Abstract

Context:

Obese men with normal semen parameters exhibit reduced fertility but few prospective data are available.

Objective:

This study aimed to determine the effect of male factors and body mass among the Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome II (PPCOS II) participants.

Methods:

This is a secondary analysis of the PPCOS II trial. A total of 750 infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) were randomly assigned to up to receive five cycles of letrozole or clomiphene citrate. Females were 18–39-years-old and had a male partner with sperm concentration of at least 14 million/mL who consented to regular intercourse. Analysis was limited to couples with complete male partner information (n = 710).

Results:

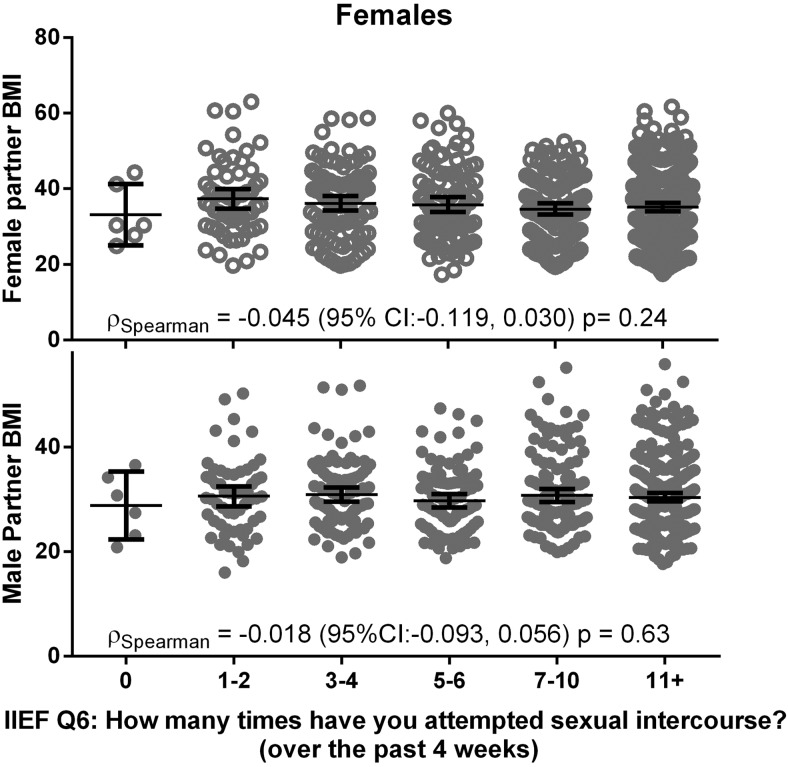

Male body mass index (BMI) was higher in couples who failed to conceive (29.5 kg/m2 vs 28.2 kg/m2; P = .039) as well as those who did not achieve a live birth (29.5 kg/m2 vs 28.1 kg/m2; P = .047). At least one partner was obese in 548 couples (77.1%). A total of 261 couples were concordant for obesity (36.8%). After adjustment for female BMI, the association of male BMI with live birth was no longer significant (odds ratio [OR] = 0.85; 95 % confidence interval [CI], 0.68–1.05; P = .13). Couples in which both partners smoked had a lower chance of live birth vs nonsmokers (OR = 0.20; 95 % CI, 0.08–0.52; P = .02), whereas there was not a significant effect of female or male smoking alone. Live birth was more likely in couples with at least three sexual intercourse attempts over the previous 4 weeks (reported at baseline) as opposed to couples with lesser frequency (OR = 4.39; 95 % CI, 1.52–12. 4; P < .01).

Conclusions:

In this large cohort of obese women with PCOS, effect of male obesity was explained by female BMI. Lower chance of success was seen among couples where both partners smoked. Obesity and smoking are common among women with PCOS and their partners and contribute to a decrease in fertility treatment success.

Female obesity is a well-recognized risk factor for subfertility and reduced reproductive fitness. Detrimental effects of female obesity on pregnancy and childbearing are well known and include menstrual dysfunction (1) and associated infertility (2), recurrent miscarriage (3), increased congenital anomalies (4), preterm birth (both iatrogenic [5] and spontaneous [6]), stillbirth (7), and potentially harmful metabolic programming of the offspring (8). Multiple epidemiologic studies suggest that couples with coexisting female and male obesity have a further decline in fertility. In a study of more than 1300 U.S. men, overweight and obese men had a 12% increase in infertility after adjustment for female body mass index (BMI) (9). This finding has been confirmed by at least two additional large-scale observational studies whereby an elevated risk for infertility was present among couples if the male partner was overweight or obese (10, 11). The detrimental effect of male adiposity on fertility persists independently of coital frequency, implying that this effect is not simply a result of confounding due to obesity-related sexual dysfunction (10). Moreover, even obese men with normal semen parameters exhibit diminished fertility in both natural (12) and assisted conception (13, 14), suggesting that qualitative or functional semen factors may also play a role. However, most of the published studies are retrospective or have relied on the male partner information that was collected separately as an ancillary analysis. There is lack of prospectively collected data regarding the effect of male phenotype and obesity on fertility and expert consensus has recommended that male data be routinely collected in clinical trials of infertility (15, 16).

The Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome II trial (PPCOS II), conducted by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Reproductive Medicine Network, was a double-blind, prospective, randomized trial of either letrozole or clomiphene citrate for treatment of infertility among anovulatory women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). The primary outcome of the trial was live birth during the treatment period for up to 5 cycles of ovulation induction (17). Higher live birth rate was demonstrated for women treated with letrozole (18). Women with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 had a significantly lower live birth rate than their leaner counterparts. In this secondary analysis, we hypothesized that male obesity and other male factors were independently associated with likelihood of live birth among PPCOS II couples.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We performed a secondary data analysis of the PPCOS II trial data. PCOS was defined by modified Rotterdam criteria (17). All recruited women with PCOS were infertile and seeking fertility treatment. The institutional review board at each study site approved the protocol and all subjects (men and women) gave written informed consent. All pregnancies were followed to completion. Male sexual function was assessed at baseline with the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), a multidimensional scale of 15 questions scored from 0 to 5, for assessment of erectile dysfunction (ED) (19). Lower scores indicate ED. This measure addresses the relevant domains of male sexual function (erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction). In the current analysis, each IIEF response is reported as Inadequate/Unsatisfactory (worst two responses) vs Adequate/Satisfactory or greater for every item (best three or four responses). The Inadequate/Unsatisfactory category corresponds to responses of 0–1 for items 1 through 10, and responses of 1–2 for items 11 through 15 (Supplemental Table 1). Moreover, an abridged five-item version of the IIEF, also known as the Sexual Health Inventory of Men (SHIM), was used to determine the presence and severity of ED (20). For SHIM, a cumulative score of 5–7 indicates severe ED, 8–21 indicates mild or moderate, and 22–25 indicates absence of ED. Smoking history was obtained by questionnaire at baseline (and not at later time points) in both male and females.

Analytic sample

The PPCOS II study recruited 750 women with PCOS and their male partners. Female participants were 18–39-years-old, had at least one patent fallopian tube and normal uterine cavity. Male participants had sperm concentration of at least 14 million per milliliter in at least one ejaculate within the past year, with some motile sperm. All subjects consented to regular intercourse and females kept a prospective intercourse diary (17). Biometric and hormonal measures were collected at baseline. Men self reported height and weight. Female height and weight were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg. Forty couples (5.6%) were excluded from the present analysis because of missing male body mass, yielding an analytic sample of 710.

Statistical methods

Differences in baseline biometric characteristics and IIEF responses were compared across pregnancy outcomes. Conception was defined by a positive serum human chorionic gonadotropin. Clinical pregnancy was defined as an intrauterine pregnancy with presence of fetal heart motion on ultrasonography. BMI was categorized by using the World Health Organization cut points of underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (>30 kg/m2) (21). To assess associations that may potentially covary with male adiposity, subject characteristics were analyzed by male obesity. To investigate the independent and combined associations between female and male obesity and smoking on success of treatment, concordance within the couple was assessed. Univariate analyses were conducted with t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Differences for obesity and smoking concordance were estimated by logistic regression with and without adjusting for each partner's age and sperm concentration. Multivariable logistic regression was also conducted with live birth as the outcome. Likelihood of live birth was estimated with adjustment for parameters based on significant differences in univariate analyses. The final model included age, BMI, and smoking of each partner as well as sperm concentration, intercourse frequency from IIEF, and study drug randomization (letrozole or clomiphene). During model selection, a multiplicative interaction term was created for male and female smoking to test for the synergistic effect of this combination. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding underweight men (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) and those with class III obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2) to examine whether very high or very low male body mass had an effect on the outcome of fertility treatment. All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

Results

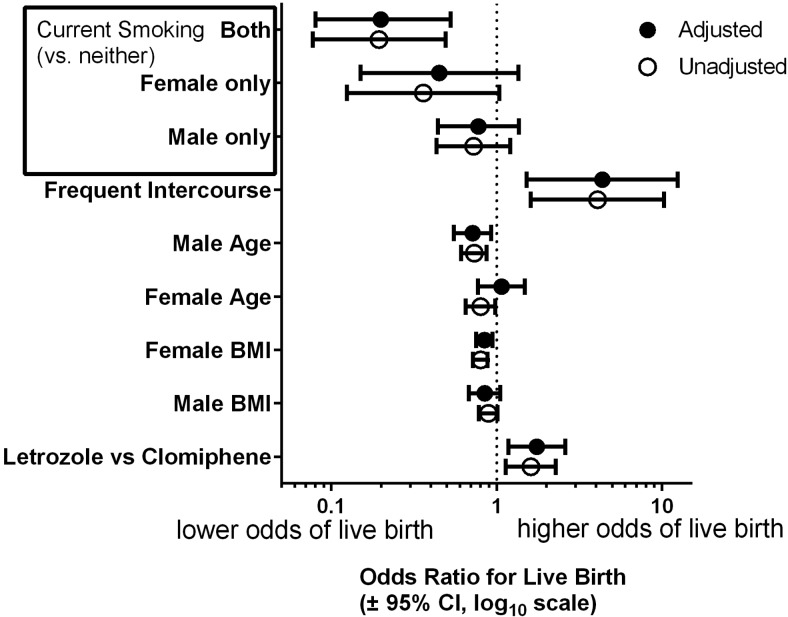

In our analytic sample, 245 couples achieved pregnancy (34.5%) and 171 women had a live birth (24.0%). Among male partner characteristics, BMI and current smoking were negatively associated with all pregnancy outcomes in unadjusted analyses (Table 1). Significantly higher male BMI was observed in couples who failed to conceive as well as those who did not have a live birth. Among male sexual function measures, infrequent intercourse at baseline (<3 attempts over 4 weeks) was negatively associated with pregnancy and live birth (Figure 1). ED was uncommon and was not associated with any pregnancy outcomes. The patient and cycle determinants were evaluated by male obesity to determine whether any variables potentially mediated the relationship between success of treatment and male adiposity (Table 2). On average, obese men were older and were less likely to smoke. Couples with an obese male had a significantly higher female BMI and an older female partner. There was no significant association between IIEF, SHIM, or ED scores by male obesity.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the PPCOS II Female and Male Participants by Pregnancy Outcomes

| Variable | AP |

CP |

LB |

P Values for Differences |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | AP | CP | LB | |

| n | 245 | 465 | 179 | 531 | 171 | 539 | |||

| Treatment with Letrozole | 146 (59.6) | 210 (45.2) | 107 (59.8) | 249 (46.9) | 101 (59.1) | 255 (47.3) | <.001 | .003 | .007 |

| Female | |||||||||

| Age, y | 28.0 (26.0–31.0) | 29.0 (26.0–32.0) | 28.0 (26.0–31.0) | 29.0 (26.0–32.0) | 28.0 (26.0–31.0) | 29.0 (26.0–32.0) | .171 | .099 | .059 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 32.3 (25.6–39.1) | 36.5 (30.0–42.8) | 31.5 (25.6–39.0) | 36.1 (29.4–42.4) | 31.2 (25.6–38.7) | 36.1 (29.6–42.4) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Ever smoking | 96 (39.2) | 207 (44.5) | 78 (43.6) | 225 (42.4) | 76 (44.4) | 227 (42.1) | .172 | .778 | .592 |

| Current smoking | 17 (6.9) | 88 (18.9) | 9 (5.0) | 96 (18.1) | 9 (5.3) | 96 (17.8) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Male | |||||||||

| Age, y | 30.0 (27.0–33.0) | 32.0 (28.0–35.0) | 30.0 (27.0–33.0) | 31.0 (28.0–35.0) | 30.0 (27.0–33.0) | 31.0 (28.0–35.0) | <.001 | .003 | <.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.2 (24.7–33.3) | 29.5 (25.8–34.3) | 28.2 (25.0–33.2) | 29.5 (25.7–34.3) | 28.1 (25.0–33.2) | 29.5 (25.7–34.3) | .039 | .064 | .047 |

| Ever smoking | 115 (46.9) | 253 (54.4) | 78 (43.6) | 290 (54.6) | 77 (45.0) | 291 (54.0) | .058 | .011 | .041 |

| Current smokinga | 45 (39.1) | 128 (50.6) | 27 (34.6) | 146 (50.3) | 27 (35.1) | 146 (50.2) | .041 | .013 | .018 |

| Ever alcohol intake | 218 (90.1) | 409 (88.1) | 160 (90.9) | 467 (88.1) | 156 (92.3) | 471 (87.7) | .439 | .308 | .098 |

| Current alcohol intakea | 188 (86.2) | 322 (78.7) | 138 (86.3) | 372 (79.7) | 135 (86.5) | 375 (79.6) | .022 | .065 | .054 |

| Sperm concentration, million/mL | 64.5 (38.0105) | 59.7 (32.0–97.0) | 65.0 (37.2–109) | 60.0 (33.0–97.0) | 65.0 (37.0–109) | 60.0 (33.0–97.0) | .085 | .045 | .069 |

| History of no prior pregnancy | 148 (60.4) | 262 (56.3) | 112 (62.6) | 298 (56.1) | 106 (62.0) | 304 (56.4) | .297 | .131 | .197 |

| Male International Index of Erectile Function measures (poor vs otherwise) | |||||||||

| Erection frequency: ≤ a few times | 2 (0.8) | 9 (2.0) | 2 (1.1) | 9 (1.7) | 2 (1.2) | 9 (1.7) | .256 | .595 | .653 |

| Erection firmness: ≤ a few times | 1 (0.4) | 11 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (2.3) | .056 | .043 | .050 |

| Penetration ability: ≤ a few times | 2 (0.8) | 7 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | 8 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | 8 (1.5) | .443 | .331 | .365 |

| Erection maintenance: ≤ a few times | 2 (0.8) | 7 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | 8 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | 8 (1.5) | .443 | .331 | .365 |

| Difficulty in maintaining: difficult or more | 3 (1.3) | 13 (2.9) | 2 (1.1) | 14 (2.7) | 2 (1.2) | 14 (2.7) | .185 | .24 | .279 |

| Intercourse frequency: ≤ 2 attempts | 14 (5.9) | 50 (11.0) | 7 (4.0) | 57 (11.0) | 5 (3.0) | 59 (11.2) | .027 | .006 | .001 |

| Intercourse satisfaction: ≤ a few times | 1 (0.4) | 9 (2.0) | 1 (0.6) | 9 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 9 (1.7) | .103 | .268 | .299 |

| Intercourse enjoyment:≤ fairly enjoyable | 10 (4.2) | 21 (4.6) | 6 (3.4) | 25 (4.8) | 6 (3.6) | 25 (4.7) | .807 | .452 | .542 |

| Ejaculation frequency: almost never | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) | .969 | .743 | .704 |

| Orgasm frequency: almost never | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | .692 | .996 | .961 |

| Desire frequency: ≤ a few times | 5 (2.1) | 10 (2.2) | 4 (2.3) | 11 (2.1) | 4 (2.4) | 11 (2.1) | .93 | .891 | .806 |

| Desire level: ≤ moderate | 54 (22.7) | 122 (26.8) | 36 (20.7) | 140 (26.9) | 36 (21.7) | 140 (26.5) | .243 | .102 | .212 |

| Overall sex: ≤ moderately dissatisfied | 4 (1.7) | 10 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | 12 (2.3) | 2 (1.2) | 12 (2.3) | .649 | .347 | .393 |

| Relationship: ≤ moderately dissatisfied | 2 (0.8) | 9 (2.0) | 1 (0.6) | 10 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 10 (1.9) | .256 | .218 | .245 |

| Erection confidence: low or less | 1 (0.4) | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.1) | .36 | .154 | .167 |

Abbreviations: AP, achieved pregnancy; CP, clinical pregnancy; LB, live birth.

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%). P values for χ2 or t test.

For detailed description of International Index Of Erectile Function (IIEF) scores, see text and Supplemental Table.

Denominator for current smoking and alcohol intake is among subset who indicated “ever.”

Figure 1.

Association of live birth with measures of erectile function by IIEF at study baseline. Unadjusted prevalence of male sexual function measures by live birth. Each bar represents responses to IIEF questions that classified as inadequate/unsatisfactory. Higher prevalence of infrequent sexual intercourse (<3 attempts during the past 4 weeks) was more likely in couples who did not achieve a live birth (11.2% vs 3%). No significant differences were observed for any other measure.

Table 2.

Association of Male Obesity With Anthropometric Characteristics of Both Partners

| Variable | BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | BMI < 30 kg/m2 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 388 | 322 | |

| Treatment with letrozole | 161 (50.0) | 195 (50.3) | .945 |

| Female | |||

| Age, y | 29.0 (26.0, 32.0) | 28.0 (25.0, 31.0) | <.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 37.8 (31.6, 43.4) | 32.6 (25.6, 39.9) | <.001 |

| Ever smoking | 146 (45.3) | 157 (40.5) | .191 |

| Current smoking | 45 (14.0) | 60 (15.5) | .578 |

| Male | |||

| Age, y | 31.0 (28.0, 35.0) | 30.0 (27.0, 34.0) | .030 |

| Ever smoking | 157 (48.8) | 211 (54.4) | .135 |

| Current smokinga | 62 (39.5) | 111 (52.6) | .013 |

| Ever alcohol intake | 288 (90.0) | 339 (87.8) | .361 |

| Current alcohol intakea | 228 (79.2) | 282 (83.2) | .198 |

| Sperm concentration, million/mL | 60.3 (34.0, 103.7) | 61.1 (34.0, 98.5) | .924 |

| History of no prior pregnancy | 180 (55.9) | 230 (59.3) | .360 |

| Male International Index of Erectile Function Measures (poor vs otherwise) | |||

| Erection frequency: ≤ a few times | 4 (1.3) | 7 (1.8) | .564 |

| Erection firmness: ≤ a few times | 3 (1.0) | 9 (2.4) | .161 |

| Penetration ability: ≤ a few times | 2 (0.6) | 7 (1.8) | .168 |

| Erection maintenance: ≤ a few times | 1 (0.3) | 8 (2.1) | .040 |

| Difficulty in maintaining: Difficult or more | 5 (1.6) | 11 (2.9) | .265 |

| Intercourse frequency: ≤ 2 attempts | 34 (10.9) | 30 (7.9) | .175 |

| Intercourse satisfaction: ≤ a few times | 4 (1.3) | 6 (1.6) | .751 |

| Intercourse enjoyment: ≤ fairly enjoyable | 16 (5.1) | 15 (3.9) | .446 |

| Ejaculation frequency: almost never | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | .689 |

| Orgasm frequency: almost never | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.8) | .414 |

| Desire frequency:≤ a few times | 6 (1.9) | 9 (2.4) | .697 |

| Desire level: ≤ moderate | 79 (25.3) | 97 (25.4) | .983 |

| Overall sex life:≤ moderately dissatisfied | 6 (1.9) | 8 (2.1) | .873 |

| Relationship: ≤ moderately dissatisfied | 5 (1.6) | 6 (1.6) | .973 |

| Erection confidence: low or less | 1 (0.3) | 5 (1.3) | .163 |

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%). P values for χ2 or t test.

Denominator for current smoking and current alcohol is among subset who indicated “ever.”

Table 3 shows the effect of obesity concordance on success of treatment with couple as the unit of analysis. At least one partner was obese for most participants (548 couples or 77.1%). Obesity concordance was observed for 261 couples (36.8%). However, only couples with an obese female partner had a lower chance of live birth compared with the nonobese couples. Table 4 shows the effect of smoking concordance with couple as the unit of analysis. Only couples who were both current smokers had a lower chance of live birth compared with nonsmokers.

Table 3.

Likelihood of Live Birth in PPCOS II by Female and Male Body Mass Concordance, n = 710

| BMI, kg/m2 |

N (%) | Unadjusted OR, 95% CI | P Value | Adjusted OR,a 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | |||||

| <30 | <30 | 162 (22.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| <30 | ≥30 | 61 (8.6) | 0.623 (0.328–1.186) | .54 | 0.638 (0.331–1.232) | .46 |

| ≥30 | <30 | 226 (31.8) | 0.357 (0.225–0.568) | .008 | 0.339 (0.211–0.544) | .004 |

| ≥30 | ≥30 | 261 (36.8) | 0.392 (0.252–0.608) | .028 | 0.388 (0.247–0.61) | .03 |

Adjusted for age of each partner and sperm concentration.

Table 4.

Association of Reported Smoking Information With Likelihood of Live Birth in PPCOS II

| Variable | Live Birth | No Live Birth | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 171 | 539 | |

| Female | |||

| Ever smoking | 76 (44.4) | 227 (42.1) | .592 |

| Current smokinga | 9 (5.3) | 96 (17.8) | <.001 |

| Cigarettes per day | .575 | ||

| 1–10 | 66 (38.6) | 190 (35.3) | |

| 11–20 | 8 (4.7) | 34 (6.3) | |

| 21–40 | 2 (1.2) | 2 (0.4) | |

| >40 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Duration of smoking, y | .102 | ||

| <1 | 23 (13.5) | 46 (8.5) | |

| 1–5 | 33 (19.3) | 79 (14.7) | |

| 6–10 | 14 (8.2) | 67 (12.4) | |

| 11–15 | 4 (2.3) | 24 (4.5) | |

| >15 | 2 (1.2) | 11 (2.0) | |

| Time since quitting, y | .086 | ||

| <1 | 12 (17.9) | 37 (28.2) | |

| 1–5 | 23 (34.3) | 50 (38.2) | |

| 6–10 | 25 (37.3) | 29 (22.1) | |

| 11–15 | 4 (6.0) | 13 (9.9) | |

| >15 | 3 (4.5) | 2 (1.5) | |

| Male | |||

| Ever smoking | 77 (45.0) | 291 (54.0) | .041 |

| Current smokinga | 27 (35.1) | 146 (50.2) | .018 |

| Cigarettes per day | |||

| 1–10 | 53 (31.4) | 185 (34.7) | .248 |

| 11–20 | 18 (10.7) | 81 (15.2) | |

| 21–40 | 4 (2.4) | 17 (3.2) | |

| >40 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | |

| Duration of smoking, y | |||

| <1 | 14 (8.3) | 63 (11.8) | .241 |

| 1–5 | 25 (14.8) | 71 (13.3) | |

| 6–10 | 18 (10.7) | 69 (13.0) | |

| 11–15 | 11 (6.5) | 57 (10.7) | |

| >15 | 7 (4.1) | 24 (4.5) | |

| Time since quitting, y | |||

| <1 | 21 (43.8) | 49 (35.5) | .148 |

| 1–5 | 7 (14.6) | 11 (8.0) | |

| 6–10 | 10 (20.8) | 41 (29.7) | |

| 11–15 | 0 (0.0) | 10 (7.2) | |

| >15 | 21 (43.8) | 49 (35.5) | .148 |

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%). P values for χ2 or t test.

Denominator for current smoking and current alcohol is among subset who indicated “ever.”

The final multivariate analysis (Figure 2) revealed that, after adjustment for female BMI, randomization treatment arm and other parameters, the association of male BMI with live birth was not significant (odds ratio [OR] = 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.68–1.05; P = .13). The negative effect of smoking persisted in the final model. Couples where both partners smoked had a lower chance of live birth compared with the nonsmokers (OR = 0.20; 95% CI, 0.08–0.53; P = .02). Interestingly, frequent sexual intercourse at baseline (Figure 3) was independently associated with live birth in the multivariate analysis (OR = 4.39; 95% CI, 1.52–12.40; P < .01). Randomization to letrozole was likewise significant in the final model (P < .01; Figure 2). A sensitivity analysis was performed to determine whether the extremes of male BMI might have biased the observed associations in the final model. For all tested subsets, no changes in significance were observed for the reported ORs for adiposity, smoking or intercourse frequency and the point estimates remained similar to that of the full cohort.

Figure 2.

Likelihood of live birth in PPCOSII by specified determinant multivariable logistic regression analysis with adjustment for age, smoking and BMI of both partners, as well as intercourse frequency (≥3 intercourse attempts during the past 4 weeks vs fewer as assessed at baseline). Smoking is categorized as a four-category variable: present in partners, female only, male only vs neither partner smoking.

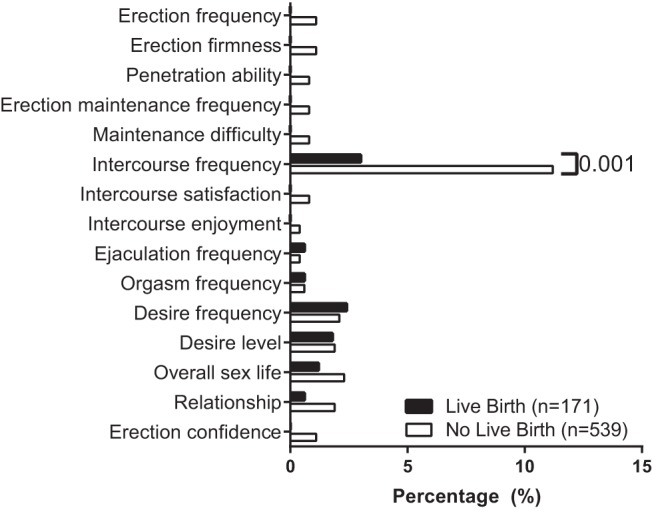

Figure 3.

Lack of an association for BMI with reported frequency of sexual activity in PPCOS II. Unadjusted prevalence of sexual intercourse frequency by male and female BMI. Each cluster represents responses to IIEF question 6, assessed at study baseline: “How many times have you attempted sexual intercourse over the past 4 weeks?”

Discussion

In this large cohort of women with PCOS, there was no independent effect of male obesity on the success of fertility treatment and live birth. Prevalence of obesity was high among female participants and their male partners. Interventions to combat prepregnancy obesity with lifestyle modifications are only recently coming to the foreground of investigative attention (22, 23). Most published studies on this subject lack sufficient length of followup and only involved women (24). Our results are in agreement with prior observational studies inasmuch as assortative mating by body mass is exceedingly common and overweight and obese women tend to marry or cohabit with men of similar weight (25, 26). We have also provided clear evidence for the utility of routinely collecting data on male partners participating in infertility trials treating their female partners (15, 16).

Current smoking for both females and males was independently associated with a lower likelihood of live birth. This observation warrants further attention as smoking is alarmingly common among PCOS women seeking pregnancy (27), and is associated with increased free T and worsening insulin resistance (28). Detrimental effect of smoking on fetal health is well established. Despite the known harmful effects of smoking, over 20% of all U.S. women are estimated to smoke cigarettes in the 3 months prior to pregnancy (29). The full cohort of the PPCOS II trial exhibited a 15% prevalence of smoking in this population of infertile women who actively sought fertility care and have been overall compliant with treatment (17). In the current report, we present novel data indicating that smoking is often reported by both partners seeking fertility care and decreases success of treatment. This suggests that there may be additive effects if both partners smoke, possibly due to the combination of self-smoking and second-hand smoke exposure on ovulation, conception, and live birth (30). When effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions in couples was studied, several reports suggest that outcomes correlate with concordance of successful cessation for both partners (31–33). This paradigm has not been adequately studied in the preconception setting and may represent a missed opportunity in patients who are overall highly motivated (34).

We demonstrated a detrimental effect of male but not female age in the final model. We propose the reason why the female age in the adjusted model did not have a significant effect is that women with PCOS experience a slower decline in ovarian reserve than other women (35), and may also experience improved spontaneous ovulation rates with age (36). Likewise, serum androgens frequently normalize (37). Thus, women with PCOS may have improved fertility as they get older and their follicular reserve approaches the norm at younger ages (38).

It is noteworthy that PPCOS II couples reporting more frequent intercourse at baseline had a greater chance of success of fertility treatment. Strikingly, this effect remained highly significant after adjusting for potential confounders in the multivariable analyses. Reduced exposure to sexual encounters either by decreased likelihood of finding a partner or by rare sexual intercourse has been proposed as a potential reason to explain the association of female obesity with subfertility. Although published reports on frequency of sexual intercourse among obese women have yielded conflicting results (39), most large studies demonstrated no differences in frequency of sexual activity by BMI (40). Similarly, a report of 626 women from the PPCOS I study found no difference in intercourse compliance by body mass (41). Although it is beyond the scope of the present report to examine the reasons for the association between higher intercourse frequency at baseline and success of fertility treatment, this behooves attention for counseling of infertile couples.

Our study is limited by an incomplete ability to evaluate the potential effect of semen analysis on success of treatment. However, by design we only recruited couples who consented to regular intercourse without insemination. Sperm motility was not a collected variable. The protocol required a male partner with a sperm concentration of at least 14 million per milliliter, with documented motility in at least one ejaculate during the previous year. Previous data from this network (42) demonstrated a considerable overlap between fertile and infertile men within both the subfertile and the fertile ranges for concentration, motility, and morphology. Therefore, we elected not to specify a lower limit for either motility or morphology for our inclusion and exclusion criteria. A major strength of our study is that we are able to assess the effect of male factors on the ultimate yardstick of childbearing potential, ie, live birth. This is a secondary analysis which may be potentially subject to spurious findings due to multiplicity of analyses. However, the magnitude of our findings is important and certainly deserves attention. Another limitation is related to the fact that only some lifestyle behaviors have been evaluated in male partners whereas physical activity, dietary habits and sleep were beyond the scope of the current report.

In sum, in this large cohort of obese women with PCOS, the effect of male obesity was explained by female BMI. Couples in which both partners were current smokers had a lower take-home baby rate. Obesity and smoking, potentially modifiable risks, are highly prevalent among women with PCOS and their partners and negatively effect success of fertility treatment. Low intercourse frequency as a potential factor influencing success of fertility treatment may be underappreciated by patients and practitioners alike and warrants consideration. Overall, our findings could be regarded as hypothesis generating: could including male partners in studies of lifestyle modifications for obese and smoking women result in improved outcomes? Dedicated prospective studies are needed to answer this question.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in RMN. In addition to the authors, other members of the NICHD Reproductive Medicine Network were as follows: Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey: C. Bartlebaugh, W. Dodson, S. Estes, C. Gnatuk, R Ladda, J. Ober; University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio: C. Easton, A. Hernandez, M. Leija, D. Pierce, R Bryzski; Wayne State University: A. Awonuga, L. Cedo, A. Cline, K. Collins, E. Puscheck, M. Singh, M. Yoscovits; University of Pennsylvania: K. Barnhart, K. Lecks, L. Martino, R. Marunich, P. Snyder; University of Colorado: A. Comfort, M. Crow; University of Vermont: A. Hohmann, S. Mallette; University of Michigan: M. Ringbloom, J. Tang; University of Alabama Birmingham: S. Mason; Carolinas Medical Center: N. DiMaria; Virginia Commonwealth University: M. Rhea; Stanford University Medical Center: K. Turner; University of Virginia: D. J. Haisenleder; SUNY Upstate Medical University: J. C. Trussell; Yale University: D. DelBasso, Y. Li, R. Makuch, P. Patrizio, L. Sakai, L. Scahill, H. Taylor, T. Thomas, S. Tsang, M. Zhang; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: C. Lamar, L. DePaolo; Advisory Board: D. Guzick (Chair), A. Herring, J. Bruce Redmond, M. Thomas, P. Turek, J. Wactawski-Wende; Data and Safety Monitoring Committee: R. Rebar (Chair), P. Cato, V. Dukic, V. Lewis, P. Schlegel, F. Witter.

This work was supported by the Eunice Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. U10-HD27049 (to C.C.), U10 HD38992 (to R.S.L.), U10HD055925 (to H.Z.), U10 HD39005 (to M.P.D.), U10 HD055936 (to G.M.C.), U10 HD33172, U10 HD38998 (to R.A.), and U10 HD055944 (to P.R.C.); and U54-HD29834 (to the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: G.M.C.: Advisory board, Bayer Pharmaceuticals; Consultant and invited speaker, Abbvie Pharmaceuticals; Research Grant Support from Bayer and Abbvie Pharmaceuticals. W.D.S.: Sponsored research by AbbVie Pharmaceuticals. C.C.: Medical Advisory Board of NORA Therapeutics. M.P.D.: Board Member, Advanced Reproductive Care; Consultant, Halt Medical, Genzyme, Auxogyn, Actamax, and ZSX Medical; Investigator, Abbvie, Novartis, Boeringher Ingelheim, Ferring, EMD Serono, and Biosante. J.T.: Stock owner, Pfizer, Inc, Merck & Co, Astellas, and Johnson & Johnson. N.S.: Advisory group member, Menogenix; Principal investigator, Bayer, Inc. H.Z.: Ad-hoc consultant, Sun Yat-Sen University, Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Tsinghua University, and Shangdong University. R.S.L.: Speaker, Ferring Pharmaceuticals. A.J.P., A.A.A., P.R.C., R.A., S.A.K., E.E., and R.M.N. have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BMI

- body mass index

- CI

- confidence interval

- ED

- erectile dysfunction

- IIEF

- International Index of Erectile Function

- OR

- odds ratio

- PCOS

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- PPCOS II

- Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome II

- SHIM

- Sexual Health Inventory of Men.

References

- 1. Lake JK, Power C, Cole TJ. Women's reproductive health: The role of body mass index in early and adult life. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Polotsky AJ, Hailpern SM, Skurnick JH, Lo JC, Sternfeld B, Santoro N. Association of adolescent obesity and lifetime nulliparity—The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2004–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Metwally M, Saravelos SH, Ledger WL, Li TC. Body mass index and risk of miscarriage in women with recurrent miscarriage. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stothard KJ, Tennant PW, Bell R, Rankin J. Maternal overweight and obesity and the risk of congenital anomalies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:636–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith GC, Shah I, Pell JP, Crossley JA, Dobbie R. Maternal obesity in early pregnancy and risk of spontaneous and elective preterm deliveries: A retrospective cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:157–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cnattingius S, Villamor E, Johansson S, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA. 2013;309:2362–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chu SY, Kim SY, Lau J, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth: A metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heerwagen MJ, Miller MR, Barbour LA, Friedman JE. Maternal obesity and fetal metabolic programming: A fertile epigenetic soil. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R711–R722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sallmén M, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA, Blair A, Baird DD. Reduced fertility among overweight and obese Men. Epidemiology. 2006;17:520–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nguyen RH, Wilcox AJ, Skjaerven R, Baird DD. Men's body mass index and infertility. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2488–2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramlau-Hansen CH, Thulstrup AM, Nohr EA, Bonde JP, Sørensen TI, Olsen J. Subfecundity in overweight and obese couples. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1634–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pauli EM, Legro RS, Demers LM, Kunselman AR, Dodson WC, Lee PA. Diminished paternity and gonadal function with increasing obesity in men. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:346–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keltz J, Zapantis A, Jindal SK, Lieman HJ, Santoro N, Polotsky AJ. Overweight Men: Clinical pregnancy after ART is decreased in IVF but not in ICSI cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27:539–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Petersen GL, Schmidt L, Pinborg A, Kamper-Jørgensen M. The influence of female and male body mass index on live births after assisted reproductive technology treatment: A nationwide register-based cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1654–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Improving the Reporting of Clinical Trials of Infertility Treatments (IMPRINT). Modifying the CONSORT statement. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:952–959 e915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Legro RS, Wu X, Barnhart KT, Farquhar C, Fauser BC, Mol B. Improving the reporting of clinical trials of infertility treatments (IMPRINT): modifying the CONSORT statement†‡. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:2075–2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Legro RS, Brzyski RG, Diamond MP, et al. The Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome II study: Baseline characteristics and effects of obesity from a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:258–269.e258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Legro RS, Brzyski RG, Diamond MP, et al. Letrozole versus Clomiphene for Infertility in the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:119–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cappelleri J, Rosen RC. The Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM): A 5-year review of research and clinical experience. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:307–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Slonim DK. From patterns to pathways: Gene expression data analysis comes of age. Nat Genet. 2002;32(Suppl):502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mutsaerts MA, Groen H, ter Bogt NC, et al. The LIFESTYLE study: Costs and effects of a structured lifestyle program in overweight and obese subfertile women to reduce the need for fertility treatment and improve reproductive outcome. A randomised controlled trial. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Norman RJ, Noakes M, Wu R, Davies MJ, Moran L, Wang JX. Improving reproductive performance in overweight/obese women with effective weight management. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10:267–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Anderson K, Norman RJ, Middleton P. Preconception lifestyle advice for people with subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;14:CD008189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Speakman JR, Djafarian K, Stewart J, Jackson DM. Assortative mating for obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Silventoinen K, Kaprio J, Lahelma E, Viken RJ, Rose RJ. Assortative mating by body height and BMI: Finnish twins and their spouses. Am J Hum Biol. 2003;15:620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Legro RS, Myers ER, Barnhart HX, et al. The Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Study: Baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort including racial effects. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:914–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cupisti S, Häberle L, Dittrich R, et al. Smoking is associated with increased free testosterone and fasting insulin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, resulting in aggravated insulin resistance. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:673–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pregnancy Risk. Assessment Monitoring System US, 40 Sites, 2000–2010. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6206a1.htm?s_cid=ss6206a1_e [PubMed]

- 30. US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease; Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health 2006;709. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Palmer CA, Baucom DH, McBride CM. 2000. Couple approaches to smoking cessation. In: Schmaling KB, ed. The psychology of couples and illness: Theory, research, & practice. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dollar KM, Homish GG, Kozlowski LT, Leonard KE. Spousal and alcohol-related predictors of smoking cessation: A longitudinal study in a community sample of married couples. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McBride CM, Curry SJ, Grothaus LC, Nelson JC, Lando H, Pirie PL. Partner smoking status and pregnant smoker's perceptions of support for and likelihood of smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1998;17:63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hughes EG, Lamont DA, Beecroft ML, Wilson DM, Brennan BG, Rice SC. Randomized trial of a “stage-of-change” oriented smoking cessation intervention in infertile and pregnant women. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hudecova M, Holte J, Olovsson M, Sundström Poromaa I. Long-term follow-up of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: Reproductive outcome and ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:1176–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Elting MW, Korsen TJ, Rekers-Mombarg LT, Schoemaker J. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome gain regular menstrual cycles when ageing. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Winters SJ, Talbott E, Guzick DS, Zborowski J, McHugh KP. Serum testosterone levels decrease in middle age in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:724–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rausch ME, Legro RS, Barnhart HX, et al. Predictors of pregnancy in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3458–3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arenton LW. Factors in the sexual satisfaction of obese women in relationships. Electron J Hum Sexuality. 2002;5. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kaneshiro B, Jensen JT, Carlson NE, Harvey SM, Nichols MD, Edelman AB. Body mass index and sexual behavior. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:586–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pagidas K, Carson SA, McGovern PG, et al. Body mass index and intercourse compliance. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1447–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Guzick DS, Overstreet JW, Factor-Litvak P, et al. Sperm morphology, motility, and concentration in fertile and infertile men. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1388–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]