Abstract

Gastrointestinal bleeding is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. The management of gastrointestinal bleeding is often challenging, depending on its location and severity. To date, widely accepted hemostatic treatment options include injection of epinephrine and tissue adhesives such as cyanoacrylate, ablative therapy with contact modalities such as thermal coagulation with heater probe and bipolar hemostatic forceps, noncontact modalities such as photodynamic therapy and argon plasma coagulation, and mechanical hemostasis with band ligation, endoscopic hemoclips, and over-the-scope clips. These approaches, albeit effective in achieving hemostasis, are associated with a 5–10% rebleeding risk. New simple, effective, universal, and safe methods are needed to address some of the challenges posed by the current endoscopic hemostatic techniques. The use of a novel hemostatic powder spray appears to be effective and safe in controlling upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Although initial reports of hemostatic powder spray as an innovative approach to manage gastrointestinal bleeding are promising, further studies are needed to support and confirm its efficacy and safety.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the technical feasibility, clinical efficacy, and safety of hemostatic powder spray (Hemospray, Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA) as a new method for managing gastrointestinal bleeding.

In this review article, we performed an extensive literature search summarizing case reports and case series of Hemospray for the management of gastrointestinal bleeding. Indications, features, technique, deployment, success rate, complications, and limitations are discussed.

The combined technical and clinical success rate of Hemospray was 88.5% (207/234) among the human subjects and 81.8% (9/11) among the porcine models studied. Rebleeding occurred within 72 hours post-treatment in 38 patients (38/234; 16.2%) and in three porcine models (3/11; 27.3%). No procedure-related adverse events were associated with the use of Hemospray.

Hemospray appears to be a safe and effective approach in the management of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Keywords: gastrointestinal bleeding, Hemospray, hemostatic powder spray

Introduction

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States with an estimated 20,000 deaths per year [El-Tawil, 2012]. Currently, endoscopic hemostasis is accepted as a first-line treatment modality in the management of GIB and has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing the rate of rebleeding, the need for surgical intervention, and mortality [Pedroto et al. 2012].

Widely used treatment modalities for GIB include injection therapy, ablative therapies (contact and noncontact), and mechanical hemostasis [Babiuc et al. 2013]. Injection of epinephrine induces vasospasm and thrombosis of the bleeding vessels [Kubba and Palmer, 1996] resulting in control of bleeding in approximately 80% of cases [Calvet et al. 2004]. It is relatively easy to perform and facilitates the subsequent use of more permanent ablative or mechanical treatment options [Cappell and Friedel, 2008]. Adverse events of mucosal injection of epinephrine are infrequent and include perforation or tissue ischemia [Kovacs, 2008; Chung et al. 1996]. Histoacryl tissue adhesive (2-N-butyl-cyanoacrylate) injection is mainly used for bleeding gastric varices with reported hemostatic success rates between 95% and 100% [Fry et al. 2008].

Thermal coagulation uses heat to coagulate tissue proteins, causes tissue edema and vasoconstriction, and activates the clotting cascade with subsequent cessation of bleeding [Jensen and Machicado, 2005]. Potential adverse events of thermal coagulation include immediate rebleeding due to tissue adherence to the probe upon removal [Cappell and Friedel, 2008] and, rarely, deep tissue injury [Jensen and Machicado, 2009].

Mechanical hemostasis with hemoclips controls GIB by interrupting the blood supply to the bleeding site [Cappell, 2010]. Endoscopists commonly prefer metallic hemoclips or endoclips, which have a 94% initial success rate for control of bleeding [Jensen and Machicado, 2009; Lin et al. 2007]. Other mechanical modalities include over-the-scope clips (OTSCs) and hemostatic forceps. OTSCs have reportedly been used to achieve hemostasis in upper and lower GIB including bleeding from gastric ulcers, difficult to reach posterior duodenal wall lesions, and gastric tumors [Mönkemüller et al. 2012; Chan et al. 2014]. OTSCs have variable success rates, ranging from 71% to 100% in the management of GIB [Singhal et al. 2013]. Hemostatic forceps have an estimated 96% success rate in the management of bleeding from gastric ulcers [Nagata et al. 2010]. Hemoclips can quickly, precisely, and securely control bleeding [Singhal et al. 2013]. However, the use of hemoclips is often technically challenging and requires expertise for accurate and precise deployment. Limitations and adverse events of hemoclips include occasional early spontaneous dislodgement (dislodgment rates vary with type of clip used), risk of perforation [Nagata et al. 2010], and relative difficulty of deployment in hard to reach areas such as the lesser curvature of the stomach, the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb, or the gastric cardia [Cho et al. 2009].

Endoscopic band ligation (EBL) is another type of mechanical hemostasis used in the management of bleeding esophageal varices [Garcia-Tsao et al. 2007]. Owing to its established efficacy and low rate of adverse events, EBL is preferred over sclerotherapy for esophageal variceal bleeding [Kravetz, 2007]. Drawbacks of EBL include dysphagia, post-banding mucosal ulcerations and esophageal strictures. Also there is relative technical difficulty of deployment in a retroflexed position [Liu et al. 2008].

Endoscopic hemostasis for post-polypectomy bleeding can be achieved with the use of detachable snares or clips [Di Giorgio et al. 2004]. The use of an endoloop to ligate the stalk of a large polyp before snare polypectomy and therefore minimize the risk of post-polypectomy bleeding has been described [Katsinelos et al. 2006]. However, flat and indurated lesions may pose a significant challenge as the use of detachable snares or clips may not be effective in this setting [Cappell, 2010]. Another mechanical hemostatic modality is endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided angiotherapy. Conventionally, EUS-guided angiotherapy is employed when other standard hemostatic approaches have failed. Reported cases of its use have included gastric variceal hemorrhage, refractory hemosuccus pancreaticus, Dieulafoy lesions, duodenal ulcers, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors [Levy et al. 2008; Levy and Song, 2013]. It is reported to have a 96% success rate in controlling GIB [Binmoeller et al. 2011]. Radiologic embolotherapy is considered to be a salvage therapy with reported technical success rates of 69–100% and rebleeding rates of 10–30% within 30 days of initial application [Luchtefeld et al. 2000; Weldon et al. 2008]. A major adverse event of embolotherapy is the increased risk of bowel ischemia or infarct after arterial embolization, which has been reported to range from 0% to 22% [Maleux et al. 2009].

Alternative modalities in the management of GIB are needed, as the current methods have varying limitations in efficacy, require expertise, and are occasionally associated with adverse events. A relatively simple, safe and effective method of endoscopic hemostasis is the use of hemostatic powders. Such powders were used in the battlefields to control external bleeding [Babiuc et al. 2013], however, only recently they have been studied and successfully applied in the gastrointestinal tract in both animal and human subjects. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are three hemostatic powders in use for control of GIB: the TC-325 (Hemospray, Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, USA), the Ankaferd Blood Stopper (Ankaferd Ila Kozmetik A- Turkish Food and Drug Administration), and EndoClot (EndoClot Plus, Inc.) [Barkun et al. 2013; Barkun, 2013]. The most widely and recently studied hemostatic powder is the Hemospray, which is marketed in many countries; however, it has not yet been approved for use in the United States. This review article evaluates the technical feasibility, safety, efficacy, and adverse outcomes of Hemospray in the management of both upper and lower GIB in humans and animal models.

Materials and methods

We conducted an extensive English literature search using Pubmed, Medline, Medscape, and Google to identify peer-reviewed original research and review articles using the keywords ‘endoscopy techniques’, ‘endoscopic hemostasis’, ‘Hemospray’, ‘hemostatic powder’, and ‘treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding’. The search period included articles published until August 2014. We selected studies involving humans and animal models and manually searched the references to identify additional relevant studies. Inclusion criteria for evaluation were the technical success, feasibility, safety, efficacy, and adverse outcomes of Hemospray in the management of both upper and lower GIB at various locations and severity. In a recent article by Holster and colleagues, technical success was defined as continuous hemostasis observed after 3–5 minutes of Hemospray use [Holster et al. 2014]. Search results yielded case reports and case series. Hemospray to date is not licensed for use in the United States.

Mechanism of action

Hemostatic powder is an inorganic powder that does not attach to nonbleeding surfaces and, thus, only affects areas of active bleeding [Barkun et al. 2013; Barkun, 2013]. The powder demonstrates adhesive properties and dehydrates tissue through absorption of water molecules, causing an increase in its volume [Barkun et al. 2013; Barkun, 2013]. It acts as a physical barrier upon contact with moisture and it concentrates clotting factors at the site of bleeding with subsequent clot formation [Babiuc et al. 2013]. Hemospray is neither taken up nor broken down by the mucosa and therefore does not appear to cause any local or systemic damage [Sung et al. 2011]. Hemospray is administered with a syringe, a 7-French or 10-French catheter inserted into the endoscope channel and an introducer handle with a built-in carbon dioxide canister, which ejects the powder out of the catheter and onto the bleeding site [Sung et al. 2011] (Figures 1–3).

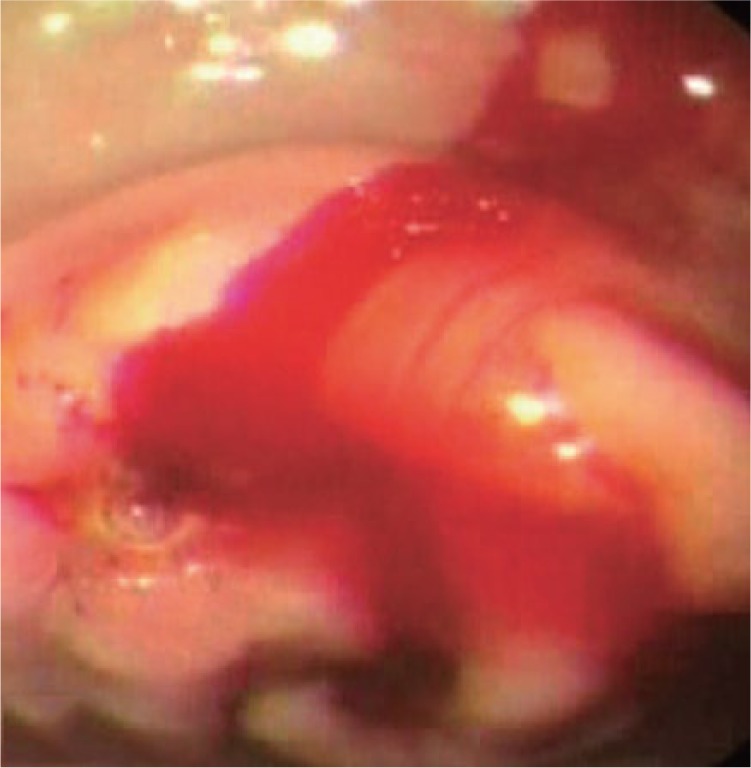

Figure 1.

Endoscopic view of actively bleeding gastric ulcer.

(Reproduced from Leung Ki and Lau [2012], an open access article under terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License from Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.)

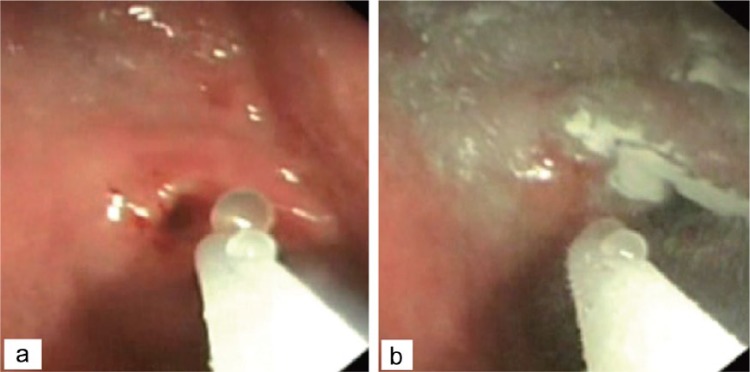

Figure 2.

Application of Hemospray on bleeding ulcer.

(Reproduced from Leung Ki and Lau [2012], an open access article under terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License from Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.)

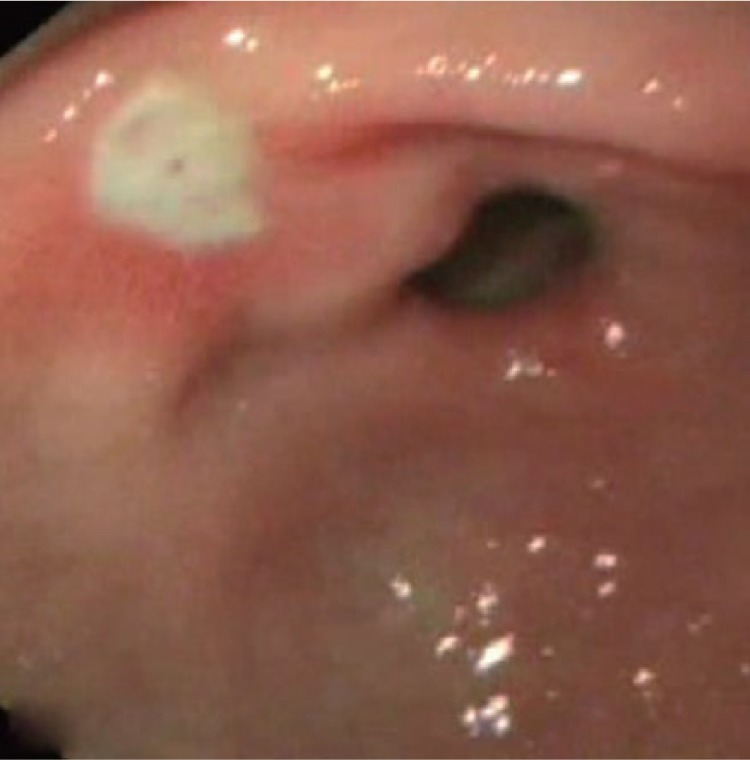

Figure 3.

Successful achievement of hemostasis after Hemospray application.

(Reproduced from Leung Ki and Lau [2012], an open access article under terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License from Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.)

Results

A total of 19 original published articles were considered appropriate for inclusion in this review article. These were studies performed in the United Kingdom, United States, Japan, Italy, Hong Kong, Canada, France, Belgium, The Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, Spain, Switzerland, Denmark, and Egypt. Of the 19 studies, 6 were case reports [Fujita, 2012; Granata et al. 2013; Sargon and Laurie, 2013; Stanley et al. 2013; Paganelli et al. 2014; Moosavi et al. 2013] and 13 were case series. A total of 17 studies studied humans (234 cases) [Sung et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2012; Fujita et al. 2012; Granata et al. 2013; Leblanc et al. 2013; Ibrahim et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2013; Sargon and Laurie, 2013; Stanley et al. 2013; Soulellis et al. 2013; Yau et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2014; Holster et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014; Paganelli et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2014; Moosavi et al. 2013], while the remaining two performed in the United States involved porcine models (11 cases) [Giday et al. 2011, 2013]. The mean age of human subjects was 54.9 years. 69.2% (162/234) of the patients included in those studies were males and 29.9% (70/234) were females. Subject gender was not reported in two case reports [Granata et al. 2013; Moosavi et al. 2013]. All cases are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Summary of reports on the use of Hemospray for endoscopic hemostasis in humans.

| Study | Mean Age (yrs) | Sample size | Sex | Location of bleed | Lesion size (mm) | Source of bleeding | Forrest Classification | Prior treatment | Delivery device | Subsequent treatments | Number of applications | Successful hemostasis | Rebleeding | Mortality 30 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sung et al. [2011], Hong Kong | 60.2 | 20 | 18M 2F |

Stomach (6/20) Duodenum (14/20) |

NR | Arterial | 1a (1) 1b (19) |

None | 21g of Hemospray catheter and introducer with CO2 canister | None | 1=13/20 2=5/20 >2=2/20 |

19/20 [95%] | 1/20 | None |

| Chen et al. [2012], Canada | 74 69 58 49 53 |

1 1 1 1 1 |

F M F F F |

Gastric Antrum Distal esophagus Duodenal bulb Duodenal flexure Gastric cardia |

Large Large 58×36×39 NR NR |

Gastric adenoCA AdenoCA AdenoCA pancreatic head Breast CA Non-small cell lung CA |

N/A | None None None None Epi and APC |

20 g of Hemospray powder in canister 15 g of Hemospray powder in canister 20g of Hemospray powder in canister 20g of Hemospray powder in canister 20g of Hemospray powder in canister |

None None None None None |

1 1 1 1 2 |

1/1 [100%] 1/1 [100%] 1/1 [100%] 1/1 [100%] 1/1 [100%] |

0/1 0/1 0/1 0/10/1 |

None None None None None |

| Fujita [2012], Japan | 79 | 1 | F | Gastric fundus | 8 | Gastric varices | N/A | Lipiodol injection | 10g of Hemospray powder in canister | None | 1 | 1/1 [100%] | 0/1 | None |

| Granata et al. [2013], Italy | 51 | 1 | NR | Cecum | 30 | NR | N/A | Fibrin glue injection | Hemospray powder in canister | None | 2 | 1/1 [100%] | 0/1 | None |

| Leblanc et al. [2013], France | 67 71 59.7 60.9 |

1 1 3 7 |

M M 2M 1F 5M 2F |

Proximal esophagusGastric cardia Distal esophagus Duodenum |

12 25 23 38.1 |

SCC Intestinal metaplasia with LGD and HGD AdenoCA, and Barrett’s esophagus Tubulovillous adenoma with LGD |

N/A | None None None None |

20 g of Hemospray powder in canister 20 g of Hemospray powder in canister 20 g of Hemospray powder in canister20 g of Hemospray powder in canister |

None None None None |

1 1 1 1 |

1/1 [100%] 1/1 [100%] 3/3 [100%] 7/7 [100%] |

0/1 0/1 0/3 0/7 |

None None None None |

| Ibrahim et al. [2013], Egypt | 61.7 | 9 | 7M 2F | Esophagus and GE junction | NR | Esophageal varices | N/A | None | 21g of Hemospray powder in canister | None | 8/9 (1) 1/9 (2) |

9/9 [100%] | 0/9 | None |

| Smith et al. [2013], UK | 69.8 66 |

3 1 |

2M 1F F |

Antrum Proximal stomach |

NR NR |

PHG PHG |

N/A | APC (1) None |

20g of Hemospray powder in canister 20g of Hemospray powder in canister |

None None |

1 1 |

3/3[100%] 1/1 [100%] |

0/3 0/1 |

None None |

| Sargon and Laurie [2013], United States | 13 | 1 | M | Duodenum | NR | Duodenal ulcer | 1b | Embolization therapy | 25 – 30 g of Hemospray powder in canister | None | 1 | 1/1 [100%] | 0/1 | None |

| Stanley et al. [2013], UK | 37 | 1 | M | Gastric | Large | Gastric varices | N/A | Histoacryl and Lipiodol injections | Hemospray powder in canister | TIPS | 1 | 1/1 [100%] | 0/1 | None |

| Soulellis et al. [2013], Canada | 79 56 82 69 |

1 1 1 1 |

M M M M |

Cecum Recto sigmoid Lower GI tract Rectum |

30 10 350 70 |

Sessile polyp (post-snare cautery, clip) Tubular adenoma; HGD Dieulafoy lesion Radiation proctitis |

N/A | Metal clips Epi, thermal probe, clip 5 metal clips, Epi APC |

20 g of Hemospray powder in canister 30 g of Hemospray powder in canister 20 g of Hemospray in canister 20 g of Hemospray in canister |

None None None None |

1 1 1 1 |

1/1 [100%] 1/1 [100%] 1/1 [100%] 1/1 [100%] |

0/1 0/1 0/1 0/1 |

None None None None |

| Yau et al. [2014], Canada | 67.6 | 19 | 14M 5F |

Esophagus (1/19) Stomach (5/19) Duodenum (13/19) |

NR | Peptic ulcer (12/19) Dieulafoy lesion (2/19) Mucosal erosion (1/19) Angiodysplasia (1/19) Ampullectomy (1/19) Polypectomy (1/19) Unidentified (1/19) |

1a (4) | Epi (16/19) Thermal probe (10/19) Clips, bands (9/19) Transarterial embolization (2/19) Surgical oversewing (1/19) |

20 g of Hemospray powder in canister | 1/19 | 1 | 18/19 [94.7%] | 7/18 [38.9%] | 5/19 [26.3%] |

| Smith et al. [2013], UK SEAL survey | 69 | 63 | 44M 19F |

Esophagus, Stomach, Duodenum (63) | NR | Gastric ulcers (14/63) Duodenal ulcers (16/63) Post-EMR (7/63) Tumor (5/63) Esophageal ulcer (3/63) Dieulafoy (2/63) GAVE (2/63) Gastritis (2/63) Mallory Weiss (2/63) Sphincterotomy (1/63) Esophagitis (1/63) GIST (1/63) Ampullectomy (1/63) Duodenal diverticulum (1/63) Aortoduodenal fistula (1/63) Duodenal erosions (1/63) Post-HALO® (1/63) Duodenal polyp (1/63) Diffuse duodenal bleeding unknown cause (1/63) |

1a (11) 1b (16) |

Monotherapy (55/63) Second-line therapy (8/63) |

20 g of Hemospray powder in canister | Angiographic embolization (1/8) Bipolar probe, epi (1/8) Clip, Epi, Surgery (1/8) Clip (1/8) Epi, heater probe (1/8) Heater probe, clip |

1 | 47/55 [85%] |

7/47 [15%] | 3/55 [5%] |

| Holster et al. [2014], Spain and Netherlands | 63 | 9 | 5M 4F |

Cecum Ascending colon Transverse colon Rectum |

NR | Colorectal anastomosis (1/9) Rectal ulcer 1/9) Colonic diverticulum (1/9) Cecal adenoCA (1/9) Proctitis (1/9) Polypectomy (4/9): rectum (2), transverse colon (1), ascending colon (1) |

N/A | Monotherapy (6/9) Clips and/or Epi (3/9) |

20 g of Hemospray powder in canister, 10 Fr catheter | None | 1 | 7/9 [77.8%] | 2/9 [22.2%] | None |

| Sulz et al. [2014], Switzerland | 67 | 16 | 13M 3F |

Esophagus (2/16) Stomach (5/16) Duodenum(4/14) Papilla of Vater (2/16) Jejunum (2/16) Anus (1/16) |

NR | Duodenal ulcer Sphincterotomy papilla of vater Esophagus PHG: cardia Gastro-esophageal anastomosis Jejunal Dieulafoy Duodenal ulcer Metastatic gastric melanoma Gastric varices Jejunal tumor ulceration Recurrent anal carcinoma Buried bumper after incision, stomach |

1b (4) N/A (12) |

Monotherapy (2/16) Salvage therapy (14/16) Injection Clip Heater probe APC |

20 g of Hemospray powder in canister, 10 Fr catheter |

Angiographic embolization Surgery |

1 | 15/16 [93.8%] Monotherapy 2/2 [100%] Salvage therapy 13/14 [92.85%] |

2/16 [12.5%] | None |

| Paganelli et al. [2014], Canada | 0.91 | 1 | F | Esophagus | NR | Esophageal ulcer | N/A | Sclerosing agent injection | Hemospray | None | 1 | 1/1 [100%] | 0/1 | None |

| Chen et al. [2014], Canada | NR | 67 | 43 M 24 F |

NVUGIB (21/67) Malignant UGIB (19/67) LGIB (11/67) Intra-procedural bleeding (16/67) |

NR | NR | 1a (3) 1b (10) Remaining N/A |

None | Hemospray | None | 1 | 20/21 [95.2%] 19/19 [100%] 11/11 [100%] 16/16 [100%] |

8/17 [47%] 6/19 [31.6%] 0/11 0/16 |

None 4/19 [21.1%] None None |

| Moosavi et al. [2013], Canada | NR | 1 | NR | Duodenum | NR | Sphincterotomy | N/A | None | 5 g of Hemospray powder in canister | None | 1 | 1/1 [100%] | 0/1 | None |

AdenoCA, adenocarcinoma; APC, argon plasma coagulation; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; N/A, not applicable; NR, not reported; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; Epi, epinephrine; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; GAVE, gastric antral vascular ectasia; NVUGIB, nonvariceal nonmalignant upper gastrointestinal bleeding; UGIB, Upper gastrointestinal bleeding; LGIB, lower gastrointestinal bleeding; PHG, portal hypertensive gastropathy.

Table 2.

Summary of reports describing the use of Hemospray for endoscopic hemostasis in animal models.

| Study | Animal | Sample size | Location of bleed | Lesion Size (mm) | Source of bleeding | Forrest Classification | Prior treatment | Delivery device | Subsequent treatments | Number of applications | Successful hemostasis | Rebleeding | Mortality 30 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giday et al. [2011], United States | Pigs | 5 | Gastric | NR | Gastroepiploic artery | 1a (5) | No | 20 g of Hemospray powder in canister | None | 1 | 5/5 [100%] | 1/5 [20%] | 5/5 |

| Giday et al. [2013], United States | Pigs | 6 | Gastric | NR | Gastroepiploic artery | Forest 1a (3) Forest 1b (3) |

No | 20g of Hemospray powder in canister | None | 1 | 6/6 [100%] | 2/6 [33.3%] | None |

Location of bleeding

Bleeding in the upper gastrointestinal tract was reported in the majority of cases. A total of 66 cases included gastric bleeding (66/234; 28.2%) [Sung et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2012; Fujita, 2012; Leblanc et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2013, 2014; Stanley et al. 2013; Yau et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014; Giday et al. 2011, 2013] and 15 cases of esophageal bleeding (15/234; 6.4%) [Chen et al. 2012; Leblanc et al. 2013; Yau et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014; Paganelli et al. 2014]. A total of 62 cases (62/234; 26.5%) of duodenal bleeding were reported [Sung et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2012; Leblanc et al. 2013; Sargon and Laurie, 2013; Yau et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014; Moosavi et al. 2013]. Ibrahim and colleagues studied nine cases of bleeding at the gastroesophageal junction (9/234; 3.85%) [Ibrahim et al. 2013]. A total of 26 cases of bleeding in the lower gastrointestinal tract (26/234; 11%) were reported [Granata et al. 2013; Soulellis et al. 2013; Holster et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2014].

Size of bleeding source

The mean size of bleeding source was 37.4 mm, with a range from 8 to 350 mm [Chen et al. 2012; Fujita, 2012; Granata et al. 2013; Leblanc et al. 2013; Soulellis et al. 2013; Yau et al. 2014]. Several cases did not report the size of bleeding source [Sung et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2012; Ibrahim et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2013, 2014; Sargon and Laurie, 2013; Holster et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014; Paganelli et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2014; Moosavi et al. 2013; Giday et al. 2011, 2013] and two characterized the bleeding as ‘large’ [Chen et al. 2012; Stanley et al. 2013].

Source of bleeding

Seven studies reported cases of arterial bleeding secondary to acute peptic ulcers and the gastroepiploic artery [Sung et al. 2011; Yau et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2014; Moosavi et al. 2013; Giday et al. 2011, 2013]. There were 12 reported cases of Hemospray use in variceal bleeding [Fujita, 2012; Ibrahim et al. 2013; Stanley et al. 2013; Sulz et al. 2014], 4 in bleeding due to portal hypertensive gastropathy in cirrhotic patients [Smith et al. 2013; Sulz et al. 2014] and 44 cases reported bleeding from malignant tumors such as gastric, pancreatic and anal adenocarcinomas, metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma, melanoma, breast, and non-small cell lung cancers [Chen et al. 2012; Leblanc et al. 2013; Sargon and Laurie, 2013; Holster et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014; Paganelli et al. 2014]. Leblanc and colleagues and Smith and coworkers used hemostatic powder to control bleeding after completion of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) [Leblanc et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2014]. A total of five of the studies reported successfully treated cases of post-polypectomy bleeding from a clipped sessile polyp in the cecum, rectum, transverse and ascending colon, a high-grade tubular adenoma in the rectum, Dieulafoy lesions, and radiation proctitis [Soulellis et al. 2013; Yau et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2014; Holster et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014]. Hemospray efficacy in achieving hemostasis was demonstrated in gastric antral vascular ectasias (GAVE) and in post-sphincterotomy bleeding [Smith et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014; Moosavi et al. 2013]

Forrest classification

Of the 81 bleeding peptic ulcer cases in the human subjects, 38.3% (31/81) were classified as Forrest 1a and 61.7% (50/81) as Forrest 1b. Among the porcine model study group, 72.7% (8/11) were classified as Forrest 1a and 27.3% (3/11) as Forrest 1b (see Tables 1 and 2).

Primary method of treatment

Hemospray was used as the primary and sole treatment modality of endoscopic hemostasis in 83% (194/234) of the cases (see Tables 1 and 2). The remaining 17% (40/234) of the cases were treated with a different hemostatic method (metallic clips, argon plasma coagulation, and epinephrine, lipiodol, fibrin injections, and surgery) prior to application of the hemostatic powder [Chen et al. 2012; Fujita, 2012; Leblanc et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2013; Sargon and Laurie, 2013; Soulellis et al. 2013; Yau et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014].

Technical and clinical success rates

The combined success rate of Hemospray in achieving hemostasis was 88.5% (207/234) among the human subjects and 81.8% (9/11) among the porcine models. Rebleeding occurred within 72 hours post-treatment in 16.2% (38/234) of patients [Sung et al. 2011; Yau et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2014; Holster et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2014] and in 27.3% (3/11) of animal models [Giday et al. 2011, 2013]. The patients who did not respond to Hemospray were eventually treated with one or more of the following modalities: electrocautery, hemoclips, epinephrine injection, transarterial embolization, or surgery [Sung et al. 2011; Yau et al. 2014; Sulz et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2014].

Adverse events and limitations

No procedure-related adverse events were associated with the use of Hemospray. Rare adverse events of Hemospray may include embolism, intestinal obstruction, and allergic reaction to its components. However, given the relatively low-pressure system used in the canister during deployment of the powder, the risk of embolism is minuscule [Babiuc et al. 2013]. Reports of hemostatic powder dislodgement from the gastrointestinal mucosa approximately 48 hours after its use may theoretically cause intestinal obstruction [Sung et al. 2011]. However, review of the literature did not reveal any of these potential adverse events.

Although the Hemospray is technically easy to apply, the endoscopist should avoid deployment with the endoscope too close to the mucosa, because the powder may obstruct the view or clog the delivery catheter. It is suggested that proper time should be allowed for the powder to settle before any aspiration attempt, as this may block the operating channel or the delivery catheter. Also, using the hemostatic powder before other hemostatic modalities, may lead to loss of landmarks and prohibit any alternative hemostatic approach [Barkun et al. 2013; Barkun, 2013]. Endoscopists should heed the theoretical risk of perforation due to carbon dioxide pressure used for the Hemospray application. Pressures may reach as high as 55 mmHg and may tear the colonic wall if the catheter is placed too close or in contact with a lesion in thin areas such as the cecum or into a diverticulum [Soulellis et al. 2013].

Summary and future directions

The reported findings on the use of Hemospray are promising. Hemospray is a novel treatment modality and a therapeutic alternative for difficult cases of GIB and appears relatively easy to use in everyday gastroenterology practice. It may be an alternative or a complement to the current hemostatic techniques in areas that may be technically difficult to access, such as the lesser curvature of the stomach, posterior wall of the duodenal bulb, and gastric cardia, and in large bleeding areas due to ulcers, tumors, GAVE or post-EMR. We identified potential limitations in the cases reviewed. Although the literature on Hemospray use is quickly expanding, the number of subjects studied thus far is small. Large randomized, prospective studies are needed to further characterize the safety and efficacy of Hemospray in treating various types of GIB. As noted by Babiuc and colleagues, most of these cases involved treatment of relatively mild bleeding in human subjects (61.7% Forrest 1b bleeding lesions) [Babiuc et al. 2013]. Also, the number of female participants in these studies was disproportionally low (70/232; 30.2%). Further studies are needed to investigate the efficacy of Hemospray in colonic bleeding. Hemospray to date is not licensed for use in the United States. Overall, Hemospray has a potential role in endoscopic hemostasis or may serve as an adjunct to other established non endoscopic therapies such as surgery, embolization, or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for the management of GIB.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest or financial relationships with the company that produces or distributes the treatment modality described in the review article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributor Information

Kinesh Changela, Division of Gastroenterology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, 121 DeKalb Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA.

Haris Papafragkakis, Division of Gastroenterology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

Emmanuel Ofori, Division of Gastroenterology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

Mel A. Ona, Division of Gastroenterology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

Mahesh Krishnaiah, Division of Gastroenterology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

Sushil Duddempudi, Division of Gastroenterology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

Sury Anand, Division of Gastroenterology, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

References

- Babiuc R., Purcarea M., Sadagurshi R., Negreanu L. (2013) Use of Hemospray in the treatment of patient with acute UGIB – short review. J Med Life 6: 117–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkun A. (2013) New topical hemostatic powders in endoscopy. Gastroenterol Hepatol 9: 744–746. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkun A., Moosavi S., Martel M. (2013) Topical hemostatic agents: a systematic review with particular emphasis on endoscopic application in GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 77: 692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binmoeller K., Weilert F., Shah N., Kim J. (2011) EUS-guided transesophageal treatment of gastric fundal varices with combined coiling and cyanoacrylate glue injection (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 74: 10019–10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvet X., Vergara M., Brullet E., Gisbert J., Campo R. (2004) Addition of a second endoscopic treatment following epinephrine injection improves outcome in high-risk bleeding ulcers. Gastroenterology 126: 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappell M. (2010) Therapeutic endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB): techniques of therapeutic endoscopy. Available at: http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/717727 (accessed 3 March 2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cappell M., Friedel D. (2008) Acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: endoscopic diagnosis and therapy. Med Clin North Am 92: 511–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S., Chiu P., Teoh A., Lau J. (2014) Use of the Over-The-Scope Clip for treatment of refractory upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a case series. Endoscopy 46: 428–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Barkun A., Nolan S. (2014) Hemostatic powder TC-325 in the management of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a two-year experience at a single institution. Endoscopy. DOI: 10.1055/s-0034-1378098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Barkun A., Soulellis C., Mayrand S., Ghali P. (2012) Use of the endoscopically applied hemostatic powder TC-325 in cancer-related upper GI hemorrhage: preliminary experience. Gastrointest Endosc 75: 1278–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I., Gaslightwala I., Jensen D., Cohen J. (2009) Endoclip therapy in the gastrointestinal tract: bleeding lesions and beyond. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/endoclip-therapy-in-the-gastrointestinal-tract-bleeding-lesions-and-beyond (accessed 3 March 2014).

- Chung S., Leong H., Chan A., Lau J., Yung M., Leung J., et al. (1996) Epinephrine or epinephrine plus alcohol for injection of bleeding ulcer: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 43: 591–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giorgio P., De Luca L., Calcagno G., Rivellini G., Mandato M., De Luca B., et al. (2004) Detachable snare versus epinephrine injection in the prevention of postpolypectomy bleeding: a randomized and controlled study. Endoscopy 36: 860–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Tawil A. (2012) Trends on gastrointestinal bleeding and mortality: Where are we standing? World J Gastroenterol 18: 1154–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry L., Neumann H., Olano C., Malfertheiner P., Mönkemüller K. (2008) Efficacy, complications and clinical outcomes of endoscopic sclerotherapy with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate for bleeding gastric varices. Dig Dis 26: 300–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T. (2012) Controlling gastric variceal bleeding with endoscopically applied hemostatic powder (Hemospray). J Hepatology 57: 1397–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Tsao G., Sanyal A., Grace N., Carey W. (2007) Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology 46: 922–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giday S., Kim Y., Krishnamurty D., Ducharme R., Liang D., Shin E., et al. (2011) Long-term randomized controlled trial of novel nanopowder hemostatic agent (TC-325) for control of severe arterial upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a porcine model. Endoscopy 43: 296–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giday S., Van Alstine W., Van Vleet J., Ducharme R., Brandner E., Florea M., et al. (2013) Safety analysis of a hemostatic powder in a porcine model of acute severe gastric bleeding. Dig Dis Sci 58: 3422–3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granata A., Curcio G., Azzopardi N., Barresi L., Tarantino I., Traina M. (2013) Hemostatic powder as rescue therapy in a patient with H1N1 influenza with uncontrolled colon bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 78: 451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holster I., Brullet E., Kuipers E., Campo R., Fernández-Atutxa A., Tjwa E. (2014) Hemospray treatment is effective for lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy 46: 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim M., El-Mikkawy A., Mostafa I., Deviere J. (2013) Endoscopic treatment of acute variceal hemorrhage by using hemostatic powder TC-325: a prospective pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc 78: 769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen D., Machicado G. (2005) Endoscopic hemostasis of ulcer hemorrhage with injection, thermal, and combination methods. Tech Gastrointest Endosc 7: 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen D., Machicado G. (2009) Contact thermal devices, endoscopic hemoclips, and epinephrine injection for ulcer hemorrhage. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/contact-thermal-devices-for-the-treatment-of-bleeding-peptic-ulcers (accessed 3 March 2014).

- Katsinelos P., Kountouras J., Paroutoglou G., Beltsis A., Chatzi-mavroudis G., Zavos C., et al. (2006) Endoloop-assisted polypectomy for large pedunculated colorectal polyps. Surg Endosc 20: 1257–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs T. (2008) Management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 10: 535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravetz D. (2007) Prevention of recurrent esophageal variceal hemorrhage: review and current recommendations. J Clin Gastroenterol 41(Suppl. 3): 318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubba A., Palmer K. (1996) Role of endoscopic injection therapy in the treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer. Br J Surg 83: 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc S., Vienne A., Dhooge M., Coriat R., Chaussade S., Prat F. (2013) Early experience with a novel hemostatic powder used to treat upper GI bleeding related to malignancies or after therapeutic interventions. Gastrointest Endosc 78: 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung Ki E., Lau J. (2012) New endoscopic hemostasis methods. Clin Endosc 45: 224–229. DOI: 10.5946/ce.2012.45.3.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy M., Song L. (2013) EUS-guided angiotherapy for gastric varices: coil, glue, and sticky issues. Gastrointest Endosc 78: 722–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy M., Song L., Farnell M., Misra S., Sarr M., Gostout C. (2008) Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided angiotherapy of refractory gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 103: 352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Lo W., Cheng Y., Perng C. (2007) Endoscopic hemoclip versus triclip placement in patients with high-risk peptic ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 102: 539–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Petersen B., Tierney W., Chuttani R., DiSario J., Coffie J., et al. (2008) Endoscopic banding devices. Gastrointest Endosc 68: 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchtefeld M., Senagore A., Szomstein M., Fedeson B., Van Erp J., Rupp S. (2000) Evaluation of transarterial embolization for lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Dis Colon Rectum 43: 532–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleux G., Roeflaer F., Heye S., Vandersmissen J., Vliegen A., Demedts I., et al. (2009) Long-term outcome of transcatheter embolotherapy for acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol 104: 2042–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mönkemüller K., Toshniwal J., Zabielski M., Vormbrock K., Neumann H. (2012) Utility of the “bear claw”, or over-the-scope clip (OTSC) system, to provide endoscopic hemostasis for bleeding posterior duodenal ulcers. Endoscopy 44(Suppl. 2): E412–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi S., Chen Y., Barkun A. (2013) TC-325 application leading to transient obstruction of a post-sphincterotomy biliary orifice. Endoscopy 45(Suppl. 2): E130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata S., Kimura S., Ogoshi H., Hidaka T. (2010) Endoscopic hemostasis of gastric ulcer bleeding by hemostatic forceps coagulation. Dig Endosc 22(Suppl. 1): 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganelli M., Alvarez F., Halac U. (2014) Use of Hemospray for non-variceal esophageal bleeding in an infant. J Hepatology 61: 712–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedroto I., Dinis-Ribeiro M., Ponchon T. (2012) Is timely endoscopy the answer for cost-effective management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding? Endoscopy 44: 721–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargon P., Laurie T. (2013) Hemospray for life-threatening ulcer bleeding: first case report in the United States. ACG Case Rep J 1(1): 7–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal S., Changela K., Papafragkakis H., Anand S., Krishnaiah M., Duddempudi S. (2013) Over the scope clip: technique and expanding clinical applications. J Clin Gastroenterol 47: 749–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L., Morris A., Stanley A. (2013) The use of Hemospray in portal hypertensive bleeding; a case series. J Hepatology 60: 457–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L., Stanley A., Bergman J., Kiesslich R., Hoffman A., Tjwa E., et al. (2014) Hemospray application in nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: results of the survey to evaluate the application of Hemospray in the luminal tract. J Clin Gastroenterol 48(10): e89–e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulellis C., Carpentier S., Chen Y., Fallone C., Barkun A. (2013) Lower GI hemorrhage controlled with endoscopically applied TC-325 (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 77: 504–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley A., Smith L., Morris A. (2013) Use of hemostatic powder (Hemospray) in the management of refractory gastric variceal hemorrhage. Endoscopy 45: E86–E87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulz M., Frei R., Meyenberger C., Bauerfeind P., Semadeni G., Gubler C. (2014) Routine use of Hemospray for gastrointestinal bleeding: prospective two-center experience in Switzerland. Endoscopy 46: 619–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung J., Luo D., Wu J., Ching J., Chan F, Lau J., et al. (2011) Early clinical experience of the safety and effectiveness of Hemospray in achieving hemostasis in patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Endoscopy 43: 291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weldon D., Burke S., Sun S., Mimura H., Golzarian J. (2008) Review: Interventional management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Eur Radiol 18: 857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau A., Ou G., Galorport C., Amar J., Bressler B., Donnellan F., et al. (2014) Safety and efficacy of Hemospray in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 28 (2):72–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]