Abstract

The ultimate goal of epilepsy therapies is to provide seizure control for all patients while eliminating side effects. Improved specificity of intervention through on-demand approaches may overcome many of the limitations of current intervention strategies. This article reviews progress in seizure prediction and detection, potential new therapies to provide improved specificity, and devices to achieve these ends. Specifically, we discuss 1) potential signal modalities and algorithms for seizure detection and prediction, 2) closed-loop intervention approaches, and 3) hardware for implementing these algorithms and interventions. Seizure prediction and therapies maximize efficacy while minimizing side-effects through improved specificity may represent the future of epilepsy treatments.

1 Introduction

Epilepsy affects nearly 3 million people in the US, with nearly 500 new cases of epilepsy diagnosed every day (Hauser et al. 1993; Murray and Lopez 1994). Current anti epileptic drugs can have major negative side effects, and approximately ⅓ of patients with epilepsy are drug refractory (Kwan et al. 2010). Of those, only patients with a well localized focus in an area outside of the eloquent cortex are good surgical candidates. For the remaining patients there are few remaining options. Closed-loop therapies may provide new intervention options, improving seizure control while reducing or eliminating side effects by limiting the therapy to times when the patient is in need. Closed-loop seizure therapies may also allow for stronger therapy doses that cannot be delivered chronically. The development of on-demand approaches will require effective seizure prediction or early detection algorithms and optimized intervention strategies, while being reliable and safe for chronic implantation in humans. This article discusses both the progress as well as the future directions for each of these areas.

1.1 The need for new seizure detection and prediction devices

While many therapeutic devices have been developed for epilepsy, few devices have made it to clinical trials. There is a need for robust and accurate seizure detection and prediction devices. Self-reporting by patients of their seizures is often poor when compared to detection of electrographic events, in part because consciousness may be affected by the seizure. A monitoring device could therefore dramatically improve assessment of therapy both in treating patients and in clinical trials. Furthermore, a device that could detect changes in physiology prior to a seizure and deliver therapies to prevent the seizure would be transformative, enabling new approaches to treating epilepsy.

1.2 Defining seizure prediction

Seizure prediction has had a long and storied history and has been well reviewed elsewhere (Iasemidis 2003; Litt and Lehnertz 2002; Mormann et al. 2007). A significant advance for the field came with simply defining “seizure prediction”. Prediction is defined as identifying an event after which a seizure will occur within a fixed period of time. In contrast, if a heightened risk of seizure occurring is identified without a specific time window; it is considered “seizure forecasting”. Four key criteria to measure the efficacy of a seizure prediction algorithm have been proposed: 1) developing algorithms on long-term recordings from patients, 2) assessing sensitivity and specificity with respect to a range of prediction horizon times and the portion of time under false warning, 3) proving that the algorithm can perform above chance level by using statistical techniques, and 4) testing the algorithm on out-of sample data (Mormann et al. 2007).

1.3 Future of seizure therapy: Closing the loop

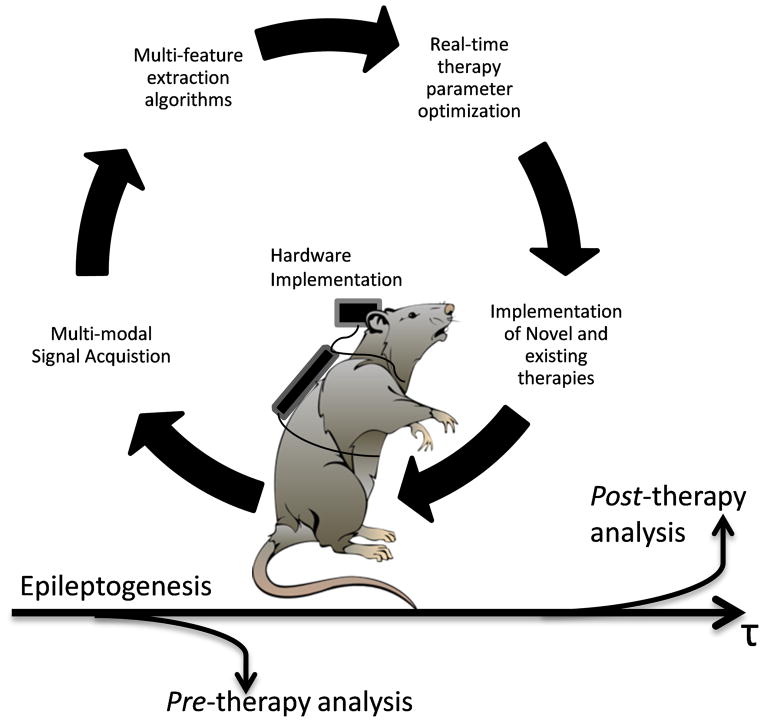

As noted above, a monitoring device that can deliver closed-loop treatment enables new approaches to develop more personalized therapies. There are important considerations at all phases in developing a closed-loop treatment: 1) the signals to be measured, 2) the features to be extracted and classification algorithms, 3) optimization of treatment, 4) the therapeutic actions to be taken, and 5) the devices to implement closed-loop therapies. These steps form a therapeutic loop, illustrated in Figure 1. While seizure prediction and closed-loop therapies may be the ultimate goal, there are benefits to be gained in developing each phase of this loop. The development of closed-loop therapies may also help elucidate the effects of intervention on underlying biological processes. This review outlines the current state and discusses potential future directions of seizure prediction and closed-loop therapies.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical closed-loop experimental protocol for suppressing seizures using multimodal recordings of physiological activity. From the recordings, features are extracted and a classifier is applied to detect seizure activity, or a pre-seizure state for prediction. Upon detection of an event, the device triggers a therapy.

2 Pre-ictal and ictal detection

Over the last two decades a number of seizure prediction algorithms using EEG with different features, classifiers, hardware, and intervention therapies have been developed and tested. Only a few have surpassed sensitivity and specificity of chance predictors. In this section we will discuss the need for new recording modalities, classification algorithms and assessment of outcomes.

2.1 Signal modalities

Scalp electroencephalography (EEG), and electrocorticography (ECoG), measured at the surface of the brain, have been the mainstays for seizure prediction since the 1970’s (Viglione and Walsh 1975). The use of linear (Rogowski et al. 1981) and non-linear methods (Iasemidis et al. 1990) helped conceptualize the ‘“pre-ictal” state as a period in which the brain exhibits an increasing prevalence of seizure like behavior prior to seizure onset. However, it is questionable whether these signals contain sufficient information for accurate seizure prediction. Other recording methods, such as penetrating microelectrodes, which provide higher spatial resolution and wider spectral content, may be necessary to better characterize the neural activity at the focus. Simultaneous macro and micro electrode recordings have revealed microbursts of activity that are not seen by the macro-electrodes alone (Schevon et al. 2010; Schevon et al. 2009; Stead et al. 2010; Truccolo et al. 2011; Viventi et al. 2011). Applying these microbursts as an additional feature set could potentially increase predictive power. Furthermore, single unit recordings may provide additional features for improved seizure prediction (Bower and Buckmaster 2008; Bower et al. 2012; Einevoll et al. 2012; Keller et al. 2010).

Beyond passive recording techniques, important information may be gained through evoked potentials. Single electrical pulses may be used to detect changes in excitability prior to a seizure. Changes in excitability over space may also be used to localize a seizure focus. Excitatory synaptic activity can increase in epileptic tissue (Avoli et al. 2005) through a variety of mechanisms including potentiation of synaptic AMPA receptors (Abegg et al. 2004; Debanne et al. 2006; Lopantsev et al. 2009; Müller et al. 2013), potentiation of extra synaptic NMDA receptors (Frasca et al. 2011; Müller et al. 2013), and an increase of intrinsic excitability of neurons (Tang et al. 2012). Importantly, a single pulse may evoke different epileptic responses depending on the level of excitability (Demont-Guignard et al. 2012). For example, an electrical brain-stimulation paradigm was successfully used for estimating both the seizure onset sites and the time to ictal transition in human temporal lobe epilepsy (Kalitzin et al. 2005). Evoked potentials may therefore be valuable for closed-loop stimulation protocols and optimization of stimulation parameters (Kent and Grill 2012; McIntyre et al. 2004).

Additionally, improved seizure prediction may be achieved using other recording modalities. Several physiological changes have been observed preceding electrographic seizure onset; in animal models and humans, changes in blood flow, blood oxygenation, and metabolism have all been shown to precede a seizure (Patel et al. 2013; Schwartz 2007; Zhao et al. 2011). Additionally, in humans, electrochemical studies have shown distinct glutamate and adenosine dynamics associated with seizures (During and Spencer 1992; 1993; Van Gompel et al. 2014). Heart-rate monitors and accelerometers have also been used to extract salient biomarkers of seizures (Lockman et al. 2011; Nijsen et al. 2005; Zijlmans et al. 2002). Incorporation of these other modalities with EEG may significantly improve seizure prediction and intervention.

2.2 Databases of epileptiform data

Comparative analysis of seizure prediction algorithms across different data sets is critical to evaluate their performance. In response to the identification of this need at the Bonn International Seizure Prediction Workshop, the Freiburg database was developed and made widely available (Winterhalder et al. 2003), and eventually the larger Epilepsiae database (http://epilepsy-database.eu/) and the International Epilepsy Electrophysiology (IEEG) Portal (https://www.ieeg.org/). Open access to EEG databases has encouraged scientists outside of the epilepsy field to get involved in developing new algorithms and has been beneficial to the health of the field.

2.2.1 Competitions

To encourage direct comparison of algorithms, there have been several public competitions affiliated with the International Seizure Prediction Workshop in which common datasets are provided and algorithms must be provided for final judgment. These competitions have been crucial in identifying physiological markers that are useful in seizure prediction and assessing the performance of algorithms. The purpose of these competitions is to encourage the development of new algorithms with the hope that a successful algorithm may be implemented in a clinical setting one day. However, the assessment of the algorithms often requires that the code be made available to the judges, which prevents some groups from participating because it can decrease the licensing value of the algorithm. Thus, there is a need for the development of a method to test the algorithms in a competition while preserving their licensing integrity.

2.2.2 Limitations and future approaches

There are however, several limitations to the usefulness of these databases. Firstly, the maintenance of these databases and coordination of the competitions involve significant costs. The Epilepsiae database has implemented a payment system, and while the IEEG database remains free, sustaining it in the future may require collaboration with an entity such as the National Library of Medicine to house and maintain the data.

Second, the usefulness of public epilepsy databases crucially depends on the continued contribution of data from various sources. This is particularly important for newer modalities such as those based on changes in blood flow (Harris et al., 2014) and neurotransmitter concentration (Van Gompel et al., 2014) during seizures, which are not currently represented in the Epilepsiae and IEEG-Portal databases. One concern that may limit contribution to public databases is that individual contributors are not recognized in future uses of the data when all of the data is combined into one source and references generally cite the entire database. Therefore, to encourage continued contribution to such databases, we must develop a standard of citing data sources in order to also credit original sources.

Lastly, another limitation of public epilepsy databases is that they only contain recordings collected in the clinical setting, and thus any conclusions drawn from this data may not translate to more natural contexts. Several trials have already begun which involve gathering chronic recordings from patients outside of the clinic (Cook et al. 2013). Incorporation of these recordings into current public databases is the next step. One approach to accessing this data is through appealing to the patient population. Many patients support the use of their data for research purposes, and participants in clinical trials hold significant power in determining what may be done with their data. Without jeopardizing company assets, patients involved in the clinical trial can lobby to make de-identified data publicly available within a reasonable time frame upon completion of the study. Support for an organized movement of patients should be developed to ensure that data recorded in a long-term ambulatory setting is made available to the wider scientific community.

2.3 Features

While many features extracted from EEG signals have been used for seizure prediction (Mormann et al. 2007), no single, or univariate measure, has successfully characterized a pre-seizure state with high sensitivity and specificity. Individual features may have some small predictive power; however, as an aggregate, the feature set may achieve stronger predictive power. For example, changes in EEG at the focus may only be understood in the context of patterns seen in surrounding areas. Therefore, seizure prediction may benefit from a multivariate approach.

A drawback to a multivariate approach, however, is that the relationship between the measured features and the predictions may be complex and unintuitive. It may therefore be difficult for clinicians to correlate changes in the raw signal with abstract features extracted through signal processing techniques. Similarly, classification of multivariate data for seizure prediction can be an engineering black box approach that provides limited insight to the mechanisms underlying the seizure onset. An alternative approach is to fit physiologically realistic models to the data. The parameters of the model can then be used as the feature set (as discussed in section 2.3.2). This may provide better insight into the relationship between mechanisms, such as changes in connection strengths between nodes, and state changes, such as pre-ictal to ictal.

Another challenge of a multivariate approach is that it is easy to produce an immense parameter space that cannot be fully explored. This is problematic for a number of reasons. First, a larger dimensional space can allow classifiers to over-fit the data in training, resulting in poor classification on new data. Second, as the number of features increases, the computational load does as well. Therefore when developing seizure prediction algorithms the processing power of implantable devices should be considered.

There are two approaches that can be used to reduce feature space. One approach is to limit the number of measurement and features to those that actually provide some predictive power, for example, by using an ROC analysis or Fisher Discriminant Analysis to select features. The other is to combine features in a way to reduce computational load, such as principal component analysis. Managing computational load is an important aspect of implementing seizure prediction and detection on implantable devices that needs to be developed further.

2.3.1 Linear vs. Nonlinear features

Linear features, such as mean, standard deviation, and power spectral density, are well understood. However, there may be physiological signals that cannot be well characterized by linear features. With the advent of chaos theory, many new measures were developed to analyze nonlinear systems, such the Lyapunov Exponent, and the fractal dimension of the data. Presumably these measures can detect changes that are undetectable using linear measures. However, in head-to-head comparisons, linear features often outperform the nonlinear ones in detecting a pre-ictal state (Jerger et al. 2003; Mormann et al. 2005). This is because linear features are extremely robust to noise (Netoff et al. 2004b). Clearly, nonlinear measures may have great value for seizure prediction (Iasemidis 2003) and should not be ignored; however, they must be compared in performance and computational costs to linear measures. Furthermore, for implementation in an implantable device, linear features may be the only option due to current computational constraints.

2.3.2 Computational models for feature extraction

Computational modeling provides an efficient way to understand complex neuronal systems and bridge multiple scales to connect cellular behaviors to macroscopic EEG measurements (Holt and Netoff 2013). Computational models have several roles in seizure prediction and the field of epilepsy more broadly (Soltesz and Staley 2011; Wendling et al. 2012). These include generating hypotheses and predicting mechanisms (including mechanisms of epileptogenesis and ictogenesis), analyzing and interpreting recorded signals and how they relate to the underlying systems, and aiding in the design and optimization of closed-loop therapies. In this section we will briefly discuss some of these different aspects of using computational models.

Biophysically realistic cellular models

Microscopic models characterize the dynamics of individual neurons or their components. Early computational studies of networks of neurons were used to explain how population bursts arise in the CA3 region of the hippocampus (Traub and Wong 1983) and how gamma oscillations emerge in the cortex (Traub et al. 1996). Cellular models have been used to describe how mechanisms underlying fast-ripple (high frequency oscillations between 250–500Hz), epileptic spikes, and seizures, correspond to common electrophysiological signals (Demont-Guignard et al. 2009). These models provide a link between electrophysiogical signals and different degrees of excitability of glutamatergic cells and synchronization (Wendling et al. 2012).

In a recent study investigating the cellular mechanisms involved in the frequency dependent effect of deep brain stimulation (DBS), clinical, neurophysiological, and computational data were assembled in a thalamocortical model and effects of DBS were simulated (Mina et al. 2013). The results from this study makes predictions that 1) low-frequency stimulation activates feed-forward inhibition and causes short-term depression, 2) intermediate-frequency stimulation reinforces thalamic output leading to an increase of the average excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) on cortical pyramidal cells and to no “anti-epileptic” effect, and 3) high-frequency stimulation (HFS) leads to a dramatic decrease of TC cells firing rate and to a suppression of epileptic activity through the direct and sustained excitation of reticular nucleus (RtN) interneurons. This modeling demonstrates how computational models can be used to investigate effects of DBS.

Large scale biophysically realistic models

While there are benefits to simplified models, additional insights may be gained through the development of full scale, biologically realistic models which consolidate known information about diverse cell-types, firing properties, time delays, and connection strengths in neuronal networks (Case and Soltesz 2011; Morgan et al. 2007; Schneider et al. 2012). These models can then be used to determine how each parameter or a combination of parameters affects the network (Howard et al. 2007; Santhakumar et al. 2005). Such biologically realistic models which incorporate known changes seen in epilepsy can also be used to examine potential effects of cell-type selective interventions, thus identifying potential neuromodulation strategies which can in turn be tested in vivo.

Neural population modeling

Another approach to describing neuronal activity is to model the mass action of the population by lumping neurons together (Freeman 1973; Wilson and Cowan 1973). These are population firing rate-models. For example, a lumped-parameter model of the hippocampal CA1 subfield can be generated by modeling the firing rate of the three sub-populations of neurons: glutamatergic pyramidal cells and two types of local inhibitory interneurons (Molaee-Ardekani et al. 2010; Wendling et al. 2012; Wendling et al. 2005). Simple computational models like these can simulate oscillations (20–30 Hz) and spikes often observed at the seizure onset of TLE seizures (Jirsa et al. 2014), and have been used to investigate the critical role of inhibitory networks during the transition to seizures in the hippocampus. These models are computationally efficient and have few parameters compared to the detailed microscopic models. Because of their level of abstraction, they are often able to provide insight to how changes in cellular excitability or synaptic strengths effect systems level behaviors (Holt and Netoff 2013). Also, the relative simplicity of the model allows us to explore the entire parameter space to characterize all the system behaviors.

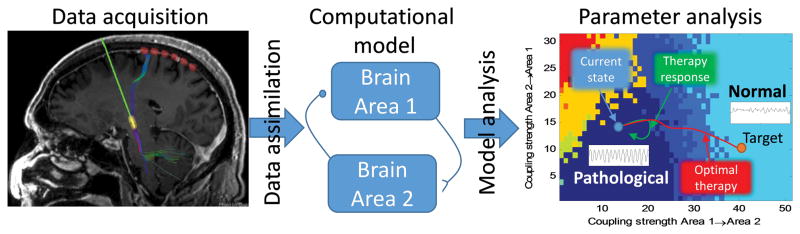

Feature extraction through model assimilation

Computational models can also be used to more directly identify signals of interest. That is, rather than extracting features directly from data, system identification tools can be employed. System identification fits a computation model to the measured signals of interest, and then uses the fit parameters to characterize the data (Schiff 2012). Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) is an example of such an approach (Friston et al. 2003). The model can be fit as data is collected through a process called data assimilation. An illustration of this process is shown in Figure 2. While data assimilation tools such as Bayesian inversion (Aarabi and He 2013), Unscented Kalman filters, and Particle filters (Simon 2006) have been used extensively in weather prediction, they have only been recently applied to nonlinear neural models (Voss et al. 2004). In order for the model to successfully fit the data, the model must be able to generate all the different observed patterns in the signals. Firing rate models are well suited to this kind of problem because of the diverse patterns of activity they can produce with only a few parameters (Robinson et al. 2002). The parameters can also be used to classify EEG data (Aarabi and He 2013; Freestone et al. 2013), and predict responses near state boundaries. Once these models are fit to the data, they can be applied in closed-loop control design.

Figure 2.

Classification of EEG with computational models. Depth EEG is collected (left panel). A model of EEG data (middle) is fit to the data through data assimilation. The parameter space of the model is explored to make a landscape that determines the different behaviors that the model can produce as a function of the parameters (right, different colors represent different patterns of activity). By fitting the model to the data using data assimilation tools, the current state of the neural activity can be estimated. By knowing how the current state relates to the parameter landscape of behaviors, it can be determined if the activity is approaching the boarder of pathological behavior and a systematic intervention can be planned.

2.4 Classifiers

In recent years, some algorithms for seizure prediction have reported high sensitivity and specificity with the use of powerful classifiers developed in the machine learning community (Park et al. 2011; Shoeb 2009). However, these findings have significant caveats: results were obtained on limited datasets, and prediction methods required high computational power. As mentioned in the previous section, there is a tradeoff between high computational costs of algorithms that perform with high sensitivity and specificity and the practicality of an algorithm that can be implemented in real time on an implantable device. While some implantable devices can perform simple signal processing and deliver reactive therapies (Heck et al. 2014; Stanslaski et al. 2012), there is a need to further develop computationally efficient algorithms and high-throughput/low power devices for real-time seizure prediction and detection for closed-loop therapies.

Powerful classifiers developed in a new field called “Deep-Learning” have been used extensively by companies such as Google, Amazon and Pandora for their recommendation algorithms (Bengio 2009). These methods may provide significant improvements over current algorithms, but have yet to be applied to seizure prediction and detection. These algorithms could be used for example as an advisory system by clinicians to screen patient’s EEG to classify pre-ictal and inter-ictal events and identify unclassifiable patterns.

Neurophysiological signals are nonstationary due to behavioral state changes on time scales ranging from minutes to seasons. Additionally, movement, immune reactions, and electrode deterioration can change the quality of the recordings. This nonstationary nature of neural signals can lead to an increased rate of classification errors. One solution is to develop adaptive classification algorithms that can not only compensate for a nonstationary signal but also detect trends in the nonstationarities to create predictive classifiers.

2.5 Assessing prediction outcomes

A true positive prediction of a seizure is defined as a window of time following an alarm in which a seizure must occur. Given this definition, it is possible to create a null-hypothesis. The simplest null hypothesis is that the predictions occur at random with an equal probability in each time window (Andrzejak et al. 2003). However, this null hypothesis is overly simplistic; it assumes seizure onsets are independent, but seizures often occur in clusters (Binnie et al. 1984). It has also been observed that it is more difficult to predict the sentinel seizure in a cluster (Howbert et al. 2014) and that the rates of seizure prediction for sentinel seizures may be reported separately. Therefore, an algorithm must outperform a random predictor by detecting patterns in the seizure times independently of the features extracted. Moving forward, a new standard for a null hypothesis must be developed that accounts for clustering of seizures.

An additional difficulty in assessing the performance of a seizure predictor lies in the definition of “pre-ictal” state and how to assess false positives. The operational definition is that a “pre-ictal” state occurs in the period of time immediately preceding a seizure. However, a patient may enter a pre-seizure-like state more often than they actually enter a seizure. Indeed, identification of a pre-seizure state presumes that some intervention can be applied to prevent the seizure, and that the seizure is not yet a foregone conclusion. Currently, if a seizure does not occur following detection of a pre-ictal state it is classified as a “false-positive”. Alternatively, the term “putative positive” may better emphasize that these events could in fact be potential pre-ictal states that did not manifest into seizures.

Ultimately, any algorithm must meet the needs of the clinicians and patients. Even in patients that have similar levels of false positives, or time under warning, satisfaction with device performance can differ significantly (Cook et al. 2013). Seizure prediction algorithms must have a parameter that enables the patient to adjust sensitivity and specificity to meet their needs.

Reducing the seizure rate with a therapy may be the primary goal, but the efficacy of a therapy goes beyond seizure rates and should be measured with improvement in quality of life as well. Indeed, some clinical trials for vagal nerve stimulation and DBS have shown significant improvement in quality of life measures greater than that expected by the modest decrease in seizure frequency (Heck et al. 2014; Morris et al. 2013). This suggests that the therapy may also have positive neuropsychiatric effects beyond seizure suppression. Calculation of the economy of quality of life which quantifies the costs and benefits of the therapies, side-effects, and financial burden on the overall outcome of the patient will aid in demonstrating and evaluating the benefits of interventions.

3 Intervention

In this section we will review the need for new stimulation targets and interventional therapies, such as optogenetics. We will also discuss methods for optimizing therapies using closed-loop approaches. Closed loop therapies may not only provide hope for patients, they may also provide critical insight into the mechanisms underlying ictogenesis and epileptogenesis, which may lead to new approaches to therapies.

3.1 Stimulation target selection

Two different approaches have been tried for target selection in recent clinical trials. One approach (conducted by Medtronic) was to target an area with wide neuromodulatory effects (Fisher et al. 2010): the superior anterior nucleus of the thalamus. The other was to stimulate the focus directly (Heck et al. 2014) led by NeuroPace. Surprisingly, in both cases there was about a 40% decrease in seizure frequency on average over a three month period. Even stimulation of the Vagus nerve has demonstrated approximately 30% decrease in seizure frequency in patients following a three month blind period (Handforth et al. 1998). Interestingly, the efficacy of stimulation from each of these studies increased at the end of a two year follow-up (Fisher et al. 2010; Heck et al. 2014; Morris et al. 2013). These long term effects indicate that there may be direct and indirect mechanisms on seizure suppression caused by the stimulation.

Animal experiments have also tested many other promising stimulation locations that have not yet been tested in full clinical trials, such as the subthalamic nucleus (Chabardès et al. 2002; Loddenkemper et al. 2001), medial temporal structures (Tellez-Zenteno et al. 2006; Velasco et al. 2007; Vonck et al. 2005), centromedian thalamic nuclei (Mina et al. 2013; Pasnicu et al. 2013), and hippocampal commissural fiber (Koubeissi et al. 2013; Toprani and Durand 2013) among others (Fisher 2013). On-demand electrical stimulation has also shown to be effective in suppressing seizures in animal models (Bikson et al., 2001; Schiller and Bankirer, 2007; Good et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 2011).

While many patients receive benefits, very few become seizure free. A single target may not be sufficient to control seizures. In some patients, seizures emerge from the interaction of multiple nodes within a network. Therefore, stimulation of more than one node in the network simultaneously may be required to improve seizure control. One approach to simultaneously modulate multiples nodes within a seizure network is to stimulate nuclei or fiber tracts that have widespread modulatory effects. Ideally, these targets would be far away from major blood vessels, to minimize risk during surgery, and have little effect on cognitive and motor functions.

3.3 Closed Loop intervention strategies

Different neurophysiological mechanisms are engaged by DBS depending on the stimulation localization, frequency, intensity, duration and pattern. As noted above, there is large clinical discrepancy in the efficacy between patients, especially if they suffer different subtype of epilepsies. It is difficult to tune stimulus parameters because the effect on seizure frequency cannot immediately be seen in the clinical setting. It may require statistical analysis over months to identify an effect of a stimulus parameter. Therefore new methods must be developed for the fine tuning of stimulation parameters in a patient-specific manner to maximize therapeutic effects.

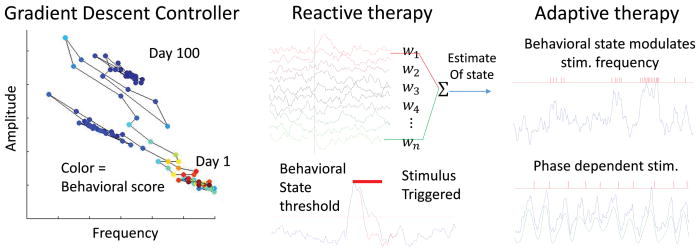

How can electrical stimulation be optimized for a patient? There are three approaches to closed-loop intervention, as illustrated in the figure 3: 1) A controller that slowly adapts stimulation parameters over time to maximize therapy (e.g. a gradient descent controller) (Panuccio et al. 2013), 2) On-demand therapy (Armstrong et al. 2013; Heck et al. 2014; Krook-Magnuson et al. 2013), 3) Physiologically adapting closed-loop neuromodulation (Little et al. 2013; Montaseri et al. 2013; Wilson et al. 2011).

Figure 3.

Types of closed loop controllers. Left, A Gradient Descent Controller adjusts parameters and measures effect, such as seizure frequency. Through small changes on a daily basis the algorithm can traverse a parameter landscape to find an optimal solution. In a Reactive Therapy, middle, signals are processed and when an event is detected in the estimated state of the patient. In this example a stereotyped stimulus is applied; however, statistical tools can be applied to optimize stimulus parameters for reactive therapy. In Adaptive therapy, right, the stimulus is modulated by the state of the patient or can be used to trigger phasic stimulation with millisecond precision.

Optimization of Stimulation Parameters

Optimization can be achieved by a gradient descent method (Figure 3, left) with offline analysis of data. This algorithm would establish a functional relationship between the parameters and the symptoms, and iteratively adjust the parameters of the therapy to improve the symptoms. Adaptive reinforcement learning algorithms are well-suited for problems with noisy, nonlinear, and nonstationary signals (Panuccio et al. 2013; Prokhorov and Wunsch 1997). This approach requires the algorithm to “learn” from its mistakes in order to descend upon a local solution.

One concern with implementing a closed loop algorithm is whether it is stable and safe. It is often more acceptable to implement a closed loop algorithm that essentially does the same, but more formally, as a clinician or the patient might do given a user interface. Optimization approaches like this have been tested in animal models with some success (Panuccio et al. 2013), but has yet to be used in a clinical trial. The first step towards obtaining Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for a closed-loop device is in an advisory role to the patient or clinician, who makes the parameter changes. With proven safety of the device in an advisory role, it then may be possible to implement a fully automatic version.

Closed-loop VNS optimization of stimulation parameters can be explored by controlling the activation of different vagus nerve fiber populations. An Autonomous Neural Control (ANC) algorithm has been developed to map stimulation parameters to nerve activation profiles (Ward et al. 2014). Given this map, the algorithm dynamically adjusts the stimulus to maintain the nerve activation at a therapeutic level over time. This closed-loop algorithm adjusts stimulus parameters to maintain a stable stimulus response over time.

On-demand stimulation

The reactive nerve stimulation by NeuroPace stemmed out of the closed-loop algorithms used in cardiac pace making. NeuroPace’s Responsive Neurostimulator delivers a stereotyped stimulus pattern when an abnormal event in the EEG is detected (Morrell 2006; Morrell and Group 2011). In clinical trials the stimulus parameters were set by the clinician. The device is closed-loop in that the stimulation is delivered on-demand (i.e., is a responsive stimulator), but it is limited to fixed stimulation parameters (Figure 3, middle). The success of the Responsive Neuro Stimulator (RNS) enables it to be a platform to test and implement new therapies. The RNS device could provide a platform to test optimization algorithms (such as those discussed above) to tune stimulus parameters to maximize effects, and could be coupled to other therapeutic modalities, such as micropumps for drug delivery or optogenetics. It also could provide a platform to test optimization algorithms to tune stimulus parameters to maximize effects.

Physiologically adapting closed-loop neuromodulation

Closed-loop neuromodulation generally uses fixed stimulus patterns and is not yet adapted to the patient. Therapeutic efficacy may be improved by providing therapy modulated by physiological activity of the patient. Closed-loop methods which adjust the timing of stimulation based on measured physiological activity (Ward et al. 2014) have been proposed for treatment of tremor, but have not yet been applied to epilepsy. This may be for several reasons, including that seizures are changing so rapidly that it is difficult to have a clear signal upon which to determine the stimulation timing.

To develop an optimal control algorithm, a model of the activity and response to stimulation must be made, for which a controller can be designed (e.g. a firing rate model of the different neuronal populations involved in the seizure focus). Once a model is fit to the data and a control objective is defined, there are several approaches to designing optimal control algorithms. For linear and time invariant systems, there are well developed engineering tools for designing closed-loop controllers (Ogata 2010). Because EEG changes on a second by second basis, new adaptive nonlinear controllers need to be developed. Dynamic Programming (DP) is a general approach to finding an optimal solution to a control problem (Bellman and Rand Corporation. 1957). DP has been used to design optimal stimulus waveforms to minimize energy while maximally perturbing neuronal spikes (Nabi et al. 2013). However, for systems with more than a few parameters, this approach becomes intractably difficult to solve. Therefore, there is a great need to develop minimalist models that describe the pathological activity that can be used in control design algorithms.

3.3 Novel therapies

Aside from direct electrical stimulation strategies discussed above, other closed-loop approaches should be explored. For example, non-invasive closed-loop neuromodulation technologies using EEG biofeedback have also shown promising results in controlling seizures (Nagai et al. 2004; Sterman 2000; Tan et al. 2009). EEG biofeedback, or neurofeedback, modulates EEG activity at specific bandwidths through means of operant conditioning. With these promising results, and because it is noninvasive, neurofeedback should be investigated further.

Closed-loop approaches have been applied to other therapeutic modalities as well. For example, on-demand transcranial-electrical stimulation has been shown to terminate absence seizures in a rodent model (Berenyi et al. 2012). Focal cooling has long been used by surgeons to stop seizures during surgery (Rothman et al. 2005), and has been shown to be effective in a rodent seizure model (Hill et al. 2000; Yang et al. 2003; Yang et al. 2006; Yang and Rothman 2001) and suppress tumor related epileptic discharges (Karkar et al. 2002). Design of new implantable cooling therapy devices in human would therefore be of a great interest for refractory focal epilepsies (Smyth, 2011). Caged drugs, that can be uncaged optically on-demand (Rothman et al. 2007), and optogenetic approaches (discussed below) have also shown promising results in seizure control but have not yet been tested in humans.

3.4 Optogenetic intervention

Optogenetics is an exciting and expanding field making a significant impact on basic neuroscience research (Deisseroth 2011), and allowing new insights into neuronal networks and epilepsy (Krook-Magnuson et al. 2014). Optogenetics makes use of light sensitive proteins called opsins (Boyden et al. 2005). Opsins can be either excitatory or inhibitory (that is, making the cell more or less likely to fire an action potential) and can be expressed in discrete populations of neurons. In this way, the experimenter can directly modulate the activity levels of specific populations of neurons through the delivery of light. Optogenetics can be used in an on-demand fashion, which offers a degree of specificity not achievable through electrical, pharmacological, or cooling approaches. Specifically, optogenetics provides 1) location specificity (via where the light is delivered), 2) control of the direction of modulation (excitation versus inhibition), 3) cell-type specificity (via selective opsin expression), and 4) temporal specificity (with intervention limited to when light is delivered). Such specificity provides great experimental design benefits, and could provide seizure control with reduced side effects.

Optogenetics was first used in the field of epilepsy to suppress abnormal hypersynchronized activity in organotypic hippocampal slices using optogenetic inhibition of excitatory cells (Tønnesen et al. 2009). Since then, optogenetics has been used to induce seizures in vivo (Osawa et al. 2013), optimized for seizure suppression using computational methods (Selvaraj et al. 2013), and, importantly, optogenetics has been shown to suppress acute as well as spontaneous (during the chronic phase of the disease) seizures in different in vivo models of epilepsy (Berglind et al. 2014; Krook-Magnuson et al. 2013; Paz et al. 2013; Sukhotinsky et al. 2013; Wykes et al. 2012). It has been shown that optogenetic inhibition of principal excitatory cell scan delay pilocarpine induced seizure onsets (Sukhotinsky et al. 2013) and inhibit focal cortical seizures (Wykes et al. 2012). Similarly, optogenetics have been shown to induce epileptform bursts in bicuculline treated rats in vivo (Berglind et al. 2014).

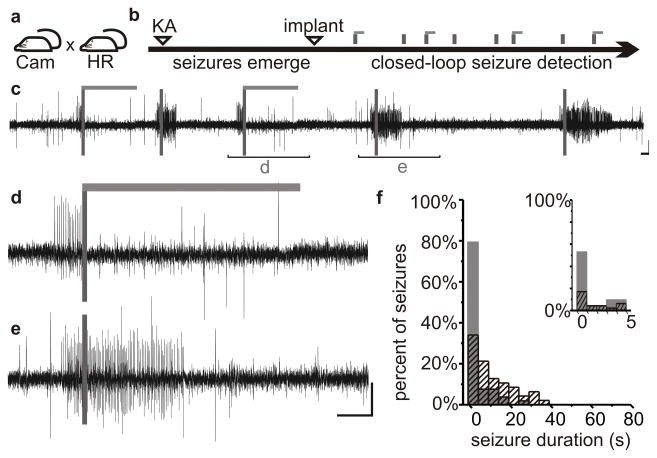

On-demand optogenetics techniques have successfully been used in models of two distinct types of epilepsy: 1) a cortical stroke model of thalamocortical epilepsy (Paz et al. 2013) and 2) the intrahippocampal kainate model of temporal lobe epilepsy (Krook-Magnuson et al. 2013). Seizures can be suppressed using two distinct approaches. Inhibitory opsins, such as halorhodopsin can be expressed in excitatory neurons, to directly suppress excitatory activity at the onset of a seizure (shown in Figure 4). Alternatively, excitatory opsins, such as channel rhodopsin (ChR2) can selectively be expressed in interneurons. Stimulation of parvalbumin-expressing interneurons expressing ChR2 following seizure onset successfully terminated seizures (Krook-Magnuson et al. 2013). These interneurons represent less than 5% of the total neuronal population in the hippocampal formation (Bezaire and Soltesz 2013; Freund and Buzsáki 1996; Woodson et al. 1989). Despite this highly restricted opsin expression, light application inhibited seizures (Krook-Magnuson et al. 2013).

Figure 4.

Optogenetic suppression of limbic seizures. Mice expressing halorhodopsin (a) in excitatory cells were injected unilaterally with kainate (KA) into the hippocampus (b). Inhibition of excitatory cells by light delivery (light gray horizontal bars) following seizure detection (c, dark grey vertical bars) leads to seizure suppression (d) compared with control events (e). Most seizures were reduced to less than one second post-detection duration (f). Gray bars: events receiving light; black hashed bars: no-light internal controls. Reproduced with modification with permission from Krook-Magnuson et al (2013).

These studies harness the power of selective intervention, using on-demand optogenetics to intervene in a cell-type and temporally selective manner, and indicate that highly selective intervention strategies can provide seizure control. Specifically, they demonstrate that on-demand optogenetics can be used in vivo to inhibit spontaneous seizures, including temporal lobe seizures and cortical stroke-induced thalamocortical seizures. The findings from these and future optogenetic studies of epilepsy can provide insight and offer refined targets for intervention by further dissecting neuronal circuits to determine the key regions and cell types involved in seizure initiation, propagation, and termination.

The need for improved therapeutic options for treating the epilepsies is clear, and on-demand optogenetics may one day be a clinical reality. There is a large population of patients with an unmet need for seizure control for whom on-demand optogenetics could be an attractive option, including patients with refractory bilateral temporal lobe epilepsy for whom surgical resection is not an option. However, there are a number of hurdles which will first need to be overcome before on-demand optogenetics can be used in a clinical setting. Clearly, any clinical optogenetic strategy will require safe and stable opsin expression. This potentially could be achieved through vector-based gene delivery, an area already making substantial strides (Bartus et al. 2013; Markert et al. 2000; Murphy and Rabkin 2013; Vezzani 2007). The unprecedented specificity of on-demand optogenetics provides a powerful tool to study epilepsy and may represent the future of seizure intervention.

3.5 Elucidating the mechanisms of therapies

The morphological changes associated with epileptogenesis have been well documented (Ben-Ari 2001; Houser 1992; Zeng et al. 2007). These changes are thought to result in networks that are more susceptible to epileptiform activity (Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen et al. 2007; McCormick and Contreras 2001; Netoff et al. 2004a). Stimulation has been shown to induce changes in neuronal excitability (Shen et al. 2003), neurogenesis (Toda et al. 2008), network architecture (McIntyre and Hahn 2010), neurotransmitter release (Windels et al. 2003; Windels et al. 2000) and synaptic plasticity (Engert and Bonhoeffer 1999; Kandel et al. 2000; Zhou et al. 2004). However, how these changes in cellular and network behavior relate to epileptogensis and ictogenesis is not understood.

In order to develop directed therapeutic approaches, these relationships must be elucidated. Furthermore, we must understand how therapies affect cellular excitability and network connectivity. With a better understanding of these mechanisms, it may be possible to develop patient specific approaches to designing therapies that produce more robust results within and across patients.

4 Hardware development

Medical devices providing electrical stimulation intervention have had tremendous clinical impact. At the moment, there are 268 ongoing clinical trials in DBS (clinicaltrials.gov). The design of devices requires collaboration between engineers, clinicians and scientists. It is critical to take into account the end users’ needs from the initial design. Neuroprosthetics require special consideration for the tissue-probe interface, heating, power management, size, and user interface. Importantly, design choices have tradeoffs. For instance, implanting an entire device into the neural tissue and under the skull necessitates a smaller physical area, heat dissipation, and power consumption. Algorithms requiring 100 channels of recorded data versus 4 channels greatly increase power consumption. Balancing these specifications into an elegant, robust, and usable product is the art of design.

A closed-loop device for epilepsy treatment should predict or detect seizures and deliver therapy with temporal precision while recording or transmitting information for post-processing. The hardware, software, and firmware must seamlessly integrate. Emphasis should be placed on technologies to enable closed-loop protocols and individualized therapy. Analogous to the structure-function relationship in biological systems, device architecture determines the functional capabilities. Key hardware blocks include the physical probes (sensing and modulating), front-end acquisition (neural amplifier), analog-to-digital converter (ADC), logic (seizure prediction, detection, control algorithms), neuromodulatory circuit (i.e. electrical or optical stimulation, drug delivery, cooling), telemetry, and power (management and possibly energy harvesting).

As technological advancements should be innovative, accessible and enabling, this portion of the review will highlight major concepts and challenges in device design for wireless, chronic application and offer a perspective for future developments. For chronic applications in small animals, primary challenges lie with the robustness of the tissue interface, heating, and driving down power consumption to allow more flexible power sources. Other issues include: hardware connectors for micro-scale components, integration of technologies, data management, wireless protocols, calibration and error checks, and implementation of control and adaptive algorithms. Importantly, for widespread use, the methods and technologies should be of low cost, accessible through open source or partnerships, and easily usable. Neural amplifier circuits are mature and will not be discussed here. For further investigation, the reader is encouraged to peruse other great reviews on these circuits (Harrison 2008; Jochum et al. 2009).

4.1 Wireless Neural-interfaces

Wireless telemetry from implanted recording devices to external computer systems provides a means to investigate EEG or other signals over long periods of time by reducing infection risk and increasing quality of life. Likewise, scientists benefit from wireless technology because it greatly reduces movement artifacts by removing the tether and provides better recordings in freely behaving animal experiments and in ambulatory patients. Low power high bandwidth wireless devices are being developed for many industries and should rapidly be incorporated into research and clinical devices for epilepsy. As yet, no device on the market enables stimulation and recording through the same electrode wirelessly.

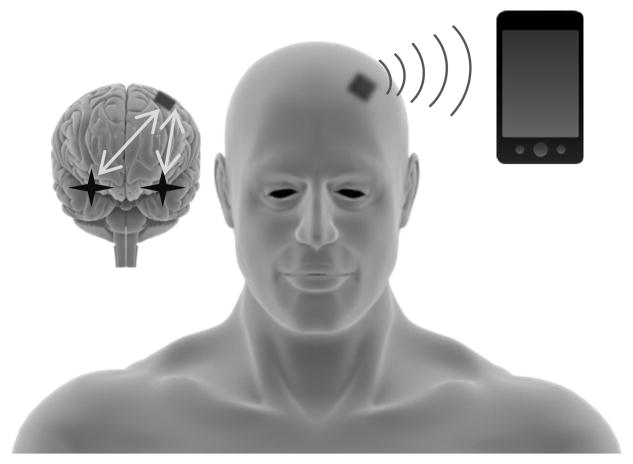

Wireless interfaces may also provide the user with limited control of parameters. This has been the trend with cardiac pacemakers, cochlear implants, and hearing aids. Smart-phone apps are being developed for almost every conceivable need. Smart-phones may enable recording, analyzing, and reporting information from implanted devices. Interpretation of the data may be left to the patient or their clinician (Figure 5) but potentially the phones may analyze data in real-time to identify seizures, record seizure rates over time, and even notify an emergency contact.

Figure 5.

Hypothetical wireless bidirectional adaptive multimodal neurostimulator interface. This device would capture superficial and deep physiological signals using a multimodal neural interface (stars and grey arrows in cartoon brain). These signals are digitized and analyzed in real-time using computationally efficient circuit architectures. Intervention is applied using electrical and/or optical stimulation. Signals are wirelessly transmitted via bluetooth to a nearby device or the patient’s smart phone. Data files can be instantly uploaded to a secure cloud-drive, and notifications sent to the clinician.

The future for wireless intervention will likely involve combinatorial therapy with pharmaceuticals (French and Gazzola 2013), closed-loop with electrical and molecular biomarkers (Altuna et al. 2013; Tooker et al. 2013), optogenetic and multisite stimulation techniques (Zorzos et al. 2012), and optimization of neuromodulation algorithms to eliminate side effects and improve device sustainability (Nabi et al. 2013). The Wireless Instantaneous Neurotransmitter Concentration System (WINCS) is one example of a device capable of sensing molecular biomarkers in real-time and wireless data transfer (Kimble et al. 2009), and there is an active push toward high density nano-scale sensors to monitor large scale brain activity (Alivisatos et al. 2013). Integration of these technologies into useful devices can point the way to eventual personalized clinical therapies (Borton et al. 2013) and allow researchers to tackle therapeutic questions that involve chronic experimentation. Solutions that emerge in clinic either offer incremental improvements to features and technology or are disruptive and revolutionary. As the community optimizes old solutions and introduce new concepts, being mindful of the challenges in product design can push the execution of translation (Thakor 2013).

4.2 The tissue-device interface

High spatial resolution data acquisition of multiunit activity has enabled valuable insights into ictogenesis (Schevon et al. 2012; Viventi et al. 2011; Worrell et al. 2008). Typically, high-density microelectrode arrays (MEA) are used. Microwire arrays, Michigan electrodes, and the Utah array are the primary tools. The purpose of these probes is to observe neural activity as close to the source as possible. The signals of interest, though, degrade over several months (Rousche and Normann 1998; Ward et al. 2009). Trauma from insertion leads to a chronic immune response resulting in variable electrode performance (Liu et al. 1999; Rennaker et al. 2005; Ward et al. 2009) and neuronal loss (Biran et al. 2005). Further, individual channels within MEAs do not stably record from the same neurons during the viable window (Rennaker et al. 2005; Rousche and Normann 1998). These are serious limitations, and device designers must rely on more robust low frequency content for seizure monitoring. For further information, Polikov et al. provide a detailed review of the immune response (Polikov et al. 2005). Several strategies to maintain a stable interface are under active investigation and aim to evade the immune response by 1) matching the mechanical properties between the probe and brain and 2) matching the chemical properties between the probe and brain. Current techniques use biocompatible coatings (He and Bellamkonda 2005; Ignatius et al. 1998), flexible polymer interfaces (Cheung et al. 2007; Green et al. 2008; Mercanzini et al. 2008; Rousche et al. 2001) and shaping ultra-thin probes (Seymour and Kipke 2007). As probes become thinner and more flexible, insertion into deep tissue sites becomes increasingly difficult. This has led to the development of several novel delivery mechanisms (Jaroch et al. 2009; Richardson-Burns et al. 2007; Sharp et al. 2006; Takeuchi et al. 2004). Engineers must be aware of the probe design, delivery, and chronic stability at the biological interface. These parameters and limitations must be accounted for in the device design.

Heating of surrounding tissue can cause altered physiology, cell injury, and cell death (LaManna et al. 1989; Seese et al. 1998). Additionally, temperature changes of a few degrees Celsius have correlated behavioral changes (Moser et al. 1993). Device heating is directly related to the power dissipation, and higher power neuromodulatory techniques at the tissue-interface must proceed with caution. For instance, in deep brain optical stimulation in optogenetics, LEDs can either reside external to the skull and couple to a light guide (Huber et al.; Iwai et al. 2011; Wentz et al. 2011) or implanted adjacent to the target brain region (Kim et al. 2013). Heating of tissue is a concern in both situations; however, implanted LEDs face more stringent constraints. In large-scale recording systems (i.e. 100 channels), the power consumption per amplifiers must be limited to prevent heating, and this can pose as serious challenge when optimizing circuit performance (Harrison et al. 2007). Power dissipation and heating characterization should be a primary consideration early in the design process.

With the intention of chronic experimentation, devices for rodents should consume on the order microwatts or less to minimize heating and broaden the option of power sources. Often, devices consume on the order of milliwatts. This can still be reasonable, but the choice of appropriately sized batteries for rodents becomes limiting and battery replacement during chronic experimentation will be required often. Useful design techniques are low duty cycle algorithms to limit the working time of high power activity and operation of novel integrated circuits (IC) at low working voltages.

4.3 Devices for seizure monitoring and therapy

Seizure monitoring fundamentally relies on the changes in the power and frequency of the extracellular electrographic recordings (Osorio et al. 1998). Seizure prediction or detection algorithms need to be computationally efficient for implementation on hardware. A comparison of algorithms can help the designer determine the appropriate solution by evaluating methods using the same criteria and definitions for sensitivity, specificity, and hardware associated costs (Pang et al. 2003; Raghunathan et al. 2010; White et al. 2006). As more channels are needed, there is an increased demand for techniques to reduce the amount of data transmitted. Recently, there have been attempts at compressive sampling to drastically reduce sampling rates (Candès and Wakin 2008; Shoaib et al. 2012). Another strategy is to perform on-board processing of the signals before transmission. Feature extraction has been used to only capture “important” information (Chandler et al. 2011; Verma et al. 2010), which can result in a 14:1 power reduction (Verma et al. 2010). Additionally, feature extraction techniques allow the use of asynchronous protocols to transmit data only upon detection (Salam et al. 2012). To further minimize telemetry, full classification of EEG data can be done on the implantable device (Yoo et al. 2012).

Integrated circuits are often used in application-based research but translating these devices to a clinical setting can be difficult. Academic labs have less of a focus on testing and quantifying the variability in the fabrication processes, therefore IC yield can often be quite low leading to problems with repeatability and distribution. This can impede the use of neuroprosthetics in academic research. Additionally, while IC can provide novel integrated designs (Chen et al. 2013; Harrison and Charles 2003; Raghunathan et al. 2009; Verma et al. 2010), the development and distribution is costly. Only after many years of testing and validation are we beginning to see some of the first commercial endeavors making ICs dedicated for physiology recording (www.intantech.com). Another avenue for device development is to use commercial off-the-shelf components (COTS)(Liang et al. 2011; Salam et al. 2012) or modify existing platforms (Stanslaski et al. 2012). While ICs are considered the gold standard of circuit design and will always produce the smallest and lowest power systems, COTS parts provide the necessary robust performance. Microprocessors are being designed for ultra-low power capabilities and are becoming increasingly small. Critically, the iteration cycle for COTS based devices can be weeks (versus several months to a year for IC design). By encouraging the use of COTS components in devices, access to neuroprosthetics for academic labs to enable experiments can be more rapidly realized.

5 The future of epilepsy treatment

There are many exciting developments in the field of seizure detection, prediction and closed loop therapies. For patients that are drug refractory, the development of devices for treatment of seizures provides some hope. There are still obstacles to developing new devices for clinical use. Overcoming them will depend on integration of research and ideas across many disciplines. The following is a summary we see as the important directions guiding the future of seizure prediction and intervention:

-

Patient specific treatment optimization

Devices should be designed for a broad patient population while the parameters involved in therapeutic intervention should be correlated with the patient’s physiology to provide seizure control with reduced side effects.

There is a need not only to find biomarkers of ictogenesis, but also to find biomarkers of epileptogenesis. Functional, biochemical and computational tools should be used to characterize therapeutic effects. With this knowledge, we may be able to develop closed-loop therapies that can restore normal function.

When pre-ictal events are identified, they should be labeled as “putative positives” rather than “false positives” to emphasize the fact that these mark conditions the patient could be at high risk for a seizure even though a seizure did not occur.

New intervention strategies are needed. Optogenetics, biofeedback, focal cooling, optical uncaging of drugs and other therapies will certainly be added to electrical stimulation as therapeutic intervention for suppressing seizures.

Closed-loop therapies can also be used to deliver precisely timed stimulus pulses to disrupt pathological activity.

-

Big data and new recording modalities for identifying pre-ictal and ictal states

As scientists, we should encourage patients to exercise their power to make long-term recordings for clinical trials available to the scientific community, within a reasonable time following a study.

Utilize powerful machine learning tools designed for “Big Data” problems for seizure prediction and detection paradigms.

Data assimilation, computational modeling coupled with data analysis, will enable real-time data classification, a mechanistic understanding of dynamical changes, and enable the design of optimized closed-loop therapies.

There is a need to have a centralized and long term solution for management of physiological signals databases. This might require National Library of Medicine to host and manage these data sources

To ensure scientists contribute their data to these databases, there is a need for developing mechanisms for citing data sources so that scientists contributing valuable data will get credit for their efforts.

-

Need for new hardware

The hardware should be considered a platform, not a single device. Software should be updatable as our understanding of the disease and technology improves. Developing a seizure detection and prediction device will be an iterative process.

New devices that measure multiple modalities simultaneously are needed. It is unlikely that seizure prediction will be successful using EEG or any single modality alone.

Hardware designs needs to empower patient with some control of their therapy. This will increase patient satisfaction as well as provide the first steps necessary to developing fully automated control systems.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

US National Institutes of Health grant K99NS087110 (E.K-M)

Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy (CURE) Taking Flight Award (to E.K-M.)

US National Institutes of Health grant NS074432 (to I.S.)

NSF CAREER award from GARDE (TIN)

Epilepsy Foundation grant (TIN)

NIH pre-doctoral training grant (T32) (VN)

3M Science & Technology Fellowship (VN)

Cyberonics, Inc. (SL & PI)

The authors would like to acknowledge the organizers of the International Seizure Prediction Workshop 7, Bruce Gluckman, Catherine Schevon, Bjoern Schelter, and Susan Arthurs. As well as William Stacey, Mark Cook, and all the presenters at the conference for their insights.

References

- Aarabi A, He B. Seizure prediction in hippocampal and neocortical epilepsy using a model-based approach. Clin Neurophysiol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abegg MH, Savic N, Ehrengruber MU, McKinney RA, Gähwiler BH. Epileptiform activity in rat hippocampus strengthens excitatory synapses. J Physiol. 2004;554:439–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alivisatos AP, Andrews AM, Boyden ES, Chun M, Church GM, Deisseroth K, Donoghue JP, Fraser SE, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Looger LL, Masmanidis S, McEuen PL, Nurmikko AV, Park H, Peterka DS, Reid C, Roukes ML, Scherer A, Schnitzer M, Sejnowski TJ, Shepard KL, Tsao D, Turrigiano G, Weiss PS, Xu C, Yuste R, Zhuang X. Nanotools for neuroscience and brain activity mapping. ACS Nano. 2013;7:1850–1866. doi: 10.1021/nn4012847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altuna A, Bellistri E, Cid E, Aivar P, Gal B, Berganzo J, Gabriel G, Guimera A, Villa R, Fernandez LJ, Menendez de la Prida L. SU-8 based microprobes for simultaneous neural depth recording and drug delivery in the brain. Lab on a chip. 2013;13:1422–1430. doi: 10.1039/c3lc41364k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrzejak RG, Mormann F, Kreuz T, Rieke C, Kraskov A, Elger CE, Lehnertz K. Testing the null hypothesis of the nonexistence of a preseizure state. Physical review E, Statistical, nonlinear, and soft matter physics. 2003;67:010901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.67.010901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C, Krook-Magnuson E, Oijala M, Soltesz I. Closed-loop optogenetic intervention in mice. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1475–1493. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Louvel J, Pumain R, Köhling R. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of epilepsy in the human brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;77:166–200. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartus RT, Baumann TL, Siffert J, Herzog CD, Alterman R, Boulis N, Turner DA, Stacy M, Lang AE, Lozano AM, Olanow CW. Safety/feasibility of targeting the substantia nigra with AAV2-neurturin in Parkinson patients. Neurology. 2013;80:1698–1701. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182904faa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellman R Rand Corporation. Dynamic programming. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1957. p. xxv.p. 342. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. Cell death and synaptic reorganizations produced by seizures. Epilepsia. 2001;42 (Suppl 3):5–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042suppl.3005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengio Y. Learning deep architectures for AI. Foundations and trends® in Machine Learning. 2009;2:1–127. [Google Scholar]

- Berenyi A, Belluscio M, Mao D, Buzsaki G. Closed-loop control of epilepsy by transcranial electrical stimulation. Science (New York, NY) 2012;337:735. doi: 10.1126/science.1223154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglind F, Ledri M, Sørensen AT, Nikitidou L, Melis M, Bielefeld P, Kirik D, Deisseroth K, Andersson M, Kokaia M. Optogenetic inhibition of chemically induced hypersynchronized bursting in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;65:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezaire MJ, Soltesz I. Quantitative assessment of CA1 local circuits: knowledge base for interneuron-pyramidal cell connectivity. Hippocampus. 2013;23:751–785. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnie CD, Aarts JH, Houtkooper MA, Laxminarayan R, Martins da Silva A, Meinardi H, Nagelkerke N, Overweg J. Temporal characteristics of seizures and epileptiform discharges. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1984;58:498–505. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(84)90038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biran R, Martin DC, Tresco PA. Neuronal cell loss accompanies the brain tissue response to chronically implanted silicon microelectrode arrays. Exp Neurol. 2005;195:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borton D, Micera S, Millán Je R, Courtine G. Personalized neuroprosthetics. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:210rv212. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower MR, Buckmaster PS. Changes in granule cell firing rates precede locally recorded spontaneous seizures by minutes in an animal model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:2431–2442. doi: 10.1152/jn.01369.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower MR, Stead M, Meyer FB, Marsh WR, Worrell GA. Spatiotemporal neuronal correlates of seizure generation in focal epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53:807–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candès EJ, Wakin MB. An introduction to compressive sampling. Signal Processing Magazine, IEEE. 2008;25:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Case M, Soltesz I. Computational modeling of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;52 (Suppl 8):12–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabardès S, Kahane P, Minotti L, Koudsie A, Hirsch E, Benabid AL. Deep brain stimulation in epilepsy with particular reference to the subthalamic nucleus. Epileptic Disord. 2002;4 (Suppl 3):S83–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler D, Bisasky J, Stanislaus JL, Mohsenin T. Real-time multi-channel seizure detection and analysis hardware. Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), 2011 IEEE; IEEE; 2011. pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chen W-M, Chiueh H, Chen T-J, Ho C-L, Jeng C, Chang S-T, Ker M-D, Lin C-Y, Huang Y-C, Chou C-W. A fully integrated 8-channel closed-loop neural-prosthetic SoC for real-time epileptic seizure control. Solid-State Circuits Conference Digest of Technical Papers (ISSCC), 2013 IEEE International; IEEE; 2013. pp. 286–287. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung KC, Renaud P, Tanila H, Djupsund K. Flexible polyimide microelectrode array for in vivo recordings and current source density analysis. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:1783–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook MJ, O’Brien TJ, Berkovic SF, Murphy M, Morokoff A, Fabinyi G, D’Souza W, Yerra R, Archer J, Litewka L, Hosking S, Lightfoot P, Ruedebusch V, Sheffield WD, Snyder D, Leyde K, Himes D. Prediction of seizure likelihood with a long-term, implanted seizure advisory system in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: a first-in-man study. Lancet neurology. 2013;12:563–571. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Thompson SM, Gähwiler BH. A brief period of epileptiform activity strengthens excitatory synapses in the rat hippocampus in vitro. Epilepsia. 2006;47:247–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K. Optogenetics. Nat Methods. 2011;8:26–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demont-Guignard S, Benquet P, Gerber U, Biraben A, Martin B, Wendling F. Distinct hyperexcitability mechanisms underlie fast ripples and epileptic spikes. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:342–352. doi: 10.1002/ana.22610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demont-Guignard S, Benquet P, Gerber U, Wendling F. Analysis of intracerebral EEG recordings of epileptic spikes: insights from a neural network model. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2009;56:2782–2795. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2028015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- During MJ, Spencer DD. Adenosine: a potential mediator of seizure arrest and postictal refractoriness. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:618–624. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- During MJ, Spencer DD. Extracellular hippocampal glutamate and spontaneous seizure in the conscious human brain. Lancet. 1993;341:1607–1610. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen J, Santhakumar V, Morgan RJ, Huerta R, Tsimring L, Soltesz I. Topological determinants of epileptogenesis in large-scale structural and functional models of the dentate gyrus derived from experimental data. Journal of neurophysiology. 2007;97:1566. doi: 10.1152/jn.00950.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einevoll GT, Franke F, Hagen E, Pouzat C, Harris KD. Towards reliable spike-train recordings from thousands of neurons with multielectrodes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engert F, Bonhoeffer T. Dendritic spine changes associated with hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity. Nature. 1999;399:66–70. doi: 10.1038/19978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R, Salanova V, Witt T, Worth R, Henry T, Gross R, Oommen K, Osorio I, Nazzaro J, Labar D, Kaplitt M, Sperling M, Sandok E, Neal J, Handforth A, Stern J, DeSalles A, Chung S, Shetter A, Bergen D, Bakay R, Henderson J, French J, Baltuch G, Rosenfeld W, Youkilis A, Marks W, Garcia P, Barbaro N, Fountain N, Bazil C, Goodman R, McKhann G, Babu Krishnamurthy K, Papavassiliou S, Epstein C, Pollard J, Tonder L, Grebin J, Coffey R, Graves N, Group SS. Electrical stimulation of the anterior nucleus of thalamus for treatment of refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2010;51:899. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RS. Deep brain stimulation for epilepsy. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;116:217–234. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53497-2.00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca A, Aalbers M, Frigerio F, Fiordaliso F, Salio M, Gobbi M, Cagnotto A, Gardoni F, Battaglia GS, Hoogland G, Di Luca M, Vezzani A. Misplaced NMDA receptors in epileptogenesis contribute to excitotoxicity. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;43:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman WJ. A model of the olfactory system. Neural modeling. 1973:41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Freestone DR, Long SN, Frey S, Stypulkowski PH, Giftakis JE, Cook MJ. A method for actively tracking excitability of brain networks using a fully implantable monitoring system. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2013;2013:6151–6154. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2013.6610957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French JA, Gazzola DM. Antiepileptic drug treatment: new drugs and new strategies. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2013;19:643–655. doi: 10.1212/01.CON.0000431380.21685.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Buzsáki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Harrison L, Penny W. Dynamic causal modelling. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1273–1302. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RA, Lovell NH, Wallace GG, Poole-Warren LA. Conducting polymers for neural interfaces: challenges in developing an effective long-term implant. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3393–3399. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handforth A, DeGiorgio CM, Schachter SC, Uthman BM, Naritoku DK, Tecoma ES, Henry TR, Collins SD, Vaughn BV, Gilmartin RC, Labar DR, Morris GL, Salinsky MC, Osorio I, Ristanovic RK, Labiner DM, Jones JC, Murphy JV, Ney GC, Wheless JW. Vagus nerve stimulation therapy for partial-onset seizures: a randomized active-control trial. Neurology. 1998;51:48–55. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RR. The design of integrated circuits to observe brain activity. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2008;96:1203–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RR, Charles C. A low-power low-noise CMOS amplifier for neural recording applications. Solid-State Circuits, IEEE Journal of. 2003;38:958–965. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RR, Watkins PT, Kier RJ, Lovejoy RO, Black DJ, Greger B, Solzbacher F. A low-power integrated circuit for a wireless 100-electrode neural recording system. Solid-State Circuits, IEEE Journal of. 2007;42:123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia. 1993;34:453. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Bellamkonda RV. Nanoscale neuro-integrative coatings for neural implants. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2983–2990. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck CN, King-Stephens D, Massey AD, Nair DR, Jobst BC, Barkley GL, Salanova V, Cole AJ, Smith MC, Gwinn RP, Skidmore C, Van Ness PC, Bergey GK, Park YD, Miller I, Geller E, Rutecki PA, Zimmerman R, Spencer DC, Goldman A, Edwards JC, Leiphart JW, Wharen RE, Fessler J, Fountain NB, Worrell GA, Gross RE, Eisenschenk S, Duckrow RB, Hirsch LJ, Bazil C, O’Donovan CA, Sun FT, Courtney TA, Seale CG, Morrell MJ. Two-year seizure reduction in adults with medically intractable partial onset epilepsy treated with responsive neurostimulation: Final results of the RNS System Pivotal trial. Epilepsia. 2014;55:432–441. doi: 10.1111/epi.12534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MW, Wong M, Amarakone A, Rothman SM. Rapid cooling aborts seizure-like activity in rodent hippocampal-entorhinal slices. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1241–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb04601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt AB, Netoff TI. Computational modeling of epilepsy for an experimental neurologist. Exp Neurol. 2013;244:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser CR. Morphological changes in the dentate gyrus in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992;7:223–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AL, Neu A, Morgan RJ, Echegoyen JC, Soltesz I. Opposing modifications in intrinsic currents and synaptic inputs in post-traumatic mossy cells: evidence for single-cell homeostasis in a hyperexcitable network. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2394–2409. doi: 10.1152/jn.00509.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howbert JJ, Patterson EE, Stead SM, Brinkmann B, Vasoli V, Crepeau D, Vite CH, Sturges B, Ruedebusch V, Mavoori J, Leyde K, Sheffield WD, Litt B, Worrell GA. Forecasting seizures in dogs with naturally occurring epilepsy. PloS one. 2014;9:e81920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D, Petreanu L, Ghitani N, Ranade S, Hromádka T, Mainen Z, Svoboda K. Sparse optical microstimulation in barrel cortex drives learned behaviour in freely moving mice. Nature. 2008;451:61–64. doi: 10.1038/nature06445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iasemidis LD. Epileptic seizure prediction and control. IEEE transactions on bio-medical engineering. 2003;50:549. doi: 10.1109/tbme.2003.810705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iasemidis LD, Sackellares JC, Zaveri HP, Williams WJ. Phase space topography and the Lyapunov exponent of electrocorticograms in partial seizures. Brain topography. 1990;2:187–201. doi: 10.1007/BF01140588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatius MJ, Sawhney N, Gupta A, Thibadeau BM, Monteiro OR, Brown IG. Bioactive surface coatings for nanoscale instruments: effects on CNS neurons. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;40:264–274. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199805)40:2<264::aid-jbm11>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai Y, Honda S, Ozeki H, Hashimoto M, Hirase H. A simple head-mountable LED device for chronic stimulation of optogenetic molecules in freely moving mice. Neurosci Res. 2011;70:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaroch DB, Ward MP, Chow EY, Rickus JL, Irazoqui PP. Magnetic insertion system for flexible electrode implantation. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;183:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerger KK, Netoff TI, Francis JT, Sauer T, Pecora L, Weinstein SL, Schiff SJ. Comparison of Methods for Seizure Detection. In: Milton J, Jung P, editors. Epilepsy as a Dynamic Disease. New York, NY: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jirsa VK, Stacey WC, Quilichini PP, Ivanov AI, Bernard C. On the nature of seizure dynamics. Brain. 2014;137:2210–2230. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]