Abstract

Although peripheral immune system abnormalities have been linked to schizophrenia pathophysiology, standard antipsychotic drugs show limited immunological effects. Thus, more effective treatment approaches are required. Probiotics are microorganisms that modulate the immune response of the host and, therefore, may be beneficial to schizophrenia patients. The aim of this study was to examine the possible immunomodulatory effects of probiotic supplementation in chronic schizophrenia patients. The concentrations of 47 immune-related serum proteins were measured using multiplexed immunoassays in samples collected from patients before and after 14 weeks of adjuvant treatment with probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis strain Bb12; n = 31) or placebo (n = 27). Probiotic add-on treatment significantly reduced levels of von Willebrand factor (vWF) and increased levels of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), RANTES, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta (MIP-1) beta with borderline significance (P ≤ 0.08). In silico pathway analysis revealed that probiotic-induced alterations are related to regulation of immune and intestinal epithelial cells through the IL-17 family of cytokines. We hypothesize that supplementation of probiotics to schizophrenia patients may improve control of gastrointestinal leakage.

Keywords: schizophrenia, probiotic, add-on treatment, von Willebrand factor

Introduction

Abnormal immune responses have been found in many individuals with schizophrenia, regardless of disease stage or medication status.1 This is also linked to the hypothesis that schizophrenia can originate from early exposure to microbial infections, which may contribute to the etiology through chronic neuroinflammatory and autoimmune processes.2,3 However, current antipsychotic medications show limited immunomodulatory effects.4 Recent clinical trials have attempted to target schizophrenia-related immune activation using anti-inflammatory agents. Supplementation with celecoxib, acetylsalicylic acid, and minocycline in addition to standard antipsychotic medication has resulted in overall patient improvement, in particular in a reduction in positive psychotic symptoms.5–7 However, the number of the immunomodulatory compounds tested to improve symptoms in schizophrenia is small, and further studies are required in this field.

Probiotics are beneficial microorganisms that modulate the immune response of the host by affecting the composition of gut microbiota.8 Several probiotic species have been tested for health benefits, including the gram-positive anaerobic genres Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. These have shown beneficial effects on systemic inflammatory cytokine levels,9 neurotransmitter and neurotrophic factor production,10 intestinal permeability,11 and oxidative stress in animal models.12 In humans, oral administration of probiotics is known to restore normal inflammatory status,13 increase systemic antioxidant capacity,14 change the activity of brain regions responsible for processing of emotion and sensation,15 and reduce anxiety.16 Improved brain function after probiotic supplementation has been attributed to the gut–brain axis, ie, multiple ways of communication between bacteria inhabiting the human intestine and the central nervous system.17,18 For example, probiotic microorganisms interact with the innate immune system, affecting secretion of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines which, in turn, can regulate brain development and function.19 In addition, bacteria of the species Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are capable of producing neurotransmitters such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and acetylcholine, which directly target receptors in the central nervous system.20 Therefore, probiotics have been suggested as a potential novel therapeutic approach for a range of neurodevelopmental disorders.21

We recently carried out a clinical trial to assess whether supplementation of probiotic strains Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 can reduce symptom severity in schizophrenia patients remaining on long-term antipsychotic treatment.22 The present follow-up study was undertaken to examine the systemic immunomodulatory effects of probiotic supplementation in the same patient population. Using multiplexed immunoassays, we measured the levels of 47 immune molecules in patient sera collected before and after treatment with adjunctive probiotics or placebo. Group comparisons revealed probiotic-specific changes in levels of molecules involved in innate and adaptive immune responses and intestinal epithelial cell function. These alterations may be related to improved function of the intestinal tract in the probiotic arm of the trial reported before.22

Materials and Methods

Participants and study procedures

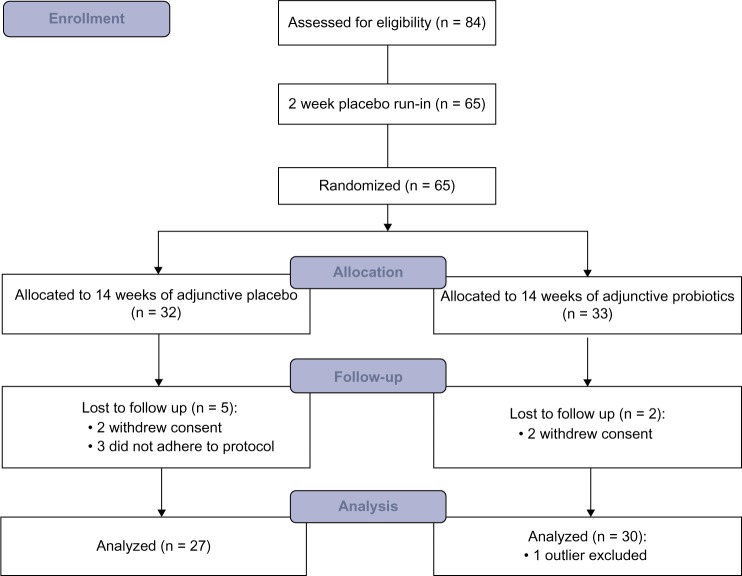

The patient population and probiotic compound investigated in this study have been described in detail previously.22 Briefly, 65 outpatients from psychiatric rehabilitation programs in the Baltimore area (MD, USA) diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to DSM-IV criteria, with at least moderately severe psychotic symptoms [Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) positive score ≥1, PANSS negative symptom score ≥4, or total PANSS score ≥50, containing at least three positive or negative items with scores ≥3 at screening] were enrolled in the study between December 2010 and August 2012. Participants were randomized into a double-blind 14-week treatment protocol with adjunctive probiotic (n = 33) or placebo (n = 32), with initial 2-week placebo run-in (Fig. 1). All patients received antipsychotic treatment for at least eight weeks prior to starting the trial and did not change the medication within the previous 21 days. Patients suffering from any clinically significant or unstable medical condition, including congestive heart failure, celiac disease, or immunodeficiency syndromes, as well as those receiving antibiotics within the previous 14 days were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow diagram of the trial.

The active study compound consisted of one tablet containing approximately 109 colony forming units of the probiotic organism L. rhamnosus GG and 109 colony forming units of the probiotic organism Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB12 (Ferrosan) or placebo. The probiotic microorganisms were grown in media that do not contain casein, lactose, other milk products, or gluten, to reduce the risk of allergic reactions to these ingredients.

In total, 58 participants completed the trial, comprising 31 in the probiotic arm and 27 in the placebo arm. Blood samples were collected from all subjects at the beginning and at the end of the trial. Serum was prepared by allowing clot formation for two hours at room temperature and subsequent centrifugation at 4000g for five minutes. The resulting serum supernatants were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Multiplexed immunoassays

Serum samples were analyzed using the Human InflammationMAP panel in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory (Myriad RBM). The panel consisted of 47 multiplexed immunoassays targeting selected inflammatory markers, including cytokines, chemokines, and acute-phase reactants (Table 1A). Analyte levels were estimated in each sample from the 8-point standard curves, and assay performance was validated using three control samples. The same multiplex immunoassay platform has been applied successfully for serum bio-marker profiling in a range of high-impact studies.23–25

Data analysis

For those participants who completed the double-blind phase, immune marker data acquired from multiplex immunoassay analyses were filtered separately for each treatment group and time point. Principal component analysis was applied to identify artifactual effects on the overall variance. One extreme outlier was detected outside of the Hotelling’s T2 ellipse showing 95% confidence intervals26 in the probiotic-supplemented group and was removed from the analysis. Molecules with more than 60% low values were excluded from further analysis to allow a minimum of 10 measurements per comparison group. This equated to 20 analytes (Table 1A). For the 27 analytes remaining in the dataset, missing values were replaced with half the minimum value for that specific assay. Shapiro–Wilk tests showed that the majority of analyte levels were non-normally distributed and a large proportion (30%) remained non-normally distributed after log10-transformation. Therefore, a non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied to compare analyte levels before and after treatment. Resulting P-values were controlled for false discovery rate with a conservative Benjamini–Hochberg approach.27

Pathway analysis was performed using the ingenuity pathways knowledge database (IPKB; Ingenuity® Systems). Only molecules from the datasets that met the P-value cutoff of 0.10 and were associated with the biological functions and/or canonical pathways in the IPKB were considered for the analysis. A right-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate P-values associated with the identified pathways. The significance of the association between the dataset and canonical pathways was measured by the ratio between the number of molecules from the dataset divided by the total number of known molecules in that pathway and by the P-value (Fisher’s exact test).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board of the Sheppard Pratt Health System and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov corresponding to NCT01242371 and monitored by a data safety monitoring board. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The research complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

A total of 65 patients were enrolled in the study and randomized, 33 to the adjunctive probiotics arm and 32 to the adjunctive placebo arm. A total of 58 participants (89%) completed the study (Fig. 1). The clinical characteristics of the completers are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, gender, race, duration of education, PANSS scores, and proportion of patients receiving clozapine between the groups at the beginning of the study.22 PANSS psychiatric symptom scores did not change over the course of the trial, but patients receiving probiotic supplement were less likely to report severe bowel difficulties (P = 0.003).22

Table 1.

Demographical and clinical data of study completers. The table shows mean values ± standard deviation. Detailed description of this patient population can be found in Ref. 22.

| PROBIOTIC SUPPLEMENT | PLACEBO SUPPLEMENT | P-VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 31 | 27 | – |

| Age | 44.8 ± 11.2 | 48.1 ± 9.4 | 0.236a) |

| Gender (male/female) | 22/9 | 16/11 | 0.413b) |

| Race (white/other) | 16/15 | 20/7 | 0.106b) |

| PANSSc) total start | 67.3 ± 11.9 | 70.2 ± 11.6 | 0.258a) |

| PANSSc) total end | 66.8 ± 11.6 | 67.3 ± 11.9 | 0.773a) |

| CRPd) start (μg/ml) | 6.7 ± 8.2e) | 6.3 ± 7.6 | 0.829a) |

| CRPd) end (μg/ml) | 7.1 ± 7. 9 | 7.3 ± 10.1e) | 0.841a) |

Notes:

Mann–Whitney U test.

Fisher’s exact test.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

C-reactive protein.

One outlier excluded.

In terms of the mechanism of action, treatment with probiotics significantly decreased the levels of the acute-phase reactant von Willebrand factor (vWF; Table 2). Uploading the accession numbers of all analytes, which showed a change at a significance level of <0.10 [vWF, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), T-cell-specific protein RANTES, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta (MIP-1 beta)] into the IPKB (www.ingenuity.com), indicated that supplementation with probiotics most significantly affected the regulation of cytokine production in macrophages, T helper cells and intestinal epithelial cells by IL-17A and IL-17F pathways (top canonical pathways, P = 9.34E – 06 and 1.54E – 05, ratio 0.111 and 0.087; Table 3). Missing values for the proteins included in pathway analysis ranged between 0 and 31%.

Table 2.

Changes in immune marker levels following probiotic and placebo supplementation with P-value <0.10. The table shows mean values before and after treatment ± standard deviation. The full list of changes is available in Table 2A.

| ANALYTE | UNIPROTKD ID | UNITS | PROBIOTIC SUPPLEMENT | PLACEBO SUPPLEMENT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEFORE | AFTER | P-VALUE | Q-VALUEa) | BEFORE | AFTER | P-VALUE | Q-VALUEa) | |||

| von Willebrand Factor | P04275 | μg/ml | 30.5 ±21.0 | 25.5± 18.4 | 0.047 | 0.431 | ||||

| Monocyte Chemotactic Protein 1 | P13500 | pg/ml | 184.9 ±125.7 | 226.1 ±135.5 | 0.054 | 0.431 | ||||

| Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor | P23560 | ng/ml | 3.2 ±1.5 | 4.1 ±2.6 | 0.063 | 0.431 | ||||

| T Cell Specific Protein RANTES | P13501 | ng/ml | 5.7 ±2.6 | 7.3 ±4.7 | 0.069 | 0.431 | ||||

| Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 1 beta | P13236 | pg/ml | 185.9 ± 110.9 | 205.0 ±109.9 | 0.080 | 0.431 | ||||

| Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 | P19320 | ng/ml | 505.0 ±160.8 | 442.1 ±134.4 | 0.016 | 0.313 | ||||

| Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 | P05362 | ng/ml | 200.1 ±108.4 | 166.9 ±66.6 | 0.023 | 0.313 | ||||

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 | P20333 | ng/ml | 5.8 ±2.9 | 5.0±1.9 | 0.072 | 0.450 | ||||

| Ferritin | P02794 P02792 | ng/ml | 142.1 ±106.2 | 121.3±85.7 | 0.073 | 0.450 | ||||

| Matrix Metalloproteinase 3 | P08254 | ng/ml | 19.0±12.9 | 16.8 ± 11.0 | 0.099 | 0.450 | ||||

Note:

q-value – P-value controlled for false discovery rate with Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

Table 3.

A list of canonical pathways most significant to the probiotic and placebo groups revealed by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Only proteins that met the P-value cut-off of 0.10 were considered for the analysis. Significance of the association was measured by P-value and by the ratio of the involved molecules. Probiotic supplementation showed enrichment in IL-17A- and IL-17F-related pathways.

| PROBIOTIC SUPPLEMENT | PLACEBO SUPPLEMENT |

|---|---|

| Differential Regulation of Cytokine Production in Macrophages and T Helper Cells by IL-17A and IL-17F (P = 9.34E-06, ratio = 1.11E-01) | Atherosclerosis Signaling (P = 2.54E-08, ratio = 3.1E-02) |

| Differential Regulation of Cytokine Production in Intestinal Epithelial Cells by IL-17A and IL-17F (P = 1.54E-05, ratio = 8.7E-02) | Leukocyte Extravasation Signaling (P = 2.37E-05, ratio = 1.6E-02) |

| Role of Hypercytokinemia/hyperchemokinemia in the Pathogenesis of Influenza (P = 4.99E-05, ratio = 4.9E-02) | Role of Macrophages, Fibroblasts and Endothelial Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis (P = 8.33E-05, ratio = 1.0E-02) |

| Role of IL-17 A in Arthritis (P = 8.7E-05, ratio = 3.3E-02) | HMGB1 Signaling (P = 4.3E-04, ratio = 2.1E-02) |

| Role of MAPK Signaling in the Pathogenesis of Influenza (P = 1.3e-04, ratio = 3.0e-02) | Hepatic Fibrosis/Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation (P = 9.31e-04, ratio = 1.4e-02) |

Changes identified in the placebo group [vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1); Table 2] may have resulted from abnormally high levels of these proteins at baseline and therefore cannot be assigned as true placebo effects. Initial levels of VCAM-1 in the placebo group were 21% higher than in the group supplemented with probiotics (P = 0.021, Mann–Whitney test). After treatment, VCAM-1 returned to similar levels (3% difference, P = 0.581), with the greatest change observed for patients with the highest initial VCAM-1 levels (Spearman’s rho = −0.61, P = 0.0007). This suggests that changes in the placebo group may be because of the regression to the mean effect.28,29 In contrast, the levels of vWF at the end of the trial were 11% lower in the probiotic arm, suggesting a true change in vWF levels by probiotics.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the immunomodulatory effects of probiotic supplementation in schizophrenia. In this investigation, 65 patients undergoing long-term antipsychotic treatment were randomized to 14 weeks of either probiotic or placebo add-on supplementation and 58 participants completed the trial (Fig. 1). Using multiplexed immunoassays, we measured levels of 47 immune markers before and after add-on treatment, of which 27 satisfied the strict criteria for analysis. We found that probiotic supplementation significantly reduced levels of vWF, and levels of MCP-1, BDNF, T-cell-specific protein RANTES, and MIP-1 beta were found to be increased with borderline significance (P ≤ 0.08). These changes were related mostly to the regulation of cytokine production in macrophages, T helper cells, and intestinal epithelial cells as shown by the effects on IL-17A and IL-17F pathways. Although IL-17 levels were not detectable in our study, we identified a trend toward increased levels of other cytokines related to IL-17, namely MCP-1 and RANTES. The decreased levels of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in the placebo group were interpreted as regression to the mean effect,28,29 ie, they resulted from abnormally high initial levels in the placebo group and did not differ between the groups at the end of the study. This is consistent with the fact that the placebo was provided in the context of long-term stable antipsychotic treatment, and therefore, no changes were expected in this group.

The only molecule that changed when applying conventional significance criteria (P < 0.05) after probiotic supplementation was vWF (FC = 0.84). vWF is a positive acute-phase reactant produced by endothelial cells in response to injury and plays an important role in blood coagulation. This protein has been found to be positively correlated with cardiovascular risk factors in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and does not change with second-generation antipsychotic treatment.30 In our study, probiotic supplementation decreased the levels of vWF. Probiotics are known to decrease levels of certain cardiovascular risk parameters.31 However, their effect on cardiovascular risk and antipsychotic-related thromboembolism32 should be assessed in future longitudinal studies by measuring more specific cardiovascular and coagulation markers, such as D-dimer, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL).

Pathway analysis suggested that probiotic add-on treatment, but not standard antipsychotic therapy, modulates immune function via type 17 immune responses. This pathway involves the IL-17 family of cytokines, which are regulatory proteins produced by T helper 17 (Th17) cells involved in cellular responses to extracellular bacteria such as those colonizing the intestinal lumen.33 Therefore, we hypothesize that the observed cytokine changes are related to improved bowel functioning, which we reported in this group of patients previously.22 These cytokines are also critical mediators of autoimmune reactions. Deregulation of the type 17 response has been observed in schizophrenia. Studies have shown that this pathway was blunted in psychotic episodes.34 Also, autoimmune processes against central nervous tissue components, which are regulated by type 17 cytokines, are a known phenomenon that may contribute to schizophrenia etiology and/or pathology.35 Here, we showed that molecules associated with the type 17 response, in particular MCP-1 and RANTES, increased with borderline significance in the group of patients treated with probiotic supplement. Pathway analysis suggested that these changes may be associated with improved control of gastrointestinal leakage mediated through the innate and adaptive immune systems. This is consistent with the observed decrease in vWF levels after probiotic supplementation, which might be a secondary effect of improved intestinal epithelium integrity. IL-17 levels were not detectable in any of the samples (<5 pg/mL). Therefore, further studies using assays with improved sensitivity are necessary to identify any direct effects on T helper type 17 pathways.

The finding that BDNF was increased with borderline significance by probiotic add-on treatment is interesting as it is a neurotrophin involved in neuronal survival and plasticity and has been associated previously with schizophrenia pathophysiology.36 However, an increase in BDNF levels did not translate into improved symptoms in the probiotic arm and requires further validation to show statistical significance.

Several limitations of the molecular profiling results should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, we were not able to detect all targeted cytokines in our clinical samples. This included molecules that have previously been shown to be altered in schizophrenia and modulated by probiotics, such as IL-1 beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha, and IFN-gamma. Owing to relatively high P- and q-values (q = 0.431 for P < 0.1 in the probiotic arm), the identified changes require further validation studies. Repeating these experiments using more sensitive and diverse multiplex immunoassays is essential to provide a more complete picture of the effects. Second, although we investigated only patients who remained on stable, long-term antipsychotic treatment during the trial period, it is still possible that the antipsychotic compound exhibited certain immunomodulatory effects. This relates in particular to the changes identified in VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 levels in the placebo group. Furthermore, because of the lack of a control group, it was not possible to determine whether baseline levels of the analytes were altered. In addition, the small number of analytes identified as significantly or borderline different between the two groups was a limiting factor for the pathway analysis, and more complex immune networks may be affected by probiotic supplementation. For example, although pathway analysis revealed that probiotic supplementation may affect the function of intestinal cells, further studies with more specific markers are required to assess whether probiotics can attenuate gastrointestinal inflammation.

We conclude that probiotics have immunomodulatory effects in schizophrenia patients, affecting molecules that do not respond to standard antipsychotic therapy. These changes may be associated with the improvement in bowel functioning reported previously in the same group of patients through IL-17-related immune responses, which control the intestinal microbiome–host interaction. However, supplementation of probiotics does not reduce psychotic symptoms. We suggest that future studies should be carried out that test the exact biological and neurobiological mechanisms of probiotic supplementation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Paul Guest and Dr. Hassan Rahmoune for helpful suggestions and review of the manuscript.

Appendix

Table 1A.

Inflammatory markers measured using Human InflammationMAP multiplexed immunoassay platform. Analytes excluded from the analysis because of high proportion of missing values are shown in gray.

| PROTEIN | UNIPROTKB ID | PROTEIN | UNIPROTKB ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-1-Antitrypsin (AAT) | P01009 | Interleukin-10 (IL-10) | P22301 |

| Alpha-2-Macroglobulin (A2Macro) | P01023 | Interleukin-12 Subunit p40 (IL-12p40) | P29460 |

| Beta-2-Microglobulin (B2M) | P61769 | Interleukin-12 Subunit p70 (IL-12p70) | P29459 |

| Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) | P23560 | Interleukin-15 (IL-15) | P40933 |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | P02741 | Interleukin-17 (IL-17) | Q16552 |

| Complement C3 (C3) | P01024 | Interleukin-18 (IL-18) | Q14116 |

| Eotaxin-1 | P51671 | Interleukin-23 (IL-23) | Q9nPF7 |

| Factor VII | P08709 | Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1 alpha (miP-1 alpha) | P10147 |

| Ferritin (FRTN) | P02794, P02792 | Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1 beta (MIP-1 beta) | P13236 |

| Fibrinogen | P02671, P02675, P02679 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) | P08253 |

| Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) | P04141 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3) | P08254 |

| Haptoglobin | P00738 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) | P14780 |

| Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1) | P05362 | Monocyte Chemotactic Protein 1 (MCP-1) | P13500 |

| Interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) | P01579 | Stem Cell Factor (SCF) | P21583 |

| Interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1 alpha) | P01583 | T-Cell-Specific Protein RANTES (RANTES) | P13501 |

| Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta) | P01584 | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1) | P01033 |

| Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) | P18510 | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-alpha) | P01375 |

| Interleukin-2 (IL-2) | P60568 | Tumor Necrosis Factor beta (TNF-beta) | P01374 |

| Interleukin-3 (IL-3) | P08700 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) | P20333 |

| Interleukin-4 (IL-4) | P 0 5112 | Vascular Cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) | P19320 |

| Interleukin-5 (IL-5) | P 0 5113 | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | P15692 |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | P05231 | Vitamin D-Binding Protein (VDBP) | P02774 |

| Interleukin-7 (IL-7) | P13232 | von Willebrand Factor (vWF) | P04275 |

| Interleukin-8 (IL-8) | P10145 |

Table 2A.

Changes in immune marker levels following probiotic and placebo supplementation. FC – average fold change; P-value <0.05 was considered significant (in bold); q-value – P-value controlled for false discovery rate with Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

| ANALYTE | FUNCTIONa) | PROBIOTIC SUPPLEMENT | PLACEBO SUPPLEMENT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | P VALUE | q-VALUE | FC | P-VALUE | q-VALUE | ||||

| von Willebrand Factor | AP | ↓ | 0.84 | 0.047 | 0.431 | ↑ | 1.15 | 0.751 | 0.881 |

| Monocyte Chemotactic Protein 1 | C | ↑ | 1.22 | 0.054 | 0.431 | ↓ | 0.93 | 0.525 | 0.782 |

| Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor | GF | ↑ | 1.28 | 0.063 | 0.431 | ↑ | 1.06 | 0.895 | 0.966 |

| T Cell Specific Protein RANTES | C | ↑ | 1.28 | 0.069 | 0.431 | ↓ | 0.96 | 0.5 51 | 0.782 |

| Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 1 beta | C | ↑ | 1.1 | 0.080 | 0.431 | ↓ | 0.97 | 0.62 | 0.821 |

| Factor Vii | O | ↑ | 1.05 | 0.221 | 0.759 | ↓ | 0.92 | 0.117 | 0.450 |

| Ferritin | AP | ↓ | 0.91 | 0.225 | 0.759 | ↓ | 0.85 | 0.073 | 0.450 |

| Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor | GF | ↑ | 1.08 | 0.225 | 0.759 | ↑ | 1.01 | 0.957 | 0.994 |

| Stem Cell Factor | GF | ↑ | 1.06 | 0.285 | 0.855 | ↓ | 0.91 | 0.243 | 0. 513 |

| Haptoglobin | AP | ↓ | 0.93 | 0.365 | 0.876 | ↑ | 1.04 | 0.4 | 0.720 |

| Fibrinogen | AP | ↓ | 0.95 | 0.375 | 0.876 | ↑ | 1.02 | 0. 511 | 0.782 |

| Complement C3 | AP | ↓ | 0.96 | 0.421 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.93 | 0.247 | 0. 513 |

| Interleukin 8 | C | ↓ | 0.95 | 0.449 | 0.876 | ↑ | 1.03 | 0.713 | 0.875 |

| Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist | C | ↑ | 1.04 | 0.559 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.83 | 0.10 4 | 0.450 |

| Alpha 2 Macroglobulin | AP | ↑ | 1.02 | 0.581 | 0.876 | ↑ | 1.02 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 | O | ↑ | 1.02 | 0.584 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.88 | 0.016 | 0.313 |

| Beta 2 Microglobulin | TR | ↓ | 0.99 | 0.589 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.93 | 0.13 9 | 0.461 |

| Alpha 1 Antitrypsin | AP | ↑ | 1.03 | 0.613 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.98 | 0.638 | 0.821 |

| Interleukin 18 | C | ↑ | 1.03 | 0.65 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.9 | 0.343 | 0.661 |

| Vitamin D Binding Protein | O | ↑ | 1.02 | 0.713 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.95 | 0.234 | 0. 513 |

| Interleukin 23 | C | ↑ | 1.02 | 0.727 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.88 | 0.15 4 | 0.461 |

| Eotaxin 1 | C | ↑ | 1.02 | 0.757 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.96 | 0.431 | 0.727 |

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 | TR | ↑ | 1.01 | 0.758 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.87 | 0.072 | 0.450 |

| Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 | TR | ↑ | 1.03 | 0.805 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.83 | 0.023 | 0.313 |

| Matrix Metalloproteinase 3 | O | ↓ | 0.98 | 0.811 | 0.876 | ↓ | 0.88 | 0.099 | 0.450 |

| Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases 1 | O | ↑ | 1.02 | 0.914 | 0.949 | ↓ | 0.93 | 0.242 | 0. 513 |

| C Reactive Protein | AP | ↓ | 0.44 | 0.992 | 0.992 | ↑ | 1.54 | 0.882 | 0.966 |

Abbreviations: AP, acute-phase protein; C, cytokine; GF, growth factor; TR, transmembrane receptor; O, other.

Footnotes

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Karen Pulford, Editor in Chief

FUNDING: This study was supported by the Stanley Medical Research Institute. JT is supported by the Virgo Consortium, funded by the Dutch government project number FES0908, by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI) project number 050–060–452, by the Dutch Fund for Economic Structure Reinforcement, the NeuroBasic-PharmaPhenomics project (No. 0908), and by the European Union FP7 funding scheme: Marie Curie Actions Industry-Academia Partnerships and Pathways (No. 286334, PSYCH-AID project). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS: JT is a consultant for Psynova Neurotech Ltd. RHY is a member of the Stanley Medical Research Institute Board of Directors and Scientific Advisory Board. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. SB is a consultant for Myriad Genetics Inc. and director of Psynova Neurotech Ltd., although this does not interfere with policies of the journal regarding sharing of data or materials. FBD declares no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Paper subject to independent expert blind peer review by minimum of two reviewers. All editorial decisions made by independent academic editor. Upon submission manuscript was subject to anti-plagiarism scanning. Prior to publication all authors have given signed confirmation of agreement to article publication and compliance with all applicable ethical and legal requirements, including the accuracy of author and contributor information, disclosure of competing interests and funding sources, compliance with ethical requirements relating to human and animal study participants, and compliance with any copyright requirements of third parties. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: RHY, FBD. Analyzed the data: JT. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: JT, FBD. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript, jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper, made critical revisions and agree with the manuscript results and conclusions: JT, RHY, SB, FBD. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Müller N Schwarz MJ. Immune system and schizophrenia. Curr Immunol Rev. 2010;6(3):213–20. doi: 10.2174/157339510791823673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yolken RH, Torrey EF. Are some cases of psychosis caused by microbial agents? A review of the evidence. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(5):470–9. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller N, Schwarz M. Schizophrenia as an inflammation-mediated dysbalance of glutamatergic neurotransmission. Neurotox Res. 2006;10(2):131–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03033242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maes M, Bocchio Chiavetto L, Bignotti S, et al. Effects of atypical antipsychotics on the inflammatory response system in schizophrenic patients resistant to treatment with typical neuroleptics. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;10(2):119–24. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(99)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levkovitz Y, Mendlovich S, Riwkes S, et al. A double-blind, randomized study of minocycline for the treatment of negative and cognitive symptoms in early-phase schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(2):138–49. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04666yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller N, Krause D, Dehning S, et al. Celecoxib treatment in an early stage of schizophrenia: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of celecoxib augmentation of amisulpride treatment. Schizophr Res. 2010;121:1–3. 118–24. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laan W, Grobbee DE, Selten JP, Heijnen CJ, Kahn RS, Burger H. Adjuvant aspirin therapy reduces symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):520–7. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05117yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang ML. Probiotics and prebiotics: immunological and clinical effects in allergic disease. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2009;64:219–35. doi: 10.1159/000235793. discussion 235–18, 251–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desbonnet L, Garrett L, Clarke G, Kiely B, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Effects of the probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis in the maternal separation model of depression. Neuroscience. 2010;170(4):1179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung IH, Jung MA, Kim EJ, Han MJ, Kim DH. Lactobacillus pentosus var. plantarum C29 protects scopolamine-induced memory deficit in mice. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113(6):1498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corridoni D, Pastorelli L, Mattioli B, et al. Probiotic bacteria regulate intestinal epithelial permeability in experimental ileitis by a TNF-dependent mechanism. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e42067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peran L, Camuesco D, Comalada M, et al. Lactobacillus fermentum, a probiotic capable to release glutathione, prevents colonic inflammation in the TNBS model of rat colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21(8):737–46. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0773-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Mahony L, McCarthy J, Kelly P, et al. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(3):541–51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kullisaar T, Songisepp E, Mikelsaar M, Zilmer K, Vihalemm T, Zilmer M. Antioxidative probiotic fermented goats’ milk decreases oxidative stress-mediated atherogenicity in human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2003;90(2):449–56. doi: 10.1079/bjn2003896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, et al. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):e1391–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao AV, Bested AC, Beaulne TM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of a probiotic in emotional symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome. Gut Pathog. 2009;1(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312(5778):1355–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bercik P, Collins SM, Verdu EF. Microbes and the gut-brain axis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(5):405–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(10):701–12. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrett E, Ross RP, O’Toole PW, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. gamma-Aminobutyric acid production by culturable bacteria from the human intestine. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113(2):411–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert JA, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Porazinska DL, Weiss SJ, Knight R. Toward effective probiotics for autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Cell. 2013;155(7):1446–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickerson FB, Stallings C, Origoni A, et al. Effect of probiotic supplementation on schizophrenia symptoms and association with gastrointestinal functioning: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(1) doi: 10.4088/PCC.13m01579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walter S, Weinschenk T, Stenzl A, et al. Multipeptide immune response to cancer vaccine IMA901 after single-dose cyclophosphamide associates with longer patient survival. Nat Med. 2012;18(8):1254–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaidya VS, Ozer JS, Dieterle F, et al. Kidney injury molecule-1 outperforms traditional biomarkers of kidney injury in preclinical biomarker qualification studies. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(5):478–85. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stumhofer JS, Silver JS, Laurence A, et al. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(12):1363–71. doi: 10.1038/ni1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson JEA. User’s Guide To Principal Components. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald CJ, Mazzuca SA, McCabe GP., Jr How much of the placebo ‘effect’ is really statistical regression? Stat Med. 1983;2(4):417–27. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(1):215–20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dieset I, Hope S, Ueland T, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors during second generation antipsychotic treatment are associated with increased C-reactive protein. Schizophr Res. 2012;140:1–3. 169–74. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ooi LG, Liong MT. Cholesterol-lowering effects of probiotics and prebiotics: a review of in vivo and in vitro findings. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11(6):2499–522. doi: 10.3390/ijms11062499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker C, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Antipsychotic drugs and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;341:c4245. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peck A, Mellins ED. Precarious balance: Th17 cells in host defense. Infect Immun. 2010;78(1):32–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00929-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borovcanin M, Jovanovic I, Radosavljevic G, et al. Elevated serum level of type-2 cytokine and low IL-17 in first episode psychosis and schizophrenia in relapse. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(11):1421–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirch DG. Infection and autoimmunity as etiologic factors in schizophrenia: a review and reappraisal. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19(2):355–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Angelucci F, Brene S, Mathe AA. BDNF in schizophrenia, depression and corresponding animal models. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(4):345–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]