Abstract

Background

Mortality rates after aortic valve replacement (AVR) have declined, but little is known about the risk of hospitalization among survivors, and how that has changed over time.

Methods

Among Medicare patients who underwent AVR from 1999–2010 and survived to one year, we assessed trends in 1-year hospitalization rates, mean cumulative length of stay (LOS) (average number of hospitalization days per patient in the entire year), and adjusted annual Medicare payments per patient toward hospitalizations. We characterized hospitalizations by principal diagnosis and mean LOS.

Results

Among 1-year survivors of AVR, 43% of patients were hospitalized within that year, of whom 44.5% were hospitalized within 30 days (19.2% for overall cohort). Hospitalization rates were higher for older (50.3% for >85 years), female (45.1%) and black (48.9%) patients. One-year hospitalization rate decreased from 44.2% (43.5–44.8) in 1999 to 40.9% (40.3–41.4) in 2010. Mean cumulative LOS decreased from 4.8 days to 4.0 days (p <0.05 for trend); annual Medicare payments per patient were unchanged ($5709 to $5737, p=0.32 for trend). The three most common principal diagnoses in hospitalizations were heart failure (12.7%), arrhythmia (7.9%), and postoperative complications (4.4%). Mean LOS declined from 6.0 days to 5.3 days (p <0.05 for trend).

Conclusions

Among Medicare beneficiaries who survived one year after AVR, 3 in 5 remained free of hospitalization; however, certain subgroups had higher rates of hospitalization. After the 30-day period, the hospitalization rate was similar to the general Medicare population. Hospitalization rates and cumulative days spent in hospital decreased over time.

Keywords: aortic valve replacement, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Aortic valve disease is one of the most frequent types of valvular heart disease in the United States (US) (1), and aortic valve replacement (AVR) in appropriate patients with severe stenosis or regurgitation can produce substantial improvements in symptoms and life expectancy.(2) Over time, rates of AVR in the US have increased while mortality rates have declined.(3) Among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing AVR, 1-year mortality declined by 20% from 1999 to 2010. By 2010, almost 9 in 10 patients undergoing AVR were alive after one year.(4)

Survival is often considered to be the success rate of the procedure, but there can be heterogeneity of experience among survivors. Hospitalizations indicate acute events of consequence and impose significant psychological and physical burden on patients, especially in the elderly.(5) There is a paucity of information on the risk of hospitalization among survivors of AVR, and how that has changed over time. Furthermore, there is little information on the timing, duration, causes and costs of these hospitalizations, and the characteristics of patients at higher risk of hospitalization. To date, no large, national studies have assessed and characterized these events. This information is important to better characterize the full range of outcomes among the vast majority of patients who survive the surgery, to provide information that can influence decisions, and to identify targets for improvement.

Accordingly, we analyzed all data for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who survived at least one year after AVR from 1999 through 2010, to describe the trend in hospitalization rates, cumulative hospitalization days and associated costs, and characterized individual hospitalizations by principal diagnosis, length of stay (LOS), and discharge disposition. We analyzed for differences by age, sex, race and receipt of concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

Using inpatient administrative claims data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), we identified all Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries who underwent an AVR between January 1, 1999 and December 31, 2010 and survived at least one year after the procedure. AVR was defined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification procedure codes 35.21 (AVR with bio-prosthesis) and 35.22 (AVR with mechanical prosthesis). We excluded patients who underwent aortic valve repair (35.11) or multi-valvular surgery i.e. concurrent mitral (35.12, 35.23, 35.24) or tricuspid (35.14, 35.27, 35.28) valve repair/replacement, as well as those with endocarditis (421.0, 421.1, 421.9). We identified patients with concomitant CABG using the codes 36.10 to 36.16. If a patient had more than one AVR during an index year, we selected the first hospitalization. For patients who underwent AVR during 2010 we used 2011 claims data to permit 1-year follow-up. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Yale University Human Investigation Committee.

Patient Characteristics

We collected information on patients’ age, sex, race (white, black, other) and comorbidities. Comorbidities included those used for profiling hospitals by the CMS 30-day mortality measures for acute myocardial infarction (6) and heart failure.(7) They were identified from secondary discharge diagnosis codes in the index hospitalization for AVR as well as principal or secondary diagnosis codes of all inpatient hospitalizations up to one year prior. Comorbidity data from 1998 were used for patients hospitalized for AVR in 1999.

Outcomes

Primary outcome was all-cause hospitalization within one year of discharge for AVR. In addition, we studied mean cumulative length of stay (mean cumulative LOS) and annual Medicare payments per patient toward hospitalizations. Mean cumulative LOS was defined as the average number of hospitalization days (excluding the index hospitalization) per patient in the entire year post index AVR hospitalization.

We further characterized individual hospitalizations by principal diagnosis, mean length of stay (mean LOS) (for all hospitalizations excluding the index hospitalization), and discharge disposition. Major discharge disposition included discharge to home, home with home care, skilled nursing facility, long term care facility, hospice or rehabilitation.

We reported Medicare payments as both unadjusted and adjusted for inflation. To calculate adjusted payments we used the annual Consumer Price Index inflation rate reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics to adjust the dollar amounts with year 2000 expenditure as baseline.(8) We have chosen not to use the medical care component of the CPI for inflation adjustments because of expressed concerns that it can overstate the growth in health care costs.(9)

Statistical Analysis

We reported baseline characteristics in 2-year intervals and outcomes in alternate years to simplify presentation. We used the Cochran-Armitage test to examine the significance of trends and Cox proportional hazards regression model to assess annual trends in 1-year all-cause hospitalization rates, adjusted for patient characteristics. We fitted separate Cox models to assess the annual trends for age-sex-race subgroups and with and without CABG groups. All models included an ordinal time variable, ranging from 0 to 11, corresponding to years 1999 (time=0) through 2010 (time=11), to represent the adjusted annual trends in 1-year hospitalization rate. All statistical analysis was conducted using SAS 9.3 64-bit version (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). All statistical tests were 2-sided at a significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of the 337,846 patients who underwent AVR from 1999 to 2010, 293,853 patients survived to at least one year, comprising the study cohort. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Between 1999–2000 and 2009–2010, the proportion of patients ≥85 years of age increased from 7.8% to 12.7%, while the proportion of female patients decreased from 42.3% to 39.9%. Patients increasingly had coexistent hypertension (54.1% to 62.9%), diabetes (20.8 to 25.9%) and renal failure (1.8% to 7.8%). The proportion of patients who underwent concomitant CABG along with AVR decreased from 56.2% to 44.8%. (All P for trend <0.05)

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patient characteristics | No. (%) of Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | 2003–2004 | 2005–2006 | 2007–2008 | 2009–2010 | |

| No. of patients | 43043 | 46668 | 49624 | 50452 | 49935 | 54131 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 76.0 (5.8) | 76.2 (5.9) | 76.3 (6.0) | 76.4 (6.1) | 76.5 (6.3) | 76.7 (6.5) |

| Female* | 18199 (42.3) | 19401 (41.6) | 20446 (41.2) | 20425 (40.5) | 20193 (40.4) | 21607 (39.9) |

| White | 40399 (93.9) | 43782 (93.8) | 46386 (93.5) | 47285 (93.7) | 46879 (93.9) | 50736 (93.7) |

| Black | 1410 (3.3) | 1470 (3.1) | 1643 (3.3) | 1562 (3.1) | 1552 (3.1) | 1677 (3.1) |

| Other race@# | 1234 (2.9) | 1416 (3.0) | 1595 (3.2) | 1605 (3.2) | 1504 (3.0) | 1718 (3.2) |

| Risk factors and cardiovascular conditions | ||||||

| Hypertension* | 23300 (54.1) | 27240 (58.4) | 30096 (60.6) | 30550 (60.6) | 31526 (63.1) | 34045 (62.9) |

| Diabetes* | 8933 (20.8) | 10309 (22.1) | 11789 (23.8) | 12593 (25.0) | 12881 (25.8) | 14045 (25.9) |

| Atherosclerotic disease* | 26469 (61.5) | 28945 (62.0) | 30794 (62.1) | 30529 (60.5) | 29824 (59.7) | 31051 (57.4) |

| Unstable angina* | 2208 (5.1) | 2021 (4.3) | 1746 (3.5) | 1475 (2.9) | 1320 (2.6) | 1227 (2.3) |

| Prior heart failure* | 7122 (16.5) | 7355 (15.8) | 7549 (15.2) | 7186 (14.2) | 7170 (14.4) | 8008 (14.8) |

| Prior myocardial infarction# | 1509 (3.5) | 1606 (3.4) | 1639 (3.3) | 1688 (3.3) | 1718 (3.4) | 2046 (3.8) |

| Stroke | 404 (0.9) | 463 (1.0) | 412 (0.8) | 478 (0.9) | 499 (1.0) | 562 (1.0) |

| Cerebrovascular disease other than stroke* | 1726 (4.0) | 1866 (4.0) | 1813 (3.7) | 1881 (3.7) | 1819 (3.6) | 1902 (3.5) |

| Peripheral vascular disease* | 2176 (5.1) | 2493 (5.3) | 2721 (5.5) | 2821 (5.6) | 2906 (5.8) | 3049 (5.6) |

| Other conditions | ||||||

| Malnutrition* | 450 (1.0) | 547 (1.2) | 645 (1.3) | 801 (1.6) | 1193 (2.4) | 1752 (3.2) |

| Dementia* | 468 (1.1) | 540 (1.2) | 648 (1.3) | 699 (1.4) | 752 (1.5) | 960 (1.8) |

| Functional disability# | 343 (0.8) | 363 (0.8) | 382 (0.8) | 353 (0.7) | 442 (0.9) | 482 (0.9) |

| Renal failure* | 794 (1.8) | 1099 (2.4) | 1385 (2.8) | 2129 (4.2) | 3264 (6.5) | 4212 (7.8) |

| Respiratory failure* | 849 (2.0) | 870 (1.9) | 887 (1.8) | 1060 (2.1) | 1464 (2.9) | 1829 (3.4) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease* | 7710 (17.9) | 8913 (19.1) | 9517 (19.2) | 10131 (20.1) | 8577 (17.2) | 7839 (14.5) |

| Pneumonia* | 2507 (5.8) | 2776 (5.9) | 3036 (6.1) | 3352 (6.6) | 3701 (7.4) | 4285 (7.9) |

| Cancer# | 2012 (4.7) | 2099 (4.5) | 2249 (4.5) | 2290 (4.5) | 2213 (4.4) | 2353 (4.3) |

| Liver disease# | 205 (0.5) | 258 (0.6) | 278 (0.6) | 296 (0.6) | 295 (0.6) | 350 (0.6) |

| Trauma in past year* | 1179 (2.7) | 1418 (3.0) | 1722 (3.5) | 1828 (3.6) | 1758 (3.5) | 1734 (3.2) |

| Major psychiatric disorders# | 359 (0.8) | 423 (0.9) | 413 (0.8) | 420 (0.8) | 489 ( 1.0) | 557 (1.0) |

| Depression* | 898 (2.1) | 1171 (2.5) | 1550 (3.1) | 1509 (3.0) | 1642 (3.3) | 1722 (3.2) |

Other race includes Asian, Hispanic, North American Native, or other not specified.

P < 0.05

P < 0.001

Outcomes

One-year Hospitalizations after AVR

Overall, 43% patients had at least one hospitalization within one year of index hospitalization for AVR. The 1-year crude hospitalization rate (95% CI) decreased from 44.2% (43.5–44.8) in 1999 to 40.9% (40.3–41.4) in 2010. Crude hospitalization rates stratified by age, sex, race and receipt of concomitant CABG are shown in Table 2. Over time, the rate of 1-year hospitalizations decreased for all age groups. Among, patients ≥85 years, who had the overall highest rate of hospitalizations, 1-year hospitalizations declined from 52.2% (49.8–54.7) to 48.0% (46.3–49.7) while in the younger (65–74 years) age group it declined from 41.1% (40.0–42.1) to 36.7% (35.8–37.6). Women had higher 1-year hospitalization rates than men although both groups experienced declines over time [women: 46.5% (45.5–47.5) to 42.2% (41.3–43.2); men: 42.5% (41.6–43.3) to 39.9% (39.2–40.7)]. Among race subgroups, black patients had higher hospitalization rates than white patients and had minimal decline over time [48.6% (44.9–52.3) to 47.6% (44.2–50.9)]. Hospitalization rates tended to be higher overall in the group with concomitant CABG than isolated AVR but both groups showed decline over time.

Table 2.

Trend in 1-year hospitalization rate, overall and by sub groups

| 1-year hospitalization rate %, (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Overall | 44.2 (43.5–44.8) | 43.9 (43.3–44.6) | 43.5 (42.9–44.2) | 42.8 (42.2–43.5) | 42.5 (41.9–43.1) | 41.9 (41.3–42.5) | 40.9 (40.3–41.4) |

| 65–74 | 41.1 (40.0–42.1) | 40.3 (39.3–41.3) | 39.4 (38.4–40.3) | 39.1 (38.1–40.0) | 38.3 (37.3–39.3) | 37.2 (36.3–38.1) | 36.7 (35.8–37.6) |

| 75–84 | 45.6 (44.6–46.5) | 45.5 (44.6–46.4) | 45.6 (44.7–46.4) | 44.2 (43.4–45.1) | 44.2 (43.3–45.0) | 43.5 (42.7–44.4) | 42.3 (41.4–43.1) |

| ≥85 | 52.2 (49.8–54.7) | 51.7 (49.5–53.9) | 51.0 (48.9–53.1) | 51.2 (49.2–53.3) | 49.7 (47.8–51.6) | 50.6 (48.9–52.3) | 48.0 (46.3–49.7) |

| Female | 46.5 (45.5–47.5) | 46.5 (45.5–47.5) | 45.9 (44.9–46.9) | 44.4 (43.5–45.4) | 44.9 (43.9–45.9) | 44.6 (43.6–45.5) | 42.2 (41.3–43.2) |

| Male | 42.5 (41.6–43.3) | 42.1 (41.3–42.9) | 41.9 (41.1–42.7) | 41.7 (41.0–42.5) | 40.8 (40.0–41.6) | 40.1 (39.4–40.9) | 39.9 (39.2–40.7) |

| Black | 48.6 (44.9–52.3) | 50.8 (47.1–54.5) | 50.8 (47.3–54.3) | 47.6 (44.1–51.2) | 47.2 (43.6–50.8) | 45.7 (42.2–49.1) | 47.6 (44.2–50.9) |

| White | 43.9 (43.2–44.6) | 43.7 (43.0–44.3) | 43.2 (42.6–43.9) | 42.7 (42.1–43.4) | 42.3 (41.6–42.9) | 41.7 (41.1–42.3) | 40.6 (40.0–41.2) |

| Other | 46.6 (42.4–50.7) | 44.4 (40.6–48.2) | 44.7 (41.2–48.2) | 41.4 (38.1–44.7) | 44.9 (41.4–48.4) | 44.0 (40.6–47.4) | 41.4 (38.2–44.7) |

| AVR with CABG | 45.9 (45.0–46.8) | 45.5 (44.6–46.4) | 45.2 (44.3–46.0) | 44.7 (43.9–45.6) | 43.8 (42.9–44.7) | 43.5 (42.7–44.4) | 42.8 (41.9–43.7) |

| Isolated AVR | 41.9 (40.9–42.9) | 42.1 (41.1–43.0) | 41.7 (40.8–42.6) | 40.7 (39.8–41.6) | 41.3 (40.4–42.1) | 40.5 (39.7–41.3) | 39.3 (38.5–40.1) |

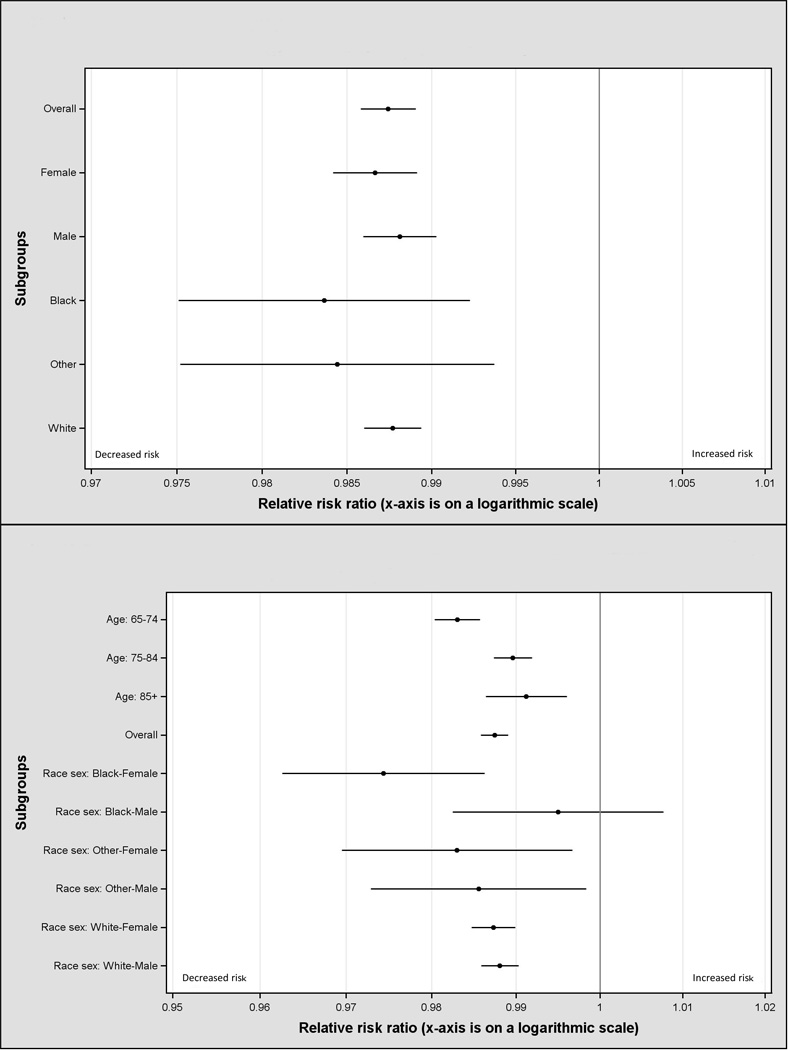

These findings remained unchanged after adjustment for patient characteristics. Compared to 1999, the adjusted hazard ratio representing the annual change in 1-year all-cause hospitalization rate was 0.987 (95% CI, 0.986–0.989). We analyzed race-sex sub groups to evaluate a race-sex interaction and found that black-male patient’s had no significant decline in 1-year hospitalizations in contrast to all other race-sex sub groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Risk-adjusted annual hazard ratio of 1-year hospitalization, overall and by subgroups. The hazard ratios represent the annual change in readmission rate after adjustment for patient characteristics, as estimated by the cox model.

Among those patients with 1-year hospitalizations, in a large proportion the first hospitalization occurred within 30 days (44.5%). Over time, the 30-day hospitalization rate declined from 19.7% (19.1–20.2) in 1999 to 18.2% (17.8–18.7) in 2010 and proportion of patients hospitalized for the first time in the 31–365 day period declined from 24.5% (24.0–25.1) to 22.6% (22.1–23.1) (Appendix Table 1).

Although the 1-year hospitalization rate decreased overall, among those patients with 1-year hospitalizations, the average number of hospitalizations remained similar over time (1.80 hospitalizations per patient in 1999 and 1.83 in 2010) (Appendix Table 1).

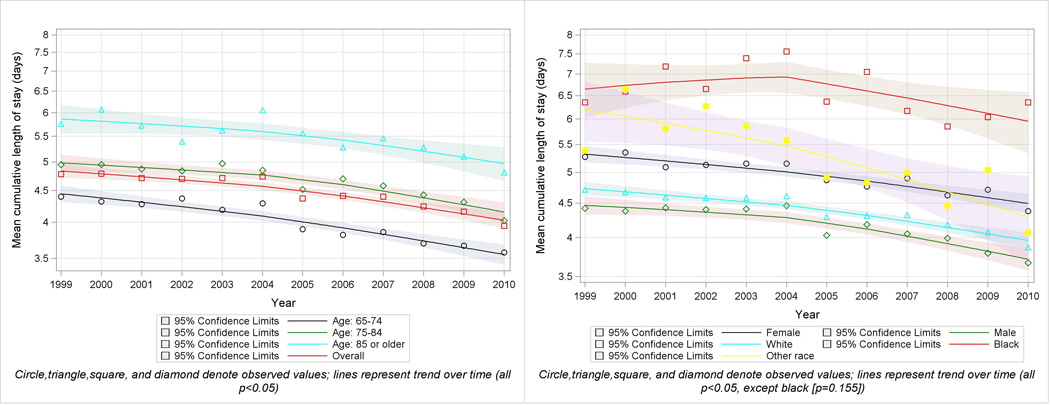

Mean Cumulative Length of Stay and Annual Medicare Payments per Patient

Overall, the mean cumulative LOS (average number of hospitalization days per patient in the entire year post AVR) decreased from 4.8 days in 1999 to 4.0 days in 2010 (p<0.05 for trend). It declined among all subgroups of age, sex and receipt of CABG. Among race subgroups, in black patients the mean cumulative LOS was unchanged (6.4 days in both in 1999 and 2010, p = 0.22 for trend) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trend in mean cumulative LOS, overall and by subgroups

Unadjusted annual Medicare payments per patient toward hospitalizations increased from $5524 in 1999 to $7265 in 2010. However, adjusted for inflation, it remained unchanged from $5709 in 1999 to $5737 in 2010 (p = 0.32 for trend). Older patients had higher adjusted annual CMS payments for hospitalizations, and among patients ≥85 years it increased over time from $6043 per patient in 1999 to $6607 per patient in 2010 (P<0.05 for trend) (Appendix Table 2).

Characteristics of the Hospitalizations

The top 5 principal diagnoses combined explained only about 31.1% of hospitalizations. The three most common principal diagnoses for hospitalizations were heart failure (12.7%), arrhythmia (7.9%), and postoperative complications [hemorrhage, post-operative shock or surgical site complications] (4.4%), and the proportions of these 3 principal diagnoses remained similar over all the study years.

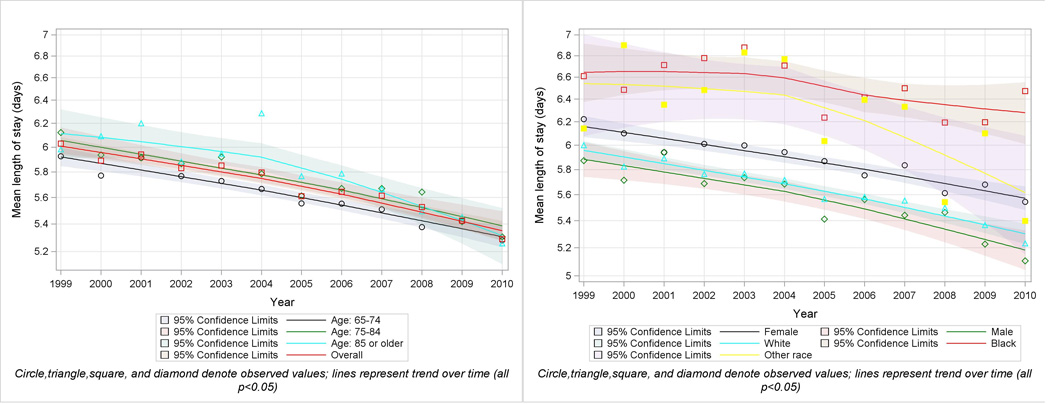

The mean LOS per hospitalization declined from 6.0 days to 5.3 days. All subgroups showed decline in mean LOS. Mean LOS for black patients showed a minimal decline (from 6.6 days to 6.5 days) (Figure 3) Proportion of prolonged hospitalizations (LOS >30 days) declined over time as well from 2.8% to 2.2%. Discharges to home decreased over time (48.6% to 34.5%), while discharges to home with home care (12.2% to 17.7%) and to skilled nursing facilities (10.6% to 14.7%) increased (Appendix Figure 1) (All above P<0.05 for trend).

Figure 3.

Trend in mean LOS, overall and by sub groups

COMMENT

Among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who survived one year after AVR – which represented 87% of patients undergoing the surgery – we found that 3 out of 5 patients were free from hospitalization. Moreover, about half of those hospitalized had their first hospitalization within 30 days. Older, female, black and concomitant CABG patients had higher hospitalization rates. However, there were continual improvements in 1-year hospitalization rate and mean cumulative LOS over time.

Studies of long-term outcomes after AVR are limited to measuring mortality.(10, 11) To our knowledge, in the US, this is the first nationally representative study addressing long-term hospitalizations among AVR survivors. Most studies evaluating hospitalizations after cardiac surgery have assessed shorter time frames, such as 30 days.(12) We focused specifically on survivors in order to understand the heterogeneity in outcomes among the majority of patients who survive AVR, those who most studies would consider a success. This study also provides useful information for those who ask what they can expect if they do survive.

We found that among 1-year survivors of AVR, 43% were hospitalized in the year after surgery. Of those, almost half were hospitalized within 30 days, indicating the critical need to monitor patients closely during the 30 day post-surgery period of heightened risk. Nevertheless, among the patients who do not require a hospitalization during this 30-day period, which was the case for 4 in 5 patients in the cohort, the hospitalization rate is similar to the Medicare basal hospitalization rate of 23%.(13) These findings indicate that recovery is quite good for the majority of these older individuals.

Furthermore, over the study period we observed a decline in hospitalization rates and mean cumulative LOS despite the increasing age and burden of comorbidities in the population. Improvements were seen in both the isolated AVR and concomitant CABG groups. Reductions in post-operative complications (14) over time and improvements in the management of valve recipients in the ambulatory setting are likely contributors to this decline. The increased usage of bio-prosthetic valves (4) may have also played a role by reducing bleeding complications. To further improve outcomes, focused efforts on the post-operative and ambulatory care of AVR patients, especially during the first 30 days, are needed; the emergence of public reporting in cardiac surgery may provide an additional impetus to reduce re-hospitalizations.(15)

However, it was notable that among patients who did get hospitalized following discharge after AVR, the mean number of hospitalizations remained unchanged over time. Thus, there is room for improvement in preventing multiple hospitalizations, and this highlights the need for increased vigilance in the care of re-hospitalized patients.

The top three causes for hospitalizations remained similar over time with heart failure being the most common. However, even the top five causes for hospitalization combined accounted for less than a third of all hospitalizations, indicating that patients are hospitalized for a variety of reasons beyond the reason for the initial admission. This has been observed with other cardiovascular conditions such as heart failure, and patients after discharge seem to have a period of generalized heightened risk for acute events, which extends up to many months, a condition termed post-hospital syndrome.(16, 17)

The mean LOS per hospitalization decreased over time and compared with the LOS for all hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries, it was longer by only 0.6 days.(13) Although mean cumulative LOS and mean LOS declined over time, annual Medicare payments per patient toward hospitalizations remained unchanged. This may reflect the changing population of AVR recipients to that is older and with more comorbidity, necessitating greater resources. The increase in costs may also be due in part to the generalized increase in the costs of in-hospital care.(18)

Subgroup analysis revealed important differences in hospitalization rates among different patient populations. Patients with concomitant CABG, a group known to have higher mortality compared with isolated AVR, (4) had higher hospitalization rates among survivors as well. Older age and female sex were also associated with higher hospitalization rates, but findings have been mixed in previous studies.(19, 20) In addition, black patients were associated with higher rates of hospitalization similar to prior literature in surgical patients.(19, 21) Although all subgroups experienced a decline in crude hospitalization rates over time, the decline was unequal. Black patients experienced only a 2.1% relative decline in hospitalizations versus 7.5% for white patients. In the risk adjusted model, black-male patients specifically had no significant change in the hospitalization rate in contrast to all other sub groups. Further, among black patients the mean cumulative LOS was unchanged over time and the mean LOS of hospitalizations only showed a minimal decline. These findings call for increased attention to these subgroups after AVR due to their vulnerability for re-hospitalizations, in order to eliminate disparities and improve outcomes.

Moving forward, steady improvements in mortality (4) and our findings of decreased need for hospitalization among survivors over time, indicate that surgical AVR is continually evolving into a safer and effective procedure. While the advent of percutaneous devices has been a disruptive innovation in the treatment of aortic valve disease, the outcomes of patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement have never been better, and continue to improve. This elevates the benchmark that these newer, more expensive and labor-intensive therapies need to supersede.

Our study has a few limitations. First, data were limited to Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, and conclusions drawn from this population may not apply to patients enrolled in Medicare managed care programs, where enrollment has increased over time, as well as for patients younger than 65 years. Second, comorbidity information from administrative data may not entirely capture the medical complexity of the patient, and also the pattern and extent of coding for comorbidities may have changed over time. Third, other factors may have influenced the observed trends like changes in patient selection and acuity, surgical factors, social factors and health care system changes; given the administrative nature of our data we are unable to deeply explore the reasons for decreased hospitalizations over time.

CONCLUSIONS

Among Medicare beneficiaries surviving to one year after AVR, 3 in 5 were free from hospitalization, indicating good recovery for the majority of patients. After an initial 30-day period of increased risk these patients had a hospitalization rate similar to the general Medicare population. The hospitalization rate declined from 1999 to 2010; however, certain subgroups had higher rates of hospitalization, which warrants increased attention.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported by grant 1U01HL105270-03 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Dodson is supported by the NIH National Institute of Aging grant R03AG045067, a T. Franklin Williams Scholarship Award (funding by: Atlantic Philanthropies, Inc, the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine-Association of Specialty Professors, and the American College of Cardiology).

Dr. Krumholz is the recipient of a research grant from Medtronic, Inc. through Yale University and is chair of a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

Other authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: A population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368(9540):1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarz F, Baumann P, Manthey J, et al. The effect of aortic valve replacement on survival. Circulation. 1982;66(5):1105–1110. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.66.5.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JM, O'Brien SM, Wu C, Sikora JA, Griffith BP, Gammie JS. Isolated aortic valve replacement in north america comprising 108,687 patients in 10 years: Changes in risks, valve types, and outcomes in the society of thoracic surgeons national database. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2009;137(1):82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barreto-Filho JA, Wang Y, Dodson JA, et al. Trends in aortic valve replacement for elderly patients in the united states, 1999–2011. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310(19):2078–2085. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Annals of internal medicine. 1993;118(3):219–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, et al. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with an acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006;113(13):1683–1692. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, et al. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113(13):1693–1701. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of labor, bureau of labor statistics (us) consumer price index. Http://www.Bls.Gov/cpi/.

- 9.Berndt ERDC, Frank RG, Newhouse JP, Triplett JE. Chapter 3 - medical care prices and output. Handbook of Health Economics. 2000;1 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brennan JM, Edwards FH, Zhao Y, O'Brien SM, Douglas PS, Peterson ED. Long-term survival after aortic valve replacement among high-risk elderly patients in the united states: Insights from the society of thoracic surgeons adult cardiac surgery database, 1991 to 2007. Circulation. 2012;126(13):1621–1629. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.091371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashikhmina EA, Schaff HV, Dearani JA, et al. Aortic valve replacement in the elderly: Determinants of late outcome. Circulation. 2011;124(9):1070–1078. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.987560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox JP, Suter LG, Wang K, Wang Y, Krumholz HM, Ross JS. Hospital-based, acute care use among patients within 30 days of discharge after coronary artery bypass surgery. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2013;96(1):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.03.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medpac, a data book: Healthcare spending and the medicare program. Washington: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.ElBardissi AW, Aranki SF, Sheng S, O'Brien SM, Greenberg CC, Gammie JS. Trends in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting: An analysis of the society of thoracic surgeons adult cardiac surgery database. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2012;143(2):273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shahian DM, Edwards FH, Jacobs JP, et al. Public reporting of cardiac surgery performance: Part 2--implementation. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2011;92(3 Suppl):S12–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome--an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368(2):100–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1212324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309(4):355–363. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moses H, 3rd, Matheson DH, Dorsey ER, George BP, Sadoff D, Yoshimura S. The anatomy of health care in the united states. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310(18):1947–1963. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hannan EL, Zhong Y, Lahey SJ, et al. 30-day readmissions after coronary artery bypass graft surgery in new york state. JACC Cardiovascular interventions. 2011;4(5):569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaccarino V, Lin ZQ, Kasl SV, et al. Sex differences in health status after coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation. 2003;108(21):2642–2647. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097117.28614.D8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Joynt KE. Disparities in surgical 30-day readmission rates for medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. Annals of surgery. 2014 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.