Abstract

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), an inducible enzyme up-regulated in Alzheimer's disease, catabolises heme to biliverdin, Fe2+ and carbon monoxide (CO). CO can protect neurones from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis by inhibiting Kv2.1 channels, which mediates cellular K+ efflux as an early step in the apoptotic cascade. Since apoptosis contributes to the neuronal loss associated with amyloid β peptide (Aβ) toxicity in AD, we investigated the protective effects of HO-1 and CO against Aβ1-42 toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells, employing cells stably transfected with empty vector or expressing the cellular prion protein, PrPc, and rat primary hippocampal neurons. Aβ1-42 (containing protofibrils) caused a concentration-dependent decrease in cell viability, attributable at least in part to induction of apoptosis, with the PrPc-expressing cells showing greater susceptibility to Aβ1-42 toxicity. Pharmacological induction or genetic over-expression of HO-1 significantly ameliorated the effects of Aβ1-42. The CO-donor CORM-2 protected cells against Aβ1-42 toxicity in a concentration-dependent manner. Electrophysiological studies revealed no differences in the outward current pre- and post-Aβ1-42 treatment suggesting that K+ channel activity is unaffected in these cells. Instead, Aβ toxicity was reduced by the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine, and by the CaMKKII inhibitor, STO-609. Aβ also activated the downstream kinase, AMP-dependent protein kinase (AMPK). CO prevented this activation of AMPK. Our findings indicate that HO-1 protects against Aβ toxicity via production of CO. Protection does not arise from inhibition of apoptosis-associated K+ efflux, but rather by inhibition of AMPK activation, which has been recently implicated in the toxic effects of Aβ. These data provide a novel, beneficial effect of CO which adds to its growing potential as a therapeutic agent.

Amongst the earliest of events leading to neuronal loss in Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the loss of functional synapses,1, 2, 3 apparent long before deposition of amyloid β peptide (Aβ)-containing plaques.4 Although other parts of the neurone (e.g. the axon or soma) appear intact, their health at this early stage of disease progression is not clear. However, neurones ultimately die in AD and there is clear evidence that numerous events indicative of apoptosis occur even at early stages of disease progression.5, 6, 7, 8 Thus, targeting of apoptotic mechanisms may be of therapeutic value in AD as well as in other neurodegenerative disorders. Furthermore, apoptosis is established as a mechanism of neuronal loss following other types of pathological stresses including ischemia associated with stroke,9 which can predispose individuals to the development of AD.10, 11, 12

Apoptosis is strongly influenced by intracellular K+ levels13 which regulate caspase activation, mitochondrial membrane potential and volume, osmolarity and cell volume.13, 14 K+ loss via K+ channels is a key early stage in apoptosis,15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and K+ channel inhibitors can protect against apoptosis triggered by numerous insults including oxidative stress.20, 21 Evidence suggests a particularly important role for the voltage-gated channel Kv2.1 in this process: expression of dominant negative Kv2.1 constructs (thus lacking functional Kv2.1 channels) protects against oxidant-induced apoptosis, and over-expression of Kv2.1 increases susceptibility to apoptosis.22, 23 Pro-apoptotic agents cause a rapid increase in the surface expression of Kv2.1 channels,24 but whether or not this occurs in AD remains to be determined. Alternative pathways recently reported to promote cell death include activation of the AMP-dependent protein kinase (AMP kinase) which can act either as a Tau kinase25 or to inhibit the mTOR pathway26 and thus contribute to neurodegeneration.

Heme oxygenases (HO) are enzymes widely distributed throughout the body. In the central nervous system, HO-2 is constitutively expressed in neurones and astrocytes, while HO-1 is inducible in both cell types.27, 28, 29, 30 Both HO-1 and HO-2 break down heme to liberate biliverdin, ferrous iron (Fe2+) and carbon monoxide (CO). This catalysis is of biological significance since it is crucial to iron and bile metabolism, and also generates a highly effective antioxidant in bilirubin (from biliverdin via bilirubin reductase). Numerous stimuli can induce HO-1 gene expression,31 including oxidative stress32 and Aβ peptides.33 Importantly, HO-1 is strikingly up-regulated in AD patients, a finding considered indicative of oxidative stress.27, 34, 35 Induction of HO-1 is clearly a neuroprotective response (although in some cases can exert detrimental effects27). However, there is growing evidence that CO can be neuroprotective, for example against the damage of focal ischemia.36 Our recent studies have demonstrated that CO provides protection against oxidant-induced apoptosis by selectively inhibiting Kv2.1.23, 37 In the present study, we have investigated whether HO-1, or its product CO, can provide protection against Aβ-induced toxicity in the human neuroblastoma, SH-SY5Y, and in rat primary hippocampal neurones, and whether this involves regulation of K+ channels. We show that both HO-1 and CO protect cells against the toxicity of protofibrillar Aβ1-42 but that protection does not arise from inhibition of apoptosis-associated K+ efflux, but rather by inhibition of AMPK activation.

Results

Aβ(1-42)-induced cell death in SH-SY5Y cells

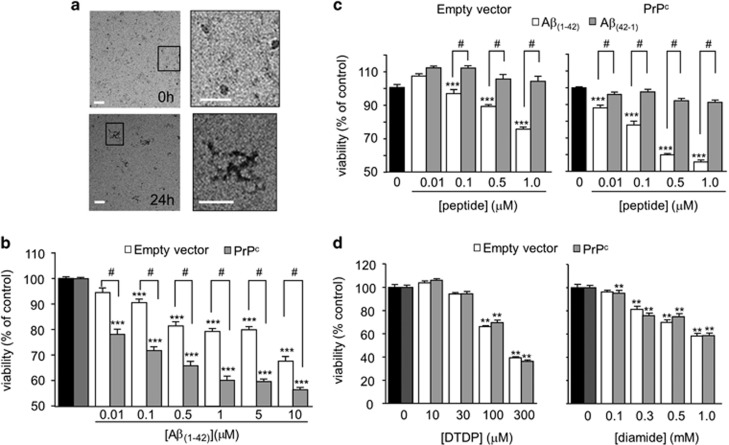

To investigate any potential role of HO-1 and CO in affording protection against toxicity induced by Aβ(1-42) (hereafter referred to simply as Aβ), we first determined their effectiveness in SH-SY5Y cells either expressing the cellular prion protein (PrPc) or containing the empty vector, as PrPc is a receptor for oligomeric38, 39 and protofibrillar40 forms of Aβ. Freshly dissolved Aβ which contained small globular structures (<10 nm) and Aβ monomers (Figure 1a, upper images) had no effect on cell viability (not shown). After 24 h incubation at 37 °C, in addition to the small globular assemblies and monomers, the Aβ had formed protofibrils (25–90 nm in length) as assessed by electron microscopy (Figure 1a, lower images). These structures closely resembled the nanotubes that have recently been shown to mediate PrPc-dependent and –independent synaptotoxicity.40 There was no evidence of any amyloid fibrils in our preparations. Using MTT assays to evaluate cell viability following exposure to Aβ for 24 h, we found that the protofibrillar Aβ caused a concentration-dependent loss of viability, and that cells over-expressing PrPc were significantly more sensitive to Aβ toxicity than the cells lacking PrPc (Figure 1b). Extending the incubation period to 48 h did not increase toxicity further (data not shown). Neither the PrPc-expressing nor the empty vector containing cells were significantly affected by the reverse sequence peptide (Aβ(42-1)) (Figure 1c). Consistent with the idea that PrPc at least partly mediates aggregated Aβ toxicity,38, 39, 40 over-expression of PrPc appeared to confer specific sensitivity to Aβ toxicity, since both the PrPc expressing and empty vector containing cells were similarly sensitive to the oxidizing agents dithiodipyridine (DTDP) and diamide (Figure 1d), both of which have previously been shown to induce apoptosis.23, 37

Figure 1.

Aggregation of Aβ1-42 into protofibrils is toxic to SH-SY5Y cells. (a) Representative images seen by negative stain electron microscopy of globular aggregates seen in Aβ freshly dissolved in DMEM (0 h, upper images). Boxed area of left-hand image is magnified in right-hand image to show more detail of these structures. Lower images show globular aggregates plus protofibrillar structures in Aβ solutions stored at 37 oC for 24 h. Boxed area of left-hand image is magnified in right-hand image to show more detail of these structures. Scale bar in all images 50 nm. (b) Effect of Aβ1-42 on cell viability in SH-SY5Y cells containing empty vector (white bars) and stably expressing PrPc (gray bars) using the mitochondrial activity-based MTT assay. Bars represent the mean±S.E.M. data of cells from 10 repeats (each performed in duplicate) with cells from different passages. (c) The effect of different concentrations of Aβ1-42 (white bars) and the reverse sequence Aβ42-1 (gray bars) on cell viability in empty vector containing and PrPc-expressing cells. Bars show the mean±S.E.M. of four repeats. Statistical significance was determined with a one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. ***P<0.001, #P<0.01. (d) Effect of oxidants on cell viability in empty vector containing (white bars) and PrPc-expressing (gray bars) cells. Left, effect of different concentrations of DTDP (10 min exposure, left) on cell viability. Each bar represents the mean±S.E.M. of seven repeats. Right, cell viability following a 30 min exposure to various concentrations of diamide. Each bar shows the mean±S.E.M. of five repeats using cells from different passages. Statistical significance is denoted by **P<0.01, compared to the corresponding control cells

Aβ-induced cell death is at least partly attributable to apoptosis

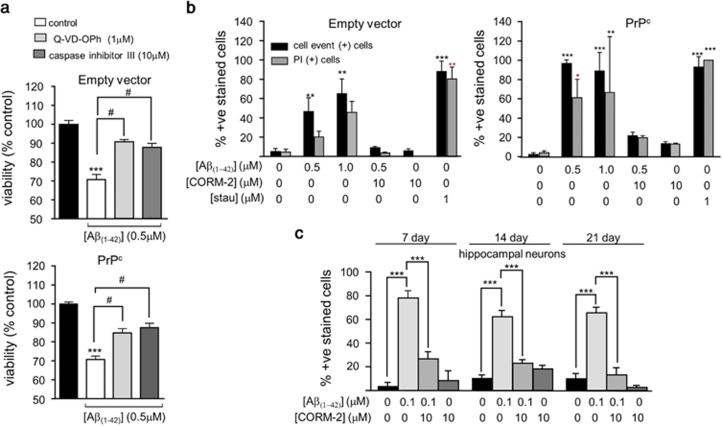

To investigate whether Aβ-induced toxicity arose from induction of apoptosis, two separate approaches were taken. The reduction in cell viability caused by Aβ was significantly reduced by two distinct caspase inhibitors, the pan-caspase inhibitor (Q-VD-OPh; 1 μM) or the irreversible caspase inhibitor III (Boc-D-FMK; 10 μM) (Figure 2a), consistent with the idea that Aβ toxicity involves activation of apoptosis. In both PrPc-expressing cells and empty vector containing cells, Aβ caused an increase in the proportion of both CellEvent positive and PI-positive cells (i.e. cells showing increased caspase activity and loss of viability), approaching levels seen in cells treated with staurosporine, which induced positive caspase and PI staining in 80–100% of cells (Figure 2b). These data further support an important role for apoptosis induction in the Aβ−induced loss of cell viability. Using this same assay, we also observed that the CO-donor, CORM-2, significantly attenuated the number of CellEvent and PI-positive cells following exposure to 0.5 μM Aβ (Figure 2b), suggesting a possible protective role for CO against Aβ toxicity. Importantly, we confirmed this potentially protective effect of CO in cultured rat primary hippocampal neurones (Figure 2c). Thus, employing cultures ranging from 7–21 days in vitro, we found that the same protofibrillar preparation of Aβ at a concentration of 100 nM caused marked increases in the number of apoptotic cells (indicated by CellEvent positive cells). Effects were found at all culture ages, and Aβ was more potent in inducing apoptosis in hippocampal neurones than in the SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 2c). In the presence of CORM-2 (10 μM), the effects of Aβ on hippocampal neurones were largely reversed, and CORM-2 was without significant effect itself on apoptosis (Figure 2c). These findings indicate that the neuroprotective effects of CO against Aβ toxicity can be observed in different neuronal preparations.

Figure 2.

Amyloid toxicity is partly attributable to induction of apoptosis and reversed by CORM-2. (a) Effect on cell viability in empty vector containing (upper) and PrPc-expressing (lower) cells following 24 h treatment with 0.5 μM Aβ1-42 alone or in the presence of either of two different caspase inhibitors; Q-VD-OPh (1 μM) and caspase inhibitor III (10 μM), as indicated. Black bars represent untreated cells. Bars indicate mean±S.E.M. of three repeats with cells from different passages for empty vector containing cells and four repeats for the PrPc-expressing cells. Statistical significance is denoted by ***P<0.001 when compared with the corresponding untreated control and #P<0.001 when compared with the corresponding Aβ1-42 treated cells. (b) CellEvent positive cells indicate activated caspase 3. Black bars represent the percentage of CellEvent positive cells and gray bars represent the percentage of PI-positive cells compared with Hoescht positive cells in the area counted. Treatments were for 24 h with the concentrations of drugs indicated. As a positive control, cells were also treated with 1 μM staurosporine for 10 min and stained with CellEvent and PI. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated with cells from three different passages. Statistical significance is denoted by **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 when compared with the corresponding untreated cells. (c) Summary of the CellEvent staining experiments for 7, 14 and 21 day old hippocampal neurons, as indicated. Bars represent the percentage of CellEvent positive cells compared to the total number of Hoechst positive cells in the area counted. Cells were treated for 24 h with 100 nM Aβ1-42, 100 nM Aβ1-42+10 μM CORM or 10 μM CORM alone, as indicated. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated with cells from three different isolations and shown as mean±S.E.M. Statistical significance is denoted by ***P<0.001 compared with the untreated cells of that specific age group

HO-1 induction protects against Aβ toxicity

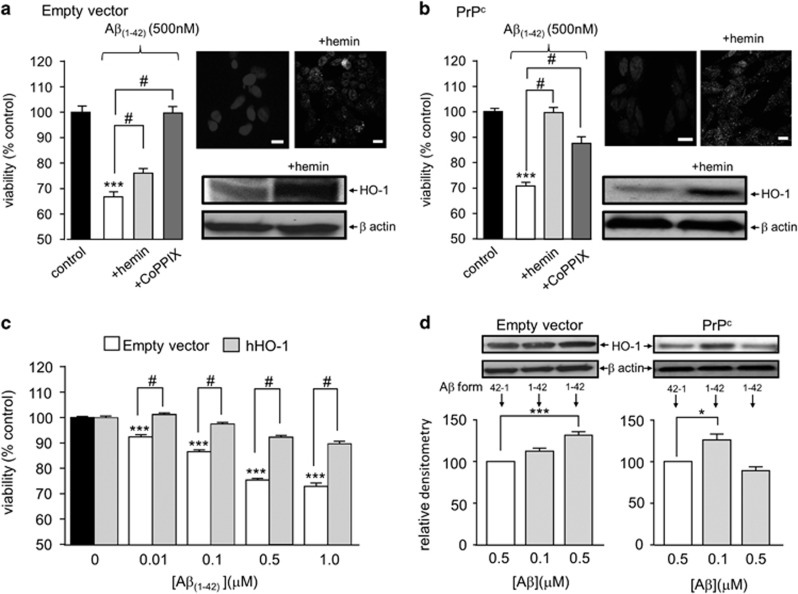

In order to investigate the ability of HO-1 to protect against Aβ toxicity, cells were exposed to two established inducers of this enzyme. Exposure to either 30 μM hemin or 3 μM CoPPIX for 24 h significantly attenuated the toxic effects of Aβ in both empty vector containing (Figure 3a) and PrPc-expressing SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 3b). HO-1 induction was verified by immunocytochemistry and western blotting in response to hemin (similar results obtained for CoPPIX; data not shown). Densitometric analysis indicated that hemin increased HO-1 expression to 188.0±5.0% of control levels (i.e. 1.88-fold; P<0.001, n=4 repeats) in empty vector containing cells, and by 239.5±28.8% (P<0.05, n=4 experiments) in PrPc-expressing cells. These data suggested that HO-1 affords protection against Aβ in addition to its known ability to protect against oxidant-induced apoptosis. To investigate this further, we over-expressed HO-1 in SH-SY5Y cells. As shown in Figure 3c, HO-1 over-expression also significantly diminished the toxic effects of Aβ. Since exposure to Aβ is clearly deleterious to cells, we also examined whether Aβ itself could induce expression of HO-1. As shown by western blotting in Figure 3d, 24 h exposure to Aβ did indeed increase expression of HO-1 in empty vector and PrPc-expressing cells, respectively. Interestingly, there was differential sensitivity to Aβ in the two cell groups: For empty vector cells, a graded increase in HO-1 induction was observed, but in PrPc-expressing SH-SY5Y cells significant induction was observed in response to 100 but not 500 nM Aβ. In both cell groups, induction was modest compared with the effects of hemin or CoPPIX.

Figure 3.

HO-1 protects against Aβ toxicity. (a) Cell viability measured in empty vector containing cells following 24h induction of HO-1 with either 30 μM hemin or 3 μM CoPPIX in the presence of 500 nM Aβ. Bars indicate mean±S.E.M. of four repeats with cells from different passages. Right (upper) immunofluorescent images of untreated empty vector containing cells (left) and cells treated with 30 μM hemin (right) for 24 h and then probed using anti-HO-1 primary antibody and DAPI for nuclear staining. Lower; western blot detection of HO-1 following identical hemin induction. β actin blots are also shown to indicate even loading of protein. (b) As (a) except studies were conducted in PrPc-expressing cells. (c) Effect of different concentrations of Aβ on empty vector containing cells (black and clear bars) and cells stably over-expressing hHO-1. Bars represent mean±S.E.M. of six repeats (done in duplicate). (d) Detection of HO-1 induced by Aβ in both cell groups. Upper, example blots from cells exposed either to Aβ42-1 (used as a control) or Aβ1-42 at the two concentrations indicated in the bar graphs, below. These show mean densitometric analysis of induced expression in empty vector and PrPc-expressing cells. Bars represent mean±S.E.M. of four repeats (done in duplicate). Statistical significance is denoted by ***P<0.001 and *P<0.05 when compared with the corresponding untreated control and #P<0.001 when compared to the corresponding Aβ treated cells

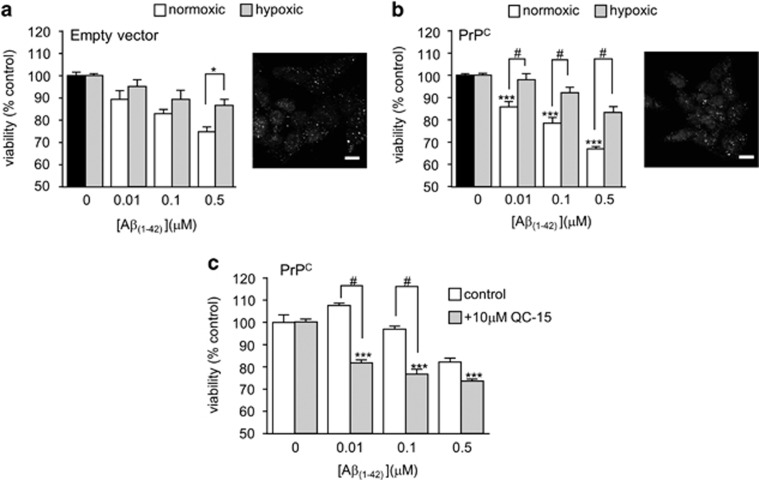

Hypoxia has long been known to induce HO-1 expression,41, 42 so we investigated the sensitivity to Aβ of cells which had been maintained in a hypoxic environment (0.5% O2, 24 h) prior to (and during) exposure to Aβ. Hypoxia did indeed induce HO-1 expression, as determined immunocytochemically, and hypoxic cells (both PrPc-expressing and empty vector containing cells) were significantly more resistant to the toxic actions of Aβ (Figures 4a and b). This was particularly prominent in the PrPc-expressing cells. We therefore used these cells exclusively to examine the ability of the HO-1 inhibitor QC-1543 to modulate the responses of hypoxia-exposed cells to Aβ. As shown in Figure 4c, QC-15 reversed the protective effects of hypoxia against Aβ toxicity, suggesting strongly that the protective effects of hypoxia were specifically because of its induction of HO-1.

Figure 4.

Protective effect of hypoxia against Aβ toxicity. (a) Effect of hypoxia (48 h, 0.5% O2) on Aβ-induced loss of cell viability in empty vector containing cells. Bars show mean±S.E.M. of four repeats. Right, immunofluorescent images using anti-HO-1 primary antibody showing upregulation of HO-1 following 48 h of hypoxia. (b) As (a) except studies were conducted in PrPc-expressing cells. (c) Effects of Aβ on cell viability in hypoxic PrPc-expressing cells in the absence (open bars) and presence (shaded bars) of the HO-1 inhibitor, QC-15. Bars represent the mean±S.E.M. of four repeats. Statistical significance is denoted by ***P<0.001, #P<0.01 when compared with corresponding control and corresponding Aβ1-42 treated cells, respectively

CO protects against Aβ toxicity: lack of involvement of a K+ channel ‘surge'

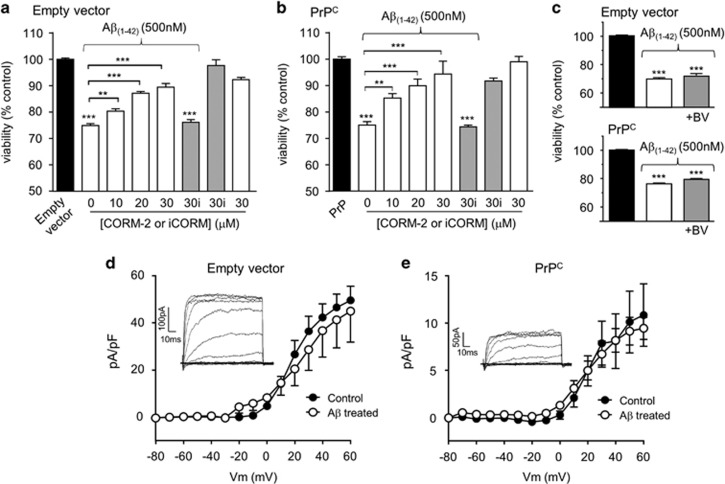

In order to examine whether the protective effects of HO-1 induction / over-expression could be attributable to its ability to generate CO (as suggested by the data presented in Figure 2), we examined the ability of the CO-donor, CORM-2, to protect cells against Aβ toxicity. In both empty vector containing cells (Figure 5a) and PrPc-expressing cells (Figure 5b), exposure of cells to CORM-2 caused a concentration-dependent reduction in the toxic effects of Aβ. The control compound, iCORM, was without significant effect, and neither CORM-2 nor iCORM affected viability when applied alone. These data support the hypothesis that HO-1 affords protection against Aβ toxicity via the production (and subsequent action) of CO. In further support of this hypothesis, we examined the effects of biliverdin (also produced by HO-1) on Aβ toxicity. As shown in Figure 5c, exposure of cells to 10 μM biliverdin was without effect on the toxicity of Aβ in both cell groups, further supporting the proposal that CO mediates the protective effects of HO-1 in these cells.

Figure 5.

CO protects against Aβ-induced toxicity independently of K+ channel activity. Change in cell viability in empty vector containing (a) and PrPc-expressing (b) cells following a 24 h treatment with 500 nM Aβ in the absence or presence of various concentrations of the CO-donor CORM-2 (white bars). Also shown is the lack of effect of iCORM (gray bars) at 30 μM. CORM or iCORM when applied alone had no effect on cell viability. Bars represent mean±S.E.M. of six repeats for the empty vector containing cells and 14 repeats for PrPc-expressing cells. Statistical significance is indicated by ***P<0.001, #P<0.01 when compared to the corresponding control and corresponding Aβ1-42 treated cells, respectively. (c) Change in cell viability in empty vector containing (upper) and PrPc-expressing (lower) cells following a 24 h treatment with 500 nM Aβ in the absence or presence of 10 mM biliverdin (BV), as indicated. Bars represent the mean±S.E.M. of 4 repeats. (d, e) Mean (± S.E.M., n=7–9 cells in each case) current density versus voltage relationships determined in empty vector containing (d) and PrPc-expressing cells (e) with (open symbols) or without (solid symbols) exposure to 1 μM Aβ for 24 h. Inset shows example families of currents, evoked by step depolarizations (to between −20 and +60 mV) applied from a holding potential of −70 mV, from which the mean plots were calculated

Since exposure of cells to Aβ triggers apoptosis, we investigated whether this was also associated with increased K+ channel activity at the plasma membrane. Previous studies have shown this is a key event in oxidant-induced apoptotic cell death,22, 44 and we have shown previously that CO is protective against apoptosis triggered by a K+ channel ‘surge' (i.e. rapid insertion of channels into the membrane) by inhibiting the activity of these channels (specifically, Kv2.123, 37). Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings revealed that K+ current densities, indicative of K+ channel activity at the plasma membrane, were not significantly affected by exposure to Aβ for 24 h in either the vector only containing cells (Figure 5d) or in the PrPc-expressing cells (Figure 5e). However, it was noted that K+ current density was significantly reduced in PrPc-expressing cells as compared with empty vector containing cells. The reasons for this are currently unknown. This notwithstanding, cell death induced by Aβ was not attributable to the K+ channel ‘surge' associated with oxidant-induced apoptosis, indicating that HO-1/CO provided protection against Aβ toxicity via an alternative mechanism.

Involvement of the CaMKKII/AMPK pathway in Aβ neurotoxicity

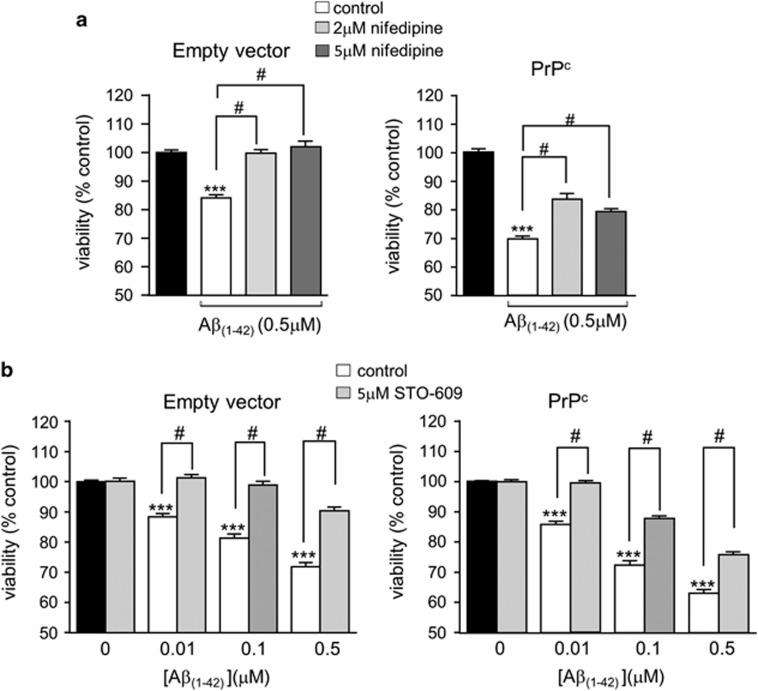

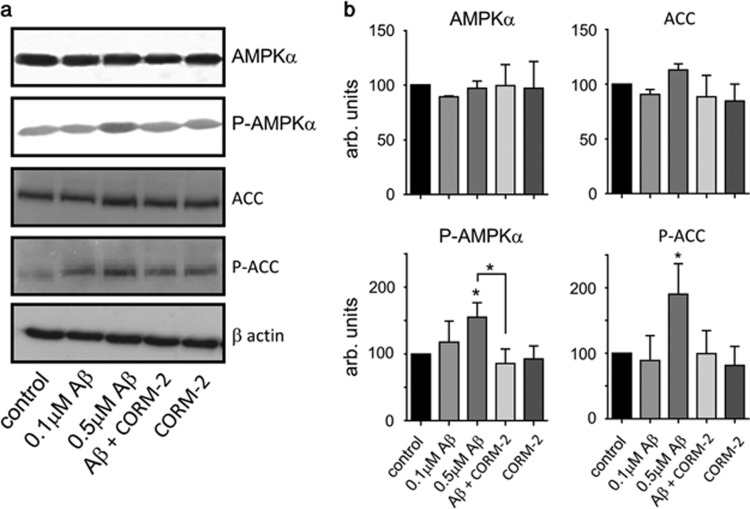

Recent studies have suggested that Aβ neurotoxicity can involve activation of the Ca2+ /calmodulin kinase kinase II (CaMKKII)/AMPK pathway.25, 26 To investigate the involvement of this pathway in Aβ−induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells as reported here, we first investigated the effects of suppressing Ca2+ influx into cells using the l-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor nifedipine. Nifedipine significantly attenuated Aβ toxicity in both empty vector containing cells and PrPc-expressing cells (Figure 6a), suggesting Ca2+ influx via l-type Ca2+ channels is involved in Aβ toxicity. Since a rise of [Ca2+]i can lead to activation of CaMKKII, we next explored the involvement of this kinase in Aβ toxicity, and found that exposure of cells to the CaMKKII inhibitor STO-609 also significantly attenuated Aβ toxicity (Figure 6b). Exposure to both nifedipine and STO-609 produced no additional attenuation above that observed by either agent applied alone (data not shown). In agreement with recent studies, we also found that Aβ activated AMPK, as demonstrated by a specific increase in the level of AMPK phosphorylation (without change in total AMPK expression levels (Figure 7)). In further support of this, we found that Aβ increased the level of ACC phosphorylation, the major AMPK substrate. Importantly, CO (applied as CORM-2) prevented AMPK activation and subsequent phosphorylation of ACC (Figures 7a and b).

Figure 6.

Aβ toxicity involves Ca2+ influx and CamKKII activation. (a) Cell viability monitored in empty vector containing (left) and PrPc-expressing cells (right) following exposure to Aβ applied for 24 h either alone or in the additional presence of nifedipine, as indicated. Bar graphs show the mean±S.E.M. of five repeats each for empty vector containing and PrPc-expressing cells. Statistical significance: ***P<0.001 and #P<0.01 compared to corresponding control and corresponding Aβ1-42 treated cells, respectively. (b) Cell viability monitored in empty vector containing (left) and PrPc-expressing cells (right) following exposure to Aβ applied for 24 h either alone or in the additional presence of the CAMKK inhibitor STO-609. Black bars represent the respective untreated cells, clear bars represent cells treated with Aβ and gray bars represent cells treated with Aβ together with 5 μM STO-609. Bars represent the mean±S.E.M. of four repeats for the empty vector containing and six repeats for the PrPc-expressing cells. Statistical significance is denoted by ***P<0.001, #P<0.01 when compared with corresponding control and corresponding Aβ1-42 treated cells, respectively

Figure 7.

CO prevents AMPK activation by Aβ. (a) Example western blots showing total and phosphorylated AMPKα, total and phosphorylated acetyl–CoA carboxylase (ACC) and the corresponding β actin levels in lysates from PrPc-expressing cells. Cells were either untreated, or exposed to Aβ (100 and 500 nM, 24 h), or to 500 nM Aβ in the additional presence of 20 μM CORM-2, or to CORM-2 alone, as indicated. (b) Mean (±S.E.M., from three experiments) densitometry data under each of the conditions exemplified in (a). Statistical significance indicated by *P<0.05 when compared with corresponding control and corresponding Aβ1-42 treated cells, respectively

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate whether HO-1, via CO generation, provides neuroprotection against the toxicity of Aβ. There is compelling evidence to suggest that increased HO-1 expression can be neuroprotective against exposure to glutamate, oxidants or physical damage,27, 45 and this protection may be attributable, at least in part, to the production of CO (e.g. Zeynalov et al.36). Although much of the cellular damage associated with AD is reminiscent of oxidative damage caused by such agents/interventions, it is important to establish the specific mechanisms underlying neurodegeneration in AD, in order to understand any protective actions of HO-1/CO and so, potentially, exploit such actions in the development of new anti-neurodegenerative therapies. Indeed, whilst expression of HO-1 has long been known to be increased in AD patients,27 it remains to be fully resolved whether this is beneficial or detrimental. Detrimental effects arising from increased HO-1 expression specifically in glia, have been associated with excessive deposition of iron as a consequence of increased heme degradation.46, 47, 48 However, other studies suggest increased astrocytic HO-1 expression can provide protection for nearby neurons arising specifically from the production of CO.49

The present study indicates that HO-1 is indeed protective, and protection appears to arise via the production of CO. Our study employed SH-SY5Y cells over-expressing PrPc and demonstrated that such cells were more vulnerable to the toxicity of Aβ when compared with the empty vector containing cells which lack endogenous PrPc expression50 (Figure 1). Aβ has been show to aggregate and assemble into a range of dynamic, soluble species, and defining the particular in vivo ‘toxic' species which correlate most significantly with AD progression is challenging. PrPc has been identified as a high-affinity receptor for oligomeric Aβ.38, 39, 51, 52, 53 PrPc is thought to be a critical mediator of the synaptic loss, neurotoxicity, long-term potentiation impairments and memory deficits that are caused by these Aβ oligomers.38, 51, 52 However, the heterogeneity and lack of characterization of the synthetic Aβ preparations used in some of these studies makes it difficult to define the active PrPc-dependent Aβ toxic assemblies. A recent report40 identified protofibrils to be a key PrPc-specific binding species, defining their triple helical structure as Aβ nanotubes. These particular structures of Aβ caused PrPc-dependent synaptotoxicity.40 Electron microscopy indicated that our preparation of Aβ resembles those used in that particular study, and thus provide an explanation as to why our PrPc-expressing cells were selectively more vulnerable to Aβ toxicity, when their sensitivity to apoptosis induced by oxidants was similar to that seen in cells lacking PrPc (Figure 1).

Several lines of evidence suggest that HO-1 provided neuroprotection, reducing the toxic effects of Aβ: thus, chemical induction of HO-1 with protoporphyrins (Figures 3a and b) or over-expression of HO-1 (Figure 3c) reduced the toxic actions of Aβ. Furthermore, protection was provided by hypoxic induction of HO-1 (Figure 4). Such hypoxic treatment can alter the expression of many proteins which might contribute to neuroprotection (see e.g.54 yet this effect of hypoxia was prevented by the selective HO-1 inhibitor, QC-15.43 Collectively, these data strongly suggest that HO-1 provides protection against the toxic actions of Aβ. Furthermore, our results also indicate that HO-1 is likely to be protective because of its ability to generate CO. Thus, although HO-1 activity was not assessed directly (e.g. via measurement of CO or bilirubin production) the established CO-donor, CORM-2 (but not the inactive form, iCORM) mimicked the effects of HO-1 induction (Figures 2 and 5) to provide protection against Aβ toxicity. Furthermore, another HO-1 product, biliverdin, was without protective effect (Figure 5).

Our previous work has indicated that HO-1, through the production of CO, protects hippocampal neurons from oxidant-induced apoptosis by inhibiting the voltage-gated K+ channel Kv2.1.23 Similarly, HEK293 cells over-expressing Kv2.1 displayed increased vulnerability to oxidant-induced apoptosis, and this was also prevented by CO inhibition of Kv2.1.23 Since earlier reports had suggested that toxic effects of Aβ might arise due to its ability to increase outward K+ currents,55, 56 we explored this as a possible mechanism by which CO might protect SH-SY5Y cells against Aβ toxicity. Perhaps surprisingly, K+ currents in SH-SY5Y cells were unaffected by the same levels of Aβ which induced toxicity (Figure 5). The discrepancy between this finding and earlier reports on the ability of Aβ to augment K+ currents is not clear at present, but it is noteworthy that previous studies employed Aβ at high (>10 μM) concentrations,55, 56 whereas the present study largely employed sub-micromolar concentrations of Aβ. Our results indicate that K+ channel modulation is unlikely to account for the toxic actions of Aβ and, therefore, the protective effects of CO. Our data also contrast with an earlier report that expression of PrPc is associated with augmentation of K+ currents carried by Kv4.2,57 although we do not know the contribution of Kv4.2 to whole-cell K+ currents in SH-SY5Y cells employed here.

In order to explore alternative pathways by which CO might afford neuroprotection, we first examined the effects of the l-type Ca2+ channel blocker, nifedipine. Clinical studies have shown that this class of channel blocker is beneficial in slowing down the progression of AD,58 and we found nifedipine to provide significant relief from Aβ toxicity (Figure 6a). This finding prompted us to investigate potential Ca2+-dependent pathways associated with Aβ toxicity. Several studies have implicated AMPK - which can be activated by the Ca2+-dependent upstream kinase, CaMKKβ - as exerting important influences on the development of AD. Thus, for example, Thornton et al.,25 demonstrated that exposure of cortical neurones to Aβ (20 μM, 30 min) activates AMPK in a CaMKKβ-dependent manner and, importantly, that AMPK subsequently acts as a Tau kinase, contributing to its hyperphosphorylation. Yoon et al.26 also reported that Aβ activates AMPK, and indicated that this led to endoplasmic reticulum stress arising from inhibition of the mTOR pathway. This in turn led to activation of JNK3 which, crucially, phosphorylated APP (amyloid precursor protein). This phosphorylation of APP promotes its internalization and cleavage to generate increased levels of Aβ. Most recently, Ca2+ and CaMKKβ-dependent AMPK activation by Aβ was confirmed in a study which also demonstrated that activation of the kinase led to a loss of dendritic spines (an early feature of AD) and also to Tau phosphorylation.59 Our data indicate that Aβ activates AMPK in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 7). Furthermore, this activation is prevented by CO. The exact site at which CO acts to prevent AMPK activation, and therefore provide neuroprotection, remains to be determined. However, this is worthy of further exploration: despite its deserved reputation as a potent toxin, the physiological actions of endogenous CO, and its potential as a therapeutic agent in numerous disorders, is increasingly being recognized (e.g. Motterlini et al.60). Future studies will reveal whether it may also be of benefit in combatting neurodegenerative diseases.

Materials and Methods

Tissue culture

All experiments were conducted using SH-SY5Y cells stably transfected with either empty pIRESneo vector (BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK; termed empty vector containing cells in this study) or engineered to express murine PrPc containing the 3F4 epitope tag (human M108/M111; termed PrPc cells), as described previously.50 Cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing glutamine, supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 U/ml) (all from GIBCO Life Sciences, Paisley, Scotland, UK). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified incubator gassed with 95% air and 5% CO2, passaged every 7 days and used up to 10 passages.

Human HO-1 over-expressing SH-SY5Y cells were generated in-house and cultured using DMEM media with glutamine, supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 U/ml) (all from GIBCO) and hygromycin B (200 μg/ml; Calbiochem, Watford, UK). Briefly, SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with the appropriate pcDNA3.1/human HO-1 construct (Genbank Accession No.: NM_002133.2) using electroporation (Amaxa - Lonza, Slough, UK) according to manufacturer's instructions. Stably transfected cell lines were selected with hygromycin B antibiotic (200 μg/ml, Calbiochem) added 3 days after transfection. Selection was applied for 4 weeks (media changed every 4-5 days), colonies were then picked, grown to confluence and screened by western blotting for HO-1 expression after culturing in T25 flasks for 24–48 h. Hygromycin B selection was maintained throughout the cloning process at 200 μg/ml and in all subsequent passages once stable clones had been positively identified.

Primary cultures of hippocampal neurones

Hippocampi of 6–8-day-old Wistar rats were removed as described previously.39, 61 Brain tissue was incubated with 0.25 μg/ml trypsin for 15 min at 37 °C in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Trypsin digestion was terminated by the addition of equal amounts of PBS, supplemented with 16 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor (type I-S; Sigma, Paisley, UK), 0.5 g/ml DNase I (type II from bovine pancreas; 125 kilounits/ml; Sigma), and 1.5 mM MgSO4. The tissue was then pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 5 min, resuspended in 2 ml of PBS with 100 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 0.5 μg/ml DNase I and 1.5 mM MgSO4, triturated gently, and then centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min to pellet the hippocampal neurons. The pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of minimal Earle's medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 13 mM glucose, 50 IU/ml penicillin, and 50 g/ml streptomycin and added to poly-l-lysine (1.5 mg/ml)-coated coverslips (0.5 ml/well for 24-well plates). After 24 h, the medium was topped up to 1 ml. After a further 24 h, the culture medium was replaced with one containing 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated horse serum and 80 μM fluorodeoxyuridine to prevent proliferation of non-neuronal cells. After a further 24 h, the medium was replaced with serum-free Neurobasal medium, supplemented with 2% (v/v) B27, 50 IU/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 80 μM fluorodeoxyuridine, 25 mM glutamic acid, and 0.5 mM glutamine.

The cell media used to treat the 7 day cells consisted of neurobasal media supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 U/ml), 1% N-2 supplement (to prevent astrocyte growth) and 0.1% Glutamax (all from GIBCO). The media used for treating the 14 and 21 day cells was free of glutamax as it becomes toxic to the cells at this stage.

Aβ preparation and assessment

Aβ1-42 and Aβ42-1 (r-Peptides, Bogart, GA, USA) were dissolved in DMEM (Gibco) to make up 100 μM stock solutions and kept at −20 ºC. When needed for experiments one aliquot was maintained at 37 °C for 24 h to form oligomers prior to treating the cells. EM images were analyzed using FIJI (ImageJ-2). Briefly, all images were magnified (400%) using Photoshop CS5.1 (Adobe Systems Inc., Maidenhead, UK) and the longest dimension of all globular assemblies and protofibrillar structures in each resulting image were measured after setting the pixel/scale ratio.

Cell viability assays

Cell viability was investigated using thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays. Cells were cultured in poly-lysine coated 96-well plates to >50% confluence. The final volume of each well after any treatment was kept at 100 μl. Cells were treated for 24 h with different concentrations of either Aβ1-42 or Aβ42-1 dissolved in serum-free culture media. Likewise, the media in control wells was also replaced with serum-free media for 24 h to ensure that any effects observed were due to Aβ application rather than serum withdrawal. This was done for all the experiments involving Aβ application. When applying CORM-2 for 24 h, cells were treated twice per day (9.30am and 5pm). Following 24 h treatments with Aβ and CORM-2, the media was discarded and the cells gently washed (2x) with PBS to remove all traces of CORM-2, and so avoid a direct reaction with MTT. PBS was then replaced with 100 μl of fresh cell culture media in each well. 11 μl of MTT solution (5 mg/ml in sterile PBS, Sigma) was then added to each well (10% by volume) and the cells incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Post-incubation, an equal volume (111 μl per well) of solubilizing solution, consisting of isopropanol and HCl (24 ml propan-1-ol/isopropyl alcohol (Sigma)+1 ml 1 M HCl), was added to each well to lyse the cells. The contents of each well were thoroughly mixed by pipetting. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm and at 630 nm using a spectrophotometer. The experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated using cells from at least 3 different passages to ensure reliability of the results. All results were normalized to untreated control cells and shown as a percentage change in cell viability compared to the corresponding controls.

To determine the proportion of cell death attributable to apoptosis, we employed the CellEvent staining protocol for both SH-SY5Y cells and hippocampal neurons. For this, cells were cultured on poly-lysine coated glass coverslips in 6-well plates as above, and then (after cells reached ca. 50% confluence) treated for 24 h with 500 nM or 1 μM Aβ1-42, Aβ1-42+CORM-2, or staurosporine (applied at 1 μM for 10 min). Following treatment, cell media was discarded and the CellEvent dye (8 μM in PBS, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) applied for 30 min in the dark at 37 ºC. Thereafter, following a rapid wash, cells were incubated with propidium iodide (500 nM, Invitrogen) for 5 min. Coverlips were washed again with PBS prior to applying 2 drops of Hoechst 33342 solution (Invitrogen) to 1 ml of PBS in each well, and then incubated for 20 min in the dark in order to stain nuclei. After further washing (3 × 5min in the dark), cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, then washed gently with PBS and the coverslips mounted on slides using mounting medium (VectashieldR, Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK). The coverslips were sealed and examined using a Nikon E600 light microscope (Nikon, Kingston upon Thames, UK). All the images were obtained using the x40 lens and Q imaging micropublisher ACQuis (Syncroscopy, Cambridge, UK) software. At least three fields of interest were taken for each slide, and the number of cells with Hoechst positive nuclei that also stained positive for CellEvent or PI were counted. The data is presented as a percentage of (+) CellEvent or PI stained cells compared to the corresponding Hoechst (+) cells.

Hippocampal neurones were cultured on poly-lysine coated coverslips for 7, 14 or 21 days. On the specific days, the coverslips were washed twice with sterile PBS twice to get rid of cell debris and the cells were then treated for 24 h with fresh media for the control cells or media containing 100 nM Aβ1-42, 10 μM CORM or 100 nM Aβ1-42+10 μM CORM. Following the 24 h incubation period, the cells were stained with the CellEvent dye and examined and analyzed exactly as for SH-SY5Y cells.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were cultured on poly-lysine coated glass coverslips in 6-well plates at>50% confluence prior to treatment with either 3 μM cobalt protoporphyrin (CoPPIX) or 30 μM chloroferriprotoporphyrin (hemin; Calbiochem) for 24 h, or prior to exposure to hypoxia (0.5% O2, 48 h). Following said treatments, cells were immunostained for HO-1. Briefly, media was discarded and the cells were washed (3 × 5min) with Dulbecco's PBS. Cells were then fixed with parafomaldehyde (4% in PBS) for 20 min, following which they were permeabilized with PBS containing 0.22% Triton X100 supplemented with 10% normal goat serum (NGS; Sigma). Following 3 × 5 min washes with Dulbecco's PBS containing 1% NGS, cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody; rabbit polyclonal anti-HO-1 (1 : 100, Santa Cruz, Heidelburg, Germany) in Dulbecco's PBS containing 1% NGS. The following day, cells were washed with Dulbecco's PBS containing 1% NGS (3 × 5 min). Antibody binding was visualized by incubating the cells with a secondary antibody; Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1 : 1000, Invitrogen), for 1h in the dark. Post-incubation, and following 3 × 5 min washes with Dulbecco's PBS, coverslips were mounted on slides using VectashieldR mounting media containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories). The slides were then examined using a Zeiss (Cambridge, UK) laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510).

Electrophysiology

Fragments of coverslip with attached cells were transferred to a continuously perfused (3–5 ml/min) recording chamber mounted on the stage of an Olympus (Southend, UK) CK40 inverted microscope. All experiments were carried out at 22±1 °C, unless otherwise stated. Cells were continually perfused with a solution containing (in mM): 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 2.5 CaCl2, 10 D-glucose (pH 7.4 with NaOH). Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were then obtained in voltage-clamp mode with cells clamped at −70 mV. Patch pipettes had resistances 4-6 MΩ when filled with an intracellular solution consisting of (in mM): 10 NaCl, 117 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 11 HEPES, 11 EGTA, 1 CaCl2, 2 Na2ATP (pH 7.2 with KOH). After breaking into the whole-cell configuration, series resistance was monitored throughout the duration of experiments. If a significant increase occurred (>20%), the experiment was terminated. Signals were acquired using a Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) controlled by Clampex 9.0 software via a Digidata 1322A interface (Axon Instruments Inc.). Data were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 2 kHz. To evoke ionic outward K+ currents in SHSY5Y cells, a series of 100 ms depolarizing steps from −80 to +60 mV, in 10 mV increments, were employed. Offline analysis was carried out using the data analysis package Clampfit 9 (Axon Instruments) and data are expressed as mean±S.E.M.

Western blotting

Cells used for immunoblotting were cultured in T25 flasks and when confluent, washed in PBS and then lysed in situ with 200 μl of mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER, Pierce, Loughborough, UK) containing complete protease inhibitor tablets (Roche) for 30 min at room temperature. Protein levels in the lysates were assessed using a BCA assay (Pierce). Cell proteins (typically 30 μg protein per lane) were separated on 12.5%, 0.75 mm thick polyacrylamide SDS gels and electrophoretically transferred to 0.2 μm PVDF membranes (BioRad). The blots were probed with primary antibodies (1 : 1000, cell signaling) raised against AMPKα, phospho-AMPKα, Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (ACC), Phospho-acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (phospho-ACC) at room temperature for 3 h or HO-1 (1 : 200, Santa Cruz) at 4 °C overnight. Next, membranes were washed with PBS for 30 min prior to incubating with the appropriate anti-rabbit or anti-mouse horse radish peroxidise-conjugated secondary antibody (1 : 2000; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK) for 1 h at room temperature. Following this incubation, membranes were washed in PBS for 30 min and bands visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system and hyperfilm ECL (Merck, UK).

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean±S.E.M. Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by either the Dunnett's or Bonferroni post-test, as appropriate. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. CellEvent results were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-test. P<0.05 was considered to be significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Alzheimer's Society with support from The Henry Smith Charity and Alzheimer's Research. We are also most grateful to Dr K Nakatsu (Queen's University, Kingston, Canada) for the kind gift of QC-15.

Glossary

- Aβ

amyloid β peptide (Aβ)

- AD

Alzheimer's disease (AD),

- AMPK

AMP-dependent protein kinase (AMPK)

- CaMKKII

Ca2+/calmodulin kinase kinase II ()

- CoPPIX

cobalt protoporphyrin

- CORM-2

carbon monoxide releasing molecule

- DMEM

Dulbecco's minimum essential medium

- DTDP

dithiodipyridine (DTDP)

- HO-1

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)

- MTT

thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide

- PI

propidium iodide

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by M Verkhratsky

References

- 1Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease is a synaptic failure. Science 2002; 298: 789–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Coleman PD, Yao PJ. Synaptic slaughter in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003; 24: 1023–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Conforti L, Adalbert R, Coleman MP. Neuronal death: where does the end begin? Trends Neurosci 2007; 30: 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Jacobsen JS, Wu CC, Redwine JM, Comery TA, Arias R, Bowlby M et al. Early-onset behavioral and synaptic deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 5161–5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Culmsee C, Mattson MP. p53 in neuronal apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 331: 761–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6LeBlanc AC. The role of apoptotic pathways in Alzheimer's disease neurodegeneration and cell death. Curr Alzheimer Res 2005; 2: 389–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Bredesen DE, Rao RV, Mehlen P. Cell death in the nervous system. Nature 2006; 443: 796–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Culmsee C, Landshamer S. Molecular insights into mechanisms of the cell death program: role in the progression of neurodegenerative disorders. Curr Alzheimer Res 2006; 3: 269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Mehta SL, Manhas N, Raghubir R. Molecular targets in cerebral ischemia for developing novel therapeutics. Brain Res Rev 2007; 54: 34–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Kokmen E, Whisnant JP, O'Fallon WM, Chu CP, Beard CM. Dementia after ischemic stroke: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota (1960-1984). Neurology 1996; 46: 154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Desmond DW, Moroney JT, Sano M, Stern Y. Incidence of dementia after ischemic stroke: results of a longitudinal study. Stroke 2002; 33: 2254–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Peers C, Pearson HA, Boyle JP. Hypoxia and Alzheimer's disease. Essays in Biochemistry 2007; 43: 153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Yu SP, Canzoniero LM, Choi DW. Ion homeostasis and apoptosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2001; 13: 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Yu SP, Choi DW. Ions, cell volume, and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 9360–9362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Bortner CD, Hughes FMJr, Cidlowski JA. A primary role for K+ and Na+ efflux in the activation of apoptosis. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 32436–32442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Hughes FMJr, Bortner CD, Purdy GD, Cidlowski JA. Intracellular K+ suppresses the activation of apoptosis in lymphocytes. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 30567–30576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Bortner CD, Cidlowski JA. Cellular mechanisms for the repression of apoptosis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2002; 42: 259–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Yu SP. Regulation and critical role of potassium homeostasis in apoptosis. Prog Neurobiol 2003; 70: 363–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Yu SP, Yeh CH, Sensi SL, Gwag BJ, Canzoniero LM, Farhangrazi ZS et al. Mediation of neuronal apoptosis by enhancement of outward potassium current. Science 1997; 278: 114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Aizenman E, Stout AK, Hartnett KA, Dineley KE, McLaughlin B, Reynolds IJ. Induction of neuronal apoptosis by thiol oxidation: putative role of intracellular zinc release. J Neurochem 2000; 75: 1878–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Bossy-Wetzel E, Talantova MV, Lee WD, Scholzke MN, Harrop A, Mathews E et al. Crosstalk between nitric oxide and zinc pathways to neuronal cell death involving mitochondrial dysfunction and p38-activated K+ channels. Neuron 2004; 41: 351–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Pal S, Hartnett KA, Nerbonne JM, Levitan ES, Aizenman E. Mediation of neuronal apoptosis by Kv2.1-encoded potassium channels. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 4798–4802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Dallas ML, Boyle JP, Milligan CJ, Sayer R, Kerrigan TL, McKinstry C et al. Carbon monoxide protects against oxidant-induced apoptosis via inhibition of Kv2.1. FASEB J 2011; 25: 1519–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Pal SK, Takimoto K, Aizenman E, Levitan ES. Apoptotic surface delivery of K+ channels. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 661–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Thornton C, Bright NJ, Sastre M, Muckett PJ, Carling D. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a tau kinase, activated in response to amyloid beta-peptide exposure. Biochem J 2011; 434: 503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Yoon SO, Park DJ, Ryu JC, Ozer HG, Tep C, Shin YJ et al. JNK3 perpetuates metabolic stress induced by Abeta peptides. Neuron 2012; 75: 824–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Schipper HM. Heme oxygenase expression in human central nervous system disorders. Free Radic Biol Med 2004; 37: 1995–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Kim HP, Ryter SW, Choi AM. CO as a cellular signaling molecule. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2006; 46: 411–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Ryter SW, Alam J, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: from basic science to therapeutic applications. Physiol Rev 2006; 86: 583–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Wu L, Wang R. Carbon monoxide: endogenous production, physiological functions, and pharmacological applications. Pharmacol Rev 2005; 57: 585–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Dennery PA. Regulation and role of heme oxygenase in oxidative injury. Curr Top Cell Regul 2000; 36: 181–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Dwyer BE, Nishimura RN, Lu SY. Differential expression of heme oxygenase-1 in cultured cortical neurons and astrocytes determined by the aid of a new heme oxygenase antibody. Response to oxidative stress. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1995; 30: 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Pappolla MA, Chyan YJ, Omar RA, Hsiao K, Perry G, Smith MA et al. Evidence of oxidative stress and in vivo neurotoxicity of beta-amyloid in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease: a chronic oxidative paradigm for testing antioxidant therapies in vivo. Am J Pathol 1998; 152: 871–877. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Schipper HM, Cisse S, Stopa EG. Expression of heme oxygenase-1 in the senescent and Alzheimer-diseased brain. Ann Neurol 1995; 37: 758–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Schipper HM, Bennett DA, Liberman A, Bienias JL, Schneider JA, Kelly J et al. Glial heme oxygenase-1 expression in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging 2006; 27: 252–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Zeynalov E, Dore S. Low doses of carbon monoxide protect against experimental focal brain ischemia. Neurotox Res 2009; 15: 133–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37Al-Owais MM, Scragg JL, Dallas ML, Boycott HE, Warburton P, Chakrabarty A et al. Carbon monoxide mediates the anti-apoptotic effects of heme oxygenase-1 in medulloblastoma DAOY cells via K+ channel inhibition. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 24754–24764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38Lauren J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM. Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-beta oligomers. Nature 2009; 457: 1128–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39Rushworth JV, Griffiths HH, Watt NT, Hooper NM. Prion protein-mediated toxicity of amyloid-beta oligomers requires lipid rafts and the transmembrane LRP1. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 8935–8951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40Nicoll AJ, Panico S, Freir DB, Wright D, Terry C, Risse E et al. Amyloid-beta nanotubes are associated with prion protein-dependent synaptotoxicity. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41Murphy BJ, Laderoute KR, Short SM, Sutherland RM. The identification of heme oxygenase as a major hypoxic stress protein in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Br J Cancer 1991; 64: 69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42Lee PJ, Jiang BH, Chin BY, Iyer NV, Alam J, Semenza GL et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates transcriptional activation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 5375–5381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43Kinobe RT, Dercho RA, Nakatsu K. Inhibitors of the heme oxygenase - carbon monoxide system: on the doorstep of the clinic? Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2008; 86: 577–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44Redman PT, He K, Hartnett KA, Jefferson BS, Hu L, Rosenberg PA et al. Apoptotic surge of potassium currents is mediated by p38 phosphorylation of Kv2.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 3568–3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45Chen K, Gunter K, Maines MD. Neurons overexpressing heme oxygenase-1 resist oxidative stress-mediated cell death. J Neurochem 2000; 75: 304–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46Song W, Zukor H, Lin SH, Liberman A, Tavitian A, Mui J et al. Unregulated brain iron deposition in transgenic mice over-expressing HMOX1 in the astrocytic compartment. J Neurochem 2012; 123: 325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47Schipper HM, Song W, Zukor H, Hascalovici JR, Zeligman D. Heme oxygenase-1 and neurodegeneration: expanding frontiers of engagement. J Neurochem 2009; 110: 469–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48Schipper HM, Gupta A, Szarek WA. Suppression of glial HO-1 activity as a potential neurotherapeutic intervention in AD. Curr Alzheimer Res 2009; 6: 424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49Imuta N, Hori O, Kitao Y, Tabata Y, Yoshimoto T, Matsuyama T et al. Hypoxia-mediated induction of heme oxygenase type I and carbon monoxide release from astrocytes protects nearby cerebral neurons from hypoxia-mediated apoptosis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2007; 9: 543–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50Perera WS, Hooper NM. Ablation of the metal ion-induced endocytosis of the prion protein by disease-associated mutation of the octarepeat region. Curr Biol 2001; 11: 519–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51Um JW, Nygaard HB, Heiss JK, Kostylev MA, Stagi M, Vortmeyer A et al. Alzheimer amyloid-beta oligomer bound to postsynaptic prion protein activates Fyn to impair neurons. Nat Neurosci 2012; 15: 1227–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52Resenberger UK, Harmeier A, Woerner AC, Goodman JL, Muller V, Krishnan R et al. The cellular prion protein mediates neurotoxic signalling of beta-sheet-rich conformers independent of prion replication. EMBO J 2011; 30: 2057–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53Chen S, Yadav SP, Surewicz WK. Interaction between human prion protein and amyloid-beta (Abeta) oligomers: role OF N-terminal residues. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 26377–26383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54Correia SC, Moreira PI. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: a new hope to counteract neurodegeneration? J Neurochem 2010; 112: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55Yu SP, Farhangrazi ZS, Ying HS, Yeh CH, Choi DW. Enhancement of outward potassium current may participate in beta-amyloid peptide-induced cortical neuronal death. Neurobiol Dis 1998; 5: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56Colom LV, Diaz ME, Beers DR, Neely A, Xie WJ, Appel SH. Role of potassium channels in amyloid-induced cell death. J Neurochem 1998; 70: 1925–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57Mercer RC, Ma L, Watts JC, Strome R, Wohlgemuth S, Yang J et al. The prion protein modulates A-type K+ currents mediated by Kv4.2 complexes through dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-like protein 6. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 37241–37255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58Goodison WV, Frisardi V, Kehoe PG. Calcium channel blockers and Alzheimer's disease: potential relevance in treatment strategies of metabolic syndrome. J Alzheimers Dis 2012; 30: S269–S282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59Mairet-Coello G, Courchet J, Pieraut S, Courchet V, Maximov A, Polleux F. The CAMKK2-AMPK Kinase Pathway Mediates the Synaptotoxic Effects of Abeta Oligomers through Tau Phosphorylation. Neuron 2013; 78: 94–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60Motterlini R, Otterbein LE. The therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010; 9: 728–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61Watt NT, Taylor DR, Kerrigan TL, Griffiths HH, Rushworth JV, Whitehouse IJ et al. Prion protein facilitates uptake of zinc into neuronal cells. Nat Commun 2012; 3: 1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]