Abstract

Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. The most common manifestation of cardiovascular disease is myocardial infarction (MI), which can ultimately lead to congestive heart failure (CHF). Cell therap (cardiomyoplasty) is a new potential therapeutic treatment alternative for the damaged heart. Recent preclinical and clinical studies have shown that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a promising cell type for cardiomyoplasty applications. However, a major limitation is the poor survival rate of transplanted stem cells in the infarcted heart. miR-133a is an abundantly expressed microRNA in the cardiac muscle and is down-regulated in patients with MI. We hypothesized that reprogramming MSCs using microRNA-mimics (double-stranded oligonucleotides) will improve survival of stem cells in the damaged heart. MSCs were transfected with miR-133a mimic and antagomirs and the levels of miR-133a were measured by qRT-PCR. Rat hearts were subjected to MI and MSCs transfected with miR-133a mimic or antagomir were implanted in the ischemic heart. Four weeks after MI, cardiac function, cardiac fibrosis, miR-133a levels and apoptosis related genes (Apaf-1, Capase-9 and Caspase-3) were measured in the heart. We found that transfecting MSCs with miR-133a mimic improves survival of MSCs as determined by the MTT assay. Similarly, transplantation of miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs in rat hearts subjected to MI led to a significant increase in cell engraftment, cardiac function and decreased fibrosis when compared with MSCs only or MI groups. At the molecular level, qRT-PCR data demonstrated a significant decrease in expression of the pro-apoptotic genes; Apaf-1, caspase-9 and caspase-3 in the miR-133a mimic transplanted group. Further, luciferase reporter assay confirmed that miR- 133a is a direct target for Apaf-1. Overall, bioengineering of stem cells through miRNAs manipulation could potentially improve the therapeutic outcome of patients undergoing stem cell transplantation for myocardial infarction.

Keywords: Myocardial Infarction, Mesenchymal Stem Cells, microRNAs

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide with a large financial burden on the economy (1). Post-MI, with the loss of functional cardiomyocytes, the heart undergoes adverse remodeling with progressive thinning of the infarcted wall, cardiac dilatation and loss of contractile function, all of which can lead to heart failure. At the cellular level, cardiomyocytes undergo apoptosis and necrosis and are subsequently replaced with fibroblasts and fibrous tissue. Following an acute MI, 8-20% of men and 18-23% of women will develop heart failure within 5 years (2). There are currently an estimated 5.1 million Americans who have heart failure and the prevalence of heart failure is projected to increase by 46% by 2030 (2). Given this burden of CV disease, interventions that can reduce the incidence or severity of heart failure following acute MI are sorely needed. Stem cell based therapy (cardiomyoplasty) is one of the most promising therapeutic treatment options for regeneration of the infarcted myocardium (3-7). In cell therapy, undifferentiated stem cells are transplanted into the damaged and at-risk regions of the heart to stimulate angiogenesis and/or myogenesis and attenuate ventricular remodeling (3-7). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent, adult stem cells that are easily expanded in culture and can differentiate into several lineages, including vascular endothelial cells and cardiomyocyte like cells (8, 9). MSCs injected into an infracted heart have demonstrated engraftment and improved cardiac function (10). MSCs transplantation has also been shown to induce therapeutic angiogenesis through VEGF production (11). Additional studies suggest that bone marrow stem cells (BMSC) are able to augment cardiac function following MI through a variety of mechanisms including differentiation into cardiomyocyte type cells, fusion with host cells, and stimulating neovascularization (4, 9, 12-14). Unfortunately, one of the major ongoing impediments to the use of stem cell transplantation has been the low survival of implanted cells in the infarcted myocardium. The lack of oxygen and substrate in the ischemic heart ultimately leads to apoptosis of the majority of the transplanted stem cells. Initial results, while promising, demonstrates the need for further work to utilize these therapies in patients who have suffered acute myocardial infarction.

Approximately 1500 miRNAs have been identified in vertebrates and many exhibit tissue-specific patterns of expression (15, 16). Because of their ability to target classes of messenger RNAs that direct cell proliferation, differentiation, and programmed death (17), tissue-specific miRNA expression has given rise to the hypothesis that they play a major role in tissue differentiation and organ development. There appears to be 150–200 cardiac-expressed miRNAs, many of which are dynamically regulated in response to acute and chronic cardiac stress. There is increasing evidence that modulated miRNA expression is an important component of the acute stress-response mechanism of the heart and that this additional level of regulatory complexity contributes both to cardiac homeostasis in health and to myocardial pathology in disease. The miRNAs which are muscle specific (myomiRs) are miR-1, miR-133, miR-206 and miR-208. miR-133a has been proposed as a novel therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease (18) and is down regulated in heart samples isolated from patients with MI (19, 20) and cardiac hypertrophy (21-23). Additionally, miR-133a plays a role in terminating embryonic cardiomyocyte proliferation (24), preventing cardiac hypertrophy (25), attenuating fibrosis (26) and even cardiac remodeling (27). The main objective of this work was to test the hypothesis that forced/induced expression of miR-133a in MSCs can improve MSC survival and engraftment in the ischemic microenvironment of the heart.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Characterization of MSCs

MSCs were isolated from bone-marrow of Fisher-344 (250-300 grams) rats and characterized for the most common positive (CD44, CD29) and negative (CD14, CD45) cell surface markers by FACS as published earlier (28, 29).

Transient Transfection of MSCs with miR-133a mimic/antagomir

The day prior to transient transfection, MSCs were plated in six-well plates at a density to achieve 60-80% confluence. On the day of transfection, cells were washed once in 1× PBS and fresh media was added to the cells and then transfected using the siPORT NeoFX transfection reagent (Ambion, Foster City, CA) with either 50nM/100nM of rat mature miR-133a mimic (double-stranded oligonucleotide; Life Technologies, NY) or 50nM/100nM of miR-133a antagomir/inhibitor (antisense single-stranded chemically modified oligonuculeotide; CAAUGCUUUGCUAAAGCUGGUAAAAUGGAACCAA AUCGCCUCUUCAAUGGAUUUGGUCCCCUUCAACCAGCUGUAGCUAUGCAUUGA, Life Technologies, NY). Cells transfected with scrambled miRNA served as negative controls.

MSCs (Passage 3-4) were plated in 100 mm dishes for 48 hours and incubated at 37°C. On the day of transfection, the confluency of the cells (60-80%) was confirmed. Ten minutes before the transfection, MSCs were then trypsinized and diluted in normal fresh media to inactivate the trypsin and incubated at 37°C. In separate sterile tubes, a master mix of RNA and transfection agent was prepared to eliminate contamination and variability. siPORT NeoFX ( Life Technologies, NY) transfection agent was diluted in opti-MEM I medium ( 5ul siPORT NeoFX + 95ul opti-MEM I medium / one well of 6-well plate) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The transfection reagent complex was gently mixed with diluted miRNA (miR-133a mimic/inhibitor; 50 nM & 100 nM) and siPORT NeoFX and incubated for additional 10 min at room temperature. Similarly, negative pre-miR, scramble miRNA and hsa-miR-1 precursor as a positive control were used at the same concentration as experimental miRNA-133a. The miRNA/siPORT NeoFX complex (100ul) was added to each well of a 6-well sterile plate. Next, MSCs suspension was mixed with fresh warm media and added to each well (0.2×106 MSCs) containing the transfection complexes and gently mixed by tilting the plate back and forth to evenly distribute the complexes. Transfected MSCs were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C in normal culture conditions. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) transfection was done side-by-side to test the transfection efficiency. Average efficiency was 65% GFP positive cells. Cells were incubated for 24 hours and then subjected to miRNA expression profiling, proliferation analysis and quantification of gene transcripts (30).

Cell viability assay to assess the survival of MSCs subjected to simulated ischemic conditions by glucose and serum deprivation

Forty-eight hours after transfection, MSCs transfected with miR-133a mimic or inhibitor were cultured for 12 hours under glucose and FBS-free DMEM medium to simulate ischemic injury to the cells. The growth rate of transfected MSCs with miR-133a mimic or inhibitor (50 nM and 100 nM) were compared to experimental controls, untreated cells, mock and empty transfected cells at 12 hours following glucose and serum derivation by the MTT assay as described previously (31). Each assay was performed in triplicates and repeated 3 times. Additionally, phase contrast images were acquired to assess the cell morphology after ischemic exposure of MSCs with or without miRNA transfection.

Induction of myocardial infarction and MSCs transplantation

Animals were divided into five different groups (n=6/group), 1) Control (Untreated group); 2) Myocardial Infarction (MI, Media treated); 3) MSCs (MI + MSCs transplanted group); 4) miR-133a mimic + MSCs (MI + miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs group); and 5) miR-133a antagomir + MSCs (MI + miR-133a antagomir transfected MSCs group). The model used in this study involved temporary (1 h) ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery and release. This in vivo model more closely replicates the clinical pathology, providing a more sound translational approach to cardiomyoplastic therapy following acute MI as described previously (28, 29). Fisher-344 rats (250-300 grams) were anaesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg, i.p) and xylazine (5 mg/kg, i.p) and maintained under anesthesia using isoflurane (1.5-2.0%) mixed with air.

The LAD was identified, and temporarily ligated. After 1 h of ischemia, the ligation was released and the tissue was reperfused for 30-min at which time MSCs were injected as previously performed by our laboratory (28, 29). ECG measurements were performed before and after LAD ligation to confirm ST segment elevation. All of the procedures were performed with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Ohio State University and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 86-23).

Analysis of miRNAs expression patterns by heat map

For miRNA profiling data, low-expressed miRNAs were first filtered out and a quantile normalization method was used to normalize samples. Linear models were then used to detect differentially expressed miRNAs between control and MI groups or between different time points. Variance smoothing method was used to stabilize variance estimates (32). Significance was adjusted by controlling the mean number of false positives. Heat map by hierarchical clustering method was used to display the top differentially expressed miRNAs and their expression patterns

Transplantation of miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs in the ischemic heart

MSCs (Passage 3-4) transfected with miR-133a-mimic or antagomir were transplanted into the ischemic hearts 30-min after reperfusion. Four intramyocardial injections of miR-mimic or antagomir transfected MSCs (total of 1.0×106 cells in 100 μl of serum-free media) were transplanted in the infarct and peri-infarct regions of the hearts. In the non-stem cell treated group, serum-free media (100 μl) was injected without the stem cells.

RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated from MSCs and/or rat heart samples by homogenization in Trizol® Reagent using Soft Tissue Omni Homogenizer Tips (Omni International; Marietta, GA), as previously described(30). RNA was purified by using the Trizol method followed by precipitation at -20°C overnight to increase the yield of small RNAs. RNA integrity was confirmed by gel electrophoresis using the FlashGel® RNA cassette system (Lonza, Rockland, ME) (30).

Detection of miR-133a expression by qRT-PCR in-vitro and in-vivo

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol method (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) in miRNA transfected cells. The RNA was subsequently treated with RNAse free DNase I. Similarly, cardiac tissue samples were pooled from three different hearts and analysis of each individual miRNA was performed by converting RNA (100 ng) to cDNA by priming with looped primers specific for each miRNA according to manufacturers' instructions. Mature Rat miR-133a was quantified by utilizing TaqMan microRNA assay kits specific for each miRNA according to manufacturer protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described (30). Experiments were performed using an ABI PRISM Sequence Detector 7700. Primers to the internal controls, small nucleolar snoRNAs 202 and U6 were used (33).

Quantitative Real-Time-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses for Apaf-1, Caspases-9 and Caspases-3 transcripts in-vitro and in-vivo

To analyze Apaf-1, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 transcripts, RNA was purified and subjected to cDNA synthesis from 1 μg RNA by oligo-dT primer and superscript II (Invitrogen) then amplification was performed with the SYBR green-based detection system using standard conditions. Commercial primer sets for all genes were obtained from SA Biosciences/Qiagen (Frederick, MD) except the housekeeping gene adenylyl cyclase-associated protein -1 (CAP-1); CAP-1 forward primer 5′-GAAGGCGGTGATTTTAACGA-3′ and CAP-1 reverse primer 5′- TCCAGCGATTTCTGTCACTG-3′. For normalization of expression levels, GAPDH and CAP-1 primers were used. All miRNA and mRNA expressions were quantified using 2^-ΔdCT method (30).

Analysis of cardiac function by M-mode echocardiography

Cardiac function was analyzed using ultrasound echocardiography prior to surgery (at baseline) and at one-week after the induction of MI and miR-133a-mimic or antagomir transfected MSCs transplantation. Rats were anaesthetized using 1.5-2.0% isoflurane and M-mode ultrasound images were acquired using a Vevo-2100 (Visualsonics; Toronto, Canada) high-resolution ultrasound imaging system as published earlier (28, 29).

Assessment of fibrosis

Masson-trichrome immunohistochemical staining was performed to assess the extent of cardiac fibrosis in all the groups with/without MSCS transplantation at one-week post-MI. Rats were euthanized at one-week post-transplantation and hearts were quickly excised, washed with ice-cold PBS and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Formalin-fixed samples were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm thick sections. Quantification of cardiac fibrosis was performed using MetaMorph image analysis software as published earlier (28, 29).

Luciferase reporter assay

Full 3′UTR sequence of WT Apaf-1 gene was cloned downstream of the secreted Gaussia luciferase (GLuc) reporter gene and CMV promote in pEZX-MT05 dual-reporter REPORT™ luciferase vector from GeneCopoeia. The predicted miR-133a two binding sites located in the 3′UTR of apaf-1 were deleted individually (mut1 at position 122 and mut2at position 678) predicted by Segal lab of computational biology (http://132.77.150.113/pubs/mir07/mir07_prediction.html). These mutational sites were engineered in our lab and verified computationally not to create a new miR-133a binding site by creating these mutations. Once these mutations were engineered, they were sent to GeneCopoeia (Rockville, MD) to be cloned. The inserts from all cloned plasmids were sequenced by Plant-Microbe Genomics Facility/The Ohio State University to verify identities.

HEK293 cells (5×103) were plated in 96 well plates. WT, Mut1 and Mut2 constructs were transfected into the cells along with miR-133a mimic, antagomir or scrambled as described earlier (30). After 24 hours of transfection, luciferase activity was measured using DualLight® assay system (Applied Biosystems) after normalization as described earlier (30) and according to the manufacturer's instructions. The relative luciferase activity was calculated as the ratio between the firefly and renilla luciferase expression and transfection was repeated at least four times.

Data Analysis

For data other than miRNA profiling, the statistical significance of the results was evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and all pairwise multiple comparison procedures were done by Tukey's post hoc test. The values were expressed as mean±S.D. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Systat software and SigmaPlot 12 were used for graphs and data analysis.

Results

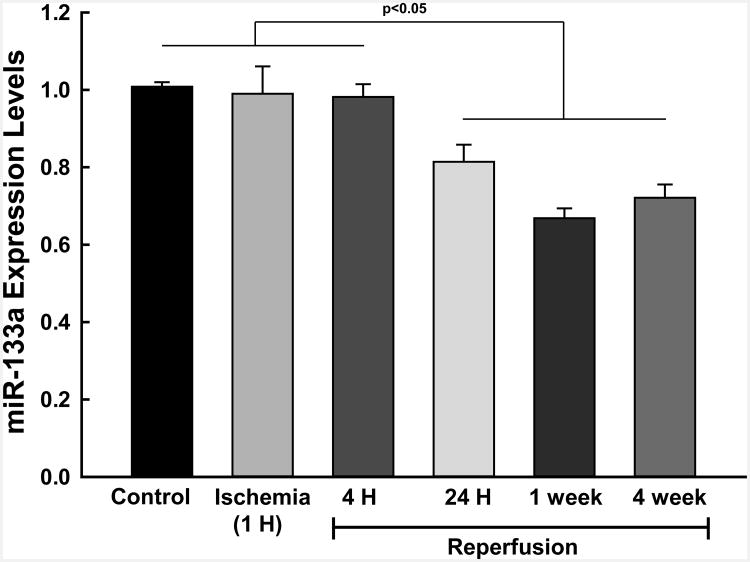

Heat-Map depicting down-regulation of miR-133a in hearts subjected to ischemia-reperfusion injury

Heat-Map data from rats subjected to acute myocardial infarction (MI) and at different time intervals (0, 4, & 24 (hours); 1 and 4 weeks) showed a down-regulation of miR-133a in the reperfused heart. Microarray profiling of miRNAs expression was performed in control and MI groups at different time points to study the differences in miRNA expression between these groups (Supplemental Figure 1). Similarly, miRNA expression data demonstrated a significant decrease in expression of the miR-133a in hearts after MI when compared to control (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Measurement of miR-133a levels by qRT-PCR in an in vivo rat MI Model.

qRT-PCR data from rat hearts subjected to ischemia and reperfusion showed a significant decrease in miR-133a at one and four weeks following MI. p<0.05 compared to untreated control (n=3 hearts/group).

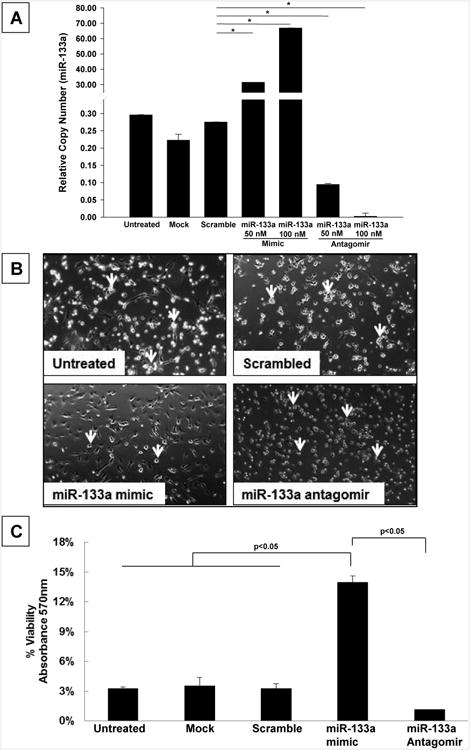

Dose-dependent increase in miR-133a levels by miR-133a mimic in MSCs and increased cell viability

MSCs were transfected with two different doses (50 nM & 100 nM) of miR-133a mimic or inhibitors. There was a dose dependent increase in miR-133a levels in MSCs at 24 hrs post transfection. In contrast, transfection of MSCs with miR-133a antagomir (50 nM & 100 nM) significantly reduced the level of miR-133a (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Measurement of miR-133a levels in MSCs transfected with miR-133a mimic or antagomir by qRT-PCR. MSCs transfected with miR-133a (100 nM) showed significant increase in miR-133a levels and MSCs transfected with miR-133a antagomir (100 nM) completely blocked miR-133a levels (B) Phase contrast images of MSCs following glucose and serum deprivation at 12 hours show increased cell death (yellow arrows) in untreated, scramble and miR-133a antagomir MSCs On the other hand decreased cell death was observed in MSCs transfected with miR-133a. (C) MTT assay showed significant increase in cell survival in miR-133a mimic transfected group compared to scramble or mock transfected groups. A value of p<0.05 was considered to be significant (n=3/group).

MSCs transfected with miR-133a mimic or inhibitor (100 nM) were cultured for 12 hours under glucose and FBS-free DMEM medium to simulate ischemic injury to the cells. Phase contrast images were acquired to assess the cell morphology after ischemic exposure of MSCs with or without miRNA transfection (Figure 2B). The cell viability of miR-133a mimic or inhibitor (100 nM) transfected MSCs were compared to untreated, scrambled and miR-133a antagomir transfected cells at 12 hours following glucose and serum derivation by the MTT assay as described previously (31). MSCs transfected with miR-133a-mimic had a significant increase in cell survival, when compared to untreated, scrambled and miR-133a-antagomir transfected MSCs (Figure 2C). This data demonstrates the potential cytoprotective effects of miR-133a mimic transfection on MSCs under simulated ischemic conditions.

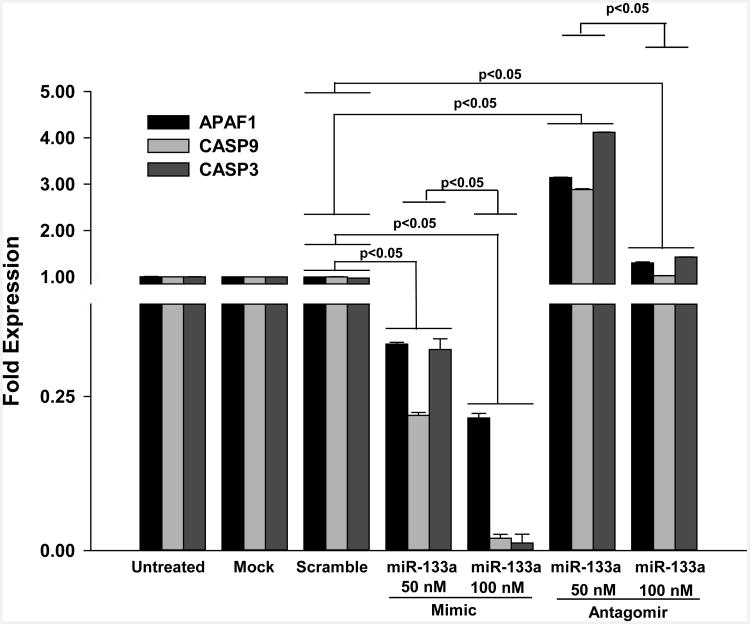

miR-133a mimic transfection down regulates Apaf-1, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 expression in MSCs in-vitro

Our data further confirmed the ability of miR-133a to attenuate Caspase-9 and Caspases-3 expression levels under simulated ischemic conditions (Figure 3). Furthermore, we observed a novel upstream potential target for miR-133a. Our results showed a significant decrease in the expression of apoptotic protease activating factor-1(Apaf-1), an upstream regulator of Caspase-9 and Caspase-3. Additionally, MSCs transfected with miR-133a mimic showed a significant decrease in Apaf-1, Capase-9 and Caspase-3 mRNA levels. Contrary to this gene expression, miR-133a antagomir transfection led to a significant increase in Apaf-1, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 transcription level. These transcription levels demonstrated that miR-133a mimic transfection in MSCs likely has an anti-apoptotic effect via repression of the main component in the intrinsic mitochondia apoptotic pathway (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Measurement of Apaf-1, Caspase 9 and Caspase3 levels in MSCs with miR-133a mimic or antagomir.

qRT-PCR data showed a dose dependent decrease in fold expression of APAF-1, Caspase-9 (CASP9) and Caspase-3 (CASP3) in MSCs transfected with 50 nM & 100 nM of miR-133a mimic under simulated ischemic conditions. In contrary, there was a significant increase in these genes in MSCs transfected with miR-133a antagomir. A value of p<0.05 was considered to be significant (n=3/group).

Transplantation of miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs improves cardiac function

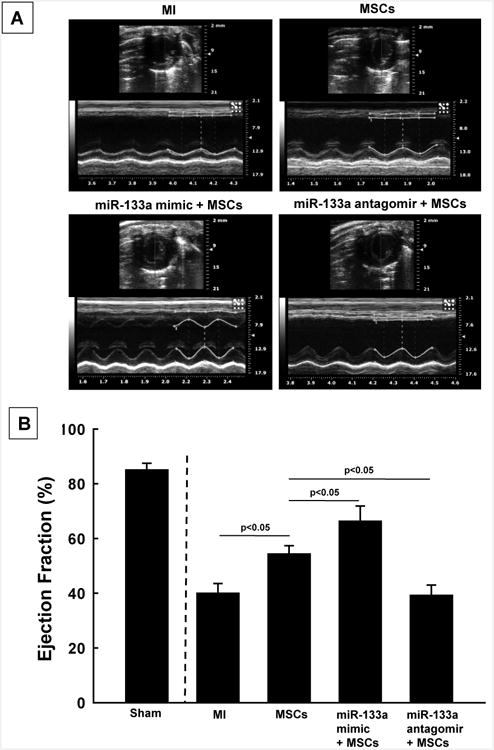

Assessment of cardiac function was performed by ultrasound echocardiography (M-mode) at one week after MI (Figure 4A). The results showed a significant improvement in cardiac function in hearts transplanted with miR-133a-mimic transfected MSCs, as compared to MSCs alone or MI treated groups. On the other hand knock-down of miR-133a in MSCs by its antagomir blunted the beneficial effect of miR-133a leading to decreased cardiac function (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Assessment of cardiac function at 1 week after MI in miR-133a mimic + MSCs transplanted hearts.

(A) Representative M-mode ultrasound echocardiography images in different groups at one-week after MI. (B) Significant improvement in ejection fraction was observed in miR-133a mimic + MSCs treated group compared to MSC-alone group. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n=6 hearts/group). A value of p<0.05 was considered to be significant.

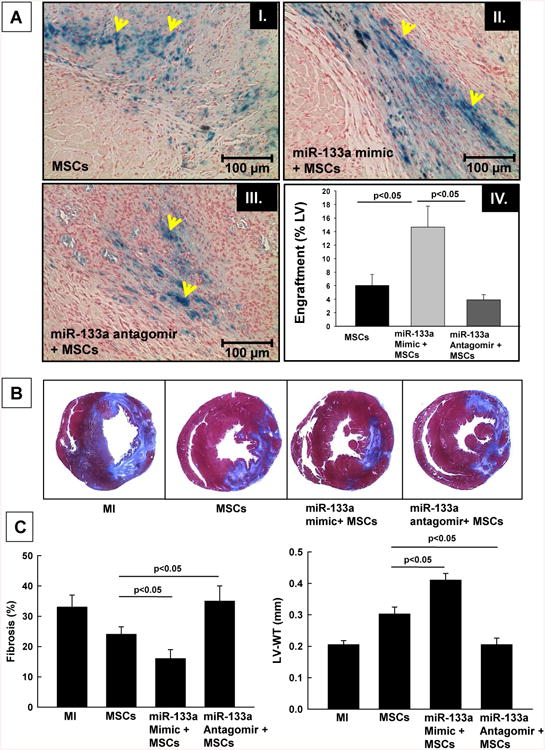

Increased cell engraftment and decreased infarct size of miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs in vivo

The engraftment of MSCs was assessed by Prussian blue staining of iron oxide labeled MSCs as described previously (29). Our results showed significant increase in cell engraftment in MSCs transfected with miR-133a mimic group, when compared with untreated or miR-133a antagomir transfected MSCs (Figure 5A). Transplantation of miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs in the ischemic heart led to a significant decrease in myocardial infarction and an improvement in left-ventricular (LV) wall thickness at one-week after MI, when compared to the MSCs-alone treated group (Figure 5B). In contrast, knock-down of miR-133a in MSCs with its antagomir led to a significant increase in cardiac fibrosis and thinning of the LV-wall (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Assessment of MSCs engraftment in the heart.

(A) MSCs labeled with SPIO, were identified in the heart sections at one week after transplantation by Prussian blue staining. Prussian-blue staining showing engraftment of SPIO-labeled cells (Blue color, Black arrows) in the infarct heart. The bar graph indicates a quantification of engrafted MSCs. There was a significant increase in MSCs engraftment in the miR-133a + MSCs group, when compared to the MSCs or miR-133a antagomir + MSCs groups (p<0.05 vs MSCs group, n=4/group). (B) Masson-trichrome staining was performed for measurement of infarct size or fibrosis and (C) LV % fibrosis and left ventricular wall thickness (LV-WT) are shown for infarcted hearts; MI, MSCs and MSCs+miR-133a treated groups. Infarct size, % fibrosis and LV wall thickness were all improved in the miR-133a + MSCs group. All values are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3 hearts/group). A value of p<0.05 was considered to be significant.

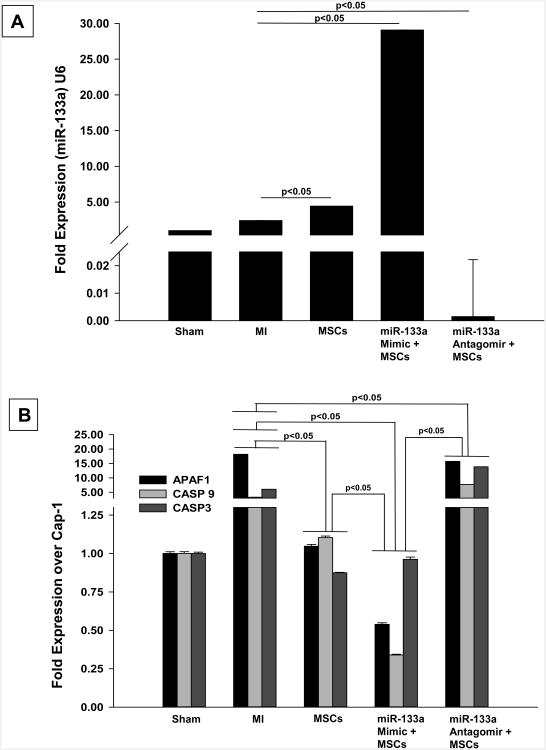

Transplantation of miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs increases miR-133a levels and down regulates Apaf-1 and Caspase-3 expression in the infarcted heart

At one week after MI and stem cell transplantation, qRT-PCR data showed a significant increase in miR-133a levels in the hearts transplanted with miR-133a mimic MSCs. This increase was blunted in hearts transplanted with miR-133a antagomir transplanted group (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Measurement of miR-133a levels and gene expression in the heart following MI.

(A) qRT-PCR data shows increase in miR-133a levels in the infarcted heart at one week after MI in miR-133a mimic MSCs transfected group. (B) qRT-PCR data shows repression of Apaf-1, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 gene expression at one week following MI in miR-133a mimic MSCs transplanted hearts. All values are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3 hearts/group). A value of p<0.05 was considered to be significant.

To further understand the molecular mechanism of miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs in cardioprotection, we performed additional experiments to measure the mRNA expression levels of Apaf-1, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 in miR-133a-mimic transfected MSCs that were transplanted in the hearts. The results showed a several-fold increase in expression of Apaf-1, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 in MI-untreated hearts compared to sham animals (Figure 6B). In contrary, transplantation of miR-133a-mimic transfected MSCs into the ischemic heart led to a significant reduction in pro-apoptotic Apaf-1, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 expression compared with the MI group. Apaf-1 and Caspase 9, but not Caspase 3 expression were significantly decreased compared with the MSCs only group (Figure 6B). Additionally, transplantation of miR-133a-antagomair transfected MSCs blunted the protective effect of miR-133a by increasing the mRNA expression of Apaf-1, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3. These results indicate that miR-133a is protective due to its role in repressing apoptotic genes and decreasing apoptosis.

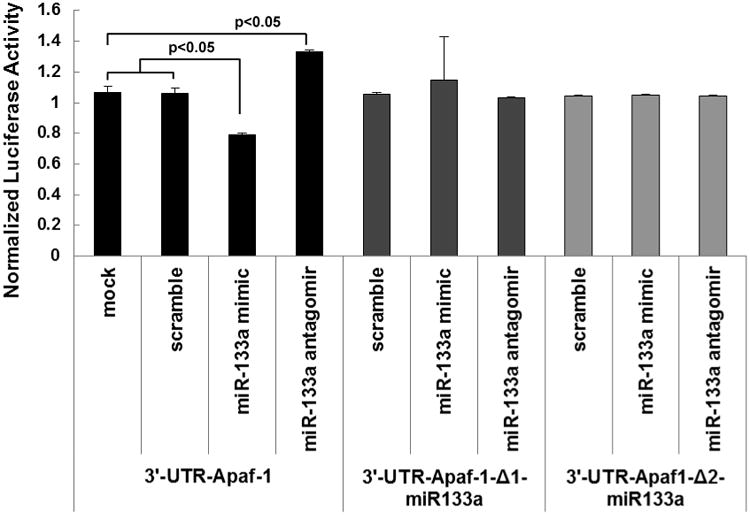

Luciferase reporter assay shows miR-133a is a direct target for Apaf-1

Our data suggested that miR-133a targets Apaf-1 and decreases its expression (Figure 7). To test our hypothesis whether miR-133a is involved directly in the suppression of Apaf-1, the 3′UTR of Apaf-1 and 2 mutated binding sites of miR-133a in the 3′UTR were cloned into luciferase reporter vector separately (Supplemental Figure 2). To determine the changes in luciferase activity, cells were transfected with the miR-133a mimic, antagomir and scrambled miRNAs and tested for luciferase production/ activity measured by photocytometer. We observed decreased expression of the luciferase activity when 3′UTR of Apaf-1 unmutated construct was transfected with miR-133a mimic. On the other hand, we noticed enhancement in the luciferase activity in 3′UTR of Apaf-1 construct transfected with miR-133a antagomir. We failed to detect any changes in luciferase activity of the mutated construct (Del1 and Del2), when transfected with miR-133a mimic, antagomir or scrambled miRNA. Our luciferase reporter assay data strongly supports and confirms our hypothesis that miR-133a is a direct target for Apaf-1 and represses its expression.

Figure 7. Luciferase reporter assay confirming miR-133a as a direct target for Apaf-1.

Luciferase assay was done by co-transfecting 293 cells with miR-133a mimic, antagomir or scramble and 3′UTR of Apaf-1 or mutated Apaf-1-3′UTR (Del1 and Del2; represented by Δ 1 & 2) and then subjected to luciferase reporter assay to measure gene activity. The intensity of the firefly luciferase in the cells co-transfected with miR-133a mimic and Apaf-1-3′UTR was lower when compared with scramble miRNA transfection. On the other hand, co-transfection with miR-133a antagomir lead to increased luciferase activity. However, miR-133a mimic or antagomir has no effect on the luciferase activity in the mutated Apaf-1- 3′UTR (Del-1 and Del-2; represented by Δ 1 & 2) transfection groups. All values are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3/group), p<0.05 vs scrambled or miR-133a antagomir groups.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate the use of miR-133a mimic transfection to enhance the survivability of MSCs in the infarcted heart. Our study has established that one mechanism by which miR-133a improves stem cell survival in the ischemic heart is by attenuating the mRNA expression of Apaf-1 and Caspase-9, which in turn leads to decreased cell apoptosis, improved cardiac function and decreased cardiac fibrosis. Recent studies have revealed multiple functions of miRNAs in cardiac biology (21, 34, 35) including: the control of myocyte growth (23), contractility (36), fibrosis (26) and angiogenesis (37). An improved understanding of miRNAs is providing an expanded view of new regulatory mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets for heart disease. To date the limited clinical success of cardiomyoplasty, demonstrates the need for further work to ensure widespread applicability of this treatment to mitigate heart failure in patients following acute MI. While cardiomyoplasty using MSCs is not a new approach, its use is limited due to the survival of implanted cells.

miRNAs typically act as inhibitors of gene expression especially in the disease state of MI. The miRNAs which are down regulated in patients with MI are miR-1 and miR-133a, when compared to healthy hearts (38). Our results are in agreement with these findings and our data demonstrated a similar decrease in miR-1 and miR-133a expression levels in the rat hearts at 1 and 4 weeks post-MI. We hypothesized that an increase in the in vivo levels of the specific miRNA in question (i.e. miR-133a) would possess a therapeutically beneficial effect. In support of this hypothesis in vivo, it has been shown that infusion of miR-9 mimic could attenuate isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy and ameliorate cardiac dysfunction, in part through the regulation of the miR-9 target, myocardin (39). While this method would supplement the miRNA levels lost during disease progression, it could also result in potential off target effects given that the infused mimic could also be taken up by tissues that do not normally express the miRNA of interest. To circumvent this potential problem, we have delivered miRNA mimics in a cardiac-specific manner by transfecting MSCs with specific miRNAs that are under-expressed in the infarcted heart (i.e. miR-133a). The miRNA engineered MSCs are then transplanted into the diseased heart tissue in an effort to decrease apoptosis of the transplanted cells and improve recovery of global cardiac function.

Recently, it has been shown that miR-1 and miR-133 play a crucial role in myocardial ischemic-reperfusion (IR) injury and ischemic preconditioning by regulating apoptosis related genes (40). He et al. showed that injecting miR-133a mimic or antagomir into the heart before IR injury provides cardioprotection by decreasing Bax and Caspase-9, which are involved in regulating apoptosis. Furthermore, it also demonstrated decreased cardiomyocyte apoptosis by TUNEL and annexin-V staining. Similarly, our results demonstrated that transplantation of miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs decreased Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 in the heart tissue one week after transplantation, when compared to MI. However, the novelty of our study lies in our demonstration that by transfecting MSCs with miR-133a, the delivery of miR-133a in the ischemic tissue may be prolonged thereby further improving the survival of cardiomyocytes in the inhospitable ischemic microenvironment of the infarcted heart. In another study, Hu et al. has shown that a pro-survival cocktail of miRNAs containing miR-21, miR-24 and miR-221 can improve the engraftment of transplanted cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) in the infarcted heart (41). It also indicated increased survival of CPCs, improved cardiac function and decreased cardiac fibrosis. Our current study demonstrated similar findings that MSCs transfected with miR-133a mimic had improved cardiac function recovery and decreased cardiac fibrosis. On the other hand, blockade of miR-133a in MSCs by an antagomir severely blunted the positive effects of miR-133a leading to decreased cardiac function and increased cardiac fibrosis. The results from our work clearly demonstrate the cardioprotective benefits of delivering miR-133a mimic into the ischemic heart.

Apoptosis is mediated by caspases activation, which are made in inactive zymogens that need to be activated to function (42). In general, activation of caspases includes two major pathways: A) extrinsic cell surface death pathway (43, 44) and B) the intrinsic mitochondia pathway. The latter is regulated by Bcl-2 family and is triggered by stress, which cause the release of proapoptotic signals such as cytochrome c, which interacts with an adaptor protein, apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (Apaf-1), which initiates Apaf-1 oligomerization and apoptosome formation to recruit and activate Caspase-9 (45, 46). Active Caspase-9 then processes exterior caspases like caspase-3 to complete apoptotic porcesses (47), However, its inhibtion by Apaf-1 inhibitors leads to decreased apoptosis of cardiomyocytes under hypoxic conditions (48). Another study showed that neonatal cardiomyocytes treated with taurine and subjected to simulated ischemia leads to supressed formation of the Apaf-1/Caspase-9 apoptosome. The interation of Caspase-9 with Apaf-1 also demonstrated that taurine can effectively decrease myocaridal ischemia-induced apotosis by inhibiting the assembly of the Apaf-1/caspase-9 apoptosome (49).

Interestingly, both our in-vitro and in-vivo studies demonstrated that Apaf-1 is an upstream regulator of caspase-9 and caspase-3 and it is being regulated by miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs. Transplantation of miR-133a mimic transfected MSCs led to a significant decrease in the mRNA expression of Apaf-1, caspase-9 and caspase-3. In contrast, depleting or blocking miR-133a by its antagomir in MSCs led to enhanced expression of these transcripts (Supplemental Figure 3). Further, our luciferase reporter assay data showed a decreased luciferase activity in miR-133a mimic transfected cells. In contrary, enhancement in the luciferase activity was observed in miR-133a antagomir transfected cells. miR-133a mimic/antagomir has no effect on luciferase activity in the cells transfected with mutated Apaf-1 3′ UTR. This data suggests that miR-133a is a direct target for Apaf-1. This novel reprogramming of stem cells by miR-133a mimic may enhance the clinical usefulness of stem cells by decreasing apoptosis of transplanted cells and improve the efficacy of transplanted stem cells for cardiomyoplasty applications in future.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Hierarchical clustering of miRNAs expression in the infarcted heart. Rat hearts subjected to MI by temporary ligation of LAD, were collected at baseline and at different time points after MI. Heat map by hierarchical clustering method were used to display the top differentially expressed miRNAs and their expression patterns. Heat-map data shows down-regulation of important cardiac muscle specific like miR-1 and miR-133a in the heart after MI.

Supplemental Figure 2: miR-133a target prediction. Using microRNA prediction tool from Segal lab of computational science allowed us to run the PITA algorithm on Apaf-1- 3′UTRs and miR-133a. PITA starts by scanning the UTR for potential microRNA targets (using the supplied seed matching tools) and then scores each site. This parameter-free model for miRNA-target interaction computes the difference between the free energy gained from the formation of the microRNA-target duplex and the energetic cost of unpairing the target to make it accessible to the microRNA. This model explains predicts validated targets more accurately than existing algorithms, and shows that genomes accommodate site accessibility by preferentially positioning targets in highly accessible regions. The model showed two predicted site of miR-133a in the Apaf-1-3′UTR at position 122 and 687 highlighted in Red. These sites were mutated individually to create Del1 and Del2, respectively.

Supplemental Figure 3: Schematic representation of the role of Apaf-1 in induction of apoptosis. miR-133a mimic blocks Apaf-1 and thereby inhibits cellular apoptosis and improves cell survival. On the other hand, miR-133a antagomir enhances Apaf-1 expression and induces cellular death.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Valerie P. Wright for help with SigmaPlot data analysis. A part of this project was supported by Award Number Grant UL1TR001070 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

List of Abbreviations

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- IR

Ischemia-reperfusion

- CHF

Congestive heart failure

- LAD

Left anterior descending

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

- Apaf-1

Apoptosis activating factor 1

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

Footnotes

Statement of author contributions: Conceived and designed the experiments: DD MK; Performed the experiments: DD MK; Analyzed the data: DD, JZ, LY, MK; Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: CM MA MK; Wrote the paper: DD MA MK

Disclosure and Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011 Aug 26;59(8):1–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2014 Jan 21;129(3):e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agbulut O, Vandervelde S, Al Attar N, Larghero J, Ghostine S, Leobon B, Robidel E, Borsani P, Le Lorc'h M, Bissery A, Chomienne C, Bruneval P, Marolleau JP, Vilquin JT, Hagege A, Samuel JL, Menasche P. Comparison of human skeletal myoblasts and bone marrow-derived CD133+ progenitors for the repair of infarcted myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Jul 21;44(2):458–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Szabolcs MJ, Takuma S, Burkhoff D, Wang J, Homma S, Edwards NM, Itescu S. Neovascularization of ischemic myocardium by human bone-marrow-derived angioblasts prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis, reduces remodeling and improves cardiac function. Nat Med. 2001 Apr;7(4):430–6. doi: 10.1038/86498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P. Transplanted adult bone marrow cells repair myocardial infarcts in mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001 Jun;938:221–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03592.x. discussion 9-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pagani FD, DerSimonian H, Zawadzka A, Wetzel K, Edge AS, Jacoby DB, Dinsmore JH, Wright S, Aretz TH, Eisen HJ, Aaronson KD. Autologous skeletal myoblasts transplanted to ischemia-damaged myocardium in humans. Histological analysis of cell survival and differentiation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003 Mar 5;41(5):879–88. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tse HF, Kwong YL, Chan JK, Lo G, Ho CL, Lau CP. Angiogenesis in ischaemic myocardium by intramyocardial autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell implantation. Lancet. 2003 Jan 4;361(9351):47–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, Schwartz RE, Keene CD, Ortiz-Gonzalez XR, Reyes M, Lenvik T, Lund T, Blackstad M, Du J, Aldrich S, Lisberg A, Low WC, Largaespada DA, Verfaillie CM. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002 Jul 4;418(6893):41–9. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toma C, Pittenger MF, Cahill KS, Byrne BJ, Kessler PD. Human mesenchymal stem cells differentiate to a cardiomyocyte phenotype in the adult murine heart. Circulation. 2002 Jan 1;105(1):93–8. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shake JG, Gruber PJ, Baumgartner WA, Senechal G, Meyers J, Redmond JM, Pittenger MF, Martin BJ. Mesenchymal stem cell implantation in a swine myocardial infarct model: engraftment and functional effects. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002 Jun;73(6):1919–25. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03517-8. discussion 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Khaldi A, Al-Sabti H, Galipeau J, Lachapelle K. Therapeutic angiogenesis using autologous bone marrow stromal cells: improved blood flow in a chronic limb ischemia model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003 Jan;75(1):204–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K, Leri A, Kajstura J, Nadal-Ginard B, Anversa P. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003 Sep 19;114(6):763–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuramochi Y, Fukazawa R, Migita M, Hayakawa J, Hayashida M, Uchikoba Y, Fukumi D, Shimada T, Ogawa S. Cardiomyocyte regeneration from circulating bone marrow cells in mice. Pediatric research. 2003 Sep;54(3):319–25. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000078275.14079.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, Pickel J, McKay R, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001 Apr 5;410(6829):701–5. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002 Apr 30;12(9):735–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aghabozorg Afjeh SS, Ghaderian SM. The role of microRNAs in cardiovascular disease. International journal of molecular and cellular medicine. 2013 Spring;2(2):50–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garofalo M, Condorelli G, Croce CM. MicroRNAs in diseases and drug response. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2008 Oct;8(5):661–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meder B, Katus HA, Rottbauer W. Right into the heart of microRNA-133a. Genes Dev. 2008 Dec 1;22(23):3227–31. doi: 10.1101/gad.1753508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bostjancic E, Zidar N, Stajer D, Glavac D. MicroRNAs miR-1, miR-133a, miR-133b and miR-208 are dysregulated in human myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 115(3):163–9. doi: 10.1159/000268088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye Y, Perez-Polo JR, Qian J, Birnbaum Y. The role of microRNA in modulating myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol Genomics. 2011 May 1;43(10):534–42. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00130.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatsuguchi M, Seok HY, Callis TE, Thomson JM, Chen JF, Newman M, Rojas M, Hammond SM, Wang DZ. Expression of microRNAs is dynamically regulated during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007 Jun;42(6):1137–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villar AV, Merino D, Wenner M, Llano M, Cobo M, Montalvo C, Garcia R, Martin-Duran R, Hurle JM, Hurle MA, Nistal JF. Myocardial gene expression of microRNA-133a and myosin heavy and light chains, in conjunction with clinical parameters, predict regression of left ventricular hypertrophy after valve replacement in patients with aortic stenosis. Heart (British Cardiac Society) Jul;97(14):1132–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.220418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sayed D, Hong C, Chen IY, Lypowy J, Abdellatif M. MicroRNAs play an essential role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2007 Feb 16;100(3):416–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257913.42552.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu N, Bezprozvannaya S, Williams AH, Qi X, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. microRNA-133a regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and suppresses smooth muscle gene expression in the heart. Genes Dev. 2008 Dec 1;22(23):3242–54. doi: 10.1101/gad.1738708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, Bang ML, Segnalini P, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Elia L, Latronico MV, Hoydal M, Autore C, Russo MA, Dorn GW, 2nd, Ellingsen O, Ruiz-Lozano P, Peterson KL, Croce CM, Peschle C, Condorelli G. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2007 May;13(5):613–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matkovich SJ, Wang W, Tu Y, Eschenbacher WH, Dorn LE, Condorelli G, Diwan A, Nerbonne JM, Dorn GW., 2nd MicroRNA-133a protects against myocardial fibrosis and modulates electrical repolarization without affecting hypertrophy in pressure-overloaded adult hearts. Circ Res. 2010 Jan 8;106(1):166–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.202176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duisters RF, Tijsen AJ, Schroen B, Leenders JJ, Lentink V, van der Made I, Herias V, van Leeuwen RE, Schellings MW, Barenbrug P, Maessen JG, Heymans S, Pinto YM, Creemers EE. miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ Res. 2009 Jan 30;104(2):170–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535. 6p following 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassan F, Meduru S, Taguchi K, Kuppusamy ML, Mostafa M, Kuppusamy P, Khan M. Carvedilol enhances mesenchymal stem cell therapy for myocardial infarction via inhibition of caspase-3 expression. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012 Oct;343(1):62–71. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.196915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan M, Meduru S, Gogna R, Madan E, Citro L, Kuppusamy ML, Sayyid M, Mostafa M, Hamlin RL, Kuppusamy P. Oxygen cycling in conjunction with stem cell transplantation induces NOS3 expression leading to attenuation of fibrosis and improved cardiac function. Cardiovascular research. 2012 Jan 1;93(1):89–99. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dakhlallah D, Batte K, Wang Y, Cantemir-Stone CZ, Yan P, Nuovo G, Mikhail A, Hitchcock CL, Wright VP, Nana-Sinkam SP, Piper MG, Marsh CB. Epigenetic regulation of miR-17∼92 contributes to the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013 Feb 15;187(4):397–405. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0888OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wisel S, Khan M, Kuppusamy ML, Mohan IK, Chacko SM, Rivera BK, Sun BC, Hideg K, Kuppusamy P. Pharmacological preconditioning of mesenchymal stem cells with trimetazidine (1-[2,3,4-trimethoxybenzyl]piperazine) protects hypoxic cells against oxidative stress and enhances recovery of myocardial function in infarcted heart through Bcl-2 expression. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009 May;329(2):543–50. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.150839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Statistical applications in genetics and molecular biology. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunter MP, Ismail N, Zhang X, Aguda BD, Lee EJ, Yu L, Xiao T, Schafer J, Lee ML, Schmittgen TD, Nana-Sinkam SP, Jarjoura D, Marsh CB. Detection of microRNA expression in human peripheral blood microvesicles. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(11):e3694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikeda S, Kong SW, Lu J, Bisping E, Zhang H, Allen PD, Golub TR, Pieske B, Pu WT. Altered microRNA expression in human heart disease. Physiol Genomics. 2007 Nov 14;31(3):367–73. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00144.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sucharov C, Bristow MR, Port JD. miRNA expression in the failing human heart: functional correlates. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008 Aug;45(2):185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim GH, Samant SA, Earley JU, Svensson EC. Translational control of FOG-2 expression in cardiomyocytes by microRNA-130a. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang S, Aurora AB, Johnson BA, Qi X, McAnally J, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. The endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev Cell. 2008 Aug;15(2):261–71. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bostjancic E, Zidar N, Stajer D, Glavac D. MicroRNAs miR-1, miR-133a, miR-133b and miR-208 are dysregulated in human myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 2010;115(3):163–9. doi: 10.1159/000268088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang K, Long B, Zhou J, Li PF. miR-9 and NFATc3 regulate myocardin in cardiac hypertrophy. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010 Apr 16;285(16):11903–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.098004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He B, Xiao J, Ren AJ, Zhang YF, Zhang H, Chen M, Xie B, Gao XG, Wang YW. Role of miR-1 and miR-133a in myocardial ischemic postconditioning. Journal of biomedical science. 2011;18:22. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-18-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu S, Huang M, Nguyen PK, Gong Y, Li Z, Jia F, Lan F, Liu J, Nag D, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Novel microRNA prosurvival cocktail for improving engraftment and function of cardiac progenitor cell transplantation. Circulation. 2011 Sep 13;124(11 Suppl):S27–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.017954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. Caspases: intracellular signaling by proteolysis. Cell. 1997 Nov 14;91(4):443–6. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Green DR, Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science. 2004 Jul 30;305(5684):626–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1099320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo X, Budihardjo I, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. Bid, a Bcl2 interacting, protein mediates cytochrome c release from mitochondria in response to activation of cell surface death receptors. Cell. 1998 Aug 21;94(4):481–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reubold TF, Wohlgemuth S, Eschenburg S. Crystal structure of full-length Apaf-1: how the death signal is relayed in the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Structure. 2011 Aug 10;19(8):1074–83. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan S, Akey CW. Apoptosome structure, assembly, and procaspase activation. Structure. 2013 Apr 2;21(4):501–15. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu Y, Benedict MA, Ding L, Nunez G. Role of cytochrome c and dATP/ATP hydrolysis in Apaf-1-mediated caspase-9 activation and apoptosis. The EMBO journal. 1999 Jul 1;18(13):3586–95. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mondragon L, Orzaez M, Sanclimens G, Moure A, Arminan A, Sepulveda P, Messeguer A, Vicent MJ, Perez-Paya E. Modulation of cellular apoptosis with apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1) inhibitors. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2008 Feb 14;51(3):521–9. doi: 10.1021/jm701195j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takatani T, Takahashi K, Uozumi Y, Matsuda T, Ito T, Schaffer SW, Fujio Y, Azuma J. Taurine prevents the ischemia-induced apoptosis in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes through Akt/caspase-9 pathway. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2004 Apr 2;316(2):484–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Hierarchical clustering of miRNAs expression in the infarcted heart. Rat hearts subjected to MI by temporary ligation of LAD, were collected at baseline and at different time points after MI. Heat map by hierarchical clustering method were used to display the top differentially expressed miRNAs and their expression patterns. Heat-map data shows down-regulation of important cardiac muscle specific like miR-1 and miR-133a in the heart after MI.

Supplemental Figure 2: miR-133a target prediction. Using microRNA prediction tool from Segal lab of computational science allowed us to run the PITA algorithm on Apaf-1- 3′UTRs and miR-133a. PITA starts by scanning the UTR for potential microRNA targets (using the supplied seed matching tools) and then scores each site. This parameter-free model for miRNA-target interaction computes the difference between the free energy gained from the formation of the microRNA-target duplex and the energetic cost of unpairing the target to make it accessible to the microRNA. This model explains predicts validated targets more accurately than existing algorithms, and shows that genomes accommodate site accessibility by preferentially positioning targets in highly accessible regions. The model showed two predicted site of miR-133a in the Apaf-1-3′UTR at position 122 and 687 highlighted in Red. These sites were mutated individually to create Del1 and Del2, respectively.

Supplemental Figure 3: Schematic representation of the role of Apaf-1 in induction of apoptosis. miR-133a mimic blocks Apaf-1 and thereby inhibits cellular apoptosis and improves cell survival. On the other hand, miR-133a antagomir enhances Apaf-1 expression and induces cellular death.