Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study was to assess the consequence of sequence variations in HLA-C*03:04-presented HIV-1 p24 Gag epitopes on binding of the inhibitory NK cell receptor KIR2DL2 to HLA-C*03:04.

DESIGN

HIV-1 may possibly evade recognition by KIR+ NK cells through selection of sequence variants that interfere with the interactions of inhibitory KIRs and their target ligands on HIV-1-infected cells. KIR2DL2 is an inhibitory NK cell receptor that binds to a family of HLA-C ligands. Here, we investigated whether HIV-1 encodes for HLA-C*03:04-restricted epitopes that alter KIR2DL2 binding.

METHODS

Tapasin-deficient 721.220 cells expressing HLA-C*03:04 were pulsed with overlapping peptides (10mers overlapping by 9 amino acids, spanning the entire HIV-1 p24 Gag sequence) to identify peptides that stabilized HLA-C expression. Then, the impact that sequence variation in HLA-C*03:04-binding HIV-1 epitopes has on KIR2DL2 binding and KIR2DL2+ NK cell function was determined using KIR2DL2-Fc constructs and NK cell degranulation assays.

RESULTS

Several novel HLA-C*03:04 binding epitopes were identified within the HIV-1 p24 Gag consensus sequence. Three of these consensus sequence peptides (Gag144-152, Gag163-171, and Gag295-304) enabled binding of KIR2DL2 to HLA-C*03:04 and resulted in inhibition of KIR2DL2+ primary NK cells. Furthermore, naturally occurring minor variants of epitope Gag295-304 enhanced KIR2DL2 binding to HLA-C*03:04.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data show that naturally occurring sequence variations within HLA-C*03:04-restricted HIV-1 p24 Gag epitopes can have a significant impact on the binding of inhibitory KIR receptors and primary NK cell function.

Keywords: Innate Immunity, HIV-1 epitopes, Natural Killer cell, Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor

Introduction

NK cells are important early innate effector cells of the antiviral immune response, as they can directly lyse virally infected cells and but also indirectly regulate innate and adaptive immune responses via cytokine production and crosstalk with dendritic cells [1–4]. NK cell activity is determined by the interaction of inhibitory and activating NK cell receptors with ligands expressed on target cells. Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) are one of the major receptor families expressed on NK cells and interact with HLA class I ligands. Several studies have suggested that KIR-expressing NK cells might play an important role in the control of HIV infection [5–9].

Characterization of the interactions between KIRs and their HLA ligands by crystal structure analysis have shown that KIRs directly interact not just with the α1 and α2 domain s of HLA class I ligands, but also with the bound peptide, although to a lesser extent than T-cell receptors [15–19]. KIRs therefore recognize their cognate HLA class I ligands in a peptide-dependent manner [15, 19–31]. Charge complementarity dominates KIR-HLA interactions and mutations in presented peptides can alter the interface salt bridges to either diminish or promote KIR-HLA binding [20–24, 30, 31]. In particular, variations in C-terminal residues of HLA class I-bound peptides can modulate KIR engagement and, ultimately, NK cell responsiveness to target cells [15, 19, 21–23, 27–31].

In this study we investigated the consequences of sequence variations in HLA-C*03:04-presented HIV-1 p24 Gag epitopes on binding of KIR2DL2. KIR2DL2 is an inhibitory KIR which binds to HLA-C group 1 ligands and has a population frequency of ~50% [10]. HLA-C expression is believed to influence HIV-1 disease progression, as it is immune to down-regulation by HIV-1 Nef (unlike HLA-A and HLA-B) [11], and higher expression levels have been associated with improved control of HIV-1 infection [12–14]. The protective effect of HLA-C expression might in part rely on its peptide-dependent interaction with KIR+ NK cells. Here we identified several HIV-1 epitopes, as well as naturally occurring variants, that alter KIR2DL2 binding to HLA-C*03:04 and modulate primary KIR2DL2+ NK cell function in a sequence-dependent manner.

Materials and Methods

Cells

721.220 cells (referred to as 220 cells hereafter) were stably transfected with HLA-C*03:04 as previously described for 721.221 cells [32] and were used in the initial screening for HLA-C*03:04 stabilizing peptides. 220 cells do not express HLA-A and HLA-B but retain partial expression of HLA-C*01:02 [33]. Furthermore, 220 cells lack functional tapasin, which impedes expression of non-classical HLA class I and impairs loading of peptides onto classical HLA class I [33, 34]. A 721.221 cell line transduced with herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP47 (kindly provided by Emmanual J.H.J. Wiertz, Department of Medical Microbiology, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands) was stably transfected with HLA-C*03:04 and these cells (referred to as 221-ICP47-C*03:04 hereafter) were used in all further experiments. 221 cells do not express HLA-A, -B, or -C, and the transduced ICP47 inhibits TAP function and thus impairs the loading of peptides onto HLA class I. Both cell lines were cultured in selection medium [RPMI medium 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS, Sigma-Aldrich), 2500 U/mL penicillin, 2500 μg/mL streptomycin, 100mM L-Glutamine (Cellgro), and 1 ug/mL puromycin] at 37°C under 5% CO2.

For studies of primary NK cell function, six healthy HIV-1-negative individuals were recruited at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH, Boston, MA). The study was approved by Partners Institutional Review Board (IRB) and each subject gave informed consent for participation.

HLA-C stabilization assay

A total of 222 10-mer peptides overlapping by 9 amino acids and spanning the entire HIV-1 p24 Gag consensus sequence were used to identify HIV-1 peptides that stabilize HLA-C*03:04 expression. 2×105 220-C*03:04 cells were co-incubated with these overlapping peptides (OLPs) in non-supplemented RPMI for 30 hours at 37°C. As controls, 220-C*03:04 cells were cultured in the absence of peptide or with the previously described HLA-C*03:04-binding self-peptides, GAVDPLLAL (GAL) and GAVDPLLKL (GKL) [15]. To detect HLA-C stabilization, peptide-pulsed 220-C*03:04 cells were stained with mouse anti-human HLA-C specific antibody (DT9) and secondary antibody anti-mouse IgG-PE (Sigma Aldrich). After staining, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by flow cytometry. HLA-C*03:04-binding peptides were re-confirmed in 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells. Briefly, 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells were co-incubated with HIV-1 and control peptides (100 μM) in non-supplemented RPMI for 20 h at 26°C. HLA stabilization was measured using the pan-HLA antibody (W6/32; BioLegend).

Epitope prediction tools

To screen for potential HLA-C*03:04 binding epitopes among HIV-1 p24 Gag, the entire HIV-1 p24 Gag consensus sequence was entered into the NetMHCpan 2.4 HLArestrictor tool program (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/HLArestrictor/). Standard recommended threshold settings were used. In search of previously described HLA-C*03 restricted HIV-1 p24 Gag epitopes the Los Alamos CTL epitope database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/immunology/ctl_search) was employed. To check for sequence variations at P7, P8, and P9 among identified HLA-C*03:04-presented epitopes, the Los Alamos HIV-1 Sequence Database QuickAlign tool (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/QUICK_ALIGN/QuickAlign.html), which includes amino acid sequences of more than 3500 described HIV-1 variants, was used.

KIR2DL2 binding assay

The peptides, and their naturally occurring variants, that resulted in strong HLA-C stabilization in 220-C*03:04 and 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells were tested for binding of KIR2DL2 to peptide-stabilized HLA-C*03:04 on 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells. After incubating 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells with the candidate peptides, cells were stained with KIR2DL2-Fc (recombinant human KIR2DL2-Fc/CD158b1 chimera; R&D Systems) and anti-human Fc antibody (PE conjugated IgG Goat Anti-Human pAb, Invitrogen). After staining, cells were washed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and then analyzed by flow cytometry.

NK cell degranulation assay

NK cell degranulation assays were performed with freshly isolated and purified NK cells from six healthy individuals of which two were KIR2DL2+/C1+, three were KIR2DL2-3+/C1+ and one was KIR2DL2-3+/C1-2+. Primary NK cells were isolated by incubating whole blood with RosetteSep™ NK cell enrichment cocktail (Stem Cell) and performing a Histopaque®-1077 (Sigma) density gradient centrifugation. NK cells were subsequently incubated overnight in RPMI medium 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS, Sigma-Aldrich), 2500 U/mL penicillin, 2500 ug/mL streptomycin, 100mM L-Glutamine (Cellgro), and 1.0 ng/mL IL-15 (Cellgro). Next, NK cells (1×105) were co-incubated with peptide-pulsed 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells (5×105) at an effector-target-ratio of 1:5 in RPMI containing anti-human CD107a-PE-Cy7 (12.5 μL/mL). Cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 26°C in 5% CO2, after which monensin (1.5 μL/mL, BD GolgiStop™) was added, followed by an additional 5 hours of incubation at 26°C in 5% CO2. Cells were stained with anti-CD3-PB, anti-CD16-BV785, anti-CD56-BV605, anti-CD14/19-BV510, anti-KIR2DL2/3-PE, and anti-KIR2DL3-APC, washed, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Data acquisition and analysis

Flow cytometry data was acquired using BD 3 Laser LSRII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software version 9.4.4 (Tree Star, Inc.). For statistical analysis GraphPad Prism 5.0d (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used. HLA stabilization values are presented as relative mean ± SEM. Relative mean was calculated by dividing the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of a given OLP by the MFI of the negative control ‘no peptide’ in the respective assay. KIR2DL2 binding is presented in percentages KIR2DL2-Fc+ cells and NK cell degranulation values are expressed as normalized degranulation. Normalized degranulation was calculated by dividing the percentage CD107a+ cells of a given sample by the percentage CD107a+ cells of negative control sample ‘GKL’ after reduction of background CD107a+ expression. Statistical comparison between groups was performed using repeated measures ANOVA.

Results

Several p24 Gag-derived peptides stabilize HLA-C expression on 220-C*03:04 cells

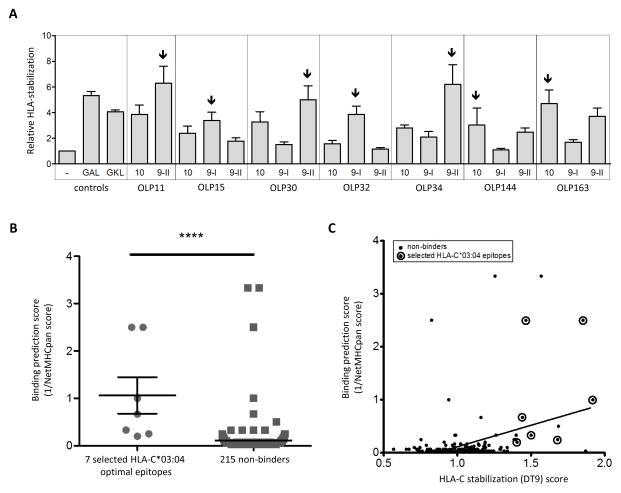

In order to investigate whether HIV-1 peptides presented by HLA-C*03:04 can impact the binding of KIR2DL2, we initially screened for HIV-1 p24 Gag peptides that stabilized HLA-C expression on HLA-C*03:04-expressing tapasin-deficient 220 cells. We used 222 10-mer peptides overlapping by 9 amino acids that spanned the entire HIV-1 p24 Gag consensus sequence (based on sequences published in the Los Alamos database http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/index, see Supplemental table 1). Two previously described HLA-C*03-presented self-peptides GAL (GAVDPLLAL) and GKL (GAVDPLLKL) were also included as positive controls (see supplemental figure 1) [15]. Table 1 presents the seven OLPs that induced strong HLA-C stabilization (i.e. high DT9 fluorescence intensity) in 220-C*03:04 cells, which were also confirmed in 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells. Given that 9 amino acid-long peptides have been described to have the optimal length for HLA-C*03:04 binding [24], we investigated whether 9-mer peptides contained within these seven 10-mers could stabilize HLA-C*03:04 more efficiently. In most cases, one of the respective 9-mer peptides stabilized HLA-C*03:04 expression more so than its 10-mer counterpart (figure 1A). Thus, in subsequent KIR2DL2-Fc-binding experiments and functional assays, we used the most strongly stabilizing peptides. From the peptide screening in 220-C*03:04 cells, an HLA-C stabilization (DT9) score was generated and calculated as the median DT9 fluorescence intensity of a given OLP divided by the median DT9 fluorescence intensity of all 222 OLPs in an average of four independent experiments. Additionally, to verify whether the identified HLA-C-stabilizing peptides contained HLA-C*03 binding motifs or previously described HLA-C*03-restricted epitopes, we used the NetMHCpan 2.4 HLArestictor tool (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/HLArestrictor/) and the Los Alamos CTL / CD8 T cell epitope database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/immunology/ctl_search). All seven selected peptides that stabilized HLA-C expression were also predicted to serve as HLA-C*03:04 binders by the NetMHCpan 2.4 HLArestrictor tool (table 1), and the HLArestrictor tool percentile rank scores of the seven selected optimal epitopes differed significantly from the scores of the 215 non-binders (Mann Whitney test, p-value <0.0001, figure 1B). However, some of the peptides that did not show any HLA-C*03:04 binding experimentally still scored well using the HLArestrictor tool. We furthermore observed a highly significant but moderate correlation between percentile rank scores of all 222 OLPs and our HLA-C stabilization assay values (Spearmans r-value 0.24, p-value < 0.0001, figure 1C). Three of the seven identified HLA-C*03:04 binding peptides had also previously been described in the Los Alamos database to contain HLA-C*03:04-restricted CTL epitopes; OLP11 (Gag140-152 and Gag145-152) [35, 36], OLP34 (Gag167-175) [37] and OLP163 (Gag295-304) [38-42] (table 1). However, two other previously described HLA-C*03-restricted CTL epitopes, TLRAEQATQD (Gag303-312) [43] and KALGPAATL (Gag335-343) [37], were not identified using our stabilization assay, probably due to sequence differences between the described epitope and the epitope used in our assay (TLRAEQASQE versus TLRAEQATQD and KALGPAATLE versus KALGPAATL) [37, 43]. In conclusion, we identified seven peptides within HIV-1 p24 Gag that resulted in strong HLA-C stabilization on both 220-C*03:04 and 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells, and these seven peptides were subsequently selected for KIR2DL2 binding assays.

Table 1.

| OLP and variantsa | Gag location | Consensus sequence epitopes and variants at position 7/8/9b | Frequency of variants (%)c | NetMHCpan % rank scored | Described HLA-C03 CTL epitopes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 11 | Gag143-152 | VHQAISPRTL | no variants | 1.5 | GQMVHQAISPRTLNQAISPRTL |

|

| |||||

| 15 | Gag147-156 | ISPRTLNAWV | no variants | 3.0 | - |

|

| |||||

| 30-CSeq | Gag162-171 | KAFSPEVIPM | 95.4% | 0.4 | - |

| 30-I | .................I...... | 4.5% | |||

|

| |||||

| 32 | Gag164-173 | FSPEVIPMFS | no variants | 0.4 | - |

|

| |||||

| 34-CSeq | Gag166-175 | PEVIPMFSAL | 56.4% | 4.0 | EVIPMFSAL |

| 34-8A | .................A...... | 2.4% | |||

| 34-8M | .................M...... | 1.3% | |||

| 34-8T | .................T...... | 39.1% | |||

|

| |||||

| 144 | Gag276-285 | MYSPTSILDI | no variants | 0.05 | - |

|

| |||||

| 163-CSeq | DYVDRFFKTL | 90.1% | 5.0 | YVDRFFKTL YVDRFFKVL |

|

| 163-9A | Gag295-304 | .................A...... | 2.4% | ||

| 163-9C | .................C...... | 1.5% | |||

| 163-9I | .................I...... | 1.0% | |||

| 163-9V | .................V...... | 5.0% | |||

Consensus sequence (CSeq) derived overlapping peptide (OLP) and their naturally occurring variant as named in this study.

Amino acid sequence of OLPs and variant epitopes. Underlining defines the 9- or 10-mers used in further KIR2DL2 and NK cell degranulation experiments based on results shown in figure 1A.

Frequency of variants (%) within >3500 described HIV-1 sequences (source: Los Alamos HIV-1 Sequence Database QuickAlign tool http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/index)

The lower the NetMHCpan percentile rank score, the higher the predicted affinity of the peptide for HLA-C*03:04.

Figure 1. Comparison of HLA-C*03:04 stabilization capacity of 9- and 10-mer epitopes, and validation of HLA stabilization with online binding prediction scores.

(A) Repetitive comparison of 9-mers contained within the selected 10-mers for their ability to stabilize HLA-C*03:04 expressed on 221 cells (N=3). The most strongly stabilizing peptides (arrows) were used in further experiments.

(B-C) OLP-induced HLA-C stabilization results were compared to the binding prediction scores. Binding prediction scores were calculated as 1 / NetMHCpan percentile rank. NetMHCpan percentile rank values were obtained using HLArestrictor tool from the Centre for Biological Sequence analysis (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/HLArestrictor/). If the HLA-C*03:04 stabilizing 10-mer was not among the prediction results, we listed the percentile rank score of the corresponding 8-mer or 9-mer variant instead. (B) Comparison of binding prediction scores of the seven selected HLA-C*03:04 stabilizing epitopes (see table 1) to the binding prediction scores of the 215 OLPs we assigned to be non-binders (p-value <0.0001). (C) Binding prediction scores plotted against DT9 HLA-C stabilization values for all 222 OLPs. The encircled dots represent the seven selected optimal epitopes. All non-encircled dots represent the peptides we assigned to be non-binders based on HLA-C-stabilization results. Correlation statistics: p-value < 0.0001, r-value 0.24.

A subset of HLA-C*03:04 restricted epitopes allow for KIR2DL2 binding

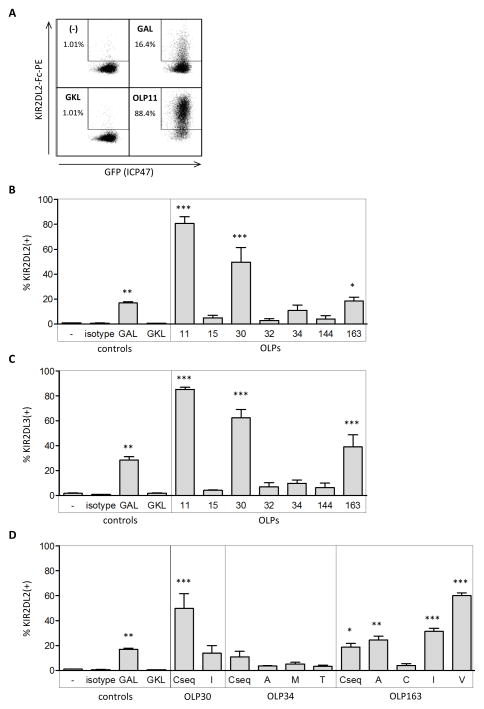

To assess the influence that HLA-C*03:04-bound HIV-1 epitopes have on KIR2DL2 binding to HLA-C*03:04, we stained peptide-pulsed 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells with KIR2DL2-Fc. 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells were pulsed with (i) no peptide, (ii) the HLA-C*03:04-presented control peptides GAVDPLLAL (GAL) or GAVDPLLKL (GKL), or (iii) the seven HIV-1 p24 Gag peptides (consensus sequence peptides of table 1). GAL and GKL served as a positive and a negative control, respectively, for KIR2DL2 binding, given that it has previously been shown that GAL allows for KIR2DL2 binding to HLA-C*03 while GKL abrogates it. (see figure 2A for representative histograms) [15]. The results of repeated (N=3) KIR2DL2 binding analyses are summarized in figure 2B. Three out of the seven tested HLA-C*03:04 binding epitopes, OLP11 (Gag144-152), OLP30 (Gag163-171), and OLP163 (Gag295-304) allowed for similar or stronger KIR2DL2-Fc binding when compared to the positive control peptide GAL (figure 2B). The seven selected peptides were further tested for their ability to engage KIR2DL3-Fc to HLA-C*03:04, given that KIR2DL3 and KIR2DL2 are alleles of each other and are very similar in sequence and binding properties. Indeed, KIR2DL3-Fc was engaged by the same three HLA-C*03:04-bound peptides as KIR2DL2-Fc, and at similar levels (figure 2C). Taken together, three out of seven HLA-C*03:04-presented epitopes derived from the HIV-1 p24 consensus sequence facilitated KIR2DL2-Fc and KIR2DL3-Fc binding, while the remaining four peptides did not allow for binding of either KIR2DL2-Fc or KIR2DL3-Fc to peptide-pulsed 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells.

Figure 2. KIR2DL2 binding data of 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells incubated with the seven selected optimal epitopes and their variants.

(A) Representative dotplots of KIR2DL2-Fc binding to TAP-impaired 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells after co-incubation with no peptide, control peptide GKL (GAVDPLLKL, negative control) and control peptide GAL (GAVDPLLAL, positive control) and OLP11 (HQAISPRTL). All cells express GFP, indicating successful ICP47 transfection and thus optimal impairment of TAP. (B) KIR2DL2 binding to 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells pulsed with no peptide, GAL, GKL, or the respective seven selected HLA-C*03:04 optimal epitopes, expressed as percentage KIR2DL2 binding (% KIR2DL2+, N=3. Three OLPs (OLP 11, 30, and OLP163) led to similar or stronger KIR2DL2 binding compared to positive control peptide GAL. (C) KIR2DL3 binding to 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells pre-incubated as indicated and expressed as percentage KIR2DL2 binding (% KIR2DL2+, N=3). KIR2DL3-Fc is engaged in presence of the same peptides (OLP 11, 30 and OLP163) as KIR2DL2 and at similar levels. (D) KIR2DL2 binding to 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells pulsed with control peptide GAL or the respective variants of OLP30, OLP34, and OLP163 (N=3). Binding was expressed as percentage KIR2DL2 binding (% KIR2DL2+). Three OLP163 variants (OLP163-9A, OLP163-9I and OLP163-9V) led to significantly higher binding of KIR2DL2 to 220-C*03:04 cells than their consensus sequence counterpart.

Point mutations in HLA-bound HIV-1 epitope result in enhanced KIR2DL2 binding to HLA- C*03:04

Functional studies of KIR2DL2/HLA-C*03:04 interactions and the crystal structure of KIR2DL2/HLA-C*03:04 have suggested that binding of KIR2DL2 to HLA-C*03:04 is affected by amino acid residues in positions 7 and 8 (P7, P8) of the HLA-bound 9-mer epitope [15, 24]. We therefore screened the seven selected epitopes for naturally occurring sequence variations, using the Los Alamos HIV-1 Sequence Database QuickAlign tool which includes amino acid sequences of more than 3,500 described HIV-1 variants (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/index). In addition to sequence variations in position 7 (P7) and position 8 (P8) of the epitopes, we also assessed variations at position 9 (P9), since for two peptides we used the better HLA-C*03:04-stabilizing 10-mer epitope instead of the corresponding 9-mers. Three of the seven HLA-C*03:04-presented epitopes exhibited variation at positions 7, 8, and/or 9. Table 1 shows the respective variant epitopes as well as the frequency of these sequence polymorphisms (%) within the >3,500 studied HIV-1 sequences contained in the Los Alamos Database. The consensus sequence epitopes and their variants shown in Table 1 did not significantly differ in their ability to stabilize HLA-C*03:04 expression on transfected 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells (supplemental figure 1).

Subsequent KIR2DL2-Fc binding assays were performed to assess the impact of the aforementioned variant epitopes on KIR2DL2 binding (figure 2D). Variant peptide OLP30-7I and all OLP34 variants allowed for less and insignificant binding when compared to the respective consensus sequence peptide variant (figure 2D). In contrast, the variant epitopes OLP163-9A, OLP163-9I, and especially OLP163-9V led to enhanced and significant engagement of KIR2DL2-Fc compared to the OLP163 consensus sequence (OLP163-CSeq). Altogether, we identified three (OLP11, OLP30, and OLP163) optimal HIV-1 p24 Gag HLA-C epitopes that possess major and minor naturally occurring variants that led to significant KIR2DL2 engagement to HLA-C*03:04.

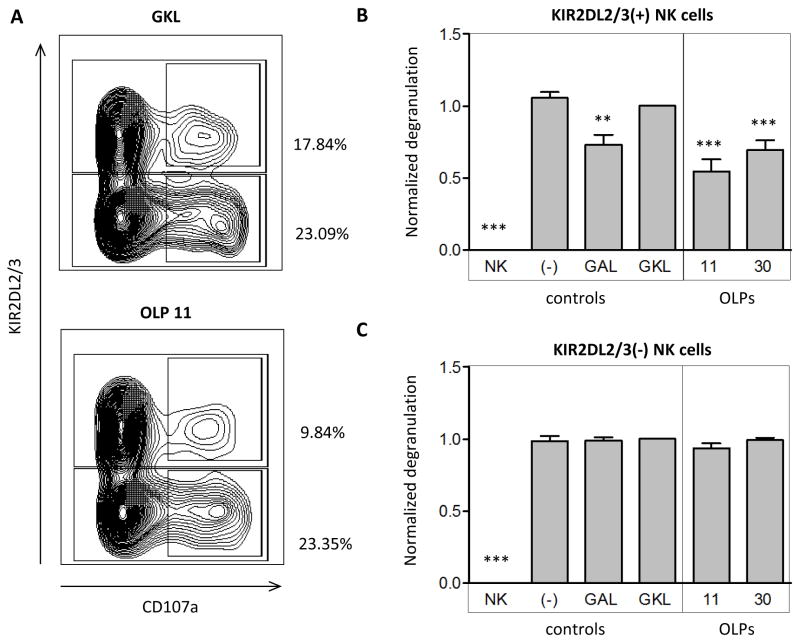

HLA-C*03:04-bound KIR2DL2-engaging epitopes can inhibit primary NK cell function

To determine the functional relevance of HIV-1-derived epitopes that enabled KIR2DL2 binding, NK cell degranulation assays were performed using primary NK cells derived from KIR2DL2+ individuals. Freshly isolated and purified NK cells were co-cultured with peptide-pulsed 221-ICP47-C*03:04 target cells. Target cells loaded with the positive control peptide GAL, OLP11, and OLP30, which potently engaged KIR2DL2-Fc, significantly inhibited KIR2DL2+ NK cell degranulation whereas target cells loaded with negative control peptide GKL did not (figure 3A and 3B). In contrast, the function of KIR2DL2- NK cells from the same individuals was not affected by the presence or absence of these peptides (Figure 3A and 3C). In conclusion, the naturally occurring HIV-1 Gag peptides OLP11 and OLP30 did not only strongly engage KIR2DL2-Fc, but also suppressed primary KIR2DL2+ NK cell function when presented by HLA-C*03:04, demonstrating a functional consequence of modulated KIR2DL2/HLA-C*03:04 interactions for NK cells.

Figure 3. Primary NK cell degranulation in co-culture with peptide-loaded target cells.

(A) Representative dotplots of primary NK cell degranulation (measured by CD107a expression) in co-culture with 221-ICP47-C*03:04 target cells pulsed with either GKL (GAVDPLLKL, negative control) or OLP11 (HQAISPRTL). Degranulation percentage (%) was expressed as CD107a+ fraction of either KIR2DL2+ or KIR2DL2- NK cell populations; (B-C) Normalized degranulation of KIR2DL2+ NK cells (B) and KIR2DL2- NK cells (C) in co-culture with no target cells or with 221-ICP47-C*03:04 target cells pulsed with either GAL (GAVDPPLAL, positive control), GKL (GAVDPLLKL, negative control), OLP11 (HQAISPRTL), or OLP30 (AFSPEVIPM). Normalized degranulation was calculated as followed: (%CD107a+ sample – background) / (%CD107a+ GKL – background), with background defined as the %CD107a+ of NK cell cultured without target cells (NK cells only). Target cells loaded with the positive control peptide GAL, OLP11, and OLP30 significantly inhibit KIR2DL2+ NK cell degranulation whereas target cells loaded with no peptide or negative control peptide GKL did not inhibit KIR2DL2+ NK cells degranulation (B). Degranulation of KIR2DL2- NK cells was not at all affected (C). Significance was calculated by repeated measures ANOVA, N=6.

Discussion

Binding of KIR to HLA class I regulates NK cell function in a manner that can be modulated by HLA-bound peptides. In order to investigate the influence of sequence variations in HLA-C*03:04-binding HIV-1 p24 Gag epitopes on KIR2DL2 binding, we first screened the entire HIV-1 p24 Gag sequence for epitopes that stabilized HLA-C expression on HLA-C*03:04-expressing 220 cells, and then assessed KIR2DL2 binding to HLA-C*03:04 presenting the selected optimal epitopes. Three out of seven consensus sequence-derived HLA-C*03:04-binding epitopes allowed for KIR2DL2-Fc binding and similarly engaged KIR2DL3. Subsequent testing of naturally occurring peptide variants of the identified HLA-C*03:04-binding HIV-1 epitopes revealed several additional KIR2DL2-Fc-engaging epitopes. Furthermore, engagement of KIR2DL2 by these HLA-C*03:04-presented HIV-1 peptides inhibited primary KIR2DL2+ NK cell function in vitro. Altogether, we identified several major and minor circulating variants of HLA-C*03:04-binding HIV-1 p24 Gag epitopes that engage KIR2DL2 and consequently inhibit KIR2DL2+ NK cell function.

In order to identify peptides within HIV-1 that bind to HLA-C*03:04 for subsequent assessment of KIR2DL2 binding, we initially performed HLA-C-stabilization assays using HLA-C*03:04-expressing, tapasin-deficient 220 cells, and identified seven epitopes that led to the strong HLA-C-specific DT9 staining, which reflects epitope binding to HLA-C. The optimal HLA-C*03:04 binding motif, X-A-(Q/A)-D-X-X-X-X-L was not present in every selected epitope. However, five of the seven selected 10mer epitopes contained a Leucine (L) towards the C-terminal end with a relatively small residue in the prior amino acid position, which is in line with the described binding motif for HLA-C*03:04 and previous studies [24]. Furthermore, we validated our experimentally determined HLA-C*03:04 binding results with an online prediction tool and a comparison to HIV-1 CTL epitope databases. All selected epitopes were predicted to serve as HLA-C*03:04 binders and predicted binding scores of the identified epitopes differed significantly from the 215 peptides that resulted in no or insignificant stabilization of HLA-C. Furthermore, three previously described p24 Gag HLA-C*03(:04)-restricted CTL epitopes were contained within the epitopes we identified, i.e. OLP11, 34, and 163 [35–42]. Further testing of the HLA-C*03:04 stabilizing capacities of 9-mers within the selected 10-mers showed a preference of HLA-C*03:04 for 9 amino-acid long peptide, also in concordance with previous studies [24]. Taken together, we identified several novel HLA-C*03:04-presented epitopes within HIV-1 p24 Gag, which were subsequently assessed to determine their impact on KIR2DL2 binding to HLA-C*03:04.

The interaction between KIR and HLA class I can be modulated by the sequence of the HLA-presented peptides. Consistent with this observation, we show that naturally occurring sequence variations in HIV-1 p24 Gag can promote KIR2DL2 binding to HLA-C*03:04, and identified an epitope (Gag295-304) for which the minor circulating variants allowed for enhanced binding of KIR2DL2 compared to the HIV-1 clade B consensus sequence epitope. In line with previously described structural data [15, 19] we also demonstrate that the residues towards the C-terminal end of the HLA class I bound peptide are crucial in modulation of KIR2DL2 binding. Yet, we could not reveal a common sequence pattern among the epitopes allowing for KIR2DL2 binding, nor did KIR2DL2-engaging epitopes meet previously postulated requirements [15]. Distinct KIR-engaging sequence requirements might not exist, as every HLA-epitope interaction is complex and provides unique amino acid size and/or charge requirements to engage KIR2DL2.

HIV-1 sequences within epitopes that engage KIR2DL2 may represent sequences selected to engage this inhibitory KIR in individuals expressing the corresponding HLA/KIR compound genotypes, leading to reduction of NK cell activation as we show for OLP11 (Gag144-152) and OLP30 (Gag163-171) in vitro. Recent studies have suggested that HIV-1 might adapt to NK cell-mediated immune pressure as there are several amino-acid polymorphisms within HIV-1 that are significantly associated with the expression of specific KIRs on a population level [44]. The p24 Gag peptide OLP163 (Gag295-304, DYVDRFFKTL) represents an interesting HLA-C*03:04-restricted epitope in this regard, given that previous studies [42] have demonstrated several mutations selected for in the 9th amino acid position of this epitope in HLA-C*03+ individuals. Here we show that these variants also allow for binding of the inhibitory NK cell receptor KIR2DL2; in particular the T303V variant of this epitope (OLP163-V, DYVDRFFKVL), which did not mediate escape from epitope-specific CD8+ T cells in the previous study by Honeyborne et al. [42]. Selection of these escape variants might therefore represent a potential mechanism by which HIV-1 evades NK cell-mediated killing.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that sequence variations in HLA-C*03:04-presented HIV-1 epitopes can promote or abrogate KIR2DL2 binding to HLA-C*03:04, and that minor circulating variants of HLA-C*03:04-binding epitopes can reconstitute the binding of this inhibitory NK cell receptor and affect primary NK cell function. Further studies will be required to determine whether these sequence polymorphisms are selected for during infection and if they can allow HIV-1 to evade recognition by KIR2DL2+ NK cells.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental figure 1. HLA-C*03:04 stabilization on 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells pulsed with no peptide, GKL, GAL, and OLP11.Representative histograms of HLA-C stabilization on 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells in the presence of no peptide (solid grey), control peptide GKL (GAVDPLLKL, dotted line), control peptide GAL (GAVDPLLAL, dashed line) and OLP11 (HQAISPRTL, continuous line).

Supplemental figure 2. HLA-C*03:04 stabilization on 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells pulsed with variants of OLP30, OLP34, and OLP163.221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells were stained with a pan-HLA antibody (W6/32-APC) after peptide pre-incubation as indicated. Variant epitopes of OLP30, OLP34, and OLP163 did not significantly differ from their consensus sequence counterpart in their ability to stabilize HLA-C*03:04.

Supplemental table 1. All 222 HIV-1 p24 Gag overlapping peptides (OLPs

Acknowledgments

Conceived and designed the experiments: NHvT, AH, WFGB, CK, MA. Performed the experiments: NHvT and AH. Analyzed the data: NHvT, AH. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: CB, TS, MC, DE, JS. Participated in discussion on the data and commented on the manuscript: NHvT, AH, CK, WFGB, JS, LF, CB, MC, DE, DvB, MA. Wrote the paper: NHvT, MA.

Source of funding

This study was supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (http://www.ddcf.org/), the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard (http://www.ragoninstitute.org/index.html), and the NIH (http://www.nih.gov/) (R01 AI066031). This project has partly been funded with federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research (http://web.ncifcrf.gov/, contract No. HHSN261200800001E), the Intramural Research Program of the NIH (Frederick National Lab, Center for Cancer Research), and Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) (http://cfar.globalhealth.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do). CFAR is an NIH funded program (P30 AI060354), which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, NCCAM, FIC, and OAR. Nienke H. van Teijlingen was supported by the Huygens Scholarship Programme (http://www.nuffic.nl/home). Angelique Hölzemer was supported by a German Academic Exchange (DAAD) scholarship and the Köln Fortune Programm. Christian Körner and Lena Fadda were both supported by a Ragon Fellowship of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard. David T. Evans was supported by NIH R01 AI095098. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Duplicate publications

Data in this manuscript have not previously been published. However, the data have in part been presented on a poster at the AIDS Vaccine Conference 2012 (Boston, MA, USA).

References

- 1.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Fuchs A, Colonna M, Caligiuri MA. NK cell and DC interactions. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews DM, Estcourt MJ, Andoniou CE, Wikstrom ME, Khong A, Voigt V, et al. Innate immunity defines the capacity of antiviral T cells to limit persistent infection. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1333–1343. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waggoner SN, Cornberg M, Selin LK, Welsh RM. Natural killer cells act as rheostats modulating antiviral T cells. Nature. 2011;481:394–398. doi: 10.1038/nature10624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jost S, Altfeld M. Control of human viral infections by natural killer cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:163–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin MP, Gao X, Lee JH, Nelson GW, Detels R, Goedert JJ, et al. Epistatic interaction between KIR3DS1 and HLA-B delays the progression to AIDS. Nat Genet. 2002;31:429–434. doi: 10.1038/ng934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin MP, Qi Y, Gao X, Yamada E, Martin JN, Pereyra F, et al. Innate partnership of HLA-B and KIR3DL1 subtypes against HIV-1. Nat Genet. 2007;39:733–740. doi: 10.1038/ng2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alter G, Rihn S, Walter K, Nolting A, Martin M, Rosenberg ES, et al. HLA class I subtype-dependent expansion of KIR3DS1+ and KIR3DL1+ NK cells during acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2009;83:6798–6805. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00256-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long BR, Ndhlovu LC, Oksenberg JR, Lanier LL, Hecht FM, Nixon DF, et al. Conferral of enhanced natural killer cell function by KIR3DS1 in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2008;82:4785–4792. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02449-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alter G, Martin MP, Teigen N, Carr WH, Suscovich TJ, Schneidewind A, et al. Differential natural killer cell-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 replication based on distinct KIR/HLA subtypes. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3027–3036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norman PJ, Stephens HA, Verity DH, Chandanayingyong D, Vaughan RW. Distribution of natural killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor sequences in three ethnic groups. Immunogenetics. 2001;52:195–205. doi: 10.1007/s002510000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen GB, Gandhi RT, Davis DM, Mandelboim O, Chen BK, Strominger JL, et al. The selective downregulation of class I major histocompatibility complex proteins by HIV-1 protects HIV-infected cells from NK cells. Immunity. 1999;10:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fellay J, Shianna KV, Ge D, Colombo S, Ledergerber B, Weale M, et al. A whole-genome association study of major determinants for host control of HIV–1. Science. 2007;317:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.1143767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International HIV Controllers Study. Pereyra F, Jia X, McLaren PJ, Telenti A, de Bakker PI, et al. The major genetic determinants of HIV-1 control affect HLA class I peptide presentation. Science. 2010;330:1551–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1195271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Apps R, Qi Y, Carlson JM, Chen H, Gao X, Thomas R, et al. Influence of HLA-C expression level on HIV control. Science. 2013;340:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1232685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyington JC, Motyka SA, Schuck P, Brooks AG, Sun PD. Crystal structure of an NK cell immunoglobulin-like receptor in complex with its class I MHC ligand. Nature. 2000;405:537–543. doi: 10.1038/35014520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan QR, Long EO, Wiley DC. Crystal structure of the human natural killer cell inhibitory receptor KIR2DL1-HLA-Cw4 complex. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:452–460. doi: 10.1038/87766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saulquin X, Gastinel LN, Vivier E. Crystal structure of the human natural killer cell activating receptor KIR2DS2 (CD158j) J Exp Med. 2003;197:933–938. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart-Jones GB, di Gleria K, Kollnberger S, McMichael AJ, Jones EY, Bowness P. Crystal structures and KIR3DL1 recognition of three immunodominant viral peptides complexed to HLA-B*2705. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:341–351. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vivian JP, Duncan RC, Berry R, O'Connor GM, Reid HH, Beddoe T, et al. Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL1-mediated recognition of human leukocyte antigen B. Nature. 2011;479:401–405. doi: 10.1038/nature10517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malnati MS, Peruzzi M, Parker KC, Biddison WE, Ciccone E, Moretta A, et al. Peptide specificity in the recognition of MHC class I by natural killer cell clones. Science. 1995;267:1016–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.7863326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peruzzi M, Wagtmann N, Long EO. A p70 killer cell inhibitory receptor specific for several HLA-B allotypes discriminates among peptides bound to HLA-B*2705. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1585–1590. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandelboim O, Wilson SB, Vales-Gomez M, Reyburn HT, Strominger JL. Self and viral peptides can initiate lysis by autologous natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94 :4604–4609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajagopalan S, Long EO. The direct binding of a p58 killer cell inhibitory receptor to human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw4 exhibits peptide selectivity. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1523–1528. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zappacosta F, Borrego F, Brooks AG, Parker KC, Coligan JE. Peptides isolated from HLA-Cw*0304 confer different degrees of protection from natural killer cell-mediated lysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6313–6318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vales-Gomez M, Reyburn HT, Erskine RA, Strominger J. Differential binding to HLA-C of p50-activating and p58-inhibitory natural killer cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95 :14326–14331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maenaka K, Juji T, Nakayama T, Wyer JR, Gao GF, Maenaka T, et al. Killer cell immunoglobulin receptors and T cell receptors bind peptide-major histocompatibility complex class I with distinct thermodynamic and kinetic properties. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28329–28334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansasuta P, Dong T, Thananchai H, Weekes M, Willberg C, Aldemir H, et al. Recognition of HLA-A3 and HLA-A11 by KIR3DL2 is peptide-specific. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1673–1679. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart CA, Laugier-Anfossi F, Vely F, Saulquin X, Riedmuller J, Tisserant A, et al. Recognition of peptide-MHC class I complexes by activating killer immunoglobulin-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13224–13229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503594102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thananchai H, Gillespie G, Martin MP, Bashirova A, Yawata N, Yawata M, et al. Cutting Edge: Allele-specific and peptide-dependent interactions between KIR3DL1 and HLA-A and HLA-B. J Immunol. 2007;178:33–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fadda L, Borhis G, Ahmed P, Cheent K, Pageon SV, Cazaly A, et al. Peptide antagonism as a mechanism for NK cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10160–10165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913745107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fadda L, Korner C, Kumar S, van Teijlingen NH, Piechocka-Trocha A, Carrington M, et al. HLA-Cw*0102-restricted HIV-1 p24 epitope variants can modulate the binding of the inhibitory KIR2DL2 receptor and primary NK cell function. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002805. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamya P, Boulet S, Tsoukas CM, Routy JP, Thomas R, Cote P, et al. Receptor-ligand requirements for increased NK cell polyfunctional potential in slow progressors infected with HIV-1 coexpressing KIR3DL1*h/*y and HLA-B*57. J Virol. 2011;85:5949–5960. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02652-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenwood R, Shimizu Y, Sekhon GS, DeMars R. Novel allele-specific, post-translational reduction in HLA class I surface expression in a mutant human B cell line. J Immunol. 1994;153:5525–5536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braud VM, Allan DS, Wilson D, McMichael AJ. TAP- and tapasin-dependent HLA-E surface expression correlates with the binding of an MHC class I leader peptide. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Littaua RA, Oldstone MB, Takeda A, Debouck C, Wong JT, Tuazon CU, et al. An HLA-C-restricted CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte clone recognizes a highly conserved epitope on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag. J Virol. 1991;65:4051–4056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4051-4056.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaul R, Dong T, Plummer FA, Kimani J, Rostron T, Kiama P, et al. CD8+ lymphocytes respond to different HIV epitopes in seronegative and infected subjects. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1303–1310. doi: 10.1172/JCI12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daucher M, Price DA, Brenchley JM, Lamoreaux L, Metcalf JA, Rehm C, et al. Virological outcome after structured interruption of antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus infection is associated with the functional profile of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. J Virol. 2008;82:4102–4114. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02212-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiepiela P, Leslie AJ, Honeyborne I, Ramduth D, Thobakgale C, Chetty S, et al. Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature. 2004;432:769–775. doi: 10.1038/nature03113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Currier JR, Visawapoka U, Tovanabutra S, Mason CJ, Birx DL, McCutchan FE, et al. CTL epitope distribution patterns in the Gag and Nef proteins of HIV-1 from subtype A infected subjects in Kenya: use of multiple peptide sets increases the detectable breadth of the CTL response. BMC Immunol. 2006;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiepiela P, Ngumbela K, Thobakgale C, Ramduth D, Honeyborne I, Moodley E, et al. CD8+ T-cell responses to different HIV proteins have discordant associations with viral load. Nat Med. 2007;13:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nm1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Day CL, Kiepiela P, Leslie AJ, van der Stok M, Nair K, Ismail N, et al. Proliferative capacity of epitope-specific CD8 T-cell responses is inversely related to viral load in chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2007;81:434–438. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01754-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Honeyborne I, Codoner FM, Leslie A, Tudor-Williams G, Luzzi G, Ndung'u T, et al. HLA-Cw*03-restricted CD8+ T-cell responses targeting the HIV-1 gag major homology region drive virus immune escape and fitness constraints compensated for by intracodon variation. J Virol. 2010;84:11279–11288. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01144-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masemola AM, Mashishi TN, Khoury G, Bredell H, Paximadis M, Mathebula T, et al. Novel and promiscuous CTL epitopes in conserved regions of Gag targeted by individuals with early subtype C HIV type 1 infection from southern Africa. J Immunol. 2004;173:4607–4617. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alter G, Heckerman D, Schneidewind A, Fadda L, Kadie CM, Carlson JM, et al. HIV-1 adaptation to NK-cell-mediated immune pressure. Nature. 2011;476:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature10237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental figure 1. HLA-C*03:04 stabilization on 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells pulsed with no peptide, GKL, GAL, and OLP11.Representative histograms of HLA-C stabilization on 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells in the presence of no peptide (solid grey), control peptide GKL (GAVDPLLKL, dotted line), control peptide GAL (GAVDPLLAL, dashed line) and OLP11 (HQAISPRTL, continuous line).

Supplemental figure 2. HLA-C*03:04 stabilization on 221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells pulsed with variants of OLP30, OLP34, and OLP163.221-ICP47-C*03:04 cells were stained with a pan-HLA antibody (W6/32-APC) after peptide pre-incubation as indicated. Variant epitopes of OLP30, OLP34, and OLP163 did not significantly differ from their consensus sequence counterpart in their ability to stabilize HLA-C*03:04.

Supplemental table 1. All 222 HIV-1 p24 Gag overlapping peptides (OLPs