Abstract

Oral health problems, among the most prevalent comorbidities related to addiction, require more attention by both clinicians and policy-makers. Our aims were to review oral complications associated with drugs, oral health care in addiction rehabilitation, health services available, and barriers against oral health promotion among addicts. Drug abuse is associated with serious oral health problems including generalized dental caries, periodontal diseases, mucosal dysplasia, xerostomia, bruxism, tooth wear, and tooth loss. Oral health care has positive effects in recovery from drug abuse: patients’ need for pain control, destigmatization, and HIV transmission. Health care systems worldwide deliver services for addicts, but most lack oral health care programs. Barriers against oral health promotion among addicts include difficulty in accessing addicts as a target population, lack of appropriate settings and of valid assessment protocols for conducting oral health studies, and poor collaboration between dental and general health care sectors serving addicts. These interfere with an accurate picture of the situation. Moreover, lack of appropriate policies to improve access to dental services, lack of comprehensive knowledge of and interest among dental professionals in treating addicts, and low demand for non-emergency dental care affect provision of effective interventions. Management of drug addiction as a multi-organ disease requires a multidisciplinary approach. Health care programs usually lack oral health care elements. Published evidence on oral complications related to addiction emphasizes that regardless of these barriers, oral health care at various levels including education, prevention, and treatment should be integrated into general care services for addicts.

Keywords: Oral heath, Oral diseases, Illicit drugs, Substance-related disorders

Introduction

Drug abuse, one of the world’s most devastating health problems (1), may also be considered a prevalent problem, because estimations show that, for example, in 2009 between 149 and 272 million 15- to 64-year-olds around the world reported using illegal drugs at least once during one year (2). Among them, reports are that 11 to 21 million were injecting drug users, mainly from China, the USA, and Russia (3). In Iran, based on a report from 2002, drug abuse has increased at a growth rate three times as great as population growth rate, and the annual rise in incidence of injecting drug abuse has been estimated to be 33% (4).

Drug abuse results in several direct consequences including multiple physical and mental problems such as cardiac crisis, respiratory depression, liver cirrhosis, nephropathy, infectious diseases such as hepatitis, AIDS, and tuberculosis, injury-associated disability, mental disorders such as depression, and oral health problems (5–6). These problems are partly the result of neglected self-care—a common behavior among addicts (7). Addicts usually ignore their health problems and seek health care only at advanced stages of disease with severe symptoms; this may complicate the treatment procedure in various ways (8–9). In this regard, these patients may give little priority to their own oral health by seeking only emergency treatment during the period of drug abuse (8, 10, 11).

In addition to direct consequences for addicts themselves, drug abuse has various indirect consequences for their circle of acquaintances and the whole society, such as reducing working time, raising health care costs, violence, crime, and the burden of diseases (1). In Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs), about 0.8%, and 0.4% of global deaths in 2000 resulted from drug abuse (12). This problem has a median relative risk of two for mortality and its annual cost exceeds 200 billion US dollars (13). According to a national survey of disease burden in Iran, illegal drug addiction and its AIDS- and accident-related consequences caused more than 800,000 DALYs in 2003. This survey ranked addiction as the fourth most important health problem in the country (14).

Among other indirect consequences, drug abuse is associated with increased risk of social problems such as crime in the form of drug trafficking, or theft and prostitution by drug users in order to finance their addiction. Health problems of drug abusers indirectly have negative effects on society via increasing health care costs, needle-sharing behavior, prostitution, AIDS, and other infectious diseases which result in additional health dangers for society (15).

Addiction and oral health

Oral health problems are among the most prevalent health problems associated with drug addiction (16). Drug abuse has both direct and indirect consequences for oral health and can exacerbate oral problems indirectly through its adverse effects on the users’ behavior and life style (8, 17).

The importance and seriousness of oral health problems among drug abusers necessitates making comprehensive dental care programs available to them. These programs should be integrated into general health care services (8, 11, 16, 18). Moreover, the programs should take advantage of multiple approaches involving education, prevention, and treatment. However, considering the illegal nature of drug abuse, either receiving services or providing them, presents several challenges.

Published data about epidemiology, pathological time course, clinical presentation, and effective treatment and preventive strategies regarding oral health among drug addicts worldwide are lacking (8, 17, 19, 20). This paper briefly reviews oral health consequences of illicit drug abuse, the role of dental care in addiction rehabilitation, health services available for addicts, and barriers against oral health promotion among these patients. Finally, we offer possible strategies at various levels for oral health promotion among addicts which can serve as a framework for future research and interventions.

Oral health consequences of illicit drug abuse

Excluding smoking and tobacco use as well as alcohol drinking, published evidence on effects of main categories of illegal drugs on oral health is growing. These drug categories include opiates, cannabis, hallucinogens, cocaine- and amphetamine-type stimulants, and various club drugs. Oral health complications associated with drug abuse may result from direct exposure of oral tissues to drugs during smoking or ingestion, biologic interaction of drugs with normal physiology of oral cavity, and effects of drugs on brain function which result in a spectrum of addictive behaviors such as risk-taking behavior, poor hygiene, aggression, and carelessness.

Oral health problems associated with opiates

Opiate drugs include opium, its psychoactive constituents such as morphine, and its semi-synthetic derivatives such as heroin (2). Opioid, as a broader term, also includes the synthetic derivatives of this family such as methadone. In opiate drug users, tooth loss, tooth extractions (17), and generalized tooth decay especially on smooth and cervical surfaces are common (21). Moreover, salivary hypofunction among these patients leads to xerostomia, burning mouth, taste impairment, eating difficulties, mucosal infections, and periodontal diseases (22). Periodontal diseases appear usually in the form of adult periodontitis, although reports also exist of necrotizing gingivitis (23, 24).

Heroin users show poor oral health in terms of caries and periodontal diseases (25–26). A study on heroin injectors reported that regardless of their oral hygiene, these patients suffer from progressive dental caries (27). Covering a wider area than typical cervical lesions, caries in these patients is darker and usually limited to buccal and labial surfaces. This pattern may be pathognomonic for heroin abuse (28).

Other oral conditions related to opioid addiction include bruxism, candidosis, and mucosal dysplasia (22). However, insufficient evidence exists to support a theory of a higher prevalence of oral cancer specifically in opioid abusers (29).

Oral health problems associated with cannabis

Cannabis abuse, mainly hashish and marijuana, leads to increased risk of oral cancer, dry mouth, and periodontitis (30–32). Onset of periodontitis among young adults has a dose-response association with cannabis abuse regardless of concurrent tobacco smoking (30). A systematic review by Versteeg et al. (33) showed oral side-effects of cannabis to include xerostomia, leukoedema, high prevalence of Candida albicans but not candidiasis, and higher DMF scores, and especially their D component (34). Based on one study, cannabis does not elevate the risk of caries by itself. The life-style of cannabis users combined with short-term decrease in saliva makes them highly susceptible to smooth-surface caries (35). Moreover, in another study, about half the cannabis users reported pulpitis during the period of cannabis smoking, a condition that may be attributed to cannabis as having adverse effects on their vasculature (36).

Oral health problems associated with stimulants

Stimulants including amphetamine, methamphetamine, cocaine, and crack-cocaine (2) have significant adverse effects on oral and dental health. Depending on the main method of drug administration, cocaine abusers show several oral and facial manifestations. Cocaine snorting is associated with nasal septum perforation, changes in sense of smell, chronic sinusitis, and perforation of the palate. Oral administration of cocaine may result in gingival lesions (37). Local application of cocaine onto the gingiva by addicts to test its quality may lead to gingival recession (38). Bruxism is a common complication in cocaine users leading to dental attrition (37). Following its oral or nasal application, cocaine powder reduces saliva pH, making the dentition susceptible to dental erosion (39). Crack-cocaine smoking produces burns and sores on the lips, face, and inside of the mouth which may increase the risk of oral transmission of HIV (40).

Methamphetamine abusers show bruxism, excessive tooth wear, xerostomia, and rampant caries (so-called meth mouth) (20, 41–43): a condition described by patients as “blackened, stained, rotting, crumbling or falling apart” (44). This is a distinct pattern of caries on buccal and cervical smooth tooth surfaces and proximal surfaces of the anterior teeth (41, 45). A direct relationship between rampant caries and methamphetamine abuse has, however, not yet been established. A wide range of behavioral factors in addition to drugs can contribute to dental caries in these patients: methamphetamine users face an increased risk of caries, related to lack of oral hygiene, high sugar intake, and decreased salivary secretion (20, 42, 46). Following the use of stimulants, patients report tooth grinding and clenching, both of which result in tooth wear, tooth sensitivity, and difficulty in chewing and in jaw opening (8).

Oral health problems associated with hallucinogens

Hallucinogens such as ecstasy and LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide) result in several oral oral complications including dry mouth, bruxism, and problems associated with malnutrition caused by drug-induced anorexia (32, 47). Chewing, grinding, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) tenderness are frequently reported by ecstasy users (48). Ecstasy-induced tooth wear attributed to grinding and clenching is more common on occlusal surfaces of back teeth than on incisal edges. This problem may be more the result of jaw clenching than of tooth grinding (49, 50). High intake of carbonated drinks to overcome the sensation of dry mouth after drug-taking may lead to dental caries and erosion (47). Topical use of ecstasy may result in oral-tissue necrosis and mucosal fenestration (51).

Oral health problems associated with club drugs

Club drugs including methylenedioxymethamphe-tamine (MDMA), ketamine, gamma-hydroxy-butyrate (GHB), and flunitrazepam are chemical substances used mainly by young people in recreational settings such as dance clubs and rave parties (52). These drugs are associated with several side-effects, among which oral complications have been frequently reported. For example, dry mouth and bruxism following the use of MDMA (ecstasy) may aggravate oral conditions and result in dental caries and tooth wear. Increased risk of dental erosion among these patients is associated with consumption of high amounts of acidic sugary drinks in order to relieve xerostomia and dehydration following use of this drug at dance parties. Furthermore, mucosal involvements such as ulcers, vestibular swelling, edema, and necrosis have been case-reported in ecstasy users (47). Cocaine, another drug used regularly by young people engaged in nightlife, has several orofacial side-effects such as nasal septum perforation, perforation of the palate, gingival involvement, erosion, and excessive tooth wear. These side-effects have been reported especially with concomitant use of ecstasy (37).

Indirect effects of drugs on oral health

It is difficult to identify and isolate the root causes of oral diseases among addicts, since they show a variety of unhealthy behaviors (17, 46). Poor oral hygiene, increased sugar intake, and inappropriate nutrition are examples (17, 26, 53, 54). Furthermore, a low priority set on oral health associated with a need to obtain drugs, fear of dentists, dental service acceptability, needle-phobia, self-medication, and structural factors in their life style lead to low use of dental services (8). This multifactorial association between drug abuse and insufficient oral health is also complicated by factors such as low socioeconomic status, limited education, and poor access to dental services (55). The difficulty of accessing dental services among drug abusers has been pointed out by several studies (11, 16, 19, 56). The cause may be the illegal nature of drug abuse which results in problems with either delivery of services or receipt of them.

According to various studies, a high rate of traumatic orofacial injuries occurs among drug abusers, ones such as fractured teeth or tooth loss following accidents or fights (8, 17, 57). What has therefore been suggested is that in all patients with dental trauma, the possibility of drug abuse should be considered (58). One study in Iran emphasized drug abuse as a contributing factor in almost all kinds of trauma, especially in violent injuries among young adults: around 27% of trauma patients in this study showed evidence of drug abuse (59).

Negative effects of drug addiction treatment on oral health

Methadone—a synthetic opioid widely used in management of opiate addiction—has several possible side-effects on oral health. High sugar content of an acidic nature, along with suppression of salivary secretion results in dental caries, erosion, and xerostomia (60). The status turns even more severe when patients hold this sugary syrup in their mouth to increase absorption time or to regurgitate it for later injection or sale (11). Sugar-free solutions, however, may reduce the risk of dental caries (60).

Some other medications used during drug addiction treatment include antidepressants (tricyclic, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), anti-psychotics such as phenothiazines for treatment of schizophrenia, and anti-anxiety drugs such as diazepam. They have a side-effect of salivary gland hypofunction and subsequent dry mouth leading to negative effects on oral health (61–63). In addition, with regard to the higher prevalence of HIV among injecting drug users (64), anti-HIV drugs such as dideoxyinosine and protease inhibitors may also have the side-effect of dry mouth (63). Xerogenic patients usually have problems with chewing, swallowing, tasting, or speaking. They may develop cracked lips, erythematic mucosa and sores, tooth decay, and periodontitis. Halitosis is also a common finding among these patients (62).

The role of oral health care (OHC) in addiction rehabilitation/ Oral health and relapse

During treatment, drug withdrawal may result in dental pain which interferes with treatment procedure and abstinence, and may lead to relapse (18, 27, 58). In a French case-control study of the impact of illicit drugs on oral health and the use of drugs for toothache, 52% of intravenous heroin users and 21% of other illicit drug abusers admitted using drugs as pain-killers (27). A similar finding on use of illicit drugs for toothache emerged from another study (36). Those quitting opiate use therefore require special care for pain control, and this should be integrated into their rehabilitation program (18, 27, 58). Those addiction treatment centers which provide OHC seem to be more successful in promoting both the oral and general health of their patients (65).

Dental pain relief provided by illegal drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and methadone may also be one cause of low dental attendance: many of the patients self-medicate for toothache even by injecting drugs directly into gingiva or teeth, masking pain and delaying appropriate treatment (8, 36).

Oral health, destigmatization, and resocialization

Dental care for patients receiving drug rehabilitation treatment can improve their oral health, help them to recover from drug abuse and to reconstruct a “non-addict” identity (8). Based on one study, former drug users were embarrassed about how their mouths looked, but this did not interfere with their resocialization (66). In another study of intravenous heroin users, the appearance of their smile had negative effect on their social life (27).

Oral health and HIV transmission

Illicit drugs such as methamphetamines may lead to an increase in risky sexual behaviors resulting in the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV and AIDS (67). Transmission of HIV via oral sex; however, seems to be less frequent, with the oral cavity being an unusual route of HIV transmission (68–70). Nonetheless, oral trauma and ulcers may enhance the risk of HIV transmission (70). For example, the possibility of oral HIV transmission may increase via burns and sores on lips, face, and in the mouth following the smoking of crack-cocaine (40).

Health services for drug addicts

Various health care systems around the world deliver diverse services for addicts in terms of treatment services provided, pharmacotherapy, human resources, financing methods, and prevention- and harm-reduction facilities. Treatment services may also be available in the forms of inpatient or outpatient medical detoxification, outpatient abstinence-oriented treatment, and substitution maintenance therapy for opioid dependence (71). Opioid agonist treatment with either methadone or buprenorphine may be implemented in a variety of settings such as public general hospitals, public mental health hospitals, and public treatment centers, plus private treatment centers, private practice (psychiatrists), primary health care, community pharmacies, and prisons. In addition, the proportion of patients treated in the public sector, private sector, joint public-private sector ventures, and NGOs varies substantially among countries. Policies on prevention methods and harm-reduction facilities may also vary depending on the country. These facilities include community-based needle-exchange programs, needle-exchange programs in prisons, supervised injection facilities, outreach services for injecting drug users, naloxone distribution, community-based bleach distribution, and in prisons bleach distribution (71–73).

With 1.2 million problematic drug users living in the country (74), Iran has confronted a huge drug abuse problem. Nonetheless, the nation’s treatment procedures are new (75). Treatment for substance abuse includes inpatient care and intensive outpatient programs. In spite of the criminal nature of drug abuse, as a psychiatric disorder, in-treatment drug users in Iran are no longer prosecuted. From 1994, the Prevention Deputy of the Iranian Welfare Organization set up outpatient centers for treatment of drug users (76). These centers offer the following services: detoxification, agonist-maintenance therapy, and individual, group, and family counseling, as well as relapse prevention, self-help groups, and psychotherapy (75). Approximately 1,438 centers across the country serve 642,516 patients. Among the centers, 85% belong to the private sector. In Tehran province are located 262 treatment centers including 250 nongovernmental and only 12 governmental centers working with 746 professionals, including 239 medical doctors, 61 psychiatrists, 138 nurses, 79 social workers, and 229 psychologists (77). A treatment center serving female drug users only was established in 2007 in Tehran to reduce drug-related harm among women (78). Based on a Rapid Situation Assessment (RSA) 2007 report, most of the drug users had received outpatient treatment in private centers (74).

In addition to treatment centers, Narcotic Anonymous groups and Therapeutic Communities were established in the country in 1994 and in 2001, respectively. Furthermore, a number of NGOs also exist, offering consultation and group therapy by former drug users (76). In contrast to many countries in the Middle East and North Africa, Iran has established maintenance treatment with methadone for those opioid-dependents who are in prison as an HIV-prevention package. At present, 142 prisons in all 30 provinces of Iran provide MMT programs for injecting and non-injecting opioid drug users (79).

Despite the seriousness of oral health problems among addicts and positive effects of dental care in addiction rehabilitation, these patients’ use of dental services at a low rate (18, 56). Addiction literature is also scarce regarding the topic of dental and oral health care (80). A few programs have been implemented to improve access to dental care among drug users (11, 18, 56, 57), but a distinct lack of published data explain access to care (11). In Iran, as in most countries worldwide, current health care services for addicts lack OHC programs.

Barriers against oral health promotion among drug addicts

Challenges to provision of an evidence-based picture of the oral health situation

There appear to be some challenges and barriers to research studies in this field, ones that are vital in order to provide reliable evidence for further interventions. It is difficult to access drug addicts as a target population. In addition to problems with drug abusers’ cooperation with and compliance in oral health studies, problems with their long-term follow-up are common (8, 81).

The multifactorial and complex nature of drug abuse and addictive behaviors and a tendency toward poly-drug abuse among addicts cause difficulties in determining the independent effects of each group of drugs or each aspect of addictive behavior on various oral health aspects (17). This may interfere with acquiring a reliable picture of oral health situation.

Challenges in providing and implementing effective treatments/interventions

Despite evidence as to addicts’ oral health problems, several barriers exist against provision of preventive and curative interventions. Dental professionals usually have negative attitudes toward and unwillingness to treat addicted dental patients (82). On the other hand, addicts generally show a low demand for non-emergency dental care and put a low priority on their oral health (8, 10–11, 66) In addition to the problems with utilization of dental services (56, 83), they may have problems with compliance with treatment procedures and fail to accept the suggested treatment plan (8, 45, 56).

Finally, lack of appropriate policies to improve access to oral health services (16) and poor collaboration between dental and general health care sectors serving drug addicts (23, 56) are other obstacles to effective interventions.

Strategies for oral health promotion among drug addicts

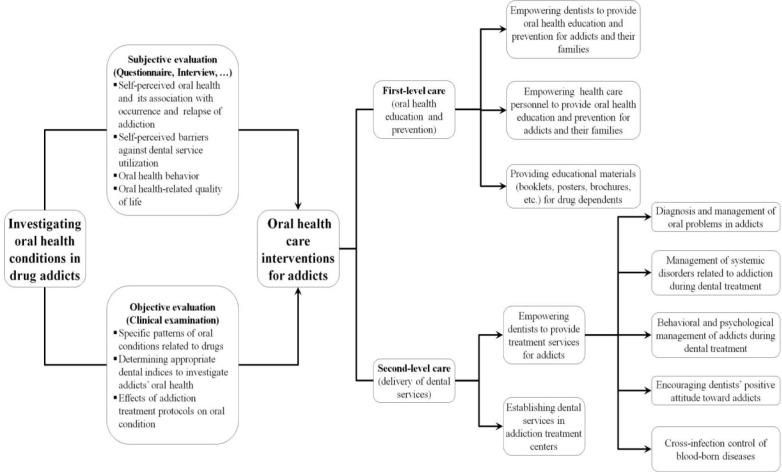

The following strategies serve as a framework for future research and interventions (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Oral health care strategies for drug addicts

Investigating oral health conditions in drug addicts

Evaluating the status of oral health among drug addicts would be possible by either objective or subjective methods. Objective evaluation via clinical examination may serve to identify specific patterns of oral conditions related to drugs, to determine appropriate dental indices in order to investigate addicts’ oral health, and to identify effects of addiction treatment protocols on their oral condition. Subjective evaluation via questionnaire or interview provides information on the self-perception of participants, including self-perceived oral health and its association with occurrence and relapse of addiction, self-perceived barriers against dentalservice utilization, oral health behavior, and oral health-related quality of life.

Oral health care interventions for drug addicts

Interventions available to drug addicts mainly include oral health education and prevention as first-level care, and delivery of dental services as second-level care. Examples of the former include empowering dentists on the one hand, and health care personnel in drug rehabilitation settings on the other to provide oral health education and prevention for addicts and their families, and to provide educational materials (booklets, posters, brochures, etc.) regarding prevention of oral problems. As second-level care: 1) Dental services should be established in addiction rehabilitation centers to improve access to dental treatment. 2) Dentists should be empowered in the following domains to provide treatment services for addicts:

-

a.

Diagnosis and management of oral problems in addicts

-

b.

Management of systemic disorders related to addiction during dental treatments

-

c.

Behavioral and psychological management of addicts during dental treatments

-

d.

Encouraging dentists’ positive attitude toward addicts

-

e.

Cross-infection control of blood-borne diseases

Discussion

Generally, OHC for drug abusers causes a huge challenge for society. Because of the aforementioned reasons, drug abusers have frequent and special dental needs and compared to their normal population counterparts are in greater need of access to dental treatments (8, 11, 16, 19, 56, 83). Thus, it seems necessary to integrate OHC programs into general health services provided for drug addicts.

Prevention and treatment of oral diseases among drug addicts may facilitate their rehabilitation treatment and recovery from drug dependence (8). Most health care-delivery systems around the world, however, lack OHC programs for addicts. Several barriers seem to exist against oral health promotion among drug addicts at both research and intervention levels. Because of the complexities of such an extensive team work, a multidisciplinary collaboration is necessary to conduct comprehensive research. Lack of appropriate settings such as specific dental clinics, and equipment inside drug rehabilitation centers, and lack of valid inventories and assessment protocols to detect common oral complications among drug users are problems. Additionally, lack of comprehensive knowledge of and interest among dental professionals in the importance and necessity of relevant studies, and a common worry over possible threats of transmission of HIV and hepatitis viruses during oral assessment of drug dependents interfere with appropriate need assessment.

In addition to the high cost of dental services and low coverage of dental insurance, concerns among policy-makers as to the cost-effectiveness of such interventions, especially in countries with develop-ping health care systems, may obstruct useful oral health interventions for addicts.

The relationship between drug abuse and oral complications provides an opportunity for dental professionals to detect drug abusers at early stages and refer them for rehabilitation. This approach can increase cost-effectiveness of interventions for drug control (46).

Conclusion

Despite the seriousness of oral health problems among drug addicts and positive effects of dental care in addiction rehabilitation, provision of effective OHC for these patients seems to face challenges including difficulty to access addicts as a target population, lack of appropriate settings to conduct oral health studies, lack of valid inventories and assessment protocols to detect common orodental pathologies among drug users, poor collaboration between dental and general health care sectors serving drug addicts, lack of appropriate policies to improve access to dental services by these patients, lack of comprehensive knowledge of and interest among dental professionals in treating addicts, and low demand for non-emergency dental care among these patients.

Regardless of all these barriers, OHC for drug addicts merits more emphasis in the future and should be implemented at various levels including education, preventive interventions, and therapeutic procedures. Moreover, because of the complexities of medical, social, psychological, and behavioral conditions of drug abusers, management of drug addiction as a multi-organ disease needs a multidisciplinary approach. Current health care programs for drug addicts usually lack OHC elements. Published evidence on oral complications related to drug addiction emphasizes that OHC programs should be integrated into general care services already available for drug abusers.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, Informed Consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgement

This study has been supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services Grant number 12900. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Nessa A, Latif SA, Siddiqui NI, Hussain MA, Hossain MA (2008). Drug abuse and addiction. Mymensingh Med J, 17 (2): 227–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drug and Crime (2011). World Drug Report 2011. Vienna: United Nations Publication, Sales No. E.11.XI.10. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, Wodak A, Panda S, Tyndall M, Toufik A, Mattick RP (2008). Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet, 372 (9651): 1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi Movaghar A, Mohammad K, Razzaghi EM (2002). Trend of drug abuse situation in Iran: a three-decade survey. Hakim Research Journal, 5 (3): 171–81. [Abstract in English] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Lin KM (2009). Health consequences of illegal drug use. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 22 (3): 287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brienza RS, Stein MD, Chen M, Gogineni A, Sobota M, Maksad J, Hu P, Clarke J (2000). Depression among needle exchange program and methadone maintenance clients. J Subst Abuse Treat, 18 (4): 331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affinnih YH (1999). A preliminary study of drug abuse and its mental health and health consequences among addicts in Greater Accra, Ghana. J Psychoactive Drugs, 31 (4): 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PG, Acquah S, Gibson B (2005). Drug users: oral health-related attitudes and behaviours. Br Dent J, 198 (4): 219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santolaria-Fernández FJ, Gómez-Sirvent JL, González-Reimers CE, Batista-López JN, Jorge-Hernández JA, Rodríguez-Moreno F, Martínez-Riera A, Hernández-García MT (1995). Nutritional assessment of drug addicts. Drug Alcohol Depend, 38 (1): 11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma P, Nordenram G (2005). The perceptions of homeless people in Stockholm concerning oral health and consequences of dental treatment: a qualitative study. Spec Care Dentist, 25 (6): 289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnock S, Owen S, Brookes V, Williams M (2004). A community based programme to improve access to dental services for drug users. Br Dent J, 196 (7): 385–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Taylor B, Room R (2006). Global burden of disease from alcohol, illicit drugs and tobacco. Drug Alcohol Rev, 25 (6): 503–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Martins SS, Nestadt G, Bienvenu OJ, Clarke D, Alexandre P (2008). The burden of mental disorders. Epidemiol Rev, 30: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Medical Education (2007). Study of the burden of oral disease and injuries in Iran. MOHME. [Summary in English] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drug and Crime (1998). Economic and social consequences of drug abuse and illicit trafficking. (Available at: http://www.unodc.org/pdf/technical_series_1998–01-01_1.pdf) [Last access on May 2013] [Google Scholar]

- Metsch LR, Crandall L, Wohler-Torres B, Miles CC, Chitwood DD, McCoy CB (2002). Met and unmet need for dental services among active drug users in Miami, Florida. J Behav Health Serv Res, 29 (2): 176–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece AS (2007). Dentition of addiction in Queensland: poor dental status and major contributing drugs. Aust Dent J, 52 (2): 144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molendijk B, Ter Horst G, Kasbergen M, Truin GJ, Mulder J (1996). Dental health in Dutch drug addicts. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 24 (2): 117–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laslett AM, Dietze P, Dwyer R (2008). The oral health of street-recruited injecting drug users: prevalence and correlates of problems. Addiction, 103 (11): 1821–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morio KA, Marshall TA, Qian F, Morgan TA (2008). Comparing diet, oral hygiene and caries status of adult methamphetamine users and nonusers: a pilot study. J Am Dent Assoc, 139 (2): 171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees TD (1992). Oral effects of drug abuse. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med,3(3): 163–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titsas A, Ferguson MM (2002). Impact of opioid use on dentistry. Aust Dent J, 47 (2): 94–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelillo IF, Grasso GM, Sagliocco G, Villari P, D’Errico MM (1991). Dental health in a group of drug addicts in Italy. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 19 (1): 36–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RK, Baer PN (1971). Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis in drug addict patients being withdrawn from drugs. Report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol, 31 (2): 200–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Shi XC, Hu DY, Li X (2012). The poor oral health status of former heroin users treated with methadone in a Chinese city. Med Sci Monit, 18 (4): PH51–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picozzi A, Dworkin SF, Leeds JG, Nash J (1972). Dental and associated attitudinal aspects of heroin addiction: a pilot study. J Dent Res, 51 (3): 869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madinier I, Harrosch J, Dugourd M, Giraud-Morin C, Fosse T (2003). The buccal-dental health of drug addicts treated in the University hospital centre in Nice. Presse Med, 32 (20): 919–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal AH (1967). Atypical caries of the narcotics addict. Dent Surv, 43 (12): 44–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewelyn J, Mitchell R (1994). Smoking, alcohol and oral cancer in south east Scotland: a 10-year experience. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 32 (3): 146–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson WM, Poulton R, Broadbent JM, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Beck JD, Welch D, Hancox RJ (2008). Cannabis smoking and periodontal disease among young adults. JAMA, 299 (5): 525–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens AGMS, Bressi T (2007). Marijuana as promoter for oral cancer? More than a suspect. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment, 6 (3): 117. [Google Scholar]

- Fazzi M, Vescovi P, Savi A, Manfredi M, Peracchia M (1999). The effects of drugs on the oral cavity. Minerva Stomatol, 48 (10): 485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg PA, Slot DE, van der Velden U, van der Weijden GA (2008). Effect of cannabis usage on the oral environment: a review. Int J Dent Hyg, 6 (4): 315–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cugno F, Perec CJ, Tocci AA (1981). Salivary secretion and dental caries experience in drug addicts. Arch Oral Biol, 26 (5): 363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz-Katterbach M, Imfeld T, Imfeld C (2009). Cannabis and caries--does regular cannabis use increase the risk of caries in cigarette smokers? Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed, 119 (6): 576–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madinier I (2002). Illicit drugs for toothache. Br Dent J, 192 (3): 120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanksma CJ, Brand HS (2005). Cocaine abuse: orofacial manifestations and implications for dental treatment. Int Dent J, 55 (6): 365–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapila YL, Kashani H (1997). Cocaine-associated rapid gingival recession and dental erosion. A case report. J Periodontol, 68 (5): 485–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutchkoff DJ, Eisenberg E, O’BrienJE, Ponzillo JJ (1990). Cocaine-induced dental erosions. N Engl J Med, 322 (6): 408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruque S, Edlin BR, McCoy CB, Word CO, Larsen SA, Schmid DS, Von Bargen JC, Serrano Y (1996). Crack cocaine smoking and oral sores in three inner-city neighborhoods. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol, 13 (1): 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto DT, Rhodus NL (2009). Methamphetamine abuse and dentistry. Oral Dis, 15 (1): 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini T, Edwards PC, Kimmes NS, Carroll LR, Shaner JW, Dowd FJ (2005). Etiology of xerostomia and dental caries among methamphetamine abusers. Oral Health Prev Dent, 3 (3): 189–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JR, Brofeldt BT (2000). Patterns of tooth wear associated with methamphetamine use. J Periodonto, 71 (8): 1371–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ADA Division of Communications; Journal of the American Dental Association; ADA Division of Scientific Affairs (2005). For the dental patient … methamphetamine use and oral health. J Am Dent Assoc, 136 (10): 1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner JW (2002). Caries associated with methamphetamine abuse. J Mich Dent Assoc, 84 (9): 42–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cretzmeyer M, Walker J, Hall JA, Arndt S (2007). Methamphetamine use and dental disease: results of a pilot study. J Dent Child (Chic), 74 (2): 85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand HS, Dun SN, Nieuw Amerongen AV (2008). Ecstasy (MDMA) and oral health. Br Dent J, 204 (2): 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath C, Chan B (2005). Oral health sensations associated with illicit drug abuse. Br Dent J, 198 (3): 159–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milosevic A, Agrawal N, Redfearn P, Mair L (1999). The occurrence of toothwear in users of Ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 27 (4): 283–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfearn PJ, Agrawal N, Mair LH (1998). An association between the regular use of 3,4 methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (ecstasy) and excessive wear of the teeth. Addiction, 93 (5): 745–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier WJ, Dhariwal DK, Patton DW, Bishop K (2003). Ecstasy related periodontitis and mucosal ulceration -- a case report. Br Dent J, 194 (4): 197–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahlinger PM (2004). Club drugs: MDMA, gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), Rohypnol, and ketamine. Am Fam Physician, 69: 2619–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekarchizadeh H, Khami MR, Mohebbi SZ, Virtanen JI (2013). Oral health behavior of drug addicts in withdrawal treatment. BMC Oral Health, 13: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zador D, Lyons Wall PM, Webster I (1996). High sugar intake in a group of women on methadone maintenance in south western Sydney, Australia. Addiction, 91 (7): 1053–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheutz F (1984). Dental health in a group of drug addicts attending an addiction-clinic. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 12 (1): 23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan J, Aggleton M, Carson T (2001). Dental health and access to dental treatment: a comparison of drug users and non-drug users attending community pharmacies. Br Dent J, 191 (8): 453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheutz F (1985). Five year evaluation of a dental care delivery system for drug addicts in Denmark. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 12: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock K (1999). Dental care of patients with substance abuse. Dent Clin North Am, 43 (3): 513–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soroush A R, Modaghegh M H S, Karbakhsh M, Zarei M R (2006). Drug abuse in hospitalized trauma patients in a university trauma care center: an explorative study. Tehran University Medical Journal, 64 (8): 43–8. [Abstract in English] [Google Scholar]

- Nathwani NS, Gallagher JE (2008). Methadone: dental risks and preventive action. Dent Update, 35 (8): 542–4, 547–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ship JA (2004). Xerostomia: aetiology, diagnosis, management and clinical implications. In: Saliva and Oral Health. Eds, Edgar M, Davies C, O’Mullane D. BDJ Books, London, pp. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Cassolato SF, Turnbull RS (2003). Xerostomia: clinical aspects and treatment. Gerodontolog, 20 (2): 64–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully C (2003). Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth. Oral Dis, 9 (4): 165–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasteh K, Des Jarlais DC, Perlis TE (2008). Alcohol and HIV sexual risk behaviors among injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend, 95 (1–2): 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Hser YI, Herbeck D (2006). Tooth retention, tooth loss and use of dental care among long-term narcotics abusers. Subst Abus, 27 (1–2): 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheutz F (1985). Dental habits, knowledge, and attitudes of young drug addicts. Scand J Soc Med, 13 (1): 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariatirad S, Maarefvand M, Ekhtiari H (2013). Emergence of a methamphetamine crisis in Iran. Drug Alcohol Rev, 32 (2): 223–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo J, Perea MA, del Romero J, Cano J, Hernando V, Bascones A (2006). Oral transmission of HIV, reality or fiction? An update. Oral Dis, 12 (3): 219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page-Shafer K, Shiboski CH, Osmond DH, Dilley J, McFarland W, Shiboski SC, Klausner JD, Balls J, Greenspan D, Greenspan JS (2002). Risk of HIV infection attributable to oral sex among men who have sex with men and in the population of men who have sex with men. AIDS, 16 (17): 2350–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully C, Porter S (2000). HIV topic update: oro-genital transmission of HIV. Oral Dis, 6 (2): 92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Management of substance abuse. Country profiles: Resources for the Prevention and Treatment of Substance Use Disorders. (Available at: http://www.-who.int/substance_abuse/publictions/atlas_report/profiles/en/index.html#U) [Last access on May 2013] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2009). Assessment of Compulsory Treatment of People Who Use Drugs in Cambodia, China, Malaysia and Viet Nam: an application of Selected Human Rights Principles. (Available at: http://www.wpro.who.int/publications/docs/FINALforWeb_Mar17_Compulsory_Treatment.pdf) [Last access on May 2013] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (England) and the devolved administrations (2007). Drug Misuse and Dependence: UK Guidelines on Clinical Management. London: Department of Health (England), the Scottish Government, Welsh Assembly Government and Northern Ireland Executive. [Google Scholar]

- Iranian Drug Control Headquarter (2007). National Rapid Situation Analysis of Drug Abuse Status in Iran. Iran: Presidency. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drug and Crime. Triangular Clinic & Rehabilitation Centre, Iran. (Available at: http://www.unodc.org/treatment/en/Iran_resource_centre_11.html) [Last access on May 2013] [Google Scholar]

- Mokri A (2002). Brief overview of the status of drug abuse in Iran. Arch Iranian Med, 5 (3): 184. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Medical Education (2008). Data Registration of Substance Abuse Treatment Centers (Social Welfare Organization, Universities of Medical Sciences, State Prisons). Drug Addiction Office. [Unpublished report] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan K, Salimi S, Nassirimanesh B, Mohsenifar S, Mokri A (2011). The establishment of a methadone treatment clinic for women in Tehran, Iran. J Public Health Policy, 32 (2): 219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnia M, Ebrahimi B, Shams A, Zamani S (2010). Scaling up methadone maintenance treatment for opioid-dependent prisoners in Iran. Int J Drug Policy, 21 (5): 422–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Laine C, Cohen A, Hauck WW (2002). Effect of medical, drug abuse, and mental health care on receipt of dental care by drug users. J Subst Abuse Treat, 23 (3): 239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro Edel P, Oliveira JA, Zambolin AP, Lauris JR, Tomita NE (2002). Integrated approach to the oral health of drug-addicted undergoing rehabilitation. Pesqui Odontol Bras, 16 (3): 239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkes M, Sparkes S, Smith M (1995). Dentists’ responses to drug misusers. Health Trends, 27 (1): 12–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins JL, Wenger L, Lorvick J, Shiboski C, Kral AH (2010). Health and oral health care needs and health care-seeking behavior among homeless injection drug users in San Francisco. J Urban Health, 87 (6): 920–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]