Photosynthesis and growth in anoxia depends on hydrogenase-dependent linear electron flow.

Abstract

The model green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is frequently subject to periods of dark and anoxia in its natural environment. Here, by resorting to mutants defective in the maturation of the chloroplastic oxygen-sensitive hydrogenases or in Proton-Gradient Regulation-Like1 (PGRL1)-dependent cyclic electron flow around photosystem I (PSI-CEF), we demonstrate the sequential contribution of these alternative electron flows (AEFs) in the reactivation of photosynthetic carbon fixation during a shift from dark anoxia to light. At light onset, hydrogenase activity sustains a linear electron flow from photosystem II, which is followed by a transient PSI-CEF in the wild type. By promoting ATP synthesis without net generation of photosynthetic reductants, the two AEF are critical for restoration of the capacity for carbon dioxide fixation in the light. Our data also suggest that the decrease in hydrogen evolution with time of illumination might be due to competition for reduced ferredoxins between ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase and hydrogenases, rather than due to the sensitivity of hydrogenase activity to oxygen. Finally, the absence of the two alternative pathways in a double mutant pgrl1 hydrogenase maturation factor G-2 is detrimental for photosynthesis and growth and cannot be compensated by any other AEF or anoxic metabolic responses. This highlights the role of hydrogenase activity and PSI-CEF in the ecological success of microalgae in low-oxygen environments.

Unicellular photosynthetic organisms such as the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii frequently experience anoxic conditions in their natural habitat, especially during the night when the microbial community consumes the available oxygen. Under anoxia, lack of ATP synthesis by F1FO ATP synthase (EC 3.6.3.14) due to the absence of mitochondrial respiration is compensated by the activity of various plant- and bacterial-type fermentative enzymes that drive a sustained glycolytic activity (Mus et al., 2007; Terashima et al., 2010; Grossman et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2014). In C. reinhardtii, upstream glycolytic enzymes, including the reversible glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase, are located in the chloroplast (Johnson and Alric, 2012). This last enzyme is shared by the glycolysis (oxidative activity) and the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle (reductive activity; Johnson and Alric, 2013). In dark anoxic conditions, the CBB cycle is inactive, thus avoiding wasteful using up of available ATP and depletion of the required intermediates for glycolysis. On the other side, ability of microalgae to perform photosynthetic carbon fixation when transferred from dark to light in the absence of oxygen might also be critical for adaptation to their environment. In such conditions, not only the linear electron flow (LEF) to Rubisco, but also alternative electron flow (AEF) toward oxygen (chlororespiration, Mehler reaction, and mitochondrial respiration; for review, see Miyake, 2010; Peltier et al., 2010; Cardol et al., 2011) is impaired. Thus, cells need to circumvent a paradoxical situation: the activity of the CBB cycle requires the restoration of the cellular ATP, but the chloroplastic F1FO ATP synthase activity is compromised by the impairment of most of the photosynthetic electron flows that usually generate the proton motive force in oxic conditions. Other AEFs, specific to anoxic conditions, should therefore be involved to promote ATP synthesis without net synthesis of NADPH and explain the light-induced restoration of CBB cycle activity.

Among enzymes expressed in anoxia, the oxygen-sensitive hydrogenases (HYDA1 and HYDA2 in C. reinhardtii) catalyze the reversible reduction of protons into molecular hydrogen from the oxidation of reduced ferredoxins (FDXs; Florin et al., 2001). Although hydrogen metabolism in microalgae has been largely studied in the last 15 years in perspective of promising future renewable energy carriers (Melis et al., 2000; Kruse et al., 2005; Ghirardi et al., 2009), the physiological role of such an oxygen-sensitive enzyme linked to the photosynthetic pathway has been poorly considered. The 40-year-old proposal that H2 evolution by hydrogenase is involved in induction of photosynthetic electron transfer after anoxic incubation (Kessler, 1973; Schreiber and Vidaver, 1974) has been only recently demonstrated in C. reinhardtii. Gas exchange measurements showed that H2 evolution occurs prior to CO2 fixation upon illumination (Cournac et al., 2002). At light onset after a prolonged period in dark anoxic conditions, the photosynthetic electron flow is mainly a LEF toward hydrogenase (Godaux et al., 2013), and lack of hydrogenase activity in hydrogenase maturation factor EF (hydEF) mutant strain deficient in hydrogenases maturation (Posewitz et al., 2004) induces a lag in induction of PSII activity (Ghysels et al., 2013). In cyanobacteria, the bidirectional Ni-Fe hydrogenase might also work as an electron valve for disposal of electrons generated at the onset of illumination of cells (Cournac et al., 2004) or when excess electrons are generated during photosynthesis, preventing the slowing of the electron transport chain under stress conditions (Appel et al., 2000; Carrieri et al., 2011). The bidirectional Ni-Fe hydrogenase could also dispose of excess of reducing equivalents during fermentation in dark anaerobic conditions, helping to generate ATP and maintaining homeostasis (Barz et al., 2010). A similar role for hydrogenase in setting the redox poise in the chloroplast of C. reinhardtii in anoxia has been recently uncovered (Clowez et al., 2015).

Still, the physiological and evolutionary advantages of hydrogenase activity have not been demonstrated so far, and the mechanism responsible for the cessation of hydrogen evolution remains unclear. In this respect, at least three hypotheses have been formulated: (1) the inhibition of hydrogenase by O2 produced by water photolysis (Ghirardi et al., 1997; Cohen et al., 2005), (2) the competition between ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase (FNR) and hydrogenase activity for reduced FDX (Yacoby et al., 2011), and (3) the inhibition of electron supply to hydrogenases by the proton gradient generated by another AEF, the cyclic electron flow around PSI (PSI-CEF; Tolleter et al., 2011). First described by Arnon (1955), PSI-CEF consists in a reinjection of electrons from reduced FDX or NADPH pool in the plastoquinone (PQ) pool. By generating an additional transthylakoidal proton gradient without producing reducing power, this AEF thus contributes to adjust the ATP/NADPH ratio for carbon fixation in various energetic unfavorable conditions including anoxia (Tolleter et al., 2011; Alric, 2014), high light (Tolleter et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2014), or low CO2 (Lucker and Kramer, 2013). In C. reinhardtii, two pathways have been suggested to be involved in PSI-CEF: (1) a type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (NDA2; Jans et al., 2008) driving the electrons from NAD(P)H to the PQ pool and (2) a pathway involving Proton Gradient Regulation (PGR) proteins where electrons from reduced FDXs return to the PQ pool or cytochrome b6f. Not fully understood, this latter pathway comprises at least Proton Gradient Regulation5 (PGR5) and Proton-Gradient Regulation-Like1 (PGRL1) proteins (Iwai et al., 2010; Tolleter et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2014) and is the major route for PSI-CEF in C. reinhardtii cells placed in anoxia (Alric, 2014).

In this work, we took advantage of specific C. reinhardtii mutants defective in hydrogenase activity and PSI-CEF to study photosynthetic electron transfer after a period of dark anoxic conditions. Based on biophysical and physiological complementary studies, we demonstrate that at least hydrogenase activity or PSI-CEF is compulsory for the activity of the CBB cycle and for the survival of the cells submitted to anoxic conditions in their natural habitat.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In Anoxia, Induction of PSII Electron Flow Requires at Least Hydrogenase Activity or PSI-Cyclic Electron Flow

To explore the interplay between hydrogenase activity, PSI-CEF, and CBB cycle activity in C. reinhardtii in anoxia, we resorted to pgrl1 mating type minus (mt−) nuclear mutant defective in PSI-CEF (Tolleter et al., 2011) and hydrogenase maturation factor G-2 (hydg-2) mating type plus (mt+) nuclear mutant deprived of hydrogenase activity due to the lack of HYDG maturation factor (Godaux et al., 2013). We also isolated double mutants impaired in both AEF by crossing the pgrl1 and hydg-2 single mutants (Supplemental Fig. S1). Results will be shown for one meiotic product (B1-21), named, by convenience, pgrl1 hydg-2 in this report, but every double mutant meiotic product had the same behavior (Supplemental Fig. S1). Similarly, both wild-type strains from which derived the single mutants have been compared for each parameter assessed in this work and did not show any difference (Tables I and II). Data presented refer to the parental wild-type strain of hydg-2 mutant.

Table I. Growth rate, photosynthetic features, and starch content in oxic conditions.

Growth rate in mixotrophic conditions (TAP, acetate, and continuous light). A ϕPSII of 0.5 corresponds to an ETRPSII of approximately 100 e– s–1 PSII–1. The ratio between active PSI and PSII centers was estimated as described in Cardol et al. (2009; for further information, see “Materials and Methods”). All measurements were performed at 250 µmol photons m–2 s–1 at least in triplicate (n ≥ 3), and data are presented as means ± sd. Wild-type 1′ derives from 137c reference wild-type strain and is the parental strain of hydg-2 (Godaux et al., 2013). Wild-type 137c is the parental strain of pgrl1 (Tolleter et al., 2011).

| Strain | Growth Rate | ϕPSII | ETRPSII | PSI/PSII | Starch Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d−1 | e– s–1 PSII–1 | pg cell–1 | |||

| Wild-type (1′) | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 100 ± 4 | 1.35 ± 0.23 | 0.68 ± 0.19 |

| Wild-type (137C) | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 102 ± 4 | 1.21 ± 0.18 | 1.95 ± 0.68 |

| pgrl1 | 0.58 ± 0.08 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 98 ± 6 | 1.16 ± 0.29 | 1.87 ± 0.65 |

| hyg-2 | 0.50 ± 0.07 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 100 ± 3 | 1.33 ± 0.21 | 0.59 ± 0.10 |

| pgrl1 hydg-2 | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 102 ± 4 | 1.11 ± 0.15 | 1.99 ± 0.22 |

Table II. Photosynthetic parameters upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light (10 s).

All measurements were performed at 250 µmol photons m–2 s–1 at least in triplicate (n ≥ 3), and data are presented as means ± sd. Wild-type 1′ derives from 137c reference wild-type strain and is the parental strain of hydg-2 (Godaux et al., 2013). Wild-type 137c is the parental strain of pgrl1 (Tolleter et al., 2011). The pgrl1::PGRL1 strain is the complemented strain of pgrl1 (Tolleter et al., 2011). n.d., Not determined.

| Strain | JH2 | Rph | ϕPSII | ϕPSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| e– s–1 PSI–1 | e− s−1 PS−1 | |||

| Wild-type (1′) | 19.8 ± 4.4 | 18.9 ± 8.1 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.04 |

| Wild-type (137C) | 18.1 ± 6.2 | 19.2 ± 5.6 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.06 |

| pgrl1 | 17.0 ± 7.1 | 17.4 ± 3.6 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.07 |

| hyg-2 | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 3.8 ± 2.4 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.02 |

| pgrl1 hydg-2 | 0.9 ± 2.5 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.03 |

| pgrl1::PGRL1 | 21.3 ± 6.5 | n.d. | 0.13 ± 0.04 | n.d. |

Induction of photosynthetic electron transfer in the wild type and the three mutant strains (pgrl1, hydg-2, and pgrl1 hydg-2) was investigated. We choose a near-saturating light intensity (250 µmol photons m–2 s–1) corresponding to approximately 100 electrons (e−) s–1 PSII–1 in oxic conditions (Table I), as an exciting light intensity. In this range of light intensities, growth and photosynthesis of aerated cultures were similar for all the strains (Table I). After 1 h of acclimation to dark and anoxia, a time required for proper expression and activity of hydrogenases (Forestier et al., 2003; Godaux et al., 2013; Supplemental Fig. S2), we measured the hydrogen evolution rate (JH2) and the quantum yield of PSII (ϕPSII) and PSI (ϕPSI), as well as the mean photochemical rate (Rph) based on electrochromic shift (ECS) measurements at the onset of light (10 s; Table II). In the two wild-type strains, in the pgrl1 mutant and in the pgrl1::PGRL1 complemented strain, Rph was about 20 e– s–1 PS–1 and JH2 was about 20 e– s–1 PSI–1, which represents about 40% of the maximal capacity measured for hydrogenase (Godaux et al., 2013). In the wild type, 20 e– s–1 PSI–1 corresponds to an H2 production rate of 0.58 µmol H2 mg chlorophyll–1 min–1, which is compatible with recent published values of approximately 0.25 to 0.36 µmol H2 mg chlorophyll–1 min–1 (Tolleter et al., 2011; Clowez et al., 2015). On the contrary, in the two mutants lacking hydrogenase activity (hydg-2 and pgrl1 hydg-2), neither hydrogen production, nor significant photosynthetic activity, was detected after 10 s of illumination (Table II). The lack of PSII-driven electron flow in hydrogenase mutants (hydg-2 and pgrl1 hydg-2) and the similar activities in the wild type and pgrl1 indicate that, in this time range, the activities of PSI and PSII are mainly dependent on the presence of the hydrogenases, in agreement with our previous results (Godaux et al., 2013). By acting as an electron safety valve, hydrogenases thus allow a LEF from PSII and PSI and sustain the generation of an electrochemical proton gradient for subsequent ATP synthesis.

Accordingly, we assumed that the values of ϕPSII and ϕPSI after 10 s of illumination correspond to 20 e– s–1 PS–1 and used these values as a ruler to calculate the electron transfer rates (ETRs) through PSI (ETRPSI in e– s–1 PSI–1) and PSII (ETRPSII in e– s–1 PSII–1) for longer times (for further details, see “Materials and Methods”).

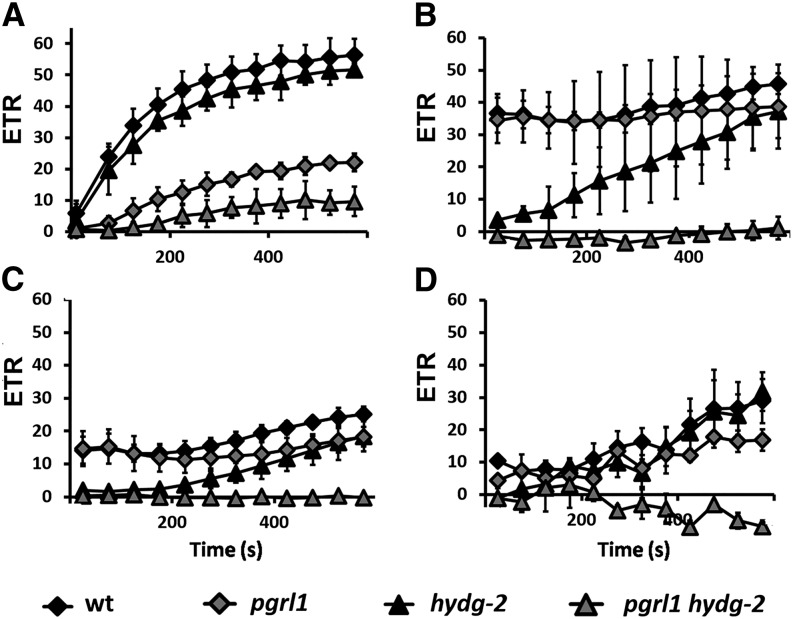

When the wild type was illuminated for a longer time, the hydrogen production dropped to 0 after about 200 s, followed by an increase of ETRPSII (Fig. 1A). In the hydg-2 strain, JH2 and ETRPSII were below detection during the first 2 min of illumination (Fig. 1C), as previously reported (Ghysels et al., 2013; Godaux et al., 2013), but ETRPSII increased later. In the pgrl1 mutant, JH2 decreased very slowly, in agreement with previous observations (Tolleter et al., 2011), together with a slow increase of ETRPSII (Fig. 1B). Thus, after 10 min of illumination, photosynthetic activity partially recovered in the wild type and single mutants. By contrast, ETRPSII in pgrl1 hydg-2 double mutants remained null for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 1D; Supplemental Fig. S3).

Figure 1.

Activities of PSII, hydrogenases, and CBB cycle upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light (250 µmol photons m–2 s–1) in the wild type (wt; A), pgrl1 (B), hydg-2 (C), and pgrl1 hydg-2 (D). Dark circles indicate ETRPSII (e– s–1 PSII–1); gray squares indicate JH2 (e– s–1 PSI–1); and a white triangle indicates electron flow toward carbon fixation (JCO2, e– s–1 PSI–1), calculated as follows: JCO2 = ETRPSII – JH2. See text for further information. All measurements were performed at least in triplicate (n ≥ 3), and data are presented as means ± sd.

Such an increase of ETRPSII is usually ascribed to the activation of the CBB cycle (Cournac et al., 2002). However, some electrons originated from PSII might also be rerouted toward O2 reduction (PSI-Mehler reaction, mitochondrial respiration, etc.). To test these possibilities, we added, prior to illumination, 2-hydroxyacetaldehyde (glycolaldehyde), an effective inhibitor of phosphoribulokinase (Sicher, 1984), or carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), an uncoupler of membrane potential preventing ATP synthesis in mitochondria and chloroplasts. In the presence of these inhibitors, both JH2 and ETRPSII remained stable in the wild type as well as in single mutants for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 2). These results confirm that (1) the hydrogenase is the main electron sink for PSII-originated electrons when CBB cycle is inactive, (2) the increase of ETRPSII corresponds to the redirection of the LEF to CBB cycle activity at the expense of hydrogenase activity, and (3) this increase depends on the presence of an electrochemical proton gradient for ATP synthesis.

Figure 2.

Activities of PSII, hydrogenases, and CBB cycle upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light (250 µmol photons m–2 s–1) in the wild type (wt; A and B), hydg-2 (C and D), and pgrl1 (E and F) in conditions of inhibition of the CBB cycle. Glycolaldehyde (10 mm; A, C, and E) or CCCP (20 µm; B, D, and F) were added prior to illumination. Dark circles indicate ETRPSII (e– s–1 PSII–1); gray squares indicate JH2 (e– s–1 PSI–1); and a white triangle indicates electron flow toward carbon fixation (JCO2, e– s–1 PSI–1), calculated as follows JCO2 = ETRPSII – JH2. See text for further information. All measurements were performed at least in triplicate (n ≥ 3), and data are presented as means ± sd.

As a consequence, we can reasonably assume that the divergence between JH2 and ETRPSII is mainly indicative of an electron flux toward the CBB cycle (i.e. CO2 fixation through NADP+ reduction [JCO2] in e– s–1 PSI–1). More formally, ETRPSII is the sum of only two components: (1) ETRPSII toward H2 evolution (JH2) and (2) ETRPSII toward CO2 fixation (JCO2). Thus JCO2 = ETRPSII – JH2 (Figs. 1 and 2). Such an indirect calculation of JCO2 is correct only if the PSI to PSII ratio is 1, which is not the case for all strains (Table I). In an attempt to simplify calculations, we assumed in the following that PSI/PSII stoichiometry is 1. This indicates that in the wild type and single mutants, electrons from PSII are progressively routed toward CO2 fixation (Fig. 1).

We also performed calculations taking into account PSI/PSII stoichiometry measured in Table I. For wild-type 1′, which has the largest PSI-to-PSII ratio (approximately 1.3), photosynthetic electron flows are modified at most by 15% (for further information, see “Materials and Methods”).

Transitory Induction of PGRL1-Dependent PSI-CEF upon Illumination in Anoxia

As indicated by the previous results, the presence of PGRL1 is necessary for the reactivation of the CBB cycle in the absence of hydrogenase activity. It is generally acknowledged that the PGRL1 protein participates to PSI-CEF both in C. reinhardtii and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; DalCorso et al., 2008; Iwai et al., 2010; Tolleter et al., 2011; Hertle et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2014). By generating an additional proton motive force, PSI-CEF is proposed to enhance ATP synthesis in the illuminated chloroplast (Allen, 2003) and/or to trigger photoprotection of the photosynthetic apparatus (Joliot and Johnson, 2011; Tikkanen et al., 2012). Occurrence of PSI-CEF has been a matter of debate during the last decade, mainly because most experiments have been performed in nonphysiological conditions (e.g. in the presence of PSII inhibitor 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea [DCMU]; Johnson, 2011; Leister and Shikanai, 2013). Two strategies are commonly accepted to provide physiological evidence for PSI-CEF activity: (1) comparing ETRPSII and ETRPSI (Harbinson et al., 1990) and (2) comparing ETRPSII and mean Rph based on ECS measurement (Joliot and Joliot, 2002). In case of a pure LEF, all enzyme complexes are expected to operate at the same rate. Rph, ETRPSI, and ETRPSII should thus be equal in the absence of PSI-CEF and should follow the same temporal dependence. This is clearly the case in the pgrl1 and pgrl1 hydg-2 mutants (Fig. 3, B, D, F, and H). On the contrary, an increase of Rph and ETRPSI (ETRPSII remaining constant) reflected the onset of PSI-CEF in the wild type and hydg-2 mutant within the first 200 s of illumination (Fig. 3, A, C, E, and G). To quantify the contribution of PSI-CEF (PSI cyclic electron flow [JCEF], in e– s–1 PSI–1) to photosynthesis reactivation, we considered that the PSI ETR is the sum of two components: ETRPSI = ETRPSII + JCEF. Thus, JCEF = ETRPSI – ETRPSII (Fig. 3, A–D). Given that ETRPSI (e– s–1 PSI–1) + ETRPSII (e– s–1 PSII–1) = 2Rph (e– s–1 PS–1), which we confirmed experimentally (Supplemental Fig. S4), we can also write that JCEF = 2(Rph – ETRPSII; Fig. 3, E–H). Again, those equations are valid if the PSI-to-PSII ratio is 1 (for further information, see above and “Materials and Methods”). These two methods gave very similar estimations of PSI-CEF (Fig. 3): JCEF is null in the pgrl1 and pgrl1 hydg-2 mutants, whereas it increases during the first 200 s of illumination in the wild type and hydg-2 mutant before almost disappearing after approximately 5 to 6 min.

Figure 3.

JCEF upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light in the wild type (wt; A and E), pgrl1 (B and F), hydg-2 (C and G), and pgrl1 hydg-2 (D and H). Dark circles (A–H) indicate ETRPSII (e– s–1 PSII–1); white circles (A–D) indicate ETRPSI (e– s–1 PSI–1); gray circles (E–H) indicate Rph (e– s–1 PS–1); gray diamonds (A–D) indicate JCEF (e– s–1 PSI–1), calculated as follows: JCEF = ETRPSI – ETRPSII; and gray diamonds (E–H) indicate JCEF (e– s–1 PSI–1), calculated as follows: JCEF = 2(Rph – ETRPSII). See text for further information. All measurements were performed at least in triplicate (n ≥ 3), and data are presented as means ± sd.

To our knowledge, these are the first measurements of PSI-CEF rate in physiological conditions (i.e. in the absence of inhibitors) in C. reinhardtii. The maximal rate for PSI-CEF achieved in the wild type and hydg-2 was 20 e– s–1 PSI–1, a rate corresponding to one-half the capacity of PGRL1-dependent PSI-CEF previously measured in high light in the presence of DCMU (Alric, 2014). PSI-CEF is induced in our conditions when LEF toward the CBB cycle is still impaired due to a lack of ATP. When PSI-CEF reaches its maximal value after approximately 120 s of illumination (Fig. 3), the PSI-CEF-to-LEF ratio (i.e. JCEF-to-ETRPSII ratio) is about 1.3 and 3.5 in the wild type and hydg-2, respectively. Similarly, the PSI-CEF-to-LEF ratio also increased (up to 4-fold increase) when the CBB cycle is impaired due to carbon limitation in oxic conditions (Lucker and Kramer, 2013). These finding are in good agreement with the proposal that PSI-CEF contributes to adjust the ATP-to-NADPH ratio for photosynthetic carbon fixation in various energetic unfavorable conditions (Allen, 2003).

In anoxia, both PQ and PSI acceptor pools are almost fully reduced (Bennoun, 1982; Ghysels et al., 2013; Godaux et al., 2013; Takahashi et al., 2013), which might hamper the putative limiting step of PSI-CEF electron transfer (i.e. NADPH to PQ; Alric, 2014), as well as the PSI electron transfer due to acceptor side limitation (Takahashi et al., 2013). It is tempting to propose that hydrogenase activity, by partially reoxidizing the PQ pool and FDX, might directly contribute to set the redox poise, allowing the PSI-CEF to operate. However, the fact that PSI-CEF operates at the same rate in the wild type and hydg-2 (Fig. 3) suggests that another factor might be responsible for its activation.

Reduction of the PQ pool also triggers state transitions, a process consisting in the phosphorylation and migration of part of light harvesting complex II (LHCII) from PSII to PSI (for review, see Lemeille and Rochaix, 2010). Because state 2 facilitates induction of PSII activity in the absence of hydrogenase (Ghysels et al., 2013), we propose that the increase of PSI antenna size upon state 2 might enhance PSI-CEF rate (Cardol et al., 2009; Alric, 2010, 2014) and therefore promote ATP synthesis and CBB cycle activity. Nevertheless, the attachment of LHCII to PSI in state 2 has been recently called into question (Nagy et al., 2014; Ünlü et al., 2014). In this respect, the involvement of state transitions could be to decrease PSII-reductive pressure on PQ pool that might impact PSI-CEF rate (see above). In any cases, the transition from state 2 to state 1 did not seem to occur in our range of time as, there was no major change in the maximum PSII fluorescence in the light-adapted state (Fm′) value (Supplemental Fig. S5). Incidentally, our measurements of a transient PSI-CEF under state II provide, to our knowledge, the first in vivo support to the occurrence of PSI-CEF without any direct correlation with state transitions (Takahashi et al., 2013; Alric, 2014).

Sequential and Transient Hydrogenase Activity and PSI-CEF Contribute to Photosynthetic Carbon Fixation

At this point, we can conclude that the CBB cycle is progressively active in the wild type thanks to the sequential occurrence of HYDA-dependent LEF and PGRL1-dependent PSI-CEF. This is further illustrated in a schematic model of electron transfer pathways in the wild type (Fig. 4A). At the onset of illumination, only a hydrogenase-dependent LEF occurs (10 s), followed by the induction of PGRL1-dependent PSI-CEF and later the CBB cycle (120–240 s). When the CBB cycle has been activated by ATP, the NADP+ pool is partially oxidized and FNR, being more efficient in competing for reduced FDX than hydrogenases (see next section; Yacoby et al., 2011), rapidly drives the entire electron flux toward CO2 reduction (more than 360 s). In single mutants, increase in CBB cycle activity is only slightly delayed (Fig. 4, B and C), while lack of both AEF fully prevents photosynthetic electron transfer in pgrl1 hydg-2 double mutant (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Schematic model of photosynthetic electron transfers in C. reinhardtii upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light in the wild type (A), hydg-2 (B), pgrl1 (C), and pgrl1 hydg-2 (D). PSI-CEF (JCEF), JH2, and electron transport rate toward CO2 fixation (JCO2) refer to electron rates (e– s–1 PSI–1) taken from Figures 1 and 3. PC, Plastocyanin; Cyt b6f, cytochrome b6f complex; PQ/PQH2, plastoquinone pool; CF1F0, chloroplastic ATP synthase.

The ETR did not exceed 5 e– s–1 PSI–1 in pgrl1 hydg-2 double mutant and might correspond to an NDA2-driven ETR (Jans et al., 2008; Alric, 2014). The low rate measured here is in good agreement with the rate of 2 e– s–1 PSI–1 measured for PQ reduction by NDA2 (Houille-Vernes et al., 2011) and the rate of 50 to 100 nmol H2 mg chlorophyll–1 min–1 determined for NDA2-driven H2 production from starch degradation (Baltz et al., 2014), the latter value also corresponding to approximately 1 to 2 e– s–1 PSI–1, assuming 500 chlorophyll per photosynthetic unit (Kolber and Falkowski, 1993). Alternatively, this remaining ETR in the double mutant might correspond to the activity of another chloroplastic fermentative pathway linked to FDX reoxidation (Grossman et al., 2011). Regarding these possibilities, we ensured that the starch content of the wild types and mutants before entering anoxia does not differ between mutants and their respective wild type (Table I). Whatever the exact nature of the remaining ETR in pgrl1 hydg-2, these results confirm that at least one of the two AEFs (PSI-CEF or hydrogenase-dependent LEF) is necessary for the proper induction of PSII activity in anoxia.

Because the absence of significant ETR in pgrl1 hydg-2 applies for a given period of incubation in the dark in anoxia (1 h) and for a given light intensity (250 µmol photons m–2 s–1), we explored induction of PSII electron transfer (1) during a longer illumination period (up to 2 h; Supplemental Fig. S6), (2) after shorter (10 min) or longer (16 h) periods of anoxia in the dark (Fig. 5, A and B), and (3) upon lower and higher light intensities (120 and 1,000 µmol photons m–2 s–1, respectively; Fig. 5, C and D). In every condition, photosynthetic electron flow of the double mutant remained null or very low compared with the wild-type and single mutant strains. The only exception to this rule is the low ETR in pgrl1 after 10 min of anoxia (Fig. 5A), which is probably due to the fact that the hydrogenases are not yet fully expressed (Forestier et al., 2003; Pape et al., 2012), and therefore mimics the behavior of pgrl1 hydg-2.

Figure 5.

ETRPSII (e– s–1 PSII–1) in the wild type (wt), pgrl1, hydg-2, and pgrl1 hydg-2 upon a shift from dark anoxia (10 min) to light (250 µmol photons m–2 s–1; A), upon a shift from dark anoxia (16 h) to light (250 µmol photons m–2 s–1; B), upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light (120 µmol photons m–2 s–1; C), and upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light (1,000 µmol photons m–2 s–1; D). All measurements were performed at least in triplicate (n ≥ 3), and data are presented as means ± sd.

Competition between FNR and HYDA Contributes to the Observed Decrease in Hydrogen Evolution Rate

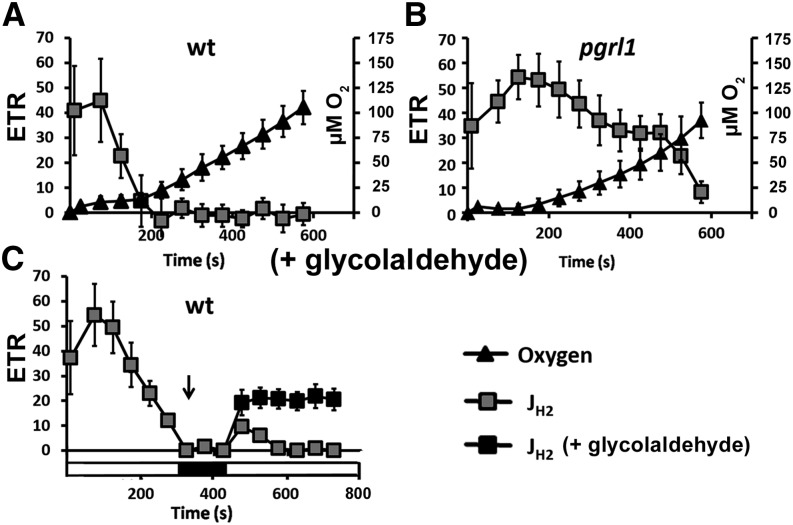

O2 sensitivity of algal hydrogenases is defined as the major challenge to achieve a sustained hydrogen photoproduction. Hydrogenases are described as irreversibly inactivated after exposure to O2, the C. reinhardtii enzyme being the most O2 sensitive among them (Ghirardi et al., 1997; Cohen et al., 2005). In the PGRL1-deficient mutant or in the presence of glycolaldehyde or CCCP (i.e. in the absence of CO2 fixation), we observed, however, a sustained JH2 lasting for at least 10 min after transfer to light (Figs. 1B and 2, A, B, E, and F), and coexisting with a significant PSII activity and thus a sustained production of oxygen by water splitting. A possible explanation for this long-lasting hydrogen production is that we used, in these experiments, Glc and Glc oxidase, which efficiently reduces oxygen evolved by PSII and diffusing to the extracellular medium. We thus performed a similar experiment as presented in Figure 1 for the wild type and pgrl1 mutant cells where anoxia was reached by bubbling nitrogen for 5 min and cells were then acclimated to dark and anoxia for 1 h. In the wild type, hydrogen evolution stops, while the level of dissolved oxygen is still low in the medium (approximately 10 µm; Fig. 6A). Conversely, in pgrl1, a sustained hydrogen evolution occurs in the presence of much higher concentrations of dissolved oxygen (up to approximately 80 µm; Fig. 6B). This leads us to suggest that in vivo oxygen sensitivity of hydrogenase activity is not the only factor that accounts for the decrease of JH2 in the light in the wild type. It was proposed earlier that the slow down of the hydrogenase activity in wild-type cells stems from a thermodynamic break (Tolleter et al., 2011). In this view, the PSI-CEF would generate an extra proton gradient that would slow down the cytochrome b6f and therefore decrease the electron supply from PSII to the hydrogenase. This seems very unlikely because PSII activity (ETRPSII) and photosynthetic carbon fixation (JCO2) tends to increase while hydrogen activity (JH2) decreases (Fig. 1). In addition, H2 evolution rate is about the same in presence of either a proton gradient uncoupler (CCCP) or a CBB cycle inhibitor (glycolaldehyde; Fig. 2), whose presence should decrease and increase the amplitude of the proton gradient, respectively. In this respect, it was recently shown that NADPH reduction by FNR prevents an efficient H2 production by HYDA in vitro (Yacoby et al., 2011). This might be due to the low affinity of HYDA for FDX (Km = 35 µm; Happe and Naber, 1993), close to two orders of magnitude lower than the affinity of FNR for FDX (Km = 0.4 µm; Jacquot et al., 1997). To test whether competition between FNR and HYDA might contribute to a decrease in JH2 in vivo in the wild type, we tested the effect of the addition of glycolaldehyde (inhibitor of CBB cycle) on wild-type cells when JH2 was null (i.e. after a few minutes of illumination). If hydrogenase was irreversibly inactivated by oxygen, JH2 should remain null whatever the inhibition of CBB cycle activity. Yet, upon addition of glycolaldehyde, JH2 again increases, while it remains null in the absence of glycolaldehyde (Fig. 6C). We thus propose that the competition between HYDA and FNR for reduced FDX is an important factor responsible for the switch in electron transfer from hydrogenase activity (JH2) toward CBB cycle activity (JCO2; Fig. 1). In agreement with this, transformants displaying a reduced photosynthesis-to-respiration ratio reach anoxia in the light and express hydrogenase but evolve only a small amount of H2 in vivo unless the Calvin cycle is inhibited (Rühle et al., 2008).

Figure 6.

In vivo hydrogenase activity. A and B, Concomitant measurements of JH2 (e– s–1 PSI–1; gray squares) and dissolved oxygen concentration (µm O2, dark triangles) in the wild type (wt; A) and pgrl1 (B) upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light. Anoxia was reached by bubbling with nitrogen for 5 min prior to incubation in the dark for 1 h. C, JH2 (e– s–1 PSI–1) upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light. The arrow indicates when glycolaldehyde (10 mm, dark squares) was added to inhibit CBB cycle activity. After 2 min of incubation in the dark, light is switched on for at least an extra 6 min. All measurements were performed at least in triplicate (n ≥ 3), and data are presented as means ± sd.

PSII activity, in addition to supplying hydrogenases and CBB cycle activity in electrons, produces oxygen by water splitting. Various oxidases, such as the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase, might contribute to cellular ATP synthesis and, in turn, to CBB cycle activity by using oxygen as an electron acceptor (Lavergne, 1989). In this respect, recent works have highlighted the dependence of PSI-CEF-deficient mutants upon oxygen in C. reinhardtii and Arabidopsis through an increase of mitochondrial respiration and PSI-Mehler reaction (Yoshida et al., 2011; Dang et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2014). Regarding the contribution of respiration to induction of photosynthetic electron flow in anoxia, the addition of myxothiazol, an efficient inhibitor of mitochondrial respiratory chain cytochrome bc1 complex (complex III), prior to illumination (Supplemental Fig. S7) has no effect. As shown in Figure 2A, the addition of glycolaldehyde fully prevents the increase of photosynthetic electron flow, which is almost exclusively driven under these conditions by hydrogenase. This indicates that, if occurring, other alternative processes (e.g. Mehler reaction, or mitochondrial respiration) operate at a very low rate.

Concomitant Absence of Hydrogenase Activity and PGRL1-Dependent PSI-CEF Is Detrimental for Cell Survival

Photosynthesis relies on a large set of alternative electron transfer pathways allowing the cells to face various changes of environmental conditions. Deficiency in some pathways can be successfully compensated by other pathways (Cardol et al., 2009; Dang et al., 2014). To check whether the lack of hydrogenase activity and/or PSI-CEF has an impact on the growth of C. reinhardtii in anoxia, the four strains were grown individually and submitted to 3-h-dark/3-h-light cycles in sealed cuvettes. This time scale was chosen (1) to ensure that anoxia is reached during the dark cycle so that hydrogenase is expressed in the wild type and in pgrl1 and (2) to maximize the impact of mutations that impair photosynthesis reactivation steps. The doubling time of pgrl1 hydg-2 cells in anoxia was much lower compared with wild-type and single mutant cells (Fig. 7A). In a second experiment, wild-type and pgrl1 hydg-2 double mutant cells were mixed in equal proportion and submitted to the same growth test. The ratio between pgrl1 hydg-2 mutant and wild-type cells progressively decreased, and only wild-type cells were recovered after 7 d of growth in sealed cuvettes under anoxic conditions (Fig. 7B). PGRL1-dependent PSI-CEF has been proposed to be crucial for acclimation and survival in anoxic conditions under a constant light regime, both in Physcomitrella patens and C. reinhardtii (Kukuczka et al., 2014). In our experimental conditions, growth of pgrl1 mutant was not impaired (Fig. 7A) and Calvin cycle reactivation was only slightly delayed (Figs. 1B and 4C). We attribute this phenotype to hydrogenase activity that could play in anoxia the same role as the Mehler reaction in the presence of oxygen. Simultaneous absence of hydrogenase activity and PGRL1-dependent PSI-CEF, however, fully prevents the induction of photosynthetic electron flow (Figs. 1D and 4D) and, in turn, growth (Fig. 7). Our results thus highlight the importance for C. reinhardtii of maintaining at least hydrogenase activity or PSI-CEF to survive in its natural habitat, where it frequently encounters oxygen limitation.

Figure 7.

Growth in anoxic conditions. A, Specific growth rate (µ, d–1) of the wild type (wt) and mutants in 3-h-dark/3-h-light cycles in TMP liquid medium. B, Proportion of pgrl1 hydg-2 mutant within a coculture of pgrl1 hydg-2 and wild-type cells in a 3-h-dark/3-h-light cycle in TAP liquid medium (for further details, see “Materials and Methods”). Dark squares indicate an aerated culture, and gray squares indicate an anoxic sealed details in triplicate (n ≥ 3), and data are presented as means ± sd.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii wild-type strain (1′ in our stock collection) derives from the 137c reference wild-type strain. The hydg-2 mutant lacking the HYDG maturation factor and deficient for hydrogenase activity (HYDA enzyme) was obtained in our laboratory from insertional mutagenesis carried out on the 1′ strain (Godaux et al., 2013). An allelic hydg-3 mutant strain was also tested and displayed the same features (data not shown). The pgrl1 mutant defective in PSI-CEF was generated by insertional mutagenesis carried out on 137c (Tolleter et al., 2011). The wild-type strain from which derived the single pgrl1 mutant and the complemented strain for PGRL1 (Tolleter et al., 2011) did not differ from the wild-type 1′ strain (Tables I and II). The double mutant pgrl1 hydg-2 was obtained by crossing the pgrl1 mt– mutant with the hydg-2 mt+ mutant (for details, see Supplemental Fig. S1).

Strains were routinely grown in Tris-acetate phosphate (TAP) or eventually on Tris-minimal phosphate (TMP) medium at 25°C under continuous light of 50 µmol photons m–2 s–1 either on solid (1.5% [w/v] agar) or in liquid medium. For experimentation, cells were harvested (3,000g for 2 min) during exponential growth phase (2–4.106 cells mL–1) and resuspended in fresh TAP medium at a concentration of 10 µg chlorophyll mL–1. Ten percent (w/v) Ficoll was added to prevent cell sedimentation during spectroscopic analysis.

Chlorophyll and Starch Contents

For the determination of chlorophyll concentration, pigments were extracted from whole cells in 90% (v/v) methanol, and debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000g. Chlorophyll a plus b concentration was determined with a λ 20 spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer). Starch was extracted according to Ral et al. (2006). Starch amounts were determined spectrophotometrically using the Starch Kit (Roche, R-Biopharm).

Biophysical Analyses

In all experiments, cells were acclimated to dark and anoxia for 1 h before transfer to light. Unless otherwise stated, anoxic condition was reached by sealing cell suspension in spectrophotometric cuvettes in the presence of catalase (1,000 units mL–1), Glc (10 mm), and Glc oxidase (2 mg mL–1).

In vivo chlorophyll fluorescence measurements were performed at room temperature on cell liquid suspensions using a JTS-10 spectrophotometer (Biologic). In most experiments, an actinic light of 250 µmol photons m–2 s–1 was provided by a 640-nm LED light source. This light intensity corresponds to approximately 100 e– s–1 PSII–1 in oxic conditions (Table I). The effective photochemical yield of PSII (ϕPSII) was calculated as (Fm′ – Fs)/Fm′, where FS is the actual fluorescence level excited by actinic light, and Fm′ is the maximum fluorescence emission level induced by a 150-ms superimposed pulse of saturating light (3,500 µmol photons m–2 s–1).

PSI primary donor (P700) absorption changes were assessed with a probing light peaking at 705 nm. Actinic light of 250 µmol photons m–2 s–1 was provided by a 640-nm LED light source, which was switched off very briefly while measuring light transmission at 705 nm. To remove unspecific contributions to the signal at 705 nm, absorption changes measured at 740 nm were subtracted. The quantum yield of photochemical energy conversion by PSI (ϕPSI) was calculated as (Pm′ – Ps)/(Pm – P0; Klughammer and Schreiber, 2008), where P0 is the absorption level when P700 is fully reduced, Pm is the absorption level when P700 is fully oxidized in the presence of 20 µm DCMU and 5 mm 2,5-dibromo-6-isopropyl-3-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone (to prevent P700 rereduction by cytochrome b6f complex activity) upon saturating continuous illumination, Ps is the absorbance level under continuous illumination, and Pm′ is the maximal absorption level reached during a 200-ms saturating light pulse (3,500 µmol photons m–2 s–1) on top of the actinic light. P700 concentration was estimated by using the Pm value (ε705 nm for P700 = 105 mm–1 cm–1; Witt et al., 2003).

ECS Analyses

The generation of an electrochemical proton gradient induces a shift in the absorption spectra of some photosynthetic pigments, resulting in the so-called electrochromic shift. The use of the ECS signal to study photosynthetic apparatus and a detailed description of the different application are reviewed in Bailleul et al. (2010). The relaxation kinetics of the carotenoid electrochromic band shift was measured at 520 nm and corrected by subtracting the signal at 546 nm. Rphs were measured by following the relaxation of the ECS during the first 2 ms after switching off the actinic light (Joliot and Joliot, 2002). Results were expressed as e– s–1 PS–1 upon normalization to the amplitude of ECS signal upon excitation with a saturating flash (5-ns laser pulse) that leads to one single charge separation per PS (Bailleul et al., 2010).

In this report, we calculated photosynthetic electron flows assuming that PSI/PSII stoichiometry is about 1 in all our strains. Doing so, we attempted to simplify calculations and make the study accessible for nonspecialists. The ratio between active PSI and PSII centers was, however, estimated as described in Cardol et al. (2009). Briefly, the amplitude of the fast phase (1 ms) of the ECS signal (at 520–546 nm) was monitored upon excitation with a laser flash. The contribution of PSII was calculated from the decrease in the ECS amplitude after the flash upon the addition of the PSII inhibitors DCMU (20 µm) and hydroxylamine (1 mm), whereas the contribution of PSI corresponded to the amplitude of the ECS that was insensitive to these inhibitors.

The calculation of ETRPSI and ETRPSII usually also requires the quantification of the absorption cross sections of PSII and PSI, which can change with time through the process of state transitions (Wollman and Delepelaire, 1984; Alric, 2014). However, we could show that the PSII cross sections did not change in our conditions by monitoring Fm′ (Supplemental Fig. S5). Moreover, only a hydrogenase-dependent LEF occurs at the onset of light, which allowed us to use the Rphs measured by ECS, fluorescence, and P700 at the initial onset of light as a ruler to determine ETRPSI and ETRPSII based on the sole PS quantum yield measurements. At the onset of light, ϕPSII = 0.12 and ϕPSI = 0.21 (Table II). With the hypothesis that PSI/PSII is 1, this leads to ETRPSII (t = 0) = ϕPSII × I × σPSII = 20 e– s−–1 PSII–1 and to ETRPSI (t = 0) = ϕPSI × I × σPSI = 20 e– s–1 PSI–1, where t is time, I is the actinic light intensity, σPSI is the absorption cross section of PSI, and σPSII is the absorption cross section of PSII. We therefore calculated ETRPSII (e– s–1 PSII–1) as (20/0.12) × ϕPSII and ETRPSI (e– s–1 PSI–1) as (20/0.21) × ϕPSI. From these values of ETRPSI and ETRPSII, we calculated JCO2 and JCEF (both in e− s−1 PSI−1) with the same hypothesis that PSI/PSII is 1: JCO2 = ETRPSI I − JH2, and JCEF = ETRPSI − ETRPSII = 2(Rph − ETRPSII). If the ratio between PSI and PSII centers (b) is different from 1, this would lead to JCO2 = (1 + b)/2b × ETRPSII − JH2, and JCEF = (1 + b)/2b × (ETRPSI − ETRPSII) = (1 + b)/b × (Rph − ETRPSII). For wild-type 1’, which has the largest PSI/PSII ratio (b ∼ 1.35; Table 1), photosynthetic electron flows are modified by less than 20%.

Oxygen and hydrogen exchange rates were measured at 25°C using an oxygen-sensitive Clark electrode (Oxygraph, Hansatech Instruments), eventually modified to only detect hydrogen (Oxy-Ecu, Hansatech Instruments). Actinic light was provided by a homemade light system composed of white and green LEDs. Oxygen solubility in water is about 258 µm at 25°C. For hydrogen evolution measurements (nmol H2 µg chlorophyll–1 s–1), the entire setup was placed in a plastic tent under anoxic atmosphere (N2) to avoid contamination of anoxic samples by oxygen while filling the measuring cell. JH2s were calculated on the basis of the first derivative of hydrogen production curves (data not shown) and expressed in e– s–1 PSI–1 according to the following calculation: (nmol H2 µg chlorophyll–1 s–1) · 2 · (µg chlorophyll · pmol P700), assuming 2 e– per H2 evolved.

Growth Experiments

Doubling time at 250 µmol photons m–2 s–1 in TMP medium was determined from Absorbance at 750 nm, cell number, and chlorophyll content (initial cell density of 2.105–106 cells mL–1). We did not investigate higher light intensities because the PGRL1-defective strains are high-light sensitive (Tolleter et al., 2011; Dang et al., 2014).

Wild-type and pgrl1 hydg-2 strains were mixed together at equal concentration of 5.105 cells mL–1 in fresh TAP medium. Aliquots of the liquid culture were then collected every 24 h, and about 300 cells were platted on solid TAP media in the light to allow the growth of single-cell colonies. The proportions of each phenotype were analyzed on the basis of peculiar hydrogenase-deficient-related chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics by video imaging according to Godaux et al. (2013). The ratio of pgrl1 hydg-2 was plotted against time.

During growth experiments in anoxia, catalase (1,000 units mL–1), Glc (10 mm), and Glc oxidase (2 mg mL–1) were added at the beginning of the experiment. Glc (10 mm) was subsequently added every 24 h to ensure that Glc oxidase consume oxygen that evolved during the light periods, so that oxygen did not inhibit hydrogenase expression.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Isolation of pgrl1 hydg-2 double mutants by a double chlorophyll fluorescence screen.

Supplemental Figure S2. Chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics of C. reinhardtii pgrl1, hydg-2, and pgrl1 hydg-2 mutants and the wild type after 1 h of dark anoxic conditions.

Supplemental Figure S3. PSII electron transfer rate upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light in four double mutant meiotic products.

Supplemental Figure S4. Relationship between photochemical rate, ETRPSII, and ETRPSI.

Supplemental Figure S5. Fm′ upon a shift from dark anoxia to light.

Supplemental Figure S6. PSII electron transfer rate upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light in pgrl1 hydg-2.

Supplemental Figure S7. Oxygen concentration and PSII ETR upon a shift from dark anoxia (1 h) to light.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank René Matagne for careful reading of the article and help in genetics experiments and Claire Remacle, Fabrice Franck, and Fabrice Rappaport for critical comments during the preparation of this article.

Glossary

- PSI-CEF

cyclic electron flow around PSI

- AEF

alternative electron flow

- LEF

linear electron flow

- FNR

ferredoxin-NADPH oxidoreductase

- CBB

Calvin-Benson-Bassham

- FDX

ferredoxin

- PQ

plastoquinone

- JH2

hydrogen evolution rate

- ϕPSII

quantum yield of PSII

- ϕPSI

quantum yield of PSI

- ECS

electrochromic shift

- Rph

photochemical rate

- ETRPSI

electron transfer rate through PSI

- ETRPSII

electron transfer rate through PSII

- CCCP

cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone

- DCMU

3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea

- JCEF

PSI cyclic electron flow

- Fm′

maximum PSII fluorescence in the light-adapted state

- ETR

electron transfer rate

- TAP

Tris-acetate phosphate

- TMP

Tris-minimal phosphate

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Belgian Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique Fonds pour la Recherche Scientifique du FNRS (grant nos. Fonds de la Recherche Fondamentale Collective 2.4597.11, Crédit de Recherche J.0032.15, and Incentive Grant for Scientific Research F.4520 to P.C.), the University of Liège (grant no. SFRD–11/05 to P.C.), and the Belgian Fonds pour la Formation à la Recherche dans l'Industrie et dans l'Agriculture Fonds pour la Recherche Scientifique du FNRS (to D.G.).

References

- Allen JF. (2003) Cyclic, pseudocyclic and noncyclic photophosphorylation: new links in the chain. Trends Plant Sci 8: 15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alric J. (2010) Cyclic electron flow around photosystem I in unicellular green algae. Photosynth Res 106: 47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alric J. (2014) Redox and ATP control of photosynthetic cyclic electron flow in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. II. Involvement of the PGR5-PGRL1 pathway under anaerobic conditions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1837: 825–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel J, Phunpruch S, Steinmüller K, Schulz R (2000) The bidirectional hydrogenase of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 works as an electron valve during photosynthesis. Arch Microbiol 173: 333–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon DI. (1955) The chloroplast as a complete photosynthetic unit. Science 122: 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailleul B, Cardol P, Breyton C, Finazzi G (2010) Electrochromism: a useful probe to study algal photosynthesis. Photosynth Res 106: 179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltz A, Dang KV, Beyly A, Auroy P, Richaud P, Cournac L, Peltier G (2014) Plastidial expression of type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenase increases the reducing state of plastoquinones and hydrogen photoproduction rate by the indirect pathway in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 165: 1344–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barz M, Beimgraben C, Staller T, Germer F, Opitz F, Marquardt C, Schwarz C, Gutekunst K, Vanselow KH, Schmitz R, et al. (2010) Distribution analysis of hydrogenases in surface waters of marine and freshwater environments. PLoS ONE 5: e13846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennoun P. (1982) Evidence for a respiratory chain in the chloroplast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79: 4352–4356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardol P, Alric J, Girard-Bascou J, Franck F, Wollman FA, Finazzi G (2009) Impaired respiration discloses the physiological significance of state transitions in Chlamydomonas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 15979–15984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardol P, Forti G, Finazzi G (2011) Regulation of electron transport in microalgae. Biochim Biophys Acta 1807: 912–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrieri D, Wawrousek K, Eckert C, Yu J, Maness PC (2011) The role of the bidirectional hydrogenase in cyanobacteria. Bioresour Technol 102: 8368–8377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowez S, Godaux D, Cardol P, Wollman FA, Rappaport F (2015) The involvement of hydrogen-producing and ATP-dependent NADPH-consuming pathways in setting the redox poise in the chloroplast of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in anoxia. J Biol Chem 290: 8666–8676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Kim K, Posewitz M, Ghirardi ML, Schulten K, Seibert M, King P (2005) Molecular dynamics and experimental investigation of H2 and O2 diffusion in [Fe]-hydrogenase. Biochem Soc Trans 33: 80–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cournac L, Guedeney G, Peltier G, Vignais PM (2004) Sustained photoevolution of molecular hydrogen in a mutant of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 deficient in the type I NADPH-dehydrogenase complex. J Bacteriol 186: 1737–1746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cournac L, Mus F, Bernard L, Guedeney G, Vignais PM, Peltier G (2002) Limiting steps of hydrogen production in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Synechocystis PCC 6803 as analysed by light-induced gas exchange transients. Int J Hydrogen Energy 27: 1229–1237 [Google Scholar]

- DalCorso G, Pesaresi P, Masiero S, Aseeva E, Schünemann D, Finazzi G, Joliot P, Barbato R, Leister D (2008) A complex containing PGRL1 and PGR5 is involved in the switch between linear and cyclic electron flow in Arabidopsis. Cell 132: 273–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang KV, Plet J, Tolleter D, Jokel M, Cuiné S, Carrier P, Auroy P, Richaud P, Johnson X, Alric J, et al. (2014) Combined increases in mitochondrial cooperation and oxygen photoreduction compensate for deficiency in cyclic electron flow in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 26: 3036–3050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin L, Tsokoglou A, Happe T (2001) A novel type of iron hydrogenase in the green alga Scenedesmus obliquus is linked to the photosynthetic electron transport chain. J Biol Chem 276: 6125–6132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forestier M, King P, Zhang L, Posewitz M, Schwarzer S, Happe T, Ghirardi ML, Seibert M (2003) Expression of two [Fe]-hydrogenases in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under anaerobic conditions. Eur J Biochem 270: 2750–2758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardi ML, Dubini A, Yu J, Maness PC (2009) Photobiological hydrogen-producing systems. Chem Soc Rev 38: 52–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardi ML, Togasaki RK, Seibert M (1997) Oxygen sensitivity of algal H2 production. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 63-65: 141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghysels B, Godaux D, Matagne RF, Cardol P, Franck F (2013) Function of the chloroplast hydrogenase in the microalga Chlamydomonas: the role of hydrogenase and state transitions during photosynthetic activation in anaerobiosis. PLoS ONE 8: e64161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godaux D, Emonds-Alt B, Berne N, Ghysels B, Alric J, Remacle C, Cardol P (2013) A novel screening method for hydrogenase-deficient mutants in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii based on in vivo chlorophyll fluorescence and photosystem II quantum yield. Int J Hydrogen Energy 38: 1826–1836 [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AR, Catalanotti C, Yang W, Dubini A, Magneschi L, Subramanian V, Posewitz MC, Seibert M (2011) Multiple facets of anoxic metabolism and hydrogen production in the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. New Phytol 190: 279–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happe T, Naber JD (1993) Isolation, characterization and N-terminal amino acid sequence of hydrogenase from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eur J Biochem 214: 475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbinson J, Genty B, Foyer CH (1990) Relationship between photosynthetic electron transport and stromal enzyme activity in pea leaves: toward an understanding of the nature of photosynthetic control. Plant Physiol 94: 545–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertle AP, Blunder T, Wunder T, Pesaresi P, Pribil M, Armbruster U, Leister D (2013) PGRL1 is the elusive ferredoxin-plastoquinone reductase in photosynthetic cyclic electron flow. Mol Cell 49: 511–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houille-Vernes L, Rappaport F, Wollman FA, Alric J, Johnson X (2011) Plastid terminal oxidase 2 (PTOX2) is the major oxidase involved in chlororespiration in Chlamydomonas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 20820–20825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai M, Takizawa K, Tokutsu R, Okamuro A, Takahashi Y, Minagawa J (2010) Isolation of the elusive supercomplex that drives cyclic electron flow in photosynthesis. Nature 464: 1210–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquot JP, Stein M, Suzuki A, Liottet S, Sandoz G, Miginiac-Maslow M (1997) Residue Glu-91 of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii ferredoxin is essential for electron transfer to ferredoxin-thioredoxin reductase. FEBS Lett 400: 293–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans F, Mignolet E, Houyoux PA, Cardol P, Ghysels B, Cuiné S, Cournac L, Peltier G, Remacle C, Franck F (2008) A type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenase mediates light-independent plastoquinone reduction in the chloroplast of Chlamydomonas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 20546–20551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GN. (2011) Reprint of: physiology of PSI cyclic electron transport in higher plants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1807: 906–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson X, Alric J (2012) Interaction between starch breakdown, acetate assimilation, and photosynthetic cyclic electron flow in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Biol Chem 287: 26445–26452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson X, Alric J (2013) Central carbon metabolism and electron transport in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: metabolic constraints for carbon partitioning between oil and starch. Eukaryot Cell 12: 776–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson X, Steinbeck J, Dent RM, Takahashi H, Richaud P, Ozawa S, Houille-Vernes L, Petroutsos D, Rappaport F, Grossman AR, et al. (2014) Proton gradient regulation 5-mediated cyclic electron flow under ATP- or redox-limited conditions: a study of ΔATpase pgr5 and ΔrbcL pgr5 mutants in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 165: 438–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joliot P, Johnson GN (2011) Regulation of cyclic and linear electron flow in higher plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 13317–13322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joliot P, Joliot A (2002) Cyclic electron transfer in plant leaf. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 10209–10214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler E. (1973) Effect of anaerobiosis on photosynthetic reactions and nitrogen metabolism of algae with and without hydrogenase. Arch Mikrobiol 93: 91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klughammer B, Schreiber U (2008) Saturation pulse method for assessment of energy conversion in PSI. PAM application. Notes 1: 11–14 [Google Scholar]

- Kolber Z, Falkowski PG (1993) Use of active fluorescence to estimate phytoplankton photosynthesis in situ. Limnol Oceanogr 38: 1646–1665 [Google Scholar]

- Kruse O, Rupprecht J, Bader KP, Thomas-Hall S, Schenk PM, Finazzi G, Hankamer B (2005) Improved photobiological H2 production in engineered green algal cells. J Biol Chem 280: 34170–34177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukuczka B, Magneschi L, Petroutsos D, Steinbeck J, Bald T, Powikrowska M, Fufezan C, Finazzi G, Hippler M (2014) Proton Gradient Regulation5-Like1-mediated cyclic electron flow is crucial for acclimation to anoxia and complementary to nonphotochemical quenching in stress adaptation. Plant Physiol 165: 1604–1617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavergne J. (1989) Mitochondrial responses to intracellular pulses of photosynthetic oxygen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 8768–8772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leister D, Shikanai T (2013) Complexities and protein complexes in the antimycin A-sensitive pathway of cyclic electron flow in plants. Front Plant Sci 4: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemeille S, Rochaix JD (2010) State transitions at the crossroad of thylakoid signalling pathways. Photosynth Res 106: 33–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucker B, Kramer DM (2013) Regulation of cyclic electron flow in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under fluctuating carbon availability. Photosynth Res 117: 449–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis A, Zhang L, Forestier M, Ghirardi ML, Seibert M (2000) Sustained photobiological hydrogen gas production upon reversible inactivation of oxygen evolution in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 122: 127–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake C. (2010) Alternative electron flows (water-water cycle and cyclic electron flow around PSI) in photosynthesis: molecular mechanisms and physiological functions. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 1951–1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mus F, Dubini A, Seibert M, Posewitz MC, Grossman AR (2007) Anaerobic acclimation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: anoxic gene expression, hydrogenase induction, and metabolic pathways. J Biol Chem 282: 25475–25486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy G, Ünnep R, Zsiros O, Tokutsu R, Takizawa K, Porcar L, Moyet L, Petroutsos D, Garab G, Finazzi G, et al. (2014) Chloroplast remodeling during state transitions in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as revealed by noninvasive techniques in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 5042–5047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape M, Lambertz C, Happe T, Hemschemeier A (2012) Differential expression of the Chlamydomonas [FeFe]-hydrogenase-encoding HYDA1 gene is regulated by the COPPER RESPONSE REGULATOR1. Plant Physiol 159: 1700–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier G, Tolleter D, Billon E, Cournac L (2010) Auxiliary electron transport pathways in chloroplasts of microalgae. Photosynth Res 106: 19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posewitz MC, King PW, Smolinski SL, Zhang L, Seibert M, Ghirardi ML (2004) Discovery of two novel radical S-adenosylmethionine proteins required for the assembly of an active [Fe] hydrogenase. J Biol Chem 279: 25711–25720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ral JP, Colleoni C, Wattebled F, Dauvillée D, Nempont C, Deschamps P, Li Z, Morell MK, Chibbar R, Purton S, et al. (2006) Circadian clock regulation of starch metabolism establishes GBSSI as a major contributor to amylopectin synthesis in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol 142: 305–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rühle T, Hemschemeier A, Melis A, Happe T (2008) A novel screening protocol for the isolation of hydrogen producing Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strains. BMC Plant Biol 8: 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber U, Vidaver W (1974) Chlorophyll fluorescence induction in anaerobic Scenedesmus obliquus. Biochim Biophys Acta 368: 97–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicher RC. (1984) Characteristics of light-dependent inorganic carbon uptake by isolated spinach chloroplasts. Plant Physiol 74: 962–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Clowez S, Wollman FA, Vallon O, Rappaport F (2013) Cyclic electron flow is redox-controlled but independent of state transition. Nat Commun 4: 1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima M, Specht M, Naumann B, Hippler M (2010) Characterizing the anaerobic response of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by quantitative proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 9: 1514–1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M, Grieco M, Nurmi M, Rantala M, Suorsa M, Aro EM (2012) Regulation of the photosynthetic apparatus under fluctuating growth light. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367: 3486–3493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolleter D, Ghysels B, Alric J, Petroutsos D, Tolstygina I, Krawietz D, Happe T, Auroy P, Adriano JM, Beyly A, et al. (2011) Control of hydrogen photoproduction by the proton gradient generated by cyclic electron flow in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 23: 2619–2630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ünlü C, Drop B, Croce R, van Amerongen H (2014) State transitions in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strongly modulate the functional size of photosystem II but not of photosystem I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 3460–3465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt H, Bordignon E, Carbonera D, Dekker JP, Karapetyan N, Teutloff C, Webber A, Lubitz W, Schlodder E (2003) Species-specific differences of the spectroscopic properties of P700: analysis of the influence of non-conserved amino acid residues by site-directed mutagenesis of photosystem I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Biol Chem 278: 46760–46771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollman FA, Delepelaire P (1984) Correlation between changes in light energy distribution and changes in thylakoid membrane polypeptide phosphorylation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Cell Biol 98: 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacoby I, Pochekailov S, Toporik H, Ghirardi ML, King PW, Zhang S (2011) Photosynthetic electron partitioning between [FeFe]-hydrogenase and ferredoxin:NADP+-oxidoreductase (FNR) enzymes in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 9396–9401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Catalanotti C, Posewitz M, Alric J, Grossman A (2014). Insights into algal fermentation. In van Dongen JT, Licausi F, eds, Low-Oxygen Stress in Plants: Plant Cell Monographs, Vol 21 Springer, Vienna, pp 135–163 [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Watanabe CK, Terashima I, Noguchi K (2011) Physiological impact of mitochondrial alternative oxidase on photosynthesis and growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ 34: 1890–1899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.