Abstract

We investigated the effects of troglitazone on human cervical cancer SiHa cells and its mechanisms of action. SiHa cells were incubated with different concentrations of troglitazone (100, 200, or 400 μg/mL) for 24, 48, and 72 hours. Cell viability was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay; cell cycle and apoptosis were detected by flow cytometry; and morphology of SiHa cells was observed under an inverted microscope. pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1-Skp2 plasmids were constructed and then transfected into SiHa cells. Protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting. Troglitazone inhibited the proliferation of SiHa cells in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. Troglitazone caused G0/1 phase arrest but failed to reduce apoptosis in SiHa cells. Troglitazone significantly increased expression of p27 but decreased Skp2 expression. Skp2 overexpression inhibited the role of troglitazone in increasing expression of p27, and the cell cycle inhibitory effect of troglitazone. Troglitazone can inhibit SiHa cell viability by affecting cell cycle distribution but not apoptosis, and Skp2 and p27 may play a critical role.

Keywords: SiHa cells, cell cycle, apoptosis

Introduction

Cervical cancer is ranked as the second leading cause of female cancer mortality worldwide and >500,000 new cases are diagnosed each year.1,2 Platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with radiotherapy or surgery is now mainly used but the efficacy is limited, especially in advanced-stage disease.3,4 Therefore, it is necessary to seek antitumor drugs of high efficacy and low toxicity for the treatment of cervical cancer. It has been confirmed that the vast majority of human tumors express peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ, including cervical cancer.5 The PPARγ agonist troglitazone (TGZ) exhibits potential antitumor effects. TGZ is one of the synthetic ligands, which exhibits the most potent drug effect and minimal side effects.6 TGZ inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation, which suggests that it has potential for treatment of cancer.7 However, the role of TGZ in cervical cancer and the precise molecular mechanisms of action have not been fully elucidated. It is necessary to investigate the antitumor mechanism of TGZ, in the hope of providing more therapeutic targets for cervical cancer. Therefore, we examined the effect of TGZ on human cervical cancer SiHa cells and made a preliminary determination of its molecular mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Reagents

TGZ was purchased from ALEXIS Biochemicals (Lausen, Switzerland) and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a final concentration of 0.1% in the culture medium. TGZ was stored at -80°C and further diluted to the appropriate concentrations with cell culture medium immediately before use. Anti-cyclin E, p27, Skp2, and GADPH antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA).

Cell culture

The human cervical cancer SiHa cell line was purchased from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), penicillin (100 U/mL; Sigma-Aldrich Co.), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich Co.) at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cells were treated with different amounts of TGZ as indicated (0, 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL).

MTT assay

Cells were seeded at 5×l03 cells/well in 96-well culture plates, and 24 hours later, they were treated with the indicated concentrations of TGZ. Control wells consisted of cells incubated with medium only. After 24, 48, and 72 hours’ treatment, cells were incubated with 20 μL 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) at 5 mg/mL. After 4 hours at 37°C, the supernatant was removed, and 150 μL DMSO was added. After the blue crystals were dissolved in DMSO, the optical density (OD) was detected at 570 nm using a 96-well multiscanner autoreader (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The following formula was used to determine the inhibition rate of cell proliferation:

| (1) |

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded at 2×105 cells/well in 6 cm Petri dishes and synchronized with DMEM containing 0.5% FBS for 12 hours. Cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of TGZ for 24, 48, and 72 hours. The SiHa cells were collected and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times and fixed with 75% ethanol at −20°C for at least 1 hour. After extensive washing with PBS, the cells were suspended in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution containing 50 mg/mL RNase A (Boehringer Mannheim) and 50 mg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich Co.), incubated for 1 hour at room temperature, and analyzed by FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

Apoptosis measurement

Apoptosis was analyzed 48 hours after treatment using the Annexin V–FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Cells were seeded at 1×l05 cells/well in 24-well culture plates. After 24, 48, and 72 hours, the cells were collected using 0.25% trypsin (without ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) and washed by PBS, and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Approximately 500 μL of binding buffer was added to each tube of cell suspension, followed by 5 μL annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate. Propidium iodide was added and flow cytometry (488 nm excitation and 530 nm emission) was performed to measure apoptosis.

Cell morphology

SiHa cells were seeded in six-well culture plates and incubated with TGZ for 24, 48, or 72 hours. SiHa cell morphology was examined using an inverted optical microscope.

Cell transfection

Cells (5×105) were plated on six-well plates 24 hours before transfection. The pcDNA3.1-Skp2 (Skp2 gene overexpressed) and pcDNA3.1 (plasmid vector) vector transfectants were constructed by Nanjing Keygen Biotech (People’s Republic of China) and used to transfect SiHa cells according to the instructions of the manufacturer of Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 4 mg DNA. Transfection media were removed 6 hours after transfection and replaced with fresh complete medium containing 10% FBS. Controls included cells treated with Lipofectamine 2000 and cells transfected with empty vector pcDNA3.1.

Western blotting

After different treatments, the medium was aspirated and SiHa cells were lysed with ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid method. After adjustment to a similar level of total protein concentration, samples were separated by 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20, pH 8.0) for 1 hour at room temperature prior to incubation with specific antibodies to cyclin E, p27, Skp2, and GADPH overnight at 4°C. After washing and reaction with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Beijing Zhong Shan Golden Bridge Biological Technology Co. Ltd., Beijing, People’s Republic of China), or anti-rabbit IgG (Beyotime, People’s Republic of China) secondary antibodies for 1 hour, the membranes were washed with TBST buffer three times and the proteins on the membrane were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Beyotime).

Statistics

Studies were performed in triplicate with the results expressed as the mean ± standard deviation as appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For comparison of differences, Student’s t-test or analysis of variance was used. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

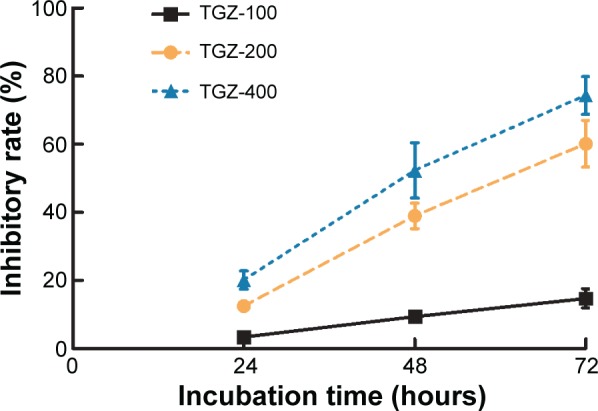

TGZ inhibited proliferation of SiHa cells

TGZ at a concentration of 200 and 400 μg/mL significantly inhibited SiHa cell viability after 24 hours (P<0.05) in comparison with the control group (without TGZ). At 48 and 72 hours, the cell inhibition rate was increased significantly (P<0.05) in the three TGZ groups compared with the control group. TGZ inhibited SiHa cell growth in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Table 1; Figure 1).

Table 1.

The inhibitory effects of troglitazone on the proliferation of human cervical cancer SiHa cells

| Troglitazone (μg/mL) | Time (h)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 48 | 72 | |

| 100 | 3.34±0.27 | 9.37±1.54* | 14.73±2.77* |

| 200 | 12.42±1.10* | 38.95±3.76* | 60.15±6.87* |

| 400 | 20.11±2.68* | 52.33±8.15* | 74.36±5.55* |

Note: Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

P<0.05.

Figure 1.

Troglitazone (TGZ) inhibits proliferation of human cervical cancer SiHa cells.

Notes: Cells were treated with TGZ (100, 200, or 400 μg/mL) and proliferation was measured after 24, 48, or 72 hours. TGZ significantly inhibited SiHa cell proliferation in a time- and concentration-dependent manner.

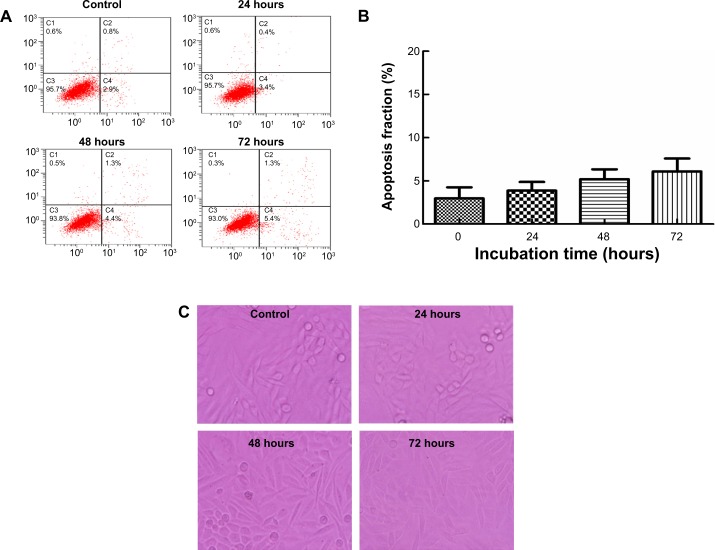

Effect of TGZ on SiHa cell apoptosis

The apoptosis rate for SiHa cells was 2.97% (0 hours), 3.87% (24 hours), 5.20% (48 hours), and 6.10% (72 hours) after treatment with 400 μg/mL TGZ, without significant differences at each time point (P=0.06) (Figure 2A and B). These results were consistent with the cell morphology (Figure 2C). Treatment of SiHa cells with 400 μg/mL TGZ for 24, 48, or 72 hours resulted in decreased cell numbers, but no significant changes in cell morphology were observed in each group. Scattered polynuclear apoptotic cells were observed, as were apoptotic bodies. No significant differences were observed for the varying durations of incubation.

Figure 2.

Effect of troglitazone (TGZ) on SiHa cell apoptosis.

Notes: SiHa cells were treated with TGZ (400 μg/mL) for 24, 48, and 72 hours. (A) Axis labels show the apoptosis rate of SiHa cells. Flow cytometric analysis of TGZ-induced apoptosis in SiHa cells using annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate/propidium iodide staining. Cells in the lower right quadrant represent early apoptotic cells, and those in the upper right quadrant represent late apoptotic cells. Apoptosis rate = early apoptotic cells + late apoptotic cells. (B) The percentage of apoptotic cells is presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The data are representative of three similar experiments. The apoptosis rate for SiHa cells was 2.97%±1.29% (0 hours), 3.87%±1.0% (24 hours), 5.20%±1.14% (48 hours), and 6.10%±1.49% (72 hours) after treatment with 400 μg/mL TGZ, without significant differences at each time point (P=0.06). (C) Cell morphology was observed in each time group using an inverted optical microscope (200×). Scattered polynuclear apoptotic cells were observed. No significant differences were observed for the varying lengths of incubation.

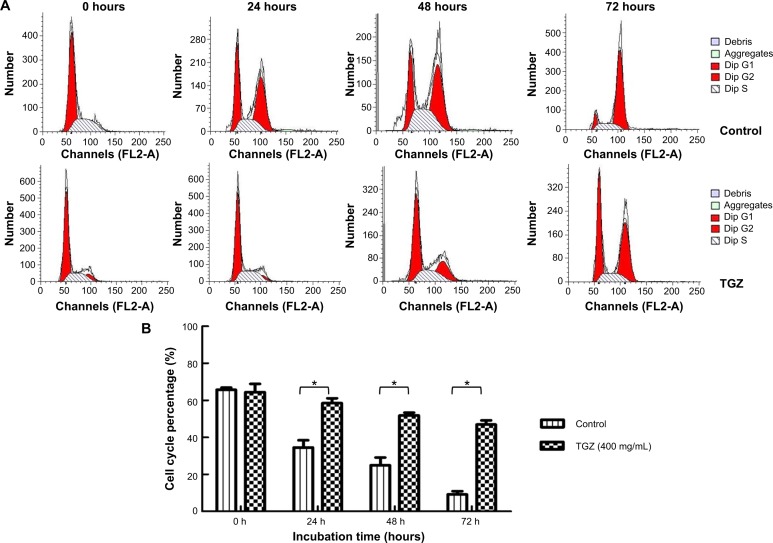

TGZ induced SiHa cell cycle arrest

SiHa cells were synchronized. The mean proportion of cells in G0/1 phase was 65.73%, 34.50 %, 24.98%, and 9.17% in the control group at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours, respectively, compared with 64.47%, 58.53%, 51.87%, and 46.95% after treatment with 400 mg/mL TGZ, which was significantly different (P<0.01). Cells in G2/M and S phases decreased with increasing incubation time, suggesting that TGZ inhibited cell proliferation by inducing G0/1 arrest and G1-S phase transitional inhibition (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Troglitazone (TGZ) induces cell cycle arrest at the G0/1 phase in SiHa cells.

Notes: (A) The cell cycle distribution of treated cells was determined using flow cytometry. (B) The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3), with results representative of three independent experiments shown. The percentage of cells in G0/1 phase was 65.73%, 34.50%, 24.98%, and 9.17% in the control group at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours, respectively, compared with 64.47%, 58.53%, 51.87%, and 46.95% after treatment with 400 mg/mL TGZ, which was significantly different (*P<0.01).

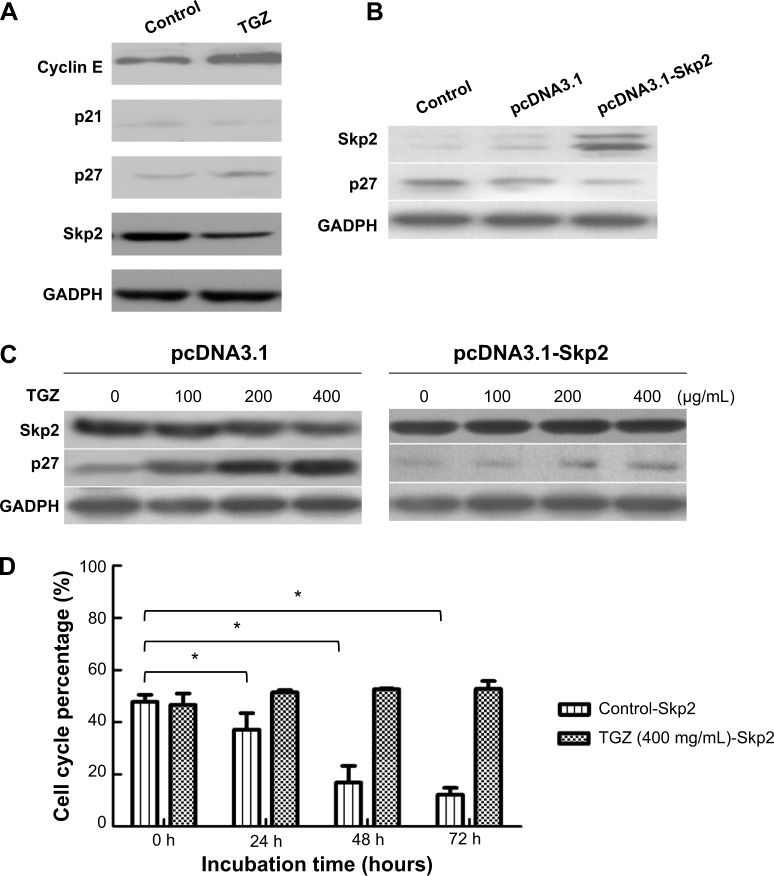

Skp2 was involved in p27 upregulation and cell cycle arrest induced by TGZ

TGZ inhibited cell proliferation in SiHa cells by affecting cell cycle distribution. We measured the expression of proteins related to G1/S transition, such as p21, p27, and cyclin E after treatment with 400 μg/mL TGZ for 24 hours. p21 was only weakly expressed in SiHa cells and slightly increased with the TGZ incubation. Treatment with 400 μg/mL TGZ for 24 hours significantly increased expression of p27. Expression of cyclin E increased after TGZ incubation (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Skp2 is involved in p27 upregulation and cell cycle arrest induced by troglitazone (TGZ) in SiHa cells.

Notes: (A) Western blot analysis of protein extracts from SiHa cells treated with TGZ for 24 hours. Expression of p21, p27, and cyclin E was analyzed. GADPH was used as a loading control. (B) pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1-Skp2 were transfected into SiHa cells. Expression of p27 and Skp2 was analyzed. GADPH was used as a loading control. (C) SiHa cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 or pcDNA3.1-Skp2 and incubated with 0, 100, 200, or 400 μg/mL TGZ. Expression of p27 protein was detected. (D) The proportion of pcDNA3.1-Skp2-SiHa cells in G0/1 phase was 47.76% (0 hours), 37.21% (24 hours), 16.90% (48 hours), and 12.23% (72 hours), which was significantly different. *P<0.05. Skp2-overexpressing SiHa cells were incubated with 400 mg/mL TGZ. G0/1 phase distribution of treated cells was 48.76% (0 hours), 52.16% (24 hours), 52.52% (48 hours), and 53.30% (72 hours), which was not significantly different. Control-Skp2 represents the SiHa cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-Skp2 and incubated without TG2, and TG2-Skp2 represents the cells that transfected with pcDNA3.1-Skp2 and incubated with TG2.

pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1-Skp2 were transfected into SiHa cells to clarify the role of p27 and Skp2 in the cell cycle modulation of TGZ. Overexpression of Skp2 significantly reduced p27 expression compared with the blank control and vector group (Figure 4B). After transfection with pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1-Skp2, SiHa cells were incubated with TGZ. TGZ significantly increased p27 expression in pcDNA3.1-SiHa cells but decreased Skp2 expression. Upregulation of p27 disappeared in pcDNA3.1-Skp2-SiHa cells (Figure 4C). Cell cycle distribution of the SiHa cells was determined using flow cytometry. The proportion of pcDNA3.1-Skp2-SiHa cells in G0/1 phase was 47.76% (0 hours), 37.21% (24 hours), 16.90% (48 hours), and 12.23% (72 hours), which was significantly different. Skp2-overexpressing (pcDNA3.1-Skp2) SiHa cells were incubated with 400 μg/mL TGZ. The proportion of pcDNA3.1-Skp2-SiHa cells incubated with TGZ (400 μg/mL) in G0/1 phase was 48.76% (0 hours), 52.16% (24 hours), 52.52% (48 hours), and 53.30% (72 hours), which was not significantly different (Figure 4D).

Discussion

PPARs are a class of ligand-activated nuclear transcription factors that belong to the nuclear receptor superfamily type II. The biological functions of PPARs are complex, including lipid and glucose metabolism, inflammation, and tumor cell differentiation and apoptosis. Currently, three types of PPARs have been identified: PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ. PPARγ and its agonist are the most widely studied. Thiazolidinedione ketone compounds, such as TGZ, are synthetic PPARγ agonists that were initially used as insulin sensitizers in diabetes research. Later, it was observed that, in addition to regulating glucose and lipid metabolism, TGZ exhibited anti-atherosclerotic and anti-inflammatory effects, as well as glucose-inhibitory effects and other broad effects on biological activity.8–10 Significant data have shown that PPARγ agonists exhibit antitumor effects on a variety of tumors.11,12 Our study revealed that TGZ has a significant time- and dose-dependent inhibitory effect on human cervical cancer cell proliferation, which shows an antitumor effect. TGZ showed an antiproliferative effect in our study, which was consistent with previous research on gastric cancer, breast cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma.13–15

Biological behavior of malignant tumor includes disorderly proliferation and distant metastasis, and the proliferation ability is related to disruption of the cell cycle and apoptosis resistance. We analyzed apoptosis through annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate staining by flow cytometry and observed that different concentrations of TGZ did not alter the percentage of apoptotic cells, suggesting that apoptosis does not play an important role in the inhibitory effect of TGZ on human cervical cancer SiHa cell growth. We further analyzed the cell cycle distribution and observed that after treatment with 400 μg/mL TGZ, the proportion of SiHa cells in G0/G1 phase significantly increased, whereas the S and G2 phase proportions significantly decreased. The effect appeared to be significantly time dependent, suggesting that the effect of TGZ may lead to cell cycle arrest in G0/1 phase. This is believed to be the first study to show that TGZ inhibits the proliferation of human cervical cancer SiHa cells through regulating the cell cycle but not apoptosis. Our results differ from those of Chen et al in human cervical cancer HeLa cells.16 They demonstrated that TGZ induces apoptosis, which is closely related to p53 ubiquitin and the presence of the TGZ-PPARγ-p53 signaling pathway, and is a critical regulator of apoptosis. Differences in histopathology and genomics between human cervical cancer cell lines may result in different biological behavior. As we know, SiHa cells are squamous cells while Hela cells are adenocarcinoma cells. The effect of p53 gene may differ in different pathological cells.17–20 Further research should be conducted to clarify gene expression and the signaling pathway. These studies suggest that TGZ inhibits cell proliferation in different tumors, but there may be differences in the mechanisms and pathways involved.

The cell cycle is divided into G1, S, G2, and M phases, which are regulated by cell cycle proteins cyclin, cyclin- dependent kinase (CDK), and CDK inhibitor. In our study, TGZ significantly increased expression of p27 in cells in a dose-dependent manner. p27 is a broad-spectrum CDK inhibitor that can play a key role in G1/S transition and can promote the proliferation of a variety of tumors with its abnormal expression.6 p27 expression is reduced in human cervical cancer tissue and is related to prognosis.21 As the level of p27 mRNA remains relatively constant, the regulation of p27 protein levels typically occurs at the level of protein degradation. p27 protein activity, degradation, and phosphorylation are related to ubiquitination-dependent degradation.12 Skp2 is an important factor in p27 ubiquitination and degradation.22,23 In a variety of tumors, Skp2 expression is upregulated and related to poor prognosis, thereby reducing p27 levels and inhibition of cell proliferation.6,24–27 Our results showed that the expression of Skp2 and p27 was negatively correlated, and TGZ may primarily act by inhibiting Skp2 expression and thereby enhancing p27 protein expression. Motomura et al reported that Skp2 and p27 may be involved in the cell cycle arrest caused by TGZ in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 and HLF cell lines. This pathway is associated with cell proliferation and differentiation.28,29 We found that when Skp2 was overexpressed in SiHa cells, the effect of TGZ on p27 protein expression was offset significantly, which confirms that Skp2 and p27 are involved in cell cycle arrest after TGZ incubation. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3 is involved in the development and progression of many different tumor types, including cervical adenocarcinoma.30 In addition, the activation of STAT3 has a functional role in HPV16-mediated cervical carcinogenesis. A recent study demonstrated that the activation of PPARγ has a suppressive effect on STAT3. PPARγ agonists negatively modulate STAT3 through direct and/or indirect mechanisms in cancer cells. In addition, STAT3 is known to be involved in the development and progression of many tumors, including cervical adenocarcinoma. The activation of STAT3 has a functional role in HPV16-mediated cervical carcinogenesis. Interestingly, a recent paper demonstrated that the activation of PPARγ has a suppressive activity on STAT3. In fact, PPARγ agonists negatively modulate STAT3 through direct and/or indirect mechanisms in cancer cells, and it could also be one of the mechanisms of TGZ.30–33 However, more in-depth studies are needed to identify its mechanism of action in the future.

In summary, our results indicate that TGZ inhibits SiHa cell viability through affecting cell cycle distribution but not apoptosis, and Skp2 and p27 may play a critical role in this process.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- 1.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Gilbert ES, et al. Second cancers among 104,760 survivors of cervical cancer: evaluation of long-term risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(21):1634–1643. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu X, Schwarz JK, Lewis JS, Jr, et al. A microRNA expression signature for cervical cancer prognosis. Cancer Res. 2010;70(4):1441–1448. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yee GP, de Souza P, Khachigian LM. Current and potential treatments for cervical cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013;13(2):205–220. doi: 10.2174/1568009611313020009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao A, Lin CT, Lai CH. Updates in systemic treatment for metastatic cervical cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2014;15(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11864-013-0273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An Z, Muthusami S, Yu JR, Park WY. T0070907, a PPAR γ inhibitor, induced G2/M arrest enhances the effect of radiation in human cervical cancer cells through mitotic catastrophe. Reprod Sci. 2014;21(11):1352–1361. doi: 10.1177/1933719114525265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahmoud MF, El Shazly SM. Pioglitazone protects against cisplatin induced nephrotoxicity in rats and potentiates its anticancer activity against human renal adenocarcinoma cell lines. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;51:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li MY, Deng H, Zhao JM, Dai D, Tan XY. PPARgamma pathway activation results in apoptosis and COX-2 inhibition in HepG2 cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(6):1220–1226. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i6.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugawara A, Uruno A, Kudo M, Matsuda K, Yang CW, Ito S. Effects of PPARγ on hypertension, atherosclerosis, and chronic kidney disease. Endocr J. 2010;57(10):847–852. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k10e-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin H. Role of PPAR-gamma in inflammation. Prospects for therapeutic intervention by food components. Mutat Res. 2010;690(1–2):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbas A, Blandon J, Rude J, Elfar A, Mukherjee D. PPAR- γ agonist in treatment of diabetes: cardiovascular safety considerations. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2012;10(2):124–134. doi: 10.2174/187152512800388948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tseng CH, Tseng FH. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists and bladder cancer: lessons from animal studies. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev. 2012;30(4):368–402. doi: 10.1080/10590501.2012.735519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotta-Loizou I, Giaginis C, Theocharis S. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in breast cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12(9):1025–1044. doi: 10.2174/187152012803529664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C, Wang J, Bai P. Troglitazone induces apoptosis in gastric cancer cells through the NAG-1 pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2011;4(1):93–97. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2010.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu HN, Lee YR, Noh EM, et al. Induction of G1 phase arrest and apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells by troglitazone, a synthetic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) ligand. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32(8):906–912. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou YM, Wen YH, Kang XY, Qian HH, Yang JM, Yin ZF. Troglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligand, induces growth inhibition and apoptosis of HepG2 human liver cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(14):2168–2173. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen HM, Zhang DG, Wu JX, Pei DS, Zheng JN. Ubiquitination of p53 is involved in troglitazone induced apoptosis in cervical cancer cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(5):2313–2318. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.5.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teruszkin Balassiano I, Alves De Paulo S, Henriques Silva N, Curié Cabral M, da Gloria da Costa Carvalho M. Metastatic potential of MDA435 and Hep2 cell lines in chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model. Oncol Rep. 2001;8(2):431–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osman I, Scher HI, Zhang ZF, et al. Alterations affecting the p53 control pathway in bilharzial-related bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3(4):531–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imadome K, Iwakawa M, Nakawatari M, et al. Subtypes of cervical adenosquamous carcinomas classified by EpCAM expression related to radiosensitivity. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10(10):1019–1026. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.10.13249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tornesello ML, Buonaguro L, Buonaguro FM. Mutations of the TP53 gene in adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(3):442–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouda J, Hes O, Koprivova M, Pesek M, Svoboda T, Boudova L. P27 as a prognostic factor of early cervical carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(1):164–169. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318277edc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi M, Liu D, Zhang S, Hu P, Sang T. Inhibition of S-phase kinase-associated protein 2-mediated p27 degradation suppresses tumorigenesis and the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Med Rep. 2015 Jan 8; doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3156. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haque I, Banerjee S, De A, et al. CCN5/WISP-2 promotes growth arrest of triple-negative breast cancer cells through accumulation and trafficking of p27 via Skp2 and FOXO3a regulation. Oncogene. 2014 Aug 18; doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.250. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bloom J, Pagano M. Deregulated degradation of the cdk inhibitor p27 and malignant transformation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2003;13(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu H, Cao X, Zhang H, et al. Imbalance between MMP-2, 9 and TIMP-1 promote the invasion and metastasis of renal cell carcinoma via SKP2 signaling pathways. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(10):9807–9813. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Wang H, Ma J, et al. The expression and prognosis of Emi1 and Skp2 in breast carcinoma: associated with PI3K/Akt pathway and cell proliferation. Med Oncol. 2013;30(4):735. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu L, Grigoryan AV, Li Y, Hao B, Pagano M, Cardozo TJ. Specific small molecule inhibitors of Skp2-mediated p27 degradation. Chem Biol. 2012;19(12):1515–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okada M, Sakai T, Nakamura T, et al. Skp2 promotes adipocyte differentiation via a p27Kip1-independent mechanism in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379(2):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motomura W, Takahashi N, Nagamine M, et al. Growth arrest by troglitazone is mediated by p27Kip1 accumulation, which results from dual inhibition of proteasome activity and Skp2 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(1):41–46. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang P, Li H, Yang B, et al. Biological significance and therapeutic implication of resveratrol-inhibited Wnt, Notch and STAT3 signaling in cervical cancer cells. Genes Cancer. 2014;5(5–6):154–164. doi: 10.18632/genesandcancer.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shukla S, Mahata S, Shishodia G, et al. Functional regulatory role of STAT3 in HPV16-mediated cervical carcinogenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vitale G, Zappavigna S, Marra M, et al. The PPAR-γ agonist troglitazone antagonizes survival pathways induced by STAT-3 in recombinant interferon-β treated pancreatic cancer cells. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30(1):169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dicitore A, Caraglia M, Gaudenzi G, et al. Type I interferon-mediated pathway interacts with peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ): at the cross-road of pancreatic cancer cell proliferation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1845(1):42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]