Abstract

Background/Aims:

This study aimed to evaluate the antiviral response and safety of tenofovir (TDF) versus entecavir (ETV) in treatment-naïve CHB patients.

Patients and Methods:

We performed a retrospective cohort study of treatment-naive CHB patients who were treated with TDF or ETV. We analyzed virologic, biochemical, and serologic responses at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Results:

A total of 107 patients (TDF group = 49, ETV group = 58) were included. Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups. The estimated proportion of complete virologic response (CVR) in the TDF or ETV group was 44.9% versus 39.7% at 6 months and 89.6% versus 83.2% at 12 months, respectively (P = 0.991). Viral breakthrough was not observed in both groups. One patient in the TDF group and two patients in the ETV group experienced HBeAg loss, respectively (P = 0.657). High HBV DNA level at baseline was a significant negative predictor of virologic response by Cox regression analysis (P = 0.007). The safety profile was similar between the two groups. There was no case with serious adverse event.

Conclusions:

Both TDF and ETV were effective in achieving CVR and had a favorable safety profile in treatment-naïve CHB patients. High viral load at baseline was a negative predictive factor of CVR.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis B, efficacy, entecavir, safety, tenofovir

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a major health problem in the world. CHB affects 350–400 million people worldwide.[1] Seventy percent of patients with chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis, and 65%–75% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were related with positive serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).[2,3] Annually, one million people die from liver cirrhosis, hepatic failure, and hepatocelluar carcinoma.[1]

The goals of treatment of CHB are to prevent liver complications and to improve survival rate.[4,5] The ultimate goal is to achieve HBsAg loss and seroconversion, but because covalently closed circular DNA persists in the nucleus despite treatment, complete clearance of HBV is almost impossible.[6] Undetectable HBV DNA, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) normalization, hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg) loss or seroconversion, and histologic improvement are used to estimate the response of treatment in clinical practice.[6,7]

Current guidelines recommend a single agent with a potent antiviral activity and high genetic barrier, such as tenofovir (TDF) or entecavir (ETV), as the first-line antiviral agents for CHB.[6,7] Both TDF and ETV selectively inhibit HBV viral replication with potent activity.[8,9] ETV is effective as monotherapy in treatment-naïve patients with low rates of resistance (0.5%–1.2%) for up to 6 years of treatment.[10,11] Significant resistance mutations to TDF have not been reported in patients with HBV monoinfection.[12,13] However, there are few studies that directly compare their effectiveness.

We compared antiviral response and safety of TDF and ETV for achieving complete virologic response (CVR) in treatment-naïve CHB patients. We also evaluated the rates of normalization of ALT and HBeAg loss or seroconversion, and predictive factors for CVR.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

The study enrolled 18-70 year old patients with HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative chronic HBV who had never received any prior treatment. CHB patients with an HBV DNA level of ≥2,000 IU/mL and ALT level of two times or more than the upper normal limit were included. Patients with compensated liver cirrhosis were included if the DNA level was ≥2,000 IU/mL, regardless of the ALT level. Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed through imaging studies such as computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging and/or abdominal sonography, and/or proven esophageal or gastric varix by esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and/or low platelet count (less than 100,000/μL). All patients were treated with TDF or ETV monotherapy for at least 6 months. Further eligibility criteria were no evidence of decompensated liver cirrhosis and no evidence of coinfection with hepatitis C virus, other hepatitis viruses, or human immunodeficiency virus. Patients with poor compliance, other malignant disease except hepatocelluar carcinoma, other causes of liver cirrhosis except HBV infection, follow up loss in clinics, or a history of any chemotherapies, any radiation therapies, or any immunosuppressive therapies were excluded.

We performed a retrospective cohort study of adult CHB patients who visited the hepatology clinic at our Hospital from September 2010 to April 2014. TDF group consisted of consecutive patients treated with TDF 300 mg daily since December 2012, and the ETV group consisted of patients treated with ETV 0.5 mg daily since September 2010. Although most patients of the ETV group were treated for more than 12 months, only up to 12 months of their data were used for comparison of effectiveness between the TDF group and the ETV group.

Patients were identified through electronic search of all CHB patient medical records at our treatment center, and data were retrieved via individual record review. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Konkuk University Medical Center (KUH1010592).

Study design

The primary objective was to evaluate virologic response of TDF and ETV at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, measured by the proportion of patients achieving CVR defined as undetectable serum HBV DNA (<120 copies/mL).[6,7] Virologic breakthrough was defined as two consecutive 1 log10 or > 10-fold increase in plasma HBV DNA from nadir or two consecutive values ≥120 copies/mL after being CVR. High viral load was defined as serum HBV DNA ≥ 7 log10 copies/mL.

The secondary outcomes were the changes in HBV DNA level and ALT level, normalization of ALT level (≤40 IU/mL), the overall incidence of HBeAg loss or seroconversion to antibody to HBeAg in the HBeAg-positive patients, as well as HBsAg loss. All adverse effects were investigated on the basis of medical records of all patients. Adverse effects of TDF and ETV and discontinuation of the drugs due to adverse effects were evaluated by review of the medical records for symptoms and laboratory data. Renal toxicity was defined as increase in creatinine level of ≥0.3 mg/dL or 1.5 times above baseline, or serum phosphorus level <2mg/dL.[14] Hepatotoxicity was defined as elevation of ALT level more than two times above baseline or more than 10 times the upper normal limit, or total bilirubin more than 1.5 times the upper normal limit.[15]

Statistical analysis

All statistical data were analyzed using SPSS Inc. for Windows, ver. 17.0. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test. Continuous variables were evaluated using the Student's t test. The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to estimate the proportion of CVR and normalization of ALT level. The Cox regression analysis was used to estimate predictors of CVR. For all statistical tests, a two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics

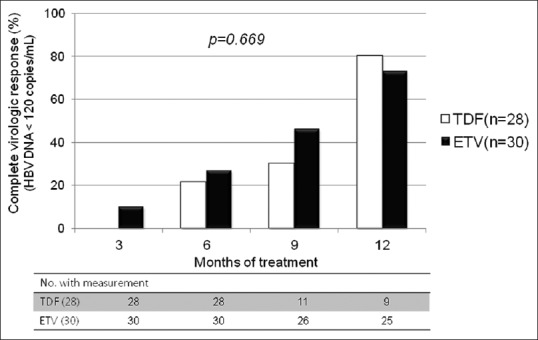

A total of 107 patients were eligible as per inclusion criteria, of whom 49 were treated with TDF and 58 were treated with ETV. Baseline characteristics were similar between the TDF and the ETV groups [Table 1]. Of the total cohort, 55 patients were male, the mean age was 50.3 years, 53 patients (49.5%) had liver cirrhosis, and 62 patients (57.9%) were HBeAg positive. The mean of HBV DNA level was 7.01 log10 copies/mL. HBeAg was positive in 53.1% of the TDF group and 62.1% of the ETV group, respectively. The mean of baseline HBV DNA in each group was 6.98 log10 copies/mL in the TDF group and 7.05 log10 copies/mL in the ETV group. The follow-up duration was significantly different between the two groups, the TDF group was 8.45 months and the ETV group was 18.7 months (P <0.001). The ETV group had greater number of patients with liver cirrhosis than the TDF group (60.3% vs. 36.7%, P = 0.015).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of treatment-naïve chronic hepatitis B patients treated with TDF or ETV

Treatment responses

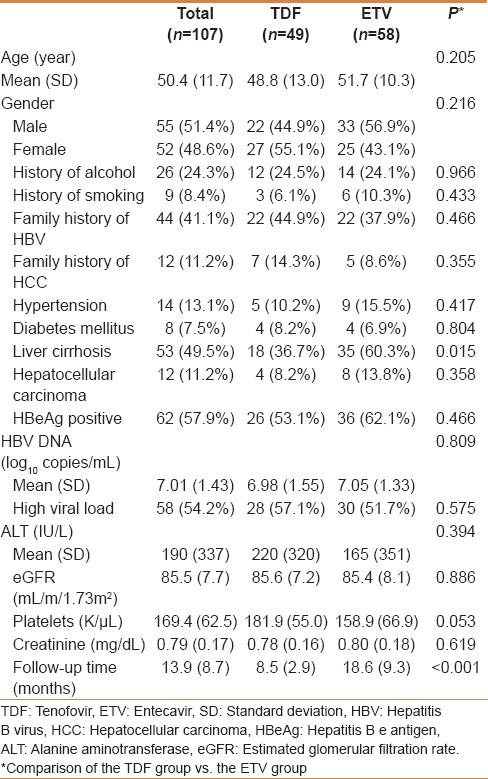

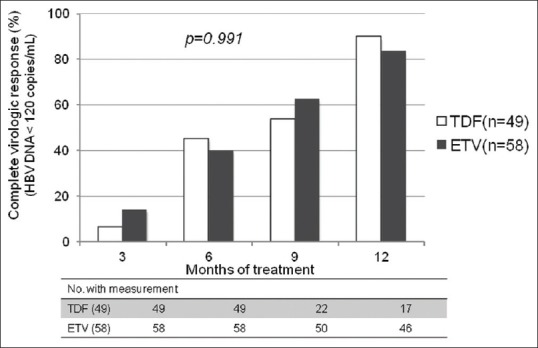

The estimated proportion of CVR between the TDF and the ETV group was 6.1% vs. 13.8% at 3 months, 44.9% vs. 39.7% at 6 months, 53.4% vs. 62.3% at 9 months and 89.6% vs. 83.2% at 12 months, respectively [Figure 1]. There was no significant difference in CVR rates between the TDF and the ETV groups (P =0.991). The decline of HBV DNA level was−4.83 log10 copies/mL from 6.98 log10 copies/mL to 2.15 log10 copies/mL in the TDF group, and−4.84 log10 copies/mL from 7.05 log10 copies/mL to 2.21 log10 copies/mL in the ETV group [Figure 2]. Changes of HBV DNA levels between the TDF and the ETV group were not different (P =0.809). Virologic breakthrough was not observed in the two groups during the 12 months of treatment.

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients achieving complete virologic response between the TDF and the ETV groups. TDF, tenofovir; ETV, entecavir

Figure 2.

Changes in HBV DNA level between the TDF and the ETV groups. TDF, tenofovir; ETV, entecavir

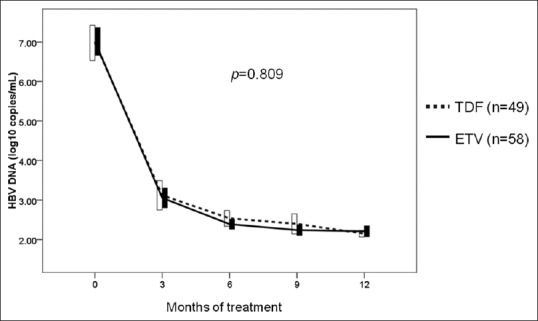

We analyzed the virologic response of TDF and ETV in patients with high viral load (HBV DNA ≥7 log10 copies/mL). The estimated proportion of CVR between the TDF and the ETV group was 21.4% vs. 26.7% at 6 months, 30.2% vs. 46.0% at 9 months, and 80.0% vs. 73.0% at 12 months, respectively [Figure 3]. There was no significant difference in CVR rates between the TDF and the ETV groups (P = 0.669).

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients achieving complete virologic response in high viral load patients. TDF, tenofovir; ETV, entecavir

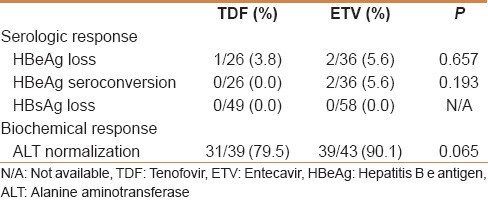

The rates of HBeAg loss and seroconversion to anti-HBe among the HBeAg-positive patients were not significantly different between the TDF and the ETV groups [Table 2]. One patient (3.8%) in the TDF group and two patients (5.6%) in the ETV group experienced HBeAg loss, and two patients (5.6%) in the ETV group experienced seroconversion to anti-HBe antibody. No patient experienced HBsAg loss in the two groups.

Table 2.

Serologic and biochemical response between the TDF and the ETV group at 12 months

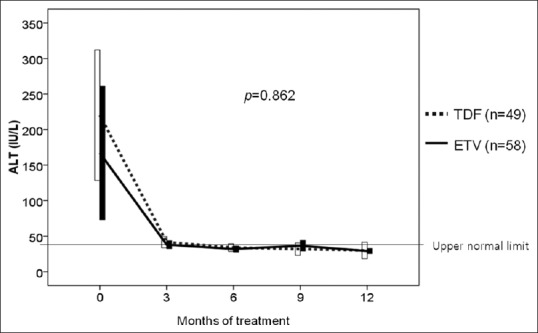

There were 39 patients with abnormal ALT at the baseline in the TDF group and 43 patients in the ETV group. At 12 months, 31 (79.5%) patients achieved ALT normalization in the TDF group and 39 (90.1%) in the ETV group. There was no difference in changes of ALT level between the TDF and the ETV groups (P =0.862) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Comparisons of changes in ALT level between TDF and ETV groups. TDF, tenofovir; ETV, entecavir; ALT, alanine aminotransferase

Safety

There were significant adverse events. One patient (2.0%) in the TDF group and one patient (1.7%) in the ETV group experienced adverse renal effects (P = 0.904). Three patients (6.1%) in the TDF group and two patients (3.4%) in the ETV groups experienced hepatic adverse effect (P = 0.514). No significant differences were observed between the TDF and the ETV groups in the overall incidence of all adverse effects. And there were no discontinuations or dose modifications due to adverse effects.

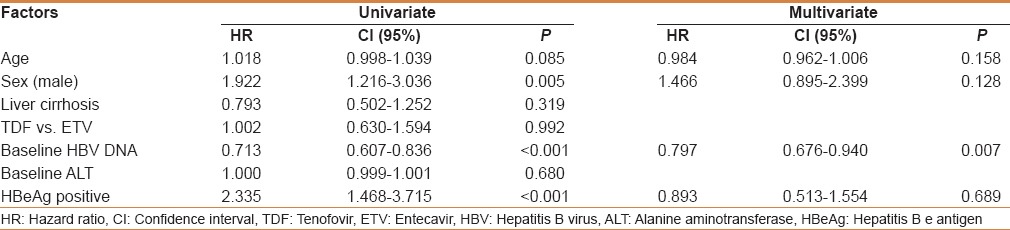

Predictors of virologic response

The Cox regression univariate analysis for predictors showed that gender, HBeAg-positivity, and baseline HBV DNA level were significantly associated with CVR at 12 months of TDF or ETV treatment. However, presence of liver cirrhosis in TDF vs. ETV was not a significant factor for CVR. Multivariate analysis showed only the baseline HBV DNA level as a significant predictor of CVR (hazard ratio = 0.797; 95% confidence interval = 0.676–0.940; P =0.007).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated antiviral response and safety of TDF and ETV in treatment-naïve CHB patients. Both TDF and ETV had good virologic responses that were comparable between the groups. TDF and ETV have a similar mechanism to inhibit HBV DNA polymerase. TDF is an analog of adenosine 5’-monophosphate that inhibits HBV DNA polymerases by direct binding,[12] and ETV is a carboxylic analog of 2’-deoxyguanosine that inhibits HBV DNA polymerase by competing with the natural deoxyguanosine triphosphate.[16] Rates of CVR for TDF range from 67% to 90% and ETV from 74% to 91% after 12 months of treatment, respectively.[17] The current guidelines recommend TDF and ETV as first-line antiviral agents for CHB because of potent viral suppression activity and low rates or absence of resistance.[6,7,10,11,12,13]

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics analysis of gender, HBeAg status, and baseline HBV DNA level between the TDF and the ETV groups. However, follow-up time of the TDF group was shorter than the ETV group, because TDF was recently (end of 2012) approved for the treatment of CHB patients, in Korea. The prevalence of liver cirrhosis was higher in the ETV group, in our study. This might be due to extension of insurance coverage for ETV use in CHB patients with liver cirrhosis, during the study period.

Our results showed no significant difference in CVR rates between the TDF and the ETV group (P = 0.991), and no difference in changes of HBV DNA level between the two groups (P = 0.809). There are few studies comparing the efficacy between TDF and ETV. Previous studies reported no significant difference in CVR rates between TDF and ETV in nucleos (t) ide-naive patients after 48 weeks of treatment.[18,19] A recent meta-analysis study suggested that there was no significant difference in virologic response between TDF and ETV in CHB patients after 24 weeks and 48 weeks of antiviral therapy.[20] However, the comparative efficacy between TDF and ETV, particularly in patients with high viral load, remains controversial. A recent study reported that TDF had better virologic response than ETV in CHB patients after 24 months of treatment; however, there was no difference in the decline in serum HBV DNA levels.[21]

The rates of HBeAg loss and seroconversion to anti-HBe were not significantly different among the HBeAg-positive patients, between the TDF and the ETV groups. Nevertheless, HBeAg loss rates and seroconversion rates were lower than those in the previous studies.[17,19] Most Korean CHB patients are infected with HBV genotype C via maternal transmission at birth.[22] This genotype is known to have a lower rate of HBeAg seroconversion, a more rapid progress to hepatocelluar carcinoma and cirrhosis, and have a higher rate of relapse after antiviral treatments, compared with other genotypes.[23,24]

ALT normalization is usually used as a virologic response and indication of cessation of liver injury. We found no significant difference in biochemical response between the TDF and the ETV groups (P =0.065). ALT normalization rates of the TDF group (79.5%) and the ETV group (90.1%) were similar to previous reports.[18,19,20]

The safety profile was not different between the TDF and the ETV groups [Table 3]. There were no deaths, discontinuations, or dose modifications due to serious adverse effects. All adverse effects were well tolerated by patients, during TDF or ETV therapy. TDF and ETV are known to have few adverse effects that are more tolerable than interferon or other antiviral agents. However, ETV is classified as a category C drug that has potential risks for the fetus, and should be restricted during the first trimester of pregnancy; and since the serious adverse effect of TDF is nephrotoxicity, all TDF-treated patients should be investigated for their creatinine clearance during therapy.[25,26] Although there were no serious adverse effects in our study, the study duration of 12 months was not enough to observe long-term adverse effects.

Table 3.

The Cox regression analysis for predictive factors for complete virologic response

On the basis of the Cox regression analysis, high HBV DNA level at baseline was a significant negative predictor of virologic response. A recent study suggested that TDF was superior to ETV for achieving CVR in HBeAg-positive CHB patients with high HBV DNA levels, defined as a baseline HBV DNA >6 log10 IU/mL.[27] On the other hand, our results suggested that there was no significant difference in CVR rates between TDF and ETV in patients with high viral load [Figure 4]. Some earlier studies supported our results.[22,28] However, additional monitoring is needed to investigate long-term virologic response and virologic breakthrough during long-term use of TDF or ETV, in patients with high HBV DNA level.

This study included a cohort of ETV- or TDF-treated CHB patients and compared the efficacy and safety at 12 months of treatment. Limitations of our study were short follow-up times of the TDF group, relatively small size, as well as the retrospective design. Nevertheless, our study was significant because there are few comparative studies of virologic response and safety between TDF and ETV in treatment-naïve CHB patients.

CONCLUSION

Our results suggested that both TDF and ETV effectively maintain CVR, and are safe and well tolerated in treatment-naïve CHB patients. Furthermore, high HBV DNA level at baseline is a negative predictive factor for achieving CVR. Additional research on long-term data and virologic response in patients with high viral load are needed.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chae HB, Kim JH, Kim JK, Yim HJ. Current status of liver diseases in Korea: Hepatitis B. Korean J Hepatol. 2009;15:S13–24. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2009.15.S6.S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SR, Kudo M, Hino O, Han KH, Chung YH, Lee HS. Organizing Committee of Japan-Korea Liver Symposium. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan and Korea. A review. Oncology. 2008;75:13–6. doi: 10.1159/000173419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuen MF, Seto WK, Chow DH, Taui K, Wong DK, Ngai VW, et al. Long-term lamivudine therapy reduces the risk of long-term complications of chronic hepatitis B infection even in patients without advanced disease. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:1295–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaw YF, Sheen IS, Lee CM, Akarca US, Papatheodoridis GV, Suet-Hing Wong F, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), emtricitabine/TDF, and entecavir in patients with decompensated chronic hepatitis B liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:62–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.23952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korean association for the study of the Liver. KASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012;18:109–62. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2012.18.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abaalkhail F, Elsiesy H, AlOmair A, Alghamdi MY, Alalwan A, AlMasri N, et al. SASLT practice guidelines for the management of hepatitis B virus. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5–25. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.126311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenh AM, Pham PA. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8:1079–92. doi: 10.1586/eri.10.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honkoop P, De Man RA. Entecavir: A potent new antiviral drug for hepatitis B. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;12:683–8. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang TT, Lai CL, Kew Yoon S, Lee SS, Coelho HS, Carrilho FJ, et al. Entecavir treatment for up to 5 years in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;51:422–30. doi: 10.1002/hep.23327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Pokornowski KA, Eggers BJ, Fang J, et al. Longterm monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naive patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503–14. doi: 10.1002/hep.22841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, Gane E, de Man RA, Krastev Z, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2442–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snow-Lampart A, Chappell BJ, Curtis M, Zhu Y, Myrick F, Schawalder J, et al. No resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate detected after up to 144 weeks of therapy in patients mono infected with chronic hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2011;53:763–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.24078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gish RG, Clark MD, Kane SD, Shaw RE, Mangahas MF, Baqai S. Similar risk of renal events among patients treated with tenofovir or entecavir for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:941–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg T, Zoulim F, Moeller B, Trinh H, Marcellin P, Chan S, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of emtricitabine plus tenofovir DF vs. tenofovir DF monotherapy in adefovir-experienced chronic hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol. 2014;60:715–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langley DR, Walsh AW, Baldick CJ, Eggers BJ, Rose RE, Levine SM, et al. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus polymerase by entecavir. J Virol. 2007;81:3992–4001. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02395-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lampertico P. Partial virological response to nucleos(t)ide analogues in naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B: From guidelines to field practice. J Hepatol. 2009;50:644–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dogan UB, Kara B, Gumurdulu Y, Soylu A, Akin MS. Comparison of the efficacy of tenofovir and entecavir for the treatment of nucleos (t) ide-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2012;23:247–52. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2012.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guzelbulut F, Ovunc AO, Oetinkaya ZA, Senates E, Gökden Y, Saltürk AG, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of entecavir and tenofovir in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:477–80. doi: 10.5754/hge11426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ke W, Liu L, Zhang C, Ye X, Gao Y, Zhou S, et al. Comparison of efficacy and safety of Tenofovir and entecavir in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ceylan B, Yardimci C, Fincanci M, Eren G, Tozalgan U, Muderrisoglu C, et al. Comparison of tenofovir and entecavir in patients with chronic HBV infection. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2467–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae SH, Yoon SK, Jang JW, Kim CW, Nam SW, Choi JY, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype C prevails among chronic carriers of the virus in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:816–20. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.5.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim H, Jee YM, Song BC, Shin JW, Yang SH, Mun HS, et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotypes and serotypes in patients with chronic HBV infection in Korea. Intervirology. 2007;50:52–7. doi: 10.1159/000096313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JM, Ahn SH, Chang HY, Shin JE, Kim DY, Sim MK, et al. Reappraisal of HBV genotypes and clinical significance in Koreans using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Korean J Hepatol. 2004;10:260–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontana RJ. Side effects of long-term oral antiviral therapy for hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49:S185–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heathcore EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M. Three-year efficacy and safety through 4 years of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:132–43. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao L, Trinh HN, Li J, Nguyen MH. Tenofovir is superior to entecavir for achieving complete viral suppression in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients with high HBV DNA. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:629–37. doi: 10.1111/apt.12629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon SC, Krastev Z, Horban A, Petersen J, Sperl J, Dinh P, et al. Efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate at 240 weeks in patients with chronic hepatitis B with high baseline viral load. Hepatology. 2013;58:505–13. doi: 10.1002/hep.26277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]