Abstract

Background:

Subacute granulomatous thyroiditis (SGT) is an inflammatory disease that presents with different clinical and cytological characteristics. Although the diagnosis is generally made clinically, imaging methods and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) may provide assistance, particularly in atypical cases. The objective of this study is to reveal the ultrasonographic (USG) and cytological characteristics of SGT.

Materials and Methods:

The clinical, USG and cytological findings of 21 cases diagnosed with SGT were reviewed.

Results:

Ultrasonographic data was available in 20 cases. A hypoechoic thyroid nodule with irregular margins was detected in 12 of the 20 total cases. Of these, 9 cases complained about pain in the thyroid lodge and generally had unilateral lesions, heterogeneous and hypoechoic areas with indistinct margins, rather than nodular lesions, which were seen in 7 cases. Cytologically, the multinuclear giant cells (MNGCs) found in all cases were accompanied by a dirty background containing varying numbers of granulomatous structures, including isolated epithelioid histiocytes, proliferated/regenerated follicle epithelium cells and inflammatory cells and colloid.

Conclusion:

Though hypoechoic and heterogeneous areas with irregular margins are strongly associated with thyroiditis, SGT may also appear as painful or painless hypoechoic, solid nodules and generate challenges in differential diagnosis. Although the most remarkable characteristic observed in FNA cytology was the presence of multiple MNGCs with cytoplasm, a dirty background accompanied by mild-moderate cellularity, degenerated-proliferated follicular epithelium cells, rare epithelioid granulomas and mixed type inflammatory cells are characteristic for SGT. The assessment of these radiological and cytological findings in conjunction with clinical findings will assist in the achievement of an accurate diagnosis.

Keywords: De Quervain's thyroiditis, fine-needle aspiration cytology, giant cell thyroiditis, subacute granulomatous thyroiditis, ultrasonography

INTRODUCTION

Subacute granulomatous thyroiditis (SGT), also known as De Quervain's thyroiditis, is a self-limiting, inflammatory disease of the thyroid that is believed to be caused by a systemic viral infection.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7] It was first diagnosed in 1825, and 18 cases were reported as “thyroiditis acuta simplex” until 1895. This pathology was compiled by the Swiss surgeon De Quarvein in 1904 and 1936.[4] It typically occurs in the area of the gland in mid-aged hyperthyroid women complaining of pain, tenderness, fatigue and mild fever.[1,2,5,6,7]

It is usually clinically diagnosed without the need for fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Therefore, there are few studies regarding the cytological features of SGT in the literature. However, it is important to exclude other diseases of the thyroid because SGT may be confused with them, particularly with malignancies.[1,4] Imaging methods and FNA may help in the diagnosis of SGT.[2]

The objective of this study is to define the ultrasonographic (USG) and cytopathologic characteristics of SGT and highlight its differential diagnosis from the other lesions of the thyroid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 21 cases diagnosed with SGT between 2001 and 2014 were included in our study. The clinical, radiological and cytological characteristics of the patients were reviewed. Clinical data, such as the patients’ ages, clinical findings and clinical preliminary diagnoses and the USG findings, were obtained retrospectively from the pathology reports. Cytological preparations were re-evaluated in terms of cellularity, multinuclear giant cells (MNGCs), granulomatous structures, histiocytes, colloids, follicular epithelial cells, fibrous fragments and inflammatory cells.

Fine-needle aspirations were performed by a cytopathologist (NP), who was accompanied by a radiologist (KY), and with ultrasonography guidance, by using a 22-gauge needle, 10 cc syringe and aspirator. On average, 3 entries were made into each thyroid nodule or suspicious lesion. The procedure was concluded upon the detection of a sufficient number of air-dried preparations stained with the Diff-Quik® dye at the bedside. The preparations were fixed in the 95% alcohol and stained by Papanicolaou stain.

RESULTS

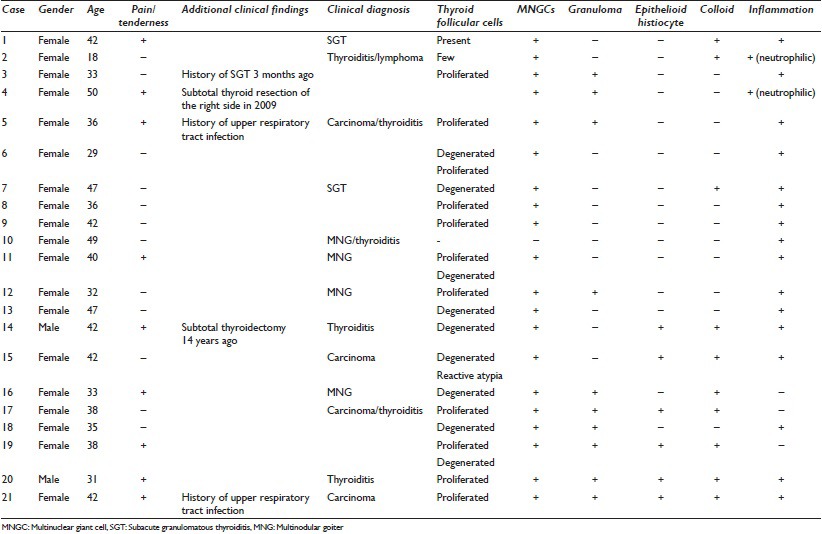

The clinical and cytological characteristics of the 21 cases included into the study have been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and cytopathological features of subacute granulomatous thyroiditis

All, except two cases, were women (90%) and the mean age was 38.19 years (18–50 years). Seven cases presented with a pain complaint in the area of the thyroid lasting a few weeks, whereas 2 cases had pain and previous upper respiratory tract infection and 1 case had a history of SGT that had occurred 3 months previously. The preliminary clinical diagnosis was SGT in 2 cases, thyroiditis in 6 cases, multinodular goiter (MNG) in 4 cases, thyroid carcinoma in 4 cases and lymphoma in 1 case.

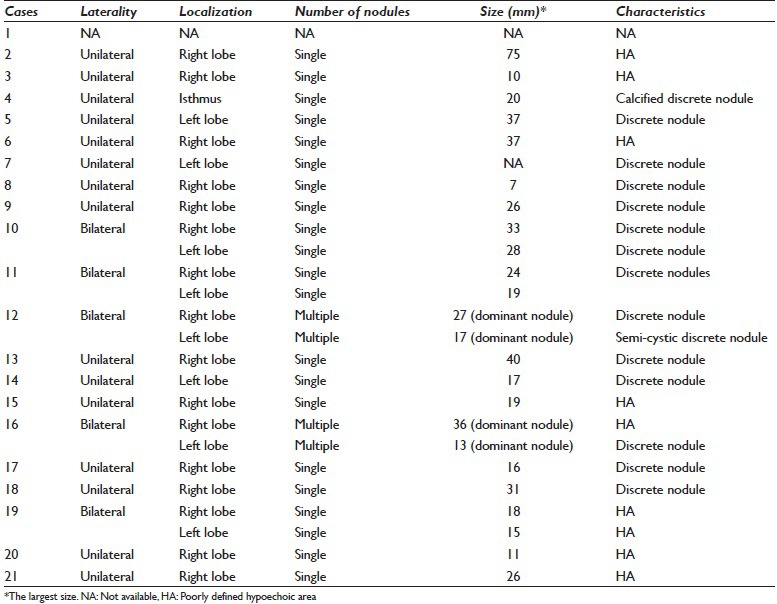

The imaging reports of 1 case (case-1) could not be reached. The USG findings of the other 20 cases have been summarized in Table 2. “Hypoechoic thyroid nodules with irregular margins” were observed in 12 cases at USG, whereas “heterogeneous, hypoechoic areas (lava flow) with indistinct margins” were observed in 7 cases [Figures 1a and 2a]. In 1 case (case 16), one of the bilateral and multiple lesions, which located on the right side, appeared with a hypoechoic area, and the others presented as nodular lesions. In the 13 cases that presented as nodular lesions, the nodules were generally unilateral and single, with the largest mean size being 22.19 mm (range: 7–40 mm), whereas the largest mean size of the hypoechoic-heterogeneous areas was 27.52 mm (range: 10–75 mm).

Table 2.

Ultrasonographic findings of subacute granulomatous thyroiditis

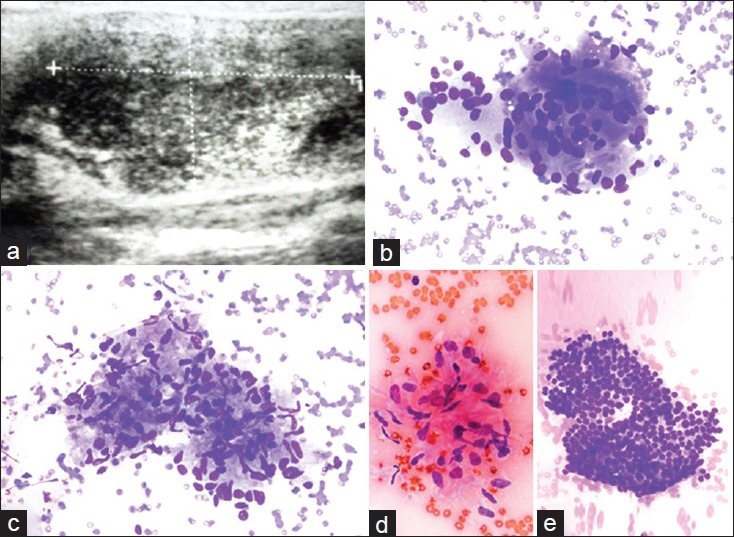

Figure 1.

A Subacute granulomatous thyroiditis case sonographically characterized by an ill-defined hypoechoic nodule (case no. 17). (a) An ultrasound image showing a ill-defined nodule. The cytologic features of the case included the following: (b) Multi-nucleated giant cell (Papanicolau stain, ×400), (c) an epithelioid histiocytic granuloma (Papanicolau stain, ×400), (d) a group of epithelioid histiocytes adjacent to a giant cell (Papanicolau stain, ×400) and (e) a collection of proliferated follicular cells (Papanicolau stain, ×200)

Figure 2.

A subacute granulomatous thyroiditis case with a sonographic image of a poorly defined hypoechoic area. (a) Ultrasound appearance with a discrete area (case no. 19). The cytologic features of the case included the following: (b) Multinucleated giant cell (Diff Quik®, ×400), (c) an aggregate of epitheliod histiocytes consistent with granuloma (Diff Quik®, ×400), (d) a cluster of epithelioid histiocytes (Papanicolau stain × 400) and (e) a group of proliferated follicular cells (Diff Quik®, ×400)

Cytologically, the diffusions were generally normocellular or moderately cellular, and there was no highly dense (tumoral) cellularity.

All cases presented with follicular epithelial cells, although this was rare in some such cases. The cells were generally shaped as honeycomb fragments, with a partially degenerated and proliferated appearance, and it was noted that reactive atypia accompanied 1 case (case 15). However, no papillary or microfollicular structuring, plasmacytoid appearance or intranuclear inclusion or groove was observed in any sample.

Multinuclear giant cells were an invariable characteristic in all cases. Generally, these cells were scattered and occurred at a high frequency. The MNGCs were of variable sizes and forms, contained a cytoplasmic content and were generally large. They had a high number of nuclei and dense and angulated cytoplasm. Phagocyted colloid and neutrophils appeared in the cytoplasm of some MNGCs. In rare cases, there were also some smaller, round, vacuole-cytoplasm MNGCs that contained less nucleus.

Though there were epitheloid histiocytes and clusters of epitheloid histiocytes, which were believed to be granulomas, in 10 cases, the epitheloid cells were isolated or formed loose cohesive clusters in 3 cases. There were no granulomas or epithelioid cells in any of the remaining cases. The granulomas that were assessed appeared similar to those in other granulomatous diseases, specifically, to be derived from bare-foot or carrot-shaped nucleus cells constituting tight syncytial groups of variable sizes [Figures 1 and 2b–e].

Colloid was observed occasionally in 8 cases. This colloid generally appeared in thick, small and large masses inside epithelioid histiocytes, some of which occurred in a phagocytosed manner.

All cases had a dirty background that was composed of cellular debris, blood elements and pink amorphous acellular material, and this was accompanied by neutrophil leukocytes in 2 cases and mixed types of inflammatory cells with dominant lymphocytes in the remaining cases.

DISCUSSION

The inflammatory diseases of the thyroid gland are classified into three groups, that is, acute, subacute and chronic.[3,8] De Quervain's thyroiditis, also named giant-cell or granulomatous thyroiditis, is the subacute inflammation of the thyroid and constitutes nearly 3–6% of all thyroid diseases.[1,3,4] It is a nonspecific inflammation that generally appears 2 weeks after a viral upper respiratory tract infection and regresses spontaneously within 2–3 months.[3,6,9] Although its etiology remains unknown, it is believed have a viral origin, similar to the mumps virus, hepatitis B and C viruses, cytomegalovirus enterovirus, and type a and b coxsackie viruses.[3,5]

Subacute granulomatous thyroiditis predominantly affects adult females, and the ratio of females to males is 2:1–6:1.[1,2,6] Clinically, patients present with localized anterior neck pain associated with glandular tenderness and diffuse pain in the ears and the jaw, which is accompanied by fatigue, weight loss, low-grade fever, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, suppression in the thyroid stimulating hormone level and occasionally dysphagia.[1,2,3,4,5,6,9] The patient's level of C reactive protein is usually normal or slightly high.[3] The thyroid is sensitive at palpation, and there is a mild-moderate growth in the thyroid.[3,5,8] Depending on the stage of the disease, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism or euthyroidism may be seen in patients.[1,3,5] The patients recover spontaneously after weeks or months,[1,6,10] and recovery may be supported by symptomatic treatment with nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs or, occasionally, cortisone.[6,10]

Subacute granulomatous thyroiditis is generally diagnosed after the assessment of clinical and laboratory data. However, imaging methods may be helpful for the diagnosis.[2,6] Generally, an increase in the size of the thyroid and heterogeneous, diffuse, hypoechoic and confluent areas with negative margins, characteristically defined as “lava flow,” are observed on USG.[2,6] No increase occurs in the vascularity on colored Doppler USG.[3,6,8] However, these findings are nonspecific because they may also be observed in lymphocytic thyroiditis, MNG and Graves diseases, and the clinical findings may assist in the differential diagnosis.[6] SGT may also present with nonsensitive solid nodules.[3,7] Unlike the literature findings related to this topic, the number of cases appearing as nodules in our study (13 cases) was relatively higher than the number of cases appearing as hypoechoic areas (7 cases). Additionally, most of our cases were unilateral.[11]

Due to the risk of infiltrative malignancies, such as generalized parenchymal abnormalities, which can be interpreted as diffuse nonneoplastic thyroid disease, including SGT, repeated USG and even FNA should be performed to exclude other malignancies in sensitive or nonsensitive hypoechoic and solid nodules.[6] Due to the rare need for FNA, cytopathologists are not directly familiar with SGT.[1,5,6,10] However, the frequency of cytopathological use has increased with the development of USG approaches.[6]

Fine-needle aspiration is beneficial in the diagnosis of thyroiditis and may provide very accurate results.[8] FNA plays an important role for accurate diagnosis, particularly when clinicians do not suspect SGT or in atypical cases.[4] The fact that among all of our cases, there is no distinct clinical finding that may help us, except for pain in the area of the thyroid in 7 cases, pain and previous upper respiratory tract infection in 2 cases, and the presence of a history of SGT in 1 case as well as the absence of malignancies among clinical differential diagnoses in 5 cases; this reveals the importance of FNA.

The key cytological characteristics for SGT are as follows: (i) A high number of MNGCs, (ii) epithelioid cells with a tendency for clustering, (iii) epithelioid cell granulomas, (iv) lymphocytes, macrophages and neutrophils, (v) frequently degenerated follicular epithelial cells displaying mild-moderate cellularity, and (vi) a dirty background that is composed of cellular debris, naked, degenerated nuclei and thick colloids.[1,8,9,12,13] The absence of one or a few of these does not exclude SGT but instead increases the number of thyroid diseases that are included in the scope of the differential diagnosis.[4]

The characteristic cytological feature of SGT is the presence of MNGCs, which may comprise hundreds of large nuclei and contain colloidal residues in their cytoplasm[10][Figure 3]. However, these cells are not specific to SGT. MNGCs may be seen inflammatory conditions of the thyroid (granulomatous diseases, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Graves disease and palpation thyroiditis), hyperplastic conditions (MNG displaying degenerative changes) and neoplastic conditions (papillary carcinoma, anaplastic carcinoma).[1,4,9,10,14]

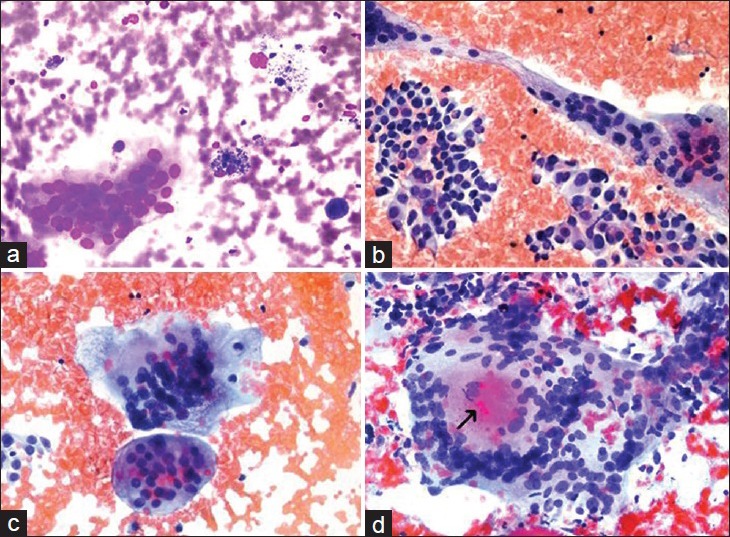

Figure 3.

The types of multinucleated giants cells seen in various thyroid lesions. (a) Multinucleated giant cell secondary to a benign cystic nodule (our archival case) (Diff Quik®, ×400). (b) Bizarre giant cells seen in a case papillary thyroid carcinoma (our archival case) (Papanicolau stain, ×400). (c) Multinucleated giant cells encountered in the previous papillary thyroid carcinoma case (×400). (d) Multinucleated giant cell with an intracytoplasmic colloid like material (arrow) seen in one of our subacute granulomatous thyroiditis cases (case no. 21) (Papanicolau stain, ×400)

Two morphological types MNGCs can be observed in FNA samples: Those with foamlike cytoplasm and those with dense cytoplasm. MNGCs with foamlike cytoplasm are round cells with less diagnostic importance and are generally seen in cystic degeneration. They are usually composed of multinuclear forms of histiocytes, flat cytoplasmic contours, foamlike, vacuole and hemosiderin cytoplasms [Figure 3a]. Further, MNGCs with dense cytoplasm have angular cytoplasm and irregular shapes, are larger and contain a higher number of nuclei.[14] Primarily, the three following conditions should come to mind in diffusions containing MNGCs: (i) SGT, (ii) granulomatous diseases, such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis and fungal infections, and (iii) papillary carcinoma of the thyroid (PC).[1,14] PC is the most important condition to be excluded. The presence of tumor cellularity and PC nuclear characteristics (powdery chromatin, nuclear groove and intranuclear inclusions), overlapping syncytial tissue fragments, real papillary fragments, if any, and psammoma bodies are characteristics in favor of PC. The MNGCs that they contain are smaller in number and size compared with SGT and granulomatous diseases. These cells are called “bizarre giant cells” [Figure 3b]. However, in some PC cases, MNGCs of SGT can be seen in addition to the “bizarre giant cells” [Figure 3c].[1,14]

Dirty background with clinical, well-formed or poor-formed epithelioid granulomas and acute-chronic inflammation is included in the differential diagnosis for SGT. The MNGCs that are present have a tendency to be more frequent and larger in size and to contain more nuclei.[1,4,10,14] They may also contain intracytoplasmic, colloid-like material [Figure 3d].

The main cells in the granulomatous diseases of the thyroid are epithelioid histiocytes, and the granulomas observed are generally well formed, comprise fewer lymphocytes and acute inflammatory components and do not contain a dirty background.[1,14] The giant cells seen in anaplastic carcinomas are generally osteoclast type giant cells.[13] However, it should also be highlighted that MNGCs may not always be seen in SGT aspirates, may sometimes be too few and scattered, or may very rarely be seen in SGT as intensely as they appear in other thyroid diseases.[4]

Granulomas, which appear as epithelioid histiocyte clusters, are another key characteristic for SGT but are rare or may not be seen.[10] Different rates have been reported with regard to the presence of granulomas in SGT in different studies in literature, and it was suggested that these different rates were due to the association with the stage of the disease or a sampling error.[1] Epithelioid granulomas were defined in many cases, such as tuberculosis, sarcoidosis and fungal infections, postsurgically in the neck area, auto-palpation habit, hemorrhage in nodular goiter, proximity to histiocytic reaction, Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves’ diseases.[4] The presence of a high number of MNGCs accompanied by acute onset pain, which is also a characteristic clinical symptom for SGT, will be helpful for differential diagnosis.[9]

García Solano et al. reported the presence of follicular cells with intravacuolar granules and/or plump transformed follicular cells, though this was not a marked characteristic in our cases.[4] In contrast, the follicular epithelial cells in our cases were generally degenerated/proliferated, and regenerative atypia findings were observed from an aspirate taken with the suspicion of malignancy. However, the patient was diagnosed as SGT due to the absence of cellular and structural malignant characteristics, despite the presence of a high number of MNGCs and epithelioid cells accompanied by a dirty background. It was noted that this lesion disappeared in the follow-ups.

If the patient has the cytological characteristics specified above when he/she comes to the clinic with a clinical diagnosis of SGT, the cytological diagnosis of SGT may not be too difficult. However, the following factors may rise to challenges in the diagnosis: (i) Lack of clinical data, (ii) failure of the needle to reach the target, (iii) absence of the typical cytological characteristics (i.e. MNGCs, granulomas) as in acute or advanced stage of the disease, and (iv) presence of atypical follicular epithelium cells without other diagnostic elements.[4,9] According to Ofner et al., atipia is usually seen in acute phase of SGT.[15]

Although pain and tenderness in the thyroid gland is a very important finding for the diagnosis of SGT, it is not specific and may be seen in suppurative thyroiditis, trauma, radiation, nodular goiter, hemorrhagic and infarct areas, metastatic diseases and rarely, in Hashimoto's thyroiditis.[1,4,5,9] It is also known that painless or silent SGTs may occur.[5] Generally, the correct diagnosis can be made by combining detailed clinical and physical examination and using serological and cytological characteristics in combination.[1] However, clinical follow-up and FNA may be very beneficial in such cases.[4]

CONCLUSION

Subacute granulomatous thyroiditis is a dynamic process, and USG and cytological findings may vary according to the stage of the disease. Although there is no special radiological finding of thyroiditis, hypoechoic and heterogeneous areas with irregular margins in the thyroid are strongly associated with thyroiditis. However, SGT may also appear as a painful or painless hypoechoic and solid nodule, as occurs in most of our cases. They may be confused with malignancies, particularly in such cases, and give rise to difficulties in differential diagnosis.

The characteristic cytological features in our series in FNA were a high number of MNGCs with dense cytoplasm, mild-moderate cellularity, degenerated-proliferated follicular epithelial cells and dirty background accompanied with epithelioid granulomas and rare, mixed type inflammatory cells.

Although the presence of neck pain in the clinical history, the detection of MNGCs at FNA, their morphological characteristics and their number play a key role in the diagnosis. Further, utilizing tbc-fungal cultures and assessing the accompanying cell population in the background may help in the differential diagnosis.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE. Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.CV conceived of the study and drafted the manuscript. NP participated in its design and coordination and helped to scientific revision of the manuscript. NGD participated in the data collection. KY performed the sonograms and carried out the ultsonographic analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with the approval from all the institutions associated with this study as applicable.

Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

SGT = Subacute Granulomatous Thyroiditis

FNA = Fine-Needle Aspiration

USG = Ultrasonographic

MNGCs = Multinuclear Giant Cells

MNG = Multinodular Goiter

PC = Papillary Carcinoma

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

Dr. Busra Y Bayrak's contribution to preperation of the microphotos is appreciated.

Contributor Information

Çigdem Vural, Email: dr.cvural@gmail.com.

Nadir Paksoy, Email: nadirpaksoy@gmail.com.

Nazlı D Gök, Email: drnazlidemirgok@hotmail.com.

Kadri Yazal, Email: kadriyazal@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shabb NS, Salti I. Subacute thyroiditis: Fine-needle aspiration cytology of 14 cases presenting with thyroid nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:18–23. doi: 10.1002/dc.20395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cappelli C, Pirola I, Gandossi E, Formenti AM, Agosti B, Castellano M. Ultrasound findings of subacute thyroiditis: A single institution retrospective review. Acta Radiol. 2014;55:429–33. doi: 10.1177/0284185113498721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oláh R, Hajós P, Soós Z, Winkler G. De Quervain thyroiditis. Corner points of the diagnosis. Orv Hetil. 2014;155:676–80. doi: 10.1556/OH.2014.29865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García Solano J, Giménez Bascuñana A, Sola Pérez J, Campos Fernández J, Martínez Parra D, Sánchez Sánchez C, et al. Fine-needle aspiration of subacute granulomatous thyroiditis (De Quervain's thyroiditis): A clinico-cytologic review of 36 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:214–20. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199703)16:3<214::aid-dc4>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alfadda AA, Sallam RM, Elawad GE, Aldhukair H, Alyahya MM. Subacute thyroiditis: Clinical presentation and long term outcome. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:794943. doi: 10.1155/2014/794943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park SY, Kim EK, Kim MJ, Kim BM, Oh KK, Hong SW, et al. Ultrasonographic characteristics of subacute granulomatous thyroiditis. Korean J Radiol. 2006;7:229–34. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2006.7.4.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Omori N, Omori K, Takano K. Association of the ultrasonographic findings of subacute thyroiditis with thyroid pain and laboratory findings. Endocr J. 2008;55:583–8. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k07e-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aydin O, Apaydin FD, Bozdogan R, Pata C, Yalcinoglu O, Kanik A. Cytological correlation in patients who have a pre-diagnosis of thyroiditis ultrasonographically. Endocr Res. 2003;29:97–106. doi: 10.1081/erc-120018680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bibbo M, Wilbur D. Thyroid. In: Bibbo M, Wilbur D, editors. Comprehensive Cytopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 2008. pp. 633–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mordes DA, Brachtel EF. Cytopathology of subacute thyroiditis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:433–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frates MC, Marqusee E, Benson CB, Alexander EK. Subacute granulomatous (de Quervain) thyroiditis: Grayscale and color Doppler sonographic characteristics. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:505–11. doi: 10.7863/jum.2013.32.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koss L, Melamed M, Koss L, Melamed L, editors. Koss' Diagnostic Cytology and its Histopathologic Basis. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lipincott Williams and Wilkins Company; 2006. The thyroid, parathyroid, and neck masses othe than lymph nodes; pp. 1148–85. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayaram G, Marwaha RK, Gupta RK, Sharma SK. Cytomorphologic aspects of thyroiditis.A study of 51 cases with functional, immunologic and ultrasonographic data. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:687–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shabb NS, Tawil A, Gergeos F, Saleh M, Azar S. Multinucleated giant cells in fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: Their diagnostic significance. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21:307–12. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199911)21:5<307::aid-dc2>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ofner C, Hittmair A, Kröll I, Bangerl I, Zechmann W, Tötsch M, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytodiagnosis of subacute (de Quervain's) thyroiditis in an endemic goitre area. Cytopathology. 1994;5:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.1994.tb00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]