Abstract

Previous twin studies report no heritability of Parkinson disease (PD) based on cross-sectional information. Here, we apply a longitudinal design and re-evaluate cross-sectional data in the population-based Swedish Twin Registry (STR) using clinical as well as hospital discharge and cause of death diagnoses. In the longitudinal analyses (based on 46,436 individuals), we identified 542 twins with PD and 65 twins with parkinsonism. Concordance rates for PD were 11% for monozygotic and 4% for same-sexed dizygotic twin pairs, with a heritability estimate of 34%. Concordance rates for PD or parkinsonism were 13% for monozygotic and 5% for same-sexed dizygotic twin pairs, with a heritability estimate of 40%. In the cross-sectional analyses (based on 49,814 individuals), we identified 287 twins with PD and 79 twins with parkinsonism. Concordance rates for PD were 4% for monozygotic and same-sexed dizygotic twin pairs and zero for opposite-sexed twin pairs. Concordance rates for PD or parkinsonism were somewhat higher but the heritability estimate was non-significant. Our longitudinal analyses demonstrate that PD and parkinsonism are modestly heritable.

Keywords: Parkinson disease, twin, epidemiology

1. Introduction

The etiology of Parkinson disease (PD) is considered to be complex and to involve both genetic and environmental factors. Mutations have been identified in several genes in families with autosomal dominant or recessive PD, and multiple susceptibility genes have been reported (Lesage and Brice, 2009). Familial aggregation studies have consistently shown that having a relative with PD increases the risk of PD (Thacker and Ascherio, 2008), but these studies cannot differentiate between genetic and shared familial effects, such as rearing environment. This distinction can be made in twin studies, as monozygotic twins are genetically identical and dizygotic twins share on average half of the variation of their genome, while both share rearing environment. One twin study of PD including almost 20,000 men from the National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council (NAS-NRC) World War II Veteran Twins Registry reported similar concordance rates in monozygotic and dizygotic pairs in the total sample, but in cases with age of onset before 50 years, concordance rate was significantly higher in monozygotic than in dizygotic twins (Tanner et al., 1999). These results suggested that among males with late-onset PD, environmental factors are most important, while in early-onset PD, genetic factors also seem to play a role.

In our previous study, we screened all twins in the Swedish Twin Registry (STR) who were 50 years or above and alive in 1998 (N = 33,780 individuals) (Wirdefeldt et al., 2004). Through a combination of telephone interview results and linking the STR to the Swedish national Inpatient Discharge Register (IDR), we identified 247 twins with self-reported or register-based PD diagnosis. Only two pairs were concordant, suggesting that individual-specific environmental factors are most important in the etiology of PD although low-penetrant genes or gene by environment interactions could not be excluded. Shortcomings included the cross-sectional design and lack of clinical evaluations. Nevertheless, both the US and our Swedish twin data suggest that on a population basis, there is little impact of genetic variance.

The aims of the present study were 1) to apply a longitudinal design to study heritability of PD by following the twin cohort from the 1960s onwards using the national hospital discharge and cause of death registers, as well as information from clinical assessments, and 2) to re-evaluate the cross-sectional data after completion of clinical assessments of twins with suspected PD.

2. Methods

2. 1. Study population

2.1.1. Longitudinal study design

The STR contains information on more than 80,000 twin pairs born from 1886 and onwards in all of Sweden (Lichtenstein et al., 2002). Longitudinal analyses were based on all twins from same-sexed pairs born in 1952 or earlier. This sample, including 23,218 complete twin pairs, was followed from 1961 until 2005 or until death, whichever came first. We did not include opposite-sexed pairs, as the STR only includes a subset of all opposite-sexed pairs born 1906 – 1925, and none born before 1906.

2.1.2. Cross-sectional study design

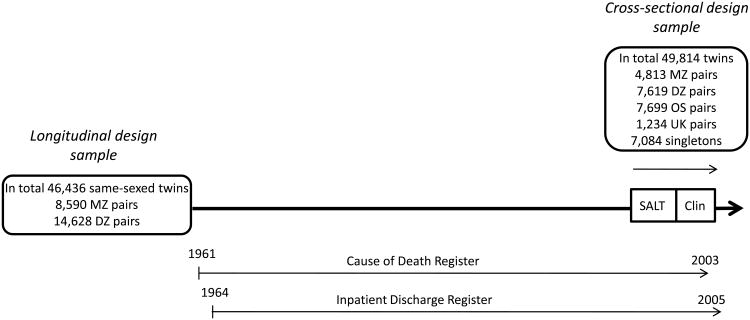

Cross-sectional analyses were based on all twins eligible for Screening Across the Lifespan Twin study (SALT) (Lichtenstein et al., 2002) who were 50 years or older at interview in 1998-2002 (N=49,814). This sample included 21,365 same- and opposite-sexed twin pairs and 7,084 singletons (predominantly those whose twin had died). The study design is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic description of study design. MZ = monozygotic, DZ = same-sexed dizygotic, OS = opposite-sexed, UK = unknown zygosity twin pairs. SALT (Screening Across the Lifespan Twin study) refers to the telephone screening for PD, Clin refers to the clinical workups for PD.

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Inpatient Discharge Register and Cause of Death Register

The IDR covers all public inpatient care in Sweden between 1987 and 2005. The Cause of Death Register (CDR) contains information on all deaths in Sweden between 1961 and 2003 (The National Board of Health and Welfare, 2010). The discharge diagnoses and causes of death are coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (WHO, 1955). The ICD codes to define PD and parkinsonism are described in Table 1. In the IDR, both primary and secondary diagnoses were considered, and in the CDR, both underlying and contributory causes of death were considered.

Table 1.

ICD codes, ICD diagnoses and categories of affection status in the present study.

| ICD code | ICD diagnosis | Category of affection status in the present study |

|---|---|---|

| ICD8 | ||

| 342.00 | Paralysis agitans | PD |

| 342.08 | Paralysis agitans Alia definita | Parkinsonism |

| 342.09 | Paralysis agitans NUD | Parkinsonism |

| 0.66 | Postencephalitic parkinsonism | Parkinsonism |

|

| ||

| ICD9 | ||

| 332.0 | PD | PD |

| 332.1 | Secondary parkinsonism | Parkinsonism |

| 333.0 | Other neurodegenerative diseases of the basal ganglia | Parkinsonism |

|

| ||

| ICD10 | ||

| G20 | PD | PD |

| G21.2 | Secondary parkinsonism due to external agents other than drugs | Parkinsonism |

| G21.3 | Postencephalitic parkinsonism | Parkinsonism |

| G21.8 | Other secondary parkinsonism | Parkinsonism |

| G21.9 | Secondary parkinsonism, unspecified | Parkinsonism |

| G23.1 | Progressive supranuclear ophthalmoplegia | Parkinsonism |

| G23.2 | Striatonigral degeneration | Parkinsonism |

| G23.8 | Other specified degenerative diseases of basal ganglia | Parkinsonism |

| G23.9 | Degenerative disease of basal ganglia, unspecified | Parkinsonism |

| G25.9 | Extrapyramidal and movement disorder, unspecified | Parkinsonism |

2.2.2. Diagnostic workups

Twins who were 50 years or older between 1998 and 2002 were screened in SALT for PD using telephone interviews. A follow-up telephone interview of twins who screened positive for PD was conducted in 2002. Twins with suspected PD still after this interview and twins with suspected PD based on in-person evaluation in a previous dementia study (Gatz et al., 2005) were evaluated further with review of medical records and visit by a physician in their homes for a complete somatic examination and medical history (Wirdefeldt et al., 2008). A subset of co-twins (N=102) who screened negative were also evaluated clinically (Wirdefeldt et al., 2008). Diagnoses were assigned according to the NINDS diagnostic criteria for PD (Gelb et al., 1999) by the study physician together with a movement disorder specialist. Of the twins with a hospital discharge PD diagnosis who were worked up clinically, the PD diagnosis was confirmed in 71%. For twins with a hospital discharge diagnosis of PD or parkinsonism, diagnostic accuracy was 87%.

2.2.3. Definition of affection status

We used the best available information based on the latest contact with the twin to obtain diagnoses. For twins who participated in the diagnostic workup, the diagnosis was based solely on this result. For twins who did not participate in the diagnostic workup, diagnoses were based on information from the IDR or CDR. We assigned diagnoses in two categories of affection status, which we refer to as PD and parkinsonism.

In the longitudinal sample, we identified 542 twins with PD and 65 twins with parkinsonism. In the cross-sectional sample, we identified 287 twins with PD and 79 twins with parkinsonism (Figure 1, Table 2). In total 241 twins were included in both longitudinal and cross-sectional samples, 185 with PD and 56 with parkinsonism.

Table 2.

Recruitment base, study population, numbers of twins with PD and parkinsonism, source of diagnostic information, age at onset, and age at last assessment.

| Longitudinal design | Recruitment base | Study population N | PD | Parkinsonism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same-sexed twin pairs born in 1952 or earlier | 46,436 4 | |||

| Total N of cases | 542 | 65 | ||

| Diagnosis based on register 1, N | (451) | (23) | ||

| Diagnosis based on clinical workup, N | (91) | (42) | ||

| Included in previous report (Wirdefeldt et al., 2004), N | (139) | (34) | ||

| Average age at onset 2 ± 1 SD | 74.6 ± 9.3 | 72.6 ±9.4 | ||

| Average age at last assessment 3 ± 1 SD | 79.8 ± 7.7 | 78.8 ± 8.9 | ||

| Cross-sectional design | ||||

|

| ||||

| Twins eligible for SALT 50 years or older at interview | 49,814 5 | |||

| Total N of cases | 287 | 79 | ||

| Diagnosis based on register 1, N | (150) | (22) | ||

| Diagnosis based on clinical workup, N | (137) 6 | (57) | ||

| Included in previous report (Wirdefeldt et al., 2004), N | (179) | (45) | ||

| Average age at onset 2 ± 1 SD | 70.3 ± 10.5 | 71.6 ± 11.1 | ||

| Average age at last assessment3 ± 1 SD | 78.8 ± 8.1 | 78.8 ± 8.5 | ||

Inpatient Discharge or Cause of Death Register.

Or, for register cases, age at first register diagnosis.

For clinical cases, age at clinical examination. For register cases, age on Dec 31, 2005, or, if dead before Dec 31, 2005, date of death.

N=23,218 complete twin pairs.

N=21,365 complete same- and opposite-sexed twin pairs + 7,084 singletons.

Including N=5 with self-reported PD diagnosis in Screening Across the Lifespan Twin study.

2.2.4. Zygosity determination

Determination of zygosity was based on questions about childhood resemblance in the questionnaires given at the time of registry compilation or in SALT (Lichtenstein et al., 2002).

2.3. Statistical analyses

2.3.1. Survival analyses

We tested for differences in survival by sex and zygosity using the log rank test.

2.3.2. Concordance rates and tetrachoric correlations

The probandwise concordance rate is the ratio of the number of probands in concordant twin pairs to the total number of probands (McGue, 1992). This measure can be interpreted as risk (one's risk of developing the disease given that one's co-twin has it). The tetrachoric correlation is the correlation coefficient between two categorical variables (affected/unaffected) and represents the correlation in liability to disease between two twins in a pair taking into account prevalence of the disease. If monozygotic twin pairs (who are genetically identical) have a higher concordance rate and higher tetrachoric correlation than dizygotic pairs (who share on average half of their genes), genetic effects are indicated.

For PD analyses, probandwise concordance rates and tetrachoric correlations with 95% confidence intervals were calculated considering all individuals in the study population without a PD diagnosis as unaffected. In secondary analyses, we considered as affected all individuals with parkinsonism in addition to those with PD (referred to as PD or parkinsonism). All individuals without PD or parkinsonism were considered as unaffected. Analyses were stratified by zygosity, sex, and in cross-sectional analyses, by age at onset (70 years or younger in at least one twin in a pair versus both twins above age 70). For unaffected twins, age at SALT interview was used.

2.3.3. Structural equation modeling

Structural equation modeling techniques are used to estimate the relative importance of genetic and environmental components of variance in liability to disease. Total phenotypic variance can be divided into genetic factors, shared familial environment (factors common to both members in a twin pair) and non-shared environment (factors unique to each twin). A liability-threshold model is assumed, in which liability to disease is normally distributed and manifested at a certain threshold as a categorical phenotype. The threshold corresponds to the prevalence of the disease and can be allowed to vary by sex and age. Prevalence by age group was calculated based on individuals surviving to the age of 70 versus those surviving to age of 71 or longer.

Due to the low concordance, we could not perform structural model fitting for the diagnostic category PD in the cross-sectional study design. For the PD or parkinsonism category in the cross-sectional design and for both diagnostic categories in the longitudinal study design, models were fit to raw data including affection status and age of onset (or age at first register diagnosis) for male and female monozygotic, male and female same-sexed dizygotic, as well as opposite-sexed twin pairs (in cross-sectional analysis) using the Mx program (Neale, 1994). Sex-specific thresholds, estimated from the data, were adjusted for age. The genetic correlation was fixed at 0.5 for both same-sexed dizygotic and opposite-sexed pairs. We used the log likelihood ratio test to test the statistical significance of parameters dropped from the different models. When this test is statistically significant, it indicates the parameter could not be dropped from the model (i e, the estimate is significantly greater than zero).

To account for potential effects of differential survival across age cohorts, the longitudinal data were analyzed using the SAS PROC LIFEREG (The SAS Institute, 2002-2003), using an approach similar to the DeFries and Fulker method for continuous data (DeFries and Fulker, 1985) and the extension by Sham et al (Sham et al., 1994) to binary data to estimate heritability for a censored trait (Prescott et al., 2004). Age at onset in the proband was the dependent variable and the co-twin's age at onset as well as the co-twin's age at onset multiplied by 0.5 for dizygotic twins and by 1 for monozygotic twins were independent variables. These variables correspond to shared environmental effects and genetic effects, respectively. Additional independent variables were age in 1961 and sex. The statistical significance of parameters in the model was tested by the log likelihood ratio test. To test for sex differences in the relative importance of genetic and environmental factors for disease, we included an interaction term between sex and the co-twin's age at onset.

3. Results

3.1 Survival analyses

We first compared survival by sex and zygosity. As expected, women lived longer than men (log rank test, p<0.0001). In men, monozygotic twins lived on average 0.5 years longer than dizygotic twins (log rank test, p=0.0007), but in women, survival did not differ significantly by zygosity. When considering PD cases only, there was no difference in survival by zygosity when adjusting for sex. Survival free of PD was longer for monozygotic twins than for dizygotic twins (log rank test, p=0.02).

3.2. Concordance rates and tetrachoric correlations

In the longitudinal study design, 16 twin pairs were concordant for PD, 9 monozygotic and 7 same-sexed dizygotic (Table 3). For PD or parkinsonism, there were 22 concordant twin pairs, 12 monozygotic and 10 same-sexed dizygotic. For both diagnostic categories, concordance rates and tetrachoric correlations were more than double in monozygotic than in same-sexed dizygotic pairs, although the confidence intervals overlapped. Differences in concordances and tetrachoric correlations by zygosity were more pronounced in men than in women (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence, numbers of twin pairs discordant and concordant for PD as well as PD or parkinsonism in longitudinal and cross-sectional analyses, probandwise concordance rates and tetrachoric correlations with 95% confidence intervals.

| Longitudinal design | Prevalence (%) | Discordant (N) | Concordant Affected (N) | Probandwise concordance rate | Tetrachoric correlation (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | ||||||

| MZ | 1.0 | 151 | 9 | 0.11 | 0.46 (0.31-0.61) | |

| Men | 1.1 | 72 | 6 | 0.14 | 0.53 (0.34-0.71) | |

| Women | 0.9 | 79 | 3 | 0.07 | 0.37 (0.13-0.61 | |

| DZ | 1.3 | 359 | 7 | 0.04 | 0.19 (0.05-0.33) | |

| Men | 1.4 | 179 | 2 | 0.02 | 0.08 (0-0.31) | |

| Women | 1.2 | 180 | 5 | 0.05 | 0.26 (0.09-0.44) | |

| PD or parkinsonism | ||||||

| MZ | 1.1 | 164 | 12 | 0.13 | 0.49 (0.36-0.63) | |

| Men | 1.2 | 77 | 8 | 0.17 | 0.57 (0.40-0.73) | |

| Women | 1.0 | 87 | 4 | 0.08 | 0.40 (0.18-0.61) | |

| DZ | 1.4 | 399 | 10 | 0.05 | 0.22 (0.09-0.35) | |

| Men | 1.5 | 198 | 4 | 0.04 | 0.17 (0-0.36) | |

| Women | 1.3 | 201 | 6 | 0.06 | 0.26 (0.10-0.43) | |

| Cross-sectional design | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| PD | ||||||

| MZ | 0.6 | 44 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.36 (0.00-0.72) | |

| Men | 0.6 | 20 | 1 | 0.09 | 0.51 (0.10-0.92) | |

| Women | 0.5 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 1 | |

| ≤ 70 years | 0.2 | 22 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.49 (0.11-0.87) | |

| > 70 years | 1.4 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 1 | |

| DZ | 0.7 | 93 | 2 | 0.04 | 0.29 (0.03-0.54) | |

| Men | 0.7 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 1 | |

| Women | 0.7 | 46 | 2 | 0.08 | 0.44 (0.15-0.72) | |

| ≤ 70 years | 0.3 | 48 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.33 (0.00-0.68) | |

| > 70 years | 1.6 | 45 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.21 (0.00-0.60) | |

| OS | 0.5 | 69 | 0 | 0 | 0 1 | |

| Men | 0.6 | 47 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Women | 0.4 | 22 | NA | NA | NA | |

| ≤ 70 years | 0.2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 1 | |

| > 70 years | 1.3 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 1 | |

| PD or parkinsonism | ||||||

| MZ | 0.7 | 51 | 3 | 0.11 | 0.53 (0.29-0.77) | |

| Men | 0.7 | 21 | 3 | 0.22 | 0.70 (0.46-0.94) | |

| Women | 0.7 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 1 | |

| ≤ 70 years | 0.3 | 27 | 2 | 0.13 | 0.58 (0.29-0.86) | |

| > 70 years | 1.8 | 24 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.48 (0.03-0.93) | |

| DZ | 0.9 | 110 | 5 | 0.08 | 0.41 (0.22-0.60) | |

| Men | 1.0 | 54 | 2 | 0.07 | 0.35 (0.06-0.65) | |

| Women | 0.8 | 56 | 3 | 0.10 | 0.46 (0.21-0.70) | |

| ≤ 70 years | 0.3 | 57 | 2 | 0.07 | 0.40 (0.12-0.67) | |

| > 70 years | 2.1 | 53 | 3 | 0.10 | 0.38 (0.11-0.65) | |

| OS | 0.6 | 81 | 2 | 0.05 | 0.33 (0.06-0.59) | |

| Men | 0.8 | 56 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Women | 0.4 | 25 | NA | NA | NA | |

| ≤ 70 years | 0.3 | 48 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.33 (0.00-0.68) | |

| > 70 years | 1.7 | 33 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.28 (0.00-0.69) | |

MZ = monozygotic, DZ = same-sexed dizygotic, OS = opposite-sexed twin pairs. NA = not applicable. Concordance rates and tetrachoric correlations cannot be computed by sex for OS twin pairs.

When tetrachoric correlation is zero, confidence intervals cannot be computed.

In the cross-sectional design, only three twin pairs were concordant for PD (Table 3). Concordances were very low or zero, regardless of zygosity, sex, and age at onset. For PD or parkinsonism, there were 10 concordant twin pairs, three monozygotic, five same-sexed dizygotic, and two opposite-sexed. Although confidence intervals overlapped, tetrachoric correlations were double in male monozygotic twin pairs compared to male dizygotic pairs, but were otherwise low or zero. Tetrachoric correlations were larger in young than in old twins, and although confidence intervals overlapped, differences by zygosity were also more pronounced among young than among old twins (Table 3).

3.3. Structural equation modeling

For PD in the longitudinal study design, the full structural equation model yielded an estimate of the genetic component at 34% in men and 19% in women (Table 4). When variance estimates were set equal in men and women, the genetic component was estimated at 34%, the non-shared environmental component at 66%, and the shared environmental component could be dropped. The genetic component could not be dropped without significantly worsening the model fit. There were no significant sex differences, but power for this test was limited.

Table 4.

Estimates of proportions of variance explained by genetic (A), shared environmental (C) and non-shared environmental (E) variance for PD as well as PD or parkinsonism in longitudinal and cross-sectional study designs.

| Men | Women | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Model | A | C | E | A | C | E | N of estimated parameters | Log likelihood difference | P value, log likelihood ratio test |

| PD; longitudinal design | |||||||||

| Full 1 | 0.34 | 0 | 0.66 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.69 | 10 | ||

| Men=Women 2 | 0.34 | 0 | 0.66 | 0.34 | 0 | 0.66 | 7 | 0.31 4 | 0.96 |

| Reduced 3 | 0.34 | 0.66 | 0.34 | 0.66 | 6 | 0 5 | 1 | ||

| PD or parkinsonism; longitudinal design | |||||||||

| Full 1 | 0.41 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.65 | 10 | ||

| Men=Women 2 | 0.40 | 0 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0 | 0.60 | 7 | 0.28 4 | 0.96 |

| Reduced 3 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 6 | 0 5 | 1 | ||

| PD or parkinsonism; cross-sectional design | |||||||||

| Full 1 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.67 | 10 | ||

| Men=Women 2 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.60 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.60 | 7 | 1.98 4 | 0.58 |

| Reduced 3 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 6 | 1.03 5 | 0.31 | ||

Genetic correlation (rg) and environmental correlation (rc) were held fixed at 0.5 and 1.0, respectively.

A, C and E were estimated and allowed to differ by sex.

A, C and E were constrained to be equal for men and women.

A and E were estimated and constrained to be equal in men and women.

Compared to full model.

Compared to Men=Women model.

For PD or parkinsonism in the longitudinal study design, the full model yielded genetic variance estimates at 41% in men and 27% in women (Table 4). When estimates were set equal in men and women, the genetic component for PD or parkinsonism was estimated at 40%, the non-shared environmental component at 60%, and the shared environmental component could be dropped. Similar to PD, there were no significant sex differences and the genetic component could not be dropped without significantly worsening the model fit.

Using PROC LIFEREG (The SAS Institute, 2002-2003), we then compared reduced models nested within the full model that included genetic, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental effects, as well as age in 1961 and sex. Similar to the structural equation modeling results, the genetic effect was significant in PD as well as PD or parkinsonism, while the shared environmental component could be dropped (eTable 1). Further, the interaction term accounting for sex differences was non-significant in PD as well as PD or parkinsonism (results not shown).

For PD or parkinsonism in the cross-sectional design, for men, the genetic variance estimate in the full model was similar to the longitudinal study design. In women, the cross-sectional estimate was lower (Table 4). However, the sex differences were not statistically significant. When variance estimates were set equal in men and women, the genetic component for PD or parkinsonism was estimated at 19%, the non-shared environmental component at 60%, and the shared environmental component at 20%. However, neither the genetic nor shared environmental components were statistically significant when separately tested.

4. Discussion

In this population-based study of heritability of PD based on clinical assessments as well as national registers, we found modest but significant genetic effects for PD in a longitudinal design that took survival into account.

In contrast to Alzheimer's disease, PD is relatively rare, with a lifetime risk of 1-2% (Elbaz et al., 2002). A small twin study (Piccini et al., 1999) that assessed nigrostriatal dysfunction using positron emission tomography in a longitudinal design found higher monozygotic than dizygotic concordance, but previous large-scale twin studies of PD were based on cross-sectional data (Tanner et al., 1999; Wirdefeldt et al., 2004), and did not provide significant estimates of heritability. The apparent discrepancy between cross-sectional and longitudinal results is most likely explained by increased possibility of detecting concordant pairs with extension of follow-up.

Our finding of a modest but significant genetic effect is in line with familial aggregation and genetic studies in PD. A meta-analysis of familial aggregation studies estimated the relative risk of PD given a first-degree relative with PD at 2.9 (Thacker and Ascherio, 2008). Considering dizygotic twins only, we obtained a similar estimate (odds ratio 3.1). To date, 12 PD genes and an additional three genetic loci have been identified (Lesage and Brice, 2009; Sidransky et al., 2009); two additional loci await confirmation (Payami et al., 2003; Satake et al., 2009). Nevertheless, single gene effects most likely account for only a small proportion of all PD, with the exception of certain populations. For example, mutations in the LRRK2 gene (the most common PD gene) are frequent in North African and Jewish populations (Lesage et al., 2006; Ozelius et al., 2006), but across all populations, variation in this gene is estimated to account for only 5-10% of familial and 1-2% of sporadic PD cases (Brice, 2005). Even in cases with known genetic risks, penetrance may be incomplete (for example, penetrance for LRRK2 mutations has been estimated at 51% at 69 years (Healy et al., 2008) and penetrance for α-Synuclein duplications at 44% overall (Nishioka et al., 2009)). Taking previous as well as the present twin data together, there seems to be a modest genetic component in PD, although environmental factors still seem to play the largest role. These data shed light on PD etiology, indicating that genetic effects are not only limited to specific high-penetrant mutations, but to more general genetic susceptibility, potentially in an interaction with environmental triggers.

We also found moderate heritability for the diagnostic category referred to as PD or parkinsonism. To our knowledge, this is the first report that assessed heritability of parkinsonism. The genetic effect in parkinsonism may be explained by genes related to development of parkinsonism specifically, eg cerebrovascular risk factors, or genes influencing susceptibility to both PD and parkinsonism.

This was a large population-based study that included both men and women, and the first twin study of PD that applied a longitudinal design taking survival into account. In the cross-sectional design, cases were carefully ascertained using in-person examinations and medical records. Using hospital discharge and cause of death information in addition to telephone screening, we were able to identify PD cases among non-respondents to the telephone interview. One limitation is that specificity of register-based PD diagnoses is relatively high but not perfect. As misclassification occurred mainly between PD and parkinsonism, some twin pairs concordant for register-based PD diagnosis may be concordant for parkinsonism instead of PD. Nevertheless, there is no reason to suspect that quality of register-based diagnoses differs by zygosity, and thus, the results of the comparison between monozygotic and dizygotic twins would not be affected. In the cross-sectional design, hospital discharge diagnostic information was only used for twins who did not participate in the telephone screening, whom we therefore were unable to visit. A potential limitation of the longitudinal analyses is differences by zygosity in disease-free survival. Although male monozygotic twins lived longer than dizygotic twins, a finding also reported by the Danish Twin Registry (Christensen et al., 2001), dizygotic twins developed PD earlier than monozygotic twins, suggesting that the differences by zygosity we observed are not due solely to differences in survival. Another limitation is failure to assess twins with PD younger than 50 years of age, among whom more familial PD may have been found. Finally, in the heritability analyses, we had limited power to test for sex differences and for genetic versus shared environmental effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health; ES10758 and AG 08724, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, the Swedish Society of Medicine, funds from the Karolinska Institutet, and the Parkinson Foundation in Sweden. The funding sources had no involvement in any part of the study.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement. None of the authors has an actual or potential conflict of interest. All procedures were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the project was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Karin Wirdefeldt, Email: karin.wirdefeldt@ki.se.

Margaret Gatz, Email: gatz@college.usc.edu.

Chandra A. Reynolds, Email: chandra.reynolds@ucr.edu.

Carol A. Prescott, Email: cprescot@usc.edu.

Nancy L. Pedersen, Email: nancy.pedersen@ki.se.

References

- Brice A. Genetics of Parkinson's disease: LRRK2 on the rise. Brain. 2005;128:2760–2762. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Wienke A, Skytthe A, Holm NV, Vaupel JW, Yashin AI. Cardiovascular mortality in twins and the fetal origins hypothesis. Twin Res. 2001;4:344–349. doi: 10.1375/1369052012506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFries JC, Fulker DW. Multiple regression analysis of twin data. Behav Genet. 1985;15:467–473. doi: 10.1007/BF01066239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaz A, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Peterson BJ, Ahlskog JE, Schaid DJ, Rocca WA. Risk tables for parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatz M, Fratiglioni L, Johansson B, Berg S, Mortimer JA, Reynolds CA, Fiske A, Pedersen NL. Complete ascertainment of dementia in the Swedish Twin Registry: the HARMONY study. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:33–39. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy DG, Falchi M, O'Sullivan SS, Bonifati V, Durr A, Bressman S, Brice A, Aasly J, Zabetian CP, Goldwurm S, Ferreira JJ, Tolosa E, Kay DM, Klein C, Williams DR, Marras C, Lang AE, Wszolek ZK, Berciano J, Schapira AH, Lynch T, Bhatia KP, Gasser T, Lees AJ, Wood NW. Phenotype, genotype, and worldwide genetic penetrance of LRRK2-associated Parkinson's disease: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:583–590. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70117-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage S, Durr A, Tazir M, Lohmann E, Leutenegger AL, Janin S, Pollak P, Brice A. LRRK2 G2019S as a cause of Parkinson's disease in North African Arabs. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:422–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc055540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage S, Brice A. Parkinson's disease: from monogenic forms to genetic susceptibility factors. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R48–59. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, De Faire U, Floderus B, Svartengren M, Svedberg P, Pedersen NL. The Swedish Twin Registry: a unique resource for clinical, epidemiological and genetic studies. J Intern Med. 2002;252:184–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M. When assessing twin concordance, use the probandwise not the pairwise rate. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:171–176. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC. MX: Statistical modeling. Richmond, VA: Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka K, Ross OA, Ishii K, Kachergus JM, Ishiwata K, Kitagawa M, Kono S, Obi T, Mizoguchi K, Inoue Y, Imai H, Takanashi M, Mizuno Y, Farrer MJ, Hattori N. Expanding the clinical phenotype of SNCA duplication carriers. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1811–1819. doi: 10.1002/mds.22682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozelius LJ, Senthil G, Saunders-Pullman R, Ohmann E, Deligtisch A, Tagliati M, Hunt AL, Klein C, Henick B, Hailpern SM, Lipton RB, Soto-Valencia J, Risch N, Bressman SB. LRRK2 G2019S as a cause of Parkinson's disease in Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:424–425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc055509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payami H, Nutt J, Gancher S, Bird T, McNeal MG, Seltzer WK, Hussey J, Lockhart P, Gwinn-Hardy K, Singleton AA, Singleton AB, Hardy J, Farrer M. SCA2 may present as levodopa-responsive parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2003;18:425–429. doi: 10.1002/mds.10375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccini P, Burn DJ, Ceravolo R, Maraganore D, Brooks DJ. The role of inheritance in sporadic Parkinson's disease: evidence from a longitudinal study of dopaminergic function in twins. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:577–582. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199905)45:5<577::aid-ana5>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Kuhn JS, Pedersen NL. French paradox redux: Are the “protective” effects of moderate alcohol consumption direct or indirect? Behav Genet. 2004;34:656. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Satake W, Nakabayashi Y, Mizuta I, Hirota Y, Ito C, Kubo M, Kawaguchi T, Tsunoda T, Watanabe M, Takeda A, Tomiyama H, Nakashima K, Hasegawa K, Obata F, Yoshikawa T, Kawakami H, Sakoda S, Yamamoto M, Hattori N, Murata M, Nakamura Y, Toda T. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants at four loci as genetic risk factors for Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1303–1307. doi: 10.1038/ng.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham PC, Walters EE, Neale MC, Heath AC, MacLean CJ, Kendler KS. Logistic regression analysis of twin data: estimation of parameters of the multifactorial liability-threshold model. Behav Genet. 1994;24:229–238. doi: 10.1007/BF01067190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, Aharon-Peretz J, Annesi G, Barbosa ER, Bar-Shira A, Berg D, Bras J, Brice A, Chen CM, Clark LN, Condroyer C, De Marco EV, Durr A, Eblan MJ, Fahn S, Farrer MJ, Fung HC, Gan-Or Z, Gasser T, Gershoni-Baruch R, Giladi N, Griffith A, Gurevich T, Januario C, Kropp P, Lang AE, Lee-Chen GJ, Lesage S, Marder K, Mata IF, Mirelman A, Mitsui J, Mizuta I, Nicoletti G, Oliveira C, Ottman R, Orr-Urtreger A, Pereira LV, Quattrone A, Rogaeva E, Rolfs A, Rosenbaum H, Rozenberg R, Samii A, Samaddar T, Schulte C, Sharma M, Singleton A, Spitz M, Tan EK, Tayebi N, Toda T, Troiano AR, Tsuji S, Wittstock M, Wolfsberg TG, Wu YR, Zabetian CP, Zhao Y, Ziegler SG. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1651–1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner CM, Ottman R, Goldman SM, Ellenberg J, Chan P, Mayeux R, Langston JW. Parkinson disease in twins: an etiologic study. JAMA. 1999;281:341–346. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thacker EL, Ascherio A. Familial aggregation of Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1174–1183. doi: 10.1002/mds.22067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden. www.socialstyrelsen.se. Accessed June 23, 2010

- The SAS Institute, Inc. The SAS System for Windows, Release 9.1. Cary, NC: The SAS Institute; 2002-2003. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Manual of the international classification of diseases, injuries and causes of death, 7th revision. Geneva: WHO; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Wirdefeldt K, Gatz M, Bakaysa SL, Fiske A, Flensburg M, Petzinger GM, Widner H, Lew MF, Welsh M, Pedersen NL. Complete ascertainment of Parkinson disease in the Swedish Twin Registry. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1765–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirdefeldt K, Gatz M, Schalling M, Pedersen NL. No evidence for heritability of Parkinson disease in Swedish twins. Neurology. 2004;63:305–311. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129841.30587.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.