Abstract

Code teams respond to acute life threatening changes in a patient’s status 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. If any variable, whether a medical skill or non-medical quality, is lacking, the effectiveness of a code team’s resuscitation could be hindered. To improve the overall performance of our hospital’s code team, we implemented an evidence-based quality improvement restructuring plan. The code team restructure, which occurred over a 3-month period, included a defined number of code team participants, clear identification of team members and their primary responsibilities and position relative to the patient, and initiation of team training events and surprise mock codes (simulations). Team member assessments of the restructured code team and its performance were collected through self-administered electronic questionnaires. Time-to-defibrillation, defined as the time the code was called until the start of defibrillation, was measured for each code using actual time recordings from code summary sheets. Significant improvements in team member confidence in the skills specific to their role and clarity in their role’s position were identified. Smaller improvements were seen in team leadership and reduction in the amount of extra talking and noise during a code. The average time-to-defibrillation during real codes decreased each year since the code team restructure. This type of code team restructure resulted in improvements in several areas that impact the functioning of the team, as well as decreased the average time-to-defibrillation, making it beneficial to many, including the team members, medical institution, and patients.

Keywords: Code team, Defibrillation time, Evaluations, Mock codes, Organization, Restructure

We believe that an effective code team is one that saves lives quickly, efficiently, and safely, thereby reversing clinical death and limiting disability. For a code team to achieve this, they must be (1) organized, (2) proficient with knowledge and skills, and (3) effective in communication. However, even though code teams generally face a relatively common set of circumstances and series of events, so accordingly, therapies for these have been standardized (eg, Advanced Cardiac Life Support [ACLS]), teams are arriving quickly to provide lifesaving support to patients they likely do not know, in potentially unfamiliar locations, and with team members who do not know each other or work with each other routinely.1,2

Therefore, in early 2007, our hospital initiated a quality improvement (QI) program to assess and address code team performance and response. One component of this program was frequent surprise mock codes. A mock code is a simulation of a real code, providing an inter-professional learning environment that is interactive, closely resembles real clinical situations, and allows opportunity for formative assessment of the participants.3–6 The mock codes were conducted in various nursing units throughout the hospital, and multiple issues were identified. The major deficits in the code team’s performance included: (1) deficits in following the ACLS algorithm and/or guidelines; (2) delays and/or interruptions in CPR; (3) delays in the first defibrillation; (4) delayed intravenous (IV) access or IV access not done at all; (5) deficits in universal precautions (eg, lack of use of gloves and/or masks); (6) poor team leadership and organization; (7) lack of team member role identification; (8) too many unnecessary personnel at the code; and, (9) too much noise and unnecessary talking in the room during a code.

Non-medical skills, including communication, leadership, team interaction, and task coordination, play as much of a role during a code response as medical skills such as chest compressions and early defibrillation. If any of these skill variables is lacking, possibly due to the fact that resuscitations may not be a frequent occurrence for all team members, and stress among staff during these events is high, the effectiveness of a code team’s performance could be hindered.2,3,7–9

Standard American Heart Association (AHA) ACLS courses are an excellent tool to assist learners in the algorithm content and team response concepts. However, the course’s concepts are difficult to translate into “real” life practices, because the classroom setting does not allow for all code team members to practice together, nor does it incorporate all of the code team roles into the course. Additionally, ACLS courses are not held in the patient care setting, so staff do not use equipment and carryout procedures specific to their workplace.5 Also, little information is available about code team role identification and definition. Several studies and hospital best practices have been published about improved code team function,7–10 but they focus mainly on the use of simulation training, with others focusing on patient survival statistics.11–13

To increase the overall performance and effectiveness of our hospital’s code team, we felt it was necessary to focus on team organization to ultimately provide timely, uninterrupted, high quality CPR, defibrillation, and correction of reversible causes. Therefore, assuming that clear role assignment and proper positioning of team members is crucial to organized and efficient care of the patient, our objectives were to (1) clearly delineate code team member roles and positions, and improve role identification; (2) improve leadership skills; (3) improve team dynamics and organization through the establishment of mock code practice sessions; and (4) decrease the number of unnecessary individuals responding to codes. We postulated that these changes would lead to improved team member dynamics, earlier defibrillation, and faster, safer, more efficient saving of lives.

Methods

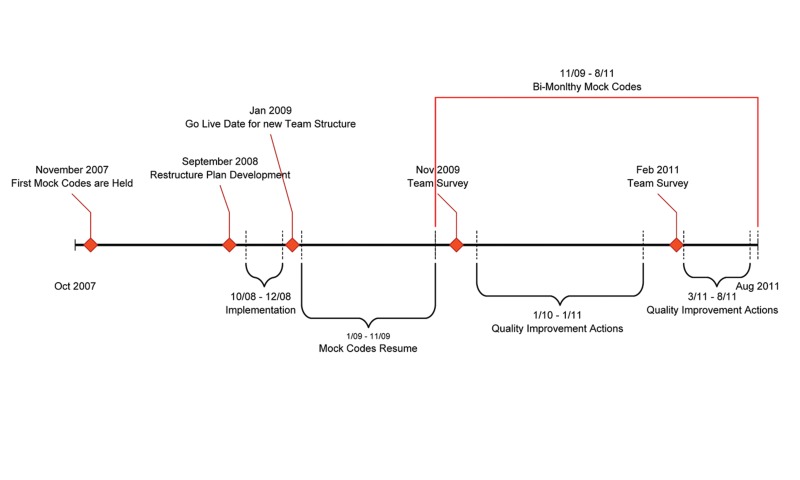

We restructured our hospital code team during a 3-month period in 2008, focusing on team roles and leadership through implementation and training (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline of pre- and post-restructure events.

Identification of Team Roles and Positions

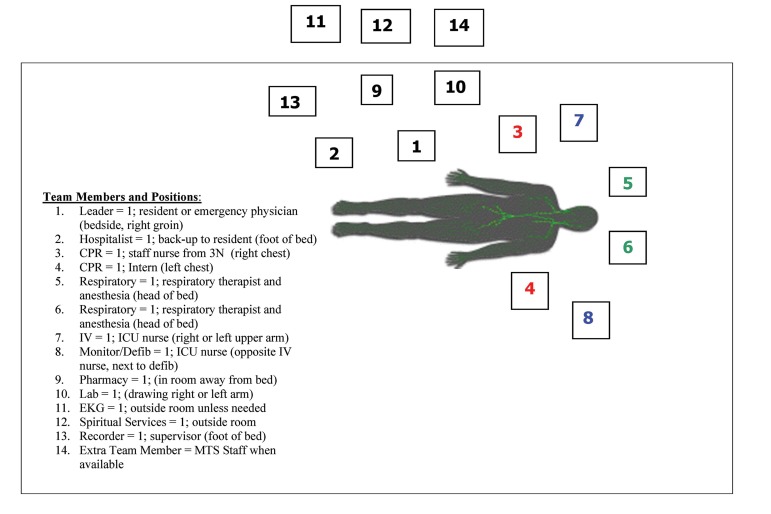

Our first task was to identify the necessary members of a code team, then assign their permanent roles and responsibilities (table 1) and their positions during a code (figure 2). For example, an ideal team leader keeps the group organized, monitors the team’s performance, emulates proper team behavior, works as a trainer and coach, and also focuses on the patient’s care. A team member must be clear about his/her role and proficient in the skills required of that role, willing to keep in practice to maintain those skills, and prepared to perform those skills at a moment’s notice.

Table 1.

List of necessary code team members, their assigned roles and responsibilities

| Position / # Needed | Role | Primary Responsibility | Secondary Responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leader / 1 | Resident or emergency physician | To lead team resuscitation; identify reversible causes. | To correct errors and assist team with duties if needed (i.e. procedures). |

| Hospitalist / 1 | Back-up to resident | Observe and assist leader. | |

| CPR / 2 | Two staff nurses from 3N and/or 6N and/or intern; located on the right and left of the patient; intern could take on the role of the left side staff nurse |

RIGHT SIDE: Evaluate need for CPR and provide uninterrupted high quality CPR, audible counting with metronome. Assure back board in place. LEFT SIDE: Need for CPR and provide uninterrupted high quality CPR, alternate compressions every 2 minutes with right CPR. Evaluate airway and breathing. |

RIGHT SIDE: If CPR not needed, assist with IV/meds as needed. |

| Airway/Respiratory / 2 | Respiratory therapist and anesthesia | Provide appropriate bag valve mask or advanced airway ventilations as needed. | Assist with patient comfort, supplemental oxygen, suctioning, and positioning. |

| IV/Meds / 1 | ICU nurse | Assess and/or place IVs, IOs immediately, accept med orders and administer medications. | Assist with patient comfort and positioning. |

| Monitor/Defib / 1 | ICU nurse | Hook up patient to defib and monitor, provide defibrillation, cardioversion as needed and at the direction of the leader. | Assist in placement of IV/IO if needed. |

| Pharmacy / 1 | -- | Fill and provide ordered medications to the IV/Med nurse promptly and correctly. | Prepare medications that may be needed ahead of time (anticipating patient needs). |

| Lab / 1 | -- | Draw lab, Code Blue panel automatically and immediately upon arrival to code. Send to lab stat and ensure results are returned to leader. | -- |

| EKG / 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Spiritual Services/ Pastor / 1 | -- | Support present family members, pray for patient, family, and code team members. | Contact family and provide updates related to information on patient condition, end of life decisions, donation, autopsy and funeral home options if indicated. |

| Recorder / 1 | Supervisor | Record all events and give information to leader as requested. | Get medical records from unit primary nurse and communicate with unit nurses, receiving unit and patients’ primary service. |

ED, emergency department; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IV, intravenous; IOs, in-put/out-put; ICU, intensive care unit, Defib, defibrillator, EKG, electrocardiography

Figure 2.

Code team members and positions relative to the patient. Similar shaded roles/positions (3 and 4, 5 and 6, 7 and 8) can be interchanged depending on the position of equipment and IV access.

After deciding what functions were critical to the code team and their position relative to the patient during a code, an absolute maximum of 13 team roles were determined useful in our institution. Staff from departments in the hospital were then chosen to fill those roles; they agreed to be part of the team in addition to their usual duties. Currently, our code team of 13 is staffed from a pool of over 200 doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, laboratory and electrocardiography (EKG) technicians, and chaplains that may be working at the time a code is called. All these people must be trained and coached regarding the new code team structure, beyond the usual ACLS training.

We then assigned to each role a red lanyard and a code pager, with the role labeled on both. The lanyard was embroidered and held a placard identifying the role and position, which is easily viewed by others during a code (figures 3a and 3b). Both the lanyard and pager are with the team member at all times, since the pager is their “alert” to a resuscitation code; no general facility-wide alert is issued. Also, the lanyard must be worn in order to be admitted into the code. These two items are physically handed off from one code team member to another from shift to shift.

Figure 3.

a) Lanyard and placard identifying the code team member’s role and position relative to the patient. b) A mock code.

Education and Training

Before launching the restructured code team, several months of education regarding the structural changes was provided to code team members through periodic in-services during large team meetings, small unit meetings, and leadership sessions. It was necessary that all code team members participate in the in-services to ensure that they were well-educated in the new team expectations. Information such as educational materials and references about team role expectations and role leadership was disseminated during meetings and via e-mail and was revised when necessary. It was also made mandatory that code team members with roles associated with ACLS must be ACLS-trained and stay current with AHA updates and associated credentials.

A commitment to simulations (mock codes) as part of the restructure and beyond was given to the team members. In addition to the mock codes, sessions with team leaders (ie, emergency physicians, residents, hospitalists, interns) were conducted to clarify and improve leadership abilities. Every potential participating member of the newly restructured code team was notified of all in-services, meetings, and mock codes, was required to participate, and was also sent all distributed information.

Mock Codes

When designing the mock codes, we did not limit these by location, time of day, or patient census considerations. We chose to hold the mock codes within the actual units in the hospital on any given day or shift, including weekends and nights, in order to recreate a realistic environment and identify issues with response time and equipment. We worked with the unit managers and staff for the day to secure the location for the event. A staff member from the unit where the mock code was to be held was selected as the primary nurse for the simulation. The primary nurse was given the scenario and asked to begin the initial assessment and call the code. Whether a mock or real code, the patient’s primary nurse remains present in the room to provide essential information to assist the code team, if needed. The mock codes were called out using the Code Blue team paging system with no indication that it was a drill. This was to ensure that the appropriate response from staff would be observed. The equipment used during the mock code consisted of a high-fidelity ACLS manikin and a training crash cart that is identical to the carts housed on the units. All other equipment utilized during the mock codes was usual equipment from the unit (defibrillator, oxygen, etc.).

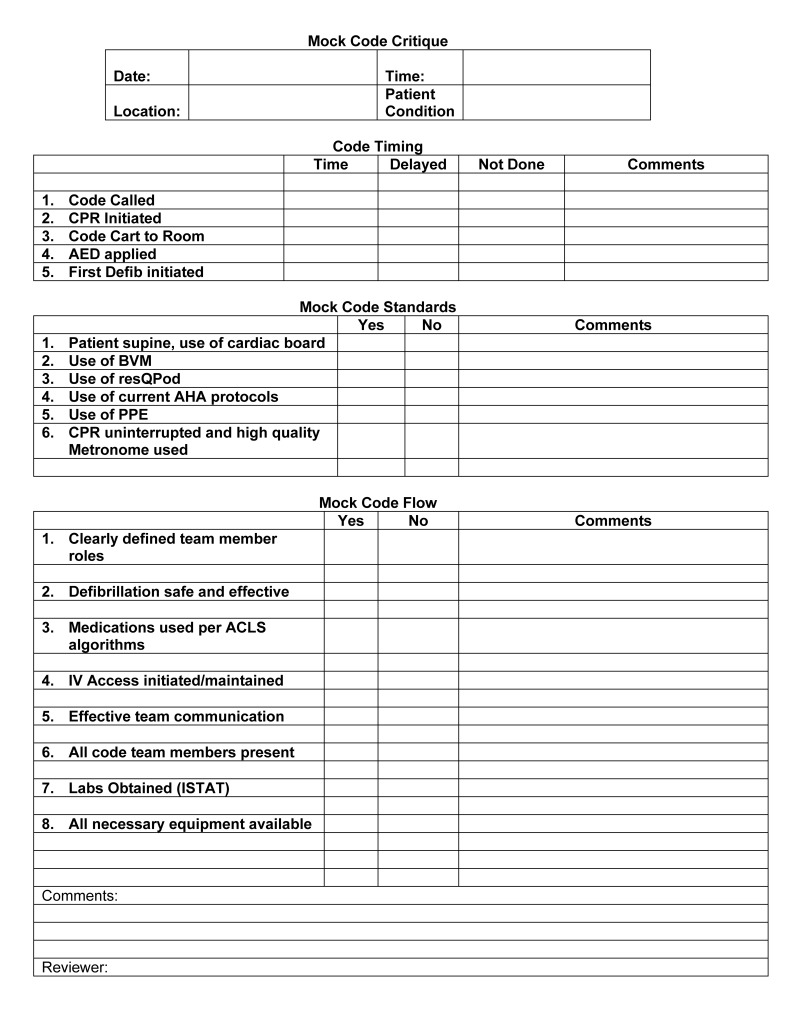

To document the mock code, a Mock Code Critique form was created (figure 4) by modifying a similar form used by a supervisor for documentation during a real code. This form is used by the expert trained observer to record the actions from the drill. The recorded information includes the time of code events (eg, code called, CPR initiated, time-to-defibrillation), the use of code standards (eg, cardiac board, AHA protocols, universal precautions), and the flow of the code (eg, team members present, team communication, necessary equipment available). The mock codes are videotaped and a copy of the video is sent to the team leader of the event for review. We have used these tapes for new team member orientation and leadership development. After the drill is complete, the observer takes 2 to 3 minutes to give the team feedback on the performance. There is also time for questions or comments from the team. The Mock Code Critique form is sent to all Code Blue team members after the simulation. Mock codes are limited to 20 minutes to ensure that optimum practice time is balanced with the need for staff to return to their usual duties.

Figure 4.

Mock code critique form.

Obstacles to code team restructure that were encountered included team member resistance to wearing the lanyards, non-adherence to assigned roles and responsibilities, and lack of participation in announced mock codes. Fortunately, these obstacles were overcome by hospital administration mandating code team meetings, mock codes, unit manager accountability, and newsletters reporting updates and outcomes to all team members. However, some resistant team members had to be dismissed from the team.

Data Collection

To determine the extent to which the code team restructure and role delineation impacted the organization of the code team process, evaluations of what occurred during both mock and actual codes, such as time to defibrillation, the use of specific equipment, and team members present were completed following each code from information entered on the mock or real code critique forms. Electronic surveys were also sent out to all team members (~200) at 11 months (year 2009) and 2 years (year 2011) after the team restructure was in place. Table 3 shows the survey questions and their possible responses that were created by a panel of code team leaders and members. Responses were collected during a one month period, tabulated, and compared. Eighty-nine (89) individuals responded to the 2009 survey, and ninety-five (95) responded in 2011.

Table 3.

Quality/Process improvement results

| Issue | Result |

|---|---|

| Delay in the arrival of IO equipment | Assigned this task to MICU staff and provided training on IO placement, IO equipment consistently arrives in a timely manner |

| Lack of familiarity of roles/Resistance to the new structure | Provided immediate follow-up and instruction. Team members are now familiar with equipment and the expectations of the roles. Mock codes are now requested by some units. |

| Staff resistance to mock codes | Immediate follow up with supervisor and staff; some staff were relieved of code team duties |

| Supervising physicians were not always responding to codes | Immediate follow up the physician and the department chair, increased compliance in response to codes. |

| Delays in lab test results | Implemented the use of ISTAT for codes |

| Team concerns over family presence during codes | With the new structure, Spiritual Services staff was able to be more engaged and assist with the family members |

| Inconsistent team debriefing after codes | Initiation of an electronic debrief form was initiated to ensure that debriefing occurs after every code |

| Performance issues during after-hours mock codes | Mock codes are now held on all shifts to address the needs of the code team during these hours. |

| Lack of equipment or the wrong equipment in some areas of the hospital or code cart | These issues have all been addressed and corrected. |

| Unit response to codes- staff unaware that a code was occurring on their unit | Implementation overhead page to the Med-Surg unit having a code, so staff could respond to help. |

| Some code activation buttons did not function | Worked with biomedical electronics to resolve the issue |

| If a patient being monitored on telemetry was in a procedure or doing physical therapy and arrested, the code would be called to the patient room rather than the patient’s location at the time of the code. | Developed a procedure to notify telemetry technicians when a patient is out of the room for any reason. |

| Inconsistent initial performance by nursing units | Mock codes enable new staff to practice ‘what if’ scenarios; coaching is done on the unit pre/post mock code; ongoing communication/education for units via Huddle messages, Clinical Compass updates, and hands-on practice. |

IO, in-put/out-put; MICU, medical intensive care unit;

Evaluation of the time-to-defibrillation was performed to determine whether the restructure of the code team, with its assigned roles and responsibilities, made an impact on this important medical intervention. Time-to-defibrillation (the time the code was called until the start of defibrillation, in minutes) was collected from code summary sheets for mock codes in 2009 and 2010 and real codes in 2008, 2009, and 2010. Codes could have occurred anywhere within the hospital (eg, cardiac catheter lab, emergency department, intensive care unit, a patient room).

The primary intent of this project was to assess and improve the quality of our hospital code team’s performance and outcomes, not to perform a research study. Therefore, we were not required to go through the Institutional Review Board for project approval per policy #1907.1.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequency and percentage, were collected into separate tables based on the questionnaire results for years 2009 and 2011. In addition, the difference in percentage for each survey question of interest was obtained by comparing the result of year 2009 to that of 2011, using the Fisher’s Exact Test with a corresponding P value (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Code Blue team survey by year

| Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2011 | ||||

| No. | (%) | No. | (%) | P valuea | |

| How beneficial are mock codes? | .7107 | ||||

| Very beneficial | 34 | (36) | 30 | (42) | |

| Not beneficial | 10 | (11) | 8 | (11) | |

| Somewhat beneficial | 51 | (54) | 34 | (47) | |

| Rate the feedback from the mock codes | .3738 | ||||

| Not beneficial | 3 | (3) | 10 | (11) | |

| 15 | (16) | 13 | (14) | ||

| Beneficial | 45 | (47) | 45 | (47) | |

| 21 | (22) | 18 | (19) | ||

| Very beneficial | 11 | (12) | 9 | (9) | |

| Do you feel more confident in your skills specific to your assigned role on the team? | .0007* | ||||

| Yes | 64 | (65) | 77 | (81) | |

| No | 14 | (14) | 15 | (16) | |

| Somewhat | 20 | (20) | 3 | (3) | |

| Is it clear where you are to be positioned during a code? | .0270* | ||||

| Yes | 95 | (97) | 84 | (88) | |

| No | 3 | (3) | 11 | (12) | |

| Are team roles better defined? | .5637 | ||||

| Yes | 93 | (95) | 88 | (93) | |

| No | 5 | (5) | 7 | (7) | |

| Has team leadership improved? | .2154 | ||||

| Yes | 47 | (48) | 52 | (60) | |

| No | 9 | (9) | 4 | (5) | |

| Somewhat | 42 | (43) | 31 | (36) | |

| Has team communication improved? | .5372 | ||||

| Yes | 52 | (88) | 48 | (92) | |

| No | 7 | (12) | 4 | (8) | |

| Are ACLS guidelines better followed? | 1.0000 | ||||

| Yes | 66 | (67) | 57 | (68) | |

| No | 2 | (2) | 1 | (1) | |

| Somewhat | 30 | (31) | 26 | (31) | |

| Has the organization of codes improved? | .9626 | ||||

| Yes | 69 | (70) | 63 | (72) | |

| No | 4 | (4) | 4 | (5) | |

| Somewhat | 25 | (26) | 21 | (24) | |

| Has there been a reduction in the amount of unneeded staff present during codes? | .8607 | ||||

| Yes | 74 | (76) | 68 | (78) | |

| No | 23 | (24) | 19 | (22) | |

| Has there been a reduction in the amount of extra talking and noise during codes? | .3564 | ||||

| Yes | 77 | (79) | 74 | (84) | |

| No | 21 | (21) | 14 | (16) | |

P-value was derived from Fisher’s Exact test;

statistically significant

ACLS, advanced cardiac life support

For the evaluation of the time-to-defibrillation, the mean, median, range, and standard deviation of each year’s mock and real codes were compared. The P values were derived from the Wilcoxon Rank Sums test due to a skewed distribution of the time-to-defibrillation. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data analyses were carried out using a commercially available statistical software package (SAS).

Results

By performing mock codes in the patient care setting versus a simulated environment, a number of issues were identified that led to quality and process improvements (table 3). Some of these issues included (1) staff on the unit being unaware that a code was occurring, therefore, an overhead page within each unit was implemented; and (2) lack of equipment and/or the wrong equipment present, so more equipment was purchased and/or specific equipment is brought to the code by the team member who needs to use it.

Respondents to the code team surveys were members of the team for varying lengths of time. Among the 2009 survey respondents, 15% had been on the team for <1 year, 30% for 1 to 2 years, 18% for 3 to 5 years, and 37% for >5 years. The distribution of the 2011 survey respondents changed to 11%, 24%, 22%, and 43%, respectively.

By comparing the survey responses from year 2011 to 2009, significant improvements were only seen in (1) confidence in skills specific to code team role (P = 0.0007) and (2) clarity in role position during a code (P = 0.027). However, other non-significant improvements were also noted, such as team leadership and a decrease in extra talking and noise during a code (table 2).

In a comparison of mock versus real codes following the code team restructure (years 2009 and 2010), there was no statistically significant difference between the time-to-defibrillation (the time the code was called until the start of defibrillation); however, time-to-defibrillation was, on average, shorter for real codes (table 4a). The time-to-defibrillation of real codes for the years following the code team restructure were compared to data collected for 2008, before the team restructure. There was no statistically significant difference; however, the average time-to-defibrillation did become shorter each year (table 4b). The same outcome was observed for mock codes that took place after the team restructure (table 4c).

Table 4.

| A. Comparison outcomes of mock codes versus real codes time-to-defibrillation. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Defibrillation time (minutes) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Year | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range | P-valuea |

| Year 2009 | .6619 | ||||

| Mock | 6 | 3.83 | 4.02 | 0.00–10.00 | |

| Real | 26 | 2.73 | 2.57 | 0.00–9.00 | |

| Year 2010 | .1090 | ||||

| Mock | 17 | 2.65 | 1.90 | 0.00–5.00 | |

| Real | 13 | 1.46 | 1.76 | 0.00–5.00 | |

| B. Comparison outcomes of real codes time-to-defibrillation | |||||

|

| |||||

| 2008b | 21 | 3.71 | 3.59 | 0.00–13.00 | |

| 2009 | 26 | 2.73 | 2.57 | 0.00–9.00 | .4650 |

| 2010 | 13 | 1.46 | 1.76 | 0.00–5.00 | .0659 |

| C. Comparison outcomes of mock codes time-to-defibrillation | |||||

|

| |||||

| 2009 | 6 | 3.83 | 4.02 | 0.00–10.00 | |

| 2010 | 17 | 2.65 | 1.90 | 0.00–5.00 | .7506 |

P-value was derived from Wilcoxon Rank Sums test.

Comparison group.

Discussion

Code Team Improvements

The improvements in the survey respondents’ perceptions of their roles on the code team, and therefore, the overall team function, could be due to several things. One could be the change in distribution in the length of time people have been members of the code team. Members with >5 years on the team increased from 37% to 43% from 2009 to 2011, possibly from less turnover of team members due to increased satisfaction while being on the restructured code team. Also, more members with more experience leads to better team dynamics and confidence in members’ roles. Being comfortable with the team restructure and their assigned roles can further be due to wearing the role identifying lanyard and responsibilities placard, continued education, mock codes, and evaluation, and the structure being in place for 2 years. For example, the code team members thought the lanyards clearly identified each person’s role and position during the code response, reducing confusion and enhancing teamwork.

Ultimately, the results of the surveys show that the changes implemented in the code team restructure are thought to be positive, with a range from at least somewhat or very beneficial in most areas where changes have been made, and those benefits have persisted over the 2 years following the restructure. Additionally, an unexpected benefit from these improvements was increased code team satisfaction, morale, and camaraderie, as demonstrated by the subjective survey results and anecdotal evidence.

Code team training programs that incorporate simulations have been recommended by the Institute of Medicine since 1999,4,14 and in 2013, the AHA’s consensus statement for improving cardiac resuscitation outcomes both inside and outside the hospital reinforced this recommendation.15 Implementation of mock codes offers team members, who are not routinely exposed to critical events with hospital patients requiring the code team, the opportunity to participate in repetitive hands-on practice in clinical settings.8 Assignment of clear team roles so members know their responsibilities and placement during a code, along with mock codes and continuing education, allow team members to become confident in their roles. This also leads to confidence in their fellow team members. The team leader can then focus on the causes of a cardiac arrest and other aspects of leading the code, rather than having to ensure that the basics of a code response are being done properly. Additionally, there is overall team value in consistent, skilled, physician leadership.11

Proper verbal communication and information sharing are essential for teamwork in high intensity situations like code team responses.7,8,16,17 A team leader should calmly, clearly, and directly give an assignment, then confirm that the message was heard. Team members should confirm that they heard the assignment, then inform the leader when the task is completed. However, there can be several factors associated with communication failures, such as (1) physicians, nurses, and other medical professionals being trained to communicate differently; (2) health care system hierarchies that frequently inhibit people from speaking up about issues and concerns; and, (3) a lack of standardized communication and procedures in different areas of health care.6 Communication failures can contribute to errors occurring during a code team response; therefore, simulation training and continued education leads to proper communication and information sharing among team members, which ultimately leads to effective teamwork. In addition, creating a new code team and only allowing team members who are wearing their identifying lanyards into the room decreases the number of people present, which leads to less confusion, noise, and unnecessary talk in the room.

All these factors, improved through code team restructure and continued training, lead to enhanced understanding of each member’s role and its responsibilities, improved knowledge of the role, increased level of skills, proper communication, effective teamwork, confidence, comfort, and preparedness, ultimately leading to improved patient safety and care.

Changes in Defibrillation Times

Even though there was no statistically significant difference in the time-to-defibrillation (the time the code was called until the start of defibrillation), there was a definite trend toward shorter time-to-defibrillation during codes as the years progress. This is an important positive outcome of the code team restructure that ultimately impacts on patient survival. Time-to-defibrillation of mock codes was compared to real codes to determine whether the team may have performed differently when dealing with a manikin versus an actual person. The urgency of saving a real person may play a role in these shorter code times.

One possible reason for there being no statistically significant difference in any of the time-to-defibrillation comparisons is that the numbers of codes in each group analyzed was too small. For our QI project, a real code consisted of any code occurring within the hospital with a presenting initial arrest rhythm of ventricular fibrillation (VF), since this is the only type of initial presenting rhythm that needed defibrillation. In-hospital VF codes accounted for 14% of all codes (21/154) in 2008, 16% (26/163) in 2009, and 7% (13/189) in 2010. These rates of in-hospital VF codes are comparable to other rates (16%–22%) found in the literature.18,19

Project Limitations and Future Directions

A limitation of our project was the collection of minimal data. We only collected the time-to-defibrillation of each code and the results of the two electronic surveys sent out after the implementation of the restructured code team. At the least, another survey should have been sent out to the code team members before the team restructure to establish “baseline” results. However, this QI project had not been approached as a research study.

For potential future QI and research projects, the collection of more information and data, including patient survival outcomes, would be extremely helpful. Also, the number of mock codes held per year could easily be increased to enable more powerful statistical analyses; however, there would be no control over the number of real codes that occur. Fortunately, low numbers of real codes are a positive outcome for patients, doctors, and hospital administration. To increase the number of real codes for statistical analyses, a future study could utilize data from multiple hospitals who have implemented this restructured code team.

Conclusion

The keys to a better code team are organization, clearly identified roles, and frequent team practice in the form of mock codes. These result in a code team with improved confidence in their role specific skills, clarity in their role positions, and team leadership, as well as a decrease in the time-to-defibrillation. These outcomes also support the continued use of ongoing simulation training to further improve team performance, maintain member confidence, and assure quality patient care. Therefore, a restructured code team is beneficial to many, including the team members, the medical institution, and patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication for assistance with this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Support: Support for this project was provided by Marshfield Clinic and Ministry Saint Joseph’s Hospital. This project was performed at Ministry Saint Joseph’s Hospital, Marshfield, Wisconsin.

References

- 1.Falker A. Decreasing code chaos: Identifying roles, maximizing results. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses poster presentation 2007; CS40 Available at: http://classic.aacn.org/AACN/NTIPoster.nsf/vwdoc/2007CSAFalker1 Accessed on September 30, 2011.

- 2.Andersen PO, Jensen MK, Lippert A, Østergaard D, Klausen TW. Development of a formative assessment tool for measurement of performance in multi-professional resuscitation teams. Resuscitation 2010;81:703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villamaria FJ, Pliego JF, Webbe-Janek H, Coker N, Rajab MH, Sibbitt S, Ogden PE, Musick K, Browning JL, Hays-Grudo J. Using simulation to orient code blue teams to a new hospital facility. Simul Healthc 2008;3:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill CR, Dickter L, Van Daalen EM. A matter of life and death: The implementation of a Mock Code Blue program in acute care. Medsurg Nurs 2010;19:300–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuttle RP, Cohen MH, Augustine AJ, et al. Utilizing simulation technology for competency skills assessment and a comparison of traditional methods of training to simulation-based training. Resp Care 2007;52:263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarwani N, Tappouni R, Flemming D. Use of a simulation laboratory to train radiology residents in the management of acute radiologic emergencies. Am J Radiology 2012;199: 244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunziker S, Johansson AC, Tschan F, Semmer NK, Rock L, Howell MD, Marsch S. Teamwork and leadership in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:2381–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price JW, Applegarth O, Vu M, Price JR. Code blue emergencies: a team task analysis and educational initiative. Canadian Medical Education Journal 2012;3:e4–e20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delac K, Blazier D, Daniel L, N-Wilfong D. Five alive: using mock code simulation to improve responder performance during the first 5 minutes of a code. Crit Care Nurs Q 2013;36:244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeVita MA, Schaefer J, Lutz J, Wang H, Dongilli T. Improving medical emergency team (MET) performance using a novel curriculum and a computerized human patient simulator. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:326–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qureshi SA, Ahern T, O’Shea R, Hatch L, Henderson SO. A standardized code blue team eliminates variable survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest. J Emergency Med 2012;42:74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sodhi K, Singla MK, Shrivastava A. Impact of advanced cardiac life support training program on the outcome of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Crit Care Med 2011;15(4):209–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wayne DB, Didwania A, Feinglass J, Fudala MJ, Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC. Simulation-based education improves quality of care during cardiac arrest team responses at an academic teaching hospital: a case-control study. Chest 2008;133: 56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corrigan J, Kohn LT, Donaldson MS, editors. To err is human: building a better health system. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meaney P, Bobrow BJ, Mancini ME, Christenson J, de Caen AR, Bhanji F, Abella BS, Kleinman ME, Edelson DP, Berg RA, Aufderheide TP, Menon V, Leary MCPR Quality Summit Investigators, the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee, and the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: improving cardiac resuscitation outcomes both inside and outside the hospital: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013;128:417–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webbe-Janek H, Lenzmeier CR, Ogden PE, Lambden MP, Sanford P, Herrick J, Song J, Pliego JF, Colbert CY. Nurses’ perceptions of simulation-based interprofessional training program for rapid response and code blue events. J Nurs Care Qual 2012;27:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergs EA, Rutten FL, Tadros T, Krijnen P, Schipper IB. Communication during trauma resuscitation: do we know what is happening? Injury 2005;36:905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niemann JT, Stratton SJ. The Utstein template and the effect of in-hospital decisions: the impact of do-not-attempt resuscitation status on survival to discharge statistics. Resuscitation 2001;51:233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, Larkin GL, Nadkarni V, Mancini ME, Berg RA, Nichol G, Lane-Trultt T. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation 2003;58: 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]