Abstract

Operative treatment of scapular fractures with extension into the glenoid can be a challenging clinical scenario. Though traditionally addressed in an open fashion, the morbidity of this approach, complemented by advancements in arthroscopic technique and instrumentation, has led to increasing use of arthroscopic-assisted fixation. We describe our technique, including pearls and pitfalls, for minimally invasive fixation of Ideberg type III glenoid fractures. This approach minimizes morbidity, allows optimal visualization and reduction, and provides good functional results.

Scapular fractures extending into the glenoid articular surface are a relatively rare and challenging clinical problem.1 Although their extra-articular counterparts can often be addressed nonoperatively, displaced fractures extending into the glenohumeral joint usually require surgical intervention. Ideberg et al.1 classified glenoid fractures into 5 main types, and this classification system remains a useful means of communicating complex fracture patterns, as well as directing the approach to treatment. Open reduction–internal fixation has been the standard treatment and has seen fairly good results; however, this approach has shortcomings. The extensive dissection required for adequate visualization, potential impairment of vascular supply to bony fragments, and postoperative stiffness and weakness have led to an increase in the use of arthroscopic techniques.2,3 As with any intra-articular fracture fixation, the goals are pain relief, return of function, and prevention of long-term sequelae such as arthrofibrosis and osteoarthritis.

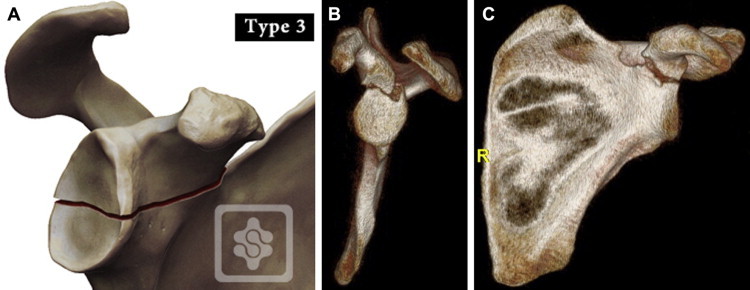

An arthroscopic approach achieves these goals while minimizing the risks previously seen with open surgery. Most glenoid fractures are Ideberg type I, or anterior bony Bankart lesions, and have been the fracture type most commonly addressed arthroscopically since the initial report by Cameron4 in 1998. These are usually fixed with either screws or suture anchors, depending on fragment size and surgeon preference. Our goal is to specifically discuss arthroscopic fixation of the more rare and challenging Ideberg type III fractures (Fig 1). These are characterized by a transverse fracture line that separates the upper one-third to one-half of the glenoid fossa and the coracoid from the rest of the scapula. In addition, we have frequently observed a wedge-shaped fragment posteriorly on the glenoid face in continuity with the transverse fracture line. Ideberg type III fractures are often accompanied by an acromioclavicular (AC) joint separation or fractures to the acromion or clavicle. We describe our technique and tips for arthroscopic-assisted fixation.

Fig 1.

(A) Ideberg type III glenoid fracture. Reproduced with permission from www.shoulderdoc.co.uk. (B, C) Sagittal and coronal 3-dimensional computed tomography reconstructions from a 31-year-old man with an Ideberg type III fracture after a motor vehicle collision.

Surgical Technique

Fractures involving the scapula are frequently associated with high-energy trauma; thus orthopaedists should be wary of other associated life- or limb-threatening issues and ensure that these are addressed first. Standard plain radiographs remain the initial imaging study of choice and can be useful for fracture pattern identification. We recommend upright films because gravity is a major deforming force and supine films may underestimate the amount of displacement of the coracoclavicular space or the glenoid fracture. Computed tomography scans are also often obtained early on in the setting of trauma. We recommend 2-dimensional reformatting in the scapular and parasagittal planes to orient the images in the same way as a standard shoulder magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan for ease of interpretation. In addition, 3-dimensional volume rendering of the scapula (with the humerus subtracted) is very helpful to better elucidate the fracture pattern and to direct preoperative planning.

Although Ideberg type III fractures lend themselves particularly well to arthroscopy and fixation from a superior-to-inferior trajectory, other patterns may dictate a different approach. Table 1 highlights some of the necessities to address these fractures successfully arthroscopically. Certainly, when considering arthroscopic techniques, surgeons must be cognizant not only of surrounding neurovascular structures but also of bony limitations to screw trajectory because the acromion, coracoid, and clavicle will block certain percutaneous approaches.5 If there are accompanying fractures of the acromion or especially the lateral clavicle, they frequently require fixation because their presence further destabilizes the glenoid fracture. We recommend that these be addressed after the glenoid face is anatomically reconstructed—not only to ensure a perfect articular reduction first but also because the fracture or AC separation might allow more flexibility in finding a suitable screw trajectory.

Table 1.

Keys to Success

| Preoperative |

| Initial ruling out of associated life-/limb-threatening injuries |

| Upright plain films |

| 3D CT reconstructions |

| Setup |

| OR staff adept with arthroscopic and trauma surgery |

| Beach-chair positioning appropriate for arthroscopy and screw placement |

| Acquirement of necessary fluoroscopic views before preparation/draping |

| Intraoperative |

| Good fracture visualization and soft-tissue clearance |

| Identification and mobilization of coracoid |

| Anatomic appreciation of suprascapular nerve |

| Starting point and trajectory based on both arthroscopic and fluoroscopic views |

| Postoperative |

| Patient compliance |

| Rehabilitation protocol dictated by fracture pattern and associated injuries |

| High-quality physical therapy |

CT, computed tomography; OR, operating room; 3D, 3-dimensional.

Our preference for these fractures is to operate in a setting with staff accustomed to arthroscopic procedures as well as basic trauma cases. Nerve blocks can be used at the discretion of the surgeon and anesthesiologist. An indwelling interscalene catheter can be beneficial provided that there are no contraindications and the catheter is medial enough to remain out of the operative field. An upright, beach-chair position facilitates arthroscopy and allows for convenient access to the superior aspect of the shoulder for fixation. The C-arm fluoroscope comes in from the contralateral side to obtain Grashey anteroposterior and axillary lateral views as needed.

As long as the soft tissue permits, standard anterior and posterior portals are placed first, and diagnostic arthroscopy is performed initially. Because MRI scans are not routinely obtained at our institution in the setting of scapular trauma, the diagnostic portion of the procedure allows for full visual inspection before fracture fixation. Table 2 provides a brief, stepwise overview of our technique, and Video 1 offers a visual compilation of our experience to date.

Table 2.

Stepwise Technique Overview

| Viewing: posterior (glenohumeral) |

| Working: anterior |

| Perform diagnostic arthroscopy |

| Remove fracture hematoma/callus |

| Resect capsule from rotator interval |

| Viewing: posterior (subacromial) |

| Working: lateral |

| Perform subacromial bursectomy |

| Viewing: lateral (subacromial) |

| Working: anterior, posterior, and Neviaser |

| Retract supraspinatus posteriorly |

| Dissect out coracoid |

| Identify starting point arthroscopically and fluoroscopically |

| Place K-wire(s) into bone but short of fracture site |

| Viewing: posterior (glenohumeral) |

| Working: anterior and Neviaser |

| Use lobster claw on coracoid to obtain reduction |

| Advance K-wire(s) past fracture under arthroscopic visualization |

| Place 3.0- or 4.0-mm partially threaded, cannulated titanium screw(s) |

| Open |

| Address any accompanying fractures of acromion or clavicle |

| Obtain final fluoroscopic images |

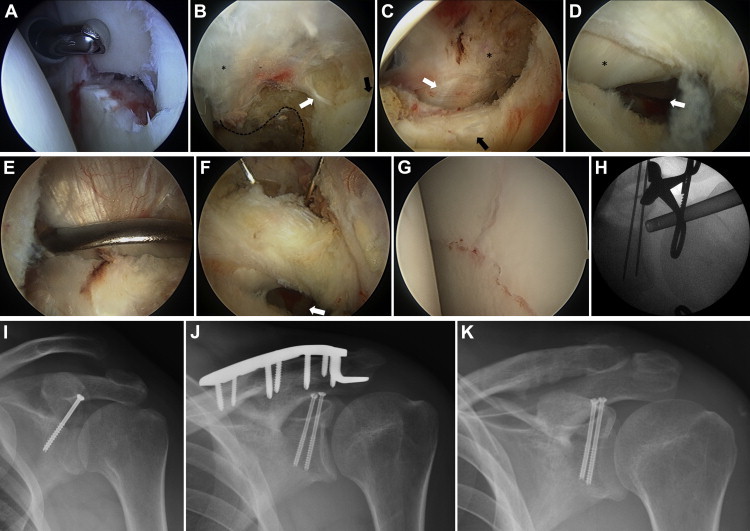

Viewing is conducted through the posterior portal, in line with the glenohumeral joint, roughly at the junction of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. The initial working portal is the anterior portal, just lateral to the tip of the coracoid. Hematoma and fracture callus are removed from the glenohumeral joint and the fracture site (Fig 2A). The rotator interval capsule is resected widely to allow for full access and visualization of the inferior and lateral coracoid. Transitioning to the subacromial space, we continue to view from posterior but now use a lateral working portal to perform a standard bursectomy. The coracoacromial ligament is generally not taken down because, depending on the fracture pattern, this may be a stabilizing structure. Then, viewing from lateral (within the subacromial space), the surgeon brings a small Ragnell retractor through the posterior portal to capture the supraspinatus tendon and retract it posteriorly. The free edge of the supraspinatus should be evident from the prior rotator interval capsular resection. Then, working from an anterior subacromial portal, or potentially an anterolateral portal if the coracoid limits access, the surgeon dissects out the space just posterolateral to the coracoid (Fig 2 B and C). This step is similar to the exposure of the posterior coracoid and supraspinous fossa described by Lafosse and Tomasi6 for suprascapular nerve release.

Fig 2.

(A) Fracture site viewed from posterior portal. (B) Viewing from lateral, the coracoacromial ligament (asterisk) is followed back to the coracoid (dashed line). The lateral coracoid is then followed to the coracoclavicular ligaments (white arrow) and the superior pole of the glenoid with the screw starting point (black arrow). (C) The capsule of the rotator interval has been fully resected, showing the coracoid (asterisk), conjoined tendon (white arrow), and subscapularis (black arrow). The medial portion of the biceps sling is not disturbed. (D) Viewing from lateral, a Ragnell retractor is used to pull the supraspinatus posteriorly. The biceps tendon (asterisk) and fracture line (arrow) are visible. (E) Serrated reduction clamp (lobster claw) on coracoid. (F) Superior K-wires are passed to just short of the fracture site with constant evaluation back and forth from the wires to the fracture (arrow). The surgeon should keep the arthroscope oriented with the long axis of the glenoid to ensure that no articular penetration occurs. (G) Arthroscopic reduction viewed from posterior portal. (H) Fluoroscopic image of reduction and temporary stabilization. (I) Postoperative plain films of final fixation (patient 1) and (J) with addition of clavicle hook plate (patient 2) and (K) subsequent removal.

The intra-articular surface of the glenohumeral joint is then visualized by viewing inferiorly through the opening in the rotator interval (Fig 2D). This allows the appropriate screw trajectory away from the suprascapular nerve, articular surface, and supraspinatus tendon. A Kirschner wire (K-wire) is placed through the Neviaser portal, and the appropriate starting point is selected with the aid of intraoperative fluoroscopy (Fig 2B). The K-wire is placed only a few millimeters into the bone before the posterior retractor is removed. We have found this technique more helpful than prior descriptions of using an anterior cruciate ligament drill guide or a wire in the joint paralleling the glenoid face7 because it allows freedom of movement and excellent visualization of both the starting point and the glenoid face.

The camera is replaced into the glenohumeral joint through the posterior viewing portal. A serrated reduction clamp (lobster claw) is placed through the anterior portal, piercing the coracoacromial ligament and grasping the coracoid securely (Fig 2E). Because the superior glenoid face is in continuity with the coracoid, this allows for manipulation of the fracture while under arthroscopic visualization (Fig 2F). The serrated reduction clamp is useful for aligning the articular surface of the fracture, but because the coracoclavicular ligaments are generally intact, they produce a rotational deforming force in the scapular plane. Having an assistant provide downward pressure to the clavicle aids in reduction. When appropriate reduction is obtained, the K-wire is advanced inferiorly across the fracture (Fig 2G). C-arm fluoroscopy is then used to verify the appropriate starting point, trajectory, and reduction (Fig 2H). A second K-wire is frequently used either for provisional reduction or for a second screw. We prefer partially threaded, cannulated screws with either a 3.0- or 4.0-mm diameter (Synthes, West Chester, PA); we also use titanium in case a shoulder MRI scan is required in the future. Of note, a 3.5-mm titanium clavicle hook plate (Synthes) is frequently a useful adjunct to treat associated AC joint injuries or lateral clavicle fractures. The strength of this portion of the construct shares the load with the small, thin cannulated screws holding the articular reduction. Final radiographs are obtained at the conclusion of the case (Fig 2 I and J).

A standard sling is used immediately after surgery. Postoperative care involves early passive range of motion—generally with pendulums and supine, well arm–assisted motion within case-specific parameters specified by the surgeon. Given the rotational forces at the AC joint, we generally do not allow passive flexion beyond 90° for at least 6 weeks if such an injury exists. After discharge, patients continue formal physical therapy with a concomitant home exercise regimen; unless there are other competing factors, early and sustained motion is critical to long-term function. Patients are followed up at regular intervals both clinically and radiographically with upright plain films. After bony healing is obtained, the sling is discontinued and a progression to active motion (and eventually strengthening) is initiated. If a hook plate has been used, it is routinely removed after 3 to 4 months to avoid acromial erosion and subacromial impingement (Fig 2K).

Discussion

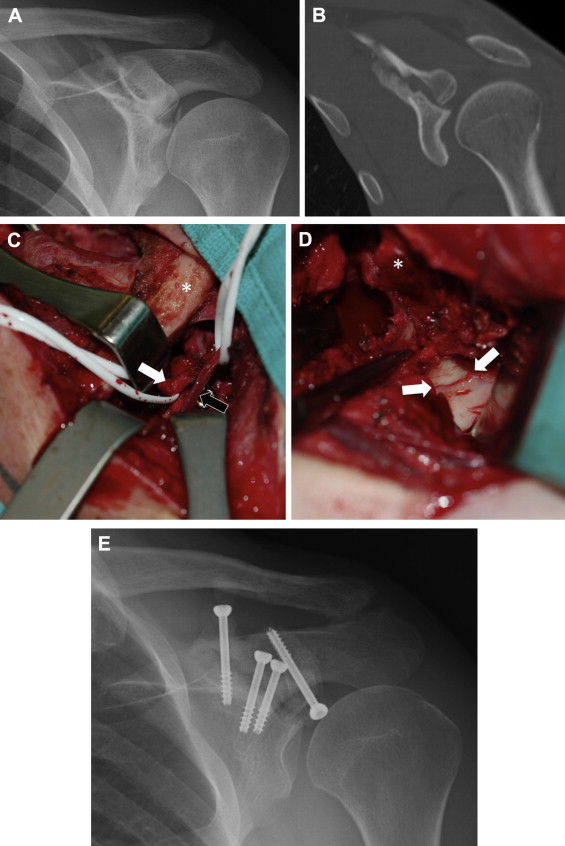

Intra-articular glenoid fractures remain a difficult problem. Though traditionally addressed in an open fashion (Fig 3), the morbidity of this procedure has led to increasing use of arthroscopy because of some key advantages with the latter technique (Table 3). Whereas bony Bankart lesions are now commonly addressed arthroscopically, Ideberg type III fractures present a more rare and difficult scenario. However, we believe that the benefits of arthroscopy for this fracture pattern are even more pronounced because the open surgical technique is more invasive than the deltopectoral approach used for anterior glenoid rim fractures.3 Even established Ideberg type III nonunions have been successfully addressed with an arthroscopic approach with bone grafting.8

Fig 3.

A 26-year-old man with an established nonunion of an Ideberg type III fracture. An open approach was required to mobilize the fibrous nonunion and to free the suprascapular nerve, which had electromyographic changes and was entrapped in callus. Had this case been managed arthroscopically initially, such extensive surgery may not have been required. (A) Anteroposterior radiograph showing both articular step-off and traction of suprascapular nerve at suprascapular notch. (B) Coronal computed tomography scan showing articular incongruity and nonunion. (C) View from superior of combined deltopectoral and supraspinatus fossa approach. The clavicle (asterisk) is medial. The suprascapular nerve (white arrow) is visible, as is the suprascapular artery (black arrow), with an adjacent screw head. (D) View from superolateral showing glenoid articular reduction (arrows) and coracoid osteotomy (asterisk). As in the arthroscopic case, the rotator interval has been opened widely and the supraspinatus is retracted laterally. (E) Final fixation. Multiple screws were used more medially given the need to reduce the suprascapular notch.

Table 3.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Arthroscopic Glenoid Fracture Fixation

| Advantages |

| Excellent fracture visualization |

| Soft-tissue preservation |

| Minimal disturbance to vascular supply |

| Decreased postoperative stiffness/weakness |

| Disadvantages |

| Technical difficulty |

| No visualization of neurovascular structures |

| Fixation options dictated by fracture type |

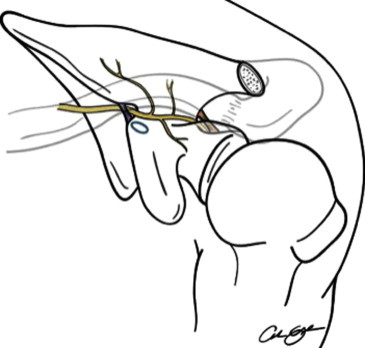

There are certain neurovascular considerations that must be addressed specifically with Ideberg type III fractures: Most notably, the suprascapular nerve is at risk with superior screw placement (Fig 4). As the main branch passes through the suprascapular notch, it sends off motor fibers to the supraspinatus as well as a sensory branch to the glenohumeral joint. It then traverses the spinoglenoid notch, hugging the posterior glenoid neck as it sends innervation to the infraspinatus.6,9 Although care must always be taken to not penetrate the articular surface, a screw position that wanders too far medially toward the glenoid neck or posteriorly toward the spinoglenoid notch dramatically increases the risk of suprascapular nerve injury.

Fig 4.

Course of suprascapular artery and nerve.

Reprinted with permission.9

Marsland and Ahmed5 conducted a cadaveric study looking specifically at the anatomic structures at risk with percutaneous placement of glenoid screws from multiple points. Wires were placed at relatively constant angles, and the shoulders were then dissected to determine the distance to the nearest neurovascular structures. Although a variety of positions were evaluated, the 2 most relevant to Ideberg type III fractures were the superior approach (anteromedial to the AC joint) and the Neviaser portal. Ultimately, these were found to be the 2 safest wire placements: No neurovascular injuries occurred with a mean distance of 24.3 mm and 19.9 mm, respectively, to the suprascapular nerve. Figure 5 demonstrates the safe use of a single screw from the Neviaser portal with a good (albeit early) postoperative result.

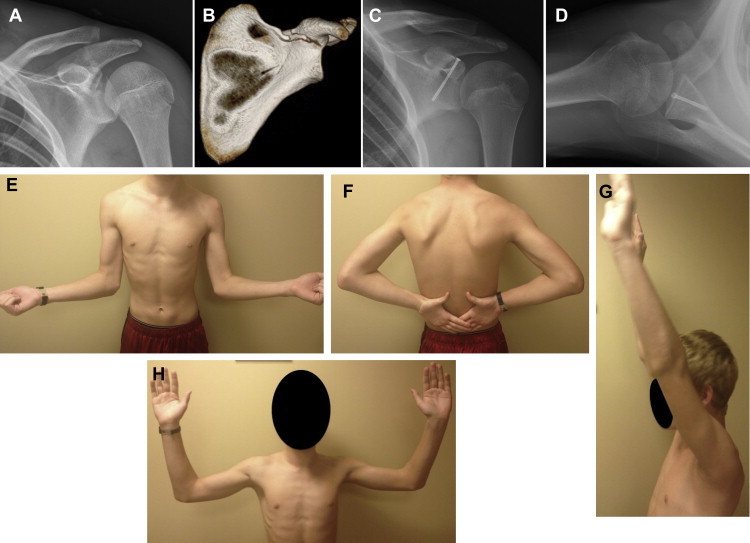

Fig 5.

(A) Anteroposterior radiograph and (B) coronal 3-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction from a 14-year-old boy with an Ideberg type III fracture after a motocross accident. (C) Anteroposterior and (D) axillary lateral views of final fixation. (E-H) Photographs showing postoperative range of motion at 7 weeks.

Because of the nature of these injuries and relatively recent advent of arthroscopic treatment, few data exist to define the long-term outcomes. Yang et al.7 have published the largest series to date, comprising 18 patients with Ideberg type III fractures and a minimum of 2 years' follow-up. They used arthroscopic-aided reduction and fixation through the Neviaser portal with a 4.0-mm cannulated screw, and their outcomes at greater than 2 years were excellent. They noted a 100% union rate at 3 months and good scores on visual analog scale; American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; Constant-Murley; and University of California, Los Angeles metrics. Mean motion was as follows: forward flexion, 163°; external rotation in neutral abduction, 67°; and internal rotation to T8. There were no known neurovascular injuries, although no electrodiagnostic testing was performed in 5 patients with atrophy of the supraspinous fossa. Overall, the data of Yang et al. are very promising and highlight the results that are possible with meticulously applied arthroscopic techniques.

In summary, Ideberg type III glenoid fractures are relatively rare but present an opportunity to use an arthroscopic approach in an effort to improve patient outcomes. We believe that this can be achieved safely and with less morbidity than open techniques, and the early results are excellent.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: G.E.G. receives support from Tornier, AO/Synthes, Zimmer, and DJO.

Supplementary Data

Technique for arthroscopic-assisted fixation of Ideberg type III glenoid fractures.

References

- 1.Ideberg R., Grevsten S., Larsson S. Epidemiology of scapular fractures. Incidence and classification of 338 fractures. Acta Orthop. 1995;66:395–397. doi: 10.3109/17453679508995571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gramstad G.D., Marra G. Treatment of glenoid fractures. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;3:102–110. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavanagh B.F., Bradway J.K., Cofield R. Open reduction and internal fixation of displaced intra-articular fractures of the glenoid fossa. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:479–484. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199304000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron S.E. Arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation of an anterior glenoid fracture. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:743–746. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marsland D., Ahmed H.A. Arthroscopically assisted fixation of glenoid fractures: A cadaver study to show potential applications of percutaneous screw insertion and anatomic risks. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:481–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lafosse L., Tomasi A. Technique for endoscopic release of suprascapular nerve entrapment at the suprascapular notch. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;7:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang H.-B., Wang D., He X.-J. Arthroscopic-assisted reduction and percutaneous cannulated screw fixation for Ideberg type III glenoid fractures: A minimum 2-year follow-up of 18 cases. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1923–1928. doi: 10.1177/0363546511408873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sears B.W., Lazarus M.D. Arthroscopically assisted percutaneous fixation and bone grafting of a glenoid fossa fracture nonunion. Orthopedics. 2012;35:e1279–e1282. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120725-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatia S., Chalmers P.N., Yanke A.B., Romeo A.A., Verma N.N. Arthroscopic suprascapular nerve decompression: Transarticular and subacromial approach. Arthrosc Tech. 2012;1:e187–e192. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Technique for arthroscopic-assisted fixation of Ideberg type III glenoid fractures.