Abstract

Tuberculosis, caused by the pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is a worldwide public health threat. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is capable of resisting various stresses in host cells, including high levels of ROS and copper ions. To better understand the resistance mechanisms of mycobacteria to copper, we generated a copper-resistant strain of Mycobacterium smegmatis, mc2155-Cu from the selection of copper sulfate treated-bacteria. The mc2155-Cu strain has a 5-fold higher resistance to copper sulfate and a 2-fold higher resistance to isoniazid (INH) than its parental strain mc2155, respectively. Quantitative proteomics was carried out to find differentially expressed proteins between mc2155 and mc2155-Cu. Among 345 differentially expressed proteins, copper-translocating P-type ATPase was up-regulated, while all other ABC transporters were down-regulated in mc2155-Cu, suggesting copper-translocating P-type ATPase plays a crucial role in copper resistance. Results also indicated that the down-regulation of metabolic enzymes and decreases in cellular NAD, FAD, mycothiol, and glutamine levels in mc2155-Cu were responsible for its slowing growth rate as compared to mc2155. Down-regulation of KatG2 expression in both protein and mRNA levels indicates the co-evolution of copper and INH resistance in copper resistance bacteria, and provides new evidence to understanding of the molecular mechanisms of survival of mycobacteria under stress conditions.

Introduction

The ancient pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis causes tuberculosis (TB) in one third of the world’s population and is one of the formidable threats to human health [1]. M. tuberculosis is capable of resisting survival stresses and stays alive in host cells for years that causes the prevalence of TB. The emergence and widespread of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant TB has also raised great concerns for public health [2–4]. The IFN-γ–mediated activation of macrophages is the major immune response of the host cells to M. tuberculosis infection, in which M. tuberculosis residing in phagosomes was cleared by a range of hydrolytic enzymes, bactericidal peptides, and reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in phagolysosome [5–6]. Recent studies have demonstrated that copper ions in host cells possess bactericidal effects against invading mycobacteria [7–8].

It has been broadly accepted that copper ions are an essential nutrient required for survival by all organisms from bacteria to humans. Copper ions are a co-factor of enzymes that undergo reversible oxidation from Cu(I) to Cu(II) in electron transfer reactions. Both Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase SodC and the cytochrome c oxidase in M. tuberculosis use copper as a cofactor [9–10]. However, excess copper ions are detrimental to the survival of bacteria by interacting with hydrogen peroxide to form hydroxyl radicals and by binding to proteins [11]. Thus, host cells are capable of eliminating intracellular bacteria by taking the advantages of toxic properties of copper ions. For example, IFN-γ–activated macrophages traffic the Cu transporter ATP7A to vesicles that fuses with phagosomes to increase Cu content and the bactericidal activity against Escherichia coli [12]. Infection of macrophages with M. avium increases the copper ion concentrations within the phagosomal compartment to control growth of mycobacteria [13]. Accumulation of copper ions was observed in the granulomatous lesions of infected lungs in a guinea pig model of infection and more importantly, copper resistance was found to be essential for virulence of M. tuberculosis [14].

M. tuberculosis is an intracellular pathogen that has evolved many strategies to evade host’s immune surveillance. For example, phagosomes containing M. tuberculosis have limited fusion with the lysosome in macrophages [15–16]. M. tuberculosis also has acquired independent mechanisms to protect its survival from the copper ion-induced toxicity [14, 17]. Studies have shown that metal cation transporter p-type ATPase (CtpV) is a copper responsive gene that encodes a Cu efflux protein located in the inner membrane of mycobacteria and is required for virulence of M. tuberculosis [18–19]. A recent study shows that the copper transporter (MctB) is a pore-forming protein located in the outer membrane (OM) of M. tuberculosis [14] and prevents the accumulation of Cu within the mycobacterial cell probably by efflux of cuprous ions. Using native mass spectrometry, Gold et. al. showed that mycobacterial metallothionein MymT was an important component of Cu homeostasis in M. tuberculosis by binding to copper ions [20]. The Cu repressor (RicR) regulon and its targeted genes are required simultaneously to combat Cu toxicity in vivo [17, 21].

A few studies have analyzed the global responses of mycobacteria to copper ion-induced toxicity. DNA microarrays were used to profile mycobacterial responses to copper ions and identified 30 copper-responsive genes in M. tuberculosis [22]. Characterization of the copper-induced changes in mycobacterial proteomes is also important to understanding mechanisms of M. tuberculosis survival under stress and to provide new targets for controlling this virulent pathogen. In this study, we setup a screening method for selection of the copper-resistant strain from M. smegmatis strain mc2155, and obtained a resistant strain, named mc2155-Cu, which hasa 5-fold higher resistance to copper ions than mc2155. Our result provided evidences that copper-resistant strain has a slow growth trait and is also resistant to isoniazid (INH), as compared to mc2155. On the basis of quantitative proteomic analysis, we showed that the increased copper and INH resistance in mc2155-Cu was resulted from the up-regulation of copper-translocating P-type ATPase expression and the down-regulation of KatG2 expression.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

7H9 liquid medium powder, isoniazid, deoxycholate and iodoacetamide (IAA) were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Middle Brook 7H10 Agar was purchased from Hopebio (Qingdao, China). Albumin, D-glucose, dithiothreitol (DTT), BCA protein assay kit were purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). Glycerol and CuSO4 was from Xilong (Shantou, China). Sequencing grade trypsin was purchase from Promega (Fitchburg, WI). The Total RNA Isolation System and Reverse Transcription kits were purchased from TIANGEN (Beijing, China). SYBR mixture was purchased from Genstar (Beijing, China).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

M. smegmatis strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium supplemented with 10% ADS (50 g/L albumin, 20 g/L D-glucose and 8.1 g/L sodium chloride), 0.05% Tween 80 and 0.2% glycerol or on Middlebrook 7H10 agar supplemented with 0.5% glycerol and 10% ADS. CuSO4 and isoniazid were added to the concentrations needed.

Selection of copper-resistant M. smegmatis strain

Bacteria were diluted 1:100 into 5 ml 7H9 with 10% ADS and 50 μM CuSO4 added. The cultures were grown to log phase and diluted 1:100 into 5 ml 7H9 containing 60 μM CuSO4. This process was repeated until the concentration of CuSO4 reached 300μM. In order to obtain a stable copper-resistant bacterial strain, the bacteria were sub-cultured for 10 generations and spread on 7H10 plates containing 300 μMCuSO4. Single colony was then incubated in liquid media and the minimal inhibition concentration (MIC) of copper was measured.

Measurement of bacterial growth

To measure the growth curve of M. smegmatis mc2155 and copper resistant strain, bacteria mc2155-Cu were grown to OD600 of 0.2–0.5, and diluted 1:1000 in media without CuSO4. The OD600 values of cultures were measured with a spectrophotometer every 3 hours. All the measurements were replicated three times.

Determination of MICs to copper and isoniazid

The measurement of the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) was performed on solid media plates. 10 μL of a 105-cells/ml suspension of M. smegmatis strains was streaked on 7H10 plates with different concentrations of CuSO4 or isoniazid. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 days. Then the numbers of viable bacteria were counted. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of drug that inhibited the visible bacterial growth of M. smegmatis after 4 day incubation. All assays were repeated three times.

Isoniazid resistant assay

Bacteria were added with 0.1 mg/ml isoniazid for 3 h, and diluted several times. 20 μL of a 105-cells/ml bacteria were spread on 7H10 plates, and incubated at 37°C for 4 days. The number of viable bacteria was counted to determine the survival rate of bacteria. A two-sided t-test was used to determine whether the copper-resistant strain was also resistant to isoniazid as compared to mc2155 strain.

Metabolomic analysis

Bacteria were collected and washed with ice-cold PBS twice. Then bacteria were metabolically quenched in precooled H2O/ACN/methanol (2:4:4) and lysed by grinding in Beadbeater for 3 min. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 30 min. The concentrations of bacterial metabolites were estimated by the protein content determined with the BCA assay. One part of samples was labeled with the TMT reagents to quantify the amine-containing molecules, and the other part was dried and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. For TMT labeling, the samples were dried and redissolved in 50 μL 200 mM tetraethylammonium bromide (TEAB), and incubated with TMT reagent for 1 h at room temperature and the reaction was quenched with 5% hydroxylamine. The samples were stored at -80° for LC-MS/MS analysis. For LC-MS/MS analysis of metabolites, samples were separated by RP chromatography and analyzed in both negative mode and positive mode using a Dionex U3000 HPLC coupled to a Q Exactive mass spectrometer. The data were collected using the Xcalibur 2.1.3 software in data-dependent acquisition mode.

Proteomic Analysis

Bacteria were washed twice with PBS, and lysed with 8 M Urea in PBS. Protein concentrations were measured by the BCA method. Equal amount of proteins from M. smegmatis mc2155 and copper-resistant M. smegmatis (100 μg) were reduced with10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylated with 25 mM iodoacetalmide (IAM). Samples were diluted with PBS to 1.5 M Urea followed by digestion with trypsin of a 1:100 protease/protein ratio at 37°C overnight. The samples were desalted by Oasis HLB columns (Waters, MA). Peptides from different samples were labeled with tandem mass tags (TMT) reagents (Thermo, Pierce Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, the TMT reagents were dissolved in acetonitrile and added to the peptide solution. The reaction was kept at room temperature for 1 hour, and quenched by 5% hydroxylamine for 15 min. The TMT labeled peptides were mixed and desalted by HLB column.

The peptides were fractionated by a UPLC3000 system (Dionex, CA) with a XBridgeTM BEH300 C18 column (Waters, MA). Mobile phase A is H2O with ammonium hydroxide, pH 10; and mobile phase B is acetonitrile in ammonium hydroxide pH 10. Peptides were separated with the followed gradients: 8% to 18% phase B, 30 min; 18% to 32% phase B, 22 min. 48 fractions were collected, dried by a speedvac, combined into 12 fractions, and redissolved in 0.1% formic acid.

For quantitative proteomic analysis, the TMT-labeled peptides were separated by a 60-min gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.250 μl/min with an EASY-nLCII integrated nano-HPLC system (Proxeon, Denmark), which is directly interfaced with a Q Exactive mass spectrometer. The analytical column was a fused silica capillary column (75 μm ID, 150 mm length; packed with C-18 resin, Lexington, MA). Mobile phase A consisted of 0.1% formic acid and mobile phase B consisted of 100% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid.

The Q Exactive mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent acquisition mode using the Xcalibur 2.1.3 software and there was a single full-scan mass spectrum in the Orbitrap (300–1800 m/z, 70 000 resolution) with automatic gain control (AGC) target value of 3e6. A data-dependent acquisition method was performed to collect generated MS/MS spectra at 17500 resolution with AGC target of 1e5 and maximum injection time (IT) of 60 ms for top 10 ions observed in each mass spectrum. The isolation window was set at 2 Da width, the dynamic exclusion time was 60 s and the normalized collisional energy (NCE) was set at 30.

Data analysis

The generated MS/MS spectra were searched against the M. smegmatis mc2155 database that has 6578 entries from Uniprot (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/?query=taxonomy:246196) using the SEQUEST searching engine of Proteome Discoverer software (version 1.4). The search criteria were as follows: full tryptic specificity was required; one missed cleavage was allowed; carbamidomethylation (C) and TMT sixplex (K and N-terminal) were set as the fixed modifications; the oxidation (M) was set as the variable modification; precursor ion mass tolerances were set at 10 ppm for all MS acquired in an orbitrap mass analyzer; and the fragment ion mass tolerance was set at 20 mmu for all MS2 spectra acquired. The peptide false discovery rate was calculated using Percolator provided by PD. When the q value was smaller than 1%, the peptide spectrum match was considered to be correct. False discovery was determined based on peptide spectrum match when searched against the reverse, decoy database. Peptides only assigned to a given protein group were considered as unique. The false discovery rate was also set to 0.01 for protein identifications. Relative protein quantification was performed using Proteome Discoverer software (Version 1.4) according to manufacturer’s instructions on the six reporter ion intensities per peptide. Quantitation was carried out only for proteins with two or more unique peptide matches. Protein ratios were calculated as the median of all peptide hits belonging to a protein. Quantitative precision was expressed as protein ratio variability. Differentially expressed proteins were further confirmed by qPCR. Proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD001989.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

The mc2155 and mc2155-Cu strains were cultured in 7H9 medium and collected when OD600 reached 1.0. Total RNA was extracted using RNAprep pure Cell / Bacteria Kit. cDNA was synthesized from 3μg total RNA with the Reverse transcription kit. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with the Roche LightCycler 480II Detection System using SYBR green SuperRealPremixs. RNA polymerase sigma factor rpoD was used as an internal control. Relative expression levels for each reference gene were calculated. The relative expression ratio of a target gene was calculated based on the threshold cycle (Ct) deviation of mc2155-Cu versus mc2155: Ratio = (2-ΔCt mc2155-Cu) / (2-ΔCt mc2155)(ΔCt = Ct target-Ct control;). The primers are listed in S1 Table.

Statistical Method

Statistical analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. Significant differences in the data were determined by Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Selection and Growth of Copper-resistant M. Smegmatis Strain

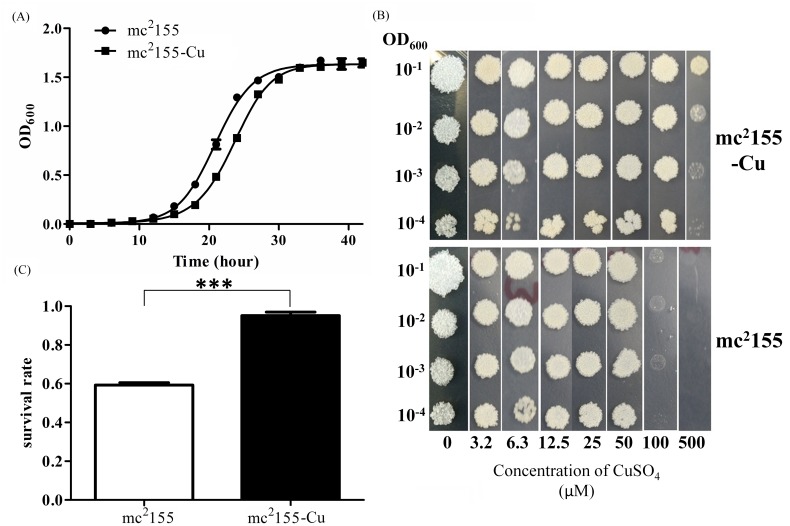

Prior to the selection of CuSO4–resistant strain, the MIC to CuSO4 was determined to be about100 μM in wild type mc2155. To establish a CuSO4 resistant strain, mc2155 was first treated with 50 μM CuSO4 and grew into the log phase. Then, bacteria were diluted and treated by gradually increasing CuSO4 concentrations. After several rounds of selection, the final concentration of CuSO4 reached to 300 μM. To ensure that CuSO4-resistant phenotype was stable, bacteria were sub-cultured for 10 generations without CuSO4 and then streaked on plates to obtain single colonies. A colony that is highly CuSO4 resistant was selected and named mc2155-Cu. The growth rates of mc2155 and mc2155-Cu were monitored at OD600 after initial inoculation. As shown in Fig 1(a), the wild type strain mc2155 started to grow and entered into lag phase after 16 hr post-inoculation, and then reached the late logarithms/stationary phase after 28 hr post-inoculation. In contrast, mc2155-Cu began to grow entered into lag phase after 18 hr and reached the late logarithms/stationary phase after 30 hr post-inoculation. The two hour delay suggested that mc2155-Cu grows slower than mc2155. The growth of mc2155 and mc2155-Cu in the presence of different concentrations of CuSO4 was displayed in Fig 1(b), showing that mc2155-Cu was able to grow in 500 μM CuSO4 while mc2155 only grew when the concentration of CuSO4 was below 100 μM. Based on these results, the MIC of mc2155-Cu to CuSO4 was estimated to be 500 μM, while that of mc2155 was 100 μM. Similarly, MICs of mc2155 and mc2155-Cu to INH were measured (Table 1), showing that mc2155-Cu was more resistant to INH than mc2155, but both strains have the similar MICs to Rifampicin. To further confirm that mc2155-Cu was relatively more resistant to INH, we performed INH killing assays and found that the survival rate of mc2155-Cu was statistically higher than that of mc2155 in the presence of 0.1 mg/ml INH (Fig 1(c)).

Fig 1. Growth curve and the susceptibility of M. smegmatis to copper and isoniazid.

(a) The growth curve of M. smegmatis mc2155 and the copper resistant strain mc2155-Cu were measured in 7H9 media. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Squares, mc2155-Cu strains; circle, mc2155 strain; (b) The bacterial growth on 7H10 plates for M. smegmatis mc2155 and mc2155-Cu that were treated with CuSO4 at different concentrations for 3 days, respectively. The panels show serial dilution (1:10) of mc2155 and mc2155-Cu. Diluted M. smegmatis cultures were spotted onto solid 7H10 media in the presence of CuSO4 ranged from 0 to 500 μM. Images were taken after 3 days incubation at 37°C. Images stand for 3 independent experiments.; and (c) The bacterial survival rate for M. smegmatis mc2155 and mc2155-Cu that were treated with 0.1 mg/ml isoniazid.***p<0.001; n = 3.

Table 1. The MIC of copper, isoniazid and rifampicin in M. smegmatis mc2155 and the copper resistant strain.

| Strain | Copper | Isoniazide | Rifampicin |

|---|---|---|---|

| mc2155 | 100 μM | 15 ug/ml | 10 ug/ml |

| mc2155-Cu | 500 μM | 25 ug/ml | 10 ug/ml |

Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of mc2155-Cu and mc2155

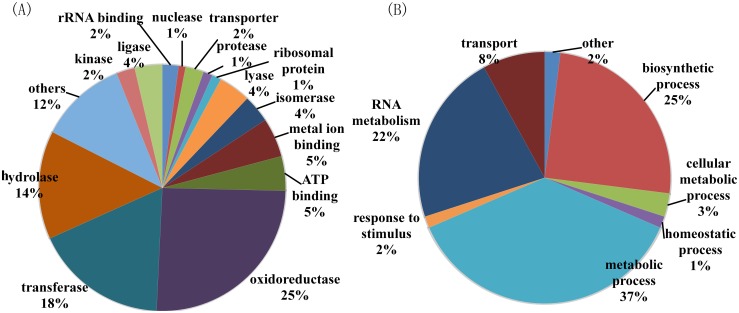

To further characterize changes in bacterial proteome, proteomic analysis was used to find differentially expressed proteins between mc2155 and mc2155-Cu. An equal amount of proteins from mc2155 and mc2155-Cu cells were in-solution digested and labeled with TMT reagents. The generated tryptic peptides were fractionated using off-line HPLC and each fraction were further analyzed by nano-LC-MS/MS. Differentially expressed proteins were identified and quantified using TMT-based quantitation. We identified 2799 proteins in two repeated experiments and the false-positive rate was estimated to be less than 1%. Based on reporter ion ratios (>1.5 or <0.7), 345 proteins were found to be differentially expressed between mc2155 and mc2155-Cu, in which 283 proteins were down-regulated and 62 were up-regulated (S2 and S3 Tables). In order to understand the biological relevance of the identified proteins, the Gene Ontology (GO) was used to cluster the differentially expressed proteins according to their molecular functions and biological processes. The annotations of gene lists are summarized via a pie plot based on the functional classification from Uniprot as shown in Fig 2(a). About 25% of all differentially expressed proteins are oxidoreductases, 18% are transferases, and 14% are hydrolases, indicating that copper ions induce a significant change in cellular redox processes. Three hundred and forty five proteins participated in a variety of cellular processes including metabolic process, biosynthetic process, RNA metabolism, and transport (Fig 2(b)). It is worth mentioning that 15 out of 16 transporter proteins are downregulated and copper-translocating P-type ATPase is the only protein upregulated. All differentially expressed proteins are also classified based on KEGG pathway analysis, indicating that 231 proteins are associated with metabolism and half of those are enzymes in carbohydrate metabolism and amino acid metabolism (S1 Fig). We also noticed that glutamate associated proteins were down-regulated in mc2155-Cu including Glutamate binding protein, Glutamate dehydrogenase, Glutamate-ammonia-ligase adenylyltransferase, Glutamate—tRNA ligase, Glutamine synthetase 1, and Glutamyl-tRNA reductase.

Fig 2. Gene ontology analysis of 345 differentially expressed proteins between M. smegmatis mc2155 and the copper resistant strain.

(A) Classification based on protein functions; (B) classification based on the proteins-associated biological processes.

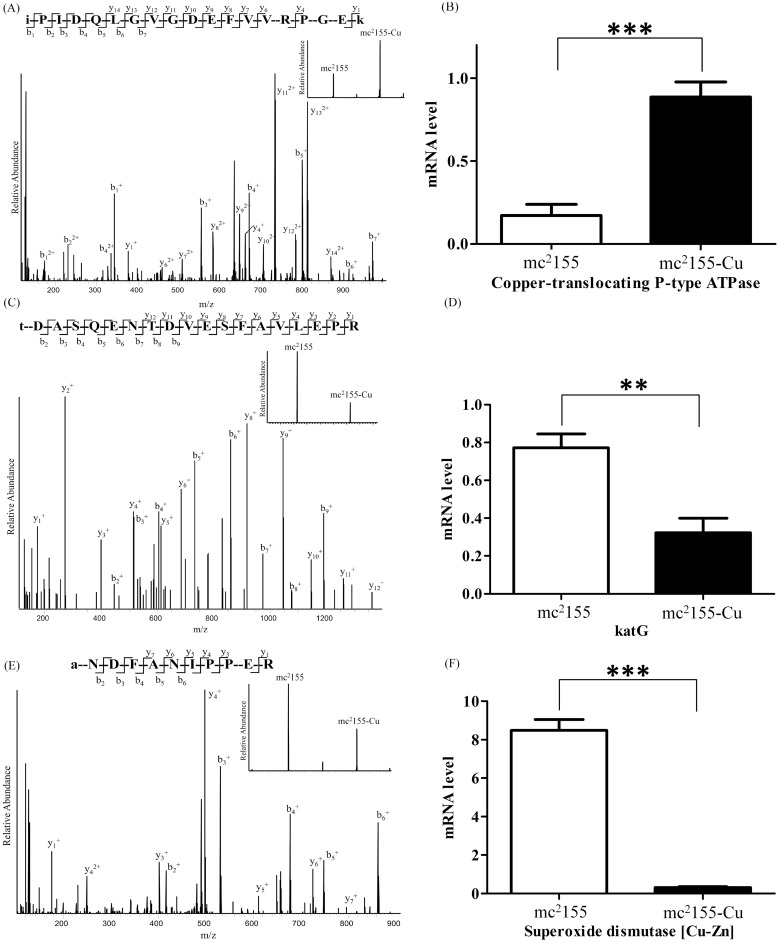

Verification of Differentially Expressed Proteins by qPCR

Among the differentially expressed proteins between mc2155 and mc2155-Cu strains, copper-translocating P-type ATPase, Catalase-peroxidase 2 (katG2) and superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] are directly associated with copper and INH resistance and cellular redox state. To confirm the results of quantitative proteomic analysis, we first quantified the change of mRNA of these three genes (Fig 3). Quantitative proteomics showed that KatG2 was down-regulated in mc2155-Cu (Fig 3(c)) and its mRNA level was also down-regulated by qPCR analysis (Fig 3(d)). The mRNA expressions for copper-translocating P-type ATPase and superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] were up-regulated in mc2155-Cu, which were consistent with changes in protein expressions (Fig 3(a) and 3(b)). As shown in Fig 3(b), the mRNA expression of copper-translocating P-type ATPase in mc2155-Cu is about 4-fold higher than that in mc2155, while the ratio of the protein expression is about 3 in mc2155-Cu (Fig 3(b)) as compared to mc2155. We also carried out qPCR analysis on other proteins including ABC transporter permease/ATP-binding protein, LprG protein, Immunogenic protein MPB64/MPT64, PorinMspA, Proline-rich 28 kDa antigen, Pup-protein ligase, Rv1174c, Transcriptional repressor, CopY family protein and Ribosome binding factor A (S2 Fig). The mRNA levels of all these proteins except Ribosome binding factor A are down-regulated in mc2155-Cu strain, in consistent with the quantitative proteomic results.

Fig 3. Confirmation of differentially expressed proteins in mc2155 and mc2155-Cu by quantitative proteomics and qPCR analysis of mRNA expression of copper-translocating P-type ATPase, katG and superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn].

(a) The MS/MS spectrum of a TMT-labeled peptide from copper-translocating P-type ATPase. The peptide sequence is iPIDQLGVGDEFVVRPGEk. The insert shows intensities of the reported ions at m/z130.141 (mc2155) and m/z 131.138 (mc2155-Cu); (b) the mRNA expression of copper-translocating P-type ATPase; (c) The MS/MS spectrum of a TMT-labeled peptide from katG2. The peptide sequence is tDASQENTDVESFAVLEPR. The insert shows intensities of the reported ions at m/z130.141 (mc2155) and m/z 131.138 (mc2155-Cu); (d) the mRNA expression of katG2; (e) The MS/MS spectrum of a TMT-labeled peptide from superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn]. The peptide sequence is aNDFANIPPER. The insert shows intensities of the reported ions at m/z130.141 (mc2155) and m/z131.138 (mc2155-Cu); (f) the mRNA expression of superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn]. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; n = 3.

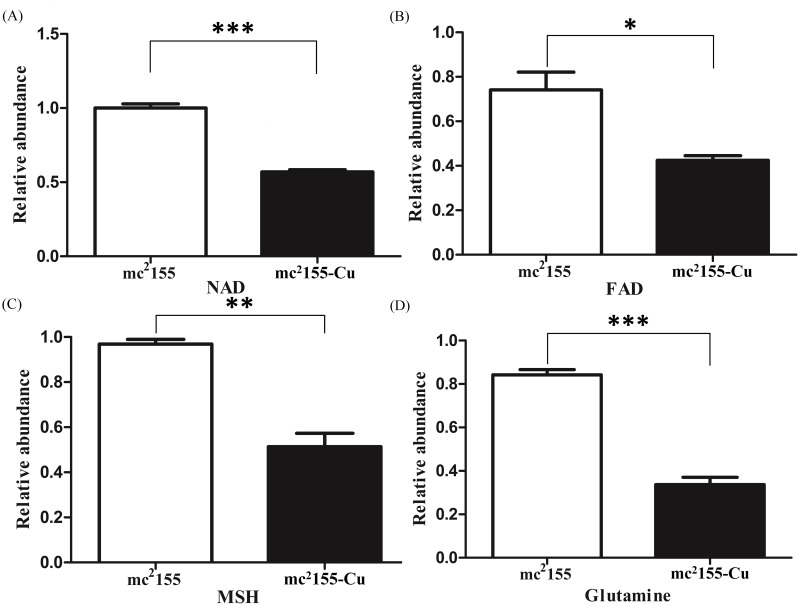

Identification of CuSO4 mediated changes in cell metabolism

Furthermore, we compared the difference in metabolites between mc2155-Cu and mc2155. Metabolites from mycobacteria were extracted with a cold mixing solvent that contained H2O, acetonitrile, and methanol (2:4:4). Using LC-MS/MS analysis, relative levels of NAD, FAD, mycothiol (MSH) and glutamine were determined, showing concentrations of these metabolites were lower in mc2155-Cu than those in mc2155 (Fig 4). The level of glutamine in mc2155-Cu is a third of that in mc2155, while levels of other three metabolites were decreased by half in mc2155-Cu.

Fig 4. Intracellular concentrations of NAD, FAD, MSH, and glutamine levels in mc2155 and mc2155-Cu.

Relative levels of NAD, FAD, mycothiol (MSH) and glutamine were determined by LC-MS/MS analysis. (a) NAD, (b) FAD, (c) mycothiol (MSH) and (d) glutamine. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001;n = 3.

Discussion

Copper ions acting as a co-factor for enzymes in electron transfer reactions are essential for the survival of organisms from bacteria to mammals while excess copper ions are toxic to cells. Studies showed that host cells used copper ions as a component of the immune system to eliminate intracellular bacteria. As the most successful intracellular pathogen, M. tuberculosis has evolved many strategies to survive and persist in phagosomes of macrophages, including detoxification strategies to scavenge copper ions [14–21]. To understand effects of copper ions on proteome and metabolome of mycobacteria, we established a copper-resistant strain of M. smegmatis in the present study, which had a 5-fold higher MIC of copper ions than the wild type mc2155 does (Table 1). The copper-resistant strain grew slower and exhibited the higher resistance to INH as compared to mc2155 (Fig 1).

Quantitative proteomics showed that 345 proteins out of 2799 identified proteins were differentially expressed between mc2155 and mc2155-Cu, in which 283 proteins were down-regulated. By GO analysis, it was found that the most differentially expressed proteins were oxidoreductases, suggesting copper ions mainly induced changes in cellular redox processes. NAD and FAD are cofactors of oxidoreductases including key metabolic enzymes such as glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase [22]. Decreases in NAD and FAD levels in mc2155-Cu can down-regulate activities of glycolytic enzymes, resulting in a decrease in growth rate as compared to mc2155. Out of 345 differentially expressed proteins, 231 proteins are associated with cell metabolism and 114 proteins are enzymes in amino acid metabolism and carbohydrate metabolism. Most proteins in amino acid biosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism are down-regulated, suggesting the copper-resistant bacteria are metabolic inactive as compared to mc2155 bacteria.

Previous studies showed that the up-regulation of CptV gene was a major factor to export copper ions from the cell. In this study, both protein and mRNA expressions of copper-translocating P-type ATPase was upregulated in mc2155-Cu, while the other ABC transporters including ABC Fe3+-siderophores transporter, permease/ATP-binding protein, and ABC CydDC cysteine exporter were down-regulated. The copper-translocating P-type ATPase of M. smegmatis has a high sequence similarity to CptV and CptA genes in M. tuberculosis. In M. tuberculosis, treatment by excess copper ions induced up-regulation of CptV and other transporters including permease and sulfate transporter [23], suggesting that different mycobacterial species may have different responses to copper ion-induced stress, but up-regulation of copper-translocating P-type ATPase is a general mechanism responsible for copper resistance in mycobacteria and other bacterial species [22, 24–26].

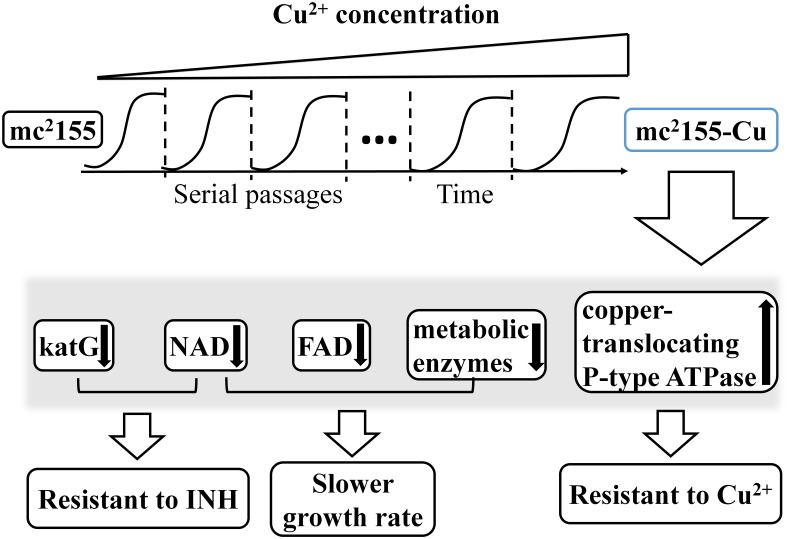

In accompanying to copper resistance, mc2155-Cu also acquired the higher resistance to INH than mc2155 strain as determined by bacterial growth rates and survival rates in the presence of 0.1 mg/ml INH (Fig 1). INH is the first-line medication in prevention and treatment of TB [27]. As a prodrug, INH needs to be activated by KatG to execute its antibiotic function. KatG is a bifunctional enzyme with both catalase and peroxidase activity and catalyzes the coupling of INH with NAD+ to form the isonicotinic acyl-NAD complex, which binds to the enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase to inhibit the synthesis of mycolic acid required for the mycobacterial cell wall. In the present study, quantitative proteomic analysis showed that the expression level of KatG was down-regulated in mc2155-Cu as compared to mc2155 (S3 Table and Fig 3). Down-regulation of KatG expression as well as a decrease in cellular NAD level results in the higher resistance to INH in mc2155-Cu. On the other hand, no difference in resistance to rifampicin was found between mc2155-Cu and mc2155. Rifampicin inhibits bacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerase to prevent RNA synthesis [28] and is not associated with the cellular redox processes. Taken together, our results suggest that co-evolution of copper ion and INH resistance is oxidative stress driven process, as schematically represented in Fig 5. M. tuberculosis lives and replicates in the host cells. To adopt the hostile environment, intracellular M. tuberculosis changes its proteome in order to resist stresses including copper ions. Our results suggest that the long lived M. tuberculosis is resistant to INH and the copper resistant M. smegmatis is a useful model for finding an effective drug candidate to treat dormant tuberculosis.

Fig 5. Schematic representation of co-evolution of Copper and INH Resistance in M. smegmatis.

Copper treatment induces the up-regulation of copper translocating P-type ATPase for enhancing bacterial resistance to copper and the down regulation of katG and NAD for increasing the bacterial resistance to INH.

Conclusions

In summary, we developed a copper resistant strain of M. Smegmatis mc2155-Cu, which has a 5 fold higher resistance to copper ions than mc2155. Decreases in NAD and glutamine levels and down-regulation of oxidoreductases in mc2155-Cu contribute to its slow growth rate as compared to mc2155. In consistent with the earlier reports, up-regulation of copper-translocating P-type ATPase in mc2155-Cu was observed by quantitative proteomics and qPCR, suggesting that this protein plays a crucial role in copper resistance by exporting intracellular copper ions out. More importantly, the down-regulation of KatG was identified in proteomics that contributes to the high resistance to INH in mc2155-Cu strain, indicating the co-evolution of copper and INH resistance. Results presented herein are useful resources to further our understanding of the multifactorial mechanisms of copper resistance in mycobacteria.

Supporting Information

(TIFF)

Confirmation of differentially expressed proteins in mc2155 and mc2155-Cu by qPCR analysis of mRNA expression of (a) ABC transporter permease/ATP-binding protein, (b) LprG protein, (c) Immunogenic protein MPB64/MPT64, (d) PorinMspA, (e) Proline-rich 28 kDa antigen, (f) Pup-protein ligase, (g) Rv1174c, (h) Transcriptional repressor, CopY family protein and (i) Ribosome binding factor A. **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; n = 3.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Protein Chemistry Facility at the Center for Biomedical Analysis of Tsinghua University for sample analysis. We thank Haiping Tang for valuable discussions.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish and preparation of the manuscript of this work were supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) 31270871 (H.T.D), Ministry Of Education And Culture (MOEC) 2012Z02293 (H.T.D), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) 31270178 (K.M).

References

- 1.WHO, Multidrug and extensively drug-resistant TB (M/XDR-TB): 2010 global report on surveillance and response. WHO/HTM/TB/2010.3.

- 2. Tufariello J. M.; Chan J.; Flynn J. L. Latent tuberculosis: mechanisms of host and bacillus that contribute to persistent infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2003, 3 (9), 578–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gengenbacher M.; Kaufmann S. H. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: success through dormancy. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2012, 36 (3), 514–32. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00331.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gupta A.; Kaul A.; Tsolaki A. G.; Kishore U.; Bhakta S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: immune evasion, latency and reactivation. Immunobiology 2012, 217 (3), 363–74. 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nathan C.; Shiloh M. U. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97 (16), 8841–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herbst S.; Schaible U. E.; Schneider B. E. Interferon gamma activated macrophages kill mycobacteria by nitric oxide induced apoptosis. PLoS One 2011, 6 (5), e19105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neyrolles O.; Mintz E.; Catty P. Zinc and copper toxicity in host defense against pathogens: Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a model example of an emerging paradigm. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2013, 3, 89 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Samanovic M. I.; Ding C.; Thiele D. J.; Darwin K.H. Copper in microbial pathogenesis: meddling with the metal. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11 (2), 106–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rowland J. L.; Niederweis M. Resistance mechanisms of Mycobacterium tuberculosis against phagosomal copper overload. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2012, 92 (3), 202–10. 10.1016/j.tube.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Piddington D. L.; Fang F. C.; Laessig T.; Cooper A. M.; Orme I. M.; Buchmeier N. A. Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis contributes to survival in activated macrophages that are generating an oxidative burst. Infection and Immunity 2001, 69 (8), 4980–4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hodgkinson V.; Petris M. J. Copper homeostasis at the host-pathogen interface. J Biol Chem 2012, 287 (17), 13549–55. 10.1074/jbc.R111.316406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. White C.; Lee J.; Kambe T.; Petris M. J. A role for the ATP7A copper-transporting ATPase in macrophage bactericidal activity. J Biol Chem 2009, 284 (49), 33949–56. 10.1074/jbc.M109.070201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wagner D.; Maser J.; Lai B.; Cai Z.; Barry C. E. 3rd; Honer Zu Bentrup K., et al. Elemental analysis of Mycobacterium avium-, Mycobacterium tuberculosis-, and Mycobacterium smegmatis-containing phagosomes indicates pathogen-induced microenvironments within the host cell's endosomal system. J Immunol 2005, 174 (3), 1491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wolschendorf F.; Ackart D.; Shrestha T. B.; Hascall-Dove L.; Nolan S.; Laichhane G., et al. Copper resistance is essential for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108 (4), 1621–6. 10.1073/pnas.1009261108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Armstrong J. A.; Hart P. D. Response of cultured macrophages to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with observations on fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. J Exp Med 1971, 134 (3 Pt 1), 713–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown C. A.; Draper P.; Hart P. D. Mycobacteria and lysosomes: a paradox. Nature 1969, 221 (5181), 658–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shi X.; Festa R. A.; Ioerger T. R.; Butler-Wu S.; Sacchettini J. C.; Darwin K. H, et al. The copper-responsive RicR regulon contributes to Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. MBio 2014, 5 (1), e00876–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ward S. K.; Abomoelak B.; Hoye E. A.; Steomnerg H.; Talaat A. M. CtpV: a putative copper exporter required for full virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 2010, 77 (5), 1096–110. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07273.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu T.; Ramesh A.; Ma Z.; Ward S. K.; Zhang L.; George G. N., et al. CsoR is a novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis copper-sensing transcriptional regulator. Nat Chem Biol 2007, 3 (1), 60–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gold B.; Deng H.; Bryk R.; Vargas D.; Eliezer D.; Roberts J., et al. Identification of a copper-binding metallothionein in pathogenic mycobacteria. Nat Chem Biol 2008, 4 (10), 609–16. 10.1038/nchembio.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Festa R. A.; Jones M. B.; Butler-Wu S.; Sinsimer D.; Gerads R.; Bishai W. R., et al. A novel copper-responsive regulon in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 2011, 79 (1), 133–48. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07431.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sitthisak S.; Knutsson L.; Webb J. W.; Jayaswal R. K. Molecular characterization of the copper transport system in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol-Sgm 2007, 153, 4274–4283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ward S. K.; Hoye E. A.; Talaat A. M. The global responses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to physiological levels of copper. J Bacteriol 2008, 190 (8), 2939–46. 10.1128/JB.01847-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rensing C.; Fan B.; Sharma R., Mitra B.; Rosen B. P. CopA: An Escherichia coli Cu(I)-translocating P-type ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97 (2), 652–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mattle D.; Sitsel O.; Autzen H. E.; Meloni G.; Gourdon P.; Nissen P. On allosteric modulation of P-type Cu(+)-ATPases. J Mol Biol 2013, 425 (13), 2299–308. 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Andersson M.; Mattle D.; Sitsel O.; Klymchuk T.; Nielsen A. M.; Moller L. B., et al. Copper-transporting P-type ATPases use a unique ion-release pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2014, 21 (1), 43–8. 10.1038/nsmb.2721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Timmins G. S.; Deretic V. Mechanisms of action of isoniazid. Mol Microbiol 2006, 62 (5), 1220–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Calvori C.; Frontali L.; Leoni L.; Tecce G. Effect of Rifamycin on Protein Synthesis. Nature 1965, 207 (4995), 417–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIFF)

Confirmation of differentially expressed proteins in mc2155 and mc2155-Cu by qPCR analysis of mRNA expression of (a) ABC transporter permease/ATP-binding protein, (b) LprG protein, (c) Immunogenic protein MPB64/MPT64, (d) PorinMspA, (e) Proline-rich 28 kDa antigen, (f) Pup-protein ligase, (g) Rv1174c, (h) Transcriptional repressor, CopY family protein and (i) Ribosome binding factor A. **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001; n = 3.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.