Abstract

Objectives

The study aims at investigating the influence of several factors on the probability of receiving one of the two tiotropium formulations (Respimat or Handihaler).

Design

Drug utilisation study.

Setting

All residents in the Region Umbria, Italy, aged ≥45 years, who received prescriptions of tiotropium during 2011–2012.

Participants

Two groups of patients were studied: (1) incident users of the two tiotropium formulations (ie, without tiotropium prescriptions in the previous 6 months); (2) switchers from Handihaler to Respimat. Users of the two formulations were compared with regard to baseline characteristics and medical history. The adjusted OR of receiving Respimat was estimated for several factors.

Results

Incident users of the two formulations (4390 participants) had similar characteristics. They were older and with more comorbidities than patients included in randomised control trials (RCTs). Among prevalent users of Handihaler, the probability of switching to Respimat was greater in patients with severe respiratory disease (users of ≥4 respiratory drugs: adjusted OR=4.62; 95% CI 2.46 to 8.69) and among β-blocker users (adjusted OR=1.76; 95% CI 1.13 to 2.75). Age above 75 years and lipid-lowering drug use reduced the probability of switching. A positive association was also found between neurological conditions and the use of Respimat.

Conclusions

When starting tiotropium treatment, the choice between the two formulations is weakly affected by comorbidities and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity. Instead, these characteristics influence the likelihood of switching from Handihaler to Respimat. Since tiotropium users in clinical practice are more severe than those included in RCTs, further aetiological studies are needed to compare the safety profile of the two formulations in routine care.

Keywords: RESPIRATORY MEDICINE (see Thoracic Medicine), CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Clinical trial findings and observational study results were contrasting with regard to the increased risk of death associated with tiotropium Respimat. Limitations of the two study designs were hypothesised to be responsible for these differences. We still do not know whether the results of the observational study are attributable to the channelling bias or to a patient population which is different from the one enrolled in the trial.

The influence of the baseline characteristics and medical history of patients on the prescription of the two available tiotropium formulations (Handihaler or Respimat) has been identified.

When starting tiotropium treatment, the choice between the two formulations is weakly affected by comorbidities and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity. Instead, these characteristics influence the likelihood of switching from Handihaler to Respimat. Tiotropium users in clinical practice are more severe than those included in randomised control trials.

The accumulating evidence demonstrates that knowledge of the baseline patient's characteristics is essential to assure an appropriate and safe use of tiotropium formulations.

Introduction

An important therapeutic option for the management of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is represented by tiotropium bromide, a long-acting anticholinergic agent widely used in Italy.1 2 Tiotropium was introduced in the second half of 2004 as an inhalation powder administered through the Handihaler device (Handihaler in the following).3 In the first half of 2011, a new tiotropium formulation, a solution for inhalation administered by the Respimat device (Respimat in the following), was also introduced in Italy;4 Respimat was developed to increase the ease and effective use of the drug by a fragile population (eg, participants with reduced inspiratory capacity or with difficulties in manual coordination).5–9

Recent meta-analyses based on clinical trials data questioned the safety profile of Respimat revealing a statistically significant increase in the risk of overall mortality and cardiovascular death associated with its use.10–12 To address the safety concerns, the company compared the two formulations in a randomised head-to-head study demonstrating no risk difference on a ‘hard’ outcome such as mortality.13

Although the scientific community positively acknowledged the trial results, unanswered research questions were still present, mainly pertaining the highly selected patient population enrolled in the trial.14–20 Concerns on the generalisability of trial results were also reinforced following the conclusion of an observational study carried out in general practice in the Netherlands (including patients with cardiovascular comorbidities), which showed diametrically opposite results to those of the clinical trial. The study findings suggested an increased risk of death from all causes and of cardiovascular death with Respimat, especially among patients with concomitant cardiovascular diseases.21 The channelling bias, that is, that more severe patients (for COPD or other comorbidities) received a prescription of Respimat rather than Handihaler, was considered to explain such divergent results from the trial.

However, it is still unknown if the discrepant results of the randomised control trial (RCT) and the observational study are attributable to the presence of the channelling bias or to the underlying differences in the patient population; therefore, the full knowledge of patient's characteristics at baseline is essential. The full pattern of predictors for Respimat prescriptions, as well as the magnitude of the possible channelling bias in different settings should be assessed.

For these reasons, we conducted a drug utilisation study aimed at investigating the influence of several factors on the probability of receiving one of the two tiotropium formulations and at verifying the existence of the channelling effect both in incident users and in patients switching from the Handihaler to the Respimat formulation.

Methods

The study was conducted within the population of the Umbria Region (about 900 000 inhabitants) during the period 1 January 2011–31 December 2012. All residents are covered by the Italian National Health Service (NHS), which provides comprehensive hospital and outpatient care. The consumption of antiasthmatic drugs in the Umbria Region is representative of the whole Country.22

Study population

Outpatients receive prescriptions from general practitioners and obtain medicines covered by the NHS from local community pharmacies or, in some cases, directly from local health units. For each prescription, the following information is available at the regional level: patient code (which is anonymised before any subsequent use), date of prescription, drug substance, marketing authorisation code (indicating the specific tiotropium formulation, ie, Handihaler or Respimat), number of packages. Prescription data were linked through the anonymised code to the regional database of enrollees to retrieve age and gender. No information is available on prescriptions issued during the hospitalisation and on medicines use in nursing homes.

The eligible population included participants aged ≥45 years, resident in the Region, with at least one prescription of tiotropium (Handihaler or Respimat) during the study period. Participants who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study cohort.

Two different populations of tiotropium users were defined to answer the study objectives

Incidents users were participants receiving the first prescription of tiotropium (Handihaler or Respimat) between 1 July 2011 and 31 December 2012 (without prescriptions of tiotropium in the previous 6 months).

Switchers from Handihaler to Respimat were all participants who were receiving Handihaler in the time frame 1 January 2011–30 September 2012, undergoing a change in the formulation (thus switching to Respimat) within 60 days following a prescription of Handihaler. Switchers were then compared with a control population of exclusive Handihaler users (who did not receive a prescription of Respimat during the period, ie, non-switcher). Each participant who received the first prescription of Respimat at a certain date (index date) was matched with a control, defined as a Handihaler user who received at least two prescriptions of Handihaler within 60 days one from the other in the time frame included between the previous 2 months and the subsequent 2 months after the index date. A random procedure was used to select the control participant when more than one potentially eligible patient was available.

Definition of therapeutic categories

All drugs were identified through the international Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system, ATC code. Tiotropium users were identified through the prescription of tiotropium (ATC R03BB04) and then characterised as Handihaler or Respimat according to the unique marketing authorisation code.

All prescriptions (different from tiotropium) issued during the 6-month period before the first prescription of tiotropium were retrieved and classified according to the prespecified therapeutic subgroups (see online supplementary table S1) in order to identify the main comorbidities (eg, users of antiarrhythmics, antiparkinsons). In addition, the use of respiratory medications before starting tiotropium was resorted to in order to characterise the severity of the respiratory disease (see online supplementary table S1).

Statistical analysis

To identify the determinants of the selection between the two formulations in new users, we compared incident users of Respimat and Handihaler with regard to age, gender, severity of respiratory disease and comorbidities.

To investigate the determinants of switching, we compared switchers with a control population of non-switchers, that is, exclusive Handihaler users. Each participant who switched to Respimat was matched at the date of switching (index date) with one control patient. The crude OR for each factor and related 95% CI were calculated using univariate logistic regression. All factors with at least a 10% significance (p≤0.10) in the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate stepwise logistic model to select those relevant for the risk adjustment. An adjusted OR was estimated for each factor. In the analysis of incident users, the following variables were considered as confounders: age, respiratory medications, antibiotics, β-blockers, antidiabetics and antiparkinsons. In the switchers analysis, we considered the effect of age, respiratory medications, pain medications, antibiotics, lipid-lowering agents, antiglaucoma medications and β-blockers.

Results

Individual characteristics predicting the incident prescription of Respimat

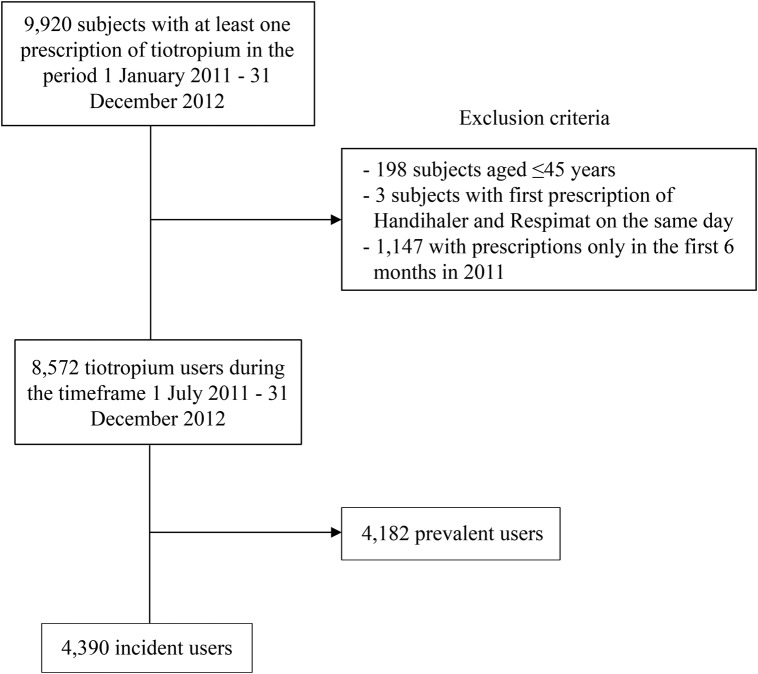

Overall, 9920 particiapants with at least one prescription of tiotropium were identified from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2012 (figure 1). Applying the inclusion criteria, 4390 patients were considered incident users of tiotropium.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for incident users of tiotropium.

The characteristics of incident users of the two formulations (Handihaler or Respimat) are reported in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and medical history of incident users of Handihaler or Respimat formulation and of factors associated with Respimat prescription

| Characteristics | Handihaler | Respimat | Crude OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 3492 | 898 | ||||||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 74 (10) | 73 (10) | ||||||

| N | Per cent | N | Per cent | |||||

| Age class (years) | ||||||||

| 45–64 | 641 | 18.4 | 205 | 22.8 | ref | ref | ||

| 65–74 | 1019 | 29.2 | 267 | 29.7 | 0.82 | 0.67 to 1.01 | 0.80 | 0.65 to 0.99 |

| ≥75 | 1832 | 52.5 | 426 | 47.4 | 0.73 | 0.60 to 0.88 | 0.70 | 0.58 to 0.85 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1976 | 56.6 | 512 | 57.0 | 1.02 | 0.88 to 1.18 | 1.03 | 0.89 to 1.20 |

| Female | 1516 | 43.4 | 386 | 43.0 | ref | ref | ||

| Severity of respiratory disease | ||||||||

| No respiratory drugs | 1322 | 37.9 | 316 | 35.2 | ref | ref | ||

| 1 class of respiratory drugs | 918 | 26.3 | 219 | 24.4 | 1.00 | 0.82 to 1.21 | 0.97 | 0.80 to 1.18 |

| 2 classes of respiratory drugs | 567 | 16.2 | 155 | 17.3 | 1.14 | 0.92 to 1.42 | 1.11 | 0.89 to 1.38 |

| 3 classes of respiratory drugs | 357 | 10.2 | 95 | 10.6 | 1.11 | 0.86 to 1.44 | 1.08 | 0.82 to 1.40 |

| ≥4 classes of respiratory drugs | 328 | 9.4 | 113 | 12.6 | 1.44 | 1.13 to 1.84 | 1.41 | 1.09 to 1.83 |

| Previous drug use (tracer of comorbidity) | ||||||||

| Antiarrhythmics | 225 | 6.4 | 60 | 6.7 | 1.04 | 0.77 to 1.40 | 1.05 | 0.78 to 1.42 |

| β-Blockers | 791 | 22.7 | 238 | 26.5 | 1.23 | 1.04 to 1.46 | 1.29 | 1.08 to 1.52 |

| Other cardiovascular drugs | 2623 | 75.1 | 668 | 74.4 | 0.96 | 0.81 to 1.14 | 1.00 | 0.83 to 1.20 |

| Antibiotics | 2165 | 62.0 | 606 | 67.5 | 1.27 | 1.09 to 1.48 | 1.23 | 1.04 to 1.45 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | 964 | 27.6 | 254 | 28.3 | 1.03 | 0.88 to 1.22 | 1.06 | 0.89 to 1.26 |

| Pain medications (opioids) | 306 | 8.8 | 79 | 8.8 | 1.00 | 0.78 to 1.30 | 0.99 | 0.76 to 1.28 |

| Antiglaucoma agents | 188 | 5.4 | 56 | 6.2 | 1.17 | 0.86 to 1.59 | 1.25 | 0.92 to 1.71 |

| Antiplatelet/anticoagulant agents | 1729 | 49.5 | 449 | 50.0 | 1.02 | 0.88 to 1.18 | 1.08 | 0.92 to 1.27 |

| Antidiabetics | 644 | 18.7 | 137 | 15.3 | 0.80 | 0.65 to 0.97 | 0.76 | 0.62 to 0.94 |

| Antipsychotics | 87 | 2.5 | 31 | 3.5 | 1.40 | 0.92 to 2.12 | 1.32 | 0.87 to 2.02 |

| Antiparkinsons | 84 | 2.4 | 32 | 3.6 | 1.50 | 0.99 to 2.69 | 1.65 | 1.08 to 2.51 |

| Antidepressives | 672 | 19.2 | 158 | 17.6 | 0.90 | 0.74 to 1.09 | 0.86 | 0.71 to 1.05 |

| Antiepileptics | 199 | 5.7 | 62 | 6.9 | 1.23 | 0.91 to 1.65 | 1.19 | 0.88 to 1.60 |

| Antacids | 1862 | 53.3 | 463 | 51.6 | 0.93 | 0.81 to 1.08 | 0.89 | 0.77 to 1.04 |

| NSAIDs | 900 | 25.8 | 225 | 25.1 | 0.96 | 0.81 to 1.14 | 0.93 | 0.78 to 1.10 |

| Osteoporosis medications | 260 | 7.4 | 63 | 7.0 | 0.94 | 0.71 to 1.25 | 0.92 | 0.69 to 1.23 |

NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The majority of incident users (79.5%) started with Handihaler. Overall, the baseline characteristics of incident users were similar for both formulations. However, increasing age (≥75 years) negatively affected the probability of receiving a prescription for Respimat (adjusted OR=0.70, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.85). The severity of respiratory disease appeared to have a limited role in channelling the prescription to Respimat, since a statistically significant association was found only in patients with more severe respiratory disease, that is, those using at least four different classes of respiratory medications before starting tiotropium (adjusted OR=1.41, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.83).

Most of the comorbidities were not associated with the prescription of Respimat (most of the OR estimates were close to unity). However, individuals who used β-blockers had a higher probability of receiving Respimat (adjusted OR=1.29, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.52). A positive association with Respimat prescription was found in participants with underlying severe neurological conditions, that is, users of antiparkinson (adjusted OR=1.65, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.51) and, even though not statistically significant, with antipsychotics (adjusted OR=1.32, 95% CI 0.87 to 2.02).

Individual characteristics predicting the switch from Handihaler to Respimat

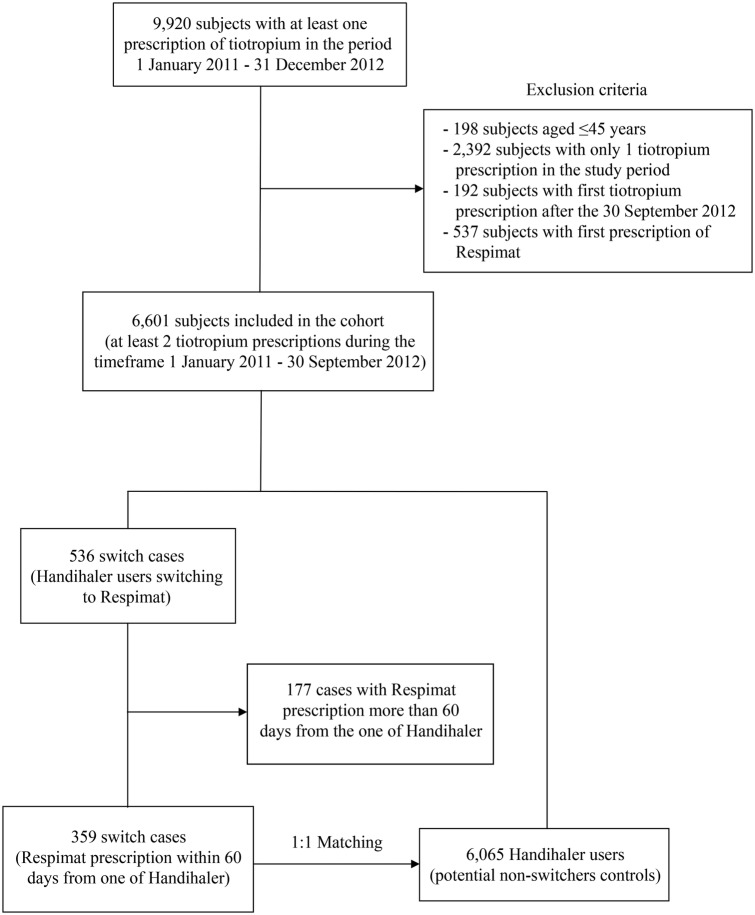

Starting from the initial cohort of 9920 patients with prescriptions of tiotropium, 359 users of Handihaler who switched to Respimat were identified (figure 2). All switchers were matched 1:1 (through the index date of the case) with a control participant.

Figure 2.

Flow chart for switcher/non-switcher participants.

In this case, the differences between the switchers and non-switchers were remarkable (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics and medical history of cases (switchers) and controls (non-switchers) at the time of the switch and identification of factors associated with switching to Respimat

| Characteristics | Cases (switchers) | Controls (non-switchers) | Crude OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 359 | 359 | ||||||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 73 (10) | 76 (10) | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | |||||

| Age class (years) | ||||||||

| 45–64 | 67 | 18.7 | 48 | 13.4 | ref | ref | ||

| 65–74 | 123 | 34.3 | 97 | 27.0 | 0.91 | 0.58 to 1.43 | 0.88 | 0.55 to 1.42 |

| ≥75 | 169 | 47.1 | 214 | 59.6 | 0.57 | 0.37 to 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.33 to 0.81 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 224 | 62.0 | 226 | 63.0 | 1.02 | 0.76 to 1.39 | 1.07 | 0.77 to 1.47 |

| Female | 135 | 38.0 | 133 | 37.0 | ref | ref | ||

| Severity of respiratory disease | ||||||||

| No respiratory drugs | 44 | 12.3 | 75 | 20.9 | ref | ref | ||

| 1 class of respiratory drugs | 115 | 32.0 | 145 | 40.4 | 1.35 | 0.87 to 2.11 | 1.31 | 0.82 to 2.06 |

| 2 classes of respiratory drugs | 78 | 21.7 | 77 | 21.4 | 1.73 | 1.06 to 2.81 | 1.63 | 0.98 to 2.72 |

| 3 classes of respiratory drugs | 47 | 13.1 | 37 | 10.3 | 2.17 | 1.23 to 3.83 | 1.96 | 1.06 to 3.61 |

| ≥4 classes of respiratory drugs | 75 | 20.9 | 25 | 7.0 | 5.11 | 2.85 to 9.19 | 4.62 | 2.46 to 8.69 |

| Previous drug use (tracer of comorbidity) | ||||||||

| Antiarrhythmics | 27 | 7.5 | 21 | 5.8 | 1.31 | 0.73 to 2.26 | 1.53 | 0.82 to 2.85 |

| β-Blockers | 62 | 17.3 | 48 | 13.4 | 1.35 | 0.90 to 2.04 | 1.76 | 1.13 to 2.75 |

| Other cardiovascular drugs | 72 | 20.0 | 65 | 18.1 | 0.88 | 0.61 to 1.28 | 0.92 | 0.61 to 1.39 |

| Antibiotics | 258 | 71.9 | 211 | 58.8 | 1.79 | 1.31 to 2.45 | 1.34 | 0.94 to 1.89 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | 81 | 22.6 | 104 | 29.0 | 0.71 | 0.51 to 1.00 | 0.68 | 0.47 to 0.97 |

| Pain medications (opioids) | 26 | 7.2 | 40 | 11.1 | 0.62 | 0.37 to 1.04 | 0.61 | 0.35 to 1.05 |

| Antiglaucoma agents | 34 | 9.5 | 21 | 5.8 | 1.68 | 0.96 to 2.96 | 1.63 | 0.90 to 2.95 |

| Antiplatelet/anticoagulant agents | 184 | 51.3 | 183 | 51.0 | 1.01 | 0.75 to 1.35 | 1.28 | 0.90 to 1.80 |

| Antidiabetics | 58 | 16.2 | 62 | 17.3 | 0.92 | 0.62 to 1.37 | 0.89 | 0.58 to 1.36 |

| Antipsychotics | 11 | 3.1 | 10 | 2.8 | 1.10 | 0.46 to 2.63 | 1.33 | 0.53 to 3.34 |

| Antiparkinsons | 12 | 3.3 | 9 | 2.5 | 1.34 | 0.56 to 3.23 | 1.60 | 0.63 to 4.08 |

| Antidepressives | 60 | 16.7 | 71 | 19.8 | 0.81 | 0.56 to 1.19 | 0.80 | 0.53 to 1.20 |

| Antiepileptics | 20 | 5.6 | 26 | 7.2 | 0.76 | 0.41 to 1.38 | 0.80 | 0.42 to 1.54 |

| Antacids | 195 | 54.3 | 188 | 52.4 | 1.08 | 0.81 to 1.45 | 1.00 | 0.72 to 1.40 |

| NSAIDs | 89 | 24.8 | 72 | 20.1 | 1.31 | 0.92 to 1.87 | 1.20 | 0.82 to 1.76 |

| Osteoporosis medications | 29 | 8.1 | 29 | 8.1 | 1.00 | 0.59 to 1.71 | 0.96 | 0.55 to 1.68 |

NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Statistical comparisons between cases and controls highlighted the risk factors associated with a higher probability of switching from one formulation (Handihaler) to the other (Respimat).

Age was confirmed to be negatively associated with switching to Respimat, since a lower probability was observed with increasing age, becoming statistically significant in the elderly aged above 75 years (adjusted OR=0.52, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.81).

The higher the number of respiratory drugs used, the higher was the probability of switching to Respimat. Such association became statistically significant for patients taking three classes of respiratory medications in addition to tiotropium (OR=1.96, 95% CI 1.06 to 3.61), with a peak in case of at least four classes of concomitant respiratory medications (adjusted OR=4.62, 95% CI 2.46 to 8.69).

With regard to comorbidities, the use of β-blockers was significantly associated with switching to Respimat (adjusted OR=1.76, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.75), whereas the use of antiarrhythmics showed only a (not significant) trend of an increased probability of switching (adjusted OR=1.53, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.85), although the number of participants included in the analysis was relatively limited. The use of other classes of cardiovascular drugs as well as of antiplatelet/anticoagulant agents had no effect on switching to Respimat. The antiglaucoma drugs, which included β-blockers and parasympathomimetic agents with possible systemic effects antagonising the bronchodilator drugs, were not used frequently (less than 10% of the study population); thus, in this case also, a not significant trend of an increased probability of switching was observed (adjusted OR=1.63, 95% CI 0.90 to 2.95).

The use of antibiotics was not significantly associated with switching (adjusted OR=1.34, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.89). Lipid-lowering agents were found to have a protective role, significantly reducing the probability of changing from Handihaler to Respimat (adjusted OR=0.68, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.97).

Few participants included in the case–control analysis were users of medicine tracers of neurological conditions that cause coordination difficulties, such as antipsychotic and antiparkinson drugs; nevertheless, the trend of risk estimates was similar to that obtained for incident users of Respimat.

Discussion

This study identified important risk factors influencing the prescription of Respimat formulation. The role of these factors appeared to be limited for incident users, while their impact was marked in patients already under treatment with tiotropium Handihaler who switched to Respimat.

In fact, in incident users, the demographic characteristics and medical history (regarding respiratory disease and other comorbidities) were very similar between the two groups using Handihaler or Respimat; a slight effect driving the prescription to Respimat can be appreciated only for patients using β-blockers. The presence of concomitant neurological diseases resulting in a worsening of motor coordination, such as Parkinson disease, directed the prescription to Respimat (a formulation developed to increase the compliance in patients with coordination deficiencies).

The role of risk factors had a greater magnitude in patients treated with Handihaler switching to Respimat. More severe respiratory disease and the use of β-blockers or antiarrhythmic drugs were highly associated with switching from Handihaler to Respimat. On the contrary, younger age and the use of lipid-lowering agents (whose potential protective role in the control of COPD has been recently questioned)23–26 were negatively associated with switching. Positive risk trends guiding towards Respimat were also found for patients using antiglaucoma medications (which can precipitate COPD) as well as for patients with neurological diseases such as Parkinson or psychosis.

The characteristics of patients enrolled in the Umbria Region should be put in the context of the available evidence deriving from the two published studies, that is, the trial from Wise et al,13 and the observational study from Verhamme et al21 (see online supplementary supporting table S2). Overall, incident tiotropium users in the Umbria Region and in the Netherlands were very similar with regard to the male/female ratio, past use of respiratory medications and drugs tracers of comorbidities. Moreover, in the Dutch study, Respimat users had a more severe respiratory disease and more cardiovascular conditions than Handihaler users.

Conversely, many differences cropped up when the patients enrolled in the RCT by Wise et al13 were compared with those from the Netherlands21 or the Umbria Region. The RCT enrolled a more selected population. Patients with unstable heart disease, uncontrolled patients with respiratory disease and patients with conditions that could complicate the participation in the study (eg, tumours, severe neurological disorders) were excluded and the trial population was younger. Even the use of specific classes of respiratory drugs differed: Short-acting β-agonists, long-acting β-agonists and anticholinrgics (ipratropium and oxytropium) were more represented in the trial setting (indicating a population that tolerates such medications). The use of cardiovascular drugs showed different patterns: 14% of patients treated with tiotropium used β-blockers in the RCT, while the figure was 25% in the Umbria population. More than 19% of trial patients used acetylsalicylic acid, while in the Umbria Region a prescription of antiplatelet/anticoagulant agents was found in over 49% of the participants. In the RCT, no information was given with regard to antibiotics or lipid-lowering agents.

Our study confirmed that patients treated in general practice differ from those included in the trials. The differences in patient characteristics highlighted here may contribute to explaining the conflicting results in terms of clinical outcome between the trial by Wise et al13 and the observational study by Verhamme et al.21

Our findings add evidence to identify factors predicting the prescription of Respimat in different settings of tiotropium use, thus responsible for a potential ‘channelling bias’. The differences in the baseline patients characteristics (which were relevant in the case of Handihaler users switching to Respimat) favoured the prescription of Respimat to more severe patients (for respiratory disease and/or specific cardiovascular conditions), who were also those at a higher risk of worse clinical outcome, as suggested by Verhamme et al.21

A ‘channelling bias’ towards Respimat was also highlighted in patients with neurological disorders that can lead to problems with motor coordination.

As for other studies that used prescription databases, a limitation of our analysis is that the identification of incident users and switchers/non-switchers is based on pharmacy records. For instance, prescriptions may lead to misclassification if a drug is dispensed but not used. We did not stratify the factors by different dosage strengths of Respimat. Moreover, the timing of dispensing would affect the identification of incident patients or switchers/non-switchers. We had no information on the actual diagnoses for which the concomitant drugs were used, and the prescription has been interpreted as a proxy indicator for a variety of underlying conditions (see online supplementary table S2).

In conclusion, in patients who started tiotropium for the first time, the choice of the prescriber of one of the two formulations does not seem to be influenced by the knowledge of specific risk factors related to the severity of COPD or the presence of comorbidities. On the contrary, in patients already on treatment with tiotropium Handihaler, the choice of the prescriber to switch to Respimat appears to be influenced by risk factors such as the severity (or the lack of control) of the respiratory disease itself and the presence of conditions requiring β-blockers or antiarrhythmics. The presence of neurological conditions negatively affecting motor coordination directs the prescriber towards Respimat, both for incident patients and for switchers. Tiotropium users in clinical practice are more severe than those included in RCTs; thus, further aetiological studies are needed to compare the safety profile of the two formulations in routine care.

Footnotes

Contributors: MRo, FT and GT conceived the study; RDC, MRa, GT and FT designed the study; RDC, MRa and FT analysed the data; GT and FT wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript. GT will act as the guarantor for the paper. All authors saw, commented on and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding: Only public employees of the National or Regional health authorities were involved in conceiving, planning and conducting the study; partial financial support was received from the Umbria Regional Health Authority. The corresponding author had full access to all study data and approved the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: In Italy, the approval by Ethics Committees was not required for the drug utilisation study. Only anonymised data were used. All authors assure the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors are willing to cooperate in answering further research questions and to participate in future collaborative studies.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of the authors’ institutions.

References

- 1.Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD from the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2013. http://www.goldcopd.org/ (accessed 12 May 2014).

- 2.Da Cas R, Ruggeri P, Rossi M et al. Prescrizione farmaceutica in Umbria. Analisi dei dati relativi al 2011. Rapporti ISTISAN 13/11 Roma: Istituto Superiore di Sanità; 2013:1–133. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spiriva® Summary of Product Characteristics. Banca dati farmaci. Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/pages/home.jsp (accessed 12 May 2014).

- 4.Spiriva® Respimat® Summary of Product Characteristics. Banca dati farmaci. Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/pages/home.jsp (accessed 12 May 2014).

- 5.Anderson P. Use of Respimat Soft Mist inhaler in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2006;1:251–9. 10.2147/copd.2006.1.3.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodder R, Price D. Patient preferences for inhaler devices in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: experience with Respimat Soft Mist inhaler. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2009;4:381–90. 10.2147/COPD.S3391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bateman ED, Tashkin D, Siafakas N et al. A one-year trial of tiotropium Respimat plus usual therapy in COPD patients. Respir Med 2010;104:1460–72. 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bateman E, Singh D, Smith D et al. Efficacy and safety of tiotropium Respimat SMI in COPD in two 1-year randomized studies. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2010;5:197–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1543–54. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S, Loke YK, Enright PI et al. Mortality associated with tiotropium mist inhaler in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ 2011;342:1439–50. 10.1136/bmj.d3215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karner C, Chong J, Poole P. Tiotropium versus placebo for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(7):CD009285 10.1002/14651858.CD009285.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong YH, Lin HH, Shau WY et al. Comparative safety of inhaled medications in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Thorax 2013;68:48–56. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wise RA, Anzueto A, Cotton D et al. Tiotropium Respimat inhaler and the risk of death in COPD. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1491–501. 10.1056/NEJMoa1303342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beasley R, Singh S, Loke YK et al. Call for worldwide withdrawal of tiotropium Respimat mist inhaler. BMJ 2012;345:e7390 10.1136/bmj.e7390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins CR. More than just reassurance on tiotropium safety. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1555–6. 10.1056/NEJMe1310107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bateman ED. Tiotropium Respimat increases the risk of mortality: con. Eur Respir J 2013;42:590–3. 10.1183/09031936.00042213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beasley R. Tiotropium Respimat increases the risk of mortality: pro. Eur Respir J 2013;42:584–9. 10.1183/09031936.00042113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins CR, Beasley R. Tiotropium Respimat increases the risk of mortality. Thorax 2013;68:5–7. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh S, Loke YK, Enright P et al. Pro-arrhythmic and pro-ischaemic effects of inhaled anticholinergic medications. Thorax 2013;68:114–16. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pulmonary-Allergy Drugs Advisory Committee. US Food and Drug Administration. Clinical briefing document, November 19 2009. Overview of the FDA background materials for an efficacy supplement for NDA# 21–395, for the approved product Spiriva HandiHaler (tiotropium bromide inhalation powder), for the reduction in exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). http://www.fda.gov/downloads/advisorycommittees/committeesmeetingmaterials/drugs/pulmonary-allergydrugsadvisorycommittee/ucm190463.pdf (accessed 12 May 2014).

- 21.Verhamme KM, Afonso A, Romio S et al. Use of tiotropium Respimat Soft Mist Inhaler versus HandiHaler and mortality in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2013;42:606–15. 10.1183/09031936.00005813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruppo di lavoro OsMed. L'uso dei farmaci in Italia. Rapporto nazionale anno 2011 Roma: Il Pensiero Scientifico Editore; 2012:1– 335 http://www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/sites/default/files/1_-_rapporto_osmed_2011.pdf (accessed 12 May 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janda S, Park K, FitzGerald JM et al. Statins in COPD: a systematic review. Chest 2009;136:734–43. 10.1378/chest.09-0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lahousse L, Loth DW, Joos GF et al. Statins, systemic inflammation and risk of death in COPD: the Rotterdam study. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2013;26:212–17. 10.1016/j.pupt.2012.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang MT, Lo YW, Tsai CL et al. Statin use and risk of COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization. Am J Med 2013;126:598–606. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Criner GJ, Connett JE, Aaron SD et al. Simvastatin for the prevention of exacerbations in moderate-to-severe COPD. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2201–10. 10.1056/NEJMoa1403086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]