Abstract

The requirement for TLR signaling in the initiation of an Ag-specific Ab response is controversial. In this report we show that a novel OVA-expressing recombinant Salmonella vaccine (Salmonella-OVA) elicits a Th1-biased cell-mediated and serum Ab response upon oral or i.p. immunization of C57BL/6 mice. In MyD88−/−mice, Th1-dependent Ab responses are greatly reduced while Th2-dependent Ab isotypes are elevated in response to oral and i.p., but not s.c. footpad, immunization. When the T effector response to oral vaccination is examined we find that activated, adoptively transferred Ag-specific CD4+ T cells accumulate in the draining lymph nodes, but fail to produce IFN-γ, in MyD88−/− mice. Moreover, CD1d tetramer staining shows that invariant NKT cells are activated in response to oral Salmonella-OVA vaccination in wild-type, but not MyD88−/−, mice. Treatment with neutralizing Ab to CD1d reduces the OVA-specific Ab response only in MyD88-sufficient wild-type mice, suggesting that both Ag-specific CD4 T cell and invariant NKT cell effector responses to Salmonella-OVA vaccination are MyD88 dependent. Taken together, our data indicate that the type of adaptive immune response generated to this live attenuated vaccine is regulated by both the presence of MyD88-mediated signals and vaccination route, which may have important implications for future vaccine design.

Activation of the innate immune system through pattern recognition receptors is required for the induction of adaptive Ag-specific immunity. The best characterized pattern recognition receptors, the TLRs, recognize microbes and microbial products on the cell surface or within endosomes and are often considered primary sensors of innate immunity (1). Whether TLR-mediated signals are required for the production of an Ag-specific Ab response has been quite controversial (2–5). While some authors have reported impaired Ag-specific Ab responses in the setting of MyD88 deficiency (6), others have found robust Ag-specific Ab responses in mice with global deficiencies in both MyD88 and TRIF or reconstituted with MyD88-deficient B cells (7–9). Beyond its fundamental importance for our understanding of the requirement for TLR-mediated signals in the generation of Ab responses, reconciling these disparate findings is of practical significance for vaccine design, specifically, optimizing vaccine formulations and administration routes (10).

It is well established that cytokines produced by CD4+ T cells regulate and support B cell class switching and differentiation to Ab-producing cells of various Ig isotypes. Recent work has shown that cytokine secretion by innate immune effector populations, particularly invariant NKT (iNKT)4 cells, also plays a role in B cell differentiation (11, 12). As unique cells that recognize glycolipid Ag complexed to the MHC class I-like molecule CD1d, iNKT cells are characterized by their rapid production of large amounts of both Th1-associated and Th2-associated effector cytokines following TCR engagement (13). In recent reports iNKT cells have been shown to enhance vaccine Ag-specific Ab responses and promote B cell memory (12, 14).

Oral vaccines provide a safe, effective, and relatively inexpensive way to induce protection against infectious diseases. Unlike parenteral vaccines, which generally elicit robust serum Ab responses but weak cellular and mucosal responses, oral vaccines elicit strong local cellular and mucosal IgA responses in addition to protective serum Ab (15). Since most pathogens enter the body at the mucosal barriers of the gut and airways, these local immune responses are important in deterring the invasion of microorganisms and decreasing their transmission from one host to another (16). Currently, however, most licensed human vaccines are administered by parenteral injection, typically as protein subunits adsorbed to the nonmicrobial adjuvant alum (17). The generation of an Ab response following vaccination is a correlate to protective immunity and the “gold standard” for vaccine efficacy (18, 19).

We have created a novel, clinically relevant, OVA-expressing live attenuated Salmonella typhimurium vaccine (Salmonella-OVA) to examine the role of MyD88 signaling in the generation of vaccine-induced serum Ab responses. We found that the MyD88 dependence of the serum Ab response varies with the route of immunization. Oral or i.p. immunization of C57BL/6 mice with our Salmonella-OVA vaccine elicited a Th1-biased cell-mediated and serum Ab response. In the absence of MyD88 signaling, vaccination with Salmonella-OVA also induced robust serum Ab responses, but these were predominantly comprised of the Th2- and TGF-β-dependent serum Ab isotypes IgG1, IgG2b, and IgA. The absence of MyD88 signaling in host cells resulted in impaired IFN-γ production by adoptively transferred, Ag-specific T cells. MyD88-mediated signals were also required for CD1d-restricted iNKT cell activation following oral vaccination with Salmonella-OVA, indicating that both the Ag-specific T cell and the iNKT cell effector response to this vaccine is MyD88 dependent. Our data suggest that in the absence of MyD88, the route of immunization governs the type of Ab response elicited.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Male and female C57BL/6 J mice (6 –10 wk of age) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. OT2 (Thy1.1) mice on the C57BL/6 background, transgenic for the TCR recognizing OVA peptide 323–339, were provided by A. Luster (Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA). MyD88−/− mice on the C57BL/6 background, originally generated by Akira and colleagues (20), were provided by M. Freeman (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA) (21) and maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility at Massachusetts General Hospital. Age- and sex-matched wild-type (WT) and heterozygous littermates or C57BL/6 J mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory served as controls. All experiments were conducted after approval and according to regulations of the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Preparation and characterization of a Salmonella OVA vaccine

The attenuated aroA S. typhimurium vaccine strain SL3261 (22) was provided by M. N. Starnbach (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). The plasmid pTETnir15, which expresses tetanus toxoid fragment C under the control of the anaerobically inducible nirB promoter (23), was obtained from Peptide Therapeutics by material transfer agreement. The plasmid pCB7OVA contains the entire coding region of OVA and was derived from the E.G7-OVA cell line (24). To construct pnirOVA, the OVA gene was PCR amplified from pCB7OVA using Platinum PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen) containing 2.65 mM MgCl2. The 5′ primer, GCTCTAGAAGATCTTATTATG AAAAACA TCGGCGCAGCAAGCATGGAATT, contains an AT-rich region (italics) before the start codon (bold) that optimizes the expression of OVA protein. The 3′ primer was CGGAATTCGGATCCT TAAGGGGAAACACATCTGCC. The ~1200-bp OVA PCR product was digested with EcoRI and XbaI and ligated into pUC19 to make pUCFLO (not shown). pUCFLO was then digested with BglII and BamHI, and the OVA insert (~1200 bp) was ligated into pTETnir15 to create pnirOVA. To generate pnirBEM (EMpty), pTETnir15 was digested with BglII and BamHI, and the large fragment containing the Ap-resistance gene was self-ligated. Transformant colonies carrying PCR inserts were identified by restriction analysis using the appropriate enzymes. Plasmid constructs containing the correct PCR inserts were transferred into S. typhimurium SL3261 by electroporation using a BTX ECM 600 electroporator. Before vaccination, S. typhimurium was plated from frozen stocks on Luria-Bertani plates containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and incubated overnight at 37°C. Resulting colonies were used to inoculate Luria-Bertani broth containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and grown shaking at 37°C. Culture density was estimated using the following conversion factor: OD600 of 0.5 = 2 × 108 bacteria/ml, and the number of inoculated bacteria was confirmed by plating.

Western blot analysis and quantitation

Protein was extracted from 2 to 3 × 1010 Salmonella-OVA or Salmonella-BEM using bacterial protein extraction reagent (Pierce). An estimated 25 μg of total bacterial protein or 25 μg of OVA protein (OVA, grade V; Sigma-Aldrich) was resolved on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Western blots were then performed using rabbit anti-OVA serum (Rockland) according to the protocol for the Advanced One-Step Western kit (GenScript). Blots were developed using the Lumi-Sensor Plus reagent (GenScript) and CL-XPosure film (Pierce). The amount of OVA protein in one oral dose of Salmonella-OVA was estimated by comparison to graded dilutions of OVA (50 – 200 ng) using densitometric analysis with National Institutes of Health ImageJ software.

Vaccination with an attenuated Salmonella-OVA vaccine

Mice had free access to food and water and were inoculated gastrically with 2 to 6 × 1010 Salmonella in 250 – 300 μl of PBS using a 20-gauge ball-tipped feeding needle. In some experiments, 1 day before oral immunization, and every 2 days afterward throughout the duration of the experiment, mice were injected i.p. with 500 μg per mouse of neutralizing rat anti-mouse CD1.1 mAb (hybridoma HB323; American Type Culture Collection) purified by protein G chromatography (INVO Bioscience) or with purified rat IgG (Antibodies Incorporated). For one series of experiments mice were immunized i.p. with 2 to 4 × 105 Salmonella in 250 μl of PBS. To determine CFU Salmonella per gram of tissue, spleens and livers were weighed, homogenized in PBS, and plated on Luria-Bertani or MacConkey plates containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. In separate experiments mice were immunized s.c. in each hind footpad with either 1 × 109 heat-killed Salmonella in PBS (25) or 150 μg of OVA protein emulsified in CFA (Difco Laboratories).

Measurement of Ab responses

OVA-specific serum IgG1, IgG2b, IgG2c, and IgG3 levels were determined by ELISA as previously described (26), using HRP-conjugated Abs specific for each isotype and the substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Pierce). OVA-specific serum IgA responses were detected with avidin phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgA (SouthernBiotech) and developed with p-nitrophenylphosphate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). To measure fecal OVA-specific IgA, fecal extracts were prepared and assayed as described by Duverger et al. (27).

OVA-TCR transgenic CD4+ T cell enrichment and adoptive transfer

Spleens and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) were harvested from OT2 (Thy1.1) mice and T lymphocytes were enriched using nylon wool fiber columns (Polysciences) before positive selection with CD4 (L3T4) magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). T cell purity was >95%. Cells (4 to 9 × 106) suspended in PBS were injected i.v. into C57BL/6 and MyD88−/− mice.

Cell surface staining, tetramer staining, and flow cytometry

Thy1.1-FITC (clone OX-7), CD69-PE (clone H1.2F3), CD3ε-PerCP (clone 145-2c11), and CD4-PerCP (clone RM4-5) Abs and their control isotypes were all purchased from BD Biosciences. Unloaded CD1d tetramers and CD1d tetramers loaded with the α-galactosylceramide analog PBS57 (28) and complexed with PE-conjugated streptavidin were provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases tetramer facility (Emory University Vaccine Center, Atlanta, GA). Splenocytes, MLN cells, or hepatic mononuclear cells were blocked with Abs against CD16/CD32 (BD Biosciences) and stained with mAbs for 20 min at 4°C in PBS containing 2% FCS and 0.09% NaN3, washed, and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. In some experiments, before fixation and after mAb staining, cells were stained with tetramer for 30 min at 4°C as described by Kamath et al. (29). Cells were acquired using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and data analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Intracellular cytokine staining

Splenocytes or MLN cells were stimulated as previously described (30, 31) with some modifications. Cells were seeded at 2 × 106 cells/ml in 24-well plates in complete DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 2 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 55 μM 2-ME, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate and incubated for 24 h with 200 μg/ml OVA (grade V; Sigma-Aldrich). Before being added to cultures, contaminating LPS was removed from the OVA preparation using a Detoxi-Gel endotoxin removal column (Pierce). During the final 4 h of culture, cells were pulsed with 12.5 ng/ml PMA (Sigma-Aldrich), 500 ng/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 μg/ml GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Liver mononuclear cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/ml in 48-well plates in complete DMEM and were cultured for 4 h with PMA, ionomycin, and GolgiPlug as described above. Cells were harvested and surface stained as described above and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD Biosciences), washed with Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences), and stained with anti-IFN-γ-allophycocyanin (clone XMG1.2) and anti-IL-17-PE (clone TC11-18H10) or anti-IL-4-PE (clone 11B11; all from BD Biosciences) or anti-IL-4 FITC (clone BVD6-24G2; eBioscience). Flow cytometry and analysis was performed as described above.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM and were compared using the unpaired Student’s t test. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characterization of a novel OVA-expressing oral Salmonella vaccine

Attenuated bacterial pathogens can function as potent oral vaccines to elicit systemic immunity to heterologously expressed protein Ags (32). We used an attenuated Salmonella vaccine strain to create an OVA-expressing oral vaccine. OVA was expressed under the control of the anaerobically inducible promoter nirB (23) (Fig. 1A; see Materials and Methods for description of the construction of pnirOVA). The negative control plasmid pnirBEM does not encode any proteins. Western blot analysis showed that anti-OVA antiserum detects an OVA band of ~40 kDa in bacteria carrying the pnirOVA (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 5) but not the pnirBEM (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 4) constructs. Densitometric analysis estimated that 1010 bacteria contained 0.6 μg of OVA or ~2– 4 μg of OVA for each oral dose of Salmonella-OVA (data not shown). Although previous reports have described OVA-expressing Salmonella strains that induce OVA-specific T cell responses in vitro and in vivo (33, 34), none of these studies has demonstrated induction of OVA-specific serum Ab responses after gastric administration. We vaccinated groups of WT C57BL/6 mice with two doses of either Salmonella-BEM or Salmonella-OVA to examine whether Salmonella-OVA elicited a serum Ab response. Only mice vaccinated with Salmonella-OVA produced a Th1-dependent OVA-specific serum IgG2c Ab response (Fig. 1C) as well as OVA-specific serum (Fig. 1D) and mucosal (Fig. 1E) IgA responses.

FIGURE 1.

A novel Salmonella-OVA vaccine elicits an OVA-specific Ab response in serum and external secretions. A, Parent plasmid pTETnir15 (23) and daughter plasmids pnirOVA and pnirBEM contain an ampicillin (Ap) resistance gene and encode tetanus toxoid fragment C, chicken egg OVA, or no heterologous protein, respectively, under the control of the anaerobically inducible nirB promoter. B, Western blot analysis of bacterial strains carrying indicated plasmid constructs demonstrates that Salmonella carrying pnirOVA (Salmonella-OVA, lanes 3 and 5), but not pnirBEM (Salmonella-BEM, lanes 2 and 4), express OVA protein. Lane 1 contains 25 μg of OVA protein. OVA-specific serum IgG2c (C) and IgA (D) in WT C57BL/6 mice 14 and 28 days after two gastric doses of 2 × 1010 Salmonella-OVA or Salmonella-BEM measured by ELISA. Twenty-eight days after the second dose, OVA-specific IgA in fecal extracts (E) was measured by ELISA. Data represent three independent experiments (n = 6 mice/ group). Means ± SEM are shown.

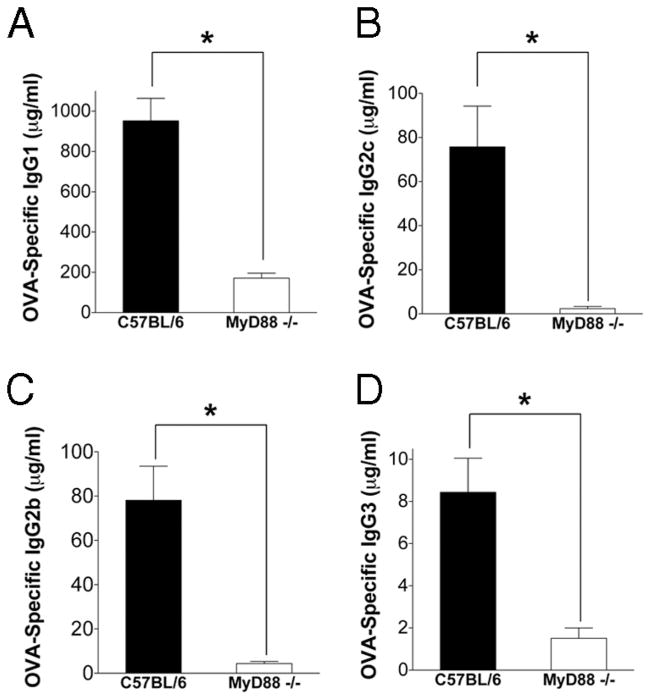

Ag-specific serum IgG responses are reduced in MyD88−/− mice following peripheral footpad immunization

It has been reported that Ag-specific Ab responses following immunization with Ag and adjuvant via the s.c. route are impaired in the absence of MyD88 signaling (6). In agreement with previous reports (6, 35), we found that OVA-specific serum IgG1, IgG2c, IgG2b, and IgG3 responses to s.c. injection of Ag and adjuvant in the footpad were reduced in MyD88−/− mice as compared with WT mice (Fig. 2). To determine whether TLR signaling through MyD88 was also necessary for the generation of OVA-specific Ab responses to the Salmonella-OVA vaccine following s.c. immunization in the footpad, we vaccinated groups of WT and MyD88−/− mice with 109 CFU equivalents of heat-killed Salmonella-OVA. The magnitude of the OVA-specific IgG response to footpad injection of heat-killed Salmonella-OVA was 100- to 10,000-fold lower than the OVA-specific IgG response to OVA/CFA and was further reduced in MyD88−/− mice compared with WT mice (data not shown). Collectively, these data support and extend previous observations that the generation of Ag-specific IgG responses to peripheral footpad immunization is impaired in the absence of MyD88 signaling (6).

FIGURE 2.

The absence of MyD88 signaling reduces OVA-specific serum IgG responses to s.c. immunization in the footpad. WT C57BL/6 or MyD88−/− mice were bled 2 wk after immunization with 150 μg OVA emulsified in CFA and OVA-specific serum IgG1 (A), IgG2c (B), IgG2b (C), and IgG3 (D) measured by ELISA. Pooled data from three independent experiments are shown (n = 10 –11 mice/group). *, p < 0.05. Error bars represent SEM.

Oral and i.p. vaccination induces Th2- and TGF-β-dependent serum Ab isotypes in the absence of MyD88 signaling

To determine whether the generation of an Ab response following oral vaccination depended on MyD88 signaling, we orally vaccinated groups of MyD88−/− and WT mice with Salmonella-OVA or Salmonella-BEM. As had been reported for peripheral footpad immunization with OVA in adjuvant (Ref. 6 and Fig. 2), we found that MyD88−/− mice produced significantly less serum IgG2c than did WT mice in response to oral vaccination with Salmonella-OVA (Fig. 3A). However, in marked contrast to footpad immunization, oral vaccination elicited serum OVA-specific IgG1 responses in MyD88−/− mice that were undetectable in WT mice (Fig. 3B). Orally administered Salmonella-OVA elicited comparable TGF-β-dependent OVA-specific serum IgG2b and IgA responses in both MyD88−/− and WT mice (Fig. 3, C and D). OVA-specific serum IgG3 responses were not detectable above background (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

In the absence of MyD88 signaling, oral vaccination induces serum IgG1 and IgA. C57BL/6 (filled bars) or MyD88−/− (open bars) mice were given one gastric dose of 3 to 6 × 1010 Salmonella carrying pnirBEM (Salm-BEM) or pnirOVA (Salm-OVA), and OVA-specific serum IgG2c (A), IgG1 (B), IgG2b (C), and IgA (D) were measured 14, 21, and 28 days postvaccination by ELISA. Pooled data from three independent experiments are shown (n = 9 –13 mice/group). *, p < 0.05. Error bars represent SEM.

Because recent work has demonstrated that i.p. immunization of mice with global deficiencies in both MyD88 and TRIF (7) or reconstituted with B cells deficient in MyD88 (8) results in robust Ag-specific Ab responses in these animals, we also examined the Ig response to our vaccine when administered via the i.p. route. In agreement with these previous reports, we found that MyD88−/− mice produced OVA-specific serum IgG following i.p. vaccination with Salmonella-OVA (Fig. 4). Similar to the Ig profile following oral vaccination, i.p. vaccination of MyD88−/− mice with Salmonella-OVA induced significantly less serum IgG2c and elevated OVA-specific IgG1 responses that were not detected in WT mice (Fig. 4, A and B). The magnitude of the OVA-specific serum IgG2b and IgG3 responses generated by MyD88−/− mice were not significantly different from those generated by WT mice, although the kinetics of the responses differed. In WT mice, OVA-specific IgG2b responses increased and IgG3 responses decreased and then plateaued over time, while in MyD88−/− mice, OVA-specific IgG2b and IgG3 levels remained constant over the course of the experiment (Fig. 4, C and D). Since i.p. immunization does not introduce Ag directly to a mucosal surface, as expected, no OVA-specific serum IgA was detected following i.p. immunization with Salmonella-OVA (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Intraperitoneal vaccination also induces serum IgG1 in the absence of MyD88 signaling. C57BL/6 (filled bars) or MyD88−/− (open bars) mice were given one i.p. dose of 2 × 105 Salmonella carrying pnir-BEM (Salm-BEM) or pnirOVA (Salm-OVA), and OVA-specific serum IgG2c (A), IgG1 (B), IgG2b (C), and IgG3 (D) were measured 21, 28, and 35 days postvaccination by ELISA. Pooled data from two independent experiments are shown (n = 3–11 mice/group). *, p < 0.05. Error bars represent SEM. In B, most mice (whether C57BL/6 or MyD88−/−) did not make an OVA-specific IgG1 response; the few that did were MyD88−/− mice. Because of this partial response to the vaccine in MyD88−/− mice, the OVA-specific serum IgG1 responses of MyD88−/− and C57BL/6 mice vaccinated i.p. with Salmonella-OVA are not statistically significantly different using the unpaired Student t test with unequal variances.

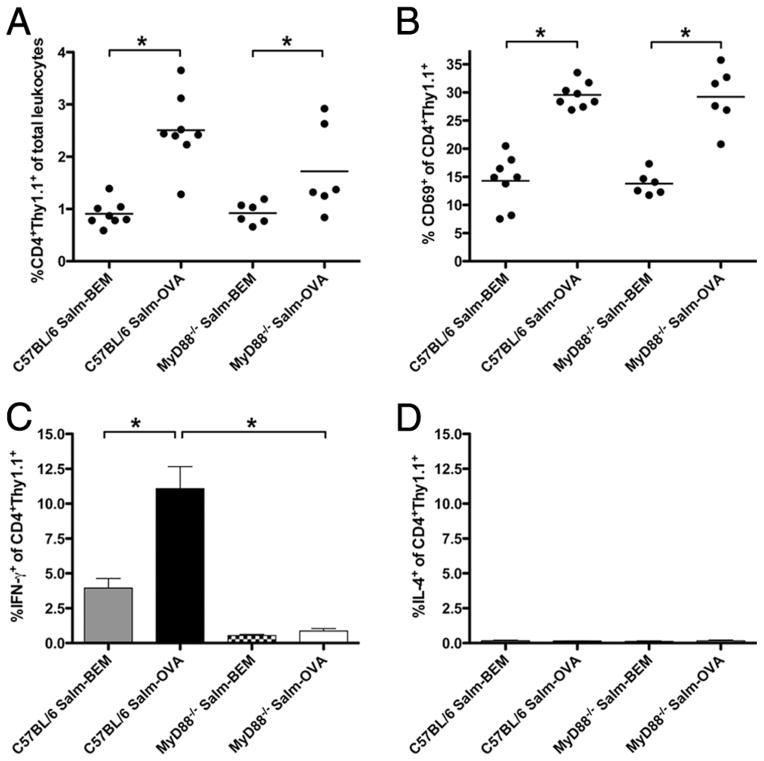

CD4+ T cells accumulate in the MLN of MyD88−/− mice following oral vaccination with Salmonella-OVA but fail to make IFN-γ

We hypothesized that the reduced OVA-specific serum IgG2c response and the elevated serum IgG1 response in MyD88−/− mice following oral vaccination with Salmonella-OVA was due to decreased production of IFN-γ (the switch factor for IgG2c) (36) and increased production of IL-4 (the switch factor for IgG1) (36) by Ag-specific CD4+ T cells. To examine this hypothesis, WT and MyD88−/− mice (whose T cells express the surface marker Thy1.2) were adoptively transferred with CD4+Thy1.1+ OVA-specific TCR transgenic OT2 cells and orally vaccinated with either Salmonella-OVA or the control vaccine, Salmonella-BEM, 1 day after transfer. Up-regulation of cell surface expression of CD69 is a standard marker of early lymphocyte activation and has been linked with retention of activated T cells in lymph nodes to allow for the development of effector T cell function (37–39). Three days after oral vaccination, the frequency of CD4+Thy1.1+ OT2 cells, and the proportion of these cells that expressed CD69, was higher in the MLN of both WT and MyD88−/− mice vaccinated with Salmonella-OVA as compared with those vaccinated with Salmonella-BEM (Fig. 5, A and B). This suggested Ag-driven T cell activation in both WT and MyD88−/− mice orally vaccinated with Salmonella-OVA. However, the proportion of CD4+ Thy1.1+ OVA-specific cells producing IFN-γ was markedly (12-fold) higher in WT mice orally vaccinated with Salmonella-OVA than in their MyD88−/− counterparts (Fig. 5C), consistent with the reduced OVA-specific IFN-γ-dependent IgG2c response. These data suggest that while Ag-specific stimulation via the TCR results in early T cell activation and temporary retention of adoptively transferred OVA-specific transgenic T cells in the draining lymph node, intact MyD88 signaling is required for the generation of IFN-γ-producing T effector cells following oral vaccination with Salmonella-OVA. We detected very low frequencies (<0.2%) of IL-4-producing cells within the transferred CD4+Thy1.1+ OT2 subset in the MLN and no differences in frequency of IL-4-producing CD4+Thy1.1+ OVA-specific cells between orally vaccinated MyD88−/− and WT mice (Fig. 5D). IL-17+ cells were not detectable in the transferred CD4+Thy1.1+ OT2 subset in the MLN (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Activated Ag-specific CD4+ T cells that fail to make IFN-γ accumulate in the draining MLN of MyD88−/− mice orally vaccinated with Salmonella-OVA. A, Proportion of adoptively transferred CD4+Thy1.1+ OVA-TCR transgenic OT2 cells in MLN. B, Percentge CD69+ among CD4+Thy1.1+ OT2 cells in MLN. Dots represent individual mice. Lines represent mean percentages for each treatment group. C, Percentage IFN-γ+ among CD4+Thy1.1+ OT2 MLN cells is shown. D, Percentage IL-4+ among CD4+Thy1.1+ OT2 MLN cells is shown. In C and D, 3 days after one gastric dose of ~6 ×1010 Salmonella, MLN cells were cultured overnight with OVA, pulsed for 4 h with PMA, ionomycin, and GolgiPlug, surface labeled with mAbs against CD4 and Thy1.1, fixed, permeabilized, and intracellularly stained with Abs to IFN-γ or IL-4. Means ± SEM are shown. Salm-BEM indicates fed Salmonella-BEM; Salm-OVA, fed Salmonella-OVA. Pooled data from three independent vaccinations are shown. C57BL/6 Salm-BEM (n = 8), C57BL/6 Salm-OVA (n = 8), MyD88−/− Salm-BEM (n = 6), MyD88−/− Salm-OVA (n = 6). *, p < 0.05.

When we examined the proportion of nontransgenic host CD4+IFN-γ+Thy1.1− T cells (or Thy1.1− non-T cells) that accumulated in the MLN of mice orally immunized with Salmonella, we found that they were also reduced 3- to 5-fold in MyD88−/− as compared with WT mice (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, the proportion of nontransgenic host CD4+Thy1.1− (or Thy1.1−) IL-4+ and IL-17+ cells was increased in the MLN of orally immunized MyD88−/− mice (Fig. 6C–F), supporting the contention that cytokine T effector profiles are altered in the absence of MyD88 signaling.

FIGURE 6.

IFN-γ production is impaired and IL-4 and IL-17 production enhanced in CD4+ and CD4− Thy1.1− cells from the draining MLN of MyD88−/− mice orally vaccinated with Salmonella-OVA. A, Percentage IFN-γ+ among CD4+Thy1.1− T cells is shown. B, Percentage IFN-γ+ among all host Thy1.1− cells is shown. C, Percentage IL-4+ among CD4+Thy1.1− T cells is shown. D, Percentage IL-4+ among all host Thy1.1− cells is shown. E, Percentage IL-17+ among CD4+Thy1.1− T cells is shown. F, Percentage IL-17+ among all host Thy1.1− cells is shown. In all panels, 3 days after one gastric dose of ~6 × 1010 Salmonella, MLN cells were cultured overnight with OVA, pulsed for 4 h with PMA, ionomycin, and GolgiPlug, surface labeled with mAbs against CD4 and Thy1.1, fixed, permeabilized, and intracellularly stained with Abs to IFN-γ, IL-4, or IL-17. Means ± SEM are shown (n = 3– 8 mice/group). *, p < 0.05.

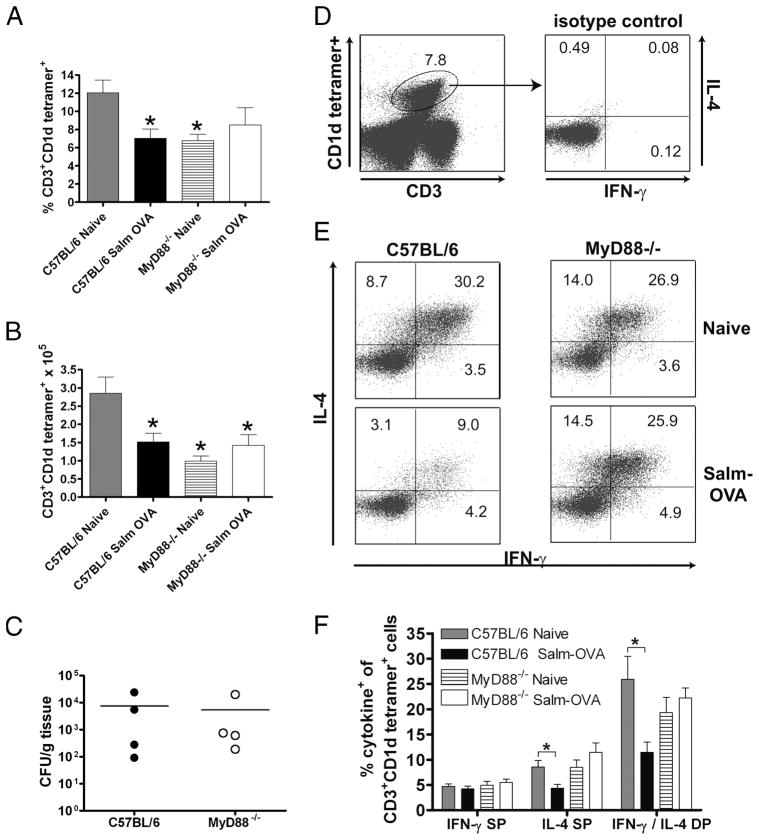

CD1d-restricted iNKT cell activation and cytokine production in response to Salmonella-OVA is also MyD88 dependent

As mentioned in the Introduction, iNKT cells are also an important source of Ag-independent innate immune effector cytokines. These unconventional T cells express an invariant Vα14Jα18 TCR α-chain, typically in conjunction with Vβ8.2, Vβ2, or Vβ7 in mice (13), and recognize self, pathogen-derived, or other exogenous glycolipid Ags, such as the synthetic lipid α-galactosylceramide presented in the context of the MHC class-I like protein CD1d (40, 41). iNKT cells have been reported to produce cytokines after oral or i.p. infection with a virulent, pathogenic Salmonella strain (42, 43). We detected very low frequencies (<0.2%) of CD3+CD1d tetramer+ iNKT cells in the MLN of both WT and MyD88−/− mice, with or without oral vaccination. However, others have shown that iNKT cells are detectable in the intestinal lamina propria (44).

Although immunological cross-talk between the gut and liver is not well studied, the liver is also part of the enteric immune system (45) and is exposed to orally administered Ags and bacterial products through the portal venous circulation (46). As an early target organ of Salmonella infection (47), the liver contains lymphocytes throughout its parenchyma and portal tracts (45), and in mice, up to 30% of liver lymphocytes are iNKT cells (40). Indeed, the mean frequencies of iNKT cells in the livers of both WT and MyD88−/− mice, whether orally vaccinated with Salmonella-OVA or not, were 35- to 70-fold greater than their frequencies in the MLN, ranging from 6% to 12% (Fig. 7A), as has been reported elsewhere (40, 48). We found both lower frequencies and lower total numbers of hepatic CD1d-restricted T cells in MyD88−/− mice compared with WT mice. Additionally, both the frequency and total number of CD1d-restricted T cells were strikingly decreased in the livers of orally vaccinated WT mice (Fig. 7, A and B). Activated iNKT cells down-regulate their TCR in response to α-galactosylceramide stimulation or ongoing infection, rendering the cells largely undetectable by CD1d tetramer staining (49 –51). Experimental infection with virulent Salmonella has previously been reported to result in iNKT cell activation in the liver and a concomitant decline in the frequency of CD1d tetramer-positive cells (42, 48). In contrast to the WT mice, the numbers and frequency of liver iNKT cells remained unchanged after vaccination of MyD88−/− mice with the attenuated Salmonella vaccine (Fig. 7, A and B), although the vaccine was recoverable from the livers of both WT and MyD88−/− mice at the time of sacrifice (Fig. 7C). We next examined whether iNKT cells in MyD88−/− mice produced IFN-γ and/or IL-4 following oral vaccination with Salmonella-OVA. Intracellular cytokine staining showed that the proportion of hepatic iNKT cells secreting both IFN-γ and IL-4 in response to stimulation with PMA and ionomycin was similar in naive WT and MyD88−/− mice (Fig. 7E). There was a significant reduction in the frequency of CD1d tetramer-positive IFN-γ+IL-4+ and IFN-γ−IL-4+ cells among liver mononuclear cells from WT mice vaccinated with Salmonella-OVA (Fig. 7, E and F). In contrast, there were no alterations in the frequencies of IFN-γ+IL-4+ or IFN-γ−IL-4+ cells among hepatic CD1d tetramer-positive populations from vaccinated and unvaccinated MyD88−/− mice (Fig. 7, E and F). Our data suggest that, in WT mice, iNKT cells are activated and rapidly secrete cytokines in response to Salmonella-OVA vaccination. Upon activation they become undetectable by CD1d tetramer staining due to either TCR down-regulation or apoptosis/deletion. In contrast, we found no detectable evidence of iNKT cell activation in response to oral Salmonella-OVA vaccination in MyD88−/− mice.

FIGURE 7.

CD1d-restricted iNKT cell activation in response to oral immunization with Salmonella-OVA is MyD88 dependent. A, Percentage CD3+ CD1d tetramer+ among liver lymphocytes. B, Absolute number of CD3+ CD1d tetramer+ cells. In A and B, *, p < 0.05 compared with C57BL/6 naive. C, Bacterial titers in livers of C57BL/6 (●) and MyD88−/− mice (○) 3 days after one gastric dose of ~6 × 1010 Salmonella-OVA. Pooled data from two independent vaccinations; dots represent individual mice; lines indicate mean CFU/g tissue. D, Left panel, iNKT cell gate on CD3 intermediate, CD1d tetramer+ events in liver. Right panel, Intracellular staining of iNKT cells with rat IgG1 isotype control. E, Representative flow cytometry data showing percentage IL-4+ and IFN-γ+ among liver iNKT cells from naive and Salmonella-OVA-fed C57BL/6 or MyD88−/− mice. Numbers in each quadrant represent percentage of liver iNKT cells that are IFN-γ single positive (SP), IL-4 SP, and IFN-γ/IL-4 double positive (DP) 3 days after gastric administration of ~6 × 1010 Salmonella-OVA and after 4 h of culture with PMA, ionomycin, and GolgiPlug. F, Graphical representation of data in E. Pooled data from four independent vaccinations. Means ± SEM are shown. Naive indicates no treatment; Salm-OVA, fed Salmonella-OVA. C57BL/6 naive (n = 8), C57BL/6 Salm-OVA (n = 10), MyD88−/− naive (n = 7), MyD88−/− Salm-OVA (n = 8). *, p < 0.05.

Treatment with neutralizing Ab to CD1d significantly reduces Ag-specific IgG2c responses to oral vaccination in WT mice

To determine whether CD1d-dependent cytokine secretion by iNKT cells following oral vaccination with Salmonella-OVA was necessary for the generation of the OVA-specific Th1- and Th2-dependent serum IgG responses in these mice, we treated both WT and MyD88−/− mice with a blocking mAb against CD1d (52) or polyclonal rat IgG as a control 1 day before and every 2 days following vaccination (Fig. 8). As expected, 21 days after vaccination, mean OVA-specific IgG2c responses were reduced in sham-treated MyD88−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 8A), while mean OVA-specific IgG1 responses to Salmonella-OVA were significantly greater in sham-treated MyD88−/− mice than in sham-treated WT mice (Fig. 8B). There was a significant reduction in the OVA-specific IgG2c response in anti-CD1d-treated WT mice, suggesting that the activation of CD1d-restricted T cells was critical for optimal Ag-specific IgG2c responses to oral Salmonella-OVA. However, no significant alterations in either the OVA-specific IgG2c or IgG1 response were detectable in anti-CD1d-treated MyD88−/− mice, consistent with the absence of activated CD1d-restricted iNKT cells in these mice after oral Salmonella-OVA vaccination (see Fig. 7, E and F). Additionally, we found no statistically significant differences in the OVA-specific serum IgA or IgG2b levels between sham-treated and anti-CD1d-treated, orally vaccinated WT or MyD88−/− mice (Fig. 8, C and D), suggesting that activation of CD1d-restricted iNKT cells is not required for Ab class switching to IgA or IgG2b in WT or MyD88−/− mice. Taken together, these results suggest that effector cytokines that support the OVA-specific IgG2c response to vaccination with Salmonella-OVA are produced by both Ag-specific T cells and CD1d-restricted iNKT cells. Importantly, effector cytokine production in both cell populations depends on MyD88-mediated signals.

FIGURE 8.

Treatment with a neutralizing Ab to CD1d significantly reduces Ag-specific IgG2c responses to oral vaccination in WT mice. C57BL/6 or MyD88−/− mice were treated or not with 500 μg of CD1.1 blocking Ab i.p. every 2 days starting 1 day before receiving one gastric dose of 4 × 1010 Salmonella-OVA. OVA-specific serum IgG2c (A), IgG1 (B), IgG2b (C), and IgA (D) were measured 21 days postvaccination by ELISA. Pooled data from two independent experiments are shown (n = 4 –12 mice/group). *, p < 0.05. Error bars represent SEM.

Discussion

It is widely accepted that TLR ligands can augment Ab responses, but the requirement for MyD88-mediated TLR signaling for the generation of Ag-specific serum Ab responses to immunization with Ag and adjuvant is still a matter of debate (2– 8, 10). We have examined the response to a clinically relevant, live attenuated Salmonella vaccine expressing the model Ag OVA after delivery via oral, i.p., and s.c. routes. Initial work suggested that TLR signaling through the MyD88 adaptor protein on both B cells and dendritic cells (DCs) is essential for the generation of a serum Ab response to peripheral footpad immunization with Ag in adjuvant (6). More recent work has demonstrated that, in contrast to s.c. immunization in the footpad, robust Ag-specific Ab responses can be induced in mice with global deficiencies in both MyD88 and TRIF (7, 9). Transfer of MyD88−/− or WT B cells into B cell-deficient mice before i.p. immunization with haptenated protein in alum elicited equivalent Ab responses in both groups of mice, suggesting that B cell-intrinsic TLR signals are not required (8). We found that, in the absence of MyD88 signaling, immunization via the oral and i.p., but not s.c., routes induced robust serum Ab responses comprised of the Th2- and TGF-β-dependent serum Ab isotypes IgG1, IgG2b, and IgA. Of note, in contrast to our findings and other reports (8, 10), Pasare and Medzhitov observed impaired Ag-specific total Ig, IgM, IgG1, and IgG3 responses in MyD88−/− mice following i.p. immunization with HSA/LPS/alum or flagellin/alum (6). This may reflect differential requirements for MyD88 signaling in generating Ab responses to i.p. immunization with protein subunits or TLR ligands adsorbed to alum as opposed to haptens (8, 10) or live attenuated bacteria (our study). Indeed, Hou and colleagues have recently observed that the physical form of the TLR9 ligand and vaccine adjuvant CpG modulates humoral responses to coadministered T-dependent Ag introduced via the i.p. route in the absence of MyD88 signaling in DCs (53).

Moreover, we suggest that the reported discrepancies in the MyD88 dependence of the induction of a serum Ab response might be reconciled by considering the influence of the different routes of Ag administration employed in each study, that is, s.c. injection in the footpad (6) and i.p. injection (7, 8), and, as a result, the distinct local cytokine microenvironments that Ag and adjuvants initially encounter. Our data show that when MyD88 signaling is intact, immunization with Ag in adjuvant containing TLR ligands, whether OVA/CFA or the OVA-expressing Salmonella vaccine, promotes productive Ag-specific Th1-dependent cytokine responses (Fig. 5) and serum IgG2c responses (Figs. 2– 4) irrespective of the route of immunization (s.c., oral, or i.p.). This is likely due to the production of proinflammatory cytokines like IL-12 following TLR signaling through MyD88, critical for promoting protective CD4+ Th1 effector responses (53) during a variety of microbial infections, including experimental salmonellosis (30, 43, 54). Our data suggest that, in MyD88-deficient mice, the route of immunization comes to the forefront in determining the quality, magnitude, and longevity of serum Ab responses to primary immunization. When Ag and adjuvant are introduced s.c. in the footpad, where they drain to the microenvironment of the popliteal node (55), the absence of MyD88-mediated TLR signals in DCs may block full DC maturation and Th cell activation, preventing T cell help to B cells. This, coupled with impaired TLR signaling in B cells themselves, may then result in suboptimal IgG Ab responses to T-dependent Ag (Fig. 2 and Ref. 6). In contrast, immunization via the oral and i.p. routes introduces Ag to mucosal-associated lymphoid structures: the MLN and Peyer’s patches in the case of oral immunization (16, 56), and the mediastinal nodes (which also drain the lungs and airways) in the case of i.p. immunization (57). Previous work from our laboratory (58) and a recent report from Kool and colleagues (57) have shown that i.p. immunization also drains, at least in part, to the gut associated lymphoid tissue, activating effector populations in the MLN. The cytokine microenvironment of mucosal surfaces is geared toward the large-scale production of sIgA, which bathes and safeguards the integrity of the epithelial barrier (16). Class switching to IgA (as well as IgG2b) requires TGF-β (59). The Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 also contribute to switching to IgA and the maturation of Ab-secreting cells (60). These cytokines are all abundantly produced at mucosal surfaces, particularly by the phenotypically and functionally unique subpopulations of DCs that take up Ag administered to these sites (61). The production of mucosal TGF-β is apparently not dependent on MyD88 signaling since the induction of TGF-β-dependent Ab isotypes in response to both oral (Fig. 3) and i.p. (Fig. 4) vaccination with Salmonella-OVA is sustained in the absence of MyD88 signaling. Our analysis has not identified an IL-4-producing cell type that might account for the predominance of the IgG1 response in MyD88−/− mice, or whether IL-4 production is even required for class switching to IgG1 in this setting. Indeed, although IgE responses are abrogated, Ag-specific IgG1 responses are only partially reduced in IL-4-deficient mice (62); in vitro, transient reporter gene assays confirm a differential role for IL-4 in the transcriptional regulation of class switching to these two prototypic Th2-dependent Ig isotypes (63). Although we can conclude that, contrary to our initial expectations, IL-4 is not produced by either Ag-specific T cells (Fig. 5) or iNKT cells (Figs. 7 and 8) in response to oral vaccination of MyD88−/− mice, we do see a very small, but increased, percentage of IL-4+ CD4+Thy1.1− recipient host cells in orally vaccinated MyD88−/− mice (Fig. 6, C and D). Since neither of the specific markers utilized in this study (i.e., Thy1.1 on the adoptively transferred OVA-specific OT2 T cells or CD1d tetramer staining of iNKT cells) was sufficient to identify a potential source of IL-4-producing cells, future studies will require crossing the MyD88 mutation into mice bearing a reporter for IL-4 competent cells (64) to clarify whether the IgG1 produced in response to oral vaccination of MyD88−/− mice is IL-4 dependent.

We do, however, clearly show that both T and iNKT cell effector responses to Salmonella-OVA vaccination are MyD88 dependent. Adoptively transferred TCR transgenic OVA-specific T cells accumulated in the MLN of MyD88−/− mice but failed to make IFN-γ (Fig. 5), in agreement with the impairment of the IFN-γ-dependent OVA-specific IgG2c response to oral vaccination in these mice (Fig. 3). CD1d tetramer staining showed that iNKT cells were activated in response to Salmonella-OVA vaccination in WT but not MyD88−/− mice (Fig. 7) and, correspondingly, the IFN-γ-dependent OVA-specific IgG2c response was reduced by neutralizing Ab to CD1d only in WT mice (Fig. 8). In vitro studies by others have shown impaired IFN-γ production by WT iNKT cells cocultured with MyD88-deficient DCs pulsed with heat-killed virulent Salmonella, suggesting that MyD88-mediated signals in DCs are critical for iNKT cell effector function (65). Other work has shown that CD1d-mediated activation of iNKT cells is critical for the generation of Th1-dependent Ag-specific serum IgG2a/c in diverse autoimmune disease models (66, 67). We show here that the iNKT cell response to an orally delivered live attenuated Salmonella vaccine is also MyD88 dependent.

Taken together, the data presented in this report suggest critical roles for both TLR signaling through MyD88 and the route of immunization in the generation of vaccine-induced serum Ab responses, information essential for future rational vaccine and adjuvant design. It also contributes to the growing evidence that iNKT cells can influence humoral responses to immunization in a CD1d-dependent manner, making the activation of these innate immune cells an attractive strategy for enhancing immune responses to vaccination.

Acknowledgments

We thank Clara Abraham (Yale University), Atsushi Mizoguchi, Rodrigo Mora, and Andrew Stefka (Massachusetts General Hospital) for critical review of the manuscript and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases tetramer facility for CD1d tetramers.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK 55678, the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Grant DK 43551), and Predoctoral Training Fellowships T32 A107529 (to D.W.S.) and F31 AI054229 (to O.I.I.).

Abbreviations used in this paper: iNKT, invariant NKT; DC, dendritic cell; MLN, mesenteric lymph node; WT, wild type.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783– 801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krieg AM. Toll-free vaccines? Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:303–305. doi: 10.1038/nbt0307-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity in B-cell activation and antibody responses. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pulendran B. Tolls and beyond: many roads to vaccine immunity. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1776–1778. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr070454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wickelgren I. Immunology: mouse studies question importance of Toll-like receptors to vaccines. Science. 2006;314:1859–1860. doi: 10.1126/science.314.5807.1859a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Control of B-cell responses by Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2005;438:364–368. doi: 10.1038/nature04267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gavin AL, Hoebe K, Duong B, Ota T, Martin C, Beutler B, Nemazee D. Adjuvant-enhanced antibody responses in the absence of Toll-like receptor signaling. Science. 2006;314:1936–1938. doi: 10.1126/science.1135299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer-Bahlburg A, Khim S, Rawlings DJ. B cell intrinsic TLR signals amplify but are not required for humoral immunity. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3095–3101. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SM, Ko HJ, Shim DH, Yang JY, Park YH, Curtiss R, 3rd, Kweon MN. MyD88 signaling is not essential for induction of antigen-specific B cell responses but is indispensable for protection against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection following oral vaccination with attenuated Salmonella expressing PspA antigen. J Immunol. 2008;181:6447–6455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nemazee D, Gavin A, Hoebe K, Beutler B. Immunology: Toll-like receptors and antibody responses. Nature. 2006;441:E4. doi: 10.1038/nature04875. discussion E4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan MB, Mills DM, Kappler J, Marrack P, Cambier JC. Promotion of B cell immune responses via an alum-induced myeloid cell population. Science. 2004;304:1808–1810. doi: 10.1126/science.1089926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galli G, Pittoni P, Tonti E, Malzone C, Uematsu Y, Tortoli M, Maione D, Volpini G, Finco O, Nuti S, et al. Invariant NKT cells sustain specific B cell responses and memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3984–3989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700191104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godfrey DI, Kronenberg M. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1379–1388. doi: 10.1172/JCI23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leadbetter EA, Brigl M, Illarionov P, Cohen N, Luteran MC, Pillai S, Besra GS, Brenner MB. NK T cells provide lipid antigen-specific cognate help for B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8339–8344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801375105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C. Mucosal immunity and vaccines. Nat Med. 2005;11:S45–S53. doi: 10.1038/nm1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagler-Anderson C. Man the barrier!: strategic defenses in the intestinal mucosa. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:59–67. doi: 10.1038/35095573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrovsky N, Aguilar JC. Vaccine adjuvants: current state and future trends. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang B, Gentsch JR, Glass RI. The role of serum antibodies in the protection against rotavirus disease: an overview. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1351–1361. doi: 10.1086/340103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson HL, Amara RR. T cell vaccines for microbial infections. Nat Med. 2005;11:S25–S32. doi: 10.1038/nm1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjorkbacka H, Kunjathoor VV, Moore KJ, Koehn S, Ordija CM, Lee MA, Means T, Halmen K, Luster AD, Golenbock DT, Freeman MW. Reduced atherosclerosis in MyD88-null mice links elevated serum cholesterol levels to activation of innate immunity signaling pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:416–421. doi: 10.1038/nm1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoiseth SK, Stocker BA. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatfield SN, Charles IG, Makoff AJ, Oxer MD, Dougan G, Pickard D, Slater D, Fairweather NF. Use of the nirB promoter to direct the stable expression of heterologous antigens in Salmonella oral vaccine strains: development of a single-dose oral tetanus vaccine. Biotechnology (N Y) 1992;10:888–892. doi: 10.1038/nbt0892-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore MW, Carbone FR, Bevan MJ. Introduction of soluble protein into the class I pathway of antigen processing and presentation. Cell. 1988;54:777–785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kita E, Emoto M, Yasui K, Yasui K, Katsui N, Nishi K, Kashiba S. Cellular aspects of the longer-lasting immunity against mouse typhoid infection afforded by the live-cell and ribosomal vaccines. Immunology. 1986;57:431–435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi HN, Ingui CJ, Dodge I, Nagler-Anderson C. A helminth-induced mucosal Th2 response alters nonresponsiveness to oral administration of a soluble antigen. J Immunol. 1998;160:2449–2455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duverger A, Jackson RJ, van Ginkel FW, Fischer R, Tafaro A, Leppla SH, Fujihashi K, Kiyono H, McGhee JR, Boyaka PN. Bacillus anthracis edema toxin acts as an adjuvant for mucosal immune responses to nasally administered vaccine antigens. J Immunol. 2006;176:1776–1783. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Goff RD, Zhou D, Mattner J, Sullivan BA, Khurana A, Cantu C, 3rd, Ravkov EV, Ibegbu CC, Altman JD, et al. A modified α-galactosyl ceramide for staining and stimulating natural killer T cells. J Immunol Methods. 2006;312:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamath A, Woodworth JS, Behar SM. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and the development of central memory during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:6361–6369. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alaniz RC, Cummings LA, Bergman MA, Rassoulian-Barrett SL, Cookson BT. Salmonella typhimurium coordinately regulates FliC location and reduces dendritic cell activation and antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:3983–3993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villarino AV, Tato CM, Stumhofer JS, Yao Z, Cui YK, Hennighausen L, O’Shea JJ, Hunter CA. Helper T cell IL-2 production is limited by negative feedback and STAT-dependent cytokine signals. J Exp Med. 2007;204:65–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahoney RT, Krattiger A, Clemens JD, Curtiss R., 3rd The introduction of new vaccines into developing countries, IV: Global access strategies. Vaccine. 2007;25:4003–4011. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bumann D. In vivo visualization of bacterial colonization, antigen expression, and specific T-cell induction following oral administration of live recombinant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4618–4626. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4618-4626.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serre K, Mohr E, Toellner KM, Cunningham AF, Granjeaud S, Bird R, MacLennan IC. Molecular differences between the divergent responses of ovalbumin-specific CD4 T cells to alum-precipitated ovalbumin compared to ovalbumin expressed by Salmonella. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:3558–3566. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schnare M, Barton GM, Holt AC, Takeda K, Akira S, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors control activation of adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:947–950. doi: 10.1038/ni712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snapper CM, Paul WE. Interferon-γ and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cochran JR, Cameron TO, Stern LJ. The relationship of MHC-peptide binding and T cell activation probed using chemically defined MHC class II oligomers. Immunity. 2000;12:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwab SR, Cyster JG. Finding a way out: lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1295–1301. doi: 10.1038/ni1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiow LR, Rosen DB, Brdickova N, Xu Y, An J, Lanier LL, Cyster JG, Matloubian M. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-α/β to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature. 2006;440:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature04606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ajuebor MN. Role of NKT cells in the digestive system, I: Invariant NKT cells and liver diseases: is there strength in numbers? Am J Physiol. 2007;293:G651–G656. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00298.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wingender G, Kronenberg M. Role of NKT cells in the digestive system, IV: The role of canonical natural killer T cells in mucosal immunity and inflammation. Am J Physiol. 2008;294:G1–G8. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00437.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berntman E, Rolf J, Johansson C, Anderson P, Cardell SL. The role of CD1d-restricted NK T lymphocytes in the immune response to oral infection with Salmonella typhimurium. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2100–2109. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brigl M, Bry L, Kent SC, Gumperz JE, Brenner MB. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1230–1237. doi: 10.1038/ni1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yokote H, Miyake S, Croxford JL, Oki S, Mizusawa H, Yamamura T. NKT cell-dependent amelioration of a mouse model of multiple sclerosis by altering gut flora. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1714–1723. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams DH, Eksteen B, Curbishley SM. Immunology of the gut and liver: a love/hate relationship. Gut. 2008;57:838–848. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crispe IN. Hepatic T cells and liver tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:51–62. doi: 10.1038/nri981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mastroeni P, Sheppard M. Salmonella infections in the mouse model: host resistance factors and in vivo dynamics of bacterial spread and distribution in the tissues. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim S, Lalani S, Parekh VV, Vincent TL, Wu L, Van Kaer L. Impact of bacteria on the phenotype, functions, and therapeutic activities of invariant NKT cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2301–2315. doi: 10.1172/JCI33071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harada M, Seino K, Wakao H, Sakata S, Ishizuka Y, Ito T, Kojo S, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M. Down-regulation of the invariant Vα14 antigen receptor in NKT cells upon activation. Int Immunol. 2004;16:241–247. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crowe NY, Uldrich AP, Kyparissoudis K, Hammond KJ, Hayakawa Y, Sidobre S, Keating R, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. Glycolipid antigen drives rapid expansion and sustained cytokine production by NK T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:4020–4027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stanley AC, Zhou Y, Amante FH, Randall LM, Haque A, Pellicci DG, Hill GR, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI, Engwerda CR. Activation of invariant NKT cells exacerbates experimental visceral leishmaniasis. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000028. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyer EH, Goya S, Akbari O, Berry GJ, Savage PB, Kronenberg M, Nakayama T, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Glycolipid activation of invariant T cell receptor+ NK T cells is sufficient to induce airway hyperreactivity independent of conventional CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2782–2787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510282103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hou B, Reizis B, Defranco AL. Toll-like receptors activate innate and adaptive immunity by using dendritic cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic mechanisms. Immunity. 2008;29:272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Debus A, Glasner J, Rollinghoff M, Gessner A. High levels of susceptibility and T helper 2 response in MyD88-deficient mice infected with Leishmania major are interleukin-4 dependent. Infect Immun. 2003;71:7215–7218. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7215-7218.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, Von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 2004;427:154–159. doi: 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iweala OI, Nagler CR. Immune privilege in the gut: the establishment and maintenance of non-responsiveness to dietary antigens and commensal flora. Immunol Rev. 2006;213:82–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kool M, Soullie T, van Nimwegen M, Willart MA, Muskens F, Jung S, Hoogsteden HC, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Alum adjuvant boosts adaptive immunity by inducing uric acid and activating inflammatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:869–882. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spiekermann GM, Nagler-Anderson C. Oral administration of the bacterial superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B induces activation and cytokine production by T cells in murine gut associated lymphoid tissue. J Immunol. 1998;161:5825–5831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaminski DA, Stavnezer J. Stimuli that enhance IgA class switching increase histone 3 acetylation at Sα, but poorly stimulate sequential switching from IgG2b. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:240–251. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Corthesy B. Roundtrip ticket for secretory IgA: role in mucosal homeostasis? J Immunol. 2007;178:27–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kelsall BL, Leon F. Involvement of intestinal dendritic cells in oral tolerance, immunity to pathogens and inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:132–148. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuhn R, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Generation and analysis of IL-4 deficient mice. Science. 1991;254:707–711. doi: 10.1126/science.1948049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mao C, Stavnezer J. Differential regulation of mouse germline Ig γ1 and ε promoters by IL-4 and CD40. J Immunol. 2001;167:1522–1534. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schramm G, Mohrs K, Wodrich M, Doenhoff MJ, Pearce EJ, Haas H, Mohrs M. IPSE/α-1, a glycoprotein from Schistosoma mansoni eggs, induces IgE-dependent, antigen-independent IL-4 production by murine basophils in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178:6023–6027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mattner J, Debord KL, Ismail N, Goff RD, Cantu C, 3rd, Zhou D, Saint-Mezard P, Wang V, Gao Y, Yin N, et al. Exogenous and endogenous glycolipid antigens activate NKT cells during microbial infections. Nature. 2005;434:525–529. doi: 10.1038/nature03408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mattner J, Savage PB, Leung P, Oertelt SS, Wang V, Trivedi O, Scanlon ST, Pendem K, Teyton L, Hart J, et al. Liver autoimmunity triggered by microbial activation of natural killer T cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:304–315. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeng D, Liu Y, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Strober S. Activation of natural killer T cells in NZB/W mice induces Th1-type immune responses exacerbating lupus. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1211–1222. doi: 10.1172/JCI17165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]