Abstract

Endometrial hyperplasia is a precursor to the most common gynecologic cancer diagnosed in women. Apart from estrogenic induction, aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signal is well known to correlate with endometrial hyperplasia and its carcinoma. The benzopyran compound 2-(piperidinoethoxyphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2H-benzo (b) pyran(K-1), a potent antiestrogenic agent, has been shown to have apoptosis-inducing activity in rat uterine hyperplasia. The current study was undertaken to explore the effect of the benzopyran compound K-1 on growth and Wnt signaling in human endometrial hyperplasial cells. Primary culture of atypical endometrial hyperplasial cells was characterized by the epithelial cell marker cytokeratin-7. Results revealed that compound K-1 reduced the viability of primary endometrial hyperplasial cells and expression of ERα, PR, PCNA, Wnt7a, FZD6, pGsk3β and β-catenin without affecting the growth of the primary culture of normal endometrial cells. The β-catenin target genes CyclinD1 and c-myc were also found to be reduced, whereas the expression of axin2 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitor Dkk-1 was found to be upregulated, which caused the reduced interaction of Wnt7a and FZD6. Nuclear accumulation of β-catenin was found to be decreased by compound K-1. K-1 also suppressed the pPI3K/pAkt survival pathway and induced the cleavage of caspases and PARP, thus subsequently causing the apoptosis of endometrial hyperplasial cells. In conclusion, compound K-1 suppressed the growth of human primary endometrial hyperplasial cells through discontinued Wnt/β-catenin signaling and induced apoptosis via inhibiting the PI3K/Akt survival pathway.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is known to have a prominent role in a number of developmental processes,1 differentiation and proliferation,2 survival and adhesion3 as well as the regulation of menstrual cycle.4 In the endometrium, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is under the control of finely tuned hormonal equilibrium, for example, estrogen induces the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin during the proliferative phase, which is later decreased during the secretary phase by progesterone, in the menstrual cycle.5, 6 Aberrant regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway results in neoplastic transformation and thus lays at the root of initiation and progression of many malignancies.7, 8 Moreover, nuclear β-catenin staining has been found to be prominent in the early onset of endometrial cancer, endometrial hyperplasia and well-differentiated endometriod carcinomas.9, 10

Unopposed estrogen action induces proliferative disorders and changes in the tissue structure of uterus, culminating into atypical hyperplasia and subsequently, the endometrial carcinogenesis.11, 12 The regression of hyperplastic to normal endometrium is the main purpose of any conservative treatment in order to prevent the development of adenocarcinoma. Currently, as a mode of treatment for hyperplasia, cyclical progestin therapy is recommended, whereas in patients with cellular atypia, hysterectomy is recommended. However, neither progestin treatment, the major hormonal therapy for endometrial cancer, nor cytotoxic chemotherapy showed substantial benefits for the treatment of endometrial hyperplasia. Therefore, future research activities must evaluate new compounds and treatment strategies.

In our prior studies, it has been demonstrated that benzopyrans are the class of potent antiestrogenic compounds13, 14 that showed antiproliferative and apoptotic activity in rat endometrial hyperplasia15 and in human endometrial cancer cells.16, 17 However, the complete mechanism of action of 2-(piperidinoethoxyphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2H-benzo(b)pyran (K-1), responsible for inhibition of endometrial hyperplasia, remains to be explored in human endometrial hyperplasial cells. Because estrogen is one of the factor responsible for inducing Wnt/β-catenin signaling that may be responsible for inducing proliferation and hyperplasia formation in endometrium,4, 5 we further analyzed whether the benzopyran compound (K-1) modulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in human endometrial hyperplasial cells from proliferation (Wnt-On) to differentiation (Wnt-Off). Accordingly, in the current study, we explored the antiproliferative efficacy of K-1 on primary culture cells derived from human endometrial hyperplasial tissue and investigated the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and its downstream signaling. We have also studied the effect of K-1 on cell survival pathway to substantiate the above conjecture.

Results

K-1 inhibits endometrial hyperplasial cell proliferation

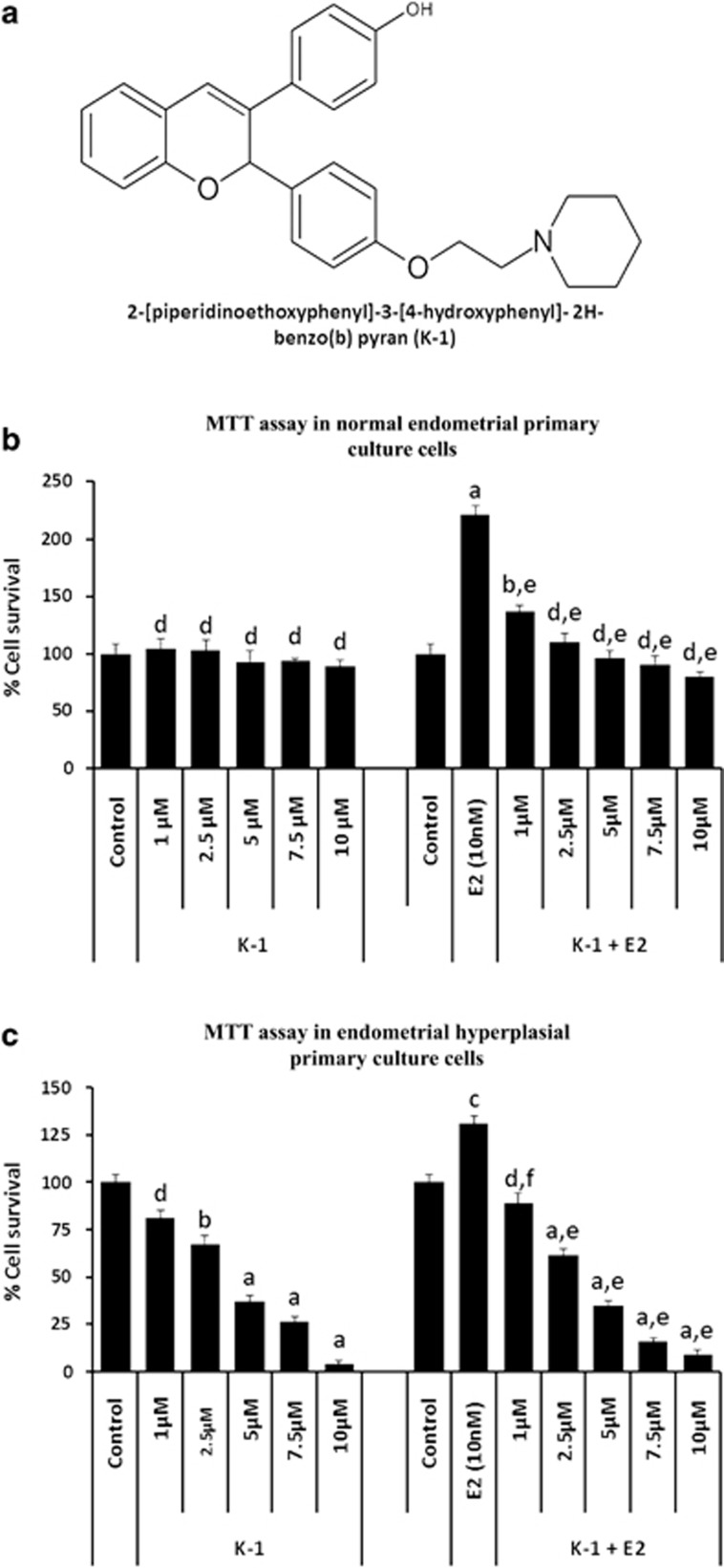

Firstly, the effect of K-1 on cell viability was examined by 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Treatment of primary endometrial hyperplasial cells with K-1 showed decreased cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner with IC50 of ∼5 μM (P<0.001), in the absence or presence of estradiol (Figure 1c). K-1 was ineffective in normal endometrial primary culture cells but suppressed the estradiol-induced proliferation in normal endometrial cells (Figure 1b). This showed that K-1 has an antiproliferative effect on primary endometrial hyperplasial cells without affecting the normal endometrial cells.

Figure 1.

K-1 (2-[piperidinoethoxyphenyl]-3-[4-hydroxyphenyl]- 2H-benzo(b) pyran) inhibits endometrial hyperplasial cell proliferation. (a) Chemical structure of compound K-1, (b and c) cellular growth pattern of normal primary endometrial cells and primary endometrial hyperplasial cells. Cells were treated with various concentrations of compound K-1 (1, 2.5, 5, 7.5 and 10 μM) in the absence or presence of estradiol (10 nM) for 48 h. Cell viability was measured using MTT assay. The percentage of viable cells was calculated as the ratio of treated cells to the control cells. Data are expressed as mean (of three different experiments on normal samples and five different experiments on hyperplasial samples);±S.E.M., P values are a-P<0.001, b-P<0.01, c-P<0.05 and d-P>0.05 versus control and e-P<0.001, f-P<0.01, g-P<0.05 and h-P>0.05 versus estradiol

K-1 alters the expression of proliferation markers and Wnt/β-catenin signaling markers in primary endometrial hyperplasial cells

To study the proliferation and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, we analyzed proliferation markers (ERα, PR), downstream targets and integral parts of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Wnt7a, FZD6, pGsk3β, Gsk3β and axin2). K-1 was shown to downregulate the expression of ERα, PR, Wnt7a and FZD6 whereas upregulate the expression of axin2 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2a). The densitometric analysis revealed that K-1 reduced the expression of ERα by∼76%, PR by ∼86%, Wnt7a by ∼77%, FZD6 by ∼55% and upregulated the expression of axin2 by 1.7 times at a concentration of 7.5 μM. Gsk3β, an important downstream mediator of Wnt signaling that regulates β-catenin phosphorylation and ubiqutinization, was found to be activated by K-1 via its dephosphorylation (P<0.001). These data suggest that K-1 significantly downregulates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling in hyperplasial cells.

Figure 2.

Effect of compound K-1 on the expression of (a) proliferation markers and Wnt/β-catenin signaling markers, and (b) its downstream effectors. Endometrial hyperplasial cells were treated with vehicle or compound K-1 at various concentrations (2.5, 5 and 7.5 μM) for 48 h. Thirty-five micrograms of whole cell lysate protein in each lane was probed for the expression of ERα, PR, Wnt7a, FZD6, axin2, pGsk3β(ser9), Gsk3β, β-catenin, CyclinD1, c-myc and PCNA using specific antibodies. β-actin was used as a control to correct for loading. Representative blots are shown (upper panels) and densitometric quantitation of protein expression levels are shown as fold changes (lower panels). Data are expressed as mean of three different experiments;±S.E.M., P values are a-P<0.001, b-P<0.01, c-P<0.05 and d-P>0.05 versus control

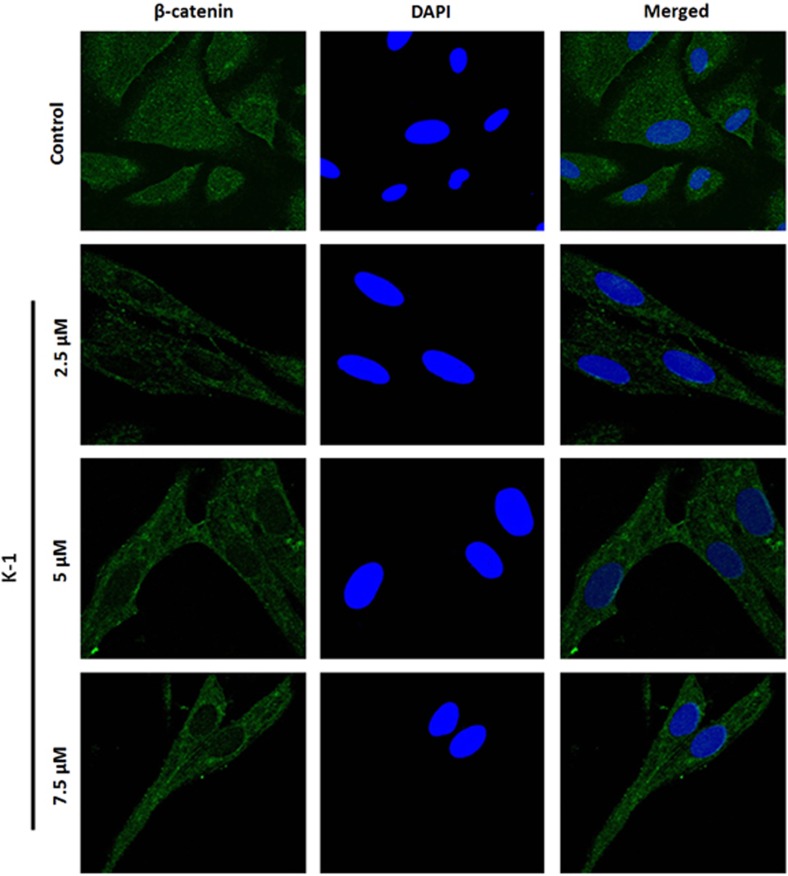

K-1 downregulates the expression of β-catenin and its nuclear localization

K-1 was found to reduce the expression of β-catenin and its downstream regulators (Figure 2b). The densitometric analysis showed that K-1 reduced the expression of β-catenin by ∼65%, CyclinD1 by ∼75%, c-myc by ∼70% and PCNA by ∼81% at a concentration of 7.5 μM. Simultaneously, K-1 also reduced the nuclear localization of β-catenin (Figure 3), which might also be responsible for suppression of β-catenin activation.

Figure 3.

Demonstration of nuclear β-catenin accumulation in primary endometrial hyperplasial cells by confocal microscopy. Cells were treated with vehicle, 2.5, 5 and 7.5 μM of the compound K-1 for 24 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, incubated with β-catenin antibody overnight, and subsequently incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody for 2 h. The preparations were washed and counterstained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Representative micrographs demonstrating the distribution of β-catenin are shown. Cell images were grasped using a confocal fluorescence microscope

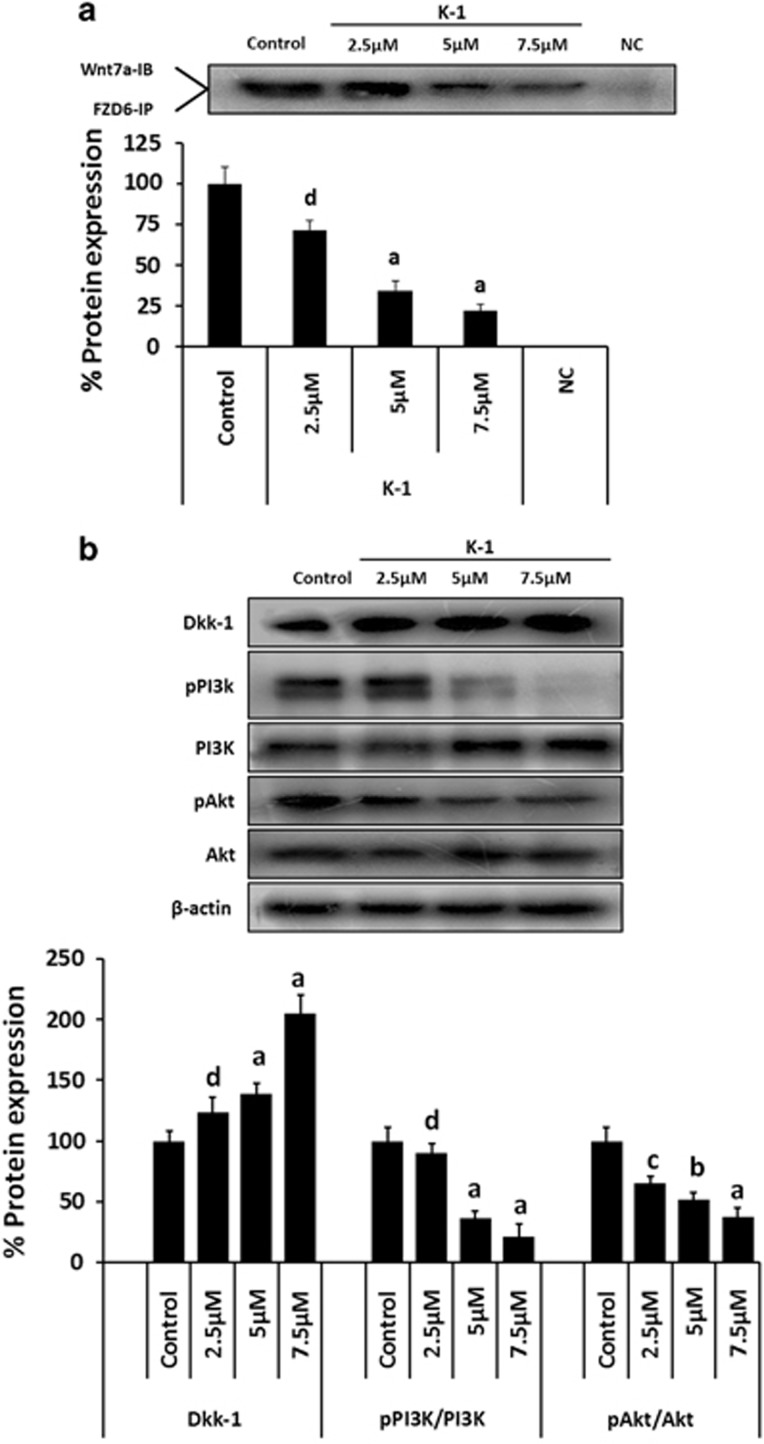

Effect of K-1 on Wnt/FZD6 binding and Dkk-1 expression

Co-immunoprecipitation studies were performed to analyze whether K-1 inhibits Wnt7a and FZD6 interaction and modulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Results indicated that K-1 decreased the interaction of Wnt7a/ FZD6 complex in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4a). The densitometric analysis showed ∼78% reduction in Wnt7a/FZD6 binding by K-1, which might be responsible for the deactivation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Figure 4.

Effect of K-1 on Wnt/FZD6 binding, Dkk-1 expression and markers of cell survival pathway in endometrial hyperplasial cells. (a) Interaction between Wnt7a ligand and FZD6 was determined by co-immunoprecipitation. Cells were treated with vehicle or compound at various concentrations, for 48 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FZD6 and subsequently immunoblotted with anti-Wnt7a. NC is the negative control in which cell lysate was incubated with non-immune serum instead of anti-FZD6. Representative blots are shown in the upper panel and densitometric quantitation of protein expression levels are shown as fold changes. Data are expressed as mean of three different experiments;±S.E.M., P values are a-P<0.001, b-P<0.01, c-P<0.05 and d-P>0.05 versus control. (b) Phosphorylation status of PI3K, Akt and expression of Dkk-1 as determined by western blot analysis in endometrial hyperplasial cells. Cells were treated with vehicle, 2.5, 5 and 7.5 μM of the compound for 48 h. Thirty-five micrograms of whole cell lysate protein in each lane was probed for the expression of pPI3K(tyr485), PI3K, pAkt(ser473), Akt and Dkk-1 using specific antibodies. β-actin was used as a control to correct for loading. Representative blots are shown in the upper panel and densitometric quantitation of protein expression levels are shown as fold changes. Data are expressed as mean of three different experiments;±S.E.M., P values are a-P<0.001, b-P<0.01, c-P<0.05 and d-P>0.05 versus control

Further, the expression of Dkk-1, a well-proven inhibitor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, was found to be upregulated (1.8-fold) by K-1 (Figure 4b).

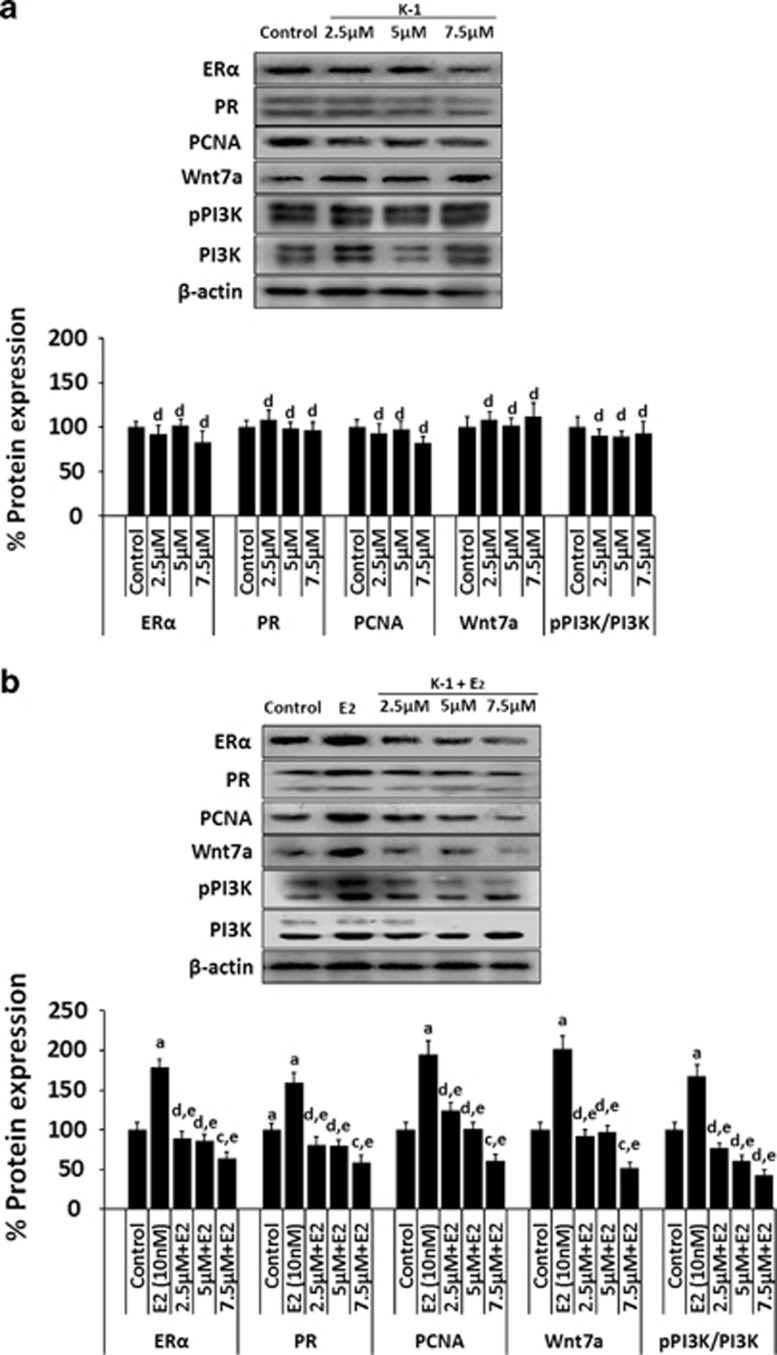

K-1 suppresses the estradiol-induced proliferation markers in normal endometrial cells

To analyze whether K-1 acts through estrogen-mediated signaling to interfere with Wnt signaling, the effect of K-1 on estradiol-induced expression of ERα, PR, PCNA, Wnt7a, pPI3K and PI3K biomarkers in normal endometrial cells were studied. The densitometric analysis showed that K-1 significantly reduced the estradiol-induced expression of ERα by ∼37%, PR by ∼42%, PCNA by ∼39%, Wnt7a by ∼49% and pPI3K/PI3K by ∼58% at a concentration of 7.5 μM (Figure 5b). Interestingly, K-1 did not cause any effect on the above-mentioned biomarkers in normal endometrial cells when incubated with K-1 alone (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

K-1 suppresses estradiol-induced proliferation markers and Wnt7a. Western blot analysis was done to see the effect of compound K-1 on primary culture of normal endometrial cells (a) in the absence of estradiol and (b) in the presence of estradiol. The expression of proliferation markers (ERα, PR and PCNA), Wnt7a and cell survival marker (pPI3K-tyr485/PI3K) was analyzed in the presence of estradiol (10 nM). Cells were treated with vehicle or E2, K-1, K-1+E2, for 48 h. Thirty-five micrograms of whole cell lysate protein in each lane was probed for the expression of ERα, PR, PCNA.Wnt7a, pPI3K(tyr485) and PI3K using specific antibodies. β-actin (upper panel) was used as a control to correct for loading. Representative blots are shown and densitometric quantitation of protein expression levels are shown as fold changes (lower panel). Data are expressed as mean of three different experiments;±S.E.M., P values are a-P<0.001, b-P<0.01, c-P<0.05 and d-P>0.05 versus control and e-P<0.001, f-P<0.01, g-P<0.05 and h-P>0.05 versus estradiol

K1 interferes with the PI3K/Akt survival pathway in endometrial hyperplasial cells

We also studied the effect of K-1 on the PI3K/Akt pathway, an important cell survival and proliferation pathway in hyperplasia development. Phosphorylation status of PI3K (at tyr485) and Akt (at ser473) was significantly downregulated by K-1. The densitometric analysis of immunoblots showed that the K-1 decreased the intracellular levels of phosphorylated PI3K by ∼80% which in turn decreased the activation of Akt by ∼65% at a concentration of 7.5 μM of K-1 (Figure 4b).

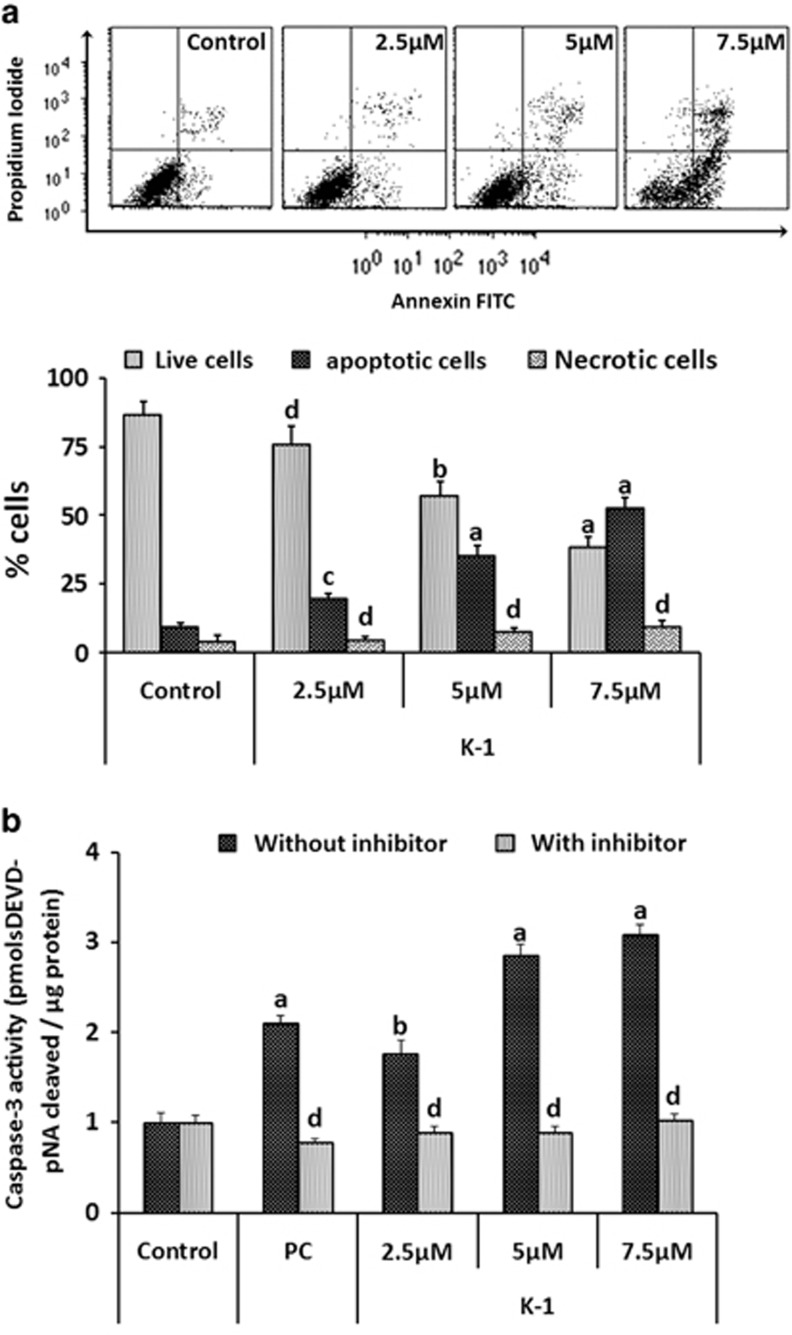

K-1 triggers apoptosis in primary endometrial hyperplasial cells

To check whether the loss in cell viability on treatment with the K-1 is due to the induction of apoptosis, we analyzed annexin-V/PI-stained cells by flow cytometry, caspase-3 activity and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. In the annexin-V/PI assay, K-1 significantly increased the percentage of apoptotic cells in a concentration-dependent manner and at 7.5 μM; the apoptotic cell fraction was approximately fivefold higher as compared with that of control (P<0.001) (Figure 6a). In the caspase-3 activity assay, it was found to be increased by threefold at 7.5 μM of K-1 (P<0.001) (Figure 6b). Also, visually, a higher number of TUNEL-positive cells were observed in K-1-treated groups (Figure 7a).

Figure 6.

K-1 induces apoptosis and activates caspase-3 in primary endometrial hyperplasial cells. (a) Analysis of apoptosis in primary endometrial hyperplasial cells treated with compound K-1 by flow cytometric analysis of annexin-V/PI-stained cells after 48-h culture. AV+/PI−-intact cells; AV−/PI+-nonviable/necrotic cells; AV+/PI− and AV+/PI+-apoptotic cells. Representative images are shown in the upper panel and the percentage of cell fraction with S.E.M. was calculated based on three independent experiments. P values are a-P<0.001, b-P<0.01, c-P<0.05 and d-P>.05 versus control. (b) Induction of caspase-3 proteolytic activity was checked in primary endometrial hyperplasial cells after treatment of compound K-1 (2.5, 5 and 7.5 μM). Proteolytic activity was measured by cleavage of the caspase-3 substrate DEVD-pNA as described in ‘Materials and Methods'. Cell lysates were prepared after 48 h. Results are expressed as mean±S.E.M., n=3.± S.E.M., P values area -P<0.001, b-P<0.01, c-P<0.05 and d-P>0.05 versus control

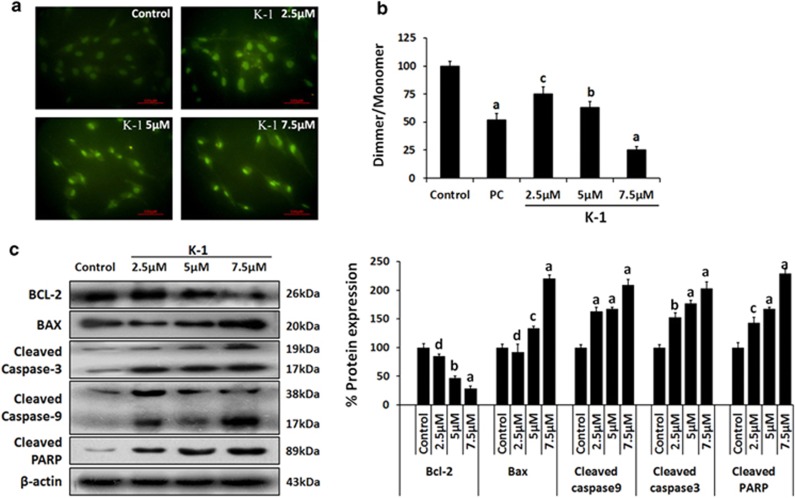

Figure 7.

Effect of K-1 on TUNEL staining, expression of markers of apoptosis in primary endometrial hyperplasial cells. (a) Primary endometrial hyperplasial cells were treated with vehicle, 2.5, 5 and 7.5 μM of the compound K-1 for 24 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized and the procedure was followed as described in Materials and Methods. Representative figures stained for TUNEL showing a large number of TUNEL-positive cells (greenish yellow) in K-1-treated groups in a concentration-dependent manner. Cell images were grasped using a Nikon fluorescence microscope at × 40. (b) Cells were treated with vehicle, or compound K-1 at 2.5, 5 and 7.5 μM concentrations, for 24 h. Mitochondrial membrane potential was measured by normalization of the 590 : 530 nm JC-1 emission ratios and then normalized to untreated cells. Results are expressed as mean±S.E.M., n=3.± S.E.M., P values are a-P<0.001, b-P<0.01, c-P<0.05 and d-P>0.05 versus control. (c) Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of compound for 48 h, and 35 μg whole cell lysate in each lane was probed for the expression of Bcl-2,Bax, cleaved caspase3/9 and cleaved PARP using specific antibodies. β-actin was used as a control to correct for loading. Representative blots are shown (left panel) and densitometric quantitation of protein expression levels are shown as fold changes (right panel). Data are expressed as mean of three different experiments;±S.E.M., P values are a-P<0.001, b-P<0.01, c-P<0.05 and d-P>0.05 versus control

Further, the mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ψm) of hyperplasial cells was analyzed and results showed a significant drop (P<0.001) in Δψm in the presence of K-1 (Figure 7b). These results indicated that the apoptotic signaling pathway activated by K-1 is likely to be mediated via the mitochondrial pathway (Figure 6b). The role of K-1 in inducing apoptosis was analyzed by expression of cleaved caspase-9 and 3 and cleaved PARP (Figure 7c). Densitometric results showed that K-1 significantly upregulated the expression of caspase-9 and 3 and cleaved PARP. The levels of the pro- and antiapoptotic proteins (Bax and Bcl-2) were also found to be altered in K-1-treated hyperplasial cells. K-1 elicited a dose-dependent reduction in Bcl-2 expression (P<0.001) and an increase in the Bax up to 1.8-fold (P<0.001) (Figure 7c).

Discussion

Endometrial hyperplasia represents a precancerous, non-physiological and noninvasive proliferation of the endometrium18 and eventually that may lead to endometrial carcinoma. In case of enhanced or unopposed estrogen signaling, constitutive activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling triggers endometrial hyperplasia, which may further develop into endometrial cancer.10 Among various known Wnts, the Wnt7a ligand is able to directly stimulate canonical Wnt signaling and induce proliferation in endometrium.19, 20 We have previously shown that K-1 shows inhibitory activity against endometrial hyperplasia in a rat model.14 In the current study, we have established a human primary atypical endometrial hyperplasia cell culture for studying its effect on the human tissue. Initially, we compared the growth pattern of normal endometrial cells and hyperplasial cells, and it was interesting to observe that the compound significantly inhibited the growth of hyperplasial cells but not of normal endometrial cells. However, K-1 inhibited the estrogen-induced growth of normal endometrial cells. Under similar conditions, PCNA levels also remained below the baseline levels in K-1-treated cells. The difference in PCNA levels caused by the compound in the presence of E2 indicated the suppression of estrogen action caused by K-1 in these cells (Figures 1 and 5). Because in hyperplasial endometrial cells, the unoppposed estrogen action is supposed to be responsible for cellular growth, we hypothesize that the differential and specific effect of K-1 on hyperplasial cells may be due to its effect on estrogen-regulated signaling pathways. Also, in endometrium, estrogen has been shown to induce the Wnt signaling pathway, whereas progesterone has been shown to suppress the same.5 Therefore, we further tried to analyze whether K-1 has any effect on Wnt signaling using human endometrial primary culture. We have observed that K-1 suppresses the endometrial primary culture growth via downregulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

The regulation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway is governed by Wnt ligand and Frizzled receptor itself and various other downstream markers such as axin2, β-catenin, adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC) and Gsk3β. Cytoplasmic stabilized β-catenin migrates to the nucleus, where it associates with TCF/LEF transcription factors, leading to the transcription of β-catenin target genes.21, 22 We found the reduced expression of β-catenin as well as its nuclear accumulation as observed by confocal microscopy in K-1-treated cells. Subsequently, the downstream effectors CyclinD1 and c-myc23 were found to be downregulated in treated cells. Further, the reduced expression of Wnt7a ligand and FZD6, and the increased expression of axin2 accompanied by a reduced expression of phosphorylated Gsk3β in human hyperplasial primary cell culture under the influence of K-1 suggested the attenuation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

One of the known Wnt/β-catenin inhibitors, Dkk-1, is a proapoptotic gene,24 which has been demonstrated to interact with LRP5/6 and to inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling via disrupting the binding of the Wnt/FZD ligand–receptor complex.25 Interestingly, K-1 caused the induced expression of Dkk-1 and inhibited Wnt/ FZD ligand–receptor binding as demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation experiment. Evidences have been given that progesterone induction of Dkk-1 and Foxo-1 results in the inhibition of Wnt signaling in human endometrium.6 It appears that our compound behaves like progesterone in modulating the Wnt signaling in endometrial cells although it is known to bind to estrogen receptor (ER). It competes with estradiol for binding to both hERα and hERβ indicating its interaction with both ER subtypes.17 We have earlier shown that K-1 inhibits classical and non-classical estrogen signaling in uterus.15, 16 Because Wnt signaling pathway is known to be regulated via estrogen, we explored further whether K-1 is able to suppress the estrogen-induced Wnt signaling in human endometrial cells. Interestingly, the profound effect of K-1 on Wnt7a expression was observed in hyperplasial cells and also the phosphorylated PI3K was reduced in these cells when incubated with K-1. In experiments on normal cells, no significant effect on Wnt7a and pPI3k was observed, but when cells were treated with E2, the significant inhibition in these proteins was observed. This indicates that K-1 acts specifically on E2-induced Wnt expression. In absence of E2, the basal levels of Wnt were not changed. The probable reason may be the inhibition of E action in endometrial hyperplasial cells which might have higher expression levels of ER. Besides, in hyperplasial cells, the aberrant endogenously synthesized E may be responsible for higher ER expression. Because K-1 is already known to interact with ERs, and antagonize the action of E,14, 17 it might cause the inhibition of estrogen-induced signaling mechanism in normal endometrial cells when exogenous E was given.

Further, it is likely that compound is responsible for suppression of Wnt signaling due to interference with ER-mediated signaling in endometrial hyperplasia.4 Thus, the difference in K-1 action in endometrial hyperplasial cells or estradiol-treated normal endometrial cells as compared with normal endometrial cells may be because of the change in expression of ERs, ERα/ERβ ratio26 and/or the expression of coactivators or corepressors.27 These differences may modulate the role of K-1 in different cell types leading to cell-specific effects.

ERα has been observed to be associated with important growth factor pathway such as the PI3K pathway, thus indirectly cross-talking with canonical Wnt signaling.24 In PI3K/Akt survival pathway, phosphorylation of PI3K and its downstream target Akt enhances proliferation and survival of cells through suppression of apoptosis. Akt phosphorylation causes many modulations in a cell to make it cancerous. Deactivation of Gsk3β by Akt phosphorylation is one of those modulations.25 Akt also activates the expression of the antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2, which negatively controls the expression of proapoptotic gene Bax,26, 27 and subsequently inhibits the mitochondria-induced apoptotic signaling cascade. Here, we demonstrated that K-1 was involved in inhibiting the phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt. Significant downregulation of the expression of Bcl-2 and the upregulation of Bax observed may be due to reduced Akt activity that may enhance Cyt-c release from mitochondria by reducing its membrane potential in K-1-treated cells. Further, mitochondria-induced apoptotic signaling cascade was supported by the presence of cleaved fragments of caspase-9 and 3 and PARP. These findings were supported by caspase-3 activation, TUNEL-staining and annexin-V/PI staining.

In summary, the present study has demonstrated that K-1 hinders the Wnt/β-catenin signaling in endometrial hyperplasial cells, Wnt7a/ FZD6 binding and subsequent signaling. It induced axin2 and Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor Dkk-1. Simultaneously, K-1 also downregulated the phosphorylation of PI3K/Akt, which enhanced apoptosis in primary endometrial hyperplasial cells. Hypothetically, two mechanisms may be involved in the regulation of Wnt signaling under the influence of these effects; compound K-1 either enhances Dkk-1 and antagonizes the estrogen-induced Wnt signaling via ER (through ERE) or it might induce Foxo-1 expression, which acts as transcription factor for Wnt-regulated gene expression, although the latter possibility needs to be analyzed further. Altogether, these data suggest that K-1 significantly down regulates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling which might be considered as one of the mechanisms responsible for specific anti-proliferative activity of K-1 in human endometrial hyperplasial cells. Thus, the benzopyran derivative K-1 can serve as a future therapeutic agent for treatment of endometrial hyperplasia over the currently available therapy.

Materials and Methods

Compound

Antibodies and reagents

All culture media and other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Anti-cytokeratin7, -ERα, -PR, -PCNA, -pGsk3β (ser9), -Gsk3β, -c-myc, -β-catenin, -CyclinD1, -Wnt7a, -FZD6, -Dkk-1, -pPI3K(tyr 485), -PI3K, -Akt, -β-actin antibodies, peroxidase- and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibodies were procured from Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX, USA). Antibodies for axin2, pAkt(ser473), cleaved caspase-3 and 9, cleaved PARP, Bax and Bcl-2 were purchased from Cell Signalling Technology, Life Sciences (Boston, MA, USA).

TUNEL detection kit was obtained from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Immuno-Blot PVDF membrane was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). ECL reagent and ECL Hyperfilm were purchased from GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, UK).

Endometrial tissue collection

Endometrial hyperplasia samples (five different cases of atypical hyperplasia) were collected from patients with abnormal uterine bleeding (age: 25–40 years) from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, King George's Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. Normal endometrial samples (three different cases) were collected from the patients undergoing hysterectomy for uterine prolapse reasons. An informed written consent was obtained from each patient and the study was approved by the local Human Ethics Committee.

Histopathological examination such as gland-to-stroma ratio, gland's size and shape, cytologic atypia, nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, hyperchromatosis by simple staining and expression of ER, progesterone receptor (PR) and proliferation marker (Ki67) by immune-histochemistry were carried out by expert gynecologists and pathologists from Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Department of Pathology, King George's Medical University, who confirmed the category of samples as hyperplasia to be of atypical type and after the evaluation, tissue samples were taken for further studies.

Primary culture of endometrial cells

Cell isolation was based on the methods as described by Genc et al.30 Briefly, tissues were collected in MEM, minced and incubated with 1 mg/ml collagenase and DNase (2 mg/ml) for 2 h at 37 °C with periodic mixing. Digested tissue was mechanically dissociated and resuspended in 2 ml of fresh MEM. The cells were filtered through 18-mesh sterile gauze, centrifuged and washed twice with MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine and 2% of antibiotic-antimycotic solution. Then cells were transferred into plastic culture flasks (75 cm2) (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) and incubated at 37 °C with saturating humidity and 5% CO2. Prior to experiments, cells were cultured in phenol red-free MEM supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution.

The endometrial hyperplasial cells were characterized by examining the expression of cytokeratin-7, an epithelial marker, by immunofluorescence (Supplementary Figure S1).

Equal numbers of cells were used each time in separate studies.

Cell viability assay

For determination of cell viability, MTT assay was performed. The primary culture of endometrial hyperplasial cells and normal endometrial cells were seeded (2.5 × 103 cells/well) into 96-well plate and treated with K-1 (1, 2.5, 5, 7.5 and 10 μM) in the absence or presence of estradiol (10 nM) for 48 h. Then MTT (0.5 mg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. After removing supernatants, cells were incubated with 100 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The OD was read with Microquant (Bio Tek, Winooski, VT, USA) at 540 nm. The IC50 value of the compound was determined by Compusyn software. The experiments were performed three times with five replicates in case of hyperplasial endometrial primary cells and with three replicates in case of normal endometrial primary cells.

Western blot analysis

Endometrial primary culture cells were treated with vehicle or various concentrations of K-1 or estradiol for 48 h. After each treatment, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail. Equal amounts of protein were separated by gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immuno-Blot PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% skimmed milk and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were then incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h. Antibody binding was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare). After developing, the membrane was stripped and re-probed with β-actin, Gsk3β, PI3K and Akt antibodies. Each experiment was repeated three times. Quantitation of band intensity was performed by densitometry using Quantity-One software (v.4.5.1) and a Gel-Doc2000 imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence imaging by confocal microscopy

Primary endometrial hyperplasia cells were grown on coverslips in 12-well plate and treated with vehicle, or 2.5, 5 and 7.5 μM of K-1 for 24 h. Cells were then fixed in methanol and acetone (1 : 1) and followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were washed with PBS and blocked with 1% BSA and incubated with β-catenin antibody overnight followed by 1 h incubation with fluorescence-tagged secondary antibody. Following incubation, cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min. Images were captured at × 100 and analyzed using LSM-Image-Examiner Software to detect fluorescence and DAPI emissions. Cells not exposed to primary antibodies served as negative controls.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

Interaction between Wnt7a ligand and FZD6 proteins was studied by co-immunoprecipitation of the complex followed by immunoblotting. Protein A-Sepharose beads were used and the desired protein was immunoprecipitated according to manufacturer's instructions (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, 2 μg of anti-FZD6 was added to 500 μg of cell lysate treated with indicated concentrations of K-1 and incubated for overnight at 4 °C. For negative control, cell lysate was incubated with corresponding non-immune serum. Then, 100 μl of beads suspension was added and samples were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitated complexes were collected by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 2 min at 4 °C and washed three times with RIPA buffer. Immunoprecipitates were resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer and heated for 5 min at 95 °C. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 12 000 × g for 30 s at room temperature. Equal volumes of immunoprecipitated proteins were run on 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. The proteins were probed with anti-Wnt7a, followed by the corresponding secondary antibody. Bands were detected and analyzed by densitometry using Quantity-One Software (v. 4.5.1) and a Gel-Doc2000 (Bio-Rad) imaging system.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated nick end labeling assay

TUNEL staining was performed by using a ‘Dead End' fluorometric TUNEL kit (Roche, Upper Bavaria, Germany) as per manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, slides were equilibrated with equilibration buffer and were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with recombinant terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (rTdT) incubation buffer. The negative control slide was incubated without the rTdT enzyme. Sections were then rinsed in buffer to stop the reaction, followed by PBS washing and examined under light microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i, Shinagawa-Ku, Tokyo, Japan). Images were captured using an NIS-Elements F-3.0 camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

Δψm was determined using JC-1 (cationic mitochondrial vital dye) as a probe according to the method of Dey and Moraes.31 Briefly, treated cells were collected and incubated for 20 min with 5 μM JC-1 at 37 °C, washed and resuspended in media. The Δψm was measured at 590 nm for J-aggregates and at 530 nm for J-monomer. The ratio of 590/530 nm was considered as the relative Δψm value. The experiments were performed thrice with three replicates in each.

Annexin-V/propidium iodide labeling and flow cytometry assay for apoptosis

Cells (2 × 105cells/ml) were cultured in 6-well plates and treated with K-1 (2.5, 5 and 7.5 μM) for 48 h. Adherent and non-adherent cells were probed with FITC-conjugated annexin-V and PI. The staining profiles were determined with FACScan and Cell-Quest software. The experiments were performed thrice with three replicates in each.

Caspase-3 colorimetric assay

Caspase-3 activity was determined using the colorimetric Caspase-3 assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, cells were trypsinized and centrifuged for 5 min at 600 g at 4 °C. Then, cell pellets were resuspended in ice-cold cell lysis buffer and incubated on ice for 20 min. Supernatants collected after centrifugation were incubated with 1 mM caspase-3 substrate (DEVD-pNA) for 2 h at 37 °C and the OD was measured at 405 nm. The experiments were performed three times with three replicates in each.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ±S.E.M. for at least three separate determinations for each experiment. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA and Newman Keul's test, and the levels of probability were noted.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr AL Vishwakarma and Dr K Mitra, SAIF-facility, CDRI for help in flow cytometric analysis and confocal microscopy. The study was supported by grants from Indian Council of Medical Research, India. VC is the recipient of senior research fellowship from Indian Council of Medical Research. The CDRI communication number is 8736.

Glossary

- K-1

2-(piperidinoethoxyphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2H-benzo(b)pyran

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- FZD6

frizzled receptor

- Gsk3β

glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta

- Dkk-1

dickkopf-1

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- MTT

[3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide]

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- rTdT

recombinant terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

- Δψm

membrane potential

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PI

propidium iodide

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorting

- DEVD-pNA

acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp p-nitroanilide

- LRP

LDL receptor-related proteins

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- PARP

poly ADP-ribose polymerase

- APC

adenomatosis polyposis coli

- TCF

T-cell factor

- LEF

lymphoid enhancing factor

- Cyt-c

cytochrome complex

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by A Stephanou

Supplementary Material

References

- Luu HH, Zhang R, Haydon RC, Rayburn E, Kang Q, Si W, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway as a novel cancer drug target. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2004;4:653–671. doi: 10.2174/1568009043332709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rider V, Isuzugawa K, Twarog M, Jones S, Cameron B, Imakawa K, et al. Progesterone initiates Wnt-beta-catenin signaling but estradiol is required for nuclear activation and synchronous proliferation of rat uterine stromal cells. J Endocrinol. 2006;191:537–548. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.07030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarapore RS, Siddiqui IA, Mukhtar H. Modulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway by bioactive food components. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:483–491. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, van der Zee M, Fodde R, Blok LJ. Wnt/Beta-catenin and sex hormone signaling in endometrial homeostasis and cancer. Oncotarget. 2010;1:674–684. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Horst PH, Wang Y, van der Zee M, Burger CW, Blok LJ. Interaction between sex hormones and WNT/ß-catenin signal transduction in endometrial physiology and disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;358:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Hanifi-Moghaddam P, Hanekamp EE, Kloosterboer HJ, Franken P, Veldscholte J, et al. Progesterone inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in normal endometrium and endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5784–5793. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas M. Wnt signaling and the mechanistic basis of tumour development. J Pathol. 2005;205:130–144. doi: 10.1002/path.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanendrarajan S, Kim Y, Schmidt-Wolf IGH. Understanding and targeting the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway in chronic leukemia. Leuk Res Treatment. 2011;2011:329572. doi: 10.4061/2011/329572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa M, Okayasu I. Frequent nuclear beta-catenin accumulation and associated mutations in endometrioid-type endometrial and ovarian carcinomas with squamous differentiation. J Pathol. 2001;194:59–67. doi: 10.1002/path.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholten AN, Creutzberg CL, van den Broek LJ, Noordijk EM, Smit VT. Nuclear beta-catenin is a molecular feature of type I endometrial carcinoma. J Pathol. 2003;201:460–465. doi: 10.1002/path.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emons G, Fleckenstein G, Hinney B, Huschmand A, Heyl W. Hormonal interactions in endometrial cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2000;7:227–242. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0070227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmedkhanov A, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Toniolo P. Role of exogenous and endogenous hormones in endometrial cancer: review of the evidence and research perspectives. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;943:296–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar JD, Setty BS, Duran S, Kapil RS. Biological profile of 2-[4-(2-N-piperidinoethoxy) phenyl]-3-phenyl (2H) benzo (b) pyran-a potent anti-implantation agent in rat. Contraception. 1991;44:461–472. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(91)90036-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharkwal G, Fatima I, Kitchlu S, Singh B, Hajela K, Dwivedi A. Anti-implantation effect of 2-[piperidinoethoxyphenyl]-3-[4-hydroxyphenyl]-2H-benzo(b)pyran, a potent antiestrogenic agent in rats. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1322–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra V, Fatima I, Saxena R, Kitchlu S, Sharma S, Hussain MK, et al. Apoptosis induction and inhibition of hyperplasia formation by 2-[piperidinoethoxyphenyl]-3-[4-hydroxyphenyl]-2H-benzo(b)pyran in rat uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:362e1–362e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima I, Chandra V, Saxena R, Manohar M, Sanghani Y, Hajela K, et al. 2,3-Diaryl-2H-1-benzopyran derivatives interfere with classical and non-classical estrogen receptor signaling pathways, inhibit Akt activation and induce apoptosis in human endometrial cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;348:198–210. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima I, Saxena R, Kharkwal G, Hussain MK, Yadav N, Hajela K, et al. The anti-proliferative effect of 2-[piperidinoethoxyphenyl]-3-[4-hydroxyphenyl]-2H-benzo(b) pyran is potentiated via induction of estrogen receptor beta and p21 in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;138:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn LC, Meinel A, Handzel R, Einenkel J. Histopathology of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma: an update. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11:297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui TD, Zhang L, Rees MC, Bicknell R, Harris AL. Expression and hormone regulation of Wnt2, 3, 4, 5a, 7a, 7b and 10b in normal human endometrium and endometrial carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:1131–1136. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmon KS, Loose DS. Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 regulates two Wnt7a signaling pathways and inhibits proliferation in endometrial cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1017–1028. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar SS, Yu Y, Nautiyal J, Patel BB, Majumdar AP. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway regulates growth and maintenance of colonospheres. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:212. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu P, Zhang Z, Kang C, Jiang R, Jia Z, Wang G, et al. Down regulation of Wnt2 and beta-catenin by siRNA suppresses malignant glioma cell growth. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:351–361. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulac S, Overgaard MT, Hamilton AE, Jumbe NL, Suchanek E, Giudice LC. Dickkopf-1, an inhibitor of Wnt signaling, is regulated by progesterone in human endometrial stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1453–1461. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn VE, Chu ML, Choi HJ, Tran D, Abo A, Weis WI. Structural basis of Wnt signaling inhibition by Dickkopf binding to LRP5/6. Dev Cell. 2011;21:862–873. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K, Zhong G, He F. Expression of estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ in endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma. J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:537–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.15321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchikawa J, Shiozawa T, Shih H, Miyamoto T, Feng YZ, Kashima H, et al. Expression of steroid receptor coactivators and corepressors in human endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma with relevance to steroid receptors and Ki-67 expression. Cancer. 2003;98:2207–2213. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapil RS, Durani S, Dhar JD, Setty BS.Novel benzopyrans and process for their production. 1990; European patent no. 90308787/2.

- Sharma AP, Saeed A, Durani S, Kapil RS. Structure-activity relationship of antiestrogens. Effect of the side chain and its position on the activity of 2,3-diaryl-2H-1-benzopyrans. J Med Chem. 1990;33:3216–3222. doi: 10.1021/jm00174a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genc S, Attar E, Gurdol F, Kendigelen S, Bilir A, Serdaroglu H. The effect of COX-2 inhibitor, nimesulide, on angiogenetic factors in primary endometrial carcinoma cell culture. Clin Exp Med. 2007;7:6–10. doi: 10.1007/s10238-007-0119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey R, Moraes CT. Lack of oxidative phosphorylation and low mitochondrial membrane potential decrease susceptibility to apoptosis and do not modulate the protective effect of Bcl-x(L) in osteosarcoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7087–7094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.