Abstract

Objectives

In this systematic review, we provide an overview of the literature on depression among Asian-Americans and explore the possible variations in depression prevalence estimates by methodological and demographic factors.

Methods

Six databases were used to identify studies reporting a prevalence estimate for depression in Asian-American adults in non-clinical settings. Meta-analysis was used to calculate pooled estimates of rates of depression by assessment type. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed for subgroup analyses by gender, age, ethnicity, and other participant characteristics.

Results

A total of 58 studies met the review criteria (n = 21.731 Asian-American adults). Heterogeneity across the studies was considerably high. The prevalence of major depression assessed via standardized clinical interviews ranged between 4.5% and 11.3%. Meta-analyses revealed comparable estimated prevalence rates of depression as measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (35.6%, 95% CI 27.6%–43.7%) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (33.1%, 95% CI 14.9%–51.3%). Estimates varied by Asian racial/ethnic group and other participant characteristics. Estimates of depression among special populations, which included maternity, caregivers, and homosexuals, were significantly higher than estimates obtained from other samples (58.8% vs 29.3%, p = .003). Estimates of depression among Korean and Filipino-Americans were similar (33.3%-34.4%); however, the estimates were twice as high as those for Chinese-Americans (15.7%; p = .012 for Korean, p = .049 for Filipino).

Conclusion

There appears to be wide variability in the prevalence rates of depression among Asian-Americans in the US. Practitioners and researchers who serve Asian-American adults need to be sensitive to the potential diversity of the expression of depression and treatment-seeking across Asian-American subgroups. Public health policies to increase Asian-American access to mental health care, including increased screening, are necessary. Further work is needed to determine whether strategies to reduce depression among specific Asian racial/ethnic groups is warranted.

Introduction

Depression is one of the most prevalent health issues worldwide. While Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) places a considerable burden on both society and the individual, poor health and impaired functioning are also found to be associated with depressive symptoms [1, 2]. To reduce mental health disparities in the US, it is important to evaluate whether depression varies by racial/ethnic groups. Progress has been made in the understanding of some racial and ethnic differences in depression for African Americans and Latinos. Latinos have been found to have higher prevalence rates of 12-month MDD compared to other ethnic groups [3]. African Americans have been found to have higher rates of persistence of MDD (lasting for 12 months within an individual’s lifetime), that the MDD is usually left untreated, that is more severe and more disabling compared to non-Hispanic Whites [4]. Furthermore, subgroup differences in depression among African Americans have been documented; Caribbean blacks have a higher rate of lifetime MDD prevalence compared to other African Americans [4].

Asian Americans (AA) constitute people with ethnic origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent: Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam [5]. AA is the fastest growing minority population in the US [5]. Paralleling the growing interest in global variations in the expression of clinical features of depression and non-Western treatments for depression, more studies are examining ethnic differences among Asians [6, 7]. Lee and colleagues reported ethnic variations in MDD onset among AA using nationally representative data and that poverty rate, age, and gender differently influenced the MDD onset among AA [8].

Although the prevalence of MDD among AA in community samples is reported to be moderate to low [9], high levels of depressive symptoms among AA adults have been described [10]. Among AA, depression tends to be very persistent, lasting long periods of time, and AA are less likely to seek treatment and adequate care compared to non-Hispanic Whites [11–13]. Depression may go under-recognized because of language and health literacy barriers, acculturation levels, or somatic presentations [14]. Yet, the overall prevalence of depression among various AA groups is still unclear. This is partially because some researchers often combine Asian with other minority groups in a category of ‘other’ or even exclude Asians from their studies [15, 16]. Thus, there is a need for a better understanding of depression among AA in the community in order to provide adequate mental and physical health services.

There are various methods to assess depression in community samples. Some tools enable depression diagnosis according to the definitions and criteria of ICD-10 and DSM-IV (e.g., Composite International Diagnostic Interview, CIDI), whereas other screening measures are based on general symptoms [e.g., Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Depression Inventory (HDI), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)]. A recent review of depression among AA attributed variation in prevalence to the instruments used to measure depression and by the context of each study [12]. AA who suffer from MDD may not report sadness or depressed mood as their primary complaint, and thus may be less likely to meet clinical criteria when using a tool such as the CIDI [12]. The most commonly used tool to assess depression among AA is the CESD. In this particular ethnic group, a high rate of somatic symptoms of depression—such as changes in appetite, headaches, backaches, stomachaches, insomnia, or fatigue—has been reported using the CESD [12].

The purpose of this study was to: systematically review the estimates of depression prevalence among various ethnic subgroups of AA in community samples, derive synthesized estimates of depression, and examine possible gender, ethnicity, other participant characteristics (e.g., age, parents for teenagers, maternity, homosexuals), and methodological factors associated with variation in these estimates. By providing an estimate of depression prevalence among AA in the community, the results of this study would be beneficial to the development of policies that aim to reduce mental health disparities in the US.

Methods

The protocol and data extraction forms were designed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis: the PRISMA Statement [17, 18]. The following six databases were systematically searched using a comparable search strategy, with adapted terms for each database: PubMed, MEDLINE (OVID), CINAHL (EBSCOHost), PsychINFO (OVID), Web of Science (Web of Knowledge), and the Cochrane Library. Keywords were “Asian-Americans” and “depression/depressive symptoms”, and any matched subject headings or MeSH terms. For example, the search strategy in PubMed was: ((Asian Americans) OR Asian American)) AND (((((("Depression, Postpartum"[Mesh] OR "Depressive Disorder, Treatment-Resistant"[Mesh] OR "Depression, Chemical"[Mesh] OR "Depressive Disorder, Major"[Mesh] OR "Major Depressive Disorder 1" [Supplementary Concept] OR "Major Depressive Disorder 2" [Supplementary Concept] OR "Depression"[Mesh] OR "Depressive Disorder"[Mesh]))) OR depress*) OR depressive symptom) OR depression).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: full-text, published, peer-reviewed, English-language studies conducted in the US, target population of adults (≥ age 18), a reported prevalence level for depression, and conducted in a community setting. Studies published during the past 10 years (from 2004 to 2014) were included to provide a current prevalence of depression. Studies that did not provide a prevalence estimate or sufficient information from which a prevalence could be calculated, as well as those conducted in clinical care settings, were excluded.

Retrieved articles were exported to a reference manager and duplicates were hand-searched and removed. Two reviewers (H.J.K. and K.T.) independently reviewed all titles. After the first title review, the two reviewers independently reviewed selected abstracts. Full-text articles were selected when the two reviewers agreed that the article met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. H.J.K conducted the primary data extraction. All articles were examined independently by a second reviewer (K.T.). Inter-reviewer disagreement was minimal, and inconsistencies were discussed and resolved. References for all the articles were also scanned (citation tracking) for further relevant source papers, and similar procedures were used to include or exclude them.

Risk of bias in reporting depression prevalence in individual studies was assessed using the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ) [19]. These criteria include sample size, methods for selecting participants, methods for measuring exposure variables, methods to deal with any design-specific issues such as recall or interviewer bias, and analytical methods to control for confounding factors. Because we focused only on sample characteristics and prevalence of depression for this review, four items: sample size (≥500 vs. <500), sampling methods (random vs. convienient), participation rate (reported vs. unreported or <50%), and eligibility criteria (provided vs. unprovided) were reviewed for each article. Total scores ranged from 0 to 4, with a smaller number indicating a higher risk of bias.

We performed meta-analyses to calculate pooled estimates of depression prevalence by method of measurement with Stata (version13.1, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Studies that used the standard questionnaire items and cut-points for each measure were included in the meta analysis. Heterogeneity—differences in the prevalence of depression across studies—arises when there are clinical or methodological differences between studies (i.e., participants characteristics, outcomes, or study design). This information is important in meta-analysis because the presence of heterogeneity can influence the pooled prevalence; high heterogeneity may produce misleading results [20]. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using I 2, with thresholds of ≥ 25%, ≥ 50%, and ≥ 75% indicating low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [21]. To investigate heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses by gender (% of women), age, ethnicity, and other participant characteristics. Random-effects metaregression models (DerSimonian & Laird, with 95% CIs) were conducted to explore the subgroup differences with sample size as a covariate. We also conducted sensitivity analyses for prevalence of depression by including studies that used modified questionnaires or alternative cut-points, and by excluding studies with high risk of bias or with unreported participation rates. Egger’s tests of publication bias were performed to assess publication bias due to preferential publication of small studies reporting high prevalence estimates [22].

Results

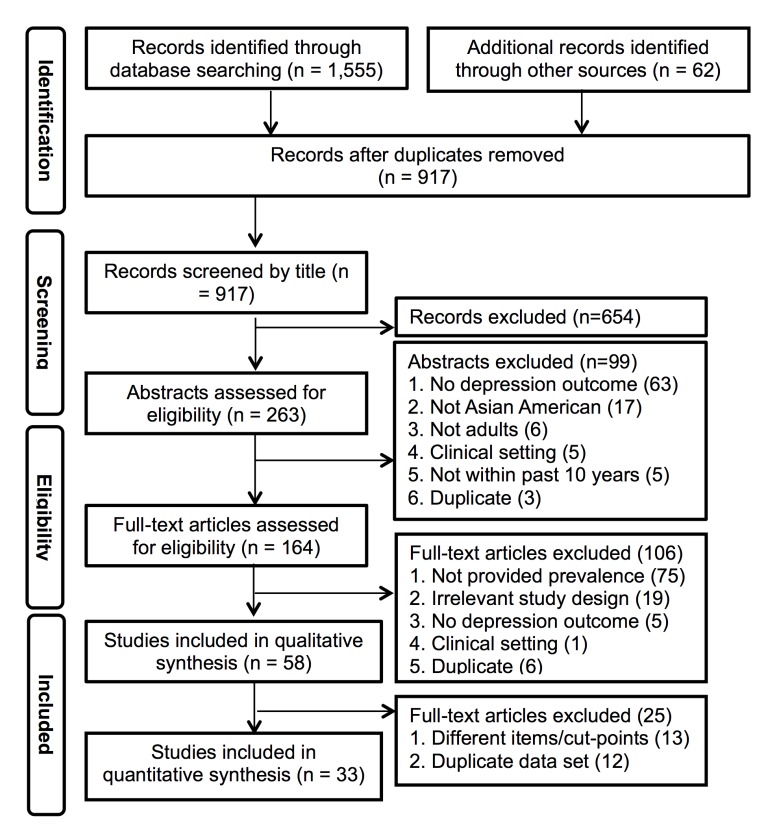

The literature search yielded 1,555 articles. An additional 62 articles were found through Google Scholar and relevant bibliographies. After removal of duplicates, the title screening process identified 263 potentially eligible studies (Fig 1). After abstracts were screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 58 studies remained for qualitative synthesis (a total sample of 21,731 adults) [23–80].

Fig 1. Flow diagram for review of studies of prevalence of depression in Asian Americans.

The prevalence of depression and study characteristics of the selected articles are presented in Table 1. Multiple instruments have been used to assess depression. The most commonly used measure was the CESD, with 22 studies using this tool. The majority of the studies used the 20-item CESD and a score of 16 to classify depression. Jang and colleagues prefer a short form consisting of 10 items (with a cut-point of 10 demarcating depression), and these were included in the meta-analyses because a previous study indicated this is comparable to a score of 16 on the full version [81]. Three studies used modified versions of CESD, and one study used a different cut-point. Seven studies used the PHQ; one of the studies used only 2 items, while the others used 9 items in their assessment. Five studies used the GDS, 4 studies used the Hopkins Symptom Check List (HSCL), 2 studies used the BDI, and one study used the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PPDS). One study used screening stem questions of Fresno-CIDI, summed the symptoms that were under each criteria, and generated an estimate of lifetime depressive symptoms.

Table 1. Review of prevalence studies of depression in Asian-Americans.

| Author | Year | Measurement | Cut point | Sample(N) | Sample (Education) | Sample (Ethnicity) | Sample (Characteristics) | Mean age (SD), Range | Women (%) | Study site | Risk of bias | Prevalence(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening measures | ||||||||||||

| Bromberger et al. [23] | 2004 | CESD-20 | 16 | 486 | Chinese:73%; Japanese:83% (≥college) | Chinese, Japanese | Adults | 42–52 | 100.0 | Multiple site | 3 | 14.2 |

| Lam et al. [24] | 2004 | BDI | 16 (cut off for college students)* | 238 | College students | Multiple (Chinese, Filipinos, Indian, Korean, and Vietnamese) | College students | 18.8 (1.4) | 59.5 | New York, Binghamton | 1 | 20.6 |

| Lee & Farran [25] | 2004 | CESD-20 | 16 | 59 | 14yrs (SD = 3.3) | Korean | Caregivers | 57.8 (12.2) | 100.0 | Chicago & LA area | 1 | 71.0 |

| Suen & Tusaie [26] | 2004 | GDS | 14* | 100 | 14yrs (SD = 5.66) | Taiwanese | Elderly | 67.39 (6.99), 60–88 | 47.0 | Northeastern city | 1 | 7.0 |

| Goyal et al. [27] | 2005 | PPDS-35* | 80 (major), 60–79 (minor) | 58 | 50% (≥Mater's degree), 47% (≥college) | Asian Indian | Maternity | 29 (3.43), 22–38 | 100 | No information | 1 | 52; 24 (major), 28 (minor) |

| Jang et al. [28] | 2005 | CESD-10 | 10 | 230 | 58% (≥high school) | Korean | Elderly | 69.8 (7.05), 60–92 | 59.1 | Florida | 1 | 30.0 |

| Alderete et al. [29] | 2006 | Fresno-CIDI (screening stem questions) | Lifetime depressive symptoms | 124 | No Information | Multiple | Women with an abnormal mammogram | 40–80 | 100.0 | San Francisco Bay Area | 1 | 34.7 |

| Goebert et al. [30] | 2006 | CESD-20 | 16 | 39 | 74% (≥college) | Filipino, Japanese, Other | Maternity | 27, 18–35 | 100.0 | Hawaii | 2 | 61.0 |

| Mui & Kang [31] | 2006 | GDS | 11 | 407 | No Information | Multiple (Chinese, Korean, Indian, Filipino, Vietnamese, and Japanese) | Elderly | 72.4 (6.2), 65–96 | 56.0 | New York city | 3 | 45.0 |

| Suen & Morris [32] | 2006 | GDS | 11 | 100 | 14yrs (SD = 5.66) | Taiwanese | Elderly | 67.39 (6.99), older than 60 | 47.0 | Northeastern City | 1 | 16.0 |

| Donnelly [33] | 2007 | PHQ-9 | 5 | 166 | 41% (≥college) | Korean | Adults | 25–81 | No information | East Coast | 1 | 22.9 |

| Tran et al. [34] | 2007 | CESD-19* | 16 | 349 | 14yrs (SD = 6.17) | Vietnamese | Adults | 38.76 (13.76), 18–73 | 52.1 | East Coast metropolitan area | 2 | 30.0 |

| Birman & Tran [35] | 2008 | HSCL-25 | 1.75 | 212 | 10yrs (SD = 2.58) | Vietnamese | Adults, refugee | 48.84 (7.14), 22–65 | 49.1 | Washington DC, MD | 1 | 20.8 |

| Chae & Yoshikawa [36] | 2008 | CESD-20 | 16 | 192 | No Information | Multiple (East Asian, South Asian, Southeast Asian, Filipino, and Other) | Gay | 18–40s | 0.0 | Northeastern City | 1 | 44.2 |

| David [37] | 2008 | CESD-20 | 16 | 248 | 41% (≥college) | Filipino | Adults | 28.4 (9.9), 18–66 | 48.8 | Internet | 1 | 29.8 |

| Donnelly & Kim [38] | 2008 | PHQ-9 | 5 | 112 | 53% (≥college) | Korean | Elderly | 57–81 | No information | Northeast metropolitan area | 1 | 36.0 |

| Hwang & Goto [39] | 2008 | HDI-23 | 19 | 107 | College students; years in college mean 2.92(SD 1.64) | Multiple (Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese, Taiwanese, and Korean) | College students | 66.4 | Rocky Mountain region | 1 | 14.0 | |

| Yoon & Lau [40] | 2008 | BDI-II | Clinical cut off* | 140 | College students | Multiple (South East, East-Chinese, Japanese, and Korean, and Filipino | College students | 19.8 (2.05) | 79.0 | West Coast | 1 | 17.0 |

| Jang et al. [41] | 2009 | CESD-10 | 10 | 230 | 65% (≥high school) | Korean | Elderly | 68.5 (6.40), 60–94 | 54.8 | Florida | 1 | 36.0 |

| Kang et al. [42] | 2009 | GDS | 11 | 120 | No Information | Korean | Elderly | 71.2 (5.0), 64–91 | 55.0 | Arizona | 1 | 38.1 |

| Kim [43] | 2009 | CESD-20 | 16 | 78 | 15 yrs (SD = 2.58) | Korean | Adults | 43.68 (4.25), 34–57 | 62.8 | Pacific Northwest | 1 | 30.0 |

| Cheung et al. [44] | 2010 | HSCL-25 | 1.75 | 205 | 68.3% (≥college) | Korean | Adults | 44 (11.0) | 55.0 | Huston, Texas | 1 | 18.5 |

| Hwang et al. [45] | 2010 | HDI-23 | 19 | 105 | No Information | Chinese | Parents for teenagers | 47.32 (4.67), 36–60 | 100.0 | Western US | 1 | 4.5 |

| Kim et al. [46] | 2010 | CESD-20 | 16 | 172 | 15 yrs (SD = 3.04) | Korean | Parents for teenagers | 40.90 (3.53) | 69.2 | Pacific Northwest | 1 | 30.1 |

| Li & Hicks [47] | 2010 | CESD-20 | 16 | 168 | 65% (≥college) | Chinese | Adults | 34 (12.0) | 100.0 | Boston | 3 | 26.0 |

| Bernstein et al. [48] | 2011 | CESD-20 | 21* | 304 | 65%(≥college) | Korean | Adults | 46.7 (14.3) | 56.6 | New York | 1 | 13.2 |

| Hahm et al. [49] | 2011 | CESD-20 | 16 | 400 | 86% (≥college) | Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese, Other | Adults | 18–35 | 100.0 | Massachusetts | 2 | 31.0 |

| Herman et al. [50] | 2011 | CESD-20 | 16 | 589 | College students | Japanese, Filipino, Other | College students | 19.7 (4.0), 18–53 | 67.2 | Hawaii | 3 | 38.5 |

| Jang et al. [51] | 2011 | CESD-10 | 10 | 675 | 70% (≥high school) | Korean | Elderly | 70.2 (6.87), 60–96 | 58.8 | Florida | 2 | 30.8 |

| Kim [52] | 2011 | CESD-20 | 16 | 99 | Female:15yrs(SD = 2.78); males:16yrs(SD = 3.17) | Korean | Parents for teenagers | F: 42.20 (3.68), M: 45.06 (4.21) | 64.6 | Pacific Northwest | 1 | 28.4 |

| Berg et al. [53] | 2012 | PHQ-2* | 3 | 495 | 70% (≥college) | Multiple | Adults | 32 | 48.6 | Minnesota | 3 | 4.9 (Smoker 19.6) |

| Harada et al. [54] | 2012 | CESD-11 | 9* | 3139 | No Information | Japanese | Elderly | 71–93 | 0.0 | Multiple site | 2 | 9.7 |

| Huang et al. [55] | 2012 | CESD-12 or CIDI-SF | No information* | 1150 | 70% (≥college) | Multiple | Maternity | US born 29.2 (.71); Foreign-born 31.2 (0.26) | 100.0 | Multiple site | 4 | 4.57 (US-born 6.8; Foreign-born 4.1) |

| Kim [56] | 2012 | CESD-20 | 16 | 72 | Females:15yrs(SD = 3.52), males:16yrs(SD = 1.66) | Korean | Parents for teenagers | F: 37.16 (3.88), M: 39.58 (5.53) | 73.6 | Pacific Northwest | 1 | 29.6 |

| Leung et al. [57] | 2012 | HSCL-25 | 1.75 | 516 | 77% (≥college) | Chinese | Adults | 48.3 (18.1) | 56.8 | Huston, Texas | 1 | 17.4 |

| Park & Rubin [58] | 2012 | CESD-20 | 16 | 516 | 83% (≥college) | Korean | Adults | 39.36 (9.32), 21–82 | 51.6 | California and Texas | 2 | 48.0 |

| Cheung et al. [59] | 2013 | HSCL-25 | 1.75 | 43 | 65% (≥college) | Japanese | Adults | 38.3 (12.2) | 56.0 | Huston, Texas | 1 | 11.6 |

| Lemieux et al. [60] | 2013 | CESD-20 | 16–26 (mild depression), 27+ (major depression) | 319 | 33% (>college) | Multiple (Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, and Other Asians) | Men who have sex with men | 31.3 (7.8) | 0 | Washington, DC & Philadelphia, PA | 1 | mild: 49.8, major depression: 11.60 |

| Park et al. [61] | 2013 | PHQ-9 | 5 | 363 | 67% (≥college) | Korean | Adults | 46.33 (14.16), 18–81 | 57.85 | New York City | 1 | 23.1% (mild) |

| Camacho et al. [62] | 2014 | CESD-20 | 16 | 784 | No Information | Chinese | Adults | 45–84 | No information | Multiple site | 2 | 8.16 |

| Chen et al. [63] | 2014 | PHQ-9 | 5–9 (mild), 10–14 (moderate), 15–19 (moderately severe), and 20–27 (severe) | 113 | Undergraduate/graduate students | Multiple (Asian American or Pacific Islander) | Students in degree program (undergraduate vs graduate program) | 24.99 (4.24), 18–35 | 42.5 | No information | 2 | 22.8 (mild), 10 (moderate), 2.7 (moderately severe or severe) |

| Dong et al. [64] | 2014 | GDS-5* | No information* | 78 | 10.7 yrs | Chinese | Elderly | 74.8 (7.8) | 52 | Chicago | 1 | 21.8 |

| Dong et al. [65] | 2014 | PHQ-9 | 1–4 (minimal), 5–9 (mild), 10–14 (moderate), 15–19 (moderately severe), and 20–27 (severe) | 3159 | 30% (9–12 yrs), 21% (≥13yrs) | Chinese | Elderly | 60 years and above | 58.9 | Multiple site | 4 | 37.3 (minimal), 13.3 (mild), 2.8 (moderate), 1.1 (severe) |

| Lee et al. [66] | 2014 | PHQ-9 | 5 (any depression), 10 (moderate to severe) | 630 | 10.9 (4.4) | Korean | Elderly | 70.9 (6.1) | 68.9 | Baltimore—Washington metropolitan area | 3 | 23.2 (any depression), 7.3 (moderate to severe) |

| Standardized clinical interview | ||||||||||||

| Hwang & Myers [67] | 2007 | UM-CIDI | Lifetime MDE* | 1747 | 13yrs (SD = 3.78) | Chinese | Adults | 38.38 (12.65), 18–65 | 49.6 | Los Angeles County | 4 | 6.9 |

| Gavin et al. [68] | 2010 | WMH-CIDI | Lifetime & 12 month MDE | 2178 | Female:38% (≥16yrs), male: 46% (≥16yrs) | Multiple (Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, and Other Asian) | Adults | M: 40.85(0.90), F: 42(0.76) | 52.5 | CPES (NLAAS) data** | 4 | 4.7 |

| Jimenez et al. [69] | 2010 | WMH-CIDI | 12 month MDD (DSM-IV) | 260 | 30.4% (≤11yrs), 19.2% (12yrs), 17.7% (13–15yrs), 32.7% (≥16yrs) | Multiple | Elderly | 60 years and above | No information | CPES (NLAAS) data** | 3 | Lifetime MDE 7.5, lifetime any depressive disorder 7.7, 12 month MDE 2.1, any depressive disorder 2.1 |

| Chou et al. [70] | 2011 | WMH-CIDI | Lifetime MDD | 793 | No Information | Multiple | Adults who reported racial discrimination experiences | 39.4 (13.5) | 47.0 | NLAAS data** | 3 | 8.8 |

| Chae et al. [71] | 2012 | WMH-CIDI | 12 month MDD | 2095 | Female:38% (≥16yrs), male: 46% (≥16yrs) | Multiple (Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, and Other Asian) | Adults | Male: 40.85(0.90), Female: 42(0.76) | 52.5 | NLAAS data** | 4 | 4.7 |

| John et al. [72] | 2012 | WMH-CIDI | 12 month MDD (DSM-IV) | 1530 | 20.2% (≥17yrs), 49.9% (13–16 yrs) | Multiple (Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, and Other Asian) | Adults, being currently employed or unemployed but looking for work | 39 | 47.64 | NLAAS data** | 4 | 5 |

| Sangalang & Gee [73] | 2012 | WMH-CIDI | 12 month MDD (DSM-IV-TR) | 2066 | Some college (25.07%), college graduate (42.87%) | Multiple (Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, and Other Asian) | Adults | 41.27 (0.70), 18–95 | 52.59 | NLAAS data** | 4 | 4.6 |

| Lee et al. [74] | 2013 | WMH-CIDI | Lifetime MDD | 1280 | 59.5% (>High school) | Multiple (Vietnamese, Filipino, and Chinese) | Adults | 44.8 (0.5) | 55.4 | CPES (NLAAS) data** | 3 | 6.8 |

| Zhang et al. [75] | 2013 | WMH-CIDI | Lifetime and 12 month MDD | 600 | 50% (≥16yrs) | Chinese | Adults | 41.59 (0.57), 18–85 | 52.7 | NLAAS data** | 3 | Lifetime 11.3%, 12 month 7.5% |

| Alegria et al. [76] | 2014 | WMH-CIDI | 12 month psychiatric disorder, any depressive (dysthymia, MDD), DSM-IV | 2095 | 42% (≥16yrs) | Multiple | Adults | 18–34 (39.5%), 35–49 (32.2), 50–64 (18%), 65 and over (10.3%) | 52.5 | CPES (NLAAS) data** | 4 | 5.01 |

| Kalibatseva et al. [77] | 2014 | WMH-CIDI | Lifetime MDE (DSM-IV) | 310 | 49.2% (≥16yrs) | Multiple (Vietnamese, Filipino, Chinese, and Other Asian) | Adults, screened as endorsed depressed mood | 39.22 (0.88) | 61.3 | CPES (NLAAS) data** | 2 | 69 |

| Kim & Lopez [78] | 2014 | WMH-CIDI | Lifetime and 12 month MDD (ICD-10 & DSM-IV) | 310 (screened), 2095 (total) | No Information | Multiple (Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, and Other Asian); screened as endorsed depressed mood | Adults | 38.7 (14.1)-screened, 41.0 (14.7)-total | 61 (screened), 53 (total) | NLAAS data** | 4 | Screened- depressed 89%; discouraged about life 84.2%; lost interest in enjoyable things 73.9%; Total- lifetime MDD: 9.2, 12 month MDD: 4.5 |

| Park et al. [79] | 2014 | WMH-CIDI | 12 month MDE (DSM-IV) | 164 | Some college (15.68%), college graduate (30.46%) | Multiple | Elderly age 65+ | 72.35 | 57.49 | NLAAS data** | 3 | 2.59 |

| Tan [80] | 2014 | WMH-CIDI | Lifetime MDD & MDE, 12month MDD & MDE | 487 | No Information | Chinese (those who immigrated as children were excluded) | Adults | No information | No information | CPES (NLAAS) data** | 2 | US born, immigrants, respectively; Lifetime MDD: 20.7, 7.2; 12month MDD: 8.1, 3.7; lifetime MDE: 21.1, 7.8; 12month MDE: 8.6, 3.7 |

* Excluded for meta-analysis due to different items/cut-points;

** Excluded for meta-analysis due to duplicate database; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CESD: Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression; HDI: Hamilton Depression Inventory; PDSS: Postpartum Depression Screening Scale; WMH-CIDI: World Mental Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview; UM-CIDI: University of Michigan’s version of CIDI; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; HSCL: Hopkins Symptom Checklist; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; MDE: Major Depressive Episode; NLAAS: National Latino and Asian American Study; CPES: Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys, the CPES includes the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication, the NLAAS and the National Survey of American Life.

In total, 14 studies were found to use a depression measure based on standardized clinical criteria (Table 1); however, these studies were not included in the meta-analyses because 13 of the studies used the same database, the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS). The other study by Hwang & Myers [67] reported lifetime Major Depressive Episode (MDE) with DSM-IV criteria which was different from other studies; therefore, pooled prevalence of depression measured by standardized clinical approaches were not estimated.

In regard to the risk of bias of individual studies, nearly half of the studies, 28 out of 58, had a score of 1, which indicates a high risk of bias. Specifically, the sample size for 39 studies was less than 500; 38 studies used non-random/convinient sampling methods. Several of the studies sampled from a restricted geographical area, while others represented multiple sites (Table 1). However, both the east and west coasts of the US were represented. Overall, the sample sizes ranged from 39 to 3,159 participants [median = 254; interquartile range (IQR) 120–630]. Most studies included both female and male participants in their samples; 9 studies included only female participants, and one study included only males. The median percentage of females represented in the sample was 56% (IQR 52.0–67.2).

The median of mean ages was 41 years [IQR 38.0–48.9]. Several studies focused on the elderly, 5 studies looked at college students’ depressive symptoms, while others were maternal and parental studies or studies of caregivers. Two studies looked at homosexual AA’s depressive symptoms. While 26 studies included AA from multiple ethnicities, the samples in 16 studies were limited to Koreans, and 8 studies were limited to Chinese. Two studies each for Japanese, Taiwanese, and Vietnamese, and 1 study each for Filipino, and Indian were found.

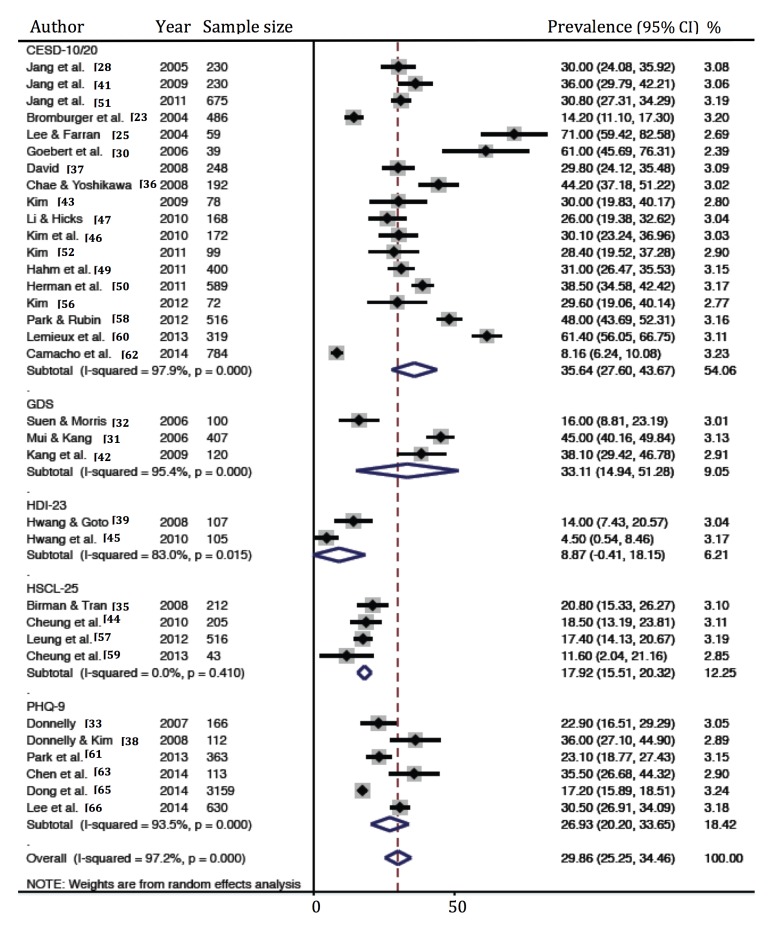

Prevalence of depression

The prevalence rate of depression ranged between 2.6% and 71.0% in individual studies (Table 1). The summary of the prevalence rate of depression by the various tools used to assess it is presented in Table 2. The meta-analytic pooled prevalence rate of depression (Fig 2) using the CESD was estimated to be 35.6% (95% CI 27.6%, 43.7%), with high heterogeneity (I 2 = 97.9%). The prevalence rate of depression measured by the GDS, with a threshold of 11, was 33.1% (95% CI 14.9%, 51.3%), with high heterogeneity (I 2 = 95.4%). The prevalence rate of depression measured with the PHQ-9, with a threshold of 5 indicating mild depression, was 26.9% (95% CI 20.2%, 33.7%), with high heterogeneity (I 2 = 93.5%). A relatively low prevalence rate of depression, 8.9% (95% CI-.4%, 18.2%), was estimated via HDI with a threshold of 19, which is a major depressive clinical cutoff, with high heterogeneity (I 2 = 83%). A prevalence of 17.9% (95% CI 15.5%, 20.3%) with low heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%) was measured by HSCL. Significant publication bias, according to the Egger’s test, was found in the analysis [Egger’s bias = 6.36 (95% CI 5.24%, 10.10%), P < 0.001].

Table 2. Summary of depression prevalence by measurement type.

| Measurement | Definition/cut-point | No. of studies | No. of participants | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | Hetero-geneity, I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized clinical interview | |||||

| CIDI | |||||

| UM-CIDI | Lifetime MDE | 1 | 1747 | 6.9 | |

| WMH-CIDI | Lifetime & 12 month MDD/MDE | 13* | 2095** | Lifetime MDD: 9.2,12 month MDD: 4.5** | |

| Screening measures | |||||

| Fresno-CIDI (screening questions) | Lifetime depressive symptoms | 1 | 124 | 34.7 | |

| HDI-23 | 19 (Major depression clinical cutoff) | 2 | 212 | 8.9 (-.4, 18.2) | 83.0 |

| PHQ | |||||

| PHQ-2 | 3 | 1 | 495 | 4.9 | |

| PHQ-9 | 5 | 6 | 4543 | 26.9 (20.2, 33.7) | 93.5 |

| PPDS | 60 | 1 | 58 | 52.0 | |

| HSCL-25 | 1.75 | 4 | 976 | 17.9 (15.5, 20.3) | 0.0 |

| GDS | |||||

| GDS-30 | 14 | 1 | 100 | 7.0 | |

| GDS-30 | 11 | 3 | 627 | 33.1 (14.9, 51.3) | 95.4 |

| GDS-5 | Not presented | 1 | 78 | 21.8 | |

| BDI | |||||

| BDI | 16 | 1 | 238 | 20.6 | |

| BDI-II | Clinical cut off | 1 | 140 | 17.0 | |

| CESD | |||||

| CESD-10/20 | 10/16 | 18 | 5356 | 35.6 (27.6, 43.7) | 97.9 |

| CESD-11 | 9 | 1 | 3139 | 9.7 | |

| CESD-19 | 16 | 1 | 349 | 30.0 | |

| CESD-20 | 21 | 1 | 304 | 13.2 | |

*Meta-analysis was not conducted due to duplicate dataset;

**data from Kim & Lopez [78]; UM-CIDI: University of Michigan’s version of Composite International Diagnostic Interview; WHM-CIDI: World Mental Health Organization CIDI; HDI: Hamilton Depression Inventory; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; PDSS: Postpartum Depression Screening Scale; HSCL: Hopkins Symptom Checklist; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CESD: Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression.

Fig 2. Prevalence of depression in Asian Americans.

CESD, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HDI, Hamilton Depression Inventory; HSCL, Hopkins Symptom Check List; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Sensitivity and subgroup analysis

The results of sensitivity and subgroup analyses of the pooled prevalence rates of depression by measurement are shown in Table 3. There was no significant pattern in the sensitivity analyses. The prevalence rates of depression did not differ statistically by the percentage of women or between adults and elderly; subgroup effects based on gender and age did not explain the high statistical heterogeneity found in the primary analysis; however, the pooled prevalence rate of depression measured by CESD of special populations, which included maternity, caregivers, and homosexuals, was 58.8% (95% CI 47.2%, 70.4%). This prevalence rate was significantly higher than that of the estimate based on other groups (p = .003).

Table 3. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

| CESD | GDS | PHQ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis | 35.6 (27.6, 43.7), I2 = 97.9%, 18 studies (n = 5356) | 33.1 (14.9, 51.3), I2 = 95.4%, 3 studies (n = 627) | 26.9 (20.2, 33.7), I2 = 93.5%, 6 studies (n = 4543) | |||

| Sensitivity analyses | ||||||

| Including studies that used modified or different items/cut-points | 32.9 (26.2, 39.6), I2 = 98.4%, 21 studies (n = 9148) | 25.6 (8.9, 42.2), I2 = 96.9%, 5 studies (n = 805) | 23.7 (16.0, 31.5), I2 = 97.6%, 7 studies (n = 5038) | |||

| Excluding studies at high risk of bias | 30.6 (17.6, 43.6), I2 = 67.2%, 8 studies (n = 3657) | 27.2 (15.8, 38.7), I2 = 59.9%, 3 studies (n = 3902) | ||||

| Excluding studies with unreported participation rate or <50% | 35.2 (21.3, 49.1), I2 = 58.3%, 6 studies (n = 2198) | 24.1 (16.1, 32.1) I2 = 90.8%, 4 studies (n = 3636) | ||||

| Subgroup analyses | ||||||

| Sig* | Sig* | Sig* | ||||

| % of women | p = .736 | p = .072 | p = .838 | |||

| Age group | ||||||

| Adults | 36.4 (26.7, 46.1), I2 = 98.2%, 15 studies (n = 4221) | p = .876 | 26.3 (19.7, 32.9), I2 = 69.6%, 3 studies (n = 642) | p = .179 | ||

| Elderly | 31.8 (28.7, 34.8), I2 = 17.2%, 3 studies (n = 1135) | 27.4 (15.9, 38.9), I2 = 96.7%, 3 studies (n = 3901) | ||||

| Other participant characteristics | ||||||

| Parents for teenagers | 29.5 (24.7, 34.3), I2 = .0%, 3 studies (n = 343) | p = .659 | ||||

| Special population | 58.8 (47.2, 70.4) I2 = 85.9%, 4 studies (n = 609) | p = .003 | ||||

| Others | 29.3 (20.4, 38.1), I2 = 98.0%, 11 studies (n = 4404) | reference group | ||||

| Subgroup analyses | ||||||

| Ethnicity (Excluded special population) | ||||||

| Korean | 33.3 (27.5, 39.1), I2 = 85.8%, 8 studies (n = 2072) | p = .012 | 31.0 (17.2, 44.8), I2 = 80.9%, 2 studies (n = 200) | 27.6 (22.2, 33.0), I2 = 75.3%, 4 studies (n = 1271) | ||

| Chinese | 15.7 (6.5, 24.9), I2 = 93.2%, 3 studies (n = 1176) | Reference group | ||||

| Japanese | 20.4 (6.9, 34.0), I2 = 86.4%, 2 studies (n = 355) | p = .646 | ||||

| Filipino | 34.4 (23.2, 45.6), I2 = 66.6%, 2 studies (n = 313) | p = .049 | ||||

*Random-effects meta-regression models (with 95% CIs) were conducted to explore the subgroup differences (DerSimonian and Laird) with sample size as a covariate; CESD: Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire.

Group differences among different ethnic groups were identified. The pooled prevalence rate of depression measured by CESD, excluding the special populations—maternity, homosexual, and caregivers—for Koreans was 33.3% (95% CI 27.5%, 39.1%) and this was significantly higher than that for Chinese (15.7%, 95% CI 6.5%, 24.9%, p = .012). For Filipinos, the prevalence rate was estimated to be 34.4% (95% CI 23.2%, 45.6%), and this was also significantly higher than that for Chinese (p = .049). The prevalence rate of depression was estimated to be 20.4% (95% CI 6.9%, 34.0%) for Japanese, which was not significantly different than that for Chinese.

Discussion

This is the first study to estimate the prevalence rate of depression among AA adults in the community using synthesized data obtained from a systematic review of the literature published in the past 10 years. There was variation in the pooled estimates of prevalence by the type of measure used to assess depression, but we found that depression is highly prevalent in AA. The pooled estimates from this review indicate that 35.6% of AA have depressive symptoms as assessed by the CESD, 33.1% by the GDS and 26.9% by the PHQ. These estimates are comparable to those found among patients with chronic disease [82]. Studies indicate that 4.5% to 11.3% of adult AA in the community meet the criteria for major depression, but the majority of estimates come from the same dataset. The differences of magnitude between estimates obtained from symptom screening versus standardized clinical approaches were expected, and this result is consistent with a similar review of depression in a different population [82]. However, attention should be given to the wide gap between the two estimates. As stated above, it has been reported that AA are less likely to be diagnosed with a mental disorder [12]. Further, it has been documented that AA with depression are less likely to access any depression treatment or to receive adequate mental health care compared to non-Hispanic Whites [10, 12]. This is also related to lower rates of detection and treatment of depression, which may lead to a worse prognosis. Given that depressive symptoms are highly prevalent among AA in the US, greater effort should be given to establishing public health policy programs that increase access to mental health care, including adequate screening and a referral system. We also suggest studies linking this issue to health insurance coverage.

We found no gender effect on the prevalence rate of depression from this review. Inconsistent findings have been reported in previous AA depression studies. While no male-female differences were seen in a study by Yeung et al. [83], depressive symptoms have been found to be higher among Asian women than men [84]. Our review also did not find any age group differences. These results may be influenced by the complex and diverse sample characteristics of each study in this review. Specifically, subgroup analysis revealed that the prevalence rate of depression of special population studies that included maternity, homosexual, and caregivers were significantly higher than other groups. Similar findings have been found in non-AA populations such that lesbian, gay, and bisexual groups have higher rates of depression [85]. Depression of perinatal women has been studied and the importance of depression screening for this group has been addressed previously [86]. A recent prospective study found that spousal caregivers of persons with dementia have a high risk of developing a depressive disorder [87]. These findings suggest that some populations could be prioritized in public mental health interventions to prevent and screen for the occurrence of depression. This may also apply to underserved ethnic minorities, including AA, as significant health disparities persist in diverse communities across the US.

Another factor that explains the heterogeneity of the prevalence rate of depression would be ethnicity. The prevalence rate of depression measured by CESD from the studies excluding the special population—maternity, homosexual, and caregivers—was higher among Korean and Filipino subgroups, but not in Japanese, compared to Chinese. The emotional characteristics of Koreans—the feeling of regret regarding neglect of children or parents that would be labeled guilt or shame—has been reported to be associated with depressive symptoms in Koreans [88]. Interestingly, according to a cross-national comparison study of depressive symptoms between Japanese and Whites, Japanese respondents tend to have lower mean scores on the CESD than Whites [89]. The prevalence rate of diagnostic major depression among Chinese-Americans has been found to be higher [75] than the average among the total sample of the NLAAS [78]. Our findings in this review suggest that differences in the prevalence rates of depression exist among Asian ethnicity groups. Heterogeneity of AA ethnic groups in sociohistorical, cultural, economic, and political characteristics has previously been reported [12]. Further studies providing information about the subgroups of AA in this regard are required to build evidence to develop strategies for preventing or reducing depression in AA.

Limitations

The high estimated prevalence rate of depression in AA from this review should be interpreted with caution. Heterogeneity across the studies was considerably high, and the samples were very diverse in age and context. In addition, information related to depression in this population, such as immigration status, length of stay in the US, English language proficiency, and other psychological status (e.g., acculturation, racial discrimination) [12, 14, 90], was not synthesized in this review because of lack of information or heterogeneity of such information across the studies. Significant publication bias was found using the Egger’s test. Small studies with low prevalence may be less likely to be published than studies reporting a high prevalence of depression. Generally, the studies in this review had a high risk of bias in reporting prevalence of depression. Most studies included in the meta-analysis used non-random sampling methods; thus, it is difficult to generalize the results to the total population of AA in the US. However, the problem of sampling AA due to the geographical distribution of Asians in the US has been noted. Outside of the major states of California and New York, obtaining satisfactory samples of AA using random sampling techniques is challenging [12]. This study fills a gap in the literature by providing an estimated aggregated prevalence rate of depression in AA using studies that selected samples from non-clinical settings from relatively diverse areas in the US. Non-standardization of methods, such as the measure used to assess depression across studies also detracts from the findings. For example, the CESD (developed in 1977), the most commonly used tool, does not cover current diagnostic DSM criteria of depression, and contains items such as the perceptions of others, talkativeness, or comparisons with others that are not necessarily related to depression [91].

Conclusion

We have systematically reviewed estimates of the prevalence rate of depression among noninstitutionalized AA and found a wide range of heterogeneity in depression estimates among AA adults. Specific subgroups of the population, such as homosexual, caregiver, and perinatal woman, were more likely to be depressed. Possible variations by ethnicity were also noticed. Practitioners and researchers who serve AA adults need to be sensitive to the potential diversity of depression expression and treatment-seeking across AA subgroups, and pay further attention to better recognize those suffering from depression. Studies examining health insurance coverage and access to medical care for AA are required to provide the evidence needed to establish more effective public health or public policy programs to better recognize of depression, and to increase access to mental health care for AA. Such studies and policy programs may ultimately lead to a decrease in the variation in the prevalence of depression among ethnic minorities and curb treatment disparities.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

Data Availability

All relevant data are included within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA163805).

References

- 1. Fried EN, Randolph. (2014) The impact of individual depressive symptoms on impairment of psychosocial functioning. PLoS ONE 9: e90311–e90311. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lepine JP, Briley M. (2011) The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 7: 3–7. 10.2147/NDT.S19617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oquendo MA, Ellis SP, Greenwald S, Malone KM, Weissman MM, Mann JJ. (2001) Ethnic and sex differences in suicide rates relative to major depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 158: 1652–1658. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, et al. (2007) Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the national survey of American life. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 305–315. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Census Bureau (Mar 2012). The Asian population: 2010. Available: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf. Accessed 11 September 2014.

- 6. Sulaiman A, Bautista D, Liu C, Udomratn P, Bae J, Fang Y, et al. (2014) Differences in psychiatric symptoms among Asian patients with depression: A multi-country cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 68: 245–54. 10.1111/pcn.12118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang J, Cui M, Jiao H, Tong Y, Xu J, Zhao Y, et al. (2013) Content analysis of systematic reviews on effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine. Journal of traditional Chinese medicine 33: 156–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee S, Choi S, Matejkowski J. (2013) Comparison of major depressive disorder onset among foreign-born Asian Americans: Chinese, Filipino, and Vietnamese ethnic groups. Psychiatry Res 210: 315–22. 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang LH, WonPat-Borja AJ. (2007) Psychopathology among Asian Americans In: Leong FTL, et al. eds. Handbook of Asian American Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; pp. 379–405. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chung H, Teresi J, Guarnaccia P, Meyers BS, Holmes D, Bobrowitz T, et al. (2003) Depressive symptoms and psychiatric distress in low income Asian and Latino primary care patients: Prevalence and recognition. Community Ment Health J 39: 33–46. 10.1023/A:1021221806912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee S, Xue Q, Spira A, Lee H. (2014) Racial and ethnic differences in depressive subtypes and access to mental health care in the united states. J Affect Disord 155: 130–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kalibatseva Z, Leong FTL. (2011) Depression among Asian Americans: Review and recommendations. Depression Research and Treatment 2011: 320902 10.1155/2011/320902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee S, Martins S, Keyes K, Lee H. (2011) Mental health service use by persons of Asian ancestry with DSM-IV mental disorders in the United States. Psychiatric Services 62: 1180–6. 10.1176/appi.ps.62.10.1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leng JC, Changrani J, Tseng CH, Gany F. (2010) Detection of depression with different interpreting methods among Chinese and Latino primary care patients: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 12: 234–241. 10.1007/s10903-009-9254-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Riolo SA, Nguyen TA, Greden JF, King CA. (2005) Prevalence of depression by race/ethnicity: Findings from the national health and nutrition examination survey III. Am J Public Health 95: 998–1000. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jonas B, Brody D, Roper M, Narrow W. (2003) Prevalence of mood disorders in a national sample of young American adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38: 618–24. 10.1007/s00127-003-0682-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 62: e1–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International journal of surgery 8: 336–341. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2009). Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. Available: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/60/318/CER-Methods-Guide-140109.pdf. Accessed 18 April 2015. [PubMed]

- 20.Ryan R; Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group (2014). Heterogeneity and subgroup analyses in Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group reviews: planning the analysis at protocol stage. Available: http://cccrg.cochrane.org/consumers-and-communication-review-group-resources-authors. Accessed 18 April 2015.

- 21. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. British Medical Journal 327: 557–560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sterne J. (2009) Meta-Analysis in Stata: An Updated Collection from Stata Journal. College Station, TX: Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bromberger JT, Harlow S, Avis N, Kravitz HM, Cordal A. (2004) Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of depressive symptoms among middle-aged women: The study of women's health across the nation (SWAN). Am J Public Health 94: 1378–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lam CY, Pepper CM, Ryabchenko KA. (2004) Case identification of mood disorders in Asian American and Caucasian American college students. Psychiatr Q 75: 361–373. 10.1023/B:PSAQ.0000043511.13623.1b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee EE, Farran CJ. (2004) Depression among Korean, Korean American, and Caucasian American family caregivers. J Transcult Nurs 15: 18–25. 10.1177/1043659603260010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suen LJ, Tusaie K. (2004) Is somatization a significant depressive symptom in older Taiwanese Americans? Geriatr Nurs 25:157–163. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2004.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goyal D, Murphy SO, Cohen J. (2006) Immigrant Asian Indian women and postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 35: 98–104. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D. (2005) Acculturation and manifestation of depressive symptoms among Korean-American older adults. Aging Ment Health 9: 500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alderete E, Juarbe TC, Kaplan CP, Pasick R, Perez-Stable EJ. (2006) Depressive symptoms among women with an abnormal mammogram. Psychooncology 15: 66–78. 10.1002/pon.923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goebert D, Morland L, Frattarelli L, Onoye J, Matsu C. (2006) Mental health during pregnancy: A study comparing Asian, Caucasian and native Hawaiian women. Matern Child Health J 11: 249–255. 10.1007/s10995-006-0165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mui AC, Kang SY. (2006) Acculturation stress and depression among Asian immigrant elders. Soc Work 51: 243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Suen L, Morris D. (2006) Depression and gender differences—focus on Taiwanese American older adults. J Gerontol Nurs 32: 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Donnelly PL. (2007) The use of the patient health questionnaire-9 Korean version (PHQ-9K) to screen for depressive disorders among Korean Americans. J Transcult Nurs 18: 324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tran TV, Manalo V, Nguyen VT. (2007) Nonlinear relationship between length of residence and depression in a community-based sample of Vietnamese Americans. Int J Soc Psychiatry 53: 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Birman D, Tran N. (2008) Psychological distress and adjustment of Vietnamese refugees in the United States: Association with pre- and postmigration factors. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 78:109–120. 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chae DH, Yoshikawa H. (2008) Perceived group devaluation, depression, and HIV-risk behavior among Asian gay men. Health Psychol 27: 140–148. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. David EJ. (2008) A colonial mentality model of depression for Filipino Americans. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 14: 118–127. 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Donnelly PL, Kim KS. (2008) The patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9K) to screen for depressive disorders among immigrant Korean American elderly. J Cult Divers 15: 24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hwang W, Goto S. (2008) The impact of perceived racial discrimination on the mental health of Asian American and Latino college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 14:326–335. 10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yoon J, Lau AS. (2008) Maladaptive perfectionism and depressive symptoms among Asian American college students: Contributions of interdependence and parental relations. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 14: 92–101. 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jang Y, Chiriboga DA, Kim G, Cho S. (2009) Changes in perceived health and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal analysis with older Korean Americans. J Immigr Minor Health 11: 7–12. 10.1007/s10903-007-9112-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kang SY, Domanski MD, Moon SS. (2009) Ethnic enclave resources and predictors of depression among Arizona's Korean immigrant elders. J Gerontol Soc Work 52: 489–502. 10.1080/01634370902983153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim E. (2009) Multidimensional acculturation attitudes and depressive symptoms in Korean Americans. Issues Ment Health Nurs 30: 98–103. 10.1080/01612840802597663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cheung M, Leung P, Cheung A. (2010) Depressive symptoms and help-seeking behaviors among Korean Americans. International Journal of Social Welfare. 20: 421–429. 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2010.00764.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hwang WC, Wood JJ, Fujimoto K. (2010) Acculturative family distancing (AFD) and depression in Chinese American families. J Consult Clin Psychol 78: 655–667. 10.1037/a0020542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim E, Seo K, Cain KC. (2010) Bi-dimensional acculturation and cultural response set in CES-D among Korean immigrants. Issues Ment Health Nurs 31: 576–583. 10.3109/01612840.2010.483566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li Z, Hicks MH. (2010) The CES-D in Chinese American women: Construct validity, diagnostic validity for major depression, and cultural response bias. Psychiatry Res 175: 227–232. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bernstein KS, Park SY, Shin J, Cho S, Park Y. (2011) Acculturation, discrimination and depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants in New York City. Community Ment Health J 47: 24–34. 10.1007/s10597-009-9261-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hahm HC, Kolaczyk E, Lee Y, Jang J, Ng L. (2012) Do Asian-American women who were maltreated as children have a higher likelihood for HIV risk behaviors and adverse mental health outcomes? Women’s Health Issues 22: e35–43. 10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Herman S, Archambeau OG, Deliramich AN, Kim BS, Chiu PH, Frueh BC. (2011) Depressive symptoms and mental health treatment in an ethnoracially diverse college student sample. J Am Coll Health 59: 715–720. 10.1080/07448481.2010.529625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jang Y, Chiriboga DA. (2011) Social activity and depressive symptoms in Korean American older adults: The conditioning role of acculturation. J Aging Health 23: 767–781. 10.1177/0898264310396214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim E. (2011) Korean American parental depressive symptoms and parental acceptance-rejection and control. Issues Ment Health Nurs 32: 114–120. 10.3109/01612840.2010.529239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Berg CJ, Kirch M, Hooper MW, McAlpine D, An LC, Boudreaux M, et al. (2012) Ethnic group differences in the relationship between depressive symptoms and smoking. Ethn Health 17: 55–69. 10.1080/13557858.2012.654766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Harada N, Takeshita J, Ahmed I, Chen R, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, et al. (2012) Does cultural assimilation influence prevalence and presentation of depressive symptoms in older Japanese American men? The Honolulu-Asia aging study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 20: 337–345. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182107e3b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Huang ZJ, Lewin A, Mitchell SJ, Zhang J. (2012) Variations in the relationship between maternal depression, maternal sensitivity, and child attachment by race/ethnicity and nativity: Findings from a nationally representative cohort study. Matern Child Health J 16: 40–50. 10.1007/s10995-010-0716-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kim E. (2012) Marital adjustment and depressive symptoms in Korean Americans. Issues Ment Health Nurs 33: 370–376. 10.3109/01612840.2012.656822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Leung P, Cheung M, Tsui V. (2012) Help-seeking behaviors among Chinese Americans with depressive symptoms. Soc Work 57: 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Park H, Rubin A. (2012) The mediating role of acculturative stress in the relationship between acculturation level and depression among Korean immigrants in the U.S. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 36: 611–623. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cheung M, Leung P, Tsui V. (2013) Japanese Americans' health concerns and depressive symptoms: Implications for disaster counseling. Soc Work 58: 201–211. 10.1093/sw/swt016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lemieux AF, Nehl EJ, Lin L, Tran A, Yu F, Wong FY. (2013) A pilot study examining depressive symptoms, internet use, and sexual risk behaviour among Asian men who have sex with men. Public Health 127: 1041–1044. 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Park SY, Cho S, Park Y, Bernstein KS, Shin JK. (2013) Factors associated with mental health service utilization among Korean American immigrants. Community Ment Health J 49: 765–773. 10.1007/s10597-013-9604-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Camacho A, Larsen B, McClelland RL, Morgan C, Criqui MH, Cushman M, et al. (2014) Association of subsyndromal and depressive symptoms with inflammatory markers among different ethnic groups: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). J Affect Disord 164: 165–170. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chen AC, Szalacha LA, Menon U. (2014) Perceived discrimination and its associations with mental health and substance use among Asian American and Pacific Islander undergraduate and graduate students. J Am Coll Health 62: 390–398. 10.1080/07448481.2014.917648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dong X, Chen R, Li C, Simon MA. (2014) Understanding depressive symptoms among community-dwelling Chinese older adults in the greater Chicago area. J Aging Health 26: 1155–1171. 10.1177/0898264314527611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dong X, Chang E, Wong E, Wong B, Simon MA. (2014) Association of depressive symptomatology and elder mistreatment in a U.S. Chinese population: Findings from a community-based participatory research study. J Aggression Maltreat Trauma 23: 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lee HB, Han HR, Huh BY, Kim KB, Kim MT. (2014) Mental health service utilization among Korean elders in Korean churches: Preliminary findings from the memory and aging study of Koreans in Maryland (MASK-MD). Aging Ment Health 18: 102–109. 10.1080/13607863.2013.814099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hwang WC, Myers HF. (2007) Major depression in Chinese Americans: The roles of stress, vulnerability, and acculturation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42: 189–197. 10.1007/s00127-006-0152-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gavin AR, Walton E, Chae DH, Alegria M, Jackson JS, Takeuchi D. (2010) The associations between socio-economic status and major depressive disorder among Blacks, Latinos, Asians and non-Hispanic whites: Findings from the collaborative psychiatric epidemiology studies. Psychol Med 40: 51–61. 10.1017/S0033291709006023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Jimenez DE, Alegria M, Chen CN, Chan D, Laderman M. (2010) Prevalence of psychiatric illnesses in older ethnic minority adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: 256–264. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02685.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chou T, Asnaani A, Hofmann SG. (2012) Perception of racial discrimination and psychopathology across three U.S. ethnic minority groups. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 18: 74–81. 10.1037/a0025432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chae DH, Lee S, Lincoln KD, Ihara ES. (2012) Discrimination, family relationships, and major depression among Asian Americans. J Immigr Minor Health 14: 361–370. 10.1007/s10903-011-9548-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. John DA, de Castro AB, Martin DP, Duran B, Takeuchi DT. (2012) Does an immigrant health paradox exist among Asian Americans? Associations of nativity and occupational class with self-rated health and mental disorders. Soc Sci Med 75: 2085–2098. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sangalang CC, Gee GC. (2012) Depression and anxiety among Asian Americans: The effects of social support and strain. Soc Work 57: 49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lee S, Choi S, Matejkowski J. (2013) Comparison of major depressive disorder onset among foreign-born Asian Americans: Chinese, Filipino, and Vietnamese ethnic groups. Psychiatry Res 210: 315–322. 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhang J, Fang L, Wu YB, Wieczorek WF. (2013) Depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Chinese Americans A study of immigration-related factors. J Nerv Ment Dis 201: 17–22. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827ab2e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Alegria M, Molina KM, Chen C. (2014) Neighborhood characteristics and differential risk for depressive and anxiety disorders across racial/ ethnic groups in the United States. Depress Anxiety 31: 27–37. 10.1002/da.22197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kalibatseva Z, Leong FT, Ham EH. (2014) A symptom profile of depression among Asian Americans: Is there evidence for differential item functioning of depressive symptoms? Psychol Med 44: 2567–2578. 10.1017/S0033291714000130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kim JM, Lopez SR. (2014) The expression of depression in Asian Americans and European Americans. J Abnorm Psychol 123: 754–763. 10.1037/a0038114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Park M, Unutzer J, Grembowski D. (2014) Ethnic and gender variations in the associations between family cohesion, family conflict, and depression in older Asian and Latino adults. J Immigr Minor Health 16: 1103–1110. 10.1007/s10903-013-9926-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tan TX. (2014) Major depression in china-to-US immigrants and US-born Chinese Americans: Testing a hypothesis from culture-gene co-evolutionary theory of mental disorders. J Affect Disord 167: 30–36. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. (1994) Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (center for epidemiologic studies depression scale). Am J Prev Med 10: 77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, Hotopf M. (2013) The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 52: 2136–2148. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Yeung A, Chan R, Mischoulon D, Sonawalla S, Wong E, Nierenberg AA, et al. (2004) Prevalence of major depressive disorder among Chinese-Americans in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 26: 24–30. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D. (2011) Gender differences in depressive symptoms among older Korean American immigrants. Social work in public health 26: 96–109. 10.1080/10911350902987003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bostwick W, Boyd C, Hughes T, West B, McCabe S. (2014) Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the united states. Am J Orthopsychiatry 84: 35–45. 10.1037/h0098851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Segre L, Pollack L, Brock R, Andrew J, O'Hara M. (2014) Depression screening on a maternity unit: A mixed-methods evaluation of nurses' views and implementation strategies. Issues Ment Health Nurs 35: 444–454. 10.3109/01612840.2013.879358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Joling KJ, van Marwijk HW, Veldhuijzen AE, van der Horst HE, Scheltens P, Smit F, et al. (2014) The two-year incidence of depression and anxiety disorders in spousal caregivers of persons with dementia: Who is at the greatest risk? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pang KYC. (1998) Symptoms of depression in elderly Korean immigrants: Narration and the healing process. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry 22: 93–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Inaba A, Thoits P, Ueno K, Gove W, Evenson R, Sloan M. (2005) Depression in the United States and Japan: Gender, marital status, and SES patterns. Soc Sci Med 61: 2280–2292. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Iwamasa GY, Hilliard KM. (1999) Depression and anxiety among Asian American elders: A review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 19: 343–357. 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00043-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Santor D. (2006) FOCUS ARTICLE: Eight decades of measurement in depression. Measurement 4: 135 10.1207/s15366359mea0403_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included within the paper and its Supporting Information files.