Abstract

Purpose.

Cannabinoid CB1 receptors are found in abundance in the vertebrate eye, with most tissue types expressing this receptor. However, the function of CB1 receptors in corneal epithelial cells (CECs) is poorly understood. Interestingly, the corneas of CB1 knockout mice heal more slowly after injury via a mechanism proposed to involve protein kinase B (Akt) activation, chemokinesis, and cell proliferation. The current study examined the role of cannabinoids in CEC migration in greater detail.

Methods.

We determined the role of CB1 receptors in corneal healing. We examined the consequences of their activation on migration and proliferation in bovine CECs (bCECs). We additionally examined the mRNA profile of cannabinoid-related genes and CB1 protein expression as well as CB1 signaling in bovine CECs.

Results.

We now report that activation of CB1 with physiologically relevant concentrations of the synthetic agonist WIN55212-2 (WIN) induces bCEC migration via chemotaxis, an effect fully blocked by the CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716. The endogenous agonist 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) also enhances migration. Separately, mRNA for most cannabinoid-related proteins are present in bovine corneal epithelium and cultured bCECs. Notably absent are CB2 receptors and the 2-AG synthesizing enzyme diglycerol lipase-α (DAGLα). The signaling profile of CB1 activation is complex, with inactivation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Lastly, CB1 activation does not induce bCEC proliferation, but may instead antagonize EGF-induced proliferation.

Conclusions.

In summary, we find that CB1-based signaling machinery is present in bovine cornea and that activation of this system induces chemotaxis.

Keywords: migration, chemotaxis, corneal migration, eye, CB1, cannabinoid, 2-AG, endocannabinoid, wound healing, epithelium

Cannabinoid CB1 receptor activation induces chemotaxis, but is antiproliferative in corneal epithelial cells of the cow.

The human genome encodes approximately 1000 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), a large protein family of transmembrane receptors that often sense molecules outside the cell and activate intracellular signal transduction pathways, and, ultimately, cellular responses. The ligands that activate these GPCRs include photons, odors, pheromones, hormones, neurotransmitters, and, importantly, lipids. Endogenous lipids are relative newcomers as activators of GPCRs. One such endogenous lipid, anandamide (N-arachidonoylethanolamine [AEA]), is produced throughout the body and was identified as the first endogenous cannabinoid (eCB) by activating cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 GPCRs,1 followed by 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) a few years later.2,3 Twenty years after the discovery of the cannabinoid family of neuromodulatory lipids and their receptors, it now is appreciated that CB1 cannabinoid receptors are among the most abundant GPCRs in the central nervous system, and that they are involved in a vast array of fundamental biological processes, including pain, neurodegeneration, appetite and energy regulation, learning and memory, drug addiction, bone remodeling and osteoporosis, cancer, immune function, cardiovascular output, and reproduction.4,5

We have shown previously that the vertebrate eye expresses cannabinoid CB1 receptors in abundance, with most tissue types expressing this receptor.6,7 The functional roles of these receptors at some locations are known or suspected; for instance, it is likely that CB1 expressed in ciliary body and/or trabecular meshwork lowers IOP.8,9 However, the function of CB1 in other tissues is less well understood. For instance, CB1 receptors are abundant in corneal epithelial cells (CECs). Recent evidence indicates that CB1 activation enhances epithelial cell migration and thereby contributes to corneal wound healing,10,11 including evidence that CB1 knockout mice heal more slowly after corneal injury. The proposed mechanism is that CB1 induces chemokinesis (i.e., increased motility independent of direction) by transactivating epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptors via the protein kinase B (Akt) pathway. This is an appealing hypothesis that should be revisited and expanded upon. Unfortunately, cannabinoid pharmacology is treacherous and high concentrations (10 μM) of the nonselective cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN55212-2 (WIN) can have non-CB1/CB2–mediated actions.12 We have shown WIN to have a half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of 3 nM at CB1 in neurons.13,14 Some publications have used micromolar concentrations of WIN in brain slices where higher concentrations are required to penetrate tissue; however, in a cultured monolayer lipid penetration is not a concern. Yang et al.,10,11 therefore, used a concentration that was 3000-fold excess relative to the affinity of WIN for CB1. The pharmacology of cannabinoids is complex, with numerous examples of off-target effects. Indications that an excess of 1 μM WIN results in off-target effects appeared as early as 1998.15 Even drugs that have been treated as gold-standard selective agonists have been called into question. For instance, we have reported that JWH015, cited in over 50 publications as a CB2 agonist, including several in eye research,16,17 is a potent and efficacious CB1 agonist.18 Blockade by antagonists does not necessarily offer confidence, since, as we have shown, the widely used CB2 antagonist AM630 effectively blocks CB1 signaling at 1 μM.18 Separately, we have shown in the eye that topically WIN acts on an unknown target independent of CB1 or CB2.9

To investigate this further, we made use of primary CECs harvested from cows and cultured (bovine CECs [bCECs]). We tested the responses of these bCECs using migration and proliferation assays, with an emphasis on differentiating chemokinesis from chemotaxis. We also tested for the presence of components of the endocannabinoid signaling system. In addition to cannabinoid receptors, these include the assorted enzymes that produce and break down the eCBs (reviewed by Murataeva et al.19). We report here that many components of the endocannabinoid signaling system are present in CECs and that bCECs exhibit CB1-dependent chemotaxis.

Methods

Bovine CEC Harvesting

Bovine CECs were harvested from cow eyes obtained from healthy cows at a local farm that also houses a slaughtering facility. Eyes were obtained within several hours of the slaughter of the animals. Corneal epithelial cells were dissociated with a combination of trypsin (0.25%) treatment and scraping. Cells then were grown in supplemental hormone epithelial medium (SHEM media) containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; 44%), F-12 (44%), fetal bovine serum (10%), penicillin/streptomycin (1%), amphotericin (2.5 μg/mL), insulin (5 μg/mL), EGF (5 ng/mL), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; 0.5%).20–22 Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium is a frequent addition to SHEM media; however, because DMSO has been reported to be antiproliferative in endothelial and tumor cells (e.g., in prior reports23,24) we additionally grew cells in SHEM media lacking DMSO and repeated proliferation experiments in these cells.

Boyden Chamber Assay

In vitro cell migration assays were performed using a modified 96-well Boyden Chamber and PVP-free polycarbonate filters with 10-μm diameter pores (Neuroprobe, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). An estimation of the corneal epithelial cell concentration was determined using a hemocytometer. After trypsinization, an appropriate amount of serum-free SHEM medium was used to resuspend the cells at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL. The upper wells of the Boyden chamber were filled with 50 μL of suspension of 1 × 106 cells/mL in SHEM medium and the bottom wells were filled with 1, 10, and 100 nM 2-AG, WIN55212-2, and 100 nM of each compound along with a CB1 antagonist (1 μM SR141716), and then incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C for 3 hours. Following incubation, the filter was removed from the chamber and floated in 70% ethanol for 5 minutes and then in water for five more minutes. Nonmigrated cells were wiped from the upper side of the filter with ethanol-coated tissue. Cells then were fixed and stained using the Diff-Quik stain set. Finally, the filter was sectioned, mounted onto microscope slides, and the migrated cells counted in 10 nonoverlapping fields (×40 magnification) with a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) by multiple scorers blinded to experimental conditions.

Immunocytochemistry

For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 45 minutes at 4°C. Cells were blocked with SEABLOCK (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), followed by treatment with primary antibodies (in PBS, saponin, 0.2%) for 1 to 2 days at 4°C. Secondary antibodies (Alexa 405, 488, 594, or 647, 1:500; Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) were applied subsequently at room temperature for 1.5 hours or at 4°C for 1 to 2 days. CB1 antibodies have been characterized previously.25

Images were acquired with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) using Leica LAS AF software and a ×63 oil objective. Images were processed using ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/; provided in the public domain by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) and/or Photoshop (Adobe, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Images were modified only in terms of brightness and contrast.

Cell Proliferation Assay

Bovine CECs were plated in a 96-well plate in serum-free SHEM medium at a concentration of 10,000 cells/well. After 30 hours of incubation under various treatment conditions, the cells were labeled with nuclear marker DRAQ5 and imaged on an Odyssey scanner (LiCOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Signaling Assays

cAMP Assay.

Five-microliter cell suspension (10,000 cells/well) was incubated at room temperature (RT) for 30 minutes with agonist and forskolin (10 μM). Cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels were detected using Lance Ultra cAMP kit (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions and read on a Perkin Elmer EnSpire in TR-FRET mode.

Akt Kinase Assay.

This assay makes use of bead-based Alpha technology (Alphascreen; Perkin Elmer). Cells were plated at 50,000 cells/well and incubated with agonist for 5 minutes, and cells then were lysed with ×5 lysis buffer (supplied by vendor) with gentle rocking for 10 minutes. Then, 10 μL of this lysate was incubated with 10 μL Alphascreen acceptor beads and then incubated for 2 hours at RT. After the addition of 5 μL Alphascreen donor beads, the incubation was continued for another 2 hours at RT under subdued light conditions. Plates were read on an EnSpire in Alphascreen mode.

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Assay.

Cells were plated at 75,000 cells/well on a 96-well plate overnight in serum-free conditions and then treated with agonist 5 for minutes. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and then stained with phospho-ERK antibody (Lot 7, 1:200; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA) overnight. This was followed by incubation with IR800-tag secondary antibody for 1 hour. Finally, plates were imaged on a LiCOR Odyssey scanner as above.

Live-Imaging Migration Assay

In vitro cell migration also was visualized using an upright Nikon E800 microscope fitted with a Hamamatsu Orca-ER camera. The entire apparatus was covered in a grounded Faraday cage. Images were acquired using a ×4 objective over the course of 1 hour at 10-second intervals. Cell tracking analysis was done using the mTrackJ software plugin26 for ImageJ (available in the public domain at http://www.imagescience.org/meijering/software/mtrackj/). Drugs were embedded in a 1.5% agar block prepared from serum-free media. Cells were maintained in serum-free media overnight before plating into 60-mm Petri dishes coated with poly-D lysine. Cells were observed for approximately 15 minutes before addition of a block of agar to the edge of the dish. Placement of agar block was varied to rule out the possibility of migration due to some other environmental factor, such as electric fields. In some instances the block was moved during the experiment to observe whether the cells changed the direction of their movement.

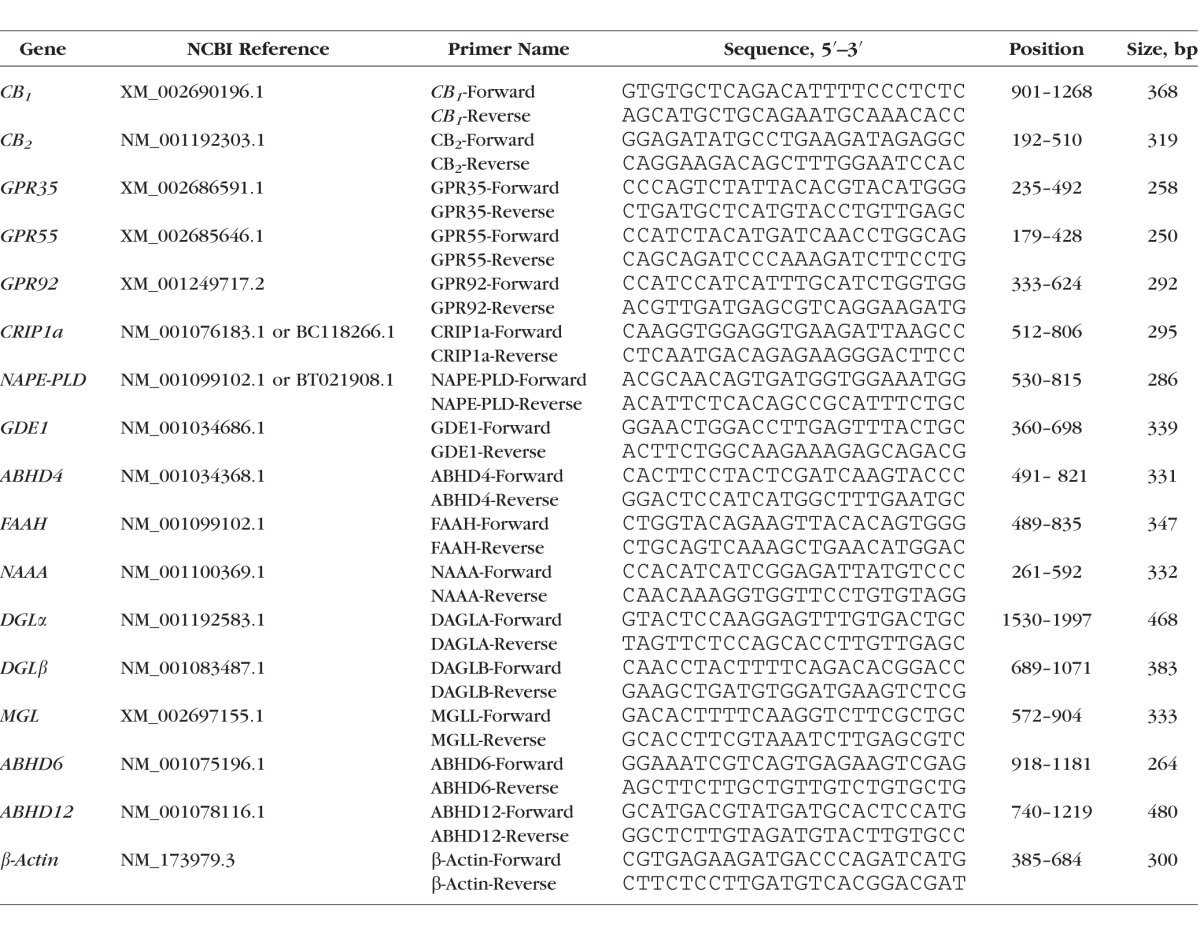

RT-PCR Assay

Primers were designed against CB1 and 15 additional cannabinoid-related bovine genes (CB2, GPR35, GPR55, GPR92, CRIP1a, NAPE-PLD, GDE1, ABHD4, FAAH, NAAA, DGLα, DGLβ, MGL, ABHD6, ABHD12). Primer sequences, are listed in the Table. β-Actin is a housekeeping gene used as an internal control. Expression of mRNAs was determined by RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from bovine corneal epithelium, corneal endothelium, retina, and trabecular meshwork, respectively, using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) and RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription PCR was done in two steps. The first strand DNA was made using High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using 200 ng RNA in a 20 μL reaction. Polymerase chain reaction was performed following the AmpliTaq 360 DNA Polymerase Protocol (Applied Biosystems). Then, 1 μL respective bovine ocular tissue cDNA was added into a 25-μL PCR reaction that was processed through 40-cycle amplification. Polymerase chain reaction products were examined on 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr).

Table.

Primers Designed for Assorted Endocannabinoid-Related Bovine Genes

Statistical Analysis

Values are reported as mean ± SEM. For statistical analyses where several conditions were tested against a control, we used a 1-way ANOVA followed by a Dunnett's post hoc test against that control column. For analyses involving multiple conditions compared against one another we used a 1-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test of all columns against one another and reported the relevant statistical outcome.

Drugs

2-arachidonoylglycerol was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). WIN55212-2 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA). SR141716 was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; Bethesda, MD, USA) Research Resources Drug Supply Program.

Results

CB1 Activation Induces Chemotaxis in Bovine CECs in a Boyden Chamber Assay

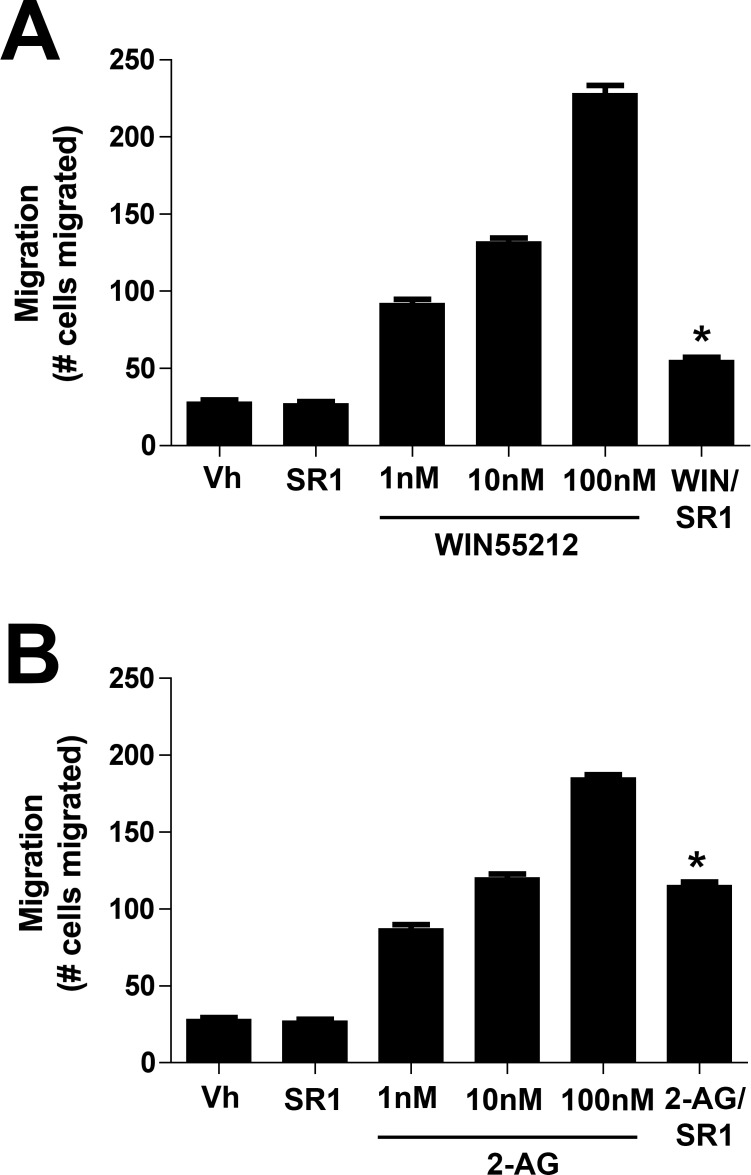

We first tested whether CB1 activation induced cell migration by exposing cells in a Boyden Chamber to various concentrations of the CB1 receptor agonist WIN55212-2. The Boyden chamber assay places cells on one side of a membrane that has pores of a defined size, to permit migration to the other side. The drug of interest is placed on the other side of the membrane, creating a chemical gradient. Migration through these pores often is considered an indication of chemotaxis; that is, a test of migration within a chemical gradient. We found that cell migration was enhanced in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1) by WIN55212-2 and 2-AG. Migration produced by the highest concentration tested (100 nM) was completely blocked by cotreatment with CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 (SR1, 1 μM). We did not test higher concentrations, since as noted above we have calculated the EC50 for WIN55212-2 at CB1 receptors to be approximately 3 nM. We also tested whether the endogenous CB1 agonist 2-AG enhances migration, finding that it does. Interestingly, 2-AG was efficacious even at 100 nM, a concentration below our calculated EC50 for 2-AG–mediated inhibition of synaptic transmission via CB1 receptors.13 In contrast to WIN55212-2, the migration effect of 2-AG was not blocked completely by SR141716, raising the possibility that 2-AG acts in part via an additional receptor.

Figure 1.

Activation of CB1 induces chemotaxis in bovine CECs in a Boyden chamber assay. (A) The CB1 agonist WIN55212-2 enhances bCEC migration in a concentration-dependent manner during a 3-hour incubation. This enhancement is fully blocked by the CB1 antagonist SR141716 (SR1, 1 μM). (B) The endocannabinoid 2-AG induces a similar migration at the relatively low concentration of 100 nM. This migration is partly blocked by SR141716 (1 μM). *P < 0.05, unpaired t-test versus corresponding 100 nM drug.

WIN55212-2 Induces Chemotaxis in Bovine CECs in an In Vitro Gradient Assay

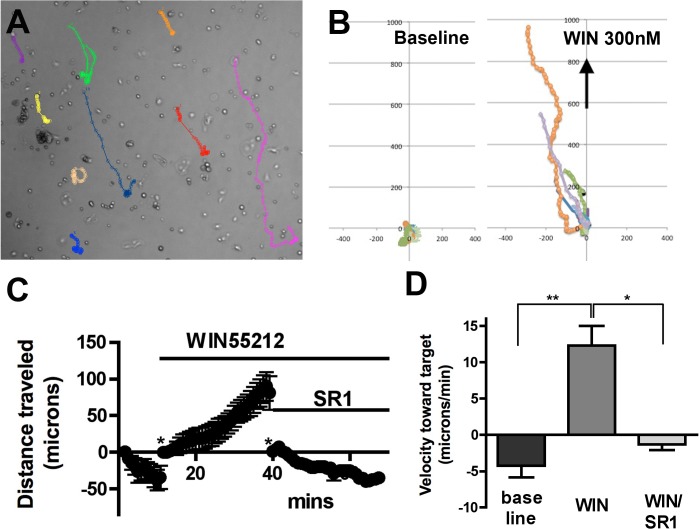

Our Boyden Assay results raised the possibility that cells are migrating due to chemotaxis, though it is possible that the drug simply enhances cell motility, resulting in some cells passing through the pores of the membrane. To distinguish chemotaxis from chemokinesis more precisely we examined the movement of cells in response to a drug gradient in a Petri dish. The migration of bCECs was observed in real time under control and drug conditions as a vehicle/drug-impregnated block of agar was placed at the edge of the dish. We found that a block of 1.5% agar embedded with 300 nM WIN55212-2 induced migration of bCECs toward the block, consistent with chemotaxis rather than chemokinesis (Fig. 2). A block embedded with vehicle did not induce chemotaxis (migration toward target, −0.95 ± 0.41 μm/min, n = 8). In the example shown in Figure 2, a 300 nM WIN55212-2 gradient enhanced the net velocity toward the target, while addition of SR141716 (500 nM) to the bath stopped further migration toward the target (Figs. 2C, 2D; baseline, −4.2 ± 1.6 μm/min; WIN, 12.3 ± 2.7 μm/min; WIN/SR1, −1.3 ± 0.7 μm/min; P < 0.001 WIN versus baseline, P < 0.01 WIN versus WIN/SR, 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test). Three hundred nanometers WIN55212 added directly to the bath did not increase movement (speed independent of direction; baseline, 4.0 ± 0.8 μm/min; WIN 300 nM, 3.9 ± 0.4 μm/min).

Figure 2.

WIN55212-2 induces chemotaxis in bovine CECs in an in vitro gradient assay. (A) Sample diagram showing tracking of individual cells in response to WIN55212-2 (WIN) placed in upper end of dish. (B) Summary data from (A), showing migration before (left panel) and after (right panel) drug toward the target (direction denoted by arrow), with start-points normalized to origin (0,0). (C) Time course showing distance traveled toward the WIN target under baseline, WIN, and WIN/SR141716 conditions. *Distance was returned zero to facilitate comparison. (D) Summary of velocity toward target during final five minutes of each condition. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

mRNA for Most Components of a Cannabinoid Signaling System Is Present in the Eye of the Cow

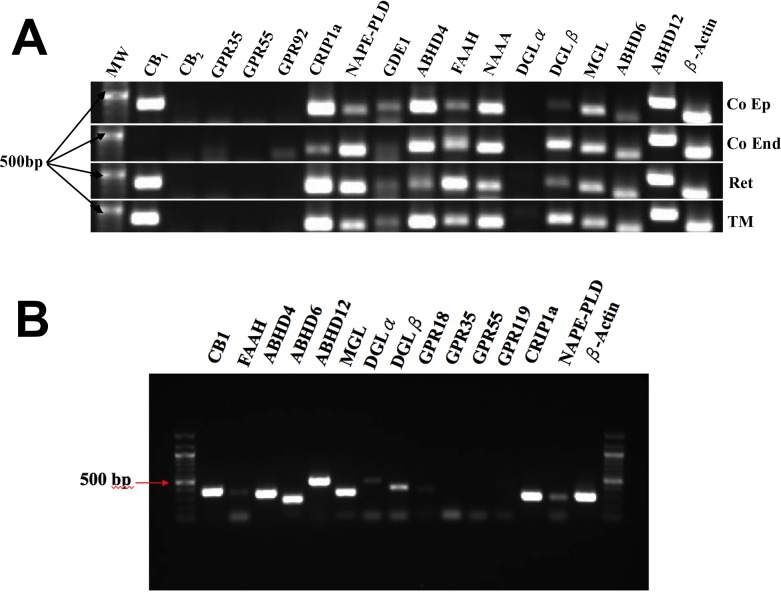

Using RT-PCR we tested for the presence of mRNA for the principal components of the cannabinoid signaling system (Fig. 3A). In terms of receptors, we only detected message for CB1, not CB2, GPR35, GPR55, or GPR92, though a faint band may be present in corneal endothelium for GPR92. The latter three have been proposed at various times to be cannabinoid-related receptors (reviewed previously).27

Figure 3.

Messenger RNA expression for various cannabinoid-related proteins in the eye of the cow. (A) We tested for mRNA expression in four bovine ocular tissues, corneal epithelium (Co Ep), and endothelium (Co End), retina, and trabecular meshwork (TM). Genes and their hypothesized roles are described in the text. (B) We also examined expression of a subset of these mRNAs in cultured bovine epithelial cells.

We saw signal for all of the major proposed enzymes for the breakdown of the eCB 2-AG: MAGL, ABHD6, and ABHD12.28 We also see evidence for expression of two enzymes thought to metabolize AEA, fatty acid amine hydrolase (FAAH), and N-acetylethanolamine acid amidase (NAAA).29,30 The production of AEA is less well understood, but three enzymes have been implicated: NAPE-PLD, GDE1, and ABHD4.30–32 These also appear to be expressed to varying extents in bovine ocular tissues. The notable exception here is on the production side for 2-AG, thought to occur via DGLα and/or DGLβ. DGLα appears to be absent from all ocular tissues and the bands for DGLβ are in some cases relatively faint. The cannabinoid receptor interacting protein 1a (CRIP1a) was described as a potential modifier of cannabinoid signaling33 though the mechanism of action and the extent of its association with CB1 in a given tissue remains unclear. We find that CRIP1a also is expressed in bovine ocular tissues.

A similar profile was seen in cultured bCECs (Fig. 3B). However, a faint band was detected for DGLα, suggesting that its expression may be upregulated under culture conditions.

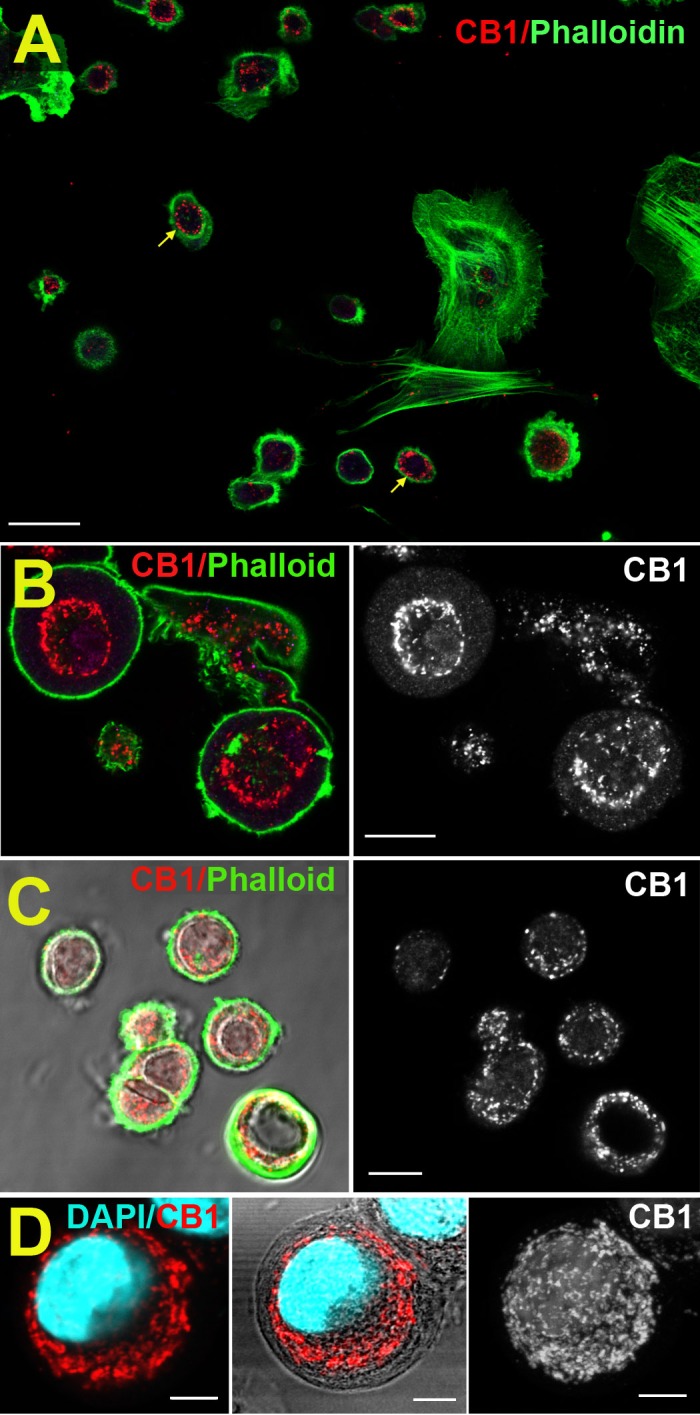

CB1 Protein Expression in Cultured bCECs

We have shown previously that CB1 is expressed in human CECs,7 but have not examined CB1 expression in cultured bovine CECs that have been plated as in preparation for a migration assay, to mimic those conditions. We used a previously characterized antibody against CB1 and found that CB1 expression occurs in a subset of cells, most prominently in the rounded cells, which are most likely to migrate (Fig. 4). The staining occurs within the cell in a perinuclear pattern, though at some distance from the nucleus (Fig. 4D). A predominantly intracellular expression is an unusual distribution for CB1, usually mostly present on cell membranes.

Figure 4.

CB1 protein expression in cultured bCECs. (A) Overview shows CB1 expression (red, arrows) in a subset of cultured bCECs, outlined by phalloidin (green). (B) Higher magnification image shows ring-like CB1 expression (red). (C) CB1/phalloidin overlaid on DIC image (left); CB1 only (right). (D) CB1/DAPI (left). Same with DIC (middle). Flat Z stack of CB1 in same cell (right). Scale bars: 20 μm (A), 10 μm (B, C), 5 μm (D).

An Unusual Intracellular Signaling Profile for CB1 in Bovine Corneal Epithelial Cells

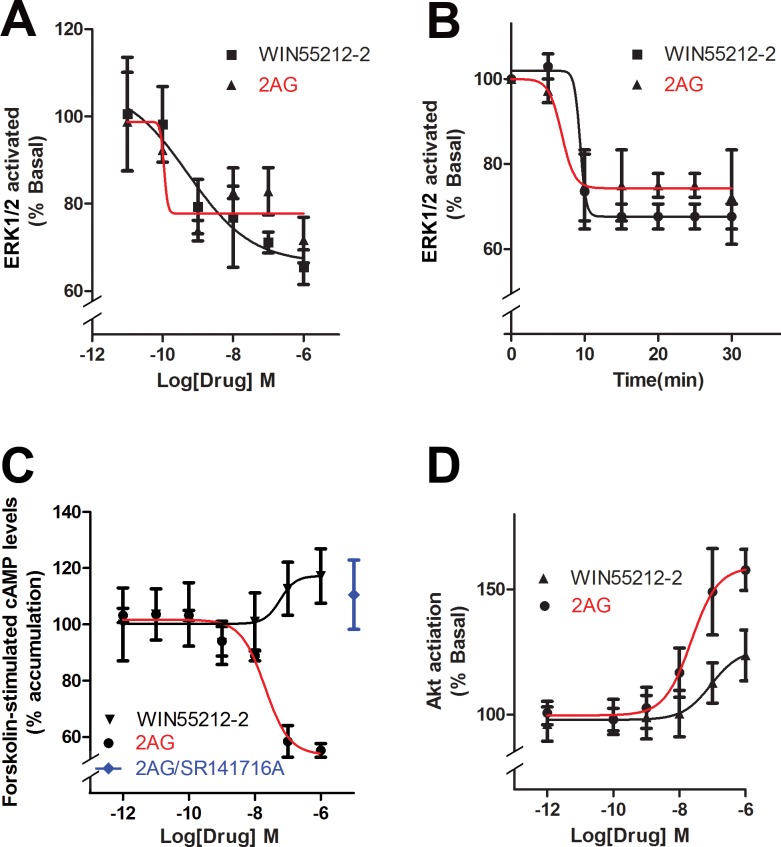

Cannabinoid receptors are known to activate several intracellular signaling pathways.34 We found that the ERK1/2 pathway, which generally is activated by cannabinoids5 was in fact inactivated as indicated by a dephosphorylation of ERK1/2. Dephosphorylation of ERK1/2 was rapid, occurring in a concentration-dependent manner within four minutes of treatment by WIN or 2-AG (Fig. 5A; EC50 [WIN], 0.5 nM; EC50 [2-AG], 0.2 nM). Because signaling can vary over time, we revisited the ERK1/2 signaling examining a time course using 1 μM concentrations of WIN and 2-AG. We found that the inhibition was established within the first 10 minutes and maintained as long as 30 minutes (Fig. 5B). We also examined the effect of CB1 activation on cAMP levels using forskolin stimulation. The Gi/o-coupled CB1 receptor is expected to lower cAMP levels by inhibiting adenylyl cyclase.5 Interestingly, we found that 2-AG lowered cAMP but that WIN elevated cAMP at higher concentrations (Fig. 5C; EC50 [2-AG], 20 nM). The 2-AG action was prevented by pretreatment with CB1 antagonist SR141716 (Fig. 5C, 1 μM for each drug). Again, this is consistent with off-target action for WIN at high concentrations. Yang et al.10,11 have previously reported that the CB1 receptor agonist WIN activates the Akt pathway. However, as noted above, the study used 10 μM WIN, a concentration that is susceptible to off-target action. Since the low concentrations that stimulated bCEC migration (e.g., 1 and 10 nM) did not stimulate Akt phosphorylation, it is unlikely that Akt activation is required for the bCEC migration that we have observed. Nonetheless, high WIN concentrations can stimulate Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 5D). In addition, 2-AG activates Akt in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5D; EC50 [2-AG], 23 nM).

Figure 5.

Cannabinoids have an unusual intracellular signaling activation profile in bovine corneal epithelial cells. (A) Instead of activating MAPK, WIN, and 2-AG dephosphorylate MAPK in bCECs. (B) Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition occurs rapidly and persists to 30 minutes. (C) 2-arachidonoylglycerol, but not WIN, reduces cAMP levels in forskolin-treated cells. (D) 2-arachidonoylglycerol activates Akt, but WIN does so only modestly at higher concentrations.

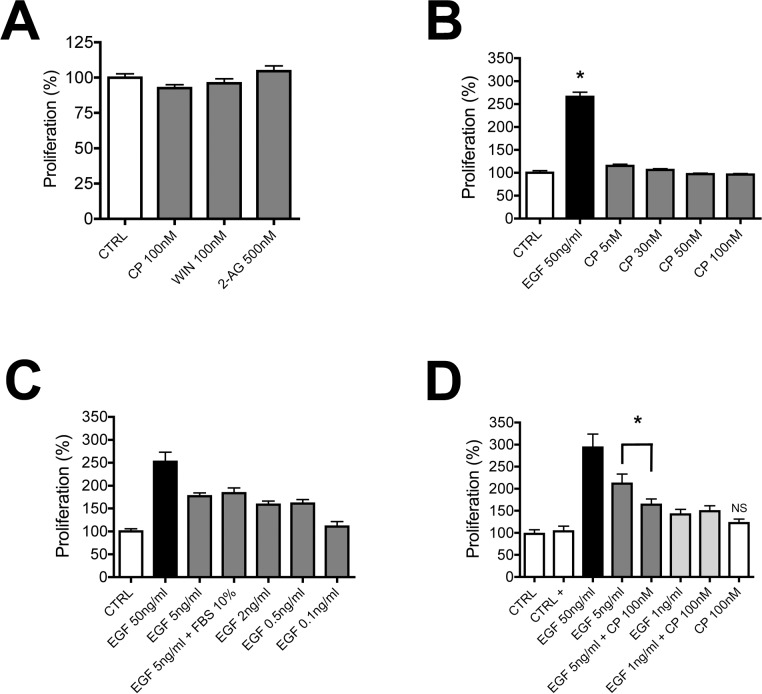

Cell Proliferation

Yang et al.10,11 reported that WIN55212-2 increased cell proliferation, an exciting finding with considerable implications for wound healing. We revisited this experiment to ascertain whether these results seen in a tumor cell line also would be seen in primary corneal cultures. We initially tested this in cells grown in SHEM media that contained 0.5% DMSO and found that, while EGF enhances proliferation, WIN (100 nM) and 2-AG (500 nM) do not (data not shown; EGF, 131 ± 5; WIN, 111 ± 10; 2-AG, 114 ± 9; P > 0.05 for WIN and 2-AG versus control, 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test). We repeated and expanded on these experiments in cells grown without DMSO, since DMSO may interfere with cell proliferation23,24 (see note in Methods). In addition, since as mentioned above WIN55212 may have an alternate target in anterior eye, we also tested CP55940 (both at 100 nM), finding that neither induced proliferation (Fig. 6A). We tested a range of CP55940 concentrations, all without effect, while EGF (50 ng/mL) induced a robust increase in proliferation (Fig. 6B; % increase in proliferation for EGF [50 ng/mL], 266 ± 10; *P < 0.05 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test versus control). We additionally tested several concentrations of EGF to determine the concentrations that induced half-maximal or low proliferation (5 and 1 ng/mL, respectively), allowing us to test for potential interactions between CP55940 (100 nM) and EGF. In these last experiments we additionally included BSA as a carrier to test the possibility whether the lack of effect for the CP55940 is perhaps due to poor carriage of this lipophilic compound. We found that addition of BSA did not enhance proliferation by CP55940 (Fig. 6D; % increase in proliferation for CP [100 nM], 122 ± 9; P > 0.05 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test). Also, CP55940 did not enhance EGF-induced proliferation at 1 or 5 ng/mL of EGF. Instead, CP55940 antagonized the half-maximal 5 ng/mL EGF effect (Fig. 6D; % increase in proliferation for EGF [5 ng/mL], 212 ± 22; for EGF + CP [100 nM], 164 ± 13; P < 0.01 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test). This raises the possibility that CB1 activation is promigratory and antiproliferative.

Figure 6.

Activation of CB1 does not enhance proliferation of bCECs. (A) In a proliferation assay, CP55940 (100 nM) and WIN55212 (100 nM) do not enhance bCEC proliferation. (B) A concentration-response profile for CP55940 again shows no effect on proliferation, while EGF (50 ng/mL) enhances proliferation. (C) Epidermal growth factor enhances proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner in our preparation. (D) CP55940 (100 nM) in combination with half-maximal (5 ng/mL) or low (1 ng/mL) EGF does not enhance proliferation. (B) *P < 0.05 1-way ANOVA/Dunnett's post hoc versus control. (D) Not significant (NS), 1-way ANOVA/Bonferroni post hoc between EGF 5 ng/mL and EGF 5 ng/mL + CP (100 nM).

Discussion

Our key findings are that mRNA for most components of the endocannabinoid signaling system are present in bovine corneal epithelial cells (as well as other ocular tissues) and that CB1 induces chemotaxis rather than chemokinesis in corneal epithelial cells.

We previously demonstrated the presence of CB1 receptors in human corneal epithelium.7 As noted above, compelling evidence has been presented that these receptors have a role in corneal wound healing, since the corneas of CB1 knockout mice heal more slowly after injury. However, the precise role of CB1 in the cornea remains unclear. It also is unclear whether CB1 activation may have a salutary role in corneal health. This question is not academic—CB1 receptors are perhaps best known as the endogenous targets for the drugs of abuse marijuana and hashish. These drugs are used regularly by tens of millions worldwide. Furthermore, there is continuing interest in cannabinoids as an ocular therapeutic given their known beneficial IOP-lowering properties, with consequent implications for glaucoma. If cannabinoids or cannabinoid-based drugs, taken recreationally or as part of a therapeutic regimen, induce alterations in corneal processes, then it will be advantageous, even essential, to learn the precise workings of these alterations. Yang et al.10 have offered evidence that CB1 acts via the EGF receptor through a form of transactivation and that this results in a net enhancement of cell movement, but that the direction of this movement is determined by other signals, such as electric fields.35 As noted above, however, the high drug concentrations used by Yang et al.10 raise serious questions about drug specificity and require replication of their work with lower drug concentrations. Our experiments using the Boyden assay and live imaging gradient assays indicated that endocannabinoids may have a role in corneal wound healing, not by enhancing the rate of migration per se, but by serving as a chemoattractant—essentially a target—for migrating CECs. Our results raise a question of what role these have in vivo and perhaps, more importantly, what is the source of cannabinoids? Presumably, the objective of a chemoattractant in this context is to promote movement toward the site of injury. What is the source of 2-AG? Our RT-PCR results indicate that nearly all components of cannabinoid signaling are present in several ocular tissues of the cow. The expression profile is similar for corneal epithelium and endothelium, as well as in trabecular meshwork and retina. DGLα has been implicated as the chief enzyme producing 2AG in the CNS,36 while DGLβ has a more prominent role in liver and immune cells.37,38 The balance between these enzymes has not been studied systematically across tissues of the body and may vary even within different portions of the CNS. It appears that in the cow eye the balance is in favor of DGLβ, but the possibility exists that the synthesis of 2-AG occurs in some other tissue, such as the lacrimal ducts or meibomian glands, the latter known to produce a considerable variety of lipids.39 The absence of DGLα in retina is surprising, since we detected DGLα protein in the retina of the mouse in an earlier study.25 This may be due to species differences or perhaps a diurnal variation in message/protein expression in the nocturnal mouse versus the diurnal cow. Alternatively, the delays inherent in obtaining cow eyes may have a greater impact on some tissues, such as retina. The presence of so many components of the cannabinoid signaling machinery may be an indication that these enzymes are required for more general lipid metabolism. Absence of MAGL has been shown to profoundly alter the prostaglandin levels in tissues where it is prominent, by depriving cyclooxygenase of its substrate, arachidonic acid.40 The presence of these components in each tissue also may be an indication of local “circuitry” in the sense that cannabinoids are produced, function, and are broken down within a given tissue rather than being produced at some central ocular site and acting globally.

The circular intracellular pattern of CB1 protein expression is intriguing. CB1 in neurons at least is best known as a membrane bound GPCR that modulates neurotransmission.41,42 However, there is growing evidence for intracellular CB1, including association with intracellular structures, such as mitochondria.43

Our finding that CB2 is not present in the anterior eye or retina of the cow is consistent with our functional observation that CB2 does not have a role in regulating IOP.9 It also is consistent with three studies that tested for message in mammalian tissue. It contradicts several studies that have used a porcine culture model and pharmacology to support a central role for CB2 in regulating IOP. The latter studies relied heavily on a nominally selective CB2 agonist JWH015 that we have shown to be a potent and efficacious agonist of CB1.18

Our examination of signaling pathways activated by cannabinoids has yielded an interesting picture. In contrast to Yang et al.,10 we find that concentrations of the agonist WIN55212-2 that stimulate bCEC migration have no effect on Akt phosphorylation. Only at the highest WIN55212-2 concentrations does one begin to see a modest effect on Akt. This argues against a central role for CB1 Akt activation in corneal epithelial migration and highlights an important pitfall, the well-known promiscuity of cannabinoids, that eye researchers will encounter when dealing with cannabinoids in future studies. It is not sufficient to “block” a 10-μM concentration of drug with 10 μM concentration of antagonist and conclude that a physiological effect has been observed. Our finding that ERK1/2 was dephosphorylated in a concentration-dependent manner is one of our more surprising findings and may be related to the chiefly intracellular expression pattern for CB1. The coupling of intracellular CB1 may be different from membrane-bound CB1. Growing evidence points to activation of ERK1/2 as a key step in the induction of corneal epithelial migration by TGF-β (Joko et al.44). Our results suggest that, if anything, CB1 activation should oppose TGF-β induced migration since it depends on ERK1/2.

We have measured cell proliferation in our preparation, with the finding that EGF promotes proliferation, but the CB1 agonists WIN55212-2, CP55940, and 2-AG do not. Indeed, if anything CB1 activation appears to antagonize EGF-induced proliferation. The use of high concentrations of WIN55212-2, potentially acting at an off-target site, may explain the difference between our results and those of Yang et al.10 However, it also is possible that the difference is a function of species difference or the use of an immortalized cell line by Yang et al.10 In view of our failure to replicate several key findings of immortalized cell lines using bCECs, it would certainly be interesting to see those results replicated at lower concentrations. Our findings also demonstrate the importance of using primary cultures.

In summary, we have confirmed that CB1 activation alters migration of bCECs. However, rather than generally enhancing their migration, CB1 agonists induce directed migration or chemotaxis. We have further found that CB1 activation does not promote proliferation, but instead antagonizes EGF-stimulated proliferation. CB1 activation may, therefore, be promigratory, but antiproliferative. Our results are consistent with a positive role for CB1 in corneal wound healing but may involve a very different mechanism. It will be important to dissect the details and the pathways of this signaling in the vertebrate cornea.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Eye Institute (NEI; Bethesda, MD, USA) Grants EY021831 and EY24625 (AS), and National Institutes of Health (NIH; Bethesda, MD, USA) Grants DA011322 and DA021696 (KM).

Disclosure: N. Murataeva, None; S. Li, None; O. Oehler, None; S. Miller, None; A. Dhopeshwarkar, None; S.S.-J. Hu, None; J.A. Bonanno, None; H. Bradshaw, None; K. Mackie, None; D. McHugh, None; A. Straiker, None

References

- 1. Devane WA,, Hanus L,, Breuer A,, et al. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992; 258: 1946–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stella N,, Schweitzer P,, Piomelli D. A second endogenous cannabinoid that modulates long-term potentiation. Nature. 1997; 388: 773–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sugiura T,, Kondo S,, Sukagawa A, et al. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995; 215: 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kano M,, Ohno-Shosaku T,, Hashimotodani Y,, Uchigashima M,, Watanabe M. Endocannabinoid-mediated control of synaptic transmission. Physiol Rev. 2009; 89: 309–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Howlett AC,, Breivogel CS,, Childers SR,, Deadwyler SA,, Hampson RE,, Porrino LJ. Cannabinoid physiology and pharmacology: 30 years of progress. Neuropharmacology. 2004; 47(s uppl 1): 345–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Straiker A,, Stella N,, Piomelli D,, Mackie K,, Karten HJ,, Maguire G. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors and ligands in vertebrate retina: localization and function of an endogenous signaling system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999; 96: 14565–14570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Straiker AJ,, Maguire G,, Mackie K,, Lindsey J. Localization of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the human anterior eye and retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999; 40: 2442–2448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hepler RS,, Frank IR. Marihuana smoking and intraocular pressure. Jama. 1971; 217: 1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hudson BD,, Beazley M,, Szczesniak AM,, Straiker A,, Kelly ME. Indirect sympatholytic actions at beta-adrenoceptors account for the ocular hypotensive actions of cannabinoid receptor agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011; 339: 757–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang H,, Wang Z,, Capo-Aponte JE,, Zhang F,, Pan Z,, Reinach PS. Epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation by the cannabinoid receptor (CB1) and transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) induces differential responses in corneal epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2010; 91: 462–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang Y,, Yang H,, Wang Z, et al. Cannabinoid receptor 1 suppresses transient receptor potential vanilloid 1-induced inflammatory responses to corneal injury. Cell Signal. 2013; 25: 501–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hajos N,, Ledent C,, Freund TF. Novel cannabinoid-sensitive receptor mediates inhibition of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2001; 106: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Straiker A,, Mackie K. Cannabinoid signaling in inhibitory autaptic hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 2009; 163: 190–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Straiker A,, Mackie K. Depolarization-induced suppression of excitation in murine autaptic hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 2005; 569: 501–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shen M,, Thayer SA. The cannabinoid agonist Win55,212-2 inhibits calcium channels by receptor-mediated and direct pathways in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 1998; 783: 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhong L,, Geng L,, Njie Y,, Feng W,, Song ZH. CB2 cannabinoid receptors in trabecular meshwork cells mediate JWH015-induced enhancement of aqueous humor outflow facility. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 1988–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. He F,, Song ZH. Molecular and cellular changes induced by the activation of CB2 cannabinoid receptors in trabecular meshwork cells. Mol Vis. 2007; 13: 1348–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murataeva N,, Mackie K,, Straiker A. The CB2-preferring agonist JWH015 also potently and efficaciously activates CB1 in autaptic hippocampal neurons. Pharmacol Res. 2012; 66: 437–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murataeva N,, Straiker A,, Mackie K. Parsing the players: 2-AG synthesis and degradation in the CNS. Br J Pharmacol. 2013; 171: 1379–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakatsu MN,, Gonzalez S,, Mei H,, Deng SX. Human limbal mesenchymal cells support the growth of human corneal epithelial stem/progenitor cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55: 6953–6959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Loureiro RR,, Cristovam PC,, Martins CM, et al. Comparison of culture media for ex vivo cultivation of limbal epithelial progenitor cells. Mol Vis. 2013; 19: 69–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li S,, Gallup M,, Chen YT,, McNamara NA. Molecular mechanism of proinflammatory cytokine-mediated squamous metaplasia in human corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 2466–2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eter N,, Spitznas M. DMSO mimics inhibitory effect of thalidomide on choriocapillary endothelial cell proliferation in culture. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002; 86: 1303–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Teraoka H,, Mikoshiba M,, Takase K,, Yamamoto K,, Tsukada K. Reversible G1 arrest induced by dimethyl sulfoxide in human lymphoid cell lines: dimethyl sulfoxide inhibits IL-6-induced differentiation of SKW6-CL4 into IgM-secreting plasma cells. Exp Cell Res. 1996; 222: 218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hu SS,, Arnold A,, Hutchens JM, et al. Architecture of cannabinoid signaling in mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2010; 518: 3848–3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meijering E,, Dzyubachyk O,, Smal I. Methods for cell and particle tracking. Methods Enzymol. 2012; 504: 183–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mackie K,, Stella N. Cannabinoid receptors and endocannabinoids: evidence for new players. Aaps J. 2006; 8: E298–E306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blankman JL,, Simon GM,, Cravatt BF. A comprehensive profile of brain enzymes that hydrolyze the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Chem Biol. 2007; 14: 1347–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cravatt BF,, Demarest K,, Patricelli MP, et al. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001; 98: 9371–9376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsuboi K,, Sun YX,, Okamoto Y,, Araki N,, Tonai T,, Ueda N. Molecular characterization of N-acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase a novel member of the choloylglycine hydrolase family with structural and functional similarity to acid ceramidase. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280: 11082–11092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Simon GM,, Cravatt BF. Anandamide biosynthesis catalyzed by the phosphodiesterase GDE1 and detection of glycerophospho-N-acyl ethanolamine precursors in mouse brain. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283: 9341–9349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu J,, Wang L,, Harvey-White J, et al. Multiple pathways involved in the biosynthesis of anandamide. Neuropharmacology. 2008; 54: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Niehaus JL,, Liu Y,, Wallis KT,, et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptor activity is modulated by the cannabinoid receptor interacting protein CRIP 1a. Mol Pharmacol. 2007; 72: 1557–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Howlett AC. The cannabinoid receptors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002; 68–69: 619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reid B,, Vieira AC,, Cao L,, Mannis MJ,, Schwab IR,, Zhao M. Specific ion fluxes generate cornea wound electric currents. Commun Integr Biol. 2011; 4: 462–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bisogno T,, Howell F,, Williams G, et al. Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J Cell Biol. 2003; 163: 463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gao Y,, Vasilyev DV,, Goncalves MB,, et al. Loss of retrograde endocannabinoid signaling and reduced adult neurogenesis in diacylglycerol lipase knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2010; 30: 2017–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hsu KL,, Tsuboi K,, Adibekian A,, Pugh H,, Masuda K,, Cravatt BF. DAGLbeta inhibition perturbs a lipid network involved in macrophage inflammatory responses. Nat Chem Biol. 2012; 8: 999–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Butovich IA. Lipidomic analysis of human meibum using HPLC-MSn. Methods Mol Biol. 2009; 579: 221–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nomura DK,, Lombardi DP,, Chang JW, et al. Monoacylglycerol lipase exerts dual control over endocannabinoid and fatty acid pathways to support prostate cancer. Chem Biol. 2011; 18: 846–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wilson RI,, Kunos G,, Nicoll RA. Presynaptic specificity of endocannabinoid signaling in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2001; 31: 453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wilson RI,, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001; 410: 588–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Benard G,, Massa F,, Puente N, et al. Mitochondrial CB(1) receptors regulate neuronal energy metabolism. Nat Neurosci. 2012; 15: 558–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Joko T,, Shiraishi A,, Akune Y,, et al. Involvement of P38MAPK in human corneal endothelial cell migration induced by TGF-beta(2). Exp Eye Res. 2013; 108: 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]