Abstract

Caspase-2 has been implicated in various cellular functions, including cell death by apoptosis, oxidative stress response, maintenance of genomic stability and tumor suppression. The loss of the caspase-2 gene (Casp2) enhances oncogene-mediated tumorigenesis induced by E1A/Ras in athymic nude mice, and also in the Eμ-Myc lymphoma and MMTV/c-neu mammary tumor mouse models. To further investigate the function of caspase-2 in oncogene-mediated tumorigenesis, we extended our studies in the TH-MYCN transgenic mouse model of neuroblastoma. Surprisingly, we found that loss of caspase-2 delayed tumorigenesis in the TH-MYCN neuroblastoma model. In addition, tumors from TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice were predominantly thoracic paraspinal tumors and were less vascularized compared with tumors from their TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ counterparts. We did not detect any differences in the expression of neuroblastoma-associated genes in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumors, or in the activation of Ras/MAPK signaling pathway that is involved in neuroblastoma progression. Analysis of expression array data from human neuroblastoma samples showed a correlation between low caspase-2 levels and increased survival. However, caspase-2 levels correlated with clinical outcome only in the subset of MYCN-non-amplified human neuroblastoma. These observations indicate that caspase-2 is not a suppressor in MYCN-induced neuroblastoma and suggest a tissue and context-specific role for caspase-2 in tumorigenesis.

The caspase family of cysteine proteases are highly conserved regulators of cell death by apoptosis.1 In addition to their pro-apoptotic function, many caspases also have non-apoptotic roles in other physiological processes, such as inflammation, necrosis and tumor suppression.2, 3, 4 The most highly conserved caspase, caspase-2, has recently been demonstrated to function in the cellular stress response, protection against ageing, maintenance of genome stability and in tumor suppression.2, 5, 6, 7, 8

The tumor suppressor function of caspase-2 was first demonstrated using E1A/Ras-transformed caspase-2-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), which showed an increased tumorigenic potential in athymic nude mice.7 Further supporting evidence came from experiments demonstrating that caspase-2 deficiency enhances B-cell lymphoma development in Eμ-Myc transgenic mice7 and mammary carcinomas in MMTV/c-neu mice,9 suggesting that caspase-2 prevents oncogene-induced lymphomas and epithelial tumors. Importantly, tumor suppression by caspase-2 is also evident in the non-oncogene-driven Atm−/− thymoma mouse model.10

Given its role in apoptosis, the tumor suppression function of caspase-2 was thought to be associated with this role, via the elimination of mutagenic or potentially tumorigenic cells. Recent studies have now indicated that the role of caspase-2 may extend beyond apoptosis and that its tumor suppression function may, in part, be mediated by maintaining genomic stability and/or the oxidative stress response. Caspase-2-deficient MEFs and tumor cells from Eμ-Myc/Casp2−/−, MMTV/c-neu/Casp2−/− and Atm−/−;Casp2−/− mice all display aberrant proliferation, and increased genomic instability6, 9, 10 and indicate that caspase-2 is important for the maintenance of genome stability. Importantly, the role of caspase-2 in maintaining genomic stability in primary cells appears to be required for its tumor suppressor function.10

Genomic instability is a hallmark of cancer11 and the overexpression of Myc family oncoproteins is commonly associated with genomic instability and a wide spectrum of human cancers.12, 13, 14 Interestingly, a common feature of the oncogene-induced tumor models used in the study of caspase-2 tumor suppressor function is the overexpression of c-Myc15 or aberrant c-Myc signaling.16, 17, 18 Given the role of Myc proteins as key mediators of genomic instability as well as cell proliferation, cell growth and DNA damage, we were interested in further assessing whether caspase-2 can promote tumor suppression in other MYC-dependent mouse tumor models. We used the MYCN mouse model of neuroblastoma (TH-MYCN mouse), in which MYCN is constitutively expressed under the control of the rat tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) promoter leading to neural crest cell-specific expression and early-onset neuroblastoma.19 Amplification of MYCN occurs in ∼20% of human neuroblastomas and high MYCN protein levels are strongly associated with tumor progression and poor clinical outcome.20, 21 Thus, the TH-MYCN transgenic mouse model recapitulates many clinical features of aggressive neuroblastomas in humans and provides a powerful model of preclinical neuroblastoma.19, 22

MYCN-mediated neuroblastoma onset and progression is commonly associated with additional genetic events, including the expression of the key genes including Odc1, Mrp1, SirT1 and Ras.23, 24, 25 A recent study has found that caspase-8 is in fact a potent suppressor of neuroblastoma, with the loss of caspase-8 expression occurring in ∼70% of neuroblastoma patients.26, 27 Interestingly, the loss of caspase-8 also promotes bone marrow metastasis in the TH-MYCN neuroblastoma mouse model.26, 27 The role of other caspases in neuroblastoma has not previously been examined, and given the function of caspase-2 in tumor suppression, provided additional relevance in assessing its role in this model.

This study shows that caspase-2 is not able to suppress neuroblastoma development in TH-MYCN mice. In contrast to a role for caspase-2 as a tumor suppressor, our findings demonstrate that loss of caspase-2 somewhat delays neuroblastoma onset in mice. Interestingly, expression array data from human neuroblastoma show a strong correlation between low caspase-2 levels and improved outcome. Our data demonstrate that the tumor suppressor function of caspase-2 is not specific to Myc-mediated oncogenesis and that its role is likely to be tissue- and/or context-specific.

Results

Caspase-2 deficiency delays neuroblastoma development in TH-MYCN mice

Loss of caspase-2 leads to enhanced tumorigenesis following c-Myc-mediated oncogenic stress7, 9 but has a minimal role in regulating tumor development in carcinogen- or irradiation-induced tumor models.28 To further examine the tumor-suppressive role of caspase-2 following MYC-mediated oncogenic stress in different tissues, we used the TH-MYCN mouse model of neuroblastoma to generate TH-MYCN transgenic/Caspase-2-deficient (TH-MYCN/Casp2−/−) mice and monitored these mice for tumor development over a 1-year period.

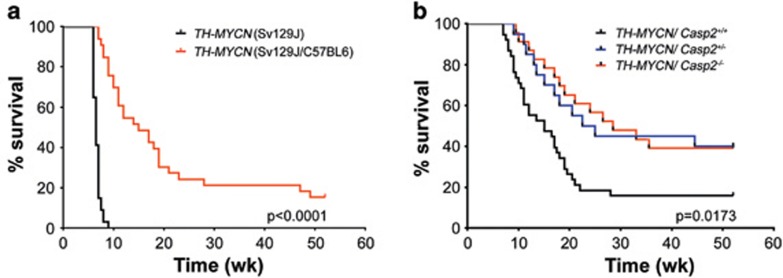

The TH-MYCN mice were originally derived in the SV129J genetic background and, consistent with previous studies29 in our specific pathogen-free animal house conditions, these mice developed neuroblastoma at an average age of 6.65±0.694 weeks (mean±S.D.) and incidence of 100% (n=34; Figure 1a). Given that the Casp2−/− mice were derived on a C57BL6 genetic background and the genetic background can affect tumor development,30 we generated cohorts of TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+, TH-MYCN/Casp2+/− and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice in a mixed genetic background (Sv129J/C57BL6) and once they had achieved congenicity, compared tumor onset in littermates. Consistent with previous reports for TH-MYCN (C57BL6) mice, the TH-MYCN (Sv129J/C57BL6) develop tumors at a later, and more variable onset (average age 15.9±12.47 weeks) with reduced incidence (28/33=84.8%) compared with TH-MYCN (Sv129J) mice (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Caspase-2 deficiency delays the onset of MYCN-mediated neuroblastoma. (a) Comparison of Kaplan–Meier survival curves of TH-MYCN mice (Sv129J mouse background, n=30) and TH-MYCN mice (C57Bl6/Sv129J mixed background; n=31). P-value determined by log-rank (Mantel cox) test. (b) Survival curves of TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+, TH-MYCN/Casp2+/− and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice (C57BL6/Sv129J mixed littermates). P-value for TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ compared with TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice was determined by log-rank test, with P<0.05 being significant

Intriguingly, in contrast to its expected role as a tumor suppressor, the loss of caspase-2 delayed tumor onset in TH-MYCN (Sv129J/C57BL6) mice, with only 14 out of 22 (63.63%) mice developing tumors at an average onset of 19.82±18.5 weeks compared with 14.09±13.5 weeks for their TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ littermates (P=0.0173 log-rank test; Figure 1b and Supplementary Figures S1a and c). In addition, loss of even a single caspase-2 allele significantly delayed tumor onset in these mice (P=0.0303; Figure 1b). Furthermore, whereas the TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ mice predominantly developed abdominal tumors arising from the adrenal medulla, the majority of TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice developed smaller paraspinal thoracic tumors (Supplementary Figure S1b). Further analysis of tumors showed that there was no difference in relative tumor size between genotypes and no correlation between tumor onset and size (Supplementary Figure S1d). We carried out histological examination to assess metastatic dissemination of tumor cells to the lung, kidney and bone marrow as previously reported in TH-MYCN mice;19, 27, 31 however, the extent of metastasis was comparable between TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice (data not shown).

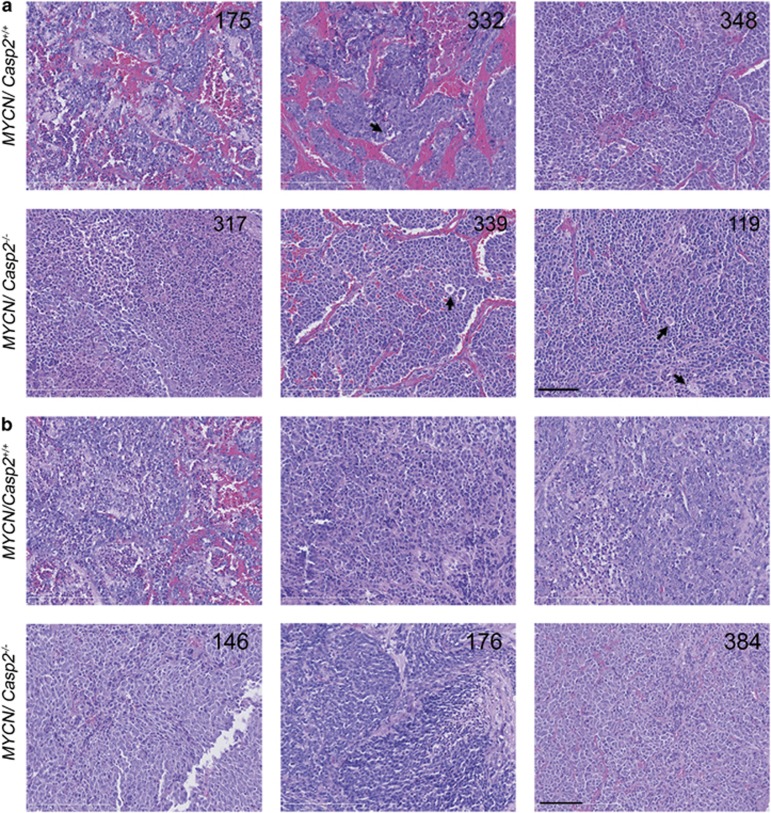

Histological examination of tumors from TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice was consistent with the presence of islands of undifferentiated neuroblastoma cells sometimes surrounded by clusters of larger, differentiated neuroblastoma cells and tangible body macrophages characteristic of mouse neuroblastoma31 (Figure 2). The main histological difference between the two groups of tumors was the observation that the majority of the abdominal tumors from TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice did not appear vascularized (only 3/14 tumors exhibiting obvious vasculature) compared with abdominal tumors from TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ (25/38 were highly vascularized; Figure 2). These data may indicate that caspase-2 deficiency affects tumor progression.

Figure 2.

Histopathology of TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− neuroblastomas. Representative images ( × 40) of hematoxylin and eosin stained (a) abdominal tumors and (b) thoracic tumors, from TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice. Three different tumor samples for each genotype are shown, with numbers indicating animal number. Arrows highlight tangible body macrophages. Scale bar represents 50 μm

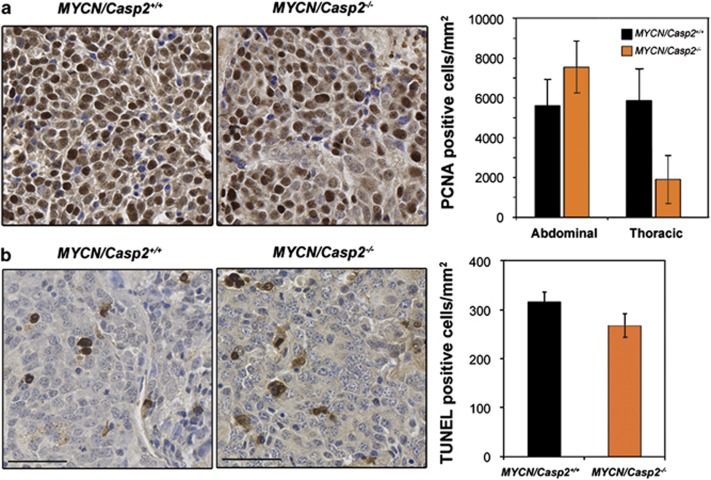

Loss of caspase-2 does not affect cell proliferation or apoptosis in MYCN neuroblastoma

Previous studies have demonstrated a role for caspase-2 in the regulation of cell proliferation and cell cycle progression.6, 10 We therefore assessed the proliferative capacity of TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumors, as determined by proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) expression. There were no significant differences in PCNA levels in abdominal neuroblastomas between genotypes (Figure 3a). Interestingly, there was a trend toward reduced PCNA expression in the paraspinal thoracic tumors from TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice; however, given the high variability in some tumor samples, this difference was not significant (P=0.08, Figure 3a). These data demonstrate that the loss of caspase-2 does not enhance the proliferative capacity of TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumors.

Figure 3.

Caspase-2 does not affect proliferation or cell death in neuroblastoma. Representative images ( × 40) and quantification of (a) PCNA and (b) TUNEL immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded neuroblastoma sections derived from TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ (n=10 and 9, respectively) and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− (n=9 and 11, respectively) mice. Scale bar represents 50 μm

We next assessed the level of apoptosis in the MYCN tumors using TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling) immunohistochemistry. There was no significant difference in the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumors compared with TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ tumors, indicating that caspase-2 does not have a significant role in neuroblastoma cell death (Figure 3b). Given that caspase-2 has been shown to have a role in the DNA damage response, we isolated and cultured primary neuroblastoma cells32 and exposed them to gamma radiation. We did not observe any significant differences in the level of apoptosis in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− compared with TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ cells (data not shown). We were unable to detect p53 or phosphorylated p53 (Ser15) by immunoblotting, in any of the tumor samples analyzed, which is consistent with neuroblastomas lacking p53 mutation, and consistent with previous reports.33, 34 Furthermore, we did not detect any differences in p53 transcript levels in tumor samples or in the levels of p53 target genes, Mdm2 and p21 (Supplementary Figures S2a and b). These data indicate that DNA damage-mediated cell death and p53 regulation in neuroblastomas is caspase-2-independent.

Given caspase-2 has an important role in maintaining genomic stability,6 we assessed the frequency of aneuploidy in TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− neuroblastoma cells. However, we did not detect any differences in the extent of aneuploidy in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumor cells (Supplementary Figure S3), indicating that caspase-2 does not function to maintain genomic integrity in MYCN-expressing neuroblastoma cells.

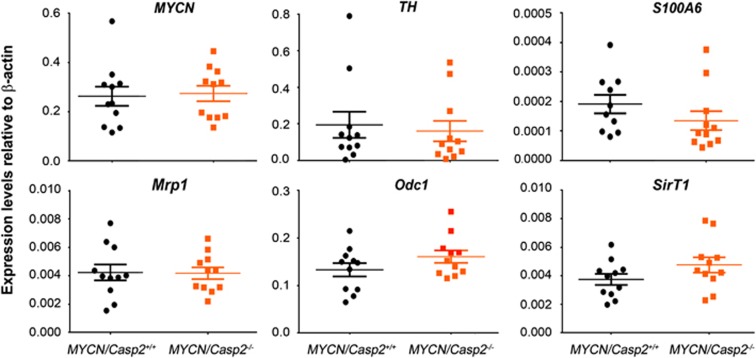

Neuroblastoma-associated gene expression in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumors

Neuroblastoma is characterized at the molecular level by the high expression of several genes, including the neuronal markers TH and S100A6. In addition, several MYCN target genes, including multidrug resistant protein-1 (Mrp1), sirtuin 1 (SirT1) and ornithine decarboxylase (Odc1), are associated with the onset and aggressiveness of disease.19, 23, 24, 25 To determine whether the reduced tumor incidence in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice was associated with disrupted expression of these neuroblastoma-associated genes, we examined their transcript levels in both thoracic and abdominal tumors (Figure 4). As expected, MYCN transgene expression was similar in both TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumours at both the transcript and protein levels (Figures 4 and 5), indicating that altered MYCN expression was not responsible for the reduced tumor incidence in the TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice. Whereas expression levels of the neuroblastoma-related genes assessed were lower in thoracic tumors compared with abdominal tumors, importantly, there were no differences between TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− (Figure 4), indicating that the loss of caspase-2 does not affect neuroblastoma progression in mice.

Figure 4.

Expression of neuroblastoma-associated genes in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumors. qPCR analysis of MYCN, TH, S100A6, Odc1, Mrp, SirT1 gene expression in TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumors (n=6 abdominal and n=5 thoracic tumors per genotype). Expression of each gene was determined relative to internal β-actin control gene. Data represent the mean±S.E.M.

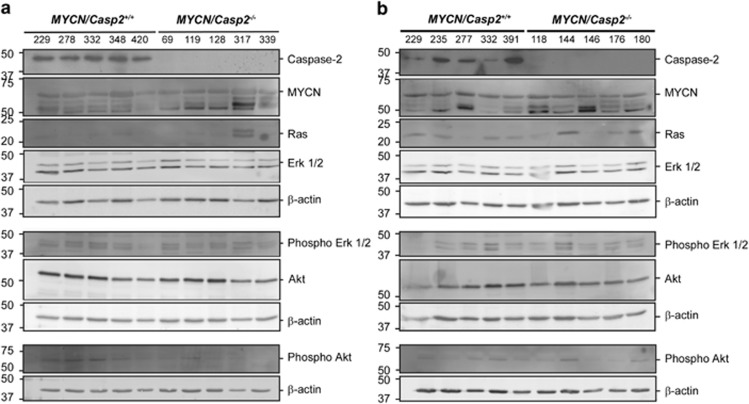

Figure 5.

Ras signaling in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− neuroblastoma. Western blots showing expression levels of MYCN and Ras pathway components; Ras, Erk1/2, phospho-Erk1/2, Akt, phospho-Akt in (a) abdominal and (b) thoracic tumors from TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+ and TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice. Caspase-2 deficiency was validated by western blotting with anti-Caspase-2 antibody. Samples were run on three separate blots, with β-actin shown as a loading control

Ras/MAPK pathway activation in caspase-2-deficient MYCN neuroblastomas

Previous studies have demonstrated that MYCN is tightly regulated at the transcript and protein levels, by Ras signaling.24, 35 We therefore assessed whether there were any differences in Ras pathway signaling and activation in caspase-2-deficient MYCN neuroblastoma, in both thoracic and abdominal samples. Whereas some caspase-2-deficient tumors exhibited increased Ras expression (1/5 abdominal and 2/5 thoracic tumors), this was not significant and we did not detect any significant alterations in activation of downstream pathway components, including Erk1/2 phosphorylation or Akt phosphorylation (Figure 5). Our data therefore indicate that the delayed onset of MYCN-mediated neuroblastoma in caspase-2-deficient mice is not due to altered Ras signaling.

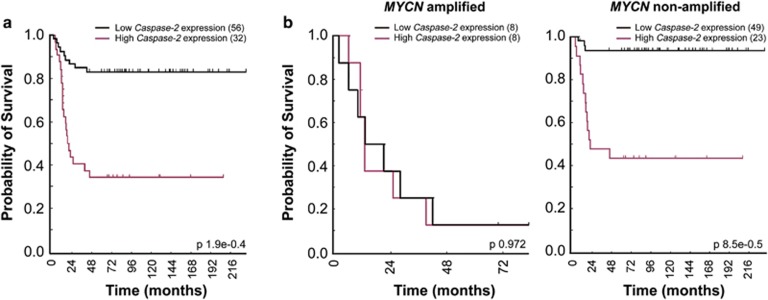

Loss of caspase-2 is associated with increased survival in human neuroblastoma

Our finding that caspase-2 does not act as a tumor suppressor in MYCN-driven neuroblastoma was unexpected and further reinforced the notion that its role in tumor suppression is context- and tissue-specific. To confirm this finding we analyzed publicly available expression array data sets obtained using primary human neuroblastoma tumor samples. Surprisingly, high levels of caspase-2 were strongly predictive of poor neuroblastoma outcome in the overall cohort (P<0.0001; Figure 6a). We analyzed data from MYCN-amplified and non-amplified neuroblastomas separately, and whereas there was only a small subset of MYCN-amplified tumor data available (N=16), there was no correlation between caspase-2 gene expression and outcome in MYCN-amplified human neuroblastomas. Interestingly, there was a significant correlation between low caspase-2 levels and increased survival in MYCN non-amplified human neuroblastoma (Figure 6b). These data are in contrast to the mouse TH-MYCN neuroblastoma data presented here and may indicate that the delayed tumorigenesis observed in caspase-2-deficient TH-MYCN mice may be influenced by additional genetic aberrations.36 These findings are the first report of a role for caspase-2 in neuroblastoma and further emphasize the context-specific role of caspase-2 in tumorigenesis.

Figure 6.

Caspase-2 gene expression is correlated with poor survival in neuroblastoma patients. Event-free survival curves for neuroblastoma patients from publicly available expression array data showing (a) total survival outcome independent of MYCN amplification (n=88) and in (b) subsets of patients with MYCN amplification (n=16) and without MYCN amplification (n=72), showing high caspase-2 expression correlation with poor survival outcome in MYCN non-amplified tumors. P-values using the method of Kaplan–Meier are shown

Discussion

We previously provided the first direct evidence for a tumor suppressor function for caspase-2 using the Eμ-Myc transgenic mouse model.7 Here we utilized TH-MYCN transgenic mice as an alternative MYC-driven mouse tumor model to further investigate the tumor suppressor function of caspase-2 in different tissues. Unexpectedly, we show that deletion of caspase-2 delays neuroblastoma development in the TH-MYCN mouse model. Indicating that loss of caspase-2 may have a somewhat protective function in MYCN-driven neuroblastoma in mice. This conclusion is also supported by Kaplan–Meier survival data showing that high, rather than low, levels of caspase-2 in primary human neuroblastomas are associated with poor outcome.

Caspase-2 strongly suppresses tumorigenesis in the EμMyc B-cell lymphoma model. Given the regulation of c-Myc and MYCN activation and signaling is similar, we hypothesized that caspase-2 may also act as a suppressor of MYCN-mediated tumorigenesis. The finding that caspase-2 does not suppress MYCN-mediated neuroblastoma may indicate a tissue-specific function for caspase-2 and may also provide us with important information on the differential role(s) of caspase-2 in regulating c-Myc- and MYCN-mediated tumorigenesis. There are several key differences between c-Myc- and MYCN-mediated oncogenesis, including (i) MYCN-induced neuroblastoma is primarily an embryonal tumor; (ii) c-Myc and MYCN are differentially expressed during development with MYCN predominantly expressed in undifferentiated neuronal cells of neonatal mice and switched off after birth;37 and (iii) c-Myc and MYCN are differentially regulated at the protein level by Ras and SirT1.24, 38, 39, 40

MYCN amplification and high MYCN protein levels occur in 25% of human neuroblastomas and are essentially associated with poor prognosis in human neuroblastoma.41, 42, 43, 44 MYCN-mediated neuroblastoma onset and progression are strongly associated with expression of the key genes including Odc1, Mrp1, SirT1 and Ras.23, 24, 25 Studies using neuroblastoma cell lines demonstrated that Ras regulates MYCN translation and proteolysis,35, 40 whereas Sirt1 promotes MYCN protein stability and neuroblastoma progression.24, 45, 46 Whereas we observed an increase in Ras protein levels in some caspase-2-deficient MYCN tumors, we did not observe any significant differences in MYCN protein levels, or activation of MAPK pathway components. Therefore, the delay in MYCN-mediated neuroblastoma, in caspase-2-deficient TH-MYCN mice, is unlikely to be caused by altered Ras function. We did not detect any differences in SirT1 mRNA or protein expression and were unable to detect expression of acetylated p53 (an indicator of SirT1 activity) in any of the tumor tissues or neuroblastoma cells from either genotypes; therefore, we cannot rule out a role for SirT1 in the delayed tumorigenesis observed in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice.

The absence of changes in molecular markers associated with neuroblastoma onset and progression, in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumors, may indicate that caspase-2 affects tumor initiation rather than tumor progression. Further support for this suggestion comes from the differences in the pattern of tumor presentation observed in the caspase-2-deficient mice, with TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− tumors being less vascularized and predominantly paraspinal thoracic tumors of the sympathetic ganglia. Angiogenesis has an important role in the progression of neuroblastoma, with tumor vascularity highly correlated with an aggressive and advanced disease phenotype.47, 48 Neuroblastoma is a common embryonal tumor arising from neural crest cells of the sympathetic nervous system and frequently develops in the adrenal medulla. Our findings indicate that the loss of caspase-2 may act to hinder development of adrenal medulla tumors. Together, our findings demonstrate that neuroblastoma development is delayed in TH-MYCN/Casp2−/− mice.

Whereas c-Myc and MYCN can partly compensate for one another in knockout mice,49 their roles are not entirely redundant and their role and regulation in tumorigenesis is distinct.35, 50 An important mediator of c-Myc-induced genomic instability and tumorigenesis is the ARF–Mdm2–p53 tumor suppressor pathway, and many adult tumors with high c-Myc levels have p53 mutations.51 Loss of caspase-2 also results in dysregulated p53 function in c-Myc-driven mouse lymphoma and this is thought to be a driver of genomic instability and accelerated tumorigenesis in this model.6, 7 In contrast, MYCN-mediated neuroblastoma essentially does not present with p53 mutations at the time of diagnosis.44 Our findings also demonstrate that caspase-2-deficient MYCN tumors do not exhibit enhanced aneuploidy. This is consistent with previous findings that genomic instability in casaspe-2-deficient mice is positively associated with tumor onset and progression.6, 9, 10

The role of caspase-2 during embryogenesis in the brain may partly explain its novel function in neuroblastoma. Caspase-2 was originally identified as a neuronally expressed gene that is developmentally downregulated.52, 53 Caspase-2 activation has been shown to inhibit retinoic acid-induced neuronal differentiation,54 which suggests that high caspase-2 expression may promote expansion of undifferentiated neuronal cells. In addition, a role for caspase-2 in apoptosis of sympathetic neurons is unclear. Whereas siRNA depletion of caspase-2 can partly protect sympathetic neurons from death induced by NGF withdrawal,55 caspase-2-deficient sympathetic neurons still undergo apoptosis following factor withdrawal.56, 57 Our data have shown that caspase-2-deficient neuroblastoma cells do not exhibit a defect in apoptosis. Together, these studies indicate that caspase-2 is not essential for apoptosis of neuronal cells, further providing a context-specific function for this caspase.

In summary, this study demonstrates that caspase-2 does not suppress tumor development in the TH-MYCN neuroblastoma model. In contrast, our evidence suggests that caspase-2 expression can be a predictor of survival especially in MYCN non-amplified human neuroblastoma. Our findings are important in that they suggest a tissue- and/or context-specific function for caspase-2 in different tumor models and/or may indicate that caspase-2 may be involved in the differential regulation of c-Myc and MYCN oncogenic signaling pathways.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Casp2−/− mice7, 57 have been described previously and have been backcrossed to a C57BL/6 background for at least 20 generations. 129/SvJ mice transgenic for TH-MYCN have been previously described.19, 58, 59 All animals were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions, and all breeding and tumor observation studies were approved by the SA Pathology/Central Northern Adelaide Health Services Animal Ethics Committee. As the Casp2−/− mice were in a C57BL/6 genetic background, we crossed TH-MYCN hemizygous mice to C57BL/6 wild-type mice to generate TH-MYCN hemizygous mice in a Sv129J;C57BL/6 mixed background and monitored tumor onset and incidence in this mixed background in comparison with the original Sv129J TH-MYCN mice. The TH-MYCN homozygous/Casp2−/− and TH-MYCN homozygous/Casp2+/+ were generated over two separate crosses. First, Casp2−/− C57BL/6 mice were crossed to TH-MYCN transgenic hemizygous Sv129J;C57BL/6 mice and the resulting TH-MYCN hemizygous/Casp2+/− pups were then intercrossed to obtain TH-MYCN homozygous/Casp2−/− (TH-MYCN/Casp2−/−) and TH-MYCN homozygous/Casp2+/+ (TH-MYCN/Casp2+/+) littermates in a mixed Sv129/C57BL/6 background. Mice were genotyped for the presence of MYCN transgene and loss of the Casp2 gene using primers is listed in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Mice were monitored for tumors by palpation and humanely killed at the onset of pathological signs of tumor burden (hunching, poor mobility). Cause of death was determined by autopsy. Mice that did not develop tumors after 12 months were also humanely killed and autopsied.

Histology

Mouse tissues were collected and either snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70 °C or were fixed in formalin. Fixed specimens were embedded in paraffin, sectioned (7 μm) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Real-time q-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from frozen neuroblastoma tissue using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reverse-transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA, USA) and oligo-dT primers. Real-time qPCR was performed on a Rotor-Gene 3000 (Corbett Research, Mortlake, NSW, Australia) using RT2 Real-Time SYBR Green/ROX PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Each gene was analyzed in two independent qPCR runs. Gene expression was normalized to β-actin using the 2−ΔΔCt method. See Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary Information for primer sequences.

PCNA and TUNEL immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded thymic lymphoma sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanol series. Endogenous peroxidase activity and nonspecific protein sites were blocked with 3% H2O2/PBS and 5% fetal bovine serum/PBS-T, respectively. For PCNA staining, tissue sections were incubated with anti-PCNA antibody (clone PC10, Cell Signalling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) diluted 1 : 250 in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C. Tissue sections were incubated with anti-mouse biotinylated secondary antibody (1 : 250 in blocking solution; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) and Avidin/Biotin Complex (ABC) reagent (VectaStain, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) at room temperature. For TUNEL staining, tissue sections were treated with 20 μg/ml proteinase K (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and endogenous peroxidase activity and nonspecific protein sites were blocked with 1% v/v H2O2/PBS followed by washing in TBS (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0). Sections were pre-incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) buffer (30 mM Tris pH 7.2, 140 mM sodium cacodylate, 1 mM cobalt chloride), followed by reaction buffer containing 135 units/ml TdT enzyme (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and 9 μM biotinylated 16-dUTP in TdT buffer at 37 °C. Negative control reactions without TdT enzyme were included for each tissue section. Sections were treated with a saline sodium citrate buffer (300 mM NaCl, 30 mM sodium citrate) to terminate reactions and then were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin (VectaStain). For color development, peroxidase substrate (3, 3'-diaminobenzidine) was added, followed by counterstaining with Mayer's hematoxylin solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Tissue sections were then dehydrated in graded ethanol series and coverslips were mounted using DePex mounting media. Digital images were acquired using a NanoZoomer (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan).

Immunoblotting

Protein lysates were prepared from primary neuroblastoma cells or from tumor tissue by cell lysis and/or homogenization in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% nonyl-phenoxylpolyethoxylethanol (NP-40), 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in the presence of protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Homogenates were further treated by three freeze/thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen, clarified by centrifugation at 16 000 × g for 15 min and protein concentration determined by the BCA quantification (Pierce Biotechnology Inc, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For immunoblot analysis, 50 μg of lysates were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membrane and probed for the specified antibody for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibodies, conjugated with HRP (GE Healthcare), alkaline phosphatase (AP, Millipore) or Cy5 (GE Healthcare), were incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Proteins were visualized using ECF or ECL (Amersham, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The following primary antibodies were used: N-MYC-(2) and p21 (F5) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); Ras (27H5), p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (137F5), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (D13.14.4E), Akt (pan) (C67E7), Phospho-Akt (Ser473) (D9E) (Cell Signalling Technology), caspase-2 (clone 11B4), β-actin (Sigma).

Statistical analysis of data

Graph Pad Prism software, version 5 (Graph Pad Inc, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analysis. Log-rank and Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon tests with Kaplan–Meier analysis were used for comparison of mouse survival. Student's t-test or χ2 tests were used for all other analysis unless otherwise stated. Data are expressed as mean±S.E.M. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the SA Pathology animal resource facility for help in maintaining the mouse strains, and members of our laboratory for helpful comments. This work was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia project grant (1043057), and Association for International Cancer Research (AICR) project grant (13–1015), a South Australian Cancer Collaborative Fellowship to LD and a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (1002863) to SK.

Glossary

- MRP

multidrug resistance protein

- MYCN

neuroblastoma-derived viral-related avian myelocytomatosis v-Myc oncogene

- ODC1

ornithine decarboxylase

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by G Melino

Supplementary Material

References

- Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. Caspase 2 in apoptosis, the DNA damage response and tumour suppression: enigma no more. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nrc2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Tschopp J. Inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes: master switches of inflammation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:10–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanlangenakker N, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. Many stimuli pull the necrotic trigger, an overview. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:75–86. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho LH, Read SH, Dorstyn L, Lambrusco L, Kumar S. Caspase-2 is required for cell death induced by cytoskeletal disruption. Oncogene. 2008;27:3393–3404. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorstyn L, Puccini J, Wilson CH, Shalini S, Nicola M, Moore S, et al. Caspase-2 deficiency promotes aberrant DNA-damage response and genetic instability. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1288–1298. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho LH, Taylor R, Dorstyn L, Cakouros D, Bouillet P, Kumar S. A tumor suppressor function for caspase-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5336–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811928106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalini S, Dorstyn L, Wilson C, Puccini J, Ho L, Kumar S. Impaired antioxidant defence and accumulation of oxidative stress in caspase-2-deficient mice. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1370–1380. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MJ, McCormick L, Janke L, Howard A, Bouchier-Hayes L, Green DR. Genetic deletion of caspase-2 accelerates MMTV/c-neu-driven mammary carcinogenesis in mice. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:1174–1182. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puccini J, Shalini S, Voss AK, Gatei M, Wilson CH, Hiwase DK, et al. Loss of caspase-2 augments lymphomagenesis and enhances genomic instability in Atm-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:19920–19925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311947110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrini S, Gorgoulis VG, Halazonetis TD. Genomic instability—an evolving hallmark of cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:220–228. doi: 10.1038/nrm2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Mannava S, Grachtchouk V, Zhuang D, Soengas MS, Gudkov AV, et al. c-Myc depletion inhibits proliferation of human tumor cells at various stages of the cell cycle. Oncogene. 2008;27:1905–1915. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochownik EV, Li Y. The ever expanding role for c-Myc in promoting genomic instability. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1024–1029. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.9.4161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfer A, Ramaswamy S. Prognostic signatures, cancer metastasis and MYC. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3639. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.18.13220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JM, Harris AW, Pinkert CA, Corcoran LM, Alexander WS, Cory S, et al. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature. 1985;318:533–538. doi: 10.1038/318533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes NE, Lane HA. Myc and mammary cancer: Myc is a downstream effector of the ErbB2 receptor tyrosine kinase. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2001;6:141–150. doi: 10.1023/a:1009528918064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve RM, Sutterluty H, Pullen N, Lane HA, Daly JM, Krek W, et al. Effects of oncogenic ErbB2 on G1 cell cycle regulators in breast tumour cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:1647–1656. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane HA, Beuvink I, Motoyama AB, Daly JM, Neve RM, Hynes NE. ErbB2 potentiates breast tumor proliferation through modulation of p27(Kip1)-Cdk2 complex formation: receptor overexpression does not determine growth dependency. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3210–3223. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3210-3223.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss WA, Aldape K, Mohapatra G, Feuerstein BG, Bishop JM. Targeted expression of MYCN causes neuroblastoma in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 1997;16:2985–2995. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris JM, Matthay KK. Molecular biology of neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2264–2279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur GM. Neuroblastoma: biological insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:203–216. doi: 10.1038/nrc1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson WC, Weiss WA. Myc proteins as therapeutic targets. Oncogene. 2010;29:1249–1259. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty MD, Norris MD, Davis K, Liu X, Evageliou NF, Hayes CS, et al. ODC1 is a critical determinant of MYCN oncogenesis and a therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9735–9745. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GM, Liu PY, Gherardi S, Scarlett CJ, Bedalov A, Xu N, et al. SIRT1 promotes N-Myc oncogenesis through a positive feedback loop involving the effects of MKP3 and ERK on N-Myc protein stability. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris MD, Burkhart CA, Marshall GM, Weiss WA, Haber M. Expression of N-myc and MRP genes and their relationship to N-myc gene dosage and tumor formation in a murine neuroblastoma model. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;35:585–589. doi: 10.1002/1096-911x(20001201)35:6<585::aid-mpo20>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupack DG, Teitz T, Potter MD, Mikolon D, Houghton PJ, Kidd VJ, et al. Potentiation of neuroblastoma metastasis by loss of caspase-8. Nature. 2006;439:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nature04323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitz T, Inoue M, Valentine MB, Zhu K, Rehg JE, Zhao W, et al. Th-MYCN mice with caspase-8 deficiency develop advanced neuroblastoma with bone marrow metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4086–4097. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzl C, Peintner L, Krumschnabel G, Bock F, Labi V, Drach M, et al. PIDDosome-independent tumor suppression by Caspase-2. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1722–1732. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson MJ, Haber M, Porro A, Munoz MA, Iraci N, Xue C, et al. ABCC multidrug transporters in childhood neuroblastoma: clinical and biological effects independent of cytotoxic drug efflux. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1236–1251. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puccini J, Dorstyn L, Kumar S. Genetic background and tumour susceptibility in mouse models. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:964. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore HC, Wood KM, Jackson MS, Lastowska MA, Hall D, Imrie H, et al. Histological profile of tumours from MYCN transgenic mice. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:1098–1103. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.054627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AJ, Cheng NC, Ford J, Smith J, Murray JE, Flemming C, et al. Cell lines from MYCN transgenic murine tumours reflect the molecular and biological characteristics of human neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1467–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack A, Chen Z, Tonelli R, Pule M, Hunt L, Pession A, et al. The p53 regulatory gene MDM2 is a direct transcriptional target of MYCN in neuroblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:731–736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405495102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarbrick A, Woods SL, Shaw A, Balakrishnan A, Phua Y, Nguyen A, et al. miR-380-5p represses p53 to control cellular survival and is associated with poor outcome in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. Nat Med. 2010;16:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/nm.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapeli K, Hurlin PJ. Differential regulation of N-Myc and c-Myc synthesis, degradation, and transcriptional activity by the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:38498–38508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.276675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmuson A, Segerstrom L, Nethander M, Finnman J, Elfman LH, Javanmardi N, et al. Tumor development, growth characteristics and spectrum of genetic aberrations in the TH-MYCN mouse model of neuroblastoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman KA, Yancopoulos GD, Collum RG, Smith RK, Kohl NE, Denis KA, et al. Differential expression of myc family genes during murine development. Nature. 1986;319:780–783. doi: 10.1038/319780a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears R, Nuckolls F, Haura E, Taya Y, Tamai K, Nevins JR. Multiple Ras-dependent phosphorylation pathways regulate Myc protein stability. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2501–2514. doi: 10.1101/gad.836800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Minter-Dykhouse K, Lou Z. A c-Myc-SIRT1 feedback loop regulates cell growth and transformation. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:203–211. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaari S, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Haklai R, Rechavi G, Kloog Y. Disruption of cooperation between Ras and MycN in human neuroblastoma cells promotes growth arrest. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4321–4330. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HS, Gallie BL, DeBoer G, Haddad G, Ikegaki N, Dimitroulakos J, et al. MYCN protein expression as a predictor of neuroblastoma prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:1699–1706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JF, van Bokhoven H, van Leeuwen FN, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa CA, de Vries IJ, Adema GJ, et al. Regulation of MYCN expression in human neuroblastoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:239. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentijn LJ, Koster J, Haneveld F, Aissa RA, van Sluis P, Broekmans ME, et al. Functional MYCN signature predicts outcome of neuroblastoma irrespective of MYCN amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:19190–19195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208215109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung NK, Dyer MA. Neuroblastoma: developmental biology, cancer genomics and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nrc3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler L, Schlieve C, Goldenberg DD, Kenney A, Kim G, McMillan A, et al. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase destabilizes Mycn protein and blocks malignant progression in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8139–8146. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney AM, Widlund HR, Rowitch DH. Hedgehog and PI-3 kinase signaling converge on Nmyc1 to promote cell cycle progression in cerebellar neuronal precursors. Development. 2004;131:217–228. doi: 10.1242/dev.00891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meitar D, Crawford SE, Rademaker AW, Cohn SL. Tumor angiogenesis correlates with metastatic disease, N-myc amplification, and poor outcome in human neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:405–414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Vacca A, Nico B, De Falco G, Giuseppe Montaldo P, Ponzoni M. Angiogenesis and anti-angiogenesis in neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:750–757. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malynn BA, de Alboran IM, O'Hagan RC, Bronson R, Davidson L, DePinho RA, et al. N-myc can functionally replace c-myc in murine development, cellular growth, and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1390–1399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbit CE, Tersak JM, Prochownik EV. MYC oncogenes and human neoplastic disease. Oncogene. 1999;18:3004–3016. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin XY, Grove L, Datta NS, Long MW, Prochownik EV. C-myc overexpression and p53 loss cooperate to promote genomic instability. Oncogene. 1999;18:1177–1184. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tomooka Y, Noda M. Identification of a set of genes with developmentally down-regulated expression in the mouse brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;185:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91747-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Kinoshita M, Noda M, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Induction of apoptosis by the mouse Nedd2 gene, which encodes a protein similar to the product of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell death gene ced-3 and the mammalian IL-1 beta-converting enzyme. Genes Dev. 1994;1994;8:1613–1626. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.14.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistritto G, Papaleo V, Sanchez P, Ceci C, Barbaccia ML. Divergent modulation of neuronal differentiation by caspase-2 and -9. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen M, Ham J. Programmed cell death during neuronal development: the sympathetic neuron model. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:1025–1035. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron L, Perez GI, Macdonald G, Shi L, Sun Y, Jurisicova A, et al. Defects in regulation of apoptosis in caspase-2-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1304–1314. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly LA, Ekert P, Harvey N, Marsden V, Cullen L, Vaux DL, et al. Caspase-2 is not required for thymocyte or neuronal apoptosis even though cleavage of caspase-2 is dependent on both Apaf-1 and caspase-9. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:832–841. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart CA, Cheng AJ, Madafiglio J, Kavallaris M, Mili M, Marshall GM, et al. Effects of MYCN antisense oligonucleotide administration on tumorigenesis in a murine model of neuroblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1394–1403. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansford LM, Thomas WD, Keating JM, Burkhart CA, Peaston AE, Norris MD, et al. Mechanisms of embryonal tumor initiation: distinct roles for MycN expression and MYCN amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12664–12669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401083101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.