Abstract

Alcohol cue reactivity, operationalized as a classically conditioned response to an alcohol related stimulus, can be assessed by changes in physiological functions such as heart rate variability (HRV), which reflect real time regulation of emotional and cognitive processes. Although ample evidence links drinking histories to cue reactivity, it is unclear whether in-the-moment cue reactivity becomes coupled to a set of consolidated beliefs about the effects of alcohol (i.e., expectancies) and whether treatment helps dissociate the relation of positive versus negative expectancies to cue reactivity. This study examined the relationship between reactivity to alcohol picture cues and alcohol expectancies in two groups of emerging adults: an inpatient sample with alcohol use disorders (n=28) and a college student sample who previously were mandated to a brief intervention for violating university policies about alcohol use in residence halls (n=43). Sequential regression analysis was conducted using several HRV indices and self-report arousal ratings as cue reactivity measures. Results indicated that the relationship between cue reactivity and negative alcohol outcome expectancies differed for the two groups. Greater cue reactivity, assessed using HRV indices, was associated with more negative expectancies in the inpatient sample but with less negative expectancies in the mandated student sample, while an opposite trend was found for subjective arousal. The present findings highlight the importance of characterizing cue reactivity through multi-dimensional assessment modalities that include physiological markers such as HRV.

Keywords: Alcohol outcome expectancie, Heart rate variability, Cue reactivity, Alcohol use disorders

1. Introduction

Alcohol use behaviors are influenced by moment-to-moment, interrelated changes in internal states and the environment (Bates & Buckman, 2011; Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008), as well as learning retained from prior experiences that results in a set of beliefs about the effects of consuming alcohol (i.e., alcohol outcome expectancies; Drobes, Carter, & Goldman, 2009; Field, Schoenmakers, & Wiers, 2008; Goldman, Del Boca, & Darkes, 1999; Tiffany, 1990). Understanding the interplay of instantaneous and persistent motivational precursors of drinking has implications for prevention and treatment of alcohol misuse. This study examined the interrelation of conscious, cognitive expectancies about alcohol effects with automatic visceral reactivity to alcohol cues.

Heart rate variability (HRV; variability in the time intervals between heart beats) is a neurocardiac process that is well-suited for the study of motivational states of import to addictive behaviors, such as those related to cue reactivity (Elliot, Payen, Brisswalter, Cury, & Thayer, 2011; Porges, 2007; Thayer, Hansen, Saus-Rose, & Johnsen, 2009). Previous research demonstrated that neurocardiac information processing is involved in alcohol cue reactivity, and suggested that HRV's relation to drinking intensifies as experience with alcohol increases over time (Garland, Franken, Sheetz, & Howard, 2012; Jansma, Breteler, Schippers, De Jong, & Van Der Staak, 2000; Mun, von Eye, Bates, & Vaschillo, 2008). Thus, aberrant, in-the-moment HRV reactivity to alcohol cues may mechanistically contribute to the maintenance of unintended, or maladaptive drinking behaviors, even in the face of anticipated negative outcomes and conscious intentions not to drink (Tiffany, 1990).

In addition to instantaneous neurocardiac changes, cue exposure activates associative memory processes that give rise to expectancies about the effects of consuming alcohol (Cooney, Gillespie, Baker, & Kaplan, 1987). These alcohol outcome expectancies are important cognitive contributors to motivational pathways underlying alcohol use (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Engels, & Gmel, 2007; Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005). In particular, positive and negative expectancies may bear different relations to alcohol use behaviors in persons with or without alcohol use disorders (AUD). Greater negative, but not positive, alcohol outcome expectancies may be protective in problem drinkers (Jones & McMahon, 1994; Ramsey et al., 2000), yet be associated with more problems in non-dependent college drinkers (Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007; Schulenberg et al., 2001).

A better knowledge of the associations of alcohol cue reactivity with positive and negative expectancies could be important for screening high-risk individuals and those who may be more receptive to treatment. To the best of our knowledge, this relationship has not been directly examined in treatment and non-treatment samples within the same study. The present study examined the relationship of HRV reactivity and subjectively reported arousal in response to alcohol picture cues, to alcohol outcome expectancies, in two groups of young adults: one being treated in a residential addictions treatment facility for AUD and other drug use disorders, and the other similarly aged college students who were not alcohol dependent, but were deemed to be at-risk for alcohol problems by virtue of being mandated to a brief university-based alcohol intervention (Buckman, White, & Bates, 2010).

We expected that the inpatient group would report a larger number of positive and negative alcohol outcome expectancies (see Jones, Corbin, & Fromme, 2001 for review), and evidence lower basal HRV, compared to the mandated college students (Ingjaldsson, Laberg, & Thayer, 2003). As a result of their deeper involvement and more extensive experiences with alcohol, inpatients' HRV reactivity to alcohol cues may be more strongly linked to alcohol expectancies, compared to the mandated college sample. Yet, because treatment may disrupt this relationship, it was tentatively hypothesized that this association would be less robust for negative expectancies in the inpatient sample. A dissociation between in-the-moment physiological reactivity and cognitive expectancies may provide evidence as to how cue reactivity mechanistically functions to support or hinder behavior change during treatment.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

We recruited 71 young adults from two sources. The mandated sample included 43 young adults who had completed a brief intervention program for students cited for infractions of university substance use policies two years prior (described previously in Buckman et al., 2010). Data from two students were excluded because their infractions were not alcohol-related. The inpatient sample included 28 young adult consecutive admissions from a treatment facility for substance use disorders. Data from five were excluded because they did not meet criteria for an AUD, and data from one were excluded because of an atypical heart rhythm; 66.7% were diagnosed with alcohol dependence, 33.3% were diagnosed with alcohol abuse, and 96.3% had a co-occurring drug dependence diagnosis. The average period between treatment admission and the laboratory session was 42.2±30.8 days. The full sample averaged 21.6 years of age (SD=2.8) and 13.6 years of education (SD=1.7) and 40.5% were female. The ethnic composition was European American (73.0%), Asian (17.6%), African American (2.7%), and mixed or other (6.8%).

2.2. Measures

Positive and negative alcohol expectancies were measured using the well-validated 38-item, Comprehensive Effects of Alcohol Questionnaire (Fromme, Stroot, & Kaplan, 1993). Alcohol and drug use behaviors were assessed as in Vaschillo et al. (2008). Five commonly used indices of HRV were calculated from recorded electrocardiogram (ECG; see Buckman et al., 2010 for recording details): the percentage of successive normal beat-to-beat intervals that differed by more than 50 ms (pNN50), the standard deviation of beat-to-beat intervals (SDNN), high frequency (HF) HRV, low frequency (LF) HRV, and very low frequency (VLF) HRV (Task Force, 1996).

2.3. Procedures

Details of the cue reactivity paradigm were previously published (Bates & Buckman, 2011; Buckman et al., 2010). Briefly, participants individually completed a 4-hour session of questionnaires, ECG recordings, cue exposure, and memory tasks (memory data not included). Alcohol-related picture stimuli were from the Normative Appetitive Picture System (NAPS; Stritzke, Breiner, Curtin, & Lang, 2004), as well as Tapert et al. (2003) and Mun et al. (2008). Each of 30 alcohol cues was shown for 5 s. Participants verbally provided an arousal rating (Bradley & Lang, 1994) during the 5-second inter-picture interval. Heart rate (HR), HRV and verbal arousal responses were computed for 5-minute baseline and alcohol picture cue conditions.

2.4. Analysis

Testing for multivariate outliers (Mahalanobis distance, criterion p<.001, de Maesschalck, Jouan-Rimbaud, & Massart, 2000) identified none. Sequential regression analyses examined the relationship between alcohol cue reactivity and alcohol expectancies, and whether this relationship differed for the inpatient and mandated samples. Negative and positive expectancies were examined as separate criterion variables. The six physiological indices were analyzed separately because they are highly correlated, but can be differentiated mechanistically. To measure cue reactivity, we regressed each HR and HRV index during alcohol cue exposure, on the respective baseline measure of that index, and computed the residual score. To obtain residual scores for the subjective arousal ratings, self-reported response to a neutral cue condition was used as a baseline because self-arousal ratings were not collected at baseline. Higher residual scores indicate higher levels of cue reactivity. Each cue reactivity score and group (1=inpatient, 0=mandated student) were entered in Step 1 of the sequential regression model. The interaction term between cue reactivity and group was entered in Step 2. Gender was not included in the models as men and women did not vary on any reactivity measures or expectancies (all p>.05).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analysis

The inpatient group (M=23.7, SD=3.5) was, on average, older than the mandated student group (M=20.5, SD=1.6) and less educated (M=12.3, SD=1.8 versus M=14.3, SD=1.1). Inpatients reported significantly more negative, but not positive, alcohol expectancies, compared to the mandated students (Table 1). At baseline, inpatients had lower pNN50, SDNN, HF HRV, LF HRV and VLF HRV than the mandated students (Table 1). During alcohol cue presentation, average residualized change scores (i.e., cue reactivity) of HR, pNN50, SDNN, HF HRV, LF HRV, and VLF HRV did not differ between groups, nor did subjective arousal.

Table 1.

Physiological arousal at baseline, physiological cue reactivity and subjective arousal ratings expressed as residual scores, and alcohol expectancies by recruitment source.

| Students | Inpatients | t-Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean physiological activity during baseline | |||

| HR (beats per min) | 68.8 (8.6) | 73.0 (9.1) | −1.75 |

| pNN50 (%) | 31.5 (19.3) | 21.0 (19.0) | 2.07* |

| SDNN (log) | 4.1 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.37* |

| HF HRV (log) | 6.7 (0.8) | 5.9 (1.3) | 3.00* |

| LF HRV (log) | 6.8 (0.8) | 6.2 (1.0) | 2.60* |

| VLF HRV (log) | 6.5 (0.6) | 5.6 (0.8) | 4.72* |

| Mean physiological reactivity during cue exposure | |||

| HR (beats per min) | −0.3 (2.9) | 0.5 (2.5) | −1.12 |

| pNN50 (%) | 0.7 (10.7) | −1.4 (10.5) | 0.76 |

| SDNN (log) | 0.03 (0.2) | −0.05 (0.3) | 1.20 |

| HF HRV (log) | 0.1 (0.5) | −0.2 (0.9) | 1.94 |

| LF HRV (log) | 0.1 (0.5) | −0.2 (0.6) | 1.73 |

| VLF HRV (log) | 0.1 (0.6) | −0.2 (0.7) | 1.79 |

| Subjective arousal ratings | −0.2 (1.1) | 0.4 (1.4) | −1.72 |

| Mean alcohol expectancy scores | |||

| Negative expectancy score | 40.0 (10.7) | 47.5 (12.0) | − 2.54* |

| Positive expectancy score | 53.8 (9.7) | 58.1 (10.4) | −1.65 |

Notes: Numbers in parentheses indicate standard deviations.

p<05.

3.2. Alcohol outcome expectancies and alcohol cue reactivity

In line with the preliminary analysis, after adjusting for individual differences in cue reactivity for all indices, the inpatient group showed higher levels of negative expectancies, compared to the mandated group (HR, b=.29, t(62)=2.37; pNN50, b=.30, t(62)=2.42; SDNN, b=.29, t(62)=2.37; HF HRV, b=.30, 62)=2.35; LF HRV, b=.28, t(62)=2.26; VLF HRV, b=.30, t(62)=2.37; Subjective Arousal, b=.30, t(62)=2.37; all p<.05).

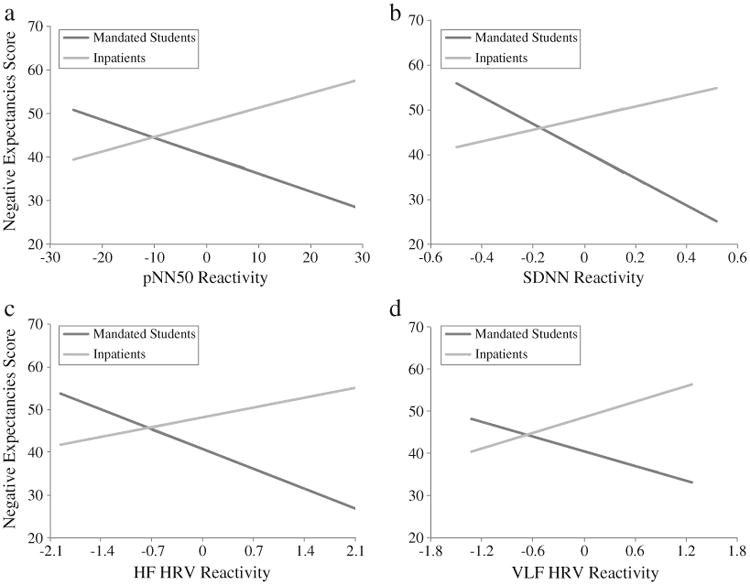

There was also a significant group difference in the association between alcohol cue reactivity and negative expectancies (group × cue reactivity interactions) for pNN50, SDNN, HF HRV, and VLF HRV. LF HRV evinced the same trend but it was not statistically significant (p=.06). Fig. 1 illustrates that in the inpatient group, higher levels of cue reactivity were associated with higher levels of negative expectancies, whereas in the mandated student group, higher levels of negative expectancies were associated with relatively lower levels of these HRV reactivity indices. The group×subjective arousal interaction term showed a trend (p=.056) for higher levels of self-reported arousal associated with less negative expectancies in inpatients, but with more negative expectancies in mandated students.

Fig. 1.

The relationship between negative alcohol expectancies and (a) pNN50 (b=.39, t(62)=2.80, ΔR2=.10, p<.01; SD=10.6), (b) SDNN (b=.58, t(62)=3.27, ΔR2=.14, p<.01; SD=0.2), (c) HF HRV (b=.45, t(62)=2.38, ΔR2=.08, p<05; SD=0.7), and (d) VLF HRV (b=.41, t(62)=2.60, ΔR2=.09, p<05; SD=0.6) cue reactivity in the inpatient and mandated student samples. Each graph (x-axis) shows unstandardized HRV residual scores (i.e., HRV reactivity) in the range of three standard deviations above and below the group mean. Reactivity scores above zero on the x-axis (right side of zero) indicate increased HRV levels compared to baseline HRV levels, whereas reactivity scores below zero on the x-axis (left side of zero) indicate reduced HRV levels.

The relationship between cue reactivity and positive expectancies (all p>.05; not shown) did not differ between groups.

4. Discussion

The goal of the present study was to improve understanding of how instantaneous and persisting motivational precursors of drinking conjointly act in persons with different alcohol use and treatment histories. As expected, the inpatient group endorsed significantly more negative alcohol outcome expectancies than did the mandated student group, although the difference in positive expectancies was not significant. Extending previous findings (Ingjaldsson et al., 2003; Malpas, Whiteside, & Maling, 1991), inpatients showed significantly lower levels of HRV at baseline, indicating reduced neurocardiac signaling compared to the mandated students. Most notably, cross-over interactions were observed wherein pNN50, SDNN, HF HRV, and VLF HRV reactivity to alcohol cues were positively associated with greater negative expectancies in the inpatient group, but negatively associated with negative expectancies in the mandated student group. These physiological responses characterize reactivity to alcohol cues, because the unstandardized residual scores represent how much participants reacted to alcohol cues, above and beyond basal HRV levels.

Among inpatients, greater negative expectancies were associated with greater HRV reactivity to alcohol cues. This is consistent with enhanced attention capture by alcohol cues, greater cue salience, and/or greater visceral reactions (e.g., Garland, Franken, & Howard, 2011). Yet, in inpatients, higher negative expectancies tended to be associated with less subjectively-reported arousal to alcohol cues, possibly indicating the use of cognitive reappraisal to minimize dissonance created by their physiological activation to alcohol-related cues. Higher levels of physiological reactivity in the context of negative expectancies thus may serve to undermine conscious psychological attempts to disrupt alcohol-related, goal-directed behavior and promote the continued use of alcohol or drugs in the face of increasing negative experiences. In mandated college students, less HRV reactivity was associated with greater negative expectancies. Thus, in this group, negative expectancies appeared to have an opposite and more adaptive association (Appelhans & Luecken, 2006; Lyonfields, Borkovec, & Thayer, 1995) with regulation of physiological arousal.

Potential limitations of the study design should be considered. The inpatient and mandated student groups were different in terms of several demographic and drug use measures; however, these two groups are different by design, and the purpose of the study was not to identify whether the groups were different per se, but whether they were different in terms of the targeted association.

If replicated, these results suggest an important concurrent relationship between alcohol cue reactivity and negative expectancies in two groups of young adults with divergent AUD histories. In inpatients, these data support the examination of physiological retraining in which patients are taught to regulate HRV through simple procedures such as paced breathing (Song & Lehrer, 2003) or HRV biofeedback (Lehrer & Vaschillo, 2004). For college student drinkers, these findings suggest that increasing negative expectancies may yield benefits. Additionally, the present findings suggest the importance of more fully characterizing cue reactivity through multi-dimensional assessment that includes physiological markers such as HRV, which may provide unique information not captured by self-reported measures.

Highlights.

Momentary alcohol cue reactivity and cognitive expectancies motivate alcohol use.

We used heart rate variability (HRV) reactivity to examine their conjoint operation.

Young adults with and without alcohol use disorders (AUD) were tested.

AUD status moderated the relationship of HRV reactivity to negative expectancy.

Clinical implications of these divergent relations are considered.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources: Funding for this study was provided by NIAAA grants R01 AA015248, R01 AA015248-05S1, R01 AA019511, K02 AA00325, K01 AA017473 and contract HHSN275201000003C, as well as by NIDA grants P20 DA017552, 3P20 DA017552-05S1 and K12 DA031050. NIAAA and NIDA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors: Author A designed the present investigation, conducted literature searches and provided summaries of previous research. Authors A, B, C, and H wrote the paper. Authors A, B, C, and F conducted the statistical analysis. Authors D, E, and F conducted the experiments. Authors D, E, G and H designed the parent study. All authors provided comments and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

D. Eddie, Email: daveddie@eden.rutgers.edu.

J.F. Buckman, Email: jbuckman@rci.rutgers.edu.

E.Y. Mun, Email: eymun@rci.rutgers.edu.

B. Vaschillo, Email: bvaschil@rci.rutgers.edu.

E. Vaschillo, Email: evaschil@rci.rutgers.edu.

T. Udo, Email: tomoko.udo@yale.edu.

P. Lehrer, Email: lehrer@umdnj.edu.

References

- Appelhans BM, Luecken LJ. Heart rate variability as an index of regulated emotional responding. Review of General Psychology. 2006;10:229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bates ME, Buckman JF. Emotional dysregulation in the moment: Why some college students may not mature out of hazardous alcohol and drug use. In: White HR, Rabiner DL, editors. College Drinking and Drug Use. The Guilford Press; NewYork, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1994;25:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckman JF, White HR, Bates ME. Psychophysiological reactivity to emotional picture cues two years after college students were mandated for alcohol interventions. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:786–790. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney NL, Gillespie RA, Baker LH, Kaplan RF. Cognitive changes after alcohol cue exposure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:150–155. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Maesschalck R, Jouan-Rimbaud D, Massart DL. The mahalanobis distance. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 2000;50:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Drobes DJ, Carter AC, Goldman MS. Alcohol expectancies and reactivity to alcohol-related and affective cues. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:1–9. doi: 10.1037/a0014482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot AJ, Payen V, Brisswalter J, Cury F, Thayer JF. A subtle threat cue, heart rate variability, and cognitive performance. Psychophysiology. 2011;48:1340–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Schoenmakers T, Wiers RW. Cognitive processes in alcohol binges: A review and research agenda. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2008;1:263–279. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801030263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force. Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Stroot E, Kaplan D. Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Franken IHA, Howard MO. Cue-elicited heart rate variability and attentional bias predict alcohol relapse following treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2011;222:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2618-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Franken IH, Sheetz JJ, Howard MO. Alcohol attentional bias is associated with autonomic indices of stress-primed alcohol cue-reactivity in alcohol-dependent patients. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;20:225–235. doi: 10.1037/a0027199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Del Boca FK, Darkes J. Alcohol expectancy theory: The application of cognitive neuroscience. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. 1999;2:203–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ingjaldsson JT, Laberg JC, Thayer JF. Reduced heart rate variability in chronic alcohol abuse: Relationship with negative mood, chronic thought suppression, and compulsive drinking. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:1427–1436. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01926-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansma A, Breteler MHM, Schippers GM, De Jong CAJ, Van Der Staak CPF. No effect of negative mood on the alcohol cue reactivity on in-patient alcoholics. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:619–624. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BT, Corbin W, Fromme K. A review of expectancy theory and alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2001;96:57–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BT, McMahon J. Negative alcohol expectancy predicts post-treatment abstinence survivorship: The whether, when and why of relapse to a first drink. Addiction. 1994;89:1653–1665. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Engels R, Gmel G. Drinking motives as mediators of the link between alcohol expectancies and alcohol use among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:76–85. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer P, Vaschillo E. Heart rate variability biofeedback: A new tool for improving autonomic homeostasis and treating emotional and psychosomatic diseases. Japanese Journal of Biofeedback. 2004;30:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lyonfields JD, Borkovec TD, Thayer JF. Vagal tone in generalized anxiety disorder and the effects of aversive imagery and worrisome thinking. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26:457–466. [Google Scholar]

- Malpas SC, Whiteside EA, Maling TJ. Heart rate variability and cardiac autonomic function in men with chronic alcohol dependence. British Heart Journal. 1991;65:84–88. doi: 10.1136/hrt.65.2.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun EY, von Eye A, Bates ME, Vaschillo E. Finding groups using model-based cluster analysis: Heterogeneous emotional self-regulatory processes and heavy alcohol use risk. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:481–495. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey SE, Gogineni A, Nirenberg TD, Sparadeo F, Longabaugh R, Woolard R, et al. Alcohol expectancies as a mediator of the relationship between injury and readiness to change drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:185–191. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Long SW, Sher KJ, Gotham HJ, Baer JS, et al. The problem of college drinking: Insights from a developmental perspective. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:473–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, Christopher MS. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song HS, Lehrer PM. The effects of specific respiratory rates on heart rate and heart rate variability. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2003;28:13–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1022312815649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritzke WGK, Breiner MJ, Curtin JJ, Lang AR. Assessment of substance cue reactivity: Advances in reliability, specificity, and validity. Assessment. 2004;18:148–159. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Cheung EH, Brown GG, Frank LR, Paulus MP, Schweinsburg AD, et al. Neural response to alcohol stimuli in adolescents with alcohol use disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):727–735. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF, Hansen AL, Saus-Rose E, Johnsen BH. Heart rate variability, prefrontal neural function, and cognitive performance: The neurovisceral integration perspective on self-regulation, adaptation, and health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;37:141–153. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST. A cognitive model of drug urges and drug-use behavior: Role of automatic and nonautomatic processes. Psychological Review. 1990;97:147–168. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaschillo E, Bates ME, Vaschillo B, Lehrer P, Udo T, Mun EY, et al. Heart rate variability response to alcohol, placebo, and emotional picture cue challenges: Effects of 0.1-Hz stimulation. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:847–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]