Abstract

Purpose

Deregulated expression of microRNAs (miRNAs) has been demonstrated in multiple myeloma (MM). A promising strategy to achieve a therapeutic effect by targeting the miRNA regulatory network is to enforce the expression of miRNAs that act as tumor suppressor genes, such as miR-34a.

Experimental Design

Here, we investigated the therapeutic potential of synthetic miR-34a against human MM cells in vitro and in vivo.

Results

Either transient expression of miR-34a synthetic mimics or lentivirus-based miR-34a-stable enforced expression triggered growth inhibition and apoptosis in MM cells in vitro. Synthetic miR-34a downregulated canonic targets BCL2, CDK6 and NOTCH1 at both the mRNA and protein level. Lentiviral vector-transduced MM xenografts with constitutive miR-34a expression showed high growth inhibition in SCID mice. The anti-MM activity of lipidic-formulated miR-34a was further demonstrated in vivo in two different experimental settings: i) SCID mice bearing non-transduced MM xenografts; and ii) SCID-synth-hu mice implanted with synthetic 3D scaffolds reconstituted with human bone marrow stromal cells and then engrafted with human MM cells. Relevant tumor growth inhibition and survival improvement were observed in mice bearing TP53-mutated MM xenografts treated with miR-34a mimics in the absence of systemic toxicity.

Conclusions

Our findings provide a proof-of-principle that formulated synthetic miR-34a has therapeutic activity in preclinical models and support a framework for development of miR-34a-based treatment strategies in MM patients.

Keywords: miR-34a, microRNA, miRNAs, multiple myeloma, plasma cell leukemia, SCID-synth-hu model

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common hematologic malignancy in Western Countries. Despite advances in the understanding of MM pathobiology and development of novel therapeutic strategies, available treatments fail to cure the disease in most cases (1–3). A variety of genetic and epigenetic abnormalities characterizes the MM multistep transformation process occurring in the bone marrow (BM), where the microenvironment (BMM) plays a key supportive role for growth, survival, and drug resistance of tumor cells (1, 4–6). All these alterations can dramatically deregulate the plasma cell growth and the network of molecular interactions within the human BMM.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs of 19–25 nt that play a critical role in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression (7, 8). As a result of imperfect pairing with target mRNAs, they may cause repression of translation or degradation of mRNAs. These small molecules are important modulators of key regulatory cellular pathways and may play a relevant role in tumorigenesis (9), since deregulated miRNAs can act as oncogenes (Onco-miRNAs) or tumor-suppressors (TS-miRNAs) (10, 11). Therefore, miRNAs have elicited a growing interest in the cancer research community as new potential tumor cell targets (Onco-miRNAs) or as new potential anticancer agents (TS-miRNAs), due to their ability to target multiple genes in the context of signaling networks involved in cancer promotion or repression (12). Specifically, miRNAs are variably involved in the pathogenesis of human MM and several miRNAs have been found to be abnormally upregulated or downregulated in primary MM cells or cell lines, as recently reviewed (13–16). Although the biological role of miRNAs in the pathogenesis of MM is presently well documented by several studies, only few reports support the notion that miRNAs have a potential in MM therapy (16–18). For example, Roccaro et al (17) demonstrated a downregulation of 15a/16 miRNAs in MM. Since these miRNAs appear to be negative regulators of MM cell proliferation by inhibiting AKT3, ribosomal protein S6, MAP kinases, and NF-kappaB activator MAP3KIP3, it was suggested that the reconstitution of normal miRNA expression could represent a MM treatment. More recently, Pichiorri et al (18) demonstrated a MM-specific miRNA signature characterized by miR-192, 194, and 215 downregulation in a subset of newly diagnosed MMs. These miRNAs are transcriptionally activated by TP53 and are also positive regulators of TP53, thereby producing a loop of major relevance in the biology of MM which can be a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

Among miRNAs frequently deregulated in human cancer, miR-34a is of special interest in the field of miRNA therapeutics (19–21). Specifically, hypermethylation of miR-34a promoter has been found in MM patient cells and MM cell lines, but not in normal counterparts (22). miR-34a, first described as potential TS-miRNA (23), belongs to a miRNA family including miR-34b and miR-34c and is encoded by a gene located on 1p36 (21). miR-34a transcription is induced by TP53 in response to cell stress, thereby promoting apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and senescence (24–29). Recent reports show that induction of miR-34a expression could overcome TP53 loss of function in pancreatic cancer cells (22, 30). Although some of these events may, at least in part, be related to the positive feedback loop that links miR-34a to TP53 (31), some reports suggest that the anti-tumor activity of miR-34a might be independent of TP53 mutational status (32, 33). Moreover, in one report miR-34a anti-tumor activity is not limited to cell lines with reduced endogenous miR-34a expression levels, but it is also effective in cells with an apparently normal miRNA expression (33).

In this study, we investigated a novel anti-MM therapeutic strategy based on miR-34a. The main challenges for an effective miRNA-based therapy include the effective delivery of the appropriate miRNA to and its uptake by malignant plasma cells in their specific microenvironment without off-target effects. Therefore, we characterized the in vitro and in vivo anti-MM activity and molecular perturbations produced by synthetic miR-34a mimics. For in vivo studies, synthetic miR-34a mimics were formulated in a novel Neutral Lipid Emulsion (NLE)(33, 34) delivery system and, to explore the clinical translatability of experimental findings, we examined the antitumor activity in murine xenograft models of human MM. Our findings support the development of formulated miR-34a as an experimental new agent for the treatment of MM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and primary cultures

NCI-H929, U266 and SKMM1 MM cell lines were available within our research network, while the RPMI-8226 MM cell line was purchased from Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale (I.Z.S.L.E.R., Brescia, Italy). OPM1, DOX-6 and LR-5 MM cell lines were kindly provided by Dr Eduard Thomson (University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, USA), MM1S was purchased by American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA), INA-6 was provided by Dr Renate Burger (University of Erlangen-Nuernberg, Erlangen, Germany) (35, 36). Human bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) were obtained by long term culture of bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMCs), as previously described (37–39). Primary CD138+ patient MM cells were obtained by Ficoll gradient separation followed by positive selection from patient BM aspirates, using CD138 MicroBeads antibody (MACS, Milteny Biotec). For co-culture, 1×105 CD138+ cells were seeded on 5×104 BMSCs, which had been cultured for 24–48 hours in 96 well plates.

In vitro transfection of MM cells with synthetic miR-34a

Synthetic pre-miRNAs were purchased from Ambion (Applied Biosystems). 1×106 cells were electroporated with scrambled (miR-NC) or synthetic pre-miR-34a (miR-34a) at a final concentration of 100nM, using Neon® Transfection System (Invitrogen) with 1050 V, 30 ms, 1 pulse. Cell transfection efficiency was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis of FAM™-dye-labeled synthetic miRNA inhibitor (Invitrogen) transfection.

Quantitative real-time amplification of miRNAs and mRNAs

Total RNA from MM cells was prepared with the TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Oligo-dT-primed cDNA was obtained using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). The single-tube TaqMan miRNA assays were used to detect and quantify mature miR-34a and target mRNAs, according to the manufacturer’s instructions by the use of the StepOne Thermocycler and the sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). miR-34a and mRNAs were normalized on RNU44 (40) and GAPDH (Ambion), respectively. Comparative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed in triplicate, including no-template controls. Relative expression was calculated using the comparative cross threshold (Ct) method (41).

Apoptosis analysis

MM cells transfected or transduced with miR-34a or scrambled sequence/empty vector were harvested and treated with Annexin V/7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) solution (BD Pharmingen) at 24, 48 and 72 hours, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Animals and in vivo models of human MM

Male CB-17 severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice (6- to 8-weeks old; Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis) were housed and monitored in our Animal Research Facility. All experimental procedures and protocols had been approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee (Magna Graecia University) and conducted according to protocols approved by the National Directorate of Veterinary Services (Italy). In accordance with institutional guidelines, mice were sacrificed when their tumors reached 2 cm in diameter or in the event of paralysis or major compromise in their quality of life, to prevent unnecessary suffering. For our study, we use 3 different models of human MM, including i) SCID mice bearing lentiviral vector-transduced MM xenografts; ii) SCID mice bearing subcutaneous (sc) MM xenografts (42); and iii) SCID mice implanted with a 3D polymeric scaffold previously reconstituted with human bone marrow stromal cells and then injected with human MM cells (SCID-synth-hu)(43–45).

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test, two-tailed, and Log rank test were used to calculate all reported P-values using GraphPad software (www.graphpad.com). Graphs were obtained using SigmaPlot version 11.0

RESULTS

Expression of miR-34a in MM cells

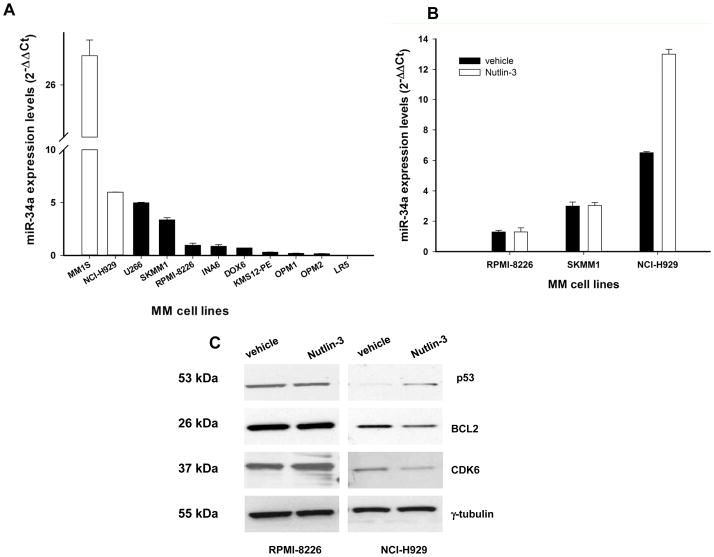

We first evaluated the miR-34a expression in a series of 11 MM cell lines by q-RT-PCR (for details about MM cell lines, see supplemental methods). Among these, 2 wild-type TP53 cell lines (MM1S and NCI-H929) showed significantly higher miR-34a expression as compared to TP53-mutated MM cells (U266, SKMM1, RPMI-8226, INA-6, DOX6, KMS12-PE, OPM1, OPM2 and LR5) (Figure 1A). We next explored if the positive miR-34a-TP53 loop was functional in MM cells. Specifically, we treated the TP53 mutated SKMM1 and RPMI-8226 cells, as well as the TP53 wild-type NCI-H929 cell line with nutlin-3, which blocks the TP53-MDM2 inhibitory interaction and thereby induces the expression of TP53-regulated genes (46). As expected, nutlin-3 treatment induced miR-34a expression in TP53 wild-type cells (NCI-H929) but not in TP53-mutated SKMM1 and RPMI-8226 cells, as evaluated by q-RT-PCR (P<0.05, Figure 1B). Nutlin-3-induced upregulation of miR-34a in turn reduced expression of miR-34a canonical targets, such as BCL2 and CDK6 proteins (for western blotting procedures see supplemental methods). As expected, this effect was not demonstrable in TP53-mutated RPMI-8226 cells (Figure 1C). These findings suggest that miR-34a expression is positively modulated by a functional loop in TP53 wild-type MM cells. An additional finding reinforcing the role of TP53 in regulation of miR-34a expression is the significantly downregulated expression of miR-34a in a microarray dataset of TP53-mutated CD138+ primary MM cells as compared to TP53-wild-type MM cells (Lionetti M. and Neri A., unpublished results).

Figure 1. miR-34a expression and nutlin-3 response in MM cell lines.

A) q-RT-PCR analysis of miR-34a using total RNA from 2 MM cell lines bearing wild type TP53 and 9 MM cell lines with mutated TP53. B) q-RT-PCR of miR-34a in nutlin-3-treated (10 μM) RPMI-8226, SKMM1 (TP53 mutated) and NCI-H929 (TP53 wild-type) cells. Raw Ct values were normalized to RNU44 housekeeping snoRNA and expressed as ΔΔCt values calculated respect to miR-34a levels in RPMI-8226 cells, using the comparative cross threshold method. Values represent mean observed in four different experiment ±SD. miR-34a expression was significantly higher in TP53-wt versus TP53-mutated MM cells (P=0.045). C) Western blotting of BCL2, CDK6 and TP53 protein in TP53 mutated RPMI-8226 and TP53 wild-type NCI-H929 cells 24 hours after nutlin-3-treatment. The protein loading control was γ-tubulin. A representative of three experiments is shown.

In vitro enforced expression of miR-34a in MM cells

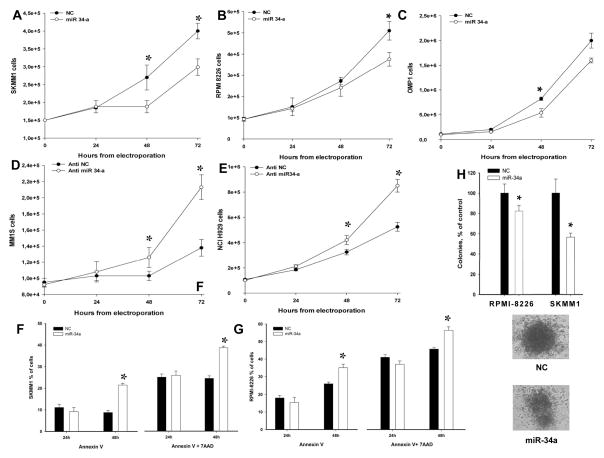

To evaluate the biological effects of miR-34a, we transfected low-miR-34a MM cell lines with synthetic miR-34a or miR-NC by electroporation. The transfection efficiency was 98%, as determined by FAM™-dye-labeled oligonucleotide transfection and subsequent flow cytometric analysis (supplemental Figure S1A). In a parallel experiment, the biological activity of transfected synthetic miRNA was assessed by downregulation of PTK9 mRNA induced by miR-1 (supplemental Figure S1B). The antiproliferative effect induced by miR-34a in MM cells was evaluated by Trypan Blue exclusion assay (procedure available in supplemental methods) after synthetic miR-34a or miR-NC transfection. We observed a significant growth inhibition in TP53-mutated SKMM1 (P<0.005, Figure 2A), RPMI-8226 (P<0.05, Figure 2B) and OPM1 (P<0.005, Figure 2C) MM cells. On the other hand, TP53-wild type MM1S and NCI-H929 cells, where a functional TP53-miR34a loop is operative, were not inhibited by miR-34a (supplemental Figure S2), while transfection of anti-miR-34a oligonucleotides indeed produced a growth stimulus in these cells (Figure 2D and E). These data further confirm miR-34a role as a negative regulator of MM cell growth in TP53-wild type cells, and strengthen the rationale of our experimental strategy of enforced expression in TP53-mutated MM cells.

Figure 2. miR-34a has anti-proliferative activity and induces apoptosis in MM cell lines.

Cell growth analysis of SKMM1 (A), RPMI-8226 (B) or OPM1 (C) cells transfected with miR-34a or miR-NC oligonucleotide control. Average ±SD values of three independent experiments are plotted. P-values calculated by Student’s t test, two-tailed, at 48 and 72 hours, respectively, after transfection, are: 0.01 and 0.005 for SKMM1; 0.001 and 0.05 for RPMI-8226; 0.006 and 0.008 for OPM1. Cell growth analysis of MM1S (D) and NCI-H929 (E) cells transfected with miR-34a inhibitor (anti-miR-34a, Life Technologies AM11030) and anti-miR-scrambled inhibitor (NC, Life Technologies AM17010) oligonucleotide control. Average ±SD values of three independent experiments are plotted. P-values calculated by Student’s t test, two-tailed, were 0.04 and 0.002 for MM1S cells at 48 and 72 hours after transfection; and 0.04, 0.01 and 0.0008 for NCI-H929 cells at 24, 48 and 72 hours after transfection. Annexin V/7-AAD analysis of SKMM1 (F) and RPMI-8226 (G) cells after transfection with synthetic anti-miR-34a or control. Results are shown as percentage of apoptotic cells. Data are the average ±SD of 3 independent experiments. H) Colony formation assay using RPMI-8226 and SKMM1 cells. Cells were transfected with synthetic miR-34a or miR-NC by electroporation in triplicate, and then seeded at 2000 cells per 18 well plate in methyl cellulose-based medium. After two weeks, colony formation capacity was evaluated by counting colonies including > 100 cells. Means ± SE for three independent experiments are indicated. In all the experiments, P-value was ≤ 0.03 comparing miR-34a versus NC. A representative image of miR-34a and NC SKMM1 colonies shows homogeneous features of colonies formed by transfected cells with miR-NC, whereas cells transfected with miR-34a form irregular heterogeneous colonies.

We next investigated the induction of apoptosis by Annexin V/7-AAD assay. An increase of apoptotic cell death was observed in TP53-mutated cells following transfection with miR-34a, but not with miR-NC, after 48 hours (Figure 2F and G), that was more evident in SKMM1 cells. In contrast, this effect was not observed in TP53 wild-type cells (data not shown). To further explore the anti-MM effects induced by miR-34a, we carried out a clonogenic assay to study the colony formation activity of transiently transfected cells. We found a 45% and 20% reduced SKMM1 and RPMI-8226 colony formation, respectively, 14 days after transfection (Figure 2H). These findings indicate that miR-34a inhibits clonogenic properties of MM cells.

In vitro effect of MM cell transduction with lentiviral miR-34a expression vector

In order to achieve stable expression of miR-34a, the feline immunodeficiency lentiviral miR-34a expression vector was used to infect MM cells (for details see supplemental methods). About 97% transduction efficiency was demonstrated by flow cytometric GFP analysis (supplemental Figure S3). As shown in supplemental Figure S3A, the stable expression of miR-34a affected proliferation of SKMM1 cells in a time-dependent manner, as demonstrated by MTS assay. Consistently, we detected a 2-fold increase of early and late apoptosis 48h after transduction with miR-34a, as evidenced by Annexin/7-AAD assay (supplemental Figure S4B). Moreover, the miR-34a expression levels, analyzed by q-RT-PCR after lentivirus infection, showed 3-fold increase in pMIF-34a compared to pMIF empty-vector transduced cells (supplemental Figure S4C). These findings demonstrated that lentivirus transduction of miR-34a results in a significant anti-MM effect in vitro.

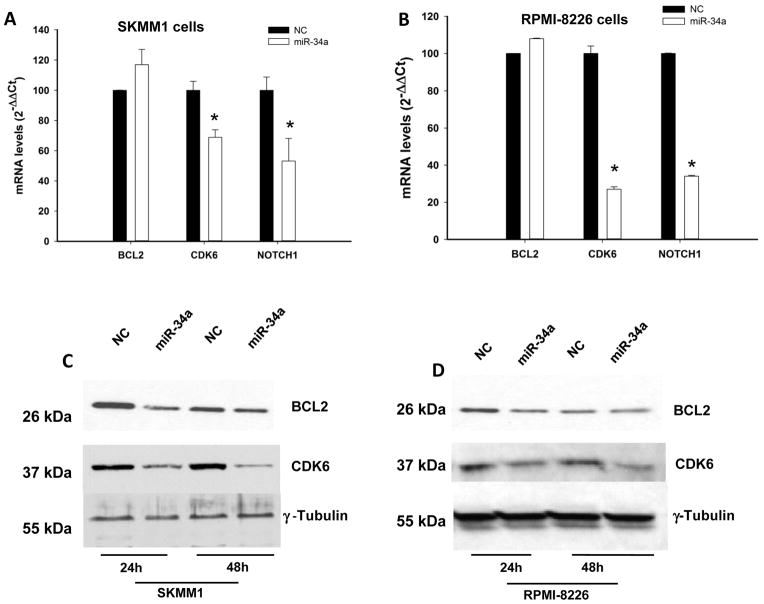

Downregulation of validated miR-34a targets in MM cell lines

To investigate whether genes known to be regulated by miR-34a were modulated by exogenous synthetic mimics, we analyzed BCL2, CDK6 and NOTCH1 mRNA levels by q-RT-PCR in miR-34a-transfected SKMM1 and RPMI-8226 cells. As shown in Figure 3A and B, we detected a significant downregulation of CDK6 and NOTCH1 mRNA expression 24 hours after cell transfection. This effect occurred together with downmodulation of CDK6 and BCL2 proteins evaluated by Western blot analysis (Figure 3C and D). Altogether, these results demonstrate that synthetic miR-34a activity modulates validated targets.

Figure 3. Molecular effects induced by transient expression of miR-34a in MM cells.

q-RT-PCR of BCL2, CDK6 and NOTCH1 after transfection with synthetic miR-34a or miR-NC in SKMM1 (A) and RPMI-8226 (B) cells. The results are shown as average mRNA expression after normalization with GAPDH and ΔΔCt calculations. Data represent the average ±SD of 3 independent experiments. Western blotting of BCL2 and CDK6 protein in SKMM1 (C) and RPMI-8226 (D) cells 24 and 48 hours after transfection with synthetic miR-34a or scrambled oligonucleotides (NC). The protein loading control was γ-tubulin. Experiments were performed in triplicate. miR-34a effects on protein levels reached statistical significance (P<0.05) at all time points.

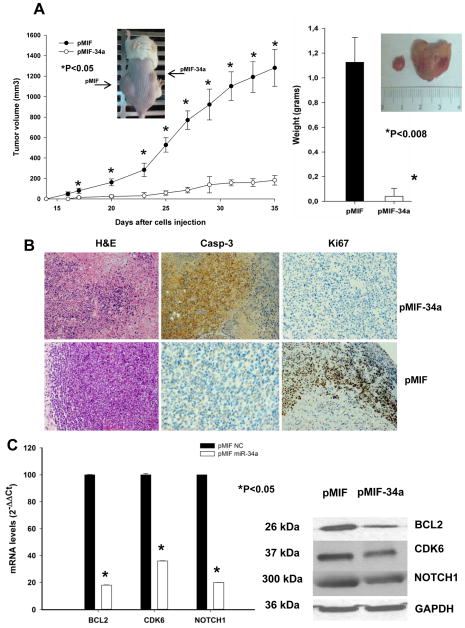

miR-34a lentiviral transduction inhibits MM xenograft formation in SCID mice

In the in vivo studies, we examined the effect of transduced miR-34a on the tumorigenic potential of TP53-mutated MM cells engrafted in SCID mice (for in vivo experiments see supplemental methods). As shown in Figure 4A, enhanced expression of miR-34a caused a significant inhibition (P<0.05) of tumor formation. In addition, the average size of miR-34a transduced-tumors was significantly (P=0.008) lower compared to control group. Quantitative analysis of miR-34a levels in retrieved tumors confirmed a more than 3-fold increase in pMIF-34a-transduced tumors (supplemental Figure S5A). Histological and immunohistochemical analysis of excised pMIF-34a tumors disclosed large areas of necrosis with abundant nuclear debris (“dustlike” nuclear fragments, Figure 4B). Moreover, few viable cells at the tumor periphery exhibited cleaved caspase-3 and lower expression of Ki-67, indicating that miR-34a expression inhibits proliferation and stimulates the apoptotic cascade in SKMM1 xenografts. Analysis of miR-34a targets at mRNA and protein levels showed that lentiviral-mediated ectopic expression of miR-34a induced BCL2, CDK6 and NOTCH1 downregulation in pMIF-34a-transduced tumors (Figure 4C). Although BCL2 mRNA was downregulated in retrieved tumors, electroporation of miR-34a was unable to produce the same effect in vitro (Figure 3). Based on these findings, we suggest that long term exposure as in costitutive in vivo xenografts is required to reduce BCL2 mRNA level, while a short term exposure is sufficient to impair BCL2 protein synthesis. All together, these findings indicate miR-34a-dependent regulation of canonical targets BCL2, CDK6 and NOTCH1 in vivo.

Figure 4. In vivo activity of miR-34a stably expressed in MM cells.

A) In vivo tumor formation of miR-34a stably expressed in MM xenografts. Tumor volumes were measured starting day 14 after cell injection (5 × 106 pMIF-34a-SKMM1 in the right flank or pMIF-SKMM1 in the left flank) in a cohort of 10 CB-17 SCID mice. Following the detection of tumors, measurements were assessed by an electronic caliper in two dimensions every 2–3 days until the date of sacrifice or death of the first animal. The tumor volume was calculated as detailed in methods. A representative mouse image is inserted in the graph. Tumor weight averages between pMIF-34a-SKMM1 or pMIF-SKMM1 xenografts retrieved from animals at the end of experiments show a significant difference between miR-34a transduced tumors versus controls (P=0.008; right panel). Means ± SD weight in grams are shown. P-value was calculated by Student’s t test, two tailed, of pMIF-34a versus pMIF tumor volumes. A representative image (insert) of a miR-34a retrieved tumor (left) versus control (right) is shown. B) Histologies and immunohistochemistry staining directed against Ki-67 and caspase-3 in pMIF-34a-SKMM1 or pMIF-SKMM1 tumors. Histologic and immunohistochemistry micrographs are at 20-fold magnification (H&E) and 40-fold magnification (Casp-3 and Ki-67), respectively. C) Quantitative analysis of BCL2, CDK6 and NOTCH1 mRNA (left panel) and protein (right panel) levels in retrieved pMIF-34a-SKMM1 or pMIF-SKMM1 tumors. The mRNA expression levels are shown as average after normalization with GAPDH and ΔΔCt calculations. Western blot analysis in retrieved tumors was performed as described in supplemental methods. The protein loading control was GAPDH. Experiments were performed in triplicate. miR-34a effects on protein levels reached statistical significance (P<0.05).

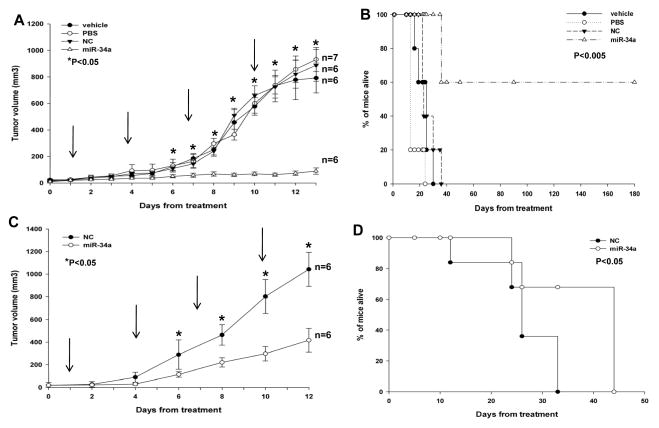

Inhibition of MM xenografts in SCID mice by intratumoral delivery of formulated miR-34a

We next investigated the effect of miR-34a treatment on MM xenograft growth in SCID mice. miR-34a or miR-NC were administered with NLE particles, a formulation specifically designed for systemic delivery of oligonucleotides in vivo (33, 34). A highly significant (P<0.0001) inhibition of tumor growth was detected following 4 injections (3 days apart) of miR-34a formulated in NLE particles in SKMM1 xenografts (Figure 5A). Importantly, after 21 days, we observed complete tumor regression in 50% of mice treated with formulated miR-34a mimics. Furthermore, we observed a dramatic prolongation of survival (P=0.0009) of mice treated with miR-34a mimics compared to control groups, with 3 mice still surviving at 6 months (180 days) when our observation ended (median survival of miR-34a treated group was 135 days versus 23 days in miR-NC group; Figure 5B). Since we did not find any difference among control groups, only scrambled oligonucleotides formulated with NLE particles were used in subsequent experiments. Moreover, we also found a significant antitumor effect by intratumoral injection of formulated miR-34a in RPMI-8226 xenografts (P=0.037; supplemental Figure S6). Therefore we conclude that miR-34a by intratumoral delivery is highly effective against TP53-mutated MM xenografts and significantly prolongs host survival.

Figure 5. Intratumoral injection and systemic delivery of NLE-formulated miR-34a inhibits tumor growth in MM xenografts in SCID mice.

A) Effects of formulated miR-34a in SKMM1 xenografts by intratumoral injections. Palpable subcutaneous tumor xenografts were repeatedly treated every 3 days, as indicated by arrows, with 20 μg of formulated miR-34a or miR-NC (NC). As control 2 separate groups of tumor-bearing animals were injected with vehicle alone (MaxSuppressor™ In Vivo RNA-LANCEr II) or phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Tumors were measured with an electronic caliper every day, averaged tumor volume ±SD of each group are shown. P values were calculated of miR-34a versus miR-NC (Student’s t test, two-tailed). (*) indicate significant P-values (P<0.05). B) Survival curves (Kaplan-Meier) of intratumorally treated mice show prolongation of survival in miR-34a-treated SKMM1 xenografts compared to controls (log-rank test, P=0.0009). Survival was evaluated from the first day of treatment until death or sacrifice. Percent of mice alive is shown. C) Mice with palpable subcutaneous SKMM1 tumor xenografts were treated with 20 μg of formulated miR-34a or scrambled oligonucleotides (NC) by intravenous tail vein injections. Caliper measurement of tumors were taken every 2 days from the day of first treatment. Averaged tumor volumes ± SD are reported. (*) indicate significant P-values (P<0.05).

D) Survival curves (Kaplan-Meier) of systemically miR-34a treated mice show prolongation of survival compared to controls (log-rank test, P=0.041). Survival was evaluated from the first day of treatment until death or sacrifice. Percent of mice alive is shown.

Systemic delivery of formulated miR-34a inhibits growth of MM xenografts in SCID mice

We next explored the systemic delivery potential of formulated miR34a mimics in controlling the growth of MM xenografts. We observed significant tumor growth inhibition (P<0.01) in mice treated with miR-34a mimics versus controls (Figure 5C), and this effect was associated with prolonged survival (P=0.041; median survival of miR-34a treated group was 44 days versus 26 days in miR-NC group; Figure 5D). Interestingly, 60% of miR-34a-treated mice were still alive at the end of observation. q-RT-PCR analysis of miR-34a levels in excised tumors showed 4-fold increase of miR-34a levels (supplemental Figure S5B). There were large areas of necrosis with abundant nuclear debris (“dustlike” nuclear fragments, supplemental Figure S7A) in miR-34a-treated xenografts. Moreover, MM cells exhibited cleaved caspase-3 and lower Ki-67 expression, indicating that miR-34a treatment induced inhibition of proliferation and triggered apoptosis in MM xenografts in vivo. Moreover, downregulation of BCL2, CDK6 and NOTCH1 at mRNA (supplemental Figure S7B) and protein level (supplemental Figure S7C) were detected by q-RT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively. Notably, analysis of treated versus control mice did not show any significant behavioral changes or weight loss in SCID mice. No pathologic changes were detected by analysis of normal tissues including heart, kidney, liver and bone marrow of treated mice, indicating the absence of acute toxicity induced by the use of NLE formulated miR-34a mimics (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrated the anti-MM potential of miR-34a mimics administered by systemic injection, similar to the inhibition of tumor formation by stable transfection of lentivirus miR-34a. The observed downregulation of miR-34a validated targets at both mRNA and protein levels further supports the therapeutic potential of NLE formulated miR-34a mimics.

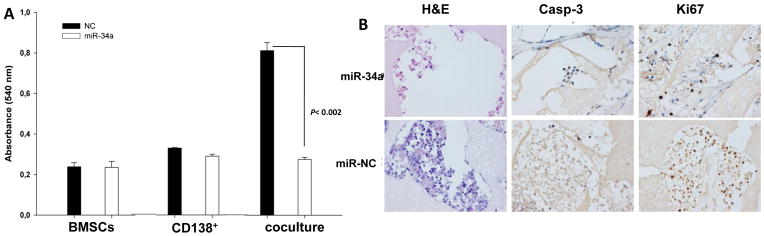

miR-34a overcomes the human BMM-dependent protective effect on MM cells in vitro and in vivo

To further study the therapeutic potential of our findings as a novel anti-MM treatment, we evaluated the effect of miR-34a mimics on MM cells adhering to human BMSCs. We first tested the activity of miR-34a in co-cultures in vitro where primary MM cells adhered to human MM patient-derived BMSCs. We found that miR-34a MM cell electroporation overcame the supportive effect of BMSCs, as evidenced by inhibition of primary MM cell proliferation (Figure 6A). We next investigated the anti-MM activity in vivo using our recently established novel SCID-synth-hu model (43). Specifically, we engrafted primary CD138+ cells from advanced disease to evaluate the miR-34a activity when tumor cells adhered to human BMSCs. Histological and immunohistochemical analysis of retrieved 3D biopolymeric scaffolds after treatment with formulated miR-34a showed reduced tumor infiltration and an increase of cleaved caspase-3 and reduction of Ki-67 expression (Figure 6B). These findings indicate that miR-34a overcomes the protective role of human BMM, providing an additional rationale for development of miR-34a in early clinical trials.

Figure 6. miR-34a exerts anti-MM activity in co-cultures of primary MM-BMSCs and in the SCID-synth-hu model.

A) MTS assay performed in CD138+ cells from a MM patient co-cultured with BMSCs, 24 hours after electroporation with synthetic miR-34a or miR-NC. Absorbance measurements ±SD of 3 independent experiments is shown; significant reduction in cell survival was observed (P<0.002, by Student’s t test, two-tailed) in co-cultures treated with miR-34a. B) In vivo analysis of miR-34a in the SCID-synth-hu model. TP53-mutated primary CD138+ MM cells were injected into 3D biopolymeric scaffolds with BMSCs. Engrafted synthetic scaffolds were directly injected in vivo by NLE formulated miR-34a or miR-NC in three mice for each group. A representative H&E and immunohistochemistry staining of Ki-67 and caspase-3 on retrieved scaffolds from treated animals is shown (magnification x40).

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate that synthetic miR-34a exerts a powerful anti-tumor activity in clinically relevant xenograft models of human MM. In vivo results were complemented by in vitro experiments where miR-34a mimics demonstrated significant anti-proliferative activity, apoptotic effects and modulation of gene expression. To our knowledge, this is the first experimental evidence of anti-tumor activity of miR-34a in preclinical models of MM.

An important fallout of our work is the successful delivery of miR-34a mimics in MM xenografts in SCID mice and in the SCID-synth-hu model via NLE, a novel lipid-based delivery vehicle which overcomes many of the most important limitations of other vehicles (34). In our study, the NLE-formulated miR-34a was safely administered to animals by either intratumor or systemic injection. In the latter case, the achievement of tumor growth inhibition in sc xenografts is substantial and particularly relevant, given the poor vascularization of rapidly growing xenografts. Importantly, these findings indicate the optimal bioavailability of NLE formulated-miR-34a mimics. Moreover, the miR-34a target downregulation in tumors excised from animals treated systemically with miR-34a mimics further confirms successful miRNA delivery. In order to provide the framework for clinical translation of this experimental approach, we further confirmed the in vivo activity of miR-34a mimics using the innovative SCID-synth-hu model of human MM (43–45). In this biosynthetic and orthotopic model of human MM, tumor cells grow within a bone-like 3D biopolymeric scaffold previously engrafted with MM patient-derived human BMSCs. In this model, delivery of systemic miR-34a mimics induced significant anti-tumor effects, as demonstrated by immunohistochemical analysis of retrieved scaffolds, corroborating the results obtained with the other two murine xenograft models of human MM used in this study. Most importantly, the anti-tumor properties of miR-34a mimics were not attenuated by the protective role of BMSCs, further highlighting the potential for clinical translation of our findings. In addition, the anti-MM activity of miR-34a occurred without any evidence of toxicity in mice, suggesting a favorable therapeutic index. Our data are in agreement with reports by Wiggins et al (33) on the safe use of formulated NLE-miR-34a in experimental animals, and strongly support clinical development of miR-34a-based strategies in MM patients. Notably, formulated miRNA mimics are distinct from molecularly-targeted drugs, since their anti-tumor activity relies on the modulation of a wide range of genes rather than inhibition of individual gene products. In particular, miRNA-based therapeutics can be relevant both for safety issues and to abrogate late onset of resistance, due to the complexity of miRNA-targeted pathways and the consequent low chance of developing individual “escape” mutations in the treated cells.

The molecular mechanisms of anti-myeloma activity of miR34a mimics are presently under investigation. Functionally, miR-34a is a component of the TP53 transcriptional network; in TP53-wild-type cells, it is involved in a feedback loop where TP53 activates miR-34a expression, which in turn increases the activity of TP53 (31). In fact, loss of miR-34a is associated with resistance to apoptosis induced by TP53-activating agents (21, 24). The tumor suppressor activity of miR-34a observed in this study seems to be TP53-dependent, since it mainly occurs in tumors bearing TP53-mutated gene. In this context, it is of great interest that we found high in vivo activity of miR-34a against SKMM1 xenografts with a TP53 inactivating mutation but intermediate levels of miR-34a, suggesting that the anti-MM potential of miR-34a is due to more than just simple miRNA replacement in fully depleted cells. Moreover, our finding that anti-miR-34a oligonucleotide transfection in TP53 wild-type MM cells produced a growth stimulus provides further evidence of the miR-34a role as a negative regulator of MM cell growth and highlights the rationale of our experimental strategy of inducing miR-34a expression in TP53 mutated MM. The high sensitivity of TP53 mutated MM cells is of interest, since TP53 inactivation occurs when MM progresses to a drug-resistant and more aggressive phenotype. While 13% of MM patients carry TP53 coding mutations or 17q13.1 deletion causing allelic loss of TP53, 24% of plasma cell leukemia (PCL) patients have TP53 coding mutations and 50% of primary PCL patients or 75% of secondary PCL patients have 17q13.1 deletion (47–50). Furthermore, a biallelic inactivation with both coding mutation and allelic deletion has been found in 11% and 33% of primary or secondary PCL patients, respectively (47, 49, 51), suggesting that the “biologically end-stage” disease might benefit from therapies restoring the TP53 function through miR-34a enforcement.

Of major relevance at this point is the development of therapeutic rationally designed combinations based on the study of the molecular mechanism of miR-34a activity. An interesting combination may be with gamma-secretase inhibitors taking in account NOTCH1 as relevant miR-34a target. The molecular complexity of human MM highlights the need of novel miRNA-based therapeutic combinations, and the present study along with previous findings (17, 18), provides the basis for these research perspectives.

In conclusion, the successful delivery and the anti-tumor activity of miR-34a mimics in clinically relevant mouse models, together with the favorable safety profile, provide the rationale and the framework for clinical development of synthetic miR-34a mimics to improve patient outcome in MM.

Supplementary Material

Statement of translational relevance.

The miRNA regulatory network is emerging as a novel target for the treatment of human cancer. In this study, we investigated the therapeutic potential of synthetic miR-34a against TP53-mutated human multiple myeloma cells in vitro and in vivo. The translational relevance of our study resides in the findings that intratumor or systemic delivery of novel lipidic-formulated synthetic miR-34a induces anti-myeloma activity in vivo in different murine models of human MM, including the most innovative SCID-synth-hu system, in the absence of systemic toxicity in treated animals. Moreover, the specificity of the miR-34a in vivo activity was demonstrated by selective downregulation of canonic targets BCL2 and CDK6. Taken together our results indicate that formulated synthetic miR-34a is an active agent against multiple myeloma, which merits further investigation for clinical development in this still incurable disease.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work has been supported by funds of Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC), PI: PT. “Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology - 5 per mille” n. 9980, 2010/15. KCA is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor.

Footnotes

Conflicts- of- interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Anderson KC, Carrasco RD. Pathogenesis of myeloma. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:249–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lonial S, Mitsiades CS, Richardson PG. Treatment options for relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1264–77. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajkumar SV. Treatment of multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:479–91. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan GJ, Walker BA, Davies FE. The genetic architecture of multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:335–48. doi: 10.1038/nrc3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tassone P, Tagliaferri P, Rossi M, Gaspari M, Terracciano R, Venuta S. Genetics and molecular profiling of multiple myeloma: novel tools for clinical management? Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1530–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossi M, Di Martino MT, Morelli E, Leotta M, Rizzo A, Grimaldi A, et al. Molecular Targets for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2012 doi: 10.2174/156800912802429300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calin GA, Sevignani C, Dumitru CD, Hyslop T, Noch E, Yendamuri S, et al. Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2999–3004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307323101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:704–14. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs-microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–69. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garzon R, Marcucci G, Croce CM. Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:775–89. doi: 10.1038/nrd3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pichiorri F, De Luca L, Aqeilan RI. MicroRNAs: New Players in Multiple Myeloma. Frontiers in genetics. 2011;2:22. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2011.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lionetti M, Agnelli L, Lombardi L, Tassone P, Neri A. MicroRNAs in the Pathobiology of Multiple Myeloma. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2012 doi: 10.2174/156800912802429274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benetatos L, Dasoula A, Hatzimichael E, Syed N, Voukelatou M, Dranitsaris G, et al. Polo-like kinase 2 (SNK/PLK2) is a novel epigenetically regulated gene in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes: genetic and epigenetic interactions. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:1037–45. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tagliaferri P, Rossi M, Di Martino MT, Amodio N, Leone E, Gulla A, et al. Promises and Challenges of MicroRNA-based Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2012 doi: 10.2174/156800912802429355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roccaro AM, Sacco A, Thompson B, Leleu X, Azab AK, Azab F, et al. MicroRNAs 15a and 16 regulate tumor proliferation in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2009;113:6669–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pichiorri F, Suh SS, Rocci A, De Luca L, Taccioli C, Santhanam R, et al. Downregulation of p53-inducible microRNAs 192, 194, and 215 impairs the p53/MDM2 autoregulatory loop in multiple myeloma development. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:367–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Bader AG. miR-34 - a microRNA replacement therapy is headed to the clinic. Frontiers in genetics. 2012;3:120. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lodygin D, Tarasov V, Epanchintsev A, Berking C, Knyazeva T, Korner H, et al. Inactivation of miR-34a by aberrant CpG methylation in multiple types of cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2591–600. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.16.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermeking H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:193–9. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chim CS, Wong KY, Qi Y, Loong F, Lam WL, Wong LG, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of the miR-34a in hematological malignancies. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:745–50. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welch C, Chen Y, Stallings RL. MicroRNA-34a functions as a potential tumor suppressor by inducing apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:5017–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bommer GT, Gerin I, Feng Y, Kaczorowski AJ, Kuick R, Love RE, et al. p53-mediated activation of miRNA34 candidate tumor-suppressor genes. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang TC, Wentzel EA, Kent OA, Ramachandran K, Mullendore M, Lee KH, et al. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:745–52. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He L, He X, Lim LP, de Stanchina E, Xuan Z, Liang Y, et al. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature. 2007;447:1130–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarasov V, Jung P, Verdoodt B, Lodygin D, Epanchintsev A, Menssen A, et al. Differential regulation of microRNAs by p53 revealed by massively parallel sequencing: miR-34a is a p53 target that induces apoptosis and G1-arrest. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1586–93. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.13.4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tazawa H, Tsuchiya N, Izumiya M, Nakagama H. Tumor-suppressive miR-34a induces senescence-like growth arrest through modulation of the E2F pathway in human colon cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15472–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707351104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raver-Shapira N, Marciano E, Meiri E, Spector Y, Rosenfeld N, Moskovits N, et al. Transcriptional activation of miR-34a contributes to p53-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:731–43. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji Q, Hao X, Zhang M, Tang W, Yang M, Li L, et al. MicroRNA miR-34 inhibits human pancreatic cancer tumor-initiating cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamakuchi M, Lowenstein CJ. MiR-34, SIRT1 and p53: the feedback loop. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:712–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.5.7753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu C, Kelnar K, Liu B, Chen X, Calhoun-Davis T, Li H, et al. The microRNA miR-34a inhibits prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by directly repressing CD44. Nat Med. 2011;17:211–5. doi: 10.1038/nm.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiggins JF, Ruffino L, Kelnar K, Omotola M, Patrawala L, Brown D, et al. Development of a lung cancer therapeutic based on the tumor suppressor microRNA-34. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5923–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trang P, Wiggins JF, Daige CL, Cho C, Omotola M, Brown D, et al. Systemic delivery of tumor suppressor microRNA mimics using a neutral lipid emulsion inhibits lung tumors in mice. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1116–22. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burger R, Guenther A, Bakker F, Schmalzing M, Bernand S, Baum W, et al. Gp130 and ras mediated signaling in human plasma cell line INA-6: a cytokine-regulated tumor model for plasmacytoma. The hematology journal: the official journal of the European Haematology Association/EHA. 2001;2:42–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tassone P, Neri P, Carrasco DR, Burger R, Goldmacher VS, Fram R, et al. A clinically relevant SCID-hu in vivo model of human multiple myeloma. Blood. 2005;106:713–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neri P, Kumar S, Fulciniti MT, Vallet S, Chhetri S, Mukherjee S, et al. Neutralizing B-cell activating factor antibody improves survival and inhibits osteoclastogenesis in a severe combined immunodeficient human multiple myeloma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5903–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fulciniti M, Hideshima T, Vermot-Desroches C, Pozzi S, Nanjappa P, Shen Z, et al. A high-affinity fully human anti-IL-6 mAb, 1339, for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7144–52. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamasaki M, Hideshima T, Tassone P, Neri P, Ishitsuka K, Yasui H, et al. Azaspirane (N-N-diethyl-8,8-dipropyl-2-azaspiro [4.5] decane-2-propanamine) inhibits human multiple myeloma cell growth in the bone marrow milieu in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2005;105:4470–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peltier HJ, Latham GJ. Normalization of microRNA expression levels in quantitative RT-PCR assays: identification of suitable reference RNA targets in normal and cancerous human solid tissues. RNA. 2008;14:844–52. doi: 10.1261/rna.939908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neri P, Tagliaferri P, Di Martino MT, Calimeri T, Amodio N, Bulotta A, et al. In vivo anti-myeloma activity and modulation of gene expression profile induced by valproic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:520–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calimeri T, Battista E, Conforti F, Neri P, Di Martino MT, Rossi M, et al. A unique three-dimensional SCID-polymeric scaffold (SCID-synth-hu) model for in vivo expansion of human primary multiple myeloma cells. Leukemia. 2011;25:707–11. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tassone P, Neri P, Burger R, Di Martino MT, Leone E, Amodio N, et al. Mouse Models as a Translational Platform for the Development of New Therapeutic Agents in Multiple Myeloma. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2012 doi: 10.2174/156800912802429292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeWeerdt S. Animal models: Towards a myeloma mouse. Nature. 2011;480:S38–9. doi: 10.1038/480S38a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, Carvajal D, Podlaski F, Filipovic Z, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303:844–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jimenez-Zepeda VH, Dominguez-Martinez VJ. Plasma cell leukemia: a highly aggressive monoclonal gammopathy with a very poor prognosis. Int J Hematol. 2009;89:259–68. doi: 10.1007/s12185-009-0288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tiedemann RE, Gonzalez-Paz N, Kyle RA, Santana-Davila R, Price-Troska T, Van Wier SA, et al. Genetic aberrations and survival in plasma cell leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:1044–52. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lloveras E, Granada I, Zamora L, Espinet B, Florensa L, Besses C, et al. Cytogenetic and fluorescence in situ hybridization studies in 60 patients with multiple myeloma and plasma cell leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;148:71–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(03)00233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chng WJ, Price-Troska T, Gonzalez-Paz N, Van Wier S, Jacobus S, Blood E, et al. Clinical significance of TP53 mutation in myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21:582–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Greipp PR, Litzow MR, Henderson KJ, et al. Clinical implications of t(11;14) (q13;q32), t(4;14) (p16.3;q32), and -17p13 in myeloma patients treated with high-dose therapy. Blood. 2005;106:2837–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.