Abstract

Background:

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have been shown to play major roles in carcinogenesis in a variety of cancers. The aim of this study was to determine the miRNA expression signature of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and to investigate the functional roles of miR-26a and miR-26b in OSCC cells.

Methods:

An OSCC miRNA signature was constructed by PCR-based array methods. Functional studies of differentially expressed miRNAs were performed to investigate cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in OSCC cells. In silico database and genome-wide gene expression analyses were performed to identify molecular targets and pathways mediated by miR-26a/b.

Results:

miR-26a and miR-26b were significantly downregulated in OSCC. Restoration of both miR-26a and miR-26b in cancer cell lines revealed that these miRNAs significantly inhibited cancer cell migration and invasion. Our data demonstrated that the novel transmembrane TMEM184B gene was a direct target of miR-26a/b regulation. Silencing of TMEM184B inhibited cancer cell migration and invasion, and regulated the actin cytoskeleton-pathway related genes.

Conclusions:

Loss of tumour-suppressive miR-26a/b enhanced cancer cell migration and invasion in OSCC through direct regulation of TMEM184B. Our data describing pathways regulated by tumour-suppressive miR-26a/b provide new insights into the potential mechanisms of OSCC oncogenesis and metastasis.

Keywords: microRNA, oral squamous cell carcinoma, miR-26a, miR-26b, tumour suppressor, TMEM184B, expression signature

In the post-genome sequencing era, the discovery of noncoding RNAs in the human genome was an important conceptual breakthrough in the study of cancer (Carthew and Sontheimer, 2009). Further improvement of our understanding of noncoding RNAs is necessary for continued elucidation of the mechanisms of cancer initiation, development, and metastasis. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous small noncoding RNA molecules (19–22 bases in length) that regulate protein-coding gene expression by repressing translation or cleaving RNA transcripts in a sequence-specific manner (Bartel, 2004). A substantial amount of evidence has suggested that miRNAs are aberrantly expressed in many human cancers and play significant roles in human oncogenesis and metastasis (Filipowicz et al, 2008; Hobert, 2008; Friedman et al, 2009; Iorio and Croce, 2009).

It is believed that normal regulatory mechanisms can be disrupted by the aberrant expression of tumour-suppressive or oncogenic miRNAs in cancer cells. Therefore, the identification of aberrantly expressed miRNAs is an important first step toward elucidating the details of miRNA-mediated oncogenic pathways. On the basis of this background, we have previously evaluated miRNA expression signatures using squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) clinical specimens, for example, maxillary sinus-SCC (Nohata et al, 2011c; Nohata et al, 2011d; Kinoshita et al, 2012d), hypopharyngeal-SCC (Kikkawa et al, 2010; Fukumoto et al, 2014), and oesophageal-SCC (Kano et al, 2010) and investigated the roles of miRNAs in human SCC oncogenesis and metastasis using differentially expressed miRNAs (Nohata et al, 2011a; Kinoshita et al, 2012c; Kinoshita et al, 2013). Elucidation of aberrantly expressed miRNAs in several types of human SCC specimens and of novel cancer pathways regulated by tumour-suppressive miRNAs will provide new insights into the potential mechanisms of SCC oncogenesis.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) accounts for over 95% of oral cavity cancer and 40% of head and neck SCC. In developing countries, OSCC is the sixth most common cancer in men and the tenth most common cancer in women, and the incidence is increasing among young people and women (Bhattacharya et al, 2011). Oral squamous cell carcinoma is associated with a poor prognosis and has a 5-year survival rate of less than 50% owing to the tendency of the cancer to metastasise (Bhattacharya et al, 2011). Moreover, despite recent advances in various treatment modalities, including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the survival rates of patients with OSCC have not markedly improved (Wikner et al, 2014). Therefore, understanding molecular oncogenic pathways based on the current genome-based approaches underlying OSCC could significantly improve diagnosis, therapy, and prevention of the disease.

In this study, we constructed the miRNA expression signature of OSCC using clinical specimens. Using these data, we investigated the specific roles of miRNAs in OSCC oncogenesis and metastasis by examining differentially expressed miRNAs. Data from our present OSCC signature showed that miR-26a and miR-26b were significantly downregulated in OSCC tissues, suggesting that miR-26a and miR-26b may act as tumour suppressors. Several studies of miR-26a/b have reported that these miRNAs have various functions and target genes in many types of cancers (Lu et al, 2011; Deng et al, 2013; Chen et al, 2014; Li et al, 2014). These reports have indicated that miR-26a/b may play critical roles in cancer cells and may mediate oncogenesis and metastasis. However, the functional roles of miR-26a/b in OSCC are still unknown.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the functional significance of miR-26a/b and to identify the molecular targets and pathways mediated by these miRNAs in OSCC cells. Our data demonstrated that restoration of mature miR-26a and miR-26b inhibited cancer cell migration and invasion. Moreover, gene expression data and in silico database analysis showed that the TMEM184B gene was a direct target of miR-26a/b regulation. Silencing of the TMEM184B gene significantly inhibited the migration and invasion of cancer cells and caused alterations in genes involved in regulation of the actin cytoskeleton pathway. The discovery of pathways mediated by tumour-suppressive miR-26a/b provides important insights into the potential mechanisms of OSCC oncogenesis and suggests novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of OSCC.

Materials and methods

Oral squamous cell carcinoma clinical specimens and cell lines

A total of 36 pairs of primary tumours and corresponding normal epithelial tissue samples were obtained from patients with OSCC at Chiba University Hospital from 2008 to 2013. The patients' background and clinicopathological characteristics are shown in Table 1. The patients were classified according to the 2002 Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) staging criteria before treatment. Written consent for tissue donation for research purposes was obtained from each patient before tissue collection. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Chiba University. The fresh specimens were immediately immersed in RNAlater (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and stored at −20 °C until RNA was extracted.

Table 1. Clinical features of 36 OSCC patients.

| No. | Age | Sex | Location | T | N | M | Stage | Differentiaion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 66 | M | Tongue | 2 | 0 | 0 | II | Moderate |

| 2 | 65 | M | Oral floor | 4a | 1 | 0 | IVA | Moderate |

| 3 | 67 | M | Tongue | 4a | 2c | 0 | IVA | Moderate |

| 4 | 36 | F | Tongue | 3 | 1 | 0 | III | Moderate |

| 5 | 73 | M | Tongue | 3 | 2b | 0 | IVA | Poor |

| 6 | 63 | F | Oral floor | 2 | 2b | 0 | IVA | Basaloid SCC |

| 7 | 77 | M | Gum | 2 | 0 | 0 | II | Moderate |

| 8 | 68 | M | Tongue | 2 | 0 | 0 | II | Well |

| 9 | 76 | F | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 10 | 69 | M | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 11 | 73 | F | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 12 | 64 | M | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 13 | 64 | M | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 14 | 82 | M | Oral floor | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 15 | 67 | M | Oral floor | 4a | 2b | 0 | IVA | Well |

| 16 | 67 | M | Tongue | 3 | 0 | 0 | III | Moderate |

| 17 | 64 | M | Tongue | 3 | 2b | 0 | IVA | Moderate |

| 18 | 59 | M | Tongue | 1 | 2a | 0 | IVA | Moderate |

| 19 | 47 | M | Oral floor | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Moderate |

| 20 | 67 | M | Tongue | 2 | 0 | 0 | II | Poor∼moderate |

| 21 | 70 | M | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 22 | 38 | M | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 23 | 70 | M | Tongue, Oral floor | 2 | 0 | 0 | II | Well |

| 24 | 51 | M | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 25 | 81 | M | Tongue | is | 0 | 0 | 0 | Extremely well |

| 26 | 34 | F | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Poor |

| 27 | 42 | M | Gum | 4a | 0 | 0 | IVA | Moderate |

| 28 | 70 | M | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Moderate |

| 29 | 71 | M | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 30 | 60 | F | Tongue | 2 | I | 0 | III | Well |

| 31 | 77 | M | Tongue | 2 | 2b | 0 | IVA | Poorly |

| 32 | 64 | F | Oral floor | 4a | 2c | 0 | IVA | Moderate |

| 33 | 68 | M | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Well |

| 34 | 29 | F | Tongue | 1 | 0 | 0 | I | Poorly |

| 35 | 71 | M | Buccal mucosa | 2 | 1 | 0 | III | Poorly |

| 36 | 39 | M | Tongue | 4a | 0 | 0 | IVA | Moderate |

Abbreviations: F=female; M=male; SCC=squamous cell carcinoma.

SAS (derived from a primary tongue SCC) and HSC3 (derived from a lymph node metastasis of tongue SCC) OSCC cells were used in this study. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% foetal bovine serum in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C.

Construction of the miRNA expression signature of OSCC

MicroRNA expression patterns were evaluated using the TaqMan LDA Human microRNA Panel v2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The assay was composed of two steps: (i) generation of cDNA by reverse transcription and (ii) a TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. A description of the real-time PCR assay and the list of human miRNAs included in the panel can be found on the manufacturer's website (http://www.appliedbiosystems.com). Analysis of relative miRNA expression data was performed using GeneSpring GX software version 7.3.1 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A cut-off P-value of less than 0.05 was used to narrow down the candidates after global normalisation of the raw data. After global normalisation, additional normalisation was carried out with RNU48.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

The procedure for PCR quantification was described previously (Kinoshita et al, 2013; Goto et al, 2014a). Gene-specific PCR products were assayed continuously using a 7300 HT real-time PCR system according to the manufacturer's protocol. The expression levels of miR-26a (Assay ID: 000405) and miR-26b (Assay ID: 000407) were analysed by TaqMan quantitative real-time PCR (TaqMan MicroRNA Assay; Applied Biosystems) and normalised to RNU48. TaqMan probes and primers for TMEM184B (P/N: Hs00202153_m1), CELSR1 (P/N: Hs00947712_m1), JAG1 (P/N: Hs01070032_m1), BID (P/N: Hs00609632_m1), and GUSB (P/N: Hs99999908_m1) as an internal control were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Assay-On-Demand Gene Expression Products).

Transfection with mature miRNAs and small-interfering RNA (siRNA)

The following mature miRNAs species were used in this study: mirVana miRNA mimics for hsa-miR-26a-5p (product ID: PM10249) and hsa-miR-26b-5p (product ID: PM12899; Applied Biosystems). The following siRNAs were used: Stealth Select RNAi siRNA targeting TMEM184B (si-TMEM184B, cat no. HSS119359) and negative control miRNA/SiRNA (P/N: AM17111, Applied Biosystems). Transfection methods were described as previously (Kinoshita et al, 2013; Fukumoto et al, 2014; Nishikawa et al, 2014a).

Cell proliferation, migration, and invasion assays

SAS and HSC3 cells were transfected with 10 nM miRNAs or si-RNA by reverse transfection. Cell proliferation, migration, and invasion assays were performed as described previously (Kinoshita et al, 2013; Fukumoto et al, 2014; Nishikawa et al, 2014b).

Identification of putative target genes regulated by miR-26a/b

Genes regulated by miR-26a/b were obtained from the TargetScan database (http://www.targetscan.org). To investigate the expression status of candidate miR-26a/b target genes in OSCC clinical specimens, we examined gene expression profiles in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (Accession Number GSE41613 and GSE42743). The strategy behind this analysis procedure was described previously (Goto et al, 2014b).

Identification of downstream pathways and genes regulated by TMEM184B

To identify molecular pathways regulated by TMEM184B in cancer cells, we performed gene expression analysis using si-TMEM184B-transfected SAS and HSC3 cells. An oligo-microarray (human 60Kv; Agilent Technologies) was used for gene expression studies. Gene expression data were categorised according to the Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways using the GENECODIS program (http://genecodis.dacya.ucm.es). The strategy behind this analysis procedure was described (Kinoshita et al, 2013; Nishikawa et al, 2014b).

Western blotting

Cells were harvested 72 h after transfection, and lysates were prepared. Next, 20 μg of protein lysates were separated on Mini-PROTEAN TGX Gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Immunoblotting was performed with rabbit anti-TMEM184B antibodies (1 : 500; PA-5-20932 (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA)), and anti-GAPDH antibodies (1 : 1000; ab 8245 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK)) were used as an internal loading control.

Plasmid construction and dual-luciferase reporter assay

Partial wild-type sequences of the TMEM184B 3′-untranslated region (UTR) or those with a deleted miR-26a/b target site (position 1982–1989 of the TMEM184B 3′-UTR) were inserted between the Xhol-PmeI restriction sites in the 3′-UTR of the hRluc gene in the psiCHECK-2 vector (C8021; Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The procedure for the dual-luciferase reporter assay was described previously (Kinoshita et al, 2013; Fukumoto et al, 2014; Nishikawa et al, 2014b).

Statistical analysis

The relationship between two groups and the numerical values obtained by real-time PCR were analysed using the paired t-test. Spearman's rank test was used to evaluate the correlation between the expression of miR-26a/b and TMEM184B. Relationships among more than three variables and numerical values were analysed using the Bonferroni-adjusted Mann-Whitney U-test. All analyses were performed using Expert StatView software (Version 4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Identification of downregulated miRNAs in OSCC by miRNA expression signatures

We evaluated mature miRNA expression levels of five pairs of normal epithelial tissues and OSCC tissues (patient numbers 1–5, Table 1) by miRNA expression signature by using PCR-based array analysis. In total, 23 significantly downregulated miRNAs were selected after normalisation to RNU48 (Table 2).

Table 2. Downregulated miRNAs in OSCC.

| MicroRNA | Accession no. | Location | P-value | Normal | Tumour | Fold change (tumour/normal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-126-5p | MIMAT0000444 | 9q34.3 | 0.0002 | 0.0697 | 0.0191 | 0.273 |

| miR-145-5p | MIMAT0000437 | 5q32 | 0.0004 | 0.1045 | 0.0347 | 0.332 |

| miR-145-3p | MIMAT0004601 | 5q32 | 0.0008 | 0.0022 | 0.0009 | 0.403 |

| miR-26b-5p | MIMAT0000083 | 2q35 | 0.0011 | 0.0440 | 0.0214 | 0.486 |

| miR-26a-5p | MIMAT0000082 | 3p22.2 12q14.1 | 0.0014 | 0.1722 | 0.0745 | 0.432 |

| miR-204 | MIMAT0000265 | 9q21.12 | 0.0029 | 0.0043 | 0.0004 | 0.088 |

| miR-29c | MIMAT0000681 | 1q32.2 | 0.0035 | 0.1156 | 0.0416 | 0.360 |

| miR-195 | MIMAT0000461 | 17p13.1 | 0.0068 | 0.0609 | 0.0228 | 0.375 |

| miR-30c | MIMAT0000244 | 1p34.2 6q13 | 0.0072 | 0.2374 | 0.1037 | 0.437 |

| miR-10b | MIMAT0000245 | 2q31.1 | 0.0072 | 0.0093 | 0.0041 | 0.442 |

| miR-656 | MIMAT0003332 | 14q32.31 | 0.0082 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.267 |

| miR-30e-3p | MIMAT0000693 | 1p34.2 | 0.0094 | 0.0339 | 0.0094 | 0.279 |

| miR-140-5p | MIMAT0000431 | 16q22.1 | 0.0094 | 0.0810 | 0.0378 | 0.466 |

| miR-23b | MIMAT0000418 | 9q22.32 | 0.0095 | 0.0066 | 0.0027 | 0.410 |

| miR-10b | MIMAT0000254 | 2q31.1 | 0.0108 | 0.0043 | 0.0017 | 0.404 |

| miR-126-3p | MIMAT0000445 | 9q34.3 | 0.0118 | 1.7499 | 0.6259 | 0.358 |

| miR-143 | MIMAT0000435 | 5q32 | 0.0125 | 0.0749 | 0.0345 | 0.460 |

| miR-30d | MIMAT0000245 | 8q24.22 | 0.0133 | 0.0007 | 0.0003 | 0.375 |

| miR-139-5p | MIMAT0000250 | 11q13.4 | 0.0134 | 0.0621 | 0.0099 | 0.160 |

| miR-19b-1-5p | MIMAT0004491 | 13q31.3 | 0.0195 | 0.0009 | 0.0003 | 0.393 |

| miR-598 | MIMAT0003266 | 8p23.1 | 0.0201 | 0.0024 | 0.0011 | 0.473 |

| miR-885-5p | MIMAT0004947 | 3p25.3 | 0.0201 | 0.0024 | 0.0003 | 0.125 |

| miR-376c | MIMAT0000720 | 14q32.31 | 0.0220 | 0.0086 | 0.0017 | 0.192 |

| miR-487b | MIMAT0003180 | 14q32.31 | 0.0231 | 0.0005 | 0.0001 | 0.268 |

| miR-101 | MIMAT0000099 | 1p31.3 9p24.1 | 0.0231 | 0.0012 | 0.0005 | 0.385 |

| miR-886-5p | MIMAT0005527 | 0.0242 | 0.0125 | 0.0036 | 0.287 | |

| miR-140-3p | MIMAT0004597 | 16q22.1 | 0.0251 | 0.0070 | 0.0023 | 0.327 |

| miR-30e | MIMAT0000692 | 1p34.2 | 0.0252 | 0.0489 | 0.0213 | 0.435 |

| miR-125b | MIMAT0000423 | 11q24.1 24q21.1 | 0.0271 | 0.1164 | 0.0562 | 0.483 |

| miR-378a-5p | MIMAT0000731 | 5q32 | 0.0295 | 0.0027 | 0.0006 | 0.214 |

| miR-320 | MIMAT0000510 | 8p21.3 | 0.0302 | 0.2007 | 0.0803 | 0.400 |

| miR-136-3p | MIMAT0004606 | 14q.32.2 | 0.0320 | 0.0017 | 0.0002 | 0.120 |

| miR-26a-1-3p | MIMAT0004499 | 3p22.2 | 0.0342 | 0.0005 | 0.0001 | 0.153 |

| miR-127-3p | MIMAT0000446 | 14q32.2 | 0.0342 | 0.0098 | 0.0032 | 0.324 |

| miR-411 | MIMAT0003329 | 14q32.31 | 0.0426 | 0.0033 | 0.0008 | 0.245 |

| miR-30a-3p | MIMAT0000088 | 6q13 | 0.0450 | 0.0409 | 0.0060 | 0.147 |

| miR-29c-5p | MIMAT0004673 | 1q32.2 | 0.0455 | 0.0009 | 0.0003 | 0.325 |

| miR-376a | MIMAT0000729 | 14q32.31 | 0.0466 | 0.0007 | 0.0002 | 0.208 |

| miR-26b-3p | MIMAT0004500 | 2q35 | 0.0473 | 0.0006 | 0.0002 | 0.418 |

| miR-770-5p | MIMAT0003948 | 14q32.2 | 0.0475 | 0.0004 | 0.0001 | 0.416 |

| miR-433 | MIMAT0001627 | 14q.32.2 | 0.0477 | 0.0005 | 0.0001 | 0.268 |

| miR-375 | MIMAT0000728 | 2q35 | 0.0483 | 0.0226 | 0.0020 | 0.090 |

Expression of miR-26a/b in OSCC clinical specimens and cell lines

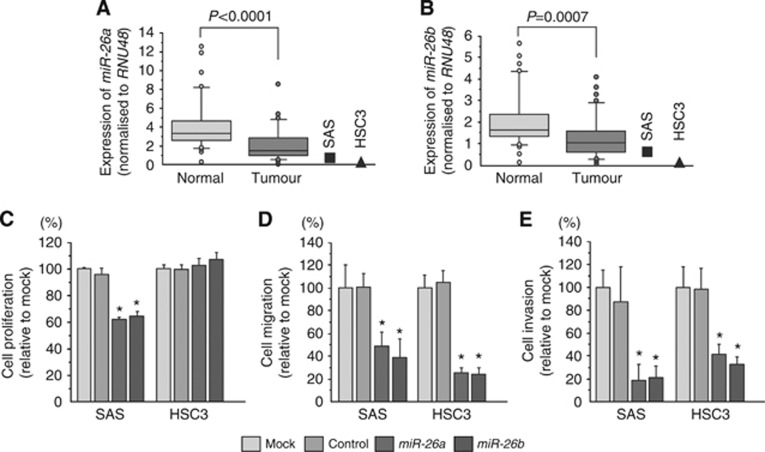

To validate miRNA signature results, we evaluated miR-26a/b expression in 36 clinical OSCC specimens (Table 1). The expression levels of both miR-26a and miR-26b were significantly lower in tumour tissues and cell lines (SAS and HSC3) than in corresponding normal epithelia (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Expression levels of miR-26a/b in OSCC clinical specimens and cell lines, and functional significance of miR-26a/b in OSCC cell lines. (A, B) Expression levels of miR-26a (A) and miR-26b (B) in OSCC clinical specimens and cell lines (SAS and HSC3). RNU48 was used for normalisation. (C) Cell proliferation was determined by XTT assay 72 h after transfection with 10 nM miR-26a/b. (D) Cell migration was determined by migration assay 48 h after transfection with 10 nM miR-26a/b. (E) Cell invasion was determined by Matrigel invasion assay 48 h after transfection with 10 nM miR-26a/b. *P<0.001.

Effects of restoring miR-26a/b on cell proliferation, migration, and invasion activities in OSCC cell lines

To investigate the functional effects of miR-26a/b in OSCC cells, we performed gain-of-function studies using mature miRNA transfection into SAS and HSC3 cells. XTT assays demonstrated that proliferation was not inhibited in HSC3 cells, whereas SAS cell proliferation was significantly slowed by transfection, in comparison with mock or miR-control transfectants (Figure 1C).

The migration assay demonstrated that migration activity was significantly inhibited in miR-26a/b transfectants in comparison with mock or miR-control transfectants (Figure 1D).

The Matrigel invasion assay demonstrated that invasion activity was significantly inhibited in miR-26a/b transfectants in comparison with mock or miR-control transfectants (Figure 1E).

Identification of putative target genes regulated by miR-26a/b in OSCC cells

To identify putative target genes regulated by miR-26a/b, we applied a combination of in silico analysis and genome-wide gene expression analysis. Our strategy for selection of miR-26a/b target genes is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. First, we screened miR-26a/b-targeted genes that contained a putative miR-26a/b binding site in their 3′-UTR using the TargetScan database and identified 3419 candidate genes. The gene set was then analysed with a publicly available gene expression data set in GEO (accession numbers: GSE41613 and GSE42743), and genes upregulated (log2 ratio >0.5) in OSCC were chosen. As a result, 14 candidate genes were identified as miR-26a/b targets, and four genes had a conserved miR-26a/b binding site in their 3′-UTRs (Table 3).

Table 3. Candidate genes targeted by miR-26a/b.

| Gene symbol | Representative transcript | Gene name | Conserved | Poorly conserved | Fold change (log2 ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CELSR1 | NM_014246 | Cadherin, EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 1 (flamingo homolog, Drosophila) | 1 | 0 | 0.890 |

| HMGB3 | NM_005342 | High mobility group box 3 | 0 | 1 | 0.768 |

| TDG | NM_003211 | Thymine-DNA glycosylase | 0 | 1 | 0.685 |

| VASP | NM_003370 | Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein | 0 | 1 | 0.639 |

| JAG1 | NM_000214 | Jagged 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.637 |

| CTSB | NM_001908 | Cathepsin B | 0 | 1 | 0.628 |

| BID | NM_001196 | BH3 interacting domain death agonist | 1 | 0 | 0.606 |

| FEN1 | NM_004111 | Flap structure-specific endonuclease 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.573 |

| MAP3K13 | NM_001242314 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 13 | 0 | 3 | 0.571 |

| TNFAIP8L1 | NM_001167942 | Tumour necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 8-like 1 | 0 | 2 | 0.561 |

| TMEM184B | NM_001195071 | Transmembrane protein 184B | 1 | 0 | 0.554 |

| PIK3CD | NM_005026 | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic, delta polypeptide | 0 | 1 | 0.544 |

| SLC25A17 | NM_006358 | Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; peroxisomal membrane protein, 34 kDa), member 17 | 0 | 1 | 0.537 |

| CLPTM1L | NM_030782 | CLPTM1-like | 0 | 1 | 0.525 |

| CTNS | NM_001031681 | Cystinosin, lysosomal cystine transporter | 0 | 3 | 0.518 |

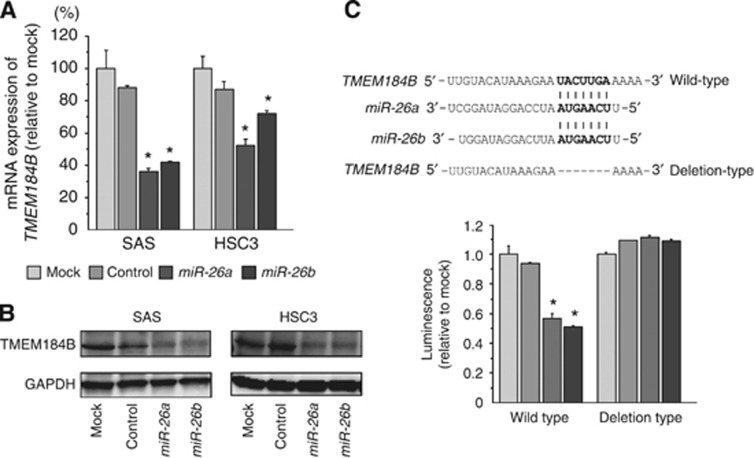

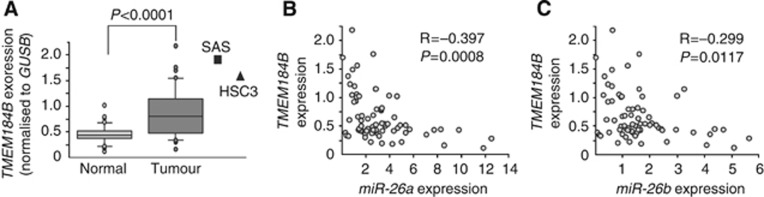

We investigated the expression levels of these four candidate genes in OSCC clinical specimens and cell lines (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure 2). Among these candidate genes, we focused on the TMEM184B gene because it was the most significantly downregulated gene in miR-26a/b transfectants, and Spearman's rank test showed the most significant negative correlation of TMEM184B with the expression of miR-26a/b (Figure 2B and C).

Figure 2.

Expression levels of TMEM184B in OSCC clinical specimens and cell lines. (A) Expression levels of TMEM184B in OSCC clinical specimens and cell lines (SAS and HSC3). GUSB was used for normalisation. (B, C) Correlation between TMEM184B expression and miR-26a (B) or miR-26b (C).

CELSR1 is one of the putative candidate target of miR-26a/b regulation because this gene has a miR-26a/b conserved site. We also examined functional significance of CELSR1 by using si-CELSR1 transfectants. Our data showed that silencing of CELSR1 inhibited cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in SAS and/or HSC3 cells, suggesting CELSR1 acts as an oncogene in OSCC cells (Supplementary Figure 3).

TMEM184B was a direct target of miR-26a/b in OSCC cells

Next, we investigated whether TMEM184B expression was reduced by restoration of miR-26a/b in OSCC cells. The mRNA and protein expression of TMEM184B was significantly repressed in miR-26a/b transfectants compared with mock- or miR-control-transfected cells (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 3.

TMEM184B expression was directly regulated by miR-26a/b in OSCC cell lines. (A) TMEM184B mRNA expression 72 h after transfection with miR-26a/b. GUSB expression was used for normalisation. (B) TMEM184B protein expression 72 h after transfection with miR-26a/b. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) The miR-26a/b binding site in the 3′-UTR of TMEM184B mRNA. Luciferase reporter assays were performed using vectors that included (WT) or lacked (DEL) the wild-type sequences of the putative miR-26a/b target site. Renilla luciferase assays were normalised to firefly luciferase values. *P<0.0001.

Thus, to investigate whether TMEM184B mRNA had a target site for miR-26a/b, we performed luciferase reporter assays in SAS cells. The TargetScan database showed that there was one putative miR-26a/b binding site in the TMEM184B 3′-UTR (position 1982–1989). We used vectors encoding either a partial wild-type sequence (including the predicted miR-26a/b target site) or deletion of the seed sequence of the 3′-UTR of TMEM184B mRNA. We found that the luminescence intensity was significantly reduced by cotransfection with miR-26a/b and the vector carrying the wild-type 3′-UTR of TMEM184B (Figure 3C).

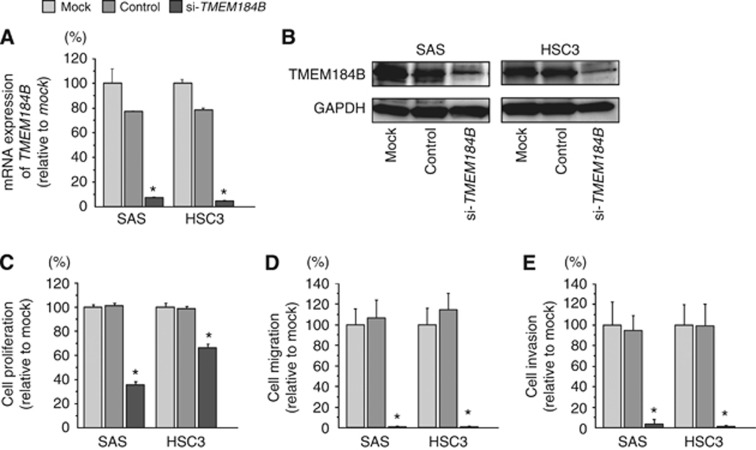

Effects of silencing TMEM184B on cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in OSCC cell lines

To investigate the functional roles of TMEM184B in OSCC cell lines, we performed loss-of-function studies using si-TMEM184B transfection. First, we evaluated the knockdown efficiency of si-TMEM184B transfection in SAS and HSC3 cells. Western blotting and qRT-PCR indicated that the siRNA effectively downregulated TMEM184B expression in both cell lines (Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Effects of si-TMEM184B transfection on OSCC cell lines. (A) TMEM184B mRNA expression levels were measured by RT-PCR 72 h after transfection with 10 nM si-TMEM184B. GUSB was used for normalisation. (B) TMEM184B protein expression 72 h after transfection with si-TMEM184B. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) Cell proliferation was determined by XTT assay 72 h after transfection with 10 nM si-TMEM184B. (D) Cell migration was determined by migration assay 48 h after transfection with 10 nM si-TMEM184B. (E) Cell invasion was determined by Matrigel invasion assay 48 h after transfection with 10 nM si-TMEM184B. *P<0.0001.

XTT assays demonstrated that cell proliferation was significantly inhibited in si-TMEM184B transfectants in comparison with the mock or si-control (Figure 4C).

Moreover, migration assays demonstrated that cell migration activity was significantly inhibited in si-TMEM184B transfectants in comparison with mock or si-control-transfected cells (Figure 4D).

Finally, Matrigel invasion assays demonstrated that cell invasion activity was significantly inhibited in si-TMEM184B transfectants in comparison with mock or si-control-transfected cells (Figure 4E).

Identification of downstream pathways regulated by TMEM184B

There are few reports describing the TMEM184B gene, and the function of this gene is still unknown. Therefore, we investigated the molecular pathways regulated by TMEM184B in cancer cells using genome-wide gene expression analysis in si-TMEM184B transfectants.

A total of 553 genes were commonly downregulated (log2 ratio <−1.0) in si-TMEM184B transfectants in both of SAS and HSC3 cell lines. We also assigned the downregulated genes to KEGG pathways using the GENECODIS program and identified a total of 23 pathways as significantly enriched annotated pathways (Table 4A). Among these pathways, we focused on genes in the ‘regulation of actin cytoskeleton pathways' category (Table 4B). The top three significantly enriched pathways and the genes involved in these pathways are listed in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Table 4A. Significantly enriched KEGG pathways regulated by Si-TMEM184B.

| Number of genes | Annotations | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | (KEGG) 03030: DNA replication | 3.81E-20 |

| 25 | (KEGG) 04110: Cell cycle | 2.02E-19 |

| 10 | (KEGG) 03430: Mismatch repair | 2.55E-11 |

| 14 | (KEGG) 04114: Oocyte meiosis | 3.55E-08 |

| 9 | (KEGG) 03410: Base excision repair | 3.81E-08 |

| 8 | (KEGG) 03440: Homologous recombination | 7.63E-08 |

| 9 | (KEGG) 03420: Nucleotide excision repair | 1.78E-07 |

| 11 | (KEGG) 04914: Progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation | 1.30E-06 |

| 11 | (KEGG) 00240: Pyrimidine metabolism | 2.62E-06 |

| 9 | (KEGG) 04115: p53 signaling pathway | 1.08E-05 |

| 7 | (KEGG) 05322: Systemic lupus erythematosus | 4.37E-03 |

| 11 | (KEGG) 04810: Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 4.39E-03 |

| 6 | (KEGG) 05210: Colorectal cancer | 4.74E-03 |

| 9 | (KEGG) 00230: Purine metabolism | 7.36E-03 |

| 5 | (KEGG) 04978: Mineral absorption | 1.04E-02 |

| 6 | (KEGG) 04350: TGF-beta signaling pathway | 1.45E-02 |

| 12 | (KEGG) 05200: Pathways in cancer | 2.70E-02 |

| 5 | (KEGG) 04610: Complement and coagulation cascades | 2.72E-02 |

| 5 | (KEGG) 03018: RNA degradation | 2.75E-02 |

| 3 | (KEGG) 01040: Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 2.77E-02 |

| 5 | (KEGG) 05100: Bacterial invasion of epithelial cells | 2.77E-02 |

| 7 | (KEGG) 05012: Parkinson's disease | 2.80E-02 |

| 4 | (KEGG) 05219: Bladder cancer | 2.83E-02 |

Abbreviation: KEGG=Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes.

Table 4B. Regulation of genes related to the actin cytoskelton.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | SAS log2 ratio | HSC3 log2 ratio | HNSCC log2 ratio (GSE 9638) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIAPH3 | Diaphanous homolog 3 (Drosophila) | −1.83 | −3.34 | 0.83 |

| ARPC5 | Actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 5, 16kDa | −1.77 | −1.54 | 0.15 |

| BDKRB2 | Bradykinin receptor B2 | −2.73 | −1.27 | −1.86 |

| IQGAP3 | IQ motif containing GTPase activating protein 3 | −1.07 | −1.74 | 1.11 |

| FGFR3 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 | −2.22 | −1.00 | −0.60 |

| BDKRB1 | Bradykinin receptor B1 | −1.17 | −1.94 | −2.27 |

| RHOA | Ras homolog gene family, member A | −2.51 | −3.09 | −0.34 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | −1.37 | −1.40 | 1.83 |

| GNG12 | Guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), gamma 12 | −2.42 | −2.93 | −1.03 |

| CD14 | CD14 molecule | −1.00 | −1.39 | −0.64 |

| ITGB4 | Integrin, beta 4 | −1.53 | −1.37 | 1.09 |

Abbreviation: HNSCC=head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Discussion

A growing body of evidence has shown that miRNAs are involved in several biological processes and are tightly correlated with human oncogenesis and metastasis (Nelson and Weiss, 2008). Recent studies from our laboratory have identified a variety of novel SCC molecular pathways regulated by tumour-suppressive miRNAs. Moreover, the miR-1/133a cluster has been shown to regulate actin cytoskeletal pathways, the miR-29a and miR-218 have been shown to regulate laminin-integrin pathways (Kinoshita et al, 2012a; Kinoshita et al, 2013), and miR-874 has been shown to target histone deacetylase pathways based on the miRNA expression signatures of head and neck SCC (Nohata et al, 2011c). Evaluation of miRNA expression signatures using cancer specimens is an indispensable tool for cancer research. In this study, we have newly constructed the OSCC miRNA signature and identified several differentially expressed miRNAs in OSCC tissues. To compare with PCR-based SCC miRNA signatures from our previous studies, miR-143, miR-139-5p, miR-30a-3p, and miR-375 were downregulated in all SCC miRNA signatures. Previous studies showed that miR-143 and miR-139-5p act as tumour suppressors in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and laryngeal SCC (Zhong et al, 2013; Luo et al, 2014). Our recent data on maxillary sinus, hypopharyngeal, and oesophageal SCCs have suggested that miR-375 is frequently downregulated and functions as a tumour suppressor that targets several oncogenic genes in cancer cells (Nohata et al, 2011b; Kinoshita et al, 2012b). These findings suggested the relevance of the OSCC miRNA signature provided in this study. Therefore, elucidation of the SCC molecular pathways mediated by tumour-suppressive miRNAs will contribute to our understanding of SCC oncogenesis and metastasis.

In the present study, we focused on miR-26a and miR-26b because the expression levels of these miRNAs were reduced in the OSCC signature and the functions of these miRNAs in OSCC cells are not known. Our data showed that both miR-26a and miR-26b were significantly reduced in OSCC specimens, and restoration of these miRNAs inhibited cancer cell migration and invasion, providing insights into the functional roles of miR-26a and miR-26b as tumour suppressors in OSCC cells. Silencing of protein-coding RNAs and miRNAs are well recognised by aberrant DNA methylation and epigenetic modification (Baylin, 2001). Aberrant DNA hypermethylation by overexpression of DNMT3b caused the silencing of miR-26a/b in breast cancer cell lines (Sandhu et al, 2012). Expression of miR-26a was increased by treatment of 5-aza-2′deoxycytidine in a prostate cancer cell line (Borno et al, 2012). These results indicated that silencing of miR-26a/b in cancer cells was caused by epigenetic modification, especially aberrant DNA hypermethylation. Further detailed analysis is necessary to understand the molecular mechanism of miR-26a/b silencing in OSCC cells.

Previous studies have shown that miR-26a and miR-26b act as tumour suppressors in several types of cancers targeting oncogenic genes, such as breast cancer (Li et al, 2013; Li et al, 2014), nasopharyngeal carcinoma(Lu et al, 2011), and hepatocellular carcinoma (Zhao et al, 2014). More recently, the overexpression of miR-26a inhibited tongue SCC cell proliferation and promoted cell apoptosis (Jia et al, 2013). These findings were consistent with our present results, suggesting that miR-26a and miR-26b function as tumour suppressors in this disease. The tumour-suppressive function of miR-26a was also confirmed in in vivo models of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric cancer (Lu et al, 2011; Deng et al, 2013). In contrast, miR-26a promoted the development of cancer cells in nude mice in ovarian cancer (Shen et al, 2014). On the basis of our in vitro data, the further analysis of miR-26a/b in OSCC using the animal model is necessary.

A single miRNA may regulate multiple protein-coding genes; indeed, bioinformatic studies have shown that miRNAs regulate more than 30–60% of the protein-coding genes in the human genome (Lewis et al, 2005). Reduced expression of tumour-suppressive miRNAs may cause the overexpression of oncogenic genes in cancer cells. To better understand OSCC oncogenesis and metastasis, we identified miR-26a/b target genes using in silico analysis. Recent miRNA studies in our laboratory have utilised this strategy to identify novel molecular targets and pathways regulated by tumour-suppressive miRNAs in several cancers, including head and neck SCC (Kinoshita et al, 2013).

In this study, we identified TMEM184B as a target of tumour-suppressive miR-26a/b and validated the direct binding of this miRNA to the 3′-UTR of TMEM184B using luciferase reporter assays. TMEM184B encodes a transmembrane protein and is located on chromosome 22q12, as shown by several large-scale cDNA cloning projects (Matsuda et al, 2003). However, the function of the TMEM184B protein product is still unknown. Our present data showed that TMEM184B was upregulated in OSCC clinical specimens, and silencing of TMEM184B significantly suppressed cancer cell migration and invasion in cancer cells. We also investigated the expression status of TMEM184B in other types of cancers by using GEO database. GEO expression data showed that the expression of TMEM184B was significantly upregulated in cancer tissues compared to with normal tissues in lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreas cancer, and renal cell carcinoma (Supplementary Figure 4). This is the first report that TMEM184B promotes cancer cell migration and invasion, and is directly regulated by tumour-suppressive miRNAs, suggesting that this target has an oncogenic function in cancer cells.

Furthermore, to elucidate the functional significance of TMEM184B in cancer cells, we investigated the downstream pathways and genes regulated by TMEM184B using siRNA-mediated knockdown of TMEM184B. Several molecular pathways were selected as enriched pathways by KEGG annotation, such as ‘DNA replication', ‘Cell cycle', and ‘Mismatch repair'. It is important to investigate the functional role of TME184B-mediated signalling using genes involved in these pathways.

In particular, we focused on the category ‘Regulation of actin cytoskeletal pathway' based on the phenotype of cancer cells following induction of miR-26a/b or silencing of TMEM184B. We also investigated the expression levels of 11 genes that were involved in the ‘Regulation of actin cytoskeleton pathway' by using GEO (accession number; GSE9638) expression data. Among them, three genes (IQGAP3, EGFR, and ITGB4) were upregulated in clinical specimens and these genes were reduced by si-TMEM184B transfectant cells (Supplementary Figure 5). These data indicated that the three genes were downstream oncogenic genes of the miR-26a/b-TMEM184b axis regulation in OSCC cells. Activation of growth-factor receptors and integrins can promote the exchange of GDP for GTP on RHO proteins, and GTP-bound RHO proteins interact with a range of molecules to modulate their activity and localisation (Jaffe and Hall, 2005). During the progression of metastasis, cancer cells acquire altered morphological characteristics and the ability to traverse tissue boundaries. RHO family proteins and proteins interacting with RHO family proteins are involved in cancer cell morphological and motility changes (Hanna and El-Sibai, 2013). The Ras GTPase-activating-like protein (IQGAP) family comprises three members (IQGAP1-3) and these function as contribute to several cellular processes including cell adhesion, migration, and invasion (Noritake et al, 2005). A recent study showed that overexpression of IQGAP3 promoted cancer cell growth, migration, and invasion in lung cancer cell lines (Yang et al, 2014). Thus, our findings suggested that the downregulation of miR-26a/b enhanced the expression of TMEM184B and activated the actin cytoskeleton pathways, thereby promoting cancer cell migration and invasion. As such, the tumour-suppressive miR-26a/b-TMEM184B axis might serve as a therapeutic target for cancer metastasis. Confirmation of these data using an in vivo mouse model is essential to support the conclusions of our in vitro results within the context of OSCC oncogenesis and metastasis.

Conclusions

Downregulation of miR-26a/b was identified based on the miRNA expression signature of OSCC in this study. miR-26a and miR-26b were shown to function as tumour suppressors in OSCC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that tumour-suppressive miR-26a and miR-26b directly regulated TMEM184B in OSCC cells. Moreover, TMEM184B was upregulated in OSCC clinical specimens and contributed to cancer cell migration and invasion, indicating that it functioned as an oncogene. The identification of novel molecular pathways and targets regulated by miR-26a/b may lead to a better understanding of OSCC and the development of new therapeutic strategies to treat this disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the KAKENHI (grant nos. (C) 24592590 and (C) 23592351) and Futaba Electronics Memorial Foundation.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylin S. DNA methylation and epigenetic mechanisms of carcinogenesis. Dev Biol (Basel) 2001;106:85–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A, Roy R, Snijders AM, Hamilton G, Paquette J, Tokuyasu T, Bengtsson H, Jordan RC, Olshen AB, Pinkel D, Schmidt BL, Albertson DG. Two distinct routes to oral cancer differing in genome instability and risk for cervical node metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7024–7034. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borno ST, Fischer A, Kerick M, Falth M, Laible M, Brase JC, Kuner R, Dahl A, Grimm C, Sayanjali B, Isau M, Rohr C, Wunderlich A, Timmermann B, Claus R, Plass C, Graefen M, Simon R, Demichelis F, Rubin MA, Sauter G, Schlomm T, Sultmann H, Lehrach H, Schweiger MR. Genome-wide DNA methylation events in TMPRSS2-ERG fusion-negative prostate cancers implicate an EZH2-dependent mechanism with miR-26a hypermethylation. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:1024–1035. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Liu Y, Jin X, Lu W, Liu J, Xia Z, Yuan Q, Zhao X, Xu N, Liang S. MicroRNA-26a regulates glucose metabolism by direct targeting PDHX in colorectal cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:443. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M, Tang HL, Lu XH, Liu MY, Lu XM, Gu YX, Liu JF, He ZM. miR-26a suppresses tumor growth and metastasis by targeting FGF9 in gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto I, Kinoshita T, Hanazawa T, Kikkawa N, Chiyomaru T, Enokida H, Yamamoto N, Goto Y, Nishikawa R, Nakagawa M, Okamoto Y, Seki N. Identification of tumour suppressive microRNA-451a in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma based on microRNA expression signature. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:386–394. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y, Kojima S, Nishikawa R, Enokida H, Chiyomaru T, Kinoshita T, Nakagawa M, Naya Y, Ichikawa T, Seki N. The microRNA-23b/27b/24-1 cluster is a disease progression marker and tumor suppressor in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5:7748–7759. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y, Nishikawa R, Kojima S, Chiyomaru T, Enokida H, Inoguchi S, Kinoshita T, Fuse M, Sakamoto S, Nakagawa M, Naya Y, Ichikawa T, Seki N. Tumour-suppressive microRNA-224 inhibits cancer cell migration and invasion via targeting oncogenic TPD52 in prostate cancer. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1973–1982. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna S, El-Sibai M. Signaling networks of Rho GTPases in cell motility. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1955–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O. Gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Science. 2008;319:1785–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1151651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio MV, Croce CM. MicroRNAs in cancer: small molecules with a huge impact. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5848–5856. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia LF, Wei SB, Gan YH, Guo Y, Gong K, Mitchelson K, Cheng J, Yu GY. Expression, regulation and roles of miR-26a and MEG3 in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2013;135:2282–2293. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M, Seki N, Kikkawa N, Fujimura L, Hoshino I, Akutsu Y, Chiyomaru T, Enokida H, Nakagawa M, Matsubara H. miR-145, miR-133a and miR-133b: Tumor-suppressive miRNAs target FSCN1 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2804–2814. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa N, Hanazawa T, Fujimura L, Nohata N, Suzuki H, Chazono H, Sakurai D, Horiguchi S, Okamoto Y, Seki N. miR-489 is a tumour-suppressive miRNA target PTPN11 in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (HSCC) Br J Cancer. 2010;103:877–884. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Hanazawa T, Nohata N, Kikkawa N, Enokida H, Yoshino H, Yamasaki T, Hidaka H, Nakagawa M, Okamoto Y, Seki N. Tumor suppressive microRNA-218 inhibits cancer cell migration and invasion through targeting laminin-332 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1386–1400. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Hanazawa T, Nohata N, Okamoto Y, Seki N. The functional significance of microRNA-375 in human squamous cell carcinoma: aberrant expression and effects on cancer pathways. J Hum Genet. 2012;57:556–563. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Nohata N, Hanazawa T, Kikkawa N, Yamamoto N, Yoshino H, Itesako T, Enokida H, Nakagawa M, Okamoto Y, Seki N. Tumour-suppressive microRNA-29s inhibit cancer cell migration and invasion by targeting laminin-integrin signalling in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2636–2645. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Nohata N, Watanabe-Takano H, Yoshino H, Hidaka H, Fujimura L, Fuse M, Yamasaki T, Enokida H, Nakagawa M, Hanazawa T, Okamoto Y, Seki N. Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 5 (ARPC5) contributes to cell migration and invasion and is directly regulated by tumor-suppressive microRNA-133a in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1770–1778. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Nohata N, Yoshino H, Hanazawa T, Kikkawa N, Fujimura L, Chiyomaru T, Kawakami K, Enokida H, Nakagawa M, Okamoto Y, Seki N. Tumor suppressive microRNA-375 regulates lactate dehydrogenase B in maxillary sinus squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:185–193. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Kong X, Zhang J, Luo Q, Li X, Fang L. MiRNA-26b inhibits proliferation by targeting PTGS2 in breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Li X, Kong X, Luo Q, Zhang J, Fang L. MiRNA-26b inhibits cellular proliferation by targeting CDK8 in breast cancer. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:558–565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, He ML, Wang L, Chen Y, Liu X, Dong Q, Chen YC, Peng Y, Yao KT, Kung HF, Li XP. MiR-26a inhibits cell growth and tumorigenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma through repression of EZH2. Cancer Res. 2011;71:225–233. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo HN, Wang ZH, Sheng Y, Zhang Q, Yan J, Hou J, Zhu K, Cheng Y, Xu YL, Zhang XH, Xu M, Ren XY. MiR-139 targets CXCR4 and inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of laryngeal squamous carcinoma cells. Med Oncol. 2014;31:789. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0789-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda A, Suzuki Y, Honda G, Muramatsu S, Matsuzaki O, Nagano Y, Doi T, Shimotohno K, Harada T, Nishida E, Hayashi H, Sugano S. Large-scale identification and characterization of human genes that activate NF-kappaB and MAPK signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2003;22:3307–3318. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KM, Weiss GJ. MicroRNAs and cancer: past, present, and potential future. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3655–3660. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa R, Goto Y, Kojima S, Enokida H, Chiyomaru T, Kinoshita T, Sakamoto S, Fuse M, Nakagawa M, Naya Y, Ichikawa T, Seki N. Tumor-suppressive microRNA-29s inhibit cancer cell migration and invasion via targeting LAMC1 in prostate cancer. Int J Oncol. 2014;45:401–410. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa R, Goto Y, Sakamoto S, Chiyomaru T, Enokida H, Kojima S, Kinoshita T, Yamamoto N, Nakagawa M, Naya Y, Ichikawa T, Seki N. Tumor-suppressive microRNA-218 inhibits cancer cell migration and invasion via targeting of LASP1 in prostate cancer. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:802–811. doi: 10.1111/cas.12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohata N, Hanazawa T, Kikkawa N, Mutallip M, Fujimura L, Yoshino H, Kawakami K, Chiyomaru T, Enokida H, Nakagawa M, Okamoto Y, Seki N. Caveolin-1 mediates tumor cell migration and invasion and its regulation by miR-133a in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:209–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohata N, Hanazawa T, Kikkawa N, Mutallip M, Sakurai D, Fujimura L, Kawakami K, Chiyomaru T, Yoshino H, Enokida H, Nakagawa M, Okamoto Y, Seki N. Tumor suppressive microRNA-375 regulates oncogene AEG-1/MTDH in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) J Hum Genet. 2011;56:595–601. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohata N, Hanazawa T, Kikkawa N, Sakurai D, Fujimura L, Chiyomaru T, Kawakami K, Yoshino H, Enokida H, Nakagawa M, Katayama A, Harabuchi Y, Okamoto Y, Seki N. Tumour suppressive microRNA-874 regulates novel cancer networks in maxillary sinus squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:833–841. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohata N, Hanazawa T, Kikkawa N, Sakurai D, Sasaki K, Chiyomaru T, Kawakami K, Yoshino H, Enokida H, Nakagawa M, Okamoto Y, Seki N. Identification of novel molecular targets regulated by tumor suppressive miR-1/miR-133a in maxillary sinus squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2011;39:1099–1107. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noritake J, Watanabe T, Sato K, Wang S, Kaibuchi K. IQGAP1: a key regulator of adhesion and migration. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2085–2092. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu R, Rivenbark AG, Coleman WB. Loss of post-transcriptional regulation of DNMT3b by microRNAs: a possible molecular mechanism for the hypermethylation defect observed in a subset of breast cancer cell lines. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:721–732. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Song M, Liu J, Qiu G, Li T, Hu Y, Liu H. MiR-26a promotes ovarian cancer proliferation and tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikner J, Grobe A, Pantel K, Riethdorf S. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and circulating tumour cells. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5:114–124. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Zhao W, Xu QW, Wang XS, Zhang Y, Zhang J. IQGAP3 promotes EGFR-ERK signaling and the growth and metastasis of lung cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N, Wang R, Zhou L, Zhu Y, Gong J, Zhuang SM. MicroRNA-26b suppresses the NF-kappaB signaling and enhances the chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting TAK1 and TAB3. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:35. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W, He B, Zhu C, Xiao L, Zhou S, Peng X. [MiR-143 inhibits migration of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by negatively regulating GLI3 gene] Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2013;33:1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.