WY: An 18-year-old footballer with no previous significant medical history sustained a tendon injury during a football match. This was repaired successfully under general anaesthetic, but the SaO2 (% saturation of haemoglobin) was found to be 78.5% on air. Following recovery from the injury, he returned to playing football six times per week while he was investigated further. Chest X-ray and CT scan demonstrated three pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (PAVMs) that were thought to be due to underlying hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT).

CLS: That would be the most likely cause of the clinical picture. PAVMs1 affect approximately 1 in 2600 people,2 have usually completed growth by puberty and frequently result in hypoxaemia.3 The PAVM vessels provide an anatomic right-to-left shunt that allows a fraction of pulmonary arterial blood to bypass the pulmonary capillary bed and hence gas exchange. Greater shunt flow (as a proportion of cardiac output) results in lower PaO2/SaO2, but this is frequently asymptomatic. The majority of patients have underlying HHT, especially if they have multiple PAVMs.

WY: How was it possible for him to be so sporty?

CLS: The relevant term for oxygen transport to the tissues is not the SaO2 or PaO2 (in kPa or mm Hg), but the arterial oxygen content (CaO2 (mL of oxygen per unit blood volume)). CaO2 depends on the concentration of haemoglobin in addition to the commonly measured oxygen parameters. I would predict that the patient had secondary polycythaemia at presentation.

WY: Yes, the haemoglobin was 20.9 g/dL and haematocrit 0.61%.

CLS: So this will have maintained his CaO2, which we can calculate as SaO2×haemoglobin×1.34/100. His CaO2 was 22 mL/dL, which is higher than normal, as seen in 23 athletes with PAVMs, compared with 121 non-athletic patients with PAVMs and normal exercise tolerance.3 As discussed elsewhere,1 3 athletic training increases the red cell mass, and it seems for patients with PAVMs, they may adapt to meet oxygen demands on exercise. On cardiopulmonary exercise testing of 21 patients with PAVMs, maximal work rate and oxygen consumption (V[dot]O2) were no lower in more hypoxaemic patients.4

WY: But what if the PaO2/SaO2 falls suddenly? His SaO2 fell by 10% from lying to standing.

CLS: A fall in SaO2 on standing (orthodeoxia) is common in patients with PAVMs: in a recent series, 75/257 (29%) consecutive patients with PAVMs demonstrated a fall in SaO2 of at least 2% on standing.5 Obviously, the bone marrow does not respond within minutes to hours, and there is therefore an acute fall in CaO2.

WY: So his CaO2 will have fallen by 2.6 mL/dL—is this why his pulse rose by 49 bpm on standing?

CLS: In the 257 patients with PAVMs reported recently, an exuberant postural tachycardia did appear to be part of the compensatory mechanism to acute falls in SaO2/CaO2.5 This evokes similarities with the tachycardic response to blood volume depletion and/or haemorrhage—similar baroreceptor mechanisms may be operating.

WY: Oxygen guidelines6 would recommend supplementary oxygen for an SaO2 of 78.5% at rest.

CLS: Patients with PAVMs do not fit into any of the groups considered in the normal oxygen guidelines. Oxygen supplementation is helpful in the alleviation of symptoms in hypoxaemic patients with PAVMs, for example, if they are breathless, have cardiac symptoms such as angina or palpitations, or describe neurological symptoms. It is important to remember that there is no rationale to prescribe oxygen to alleviate pulmonary hypertension because PAVMs are not associated with alveolar hypoxia, and patients are not at risk of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension.3 4

WY: Don't the polycythaemia guidelines7 suggest that this patient should have been venesected?

CLS: Maybe, but only if you think his PAVMs meant he should be considered as having a respiratory disease, when venesection of the asymptomatic patient is recommended.

DML: There is evidence venesection may be of benefit to patients with erythrocytosis secondary to hypoxic pulmonary disease in terms of effort tolerance and neurocognitive function, which mirror improvement in pulmonary vascular resistance and cerebral blood flow. This was initially demonstrated in patients with cor pulmonale. Current guidelines7 recommend venesection is considered if the haematocrit is >0.56 or if there are symptoms of hyperviscosity. PAVMs, however, differ from other forms of hypoxic pulmonary disease due to airflow obstruction or interstitial lung disease.

CLS: The pathology most resembling PAVMs is cyanotic congenital heart disease for which the polycythaemia guidelines7 only recommend venesection if the patient describes symptoms of hyperviscosity. In this case, as the haematocrit was so high (0.61%), venesection was considered. However, since embolisation was scheduled to take place shortly after review, the decision was deferred until after correction of hypoxaemia. Venesection is not without risk: inducing iron deficiency by venesection is likely to be detrimental, not only in terms of increased cardiac demands to maintain tissue oxygen delivery but also because iron deficiency is now recognised to be a strong risk factor for paradoxical embolic stroke in patients with PAVMs: In a series of 497 consecutive patients with CT-proven pulmonary AVMs, the stroke risk was 4% higher for every µmol/L fall in serum iron, implying for the same PAVM(s) the stroke risk would approximately double with serum iron 6 µmol/L compared with mid-normal range (7–27 µmol/L).8

WY: And stroke prevention was why treatment of this patient's PAVMs was recommended. He underwent a series of embolisation treatments.

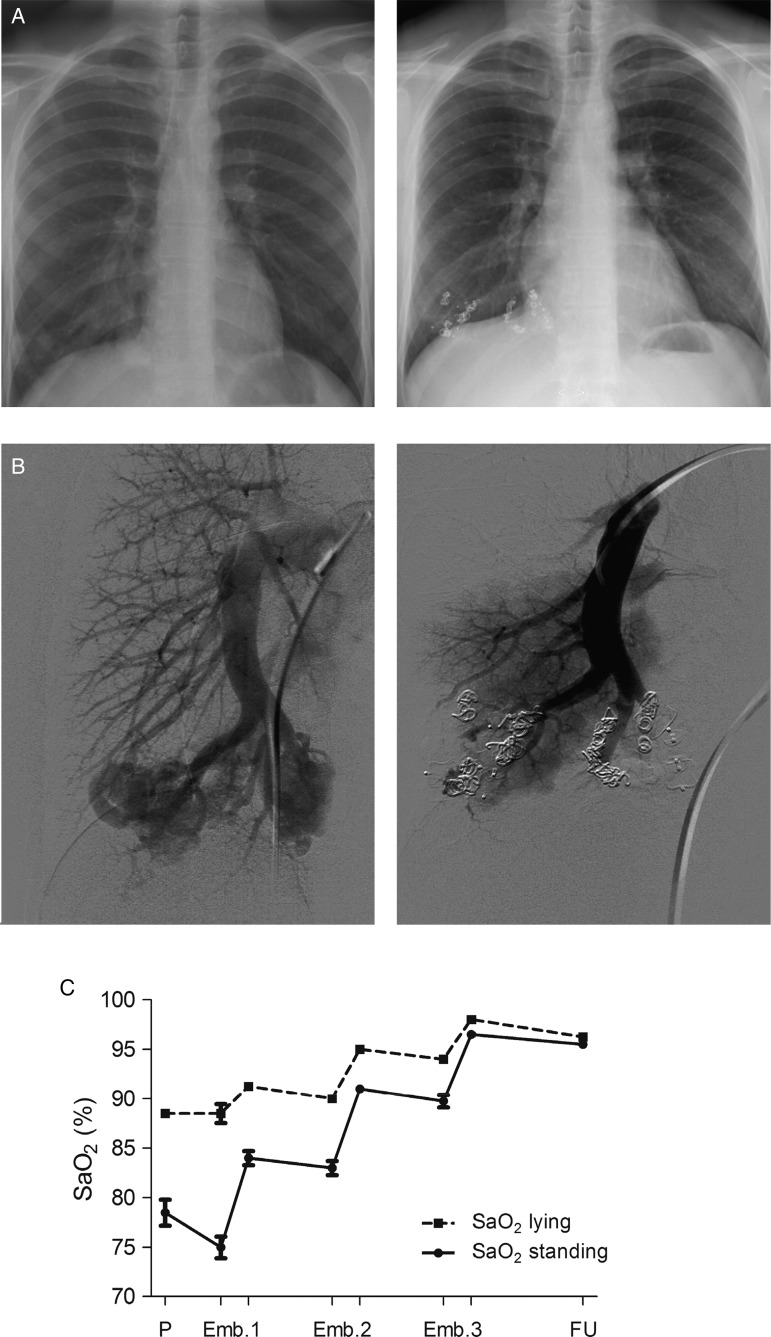

JEJ: All three of this young man's PAVMs had a complex angiographic anatomy; in other words, each consisted of numerous arteriovenous communications arising from multiple adjacent peripheral pulmonary arterial branches. This is opposed to the more common ‘simple’ anatomy where there is a single feeding vessel communicating directly with a venous sac. The successful embolisation of complex lesions is difficult and, in this case, required three separate procedures in order to occlude the majority of the abnormal arteriovenous communications using a combination of Amplatzer vascular plugs and MR-compatible metallic coils (figure 1A, B).

Figure 1.

Case details. (A) Chest X-ray pre (left) and 4 years post (right) embolisation. (B) Angiographic appearances of the complex pulmonary arteriovenous malformations pre (left) and post (right) embolisation using a combination of coils and Amplatzer plugs over three embolisation sessions. (C) Serial SaO2 measured by pulse oximetry after 7, 8, 9 and 10 min in each posture. Mean and SEM displayed at presentation (P), before and after each embolisation (Emb.), and at follow-up (FU).

WY: Four years later, the SaO2 was 95% on air (figure 1C). He was about to resume football (which he had stopped playing for social reasons), but did state “I don't feel any different – but then I felt completely fine before.” Why did he feel no better when his SaO2 was now almost normal?

CLS: You can work this out. What was his haemoglobin on follow-up?

WY: The haemoglobin had fallen to 15.6 g/dL with normochromic normocytic indices and no evidence of iron deficiency.

CLS: The fall in haemoglobin means that the CaO2 was no higher than at presentation, despite the increased SaO2. Across 71 patients with PAVMs, haemoglobin fell after embolisation such that several months after embolisation the CaO2 was no higher despite higher SaO2.3 At 20 mL/dL, his CaO2 was in fact a little lower than at presentation, potentially reflecting his reduced sporting training. There are no cardiopulmonary exercise data for him, but data are reported on five other patients with PAVMs, exercised before and several months after embolisation that increased SaO2 from 88–94% to 94–96% (p=0.009): there was no difference in perceived dyspnoea, maximum workload or maximal oxygen consumption (V[dot]O2) after embolisation. So patients with PAVMs use compensatory processes to preserve oxygen delivery to the tissues, even on exercise, and reset these after correction of hypoxaemia.3 4 9

WY: Does everyone with PAVM-induced hypoxaemia manage this well?

CLS: No, not everyone. Concurrent diseases interfere with the ability to compensate. The most common problems we see are iron deficiency (leading to a spectrum that ranges from anaemia to ‘just’ impaired polycythaemia/inappropriately normal haemoglobin2) and/or concurrent cardiorespiratory disease. Patients with PAVMs and these additional problems tend to report more dyspnoea, are less able to exercise and are more likely to report improvements after embolisation.2 Their symptoms are remarkably similar to those of pure anaemia, which effectively results in the same problem—it is harder work to deliver oxygen to the tissues.

In summary, this case illustrates how successfully haematological and cardiovascular compensations can maintain oxygen delivery to the tissues in hypoxaemic patients with PAVMs. Do not forget, however, that patients with PAVMs are unusual in their ability to compensate for hypoxaemia: the PAVM results on tolerance of hypoxemia3 4 should not be extrapolated to other hypoxaemic patients, where more usual oxygen guidance as used in acute and respiratory medicine applies.

Footnotes

Contributors: WY wrote the first draft of the case-based discussion and approved the final manuscript. JEJ performed the embolisations, contributed to the text and approved the final manuscript. DML contributed to the text and approved the final manuscript. CLS reviewed the patient, wrote the final manuscript and generated the figure.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Hammersmith, Queen Charlotte's, Chelsea, and Acton Hospital Research Ethics Committee (LREC 2000/5764: 'Case Notes Review: Hammersmith Hospital patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations and hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT)'.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Shovlin CL. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;190:1217–28. 10.1164/rccm.201407-1254CI [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakayama M, Nawa T, Chonan T, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations as estimated by low-dose thoracic CT screening. Intern Med 2012;51:677–81. 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santhirapala V, Williams LC, Tighe HC, et al. Arterial oxygen content is precisely maintained by graded erythrocytotic responses in settings of high/normal serum iron levels, and predicts exercise capacity. An observational study of hypoxaemic patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. PLoS ONE 2014:9:e90777 10.1371/journal.pone.0090777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard L, Santhirapala V, Murphy K, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise tests demonstrate maintenance of exercise capacity in hypoxemic patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Chest 2014:146:709–18. 10.1378/chest.13-2988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santhirapala V, Chamali B, McKernan H, et al. Orthodeoxia and postural orthostatic tachycardia in patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: a prospective 8-year series. Thorax 2014;69:1046–7. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee Clinical component for the home oxygen service in England and Wales. 2006. http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/Portals/0/ClinicalInformation/HomeOxygenService/clinicaladultoxygenjan06.pdf

- 7.McMullin MF, Bareford D, Campbell P, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis, investigation and management of polycythaemia/erythrocytosis. Br J Haematol 2005;130:174–95. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shovlin CL, Chamali B, Santhirapala V, et al. Ischaemic strokes in patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations and hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: associations with iron deficiency and platelets. PLoS ONE 2014:9:e88812 10.1371/journal.pone.0088812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vorselaars VM, Velthuis S, Mager JJ, et al. Direct haemodynamic effects of pulmonary arteriovenous malformation embolisation. Neth Heart J 2014;22:328–33. 10.1007/s12471-014-0539-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]