Abstract

There has been an increasing trend in Laparoscopic surgeries. There is also a higher incidence of patients with ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts due to the advances in the techniques of cerebral shunts. Surgeons may come across patients of VP shunts presenting with an indication for laparoscopic surgery. Although there is no absolute contraindication for laparoscopy in VP shunts, there is always a risk of raised intracranial pressure. We describe a case of VP shunt presenting with an ectopic pregnancy and undergoing laparoscopic salpingectomy. Patient withstood the procedure well and had an uneventful recovery. Reviewing the literature, we found that laparoscopy is safe in VP shunts. However, there should always be accompanied by good monitoring facilities.

Keywords: Intracranial pressure, Laparoscopy, Safety, Ventriculoperitoneal shunts

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral shunts are indicated for Hydrocephalus to drain the CSF into a cavity to prevent the increase in intracranial pressure.[1] Hydrocephalus could be congenital or due to a tumor, aqueductal stenosis, craniosynostosis, Dandy-Walker syndrome or Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. A commonly used route for the shunt is the ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt, which drains CSF into the peritoneal cavity. The other routes that are used are ventriculo-atrial, ventriculo-pleural, and lumbar-peritoneal. The complications that can occur with a shunt are infection, blockage, and overdrainage.

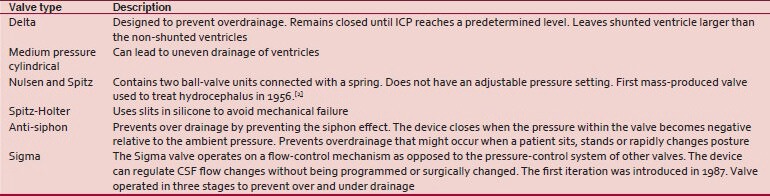

There are various shunts, all of which have a unidirectional valve system in place to prevent the retrograde infection or increase in pressure.

Advances in surgeries of cerebral shunts and the increased life span associated with them, has made the incidence of patients with VP shunts presenting with an indication for laparoscopy higher.

A few questions that arise:

Whether the pneumoperitoneum created during a laparoscopy procedure will cause retrograde diffusion of gases into the ventricles causing increased intracranial pressure and associated complications?

Whether the shunt can get infected and cause meningitis?

The effect of CO2 on the brain as the shunt connects two cavities?

What pre-operative counseling is required for such patients?

CASE REPORT

A 32-year lady came with complaints of bleeding P.V. following 1½ months of amenorrhea and pain in the left lower abdomen since 2 days and her UPT was weakly positive. An ultrasound examination revealed a 4.5 cm left ectopic tubal pregnancy with no intrauterine gestation and with free fluid in the POD. She was operated 10 years back for a VP shunt in view of a normal pressure hydrocephalus. She has 3 children, first two delivered vaginally and her last child birth was by cesarean section 6 years back. Her antenatal and intrapartum course was uneventful. She has no other significant medical or surgical history.

A decision for laparoscopic management was taken. Routine pre-operative evaluation was carried out and specifically to note whether the shunt was functional, we ruled out any neurological symptoms like headache or visual symptoms. Under general anesthesia, the laparoscopic port was inserted, pelvic evaluation was carried out and a left isthmic ectopic gestation was noted with minimal blood in the POD. The VP shunt catheter was seen in the peritoneum [Figure 1–3] and 30° Trendelenburg's position was given. The average insufflation pressure was maintained below 12 mm Hg with a set flow rate of 12 l/min. Intraoperative vitals were monitored for pulse, BP, oxygenation, ETCO2 and electrocardiogram leads. There was no evidence of intraoperative bradycardia, hypertension or desatutarion. The ectopic was treated by a left salpingectomy and the surgery was uneventful. During the procedure, special care was taken to avoid manipulation of the shunt. A 3rd generation cephalosporin was given intraoperatively. The operative time was 25 min from the time of skin incision to closure of the ports. Post-operative, her vitals were monitored and examined for any neurological symptoms and signs such as headache, neck stiffness, and fever. With an uneventful post-operative recovery, she was discharged after 24 h. Patient followed-up after a week without any neurological signs or symptoms

Figure 1.

Ventriculo-peritoneal shunt – Peritoneal Cavity End

Figure 3.

Ventriculo-peritoneal shunt – Entering the Peritoneum

Figure 2.

Ventriculo-peritoneal shunt – Coiled up

DISCUSSION

There is still controversy regarding the safety of performing laparoscopic surgery in patients with VP shunt and potentially decreased cerebral compliance. In previous studies using minimal monitoring of CSF shunt function limited to clinical observation, laparoscopic procedures were reported as safe and efficient in patients with CSF shunts.[3] However, animal studies have demonstrated that increased intra-abdominal pressure with gas insufflation and Trendelenburg position could induce a linear increase in ICP reaching 150% over control values with intra-abdominal pressures above 16 mm Hg.[4] The main advocated mechanisms for increased ICP in the presence of pneumoperitoneum, were increased intra-thoracic pressure,[4,5] and impaired venous drainage of the lumbar venous plexus,[2] rather than increased arterial carbon dioxide because of systemic carbon dioxide diffusion.[6]

Jackman et al. observed 19 laparoscopic surgeries in patients with VP shunts with a mean insufflation pressure of 16 mm Hg and an average operative time of 3 h. They did not find clinically significant increased intracranial pressure in patients. Routine anesthetic monitoring should remain the standard of care in the absence of clear evidence to the contrary.[7]

Fraser et al. found no episodes of air embolism one shunt infection in a study conducted over 51 laparoscopy procedures in patients with VP shunts.[8] Neale et al. studied an in vitro model with nine shunts subjected to increased back pressure and none of the valves showed any signs of leak associated with the increased back pressure.[9] The risk of retrograde failure of the valve system has been shown to be minimal even with intra-abdominal pressures as high as 80 mm Hg.[10]

CONCLUSION

The presence of a VP shunt does not appear to have any significant risk in patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures. The risk of retrograde failure of the valve, air embolism, and infection is minimal. The insufflation pressure must be the minimum required and at all-time less than 16 mm Hg. The operative time allowed for such patients would require further evaluation, but around 3 h has proven to be safe. VP shunts should not be a contraindication for laparoscopic surgery. However, it must be carried out with good anesthetic and monitoring facilities

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Uzzo RG, Bilsky M, Mininberg DT, Poppas DP. Laparoscopic surgery in children with ventriculoperitoneal shunts: Effect of pneumoperitoneum on intracranial pressure - Preliminary experience. Urology. 1997;49:753–7. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halverson A, Buchanan R, Jacobs L, Shayani V, Hunt T, Riedel C, et al. Evaluation of mechanism of increased intracranial pressure with insufflation. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:266–9. doi: 10.1007/s004649900648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura T, Nakajima K, Wasa M, Yagi M, Kawahara H, Soh H, et al. Successful laparoscopic fundoplication in children with ventriculoperitoneal shunts. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:215. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-4104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenthal RJ, Hiatt JR, Phillips EH, Hewitt W, Demetriou AA, Grode M. Intracranial pressure. Effects of pneumoperitoneum in a large-animal model. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:376–80. doi: 10.1007/s004649900367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moncure M, Salem R, Moncure K, Testaiuti M, Marburger R, Ye X, et al. Central nervous system metabolic and physiologic effects of laparoscopy. Am Surg. 1999;65:168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schöb OM, Allen DC, Benzel E, Curet MJ, Adams MS, Baldwin NG, et al. A comparison of the pathophysiologic effects of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and helium pneumoperitoneum on intracranial pressure. Am J Surg. 1996;172:248–53. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(96)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackman SV, Weingart JD, Kinsman SL, Docimo SG. Laparoscopic surgery in patients with ventriculoperitoneal shunts: Safety and monitoring. J Urol. 2000;164:1352–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser JD, Aguayo P, Sharp SW, Holcomb GW, III, Ostlie DJ, St Peter SD. The safety of laparoscopy in pediatric patients with ventriculoperitoneal shunts. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:675–8. doi: 10.1089/lap.2009.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neale ML, Falk GL. In vitro assessment of back pressure on ventriculoperitoneal shunt valves. Is laparoscopy safe? Surg Endosc. 1999;13:512–5. doi: 10.1007/s004649901024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Mufarrej F, Nolan C, Sookhai S, Broe P. Laparoscopic procedures in adults with ventriculoperitoneal shunts. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15:28–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sle.0000153733.78227.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]