Abstract

Background and Objectives

Gender differences in illicit drug use patterns and related harms (e.g. HIV infection) are becoming increasingly recognized. However, little research has examined gender differences in risk factors for initiation into injecting drug use. We undertook this study to examine the relationship between gender and risk of injection initiation among street-involved youth and to determine whether risk factors for initiation differed between genders.

Methods

From September 2005 to November 2011, youth were enrolled into the At-Risk Youth Study, a cohort of street-involved youth aged 14-26 in Vancouver, Canada. Cox regression analyses were used to assess variables associated with injection initiation and stratified analyses considered risk factors for injection initiation among male and female participants separately.

Results

Among 422 street-involved youth, 133 (32.5%) were female, and 77 individuals initiated injection over study follow-up. Although rates of injection initiation were similar between male and female youth (p =0.531), stratified analyses demonstrated that, among male youth, risk factors for injection initiation included sex work (Adjusted Hazard Ratio [AHR] =4.74, 95% Confidence Intervals [CI]: 1.45–15.5) and residence within the city's drug use epicentre (AHR =1.95, 95% CI: 1.12–3.41), whereas among female youth, non-injection crystal methamphetamine use (AHR =4.63, 95% CI: 1.89– 11.35) was positively associated with subsequent injection initiation.

Conclusion

Although rates of initiation into injecting drug use were similar for male and female street youth, the risk factors for initiation were distinct. These findings suggest a possible benefit of uniquely tailoring prevention efforts to high-risk males and females.

Keywords: Injection initiation, street youth, gender, sex work, crystal methamphetamine

INTRODUCTION

Injection drug use is a major risk factor for acquiring various communicable diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C (HCV) (1-2). In addition, injection drug use is associated with other poor health outcomes such as soft tissue infections including infective endocarditis as well as fatal drug overdose (3,4,5). In North America, injection drug use amongst street-involved youth is highly prevalent. In the U.S., 30% of street youth have reported using injection drugs at least once and in Canada rates reported are as high as 40% (6,7). In addition, new users are more likely to engage in risky behaviours, like sharing needles, putting them at heightened risk of acquiring HIV and HCV (8).

To inform prevention efforts, identifying factors that put youth at risk for initiating injection is critical. Previously described risk factors associated with initiation into injection drug use include homelessness, early onset drug use, specific drug use patterns and parental substance use (9,10,11). However, the intersection of gender and injection initiation is less understood. We therefore undertook the present study to assess the potential relationship between injection initiation and gender, as well as explore if there were unique risk factors for injection initiation between genders, among a community-recruited cohort of street-involved youth in Vancouver, Canada.

METHOD

Data for this study was obtained from the At-Risk Youth Study (ARYS), which is a prospective cohort study of street-involved youth in Vancouver, Canada that began in 2005 and has been described in detail previously (12). The ARYS study's primary objective is to assess risk factors for initiation into injecting drug use. However, the study examines a host of other secondary outcomes including risk for infectious diseases and all participants receive HVC and HIV screening at baseline and semi-annually. In brief, participants were recruited through snowball sampling and extensive street-based outreach methods. Although no explicit inclusion criterion required that youth spend a minimum amount of time on the street or actually live on the street to qualify for the study, in practice, the street-based recruitment produced a sample of youth who spent extensive time on the street, a large proportion of whom were homeless. Still, because our study lacked an explicit requirement that youth live on the street, we use throughout the present manuscript the term “street-involved youth” rather than “street youth”, since the latter of these terms is generally applied to youth known to live full-time or part-time on the street. To be eligible, participants at recruitment must be age 14-26 years, use illicit drugs other than marijuana in the past 30 days, and provide written informed consent. At enrollment and on a bi-annual basis participants complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire that includes questions related to demographic information and drug use patterns and are assessed by a study nurse who examines for stigmata of drug injecting. The questionnaire and derived variables were defined based on earlier studies of street involved and adult drug users (13,14). At each study visit participants are provided with a stipend ($20 CDN) for their time. The study has been approved by the University of British Columbia's Research Ethics Board.

The study period for the current analysis was September 2005 to November 2011. Data from all participants who had never injected drugs at enrolment and had completed at least one follow-up visit during the study period, to assess for subsequent injecting initiation, were eligible for inclusion in the present analyses. The primary outcome of interest was time to initiation of injection drug use and the primary explanatory variable of interest was gender. To determine whether there was a significant relationship between our outcome of interest and our primary explanatory variable we a priori selected a range of secondary explanatory variables we hypothesized might be associated with both injection initiation and gender. Secondary explanatory factors included: age (per year older); ethnicity (Caucasian vs. other); daily consumption of alcohol (daily alcohol use vs. less than daily); Marijuana use (yes vs. no); non-injection cocaine use (yes vs. no); crack cocaine smoking (yes vs. no); non-injection crystal methamphetamine use (yes vs. no); non-injection heroin use (yes vs. no); sex work, defined as exchanging sex for money, drugs, or gifts (yes vs. no); homelessness, defined as having no fixed address, sleeping on the street, couch surfing, or staying in a shelter or hostel (yes vs. no); and residence in Vancouver's drug use epicenter, which is a well-described and defined area of the city referred to as the Downtown Eastside (yes vs. no). All drug and alcohol use related variables refer to circumstances and behaviors over the previous six months and were treated as time-updated covariates on the basis of semi annual follow-up data. In addition, to protect against reverse causation whereby reported behaviours were a consequence of drug injecting, all substance use variables were lagged to the previous available observation. In this way, we were able to assess behaviors that were reported prior to the injecting initiation event (15). Since participants could have varying durations between their last injecting naive and their first interview where they report injecting, the date of first injection was estimated as the midpoint between the first injecting naive follow up and the follow up visit where injecting was reported. Participants were censored at the date of their last follow up visit.

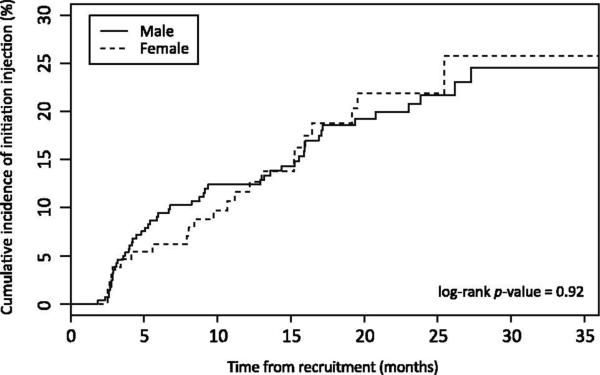

To assess the relationship between gender and injection initiation, as a first step we presented the characteristics of the study sample stratified by gender. We then calculated the cumulative incidence of injection initiation for male and female participants over study follow-up using Kaplan-Meier methods. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test.

Using Cox regression, we then estimated the unadjusted relative hazards and 95% confidence intervals for factors associated with injection initiation in the overall sample. To fit our multivariate Cox models, we used a backwards selection process previously described by Maldonado and Greenland (16) and Rothman and Greenland (17). Specifically, we began with all explanatory variables of interest in a full model. Using an automated procedure, we subsequently generated a series of confounding models by removing each secondary explanatory variable one at a time. For each of these models we assessed the relative change in the coefficient for our primary explanatory variable of interest (gender). The secondary explanatory variable of interest that resulted in the smallest absolute relative change in the coefficient for gender was then removed. Secondary variables continued to be removed through this process until the smallest relative change in the coefficient for the effect of gender on injection initiation exceeded 5% of the value of the coefficient. Remaining variables were considered confounders and were included in the final multivariate analysis.

We then assessed factors associated with injection initiation among male and female youth separately in stratified analyses. The same variables of interests were considered and two separate multivariate cox regressions were constructed. Model selection was done based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) with the best subset selection procedure. This provided a computationally efficient method to screen all possible combinations of candidate variables and identify the model with the best overall fit as indicated by the lowest AIC value (18). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). All tests of significance were two-sided.

RESULTS

Overall, 991 street-involved youth were recruited into the ARYS cohort between December 1, 2005 and May 31, 2011. At enrolment 390 (39.3%) participants reported having engaged in injection drug use, and among the overall sample of 991 street involved youth, gender was not significantly associated with injecting (Odds Ratio = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.74 –1.29). Among the 601 (61%) individuals who had never injected at baseline, 422 (70%) completed at least one study follow-up. In comparison to the 422 youth who represented the eligible study population, the 179 injecting naïve youth who were ineligible for the present study because they did not have a follow up visit, were more likely to be white (p = 0.020), and less likely to be older (p = 0.003), but no difference for males gender (p = 0.744). Those youth who were ineligible because they had already begun injecting were more likely to be older (p < 0.001) and white (p = 0.003), but there was no difference by gender (p > 0.995). Since participants were recruited between 2005 and 2011, and participants recruited earlier would have a longer duration under follow up to initiate injecting, we assessed if year of recruitment was associated with initiating injecting and found that it was not (p = 0.147). We also found that duration of follow up was not associated with initiation (p = 0.589).

Among the sample of 422 participants included in the study, 133 (31.5%) were female, the median age was 22 (interquartile range [IQR]= 20-23), and the median follow-up time was 20.6 months (IQR= 12.6-26.1). As shown in Table 1, male and female participants differed based on mean age, engagement in sex work, and marijuana use (all p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of injection-naïve street-involved youth in Vancouver, Canada stratified by gender, September 2005–November 2011 (N = 422).

| Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total (%) (N = 422) | Male (%) (n = 289) | Female (%) (n = 133) | p Value |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||

| Mean age (IQR) | 22 (20–23) | 22 (20–23) | 21 (18–22) | <0.001 |

| Caucasian | 258 (61) | 180 (62) | 78 (59) | 0.476 |

| Sex worka | 20 (5) | 7 (2) | 13 (10) | 0.001 |

| Homelessa | 296 (70) | 210 (73) | 86 (65) | 0.951 |

| Downtown Eastside Residencya | 98 (23) | 64 (22) | 34 (26) | 0.440 |

| Drug use-related behaviors | ||||

| Daily alcohol usea | 73 (17) | 47 (16) | 26 (20) | 0.407 |

| Marijuana usea | 380 (90) | 271 (94) | 109 (82) | <0.001 |

| Non-injection cocaine usea | 206 (49) | 144 (50) | 62 (47) | 0.540 |

| Crack cocaine smokinga | 236 (56) | 166 (57) | 70 (53) | 0.355 |

| Non-injection crystal methamphetamine usea | 148 (35) | 96 (33) | 52 (39) | 0.240 |

| Non-injection heroin usea | 66 (16) | 42 (15) | 24 (18) | 0.356 |

| Injection drug use | ||||

| Initiated during follow-ups | 77 (18) | 54 (18) | 23 (17) | 0.731 |

IQR, interquartile range

Denotes behavior in the preceding 6 months

Over study follow-up, 77 (18%) injection initiation events were observed for an incidence density of 10.28 per 100 person years (95% CI 7.98 – 12.58). The Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative incidence of injection initiation stratified by gender are shown in Figure 1. As shown here, male participants were at no higher risk of injection initiation compared with female participants (log rank p = 0.92). The cumulative incidence of injection drug use among female participants reached 25.7% over the 3-year follow-up period compared to 24.6% among male participants.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of injection initiation among street-involved male and female youth residing in Vancouver, Canada, September 2005–November 2011 (n = 422).

Table 2 shows the unadjusted and adjusted relative hazards of injection initiation. In univariate Cox analysis, gender was not significantly associated with time to first injection drug use [relative hazards (RH) =1.03, 95% CI: 0.63–1.67]. In multivariate Cox regression analyses, gender remained insignificant [adjusted relative hazards (ARH) =1.29, 95% CI: 0.75-2.24]. Table 3 shows the multivariate cox regressions for factors associated with initiation of injection drug use stratified by gender. Among male youth, sex work (AHR = 4.74, 95% CI: 1.45 – 15.5) and Downtown Eastside residence (AHR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.12 – 3.41), were positively associated with subsequent injections. Among female youth, non-injection crystal methamphetamine use (AHR = 4.63, 95% CI: 1.89 – 11.35) was positively associated with subsequent injection initiation.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for factors associated with initiation of injection drug use among street-involved youth in Vancouver, Canada, September 2005–November 2011 (N = 422).

| Characteristic | Unadjusted HRa (95% CIb) | p Value | Adjusted HRa (95% CIb) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender (vs. female) | 1.03 (0.63–1.67) | 0.920 | 1.29 (0.75–2.24) | 0.359 |

| Age (per year older at baseline) | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) | 0.300 | 0.91 (0.83–1.01) | 0.065 |

| Caucasian (vs. other) | 1.50 (0.92–2.44) | 0.104 | 1.52 (0.91–2.52) | 0.108 |

| Daily alcohol usec,d (yes vs. no) | 0.99 (0.55–1.80) | 0.982 | ||

| Marijuana usec,d (yes vs. no) | 0.87 (0.47–1.61) | 0.653 | 0.82 (0.43–1.57) | 0.544 |

| Non-injection cocaine usec,d (yes vs. no) | 0.99 (0.62–1.57) | 0.964 | ||

| Crack cocaine smokingc,d (yes vs. no) | 1.38 (0.88–2.18) | 0.164 | 1.28 (0.78–2.09) | 0.327 |

| Non-injeciton crystal meth usec,d (yes vs. no) | 1.83 (1.16–2.87) | 0.009 | 1.82 (1.15–2.89) | 0.011 |

| Non-injection heroin usec,d (yes vs. no) | 1.83 (1.06–3.14) | 0.029 | ||

| Sex workd (yes vs. no) | 2.25 (0.97–5.18) | 0.058 | 1.86 (0.75–4.61) | 0.183 |

| Homelessd (yes vs. no) | 1.80 (1.13–2.88) | 0.013 | 1.59 (0.99–2.57) | 0.057 |

| Downtown Eastside Residenced (yes vs. no) | 1.80 (1.13–2.88) | 0.014 | 1.94 (1.18–3.21) | 0.010 |

HR, Hazard Ratio

CI, Confidence Interval

Lagged to previous follow-up

Denotes behavior in the preceding 6 months

Table 3.

Multivariate cox regressions for factors associated with initiation of injection drug use among female and male street-involved youth in Vancouver, Canada, September 2005–November 2011 (N = 422).

| Characteristic | Adjusted HRa (95% CIb) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Model I: Male gender | ||

| Homelessd (yes vs. no) | 1.73 (0.98–3.06) | 0.058 |

| Sex workd (yes vs. no) | 4.74 (1.45–15.5) | 0.010 |

| Downtown Eastside residencyd (yes vs. no) | 1.95 (1.12–3.41) | 0.018 |

| Model II: Female gender | ||

| Homelessd (yes vs. no) | 1.79 (0.76–4.21) | 0.185 |

| Non-injection crystal meth usec,d (yes vs. no) | 4.63 (1.89–11.35) | 0.001 |

| Crack cocaine smokingc,d (yes vs. no) | 1.79 (0.73–4.41) | 0.202 |

| Non-injection heroine usec,d (yes vs. no) | 1.66 (0.62–4.44) | 0.309 |

HR, Hazard Ratio

CI, Confidence Interval

Lagged to previous follow-up

Denotes behavior in the preceding 6 months

DISCUSSION

Among the 422 street-involved youth in our study, we observed that rates of initiation into injection drug use for males and females were not significantly different. However, the risk factors for initiation were distinct between genders. For male street youth, risk factors for injection initiation included sex work and residence in the Downtown Eastside, Vancouver's drug use epicenter. For female street youth, non-injection methamphetamine was positively associated with subsequent injection initiation.

Interestingly, our findings differ from an earlier study from our setting that examined patterns of injecting initiation among Aboriginal youth. This study found that Aboriginal female youth were two times more likely to initiate injection compared to males (19). This suggests that the relationship between gender and injection initiation may differ among various sub-populations of vulnerable youth. Similar to our analysis, studies among other populations of at-risk youth have found female youth are no more likely to initiate injection compared to their male counterparts (9,20). Also consistent with our analysis, a prior study of injection initiation among street-involved youth in Montreal found that risk factors vary between genders (21). However, the risk factors associated with injection initiation among male and female youth in our setting contrast with prior studies. In particular, specific drugs associated with injection initiation among street-involved youth in Montreal, Canada were no different between genders (9,21), while non-injection crystal methamphetamine use was a unique risk factor for females in our study. However, it should be noted that crystal methamphetamine use has been reported to be significantly higher on the west coast of North America, which may explain these differences (22).

Furthermore, the absence of a significant association between non-injection crystal methamphetamine use and injection initiation among male youth is noteworthy and may have important implications for injection prevention efforts involving targeting drug treatment and other public health measures. Previous studies suggest that crystal methamphetamine is a key risk factor for injection drug use among street-involved youth in our setting (15,23). However, our findings indicate that crystal methamphetamine may be uniquely risky for female youth. The association between methamphetamine use and initiation into injecting among female street youth is interesting. Although further research is necessary, one potential explanation for this finding may be that women appear more dependent on methamphetamine than men, use higher amounts of drug, and are more likely to have it as their primary drug of choice (24). Further examination of this phenomenon is warranted.

The association between sex work and injection initiation among males shown in our study is novel. Although young males involved in sex work are known to be at high risk for HIV (25,26), and there is an established relationship between sex work and injection drug use (27,28), this is the first injection initiation incidence study to our knowledge that explicitly links sex work with injection initiation among male street-involved youth. However, given the low reported prevalence of sex work among male youth in our sample, this relationship would benefit from further study.

Highlighting differences between gender is important for public health interventions so they can be properly structured to appropriately serve the targeted population. Although no evidence-based interventions to reduce initiation into injection drug use have been identified, there are opportunities to tailor substance abuse treatment programs to cater to the unique needs of women versus men (29). Similarly, our findings suggest that physicians who care for street-involved youth should be aware that female street youth using methamphetamine may be at particularly high risk of initiating injecting.

There are several limitations to our study. First, as with other studies of street-involved youth, the ARYS cohort is not a random sample and therefore these findings may not generalize to other street youth populations. We should also note that our study sample of youth contained a predominance of older participants, with a median age of 22 years. Our study was largely consistent with the World Health Organization, which applies the term ‘youth’ to young people within the age range 15 to 24 years, and with most other studies, which generally include participants close to and within this range. However, our results should be interpreted with the knowledge that our sample may be slightly older on average than other studies examining street youth. Second, this study is based on self-reported information and is susceptible to recall bias and socially desirable responding (30). It is possible, despite our efforts to engage in a nonjudgmental way that participants underreported illegal activities or those perceived as socially unacceptable. Another limitation is that the survey's design required that a number of variables were dichotomized into yes versus no, and future studies would benefit by seeking to delve deeper into the frequency of the impact of certain behaviours, such as alcohol and other drug use. Finally, for some variables, such as sex work, there were low rates of reporting this activity, which may have contributed to a Type II error when some of these factors were considered. In addition, we found that white participants were more likely to be lost to follow up. We attempted to address this by adjusting for ethnicity in our analyses, however, there may nevertheless have been unmeasured confounding.

In summary, the present study showed no difference between rates of initiation into injection drug use between male and female street youth, however, the risk factors for each gender were distinct suggesting that injection prevention efforts may benefit from considering the unique characteristics and vulnerabilities of female and male street-involved youth. Given the serious health harms and vulnerabilities experienced by this population, evidence-based interventions are needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the ARYS study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. We would specifically like to thank Cody Callon, Jennifer Matthews, Deborah Graham, Peter Vann, Steve Kain, Tricia Collingham, and Carmen Rock for their research and administrative assistance.

Funding: The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA028532) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP–102742). This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program through a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Inner City Medicine, which supports Dr. Evan Wood. Dr. Kora DeBeck is supported by a MSFHR/St. Paul's Hospital - Providence Health Care Career Scholar Award. Funding sources had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [April 4, 2013];HIV Transmission. 2010 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/qa/transmission.htm.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [April 4, 2013];Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection and HCV-Related Chronic Disease. 1998 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00055154.htm.

- 3.Lloyd-Smith E, Wood E, Zhang R, Tyndall MW, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Risk factors for developing a cutaneous injection-related infection among injection drug users: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):405. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milloy M-J, Kerr T, Tyndall M, Montaner J, Wood E. Estimated drug overdose deaths averted by North America's first medically-supervised safer injection facility. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(10):e3351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millar BC, Moore JE. Emerging issues in infective endocarditis. [April 4, 2013];Emerg Infect Dis. 2004 Jun. doi: 10.3201/eid1006.030848. Available from: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/10/6/03-0848.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Clatts MC, Davis WR, Sotheran JL, Atillasoy A. Correlates and distribution of HIV risk behaviors among homeless youths in New York City: implications for prevention and policy. Child Welfare. 1998;77:195–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy E, Haley N, LeClerc P, Lemire N, Boivin JF, Frappier JY. Prevalence of HIV infection and risk behaviours among Montreal street youth. Int J of STD AIDS. 2000;11:241–247. doi: 10.1258/0956462001915778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novellia LA, Shermana SG, Havensb JR, Strathdeec SA, Sapuna M. Circumstances surrounding the first injection experience and their association with future syringe sharing behaviors in young urban injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy É , Haley N, Leclerc P, Cédras L, Blais L, Boivin J-F. Drug injection among street youths in Montreal: Predictors of initiation. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80:92–105. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Arria AM, Ompad DC, Garfein R, Strathdee SA. Factors associated with adolescent initiation of injection drug use. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(Suppl 1):136–145. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kipke MD, Unger JB, Palmer RF, Edgington R. Drug use, needle sharing and HIV risk among injection drug-using street youth. Subst Use Misuse. 1996;31:1167–1187. doi: 10.3109/10826089609063971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood E, Stoltz JA, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: the ARYS Study. Harm Reduct J. 2006;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy E, Arruda N, Leclerc P, Haley N, Bruneau J, Boivin JF. Injection of drug residue as a potential risk factor for HVC acquisition among Montreal young injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL, Cornelisse PGA, Rekart ML, Montaner JSG, Schechter MT, O'Shaughnessy MV. Needle exchange is not enough: lessons from the Vancouver injection drug use study. AIDS. 1997;11:F59–F65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng C, DeBeck K, Kerr T, Mathias S, Montaner J, Wood E. Homelessness independently predicts injection drug use initiation among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(4):499–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138(11):923–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothman K, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. Lippincott; Philadelphia, Pa: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shtatland ES, Cain E, Barton MB. SUGI ‘26 Proceedings. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 2001. The perils of stepwise logistic regression and how to escape them using information criteria and the output delivery system. paper 222–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller CL, Pearce ME, Moniruzzaman A, Thomas V, Christian W, Schechter MT, Spittal PM. The Cedar Project: risk factors for transmission to injection drug use among young, urban Aboriginal people. CMAJ. 2011;183:1147–1154. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuller CM, Vlahov D, Arria AM, Ompad DC, Garfein R, Strathdee SA. Factors associated with adolescent initiation of injection drug use. Public Health Rep. 2001;91:753–760. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy E, Boivin JF, Leclerc P. Initiation to drug injection among street youth: a gender-based analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;114:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Public Health Agency of Canada [July 26, 2013];EPI-UPDATE: Crystal methamphetamine use among Canadian street-involved youth (1999-2005) Available at http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca.

- 23.Wood E, Stoltz JA, Zhang R, Strathdee SA, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Circumstances of first crystal methamphetamine use and initiation of injection drug use among high-risk youth. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27(3):270–276. doi: 10.1080/09595230801914750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dluzen DE, Liu B. Gender differences in methamphetamine use and responses: A review. Gender Medicine. 2008;5(1):24–35. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(08)80005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haley N, Roy E, Leclerc P, Boudreau JF, Boivin JF. HIV risk profile of male street youth involved in survival sex. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:526–530. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.010728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuyper LM, Lampinen TM, Li K, Spittal PM, Hogg RS, Schechter MT, Wood E. Factors associated with sex trade involvement among male participants in a prospective study of injection drug users. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:531–535. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerr T, Marshall BDL, Miller C, Shannon K, Zhang R, Montaner JSG, Wood E. Injection drug use among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cusick L. Widening the harm reduction agenda: From drug use to sex work. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(1):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashley OS, Marsden ME, Brady TM. Effectiveness of substance abuse treatment programming for women: A review. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29(1):19–53. doi: 10.1081/ada-120018838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Des Jarlais DC, Marmor M, Paone D, Titus S, Shi Q, Perlis T, Jose B, Friedman SR. HIV incidence among injection drug users in New York City syringe-exchange programmes. Lancet. 1996;348(9033):987–91. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]