Abstract

Background

Spouses of cancer survivors experience both positive and negative effects from caregiving. However, it is less clear what role spousal well-being may have on cancer survivors. This study aimed to determine the impact of spousal psychosocial factors on survivor depressed mood and whether this association differed by gender.

Methods

We examined longitudinal data on cancer survivors and their spouses (n=910 dyads) from the 2004-2012 Medical Expenditures Panel Survey and a matched sample of cancer-free dyads. Subjects reported depressed mood, psychological distress, and mental and physical health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at two time points (T1/T2). Dyadic multilevel models evaluated the impact of psychosocial factors at T1 on depressed mood at T2, controlling for sociodemographics, cancer type, survivor treatment status, and depressed mood at T1.

Results

Cancer survivors whose spouses reported depressed mood at T1 were 4.27 times more likely to report depressed mood at T2 (95% CI=2.01-9.07); this was stronger for female survivors (OR=9.49; 95% CI=2.42-37.20). Better spousal mental and physical HRQoL at T1 were associated with a 30% decrease in survivor depressed mood risk at T2. Most spillover effects were not observed in comparison dyads.

Conclusion

Depressed mood and poor HRQoL in spouses may increase the risk of depressed mood in cancer survivors. The risk may be especially strong for female survivors.

Impact

Identifying and improving spousal mental health and HRQoL problems may reduce the risk of depressed mood in cancer survivors. Future research should examine whether incorporating spousal care into psycho-oncology and survivorship programs improves survivor outcomes.

Keywords: dyad, dyadic, actor-partner interdependence model, caregiver, survivor, cancer, depression, MEPS

INTRODUCTION

A substantial proportion of patients with cancer experience depressed mood at some point during their illness (1-3). While the prevalence of depressed mood decreases with time after diagnosis, a subset of the population continues to experience depressive symptoms (4) or poor quality of life (5), even well after treatment has been completed (5-7). Depressed mood in patients with cancer and survivors is associated with worse treatment adherence (8-10) and a range of poor health outcomes including decreased quality of life (11-15), shorter survival time (16), and premature mortality (17-19). As a result, the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends that health care practitioners screen cancer survivors for depressed mood and anxiety throughout the care trajectory (20).

Family members and spouses often provide psychological, financial, and functional support to cancer survivors. However, families of patients are also adversely impacted by a cancer diagnosis. Family caregivers experience worse quality of life and greater anxiety or depressed mood than non-caregivers or normative samples (21, 22), especially during the treatment (23) and palliative or end-of-life (24-26) phases, or when the survivor continues to have care needs during the survivorship phase (27). Such caregivers may develop diverse health problems over time (22, 28, 29). Spouses, in particular, often experience greater burden, strain, or distress than other family caregivers (26, 30), which may amplify their risk of adverse health outcomes (31, 32).

Patients and their partners or caregivers are interdependent and mutually influence one another (33). In particular, the system-transactional model of coping posits that dyadic stressors, such as a cancer diagnosis, can influence partners directly (via the acute stress of diagnosis, treatment and after-effects, for example) and indirectly, when the stress of one partner spills over to impact both (34). This is also reflected in other theories (e.g., emotional contagion theory and the life course concept of linked lives), which suggest that major life events and emotional states can transmit among family members (35-37). Such associations have been borne out in the general population – for example, high levels of depressive symptoms in husbands predict subsequent elevated levels of depressive symptoms in their wives (38) – but inadequately studied in cancer survivors and their spouses. From this perspective, caring for a family member with cancer may be a stressor that contributes to the onset or exacerbation of caregivers’ depressive symptoms – either directly, via a diffusion of the risk to the patient influencing caregiver or partner well-being, or indirectly, via a diffusion of stress or affect from one spouse to another – which in turn may adversely influence survivor well-being.

Recent review papers have demonstrated the need for further study of the reciprocal influence of patients with cancer and their caregivers or spouses (referred to hereafter as “spillover”) (39, 40). In most existing studies, small, convenience-based samples and cross-sectional designs have limited the generalizability and interpretation of findings. Further, evidence in the general population suggests gender differences in the impact of spousal psychosocial factors on depressed mood (38), although this has not be examined among cancer survivors. Using a national population-based sample, this study therefore sought to evaluate how quality of life and depressed mood were interrelated among cancer survivors and their spouses over time, and whether these associations differed by gender. In addition, we assessed whether this spillover was consistent with a matched sample of cancer-free dyads. Better understanding the interrelationship between cancer survivors and their spouses can help to inform optimal survivorship care and patient education to improve outcomes of cancer survivors and their families.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study used publically-available data from the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS). The MEPS is a nationally-representative sample of the civilian non-institutionalized population in the United States. Data are collected on each individual in sampled household at five time points (“Rounds”) over a two and a half-year period, with a new Panel of households beginning each year. Additional information about MEPS methodology and data can be obtained online (41). This study included complete data from Panels 9-16, collected between 2004 and 2012. In addition to baseline data (e.g., age, gender, and marital status), data from the self-administered questionnaire were used. This questionnaire was administered only in Rounds 2 and 4; for simplicity, we will refer to these as Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2) throughout the manuscript (11 months apart on average).

Identification of Cancer Survivors

We used the medical conditions file to identify adults who reported having a cancer-related health-problem, medical event or disability in Rounds 1 or 2 of the MEPS. Truncated three-digit International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes were generated from the respondent interview and aggregated using Clinical Classification Software. Adults with any type of cancer or malignancy were categorized as survivors, except those with only non-melanoma skin cancer.

Identification of Spouses

Survivors were linked to their spouses by a spousal identifier if they reported being married at Round 1. Only heterosexual couples were assigned spousal identifiers in the MEPS.

Eligibility

Cancer survivors and their spouse were eligible for this study if the spouse did not have a cancer-related health problem (including medical events or disabilities) and if both the survivor and spouse provided information at T1 and T2. For dwelling units in which more than one couple was identified, one couple was selected at random (n=2). We identified 1,284 eligible dyads. Dyads missing data on one or more covariates were dropped from the sample, resulting in a final sample size of 910 survivor-spouse dyads (71% of the eligible dyads). Those with missing data were older, more likely to be non-white or Hispanic or have low income, more likely to have public insurance/no insurance or need help with basic/instrumental activities of daily living (ADL/IADLs, described below), and had more education and worse psychosocial profiles (see Supplemental Table 1).

Identification of Comparison Dyads

Two comparison groups were identified by randomly selecting married individuals with complete spousal data, frequency matched to the cancer survivors on age and race-ethnicity; one group was matched to couples in which the wife had cancer (n=427), the other group was matched to couples in which the husband had cancer (n=483). Comparison dyads met the same identification and eligibility criteria as cancer dyads, with the exception that both spouses were free from cancer.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

Participant age, gender (coded as a dyad-level variable: female survivor or male survivor), race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic, other), insurance coverage (any private, public only, or uninsured), poverty status (<100%, 100%-<200%, 200%-<400%, or ≥400% of the federal poverty level), and family size were determined from the household component of the MEPS.

Health factors

Health conditions were defined as the number of MEPS priority conditions, excluding cancer, and dichotomized (0, 1+). The number of basic or instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., feeding oneself, e.g., buying groceries) with which the participant reported needing help (ADL/IADLs) was dichotomized (0, 1+). Cancer treatment status was evaluated from the medical conditions file. Survivors who received a prescription for an anti-neoplastic agent or received chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or surgery associated with their cancer were categorized as being “on treatment”. Type of cancer was categorized based on the most prevalent groups in this sample (blood, breast, colorectal, prostate, multiple, or unknown/other based on the ICD-9 codes assigned in the MEPS dataset). Treatment status and cancer type were coded as family-level variables, and applied to both the survivor and his or her spouse.

Depressed mood

Participants’ tendency towards depressed mood during the last two weeks was measured with the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) (42), which assessed the frequency of depressed mood and decreased interest in usual activities on a 4-point Likert scale (Not at all [0] to Nearly every day [3]). Items were summed and a score of 3 or greater was used to indicate depressed mood (42). This scale has acceptable criterion and construct validity for use as a blunt depression screener, with a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 90% and an area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of >0.90 (42). Cronbach’s alpha in our sample was 0.87 at T1 and 0.89 at T2, indicating good reliability.

Psychological Distress

Non-specific psychological distress during the last 30 days was measured using the Kessler-6 (K-6) (43). Participants rated the six items on a 5-point Likert scale (None of the time [0] to All of the time [4]). The items were summed to create a continuous variable ranging from 0-24. Higher scores indicated greater levels of distress. This scale has a ROC score of 0.88, indicating acceptable discrimination between cases and non-cases. Cronbach’s alpha in our sample was 0.90, indicating good-to-excellent reliability.

Quality of Life

The Short Form-12 (SF-12) version 2, a widely used measure of health status, was used to assess the overall mental and physical HRQoL of participants over the past month (44). The SF-12 has eight subscales that were condensed into physical and mental health component scores standardized to population norms (mean=50; standard deviation=10). Higher scores indicated better HRQoL. The physical and mental health components have a test-retest reliability of 0.89 and 0.76, respectively, and provide good discrimination of groups known to differ in physical and mental conditions (44). Cronbach’s alpha in our sample was 0.87, indicating good reliability.

Statistical Approach

Descriptive statistics were calculated as percentages and means with standard deviations. The characteristics of survivors and their spouses were compared using Wilcoxon and chi-squared tests; survivors and spouses with and without depressed mood were also compared. Correlations between spouses on psychosocial factors were calculated. Due to non-independence between spouses, binomial dyadic multilevel models with random intercepts were constructed following the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) framework; a two-intercept model was used (45). Specifically, these models examined the association between survivor and spousal psychosocial factors at T1 on both survivor and spousal depressed mood at T2, producing four estimates of interest: the actor effect of the spouse’s independent variable at T1 on his/her depressed mood at T2; the actor effect of the survivor’s independent variable at T1 on his/her depressed mood at T2; the partner effect of the spouse’s independent variable at T1 in the survivor’s depressed mood at T2; and the partner effect of the survivor’s independent variable at T1 on the spouse’s depressed mood at T2. In the multilevel framework, individuals were nested within dyads. Four independent variables (measured at T1) were considered in four separate models: 1) depressed mood; 2) distress; 3) mental HRQoL; and 4) physical HRQoL; depressed mood at T2 was the dependent variable in all models. All models controlled for sociodemographic characteristics, health factors, and depressed mood at T1. We then repeated the analysis, stratifying by cancer patient gender and assessing the comparison groups, with gender used as the distinguishing variable in the APIM models. SAS 9.3 was used for all analyses. Details of the APIM method used in this study are available in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the findings, stratifying by treatment status and dropping breast and prostate cancer, as breast and prostate cancer may confound the interpretation of the results stratified by survivor gender.

RESULTS

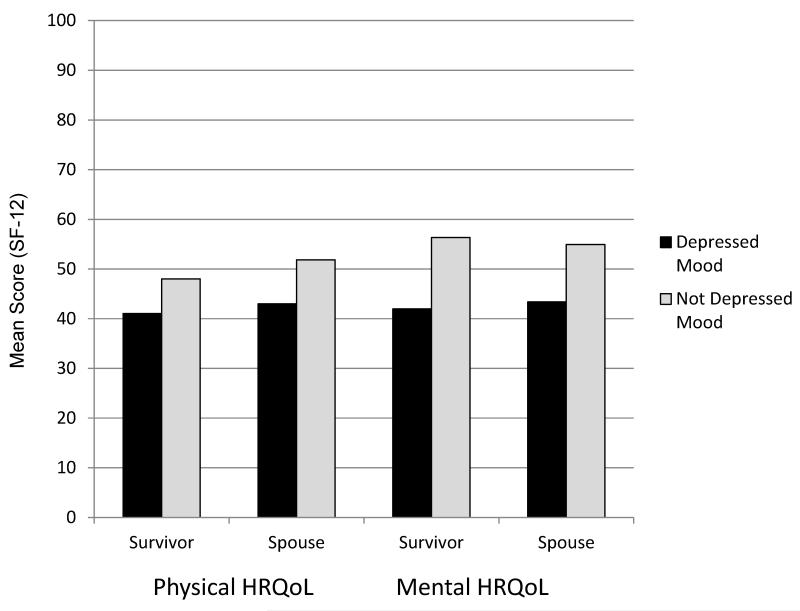

Cancer survivors had a mean age of 61 and were slightly older than their spouses (Table 1). Survivors were more likely to have health conditions (excluding cancer) and ADL/IADL limitations than their spouses. Survivors had slightly worse psychosocial profiles at both time points and were more likely to report depressed mood. Survivors and spouses reporting depressed mood had worse mental and physical HRQoL than their counterparts without depressed mood (Figure 1). Characteristics of the comparison dyads are presented in the Supplemental Material (Supplemental Table 2)

Table 1. Characteristics of Cancer Survivors and Their Spouses in the 2004-2012 MEPS.

| Survivors n=910 |

Spouses n=910 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | Range | Mean (SD) or % | Range | |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||

| Age* | 61.29 (13.69) | 22-85 | 60.44 (13.05) | 23-85 |

| Sex* | ||||

| Male | 53.1 | 46.9 | ||

| Female | 46.9 | 53.1 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 65.5 | 64.0 | ||

| Other | 34.5 | 36.0 | ||

| Insurance Status | ||||

| Any Private | 71.8 | 71.9 | ||

| Public Only | 23.5 | 21.3 | ||

| Uninsured | 4.7 | 6.8 | ||

| Education (Years) | 13.30 (3.02) | 0-17 | 13.22 (2.80) | 0-17 |

| % Poverty Line | ||||

| <100% | 7.9 | 7.8 | ||

| 100-<200% | 15.7 | 15.8 | ||

| 200-<400% | 29.2 | 29.0 | ||

| 400% or higher | 47.1 | 47.4 | ||

| Family Size | 2.67 (1.09) | 2-9 | 2.67 (1.09) | 2-9 |

| Health Factors | ||||

| Presence of ADLs/IADLs at T1* | 6.9 | 3.6 | ||

| Number of health conditionsa | ||||

| Mean (SD)α | 1.26 (1.74) | 0-10 | 1.14 (1.56) | 0-9 |

| 0 | 49.5 | 53.6 | ||

| 1+ | 50.6 | 46.4 | ||

| Cancer Characteristics | ||||

| Time Since Diagnosisb (years) | 6.55 (6.91) | 0-44 | ||

| Treatment Status | ||||

| Off Treatment | 67.6 | |||

| On Treatment | 32.4 | |||

| Type of Cancer | ||||

| Blood | 8.2 | |||

| Breast | 18.8 | |||

| Colorectal | 5.3 | |||

| Prostate | 21.1 | |||

| Multiple | 10.6 | |||

| Unknown/Other | 36.0 | |||

not including cancer;

Time since diagnosis only available on a subset of survivors (n=723)

p<0.10,

p<0.05 (Wilcoxon test accounting for non-independence, or chi-squared test)

SD: Standard deviation; T1: Time 1; ADL/IADL: Limitations in basic and/or instrumental activities of daily living

Figure 1.

Psychosocial characteristics of cancer survivors and their spouses in the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (2004-2012). Mean mental and physical health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of 910 cancer survivors and their spouses with and without depressed mood at Time 1, controlling for age, gender, race/ethnicity, health insurance coverage, % federal poverty level, family size, presence of health conditions (not including cancer) and limitations in activities of daily living or instrumental activities of daily living. P<0.05 for all survivor-spouse and depressed-non-depressed contrasts. HRQoL was measured using the Short-Form 12 (SF-12) and depressed mood was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2), with a cutpoint of 3.

Correlations between survivors’ and spouses’ mental and physical HRQoL, distress, and depressed mood ranged from .26 to .45 at the two time points, indicating medium non-independence and the appropriateness of the dyadic models. The within-participant correlations between depressed mood and distress, mental HRQoL, and physical HRQoL were all less than 0.35, indicating that these characteristics were not collinear and could be modeled together. Characteristics of participants by depressed mood and spousal status are available in the Supplemental Material (Supplemental Table 3).

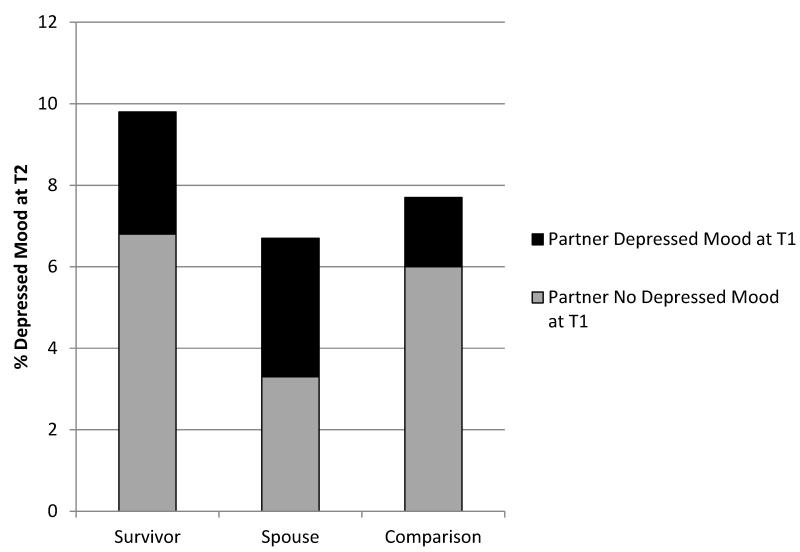

Figure 2 shows the prevalence and cross-tabulation of depressed mood in survivors and spouses and the combined comparison group at T2 and their partners at T1. Overall, the prevalence of depression at T2 was approximately 10% among survivors and 7% among their spouses; in the comparison dyads, the prevalence was approximately 8% (pchi-square=0.06 and 0.37, respectively). Four percent of survivors and 3% of spouses did not report depressed mood at T1, but did report depressed mood at T2. Three percent of survivors had depressed mood at T2 and had a spouse with depressed mood at T1.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of depressed mood in cancer survivors and their spouses, and a comparison group of spousal dyads without cancer (Medical Expenditures Panel Survey, 2004-2012). T1 and T2 were 11 months apart, on average.

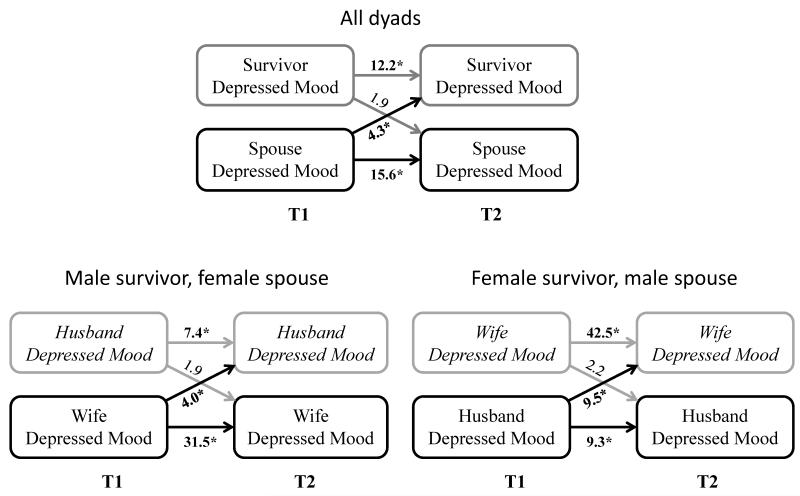

Table 2 and Figure 3 depict the actor and partner effects from the multivariable models (full models with estimates for all covariates are available in Supplemental Table 4).

Table 2. Actor-Partner effects of depression, quality of life and psychological distress on later depressed mood in couples with a cancer survivor, Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (2004-2012; n=910 dyads).

| 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Lower | Upper | p-value | |

| Depressed mooda | ||||

| Survivor-->Survivor | 12.17 | 6.56 | 22.55 | <.001 |

| Spouse-->Spouse | 15.64 | 7.49 | 32.68 | <.001 |

| Spouse-->Survivor | 4.27 | 2.01 | 9.07 | <.001 |

| Survivor-->Spouse | 1.88 | 0.87 | 4.07 | 0.108 |

| Distressb | ||||

| Survivor-->Survivor | 1.34 | 1.23 | 1.46 | <.001 |

| Spouse-->Spouse | 1.16 | 1.06 | 1.27 | 0.001 |

| Spouse-->Survivor | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.13 | 0.105 |

| Survivor-->Spouse | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.09 | 0.606 |

| Mental HRQoLc | ||||

| Survivor-->Survivor | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.44 | <.001 |

| Spouse-->Spouse | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.76 | <.001 |

| Spouse-->Survivor | 0.72 | 0.53 | 0.97 | 0.033 |

| Survivor-->Spouse | 0.75 | 0.55 | 1.02 | 0.072 |

| Physical HRQoLc | ||||

| Survivor-->Survivor | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.88 | 0.003 |

| Spouse-->Spouse | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.74 | <.001 |

| Spouse-->Survivor | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.87 | 0.002 |

| Survivor-->Spouse | 1.08 | 0.82 | 1.44 | 0.570 |

Estimates indicate likelihood of depressed mood at Time 2 for depressed versus not depressed mood at Time 1

Estimates indicate likelihood of depressed mood at Time 2 per 1 point difference in distress at Time 1

Estimates indicate likelihood of depressed mood at Time 2 per 10 point difference in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at Time 1

Dependent variable is depressed mood measured at time 2. Models control for age, gender, race/ethnicity, health insurance coverage, % federal poverty level, family size, presence of health conditions, presence of limitations in basic or instrumental activities of daily living, survivor cancer type, survivor treatment status, MEPS panel number, and depressed mood at Time 1. Full model output is available as an online supplement. Time 1 and time 2 were 11 months apart, on average

Figure 3.

Association between depressed moodand partners’ subsequent depressed mood, Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (2004-2012). *p<0.05; Estimates represent odds of depressed mood at T2 in those with depressed mood at T1 (actor effects) or spouses with depressed mood at T1 (partner effects), compared to without depressed mood at T1. T1 and T2 were 11 months apart, on average. Models control for age, gender, race/ethnicity, health insurance coverage, % federal poverty level, family size, presence of health conditions, presence of basic/instrumental activities of daily living limitations, cancer type, survivor treatment status, MEPS panel number, and depressed mood at T1.

Actor effects

Survivors with depressed mood or distress at T1 were more likely to report depressed mood at T2 (Depressed mood: OR=12.17; 95% Confidence Interval [CI]=6.56-22.55; Distress: OR=1.34 [95% CI: 1.23-1.46]). Survivors with better mental or physical HRQoL at T1 were less likely to report depressed mood at T2 (Mental: OR= 0.30 [95% CI: 0.20-0.44]; Physical: OR=0.68 [95% CI: 0.53-0.88], respectively, per 10 point improvement in HRQoL). Spousal depressed mood, distress, and worse mental and physical HRQoL at T1 were also associated with increased likelihood of spousal depressed mood at T2.

Partner effects

Survivors whose spouses reported depressed mood at T1 were 4 times more likely to report depressed mood at T2 (OR=4.27 [95% CI: 2.01-9.07]). Better spousal mental and physical HRQoL were associated with a 30% lower risk of depressed mood in survivors (Mental: OR=0.72 [95% CI: 0.53-0.97]; Physical: OR=0.68 [95% CI: 0.53-0.87] per 10 point improvement in HRQoL score). The inverse associations (between survivor psychosocial factors and spousal depressed mood) were generally smaller and were not statistically significant. However, the association between survivor mental HRQoL at T1 and spousal depressed mood at T2 reached borderline significance.

Impact of gender on these relationships

The associations between spousal HRQoL at T1 and survivor depressed mood at T2 were substantially similar for male and female survivors (Table 3; italics indicate spouse→survivor estimates). However, the association between spousal depressed mood at T1 and survivor depressed mood at T2 was greater for wife than husband survivors (OR: 9.49 [95% CI: 2.42-37.20] versus 3.98 [95% CI: 1.43-11.12]; Figure 3). Corresponding effects were not statistically significant in the comparison groups, and the effect sizes were smaller (i.e., less extreme/closer to the null; Table 3).

Table 3. Association between spousal quality of life, distress, and depression on survivor depression over time, stratified by gender Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (2004-2012).

| Husband Cancer Survivor | Wife Cancer Survivor | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Dyads 95% CI |

Comparison Dyads 95% CI |

Cancer Dyads 95% CI |

Comparison Dyads 95% CI |

|||||||||||||

| Est | Lower | Upper | p- value |

Est | Lower | Upper | p- value |

Est | Lower | Upper | p- value |

Est | Lower | Upper | p- value |

|

| Depressed mooda | ||||||||||||||||

| Husband-->Husband | 7.35 | 3.16 | 17.06 | <.001 | 7.70 | 2.65 | 22.41 | <.001 | 9.27 | 2.75 | 31.31 | <.001 | 11.11 | 4.04 | 30.55 | <.001 |

| Wife-->Wife | 31.47 | 10.54 | 93.98 | <.001 | 11.84 | 4.19 | 33.47 | <.001 | 42.46 | 13.35 | 135.10 | <.001 | 17.75 | 6.67 | 47.23 | <.001 |

| Wife-->Husband | 3.98 | 1.43 | 11.12 | 0.009 | 1.50 | 0.42 | 5.39 | 0.532 | 2.24 | 0.58 | 8.69 | 0.246 | 1.24 | 0.38 | 4.10 | 0.723 |

| Husband-->Wife | 1.87 | 0.66 | 5.28 | 0.240 | 1.39 | 0.36 | 5.34 | 0.628 | 9.49 | 2.42 | 37.20 | 0.001 | 0.62 | 0.17 | 2.31 | 0.476 |

| Distressb | ||||||||||||||||

| Husband-->Husband | 1.39 | 1.22 | 1.58 | <.001 | 1.22 | 1.10 | 1.36 | <.001 | 1.11 | 0.95 | 1.28 | 0.180 | 1.28 | 1.13 | 1.46 | <.001 |

| Wife-->Wife | 1.27 | 1.11 | 1.45 | <.001 | 1.30 | 1.15 | 1.47 | <.001 | 1.36 | 1.18 | 1.57 | <.001 | 1.17 | 1.07 | 1.29 | 0.001 |

| Wife-->Husband | 1.06 | 0.96 | 1.17 | 0.242 | 1.04 | 0.93 | 1.15 | 0.506 | 1.08 | 0.97 | 1.19 | 0.157 | 0.96 | 0.87 | 1.06 | 0.456 |

| Husband-->Wife | 0.96 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 0.483 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.09 | 0.742 | 1.11 | 0.98 | 1.25 | 0.091 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 1.07 | 0.565 |

| Mental HRQoLc | ||||||||||||||||

| Husband-->Husband | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.39 | <.001 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.62 | <.001 | 0.58 | 0.31 | 1.11 | 0.099 | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.72 | 0.002 |

| Wife-->Wife | 0.47 | 0.27 | 0.83 | 0.009 | 0.47 | 0.28 | 0.77 | 0.003 | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.66 | 0.002 | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.59 | <.001 |

| Wife-->Husband | 0.69 | 0.44 | 1.08 | 0.106 | 1.20 | 0.75 | 1.93 | 0.446 | 0.60 | 0.36 | 1.01 | 0.055 | 1.14 | 0.72 | 1.80 | 0.582 |

| Husband-->Wife | 0.84 | 0.54 | 1.32 | 0.458 | 0.89 | 0.55 | 1.43 | 0.625 | 0.64 | 0.40 | 1.05 | 0.076 | 1.22 | 0.80 | 1.87 | 0.351 |

| Physical HRQoLc | ||||||||||||||||

| Husband-->Husband | 0.69 | 0.49 | 0.97 | 0.033 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 1.12 | 0.148 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 1.16 | 0.181 | 0.59 | 0.40 | 0.87 | 0.008 |

| Wife-->Wife | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.69 | 0.000 | 0.95 | 0.62 | 1.48 | 0.837 | 0.76 | 0.48 | 1.22 | 0.260 | 0.78 | 0.53 | 1.15 | 0.207 |

| Wife-->Husband | 0.61 | 0.44 | 0.85 | 0.004 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.97 | 0.034 | 0.87 | 0.54 | 1.40 | 0.558 | 0.98 | 0.67 | 1.43 | 0.907 |

| Husband-->Wife | 1.28 | 0.86 | 1.89 | 0.223 | 1.10 | 0.72 | 1.67 | 0.666 | 0.70 | 0.46 | 1.08 | 0.109 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 1.13 | 0.191 |

Estimates indicate likelihood of depressed mood at Time 2 for depressed versus not depressed mood at Time 1

Estimates indicate likelihood of depressed mood at Time 2 per 1 point difference in distress at Time 1

Estimates indicate likelihood of depressed mood at Time 2 per 10 point difference in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at Time 1

Dependent variable is depressed mood measured at time 2. Models control for age, race/ethnicity, health insurance coverage, % federal poverty level, family size, presence of health conditions, presence of limitations in basic or instrumental activities of daily living, survivor cancer type, survivor treatment status, MEPS panel number, and depressed mood at Time 1. Time 1 and time 2 were 11 months apart, on average

Italics indicate spouse-->survivor among couples with cancer

Sensitivity analyses

When we stratified the sample by treatment status, we found stronger evidence for associations in those dyads off treatment (Supplemental Table 5). This was partially due to the larger sample size in the off-treatment group, and to greater variability in the on-treatment group. The effects sizes of depressed mood and mental HRQoL in the spouse at T1 on depressed mood in the survivor at T2 were larger in the off-treatment group compared to the on-treatment group. Further, in the off-treatment group, survivor mental HRQoL and depressed mood at T1 were significantly associated with spouses’ depressed mood at T2.

When breast and prostate cancers were excluded from the analyses stratified by gender (Supplemental Table 6), the results were substantively unchanged, indicating that these two cancers were not driving the gender-specific results.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the association between psychosocial factors and spousal depressed mood among cancer survivors and their partners over time in a large, national sample. We found strong and consistent adverse associations of poor spousal HRQoL or depressed mood on the risk for subsequent depressed mood in cancer survivors. Further, weak evidence suggested that survivor mental HRQoL may be associated with greater risk for depressed mood in their spouses. These effects were stronger than those observed in a comparison sample of cancer-free dyads, in which there was little evidence for spousal spillover. These findings suggest that addressing and improving spousal mental health and HRQoL problems may reduce depressed mood in cancer survivors. By 2015, cancer care and after-care standards as part of survivorship care plans will require that survivors be screened for distress and referred to additional care if needed (46). Based on the findings of this study, however, standards supporting screening and referral of spouses may also be important for improving or maintaining cancer survivor mental health.

The findings from this study are generally consistent with other studies with cross-sectional designs or convenience samples, which show significant associations between spousal well-being and survivor depressed mood (47-51), or bidirectional effects of survivor and spousal well-being (52, 53). This study added to previous studies by examining these associations in a longitudinal, national sample.

Interestingly, spillover of depressed mood was greater from husbands to wives with cancer than from wives to their husbands with cancer. Further, there was no evidence for corresponding associations in matched comparison dyads. This suggests that spillover may be more pronounced in couples facing cancer and its after effects, and reinforces the importance of evaluating family-level factors in the clinical and survivorship care settings. Research indicates that couples experiencing marital distress also have gender disparities in depressed mood transmission (38), suggesting that gender differences in a cancer-but not the cancer-free samples may be driven by marital or relationship quality or family functioning. Further, dyadic coping may relate to depression in cancer survivors and their spouses (54). As these variables could not be evaluated in this study because they were not collected in the MEPS, future research will be needed to assess whether family factors may mediate or moderate these pathways.

Other studies assessing gender disparities in spillover have mixed findings, with some reporting differential effects for men and women (38, 55, 56), whereas others report no differences by gender (35, 57). Research in the general population suggests that women may be more impacted than men by their spouses’ health (58). Kim et al. (59) found that in female patients with lung or colorectal cancer, depressed mood adversely impacted their caregivers’ physical HRQoL (regardless of caregiver gender, although the effect was stronger for female than male caregivers), while in male patients, depressed mood adversely impacted caregivers’ mental HRQoL. Further, they did not find that caregiver depressed mood influenced patient HRQoL. Kim et al.’s findings may differ from ours because the studies examined different outcomes (HRQoL versus depressed mood) and populations. Future work in larger longitudinal studies will need to confirm whether the spousal spillover differs for depressed mood and HRQoL, as well as whether these relationships are consistent across cancer type and other chronic illnesses. In addition, the directionality and strength of these associations may differ throughout the trajectory of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. Following these relationships over longer periods of time in large, dyadic cohorts may reveal more complex transactional associations (47, 48, 52).

In sensitivity analyses, we stratified the sample by treatment status to explore whether the estimates were different for those receiving treatment around the time of the survey. The findings suggest that these associations may be more pronounced in couples who are experiencing after-effects of cancer but are no longer receiving treatment, reinforcing the importance of incorporating family caregivers into the survivorship care plan. The relatively small sample size of those on treatment limited our ability to explore this finding further. Future research is needed to better compare spillover effects for those on versus off treatment, or for short- versus long-term survivors with and without after effects.

This study should be interpreted in light of several potential limitations. First, the population-based MEPS includes a heterogeneous sample of cancer survivors, and we had limited information about the cancer (e.g., stage) and the caregiving situation (e.g., spouses’ role in caregiving, intensity or duration of care). Further, we had no information about the quality of the spousal relationship or other potentially important confounders such as family cohesion, social support, or dyadic coping. Second, same-sex and cohabitating couples could not be included in this study. Third, dyads with missing data were excluded from our analyses. Because those excluded dyads generally had worse psychosocial profiles than those dyads retained in the study sample, our results may be an underestimate of the effects of spousal well-being on depressed mood in cancer survivors. Fourth, the measures used in this study were brief scales, necessitated by the scope and depth of the MEPS. These are blunt instruments for assessing psychosocial factors such as depressed mood, and the results should be interpreted accordingly. Finally, the population in this study consisted of those who are still impacted by their disease (i.e., had a cancer-related health problem, medical event or disability at T1); spousal spillover may differ among long-term cancer survivors who are not experiencing late effects or disabilities. These limitations are balanced, however, by the population-based and longitudinal nature of the sample, and the inclusion of a cancer-free comparison group.

This study has several important implications for cancer survivors and their spouses, clinicians, and health care delivery. Health care professionals in both oncology and primary care have the opportunity to educate spouses or caregivers about the importance of their well-being in the survivor’s outcomes. In the oncology setting, clinicians should discuss psychosocial well-being and risk factors with patients and their families, and incorporate spousal assessment as part of the survivorship care plan. Our findings also suggest that spousal and family assessment should be incorporated into Patient Reported Outcome data collection efforts. In the primary care setting, ascertaining whether patients are providing informal care, such as asking about the health of their close family members, may help clinicians identify patients who may need additional care. Finally, hospitals and clinics have the opportunity to incorporate spouses and caregivers into clinical care through family-centered care and psycho-oncology or integrative programs. Developing systems that allow clinicians to treat or refer family members and incentivize follow-up and training clinicians in best practices when a caregiver, family member, or spouse reports depressed mood or poor quality of life may help improve survivor outcomes.

Given the adverse impact of depressed mood and distress on other health outcomes (11-19), preventing and treating depressed mood in survivors is critical. Some cancer survivors get less preventive and non-cancer care (60-62) and depressed survivors have lower adherence to cancer therapies (63) and are less likely to participate in health-promoting activities and behaviors (64-66). While depressed mood is influenced by many factors, the estimates in this study were of similar magnitude to the impact of having chronic pain (67). Our findings therefore suggest that taking care of the caregiver spouse may not only improve their own health, but may also improve the health of the cancer patient.

Using a national, population-based sample, this study found that depressed mood and poor quality of life in spouses of cancer survivors were associated with greater depressed mood risk in survivors. Survivor depressed mood or worse mental HRQoL were also borderline associated with greater risk of depressed mood in their spouses. Given the adverse effects of depressed mood on the long-term health outcomes of cancer survivors, improving spousal well-being may be an important approach to improving outcomes for cancer survivors. Future research should examine whether better incorporating spousal care into psycho-oncology and survivorship programs improves survivor outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Paige McDonald for her thoughtful feedback and guidance.

Research Support: Cancer Prevention Fellowship Program, National Cancer Institute

Financial Information

Authors are federal employees and this work had no specific funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimers and Conflicts of Interest: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the National Cancer Institute. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2004:57–71. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasquini M, Biondi M. Depression in cancer patients: a critical review. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health: CP & EMH. 2007;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker J, Holm Hansen C, Martin P, Sawhney A, Thekkumpurath P, Beale C, et al. Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: a systematic review. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO. 2013;24:895–900. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn LB, Cooper BA, Neuhaus J, West C, Paul S, Aouizerat B, et al. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. Vol. 30. American Psychological Association; 2011. Identification of distinct depressive symptom trajectories in women following surgery for breast cancer; pp. 683–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helgeson VS, Snyder P, Seltman H. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. Vol. 23. American Psychological Association; 2004. Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: identifying distinct trajectories of change; pp. 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henselmans I, Helgeson VS, Seltman H, de Vries J, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. Vol. 29. American Psychological Association; 2010. Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis; pp. 160–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn J, Ng SK, Holland J, Aitken J, Youl P, Baade PD, et al. Trajectories of psychological distress after colorectal cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2013;22:1759–65. doi: 10.1002/pon.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Archives of internal medicine. 2000;160:2101–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colleoni M, Mandala M, Peruzzotti G, Robertson C, Bredart A, Goldhirsch A. Depression and degree of acceptance of adjuvant cytotoxic drugs. Lancet. 2000;356:1326–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02821-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanton AL, Petrie KJ, Partridge AH. Contributors to nonadherence and nonpersistence with endocrine therapy in breast cancer survivors recruited from an online research registry. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2014;145:525–34. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bower JE. Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast cancer and survivors. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:768–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fann JR, Thomas-Rich AM, Katon WJ, Cowley D, Pepping M, McGregor BA, et al. Major depression after breast cancer: a review of epidemiology and treatment. General hospital psychiatry. 2008;30:112–26. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiraz F, Rahtz E, Bhui K, Hutchison I, Korszun A. Quality of life, psychological wellbeing and treatment needs of trauma and head and neck cancer patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52:513–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown LF, Kroenke K, Theobald DE, Wu J, Tu W. The association of depression and anxiety with health-related quality of life in cancer patients with depression and/or pain. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19:734–41. doi: 10.1002/pon.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Theobald D, Wu J, Loza JK, Carpenter JS, Tu W. The association of depression and pain with health-related quality of life, disability, and health care use in cancer patients. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2010;40:327–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giese-Davis J, Collie K, Rancourt KM, Neri E, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis. Journal of clinical oncology. 2011;29:413–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychological medicine. 2010;40:1797–810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satin J, Linden W, Phillips M. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009;115:5349. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mols F, Husson O, Roukema JA, van de Poll-Franse LV. Depressive symptoms are a risk factor for all-cause mortality: results from a prospective population-based study among 3,080 cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. Journal of cancer survivorship: research and practice. 2013;7:484–92. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, Gruman J, Champion VL, Massie MJ, et al. Screening, Assessment, and Care of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Adults With Cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline Adaptation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611. JCO. 2013.52. 4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goren A, Gilloteau I, Lees M, DaCosta Dibonaventura M. Quantifying the burden of informal caregiving for patients with cancer in Europe. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22:1637–46. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19:1013–25. doi: 10.1002/pon.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price MA, Butow PN, Costa DS, King MT, Aldridge LJ, Fardell JE, et al. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression in women with invasive ovarian cancer and their caregivers. The Medical journal of Australia. 2010;193:S52–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haley WE, LaMonde LA, Han B, Narramore S, Schonwetter R. Family caregiving in hospice: effects on psychological and health functioning among spousal caregivers of hospice patients with lung cancer or dementia. The Hospice journal. 2001;15:1–18. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.2000.11882959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grov EK, Dahl AA, Moum T, Fossa SD. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in caregivers of patients with cancer in late palliative phase. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1185–91. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowenstein A, Gilbar O. The perception of caregiving burden on the part of elderly cancer patients, spouses and adult children. Families, Systems, & Health. 2000;18:337. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim Y, Spillers RL, Hall DL. Quality of life of family caregivers 5 years after a relative’s cancer diagnosis: follow-up of the national quality of life survey for caregivers. Psychooncology. 2012;21:273–81. doi: 10.1002/pon.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bevans M, Sternberg EM. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. Jama. 2012;307:398–403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert SD, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C, Stacey F. Walking a mile in their shoes: anxiety and depression among partners and caregivers of cancer survivors at 6 and 12 months post-diagnosis. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirst M. Carer distress: a prospective, population-based study. Social science & medicine. 2005;61:697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Litzelman K, Skinner HG, Gangnon RE, Nieto FJ, Malecki K, Witt WP. Role of global stress in the health-related quality of life of caregivers: evidence from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1569–78. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0598-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valle G, Weeks JA, Taylor MG, Eberstein IW. Mental and physical health consequences of spousal health shocks among older adults. Journal of aging and health. 2013;25:1121–42. doi: 10.1177/0898264313494800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D. The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28:236–45. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodenmann G. A systemic-transactional conceptualization of stress and coping in couples. Swiss J Psychol. 1995:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyler D, Stimpson JP, Peek MK. Health concordance within couples: a systematic review. Social science & medicine. 2007;64:2297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elder Jr G. The life course as developmental theory. Child Dev. 1998;69:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bengtson VL, Elder Jr GH, Putney NM. The life course perspective on ageing: Linked lives, timing, and history. In: Katz J, Peace S, Spurr S, editors. Adult Lives: A Life Course Perspective. The Policy Press; Bristol, UK: 2012. pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kouros CD, Cummings EM. Longitudinal Associations Between Husbands’ and Wives’ Depressive Symptoms. Journal of marriage and the family. 2010;72:135–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Q, Loke AY. A literature review on the mutual impact of the spousal caregiver-cancer patients dyads: ‘communication’, ‘reciprocal influence’, and ‘caregiver-patient congruence’. European journal of oncology nursing: the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society. 2014;18:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fletcher BS, Miaskowski C, Given B, Schumacher K. The cancer family caregiving experience: an updated and expanded conceptual model. European journal of oncology nursing: the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society. 2012;16:387–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medical Expenditure Panel Survey [homepage on the Internet] Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: [cited 2015 March 24]; Available from: http://meps.ahrq.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical care. 2003;41:1284–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological medicine. 2002;32:959–76. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ware Jr JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer . Cancer program standards 2012: Ensuring patient-centered care. American College of Surgeons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Segrin C, Badger T, Dorros SM, Meek P, Lopez AM. Interdependent anxiety and psychological distress in women with breast cancer and their partners. Psycho-oncology. 2007;16:634–43. doi: 10.1002/pon.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segrin C, Badger TA, Harrington J. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. Vol. 31. American Psychological Association; 2012. Interdependent psychological quality of life in dyads adjusting to prostate cancer; pp. 70–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim Y, Carver CS, Spillers RL, Love-Ghaffari M, Kaw CK. Dyadic effects of fear of recurrence on the quality of life of cancer survivors and their caregivers. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2012;21:517–25. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9953-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ejem DB, Drentea P, Clay OJ. The effects of caregiver emotional stress on the depressive symptomatology of the care recipient. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19:55–62. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.915919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Northouse LL, Mood D, Templin T, Mellon S, George T. Couples’ patterns of adjustment to colon cancer. Social science & medicine. 2000;50:271–84. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Segrin C, Badger TA. Psychological and physical distress are interdependent in breast cancer survivors and their partners. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19:716–23. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2013.871304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL, Kaw CK, Smith TG. Quality of life of couples dealing with cancer: dyadic and individual adjustment among breast and prostate cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Annals of behavioral medicine: a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35:230–8. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rottmann N, Hansen DG, Larsen PV, Nicolaisen A, Flyger H, Johansen C, et al. Dyadic Coping Within Couples Dealing With Breast Cancer: A Longitudinal, Population-Based Study. Health Psychol. 2015 doi: 10.1037/hea0000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stimpson J, Peek M, Markides K. Depression and mental health among older Mexican American spouses. Aging & mental health. 2006;10:386. doi: 10.1080/13607860500410060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larson RW, Almeida DM. Emotional transmission in the daily lives of families: A new paradigm for studying family process. Journal of marriage and the family. 1999:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joiner TE, Katz J. Contagion of Depressive Symptoms and Mood: Meta-analytic Review and Explanations From Cognitive, Behavioral, and Interpersonal Viewpoints. Clinical Psych Sci Pract. 1999;6:149–64. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV, Brilman EI, Kempen GI, Ormel J. Chronic disease in elderly couples: are women more responsive to their spouses’ health condition than men? J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:693–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim Y, van Ryn M, Jensen RE, Griffin JM, Potosky A, Rowland J. Effects of gender and depressive symptoms on quality of life among colorectal and lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psychooncology. 2015;24:95–105. doi: 10.1002/pon.3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Earle C, Neville B. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101:1712. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Peairs KS, Kantsiper ME, Herbert RJ, Blackford AL, et al. Comparing care for breast cancer survivors to non-cancer controls: a five-year longitudinal study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:469–74. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0903-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Herbert RJ, Blackford AL, Neville BA, Wolff AC, et al. Quality of Care for Comorbid Conditions During the Transition to Survivorship: Differences Between Cancer Survivors and Noncancer Controls. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:1140. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment - Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Archives of internal medicine. 2000;160:2101–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Gelmon K, Reid RD, Mackey JR, Friedenreich CM, et al. Predictors of supervised exercise adherence during breast cancer chemotherapy. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2008;40:1180–7. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318168da45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schnoll RA, Martinez E, Tatum KL, Weber DM, Kuzla N, Glass M, et al. A bupropion smoking cessation clinical trial for cancer patients. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:811–20. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9507-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katz M, Donohue K, Alfano C, Day J, Herndon J, 2nd, Paskett E. Cancer surveillance behaviors and psychosocial factors among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Cancer and Leukemia Group B 79804. Cancer. 2009;115:480. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaiser NC, Hartoonian N, Owen JE. Toward a cancer-specific model of psychological distress: population data from the 2003-2005 National Health Interview Surveys. Journal of cancer survivorship: research and practice. 2010;4:291–302. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.