candidates. Until now several studies have been reported showing that P. ginseng has always been an important plant showing efficacy on obesity [33]. Our recent works have reported that ginsenoside F2 and Rh1 had structural interaction with PPARγ and when it was checked at the in vitro level on adipocyte cell line, they possessed efficacy in blocking the process of adipogenesis that may lead to work as an anti- obesity component [27,34]. In this study, we used an automated docking program to generate a model of Rf docked with PPARγ, and observed that Rf was indeed docked closely in the active site of PPARγ in this model. The results of this docking simulation were confirmed by several different docking programs; based on this agreement, we determined the ADMET properties of Rf. The ADMET values indicate that Rf has the potential to be a suitable drug. Moreover, the PASS results also suggest that Rf can perform useful biological activities. Because our computational studies indicated that Rf could be useful as a biologically active, drug-like compound, we next endeavored to test the effects of Rf in in vitro assays using 3T3-L1 adipocytes. We first confirmed that Rf was not cytotoxic at the concentrations used in our assays. Lipid accumulation assays of treated adipocytes revealed that Rf-treated adipocytes exhibited lower levels of intracellular lipids compared with untreated adipocytes, as assessed by both visualization and quantification of absorbances. Moreover, we found that Rf treatment of adipocytes downregulated the mRNA levels of PPARγ and perilipin, as assessed by both RT-PCR and qRT-PCR. Cumulatively, the computational and experimental data presented here suggest that Rf, a ginsenoside obtained from the medicinal plant P. ginseng, may help attenuate obesity by interacting with PPARγ and inhibiting adipogenesis. However, further studies in animal models will be required to assess the true potential of Rf as an antiobesity drug.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not possess any conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Korea Institute of Planning & Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries (KIPET NO: 313038-03-1-SB010) and also supported by a grant from the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (SSAC, grant#: PJ00952903).

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/facts/obesity/en/print.html.

- 2.Sturm R. The effects of obesity, smoking, and drinking on medical problems and costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:245–253. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Withrow D., Alter D.A. The economic burden of obesity worldwide: a systematic review of the direct costs of obesity. Obes Rev. 2011;12:131–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao Y. Angiogenesis modulates adipogenesis and obesity. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2362–2368. doi: 10.1172/JCI32239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paek K.Y., Chakrabarty D., Hahn E.J. Application of bioreactor systems for large scale production of horticultural and medicinal plants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2005;81:287–300. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seo J.Y., Lee J.H., Kim N.W., Her E., Chang S.H., Ko N.Y., Yoo Y.H., Kim J.W., Seo D.W., Han J.W. Effect of a fermented ginseng extract, BST204, on the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in murine macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:929–936. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaku T., Miyata T., Uruno T., Sako I., Kinoshita A. Chemico-pharmacological studies on saponins of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer: II. Pharmacological part Arzneim.-Forsch. Drug Res. 1975;25:539–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan T.W., But P.P., Cheng S.W., Kwok I.M., Lau F.W., Xu H.X. Differentiation and authentication of Panax ginseng, Panax quinquefolius, and ginseng products by using HPLC/MS. Anal Chem. 2000;72:1281–1287. doi: 10.1021/ac990819z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yue L., Qi W., Xiaomin Y., Yan L. Induction of CYP3A4 and MDR1 gene expression by baicalin, baicalein, chlorogenic acid, and ginsenoside Rf through constitutive androstane receptor- and pregnane X receptor-mediated pathways. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;640:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wen J.S., He L., Yue H.Z. Induction of G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by ginsenoside Rf in human osteosarcoma MG-63 cells through the mitochondrial pathway. Oncol Rep. 2014;1:305–313. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desvergene B., Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: nuclear control of metabolism. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:649–688. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.5.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plewczynski D., Zniewski M., Augustyniak R., Ginalski K. Can we trust docking results? Evaluation of seven commonly used programs on PDBbind database. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:742–755. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodsell D.S., Morris G.M., Olson A.J. Automated docking of flexible ligands: applications of AutoDock. J Mol Recognit. 1996;9:1–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1352(199601)9:1<1::aid-jmr241>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones G., Willett P., Glen R.C., Leach A.R., Taylor R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rarey M., Kramer B., Lengauer T., Klebe G. A fast flexible docking method using an incremental construction algorithm. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:470–489. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T.N., Weissig H. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sohn Y.S., Lee Y., Park C., Hwang S., Kim S., Baek A., Son M., Suh J.K., Kim H.H., Lee K.W. Pharmacophore identification for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2011;32:201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris G.M., Goodsell D.S., Halliday R.S. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comp Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park H., Lee J., Lee S. Critical assessment of the automated AutoDock as a new docking tool for virtual screening. Proteins. 2006;65:549–554. doi: 10.1002/prot.21183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badry D., Badry D.B., Totrov M., Abagyan R., Brooks C.L., III Comparative study of several algorithms for flexible ligand docking. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2003;17:755–763. doi: 10.1023/b:jcam.0000017496.76572.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sathishkumar N., Sathiyamoorthy S., Ramya M., Yang D.U., Lee H.N., Yang D.C. Molecular docking studies of anti-apoptotic BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 proteins with ginsenosides from Panax ginseng. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2012;27:685–692. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2011.608663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konstantin V.B., Yan A.I., Nikolay P.S., Andrey A.I., Sean E. Comprehensive computational assessment of ADME properties using mapping techniques. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2005;2:99–113. doi: 10.2174/1570163054064666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karpagam V., Sathishkumar N., Sathiyamoorthy S., Periannan R., Samuel S., Kim Y.J., Yang D.C. Identification of BACE1 inhibitors from Panax ginseng saponins—an Insilco approach. Comput Biol Med. 2013;43:1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sathishkumar N., Karpagam V., Sathiyamoorthy S., Min J.W., Kim Y.J., Yang D.C. Computer-aided identification of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors using ginsenosides from Panax ginseng. Comput Biol Med. 2013;43:786–797. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lagunin A., Stepanchikova A., Filimonov D., Poroikov V. PASS: prediction of activity spectra for biological active substances. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:747–748. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.8.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lagunin A., Filimonov D., Poroikov V. Multi-targeted natural products evaluation based on biological activity prediction with PASS. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:1703–1717. doi: 10.2174/138161210791164063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fayeza M.S., Natarajan S., Yeon J.K., Se Y.K., Deok C.Y. Ginsenoside F2 possesses anti-obesity activity via binding with PPARγ and inhibiting adipocyte differentiation in the 3T3-L1 cell line. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2014 Mar 25 doi: 10.3109/14756366.2013.871006. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yushma B.A., Therese R., Michael R.J., Christos K., Jon S., Robert G.C., Joseph M.S., William D.O.H., Jonathan R.H., Rolf K.B. Synthesis of novel PPARa/c dual agonists as potential drugs for the treatment of the metabolic syndrome and diabetes type II designed using a new de novo design program PROTOBUILD. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:1169–1188. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00146e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruning J.B., Chalmers M.J., Prasad S., Busby S.A., Kamenecka T.M., He Y., Nettles K.W., Griffin P.R. Partial agonists activate PPARg using a helix 12 independent mechanism. Structure. 2007;15:1258–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohan C.G., Gandhi T., Garg D., Shinde R. Computer-assisted methods in chemical toxicity pre diction. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2007;7:499–507. doi: 10.2174/138955707780619554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovsan J., Ben R.R., Souza S.C., Greenberg A.S., Rudich A. Regulation of adipocyte lipolysis by degradation of the perilipin protein. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21704–21711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanchette M.E.J., Dwyer N.K., Barber L.T., Coxey R.A., Takeda T., Rondinone C.M., Theodorakis J.L., Greenberg A.S., Londost C. Perilipin is located on the surface layer of intracellular lipid droplets in adipocytes. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:1211–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fayeza M.S., Yeon J.K., Natarajan S., Seok K.J., Dong U.K., Deok C.Y. Ginseng and obesity: observations from assorted perspectives. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2014;23:1007–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fayeza M.S., Natarajan S., Yeon J.K., Deok C.Y. In silico screening of ginsenoside Rh1 with PPARγ and in vitro analysis on 3T3–L1 cell line. Mol Simulation. 2014 [Google Scholar]