ABSTRACT

Increasing numbers of cancer cases generate a great urge for new treatment options. Applying bacteria like Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium for cancer therapy represents an intensively explored option. These bacteria have been shown not only to colonize solid tumors but also to exhibit an intrinsic antitumor effect. In addition, they could serve as tumor-targeting vectors for therapeutic molecules. However, the pathogenic S. Typhimurium strains used for tumor therapy need to be attenuated for safe application. Here, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) deletion mutants (ΔrfaL, ΔrfaG, ΔrfaH, ΔrfaD, ΔrfaP, and ΔmsbB mutants) of Salmonella were investigated for efficiency in tumor therapy. Of such variants, the ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG deep rough mutants exhibited the best tumor specificity and lowest pathogenicity. However, the intrinsic antitumor effect was found to be weak. To overcome this limitation, conditional attenuation was tested by complementing the mutants with an inducible arabinose promoter. The chromosomal integration of the respective LPS biosynthesis genes into the araBAD locus exhibited the best balance of attenuation and therapeutic benefit. Thus, the present study establishes a basis for the development of an applicably cancer therapeutic bacterium.

IMPORTANCE

Cancer has become the second most frequent cause of death in industrialized countries. This and the drawbacks of routine therapies generate an urgent need for novel treatment options. Applying appropriately modified S. Typhimurium for therapy represents the major challenge of bacterium-mediated tumor therapy. In the present study, we demonstrated that Salmonella bacteria conditionally modified in their LPS phenotype exhibit a safe tumor-targeting phenotype. Moreover, they could represent a suitable vehicle to shuttle therapeutic compounds directly into cancerous tissue without harming the host.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer has become the second most frequent cause of death in industrialized countries, with a rising incidence. This generates a great urge to develop new strategies for prevention and treatment. Numerous studies have shown that the immune system is able to fight a cancerous disease. Nevertheless, only a few immune therapeutics are available in the clinic to date (1–3). Remarkably, the first successfully applied cancer immunotherapy dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. In his pioneering work, William Coley developed a therapy by using a mixture of heat-inactivated bacteria known as Coley’s toxin. Tumor regression was observed in a majority of the patients treated. Some patients even cleared the tumor and stayed disease free (4). A recent review of his records demonstrated that the length of treatment and the induction of fever were indicative of successful therapy (5, 6). Although the exact molecular mechanisms are still not well understood, different bacterial pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs; e.g., lipopolysaccharide [LPS], flagellin, CpG) most likely trigger an innate proinflammatory antitumor response.

Strong efforts have been mounted in recent years to revive the idea of bacterium-mediated tumor therapy. Many bacteria have been shown to target experimental solid tumors with high specificity and exert therapeutic effects on tumors. In this context, safety strains have been established by in vitro or in vivo selection (7). In addition, clinical trials have been initiated, although their success was ambiguous (8–10).

Besides the intrinsic antitumor effect, a second important aspect exists, namely, to use such bacteria as shuttle vectors for therapeutic molecules. Recombinant bacterial strains could be tailored to specifically target tumor tissue and produce therapeutic agents directly inside neoplastic tissue. Accordingly, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Clostridium species have been intensively explored (9, 11, 12). Combining intrinsic immune-mediated and extrinsic vector-based bacterial therapies could be a novel and innovative treatment strategy for cancer patients in the future.

A problem that remains is that a suitable strain should exhibit an optimal balance between immune stimulation and being safe for human patients. Wild-type (WT) bacteria would cause severe septicemia with a fatal outcome. Too strongly attenuated bacteria will not stimulate the immune system sufficiently or might not reach the tumor at all. The latter might be the explanation for the disappointing outcome of the first clinical trial in which a safe variant of S. Typhimurium with a modified lipid A moiety of the LPS was used (10). This modification strongly reduced the immunostimulatory capacity of the bacteria, as judged by the induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). However, this cytokine might be essential for efficient colonization of the tumor (13).

In the present work, an alternative attenuation strategy was used. The LPS structure was modified by deleting genes involved in its synthesis. LPS is known to be essential for the integrity of bacteria in the host (14–16). On the other hand, LPS is highly immunostimulatory. Lipid A, as the innermost structural part of LPS, is an important PAMP (17). Most likely, it is required for optimal invasion of solid tumors by bacteria.

To accommodate the two opposing demands, we first tested mutants with a modified LPS structure for their performance in vitro and in tumor-bearing mice. Only variants in which the LPS core structure was compromised showed acceptable safety profiles. However, their therapeutic potential was dramatically reduced. To reconcile these features with the required immunostimulatory and therapeutic potency, we complemented the LPS mutants with a construct that allowed inducible expression of the complementing gene. This recovered much of the therapeutic capacity without increasing the risk of septicemia problems.

RESULTS

LPS mutants and their in vitro characterization.

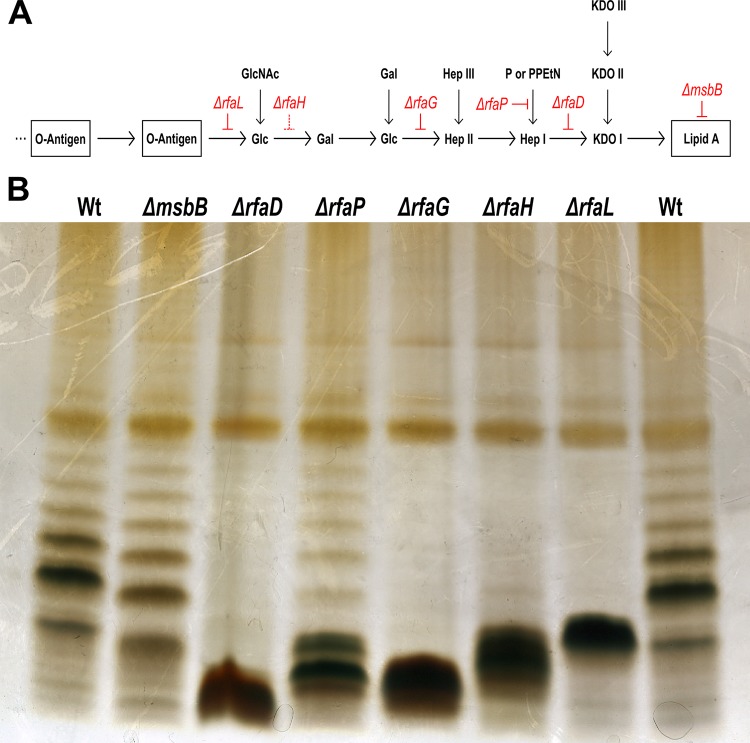

LPS variants of S. Typhimurium strain ATCC 14028 were constructed by deleting the genes rfaL, rfaG, rfaH, rfaD, rfaP, and msbB as schematically shown in Fig. 1A. To confirm the mutations, SDS-PAGE was used to visualize the modified LPS (Fig. 1B). As expected, the ΔrfaL mutant exhibited a lack of O antigen, as indicated by loss of the repetitive bands. The shorter length of the main band of the ΔrfaH mutant is consistent with the loss of the additional sugars, similar to the ΔrfaG mutant with a further reduced outer core. The size of the major band of the ΔrfaD mutant indicates absence of the inner core. The slight shift of bands of the ΔmsbB variant is due to a penta-acylated lipid A structure. In the ΔrfaP variant, the normal O-antigen structure is present. However, the bands observed were weaker and the strong low-molecular-weight band indicates that a portion of the LPS is truncated at the core.

FIG 1 .

LPS phenotypes of Salmonella mutants. (A) Schematic representation of LPS structure. The genes encoding the enzymes for particular steps in the synthesis or modification of LPS that were deleted in the present work are red. (B) Visualization of the LPSs of various Salmonella mutant strains by 16.5% Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE and silver staining. The ΔrfaL, ΔrfaH, ΔrfaG, and ΔrfaD LPS mutants lack the O antigens (repetitive bands). The different electrophoretic mobility of the LPS of the remaining variants confirms the expected structure. The ΔmsbB mutant exhibits a pattern comparable to that of the WT. However, the bands migrate slightly faster because of the penta-acylated lipid A structure.

These mutants were further characterized to test their in vivo applicability. Growth in LB or minimal medium showed no defects (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Smaller colonies of the ΔrfaD mutant were observed on LB plates, indicating a slight growth defect that is observable only after prolonged incubation.

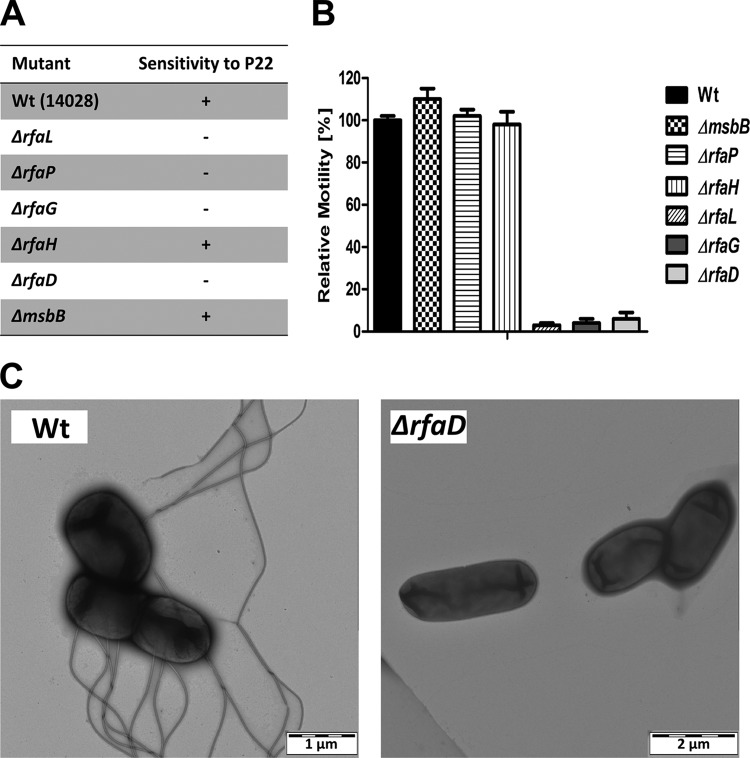

As expected, the rfaD, rfaG, and rfaL deletion mutants were resistant to P22 (Fig. 2A). Similarly, no motility was detected in the ΔrfaG, ΔrfaD, and ΔrfaL mutants within 4 h (Fig. 2B). However, after 24 h, limited motility was observed in the ΔrfaG and ΔrfaD mutants. Electron microscopy revealed that the majority of the rfaD-deficient mutants did not express flagella, whereas a few bacteria still exhibited a reduced number of flagella in comparison to that of the WT (Fig. 2C).

FIG 2 .

Phenotypic characterization of LPS mutants. (A) Challenge with bacteriophages P22. Strains that lack the O antigen are resistant to bacteriophage P22 (−), while WT salmonellae and variants with residual O antigen are sensitive (+). (B) Assessment of motility in semisolid (0.3%, wt/vol) agar. The ΔrfaL, ΔrfaG, and ΔrfaD core mutants remain sessile for at least 4 h (C) Electron microscopy of negatively stained WT Salmonella strain ATCC 14028 and the ΔrfaD variant. The mean and range are displayed. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five biological replicates per group.

In vivo colonization profile and virulence.

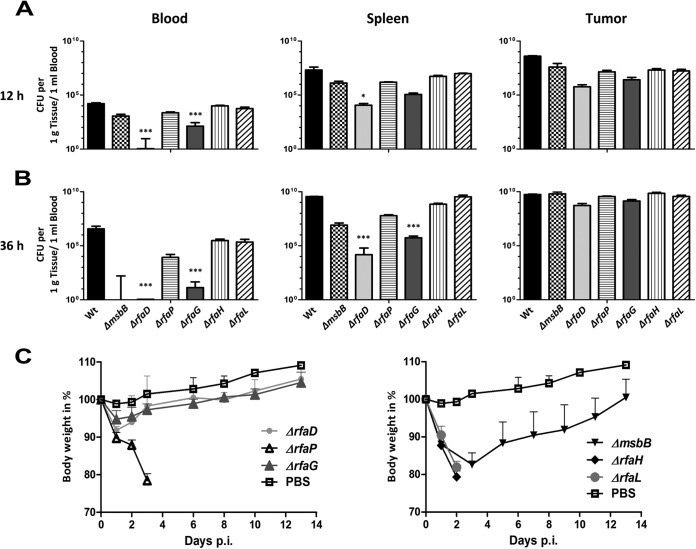

CT26 tumor-bearing mice were infected with the LPS variant strains to evaluate their potency for cancer therapy. Blood, spleen, and tumor homogenates were plated at 12 and 36 h postinfection (hpi) (Fig. 3). The colonization profile of the ΔrfaG and ΔrfaD LPS core mutants differed significantly from that of the WT and the other mutants. Apparently, these bacteria exhibit strongly reduced fitness in vivo. The bacterial burden was strongly decreased in the spleen and almost completely cleared from the blood within 12 h (Fig. 3A and B). The ΔrfaP and ΔmsbB mutants displayed an intermediate phenotype. Although the ΔmsbB mutant was cleared from the blood, the splenic burden remained relatively high in comparison to that of the ΔrfaD or ΔrfaG mutant. The ΔrfaH and ΔrfaL mutants behaved similar to an infection with the WT, consistent with their slight alterations of the LPS structure distal to the core membrane structures. Bacteria of all of the strains eventually colonized the tumors to the same degree (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3 .

In vivo characterization of LPS variants in CT26-bearing BALB/c mice. Mice were infected i.v. with 5 × 106 CFU. (A and B) Blood, spleen, and tumor bacterial burdens were determined by plating serial dilutions of tissue homogenates. (A) CFU counts in different homogenates at 12 hpi. (B) CFU counts in different homogenates at 36 hpi. Much lower numbers of ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG LPS core mutant bacteria than WT bacteria were observed in the blood and spleen. (C) Body weight measurement as an indicator of general health status after infection of CT26-bearing mice with different LPS variants. Again, the ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG mutants are highly attenuated while the ΔrfaH, ΔrfaG, and ΔrfaL mutants are lethal within 3 days. The median and range are displayed. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five mice per group. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

The body weights of infected mice were monitored to evaluate the impact of the mutants on the general health of tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 3C). The ΔmsbB, ΔrfaD, and ΔrfaG mutants appeared to be appropriately attenuated. The mice recovered quickly after an initial weight loss, although the impact of the ΔmsbB mutant was much more severe. In contrast, the ΔrfaH, ΔrfaL, and ΔrfaP mutants were highly virulent and the mice succumbed to the infection. For that reason, the ΔrfaG and ΔrfaD mutants were chosen as potential candidates for further experiments. These two strains exhibit the highest tumor-to-spleen ratio of 10³:1 to 104:1 and the lowest health burden for the mice. To verify these findings, the ΔrfaG mutant was also tested in RenCa and F1A11 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The same tumor-to-spleen ratio was found. Thus, a tumor-specific effect can be excluded.

Sensitivity of LPS mutants to innate defense mechanisms.

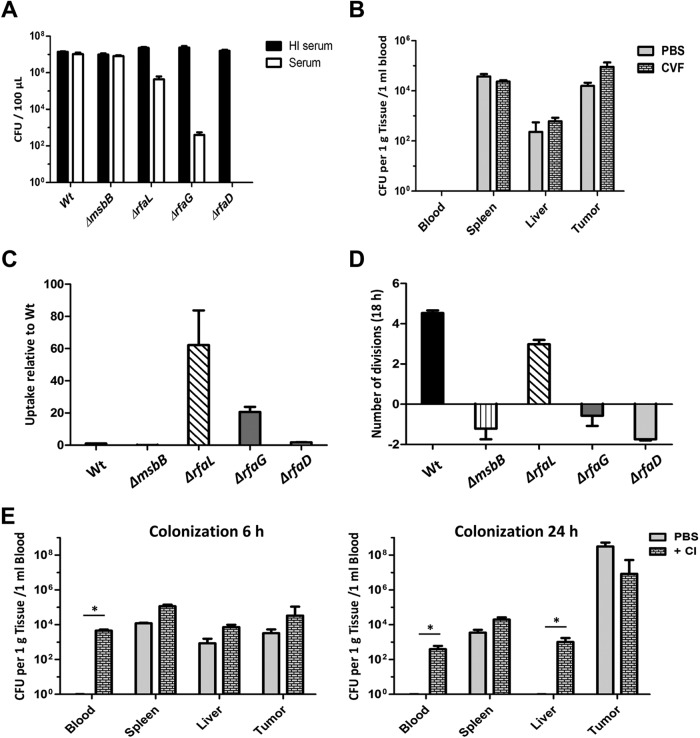

The attenuating effect of these mutations is already apparent after a short time (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Hence, bacteria of such strains might be more sensitive to effector mechanisms of the innate immune system. Treatment with human serum revealed that WT salmonellae were not affected by complement while complement-induced lysis of the LPS mutants was stronger the more the LPS structure was shortened (Fig. 4A). Virtually all of the ΔrfaD mutant bacteria were lysed within 30 min. The modification of lipid A by the msbB mutation did not influence the bacterial behavior toward these innate effector molecules (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4 .

Sensitivities of selected LPS variants to complement and phagocytes. (A) In vitro sensitivities of different LPS variants to complement. A total of 2 × 107 bacteria were treated with either untreated or heat-inactivated (HI) human serum for 30 min at 37°C. The lysis effect was determined by plating and correlates with the LPS structure. (B) Influence of in vivo depletion of the complement system on the colonization profile of the ΔrfaD mutant. Mice were treated with 5 IU of CVF at 12 h before infection. Bacterial burdens were assessed by plating tissue homogenates. (C) Sensitivities of selected LPS variants to phagocytes. J774 cells were infected at an MOI of 1, and phagocytic uptake was determined relative to that of the WT after 1 h. The uptake of the ΔrfaG and ΔrfaL mutants is significantly increased, whereas that of the ΔrfaD mutant remains at WT levels. The ΔmsbB mutant was almost not taken up by J774 cells. (D) Intracellular replication of LPS mutants within J774 cells. Cells were allowed to phagocytize the bacteria as in panel C. Infected cells were incubated for 18 h, and the remaining bacterial burden was determined by plating. Except for the ΔrfaL mutant, the LPS mutants cannot survive in J774 cells. (E) To determine the importance of macrophages for the in vivo survival of LPS variants, mice were treated with clodronate (Cl) or left untreated and then infected with 5 × 106 ΔrfaD mutant bacteria i.v. The number of bacteria was determined by plating of serial dilutions of tissue homogenates. The median and range are displayed. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five replicates per group. *, P < 0.05.

This was further evaluated by depletion of complement from tumor-bearing mice with cobra venom factor (CVF). Quantitation of the bacteria in organs, blood, and tumors revealed that the reduced fitness of the ΔrfaD mutant might not be due to the complement system. Colonization was very similar to that of untreated mice (Fig. 4B). However, this experiment might underestimate the role of complement in vivo since complete depletion was not achieved (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

Since the complement system might have only a minor impact on the inner-core LPS mutants in vivo, the role of macrophages was investigated. Resistance to uptake by J774 macrophages was analyzed. The majority of the ΔrfaL mutant bacteria were phagocytosed within 1 h (Fig. 4C). The ΔrfaG mutant was also readily taken up by these macrophages, while uptake of the ΔrfaD mutant was low, similar to that of WT salmonellae. Importantly, the numbers of ΔrfaD, ΔrfaG, and ΔmsbB mutant bacteria within the macrophages were reduced significantly at 18 hpi. This indicates that such mutants could not resist the effector mechanisms of the phagocytic cells. In contrast, the ΔrfaL mutant, lacking only the O antigen, was still able to replicate in macrophages although at a lower rate (Fig. 4D). The experiment was corroborated with bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) from BALB/c mice with similar results (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

To analyze the activity of macrophages against such LPS variant bacteria in vivo, macrophages were depleted with clodronate before infection with the ΔrfaD mutant (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Quantitation of the numbers of CFU in organs, blood, and tumors demonstrated that bacteria were still present in the blood and liver at 24 hpi while they were absent from samples from untreated mice (Fig. 4E). Thus, mainly macrophages appeared to be responsible for the decreased fitness of LPS mutant strains, in particular of the ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG mutants. Attenuation of the LPS variant strains is apparently achieved by increasing bacterial sensitivity to innate immune effector mechanisms.

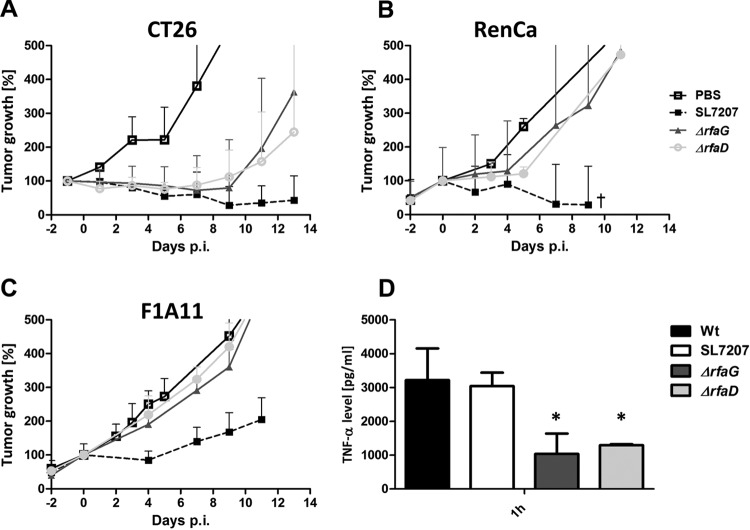

Intrinsic antitumor effect of the ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG mutants.

While attenuation of the rfaD or rfaG mutant was satisfactorily achieved, therapeutic efficacy needed to be established. As shown in Fig. 5, the volumes of the CT26 tumors of mice infected with the Salmonella ΔrfaD or ΔrfaG mutant regressed and some tumors were even cleared (Fig. 5A). In contrast, only growth retardation of RenCa tumors was observed (Fig. 5B). Almost no effect on F1A11 sarcomas was observed (Fig. 5C). In general, the antitumor effect was weaker than that of strain SL7207, which was tested in previous studies (18, 19).

FIG 5 .

Tumor development after infection with Salmonella LPS variants. CT26 (A), RenCa (B), and F1A11 (C) tumor-bearing mice were infected i.v. with 5 × 106 bacteria. Tumor volumes were measured with a caliper. PBS served as a negative control, and SL7207 served as a positive control for comparison. (D) TNF-α levels in sera measured by ELISA at 1.5 hpi with selected LPS variants. The ΔrfaG and ΔrfaD mutants induced a lower response than WT salmonellae. The median and range are displayed. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five replicates per group. The symbol † indicates that two out of five mice succumbed to the infection. *, P < 0.05.

Earlier studies showed the importance of a strong initial TNF-α response, which is required for successful tumor colonization. Thus, the TNF-α induction was determined in the blood of infected mice shortly after bacterial application. In comparison to those achieved with the WT, the levels of TNF-α were greatly reduced when CT26-bearing mice were infected with the ΔrfaD or ΔrfaG mutant (Fig. 5D). This might explain the weaker antitumor response.

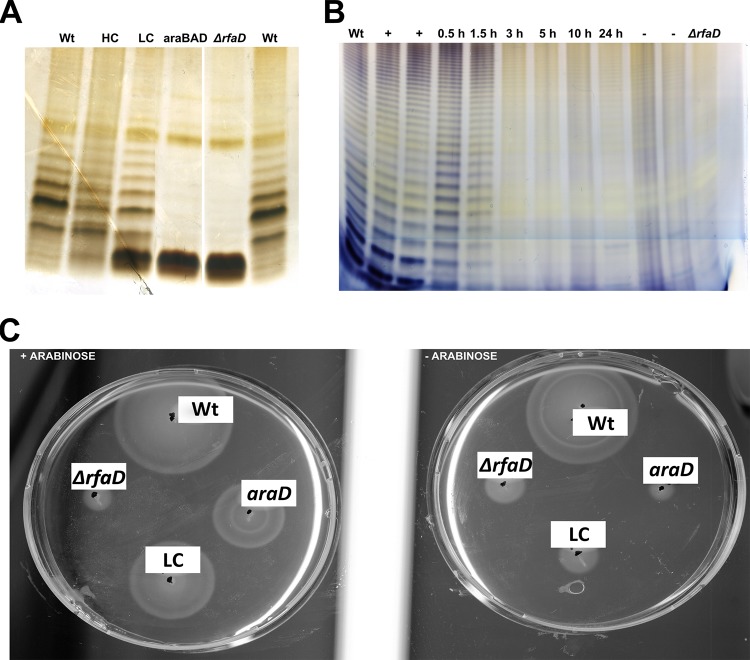

Improvement of the ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG mutant strains.

The ΔrfaD or ΔrfaG mutant strain needed to be improved. Since the specificity of tumor colonization of the ΔrfaD variant was the highest, we concentrated on this variant. A delayed-attenuation system was designed for these bacteria. The strategy was to conditionally complement the LPS mutation with an arabinose-inducible construct. Arabinose should be provided in culture for the mutants to exhibit a WT phenotype, whereas in the host, the bacteria should become attenuated since they are no longer able to express the complemented gene. Various possibilities were tested, ranging from high- and low-copy-number plasmids to chromosomally integrated systems. Figure 6A shows silver-stained SDS-PAGE of the noninduced conditionally complemented variants. Most such systems appeared to be leaky. Only chromosomal integration replacing the araBAD genes with the PBAD-controlled rfaD construct appeared to fulfill the requirements (Fig. 6A). The LPS structure in its noninduced state appeared to be like that of the original ΔrfaD mutant.

FIG 6 .

Phenotypes of conditionally complemented LPS mutants. (A) Complementation was carried out by placing the arabinose-inducible construct in high-copy (HC) and low-copy (LC) plasmids or by chromosomal integration (araBAD). Silver-stained SDS-PAGE of bacterial lysates in a noninduced state is shown. The chromosomal integration ΔaraBAD::PBAD rfaD was chosen for further studies since no O antigen was produced. (B) Recovery of the WT LPS phenotype by the ΔaraBAD::PBAD rfaD variant treated with arabinose (+) and kinetics of loss of WT LPS structure upon removal of arabinose. An aliquot of an induced culture was subcultured in arabinose-free medium. The LPS phenotype was assayed at the times indicated. The deletion phenotype was first detected 3 h after the removal of arabinose. (C) Assay of motility on swimming agar plates. Aliquots of the arabinose-induced or untreated ΔrfaD variant were used to inoculate swimming plates containing 0.3% agarose and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Points of inoculation are indicated by black dots. araD stands for ΔaraBAD::PBAD rfaD. LC indicates that the variant was conditionally complemented with a construct on a low-copy-number plasmid. When the conditionally complementing construct was chromosomally integrated (araD), motility was similar to that seen upon a clean deletion (the ΔrfaD mutant) in the absence of the inducer arabinose.

To test whether chromosomal complementation of the PBAD rfaD mutant could restore the WT phenotype to the ΔrfaD mutant, arabinose was added to the cultures. Indeed, the LPS pattern on SDS-PAGE resembled the WT LPS pattern (Fig. 6B). Thus, the chromosomal PBAD rfaD construct was able to conditionally complement the LPS mutation. We next removed arabinose from the culture to test how long complemented LPS could be detected. The first reduction of band intensity was seen after 1.5 h. By 3 h, complementation had ceased and the LPS pattern resembled that of the clean ΔrfaD mutant (Fig. 6B).

These findings were corroborated by testing the motility of such conditionally complemented mutants. Motility was strongly reduced in noninduced variants. Leakiness of the constructs was obviously not as apparent as in silver-stained SDS-PAGE. Induction of complementation by the addition of arabinose to the motility plates resulted in a spread of bacteria that was comparable to that of the WT (Fig. 6C). In accordance, the resistance to macrophages and the complement system was also restored to WT levels upon the addition of arabinose to the complemented variants (see Fig. S7 and S8 in the supplemental material).

The full WT LPS structure was detected for all rfaG mutant constructs, even in the absence of the inducer arabinose. Such noninduced conditionally complemented variants were lethal for mice. This indicated that conditionally complemented variants of the ΔrfaG mutant were too leaky to be useful (data not shown).

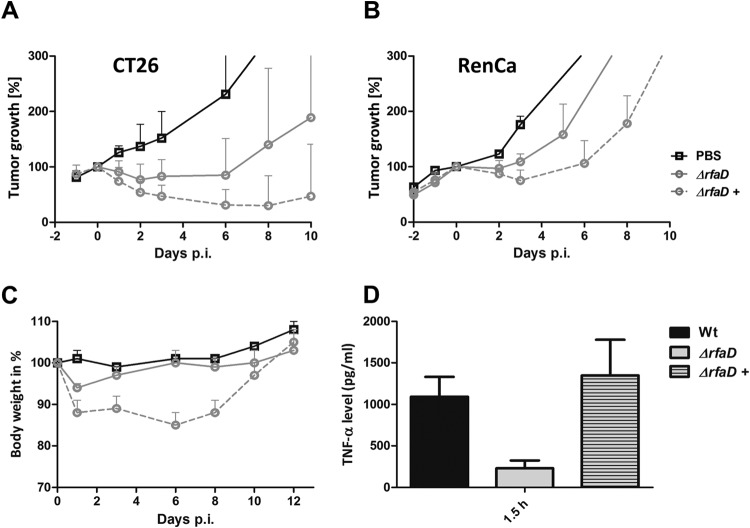

Therapeutic potential of improved strains.

The performance of the chromosomally and arabinose-regulated rfaD mutant was then tested in the mouse tumor models. Bacteria were induced, i.e., complemented in culture and then injected into tumor-bearing mice. Compared to that of the noncomplemented rfaD mutant, the antitumor response of the conditionally complemented mutant was clearly enhanced for CT26 tumors (Fig. 7A). Similar observations were made in the RenCa model (Fig. 7B). No improved effect on F1A11 was observed (data not shown). F1A11 has been shown previously to be very resistant to this type of therapy (data not shown).

FIG 7 .

Tumor development upon infection with the arabinose-induced conditionally complemented Salmonella ΔrfaD variant. CT26 (A) and RenCa (B) tumor-bearing mice were infected i.v. with 5 × 106 bacteria. Tumor volumes were measured with a caliper. PBS served as a negative control, and SL7207 served as a positive control for comparison. (C) Body weight as an indicator of the general health status of infected mice. Induced (+) ΔaraBAD::PBAD rfaD bacteria exhibited greater virulence but also a stronger antitumor effect. (D) TNF-α levels in sera measured by ELISA at 1.5 hpi. Upon induction with arabinose (+), TNF-α was restored to WT levels. The mean and range are displayed. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five replicates per group.

The conditional activation of the complementing gene with arabinose correlated with a slight increase in the pathogenicity of the strain (Fig. 7C). General health, as judged by weight loss, was affected more than with the noncomplemented ΔrfaD mutant. However, the effect was less pronounced than with the ΔmsbB mutant, which had been shown to be safe in human patients (10).

As expected, stronger induction of TNF-α was observed in the blood after application of the conditionally complemented ΔrfaD mutant (Fig. 7D). Taken together, these complementation experiments demonstrated that a conditional-attenuation approach might be a suitable way to circumvent the problem of early clearance of attenuated bacteria by the immune system. Importantly, this approach achieved stronger antitumor responses and more efficient tumor colonization while at the same time rendering the bacteria safe.

DISCUSSION

LPS originating from Gram-negative bacteria like salmonellae is one of the major inducers of sepsis. Therefore, modification of LPS represents an attractive way to attenuate salmonellae for use as a systemically applied vector. However, LPS, as the outermost structure of the cell envelope, is also an important barrier and defense mechanism for bacteria that is essential for survival in the host and efficient tumor colonization. Salmonella safety strain VNP20009, which is modified in lipid A, failed in efficacy of tumor colonization and antitumor activity in human patients during previous clinical trials (10). This highlights the importance of the delicate balance between bacterial virulence and protection of the host.

To evaluate the feasibility of different LPS modifications for bacterium-mediated cancer therapy, ΔrfaL, ΔrfaG, ΔrfaH, ΔrfaD, ΔrfaP, and ΔmsbB mutants were investigated. The ΔrfaL, ΔrfaG, and ΔrfaH mutants have already been tested for their potential as vaccine strains (16, 20), and the ΔmsbB mutant gave rise to VNP20009 and has been intensively studied for use in cancer therapy (10). The LPS mutants exhibited the expected alterations of their LPS structure, as confirmed by SDS-PAGE and resistance to bacteriophage P22. Furthermore, the lack of an appropriate LPS structure strongly decreased the motility of the ΔrfaD, ΔrfaG, and ΔrfaL mutants, indicating that altered LPS interferes with either the chemotaxis machinery or production and assembly of flagella.

Transmission electron microscopy of negatively stained ΔrfaD mutant bacteria indicated that the lack of motility is likely due to a highly decreased number of flagella on the surface of these bacteria. However, the precise mechanism resulting in this nonmotile phenotype has not been established yet.

All of the LPS mutants tested were able to colonize different types of solid tumors, although the process of bacterial tumor colonization is not entirely clear. When using tumor cylindroids in vitro, chemotaxis and motility of the bacteria were required (21). However, recent in vivo experimental data suggest that colonization of tumor tissue is a passive event. Mutants lacking motility or chemotaxis genes colonized cancerous tissue in mice to the same extent as the WT (22, 23). Consistently, the same was observed in this study in the nonmotile ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG mutants.

The importance of TNF-α release during the tumor colonization process and for induction of hemorrhagic necrosis has been shown recently (13). This phenomenon appears to be an important mediator of invasion but also of an early and strong antitumor response. Bacteria might reach the tumor via the vascular leakage induced by TNF-α. When using the deep rough LPS ΔrfaD mutant, severe hemorrhagic necrosis was not observed macroscopically. This is probably due to the reduced induction of TNF-α, although tumor colonization was reduced only during the early stages of infection. Interestingly, tumor colonization was found to be independent of MyD88−/− (24) and took place in Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient C3H/HeJ mice (25). An alternative entry pathway might exist that is independent of TLR4 signaling induced by Salmonella LPS since tumor colonization was observed in TLR4- and MyD88-deficient mice.

For instance, the well-known leakiness of tumor neovasculature could lead to a shift in the Starling forces and result in increased interstitial flow from blood toward the lymphatic vessels (26). This might already be sufficient to initiate the colonization of tumor tissue by bacteria.

The tumor specificity of bacteria was shown to depend on immune-mediated clearance from systemic sites and the persistence of bacteria in cancerous tissue. Indeed, in the present work, highly truncated LPS mutants like the ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG mutants showed the highest specificity for tumors and the lowest burden for the mice. The fast clearance of such microorganisms from blood indicates that innate immune effector mechanisms are involved, with macrophages probably being the most important component. In accordance, phagocytic uptake by macrophages was strongly increased when the O antigen was missing. This was reversed when the core structure was further truncated, indicating the importance of the core sugars for immune recognition. However, only the ability to replicate intracellularly appears to be important. Replication of the deep rough LPS ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG mutants was greatly reduced, and especially the ΔrfaD mutant was cleared efficiently by macrophages. This could explain the in vivo findings. Bacteria that are readily phagocytosed but are able to replicate cause a lethal infection in mice. In contrast, bacteria with WT-like or increased uptake that are not able to replicate intracellularly are highly attenuated.

Thus, because of their safety profile, the ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG mutants appeared to be the most promising and were therefore followed up for their intrinsic antitumor effect. Unfortunately, the therapeutic effect of the unmodified ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG variants was found to be weaker than that of SL7207, which was previously employed in our experiments (18, 19, 22, 27). These findings are consistent with LPS being an important inductive molecule for the antitumor effect. The lower level of TNF-α and other cytokines induced by infection with these strains most likely explains the weaker tumor-clearing efficiency observed. To improve their antitumor efficacy, these strains were modified to increase the induction of cytokines without increasing the safety risk.

A conditional-attenuation approach was employed. A similar strategy has been intensively elaborated by the Curtiss lab to design potent bacterial vaccines (28, 29). In the present work, different constructs were designed to achieve conditional or delayed attenuation. All of these constructs rely on complementation of the truncated LPS under the control of an inducible promoter.

The leakiness of the arabinose-inducible promoter used was a major problem. Even when introduced on low-copy-number plasmids, the LPS structure of the deletion mutants was comparable to that of the WT. Probably because of the long half-life of LPS, no quantitative differences were noticed independent of the copy number. The problem was overcome only when the construct was placed chromosomally under the control of PBAD.

Induction of complementation by the addition of arabinose to the bacterial cultures completely restored the LPS of the ΔrfaD and ΔrfaG variants to the WT pattern. In addition, resistance to human complement and phagocytic uptake could be restored upon induction. After removal of arabinose from the cultures, the WT LPS pattern disappeared within 3 h. In the case of the ΔrfaD mutant, the shift was complete and no O-antigen structures could be detected anymore. In contrast, the complementing construct of rfaG could not be silenced completely. WT structures were visible, although at lower intensities. In addition, the conditionally complemented rfaG variant in a noninduced state remained lethal for mice. Thus, for unknown reasons, constructs complementing rfaD were less leaky than the ones complementing rfaG. Alternatively, higher rfaD expression levels might be needed to restore the WT LPS phenotype. We therefore conclude that the chromosomally inducible ΔaraBAD::PBAD rfaD complementation mutant represents a variant with appropriate regulation of the LPS structure and an intrinsic antitumor effect in the induced state. We cannot exclude a contribution of restored flagellum expression to the antitumor effect. Although we find it unlikely that the regained motility contributes to the activity, expression of flagella could boost the adjuvant effect.

In summary, the use of conditional complementation mutants of LPS variants like the rfaD complementation strain appears to be a promising strategy to establish a safe and therapeutically effective strain for tumor therapy. To improve compliance, additional mutations to also metabolically attenuate the bacteria might be required. In addition, the strains should be further evaluated in orthotopic and autochthonous tumor systems to validate the present results. Nevertheless, we consider our findings an important step toward a clinical application.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

All animal experiments were performed according to guidelines of the German Law for Animal Protection and with the permission of the local ethics committee and the local authority LAVES (Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit) under permission no. 33.9-42502-04-12/0713.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

For the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study and their genotypes and sources, see Table S1 in the supplemental material. The bacteria were grown in LB medium at 37°C either to mid-log phase for subculturing (3 h) or overnight. For induction of PBAD-controlled expression, 0.2 % (wt/vol) arabinose was added to the subculture before inoculation.

Complementing constructs.

The vector backbones pHL302 (30) and pCMVm4A (31) were digested with SdaI/XhoI and PstI/XbaI, respectively (Fermentas). The rfaD and rfaG genes from ATCC 14028 were amplified via PCR with primers with the corresponding restriction sites as overhangs. In the case of low-copy-number plasmid pCMVm4A, the PBAD promoter had been transferred from pHL302 before. For chromosomal integration into the araBAD locus, the araBAD locus was exchanged with the rfaD and rfaG genes by lambda Red-mediated recombination (32, 33). For the corresponding primers, see Table S2 in the supplemental material.

LPS phenotype of mutants.

All strains were cultured overnight in LB medium. Preparation of LPS was done as described in reference 28. LPS was separated by 16.5% Mini-Protean Tris-Tricine Gel (BioRad) SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining. As a WT control, the LPS of ATCC 14028 was used.

Motility assay.

Semisolid swimming plates containing 0.3% (wt/vol) agar were prepared. Single colonies were picked with a toothpick and spotted into the agar. After 4 h at 37°C, mutant strain motility was assayed by measuring the swarm diameter and compared to WT motility.

Electron microscopy.

The mutants were cultured in 5 ml of LB or minimal medium overnight. On the next day, 650 µl of glutaraldehyde (final concentration, 2%) was added to fix the bacteria. The mixture was stored in the refrigerator at 4°C. For transmission electron microscopic observation, bacteria were negatively stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate with a carbon film deposited on mica. Samples were examined in a Zeiss TEM 910 at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV with calibrated magnifications. Images were recorded digitally with a Slow-Scan charge-coupled device camera (ProScan, 1,024 by 1,024) with ITEM-Software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions).

Complement sensitivity.

Human blood was taken from volunteers, and the serum was isolated with Microvette serum tubes (Sarstedt). Bacteria were adjusted to 2 × 107 CFU and challenged with the serum by mixing it 1:1. Serum prepared by heat inactivation at 56°C for 2 h served as a control. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The remaining CFU were determined by plating.

Invasion assay.

J774 cells and primary BMDM were used to determine the phagocytic uptake and intracellular replication of the bacteria. The assay was performed as described previously (34). A total of 8 × 105 cells were seeded into the wells of a 24-well plate and infected with bacteria (multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 1). Uptake was assayed at 2 hpi by removing the supernatant and determining the CFU count inside the macrophages by plating. The intracellular replication was analyzed at 18 hpi by the same procedure. All values were compared to WT levels.

Murine tumor model.

Six- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice (Janvier) were intradermally inoculated with 5 × 105 syngeneic tumor cell lines. CT26 (colorectal cancer, ATCC CRL-2638), RenCa (renal adenocarcinoma), and F1A11 (fibrosarcoma) cells were used in this study. Tumor growth was monitored with a caliper. When the tumors reached a volume of approximately 150 mm³, the mice were infected intravenously with 5 × 106 salmonellae suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Therapeutic benefit and bacterial burden.

Tumor development after infection was monitored until the tumors either were cleared or outgrew (reached >1,000 mm³). In addition, body weight was measured. Mice were euthanized once their weight dropped below 80% of their initial weight. In order to determine the bacterial burden, blood, spleen, livers, and tumors were harvested at 12 and 36 hpi and treated as described previously (13). CFU were counted, and the bacterial burden was calculated as the total number of CFU per gram of tissue.

TNF-α measurement in serum.

Blood samples were collected at 1.5, 3, and 12 hpi. The TNF-α ELISA Max Standard kit (BioLegend) was used to determine the TNF-α level in serum. All steps were done according to the manufacturer’s manual. Three different biological replicates were analyzed, and a PBS-treated group served as a negative control.

In vivo depletion of macrophages.

Clodronate liposomes (0.3 to 3 µm; Clodrosome) were used to deplete macrophages. Two days before infection, 750 µg of clodronate liposomes was administered intravenously (i.v.) to the mice. The procedure was repeated 1 day before infection (500 µg given intraperitoneally). Empty liposomes served as a control. The efficiency of macrophage (CD11b+ F4/80+ CD11c− cells) depletion from the blood was monitored by flow cytometry.

In vivo depletion of complement system.

Twelve hours before infection with salmonellae, the mice were treated i.v. with 5 IU of CVF (Quidel Corporation) to deplete the complement system in their blood. Blood samples were taken 12 h before and 3 and 7 h after CVF administration in order to monitor complement depletion. C3a levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; TECO development GmbH).

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed with the two-tailed Student t test, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Growth curve of Salmonella LPS mutants in LB medium. Growth was determined in LB medium with continuous shaking at 37°C. Optical density was measured with a wideband (420 to 580 nm) filter. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five biological replicates per group. Download

Colonization profile of the ΔrfaG mutant in RenCa- or F1A11-bearing BALB/c mice. Mice were infected i.v. with 5 × 106 CFU. The number of bacteria was determined by plating of serial dilutions of tissue homogenates. Similar levels were found in various tumor systems. The mean and standard deviation are displayed. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five mice per group. Download

Bacterial loads in blood upon infection with LPS variants. Mice were infected i.v. with 5 × 106 CFU. The number of bacteria was determined by plating of serial dilutions of tissue homogenates. The median and range are displayed. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five mice per group. Download

C3a levels in sera of complement-depleted mice measured by ELISA. Serum samples were taken 12 h before and 3 and 7 h after CVF administration. The 7-h time point is 4 hpi with the ΔrfaD mutant. CVF led to a significant reduction, but not complete elimination, of C3a. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five mice per group. Download

Sensitivity of LPS Salmonella mutants to BMDM. (A) BMDM cells were infected at an MOI of 1, and phagocytic uptake was determined relative to that of the WT after 1 h. Results similar to those obtained with J774 cells were obtained. (B) Intracellular replication of LPS mutants within BMDM. Cells were allowed to phagocytize the bacteria as in panel A. Infected cells were incubated for 18 h, and the remaining bacterial burden was determined by plating. Again, results similar to those obtained with J774 cells were obtained. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five biological replicates per group. Download

Efficiency of clodronate depletion in vivo. CD11b+ F4/80+ cells in blood were monitored via flow cytometry after clodronate administration. Quantitation (A) and the gating strategy used (B) are shown. Almost complete depletion of CD11b+ F4/80+ cells was achieved. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five mice per group. Download

Sensitivity of the conditionally complemented ΔaraBAD::PBAD rfaD mutant to human complement. A total of 2 × 107 bacteria were treated with either untreated or heat-inactivated (HI) human serum for 30 min at 37°C. The lysis effect was determined by plating. Upon induction with arabinose, the WT phenotype was restored to the chromosomally rfaD-complemented strains. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five biological replicates per group. Download

Sensitivity of the conditional complemented ΔaraBAD::PBAD rfaD mutant to BMDM. (A) BMDM cells were infected at an MOI of 1, and phagocytic uptake relative to that of the WT was determined after 1 h. (B) Intracellular replication of LPS mutants within BMDM. Cells were allowed to phagocytize bacteria as in panel A. Infected cells were incubated for 18 h, and the remaining bacterial burden was determined by plating. In both cases, the WT phenotype was restored upon arabinose induction. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five biological replicates per group. Download

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely thank Susanne zur Lage, Regina Lesch, and Ina Schleicher for expert technical assistance. We also thank Olga Selich and Alfonso Felipe-López for the construction of mutant strains.

This work was supported in part by the Deutsche Krebshilfe, the Federal Ministry for Education and Research, Helmholtz Association young investigator grant VH-NG-932, and the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (grant 334030 to M.E.). R.C. was supported by grant NIAID/NIH R01AI060557. M.H. was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant HE1964/14-1. M.F. was funded by the Hannover Biomedical Research School and the Helmholtz Center for Infection Research. S.F. was funded in the zoonosis Ph.D. program via a Lichtenburg Fellowship from the Niedersächsiche Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kultur.

Footnotes

Citation Frahm M, Felgner S, Kocijancic D, Rohde M, Hensel M, Curtiss R, III, Erhardt M, Weiss S. 2015. Efficiency of conditionally attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in bacterium-mediated tumor therapy. mBio 6(2):e00254-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.00254-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Couzin-Frankel J. 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Scientist 342:1432–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ito F, Chang AE. 2013. Cancer immunotherapy: current status and future directions. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 22:765–783. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruella M, Kalos M. 2014. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer. Immunol Rev 257:14–38. doi: 10.1111/imr.12136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coley WB. 1898. The treatment of inoperable sarcoma with the ’mixed toxins of Erysipelas and Bacillus prodigiosus. Immediate and final results in one hundred and forty cases. J Am Med Assoc 31:389–395. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nauts HC, Fowler GA, Bogatko FH. 1953. A review of the influence of bacterial infection and of bacterial products (Coley’s toxins) on malignant tumors in man; a critical analysis of 30 inoperable cases treated by Coley’s mixed toxins, in which diagnosis was confirmed by microscopic examination selected for special study. Acta Med Scand Suppl 276:1–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nauts HC, McLaren JR. 1990. Coley toxins—the first century, p 483–500. In Bicher HI, McLaren JR, Pigliucci GM (ed), Consensus on hyperthermia for the 1990s: clinical practice in cancer treatment. Springer, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choe E, Kazmierczak RA. 2014. Phenotypic evolution of therapeutic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium after invasion of TRAMP mouse prostate tumor. mBio 5(4):e01182-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01182-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krick EL, Sorenmo KU, Rankin SC, Cheong I, Kobrin B, Thornton K, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhou S, Diaz LA. 2012. Evaluation of Clostridium novyi-NT spores in dogs with naturally occurring tumors. Am J Vet Res 73:112–118. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.73.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts NJ, Zhang L, Janku F, Collins A, Bai R-Y, Staedtke V, Rsk AW, Tung D, Miller M, Roix J, Khanna KV, Murthy R, Benjamin RS, Helgason T, Szvalb AD, Bird JE, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Zhang HH, Qiao Y, Karim B, McDaniel J, Elpiner A, Sahora A, Lachowicz J, Phillips B, Turner A, Klein MK, Post G, Diaz LA, Riggins GJ, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Bettegowda C, Huso DL, Varterasian M, Saha S, Zhou S. 2014. Intratumoral injection of Clostridium novyi-NT spores induces antitumor responses. Sci Transl Med 6:249ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toso JF, Gill VJ, Hwu P, Marincola FM, Restifo NP, Schwartzentruber DJ, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Yang JC, Stock F, Freezer LJ, Morton KE, Seipp C, Haworth L, Mavroukakis S, White D, MacDonald S, Mao J, Sznol M, Rosenberg SA. 2002. Phase I study of the intravenous administration of attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium to patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 20:142–152. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forbes NS. 2010. Engineering the perfect (bacterial) cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 10:785–794. doi: 10.1038/nrc2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao M, Yang M, Ma H, Li X, Tan X, Li S, Yang Z, Hoffman RM. 2006. Targeted therapy with a Salmonella Typhimurium leucine-arginine auxotroph cures orthotopic human breast tumors in nude mice. Cancer Res 66:7647–7652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leschner S, Westphal K, Dietrich N, Viegas N, Jablonska J, Lyszkiewicz M, Lienenklaus S, Falk W, Gekara N, Loessner H, Weiss S. 2009. Tumor invasion of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is accompanied by strong hemorrhage promoted by TNF-α. PLoS One 4:e6692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chorawala MR, Oza PM, Trivedi VR, Deshpande SS, Shah GB. 2013. Lipopolysaccharides: an overview. World Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2:465–477. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong Q, Six DA, Roland KL, Liu Q, Gu L, Reynolds CM, Wang X, Raetz CR, Curtiss R. 2011. Salmonella synthesizing 1-dephosphorylated lipopolysaccharide exhibits low endotoxic activity while retaining its immunogenicity. J Immunol 187:412–423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong Q, Yang J, Liu Q, Alamuri P, Roland KL, Curtiss R. 2011. Effect of deletion of genes involved in lipopolysaccharide core and O-antigen synthesis on virulence and immunogenicity of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun 79:4227–4239. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05398-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aachoui Y, Leaf IA, Hagar JA, Fontana MF, Campos CG, Zak DE, Tan MH, Cotter PA, Vance RE, Aderem A, Miao EA. 2013. Caspase-11 protects against bacteria that escape the vacuole. Science 339:975–978. doi: 10.1126/science.1230751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westphal K, Leschner S, Jablonska J, Loessner H, Weiss S. 2008. Containment of tumor-colonizing bacteria by host neutrophils. Cancer Res 68:2952–2960. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leschner S, Weiss S. 2010. Salmonella—allies in the fight against cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 88:763–773. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0636-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zenk SF, Jantsch J, Hensel M. 2009. Role of Salmonella enterica lipopolysaccharide in activation of dendritic cell functions and bacterial containment. J Immunol 183:2697–2707. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasinskas RW, Forbes NS. 2007. Salmonella Typhimurium lacking ribose chemoreceptors localize in tumor quiescence and induce apoptosis. Cancer Res 67:3201–3209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crull K, Bumann D, Weiss S. 2011. Influence of infection route and virulence factors on colonization of solid tumors by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 62:75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stritzker J, Weibel S, Seubert C, Götz A, Tresch A, van Rooijen N, Oelschlaeger TA, Hill PJ, Gentschev I, Szalay AA. 2010. Enterobacterial tumor colonization in mice depends on bacterial metabolism and macrophages but is independent of chemotaxis and motility. Int J Med Microbiol 300:449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaimala S, Mohamed YA, Nader N, Issac J, Elkord E, Chouaib S, Fernandez-Cabezudo MJ, Al-Ramadi BK. 2014. Salmonella-mediated tumor regression involves targeting of tumor myeloid suppressor cells causing a shift to M1-like phenotype and reduction in suppressive capacity. Cancer Immunol Immunother 63:587–599. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1543-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee C-H, Wu C-L, Shiau A-L. 2008. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates an antitumor host response induced by Salmonella choleraesuis. Clin Cancer Res 14:1905–1912. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swartz MA, Lund AW. 2012. Lymphatic and interstitial flow in the tumour microenvironment: linking mechanobiology with immunity. Nat Rev Cancer 12:210–219. doi: 10.1038/nrc3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoiseth SK, Stocker BA. 1981. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella Typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong Q, Liu Q, Jansen AM, Curtiss R. 2010. Regulated delayed expression of rfc enhances the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a heterologous antigen delivered by live attenuated Salmonella enterica vaccines. Vaccine 28:6094–6103. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kong Q, Liu Q, Roland KL, Curtiss R. 2009. Regulated delayed expression of rfaH in an attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine enhances immunogenicity of outer membrane proteins and a heterologous antigen. Infect Immun 77:5572–5582. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00831-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loessner H, Leschner S, Endmann A, Westphal K, Wolf K, Kochruebe K, Miloud T, Altenbuchner J, Weiss S. 2009. Drug-inducible remote control of gene expression by probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in intestine, tumor and gall bladder of mice. Microbes Infect 11:1097–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bauer H, Darji A, Chakraborty T, Weiss S. 2005. Salmonella-mediated oral DNA vaccination using stabilized eukaryotic expression plasmids. Gene Ther 12:364–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karlinsey JE. 2007. Lambda-red genetic engineering in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Methods Enzymol 421:199–209. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)21016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gahring LC, Heffron F, Finlay BB, Falkow S. 1990. Invasion and replication of Salmonella typhimurium in animal cells. Infect Immun 58:443–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Growth curve of Salmonella LPS mutants in LB medium. Growth was determined in LB medium with continuous shaking at 37°C. Optical density was measured with a wideband (420 to 580 nm) filter. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five biological replicates per group. Download

Colonization profile of the ΔrfaG mutant in RenCa- or F1A11-bearing BALB/c mice. Mice were infected i.v. with 5 × 106 CFU. The number of bacteria was determined by plating of serial dilutions of tissue homogenates. Similar levels were found in various tumor systems. The mean and standard deviation are displayed. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five mice per group. Download

Bacterial loads in blood upon infection with LPS variants. Mice were infected i.v. with 5 × 106 CFU. The number of bacteria was determined by plating of serial dilutions of tissue homogenates. The median and range are displayed. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five mice per group. Download

C3a levels in sera of complement-depleted mice measured by ELISA. Serum samples were taken 12 h before and 3 and 7 h after CVF administration. The 7-h time point is 4 hpi with the ΔrfaD mutant. CVF led to a significant reduction, but not complete elimination, of C3a. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five mice per group. Download

Sensitivity of LPS Salmonella mutants to BMDM. (A) BMDM cells were infected at an MOI of 1, and phagocytic uptake was determined relative to that of the WT after 1 h. Results similar to those obtained with J774 cells were obtained. (B) Intracellular replication of LPS mutants within BMDM. Cells were allowed to phagocytize the bacteria as in panel A. Infected cells were incubated for 18 h, and the remaining bacterial burden was determined by plating. Again, results similar to those obtained with J774 cells were obtained. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five biological replicates per group. Download

Efficiency of clodronate depletion in vivo. CD11b+ F4/80+ cells in blood were monitored via flow cytometry after clodronate administration. Quantitation (A) and the gating strategy used (B) are shown. Almost complete depletion of CD11b+ F4/80+ cells was achieved. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five mice per group. Download

Sensitivity of the conditionally complemented ΔaraBAD::PBAD rfaD mutant to human complement. A total of 2 × 107 bacteria were treated with either untreated or heat-inactivated (HI) human serum for 30 min at 37°C. The lysis effect was determined by plating. Upon induction with arabinose, the WT phenotype was restored to the chromosomally rfaD-complemented strains. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five biological replicates per group. Download

Sensitivity of the conditional complemented ΔaraBAD::PBAD rfaD mutant to BMDM. (A) BMDM cells were infected at an MOI of 1, and phagocytic uptake relative to that of the WT was determined after 1 h. (B) Intracellular replication of LPS mutants within BMDM. Cells were allowed to phagocytize bacteria as in panel A. Infected cells were incubated for 18 h, and the remaining bacterial burden was determined by plating. In both cases, the WT phenotype was restored upon arabinose induction. Results are representative of two independent experiments with five biological replicates per group. Download

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.