Abstract

Background

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) or kala-azar is considered as a parasitic disease caused by the species of Leishmania donovani complex which is intracellular parasites. This systemic disease is endemic in some parts of provinc-es of Iran. The aim of this study was to determine the seroprevalence of VL in Qom Province, central Iran using di-rect agglutination test (DAT).

Methods

Overall, 1564 serum samples (800 males and 764 females) were collected from selected subjects by random-ized cluster sampling in 2011-2012. Sera were tested and analyzed by DAT. Before sampling; a questionnaire was filled out for each case. Data were analyzed using Chi-square test and multivariate logistic regression for risk factors analysis.

Results

Of 1564 individuals, 53 cases (3.38%) showed Leishmania specific antibodies as follows: with 1:400 titer 16 cases (1.02%), with 1:800 titer 20 cases (1.27%), with 1:1600 titer 16 cases (1.02%) whereas only one subject (0.06%) showed titers of ≥ 1:3200. There was no significant association between VL seropositivity and gender, age group and occupation. Binary logistic regression showed that rural areas was 0.44 times at higher risk of infection than urban areas (OR= 0.44; %95 CI= 0.25- 0.78).

Conclusion

Although the seroprevalence of VL is relatively low in Qom Province, yet due to the importance of the disease, the surveillance system should be monitored by health authorities.

Keywords: Visceral Leishmaniasis, Seroepidemiology, Prevalence, Direct agglutination test, Human, Iran

Introduction

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) or Dumdum fever is a vector-borne disease caused by the Leishmania infantumdonovani complex. VL is a systemic disease considered as the most devastating type of leishmaniasis, since it usually causes death in untreatedcases and many cases of deaths are left unrecognized (1). Even in cases of treatment, it may result in case-fatality rates of 10–20%. It is estimated that about 500,000 episodes and 59,000 deaths occur annually owing to this type of leishmaniasis (2). VL is the second-largest parasitic killer in the world following malaria (3).

The clinical features of VL include fever, weight loss, fatigue, mucosal ulcers, anemia, and substantial hyperplasia of the liver and spleen that these symptoms can be easily mistaken with other febrile disease (4, 5). Of particular concern, based on the World Health Organization (WHO), is the emerging problem of HIV/VL co-infection and 34 countries reporting Leishmania/HIV co-infection worldwide (6). VL is a cosmopolitan disease and distributed in the Middle East region. In addition, domestic dogs (Canisfamiliaris) are known as major reservoir hosts of VL (4).

Mediterranean VL is considered endemic in some areas of Iran including Ardabil (Moghan and Meshkin shahr), eastern Azerbaijan (Ahar and Kalibar), Bushehr (Dashti and Dashtestan) Fars (Darab, Firouzabad Noor abad and Jahrom), northern Khorasanand Qom (Khaljestan) districts. It has been reported sporadically in other provinces of the country (7-12).

The aim of this study was to determine the seroprevalence and risk factors association of VL in Qom Province, central Iran using direct agglutination test (DAT).

Materials and Methods

Study area

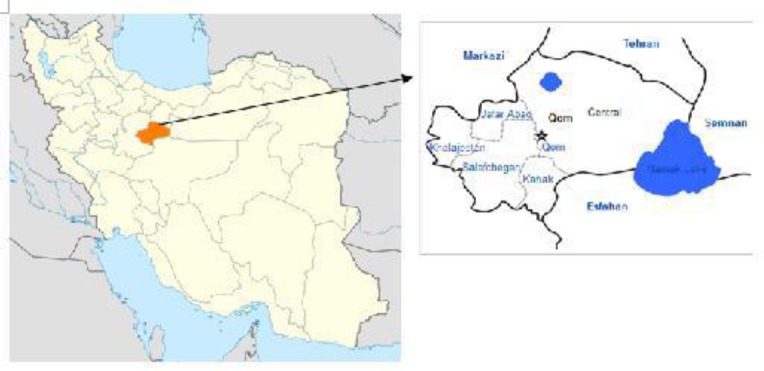

Qom Province located on the south of Tehran and central Iran is of 11238 sq. km. The province is connected to the Semnan Province in the east, to the Isfahan Province in the south and to the Markazi Province from south-west to north-west (Fig.1). The population is estimated as one million. The province comprises of 1 city, 5 towns, 4 districts, and 936 habitationsout of which 356 are populated (Source: http://amar.sci.org.ir/index_e.aspx).

Fig. 1.

Geographical locations of Qom Province in Iran where our serum samples were collected.

Blood sampling

A cross-sectional study was performed on urban and rural populations of Qom Province in 2011-2012. Household data were obtained from local health authorities and one random person of one family out of twenty seven families was selected. Totally, 1564 serum samples (800 males and 764 females) were collected from 700 urban and 864 rural areas by randomized cluster sampling (Table 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Study areas and number of collected serum for detection of seroprevalence of human visceral Leishmania infection in Qom Province

| Area | No. of sera |

|---|---|

| Urban | 700 |

| Kahak | 264 |

| Ghamrod&Ghanavat | 163 |

| Ghaleecham&Salafcheghan | 154 |

| Ghahan&Dastjerd | 151 |

| Jaafarieh | 150 |

| Total | 1564 |

Table 2.

Distribution of studied population for detection of seroprevalence of human visceral Leishmania infantum infection by gender, residual area, occupation, dog keeping and education in Qom Province, central Iran

| Sex | Location | Occupation | Dog keeping | Education | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | female | Urban | Rural | Farmer | Householder | Schooling | Other | Yes | No | Educated | Illiterate | |

| 800 | 764 | 700 | 864 | 201 | 571 | 166 | 628 | 184 | 1380 | 865 | 699 | 1564 |

An informed consent document was taken from every participant. A questionnaire was filled out for each individual to obtain information then the blood sample was taken from each participant and transferred to sera separated the laboratory of the Amiralmomenin Polyclinic, Qom, Iran.

Sera were sent to Leishmaniasis Laboratory, Dept. of Medical Parasitology, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran for examination with DAT.

Direct agglutination test (DAT)

DAT antigen was made in the Protozoalogy Unit of the School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The principal phases of the procedure for preparing DAT antigen were mass production of promastigotes of Leishmania infantum(MCAN/IR/07/Moheb-gh.), (GenBank accession (no. FJ555210) (Iranian strain) in RPMI1640 plus 10% fetal bovine serum, tripsinization of the parasites, fixing with formaldehyde 2% and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. The human sera were tested by DAT, initially, for screening purposes; dilutions were made at 1:400 and 1:3200 for human's samples.

Negative control wells (antigen only) and known negative and positive controls were tested in each plate daily. The positive standard control serum was prepared from VL patients with L. infantum infection from the endemic areas. The cut off titer was determined as 1:3200, specific Leishmania antibodies at a titer of 1:3200 and upper were considered as positive (13, 14).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 16 program. Odds ratios for risk factors analysis were calculated by multivariate logistic regression model. P< 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Of 1564 individuals, 53 cases (3.38%) showed Leishmania specific antibodies as follows: with 1:400 titer 16 cases (1.02%), with 1:800 titer 20 cases (1.27%), with 1:1600 titer 16 cases (1.02%) whereas only one subject (0.06%) showed titers of ≥ 1:3200 (Table 3 and 4). Therefore considering the cut off titer, only one sample was regarded as positive case which belongs to a 30 years- old educated man who resides in Kahak and with no history of keeping dog.

Table 3.

Frequencyof anti-Leishmania antibodies titers using DAT by residual area in Qom Province, central Iran

| Residual area | 1:400 | (%) | 1:800 | (%) | 1:1600 | (%) | 1:3200 | (%) | Total | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | 4 | 0.25 | 15 | 0.96 | 15 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 2.17 |

| Rural | 12 | 0.77 | 5 | 0.31 | 1 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.06 | 19 | 1.21 |

| Total | 16 | 1.02 | 20 | 1.28 | 16 | 1.02 | 1 | 0.06 | 53 | 3.38 |

Table 4.

Seroprevalence of human visceral Leishmania infection by direct agglutination test (DAT ≥ 1:3200) with anti-Leishmania infantum antibodies by gender in Qom Province

| Gender | No. examined | Anti-Leishmania antibody titers | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:400 | 1:800 | 1:1600 | ≥1:3200 | |||||

| No.Prevalence (%) | No.Prevalence (%) | No.Prevalence (%) | No.Prevalence (%) | No.Prevalence (%) | ||||

| Male | 800 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 33 | ||

| 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.06 | 2.1 | ||||

| Female | 764 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 20 | |

| 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 1.27 | |||||

| Total | 1564 | 16 | 20 | 16 | 1 | 53 | ||

| 1.01 | 1.28 | 1.01 | 0.06 | 3.38 | ||||

Furthermore, in urban areas 34 subjects (2.17%) showed a titers of ≥ 1:400 while in rural areas were 18 cases including Kahak one sample (0.4%), Ghahan&Dastjerd 11 samples (7.3%), Ghamrod&Ghanavat 5 samples (3.1%) and Jaafarieh one sample (0.7%). There was no significant association between VL seropositivity and gender, age group and occupation. Binary logistic regression showed that rural areas was 0.44 times at higher risk of infection than urban areas (OR= 0.44; %95 CI= 0.25- 0.78).

Discussion

In the current study from 1564 collected human serum samples, 1 sample showed anti-Leishmania antibodies at titers of ≥ 1:3200 whereas 52 samples (3.3%) revealed anti-Leishmania infantum antibodies at titers of ≥ 1:400. Meanwhile, 16 (2.1%) subjects revealed titer of 1:1600 which is considered as suspicious cases. In this study, males showed more anti-Leishmania specific antibodies compared to females that is in consistent with other studies (15, 16).

This survey showed that one case in rural areas had anti-Leishmania antibodies at titer 1:3200 in comparison with urban areas (0 case) (P= 0.007). Besides, rural areas was 0.44 times at higher risk to be infected than urban areas (OR= 0.44; %95 CI= 0.25- 0.78) and multivariate analysis showed that rural areas was 0.45 times at higher risk of infection than urban areas (OR= 0.45; %95 CI=0.23-0.89). This fact may be associated hygienic level in rural areas. There was no significant association between VL seropositivity, sex and age group.

According to literature review the seroprevalence of VL using DAT at titers ≥ 1:3200 in other parts of the Iran was as follows: Mazandaran Province 0.% (17), Kermanshah Province0.33% (18), Khorasan Province [Bojnurd and Shirvan, 0.46%] (13),Kerman Province [Baft 0.95%] (19), ChaharMahal&Bakhtiari province [Poshtkuh 1.3%] (20), Kohgiloyeh&Bouirahmad Province 3.1% (21), Bushehr Province [Dashti and Dashtestan 3.4%] (10), Ardabil Province [Germi 2.8%, Meshkinshahr 6.3%, Pars- Abad and Khalkhal 5.1%] (7).

In addition, a similar investigation was carried out on 416 human sera samples in 8 villages of Ghahan, Qom Province using DAT for detection of Leishmania antibodies. Totally, 7 cases (1.7%) were positive with titers 1:3200 and above that three of seropositive cases had a previous history of VL (12). Our findings indicated that the rate of seropositivity in Qom Province is fewer than all above mentioned areas except Mazandaran Province.

In the present study, DAT was employed to detect Leishmania antibodies for a couple of reasons. Two main features of serological methods, being highly sensitive and non-invasive, make them appropriate for use in field conditions (13). The various serological methods including ELISA, DAT and IFAT (indirect fluorescent antibody test) are available for diagnosis of VL. Due to simplicity, validity, economical benefits, high sensitivity and specificity, DAT was used in several epidemiologic studies in Iran with large-scale screening of human. The sensitivity and specificity of this assay at cut-off titer 1:3200 varies between 90–100% and 72–100% respectively (22, 23).

Conclusion

The present study showed that the risk of VL is still remained in this region. To control VL in this area, further investigation on sand flies fauna and canines as reservoir hosts of VL are highly recommended, and also treatment of suspected human cases should be considered. Continuous serological researches and preventive measures should be taken into consideration owing to the significance of the disease.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. We wish to thank the laboratory staff Cordial collaboration of MrsCharedarand Dr. MMohammadian, Vice-chancellor of Health,Qom Province, MrsFatemehAbedi, for their sincerecooperation. The authors declare that there isno conflict of interests.

References

- Larry SR, Janovy J (2006). Foundations of parasitology. 7thed McmGraw. Hill companies, New York, pp: 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2010). First WHO report on neglected tropical diseases: working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases WHO/HTM/NTD/2010.1, PP:91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Desjeux P (2001). The increase in risk factors for leishmaniasis worldwide. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 95: 239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edrissian GhH, Nadim A, Alborzi AV, Ardehali S (1998). Visceral leishmaniasis; Iranian experience. Arch Irn Med, 1:22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Collin S, Davidson R, Ritmeijer K, Keus K, Melaku Y (2004). Conflict and kala-azar: determinants of adverse outcomes of kala-azar among patients in southern Sudan. Clin Infect Dis, 38: 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvar J, Aparicio P, Aseffa A, Den Boer M, Cañavate C, Dedet JPet al. (2008). The relationship between leishmaniasis and AIDS: the second 10 years. ClinMicrobiol Rev, 21:334–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohebali M, Edrissian GhH, Shirzadi MR, Akhoundi B, Hajjaran H, Zarei Zet al. (2011). An observational study on the current distribution of visceral leishmaniasis in different geographical zones of Iran and implication to health policy. Travel Med InfectDis, 9: 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edrissian GhH, Ahanchin AR, Gharachahi AM (1993). Seroepidemiological studies of visceral leishmaniasis and search for animal reservoirs in Fars province, southern Iran . Iranian JMedSci, 18: 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimanzadeh G, Edrissian GhH, Movahhed- Danesh AM, Nadim A (1993). Epidemiological aspects of kala-azar in Meshkin-Shahr, Iran: human infection. Bull World Health Organ 71(6): 759–762. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohebali M, Hamzavi Y, Edrissian GhH, Foruzani AR (2001). Seroepidemiological study of Visceral Leishmaniasis among humans and animal reservoirs in Bushehr province, Iran. East Meditrr Health J 7(6): 912–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhar M, Motazedian MH, Askari K (2006). A new endemic focus of visceral leishmaniasis in the south of Iran. ArmaghanDanesh 11(2):104–110 [in Persian]. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhar M, Mohebali M, Barani M (2004). Identification of endemic focus of Kala-azar and seroepidemiological study of visceral leishmaniasis infection in human and canine in Qom province, Iran. ArmaghanDanesh 9(33): 51–59 [in Persian]. [Google Scholar]

- Mohebali M, Edrissian GH, Nadim A, Hajjaran H (2006). Application of Direct Agglutination Test (DAT) for the diagnosis and seroepidemiological studies of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Iran. Iranian J Parasitol, 1(1) :15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Edrissian GhH, Hajjaran H, Mohebali M, Soleimanzadeh G, Bokaei S (1996). Application and evaluation of direct agglutination test in sero-diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in man and canine reservoirs in Iran. Iranian J Med Sci, 21: 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava P, Dayama A, Mehrotra S, Sundar S (2011). Diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. Trans Royal Society Trop Med Hyg, 105: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadiha A, Mohebali M, HaghighiA, MahdianR (2013). Comparison of real-time PCR and conventional PCR with two DNA targets for detection of Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum infection in human and dog blood samples. Experiment Parasitol, 133: 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhar M, Rahmati B, Gohardehi S, Mohebali M ,Akhoundi B, MSharif, et al. (2011). Molecular and Seroepidemiological Survey of Visceral Leishmaniasis among Humans and Domestic Dogs in Mazandaran Province, North of Iran. Iranian J Parasitol, 6 (4): 51–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- K Ghadiri, H Bashiri, M Pajhouhan (2012). Human Visceral Leishmaniasis in Kermanshah Province, Western Iran, During 2011–2012. Iranian J Parasitol 7(4) : 49–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudvand H, Mohebali M, Sharifi I, Keshavarz H (2011). Epidemiological Aspects of Visceral Leishmaniasis in BaftDistrict,Kerman Province, Southeast of Iran . Iranian J Parasitol 6(1): 1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GhorbanaliShahabi (1999). Kala-Azar in Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari province and infected fox as a probable wild reservoir. J ShahrekordUniv Med Sci, 1(1): 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkari B, Pedram N, Mohebali M, Moshfe AA, Zargar MA, Akhoundi B, et al. (2010). Seroepidemiological study of visceral leishmaniasis in Booyerahmad district, southwest Iran. East Mediterr Health J 16(11): 1133–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohebali M, Edrissian GHH, Nadim A, Hajjaran H, Akhoundi B, Hooshmandet al. (2006). Application of direct agglutination test (DAT) for the diagnosis and seroepidemiological studies of visceral leishmaniasis in Iran. Iranian J Parasitol, 1: 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S, Rai M (2002). Laboratory diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. ClinDiag Lab Immunol, 9: 951–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]