Abstract

Several molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain trinucleotide repeat expansions. Here we show that in yeast srs2Δ cells, CTG repeats undergo both expansions and contractions, and they show increased chromosomal fragility. Deletion of RAD52 or RAD51 suppresses these phenotypes, suggesting that recombination triggers trinucleotide repeat instability in srs2Δ cells. In sgs1Δ cells, CTG repeats undergo contractions and increased fragility by a mechanism partially dependent on RAD52 and RAD51. Analysis of replication intermediates revealed abundant joint molecules at the CTG repeats during S phase. These molecules migrate similarly to reversed replication forks, and their presence is dependent on SRS2 and SGS1 but not RAD51. Our results suggest that Srs2 promotes fork reversal in repetitive sequences, preventing repeat instability and fragility. In the absence of Srs2 or Sgs1, DNA damage accumulates and is processed by homologous recombination, triggering repeat rearrangements.

Trinucleotide repeats are a particular class of microsatellites involved in many human neurological and muscular disorders, including fragile X syndrome, Huntington’s disease and Friedreich’s ataxia (reviewed in refs. 1,2). These disorders are all associated with the expansion of a trinucleotide repeat array near or within a gene. These expansions can be large, in some instances reaching several thousands of repeats in one single generation. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain trinucleotide repeat expansions, including replication slippage and DNA repair of single-strand nicks (reviewed in refs. 3,4). Several years ago, an alternative model was proposed, involving slippage during double-strand break repair5. It was shown that in yeast contractions and expansions occur during gene conversion associated with double-strand break repair. Rearrangements, which were observed in 20–40% of gene-conversion events, were dependent on the Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 protein complex, were more frequent during ectopic double-strand break repair and did not involve crossover formation6–8.

RAD27, the yeast homolog of the human FEN1 gene involved in Okazaki fragment processing, was the first gene identified whose deletion led to an increased frequency of large expansions and contractions of trinucleotide repeats in yeast5,9–11. During the course of a whole-genome screen looking for genes whose deletion gave a synthetic slow-growth or lethal phenotype with the RAD27 deletion, we found 41 mutants showing such a phenotype12. Among them, we identified two S-phase helicase genes, SRS2 and SGS1.

SGS1 was originally identified as a suppressor of a type I topoisomerase (TOP3) mutation13 and was also shown to interact with TOP2 (ref. 14). The Sgs1 protein is a DEAH-box helicase, having orthologs in Escherichia coli (RecQ), in all sequenced yeasts15 and in mammals. Five orthologs are found in humans: WRN, BLM and RTS, respectively involved in Werner’s, Bloom’s and Rothmund-Thomson’s syndromes, and two shorter forms, RecQL and RecQ5. The precise biochemical activity of SGS1 is unknown, but the BLM protein and human topoisomerase IIIα can unwind double-Holliday junctions in vitro16. In addition, sgs1 mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae show increased levels of crossovers17,18, and Drosophila melanogaster mus309 mutants (mutated in the BLM ortholog) are defective in a late stage of double-strand break repair19. Altogether, these data point to a role for SGS1 in unwinding Holliday junction–like molecules.

SRS2 is involved in the post-replication repair pathway of DNA damage20. The purified Srs2 protein possesses a 3′-to-5′, ATP-dependent helicase activity21 and was shown to disrupt Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments in vitro22,23. It was recently proposed that the Srs2 helicase could act as an antirecombinogenic protein that unwinds toxic recombination intermediates24. One study25 showed that short CAG•CTG trinucleotide repeats (13–25 repeats) were more prone to expansions in a srs2 mutant, and that these expansions were largely independent of RAD51. However, long trinucleotide repeat sequences in both yeast and E. coli undergo breakage in a length-dependent manner9,26–29. Therefore, we were interested in testing the effect of deleting the SRS2 and SGS1 genes on the stability of long CAG•CTG repeats and determining whether expansions of such long repeats occurred independently of RAD51.

SRS2 and SGS1 mutants show a strong genetic interaction—the srs2Δ sgs1Δ double mutant is lethal30. Cell death is suppressed by mutations in RAD51, RAD55 or RAD57, showing that homologous recombination is responsible for cell death. The authors suggested that the Srs2 and Sgs1 helicases are needed either to help restart stalled replication forks or at the replication termination step, or alternatively to process recombination intermediates that form during replication. Their simultaneous absence would lead to accumulation of DNA damage transformed into potentially toxic recombination intermediates, whose resolution would be lethal for the cells31.

To study the role of SRS2 and SGS1 on the stability of long trinucleotide repeats during replication, we integrated CAG•CTG repeats in the two opposite orientations in two different chromosomal locations: on yeast chromosome X and on a yeast artificial chromosome (YAC). We found that these repeats are unstable in both mutant backgrounds. Instability is dependent on RAD52 and RAD51, but to different degrees. Chromosomal fragility is also increased in both mutants; however, further analyses showed that only in srs2Δ cells is this fragility dependent on homologous recombination, suggesting that chromosomal breakage occurs by a different pathway in sgs1Δ cells. Analysis of replication and recombination intermediates by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis showed that molecules that migrate in a similar manner to reversed forks form during replication of the trinucleotide repeat tract, and formation of these intermediates depends on the presence of both SRS2 and SGS1. We propose that trinucleotide repeat replication is less efficient in srs2Δ and sgs1Δ cells, leading to accumulation of DNA damage. Processing of this damage by the homologous recombination machinery triggers rearrangements of the repeat tract by sister-chromatid recombination and single-strand annealing.

RESULTS

CAG•CTG repeats are more fragile in the absence of Srs2 or Sgs1

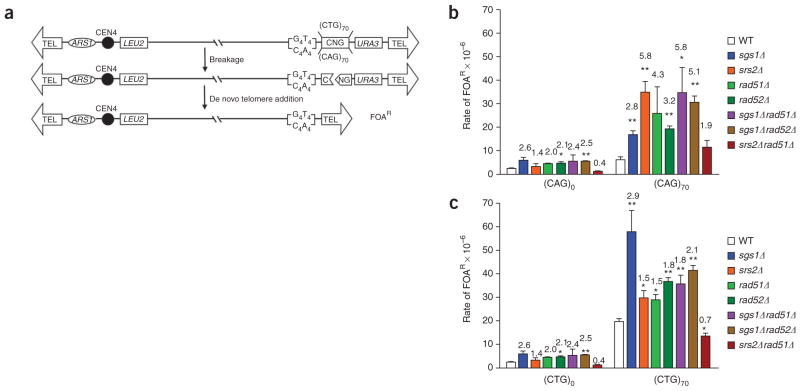

To study whether Srs2 and Sgs1 proteins protect against fragility caused by trinucleotide repeats, we used a YAC-based assay that allowed determination of the rate of CAG•CTG fragility in either wild-type or helicase-deficient yeast (Fig. 1a). Comparison of the 5-fluorotic acid resistance (FOAR) rates in strains carrying a (CAG)70 tract showed that breakage increased 2.8-fold and 5.8-fold in the absence of Sgs1 and Srs2, respectively, as compared to the rate in the wild-type strain (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1 online; P <0.01 for both). The increase in breakage rate in the absence of either helicase suggests that they both have an important role in preventing or repairing lesions that occur at long trinucleotide repeats. Srs2 seems to have a particularly important function at a CAG repeat tract, as fragility in the srs2Δ background was increased only 1.4-fold for the (CAG)0 control YAC but 5.8-fold for the (CAG)70 YAC. Notably, deletion of RAD51 in an srs2Δ background brought the breakage rate down almost to the wild-type level (wild type versus srs2Δ rad51Δ, P = 0.163; srs2Δ versus srs2Δ rad51Δ, P = 0.02), indicating that the increased fragility observed in a srs2Δ strain is dependent on RAD51. In contrast, deletion of RAD51 in an sgs1Δ background did not suppress fragility and in fact resulted in increased CAG fragility compared to the sgs1Δ single mutant (P = 0.07). Because there are some pathways of recombination that are dependent on Rad52 but not Rad51, we also made the sgs1Δ rad52Δ double mutant. This mutant showed a rate of FOAR similar to that of the sgs1Δ rad51Δ mutant. The increase observed in the double mutant is consistent with an additive effect of the sgs1Δ and rad52Δ single mutants (Fig. 1b). Thus, the fragility that occurs in the absence of Sgs1 is independent of recombination.

Figure 1.

CAG•CTG repeats show increased fragility in the absence of Srs2 or Sgs1 helicases. Molecular analysis of YACs purified from FOAR colonies, in both wild-type and mutant strains, showed that the rate of FOAR is correlated with YAC breakage (data not shown; see also ref. 26). (a) Experimental system. If the YAC undergoes breakage at or near the trinucleotide repeat tract, the distal DNA fragment containing the URA3 gene is lost and cells become resistant to 5-fluoroorotic acid (FOAR). Broken YACs can be recovered by addition of a new telomere onto the 108-bp T4G4/C4A4 telomere seed sequence (TEL). (b,c) Rate of FOAR for cells with YACs containing no repeat (CAG•CTG)0, a (CAG)70 repeat (b) or a (CTG)70 repeat (c). The average of at least three experiments is shown. Error bars indicate s.e.m., and asterisks indicate a significant difference between the wild type and the mutants (pooled t-test: **, P ≤ 0.01; *, P ≤ 0.05). Numbers above each bar represent the fold increase over the wild-type value for the corresponding repeat tract.

To determine whether there is an orientation effect on CAG•CTG fragility, we flipped the repeat tract so that the (CTG)70 repeat would be on the lagging-strand template (CTG orientation). This orientation has been previously shown to be more contraction prone in both yeast and E. coli cells32–36. In this orientation, the repeat was even more prone to breakage, with the rate of FOAR being 3.3-fold more than in the CAG orientation (nine-fold more than in the control; Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1). Both Sgs1 and Srs2 were still important in preventing repeat tract breakage in this orientation, although notably the importance of each helicase was reversed. In the sgs1Δ mutant, fragility was about three-fold higher than the wild-type rate, whereas, in the srs2Δ strain, fragility was increased only 1.5-fold. As in the CAG orientation, fragility rates returned to wild-type levels in the srs2Δ rad51Δ double mutant, whereas fragility in the sgs1Δ strain was only partially dependent on RAD51. In summary, both Srs2 and Sgs1 helicases are important in preventing fragility of a CAG•CTG tract, regardless of orientation, and fragility of an srs2Δ mutant, but not an sgs1Δ mutant, is rescued by preventing Rad51-dependent recombination.

CAG•CTG repeats are frequently rearranged in srs2Δ and sgs1Δ cells

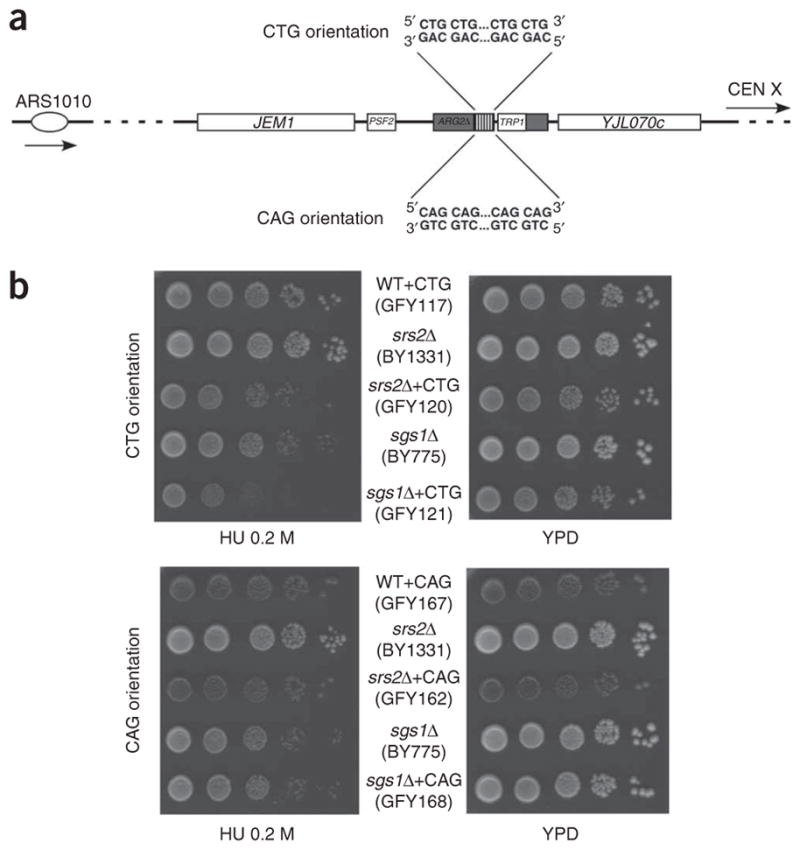

To determine the role of Srs2 and Sgs1 on trinucleotide repeat stability, we integrated CAG•CTG repeats in the two opposite orientations at either the ARG2 locus on yeast chromosome X or on the YAC. For both locations, Figures 1a and 2a show the replication fork coming from the left, so that when the CTG strand is the top strand it is used as the template for lagging-strand synthesis; this strand will be hereafter referred to as the CTG orientation, or CTG repeats (orientation II32). When the CTG strand is the bottom strand, it is used as the template for leading-strand synthesis and will be hereafter referred to as the CAG orientation, or CAG repeats (orientation I32).

Figure 2.

Effect of the trinucleotide repeat tract orientation on stability. (a) Experimental design. The ARG2 locus on chromosome X, at which repeats are cloned, is depicted, along with the replication origin (ARS1010) and centromere location (CEN X). Strains used in this study contain the same repeat tract cloned either in the CTG orientation (the CTG sequence is the lagging-strand template) or in the CAG orientation (the CAG sequence is the lagging-strand template). (b) Orientation effect on growth rate on hydroxyurea (HU) plates compared to standard glucose plates (YPD). WT, wild type.

First, we analyzed repeat-size changes in srs2Δ and sgs1Δ strains in the CTG orientation and compared them to the wild-type strain. At the ARG2 locus, we observed no expansion of the (CTG)55 repeat in the wild-type and sgs1Δ strains. In contrast, in the srs2Δ strain, we detected expansions in 8.1% of the colonies analyzed, a substantially higher frequency than observed in the wild-type strain (Table 1). Thus, deletion of SRS2 substantially increases expansions of a long CTG tract, whereas deletion of SGS1 does not increase expansions. For contractions, we observed a 25-fold increase in the srs2Δ strain (58.1%) and a 20-fold increase in the sgs1Δ strain (47.1%) as compared to in the wild type (Table 1). Expansion sizes ranged from 17 to 33 repeats (mean: 22 ± 4 repeats), and contraction sizes ranged from 10 to 55 repeats (mean: 29 ± 3 repeats) (size changes smaller than 10 repeats were not detectable at this locus). On the YAC, the (CTG)70 repeat seemed to be more contraction prone than the shorter repeat at the ARG2 locus, with 24.5% of cells showing contractions and none showing expansions in the wild-type background (Table 2). Nonetheless, similarly to the ARG2 locus, an srs2Δ mutation substantially increased the frequency of expansions to 3.1%. The expansion sizes ranged from 26 to 39 repeats (mean: 29 ± 6 repeats) and the contraction sizes ranged from 4 to 70 repeats (mean: 49 ± 2 repeats) (size changes ≥3 repeats were detectable at the YAC locus).

Table 1.

Instability of CTG and CAG triplets on chromosome X in srs2Δ and sgs1Δ mutants

| Strain | No. of clones | Contractions (%)a | Expansions (%)a | Total (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTG orientation | ||||

| WT | 141 | 2.1 (3) | 0 (0) | 2.1 (3) |

| srs2Δ | 62 | 58.1 (36)** | 8.1 (5)** | 66.2 (41) |

| sgs1Δ | 104 | 47.1 (49)** | 0 (0) | 47.1 (49) |

| rad52Δ | 115 | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (1) |

| rad51Δ | 92 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| srs2Δ rad52Δ | 117 | 3.4 (4) | 0 (0) | 3.4 (4) |

| srs2Δ rad51Δ | 114 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| sgs1Δ rad52Δ | 93 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| sgs1Δ rad51Δ | 122 | 0.8 (1) | 5.7 (7)** | 6.6 (8) |

| CAG orientation | ||||

| srs2Δ | 182 | 2.2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2.2 (4) |

| sgs1Δ | 192 | 2.1 (4) | 0 (0) | 2.1 (4) |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of clones in each class.

P-value ≤ 0.05;

P-value ≤ 0.01 (Fisher’s exact test).

Table 2.

Instability of CTG and CAG triplets on the YAC in srs2Δ and sgs1Δ mutants

| Strain | No. of clones | % Contractionsa | % Expansionsa | % Totala |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTG orientation | ||||

| WT | 163 | 24.5 (40) | 0 (0) | 24.5 (40) |

| srs2Δ | 130 | 30.0 (39) | 3.1 (4)* | 33.1 (43) |

| sgs1Δ | 157 | 23.6 (37) | 0 (0) | 23.6 (37) |

| srs2Δ rad51Δ | 134 | 34.3 (46) | 0.8 (1) | 35.1 (47) |

| sgs1Δ rad51Δ | 164 | 32.9 (54) | 0.6 (1) | 33.5 (55) |

| sgs1Δ rad52Δ | 80 | 35 (28) | 0 (0) | 35 (28) |

| CAG orientation | ||||

| WT | 217 | 2.8 (6) | 1.4 (3) | 4.1 (9) |

| srs2Δ | 231 | 6.5 (15)* | 5.6 (13)** | 12.1 (28) |

| sgs1Δ | 236 | 8.9 (21)** | 1.7 (4) | 10.6 (25) |

| srs2Δ rad51Δ | 144 | 3.5 (5) | 0.7 (1) | 4.2 (6) |

| sgs1Δ rad51Δ | 144 | 6.9 (10) | 0 (0) | 6.9 (10) |

| sgs1Δ rad52Δ | 164 | 11.6 (19)** | 0.6 (1) | 12.2 (20) |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of clones in each class.

P-value ≤ 0.05;

P-value ≤ 0.01 (Fisher’s exact test).

We subsequently looked for instability in both mutant backgrounds in the opposite orientation, where the CAG repeats lie on the lagging-strand template, expecting that the contractions would be less frequent. Indeed, at the ARG2 locus, the (CAG)55 repeats were stable (around 2% of cells showed contractions and none showed expansion in both mutants; Table 1). On the YAC, however, where the repeats seem to be more unstable owing to either the slightly longer repeat tested or the location, or a combination of both, we observed that repeats were destabilized in both mutant backgrounds (Table 2). In the srs2Δ mutant both expansions and contractions were more frequent, whereas in the sgs1Δ strain only contractions showed substantially increased frequencies (Table 2). Expansion sizes ranged from 3 to 30 repeats in the srs2Δ strain (mean: 17 ± 4 repeats) and 3 to 16 repeats in the sgs1Δ strain (mean: 9 ± 7 repeats); contraction sizes ranged from 3 to 69 repeats (srs2Δ mean: 17 ± 5 repeats; sgs1Δ mean: 38 ± 5 repeats). We conclude that trinucleotide repeats are prone to frequent rearrangements in srs2Δ and sgs1Δ cells. However, the two helicases do not act equivalently, as Srs2 protects against both repeat expansions and contractions, whereas only contractions showed increased frequency in the absence of Sgs1.

To detect a possible effect of the orientation on cell growth in both mutant backgrounds, we made serial dilutions on plates containing 200 mM hydroxyurea. Hydroxyurea slows down replication fork progression37 by inhibiting ribonucleotide reductase38. Reduced growth on hydroxyurea plates was visible in srs2Δ cells containing CTG repeats at ARG2, as compared to an isogenic strain containing no repeat (Fig. 2b). Similarly, although sgs1Δ cells were sensitive to hydroxyurea, this phenotype was more severe in sgs1Δ cells containing repeats in the CTG orientation. In the CAG orientation, no growth defect due to the presence of the repeats was detected. This suggests that both helicases are needed to help replicating CTG repeats, perhaps by unwinding structures formed by these repeats39 that could lead to lesions such as double- or single-strand breaks, or yet other kinds of lesions. The high level of instability detected in srs2Δ and sgs1Δ mutants in the CTG orientation, as compared to the lower level for the CAG orientation (Table 1), would reflect this difference.

Repeat instability in both mutants depends on recombination

To determine whether trinucleotide repeat instability in the CTG orientation was dependent on homologous recombination, we deleted RAD51 or RAD52 in srs2Δ and sgs1Δ mutants and in the wild-type strain. At the ARG2 locus, trinucleotide repeats were stable in the rad52Δ and rad51Δ single mutants (Table 1). In sgs1Δ rad52Δ, srs2Δ rad52Δ and srs2Δ rad51Δ double mutants, trinucleotide repeats were as stable as in the wild-type strain. Thus, the high level of instability observed in both mutants is mediated by homologous recombination (Table 1). The (CTG)70 repeats on the YACs showed a similar profile, where the increased frequency of expansions observed in srs2Δ cells dropped down to a frequency indistinguishable from that of the wild-type level in srs2Δ rad51Δ cells (Table 2, P = 0.4512), indicating that the expansion events that occurred in srs2Δ cells were dependent on Rad51-mediated recombination.

The results were more complex for the sgs1Δ mutant. The increased contractions observed, at the ARG2 locus, in sgs1Δ cells were suppressed by a deletion of RAD52 or RAD51, indicating that these contractions were triggered by homologous recombination (Table 1). However, in the sgs1Δ rad51Δ double mutant, the frequency of expansions was substantially higher than in the wild-type strain or either of the single mutants. Although it is possible to generate expansions by single-strand annealing (SSA) when both SGS1 and RAD51 are inactivated, previous studies showed that mostly contractions were generated by such a mechanism5. Further investigations will be needed to clarify the precise mechanism by which expansions occur in this strain background. We also deleted RAD51 or RAD52 in the sgs1Δ mutant, on the YAC. The CAG contractions observed in the sgs1Δ strain were not markedly reduced by the elimination of Rad51 or Rad52 (Table 2). We conclude that repeat instability induced by deletion of SGS1 seems to be only partially dependent on homologous recombination, an observation reminiscent of the CTG repeat fragility we observed in sgs1Δ cells, which was also only partially dependent on homologous recombination (Fig. 1c).

Altogether, we found that all phenotypes (repeat expansions and contractions and chromosomal fragility) that showed increased frequency in srs2Δ strains were dependent on the presence of a functional homologous recombination machinery. However, the repeat instability and fragility occurring in the sgs1Δ strain were only partially dependent on recombination, with the results dependent on the type of instability and on the orientation of the repeat.

Analysis of replication and recombination intermediates by two-dimensional gels

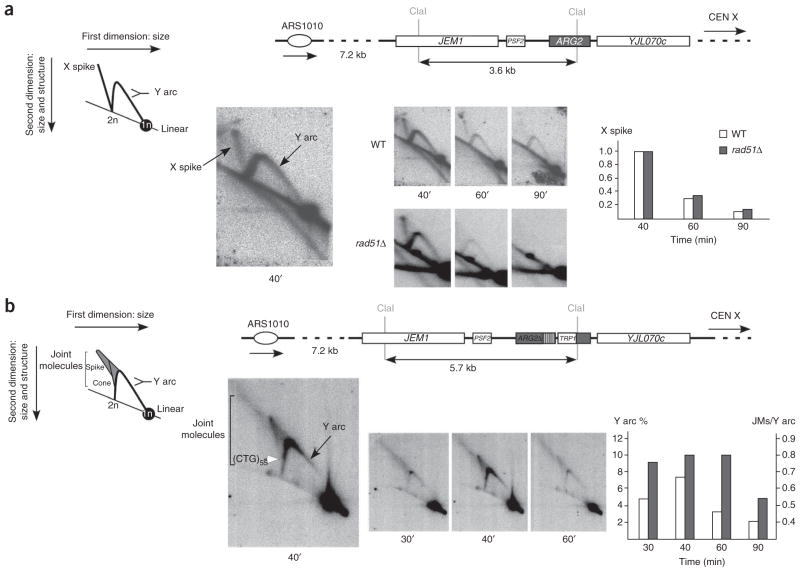

To investigate replication and recombination intermediates during trinucleotide repeat replication, we used two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. In the wild-type strain containing no repeat tract, we observed a Y arc corresponding to replication forks progressing through the ARG2 locus (Fig. 3a). In addition, we detected X-shaped molecules that migrate in a similar manner to Holliday junctions or hemicatenanes and appear and disappear with the Y arc. To determine whether these structures were recombination intermediates, we performed the same experiment in a rad51Δ strain. In this strain, the X spike was still detectable, showing that these molecules are not RAD51-dependent recombination intermediates and suggesting that they are hemicatenanes40 (although we cannot formally exclude that they are some kind of RAD51-independent recombination intermediate).

Figure 3.

Analysis of replication intermediates at the ARG2 locus by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. (a) The ARG2 locus in strains without repeats is depicted, showing the positions of the two ClaI sites used to digest total DNA. The X spike signal values are shown as the ratio of the signal at each time point over the signal at 40 min. An enlargment of the 40-min time point is shown to the left, along with a cartoon depicting the types of molecules visualized on the gel. (b) The ARG2 locus in the wild-type strain GFY117 containing the (CTG)55 repeat tract is depicted. The same enzymatic restriction, probe and quantification as above were used. The Y arc (white bars) and the joint molecule (gray bars) signal values are shown as the percentage of Y arc signal over total signal, and as the ratio of joint molecule (JM) signal over Y arc signal, respectively. An enlargment of the 40-min time point is shown to the left, along with a cartoon depicting the different types of molecules visualized on the gel, the spike and the cone being the joint molecules. The position at which the CTG repeats are inserted is shown by a white arrowhead.

Hemicatenanes were not visible in the wild-type strain containing the trinucleotide repeat tract; instead, they were replaced by two other kinds of structured molecules: a spike-like shape migrating above the Y arc and a conical shape emanating from where the trinucleotide repeat tract is located, on the descending Y arc (Fig. 3b). These structured molecules also appear and disappear with the Y arc, indicating that they are formed during replication of the ARG2 locus and are removed afterwards. These structures migrate in a similar manner to joint molecules, which would be slightly retarded in the second dimension.

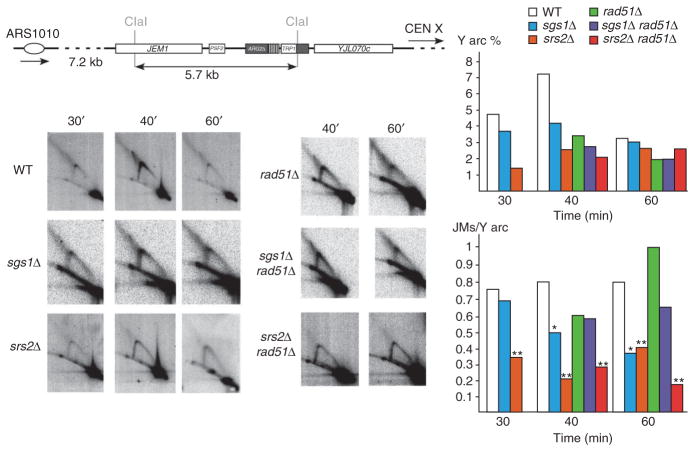

In the sgs1Δ and srs2Δ strains, progression of the replication fork is similar to the wild type, with the Y arc peaking in intensity at around 40 min (Fig. 4). Joint molecules were visible in both the srs2Δ and sgs1Δ mutants, but their amount was reduced as compared to wild type. In the srs2Δ strain, the amount of joint molecules was significantly reduced two- to four-fold as compared to wild type at all time points (P = 0.0087). In the sgs1Δ strain, the amount of joint molecules as compared to Y arc is significantly reduced two-fold at 40 min and 60 min (P = 0.0465). Formation of these joint molecules is therefore partially dependent on both SRS2 and SGS1.

Figure 4.

Analysis of replication intermediates at ARG2 by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis in wild-type (WT) and mutant strains. The ARG2 locus in the wild-type strain GFY117 containing the (CTG)55 repeat tract is depicted as in Figure 3. Representative two-dimensional gels for each time point are shown to the left. Y arc and joint molecules quantifications were performed as in Figure 3. Asterisks above graph bars indicate a significant difference between the wild type and the mutants (Mann-Whitney test: **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05).

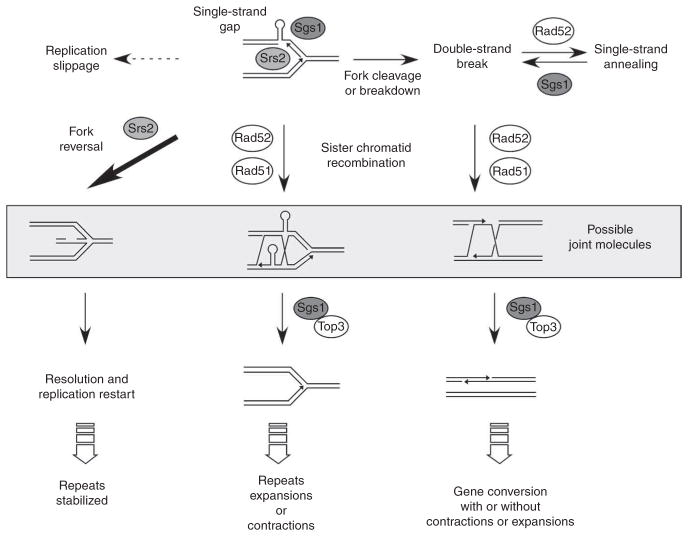

To determine whether joint molecule formation was dependent on homologous recombination, we analyzed their amounts in a rad51Δ strain and in the sgs1Δ rad51Δ and srs2Δ rad51Δ double mutants, focusing on the 40-min and 60-min time points (Fig. 4). In the rad51Δ strain and in sgs1Δ rad51Δ cells, joint molecule formation was not statistically different from what was observed in the wild type (P > 0.05). However, in the srs2Δ rad51Δ strain, the amount of joint molecules was significantly decreased three- to five-fold compared to the rad51Δ mutant (P = 0.0418) and three- to four-fold compared to the wild type (P = 0.0475), but was not statistically different from the amount in the srs2Δ single mutant (P > 0.05). This shows that SRS2 is epistatic to RAD51 for joint molecule formation, and that RAD51 is epistatic to SGS1 for the same process. Joint molecules could be reversed replication forks; therefore, SRS2 would act first at the replication fork, perhaps to promote replication fork reversal when damage is present. The bacterial Srs2 homolog, UvrD, has been shown to facilitate the reversal of stalled forks by clearing inappropriate binding of recombination proteins such as the Rad51 homolog, RecA41. If fork reversal does not occur properly, the damaged fork will be taken care of by Rad51-mediated homologous recombination, to be eventually resolved by Sgs1. We therefore propose that joint molecules are a mixture of reversed replication forks and Holliday junctions (Fig. 5, and see Discussion).

Figure 5.

A model showing different pathways to repair replication fork damage due to structure-forming sequences. Srs2 and Sgs1 helicases act at the fork to facilitate replication across structure-forming sequences on the CTG strand (above). Srs2 can facilitate fork reversal, perhaps by removing Rad51 from damaged forks, to allow the damage to be bypassed and the fork to restart in a manner that prevents breakage and repeat-length changes (left arrow). Sgs1 may also help to stabilize a replisome stalled at the CAG•CTG repeats. In the absence of either of these helicases, single-strand gaps or double-strand breaks result (above). Single- or double-strand breaks can be processed by a Rad51-dependent sister chromatid recombination pathway, leading to recombination intermediates that are dissolved by Sgs1–Top3 (middle). Slippage associated with DNA synthesis of CAG•CTG repeats can lead to repeat contractions or expansions7. Double-strand breaks may be repaired by homologous recombination, leading to trinucleotide repeat instability (right downward arrow), by Rad51-independent single-strand annealing (right, above), or, if unrepaired, will result in loss of a chromosome arm as observed in our fragility assay. Joint molecules observed by two-dimensional gels (shown inside the gray box) correspond mainly to reversed forks but may also represent some Rad51-dependent sister chromatid recombination intermediates (see text for details). Alternatively, damage may be processed by a template-switching mechanism, as proposed previously60, leading to similar recombination intermediates. In the absence of both Sgs1 and Rad51 proteins, instability occurs by another pathway, in which replication slippage following formation of unresolved secondary structures on the lagging strand or on its template leads to contractions or expansions (dotted arrow, above left).

DISCUSSION

SRS2 and SGS1 both stabilize long CAG•CTG repeats

Previous studies25 using (CAG•CTG)13 or (CAG•CTG)25 repeats showed that repeat expansions in srs2Δ cells were mostly independent of RAD51. Therefore, the authors proposed that a nonrecombinational pathway, for example, slippage of the 3′ end of a nascent strand combined with hairpin formation, generates expansions in srs2Δ cells42. In the present work, we show that size changes in srs2Δ cells occur mainly by homologous recombination. We therefore propose that when repeat size reaches a given threshold (between 25 and 55 triplets), expansions in srs2Δ cells occur mainly by homologous recombination between sister chromatids (because strains are haploid).

In the same work25, SGS1 was shown to have no effect on (CAG•CTG)25 trinucleotide repeats, whereas, in the present study, the frequency of contractions was substantially increased in sgs1Δ strains. Therefore, there seems to be a size threshold above which SGS1 is important to maintain trinucleotide repeat stability. This idea is strengthened by an experiment using (CTG)40 repeats, for which no contractions were observed out of 92 colonies analyzed in the sgs1Δ mutant (data not shown), suggesting that 40 repeats is under the threshold requiring a functional SGS1 gene. Some contractions in the sgs1Δ mutant may be generated by SSA, as this is an efficient pathway to generate contractions between two (CAG•CTG) repeats5. Sgs1 is also involved in rejection of mismatched SSA, suggesting a role for Sgs1 in unwinding SSA intermediates43,44 and preventing SSA events that would lead to contractions (Fig. 5, above right).

We note that, although the results from both experimental systems (YAC and chromosome) are in good agreement, the level of instability is higher on the YAC than on the chromosome. However, it is well known that cis-acting effects such as chromosomal location and repeat length have major roles in regulating trinucleotide repeat stability (reviewed in refs. 3,45). Our results suggest that either YAC repeats are more unstable because they are slightly longer (70 triplets against 55 on the chromosome) or because they are located in a chromosomal environment that favors instability.

Notably, Srs2 had a stronger, more specific role in preventing fragility in the CAG orientation. In this orientation, CTG hairpins will occur on the nascent lagging strand, suggesting that Srs2 has an important role in preventing inappropriate recombination on this strand, which could lead to expansions and fork breakdown. In contrast, Sgs1 was more important in preventing fragility in the CTG orientation, suggesting that it may have a role in unwinding hairpins that form on the lagging-strand template. WRN, the human homolog of Sgs1, is known to interact with Polymerase δ and facilitate replication through CGG hairpin structures46,47, and Sgs1 helicase has the correct polarity to track along the lagging-strand template in the 3′-to-5′ direction during lagging-strand replication to unwind CTG hairpins. Persistence of the template hairpin could lead to fork stalling and breakdown, explaining the fragility observed in sgs1Δ mutants, or the template hairpin could be bypassed, leading to contractions.

Possible stabilization of trinucleotide repeats by reversed forks

We initially postulated that hairpins formed by trinucleotide repeats could impede replication, therefore creating more opportunities to stall the fork or to promote the formation of single-stranded gaps on repeat-containing DNA. This hypothesis is supported by the slower growth rate of cells carrying CTG repeats in the presence of hydroxyurea (Fig. 2). Previous studies showed a weak, diffuse pausing signal on two-dimensional gels for plasmid-borne (CTG)80 repeats in yeast, as compared to the strong pausing signal observed for (CGG)40 or (CCG)40 repeats48. In bacteria, the pausing signal at (CTG)70 repeats can be clearly detected only when protein synthesis is blocked by chloramphenicol49. In our experiments, we did not observe any strong pause of the replication fork near or within a chromosome-borne (CTG)55 trinucleotide repeat tract in the wild type or any of the mutant strains studied, although we cannot exclude that a weak and/or transient pause exists. If this transient pause is rapidly converted into joint molecules, this would preclude its detection as a spot on the Y arc.

The joint molecules detected migrated in a similar manner to reversed forks seen in rad53 yeast mutants50 or hemicatenanes detected during replication near ARS305 in yeast40. Joint molecules were barely detectable in the srs2Δ mutant and in the srs2Δ rad51Δ double mutant (Fig. 4), indicating that Srs2 is involved in their formation or processing. In addition, joint molecules were still visible in the rad51Δ mutant. Therefore, it is unlikely that they represent classical recombination intermediates. We propose that the joint molecules observed are mostly molecules resulting from replication fork reversal (Fig. 5). In support of this hypothesis, it was very recently shown that reversed replication forks appear during replication from a bacteriophage T4 chromosomal origin: in the presence of the gp46 nuclease, there is a transient accumulation of intermediates, forming a conical shape rather than a discrete spike, similarly to what we have observed in the presence of trinucleotide repeats (Fig. 3b). This conical shape contains reversed replication forks whose double-stranded ends have been partially resected by the gp46 nuclease51.

A recent study52 supports the hypothesis that replication fork reversal occurs frequently during replication of trinucleotide repeats in a synthetic replication fork model. We must point out that replication fork reversal can occur in linear DNA but is restrained in topologically closed DNA53,54. Therefore, in vivo, one must speculate that single- or double-strand breaks occur to release topological constraints and allow fork reversal.

In the sgs1Δ mutant, we observed a significant decrease in the amount of joint molecules, with this decrease being partially dependent on the presence of RAD51 (Fig. 4). This is different from what was observed in a previous study in budding yeast, in which X-shaped intermediates accumulated in sgs1Δ cells55. Therefore, it is unlikely that the two kinds of molecules are similar. Sgs1 is therefore likely to be involved in stabilizing CTG repeat–containing replication forks, allowing possible subsequent formation of reversed forks. Consistent with the observation that Sgs1 contributes to replisome stability56, in its absence CTG repeat–containing forks would break, leading to a reduction in the formation of reversed forks, and hence of joint molecules, and to a corresponding increase in repeat fragility.

Various mechanisms have been proposed to lead to trinucleotide repeat expansions, all of which are based on the basic idea that trinucleotide repeats form stable hairpins during different DNA metabolic processes2–4,45. We propose that unrestricted recombination that occurs subsequent to replication through these structure-forming sequences is another factor contributing to the expansion of long CAG•CTG repeats.

METHODS

Strains

Strains used in this study are haploid and isogenic to the S288c strain except for the mutations indicated (Supplementary Table 2 online). Strains containing trinucleotide repeats in the CTG orientation were derivatives of the GFY117 strain6. Strains containing trinucleotide repeats in the CAG orientation were built by transforming linearized plasmid pTRI131 into wild-type, srs2Δ or sgs1Δ cells. We built the plasmid pTRI131 by flipping the trinucleotide repeat tract in pTRI110 (ref. 6). Deletions were done by PCR-mediated gene replacement. SRS2 and SGS1deletions were made in the GFY117 strain by transformation of PCR fragments containing the HIS3 selection marker and short flanking homologies, to give rise to GFY120 and GFY121 strains. We generated RAD51 and RAD52 deletions by transformation of the KANMX marker flanked by short homologies, in strains GFY117, GFY120 or GFY121. For the fragility experiments on the YAC, SRS2, SGS1 and RAD51 single mutants in the BY4742 strain were obtained from the yeast MATα deletion set. The double mutants derived from BY4742 were generated by transformation of HISMX6 marker flanked by short (40-bp) homologies. To create YAC-containing strains, we introduced YACs with or without CAG•CTG repeats into the various strains via mating with a kar1-1 strain. Subsequently to the introduction of the YAC, repeat length and the genotype of the strain containing the YAC were confirmed by both genetics and PCR analysis. Transformants were screened and CAG•CTG tract length was verified by PCR and by Southern blot. We created the strains with a YAC carrying the repeats in the CTG orientation by the following method. Wild-type yeast strains that carried the YAC with no repeats were plated on a 5-fluoroorotic acid (FOA)-containing plate to select for cells that had undergone a YAC breakage event. Colonies that grew on the FOA plate were analyzed by Southern blot to confirm the breakage and subsequent healing at the G4T4/C4A4 sequence. Cells with the correct YAC structure were then transformed with a linearized pVS20 plasmid that had the repeats in the CTG orientation and selected for the ability to grow on plates lacking uracil. Transformants were checked by Southern and PCR analysis for the presence of the repeats in the correct orientation.

Molecular analysis of CTG and CAG trinucleotide repeat size at ARG2

For each experiment, a single colony was diluted in water, plated on a YPD plate and incubated at 30 °C for 2 d. From this plate, 12 single colonies were picked and inoculated in 1.8-ml cultures in sterile microplates (ABGene AB-0932) and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. DNA was extracted directly in microplates, following the standard Zymolyase procedure for yeast cells. All DNA transfers during the preparation process were made by a Hydra-96 syringes automatic microdispenser (Robbins Scientific). After DNA extractions, PCRs were performed in microplates (Sorenson) in an Eppendorf Mastercycler to amplify the repeat tract and its flanking regions. PCR products were migrated on 1.2% agarose gels without ethidium bromide and stained after the migration. Alternatively to PCR, total genomic DNA was digested and trinucleotide repeat sizes were analyzed by Southern blot. Whenever the 12 colonies coming from the same plate showed the same contraction or expansion, we assumed that the rearrangement occurred in the mother colony, before plating, and these clones were not taken into account in our analysis.

Molecular analysis of CTG and CAG repeat size and fragility on the YAC

Cells were plated for single colonies on supplemented minimal medium lacking uracil and leucine (YC –Leu –Ura) to maintain selection for the YAC and grown at 30 °C. At least two separate cytoductants (from kar1-1 matings) were tested for each strain. The rate of FOA resistance was calculated by the maximum-likelihood method using SALVADOR software. The healing of the YAC at the G4T4/C4A4 tract was confirmed for a subset of FOAR colonies by Southern blotting (data not shown). For determining the stability of CTG or CAG repeats on the YAC, the repeat tract was PCR amplified from colonies that grew on the YC –Leu plates used in the fragility assay to determine total cell count using CTGrev2 (5′-CCCAGGCCTCCAGTTTGC-3′) and T7 (5′-TAA TACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) primers and an IDPOL polymerase (ID labs). Products were separated on 2% Metaphor gels and the CAG tract size was estimated by using the TotalLab software (Nonlinear Dynamics).

Orientation effect of CAG•CTG repeats on growth on hydroxyurea

Ten-fold serial dilutions of yeast strains were spotted on plates containing 0.2 M hydroxyurea or on standard glucose plates and allowed to grow for 3 d or 2 d, respectively, at 30 °C.

Two-dimensional gel analyses

The closest replication origin to the ARG2 locus is ARS1010, a well-characterized late replication origin, that fires approximately 30 min after the beginning of S phase57,58 and is located 7.2 kb 5′ to the ARG2 gene (Fig. 3). Cells were grown overnight at 30 °C, in 200-ml YPD cultures. When concentration reached 107 cells per ml, cells were centrifuged, washed, resuspended in fresh YPD medium at a concentration of 0.75 × 107 cells per ml and grown for another 45 min at 23 °C to slow replication. Afterwards, 2 × 109 cells were synchronized using 3μg ml–1 α-factor for 2 h at 23 °C (or 2.5 h for rad51Δ cells). G1 arrest was checked by microscope observation. When more than 90% of the cells were arrested, they were centrifuged, washed and resuspended in 200 ml fresh YPD medium at 23 °C. Progression of replication was followed by microscope observation and confirmed by fluorescence-activated cells sorting (FACS) analysis. Cells were harvested after 30 min, 40 min, 60 min and 90 min and killed by addition of sodium azide (0.1% final concentration). Total genomic DNA was extracted by the CTAB procedure59, from cells entering S phase to G2-M phase, and analyzed on two-dimensional gels. DNA was transfered overnight in 10× SSC on a charged nylon membrane (Sigma) and UV cross-linked on a Stratagene Stratalinker. Hybridization was performed with a 750-bp probe to the 5′ end of the ARG2 gene, labeled by random priming. Quantifications were performed on a Phosphorimager, using the ImageQuant software. For quantification of joint molecules, we took into account both the cone signal and the spike signal (as pictured in Fig. 1b).

Acknowledgments

A.K. is grateful to G. Maffioletti for teaching her the two-dimensional gel electrophoresis technique and helping with her first successful experiments. A.K. and G.-F.R. thank the people who gave them advice concerning two-dimensional gel electrophoresis: M. Foiani, C. Maric, A. Ceschia and A. Kaykov. They also gratefully acknowledge the help of G. Millot for advice concerning the various statistical tests used in this manuscript. They and B.D. also thank their colleagues of the Unité de Génétique Moléculaire des Levures for many fruitful discussions and G. Fischer for careful reading of the manuscript. R.P.A. would like to acknowledge the help of K. Suryanarayanan in installing the SALVADOR program. A.K. was funded by the Ministère de la Recherche and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM). This work was supported by grant 3738 from the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC), grant ANR-05-BLAN-0331 from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche, US National Institutes of Health grant GM063066 to C.H.F., Tufts University FRAC award to C.H.F. and GSC Research Award to R.P.A. B.D. is a member of the Institut Universitaire de France.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.K. and G.-F.R. conceived of and performed the instability and two-dimensional studies on yeast chromosome X; C.H.F. and R.P.A. conceived of and performed the instability and fragility studies on the YAC, with R.S. contributing the rad51Δ (CAG)0 and (CAG)70 fragility analyses; R.B. and G.L. gave expert assistance with two-dimensional gel electrophoresis; A.K., B.D., G.-F.R., C.H.F. and R.P.A. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gatchel JR, Zoghbi HY. Diseases of unstable repeat expansion: mechanisms and common principles. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:743–755. doi: 10.1038/nrg1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirkin SM. DNA structures, repeat expansions and human hereditary disorders. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenzmeier BA, Freudenreich CH. Trinucleotide repeat instability: a hairpin curve at the crossroads of replication, recombination, and repair. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2003;100:7–24. doi: 10.1159/000072836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson CE, Edamura KN, Cleary JD. Repeat instability: mechanisms of dynamic mutations. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:729–742. doi: 10.1038/nrg1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richard GF, Dujon B, Haber JE. Double-strand break repair can lead to high frequencies of deletions within short CAG/CTG trinucleotide repeats. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;261:871–882. doi: 10.1007/s004380050031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richard GF, Cyncynatus C, Dujon B. Contractions and expansions of CAG/CTG trinucleotide repeats occur during ectopic gene conversion in yeast, by a MUS81-independent mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:769–782. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richard GF, Goellner GM, McMurray CT, Haber JE. Recombination-induced CAG trinucleotide repeat expansions in yeast involve the MRE11/RAD50/XRS2 complex. EMBO J. 2000;19:2381–2390. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richard GF, Pâques F. Mini- and microsatellite expansions: the recombination connection. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:122–126. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freudenreich CH, Kantrow SM, Zakian VA. Expansion and length-dependent fragility of CTG repeats in yeast. Science. 1998;279:853–856. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spiro C, et al. Inhibition of FEN-1 processing by DNA secondary structure at trinucleotide repeats. Mol Cell. 1999;4:1079–1085. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweitzer JK, Livingston DM. Expansions of CAG repeat tracts are frequent in a yeast mutant defective in Okazaki fragment maturation. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:69–74. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loeillet S, et al. Genetic network interactions among replication, repair and nuclear pore deficiencies in yeast. DNA Repair (Amst ) 2005;4:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangloff S, McDonald JP, Bendixen C, Arthur L, Rothstein R. The yeast type I topoisomerase Top3 interacts with Sgs1, a DNA helicase homolog: a potential eukaryotic reverse gyrase. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8391–8398. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watt PM, Hickson ID, Borts RH, Louis EJ. SGS1, a homologue of the Bloom’s and Werner’s syndrome genes, is required for maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;144:935–945. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.3.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richard GF, Kerrest A, Lafontaine I, Dujon B. Comparative genomics of hemiascomycete yeasts: genes involved in DNA replication, repair, and recombination. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1011–1023. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu L, Hickson ID. The Bloom’s syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature. 2003;426:870–874. doi: 10.1038/nature02253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ira G, Malkova A, Liberi G, Foiani M, Haber JE. Srs2 and Sgs1-Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell. 2003;115:401–411. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robert T, Dervins D, Fabre F, Gangloff S. Mrc1 and Srs2 are major actors in the regulation of spontaneous crossover. EMBO J. 2006;25:2837–2846. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams MD, McVey M, Sekelsky JJ. Drosophila BLM in double-strand break repair by synthesis-dependent strand annealing. Science. 2003;299:265–267. doi: 10.1126/science.1077198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aboussekhra A, et al. RADH, a gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encoding a putative DNA helicase involved in DNA repair. Characteristics of radH mutants and sequence of the gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:7211–7219. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.18.7211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rong L, Klein HL. Purification and characterization of the SRS2 DNA helicase of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1252–1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krejci L, et al. DNA helicase Srs2 disrupts the Rad51 presynaptic filament. Nature. 2003;423:305–309. doi: 10.1038/nature01577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veaute X, et al. The Srs2 helicase prevents recombination by disrupting Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments. Nature. 2003;423:309–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dupaigne P, et al. The Srs2 helicase activity is stimulated by Rad51 filaments on dsDNA: implications for crossover incidence during mitotic recombination. Mol Cell. 2008;29:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattacharyya S, Lahue RS. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Srs2 DNA helicase selectively blocks expansions of trinucleotide repeats. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7324–7330. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7324-7330.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callahan JL, Andrews KJ, Zakian VA, Freudenreich CH. Mutations in yeast replication proteins that increase CAG/CTG expansions also increase repeat fragility. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7849–7860. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7849-7860.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Napierala M, Parniewski P, Pluciennik A, Wells RD. Long CTG•CAG repeat sequences markedly stimulate intramolecular recombination. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34087–34100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pluciennik A, et al. Long CTG•CAG repeats from myotonic dystrophy are preferred sites for intermolecular recombination. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34074–34086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jankowski C, Nasar F, Nag DK. Meiotic instability of CAG repeat tracts occurs by double-strand break repair in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2134–2139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040460297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gangloff S, Soustelle C, Fabre F. Homologous recombination is responsible for cell death in the absence of the Sgs1 and Srs2 helicases. Nat Genet. 2000;25:192–194. doi: 10.1038/76055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fabre F, Chan A, Heyer WD, Gangloff S. Alternate pathways involving Sgs1/Top3, Mus81/Mms4, and Srs2 prevent formation of toxic recombination intermediates from single-stranded gaps created by DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16887–16892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252652399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freudenreich CH, Stavenhagen JB, Zakian VA. Stability of a CTG/CAG trinucleo-tide repeat in yeast is dependent on its orientation in the genome. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2090–2098. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang S, Jaworski A, Ohshima K, Wells RD. Expansion and deletion of CTG repeats from human disease genes are determined by the direction of replication in E. coli. Nat Genet. 1995;10:213–217. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zahra R, Blackwood JK, Sales J, Leach DRF. Proofreading and secondary structure processing determine the orientation dependence of CAG•CTG trinucleotide repeat instability in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2007;176:27–41. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.069724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miret JJ, Passoa-Brandão L, Lahue RS. Orientation-dependent and sequence-specific expansions of CTG/CAG trinucleotide repeats in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12438–12443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maurer DJ, O’Callaghan BL, Livingston DM. Orientation dependence of trinucleotide CAG repeat instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6617–6622. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alvino GM, et al. Replication in hydroxyurea: it’s a matter of time. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6396–6406. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00719-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lammers M, Follmann H. Deoxyribonucleotide biosynthesis in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). A ribonucleotide reductase system of sufficient activity for DNA synthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1984;140:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhattacharyya S, Lahue RS. Srs2 helicase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae selectively unwinds triplet repeat DNA. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33311–33317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopes M, Cotta-Ramusino C, Liberi G, Foiani M. Branch migrating sister chromatid junctions form at replication origins through Rad51/Rad52-independent mechanisms. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1499–1510. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00473-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flores MJ, Sanchez N, Michel B. A fork-clearing role for UvrD. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:1664–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daee DL, Mertz T, Lahue RS. Postreplication repair inhibits CAG-CTG repeat expansions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:102–110. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01167-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldfarb T, Alani E. Distinct roles for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mismatch repair proteins in heteroduplex rejection, mismatch repair and nonhomologous tail removal. Genetics. 2005;169:563–574. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.035204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugawara N, Goldfarb T, Studamire B, Alani E, Haber JE. Heteroduplex rejection during single-strand annealing requires Sgs1 helicase and mismatch repair proteins Msh2 and Msh6 but not Pms1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9315–9320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305749101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richard GF, Kerrest A, Dujon B. Comparative genomics and molecular dynamics of DNA repeats in eukaryotes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:686–727. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00011-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamath-Loeb AS, Johansson E, Burgers PM, Loeb LA. Functional interaction between the Werner Syndrome protein and DNA polymerase δ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4603–4608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamath-Loeb AS, Loeb LA, Johansson E, Burgers PM, Fry M. Interactions between the Werner syndrome helicase and DNA polymerase δ specifically facilitate copying of tetraplex and hairpin structures of the d(CGG)n trinucleotide repeat sequence. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16439–16446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pelletier R, Krasilnikova MM, Samadashwily GM, Lahue R, Mirkin SM. Replication and expansion of trinucleotide repeats in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1349–1357. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1349-1357.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samadashwily GM, Raca G, Mirkin SM. Trinucleotide repeats affect DNA replication in vivo. Nat Genet. 1997;17:298–304. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopes M, et al. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature. 2001;412:557–561. doi: 10.1038/35087613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Long DT, Kreuzer KN. Regression supports two mechanisms of fork processing in phage T4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6852–6857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711999105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fouché N, Özgür S, Roy D, Griffith JD. Replication fork regression in repetitive DNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6044–6050. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fierro-Fernandez M, Hernandez P, Krimer DB, Schvartzman JB. Replication fork reversal occurs spontaneously after digestion but is constrained in supercoiled domains. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18190–18196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fierro-Fernandez M, Hernandez P, Krimer DB, Schvartzman JB. Topological locking restrains replication fork reversal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1500–1505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609204104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liberi G, et al. Rad51-dependent DNA structures accumulate at damaged replication forks in sgs1 mutants defective in the yeast ortholog of BLM RecQ helicase. Genes Dev. 2005;19:339–350. doi: 10.1101/gad.322605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cobb JA, Bjergbaek L, Shimada K, Frei C, Gasser SM. DNA polymerase stabilization at stalled replication forks requires Mec1 and the RecQ helicase Sgs1. EMBO J. 2003;22:4325–4336. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nieduszynski CA, Knox Y, Donaldson AD. Genome-wide identification of replication origins in yeast by comparative genomics. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1874–1879. doi: 10.1101/gad.385306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raghuraman MK, et al. Replication dynamics of the yeast genome. Science. 2001;294:115–121. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5540.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liberi G, et al. Methods to study replication fork collapse in budding yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2006;409:442–462. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)09026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldfless SJ, Morag AS, Belisle KA, Sutera VAJ, Lovett ST. DNA repeat rearrangements mediated by DnaK-dependent replication fork repair. Mol Cell. 2006;21:595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]