Abstract

Alternative splicing events from tandem donor sites result in mRNA variants coding for additional amino acids in the DNA binding domain of both the glucocorticoid (GR) and mineralocorticoid (MR) receptors. We now show that expression of both splice variants is extensively conserved in mammalian species, providing strong evidence for their functional significance. An exception to the conservation of the MR tandem splice site (an A at position +5 of the MR+12 donor site in the mouse) was predicted to decrease U1 small nuclear RNA binding. In accord with this prediction, we were unable to detect the MR+12 variant in this species. The one exception to the conservation of the GR tandem splice site, an A at position +3 of the platypus GRγ donor site that was predicted to enhance binding of U1 snRNA, was unexpectedly associated with decreased expression of the variant from the endogenous gene as well as a minigene. An intronic pyrimidine motif present in both GR and MR genes was found to be critical for usage of the downstream donor site, and overexpression of TIA1/TIAL1 RNA binding proteins, which are known to bind such motifs, led to a marked increase in the proportion of GRγ and MR+12. These results provide striking evidence for conservation of a complex splicing mechanism that involves processes other than stochastic spliceosome binding and identify a mechanism that would allow regulation of variant expression.

The glucocorticoid (GR) and mineralocorticoid (MR) receptors are thought to be descended from an ancestral fish corticoid receptor that underwent gene duplication some 450 million years ago. Elegant studies (1) suggest that the duplicated genes were originally capable of binding both glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids, but with time the GR evolved to become specific for glucocorticoids. The common evolutionary history of corticosteroid receptors is apparent in their conserved structure which, like other nuclear receptors, incorporates specific domains allocated to functions such as ligand binding, activation of transcription, and DNA binding (2). The DNA binding domain, which is particularly highly conserved in all nuclear receptors, consists of two zinc fingers separated by a short loop. Each zinc finger, together with part of the intervening loop, is encoded by a separate exon (exons 3 and 4, separated by intron C). Two closely related genes, probably derived from a genome duplication that occurred at some time after the divergence of fish and tetrapod lineages, code for the GR in fish (3). Alternative splicing of one of these genes produces an isoform, first identified in rainbow trout (4, 5) and later reported in cichlid fish (6), with an additional nine amino acids encoded by 27 bases inserted between exons 3 and 4 (Fig. 1). The source of this variant, which has since been detected almost universally in fish species (7), is alternative splicing of an additional short exon located within intron C (8).

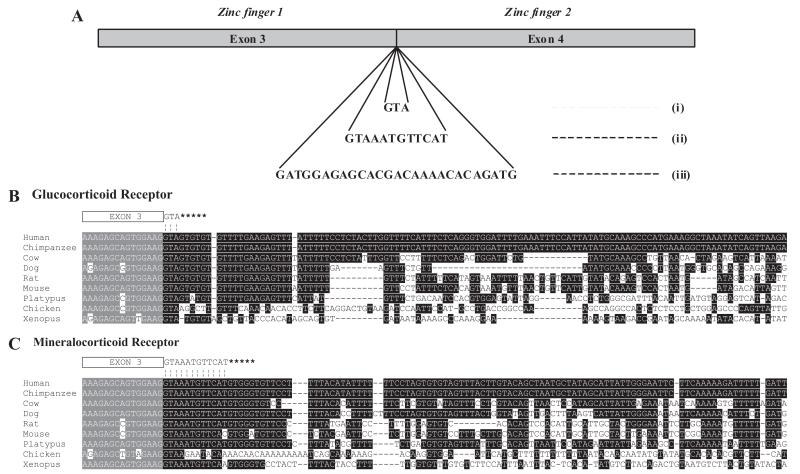

FIG. 1.

Corticosteroid receptor splice variants. A, The additional sequences introduced by alternative splicing at the exon 3/exon 4 boundary of mammalian glucocorticoid receptors (i), mammalian mineralocorticoid receptors (ii), and fish glucocorticoid receptors (iii). Genomic sequences at the exon 3/intron C junction of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (B) and the mineralocorticoid receptor gene (C) are shown. Asterisks indicate potential downstream alternative splice sites. Sequences were aligned using CLUSTAL W 2.0 multiple sequence alignment.

Alternative splicing at the corresponding exon 3/exon 4 junction, but produced by a different mechanism, has been detected in the GR and MR of tetrapods. When first reported, the GR sequence of a New World monkey (Saguinus Oedipus) included an additional three bases located in the DNA binding domain (9). The same sequence was subsequently reported in mouse (10) and human (11) tumors. We found the identical variant in normal human tissues and showed that it accounts for a significant proportion (3.8-8.7%) of total glucocorticoid receptor mRNA (12). On the basis of the known GR gene structure (13), we proposed that alternative splicing from tandem 5′ donor sites produces two variants, the predominant GRα form and an additional variant, which we named GRγ, resulting from retention of the first three bases (GTA) of the intron. Thus, an additional amino acid (arginine) is inserted in the loop joining the two zinc fingers of the DNA binding domain of GRγ (Fig. 1). Recently Meijsing et al. (14) identified important functional differences between GRγ and GRα. For transcriptional regulation of some genes, GRγ is less active, but for a subset of genes, the variant proves to be markedly more active than GRα. A similar splicing variant (MR+12) of the MR has been reported in human (15, 16), rat (15), and xenopus (17). Again, an alternative splice site is located in the intron separating exons 3 and 4 of the MR gene, but in this case, 12 bases of the intron are retained, coding for an additional four amino acids, KCSW in humans and rats (Fig. 1), KCSR in xenopus. The results presented here show that both GR and MR variants are widely conserved in mammals and provide strong additional evidence in support of a functional role for both variants.

Alternative splicing of pre-mRNA increases protein diversity, enhancing proteome size considerably and providing a significant source for the increased complexity of regulatory networks in higher organisms (18). It is unclear, however, to what extent the production of splice variants might result from errors in the splicing process. The class of alternative splicing that involves tandem 3′ and 5′ splice sites has been shown to be used extensively (19), but it has been suggested that such alternative splicing could simply represent noise caused by slipping of the spliceosome between the two sites in a stochastic process (20). The present study provides convincing evidence to refute this argument by demonstrating the essential role played by conserved intronic sequences. In addition, the TIA1 and TIAL1 proteins, which are known to facilitate recognition of 5′ donor sites, are shown to be capable of regulating the relative usage of the tandem donor sites.

Materials and Methods

Detection of splice variants

Using RT-PCR, a region spanning the exon 3/4 splice site was amplified from hepatic RNA obtained from each species. Total RNA was extracted from tissues preserved in RNAlater (Ambion, Abingdon, UK) using the RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN, Crawley, UK) and reverse transcribed using the cloned AMV first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). All oligonucleotides used are given in supplemental Fig. S1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org.

Amplified PCR products were cloned using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The retained three bases in the human GRγ sequence create an AccI restriction site, and the same insertion would generate this restriction site in the other mammalian species we investigated. Putative GRγ clones were therefore identified using restriction analysis before sequencing. The platypus MR+12 variant clones were identified by excising the cloned PCR products and separation by gel electrophoresis. All sequencing was performed by Geneservice (Cambridge, UK).

Quantitation of variant mRNA expression

Expression of GRγ in mouse tissues was measured by AccI digestion as described previously (12) using the MTC panel (BD Biosciences, CLONTECH, Palo Alto, CA). Fragments were stained with Vistra Green (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) and fluorescence quantitated with a Molecular Dynamics Storm phosphorimager (Amersham Biosciences). Quantitative PCR was performed using the ABI 7500 real-time PCR sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) with the SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). Primers used for GR quantitation were based on those described by Beger et al. (21). Representative standard curves for quantitative PCR assays are shown in supplemental Figs. 2 and 3. For rat tissues, the MTC rat panel (CLONTECH) was used.

Construction of minigenes

The MR minigene was constructed by two rounds of PCR amplification of the MR gene from rat genomic DNA (Bioline, Randolph, MA) using primers MR1-4 and proofreading DNA polymerase (PfuUltra; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Two separate regions of the MR gene were amplified, exon 3 with 300 bp downstream intronic sequence (primers MR1 and MR2) and 300 bp intronic sequence upstream of exon 4 together with exon 4 (primers MR3 and MR4). Primers MR2 and MR3 had 3′ sequence complementarity, allowing a second round of PCR amplification of both exons and intronic sequences before cloning into the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen). The GR minigene was constructed in the same manner, using primers GR1-4 to amplify regions of the glucocorticoid receptor from human genomic DNA.

Single-base modifications were introduced using QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). Deletion plasmids were constructed by two rounds of PCR amplification from the complete GR minigene and recloning into the pcDNA3 vector using appropriate pairs of primers. The intronic mutations in the MR minigene plasmids (CTTT to GGAG) and GR minigene plasmids (TTTT to CAGA) were constructed in the same way.

Transfection and Western blotting

COS-1 and A549 cells (both obtained from ECACC, Salisbury, UK) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mm l-glutamine. Cells (175,000 cells/well in six well plates) were seeded 24 h before transfection, and each well was transfected with 0.8 μg plasmid combined with 4 μl Lipofectamine-2000 (Invitrogen). The cells were harvested 24 h after transfection, and RNA was extracted using an RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN). Expression vectors for hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged short isoforms of human TIA1 and TIAL1 subcloned into pMT2 were generously supplied by H. Lou (Department of Genetics, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH) and N. Kedersha (Division of Rheumatology, Immunology, and Allergy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA). For small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of TIA1 and TIAL1, ON-TARGET SMARTpools L-013042-00-0005 and L-011405-00-0005 (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) were used. For Western blotting, cells were lysed as described (22). TIA1 and TIAL1 were detected using Ab H-120 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and HA tag was detected using Ab 16B12 (Cambridge BioScience, Cambridge, UK).

Scoring of 5′ splice sites

Shapiro and Senapathy (S&S) and Maxent 5′ splice site scores were computed using online tools (http://ast.bioinfo.tau.ac.il/splicesiteframe.htm and http://genes.mit.edu/burgelab/maxent/xmaxentscan_scoreseq.html).

Results

Evolutionary conservation of 5′ splice sites at the exon 3/exon 4 junction of the GR gene

The consensus sequence for 5′ splice sites is CAG/GTRAGT (where / denotes the exon/intron junction and R represents purine) (23). The bases, which are conventionally designated −3 to −1 for the last three exonic bases and +1 to +6 for the first six intronic bases, allow for exact complementarity with the consensus sequence of the U1 small nuclear (snRNA) 5′ terminus, although individual splice sites may differ substantially from the consensus sequence. To assess the degree of evolutionary conservation of the GRγ variant, we first examined genomic sequences at the exon 3/intron C boundary of the GR gene in various species (Fig. 1B). In all mammalian species examined, a potential additional splice site with the consensus GT dinucleotide is present at positions +4 and +5 of the GRα donor site. This base pair is absent in chicken, xenopus, and fish sequences, however. Various methods have been used to assess the strength of putative splice sites.

To provide an initial estimate of the likelihood that tandem donor sites would direct splicing of both GRα and GRγ variants, we used a method based on nucleotide frequency matrices (S&S score) derived by Shapiro and Senapathy (24), which reflects the degree of conservation of individual nucleotides relative to the consensus sequence. With the exception of platypus, in all other mammalian species examined, the 5′ splice sites that would give rise to GRα and GRγ have scores of 72 and 62%, respectively (the maximum score for a consensus sequence being 100%). These figures suggest that expression of the two variants is maintained by use of a relatively weak α-site together with a slightly weaker γ-site. The one exception is the platypus sequence, in which the presence of an A instead of G at position +3 of the putative GRγ donor site, which should strengthen the site (score 66%). The presence of this sequence in platypus suggests that GRγ arose at a very early stage in the evolution of mammals; two recent estimates for the time elapsed since human and platypus lineages diverged have been 166 (25) and more than 200 (26) million years ago.

There is also a particularly striking conservation that extends further to include a T-rich sequence (53% of the 30 bases downstream from the human GRγ donor site). Previous studies have shown increased conservation of intronic sequences linked to alternatively spliced exons (27, 28), suggesting that these sequences might be important for alternative splicing. More recently Aznarez et al. (29) have identified U-rich sequences in precursor mRNA as important determinants of 5′ donor site choice, suggesting that the T-rich intronic sequence might play a role in choice of splice site. Another putative regulatory sequence, TATGCA, that has been shown to function as an exon splicing regulatory sequence (30) is located 77 bases downstream from the GRα splice site of the human GR.

Evolutionary conservation of 5′ splice sites at the exon 3/exon 4 junction of the MR gene

Examination of corresponding intron sequences for the MR gene also indicates conservation of the alternative MR+12 splice site in mammals (Fig. 1C). Predicted S&S scores for MR and MR+12 in most mammals are 87.9 and 72.4%, respectively, with the alternative MR+12 splice site again being the weaker of the two sites. One interesting exception is the mouse sequence, in which there is a high degree of conservation, except that one base (A at +5 of a possible MR+12 splice donor site) replaces the G found in other mammals. As a result, the score for this alternative site is decreased to 59.8%. In Xenopus, despite some differences relative to mammalian genes, the score for the MR+12 donor site (73.0%) is similar to that in mammals. There is no evidence of an alternative splice site in the chicken.

Again, there is conservation in the 30 bases downstream from the 5′ splice site. Like the GR gene, this sequence is T-rich (53% of the 30 bases downstream from the human MR+12 donor site).

Expression and quantitation of the GRγ splice variant in different species

To confirm the predicted expression of GRγ mRNA, we tested for the presence of mRNA encoding GRγ in liver samples from various species. Sequences spanning the GR exon 3/exon 4 junction were amplified by PCR, cloned, and then screened by digestion with the AccI restriction enzyme. The presence of the additional GTA triplet in an AccI-positive clone from each species was confirmed by sequencing, and the species identity of each sequence was confirmed by comparison with published sequences. Previously we identified GRγ in various human tissues, including liver (12). We have now confirmed the expression of GRγ in a wide range of mammals including pig, rabbit, rat, mouse, and platypus (results not shown). As predicted from the intron sequences that lack appropriate alternative 5′ splice sites (Fig. 1C), we detected no GRγ mRNA in chicken or Xenopus.

GRγ expression was measured in mouse tissues using the Acc1 digestion assay (12). The results were similar to those found previously in human tissues, ranging between 6.1 and 8.4% of total GR mRNA, with a mean of 7.1 ± 1.0% (Table 1). We then established a quantitative PCR assay for rat and platypus GRγ mRNA. With this assay, we obtained similar, although slightly higher, levels of GRγ mRNA ranging from 7.4 to 10.6% in rat tissues (Table 1), with a mean of 9.0 ± 1.2%. Unexpectedly, despite the higher score for the putative downstream donor site, we found a significantly lower level (3.5% of total GR mRNA) of the variant in platypus liver compared with rat liver (P < 0.01).

TABLE 1.

Expression of GRγ and MR+12 mRNA in different species

| Mouse | Rat | Platypus | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRγ variant (percent GR mRNA) | |||

| Liver | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 8.6 ± 1.1 | 3.5 ± 0.6 |

| Spleen | 8.4 ± 1.4 | 9.1 ± 1.9 | |

| Skeletal muscle | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | |

| Heart | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 9.8 ± 1.0 | |

| Kidney | 6.4 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 1.2 | |

| Lung | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 9.8 ± 0.5 | |

| Brain | 6.9 ± 0.8 | 10.6 ± 1.9 | |

| MR+12 variant (percent MR mRNA) | |||

| Liver | <0.01 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | |

| Spleen | <0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | |

| Skeletal muscle | <0.5 | 2.7 ± 1.0 | |

| Heart | <0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | |

| Kidney | <0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | |

| Lung | <0.1 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | |

| Brain | <0.1 | 3.5 ± 1.5 |

Results represent the mean and sd from at least three separate experiments. The GRγ variant was measured by Acc1 digestion in mouse tissues and quantitative PCR in rat tissues. The MR+12 variant was measured by quantitative PCR in mouse and rat tissues.

Quantitation of MR+12 mRNA variant expression in rat and mouse tissues

The MR+12 splice variant has been described previously in rat and human (15) as well as xenopus (17) tissues. Using quantitative PCR, we found expression of MR+12 mRNA to range between 2.0 and 4.0% of total receptor mRNA in rat tissues (mean 3.0 ± 0.7) (Table 1). We were interested to measure MR+12 expression in the mouse because the predicted strength of the donor site for this variant was markedly lower than in other mammals. In agreement with this prediction, we were unable to detect MR+12 in mouse tissues using quantitative PCR (Table 1). The presence of MR+12 in platypus liver was confirmed, however, by sequencing the region spanning the 5′ splice site in a clone selected on the basis of size (results not shown).

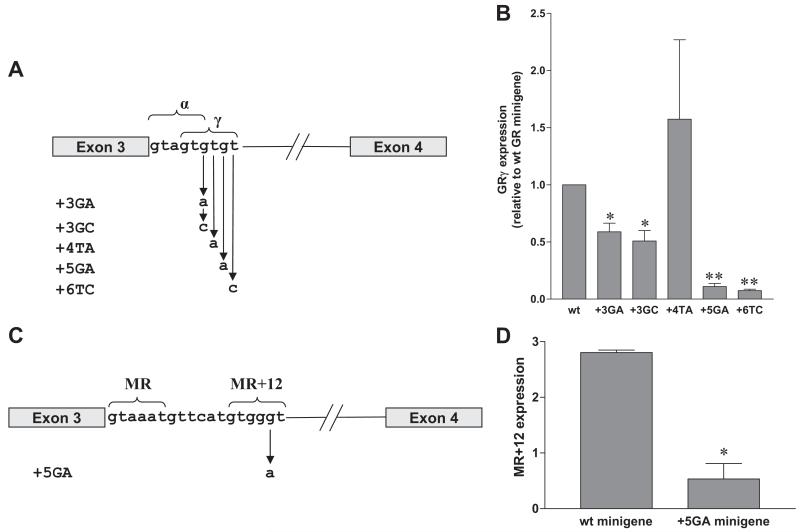

Alternative splicing in minigenes with point mutations in donor sites

Minigenes to allow further analysis of GR and MR alternative splicing were constructed that consisted of exons 3 and 4 of each gene together with about 300 bases from the 5′ and 3′ ends of the intron. To investigate the importance of individual bases in the tandem 5′ donor sites of the GR gene, mutations were introduced at sites +3 to +6 of the GRγ donor (Fig. 2A), and the effect of these changes on the ratio of α- and γ-splice variants was determined in COS-1 cells. With the wild-type minigene, the GRγ splice variant was produced at a consistently lower level than GRα, ranging between 17 and 37% of total transcripts in individual experiments. None of the mutations had any significant effect on production of GRα (results not shown), but mutations at +5 and +6 resulted in a marked decrease in splicing to the GRγ variant (Fig. 2B), as predicted by lower S&S scores for these mutations (50 and 56%, compared with 62% for the wild type sequence). A higher S&S score (72%) for the mutation at +4 (T to A) also appeared to result in increased formation of the GRγ variant, although the difference was not statistically significant. Importantly, the effect of the +3 G-to-A mutation confirms the anomalous finding with the platypus receptor, i.e. an A at position +3 would be expected to increase base pairing to U1 snRNA, as reflected in the S&S score but in practice decreases usage of this donor site.

FIG. 2.

Alternative splicing in COS-1 cells produced by minigenes with point mutations. A, GR minigene constructs used, showing point mutations introduced into the GRγ 5′ donor site. B, Expression of GRγ by mutants relative to expression from wild-type minigene. C, MR minigene constructs used, showing +5 G to A mutation introduced into the rat MR+12 donor site. D, Expression of MR+12 by minigene constructs. wt, Wild-type. Results show mean and sem from three or more separate experiments. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001.

With the MR minigene, 2.8% of total transcript consisted of MR+12 variant. In agreement with the absence of MR+12 in mouse tissue, mutation of the rat MR minigene G at +5 to A (Fig. 2C), as found in the mouse genome, drastically reduced the proportion of MR+12 variant to just 19% of that produced by the wild-type minigene (Fig. 2D).

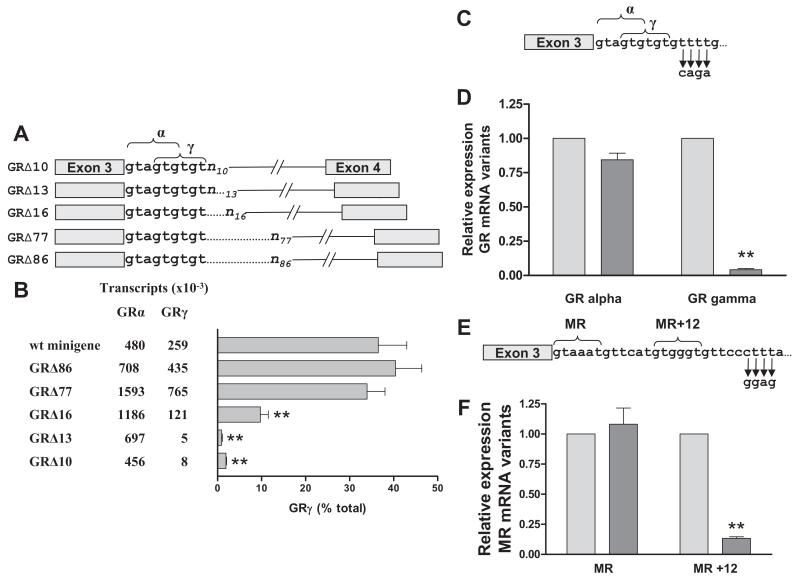

Alternative splicing in minigenes with deleted intronic sequences

Progressive deletions of the 5′ intron sequence (Fig. 3A) were then introduced into the GR wild-type minigene. The Δ86 minigene still included the TATGCA hexamer putative regulatory sequence (at +77), but the hexamer was deleted from the Δ77 minigene. The Δ10 minigene retained only 10 bases (i.e. the nine bases encompassing the GRα and GRγ splice sites, plus one additional base from the downstream intron). The Δ13 and Δ16 minigene sequences contained the GRα and GRγ splice sites plus four and seven bases of the downstream intron, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Alternative splicing in COS-1 cells produced by GR and MR minigenes with intronic mutations. A, GR minigene constructs with intronic deletions. n, number of bases downstream from the alpha splice site that are included in the minigene. B, Absolute (mean number of transcripts × 10−3 from three experiments) and relative expression of GRα and GRγ variants by different minigene constructs. The number of transcripts in cells transfected with empty vector was negligible. C, Mutations introduced (TTTT to CAGA) into pyrimidine motif of GR intron. D, Relative expression of human GRα and GRγ from wild-type (light grey) and mutated (dark grey) minigenes. E, Mutations introduced (CTTT to GGAG) into pyrimidine motif of MR intron. F, Relative expression of rat MR and MR+12 from wild-type (light grey) and mutated (dark grey) minigenes. α and γ refer to 5′ donor sequences utilized for splicing to form GRα and GRγ mRNA sequences respectively. Results show mean and sem from three or more separate experiments. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test. **, P < 0.001.

Deletion of intronic sequences to create the Δ86 and Δ77 minigenes resulted in an increase (P < 0.05) in the number of both GRα and GRγ transcripts (Fig. 3B), suggesting that these sequences, and particularly the TATGCA hexanucleotide, exert repressor functions. Further deletions to create Δ16, Δ13 and Δ10 minigenes resulted in a decrease (P < 0.05) in both products, a finding that is compatible with previous studies showing that T-rich intronic sequences enhance usage of adjacent upstream 5′ donor sites (29).

The most striking effect of intronic deletions was on the proportion of GRγ variant produced (Fig. 3B). There was no significant change in the relative amount of GRγ produced by the Δ86 and Δ77 minigenes (i.e. up to and including the TATGCA sequence), but deletion of the T-rich intronic sequence caused a drastic reduction in the proportion of GRγ. A small amount (10% of total) of GRγ was produced by the Δ16 minigene, which still included the TTTT sequence just downstream from the GRγ donor site, but further deletion resulted in almost complete loss of the GRγ variant (to 0.9 and 1.9%, respectively, in the Δ10 and Δ13 minigenes). Thus the T-rich intronic sequence not only enhances usage of 5′ donor sites but may be essential for usage of weaker downstream donors at tandem sites.

Alternative splicing in minigenes with point mutations in an intronic pyrimidine motif

The experiments with GR deletion mutants showed that the extended T-rich intronic sequence plays a major role in directing the spliceosome to the downstream donor. Because these experiments also suggested that the first pyrimidine tetranucleotide motif located immediately downstream from the donors might be particularly important, we decided to test the effect of mutating this motif in the GR and MR minigenes. In both human genes, the motif is TTTT (Fig. 3C), but in the wild-type rat MR minigene, it is CTTT (Fig. 3E). Mutation of these motifs resulted in almost complete suppression of both human GRγ (Fig. 3D) and rat MR+12 (Fig. 3F) variants, without significantly affecting expression of the variant lacking an insert.

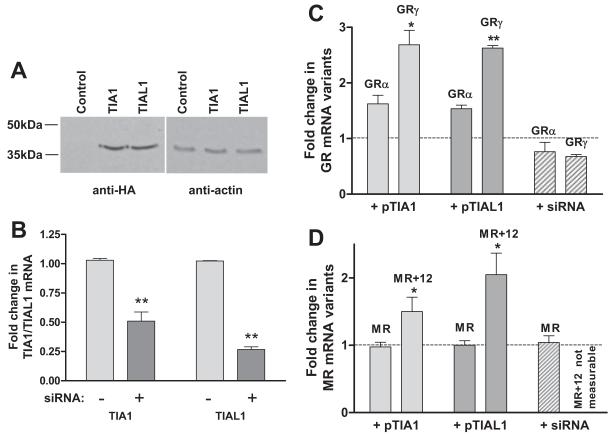

TIA1 and TIAL1 regulate alternative splicing of endogenous corticosteroid receptor genes

In view of their affinity for U-rich motifs and effect on choice of 5′ donors, TIA1 and TIAL1 proteins were expressed in A549 cells (Fig. 4A) and the proportion of variants expressed by endogenous genes was measured. There was a clear increase in the relative proportion of both GRγ (Fig. 4C) and MR+12 (Fig. 4D). Decreasing both TIA1 and TIAL1 by siRNA (Fig. 4B) resulted in a clear decrease in GRγ, whereas a small decrease in GRα was not significant (Fig. 4C). Knockdown of TIA1 and TIAL1 had no obvious effect on MR-12, whereas expression of MR+12 became too low to measure. These results clearly show that TIA1/TIAL1 proteins enhance usage of downstream splice sites in both genes. A small increase in GRα (P < 0.05) when these proteins were overexpressed suggests that they might also stabilize GR mRNA.

FIG. 4.

Effects of TIA1/TIAL1 proteins on alternative splicing by GR and MR minigenes. A, Western blot using anti-HA antibody to confirm production of TIA1 and TIAL1 proteins together with anti α-actin antibody control. B, Quantitative PCR showing knockdown by siRNA of TIA1 and TIAL1 mRNA (normalized to β-actin mRNA). C, Expression of GRα and GRγ (relative to cells transfected with empty plasmid or RNA) in A549 cells transfected with plasmids expressing TIA1, TIAL1, or siRNA against TIA1 and TIAL1. D, Relative expression of MR and MR+12 (relative to cells transfected with empty plasmid or RNA) in A549 cells transfected with plasmids expressing TIA1, TIAL1, or siRNA against TIA1 and TIAL1. Results show mean and sem from three or more separate experiments. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test. *, P < 0.05, GRγ vs. GRα in cells expressing TIA1, or MR+12 vs. MR in cells expressing TIA1 or TIAL1; **, P < 0.001, GRγ vs. GRα in cells expressing TIAL1.

Discussion

Several instances of alternative splicing have been described in the GR and MR receptors that result in insertion of additional amino acids in the short loop joining the two zinc fingers of the DNA binding domain. We have expanded these observations to show a high degree of evolutionary conservation for both the GRγ and MR+12 splice variants, which extends at least to the platypus, a species belonging to a lineage that is thought to have diverged from other mammals 166 million yr ago or more (25). There was no evidence for the GRγ variant in reptiles or birds, but MR+12 has been reported in xenopus (17), as would be predicted by the presence of an alternative 5′ splice site in the xenopus MR intron sequence (Fig. 1C). One exception for the MR+12 variant is its almost complete absence in the mouse, which we predicted on the basis of a single base change in the alternative splice site of the mouse genomic sequence.

In an extensive study of the human genome, Hiller et al. (31) identified 8550 tandem donor sites with the GYNGYN motif (where Y = C or T, N = A, C, G, or T). Of these, there was evidence of alternative splicing at 110 (1.3%) donors that used both GY splice sites. It has been suggested that such alternative splicing could simply represent noise caused by slipping of the spliceosome between the two sites in a stochastic process (20). The alternative splicing that occurs from tandem splice sites in the Wilms’ Tumor 1 (WT1) gene (32) provides a clear example of functional importance for tandem splice sites, however. Two isoforms that differ by the presence (+KTS) or absence (−KTS) of three amino acids, also located in a linker region between two zinc fingers, are produced by the WT1 gene (32, 33), and severe developmental defects result from changes in the ratio of these isoforms (34-36).

Complementarity to the U1 snRNA seems to be the dominant parameter in determining the extent of alternative splicing for two 5′ splice sites, which are predicted to have strong affinity for splicing factors (37). Although predicted binding for the alternative splice sites of the GR is less strong, the effects of point mutations in the donor sequence giving rise to GRγ generally confirm the importance of U1 binding. With the MR minigene, the G at position +5 in the MR+12 donor is particularly important, as shown by the apparent absence of MR+12 in the mouse and by the minigene experiment shown in Fig. 2D. Interestingly, the GRβ splice variant, which lacks the C-terminal domain (38), is also absent in the mouse (39). Evidence for the existence of determining factors other than simple strength of U1 binding in this system is provided by the decreased formation of GRγ when G is substituted by A at +3 in the 5′ donor of the GR minigene and in the platypus, which was predicted to increase complementarity to U1. This unexpected finding is in accord with a number of studies showing that splice site choice cannot be predicted simply on the basis of complementarity to splicing factors.

In general, compared with introns flanking constitutively spliced exons, those surrounding alternatively spliced exons tend to be better conserved, with about 80% conservation for the first 30 bases of the downstream intron (27). In comparison, the first 30 bases of intron C of the glucocorticoid receptor gene show a remarkable 97% conservation between human, rat, and mouse. A putative regulatory TATGCA sequence was identified 68 bases downstream from the tandem donor sites of the GR gene, and experiments with GR minigene deletion constructs provided some evidence for a suppressive effect of this hexanucleotide on overall splicing. The most striking result obtained with the minigene constructs related to deletion of the T-rich intronic sequence located between the tandem donor sites and the TATGCA motif. Several studies identified T-rich intronic sequences that regulate exon inclusion or exclusion (40-42), and a recent genome-wide study found widespread involvement of U-rich sequences in 5′ splice site recognition (29).

To identify the sequence responsible for this effect more precisely, the first pyrimidine tetramers downstream from the tandem donors in GR and MR minigenes were mutated. The consequence of these mutations was a drastic reduction in expression of both GRγ and MR+12 variants (Fig. 3, D and F). These experiments clearly show that choice of tandem donors is not simply a stochastic process determined by complementarity of the two splice donors to U1 snRNA and clearly refute the suggestion that alternative splicing at these tandem donor sites simply represents noise in the splicing process. Apart from the point mutations, the minigenes used for these experiments were identical with the wild-type minigenes, thus confirming that the decreased expression of GRγ in deletion mutants (Fig. 3B) was not simply a result of either reduced intronic sequence or proximity of the deletion site to the U1 binding sequences. Also, the conservation of intronic motifs required for expression of the GRγ and MR+12 variants provides additional evidence supporting their functional importance. Interestingly, while this manuscript was in preparation, a pyrimidine-rich intronic enhancer, which is required for production of the +KTS variant of WT1 was identified (43).

Cytotoxic granule-associated RNA binding protein (TIA1) and the related TIAL1 are multifunctional proteins involved in regulating splicing and mRNA stability. They bind U-rich sequences and have been shown to facilitate recognition of 5′ splice sites (29). In the present study, we show that this property extends to tandem donor sites, in which they markedly enhance usage of the downstream site (Fig. 4). The TIA1 and TIAL1 proteins are known to interact with other splicing regulators to determine tissue-specific expression of splicing variants (44), providing a mechanism whereby expression of the corticosteroid receptor variants could be regulated.

Comparing GRγ expression in a small number of rat and mouse tissues (Table 1), we found a relatively constant ratio of expression, with the variant constituting about 7–9% of total GR mRNA [similar to the level we found previously in human tissues (12)]. Other studies indicated a degree of tissue-specific regulation, however. In particular, there is evidence for an association between altered levels of GRγ expression and responsiveness to glucocorticoids in leukemic patients (21, 45, 46), a finding that could be explained by the regulatory factors that we have identified. With regard to the MR+12 variant, we found that it constituted between 2 and 4% of total MR receptor mRNA in the tissues studied, although Wickert et al. (47) detected variable expression of MR+12 in different regions of the brain.

Assuming that GRγ and MR+12 each play a distinct functional role in mammals, it is clearly important to identify the cellular processes that are controlled by each variant. Previous studies have shown that GRγ is less efficient than GRα at transactivation from a simple reporter gene containing glucocorticoid response elements (10, 11). Our more recent studies (paper to be submitted) show that with certain promoters GRγ may be more potent than GRα. These findings have now been confirmed by Meijsing et al. (14), who propose that the conformation of a short lever arm that is sensitive to differences in the sequence of DNA binding sites can mediate allosteric changes in receptor conformation and function, so allowing differential regulation of specific target genes. Importantly, the additional arginine in GRγ is located within this lever arm and is shown to alter its conformation. Distinct properties of the variants may also be linked to the dual function of the DNA binding domain, which mediates important protein/protein interactions (48-50) in addition to DNA binding. Insertion of arginine in GRγ could be of particular significance because this amino acid appears to have an important role in providing binding sites for protein/protein interactions, perhaps because it can form the basis for complex salt bridges linking more than two amino acids (51), and it is one of the three amino acids found most frequently in binding hot spots at protein-protein interfaces (52).

The results presented here show that the bases in the tandem 5′ donor sites of the GR and MR genes are crucial for determining the ratio of splice variants produced but not sufficient. These alternative splicing events have been conserved in mammalian genomes over a considerable evolutionary period, possibly exceeding 200 million years, thus providing strong evidence in support of a functional role for the variants. Importantly, we have also identified conserved intronic sequences that play a crucial role in selection of GR and MR donor sites, and the ability of TIA1/TIAL1 proteins to modify the ratio of variant mRNA produced indicates the existence of a regulatory mechanism that may be of general relevance to splicing at tandem donor sites in other genes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Platypus RNA was a generous gift from Frank Grützner (School of Molecular and Biomedical Science, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia).

This work was supported by funding from the Wellcome Trust, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research, Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, and the Neuroendocrinology Charitable Trust.

Abbreviations

- GR

Glucocorticoid receptor

- HA

hemagglutinin

- MR

mineralocorticoid receptor

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- snRNA

small nuclear RNA

- S&S

Shapiro and Senapathy

- WT1

Wilms’ Tumor 1

Footnotes

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Thornton JW. Evolution of vertebrate steroid receptors from an ancestral estrogen receptor by ligand exploitation and serial genome expansions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5671–5676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091553298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedges SB, Kumar S. Genomics. Vertebrate genomes compared. Science. 2002;297:1283–1285. doi: 10.1126/science.1076231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ducouret B, Tujague M, Ashraf J, Mouchel N, Servel N, Valotaire Y, Thompson EB. Cloning of a teleost fish glucocorticoid receptor shows that it contains a deoxyribonucleic acid-binding domain different from that of mammals. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3774–3783. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.9.7649084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeo J, Hata J, Segawa C, Toyohara H, Yamashita S. Fish glucocorticoid receptor with splicing variants in the DNA binding domain. FEBS Lett. 1996;389:244–248. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00596-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwood AK, Butler PC, White RB, DeMarco U, Pearce D, Fernald RD. Multiple corticosteroid receptors in a teleost fish: distinct sequences, expression patterns, and transcriptional activities. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4226–4236. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stolte EH, van Kemenade BM, Savelkoul HF, Flik G. Evolution of glucocorticoid receptors with different glucocorticoid sensitivity. J Endocrinol. 2006;190:17–28. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lethimonier C, Tujague M, Kern L, Ducouret B. Peptide insertion in the DNA-binding domain of fish glucocorticoid receptor is encoded by an additional exon and confers particular functional properties. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;194:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandon DD, Markwick AJ, Flores M, Dixon K, Albertson BD, Loriaux DL. Genetic variation of the glucocorticoid receptor from a steroid-resistant primate. J Mol Endocrinol. 1991;7:89–96. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0070089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasai Y. Two naturally occurring isoforms and their expression of a glucocorticoid receptor gene from an androgen-dependent mouse tumor. FEBS Lett. 1990;274:99–102. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81339-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ray DW, Davis JR, White A, Clark AJ. Glucocorticoid receptor structure and function in glucocorticoid-resistant small cell lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Research. 1996;56:3276–3280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivers C, Levy A, Hancock J, Lightman S, Norman M. Insertion of an amino acid in the DNA-binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor as a result of alternative splicing. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4283–4286. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.11.6235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Encío IJ, Detera-Wadleigh SD. The genomic structure of the human glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7182–7188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meijsing SH, Pufall MA, So AY, Bates DL, Chen L, Yamamoto KR. DNA binding site sequence directs glucocorticoid receptor structure and activity. Science. 2009;324:407–410. doi: 10.1126/science.1164265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloem LJ, Guo C, Pratt JH. Identification of a splice variant of the rat and human mineralocorticoid receptor genes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;55:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00162-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wickert L, Watzka M, Bolkenius U, Bidlingmaier F, Ludwig M. Mineralocorticoid receptor splice variants in different human tissues. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;138:702–704. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1380702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Csikós T, Tay J, Danielsen M. Expression of the Xenopus laevis mineralocorticoid receptor during metamorphosis. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1995;50:393–396. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571150-0.50026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maniatis T, Reed R. An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature. 2002;416:499–506. doi: 10.1038/416499a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiller M, Platzer M. Widespread and subtle: alternative splicing at short-distance tandem sites. Trends Genet. 2008;24:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chern TM, van Nimwegen E, Kai C, Kawai J, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Zavolan M. A simple physical model predicts small exon length variations. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e45. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beger C, Gerdes K, Lauten M, Tissing WJ, Fernandez-Munoz I, Schrappe M, Welte K. Expression and structural analysis of glucocorticoid receptor isoformγ in human leukaemia cells using an isoform-specific real-time polymerase chain reaction approach. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:245–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hislop JN, Everest HM, Flynn A, Harding T, Uney JB, Troskie BE, Millar RP, McArdle CA. Differential internalization of mammalian and non-mammalian gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors. Uncoupling of dynamin-dependent internalization from mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39685–39694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horowitz DS, Krainer AR. Mechanisms for selecting 5′ splice sites in mammalian pre-mRNA splicing. Trends Genet. 1994;10:100–106. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro MB, Senapathy P. RNA splice junctions of different classes of eukaryotes: sequence statistics and functional implications in gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:7155–7174. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.17.7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bininda-Emonds OR, Cardillo M, Jones KE, MacPhee RD, Beck RM, Grenyer R, Price SA, Vos RA, Gittleman JL, Purvis A. The delayed rise of present-day mammals. Nature. 2007;446:507–512. doi: 10.1038/nature05634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Rheede T, Bastiaans T, Boone DN, Hedges SB, de Jong WW, Madsen O. The platypus is in its place: nuclear genes and indels confirm the sister group relation of monotremes and Therians. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:587–597. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorek R, Ast G. Intronic sequences flanking alternatively spliced exons are conserved between human and mouse. Genome Res. 2003;13:1631–1637. doi: 10.1101/gr.1208803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hare MP, Palumbi SR. High intron sequence conservation across three mammalian orders suggests functional constraints. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:969–978. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aznarez I, Barash Y, Shai O, He D, Zielenski J, Tsui LC, Parkinson J, Frey B, Rommens JM, Blencowe B. A systematic analysis of intronic sequences downstream of 5′ splice sites reveals a widespread role for U-rich motifs and TIA1/TIAL1 proteins in alternative splicing regulation. Genome Res. 2008;18:1247–1258. doi: 10.1101/gr.073155.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goren A, Ram O, Amit M, Keren H, Lev-Maor G, Vig I, Pupko T, Ast G. Comparative analysis identifies exonic splicing regulatory sequences—the complex definition of enhancers and silencers. Mol Cell. 2006;22:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiller M, Huse K, Szafranski K, Rosenstiel P, Schreiber S, Backofen R, Platzer M. Phylogenetically widespread alternative splicing at unusual GYNGYN donors. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R65. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-7-r65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hastie ND. Life, sex, and WT1 isoforms—three amino acids can make all the difference. Cell. 2001;106:391–394. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00469-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner KD, Wagner N, Schedl A. The complex life of WT1. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1653–1658. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klamt B, Koziell A, Poulat F, Wieacker P, Scambler P, Berta P, Gessler M. Frasier syndrome is caused by defective alternative splicing of WT1 leading to an altered ratio of WT1 +/− KTS splice isoforms. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:709–714. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barbaux S, Niaudet P, Gubler MC, Grünfeld JP, Jaubert F, Kuttenn F, Fékété CN, Souleyreau-Therville N, Thibaud E, Fellous M, McElreavey K. Donor splice-site mutations in WT1 are responsible for Frasier syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17:467–470. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hammes A, Guo JK, Lutsch G, Leheste JR, Landrock D, Ziegler U, Gubler MC, Schedl A. Two splice variants of the Wilms’ tumor 1 gene have distinct functions during sex determination and nephron formation. Cell. 2001;106:319–329. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00453-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roca X, Sachidanandam R, Krainer AR. Determinants of the inherent strength of human 5′ splice sites. RNA. 2005;11:683–698. doi: 10.1261/rna.2040605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oakley RH, Sar M, Cidlowski JA. The human glucocorticoid receptor β isoform. Expression, biochemical properties, and putative function. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9550–9559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otto C, Reichardt HM, Schütz G. Absence of glucocorticoid receptor-β in mice. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26665–26668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Guiner C, Lejeune F, Galiana D, Kister L, Breathnach R, Stévenin J, Del Gatto-Konczak F. TIA-1 and TIAR activate splicing of alternative exons with weak 5′ splice sites followed by a U-rich stretch on their own pre-mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40638–40646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shukla S, Dirksen WP, Joyce KM, Le Guiner-Blanvillain C, Breathnach R, Fisher SA. TIA proteins are necessary but not sufficient for the tissue-specific splicing of the myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13668–13676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuccato E, Buratti E, Stuani C, Baralle FE, Pagani F. An intronic polypyrimidine-rich element downstream of the donor site modulates cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator exon 9 alternative splicing. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16980–16988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang C, Romaniuk PJ. The ratio of +/− KTS splice variants of the Wilms’ tumour suppressor protein WT1 mRNA is determined by an intronic enhancer. Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;86:312–321. doi: 10.1139/o08-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu H, Hinman MN, Hasman RA, Mehta P, Lou H. Regulation of neuron-specific alternative splicing of neurofibromatosis type 1 pre-mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1240–1251. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01509-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lauten M, Fernandez-Munoz I, Gerdes K, von NN, Welte K, Schlegelberger B, Schrappe M, Beger C. Kinetics of the in vivo expression of glucocorticoid receptor splice variants during prednisone treatment in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;52:459–463. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haarman EG, Kaspers GJ, Pieters R, Rottier MM, Veerman AJ. Glucocorticoid receptor α, β and γ expression vs in vitro glucocorticoid resistance in childhood leukemia. Leukemia. 2004;18:530–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wickert L, Selbig J, Watzka M, Stoffel-Wagner B, Schramm J, Bidlingmaier F, Ludwig M. Differential mRNA expression of the two mineralocorticoid receptor splice variants within the human brain: structure analysis of their different DNA binding domains. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:867–873. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.König H, Ponta H, Rahmsdorf HJ, Herrlich P. Interference between pathway-specific transcription factors: glucocorticoids antagonize phorbol ester-induced AP-1 activity without altering AP-1 site occupation in vivo. EMBO J. 1992;11:2241–2246. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nissen RM, Yamamoto KR. The glucocorticoid receptor inhibits NFκB by interfering with serine-2 phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2314–2329. doi: 10.1101/gad.827900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang JM, Préfontaine GG, Lemieux ME, Pope L, Akimenko MA, Haché RJ. Developmental effects of ectopic expression of the glucocorticoid receptor DNA binding domain are alleviated by an amino acid substitution that interferes with homeodomain binding. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7106–7122. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Musafia B, Buchner V, Arad D. Complex salt bridges in proteins: statistical analysis of structure and function. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:761–770. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bogan AA, Thorn KS. Anatomy of hot spots in protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:1–9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.